- School of Computer Science and Engineering, Vellore Institute of Technology, Vellore, India

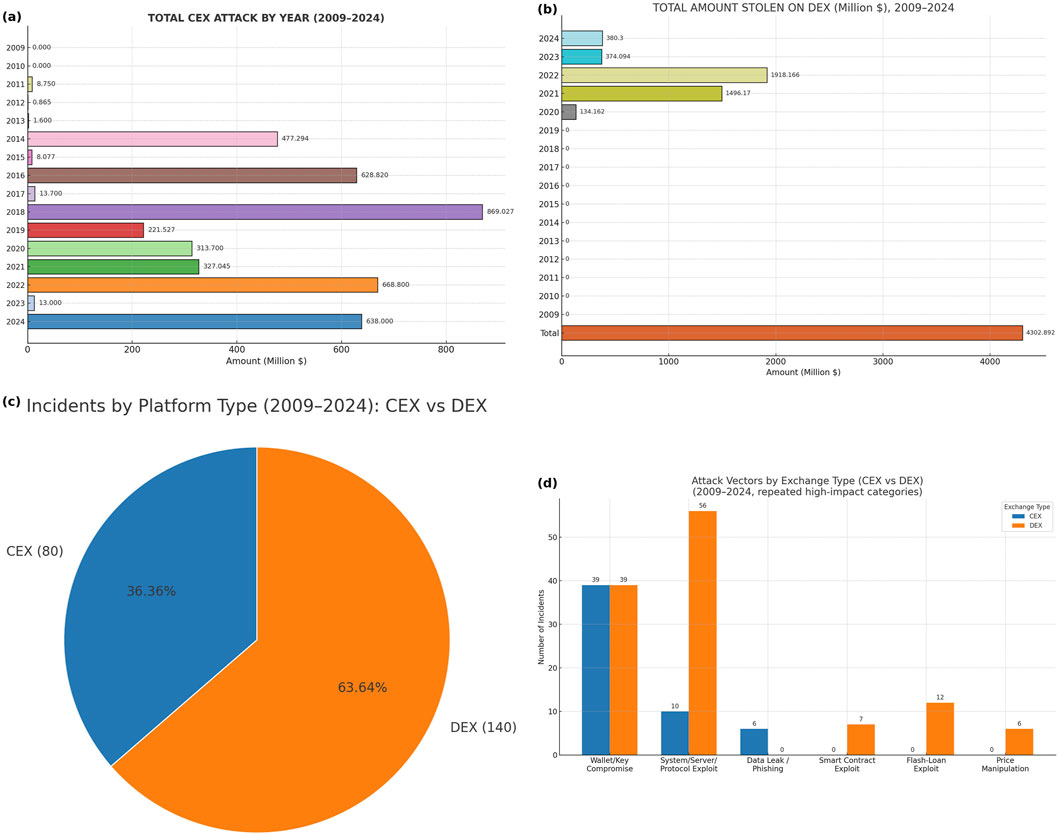

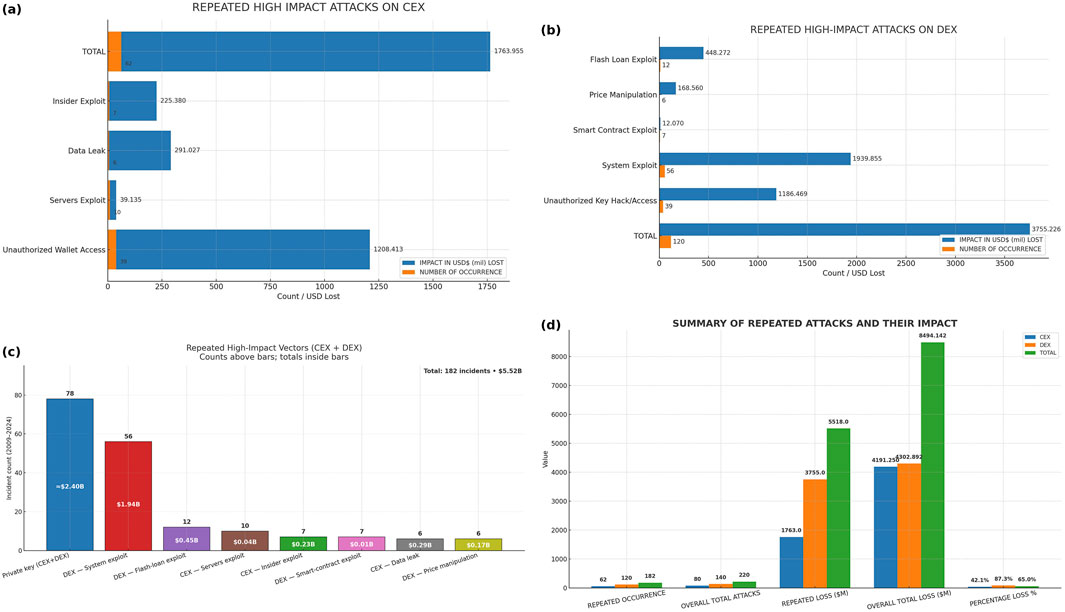

Cryptocurrency exchanges are integral to the digital asset economy; however, their rapid growth has been accompanied by recurrent high-impact cyberattacks that erode trust and inflict substantial losses. Guided by the PRISMA-ScR framework, this review systematically screened peer-reviewed and industry sources to construct a validated dataset of 220 major incidents (2009–2024) across centralized (CEX) and decentralized (DEX) exchanges. We classify attack vectors, analyze repeated high-impact patterns, and identify systemic vulnerabilities spanning cryptographic mechanisms and exchange infrastructure. Across CEX platforms, four of ten identified attack types accounted for 62 of the 80 incidents and approximately $1.764 billion in losses (42.1% of the $4.191 billion CEX total). Across DEX platforms, five of eighteen attack types were responsible for 120 of 140 incidents, totaling $3.755 billion (87.3% of the $4.303 billion DEX total). The overall losses sum to $8.494 billion across 220 incidents (80 CEX; 140 DEX). Repeated vectors comprised 182/220 incidents and $5.519 billion (65.0%) of losses, dominated by wallet/key compromise (78 incidents; $2.394 billion) and DEX system/server/protocol exploits (56 incidents; $1.939 billion); these two classes account for 134/182 repeated incidents (79.1%) and $4.333 billion (78.5%) of repeated losses. We examine the susceptibility of cryptographic defenses to emerging quantum adversaries and assess the exchange readiness for post-quantum threats. This study is the first to systematically compile and quantitatively analyze cybercrime incidents affecting both centralized and decentralized cryptocurrency exchanges in a unified dataset, enabling unprecedented comparability of systemic risks with actionable insights for cybersecurity researchers, regulators, and exchange operators seeking quantum-safe infrastructure evolution.

1 Introduction

Cryptocurrencies and cryptocurrency exchange platforms (CExPs), encompassing both centralized (CEX) and decentralized (DEX) exchanges, are intrinsically linked, with exchanges providing the essential infrastructure that facilitates transactions and drives global adoption (Kim and Lee, 2018). In this study, we used CExPs when referring to exchanges generically and CEX/DEX when distinguishing between the two types. Cryptocurrency has become a global phenomenon in the 21st century (Corbet et al., 2019b) and has attracted increasing levels of cybercrime, particularly against CExPs, which serve as the primary conduits for cryptocurrency transactions (Vital, 2022; Manimuthu et al., 2019; Connolly and Wall, 2019). Despite the challenges of transacting outside formal venues, the sustained growth in the acceptance of cryptocurrencies as an alternative to fiat currency is underpinned by the security and trust provided by exchanges (Bucko et al., 2015; Kawai et al., 2023). In practice, CExPs expand cryptocurrency usability by offering user-friendly rails for liquidity, rapid settlement, and broad accessibility (Oliva et al., 2019; Arli et al., 2021) (Supplementary Tables S1, S2).

Since 2009, at least 220 high-impact cyberattacks have been reported in exchanges, with a total of approximately $8.494 billion (Chainalysis, 2022; Vidal-Tomás, 2022; Giechaskiel, 2016). These incidents span both centralized exchanges (CEXs) and decentralized exchanges (DEXs), the two dominant architectures in the ecosystem, where CEXs are custodial order-book venues and DEXs are non-custodial smart-contract protocols (e.g., AMMs or on-chain order books). Together, CEX and DEX represent the core infrastructure of the global cryptocurrency economy, serving over 500 million users by 2024 and facilitating the majority of cryptocurrency liquidity and settlement (IMARC Group, 2023; Jani, 2018). Other venues, such as OTC desks, P2P platforms, and custodial brokers, exist, but their transaction volumes and user bases remain marginal compared to CEX and DEX. Hence, this study focused on these two dominant exchange types.

Exchanges are integral to digital finance, enabling the buying, selling, and conversion of assets such as Bitcoin and Ethereum (Marella et al., 2021; Rejeb et al., 2021), and they play a central role in liquidity formation, price discovery, and on-/off-ramping between fiat and crypto (Chutipat et al., 2023). As of May 2024, over 500 exchanges were operating globally (CoinMarketCap, 2023; Future Market Insights, 2023; Triple-A Technologies Pte. Ltd., 2024). Binance led spot and derivatives activities, often processing tens of billions of dollars in daily volume across markets, while other major venues, including Coinbase, Bybit, and Kraken, contributed materially to market liquidity and user trust (Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance, 2017a).

By late 2024, the global crypto market capitalization was approximately $2 trillion (Chainalysis, 2023b). Annual trading volumes further highlight the market’s scale: in 2024 alone, the top-15 centralized spot exchanges (CEXs) processed $18.8 trillion; the top-10 decentralized exchanges (DEXs) handled $1.76 trillion; and derivatives trading volumes were even higher, reaching $58.5 trillion on the top-10 centralized exchanges offering perpetual contracts and $2.9 trillion on their decentralized counterparts (CCData, 2025; DefiLlama, 2025a; DefiLlama, 2025b; DefiLlama, 2025c). In parallel, user adoption is expected to expand to an estimated 600 million global crypto users by the end of 2024 (IMARC Group, 2023; Jani, 2018). The growing participation of both retail and institutional investors further amplifies the systemic importance of crypto exchanges (Coinpedia, 2023; Chainalysis, 2023a).

The same characteristics that make exchanges efficient, high-throughput, deep liquidity, and global access also increase their attractiveness to attackers (Al-Amri, 2019; Oosthoek, 2021; Ahuja, 2023; Basilan, 2024). As the value of assets under custody increases, there is an incentive for sophisticated attacks (Rot and Blaicke, 2019). The pseudonymity and cross-jurisdictional nature of blockchain flows complicate asset tracing and recovery, whereas weaknesses in wallet/key management, authentication, and transaction-validation pipelines remain persistent pressure points (Crystal Blockchain, 2024b; Hedge with Crypto, 2024; Crystal Blockchain, 2024a; Sigurdsson et al., 2020; Adamik and Kosta, 2019; Shaji et al., 2022). Historically, attacks have included phishing, credential theft, malware, insider abuse, protocol and smart contract exploits, and large-scale DDoS events that exploit the gaps in both operational controls and cryptographic guardrails (Feder et al., 2017; Alia, 2014). In 2024 alone, over ten major breaches were recorded, with losses exceeding $1.018 billion (Berry, 2022); a notable example is the WazirX incident of July 2024 (approximately $230million) (Crystal Intelligence, 2024). These incidents further reveal critical weaknesses in wallet security (Erinle et al., 2023), authentication protocols, and transaction validation mechanisms (Homoliak and Perešíni, 2024), and continue to drive regulatory responses (e.g., KYC/AML regimes) across jurisdictions (Mohsin, 2022; Mateen, 2023; Ruiz et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2023; Soana, 2024), which often address symptoms rather than root causes in the system architecture.

An additional risk acceleration is the prospective impact of quantum computing (Faruk et al., 2022; Bergstrom, 2024). Algorithms such as Shor and Grover threaten the hardness assumptions of widely deployed schemes (RSA and ECC) with implications for key custody, signatures, and consensus security (Fernández-Caramés, 2020; Easa et al., 2023; Vasavi and Latha, 2019). Given the “harvest-now, decrypt-later” risk, the key material exfiltrated today can be decrypted by future quantum adversaries, thereby increasing the urgency for migration to post-quantum cryptography (PQC) (Roy, 2019; Thanalakshmi et al., 2023). Leading PQC families, including lattice-based KEMs and signatures, hash-based signatures, and multivariate schemes, offer candidates for hardening key exchanges, authentication, and protocol design.

Against this backdrop, prior reviews have often conflated exchange-related incidents with wallet-only breaches or broader DeFi exploits, limiting comparability and obscuring systemic vulnerabilities specific to exchange infrastructure. Wallet-only breaches are often driven by end-user errors, such as private key mismanagement or phishing, whereas exchange breaches expose deeper architectural flaws in custodial systems, smart contracts and liquidity protocols. By isolating exchange-specific incidents, this study provides the first PRISMA-ScR scoping review that systematically maps systemic risks across CEX and DEX platforms. Furthermore, the 220 incidents analyzed not only revealed recurrent attack vectors but also highlighted the fragility of cryptographic mechanisms that face existential threats from quantum-capable adversaries. Linking historical breach patterns to quantum-era risks strengthens the case for urgent migration to post-quantum cryptography in exchange infrastructure. This dual focus, systemic cyber risk, and quantum-era cryptographic fragility position the study to inform both immediate resilience strategies and long-term PQC migration pathways.

Despite the growing body of research on blockchain security, two critical research gaps remain unaddressed. First, the literature lacks a unified, longitudinal synthesis that isolates exchange-specific cyber incidents and compares systemic vulnerabilities across CEX and DEX architectures. Second, very few studies integrate post-quantum cryptographic readiness into the analysis of exchange security, even though quantum threats directly challenge the cryptographic foundations of trading, custody, and consensus. Addressing these interlinked gaps is essential to align historical evidence with the technological transition toward quantum-resilient infrastructures and to guide both academic inquiry and regulatory preparedness in the digital-asset domain.

This review critically investigates the evolving cybersecurity dynamics of cryptocurrency exchanges by examining both their historical vulnerabilities and their readiness for quantum-era threats. In direct response to the identified research gaps, the study pursues two overarching aims: first, to provide a unified, exchange-specific synthesis that compares systemic vulnerabilities across centralized (CEX) and decentralized (DEX) platforms; and second, to evaluate the preparedness of exchange cryptographic infrastructures for post-quantum migration. Specifically, we (i) conduct a systematic review and classification of repeated high-impact incidents involving exchanges from 2009 to 2024, (ii) identify common vulnerabilities and recurring attack vectors that have compromised exchange security, (iii) assess quantum-era risks to current cryptographic infrastructures, and (iv) offer actionable post-quantum–ready recommendations for exchanges and policymakers (Navarro, 2019). Unless otherwise stated, dollar amounts are USD (nominal, not inflation-adjusted), and reported volumes refer to calendar year 2024 benchmarks (CCData, 2025; DefiLlama, 2025a; DefiLlama, 2025b; DefiLlama, 2025c).

Beyond addressing these gaps, this study contributes to both theory and practice. Theoretically, it extends the understanding of cybersecurity resilience in digital-asset infrastructures by providing a longitudinal, exchange-specific taxonomy of high-impact incidents. Methodologically, it demonstrates how a PRISMA-ScR framework can be adapted to synthesize technical breach data across heterogeneous blockchain ecosystems. Managerially and for policy, the findings generate actionable insights for exchange operators, cybersecurity agencies, and regulators seeking to strengthen governance standards and guide post-quantum transition strategies. Collectively, these contributions position the review as a reference baseline for future empirical, regulatory, and cryptographic research on exchange security.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the background and related studies. Section 3 details the PRISMA-ScR scoping methodology and data extraction pipeline. Section 4 briefly introduces exchange platforms (CEX/DEX), security/architecture, and frames the high-impact crimes. Section 5 presents the incident corpus and results (taxonomy, trends, cross-platform comparisons, losses, and repeated vectors). Section 6 analyzes the attack techniques and patterns, whereas Section 7 emphasizes classical cryptographic vulnerabilities and defenses. Section 8 expands on post-quantum threats and the PQC readiness of the CExPs. Section 9 discusses the synthesis of the results, limitations, research gaps, and recommendations. Finally, Section 10 concludes the study.

2 Background and related work

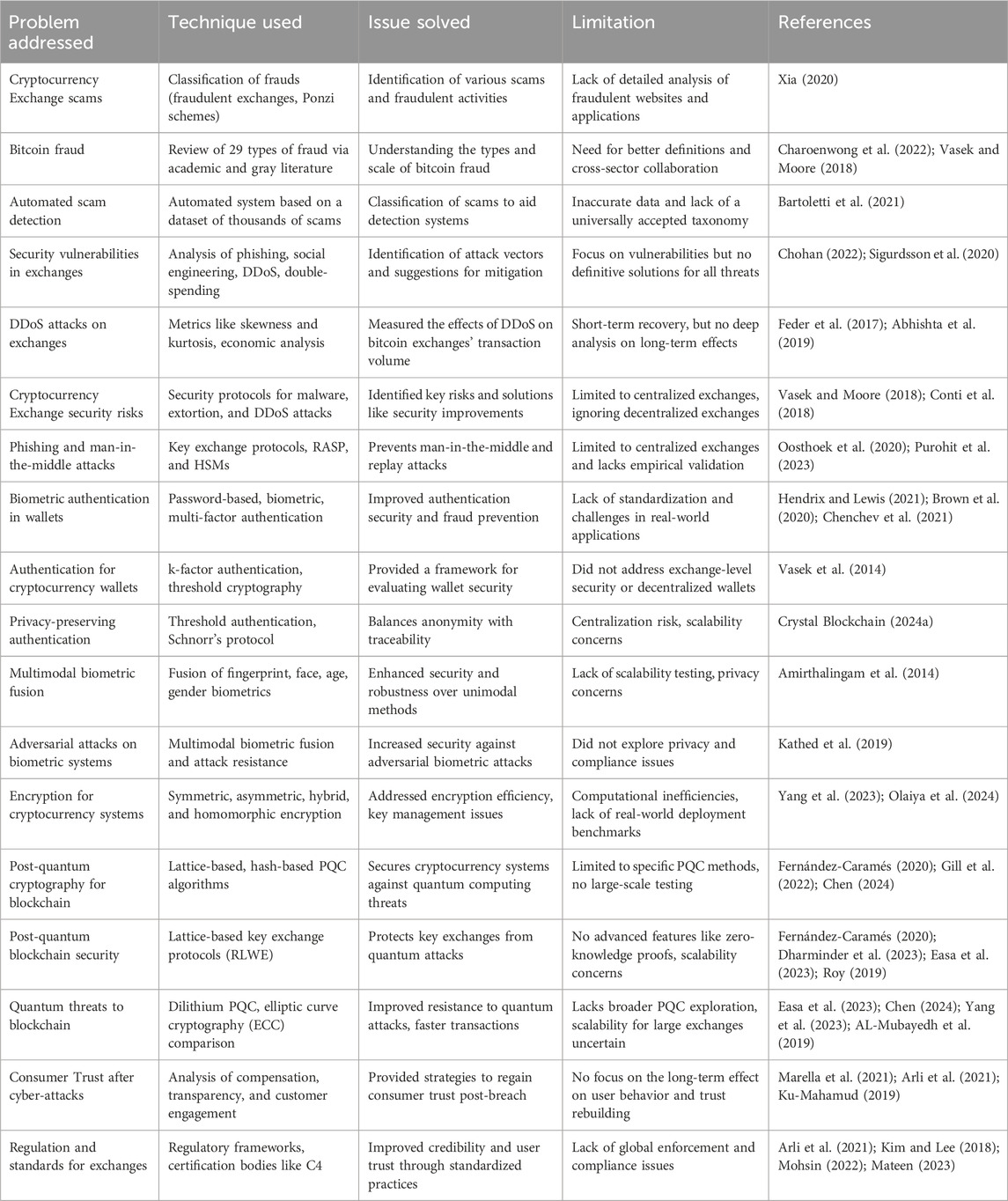

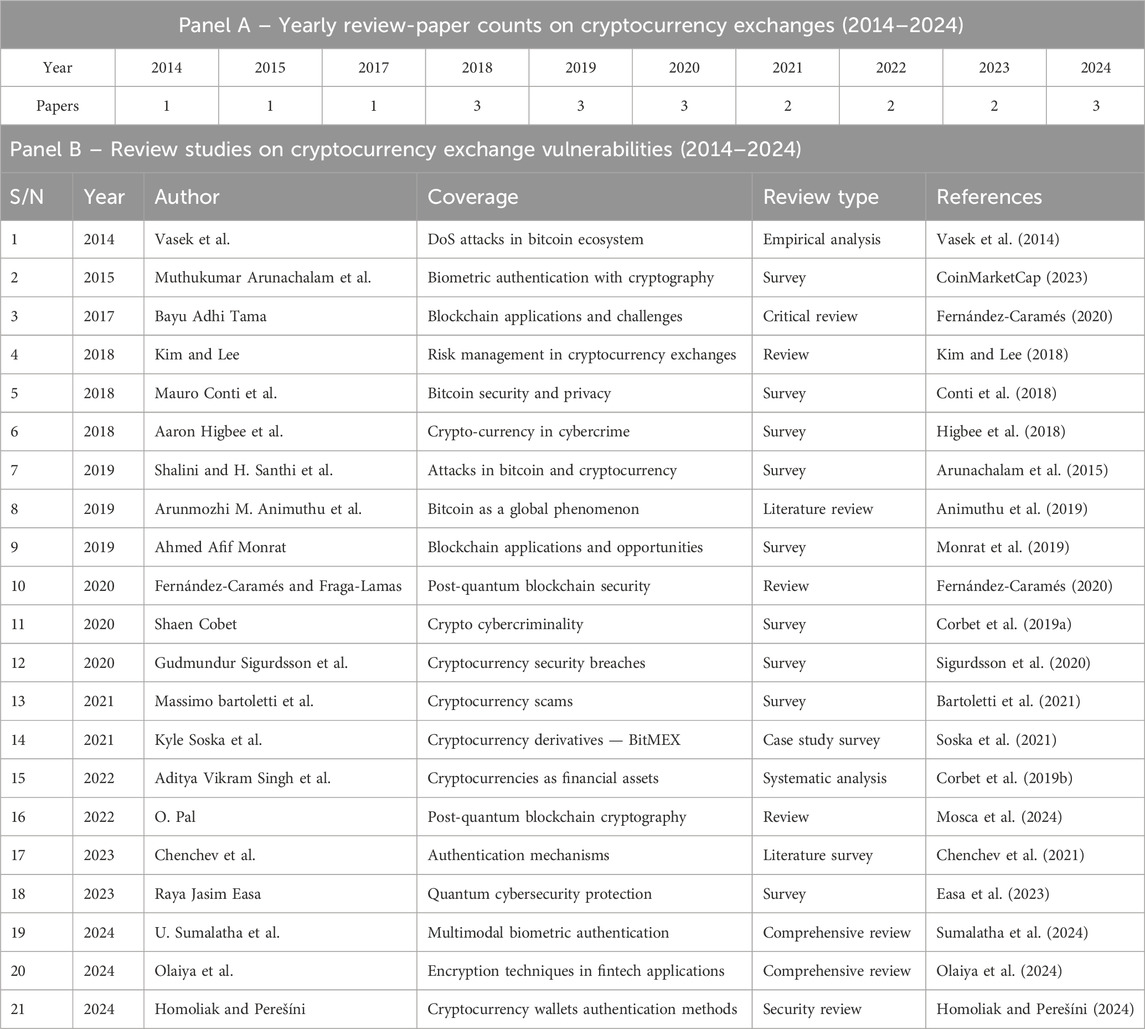

Although many publications discuss cryptocurrencies and related crimes, relatively few have analyzed the detailed mechanics of crimes against cryptocurrency exchange platforms (CExPs). Therefore, we review the literature most relevant to exchange security, emphasizing recent studies (2018–2024), which are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Review studies on cryptocurrency exchange vulnerabilities (2014–2024). Panel A reports yearly counts; Panel B lists study-level details.

Rising concerns over CExP security have driven studies on scams, cyberattacks, authentication, and cryptography, aimed at improving transparency, accountability, and resilience against both classical and quantum-enabled threats (Shalini and Santhi, 2019). The literature is synthesized below by theme:

2.1 Cryptocurrency exchange vulnerabilities and attacks

Vasek and Moore classified scams into four categories: fraudulent exchanges, Ponzi schemes, mining scams, and scam wallets, highlighting definitional challenges and the absence of systematic classifications (Vasek and Moore, 2018; Nabilou, 2020). Trozze et al. identified 29 types of fraud across academic and gray sources, underscoring research growth and the need for clearer definitions and collaboration (Trozze et al., 2022). Bartoletti et al. propose automated scam detection but note noisy labels and lack of a universal taxonomy (Bartoletti et al., 2021). Sigurdsson et al. (2020) and Chohan (2022) examined vulnerabilities (DDoS, phishing, social engineering, malleability, and double spending) paired with cost-raising countermeasures. Feder et al. analyzed the impact of DDoS on Bitcoin exchanges (Feder et al., 2017), whereas Abhishta et al. found that the activity typically normalizes within a day (Arli et al., 2021). Vasek et al. further highlighted malware and extortion, noting that theft declines after security upgrades (Vasek et al., 2014). Gottipati (2020) designed a defense model using Runtime Application Self-Protection (RASP) and Hardware Security Modules (HSMs), but focused only on centralized exchanges. Smith and Kahn De Saint Guilhem et al. (2020) proposed a composable framework for key exchange against man-in-the-middle attacks, although there is a lack of deployment evidence.

Gap: These studies propose defenses but none compile a longitudinal, unified dataset of high-impact crimes across both CEX and DEX.

2.2 Authentication and security in cryptocurrency exchanges

Chenchev et al. (2021) surveyed wallet authentication methods such as passwords, biometrics, MFA, blockchain-based methods, and stress persistent weaknesses. Homoliak and Perešíni, 2024 introduced “k-factor” authentication using threshold cryptography but focused narrowly on wallets. Doe and Smith Zhang et al. (2024) propose a privacy-preserving, threshold authentication framework, though centralization and scalability remain issues. Alghamdi et al. (2024) show multimodal biometric fusion reduces attack success rates but overlook governance and regulation. Goh et al. (2022) developed a multimodal fingerprint/iris framework with Adaptive Feature Hashing, offering unlinkability but lacking exchange-scale testing. Brown et al. (2020) integrate biometrics with blockchain and ML but omit stress tests and compliance considerations. Vasavi and Latha (2019) explored multimodal fusion with RSA, achieving accuracy but at the cost of latency.

Gap: Authentication research is fragmented and not systematically tied to large-scale CEX/DEX breach data.

2.3 Encryption techniques and their challenges

Olaiya et al. (2024) surveyed symmetric, asymmetric, hybrid, and homomorphic encryption and noted the performance, key management, and integration trade-offs, whereas advanced paradigms (homomorphic and PQC) remain early in deployment. However, empirical benchmarks and migration strategies are lacking.

Gap: Few works map encryption weaknesses directly to the high-impact vectors observed in CEX/DEX incidents.

2.4 Quantum threats and post-quantum cryptography (PQC)

Shor-type attacks expose RSA/ECDH/ECDSA, prompting studies on PQC for exchanges (Gill et al., 2022). Chen (2024) advocated for PQC signatures (Dilithium) but omitted broader PQC families or hybrid migration paths. Saha et al. integrate lattice- and hash-based PQC into blockchain, showing performance gains but neglecting multivariate/code-based families and live deployment (Saha et al., 2023). Other studies have highlighted PQC’s importance of PQC against Shor and Grover (Rosch-Grace and Straub, 2021). Chen Dharminder et al. (2023) proposed an RLWE-based protocol with good performance, but it lacked privacy features and large-scale optimization. Yi (2022) applies lattice-based cryptography to SIoT, improving key exchange, but exchange-scale feasibility is untested.

Gap: PQC studies focus on design but rarely connect with empirical exchange breach data which our dataset provides this missing link.

2.5 Consumer trust and accountability in exchanges

Marella et al. (2021), Arli et al. (2021) showed that trust recovery requires compensation, not apologies. Chohan (2022) called for transparency, monitoring, and accountability.

Gap: Trust research seldom links erosion directly to the repeated scale of CEX/DEX incidents.

2.6 Regulatory measures and global standards

Bucko et al. (2015) discussed certification bodies (e.g., C4) and global harmonization efforts (Xiong and Luo, 2024; Caliskan, 2022).

Gap: Regulatory work proposes frameworks but lacks quantitative grounding in the historical trajectory of high-impact incidents.

Synthesis of Gaps: Collectively, prior research covers scams, authentication, encryption, PQC, trust, and regulation. However, there is no comprehensive longitudinal dataset of high-impact incidents across the CEX and DEX. This study addresses this gap by compiling the largest unified dataset of 220 exchange-specific incidents (2009–2024), enabling cross-architecture comparisons, identification of repeated vectors, and contextualization of quantum-era risks (Table 2).

3 Review methodology

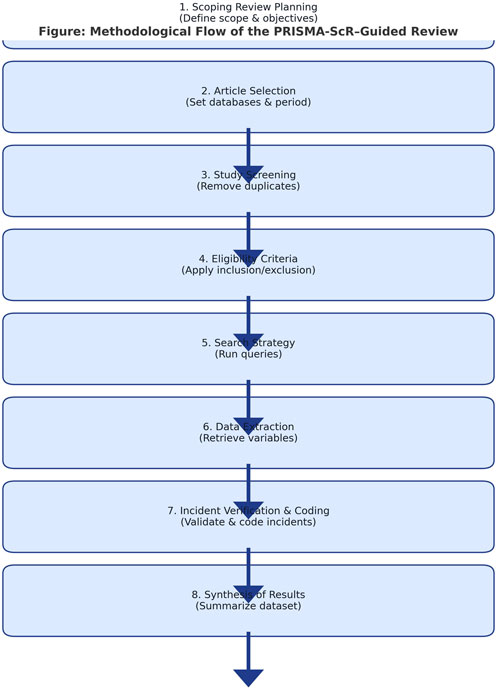

Figure 1 presents an overview of the PRISMA-ScR–guided methodology adopted in this study, illustrating the sequential stages from scoping and article selection to eligibility screening, data extraction, incident verification, and synthesis of results.

3.1 Scoping review

Scoping reviews systematically map the breadth and nature of research on established or emerging topics using an iterative, structured approach (Sarkis-Onofre et al., 2021; Mattos et al., 2023). This study aimed to analyze, evaluate, and classify existing studies on crimes against cryptocurrency exchange platforms (CExPs). We reviewed both peer-reviewed and gray literature sources (Vergara-Merino et al., 2021) on cybercrimes against exchanges (Souza et al., 2022). The review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines, with eligibility criteria defined a priori to ensure scope alignment and reproducibility (Tricco et al., 2016). In this study, “crime” is defined as any act (fraud, hacking, theft, or cyber-attack) committed to gain financial or asset benefits from exchanges.

3.2 Article selection methods

We conducted a scoping review of the academic and gray literature on crimes against cryptocurrency exchange platforms, focusing on repeated high-impact attack vectors affecting centralized (CEX) and decentralized (DEX) exchanges between 2009 and 2024. This review adhered to the PRISMA-ScR guidelines (Munn et al., 2018; Munn et al. 2022). Eligibility was determined based on publication type, language, topical relevance, and direct linkage to exchange securities.

3.3 Study selection

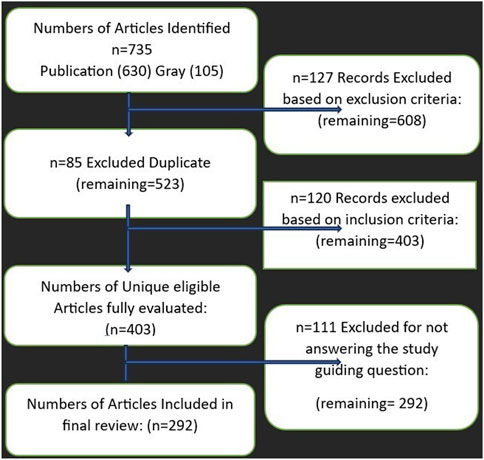

Searches were performed in the Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar databases until 31 December 2024. In total, we identified 735 records (630 academic and 105 Gy literature articles). Duplicates were removed in Microsoft Excel using a two-pass procedure (pass 1: DOI-normalized exact match; pass 2: title-normalized + year for records without a DOI). All unique titles and abstracts were screened.

Academic literature. Of the 630 screened academic records, 301 underwent full-text reviews. After screening, 214 articles met all inclusion criteria and were retained, while 87 were excluded.

Gray literature. Of the 105 Gy records screened, 95 proceeded to full-text eligibility, 78 were finally included, and 17 were excluded during the title/abstract screening.

A total of 292 sources (214 academic and 78 Gy) met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review. The authors independently screened the studies, and disagreements were resolved through discussion. As shown in Figure 2, these counts align with the PRISMA-ScR flow diagram, ensuring full transparency at each stage.

3.4 Eligibility criteria

Although cryptocurrency security breaches occur across wallets, tokens, and broader DeFi protocols, this review explicitly focuses on exchange-centric incidents (centralized exchanges (CEX) and decentralized exchanges (DEX)). Wallet-only breaches were excluded because they primarily involve user-side vulnerabilities (e.g., private key mismanagement and phishing) rather than systemic flaws in the exchange infrastructure. Including such cases would blur the scope and reduce the comparability of the aggregated loss data. By restricting the inclusion to exchange-focused incidents, the review maintains analytic consistency with PRISMA-ScR and ensures that the findings remain directly relevant to exchange resilience, regulatory oversight, and post-quantum preparedness.

Only studies written in English were included. Eligible sources comprised peer-reviewed journal articles, conference papers, and formal reports (e.g., CERT advisories, technical white papers, and documented incident post-mortems) classified as gray literature. Editorials, opinion pieces, marketing materials, newsletters, and news articles were excluded from the study.

Topically, the included studies had to address crimes against CExPs (CEX or DEX) or their direct security posture (e.g., wallet/key management within exchanges, smart contract exchange logic, or bridges/oracles when tied to exchange incidents). We also included studies on quantum threats relevant to exchanges when they explicitly connected PQ/quantum risks (e.g., RSA/ECC compromise, Grover-related symmetric considerations) to exchange infrastructures or incident classes.

3.5 Search strategy

The complete database-specific queries are listed in Supplementary Table S3. Because Google Scholar restricts queries to approximately 256 characters, we executed the query set as multiple searches using the quoted phrases to control drift. The search was restricted to records published between January 2009 and December 2024. For gray literature, we restricted the results to English-language PDF files to ensure reproducibility. Both academic and gray searches included peer-reviewed articles, conference papers, theses, monographs, and technical reports. Duplicates across databases were systematically resolved using the two-pass procedure described above. Disagreements at the full-text inclusion stage were resolved by consensus.

3.6 Procedure for data extraction

As presented in Supplementary Table S4, we meticulously retrieved pertinent information for the scoping review by conducting structured searches across the Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar. Multiple search strings were combined to extract relevant records. Google Scholar, which offers broader indexing coverage, provided the most robust results among the databases consulted.

3.7 Incident verification and coding

As shown in Figure 1, all steps were executed sequentially to ensure methodological transparency and reproducibility. Each incident was cross-verified across at least two independent sources such as exchange post-mortems, auditor reports, and regulatory filings to ensure authenticity and avoid double counting. Incidents were classified as major if the reported or independently confirmed financial loss exceeded USD 50,000 or caused service disruption exceeding 24 h. A standardized coding sheet was developed to capture the following variables: year, exchange type (CEX/DEX), loss magnitude, attack vector, recurrence status, and cryptographic relevance. Two reviewers independently coded all incidents, and intercoder agreement was assessed using percentage concordance (97%). Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion to maintain reliability and alignment with PRISMA-ScR transparency principles.

3.8 Scoping review results

Using the PRISMA-ScR framework (Stovold et al., 2014; Page et al., 2021), our systematic review process identified 735 sources (630 academic and 105 Gy). After removing duplicates and applying title/abstract and full-text screening, we included 292 sources (214 academic, 78 Gy). As shown in Figure 2, these numbers are aligned with the PRISMA-ScR flow diagram.

4 Brief history of cryptocurrency exchanges and cybersecurity crimes

4.1 Historical overview of cryptocurrency exchanges

When Bitcoin (BTC) was launched in 2009, it had no fixed market value and could only be obtained through mining or high-risk trades (Nakamoto, 2009; Wang et al., 2024b). The early exchange history was marked by fraud, hacks, and legal challenges, laying the groundwork for today’s global infrastructure (Al-Amri, 2019; Caliskan, 2021). Currently, more than 600 exchanges operate globally (Bartoletti et al., 2021; CoinMarketCap, 2025). Early transactions, such as those between Hal Finney and Satoshi Nakamoto on 12 January 2009, were experimental (Ruoti et al., 2020).

Before the 2008 Bitcoin white paper and 2009 Genesis Block Nakamoto (2009), trading occurred informally via forums or IRC and relied on trust. The first exchange, bitcoinmarket. com, was launched in March 2010 (Cryptohopper, 2023; World.org, 2023). By 2011, Mt. Gox had become the largest exchange and the site of the first major cybercrime (CoinDesk, 2023; Morin et al., 2023; Dimpfl and Flad, 2020). Hackers exploited a compromised hot wallet, crashing BTC prices from $17 to nearly zero and leaking user data. Despite this, Mt. Gox still handled 70% of global Bitcoin trade in 2013 before registering with FinCEN. Over time, exchanges have evolved with a greater focus on user experience and security (Gayathri et al., 2023; Fang et al., 2022). Leading platforms have introduced secure trading procedures (Watorek et al., 2020), although the regulatory burdens vary across jurisdictions (Mohsin, 2022).

4.1.1 CEX and DEX platforms

Cryptocurrency exchanges are privately run platforms in which users trade cryptocurrencies against fiat currencies or other assets (Czapliński et al., 2019; Bhaskar and Chuen, 2024). Orders can be executed at set prices or spot rates (Bentov et al., 2019; Keller and Scholz, 2019). Two main models exist: centralized (CEX) and decentralized (DEX) (Takahashi et al., 2019). Both aim to ensure liquidity, security, and rapid settlement, with some exchanges evolving into full trading platforms that offer analytical tools.

4.1.2 Centralized exchanges (CEXs)

In CEXs, a single authority manages the accounts and transactions (Zhou et al., 2022). They function like digital stock markets, earning fees and commissions (Patashkova et al., 2021). Its advantages include high liquidity, faster fund recovery, and selective asset listings. Drawbacks include custodial risks, centralized storage of sensitive data, and a history of price manipulation. The major CEXs include Binance, Bybit, Coinbase, Kraken, and KuCoin (Fu et al., 2022; Eigelshoven et al., 2021).

4.1.3 Decentralized exchanges (DEXs)

DEXs operate on distributed ledger technology without a central authority (Jain et al., 2021; Victor and Weintraud, 2021). Users control their keys and trade directly from their wallets, bypassing intermediaries and KYC requirements (Xu et al., 2023). They typically allow swaps within the same blockchain, such as Ethereum-based tokens. Its strengths include full custody, lower fees, higher privacy, and distributed hosting (Patel et al., 2019; Tripathi et al., 2023). Its weaknesses include low liquidity and limited interoperability. Examples include Uniswap, PancakeSwap, dYdX, and Kyber (Corbet et al., 2019a).

4.2 Overview of exchange security

4.2.1 Exchange architecture

Exchanges integrate multiple layers to enable asset trading, such as Bitcoin and Ethereum (Marella et al., 2021; Navarro, 2019). Their design combines security and efficiency across interconnected components. Supplementary Table S8 summarizes the layers, definitions, threats and defenses.

5 Cybersecurity incidents in cryptocurrency exchanges

From 2009 to 2024, cryptocurrency exchange platforms reported at least 220 high-impact security incidents, including hacks, thefts, scams, fraud, and breaches, arising from exploited vulnerabilities (Scharfman, 2023; Murugappan et al., 2023). The quantified losses across these incidents totaled $8.494 billion from 2009 to 2024 (Chainalysis, 2022; Chainalysis 2023b; Charoenwong et al., 2022; Chainalysis Team, 2024). As of 25 August 2023, the ecosystem comprised

Supplementary Table S1 (CEX) and S2 (DEX) outline the full set of 220 major incidents with a cumulative loss of $8.494 billion from 2009 to 2024 (Aspris et al., 2021; Manthovani et al., 2023). Of these, 80 incidents involved CEX and 140 involved DEX (Navamani, 2021).

5.1 Incidents classification

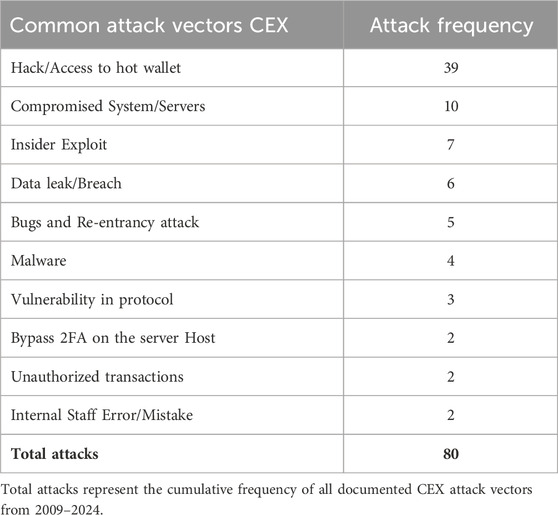

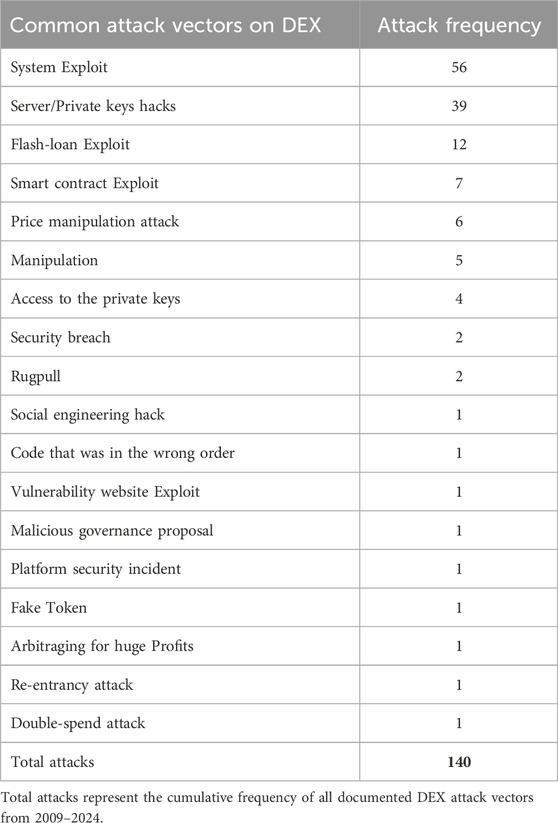

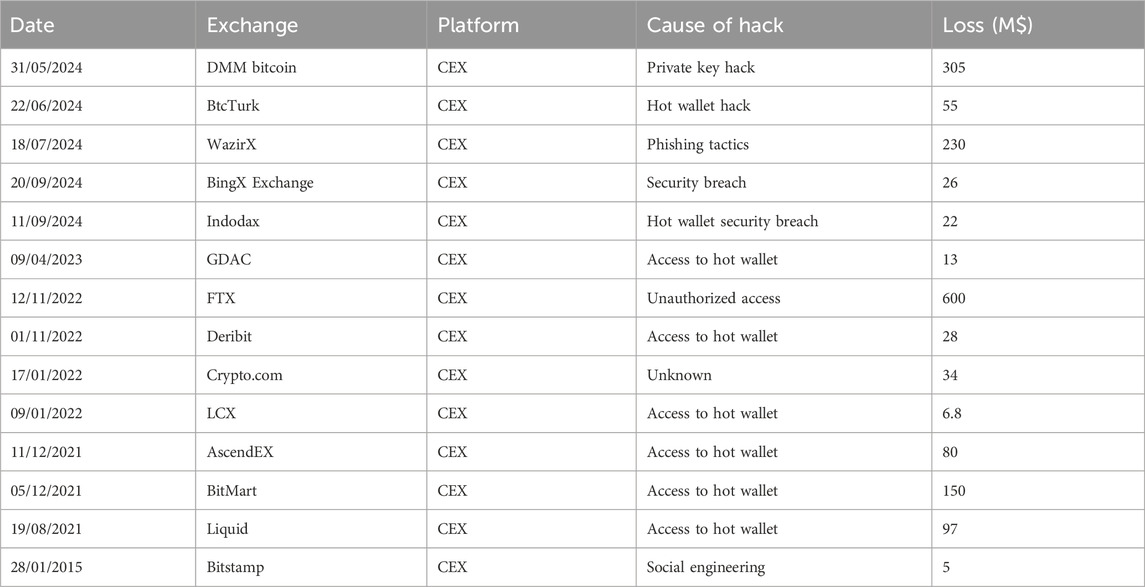

Tables 3, 5 summarize the incident taxonomy and counts for CEX and DEX respectively; the full record of 220 incidents (CEX 80; DEX 140) is provided in Supplementary Table S1 (CEX) and S2 (DEX).

Table 3. Summarized high impact CEX exchange crimes from 2009–2024. Full list of incidence in Supplementary Table S1.

5.1.1 Corpus and sources

We compiled incidents from 2009–2024 using peer-reviewed studies and preprints, auditor/forensic and blockchain-analytics reports, official exchange disclosures and post-mortems, regulatory/court materials, reputable industry media, and security research blogs. This comprehensive multi-source triangulation ensures that the resulting dataset is not only the broadest compiled to date but also systematically validated and de-duplicated, distinguishing it from earlier fragmented surveys. The specific sources that populated the database were as follows: Corbet et al. (2019b); Manimuthu et al. (2019); Connolly and Wall (2019); Bucko et al. (2015); Chainalysis (2022); Vidal-Tomás (2022); Marella et al. (2021); Chohan (2022); Chainalysis (2023b); Chainalysis (2023a); Oosthoek (2021); Anita (2019); Bartoletti et al. (2021); Crystal Blockchain (2024b); Hedge with Crypto (2024); Crystal Blockchain (2024a); Sigurdsson et al. (2020); Feder et al. (2017); Berry (2022); Crystal Intelligence (2024); Navarro (2019); Shalini and Santhi (2019); Trozze et al. (2022); Vasek et al. (2014); CoinMarketCap (2025); Bit2Me Academy (2016); Cryptohopper (2023); World.org (2023); CoinDesk (2023); Fu et al. (2022); Eigelshoven et al. (2021); Corbet et al. (2019a); Charoenwong et al. (2022); Chainalysis Team (2024); Hamrick et al. (2021); Aspris et al. (2021); Manthovani et al. (2023); Abhishta et al. (2019); Panjwani (2023); Bhusal (2021); Blockchain (2022); Minto (2022); Badaw et al. (2020); Sengupta et al. (2020); Nabilou (2020); Patel (2022); Horch et al. (2022); Conti et al. (2018); Xia (2020); Oosthoek et al. (2020); Kasera (2020); Tandon and Nayyar (2019); Astrakhantseva et al. (2021); Shevchenko et al. (2022).

5.1.2 Inclusion and exclusion

We included exchange-platform security incidents (CEX or DEX) with (i) a clearly described compromise vector and (ii) a documented or conservatively estimated their financial impacts. We excluded non-exchange scams with no platform compromise, purely off-chain fraud that does not involve exchange infrastructure or duplicates.

5.1.3 Screening and de-duplication

All candidate items were screened and then de-duplicated by matching venue + date/time window + transaction or On-chain evidence and narrative details. Conflicting loss figures were reconciled by preferring primary disclosures and multi-source concordance, and unresolved ranges were conservatively recorded. This process yielded 220 unique incidents.

5.1.4 Normalization and coding

For each incident we coded: platform type (CEX/DEX), venue, date (UTC), region, attack vector (mapped to the 10-vector CEX and 18-vector DEX taxonomies), loss amount (USD; normalized at the time of reporting), and citation set. Ambiguous geography is tagged as unknown/global. The resulting database underlies all the figures and tables in §5.1.7.1–§5.1.7.6.

5.1.5 Focus on repeated high-impact vectors

From this corpus, we flagged vectors that recurred more than four times and caused losses exceeding $50,000 per incident (excluding non-property crimes). Applying this dual threshold ensures an analytical focus on patterns that are both persistent and financially material while filtering out one-off or low-impact breaches. These repeated high-impact records (CEX top-4; DEX top-5) drive the comparative analyses and the bar charts in §5.1.7.5–5.1.7.6, including the cross-platform private key (CEX + DEX) aggregate (78 incidents;

5.1.6 Data generation and curation

The curated incident lists for CEX (Supplementary Table S1; 2009–2024) and DEX (Supplementary Table S2; 2014–2024) constituted the canonical dataset used in this study. Each record includes the event date, venue, platform type, region, attack vector (mapped to the CEX 10-vector/DEX 18-vector taxonomies), loss amount (USD), and source citations. All figures and tables in §5.1.7.1–§5.1.7.6 are reproducible from these two supplementary tables by grouped aggregation over the vector, platform, year, and region fields. Tables 3, 5 define the taxonomies used to construct the summaries, and any total reported in the text (e.g., private key (CEX + DEX) = 78 incidents;

5.1.7 Incident results: taxonomy, trends, insights, and impact (2009–2024)

These analyses were enabled by a unified dataset of 220 incidents (the largest exchange-only compilation to date), which provides a longitudinal basis for trend analysis and cross-platform insights. Drawing on the curated 220-incident dataset (Supplementary Tables S1, S2) and the sources cited above, we analyzed, extracted, and categorized the exchange security incidents as follows:

1. Crimes on centralized exchanges (2009–2024): incident taxonomy and counts. See Section 5.1.7.1.

2. Crimes on decentralized exchanges (2009–2024): incident taxonomy and counts. See Section 5.1.7.2.

3. Annual losses on CEX and DEX platforms (2009–2024). See Section 5.1.7.3.

4. CEX–DEX incident comparison (and most-attacked platforms). See Section 5.1.7.4.

5. Repeated and common high-impact attacks on CEX and DEX. See Section 5.1.7.5.

6. Most common attack vector across all exchanges. See Section 5.1.7.6.

7. Incident trends over time. See Section 5.1.7.7.

8. Repeated attacks over time. See Section 5.1.8.

9. Financial impact and loss distribution. See Section 5.1.9.

5.1.7.1 Crimes on centralized exchanges (2009–2024)

As summarized in Table 3; Supplementary Table S1, we identified 80 major CEX incidents between 2009 and 2024. Our taxonomy comprises ten attack vectors, including hot wallet/private key compromise, compromised systems/servers, insider exploits, data leaks, and phishing via fake sites. Less frequent categories included protocol/implementation vulnerabilities and 2FA bypass. In aggregate, the quantified CEX losses totaled $4.191 billion; the top four vectors account for 62 of 80 incidents and approximately $1.764 billion (42.1%) of losses (Hong, 2019; Abhishta et al., 2019) (see Table 7 for aggregate losses and Table 4 for vector frequencies). Among the ten identified vectors, hacking/unauthorized access to hot wallets was the most prevalent (Panjwani, 2023; Bhusal, 2021), with 39 of the 80 incidents (nearly 50%). Internal mistakes have a low recurrence rate, whereas compromised servers and hot-wallet access remain persistent vulnerabilities. In 2022, the largest CEX loss was the FTX unauthorized transaction incident, exceeding $400M (Fu et al., 2022; Sigalos, 2023).

5.1.7.2 Crimes on decentralized exchanges (2009–2024)

As summarized in Table 5; Supplementary Table S2, we identified at least 140 DEX incidents spanning 18 distinct attack vectors between 2009 and 2024. Representative vectors include smart contract/protocol exploits (e.g., re-entrancy, logic bugs, oracle/manipulation errors), social engineering attacks, price-manipulation schemes (Blockchain, 2022), rug pulls, website/UI vulnerabilities, private-key compromise (admin/treasury/multisig), cross-chain and bridge weaknesses, double-spend attempts, malicious governance proposals, and flash-loan-enabled exploits.

Table 5. Summarized high impact dex exchange crimes from 2009–2024. Full List of incidence in Supplementary Table S1.

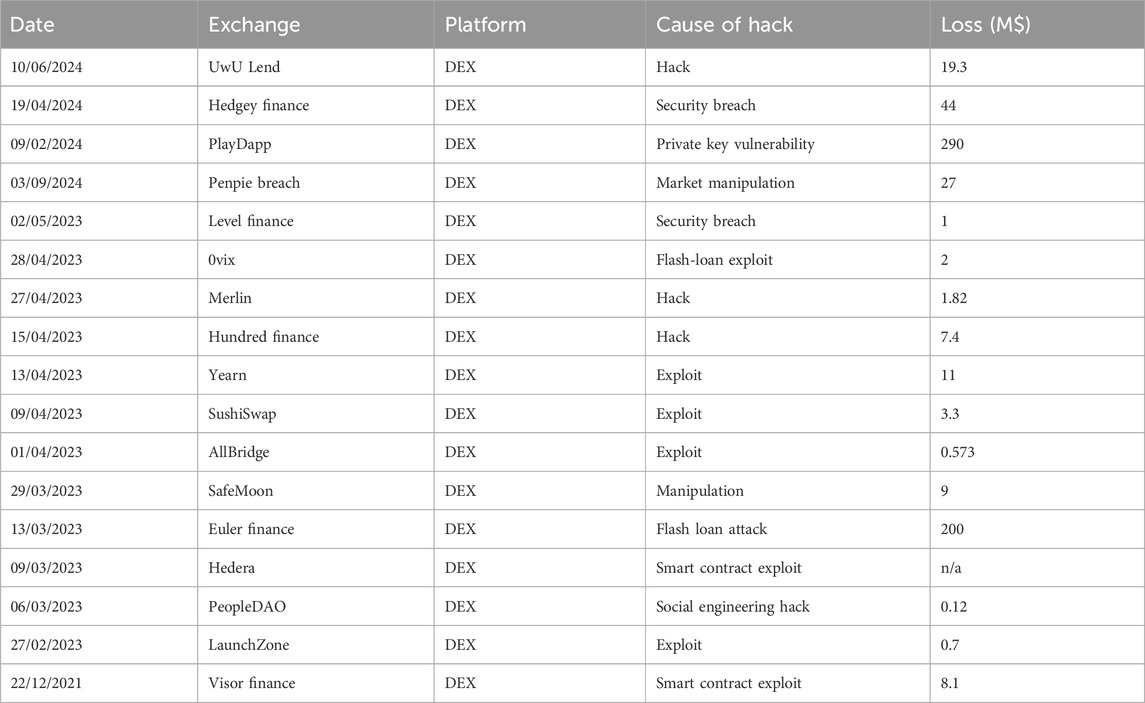

As shown in Table 6, system exploits (n = 56, 40.0%) and server/private key hacks (n = 39, 27.9%) are by far the most recurrent, together accounting for 95 of the 140 incidents (67.9%). These are followed by flash loan exploits (n = 12, 8.6%), price manipulation attacks (n = 6, 4.3%), and smart contract exploits (n = 7, 5.0%). Collectively, the top five vectors represented 120 of 140 attacks (85.7%). Recent DEX incidents have also produced large aggregate losses relative to many CEX events, thereby reflecting the scale and composability of on-chain protocols (Barbon, 2021). In aggregate, quantified DEX losses totaled $4.303 billion; the top five vectors account for approximately $3.755 billion (87.3%) of the losses (Hong, 2019; Abhishta et al., 2019); see Table 7.

Table 7. Repeated and high impact attacks vectors on CEX and DEX (2009–2024). Data extracted from Supplementary Tables S1, S2.

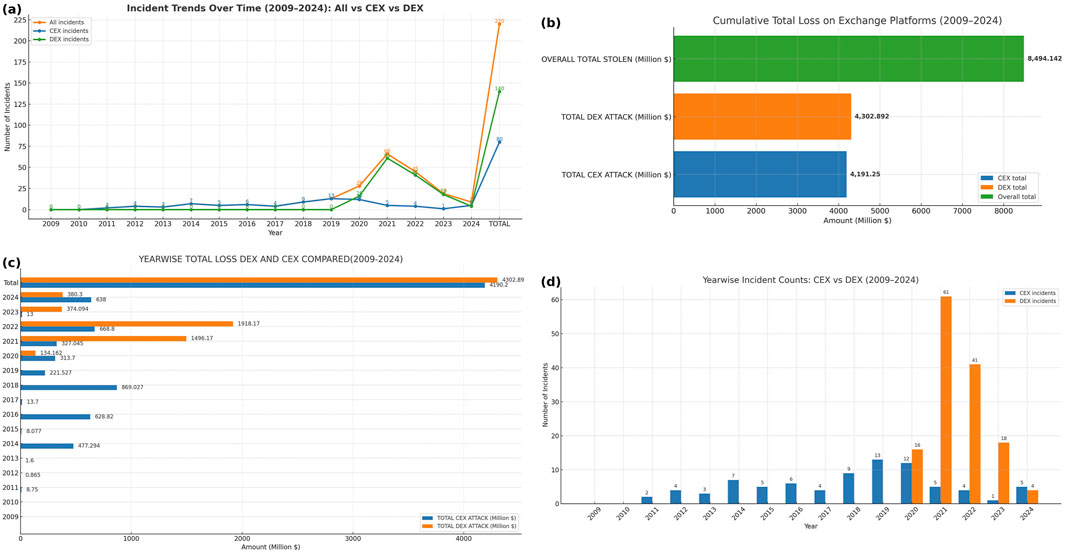

5.1.7.3 Annual losses on CEX and DEX platforms (2009–2024)

Centralized exchanges (CEX) preceded the later arrival of decentralized exchanges (DEX), and their early adoption made CEX the dominant trading model. In 2023, CEX platforms reported an estimated 80 million regular unique users, compared with a peak of 7.5 million unique DEX users in 2021 (Coinweb, 2023; Makridis et al., 2023; Pandya et al., 2019). The broad adoption of both models has attracted persistent criminal activity since 2009 (Collins, 2022; Higbee et al., 2018; Vidal-Tomás, 2021).

CEX yearly losses: Figure 5 illustrates the yearly losses on the CEX platforms grouped by our study’s attack-vector taxonomy. From 2009 to 2022, at least 80 reported incidents resulted in officially reported losses of over $4.191 billion. The largest annual losses occurred in 2018 ($869 million), followed by 2022 ($668.8 million), and 2016 ($628.8 million). From 2014 onward, CEX platforms experienced steady yearly attacks, while incident counts fell during 2019–2022 (13

DEX yearly losses. Figure 3 shows a breakdown of the total amount lost per year since DEX’s inception of DEX in 2014 owing to different crimes perpetrated against DEX platforms. In aggregate, the quantified losses on DEX totaled $4.303 billion, with 2022 recording the largest annual loss at over $1.918 billion. In recent years, attacks on DEX platforms have increased, reflecting multiple exploitable vulnerabilities in composable on-chain protocols (Badaw et al., 2020).

Figure 3. (a) Total CEX attack 2009_2024 (b) Total DEX 2009_2024 (c) CEX vs. DEX incidents (d) Attack vectors CEX vs. DEX.

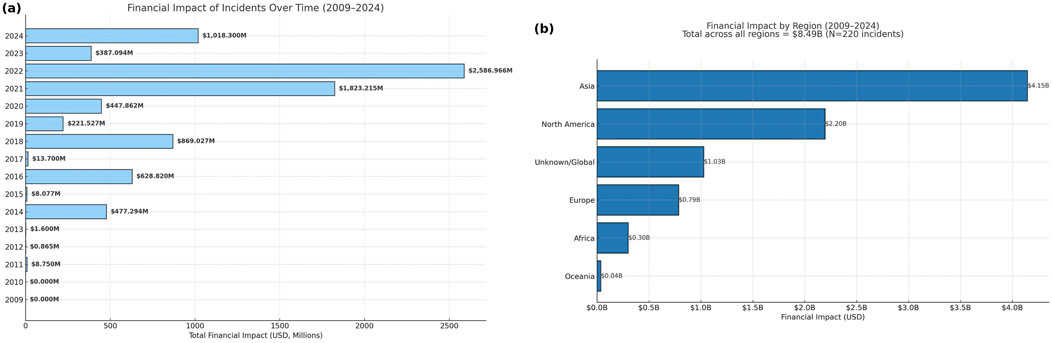

Peak year across platforms. As shown in Figure 6, the single largest combined annual loss occurred in 2022, totaling $2.587 billion across exchanges–$1.918 billion on DEX and $668.8 million on CEX. This peak substantially exceeds adjacent years (e.g., 2021 at

Overall total loss. Across 2009–2024, the cumulative losses across exchanges amounted to $8.494 billion ($4.191 B CEX; $4.303 B DEX), consistent with the “Total” bars in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Repeated high impact attacks: (a) repeated high impact attacks CEX (b) repeated high impact attacks DEX (c) high impact vectors CEX_DEX (d) summary_repeated attacks.

5.1.7.4 CEX–DEX incident comparison (and most-attacked platforms)

Figure 3C compares the incident frequencies of the CEX and DEX platforms. The data show that DEX venues experienced more cybersecurity incidents than CEX venues. Although DEXs provide decentralization, permissionless access, and user autonomy, these benefits come with reduced centralized oversight and weaker runtime controls, smart contract vulnerabilities, composability risks, and the absence of centralized monitoring, exposing DEXs to repeated high-impact attacks Chainalysis, 2022; Chainalysis 2023b; Chainalysis Team, 2024).

In contrast, CEXs, despite high-value breaches, tend to operate with stronger operational safeguards (custodial monitoring, layered access control, and compliance/audit programs) that lower the relative frequency of successful incidents (Chohan, 2022). However, both models remain materially exposed and require continuous hardening to ensure their reliability.

Most-attacked platforms. Figure 5 shows venue-level dispersion. In our dataset, the Uniswap DEX platform recorded the highest incidence of attacks, whereas the Binance CEX platform recorded the lowest among the major venues. This aligns with the mechanism-of-risk distinction above: DEX venues inherit smart contracts and composability risk (including human error and governance/upgrade pitfalls), whereas CEX venues benefit from centralized monitoring and coordinated incident responses.

5.1.7.5 Repeated and common high-impact attacks on CEX and DEX

As discussed in Section 5.1.5, we define repeated high-impact attacks as vectors that (i) recur more than four times (

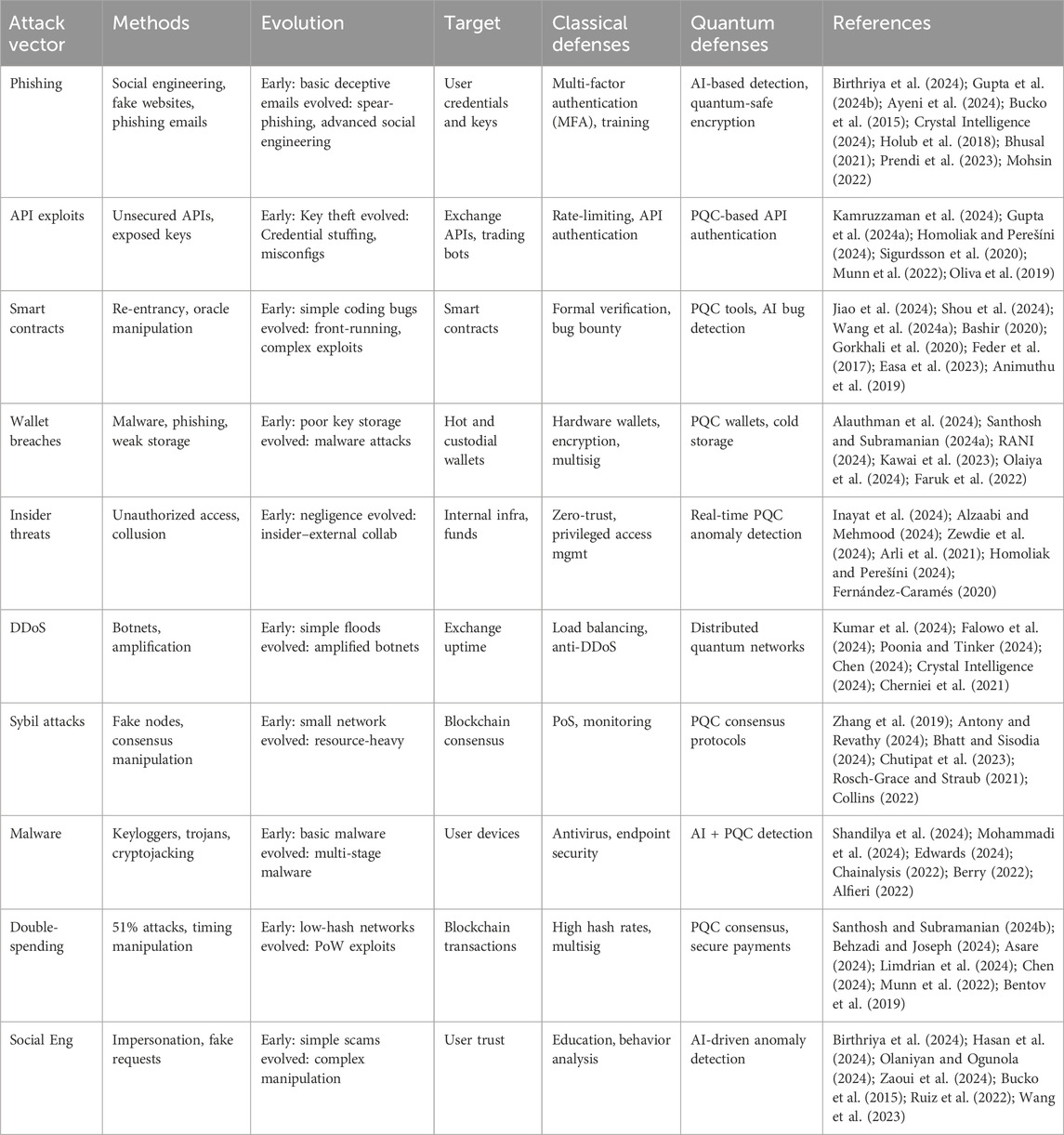

Table 8. Attack vectors, methodologies, evolution, primary targets, defensive mechanisms, and references.

CEX (repeated high-impact). Using the 10-vector taxonomy (Table 4), four vectors, as shown in Figure 4a exceeded the recurrence threshold and dominated the losses: Unauthorized Wallet Access (39), Server Exploit (10), Insider Exploit (7), and Data Leak/Breach (6). Together, they account for 62 of the 80 incidents (77.5%) and approximately $1.764 billion of $4.191 billion total CEX losses (42.1%). The dominant pattern involves access to hot wallets, which is often enabled by phishing or social engineering techniques (Agarwal et al., 2023).

DEX (repeated high-impact): Of the 18 attack types forming the 140 total DEX incidents (Table 6), five clear the recurrence threshold: System Exploit (56), Server/Private Keys Hacks (39), Flash-Loan Exploit (12), Smart Contract Exploit (7), and Price Manipulation Attack (6). These top five accounted for 120 of 140 incidents (85.7%) and $3.755 billion of $4.303 billion total DEX losses (87.3%) (see Figure 4b; Table 7.)

Combined view. Across both platforms, the repeated high-impact vectors sum to 182 of 220 incidents (82.7%) and $5.519 billion of $8.494 billion combined losses (65.0%), as shown in Figure 4d. This persistence indicates the structural weaknesses that adversaries repeatedly exploit.

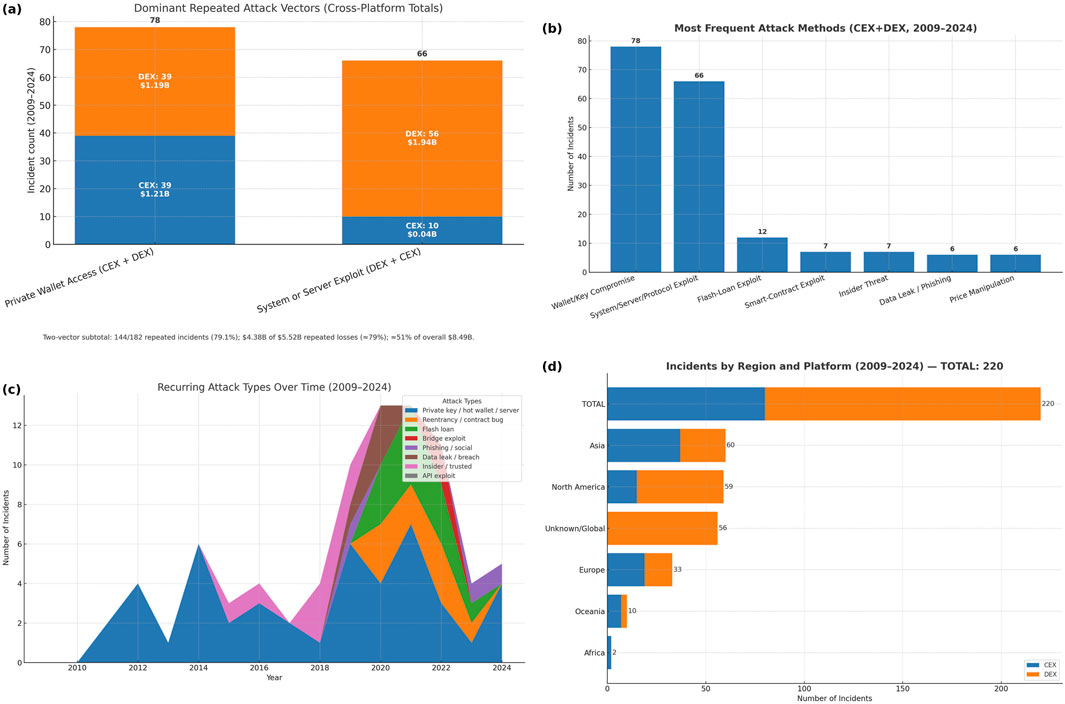

Most common attack vectors(CEX vs. DEX): Figures 3d, 6b From our findings, attackers commonly use five attack vectors including API exploits, insider threats, phishing, smart-contract exploits, and unauthorized wallet breaches across CEX and DEX. In CEX, repeated high-impact categories frequently manifest as wallet breaches (often delivered through phishing/API misuse) and insider/API problems. On DEX, smart contracts are exploited, and wallet breaches are dominant. These patterns align with the architectural risk surfaces of each platform (custody and server-side signing on CEX; contract logic, oracles, governance, and cross-chain bridges on DEX).

Figure 6. Attack vectors/types: (a) dominant attack vectors cex VS dex (b) most frequent attack methods (c) recurring attack types over time (d) Incidents by region and platform.

5.1.7.6 Most common attack vector across all exchanges

As shown in Figures 6a,b and Table 7), the dominant repeated vector across platforms is a wallet/key compromise (private key, hot wallet, or server access). This occurred 78 times (39 CEX; 39 DEX): 35.5% of all incidents (78/220) and 42.9% of repeated incidents (78/182), with combined losses of $2.394 B (43.4% of repeated-vector losses and 28.2% of the $8.494 B overall). The next most frequently repeated vectors are the system or server exploits of CEX(10) and DEX(56), that is, (66/182 repeated incidents with $1.979 B lost). Together, these two vectors account for 144/182 repeated incidents (79.1%) and $4.333 B of $5.518 B repeated losses (78.5%); that is, approximately 51% of the overall losses($8.494 B) across 220 incidents) as seen in Figure 6a.

The other repeated vectors (in Figure 4c). Beyond the two platform leaders, four additional repeated vectors show the material impact, listed in the same order as the chart: CEX Insider/Trusted (7 incidents; $0.23 B;

Two patterns stand out: (i) although less frequent than re-entrancy, DEX private-key compromises are the costliest per incident, and (ii) on CEX, data-leak breaches are rarer but unusually severe on a per-event basis.

The appeal of key and wallet compromise remains clear: attackers obtain signing authority via phishing, social engineering, credential theft, or by breaching the server-side signing infrastructure (Bartoletti et al., 2021; Crystal Blockchain, 2024b; Hedge with Crypto, 2024; Crystal Blockchain, 2024a). A high-profile case is the FTX unauthorized transaction incident in 2022 (approximately $600 M) Fu et al. (2022), after which the platform leadership was criminally prosecuted (Minto, 2022). These observations reinforce the need to harden custody architecture and server-side signing (e.g., HSM/MPC) on CEX while prioritizing secure smart contract development, auditing, and runtime monitoring on DEX.

5.1.7.7 Incidence trends over time

Figure 5a shows the incident counts per year (2009–2024) across all exchanges. Incidents started near zero in 2009–2010 and then rose modestly through 2014 (7) and 2018 (9), before a sharp increase in 2020 (28) and a peak in 2021 (66). The activity remained elevated in 2022 (45) and retreated in 2023 (19) and 2024 (9, year-to-date). Overall, the series showed episodic surges followed by partial pullbacks, consistent with cyclical exposure to a small set of recurrent vectors (see §5.1.7.5).

Figure 6d shows incidents by region (2009–2024). Asia and North America accounted for the largest share, with 60 (27.3%) and 59 (26.8%) incidents, respectively, followed by unknown/global 56 (25.5%), Europe 33 (15.0%), Oceania 10 (4.5%), and Africa 2 (0.9%). The concentrations in Asia and North America likely reflect the scale of their crypto ecosystems and attack surfaces (Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance, 2017b).

5.1.8 Repeated attacks over time

Figure 6c summarizes the recurrent attack patterns from 2009 to 2024 across five representative vectors: API Exploits, Insider Threats, Phishing, Smart Contract Exploits, and Wallet Breaches. Wallet Breaches are the most frequent and peak notably in 2012 and 2023. Smart contract exploits show consistent activity, with a high point in 2020. Phishing peaked between 2012 and 2020 and subsequently declined, whereas Insider Threats remained relatively stable with minor fluctuations. A modest increase was observed in the discovered API Exploits. Overall, these trends indicate that adversaries repeatedly return to a small set of structurally exposed vectors, which is consistent with the high-impact concentrations quantified in §5.1.7.5.

5.1.9 Financial impact of incidents

Figure 4c summarizes the total loss caused by repeated attack vectors (2009–2024). Using a harmonized taxonomy over the merged dataset, cumulative losses (USD billions) are as follows: Smart-contract exploits

Figure 7a shows the annual losses across exchanges. Loss peaks in 2022 at

Figure 7b details the regional loss distribution (2009–2024): Asia

6 Analysis of attacks techniques and patterns

Table 8 presents an in-depth analysis of numerous attack vectors, methodologies, evolutions, classical defence mechanisms, and widely used quantum defence mechanisms.

As the ecosystem surrounding cryptocurrencies grows in size and development, criminals seeking to identify vulnerabilities in these systems have a level of sophistication (Magizov et al., 2019). The tactics applied by these attackers have grown dynamically, from hacks, phishing, and social engineering to breaches. Quantum computing, which is slowly becoming more prevalent, will open up additional issues, particularly in cryptographic systems tasked with ensuring CExP security. To protect against both classical and quantum attacks, it is important to integrate quantum-safe cryptographic algorithms (Mosca et al., 2024), AI-based anomaly detection, and strong security authentication measures, such as multi-factor authentication and cold storage solutions (Badaw et al., 2020). By following these procedures, cryptocurrency exchanges can strengthen their defenses and mitigate the risks of current and future cyberattacks.

6.1 Impact of cybersecurity attacks on users, exchanges, and the industry

Cyberattacks on cryptocurrency exchanges have serious consequences for users, exchanges, and the broader ecosystem (Navarro, 2019; Alfieri, 2022). Their impacts include:

6.1.1 Impact on users

1. Financial Losses: Phishing, wallet breaches, and malware can lead to direct loss of funds and private keys (Purohit et al., 2023).

2. Loss of Trust: High-profile hacks erode user confidence, as in the Mt. Gox collapse (Bucko et al., 2015).

3. Personal Data Exposure: Breaches often leak sensitive information (emails, phone numbers, IDs), enabling identity theft and further attacks (Arli et al., 2021).

4. Psychological Impact: Anxiety and stress may drive users away from cryptocurrencies.

6.1.2 Impact on exchanges

1. Reputation Damage: Breaches harm credibility and deter new users (Marella et al., 2021).

2. Regulatory Scrutiny: Attacks trigger stricter oversight, often requiring stronger KYC/AML compliance (Mohsin, 2022; Mateen, 2023).

3. Financial Costs: Exchanges face compensation, restoration, and investigation expenses (Prendi et al., 2023).

4. Operational Downtime: Attacks often halt trading, withdrawals, and deposits, affecting liquidity and user activity.

6.1.3 Impact on the ecosystem

1. Reduced Adoption and Trust: Frequent attacks damage public confidence and slow adoption (Illia et al., 2023).

2. Higher Compliance Costs: Regulations like EU MiCA and FATF proposals increase operational costs (Cherniei et al., 2021).

3. Innovation Slowdown: Post-breach investigations divert resources from R&D.

4. Cybersecurity Investment: Exchanges invest heavily in bug bounties, AI anomaly detection, and quantum-safe cryptography (Sengupta et al., 2020).

6.1.4 Broader economic impacts

1. Market Volatility: Breaches intensify sell-offs and price drops (e.g., Mt. Gox 2014) (Li et al., 2022).

2. Migration to DEXs: Security concerns push users from CEXs to decentralized platforms, though DEXs face smart-contract risks (Krafft et al., 2018).

Having quantified the prevalent attack vectors, we next examine the security of the cryptographic primitives underpinning exchanges, both classical and quantum-resilient.

7 Classical cryptographic vulnerabilities and their defense in cryptocurrency exchanges

Classical cryptography defines conventional methods for data and communication security, in which established cryptographic algorithms are applied. Many of these methods are widely applied in the modern digital world to protect information, although they are vulnerable to the growing power of quantum computing (Szymanski, 2022). The following is an overview of classical cryptographic methods. The following is an overview of classical cryptography methods.

7.1 Classical cryptographic mechanisms

Traditional cryptographic measures in cryptocurrency exchanges include public-key encryption, hashing algorithms, multi-signature wallets, and digital signatures (Supplementary Table S5). All these security measures help protect users’ cash, ensure the integrity of transactions, and create a safe channel of communication between exchanges and users (Subramani et al., 2023). They also encounter different challenges, such as the requirement for careful key management to avoid losses and vulnerabilities from cryptographic attacks. In any case, both of the above solutions will certainly play a substantial role in further development and help maintain consistency and security of exchanges in the cryptocurrency ecosystem (Banoth and Regar, 2023).

7.2 Various defense measures on exchanges

Supplementary Table S6 explains the different measures of defence in exchanges.

1. Public-Key Encryption: It finds wide applications in securing transactions, wallets, and messages due to the fact that it offers confidentiality and authentication (Subramani et al., 2023).

2. Symmetric Encryption: The most used symmetric encryption algorithm is Advanced Encryption Standard, generally known as AES. Although AES is more resistant to quantum attacks compared to RSA, larger key sizes are preferred, such as AES-256, for better security (Banoth and Regar, 2023).

3. Homomorphic Encryption: A technique performs computation over encrypted data without revealing sensitive information.

4. Two-Factor Authentication: Used mostly with exchanges, 2FA will ask for two types of identity/password and something else-OTP, biometrical data-before allowing the user to log into their accounts. This approach provides increased security and is most common in protecting accounts from phishing and theft of credentials (Kiraz, 2016).

5. Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA): In supplementing the Two-Factor Authentication (2FA) with additional authentication levels, the MFA uses biometric or hardware tokens to finally reduce the possibility of an unwanted account access, in case of a password compromise (Tom et al., 2023).

6. Advanced Security Protocols Tokenization: Sensitive data, such as credit card numbers or user information, is replaced with random tokens. Tokens, even if intercepted, possess no intrinsic value, thus diminishing the possible consequences of a breach.

7. Hardware Security Modules, better known as HSMs, are physical devices involved in the process of creating, storing, and managing keys for cryptocurrency payments. They are a must in protecting exchange wallets and the cash that users have on their accounts due to the high level of security offered for cryptographic keys (Bentov et al., 2019; Rezaeighaleh and Zou, 2020).

8. Security protocols, such as Transport Layer Security (TLS) and Virtual Private Networks (VPNs), ensure that all data transferred between users and exchanges is encrypted, hence reducing the likelihood of data being intercepted while it is being transmitted.

Cryptographic systems are fundamental to ensuring the security of cryptocurrency exchange systems. However, attackers can exploit several weaknesses and vulnerabilities. Table 6 summarizes the key vulnerabilities and defense strategies.

8 Post-quantum cryptography and cryptocurrency exchanges

8.1 From classical defenses to quantum threats

Cryptocurrency exchanges currently rely on classical cryptographic mechanisms and layered defence strategies to secure their platforms and protect users from cyberattacks (Weichbroth et al., 2023). These include public key encryption, hashing algorithms, multi-signature wallets, and digital signatures that underpin authentication, transaction integrity, and custodial security. Although these defenses remain effective against current adversaries, they are increasingly strained by the growing sophistication of attacks.

Simultaneously, advances in quantum computing have led to a paradigm shift in cryptographic security. By applying the principles of quantum physics, quantum computers can perform computations beyond the capacity of classical machines (Gill et al., 2022; Rosch-Grace and Straub, 2021). Unlike binary bits, quantum bits (qubits) exist in superposition and enable massive parallelism, thereby allowing quantum systems to solve certain problems exponentially faster than classical systems (Gyongyosi and Imre, 2019; Preskill, 2018). This creates both opportunities and threats: algorithms such as Shor’s and Grover’s jeopardize the hardness assumptions underlying RSA and ECC, exposing exchange infrastructure to harvest-now and decrypt-later risks. Consequently, post-quantum cryptography (PQC) has emerged as a critical frontier for improving exchange resilience.

8.2 Post-quantum cryptography

Post-quantum Cryptography(PQC) denotes cryptographic algorithms designed to withstand the computational power of quantum computers (Fernández-Caramés, 2020; Chen, 2024). Quantum computing poses a potential threat to classic systems, including RSA, ECC, and DH, because their security depends on mathematical problems that any quantum computer can efficiently solve using methods such as Shor’s algorithm. Given the recent advances in quantum computing, the security of conventional cryptography public-key systems has become increasingly insecure. Therefore, quantum-resistant cryptography protocols are urgently required (Mosca et al., 2024; Yi, 2022; National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2024).

The urgency of PQC arises not only from theoretical concerns but also from real-world practices such as “harvest now, decrypt later” attacks, where adversaries store encrypted blockchain traffic today with the intent to decrypt it in the quantum future (Marchsreiter and Sepúlveda, 2023). In response, the NIST PQC standardization project selected lattice-based Kyber (ML-KEM) and Dilithium (ML-DSA) as primary standards (Chen, 2024; Cherkaoui et al., 2024; National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2024), while also advancing Falcon and SPHINCS + for specific use cases (Chen, 2024). This marks a critical turning point in the integration of post-quantum algorithms into the cryptocurrency ecosystem. Crypto-agility, the ability to swiftly migrate to stronger schemes, is now viewed as essential for blockchain protocols (Marchsreiter and Sepúlveda, 2023).

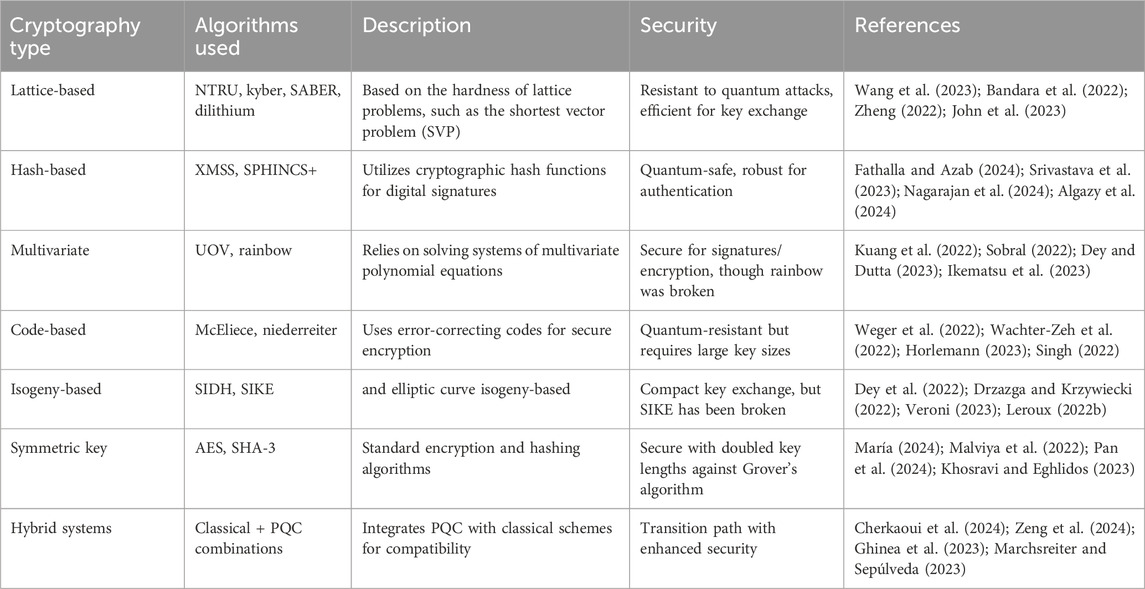

8.3 Types of post-quantum cryptographic algorithms

Table 9 summarizes the different types of post-quantum cryptographic(PQC) algorithms used.

1. Lattice-Based Cryptography: Lattice-based cryptography protects digital systems from classical and quantum attacks (Wang et al., 2023; Bandara et al., 2022). Security relies on the intractability of solving problems such as LWE and SVP, which remain impractical even for quantum computers (Zheng, 2022; John et al., 2023). Lattice-based schemes resist quantum algorithms, such as Shor’s algorithm, unlike RSA and ECC. Features include fully homomorphic encryption (FHE) for multiparty computation with the leading standards CRYSTALS-Kyber (key exchange) and CRYSTALS-Dilithium (digital signatures) (Chen, 2024; National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2024). Despite barriers such as large key sizes and computational overheads, lattice-based cryptography is a core component of quantum-safe infrastructure for exchanges, wallets, and blockchains.

2. Code-Based Cryptography: Proposed by McEliece in 1978, code-based cryptography relies on the difficulty of decoding linear error-correcting codes without a private key (Weger et al., 2022; Wachter-Zeh et al., 2022). Classic McEliece, BIKE, and HQC remain strong candidates, though their large public keys challenge lightweight implementation. Applications include wallet encryption, key management, and authentication (Singh, 2022). Research has aimed to reduce overhead and improve scalability (Horlemann, 2023; Gueron et al., 2022); Ren and Zhang, 2022), while keeping code-based schemes relevant for post-quantum security.

3. Multivariate Polynomial Cryptography: This approach makes it difficult to solve nonlinear multivariate equations in finite fields (Kuang et al., 2022; Sobral, 2022). It enables high-speed signing and efficient verification and is suitable for IoT and embedded devices (Dey and Dutta, 2023; Ikematsu et al., 2023). Examples include Rainbow, a former NIST finalist known for its compact signatures. The benefits include efficiency and low verification cost, whereas the challenges include key-size optimization and algebraic attack resistance (Kuang et al., 2022; Gong, 2024). In contrast, multivariate schemes support user authentication, integrity, and key management.

4. Hash-Based Cryptography: Hash-based schemes use one-way collision-resistant functions, avoiding algebraic structures vulnerable to quantum algorithms such as Shor’s algorithm (Fathalla and Azab, 2024; Srivastava et al., 2023; Nagarajan et al., 2024; Algazy et al., 2024). SPHINCS+ is a leading stateless hash-based signature scheme that provides strong guarantees without requiring state management. Exchanges use this for transaction signing, wallet authentication, and blockchain verification. Its limitations include large signatures and slower key generation; however, ongoing research has improved its efficiency, making hash-based cryptography a reliable option (Panthi and Bhuyan, 2023; Mamatha et al., 2024).

5. Isogeny-Based Cryptography: Isogeny-based schemes derive security from the difficulty of computing isogenies between elliptic curves, which are resistant to Shor’s algorithm (Dey et al., 2022; Drzazga and Krzywiecki, 2022). SIKE is a notable candidate in the NIST process, valued for its compact keys and low bandwidths (Veroni, 2023; Leroux, 2022b). Although vulnerabilities exist, they offer lightweight solutions for IoT and mobile wallets (Reijnders, 2023). With further research, isogeny-based systems can protect exchanges from quantum threats (Leroux, 2022a).

6. Quantum-Secure Symmetric Algorithms: Symmetric algorithms are less vulnerable to quantum attacks but face Grover’s algorithm, which halves the effective security. AES-256 and SHA-3 remain quantum-safe by relying on larger key lengths (María, 2024; Malviya et al., 2022; Pan et al., 2024; Khosravi and Eghlidos, 2023). They secure wallets, transactions, and blockchain communication and are efficient in IoT and mobile environments. Research has explored improving key management and resilience to ensure robustness against future attacks (Nosouhi et al., 2024; Feng et al., 2022).

7. Hybrid Cryptographic Systems: Hybrid systems combine classical schemes (RSA and ECC) with PQC algorithms (lattice, hash, or code-based) to provide both short- and long-term security (Ricci et al., 2024; Giron et al., 2023). They support wallet authentication, key exchange, and TLS protocols and blend ECC for real-time use with Kyber or Dilithium for quantum resistance. This transitional approach balances current deployment with future security demands (Cherkaoui et al., 2024; Zeng et al., 2024).

Currently, research is being conducted to make hybrid systems more efficient in terms of performance, scalability, and efficiency to ensure resistance against emerging threats while providing a smooth transition towards a totally post-quantum-secure setting.

8.4 Impact of quantum computing on classical cryptography

Most cryptocurrency exchange transactions rely on RSA and ECC (Rezaeighaleh and Zou, 2020; Islam et al., 2018); however, quantum computing poses a significant threat to these systems. Shor’s algorithm (Faruk et al., 2022; Kapoor and Thakur, 2022) can efficiently solve the difficult problems underlying these schemes, which modern classical computers cannot (Hussain, 2023; Sharma et al., 2022).

RSA’s security of RSA is based on the difficulty of factoring large numbers (Gangele, 2024); however, Shor’s algorithm can break it in polynomial time, rendering RSA insecure for future quantum adversaries (Vasavi and Latha, 2019; Moussa, 2020). Similarly, ECC, built on the hardness of the discrete logarithm problem, is equally vulnerable to Shor’s algorithm, thereby significantly compromising its security (Olaiya et al., 2024; Padhiar and Mori, 2022). Thus, widely deployed cryptography is obsolete in the quantum era, underscoring the urgency of quantum-resistant alternatives.

8.5 Emerging quantum threats

Quantum computing introduces threats that undermine the foundations of cryptography (See Supplementary Table S7). Mosca (2018); Mosca et al. (2024) warned that the timeline for “Q-day” may be shorter than expected, stressing the need for proactive migration through the inequality of data shelf-life and cryptographic transition. More recently, Reynolds (2025) reported that experts estimate a significant chance of Q-day before 2035, underscoring the urgency of adopting post-quantum defenses and preparing for harvest-now-decrypt-later (HN-DL) attacks.

1. Quantum Decryption: Shor’s algorithm enables efficient factoring and discrete logarithm solutions, undermining encryption protocols and exposing exchange transactions (Faruk et al., 2022).

2. Quantum-Enhanced Brute Force: Grover’s algorithm accelerates brute-force key searches, weakening symmetric encryption and reducing key lifetimes (Fernández-Caramés, 2020; Easa et al., 2023).

8.6 Challenges in the post-quantum ERA

Quantum computing challenges can be addressed in several ways.

1. Smart Contract Vulnerability: Contracts secured with classical cryptography become exposed to quantum-enabled attacks (Chen, 2024).

2. Migration Complexity: Integrating PQC into deployed systems requires extensive testing for compatibility (Wang et al., 2023).

3. Scalability: Many PQC algorithms demand more resources, reducing transaction throughput (Dharminder et al., 2023).

4. Lack of Standardization: Consensus on quantum-safe algorithms remains pending, complicating adoption (Yi, 2022).

5. Time Sensitivity: Rapid migration is needed to pre-empt harvest-now, decrypt-later attacks.

Backward compatibility further complicates adoption. Many exchanges rely on ECC for wallets and smart contracts (Ghinea et al., 2023). Migration often requires hybrid approaches (e.g., ECC with Kyber or Dilithium), which increase the payload size and computation, stressing mobile and IoT devices (Ghinea et al., 2023; Cherkaoui et al., 2024; National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2024; Marchsreiter and Sepúlveda, 2023).

8.7 Post-quantum cryptography for cryptocurrency exchanges

Given the reliance on public key cryptography for signatures and secure communication, exchanges must transition to PQC (Chen, 2024; Marchsreiter and Sepúlveda, 2023). Therefore, phased adoption is recommended.

1. Quantum-Resistant Signatures: Schemes such as XMSS and LMS protect transactions in a quantum era (National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2024).

2. Quantum-Secure Key Exchange: Kyber can replace ECDH for secure channel establishment (Cherkaoui et al., 2024).

3. Lattice-Based Encryption: Ensures sensitive data remain safe even if classical schemes are broken (John et al., 2023).

8.8 Threat timeline and policy implications

Although the exact timeline for scalable quantum computers remains uncertain, experts have estimated practical threats within 10–15 years (Chen, 2024). Harvest-now and decrypt-later risks require immediate preparation (Marchsreiter and Sepúlveda, 2023). Regulators such as NIST, ETSI, and NSA encourage proactive PQC migration (Chen, 2024; National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2024). Exchanges must implement crypto-agility and begin testing NIST-approved schemes to mitigate systemic risks (Marchsreiter and Sepúlveda, 2023).

9 Discussion

9.1 Research gaps

This review highlights that despite substantial progress in cryptography and blockchain research, important gaps remain in securing cryptocurrency exchanges against classical and quantum adversaries. By curating the first PRISMA-ScR-guided dataset of 220 exchange-only breaches drawn from academic studies, industry reports, and technical disclosures, this study provides a structured evidence base that was absent in previous studies. Our synthesis demonstrates that vulnerabilities are not isolated events but recur systematically; however, existing scholarship has not sufficiently addressed this. These observations build directly on the dataset of 220 validated exchange-only incidents summarized in Section 5, which revealed that vulnerabilities frequently recurred across platforms and years, confirming the systemic nature of the risks discussed here.

First, relatively few studies have examined how the authentication infrastructure of exchanges is exposed to both classical and quantum threats (Chainalysis, 2022; Chainalysis 2023b; IMARC Group, 2023; Oosthoek, 2021; Faruk et al., 2022; Vasavi and Latha, 2019; Olaiya et al., 2024; Sarkis-Onofre et al., 2021). Second, quantum-safe cryptographic algorithms are rarely tailored to the operational realities of exchanges, where latency, throughput, and interoperability are critical (Faruk et al., 2022; Fernández-Caramés, 2020; Easa et al., 2023). Third, multimodal or hybrid post-quantum authentication frameworks are virtually absent in the literature, even though exchanges remain high-value targets (Olaiya et al., 2024; Chen, 2024; Saha et al., 2023; Dharminder et al., 2023; Yi, 2022). Beyond algorithms, practical deployment is rarely simulated in live or large-scale exchange environments (Bucko et al., 2015; De Saint Guilhem et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2024; Chen, 2024; Saha et al., 2023; Yi, 2022; Panthi and Bhuyan, 2023; Mamatha et al., 2024). Moreover, economic assessments of migration remain underdeveloped, and few studies have quantified the cost-benefit trade-offs of PQC adoption across heterogeneous blockchain ecosystems (Saha et al., 2023; Yi, 2022). Scalability also persists as a problem, with most post-quantum crypto systems untested under high-throughput real-world conditions (Rezaeighaleh and Zou, 2020; Prabakaran and Ramachandran, 2022; Nagarajan et al., 2024; Cherkaoui et al., 2024). Finally, the integration pathways for legacy systems are not clearly articulated, leaving exchange operators without transition roadmaps (John et al., 2023; Dey et al., 2022; Giron et al., 2023). Together, these gaps indicate that both technical design and sociotechnical adoption strategies require further research attention.

9.2 Repeated and dominant attack vectors

Hot wallet compromises are disproportionately prevalent because of the inherent trade-off between accessibility and security issues. Exchanges must maintain hot wallets online to ensure continuous liquidity and rapid settlement; however, this design exposes the private keys to adversaries. Even with safeguards such as multi-signature schemes or withdrawal limits, the online nature of hot wallets increases their susceptibility to theft (Crystal Blockchain, 2024b); Erinle et al., 2023; Sigurdsson et al., 2020). As a result, attackers repeatedly exploit these systemic vulnerabilities, making hot wallet breaches a dominant incident vector. This interpretation aligns with the results showing that wallet and key-management breaches accounted for 78 of the 220 incidents (35%) and approximately $2.39 billion in cumulative losses, confirming their disproportionate impact.

For decentralized exchanges (DEXs), the higher frequency of incidents (140 for DEX vs. 80 for CEXs) yet comparable aggregate losses can be explained by the concentration of attacks on protocols with significant Total Value Locked (TVL). When numerous small-scale exploits occur, adversaries disproportionately target high-value liquidity pools and automated market makers. A single breach in a system protocol with billions of TVL can generate losses equivalent to those in custodial CEX incidents (DefiLlama, 2025a; Chainalysis, 2023b; Nabilou, 2020). This reflects a systemic difference: CEX incidents are commonly tied to custodial infrastructure and authentication, whereas DEX breaches stem from protocol-level weaknesses in smart contracts and governance. As detailed in Table 7; Figure 4, DEX platforms accounted for 140 total incidents, of which 120 (85.7%) were repeated high-impact attacks. Despite the decentralized architecture, these attacks concentrated on high-TVL (Total Value Locked) protocols platforms holding large volumes of user funds, resulting in aggregate losses comparable to centralized exchanges.

9.3 Security of exchanges in the quantum era

Approximately 12% of the incidents in the dataset involved cryptographic or key-management weaknesses, providing the empirical foundation for assessing how quantum algorithms could amplify these vulnerabilities. Our analysis of the incident vectors underscores the need for exchanges to prioritize quantum resilience. Wallet and private key compromises and DEX protocol exploitation dominate historical breaches. In the quantum era, these vectors have become even more dangerous: Shor’s algorithm threatens RSA and ECC, whereas Grover’s algorithm reduces the effective strength of symmetric primitives. As Mosca (2018) warned, the timeline for “Q-day” may be shorter than expected, requiring proactive migration rather than reactive defence.

Our findings have led to the emergence of practical strategies. Continuous monitoring of quantum algorithmic progress must be institutionalized by the exchange operators. Gradual migration to lattice-based encryption (e.g., Kyber) and hash-based signatures (e.g., XMSS and SPHINCS+) should occur through hybrid deployments that preserve backward compatibility with existing RSA/ECC infrastructure. Exchanges must also upgrade Hardware Security Modules (HSMs), authentication servers, and wallet architectures to support PQC natively. Regular quantum-aware risk assessments coupled with third-party audits are essential for validating compliance with emerging standards. Importantly, quantum security cannot be achieved in isolation; collaboration with cybersecurity firms and standardization bodies, such as the NIST, will be vital to ensure interoperability and coordinated adoption.

In this study, post-quantum readiness was assessed using a structured set of indicators derived from both technical and organizational dimensions. At the technical level, we analyzed the proportion of incidents linked to cryptographic or key-management weaknesses (12% of the dataset) (Suga et al., 2020; Oosthoek et al., 2020; Monrat et al., 2019) and evaluated the extent to which exchanges had adopted or tested quantum-safe primitives such as lattice-, hash-, and isogeny-based schemes (Leroux, 2022b; Reijnders, 2023; Ricci et al., 2024; Giron et al., 2023; Singamaneni and Muhammad, 2024). At the organizational level, readiness was gauged through the presence of formal migration planning, use of hardware security modules (HSMs) with PQC compatibility, and evidence of alignment with emerging frameworks such as the NIST PQC standardization roadmap and ETSI QSC guidelines (National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2024; Nosouhi et al., 2024; Mosca, 2018). These indicators collectively formed the basis for evaluating institutional preparedness and quantum-era migration maturity within the exchange ecosystem.

9.4 Implications for operators and regulators

For exchange operators, the dataset shows that 67.9% of recorded incidents stem from two repeated vectors: key compromise and system exploitation. This concentration of risk reflects underlying structural weaknesses in exchange architecture–particularly hot wallet custodianship, key management, and protocol-level controls–that continue to enable repeated exploitation. This finding corresponds to the quantitative pattern in which two repeated vectors–wallet/key compromise and protocol exploitation–jointly accounted for 65% of total recorded losses, highlighting where mitigation should concentrate. Therefore, operators must adopt hybrid PQC schemes in the near term while preparing to transition fully once the standards stabilize. Investments in training, simulation of quantum attacks, and joint R&D with academic partners will accelerate preparedness.

These longitudinal findings, drawn from the 2009–2024 dataset, emphasize that regulatory interventions must address historically recurrent weaknesses rather than isolated breaches. For regulators, this dataset offers a rare longitudinal map of systemic vulnerability. This evidence highlights the urgency of regulatory harmonization, echoing trends seen in frameworks such as the EU Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) regulation and MAS oversight in Singapore. Regulators should define explicit PQC adoption timelines, mandate quantum security audits, and develop incident response protocols that are adapted for quantum-enabled breaches. Without coordinated oversight, fragmented PQC adoption risks leaving exchanges, and, by extension, retail investors are exposed to asymmetric quantum advantages, which highlights the urgency of harmonized oversight, as emphasized in efforts to build standards from past exchange failures (Suga et al., 2020; Johnson, 2020).

9.5 Recommendations for exchange security