- 1School of Science and Environmental Futures Research Centre, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW, Australia

- 2NSW Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, Marine Ecosystem Unit, Fisheries Research, Huskisson, NSW, Australia

- 3Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW), Waters, Wetlands and Coastal Science, New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Anchoring impacts to marine environments from large, ocean-going ships is increasingly recognized as a global threat to marine biota. To date, no replicated assessment examining anchor disturbance to fish assemblages exists at the scale of ocean-going vessels. Here we aim to fill this important knowledge gap, using the Port Kembla Anchorage in SE Australia as a case study. We predicted that demersal fish on temperate rocky reefs (>30m) exposed to anchoring activities would differ significantly to those that were ‘anchor-free’. Using Baited Remote Underwater Video (BRUV) we assessed species and functional groups using a full-subsets generalized additive mixed modelling approach, including fine-scale reef variables as covariates to account for natural spatial variability and to improve estimates. Reefs exposed to anchoring (ie. disturbed) was the most important predictor for the total abundance of fish, with twice as many individuals when compared to undisturbed reefs (anchor-free). Abundance measures were largely driven by the shoaling zooplanktivore; Atypichthys strigatus, with near four-fold increases of this trophic group on anchored reefs. In contrast, the abundance of other taxa including, Meuschenia freycineti and demersal elasmobranchs combined decreased two to three-fold on disturbed reefs. These results indicate anchoring activities can have ecosystem-wide impacts to fish assemblages underscoring the importance of better managing anchoring near ports globally.

1 Introduction

Maritime transport is the backbone of modern trade and globalized economies with >80% of goods transported by large container ships and bulk carriers, summing to more than 120,000 port visits per annum (UNCTAD [United Nations Conference on Trade and Development], 2024). With this heavy reliance on shipping, comes increasing potential for impacts to marine environments and their associated biota. Numerous stressors associated with shipping have been well documented, although the focus has largely been on shipping as a vector for invasive species as well as a source of chemical and underwater noise pollution (Jägerbrand et al., 2019; Qi et al., 2024). However, evidence is building on the adverse impacts of anchor and chain scour from ships as an important source of disturbance to marine systems (Davis et al., 2016; Broad et al., 2020). Spatial analyses using ship tracking data indicate that this disturbance can extend far beyond designated anchorages near ports (Steele et al., 2017) and disturbances from this routine operation can occur over very large spatial scales (Davis et al., 2022; Watson et al., 2022; Broad et al., 2023), contributing to more than 48% of all seabed disturbance in some coastal areas (Watson et al., 2020).

Rocky reefs and the biota associated with them, constitute significant reservoirs of biodiversity vital for temperate marine systems (Bennett et al., 2016). They offer abundant food resources, as well as habitat refugia attractive to economically important fish assemblages (Tuya et al., 2009; Gaylard et al., 2020). At mesophotic depths (>30m), temperate reefs are primarily dominated by sponge fauna, ahermatypic cnidarians (non-reef builders) and bryozoans (lace corals) which have collectively been referred to as ‘Marine Animal Forests’ (Rossi et al., 2017). Researchers have previously suggested that these offshore, mesophotic reefs are largely exempt from the common stressors actively degrading shallow nearshore reefs, serving as refugia and sustaining shallow reef fish communities (Bongaerts et al., 2010; Assis et al., 2016). However, assessments of many mesophotic systems remain in their infancy, as they are logistically difficult and expensive to investigate. Therefore, in many temperate areas, the condition of these types of reefs has yet to be determined. Recent research has uncovered chronic degradation of mesophotic reefs at some locations from marine industries (Bennett et al., 2016; Broad et al., 2023), which are unlikely to support the requirements of diverse fish assemblages and may compromise their functional traits, limiting their range (McCauley et al., 2015).

Natural disturbances, often associated with weather, are commonplace in many shallow marine systems and can shape communities, as well as the species within them (Pickett and White, 1985). In deeper, relatively more stable waters, however, disturbances from offshore marine industries, such as demersal fishing, mining and shipping have, in many cases, transformed marine ecosystems over large spatial scales (Ibon, 2013; Broad et al., 2020; Gaylard et al., 2020). Mechanical operations and disturbances from marine industries can simplify complex environments, reducing the tri-dimensional complexity of coral or rocky reefs and the ecosystem engineers they house (Alvarez-Filip et al., 2009; Broad et al., 2023). Therefore, chronic damage to reefal habitat or removal of biogenic structures by anchor scour would be expected to have flow-on effects for associated motile fauna such as fishes (Forrester et al., 2015; Roberts et al., 2016; Flynn and Forrester, 2019).

Research examining anchor disturbance to date has largely focused on impacts from recreational boating which consistently reveal decreases in the biogenic structure and habitat complexity which inevitably impact demersal fish assemblages (Lanham et al., 2018; Flynn and Forrester, 2019; Broad et al., 2020). Anchor damage from recreational vessels on tropical coral reefs have resulted in wide-spread changes to the structure of reef fish assemblages, with reductions in species richness, as well as alterations in the distribution and abundance of several trophic guilds (Flynn and Forrester, 2019). In temperate regions, impacts of anchoring activities on fish assemblages are contradictory; seagrass loss can negatively affect some guilds (Kiggins et al., 2018), while recreational boat mooring research examining soft sediment environments reported impacts to fish assemblages as subtle and only detectable at the smallest of scales (m’s) (Lanham et al., 2018). A key point is the marked discrepancy in the scale of disturbance generated by small recreational boats versus large ocean-going commercial vessels, with the later representing a significant gap in our knowledge (Deter et al., 2017; Broad et al., 2020; Watson et al., 2020, 2022).

Despite clear evidence that anchor scour over reef from ocean-going vessels damages and removes sessile biota such as sponges (Broad et al., 2023), the effects on associated fauna, such as fishes, have not yet been assessed. Here, we seek to fill this important knowledge gap and test the hypothesis that, fish on temperate mesophotic rocky reefs frequently ‘anchored’ on will differ significantly relative to ‘anchor-free’ reefs and examine effects across species, taxonomic groups and trophic guilds. We sought to reduce the impacts of potential confounding factors by incorporating localized seascape variables (Rees et al., 2018a, b) including reef structure, depth and the proportion of reefal habitat at sample locations. This study extends the knowledge of demersal reef fish distribution and abundance on temperate mesophotic reefs generally, though notably is the first quantitative assessment of anchor scour impacts from maritime trading ships (>100m in length) to any demersal fish population. Importantly, the outcomes of this work will directly inform future decision-making for the management of shipping in marine estates locally (BMT WBM, 2017) and across the globe.

2 Methods

2.1 Study region and sampling design

This study was done along a ~25km stretch of coastline in south-eastern, Australia (Figure 1). At the time of sampling, ships anchored in an unregulated anchor roadstead in this region, over an area spanning ~220km2 (Davis et al., 2022) in water depths ranging from 35-60m. The seabed in this depth range is characterized by extensive, predominantly low-profile rocky reef, including channels containing mixed reef with boulders, gravel and sand (Linklater et al., 2019).

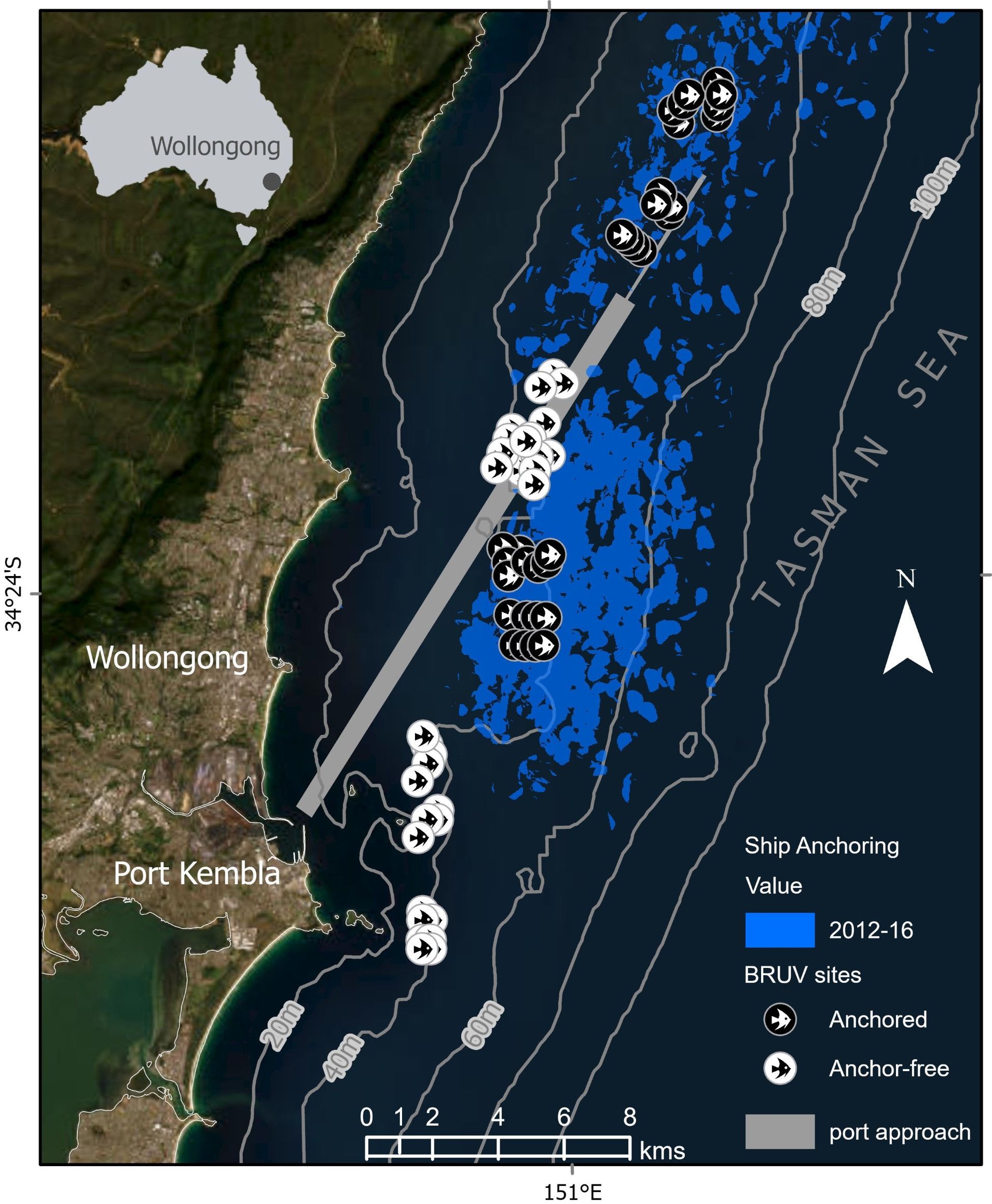

Figure 1. Map showing the study sites offshore from Wollongong, Australia. Baited Remote Underwater Video (BRUV) sites on reefs anchored on (black circles) and those that were anchor-free (white circles). The anchor roadstead, depicted in blue, reflects anchoring events between Sept 2012 and June 2015. Note the shipping approach to the Port Kembla Harbor is depicted as a linear grey feature. Depth contours along the continental shelf are depicted as thin grey lines.

To delineate the anchor-roadstead and identify anchor-free reference areas we used a similar approach to Broad et al. (2023). We identified vessels at anchor using positional information (Automated Identification Systems (AIS) between September 2012 to June 2016 – just prior to fish sampling. This spatial information was then overlaid on high resolution maps with 5m gridded bathymetry derived from multibeam echosounder (MBES) surveys (www.aodn.org.au) allowing us to identify ‘anchored’ and appropriate ‘anchor-free’ reference locations on rocky reefs within a depth range ~35-50m. Conservative estimates based on the AIS data confirmed that reference areas had not been anchored upon for > 4 years.

Baited Remote Underwater Video (BRUV) was used to test the hypothesis that fish assemblages would differ across reefs ‘anchored’ and ‘anchor-free’ areas. BRUV has been used routinely for sampling fish assemblages as it is non-destructive and provides useful measures of species richness as well as relative abundance estimates of diver-shy and economically important fish assemblages (Watson et al., 2005; Kelaher et al., 2014; Rees et al., 2018a, b; Rees et al., 2021). As bait attracts fish, BRUVs also reduce the problem of zero-inflated datasets (Schramm et al., 2020). BRUV was particularly suitable in this study as units can be deployed in water depths exceeding 30m and considered too deep for diver-based assessments, particularly over large spatial scales (km’s).

The BRUV system used in this study consisted of a single GoPro HERO3+ camera (www.gopro.com) mounted within a waterproof housing camera housing. BRUV’s were deployed across four sites: two sites of ‘anchored’ reef and two sites that were ‘anchor-free’. Anchored treatments were interspersed in space and time and within each site we deployed 16 BRUV replicates (Figure 1) for a total of 64 BRUV deployments in the study. Each BRUV was deployed for 35 minutes to allow for settlement time and to achieve a 30-minute video sample. Previous research has demonstrated that 30 minute is an appropriate set time to provide a representative sample of temperate rocky reef fish assemblages (Harasti et al., 2015). Each sample was separated by a minimum distance of 200 m, consistent with other assessments using this method in the region (Kelaher et al., 2014; Rees et al., 2018a; Knott et al., 2021). Sampling was interspersed over several days during the late Austral winter and early spring (July to September, 2016) with all collections done in daylight hours (0900 to 1600) to alleviate potential effects of crepuscular feeding behaviors (Wraith et al., 2013). BRUV deployments used ~500 grams of thawed and crushed pilchards (Sardinops sagax) which has been determined as the optimal bait across a range of feeding guilds (including herbivores) (Harvey et al., 2007; Wraith et al., 2013) and was replenished for each subsequent deployment.

2.2 Analysis of video footage and guild identification

Videos were analyzed in the laboratory by a single experienced observer (AB) using the BRUV analysis software EventMeasure (http://www.seagis.com.au). All fish were recorded if they swam within 2 meters of the bait bag, providing a standardized (FOV) ~9 m3 (Malcolm et al., 2007). Species richness, total Max N, and Max N of each fish species were recorded for each video sample. Species richness (SR) is the sum of all the species recorded for each video sample and Max N is an estimate of the total abundance observed in one frame of a given species. Fish that displayed sexual dimorphism (e.g. Labrids) or protruding sexual organs (e.g. claspers in male elasmobranchs) provided improved estimates of these metrics and we adjusted MaxN counts of those species (see Supplementary Table 1). The total relative abundance for each sample, Total MaxN, was determined by summing the MaxN for all species over the 30 min sample. After video analysis, fish were classified into taxonomic groups (subclass/family) and trophic guilds to test for differences (for a full list with definitions see Supplementary Tables 1, 2). The later was based on their diet, previous research (Wraith et al., 2013; Swadling et al., 2019) or review of other supporting literature (Bell et al., 1978; Choat and Ayling, 1987; Bulman et al., 2001). In instances where no trophic information was available for a particular species, a similar, closely related species was used for inference. Species were grouped into one of three trophic groups; (i) herbivores; (ii) zooplanktivores and (iii) generalist carnivores.

2.3 Benthic classification

Fine-scale habitat features for each BRUV replicate were analyzed using TransectMeasure (www.seagis.com.au; see Supplementary Tables 3, 4) following the method described in McLean et al. (2016). A 5 x 4 grid was overlaid on a high definition still frame from each BRUV deployment delineating cells to be scored (n=20). For each of the 20 cells, the dominant habitat type and vertical relief was scored following the CATAMI classification scheme (Althaus et al., 2015). The main habitat classifications were defined as either; unconsolidated sediments (sand or gravel), consolidated rock, macroalgae (any >5cm), sponges, ascidians and open water. For each cell containing benthos, an estimate of vertical relief was scored between 0 – 5 (Wilson et al., 2007). The BRUV Field of View (FoV) was also scored as ‘open water’, ‘video facing-down’, ‘facing-up’ or ‘limited FoV’ e.g. obstruction by a rocky outcrop. Data were exported from TransectMeasure using R scripts available from Langlois (2017). Cells of open water were removed before calculating the percentage cover of habitat and the mean vertical relief for each deployment. Depth (m) was recorded for each BRUV deployment in the field using the research vessel’s sounder.

2.4 Habitat mapping

Multibeam surveys (MBES) in the vicinity of the Port Kembla roadstead were completed by NSW state government during the period Oct 2014 – May 2017 and made available via the Australian Oceanographic Data Network (AODN: https://www.aodn.org,au). Survey methods are detailed in Linklater et al. (2019) utilizing both a Geoswath 125khz (Teledyne GeoAcoustics, U.K) and an R2Sonic 2022 (R2Sonic, USA) with a POS MV vessel reference system for motion correction. Bathymetric data were issued as depth-weighted averages of cleaned (Cube-modelled) multibeam soundings binned at 5m resolution and reported relative to Australian Height Datum. Data were imported to ArcMap (ESRI, USA) and additional layers of hillshade, slope and ruggedness calculated using tools including Benthic Terrain Modeller. These layers were then used to inform the selection of BRUV deployment sites over reef across the northern impact, southern impact and southern control locations. Bathymetric data for the section of the seabed in the northern control location were unavailable at the time of fieldwork planning. In this instance, a random location for each BRUV drop was nominated and then the presence of reef confirmed using the vessel’s onboard echosounder when on site. To calculate measures of reef structural complexity, the standard deviation of bathymetry values within 25 m, 50 m and 100 m radius buffers were calculated from the MBES data for each BRUV deployment.

2.5 Data analysis

The influence of anchoring and fine-scale habitat variables on the fish assemblage was analyzed using Generalized Additive Mixed Models (GAMMs; Hastie and Tibshirani, 1986; Hastie, 1990). GAMMs were chosen over Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMMs) to allow for non-linear relationships between the response and explanatory variables. A full-subsets modelling approach was used to determine which of the available explanatory variables were most important in influencing the fish assemblage (Fisher et al., 2018). Using this approach a complete model set was constructed and the selection of models was based on Akaike Information Criterion optimized for small sample sizes (AICc). Models within two delta AICc units (ΔAICc < 2) of the model with the lowest AICc were selected (Burnham and Anderson, 2002). If there were multiple models within two delta AICc unit, we selected the most parsimonious model(s) with the fewest explanatory variables. The relative importance of each explanatory variable was calculated by summing the AICc weight values for all models. Variables with higher summed values represent increased importance of that explanatory variable (Burnham and Anderson, 2002). To avoid issues of collinearity, candidate models could only contain explanatory variables with Pearson correlation coefficients < 0.28 (Graham, 2003). The maximum number of explanatory variables for each candidate model was limited to three to reduce over-fitting and ‘site’ was included as a random effect in all models to account for overdispersion and correlation in the data (Harrison, 2014). In all candidate models, explanatory variables were fitted with smoothing splines, with the ‘k’ argument limited to four.

Models were run on species richness, total relative abundance (total MaxN), abundance of trophic guilds, taxonomic groups and the abundance or presence/absence of common species present in >30% of samples (~16 spp.). Untransformed measures of the fish assemblage were used as response variables. The models for species richness were fitted with a Gaussian error distribution while models for total abundance included a negative binomial error distribution. GAMMs for the abundance of Ophthalmolepis lineolata and Bodianus unimaculatus were fitted with a Poisson error distribution. A Tweedie error distribution was fitted to all other relative abundance models due to the large number of zeroes (Tweedie, 1984). Taxa observed in low relative abundances were transformed to presence/absence and modelled using a binomial error distribution; this method has been shown to be an effective method for extracting ecologically meaningful data in rare or cryptic species (Joseph et al., 2006). Prior to analysis, the distribution of explanatory variables was plotted. Explanatory variables displaying a skewed distribution were transformed to ensure an even spread of values across the observed range. All data manipulation, analyses and plots were developed using the R language for statistical computing with the ‘dplyr’ (Wickham et al., 2020), ‘ggplot2’ (Wickham, 2016), ‘mgcv’ (Wood, 2011) and ‘FSSgam’ (Fisher et al., 2018) packages.

3 Results

3.1 Overall assessment

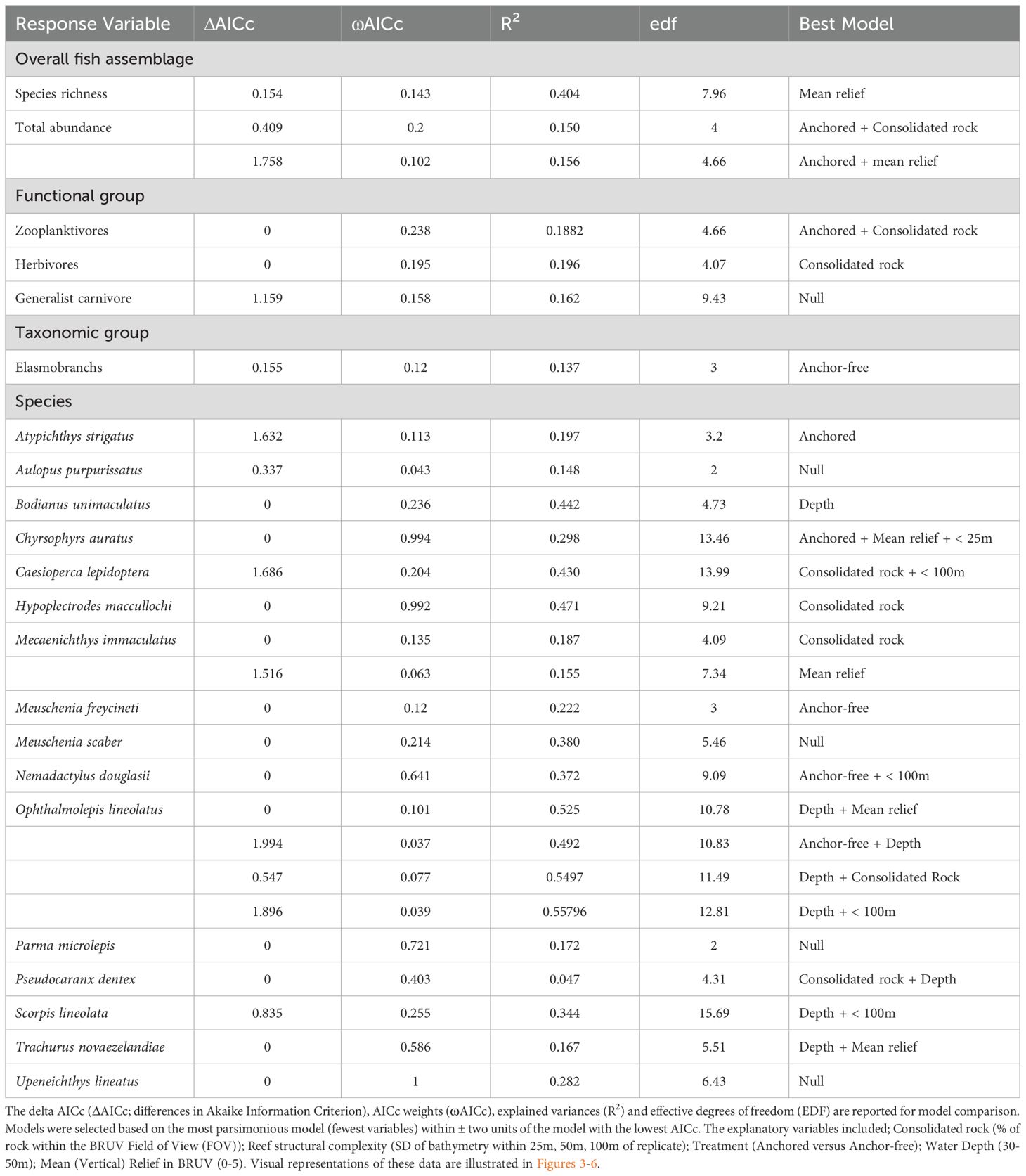

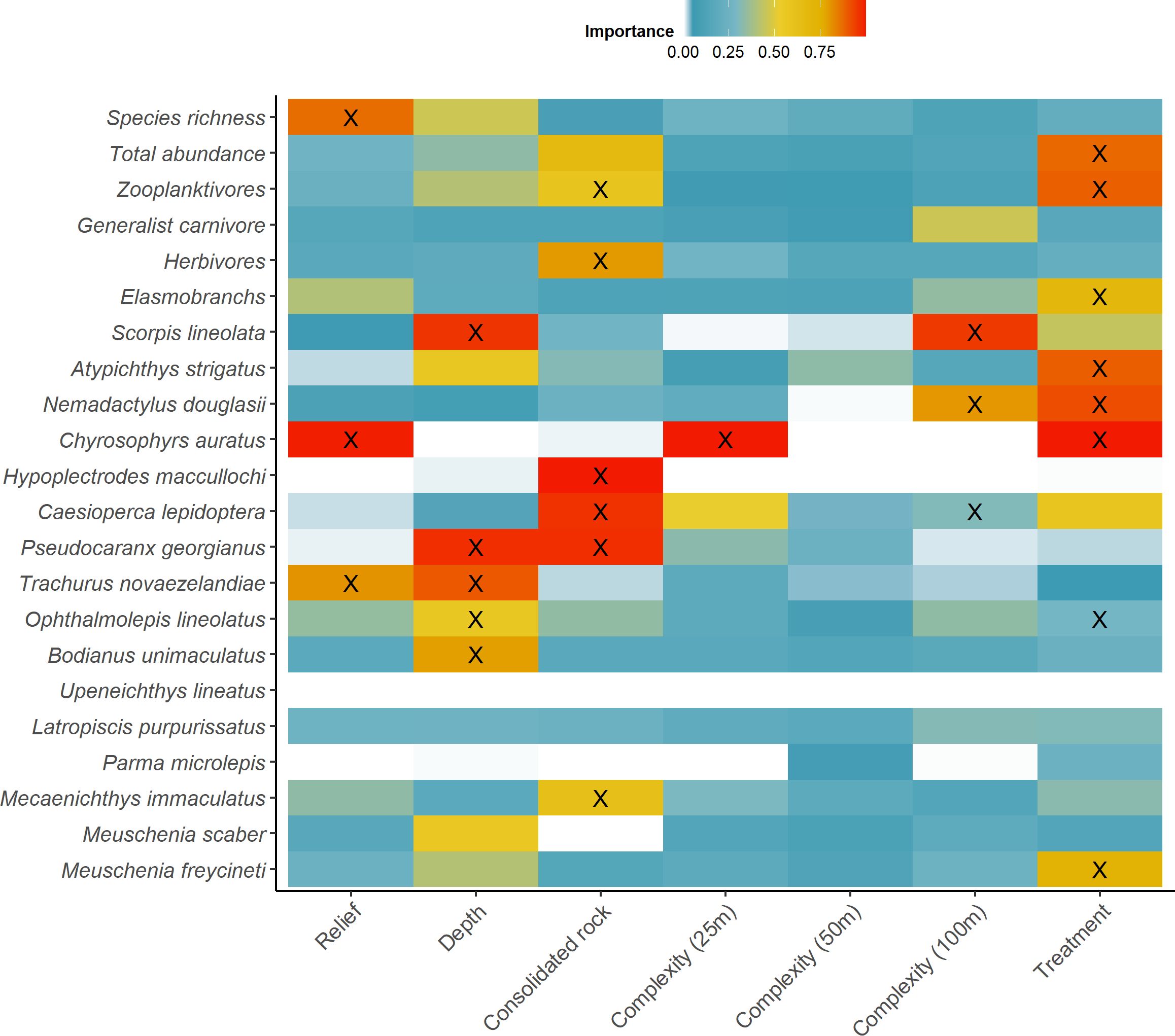

In total, we observed 68 species of temperate reef fish across 35 families from 64 BRUV deployments (4684 individuals; Supplementary Table 1). Overall, there was very strong evidence that ‘anchored’ rocky reefs influenced the total abundance of temperate reef fish observed, with both ‘anchored’ treatment and consolidated rock (%) included in the top model (Table 1; Figure 2). There were twice as many fish on ‘anchored’ reefs (98 ± 12 SE) compared to those that were ‘anchor-free’ (48 ± 6 SE) (Figure 3), with ~ 40% of the fish taxa examined containing the ‘anchored’ treatment in the top model (Table 1). Despite trends in fish abundance, anchor treatment had no effect on the richness of species occurring on rocky reefs, although as reefs increased in structural complexity, so did fish diversity (Figure 2).

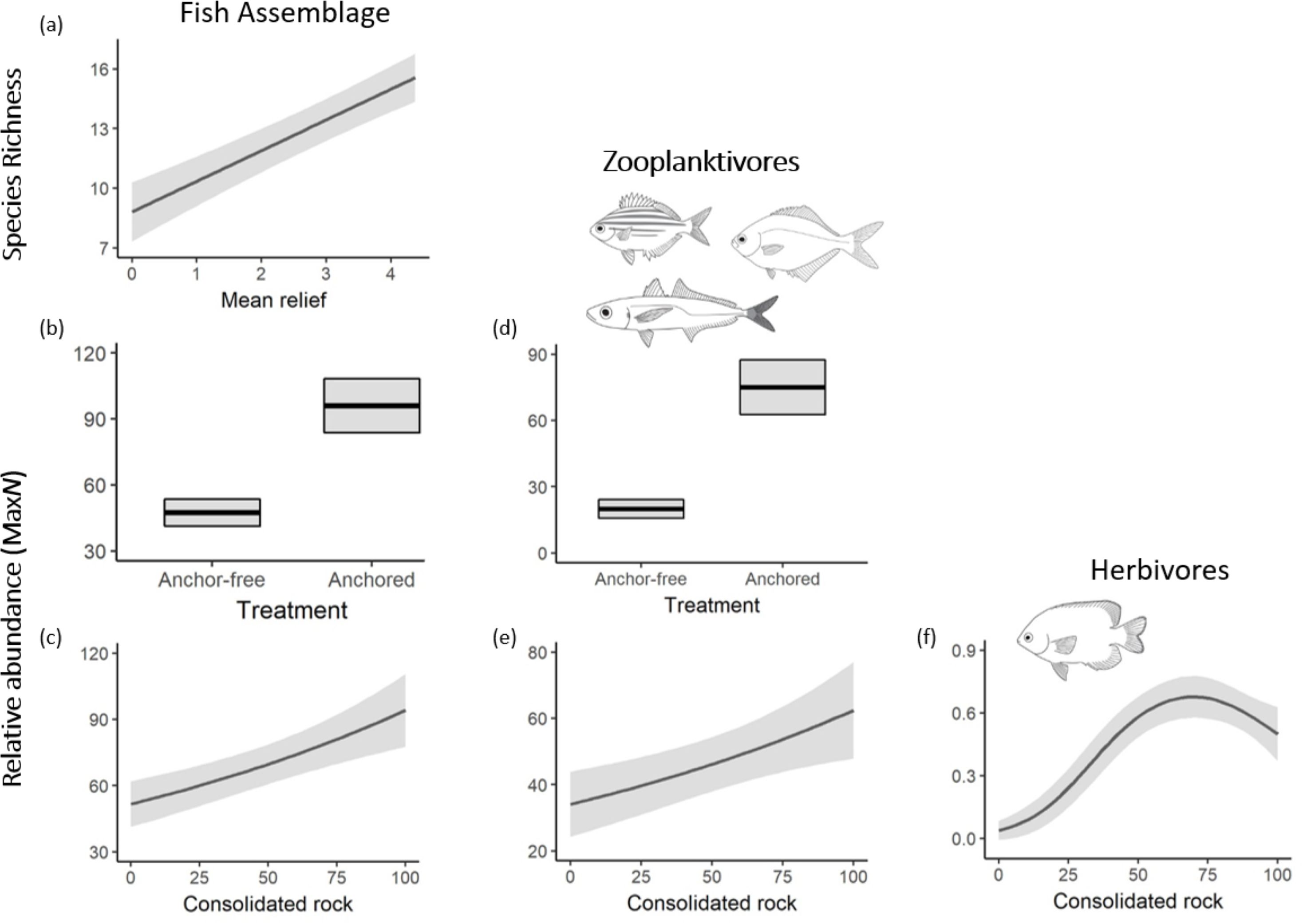

Table 1. Top generalized additive mixed models (GAMMs) for predicting the distribution of species, taxonomic or functional groups from full subset analyses based on Akaike Information Criterion corrected for small sample sizes.

Figure 2. A heat map highlighting the relative importance (0.0-1.0) of each explanatory variable (x-axes) for individual species, taxonomic or functional groups (y-axis). Relationships with response variables are indicated across a gradient; positive (red), zero (white) and negative (blue). The top models selected for the most parsimonious models are indicated (X, see Table 1). Relief: rating ranging from ‘0’ (~0°flat substrate) to ‘5’ (Vertical wall. ~90° substrate elevation) adapted from Wilson et al. (2007). Depth: ranged from 35 to 50m; Reef structural complexity (SD of bathymetry within 25m, 50m, 100m of replicate) derived from bathymetric maps; Treatment (‘anchored’ versus ‘anchor-free’).

Figure 3. Mean predictions from the best fit models (lowest AICc) for temperate reef fish across ‘anchored’ (treatment) and ‘anchor-free’ reefs for (A) species richness (SR) and (B, C) total relative abundances (MaxN) of the overall fish assemblage; (D, E) zooplanktivores and (F) herbivores; from full subset Generalized Additive Mixed Model (GAMM). Solid lines represent fitted GAMM predictions and shaded areas define standard errors ~25 and 75 quartiles around the predictions. The summary of each model is provided in Table 1.

3.2 Trophic guilds

Fishes within trophic guilds showed contrasting responses to anchor treatments. The zooplantivores, showed a distinct, almost four-fold increase in abundance on ‘anchored’ reefs (75 ± 12 SE) compared to ‘anchor-free’ reefs (~20 ± 4 SE). Increasing reefal habitat was also a strong predictor of abundance for this guild (Figure 3). Similarly, herbivores showed preference for greater rocky reef habitat (Figure 3), although they were indifferent to anchor treatments. In contrast, the null model was the most parsimonious for the abundance of generalist carnivores, indicating that neither anchoring treatment, nor any habitat features had any effect on the distribution of this trophic guild (Table 1; Figure 2).

3.3 Common taxa

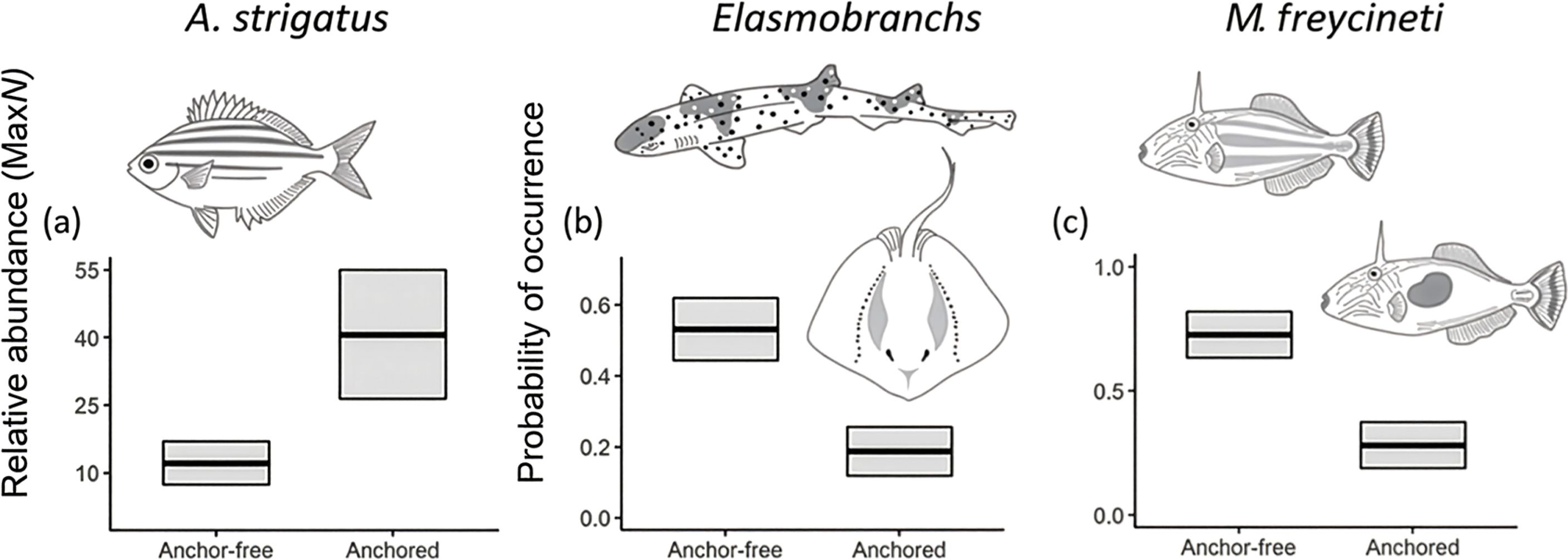

Just six of the sixteen common taxa examined (observed in >30% of samples) revealed ‘anchored’ reefs to be a strong predictor of their abundance (Table 1; Figure 2). The top model for the common shoaling, zooplanktivore, Atypichthys strigatus included ‘anchored’ reefs explaining 20% of their distribution with abundance measures more than three times greater (40 ± 14 SE) than ‘anchor-free’ reefs (12 ± 5 SE) (Figure 4). Notably, there were three top models within 2 AICc for A. strigatus with all models including the ‘anchored’ treatment (Table 1). In contrast, the probability of detection of benthic elasmobranchs and the leatherjacket, Meuschenia freycineti were three and two times more likely to be observed on ‘anchor-free’ reefs (Table 1; Figure 4).

Figure 4. Relationships of the most parsimonious model found to predict the *relative abundances (MaxN) of the species of interest; or °probability of occurrence of two taxa of interest (A) Atypichthys strigatus; (B) Elasmobranchs; (C) Meuschenia freycineti; from full subset Generalized Additive Mixed Models (GAMM). Solid lines represent fitted GAMM predictions and shaded areas define standard errors ~25 and 75 quartiles around the predictions. The summary of each model is provided in Table 1.

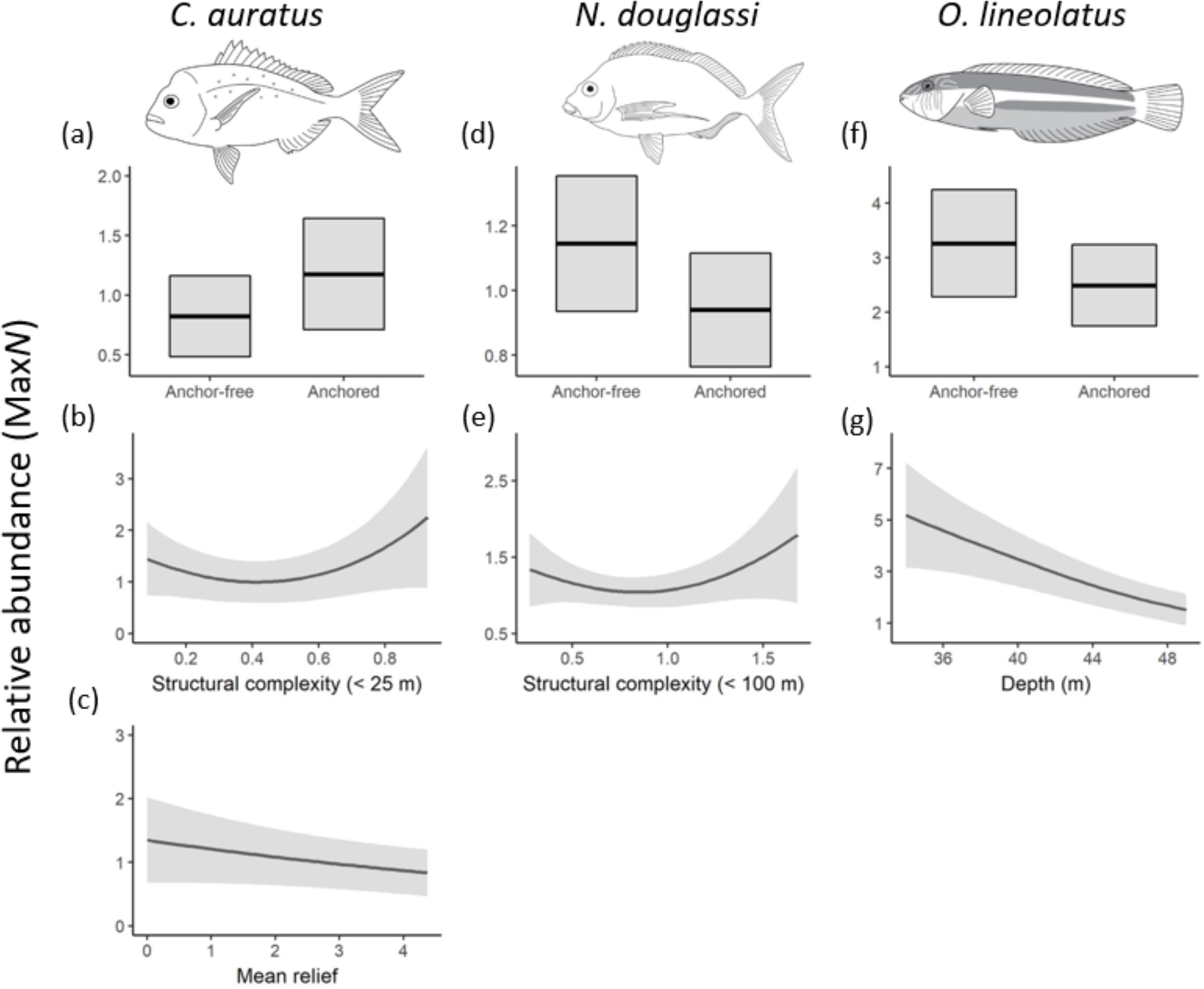

While the most parsimonious model for the occurrence of the economically valuable sparid - snapper, Chrysophrys auratus similarly included ‘anchored’ reefs and the habitat variables, mean relief and structural reef complexity (<25m) derived from bathymetric data (Table 1; Figure 2). Overall, these variables explained 30% of the abundance of snapper. Although, ‘anchored’ reefs was included in the top model, the effect size was small, and estimates had high variability (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Relationships of the most parsimonious model found to predict the relative abundances (MaxN) of the species of interest; (A-C) Chyrosophyrs auratus; (D, E); Nemadactylus douglasii; (F, G) Ophthalmolepis lineolatus; from full subset Generalized Additive Mixed Models (GAMMs). Solid lines represent fitted GAMM predictions and shaded areas define standard errors ~25 and 75 quartiles around the predictions. The summary of each model is provided in Table 1.

In comparison, the Grey Morwong Nemadactylus douglasii included ‘anchor-free’ reefs as well as reef structural complexity (<100m) in its top model and these variables explained 38% of its abundance (Table 1; Figure 2). Evidence for preference of grey morwong for undisturbed reefs was very weak, with little distinction in abundance between ‘anchored’ (0.94 ± 0.2) and ‘anchor-free’ reefs (1.14 ± 0.2) (Figure 5). Likewise, for the Maori wrasse, Ophthalmolepis lineolatus, the top model included ‘anchored’ reefs, however the effect was weak with their abundance on ‘anchor-free’ reefs being 3.3 (± 1) compared to 2.5 (± 0.7) for those disturbed (Table 1; Figure 2). In contrast, water depth was a much stronger predictor, where the abundance of Maori wrasse declined with increasing depth (Figure 5).

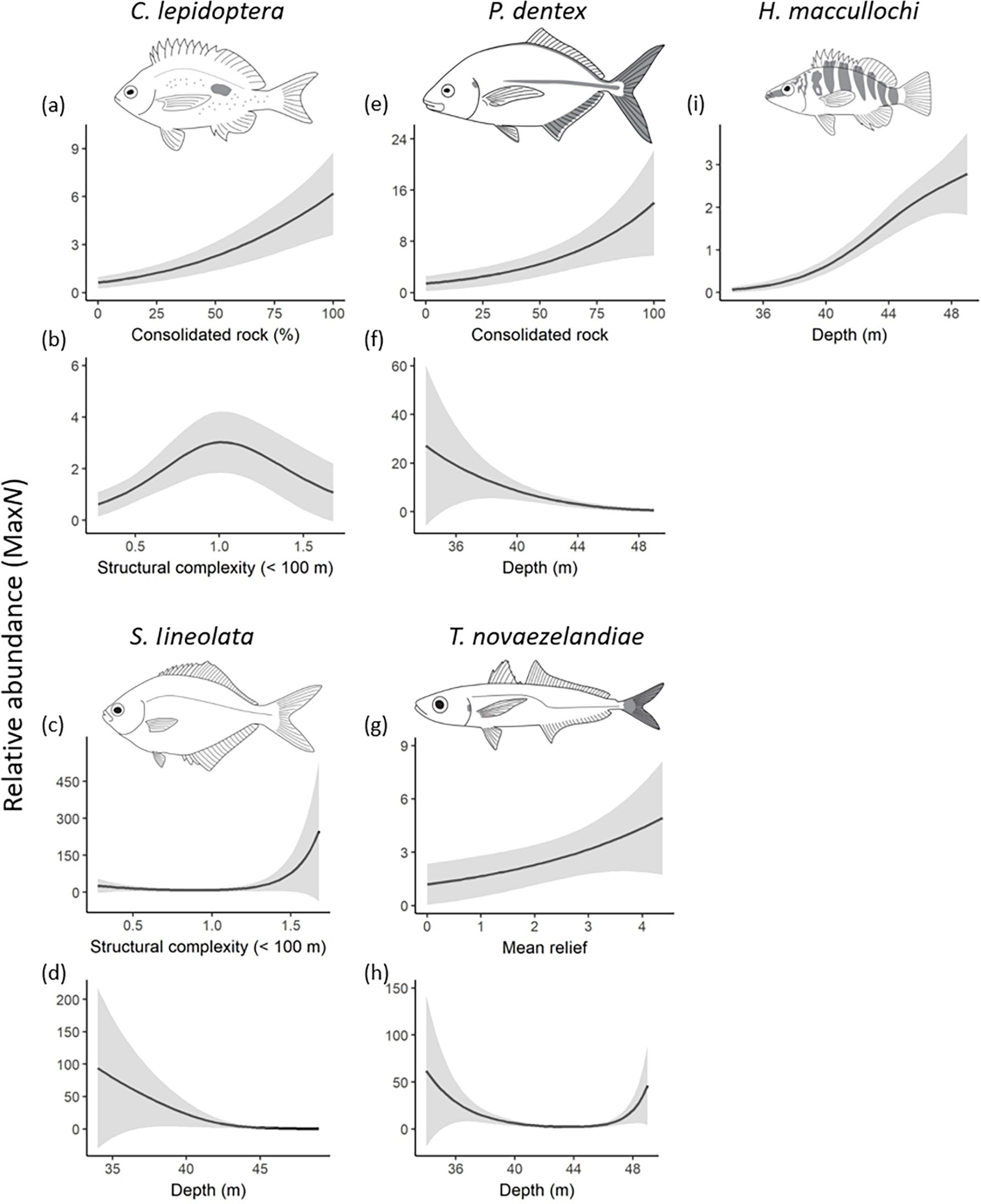

Importance scores for two of the zooplanktivores, Caesioperca lepidoptera and Scorpis lineolata indicated weak support for ‘anchored’ reefs as a predictor for their distribution (Table 1; Figure 2). Although habitat variables best explained their distributions with the top models for C. lepidoptera including increasing consolidated rock and reef structural complexity <100m (Figure 6). While the top models for S. lineolata included shallower reefs and increased reef structural complexity <100m (Table 1; Figure 2).

Figure 6. Relationships of the most parsimonious model found to predict the relative abundances (MaxN) of the species of interest. Neither anchor treatment were useful to predict the distribution of these taxa. (A, B) Caesioperca lepidoptera; (C, D) Scorpis lineolata; (E, F) Pseudocaranx dentex (G, H) Trachurus novaezelandiae; and (I) Mecaenichthys immaculatus from full subset Generalized Additive Mixed Models (GAMM). Solid lines represent fitted GAMM predictions and shaded areas define standard errors around the predictions.

Anchoring was not an important predictor for several species, including Pseudocaranx dentex, Trachurus novaezelandiae, Mecaenichthys immaculatus, Hypoplectrodes maccullochi, and Bodianus unimaculatus with habitat metrics providing more explanatory value in their spatial distribution (Table 1; Figures 2, 6). In contrast, no habitat variables included in our assessment, nor either anchor treatment, were of explanatory value in the abundance of several taxa, including Aulopus purpurissatus, Meuschenia scaber, Parma microlepis and Upeneichthys lineatus (Table 1; Figure 2).

4 Discussion

These findings point towards a complex restructure of the demersal reef fish assemblage on mesophotic rocky reefs in response to anchoring activities over large spatial scales (10’s km). Forty percent of the taxa we examined were affected by anchoring activity on reefs in some way. Negative impacts on fishes were anticipated given that mechanical disturbance degrades reef ecosystems (Broad et al., 2023) with flow-on effects expected as fishes lose habitat refugia as well as food resources (Aburto-Oropeza et al., 2015; Forrester et al., 2015; Flynn and Forrester, 2019). Surprisingly however, we observed no differences in species richness between treatments and marked increases in fish abundance; largely inflated by the zooplanktivore trophic guild. These outcomes are in stark contrast with the findings of anchoring research on tropical coral reefs; there researchers reported declines in both species’ diversity and fish abundance, with 95% declines in the abundance of sponge-feeding fishes on disturbed reefs (Flynn and Forrester, 2019).

More surprising was our observation that ‘anchored’ reefs benefitted some taxa. Fishes in the zooplanktivore trophic guild typically dominate fish assemblages in this region, making up almost half of the biomass on temperate rocky reefs in SE Australia (Champion et al., 2015; Truong et al., 2017), yet their abundance increased a further three-fold on reefs disturbed by anchors. There is clear evidence from several studies that taxa from this trophic guild respond positively to seabed disturbance (Pauly et al., 1998). For example, using manipulative experiments in SE Australia, researchers report increases in planktivorous fish >200% in response to water discharged from desalinization plants installed on rocky reefs (Kelaher et al., 2020). Similarly, zooplanktivores in the Gulf of California, Mexico also proliferated in response to increased disturbance from industrial bottom fishing on rocky reefs (Aburto-Oropeza et al., 2015). An important local representative of the zooplankivore guild - mado, Atypichthys strigatus, the dominant zooplanktivore we observed, saw near four-fold increases in response to ‘anchored’ reefs. We suggest two possible mechanisms contributing to these findings. First, there is experimental evidence that mado respond to mechanical disturbances with increased feeding rates (Glasby and Kingsford, 1994), which suggests movement of anchor gear over the substratum mobilizes small benthic organisms into the water column, thereby increasing the foraging potential for zooplanktivores. Secondly, the provision of emergent structures extending into the water column associated with the presence of large vessels (Røstad et al., 2006) and their anchor chains may provide protective shelter for this group accounting for their increased abundance (Champion et al., 2015).

Although zooplanktivores were more abundant on ‘anchored’ reefs, strong evidence shows that the presence of vessels and anchoring processes negatively affects certain taxa, with distinct responses to disturbed reefs. Mechanical disturbances from anchoring and benthic fishing trawls consistently show evidence of removal of complex biogenic habitats on reefs (Forrester et al., 2015; Aburto-Oropeza et al., 2015; Flynn and Forrester, 2019; Broad et al., 2023) with negative implications for macrofauna on reefs (eg. the ‘sponge-loop’ - see Bart et al., 2021) as well as the demersal reef fish associated with them (Kenchington et al., 2013). In our study, several demersal reef fish were more likely to occur on ‘anchor-free’ reefs that are known to support up-to seven times higher densities of Marine Animal Forest (MAF) taxa when compared to reefs disturbed by anchoring (Broad et al., 2023). We observed distinct 3-fold reductions in the likelihood of observing demersal elasmobranchs and the six-spine leatherjacket Meuschenia freycineti on ‘anchored’ reefs that are largely devoid of epifauna (Broad et al., 2023). Similar, yet weaker trends, were also observed for the maori wrasse, O. lineolatus and grey morwong Nemadactylus douglassi – unsurprising, given that all of these fishes are closely tied with MAF taxa such as sponges, hydroids and bryozoans (Curley et al., 2013; Henderson et al., 2020).

Significant reductions of MAF taxa can reduce animal ‘fitness’ for fish that forage within these systems, expending greater energy searching for food in a depleted ‘foodscape’ as well as avoiding perceived threats where protective habitat has been lost (Roberts et al., 2016; Chapuis et al., 2019; Dwinnell et al., 2019). As an example, benthic elasmobranchs are often closely associated with Marine Animal Forest taxa on reefal habitats throughout all their life stages (Kenchington et al., 2013; O’Neill et al., 2024). Reductions in sessile biota will likely affect this groups capacity to complete their life cycle, with decreases in habitat refugia or food availability. In field experiments, small benthic sharks have been shown to utilize sessile biota for position-holding to sustain alignment with water currents (rheotaxis; Peach, 2002). In more novel findings, high abundances of juvenile catsharks have been reported inhabiting the internal filtration structures of large sponges (O’Neill et al., 2024). Moreover, numerous elasmobranchs secure their egg-casings on reefal habitats, with research indicating their preference for egg deposition on sessile biota over other substrata (Ellis and Shackley, 1997; Carraro and Gladstone, 2006; Vasquez et al., 2018). In addition, many of the elasmobranchs in this study are known or are predicted to feed on the egg casings deposited on sessile biota (Powter and Gladstone, 2008) further reducing the availability of food resources on denuded reefs.

To date, anchoring disturbances from global shipping remain largely unmanaged, which has consistently shown evidence of alterations to the structure of marine assemblages across a range of habitats (Davis, 1977; Backhurst and Cole, 2000; Rogers and Garrison, 2001; Forrester et al., 2015; Lanham et al., 2018; Broad et al., 2023; Davis et al., 2025). We encourage marine managers and decision makers across all levels of government and private industry to focus on reducing the need to anchor wherever possible and when necessary, aim to reduce the spatial area disturbed by anchoring (Davis et al., 2016; Steele et al., 2017). Immediate steps that can be considered to reduce anchoring impacts on marine systems include:

1. Raise Awareness: Promote understanding of anchoring-related disturbances among maritime industries and regulators, as this longstanding practice has traditionally been overlooked.

2. Enforce Designated Anchorages: Ensure vessels anchor within designated zones, with active monitoring and communication from port authorities to improve compliance (Steele et al., 2017).

3. Plan for Emergency Anchorages: Designate anchorage zones for use during exceptional circumstances (Davis et al., 2022).

4. Implement Vessel Arrival Systems (VAS): Encourage single-commodity ports to coordinate ship arrivals, minimizing unnecessary anchoring (Heaver, 2021).

5. Promote Dynamic Positioning: In high conservation areas, advocate for dynamic positioning systems over short-term anchoring (Mulrennan et al., 2025).

6. Use Seabed Mapping for Environmental Risk Assessment: Identify sensitive habitats and their biota to inform the designation of well-planned, new anchorages that avoid ‘at-risk’ environments.

Finally, detailed knowledge of local seabed habitats of high conservation value should be identified and avoided at all costs, and this requires regulatory support for marine managers through well-enforced policies (Jimenez et al., 2025). It is pertinent to balance environmental protection with social and economic needs, however this can only be achieved through collaboration amongst stakeholders—including governments, international agencies, and the shipping industry.

5 Conclusions

Anchoring associated with global trade is disturbing seabed environments over large areas (>1000’s m2) (Davis et al., 2022; Watson et al., 2022), yet quantitative studies examining impacts to biota have been largely overlooked (Broad et al., 2020) and are in their infancy (Broad et al., 2023). Here, we present the first, replicated empirical examination of the abundance of demersal reef fishes in response to anchoring activities from commercial trading ships (>100m). We provide evidence that anchoring activities are likely to have population-level effects on demersal reef fish across taxonomic (species and subclass levels) and trophic guilds on temperate reefs. These findings indicate potential changes in ecological function within the anchor roadstead. Given that shipping is the pillar of global trade, we encourage future research to investigate a range of anchoring stressors (eg. noise generated by ships at anchor) and their impacts to a range of biota and seabed habitats. In addition, research should seek to characterize the mechanisms that drive these changes, as failure to manage the impacts of anchoring near ports is likely to result in reductions of seabed biodiversity (Broad et al., 2023) as well as compromise highly valuable fisheries resources and associated ecosystem services (Gaylard et al., 2020). Maintaining marine biota remains one of the crucial focal areas in the environmental management of the planet as a whole (Smith, 2000; McCauley et al., 2015; Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission [IOC], 2020); this requires strong regulatory support across all levels of government if we are to sustain marine life (UN [United Nations], 2015 [SDG14: Life below water]) and the economic benefits derived from them (Bennett et al., 2016; UN [United Nations], 2015 [SDG 9: Industries, innovation and infrastructure]).

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by University of Wollongong Animal Ethics (Permit AE12/07r15). The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

AB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Validation, Data curation, Visualization, Resources, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MR: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Validation, Visualization, Resources, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. TI: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Validation, Visualization, Resources, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. BM: Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Visualization, Resources, Writing – review & editing. AD: Conceptualization, Investigation, Validation, Resources, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was primarily supported by the University of Wollongong’s Global Challenges Program – Sustaining Coastal and Marine Zones, along with the Centre for Sustainable Ecosystem Solutions. Additional financial support from the Max Day Environmental Science Fellowship Award (Australian Academy of Science) and Paddy Pallin Research Grant (Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales) helped cement our ideas and is gratefully acknowledged. AB wished to acknowledge support from an Australian Postgraduate Research Scholarship Program (Department of Education, Skills and Employment) and the Gowrie Scholarship (The Australian National University on behalf of the Gowrie Trust). MJR’s salary, as well as creation of the fish illustrations was supported and funded by the NSW State Government’s Marine Estate Management Strategy.

Acknowledgments

In addition to the funding support outlined above, we wish to thank Nathan Knott (NSW Department of Primary Industries & Regional Development) for general advice relating to this work, as well as those who reviewed the article and provided thoughtful comments and advice. Thanks also to Kylie Brown for creation of our fish illustrations.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcosc.2025.1650920/full#supplementary-material

References

Aburto-Oropeza O., Ezcurra E., Moxley J., Sánchez-Rodríguez A., Mascareñas-Osorio I., Sánchez-Ortiz C., et al. (2015). A framework to assess the health of rocky reefs linking geomorphology, community assemblage, and fish biomass. Ecol. Indic. 5, 353–361. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2014.12.006

Althaus F., Hill N., Ferrari Legorreta R., Edwards L., Przeslawski R., Schoenberg C., et al. (2015). A standardised vocabulary for identifying benthic biota and substrata from underwater imagery: the CATAMI classification scheme. PloS One 10, e0141039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141039

Alvarez-Filip L., Dulvy N. K., Gill J. A., Côté I. M., and Watkinson A. R. (2009). Flattening of Caribbean coral reefs: region-wide declines in architectural complexity. Proc. R. Soc B: Biol. Sci. 276, 3019–3025.

Assis J., Coelho N. C., Lamy T., Valero M., Alberto F., and Serrão E.Á. (2016). Deep reefs are climatic refugia for genetic diversity of marine forests. J. Biogeo. 43, 833–844. doi: 10.1111/jbi.12677

Backhurst M. K. and Cole R. G. (2000). Biological impacts of boating at Kawau Island, North-Eastern New Zealand. J. Environ. Manage. 60, 239–251. doi: 10.1006/jema.2000.0382

Bart M. C., Hudspith M., Rapp H. T., Verdonschot P. F., and De Goeij J. M. (2021). A deep-sea sponge loop? Sponges transfer dissolved and particulate organic carbon and nitrogen to associated fauna. Front. Mar. Sci. 8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.604879

Bell J. D., Burchmore J. J., and Pollard D. A. (1978). Feeding ecology of three sympatric species of leatherjackets (Pisces: Monacanthidae) from a Posidonia seagrass in New South Wales. Aust. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 29, 631–643. doi: 10.1071/MF9780631

Bennett S., Wernberg T., Connell S. D., Hobday A. J., Johnson C. R., and Poloczanska E. S. (2016). The ‘Great Southern Reef’: social, ecological and economic value of Australia’s neglected kelp forests. Mar. Freshw. Res. 67, 47–56. doi: 10.1071/MF15232

BMT WBM (2017). New South Wales Marine Estate Threat and Risk Assessment Report Final Report (Broadmeadow, NSW: BMT WBM Pty Ltd).

Bongaerts P., Ridgway T., Sampayo E., and Hoegh-Guldberg O. (2010). Assessing the ‘deep reef refugia’ hypothesis: focus on Caribbean reefs. Coral Reefs. 29, 309–327. doi: 10.1007/s00338-009-0581-x

Broad A., Rees M. J., and Davis A. R. (2020). Anchor and chain scour as disturbance agents in benthic environments: Trends in the literature and charting a course to more sustainable boating and shipping. Mar. pollut. Bull. 161, 111683–111683. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111683

Broad A., Rees M., Knott N., Swadling D., Hammond M., Ingleton T., et al. (2023). Anchor scour from shipping and the defaunation of rocky reefs: A quantitative assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 863, 160717. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.160717

Bulman C., Althaus F., He X., Bax N. J., and Williams A. (2001). Diets and trophic guilds of demersal fishes of the south-eastern Australian shelf. Mar. Freshw. Res. 52, 537–548. doi: 10.1071/MF99152

Burnham K. P. and Anderson D. R. (2002). Model Selection and Multimodel Inference (New York, NY: Springer).

Carraro R. and Gladstone W. (2006). fin habitat preferences and site fidelity of the ornate wobbegong shark (Orectolobus ornatus) on rocky reefs of New South Wales. Pacific Sci. 60, 207–223. doi: 10.1353/psc.2006.0003

Champion C., Suthers I., and Smith J. (2015). Zooplanktivory is a key process for fish production on a coastal artificial reef. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 541, 1–14. doi: 10.3354/meps11529

Chapuis L., Collin S., Yopak K., McCauley R., Kempster R., Ryan L., et al. (2019). The effect of underwater sounds on shark behaviour. Sci. Rep. 9, 6924. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43078-w

Choat J. H. and Ayling A. M. (1987). The relationship between habitat structure and fish faunas on New Zealand reefs. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 110, 257–284. doi: 10.1016/0022-0981(87)90005-0

Curley B. G., Jordan A. R., Figueira W. F., and Valenzuela V. (2013). A review of the biology and ecology of key fishes targeted by coastal fisheries in south-east Australia: identifying critical knowledge gaps required to improve spatial management. Rev. Fish Biol. Fisheries. 23, 435–458. doi: 10.1007/s11160-013-9309-7

Davis G. E. (1977). Anchor damage to a coral reef on the coast of Florida. Biol. Conserv. 11, 29–34. doi: 10.1016/0006-3207(77)90024-6

Davis A. R., Broad A., Gullett W., Reveley J., Steele C., and Schofield C. (2016). Anchors away? The impacts of anchor scour by ocean-going vessels and potential response options. Mar. Pol. 73, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2016.07.021

Davis A. R., Broad A., Small M., Oxenford H. A., Morris B., and Ingleton T. C. (2022). Mapping of benthic ecosystems: Key to improving the management and sustainability of anchoring practices for ocean-going vessels. Cont. Shelf Res. 247, 104834. doi: 10.1016/j.csr.2022.104834

Davis A. R., Broad A., Steele C., Woods C., Przeslawski R., Nicholas W. A., et al. (2025). Dragging the chain: anchor scour impacts from high-tonnage commercial vessels on a soft bottom macrobenthic assemblage. Front. Conserv. Sci. 6, 1487428.

Deter J., Lozupone X., Inacio A., Boissery P., and Holon F. (2017). Boat anchoring pressure on coastal seabed: Quantification and bias estimation using AIS data. Mar. Poll. Bull. 123, 175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.08.065

Dwinnell S., Sawyer H., Randall J. E., Beck J. L., Forbey J. S., Fralick G. L., et al. (2019). Where to forage when afraid: Does perceived risk impair use of the foodscape? Ecol. Applic. 29, e01972. doi: 10.1002/eap.1972

Ellis J. R. and Shackley S. E. (1997). The reproductive biology of Scyliorhinus canicula in the Bristol Channel, UK. J. Fish Biol. 51, 361–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.1997.tb01672.x

Fisher R., Wilson S. K., Sin T. M., Lee A. C., and Langlois T. J. (2018). A simple function for full-subsets multiple regression in ecology with R. Ecol. Evol. 8, 6104–6113. doi: 10.1002/ece3.4134

Flynn R. L. and Forrester G. E. (2019). Boat anchoring contributes substantially to coral reef degradation in the British Virgin Islands. Peer J. 7, e7010. doi: 10.7717/peerj.7010

Forrester G. E., Flynn R. L., Forrester L. M., and Jarecki L. L. (2015). Episodic Disturbance from Boat Anchoring Is a Major Contributor to, but Does Not Alter the Trajectory of, Long-Term Coral Reef Decline. PloS One 10, 1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144498

Gaylard S., Waycott M., and Lavery P. (2020). Review of coast and marine ecosystems in temperate Australia demonstrates a wealth of ecosystem services. Front. Mar. Sci. 7. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.00453

Glasby T. M. and Kingsford M. J. (1994). Atypichthys strigatus (Pisces: Scorpididae): An opportunistic planktivore that responds to benthic disturbances and cleans other fishes. Aust. J. Ecol. 19, 385–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9993.1994.tb00504.x

Graham M. H. (2003). Confronting multicollinearity in ecological multiple regression. Ecol. 84, 2809–2815. doi: 10.1890/02-3114

Harasti D., Malcolm H., Gallen C., Coleman M. A., Jordan A., and Knott N. A. (2015). Appropriate set times to represent patterns of rocky reef fishes using baited video. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 463, 173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2014.12.003

Harrison X. A. (2014). Using observation-level random effects to model overdispersion in count data in ecology and evolution. PeerJ. 9, e616. doi: 10.7717/peerj.616

Harvey E., Cappo M., Butler J. J., Hall N., and Kendrick G. (2007). Bait attraction affects the performance of remote underwater video stations in assessment of demersal fish community structure. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 350, 245–254. doi: 10.3354/meps07192

Hastie T. J. (1990). Generalized Additive Models. 1st ed (New York: Routledge). doi: 10.1201/9780203753781

Hastie T. and Tibshirani R. (1986). Generalized additive models. Stat. Sci. 1, 297–310. doi: 10.1214/ss/1177013604

Heaver T. D. (2021). Reducing anchorage in ports: changing technologies, opportunities and challenges. Front. Future Transp. 2, 709762. doi: 10.3389/ffutr.2021.709762

Henderson M. J., Huff D. D., and Yoklavich M. M. (2020). Deep-sea coral and sponge taxa increase demersal fish diversity and the probability of fish presence. Front. Mar. Sci. 7. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.593844

Ibon G. I. (2013). New method for mapping seafloor ecosystems. Science for Environment Policy. Thematic issue: Seafloor Damage. Published by the European Commission’s Directorate-General Environment (45), 10–11 pp. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/integration/research/newsalert/pdf/45si.pdf. Environment Science and Policy. 10.

Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission [IOC] (2020). The Science we need for the ocean we want: the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development, (2021–2030) (UNESCO: Paris). Available online at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000265198.

Jägerbrand A. K., Brutemark A., Barthel Svedén J., and Gren I. (2019). A review on the environmental impacts of shipping on aquatic and nearshore ecosystems. Sci. Tot. Environ. 695, 133637. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.133637

Jimenez C., Papatheodoulou M., Resaikos V., and Petrou A. (2025). Wholesale destruction inside a marine protected area: anchoring impacts on sciaphilic communities and coralligenous concretions in the eastern mediterranean. Water 17, 2092. doi: 10.3390/w17142092

Joseph L. N., Field S. A., Wilcox C., and Possingham H. P. (2006). Presence-absence versus abundance data for monitoring threatened species. Conserv. Biol. 20, 1679–1687. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00529.x

Kelaher B. P., Clark G. F., Johnston E. L., and Coleman M. A. (2020). Effect of desalination discharge on the abundance and diversity of reef fishes. Environ. Sci. Tech. 54, 735–744. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.9b03565

Kelaher B. P., Coleman M. A., Broad A., Rees M. J., Jordan A., and Davis A. R. (2014). Changes in fish assemblages following the establishment of a network of no-take marine reserves and partially-protected areas. PloS One 9, e85825. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085825

Kenchington E., Power D., and Koen-Alonso M. (2013). Associations of demersal fish with sponge grounds on the continental slopes of the northwest Atlantic. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 477, 217–230. doi: 10.3354/meps10127

Kiggins R. S., Knott N. A., and Davis A. R. (2018). Miniature baited remote underwater video (mini-BRUV) reveals the response of cryptic fishes to seagrass cover. Environ. Biol. Fish. 101, 1717–1722. doi: 10.1007/s10641-018-0823-2

Knott N. A., Williams J., Harasti D., Malcolm H. A., Coleman M. A., Kelaher B. P., Rees M. J., Schultz A., and Jordan A. (2021). A coherent, representative, and bioregional marine reserve network shows consistent change in rocky reef fish assemblages. Ecosphere 12 (4), e03447. doi: 10.1002/ecs2.3447

Langlois T. J. (2017). Habitat-annotation-of-forward-facing- benthic-imagery: R code and user manual version 1.0.1. Zenodo. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.893622

Lanham B. S., Vergés A., Hedge L. H., Johnston E. L., and Poore A. G. B. (2018). Altered fish community and feeding behaviour in close proximity to boat moorings in an urban estuary. Mar. Poll. Bull. 129, 43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.02.010

Linklater M., Ingleton T. C., Kinsela M. A., Morris B. D., Allen K. M., Sutherland M. D., et al. (2019). Techniques for classifying seabed morphology and composition on a subtropical-temperate continental shelf. Geosci. 9, 141. doi: 10.3390/geosciences9030141

Malcolm H. A., Gladstone W., Lindfield S., Wraith J., and Lynch T. P. (2007). Spatial and temporal variation in reef fish assemblages of marine parks in New South Wales, Australia - baited video observations. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 350, 277–290. doi: 10.3354/meps07195

McCauley D. J., Pinsky M. L., Palumbi S. R., Estes J. A., Joyce F. H., and Warner R. R. (2015). Marine defaunation: Animal loss in the global ocean. Sci. 347, 1255641. doi: 10.1126/science.1255641

McLean D. L., Langlois T. J., Newman S. J., Holmes T. H., Birt M. J., Bornt K. R., et al. (2016). Distribution, abundance, diversity and habitat associations of fishes across a bioregion experiencing rapid coastal development. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 178, 36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2016.05.026

Mulrennan M., Graham M., Herbig J., and Watson S. J. (2025). Anchor and chain damage to seafloor habitats in Antarctica: first observations. Front. Conserv. Sci. 6, 1500652.

O’Neill H. L., White W. T., Pogonoski J. J., Alvarez B., Gomez O., and Keesing J. K. (2024). Sharks checking in to the sponge hotel: First internal use of sponges of the genus Agelas and family Irciniidae by banded sand catsharks Atelomycterus fasciatus. J. Fish Biol. 104, 304–309. doi: 10.1111/jfb.15554

Pauly D., Christensen V., Dalsgaard J., Froese R., and Torres F. Jr. (1998). Fishing down marine food webs. Sci 279, 860–863. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5352.860

Peach M. (2002). Rheotaxis by epaulette sharks, Hemiscyllium ocellatum (Chondrichthyes: Hemiscylliidae), on a coral reef flat. Aust. J. Zool. 50, 407–414. doi: 10.1071/ZO01081

Pickett S. T. A. and White P. S. (1985). The Ecology of Natural Disturbance and Patch Dynamics (Academic Press), 472.

Powter D. M. and Gladstone W. (2008). Embryonic mortality and predation on egg capsules of the Port Jackson shark Heterodontus portusjacksoni (Meyer). J. Fish Biol. 72, 573–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2007.01721.x

Qi X., Li Z., Zhao C., Zhang Q., and Zhou Y. (2024). Environmental impacts of Arctic shipping activities: A review. Ocean Coast. Manage. 247, 106936. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2023.106936

Rees M. J., Knott N. A., and Davis A. R. (2018a). Habitat and seascape patterns drive spatial variability in temperate fish assemblages: implications for marine protected areas. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 607, 171–186. doi: 10.3354/meps12790

Rees M. J., Knott N. A., Neilson J., Linklater M., Osterloh I., Jordan A., et al. (2018b). Accounting for habitat structural complexity improves the assessment of performance in no-take marine reserves. Biol. Conserv. 224, 100–110. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2018.04.040

Rees M. J., Knott N. A., Hing M. L., Hammond M., Williams J., Neilson J., et al. (2021). Habitat and humans predict the distribution of juvenile and adult snapper (Sparidae: Chrysophrys auratus) along Australia’s most populated coastline. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 257, 107397. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2021.107397

Roberts L., Pérez-Domínguez R., and Elliott E. (2016). Use of baited remote underwater video (BRUV) and motion analysis for studying the impacts of underwater noise upon free ranging fish and implications for marine energy management. Mar. Poll. Bull. 112, 75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.08.039

Rogers C. S. and Garrison V. H. (2001). Ten years after the crime, lasting effects of damage from a cruise ship anchor on a coral reef in St. John, U.S. Virgin Islands. B. Mar. Sci. 69, 793–803.

Rossi S., Bramanti L., Gori A., and Orejas C. (2017). Animal forests of the world: an overview. Centro Oceanográfico Baleares, 1–28.

Røstad A., Kaartvedt S., Klevjer T. A., and Melle W. (2006). Fish are attracted to vessels. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 63, 1431–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.icesjms.2006.03.026

Schramm K. D., Harvey E. S., Goetze J. S., Travers M. J., Warnock B., and Saunders B. J. (2020). A comparison of stereo-BRUV, diver operated and remote stereo-video transects for assessing reef fish assemblages. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 524, 151273. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2019.151273

Smith H. D. (2000). The industrialization of the world ocean. Ocean Coast. Manage. 43, 11–28. doi: 10.1016/S0964-5691(00)00028-4

Steele C., Broad A., Ingleton T., and Davis A. R. (2017). “Anchors aweigh? The visible and invisible effects of anchored ocean-going vessels,” in Australasian Coasts and Ports 2017: Working with Nature (Engineers Australia, PIANC Australia and Institute of Professional Engineers New Zealand, Barton, ACT), 1017–1022.

Swadling D. S., Knott N. A., Rees M. J., and Davis A. R. (2019). Temperate zone coastal seascapes: Seascape patterning and adjacent seagrass habitat drive influence the distribution of rocky reef fish assemblages. Landsc. Ecol. 34, 2337–2352. doi: 10.1007/s10980-019-00892-x

Truong L., Suthers I. M., Cruz D. O., and Smith J. A. (2017). Plankton supports the majority of fish biomass on temperate rocky reefs. Mar. Biol. 164, 1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00227-017-3101-5

Tuya F., Wernberg T., and Thomsen M. S. (2009). Habitat structure affects abundances of labrid fishes across temperate reefs in south-western Australia. Environ. Biol. Fish. 86, 311–319. doi: 10.1007/s10641-009-9520-5

Tweedie M. C. K. (1984). “An index which distinguishes between some important exponential families. In: Ghosh J. K. and Roy J. Eds., Statistics: Applications and New Directions,” in Proceedings of the Indian Statistical Institute Golden Jubilee International Conference, Indian Statistical Institute, Calcutta. 579–604.

UN [United Nations] (2015). The UN Sustainable Development Goals (New York: United Nations). Available online at: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/summit/UNSDG.

UNCTAD [United Nations Conference on Trade and Development] (2024). Review of Maritime Transport 2024. UNCTAD/RMT/2024. Available online at: https://unctad.org/publication/review-maritime-transport-2024 (Accessed November 14, 2024).

Vasquez D. M., Belleggia M., Schejter L., and Mabragaña E. (2018). Avoiding being dragged away: finding egg cases of Schroederichthys bivius (Chondrichthyes: Scyliorhinidae) associated with benthic invertebrates. J. Fish. Biol. 92, 248–253. doi: 10.1111/jfb.13490

Watson D. L., Harvey E. S., Anderson M. J., and Kendrick G. A. (2005). A comparison of temperate reef fish assemblages recorded by three underwater stereo-video techniques. Mar. Biol. 148, 415–425. doi: 10.1007/s00227-005-0090-6

Watson S. J., Neil H., Ribó M., Lamarche G., Strachan L. J., MacKay K., et al. (2020). What we do in the shallows: natural and anthropogenic seafloor geomorphologies in a drowned river valley, New Zealand. Front. Mar. Sci. 7. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.579626

Watson S. J., Ribó M., Seabrook S., Strachan L. J., Hale R., and Lamarche G. (2022). The footprint of ship anchoring on the seafloor. Sci. Rep. 12, 7500. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-11627-5

Wickham H. (2016). ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Springer-Verlag New York). doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-24277-4_9

Wickham H., François R., Henry L., and Müller K. (2020). dplyr: A grammar of data manipulation. Available online at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr (Accessed February 22, 2024).

Wilson S. K., Graham N. A. J., and Polunin N. V. C. (2007). Appraisal of visual assessments of habitat complexity and benthic composition on coral reefs. Mar. Biol. 151, 1069–1076. doi: 10.1007/s00227-006-0538-3

Wood S. N. (2011). Fast stable restricted maximum likelihood and marginal likelihood estimation of semiparametric generalized linear models. J. R. Stat. Soc B. 73, 3–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9868.2010.00749.x

Keywords: global trade, high-tonnage vessels, mesophotic depths, stressors, zooplanktivores, elasmobranchs, marine animal forests

Citation: Broad A, Rees MJ, Ingleton TC, Morris B and Davis AR (2025) Anchoring from shipping as a disturbance agent to temperate rocky reef fish: marked shifts observed in trophic and taxonomic guilds. Front. Conserv. Sci. 6:1650920. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2025.1650920

Received: 20 June 2025; Accepted: 22 September 2025;

Published: 17 November 2025.

Edited by:

Ana Teresa Marques, Centro de Investigacao em Biodiversidade e Recursos Geneticos (CIBIO-InBIO), PortugalReviewed by:

Juan Pablo Torres-Florez, Buro Happold, Saudi ArabiaTuğçe Şensurat Genç, Izmir Katip Celebi University, Türkiye

Copyright © 2025 Broad, Rees, Ingleton, Morris and Davis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Allison Broad, YWxsaXNvbmJAdW93LmVkdS5hdQ==

Allison Broad

Allison Broad Matthew J. Rees

Matthew J. Rees Timothy C. Ingleton

Timothy C. Ingleton Bradley Morris

Bradley Morris Andrew R. Davis

Andrew R. Davis