- 1Department of Bio Medical Sciences, School of Bio Sciences and Technology, Vellore Institute of Technology, Vellore, Tamil Nadu, India

- 2Department of Integrative Biology, School of Bio Sciences and Technology, Vellore Institute of Technology, Vellore, Tamil Nadu, India

Introduction: The rise of multidrug-resistant Salmonella typhimurium is a severe public health threat that renders conventional antibiotics ineffective. This study employed a computational strategy to identify a novel drug target in S. typhimurium and screen food-based polyphenols as potential inhibitors.

Methods: A subtractive genomics approach was used to identify essential, pathogen-specific proteins. A lead target was prioritized based on its druggability, localization, and network interactions. The target’s 3D structure was then modeled for molecular docking, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, and binding free energy calculations with a polyphenol library.

Results: The screening identified UDP-N-acetylglucosamine transferase (MurG) as a promising and previously unexplored drug target. The polyphenol 6-prenylnaringenin showed a superior binding affinity for MurG compared to the antibiotic ciprofloxacin. Subsequent MD simulations and binding free energy calculations confirmed that the MurG-6-prenylnaringenin complex was significantly more stable.

Conclusion: This study validates MurG as a druggable target in S. typhimurium and identifies 6-prenylnaringenin as a potent inhibitor. With computational metrics superior to ciprofloxacin, 6-prenylnaringenin is a promising lead compound for developing new anti-Salmonella therapeutics. Future experimental validation is required to confirm these in silico findings.

Introduction

The global rise of antimicrobial and multidrug resistance in microbial pathogens is a significant public health concern. This escalating threat is largely attributed to the widespread misuse of antibiotics, including their application in poultry and cattle feeds. Furthermore, the improper administration of antibiotics in humans, such as taking incorrect dosages obtained through over-the-counter channels, is a major contributing factor to the proliferation of resistance (Alenazy, 2022; Lipsitch and Samore, 2002). S. typhimurium is a pathogen that primarily affects livestock, such as cattle and poultry. Although often host-specific, it can be transmitted to humans through a process known as zoonotic transmission. In humans, the infection typically manifests as an acute gastrointestinal illness with symptoms including fever, abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. In more severe cases, the infection can progress to invasive conditions like bacteremia, sepsis, osteomyelitis, reactive arthritis, and meningitis. The global public health burden of non-typhoidal Salmonella is significant, with estimates indicating approximately 93.8 million infections and 155,000 deaths occurring annually (Chen et al., 2013; Eng et al., 2015; Majowicz et al., 2010; Szilagyi et al., 1985; Zha et al., 2019). The bacterium has developed resistance to contemporary antibiotics through several sophisticated molecular mechanisms.

Enzymatic deactivation: Bacteria produce enzymes, such as β-lactamases, that chemically degrade or modify antibiotics, rendering them inactive before they can reach their cellular target (Edoo et al., 2017).

Target Site Modification: Mutations in the bacterial proteins that antibiotics target, like DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV, alter the drug-binding site. This change prevents the antibiotic from binding effectively, neutralizing its therapeutic effect (Mohammed et al., 2021).

Reduced membrane permeability: The pathogen can alter the protein channels (porins) in its outer membrane, narrowing the passage and restricting the entry of antibiotic molecules into the cell (Gopikrishnan & George Priya Doss, 2023).

Active efflux pumps: Bacteria utilize specialized membrane proteins that function as pumps. These pumps actively recognize and expel antibiotics from the cell before they can accumulate to a toxic concentration (Alenazy, 2022).

Horizontal gene transfer: Resistance genes, often located on mobile genetic elements like plasmids, are transferred between bacteria. This process allows for the rapid dissemination of resistance traits throughout a bacterial population (Wise, 1999).

The proliferation of these resistance mechanisms creates a significant therapeutic challenge, as the efficacy of conventional antibiotics continues to decline. Traditional drug discovery pipelines are poorly equipped to keep pace with this rapid evolutionary arms race, as they are both time-consuming and resource-intensive. Consequently, there is an urgent need for innovative and efficient strategies capable of identifying novel therapeutic targets that can circumvent existing resistance mechanisms (Davis et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2022; Jadimurthy et al., 2023; Vaou et al., 2022). This study addresses this gap by employing a two-stage computational approach. First, subtractive genomics is applied to rationally identify essential, pathogen-specific proteins. This ensures that potential targets are absent in the human host, a critical feature for minimizing off-target toxicity. Second, this target identification is paired with the computational screening of food-based polyphenols, a class of compounds noted for their favorable safety profiles. The novelty of this work lies in the seamless integration of these methods into a streamlined discovery framework, proceeding from a novel, low-toxicity target to a promising, naturally-derived lead compound against drug-resistant S. typhimurium (Ahammad et al., 2024; Attar, 2024; Sarker et al., 2023).

Polyphenols are a diverse class of plant-derived compounds (phytocompounds) recognized for their extensive therapeutic potential and versatile bioactivities, with numerous studies establishing their efficacy as potent antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory agents. These multifaceted properties contribute significantly to human health, positioning polyphenols as key molecules in preventive medicine. Consequently, ongoing research continues to highlight their promise as lead compounds for the development of novel therapeutic strategies against a wide range of disorders. In the search for novel therapeutic agents to combat antimicrobial resistance, natural compounds present a promising avenue. Among these, food-based polyphenols have emerged as particularly strong candidates due to their versatile bioactivities. This diverse class of phytocompounds has a well-documented record of potent antibacterial activity against a wide range of pathogens. Given their established safety and therapeutic potential, this study will focus on leveraging these natural molecules. Therefore, the primary aim of this research is to computationally screen and evaluate specific food-based polyphenols for their ability to inhibit the newly identified drug target in S. typhimurium, thereby laying the groundwork for a novel therapeutic strategy (Buchmann et al., 2023; Elmaidomy et al., 2022; Joshi et al., 2021; Othman et al., 2019; Rabaan et al., 2023; Rothwell et al., 2013; Tan et al., 2022; Zhong et al., 2023).

In response to the urgent need for novel therapeutics against S. typhimurium, a comprehensive subtractive genomics pipeline was employed to identify essential, pathogen-specific proteins as potential drug targets. Integration of this approach with the screening of bioactive, food-derived polyphenols provides a rational strategy for the discovery of novel inhibitory compounds with therapeutic potential. Systematic identification and evaluation of such targets and inhibitors were conducted through integrated computational analyses, establishing a foundation for subsequent experimental validation.

Materials and methods

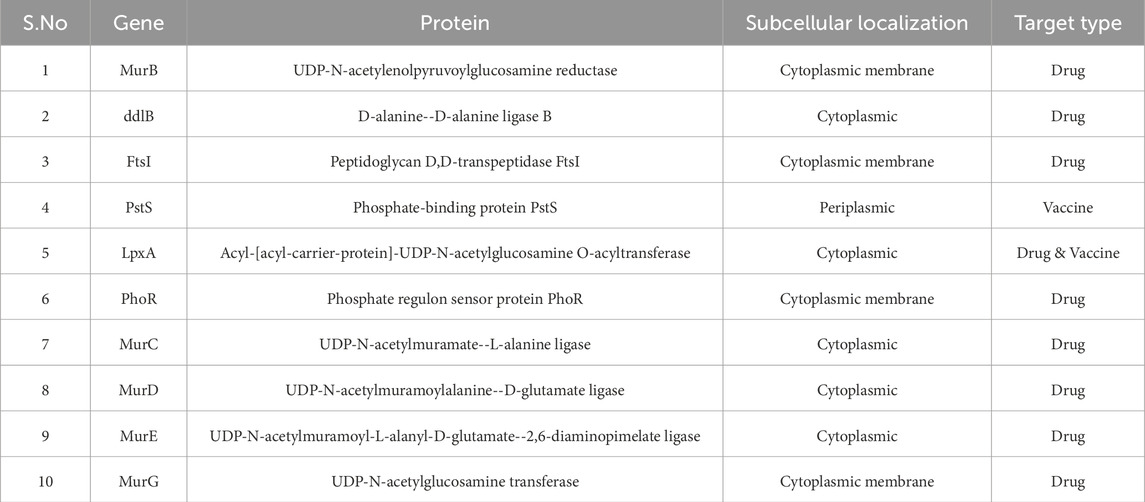

The computational workflow of this investigation was organized into three sequential stages, as illustrated (Figure 1). The initial stage involved Data Collection, where the proteomes of the host and pathogen were retrieved. This was followed by the Subtractive Genomic Approach, a systematic filtering pipeline used to identify essential, non-homologous, and druggable protein targets unique to the pathogen. The final Structure-Based Approach involved homology modeling of the prioritized target, followed by molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, and binding free energy calculations to evaluate its interaction with potential inhibitors.

Figure 1. Workflow illustrating the computational pipeline for identification and evaluation of novel drug targets in Salmonella typhimurium.

Data retrieval

Metabolic pathway analysis

To identify pathogen specific metabolic pathways, the complete pathway maps for the host (Homo sapiens, hsa01100) and the pathogen (S. typhimurium, stm01100) were obtained from the Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html) (accessed on May 2025). A comparative analysis was performed to isolate the metabolic pathways that are unique to the pathogen. The proteins associated with these pathogen-specific pathways were then identified, and their corresponding sequences were retrieved from the UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org/) (accessed on June 2025). The reference proteome used for S. typhimurium in this study was accessed under the accession number UP000001014 (Damte et al., 2013).

Non-homologous protein identification

To identify proteins unique to the pathogen, the retrieved protein set was subjected to a BLASTp (Protein Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) analysis against the Homo sapiens reference proteome in the NCBI database (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PAGE=Proteins&PROGRAM=blastp&BLAST_PROGRAMS=blastp&PAGE_TYPE=BlastSearch&BLAST_SPEC=blast2seq) (accessed on June 2025). A stringent E-value threshold of 10−4 was applied to determine homology. Proteins showing significant similarity to human proteins were filtered out and discarded from the dataset. The remaining non-homologous proteins were then selected for the subsequent essentiality analysis (Damte et al., 2013).

Essentiality analysis

Essential genes are those that are indispensable for an organism’s survival, as they play a critical role in fundamental cellular processes. To identify these crucial genes in S. typhimurium, the Database of Essential Genes (DEG) (http://origin.tubic.org/deg/public/index.php) (accessed on June 2025) was systematically queried. The database was navigated to the bacteria-specific section and searched using the keyword “Salmonella typhimurium LT2”. The resulting list of genes, confirmed as essential for this pathogen, was then selected for the subsequent stages of analysis (Luo et al., 2021; Subramani and Venugopal, 2025).

Druggability assay

To evaluate the druggable potential of the candidate proteins, their sequences were compared against known therapeutic targets housed in the DrugBank database (https://go.drugbank.com/) (accessed on June 2025). This was performed using a BLASTp analysis with an E-value threshold of 10−3. Proteins that showed significant sequence similarity to established drug targets were considered “druggable” and were selected for further investigation (Subramani and Venugopal, 2025).

Analysis of cellular localization

To determine the subcellular localization of the candidate proteins, their sequences were submitted to the PSORTb server 3.0.3 (https://psort.org/psortb/) (accessed on June 2025). This analysis predicts the specific location of each protein within the bacterial cell, such as the cytoplasm, cytoplasmic membrane, cell wall, or extracellular space. This information is critical for target prioritization, as a protein’s location helps determine its potential as either a therapeutic drug target (often internal) or a vaccine candidate (typically surface-exposed) (Sarker et al., 2023).

Protein network analysis

To evaluate the functional relationships between the candidate proteins, a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis was performed using the STRING database version 12.0 (https://string-db.org/) (accessed on June 2025). The purpose of this analysis was to identify which proteins serve as central hubs with a high degree of connectivity to other proteins. From this analysis, the final novel target was selected based on its strong functional associations within the network, indicating its critical role in cellular processes (Subramani and Venugopal, 2025).

Homology modelling

The three-dimensional (3D) structure of the target protein was generated via homology modelling using the SWISS-MODEL server (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/) (accessed on June 2025, with its primary amino acid sequence as input. The crystal structure 1F0K from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) was selected as the template for model construction, as it shared a high sequence identity of 92%. Following its generation, the stereochemical quality and accuracy of the model were rigorously validated by analyzing its ERRAT score and Ramachandran plot using the SAVES v6.1 server (https://saves.mbi.ucla.edu/) (accessed on June 2025) and by calculating its overall quality Z-score with the ProSA-web server (https://prosa.services.came.sbg.ac.at/prosa.php) (accessed on June 2025) (Subramani and Venugopal, 2025).

Ligand and protein preparation

Food-derived polyphenols were retrieved from the Phenol-Explorer 3.6 database, which contains information on 500 polyphenols from 400 different foods (Rothwell et al., 2013). These compounds were first evaluated for drug-likeness properties using three established criteria: Lipinski’s rule of five (molecular weight <500 Da, lipophilicity <5, ≤5 hydrogen bond donors, ≤10 hydrogen bond acceptors) (Lipinski, 2004), Veber rule (≤10 rotatable bonds, polar surface area <140 Å2), and Ghose filter (molecular weight 160–480 Da, lipophilicity −0.4 to 5.6, molar refractivity 40–130, total atoms 20–70). Compounds that satisfied these criteria were selected for further analysis. The SMILES format of each selected ligand was converted into PDB format using Open Babel GUI 2.3.1 (O’Boyle et al., 2011). For docking studies, ligands were prepared in AutoDock Tools 1.5.7 by defining the root, adding hydrogen atoms and aromatic carbons, determining torsional degrees of freedom, and assigning Gasteiger charges. The processed ligands were saved in PDBQT format. Similarly, the modeled protein was prepared in AutoDock Tools 1.5.7 by removing water molecules, adding polar hydrogens, and assigning Kollman charges before saving in PDBQT format (Valathoor and Venugopal, 2024a).

Molecular docking analysis

The prepared ligands were docked with the modelled protein using AutoDock Vina. A grid box was set with dimensions of 62 × 48 × 70 Å at 1 Å spacing, and the grid center was defined at X = −0.956 Å, Y = 4.609 Å, and Z = 8.724 Å. Binding energies were calculated using the gradient-based optimization algorithm implemented in the program. The docking algorithm explores multiple binding conformations and clusters them by similarity. The reported binding energy corresponds to the lowest-energy pose in the most populated cluster, representing the most statistically probable binding mode. Ciprofloxacin, a commercially available antibiotic, was included as a reference compound for comparison. Based on the docking results, the highest-ranking polyphenol-protein complex, along with the ciprofloxacin-protein complex, was selected for molecular dynamics simulation studies (Subramani and Venugopal, 2025; Valathoor and Venugopal, 2024b).

Molecular dynamic simulation analysis

Molecular dynamics simulations were performed for 100 ns on the native protein and on complexes formed with 6-prenylnaringenin and ciprofloxacin using GROMACS 2024 (Van Der Spoel et al., 2005). The CHARMM27 force field was applied to prepare the protein topology in GROMACS, while ligand topologies were generated using the SwissParam server (Vanommeslaeghe et al., 2010; Zoete et al., 2011). Each system was solvated in a cubic box with NaCl, and energy minimization was carried out using the steepest descent algorithm with the Verlet cutoff scheme to remove steric clashes. The systems were equilibrated at 300 K in two phases: first under the NVT ensemble (constant number of particles, volume, and temperature), followed by the NPT ensemble (constant number of particles, pressure, and temperature). A production MD run of 100 ns was then conducted, and trajectory analyses, including RMSD, RMSF, radius of gyration (Rg), hydrogen bonding (Hb), principal component analysis (PCA), and solvent-accessible surface area (SASA), were performed using GROMACS tools. Graphs were plotted with XMGrace (Valathoor and Venugopal, 2024c).

Molecular mechanics generalized born surface area analysis

The molecular mechanics generalized Born surface area (MMGBSA) method was applied to estimate the binding free energy (ΔG) and evaluate the strength of the protein-ligand complexes. For this analysis, the final 20 ns of the MD simulation trajectories were used, and calculations were performed with the gmx_MMPBSA analysis tool. The final energy values are reported as the mean ±standard deviation, calculated from snapshots taken across the trajectory. This provides a quantitative measure of the interaction’s stability and the statistical confidence in the calculated binding energy from snapshots taken across the trajectory. This provides a quantitative measure of the interaction’s stability and the statistical confidence in the calculated binding energy (Bello, 2024; Valdés-Tresanco et al., 2021). This approach provided quantitative insights into the relative binding strengths of 6-prenylnaringenin and ciprofloxacin with the MurG protein.

In the equation, ΔGbind stands for the binding free energy, ΔGcomplex for the free energy complex, ΔGprotein for the free energy of protein, and ΔGligand for the free energy of ligand, ΔEmm stands for molecular mechanics, ΔGsol stands for electrostatic solvation energy calculated using the GB model, TΔS stands for the conformational entropy after ligand binding, ΔH for enthalpy, ΔEvdw for Van der Waals energy, and ΔEele for electrostatic interaction.

Results

Metabolic pathway analysis and protein retrieval

The KEGG database catalogs 367 metabolic pathways for Homo sapiens (host) and 137 pathways for S. typhimurium (pathogen). Comparative mapping revealed 45 pathways unique to S. typhimurium (Table 1), comprising 620 proteins in total. The corresponding sequences were retrieved from the UniProt database for downstream analysis.

Non-homologous proteins identification

To exclude host homologues, all retrieved proteins were screened against the human proteome using BLASTp. A total of 123 proteins showed significant similarity to human proteins and were excluded. The remaining 497 non-homologous proteins were retained for further analyses.

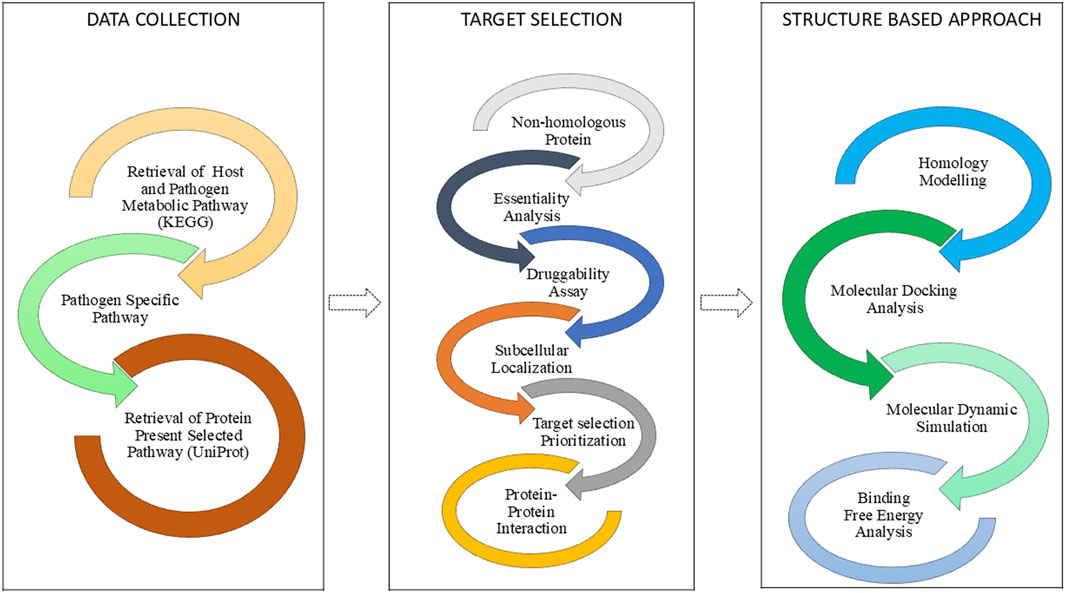

Essentiality analysis

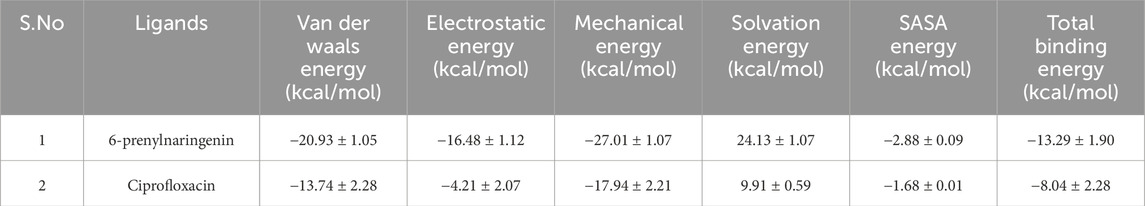

Genes essential for bacterial viability were identified by comparison with the Database of Essential Genes (DEG). Among the 497 non-homologous proteins, only 10 were found to be essential for S. typhimurium survival (Table 2), and these were prioritized for subsequent evaluation (Luo et al., 2021).

Druggability analysis

The 10 essential proteins were assessed for druggability against FDA-approved drugs from the DrugBank database. All shortlisted proteins demonstrated potential drug-binding capacity, confirming their suitability as pharmacological targets (Subramani and Venugopal, 2025).

Sub cellular localization analysis

Subcellular localization is a key determinant in distinguishing potential drug and vaccine targets. Cytoplasmic proteins are typically preferred for drug development, while membrane-associated and periplasmic proteins are prioritized for vaccine design (Alhamhoom et al., 2022). Of the 10 essential proteins, five localized to the cytoplasm, four to the cytoplasmic membrane, and one to the periplasm (Figure 2). Accordingly, while all are druggable, the periplasmic protein is particularly attractive as a vaccine candidate (Table 2).

Figure 2. Distribution of subcellular localization of shortlisted essential proteins in Salmonella typhimurium.

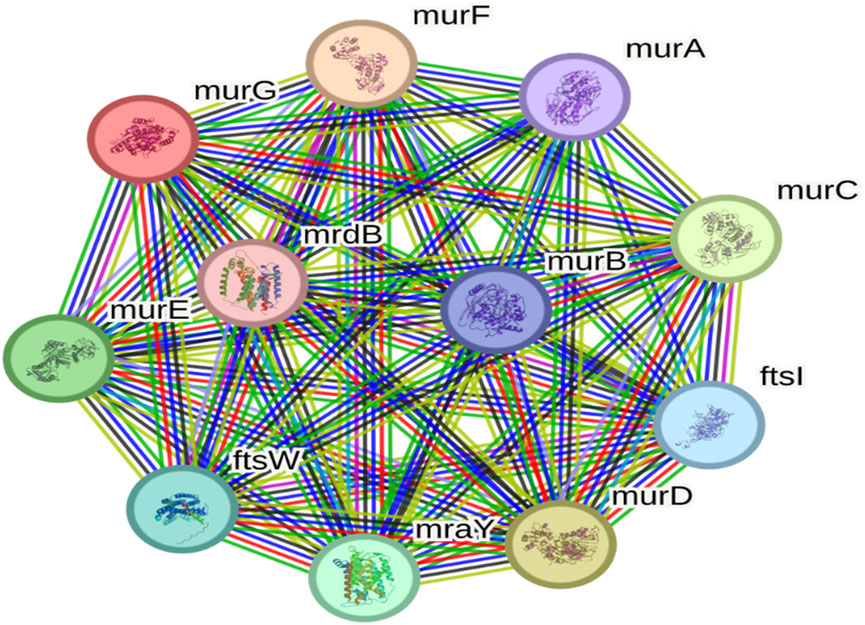

Protein network analysis

To evaluate functional connectivity, protein-protein interaction (PPI) analysis was performed. UDP-N-acetylglucosamine transferase (MurG) emerged as a hub protein, exhibiting 11 nodes and 55 edges with an average node degree of 10 (Figure 3). Its strong interaction profile underscored MurG as a central regulator and promising therapeutic target (Subramani and Venugopal, 2025).

Figure 3. Protein-protein interaction network highlighting MurG as a central hub in Salmonella typhimurium.

UDP-N-acetylglucosamine transferase (MurG)

MurG plays a critical role in peptidoglycan biosynthesis by catalyzing the transfer of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) from UDP-GlcNAc to lipid I, generating lipid II, a key intermediate in bacterial cell wall synthesis. The UniProt ID of MurG is Q8ZRU3. It consists of 355 amino acids, with a theoretical pI of 9.71, molecular weight of 37.86 kDa, 27 negatively charged and 34 positively charged residues, an aliphatic index of 94.87, and a GRAVY score of 0.105. The instability index classified MurG as a stable protein. Given its indispensable role in cell wall construction, MurG represents a novel and high-value target for antimicrobial development (Garde et al., 2021).

Homology modelling

The three-dimensional structure of MurG was generated using Swiss-Model. Structural validation indicated high reliability, with 95.4% of residues in the most favorable Ramachandran regions, 4.6% in additionally allowed regions, an ERRAT score of 99%, and a ProSA Z-score of −10.61. These parameters confirmed the accuracy and robustness of the model for downstream analyses (Figure 4) (Sarker et al., 2023).

Figure 4. Structure of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine transferase (MurG). (a) Modelled protein structure (b) Ramachandran plot (c) ProsA-overall model quality (d) ERRAT -overall quality factor.

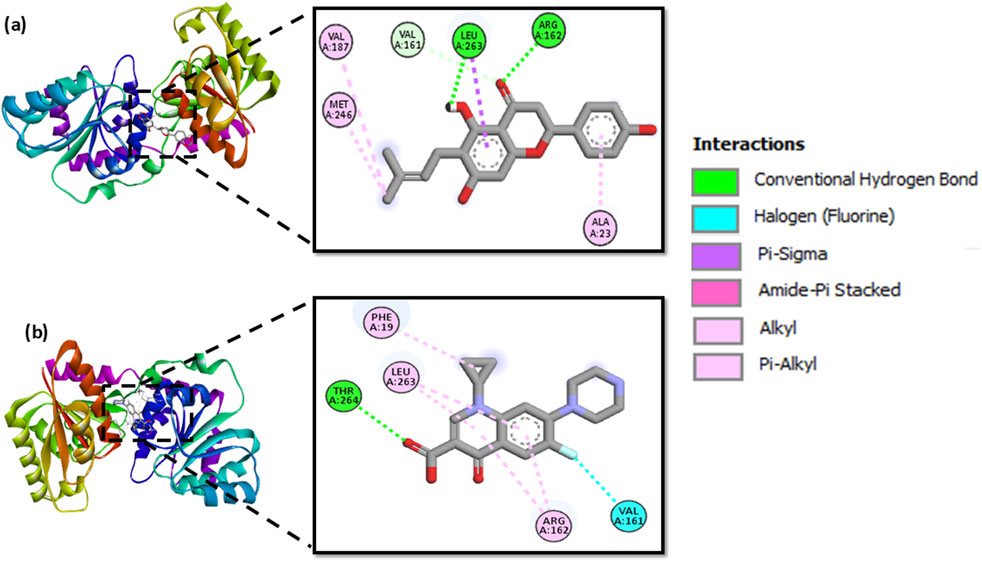

Molecular docking analysis

Molecular docking of MurG with 244 polyphenols produced binding affinities ranging from −8.9 to −4.9 kcal/mol. The top ten protein-ligand complexes were re-docked for validation, and 6-prenylnaringenin was identified as the most favourable candidate, with a binding affinity of −7.9 kcal/mol. This complex formed two hydrogen bonds with Arg162 and Leu263, along with additional hydrophobic contacts involving Ala23, Val161, Val187, Leu263, and Met246. By comparison, ciprofloxacin exhibited a binding affinity of −7.3 kcal/mol, forming a single hydrogen bond with Thr264 and hydrophobic interactions with Phe19, Val161, Arg162, Leu263, and Thr264. Both ligand-protein complexes (MurG-6-prenylnaringenin and MurG-ciprofloxacin) were selected for molecular dynamics simulations to further examine conformational stability (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Molecular docking poses of MurG with (a) 6-prenylnaringenin and (b) ciprofloxacin, showing key interactions.

Molecular dynamic simulation analysis

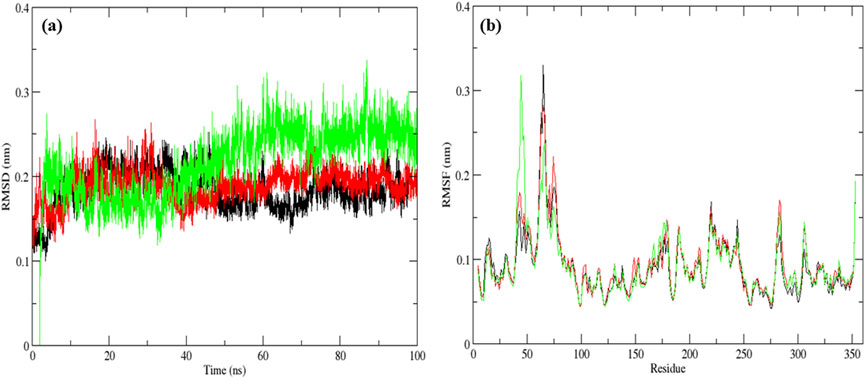

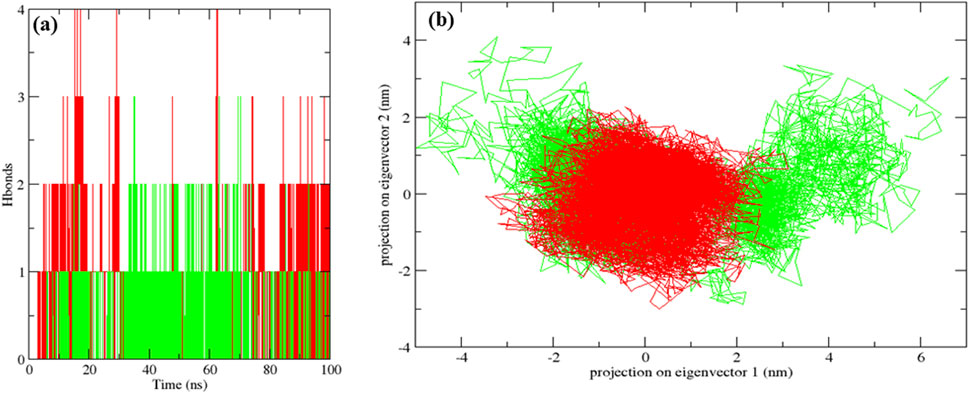

The native MurG protein, the MurG-6-prenylnaringenin complex, and the MurG-ciprofloxacin complex was subjected to 100 ns molecular dynamics simulations. Structural stability was first assessed using root mean square deviation (RMSD), where lower values indicate higher stability (Azmal et al., 2024). All systems remained stable, with the 6-prenylnaringenin complex and the native protein displaying greater stability than the ciprofloxacin complex (Figure 6a). Residue-level flexibility was examined through root mean square fluctuation (RMSF). Fluctuations below 7 Å are generally considered stable (Fatriansyah et al., 2022), and in this case, most residues exhibited low variability, apart from minor fluctuations between residues 70–77 in all systems and additional fluctuation between residues 45–52 in the ciprofloxacin complex (Figure 6b). Compactness of the protein structures was evaluated using the radius of gyration (Rg), where lower values indicate tighter folding (Valathoor and Venugopal, 2024b). The average Rg values were 2.19 nm for the native protein, 2.16 nm for the 6-prenylnaringenin complex, and 2.18 nm for the ciprofloxacin complex, suggesting that the polyphenol complex was slightly more compact (Figure 7a). Solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) analysis showed mean values of 163 nm2 for the native protein, 162 nm2 for the 6-prenylnaringenin complex, and 164 nm2 for the ciprofloxacin complex. The lower SASA of the polyphenol-bound system indicates reduced solvent exposure compared with the other systems (Valathoor and Venugopal, 2024b) (Figure 7b). Hydrogen bond analysis, an indicator of interaction strength (Sapir and Harries, 2017), revealed that the 6-prenylnaringenin complex formed up to four hydrogen bonds, compared with a maximum of three for ciprofloxacin (Figure 8a). Principal component analysis (PCA) was further used to examine conformational dynamics. A more condensed cluster in the PCA plot reflects a reduced conformational space, whereas a dispersed cluster indicates broader sampling (Valathoor and Venugopal, 2024c). The PCA results confirmed that the 6-prenylnaringenin complex was more compact than both the ciprofloxacin and native systems (Figure 8b).

Figure 6. Molecular dynamic simulation results for a duration of 100 ns UDP-N-acetylglucosamine transferase (MurG) native protein (black), 6-Prenylnaringenin (red), ciprofloxacin (green) complexes (a) Root mean square deviation and (b) Root mean square fluctuation.

Figure 7. Molecular dynamic simulation results for a duration of 100 ns UDP-N-acetylglucosamine transferase (MurG) native protein (black), 6-Prenylnaringenin (red), ciprofloxacin (green) complexes (a) Radius of gyration and (b) Solvent accessible surface area.

Figure 8. Molecular dynamic simulation results for a duration of 100 ns UDP-N-acetylglucosamine transferase (MurG) native protein (black), 6-Prenylnaringenin (red), ciprofloxacin (green) complexes (a) Hydrogen bonds and (b) Principle component analysis.

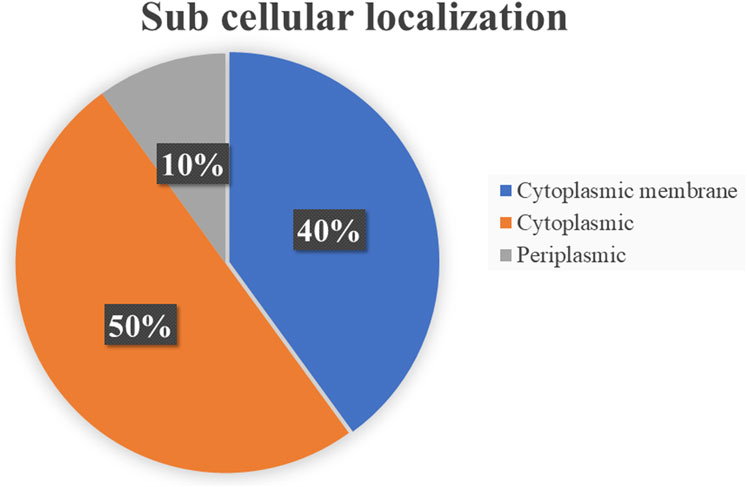

Molecular mechanics generalized born surface area analysis

Molecular mechanics generalized Born surface area (MM-GBSA) calculations were carried out to estimate the binding free energies of the MurG-ligand complexes. The MurG-6-prenylnaringenin complex exhibited stronger interactions, with van der Waals, electrostatic, and mechanical energies of −20.93, −16.48, and −27.01 kcal/mol, respectively. In contrast, the MurG-ciprofloxacin complex showed comparatively weaker interactions, with corresponding values of −13.74, −4.21, and −17.94 kcal/mol. Solvation energies were 24.13 kcal/mol for the polyphenol complex and 9.91 kcal/mol for ciprofloxacin, while SASA contributions were −2.88 and −1.68 kcal/mol, respectively. The total binding free energy was calculated as −13.29 kcal/mol for the 6-prenylnaringenin complex and −8.04 kcal/mol for the ciprofloxacin complex, confirming the superior binding strength and stability of the polyphenol ligand (Table 3; Figure 9).

Figure 9. Binding free energy of 6-Prenylnaringenin complex (red) and ciprofloxacin complex (green).

Discussion

The rapid rise of antimicrobial and multidrug resistant strains underscores the urgent need for novel antibiotics or alternative therapeutic targets. In this study, UDP N-acetylglucosamine transferase (MurG) was identified as a promising druggable target in S. typhimurium through a subtractive genomic approach. Comparative pathway analysis between H. sapiens (367 pathways) and S. typhimurium (137 pathways) revealed 45 pathogen-specific pathways comprising 620 proteins. Of these, 123 homologous proteins were excluded, and the remaining 497 non-homologous proteins were screened for essentiality. Ten essential proteins were retained, all of which displayed druggable potential: five were cytoplasmic, four were associated with the cytoplasmic membrane, and one was periplasmic. Network analysis highlighted MurG as a central hub protein, making it the final candidate. MurG plays a key role in peptidoglycan biosynthesis, and its inhibition could disrupt cell wall formation in S. typhimurium.

Among the key enzymes involved in peptidoglycan biosynthesis, several, including MurA, MurB, MurC, MurD, and MurE, have been extensively studied and targeted in antimicrobial development due to their essential role in bacterial cell wall formation (Subramani and Venugopal, 2025). In contrast, UDP-N-acetylglucosamine transferase (MurG), which catalyzes the final glycosyltransferase step to produce lipid II, remains comparatively underexplored as a therapeutic target in Salmonella species (Garde et al., 2021). Its unique enzymatic function and central position within the peptidoglycan biosynthesis pathway enhance its potential as a novel druggable target, further supported by its identification as a hub protein in the present protein-protein interaction network (Subramani and Venugopal, 2025).

The three-dimensional structure of MurG was generated using SWISS-MODEL and validated by Ramachandran plot, ERRAT score, and Z-score analyses, confirming the model’s reliability. Docking experiments with food-derived polyphenols revealed that 6-prenylnaringenin exhibited stronger binding affinity and more favourable hydrogen bond interactions with MurG compared to ciprofloxacin. Molecular dynamics simulations further supported this finding: RMSD and RMSF values indicated stable conformations for the native protein and both complexes, with the 6-prenylnaringenin complex showing greater stability than the ciprofloxacin complex. Radius of gyration (Rg) analysis demonstrated tighter folding of the polyphenol complex, while hydrogen bond analysis revealed a greater number of stable hydrogen bonds. Solvent accessibility calculations showed reduced exposure of the polyphenol complex to surface solvent compared to the native protein and ciprofloxacin complex. Principal component analysis (PCA) indicated that the 6-prenylnaringenin complex occupied a smaller conformational space, reflecting enhanced structural compactness.

Binding free energy (ΔG) calculations reinforced these results, as the MurG-6-prenylnaringenin complex demonstrated stronger overall binding than the MurG-ciprofloxacin complex. The superior stability observed for the MurG-6-prenylnaringenin complex can be attributed to its distinct structural features. Mechanistically, the flavanone core and the flexible prenyl group of 6-prenylnaringenin appear to facilitate a more optimal fit within the binding pocket of the enzyme. The molecular dynamics simulations suggest that this binding induces a more compact and conformationally stable state in the MurG protein. This stability is likely achieved through a robust network of interactions, including strong hydrogen bonds with key residues like Arg162 and extensive hydrophobic contacts involving the prenyl tail. By anchoring the ligand so effectively, these interactions may lock the enzyme in an inactive state, preventing the catalytic conformational changes required for Lipid II synthesis. This provides a clear mechanistic basis for its potential inhibitory function, which contrasts with the less stable and more transient interaction observed with ciprofloxacin.

Taken together, these findings suggest that 6-prenylnaringenin may act as a potent inhibitor of MurG, offering a potential therapeutic strategy against S. typhimurium. Similar inhibitory activity has previously been reported for the flavonoid fisetin against the LpoB protein of S. typhimurium, supporting the broader antibacterial potential of dietary polyphenols (Valathoor and Venugopal, 2024b). The identification of 6-prenylnaringenin as a direct inhibitor of MurG contributes to the growing body of research on flavonoids as antibacterial agents. For instance, recent work by Zhong et al. (2023) demonstrated a different, synergistic mechanism whereby flavonoids disrupt bacterial iron homeostasis to potentiate the effects of existing antibiotics. This contrasts with the present study, which identifies a direct inhibitory mechanism against an essential enzyme, highlighting the diverse therapeutic strategies offered by this class of natural compounds.

Conclusion

This work highlights UDP-N-acetylglucosamine transferase (MurG) as a novel and promising therapeutic target in S. typhimurium, identified through a systematic subtractive genomic strategy. Structural modelling and computational analyses, including molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations, demonstrated that the dietary polyphenol 6-prenylnaringenin binds MurG with greater stability and affinity than the widely used antibiotic ciprofloxacin. These findings suggest that 6-prenylnaringenin may serve as a potential lead compound for the development of new anti-Salmonella therapeutics. Nevertheless, as this study is restricted to in silico investigations, experimental validation through in vitro assays and in vivo infection models will be essential to confirm its inhibitory potential and therapeutic relevance. Building on these results, future studies could explore structural optimization of 6-prenylnaringenin and its derivatives to enhance binding specificity and efficacy, assess cytotoxicity and pharmacokinetic properties, and investigate potential synergistic effects with existing antibiotics to address multidrug-resistant Salmonella infections. Furthermore, future iterations of this discovery pipeline could be significantly enhanced by incorporating advanced machine learning models. For instance, developing a Heterogeneous Information Network (HIN) could accelerate the discovery process by predicting novel drug-target interactions or suggesting candidates for drug repositioning, similar to frameworks recently used in bioinformatics (Zhao et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2024). Additionally, sequence-based deep learning models could be trained to rapidly screen new compounds for inhibitory potential against MurG, offering predictive power from sequence data alone (Li et al., 2025). Integrating these specific AI-driven strategies represents a promising direction for refining and accelerating the search for novel antimicrobial therapeutics.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

MV: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. SV: Supervision, Writing – review and editing, Conceptualization. AR: Supervision, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the management of Vellore Institute of Technology for providing the necessary facilities to carry out this research work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The authors declare that an AI-based language editing tool was used solely for grammar and style improvements, and that all scientific content, analysis, and interpretations are entirely the authors’ own.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahammad, I., Jamal, T. B., Lamisa, A. B., Bhattacharjee, A., Zinan, N., Hasan Chowdhury, M. Z., et al. (2024). Subtractive genomics study of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. Oryzae reveals repurposable drug candidate for the treatment of bacterial leaf blight in rice. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 22 (1), 100353. doi:10.1016/j.jgeb.2024.100353

Alenazy, R. (2022). Antibiotic resistance in salmonella: targeting multidrug resistance by understanding efflux pumps, regulators and the inhibitors. J. King Saud Univ. - Sci. 34 (Issue 7), 102275. doi:10.1016/j.jksus.2022.102275

Alhamhoom, Y., Hani, U., Bennani, F. E., Rahman, N., Rashid, M. A., Abbas, M. N., et al. (2022). Identification of new drug target in Staphylococcus lugdunensis by subtractive genomics analysis and their inhibitors through molecular docking and molecular dynamic simulation studies. Bioengineering 9 (9), 451. doi:10.3390/bioengineering9090451

Attar, R. (2024). Integrated computational approaches assisted development of a novel multi-epitope vaccine against MDR Streptococcus pseudopneumoniae. Braz. J. Biol. 84, e269313. doi:10.1590/1519-6984.269313

Azmal, M., Hossen, M. S., Shohan, M. N. H., Taqui, R., Malik, A., and Ghosh, A. (2024). A computational approach to identify phytochemicals as potential inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase: molecular docking, ADME profiling and molecular dynamics simulations. PLoS ONE 19 (6 June), e0304490. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0304490

Bello, M. (2024). Evaluation of structural and thermodynamic insight of ERβ with DPN and derivatives through MMGBSA/MMPBSA methods. Steroids 201, 109334. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2023.109334

Buchmann, D., Schwabe, M., Weiss, R., Kuss, A. W., Schaufler, K., Schlüter, R., et al. (2023). Natural phenolic compounds as biofilm inhibitors of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli – the role of similar biological processes despite structural diversity. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1232039. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2023.1232039

Chen, H. M., Wang, Y., Su, L. H., and Chiu, C. H. (2013). Nontyphoid salmonella infection: microbiology, clinical features, and antimicrobial therapy. Pediatr. Neonatol. 54 (Issue 3), 147–152. doi:10.1016/j.pedneo.2013.01.010

Damte, D., Suh, J. W., Lee, S. J., Yohannes, S. B., Hossain, M. A., and Park, S. C. (2013). Putative drug and vaccine target protein identification using comparative genomic analysis of KEGG annotated metabolic pathways of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae. Genomics 102 (1), 47–56. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2013.04.011

Davis, M. W., Wason, S., and DiGiacinto, J. L. (2013). Colchicine-antimicrobial drug interactions: what pharmacists need to know in treating gout. Consult. Pharm. 28 (3), 176–183. doi:10.4140/TCP.n.2013.176

Edoo, Z., Arthur, M., and Hugonnet, J. E. (2017). Reversible inactivation of a peptidoglycan transpeptidase by a β-lactam antibiotic mediated by β-lactam-ring recyclization in the enzyme active site. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 9136. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-09341-8

Elmaidomy, A. H., Shady, N. H., Abdeljawad, K. M., Elzamkan, M. B., Helmy, H. H., Tarshan, E. A., et al. (2022). Antimicrobial potentials of natural products against multidrug resistance pathogens: a comprehensive review. RSC Adv. 12 (Issue 45), 29078–29102. doi:10.1039/d2ra04884a

Eng, S. K., Pusparajah, P., Ab Mutalib, N. S., Ser, H. L., Chan, K. G., and Lee, L. H. (2015). Salmonella: a review on pathogenesis, epidemiology and antibiotic resistance. Front. Life Sci. 8 (3), 284–293. doi:10.1080/21553769.2015.1051243

Fatriansyah, J. F., Rizqillah, R. K., Yandi, M. Y., and Sahlan, M. (2022). Molecular docking and dynamics studies on propolis sulabiroin-A as a potential inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2. J. King Saud Univ. 34 (1), 101707. doi:10.1016/j.jksus.2021.101707

Garde, S., Chodisetti, P. K., and Reddy, M. (2021). Peptidoglycan: structure, synthesis, and regulation. EcoSal Plus 9 (2). doi:10.1128/ecosalplus.esp-0010-2020

Gopikrishnan, M., and George Priya Doss, C. (2023). Molecular docking and dynamic approach to screen the drug candidate against the Imipenem-resistant CarO porin in Acinetobacter baumannii. Microb. Pathog. 177, 106049. doi:10.1016/j.micpath.2023.106049

Huang, W., Wang, Y., Tian, W., Cui, X., Tu, P., Li, J., et al. (2022). Biosynthesis investigations of terpenoid, alkaloid, and flavonoid antimicrobial agents derived from medicinal plants. Antibiotics 11 (Issue 10), 1380. doi:10.3390/antibiotics11101380

Jadimurthy, R., Jagadish, S., Nayak, S. C., Kumar, S., Mohan, C. D., and Rangappa, K. S. (2023). Phytochemicals as invaluable sources of potent antimicrobial agents to combat antibiotic resistance. Life 13 (Issue 4), 948. doi:10.3390/life13040948

Joshi, T., Joshi, T., Sharma, P., Chandra, S., and Pande, V. (2021). Molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation approach to screen natural compounds for inhibition of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. Oryzae by targeting peptide deformylase. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 39 (3), 823–840. doi:10.1080/07391102.2020.1719200

Li, D., Li, Z., Zhao, B., Su, X., Li, G., and Hu, L. (2025). DeepHIV: a sequence-based deep learning model for predicting HIV-1 protease cleavage sites. IEEE Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinforma., 1–8. doi:10.1109/TCBBIO.2025.3610881

Lipinski, C. A. (2004). Lead- and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 1 (4), 337–341. doi:10.1016/j.ddtec.2004.11.007

Lipsitch, M., and Samore, M. H. (2002). Antimicrobial use and antimicrobial resistance: a population perspective. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8 (Issue 4), 347–354. doi:10.3201/eid0804.010312

Luo, H., Lin, Y., Liu, T., Lai, F. L., Zhang, C. T., Gao, F., et al. (2021). DEG 15, an update of the database of essential genes that includes built-in analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 49 (D1), D677–D686. doi:10.1093/nar/gkaa917

Majowicz, S. E., Musto, J., Scallan, E., Angulo, F. J., Kirk, M., O’Brien, S. J., et al. (2010). The global burden of nontyphoidal salmonella gastroenteritis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 50 (Issue 6), 882–889. doi:10.1086/650733

Mohammed, M. A., Salim, M. T. A., Anwer, B. E., Aboshanab, K. M., and Aboulwafa, M. M. (2021). Impact of target site mutations and plasmid associated resistance genes acquisition on resistance of Acinetobacter baumannii to fluoroquinolones. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 20136. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-99230-y

Othman, L., Sleiman, A., and Abdel-Massih, R. M. (2019). Antimicrobial activity of polyphenols and alkaloids in middle eastern plants. Front. Microbiol. 10 (Issue MAY), 911. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2019.00911

O’Boyle, N. M., Banck, M., James, C. A., Morley, C., Vandermeersch, T., and Hutchison, G. R. (2011). Open babel: an open chemical toolbox. J. Cheminformatics 3 (10), 33. doi:10.1186/1758-2946-3-33

Rabaan, A. A., Garout, M., Aljeldah, M., Al Shammari, B. R., Alawfi, A., Alshengeti, A., et al. (2023). Anti-tubercular activity evaluation of natural compounds by targeting Mycobacterium tuberculosis resuscitation promoting factor B inhibition: an in silico study. Mol. Divers. 28, 1057–1072. doi:10.1007/s11030-023-10632-8

Rothwell, J. A., Perez-Jimenez, J., Neveu, V., Medina-Remón, A., M’Hiri, N., García-Lobato, P., et al. (2013). Phenol-explorer 3.0: a major update of the phenol-explorer database to incorporate data on the effects of food processing on polyphenol content. Database 2013, bat070. doi:10.1093/database/bat070

Sapir, L., and Harries, D. (2017). Revisiting hydrogen bond thermodynamics in molecular simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 13 (6), 2851–2857. doi:10.1021/acs.jctc.7b00238

Sarker, P., Mitro, A., Hoque, H., Hasan, M. N., and Nurnabi Azad Jewel, G. M. (2023). Identification of potential novel therapeutic drug target against Elizabethkingia anophelis by integrative pan and subtractive genomic analysis: an in silico approach. Comput. Biol. Med. 165, 107436. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.107436

Subramani, N. K., and Venugopal, S. (2025). Identification of novel drug targets and small molecule discovery for MRSA infections. Front. Bioinforma. 5, 1562596. doi:10.3389/fbinf.2025.1562596

Szilagyi, A., Gerson, M., Mendelson, J., and Yusuf, N. A. (1985). Salmonella infections complicating inflammatory bowel disease. J. Clin. Gastroenterology 7 (3), 251–255. doi:10.1097/00004836-198506000-00013

Tan, Z., Deng, J., Ye, Q., and Zhang, Z. (2022). The antibacterial activity of natural-derived flavonoids. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 22 (12), 1009–1019. doi:10.2174/1568026622666220221110506

Valathoor, M. N., and Venugopal, S. (2024a). In silico analysis of structure and function of hypothetical proteins in Salmonella typhimurium (SL1344). Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 17 (2), 643–650. doi:10.52711/0974-360X.2024.00100

Valathoor, M. N., and Venugopal, S. (2024b). Molecular docking and dynamic simulation approach to target Penicillin- binding protein 1B (LpoB) of Salmonella typhimurium with flavonoids. Curr. Pharm. Anal. 20 (8), 849–862. doi:10.2174/0115734129335204240919071902

Valathoor, M. N., and Venugopal, S. (2024c). Therapeutic potential of Colchicum luteum against flagellin (FliC) in salmonella typhimurium: an in silico approach. Lett. Drug Des. Discov. 21 (17), 3969–3982. doi:10.2174/0115701808334616240822055800

Valdés-Tresanco, M. S., Valdés-Tresanco, M. E., Valiente, P. A., and Moreno, E. (2021). Gmx_MMPBSA: a new tool to perform end-state free energy calculations with GROMACS. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 17 (10), 6281–6291. doi:10.1021/acs.jctc.1c00645

Van Der Spoel, D., Lindahl, E., Hess, B., Groenhof, G., Mark, A. E., and Berendsen, H. J. C. (2005). GROMACS: fast, flexible, and free. J. Comput. Chem. 26 (Issue 16), 1701–1718. doi:10.1002/jcc.20291

Vanommeslaeghe, K., Hatcher, E., Acharya, C., Kundu, S., Zhong, S., Shim, J., et al. (2010). CHARMM general force field: a force field for drug-like molecules compatible with the CHARMM all-atom additive biological force fields. J. Comput. Chem. 31 (4), 671–690. doi:10.1002/jcc.21367

Vaou, N., Stavropoulou, E., Voidarou, C., Tsakris, Z., Rozos, G., Tsigalou, C., et al. (2022). Interactions between medical plant-derived bioactive compounds: focus on antimicrobial combination effects. Antibiotics 11 (Issue 8), 1014. doi:10.3390/antibiotics11081014

Wise, R. (1999). A review of the mechanisms of action and resistance of antimicrobial agents. Can. Respir. J. 6 (Suppl. A), 20A–22A.

Zha, L., Garrett, S., and Sun, J. (2019). Salmonella infection in chronic inflammation and gastrointestinal cancer. Diseases 7 (1), 28. doi:10.3390/diseases7010028

Zhao, B. W., Su, X. R., Hu, P. W., Ma, Y. P., Zhou, X., and Hu, L. (2022). A geometric deep learning framework for drug repositioning over heterogeneous information networks. Briefings Bioinforma. 23 (6), bbac384. doi:10.1093/bib/bbac384

Zhao, B. W., Su, X. R., Yang, Y., Li, D. X., Li, G. D., Hu, P. W., et al. (2024). A heterogeneous information network learning model with neighborhood-level structural representation for predicting lncRNA-miRNA interactions. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 23, 2924–2933. doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2024.06.032

Zhong, Z. X., Zhou, S., Liang, Y. J., Wei, Y. Y., Li, Y., Long, T. F., et al. (2023). Natural flavonoids disrupt bacterial iron homeostasis to potentiate colistin efficacy. Sci. Adv. 9 (23), eadg4205. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adg4205

Keywords: subtractive genome, Salmonella typhimurium, food-based polyphenols, molecular docking, molecular dynamic simulation

Citation: Valathoor MN, Venugopal S and Rajan AP (2025) Subtractive genomic approach to uncover novel drug targets in Salmonella typhimurium and computational screening of food-based polyphenols as inhibitors. Front. Bioinform. 5:1695217. doi: 10.3389/fbinf.2025.1695217

Received: 29 August 2025; Accepted: 24 October 2025;

Published: 03 December 2025.

Edited by:

Bo-Wei Zhao, Zhejiang University, ChinaReviewed by:

Yue Yang, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), ChinaHuifeng Zhao, Zhejiang University, China

Copyright © 2025 Valathoor, Venugopal and Rajan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anand Prem Rajan, YXByZGJ0QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

†ORCID: Mohammed Naveez Valathoor, orcid.org/0000-0001-8901-9602; Subhashree Venugopal, orcid.org/0000-0001-7713-5737; Anand Prem Rajan, orcid.org/0000-0001-5659-0386

Mohammed Naveez Valathoor

Mohammed Naveez Valathoor Subhashree Venugopal

Subhashree Venugopal Anand Prem Rajan

Anand Prem Rajan