- 1Department of Freshwater and Fishery Sciences, Chinhoyi University of Technology, Chinhoyi, Zimbabwe

- 2Faculty of Science, Department of Biological Sciences and Ecology, University of Zimbabwe, Harare, Zimbabwe

Capture fisheries, crocodile ranching, and aquaculture provide vital food resources for enhanced food security and nutrition and sustain livelihoods in Southern Africa. Conflicting policies, regulations, and institutional overlaps affect the operation and management of capture fisheries, crocodile ranching, and aquaculture, threatening their sustainability. This scoping review examined the evolution of fisheries, aquaculture, and crocodile farming governance from 1890 to 2021 in Zimbabwe within the Southern African policy context. This aims (i) to identify the legal and policy frameworks for capture fisheries, crocodile farming, and aquaculture firms in Southern Africa and Zimbabwe; (ii) to explore the evolution and gaps in the legislation and policies for capture fisheries, crocodile farming, and aquaculture firms in Southern Africa and Zimbabwe; and (iii) to highlight the strengths and future dimensions for developing prudent management policies for fisheries, crocodile ranching, and aquaculture. Five concatenated evolutionary phases, that is, the soft conservation period (1866–1890), the establishment period (1891–1938), the consolidation of fisheries and crocodile conservation period (1938–1961), the quintessential conservation period (1962–1978), and the conservation progression period (1980–2021)—punctuated by persistent neglect of aquaculture and crocodile ranching, institutional overlaps, and the prominent influence of affluent recreational angling societies on fisheries policy development were identified for Zimbabwe. Within Southern Africa, the evolution of fisheries and aquaculture policies has been more rapid for countries with coastal (marine) and inland freshwater resources such as Namibia, Cape Verde, the Comoros Islands, Seychelles, Madagascar, Mauritius, South Africa, and Tanzania. Armed conflicts slowed (or are slowing) down the evolutionary pace of fisheries and aquaculture policies in Angola, Mozambique, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Aquaculture is still a fledgling industry; thus, development of the relevant consolidated aquaculture and fisheries governing policies is still in its infancy across Southern Africa. This necessitates standalone, harmonized aquaculture and fisheries policies. Zimbabwe, like all Southern African Development Community (SADC) member states, needs to align its fisheries and aquaculture policies with the SADC Fisheries Sector Policy as guided by the Policy Framework and Reform Strategy for Fisheries and Aquaculture in Africa in order to diversify and enhance sustainable fishing dependent livelihoods.

Introduction and background

Governance, regulation, and policing of (game and) fisheries is a topical issue in Southern Africa, more so for modern-day Zimbabwe (then Southern Rhodesia prior to 1980) (SADC, 2016). The fisheries and aquatic sector in the Southern African Development Community (SADC) countries, mainly comprising marine and inland capture fisheries, crocodile ranching, and aquaculture, generate a variety of benefits (SADC, 2008). Some of the benefits include nutrition and food security, sustaining livelihoods, creating employment, exports, and generating foreign currency, and conservation and biodiversity values that are of global significance (SADC, 2016). Different narratives have been proffered on the control and regulation of game and fishing with divergent views (Wolmer, 2005). For instance, Mutwira (1989) asserted that wildlife policy throughout Southern Rhodesia from 1890 to 1953 allowed some form of ‘mass slaughter’ under different reasons. Mutwira (1989) and Wolmer (2005) cited instances of ‘mass slaughter’ of wild dogs between 1906 and 1912 as a rabies preventative measure by white colonial settlers to avoid livestock infection. Further, ‘mass slaughters’ of wildlife such as African lions (Panthera leo), leopards (Panthera pardus), hyenas (Crocuta crocuta and Parahyaena brunnea), and cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus), which were considered as vermin, were noted as mass exterminations of wildlife using flaws in the existing wildlife policy in that period (Wolmer, 2005). Mutwira (1989) and Wolmer (2005) focused heavily on the negative impacts of colonial policy. However, Mutwira (1989) and Wolmer (2005) left a gap on the negatives and positives of the different pieces of game and fisheries conservation legislation which were successively introduced from 1890, when the British settlers arrived. This review aims to provide a more balanced analysis of the legislative evolution, its drivers, and unintended consequences for the fisheries, aquaculture, and crocodile ranching sectors.

Historically, the regulation of game and fishing was the prerogative of different kingdoms and chieftainships, who used different native laws, also termed “indigenous conservation practices,” driven by the collective access principle (Chibememe et al., 2014a, b). For most of the kingdoms and chieftainships, the onus was on conserving game and fish through various punitive, coercive, and persuasive methods bordering on taboos, totemism, cultural and religious beliefs, myths, sacred realms, and outright outlawing of wanton killing and hunting of game and unregulated fishing (Child, 1995; Chibememe, 2014c). There was a combined effect of low human population and abundant game and relatively pristine aquatic systems, which resulted in sustained game hunting and fishing underpinned by respective cultural norms in the local communities at that time (Child, 1995, 2009). The extent of the destructive nature and effects of hunting and fishing technologies in that era is rather anecdotal in context (Mashapa, 2018). Regardless, some of the laws or regulations included specified (temporal) non-hunting, cultivating, and fishing seasons or periods (Child, 1995; Mashapa, 2018; Mashapa et al., 2019).

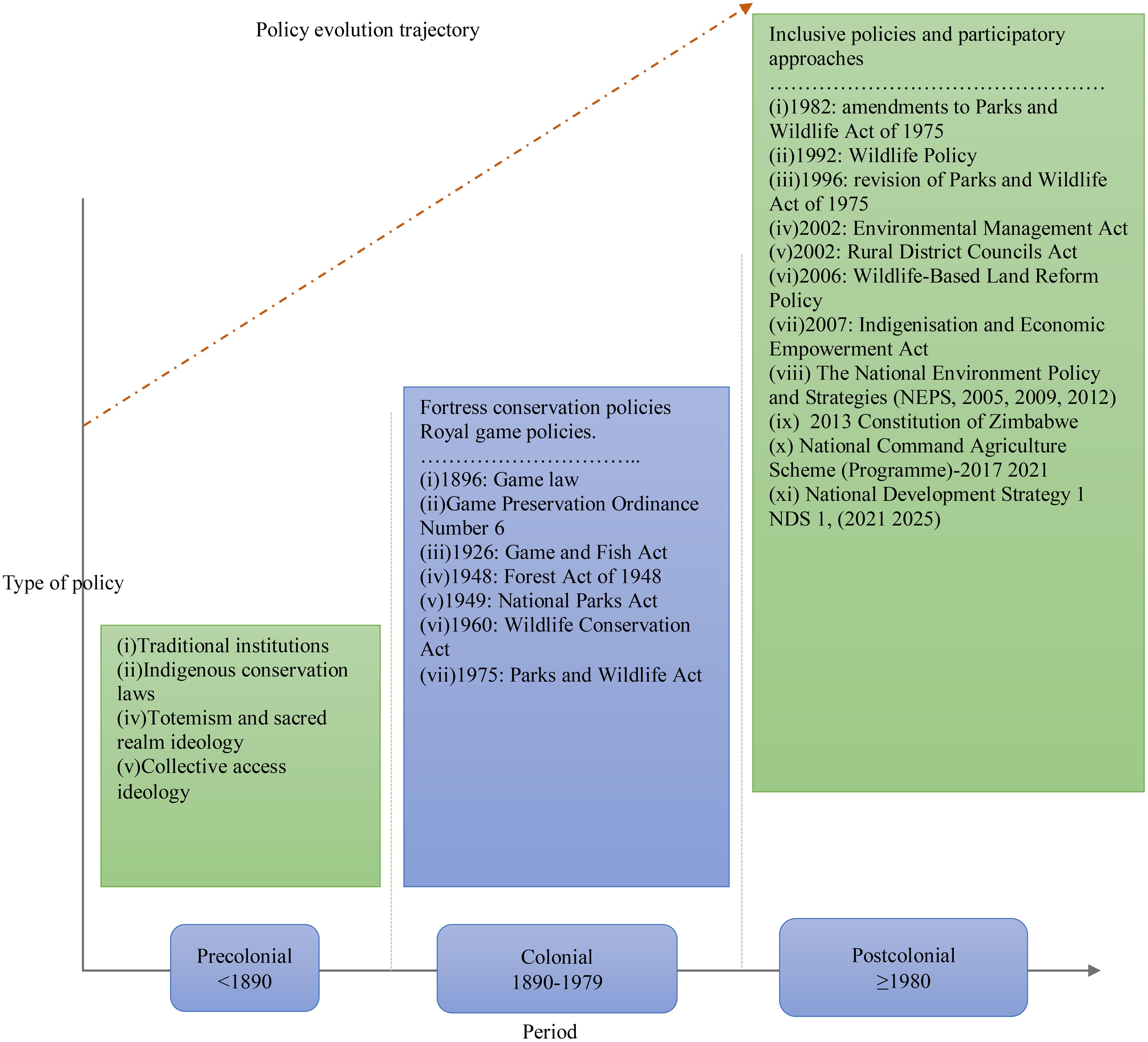

Muposhi et al. (2016) and more recently Gandiwa et al. (2021) aptly summed up the wildlife conservation conundrum by indicating that as with most African countries, Zimbabwe’s wildlife conservation landscape has evolved following three main highlighted (but grouped) phases, that is, precolonial (before 1890), colonial (1890–1979), and postcolonial (1980 to date). A diagrammatic depiction is indicated in Figure 1, adapted from Muposhi et al. (2016), originally developed for wildlife conservation (Wildlife Based Land Reform Policy, 2006), which this paper will now apply and refine for the aquatic sector. The pre-colonial wildlife conservation practices were regulated by traditional institutions using indigenous ‘soft conservation’ paradigms (Mashapa et al., 2019). The colonial wildlife conservation practices were driven by highly political and segregatory conservation practices that resulted in the displacement of indigenous people from their land to pave the way for so-called “wildlife protected areas,” which were devoid of human settlements, and the conservation and regulation of wildlife through the ‘fine and fortress’ principles (Gandiwa et al., 2021). Finally, the post-colonial period (independence phase) consisted of inclusive wildlife conservation practices encompassing the participatory approach through co-management of wildlife in some instances, for example, CAMPFIRE, that is, the Communal Areas Management Program for Indigenous Resources (Sibanda, 1996). After examining key environmental legislation with huge connotations for wildlife in Zimbabwe, we have added in the adapted Figure 1 by Muposhi et al. (2016) and the National Environmental Policy and Strategies (NEPS, 2005, 2009, 2012). These National Environmental Policies and Strategies mainly focused on all environmental aspects, with the overall thrust being to “avoid irreversible environmental damage, maintain essential environmental processes, and preserve the broad spectrum of biological diversity so as to sustain the long-term ability of natural resources to meet the basic needs of people, enhance food security, reduce poverty, and improve the general standard of living of Zimbabweans”. The policies were rather socioeconomic in outlook, as they placed key emphasis on sustainable utilisation and maintenance of the integrity of the environment with equitable public access for poverty alleviation (Government of the Republic of Zimbabwe, 2005, 2009, 2012; Macheka, 2021). Moreover, the policies glossed over key issues, and the guiding principle and strategic directions sections reiterated issues that were already covered in the various historical Parks and Wildlife Acts.

Figure 1. Adapted policy-evolution framework for Zimbabwe (pre-colonial to post-colonial). Original framework developed for terrestrial wildlife conservation by Muposhi et al. (2016); here the diagram is revised and applied to aquatic sectors (capture fisheries, crocodile ranching, and aquaculture) to highlight where existing frameworks omit sector-specific legal and institutional transitions.

In as much as the colonial wildlife conservation phase recognised the significance of fishes, they were treated similarly to game and not as a stand-alone entity in Zimbabwe (Malasha, 2002). Even after the creation of protected areas (which was done specifically for game, and fisheries were an afterthought), there were feeble attempts to zone and breed fish (aquaculture) and crocodiles (ranching) in Zimbabwe. The wildlife authorities created the Lake Kariba Fisheries Research Institute (LKFRI), the Nyanga Trout Research Centre, the Lake McIlwaine Fisheries Research Station, and the Lake Sebakwe Fisheries Research Station. They also created Lake Mutirikwi/Kyle Fisheries Station, the Bulawayo Branch of Aquatic Ecology, and Matopo National Parks (under the Branch of Aquatic Ecology), and through the Department of Research and Specialist Services (DRSS), fisheries research is ongoing at the Henderson Research Station (Fish Section) and Makoholi Research Station in Mazowe and Masvingo, respectively (Mudzengi et al., 2021). These stations were all created for the purposes of undertaking fisheries research and not necessarily aquaculture-related research. In most cases, the stations were monitoring fish resources in the lakes and engaged in limited aquaculture research, like in the case of LKFRI and Nyanga Trout Research Centre, which were monitoring the growth of the introduced and non-native clupeid kapenta (Limnothrissa miodon) and salmonids, that is, rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and brown trout (Salmo trutta), respectively (Malasha, 2002). Crocodile monitoring was not the main focus for all these stations (Malasha, 2002). Crocodile ranching, which refers to the removal from the wild of juveniles or eggs of crocodiles, which are then transferred to controlled raising facilities, where the wild-caught specimens are grown for commercial purposes, was designated by law through the Parks and Wildlife (Hunting of Crocodiles and Removal of Crocodiles’ Eggs) Notice, 1975 (S.I. No. 969 of 1975). Before, collection of crocodile eggs was treated as a hobby, trophy collection, and for research purposes under the Fish Conservation Ordinance of 1955 (Government of the Republic of Zimbabwe, 1975).

There is adequate documentation of the evolution of game conservation policy from the precolonial phase (before 1890), the colonial phase (1890–1980), and in modern-day Zimbabwe (Murombedzi, 2003a, b; Muboko and Murindagomo, 2014), with less emphasis on examining the regulations governing the operation of fisheries, crocodile ranching, and aquaculture ventures in Zimbabwe (Mudzengi et al., 2021). Conflation of game and fisheries laws has led to jurisdictional and operational mismanagement, inaction, and decision paralysis when it comes to further disentangling the nuances in capture fisheries, crocodile ranching, and aquaculture regulations in Zimbabwe like any other country in the world (Malasha, 2002; Mudzengi et al., 2021). This necessitates concerted efforts to examine, explore, and highlight the management gaps and strengths in order to consolidate and create solid fisheries, crocodile ranching, and aquaculture policies. Nevertheless, a mere focus on the gaps in policy implementation and practice is a less useful intervention without questioning the existence of the policies and regulations whose implementation is often caught up in a web of political interactions as diverse stakeholders seek to maximise the use of natural resources with negative repercussions on the environment (Macheka, 2021).

Policy analysis theory

Policy analysis is an applied social science discipline that uses multiple methods of inquiry and arguments to produce and transform policy-relevant information that may be utilised in socioeconomic political settings to resolve policy problems. Policy analysis is research-informed advice to clients (Cairney, 2023). Some is ex ante policy analysis, focusing on identifying problems, generating solutions, comparing their likely effects, and making recommendations (Cairney, 2023). Some is ex post, focusing on the monitoring or evaluation of policy. Both are applied analyses, focusing on what is and ought to be. Analysis is usually performed by individuals or organisations commissioned by policymakers. Most texts help analysts to develop the skills and strategies to maximise their influence on policy and policymakers (Cairney, 2023). Policy analysis focuses on decision-making and policy formulation, often using statistical methods, whereas political public policy theorists are more interested in the results of public policy (Cairney, 2023). Many parts of Africa have had low economic growth and inefficient performance of national industrial fisheries and fish fleets (FAO, 2020). Artisanal and inland fisheries management and aquaculture development are constrained by weak institutions, lack of good governance, solid policies, and a deteriorating aquatic environment (FAO, 2020). This requires policies that deals with fisheries governance and management, access to information and resources, markets, and capital (FAO, 2020). Aquacultural-related policies need to be developed relating to the establishment of an enabling environment, roles of government, sectoral integration, and demographics and resource use (Mabika and Utete, 2024). This paper is a scoping review of the evolutionary trajectory of the fisheries, aquaculture, and crocodile game ranching policies in Zimbabwe within the context of Southern Africa.

Brief review of SADC member states’ fisheries policies

The overall aim of the current SADC’s fisheries development programme is to promote and expand fish production to attain regional self-sufficiency, increase supplies of animal protein by reducing post-harvest losses, and create employment to increase income (SADC, 2016). The goal is to increase the standard of living of peoples of the region (SADC, 2016). The three-point SADC Programme of Action states that: (i) fish is a natural resource that has great importance for the production of good quality protein, (ii) management and utilization of fish resources aim at maximizing sustainable yield from natural waters, and (iii) self-sufficiency will be attained by increased productivity of marine and inland fisheries through improved techniques, integration of aquaculture with agriculture and other rural development programmes, wherever socially and economically feasible, utilization of under-exploited species, and improvement of fish processing, distribution, and marketing for local and export demands (SADC, 2016). The overall aims of fisheries development programmes are valid also for marine and brackish water aquaculture (FAO, 2022).

SADC’s fishery policy statements reflect the fisheries policies of member countries (FAO, 2022). In Southern Africa (SADC), the evolution of fisheries and aquaculture policies has been more rapid for countries with both coastal (marine) and inland freshwater resources, such as Namibia, Madagascar, Cape Verde, Seychelles, the Comoros Islands, Mauritius, South Africa, and Tanzania. Armed conflicts have slowed (or are slowing) down the evolutionary pace and trajectory and operationalisation of fisheries and aquaculture policies in countries like Angola, Mozambique, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. For landlocked countries like Botswana, the Kingdom of Eswatini, Lesotho, and Zimbabwe, with the exception of Malawi, aquaculture is still a fledgling industry; thus, development of the relevant consolidated aquaculture and fisheries governing policies is still in its infancy (FAO, 2022).

For Botswana, there is no current national fisheries and aquaculture policy. As such, the regulation and governance of fisheries has been administered through various sections in policy documents such as the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan of 2016, Botswana Development Plan of 2016, Vision 2036: Achieving Prosperity for All in 2016, Botswana National Climate Change Action of 2018, and National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan of 2020. Specifically, the policy documents and Acts regulating the fisheries sector include the Diseases of Animals Act of 1977, Wildlife Conservation and Parks (Amendment Act, 2023, and the Fish Protection Regulations, 2016 (SI no. 16 of 2016). The policy documents evolved in tandem with the SADC Policy on Fisheries of 2001, 2002, and 2016, though aquaculture has only recently been formally recognised as part of fisheries. Internally, the evolution of the aquaculture and fisheries policy, until recently, has been overshadowed by a shifted focus and prioritisation on water-related policies in response to climate change-induced droughts in Botswana. In Angola, the civil war that raged on from 1975 to 2002 disrupted the development of fisheries governance and regulations. As a result, the current fisheries policies include the Presidential Decree No. 276/22 approving the National Plan for the Promotion of Fisheries (PLANAPESCAS), 2022; Law No. 6-A/04 on Aquatic Biological Resources (New Fishing Act) of 2005; Decree No. 40/06 on Hygienic and Sanitary Measures for Fisheries and Aquaculture Products, 2006; and Decree No. 41/05 establishing the General Regulation on Fisheries for 2005. As it is, there is a huge gap in the study of the fisheries policy evolution for Angola (FAO, 2024). For Lesotho, a landlocked nation, there is a huge gap in the evolution of fisheries policies. The main policies and Acts governing fisheries were developed in 1951, and they include the Protection of Freshwater Fish Proclamation. (No. 45 of 1951), and the Fresh Water Fish Regulations (No. 112 of 1951). This is the same context for the Kingdom of Eswatini, where the current policies and Acts governing fisheries and aquaculture, which include the Protection of Freshwater Fish Act, 1937, and Freshwater Fish Regulations 1951, also focussed more on the conservation of water resources rather than the development of fisheries and aquaculture. Malawi, a landlocked country, has a relatively well-developed fisheries and aquaculture industry. Consequently, the country has consistently developed and amended fisheries and aquaculture policies. Some standout fisheries policies include the Fisheries Conservation and Management Act, 1997 (Cap. 66:05). This Act makes provision for the regulation, conservation, and management of the fisheries of Malawi and for matters incidental thereto or connected therewith. The National Fisheries and Aquaculture Policy (NFAP) (2016–2021) is a five-year nationwide sectoral document that revises the National Fisheries and Aquaculture Policy of 2001 with the aim of addressing critical issues affecting fisheries and aquaculture development in Malawi, such as the need for strengthening monitoring and evaluation as well as the utilization of Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs).

For Madagascar, Mauritius, Seychelles, Mozambique, and Namibia, the current fisheries policies are a product of constant evolution and amendments in line with changes in the international marine and inland fisheries policies. For instance, Mauritius recently developed the Fisheries Act of 2023, which regulates the governance of marine and inland fisheries with a strong emphasis on aquaculture to preserve fish biodiversity whilst mitigating overexploitation in the wild capture fisheries. Zambia has a relatively well-developed fisheries sector, and consequently policies and Acts have been consistently developed and amended to regulate the governance and operations of the fisheries and aquaculture sectors. Zambia recently, in 2023, developed the National Fisheries and Aquaculture Policy formally regulating the governance of fisheries and aquaculture sectors. South Africa, in the SADC, along with Seychelles and Cape Verde, has consistently developed and amended fisheries and aquaculture policies and Acts in tandem with changes in international marine and freshwater fisheries and aquaculture policies. The evolutionary trajectory of the fisheries policies has been consistent; however, the consolidation of aquaculture policy development in SADC was cemented by the adoption of the Aquaculture (Licensing) Regulations: Aquaculture Act, 2002 (G.N. No. 245 of 2003) by most of the member states except for Lesotho, the Kingdom of Eswatini, and Zimbabwe, the three countries that barely recognised aquaculture as a livelihood-sustaining component of the fisheries sector until recently.

A review of national policies and plans (published and unpublished) for SADC member states reveals a number of highlights. First, among SADC member states, the importance of fish as food is increasingly being recognised, even in countries where fish is not a major component of the diet, and its contribution to food security is highlighted (SADC, 2016). Most governments do not, however, have an explicit development policy or plans for fisheries and aquaculture (FAO, 2022). Where policy statements exist, they are, mostly, linked to agriculture (Mabika and Utete, 2024). Policy statements often refer to fish as a provider of “cheap” protein as a source of jobs and of foreign exchange earnings, the latter especially for marine fisheries (FAO, 2024). Within the context of SADC, the broad phases of wildlife policy are known, but the specific, nuanced evolution of fisheries, crocodile, and aquaculture policy within these phases remains underexplored, especially for landlocked countries like Zimbabwe (FAO, 2024). The links between national policies and plans and programmes actually implemented are not well established (Mabika and Utete, 2024). There is a general need to harmonize policies, plans, programmes/projects and other interventions (FAO, 2022). To ensure sustainability of aquaculture development, the close links with policies and plans for the agriculture sector need to be strengthened (Mabika and Utete, 2024). The potential roles of the private sector and of NGOs are not recognised or elaborated in policy statements and development plans (Mudzengi et al., 2021; Mabika and Utete, 2024). Consequently, mechanisms for consultation with “target groups” are not sufficiently established (Mudzengi et al., 2021).

Objectives and aims

This scoping review outlined and examined the evolutionary pathway of primordial and contemporary legislation and policy governing the management of capture fisheries, crocodile farming, and aquaculture firms in Zimbabwe. The aim was (i) to identify the legal and policy frameworks for capture fisheries, crocodile farming, and aquaculture in Southern Africa and Zimbabwe (ii) to explore the evolution and gaps in the legislation and policies for capture fisheries, crocodile farming, and aquaculture in Southern Africa and Zimbabwe; and (iii) highlight the strengths and future dimensions for developing prudent management policies for fisheries, crocodile ranching, and aquaculture in Zimbabwe.

Materials and methods

Data collection

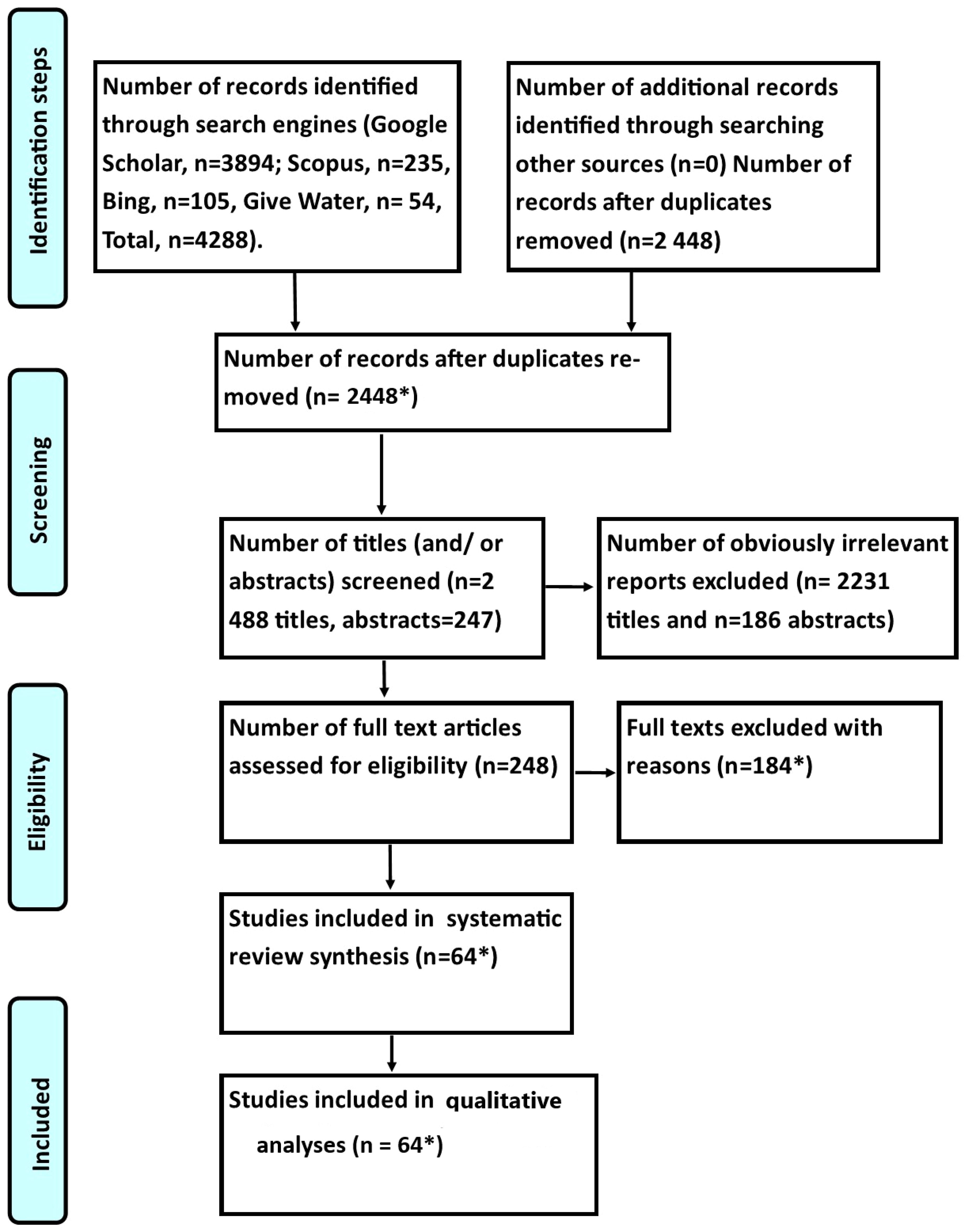

This scoping review followed the protocol of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) methods; thus, this manuscript was compiled with the PRISMA-ScR checklist (Abrams et al., 2020). The study applied a directional scoping review method detailing the historical evolutionary pathway of policing of fisheries, crocodile ranching, and aquaculture in Zimbabwe for the period 1890-2021, with a comparative context of the current SADC (member states) fisheries and aquaculture policies and frameworks from rigorous analysis and examination of existing literature following the PRISMA 2020 literature review methods by Page et al. (2021) and Gough et al. (2012). The initial point was formulating the research question: what were (and are) the conservation policies regulating the management of the capture fisheries, crocodile ranching, and aquaculture sectors in Zimbabwe? Afterwards, a protocol similar to the PRISMA 2020 literature search framework was generated, and a scoping selection of online and hard copy evidence encompassing relevant information on fisheries policies, technical reports on fisheries, crocodile ranching, and protocols on aquaculture and fisheries management in SADC member states, with a case study on Zimbabwe, was carried out. For research articles, fisheries policies, and technical reports, the titles and abstracts were screened for relevance. After identifying the relevant documents, full texts were obtained and screened to identify policy and legal documents and contents relating to the regulation. Examination of results, data extraction, contextual synthesis, and dissemination were later done. The section below summarises each of the steps carried out for the research.

Document selection

After situating the study in the formulated main research question, the first exploratory scoping and searches of relevant literature were done in Google Scholar, Scopus, Bing, GiveWater, and the Boolean search engines. This is because most water, aquatic, fisheries and crocodile ranching information for SADC and Zimbabwe of scholarly credibility, validity, and reliability was easily and directly available at no cost in these search engines. We aimed to collect documented holistic and historical policies, regulations, and Acts governing the management of capture fisheries, crocodile ranching, and aquaculture in Rhodesia and Zimbabwe. The grey literature sources of Bing and GiveWater were used, considering the evidence of unindexed sources of literature in fisheries policies for Zimbabwe.

Gray/grey literature, or evidence not published in commercial or indexed publications, can make important contributions to a systematic review (Paez, 2017). This grey literature can include academic papers, including theses and dissertations, research and committee reports, government reports, Acts of Parliament, conference papers, and ongoing research, among others (Paez, 2017). It may provide data not found within commercially published or indexed literature, providing an important forum for disseminating studies with null or negative results that might not otherwise be disseminated (Paez, 2017). Gray literature may thus reduce publication bias, increase reviews’ comprehensiveness and timeliness, and foster a balanced picture of available evidence (Paez, 2017). Grey literature’s diverse formats and audiences can present a significant challenge in a systematic search for evidence (Paez, 2017). However, the benefits of including grey literature may far outweigh the cost in time and resources needed to search for it, and it is important for it to be included in a systematic review or review of evidence, especially in areas where there is a paucity of data (Paez, 2017).

Paper tracking was done in Excel—the author did independent extraction for each data set/search engine. We traced fisheries, aquaculture, and crocodile ranching Acts through amendments and statutory instruments (Sis) by examining consolidated versions, dates of enactment versus amendments, and cross-checking with official gazettes/archives available from the Government of Zimbabwe records. Vague areas were mediated by an independent expert via discussion. Extraction was a narrative review of any piece of legislation that discussed, described, or delineated the scope of fisheries policy; thus, any definitions for fisheries legislation were extracted verbatim, as were all references to fishery’s scope of practice (Abrams et al., 2020). Hard copy evidence for technical reports, Acts and policies, with legislative provisions and information on the management plans for crocodiles and governance of the operations and management of fish farms, wild capture fisheries, and crocodile farms in SADC member states with a special focus on Zimbabwe as indicated in the objectives, were sourced from relevant institutions. The main documents were obtained from directly involved institutions like the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Authority, National Archives of Zimbabwe, National Museums and Monuments of Zimbabwe, Zimbabwe Fish Producers Association, Crocodile Farmers Association of Zimbabwe, and the Parliament of Zimbabwe and relevant line ministries in the Government of Zimbabwe.

Defining the search strategy

For item and document selection, the keyword search methods were used in the same search engines above. The search was limited to the title, abstract text, and keywords. The study explicitly searched for Acts, legislation, and policies and studies focusing on key terms: ‘‘fisheries, fish farming, aquaculture, crocodile ranching, crocodile farming in Rhodesia and Zimbabwe’’. Further searches for fish farming in all coupled (using AND, NOT, OR) subgroups which comprised: “fisheries-policy,” “water resources conservation-aquaculture,” “fisheries-management,” “aquaculture-policy,” “aquatic resources-human activities,” and fisheries researches including “fisheries-plans,” “fisheries-regulations,” “fisheries-legislation,” “fish farming-human management,” “fishing sector-legislation,” and “crocodile farming-regulations,” “crocodile ranching-regulation,” “crocodile ranching-policy,” “crocodile ranching-management plans’ together with technical reports on ‘‘human interventions in fisheries and crocodile ranching in Southern/Rhodesia and Zimbabwe”. Some of the coupled terms, for example, “fisheries-human activity,” “fisheries-plans,” and ‘‘water resources conservation-aquaculture’’ produced a lot of background noise and conjoined other non-relevant information for the study. Further search did not lead to discovery of additional terms that relate to fisheries, aquaculture and crocodile farming legislation and policies in Southern/Rhodesia and Zimbabwe. The final search terms used were as follows: (((fisheries, fishing, fish farming, aquaculture, crocodile ranching, crocodile farming, AND (“regulations, management, policies in Southern/Rhodesia and Zimbabwe *”).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

From an initial list of 4,288 articles obtained with the search engines (Google Scholar = 3,894; Scopus = 235; Bing = 105; GiveWater = 54), after cleanup as indicated in the flow diagram (Figure 2), only 64 items were eventually included in the final analysis. The keywords in the abstracts, as well as the abstract text, were screened for relevant items which could be classified or mentioned policies, Acts, governance, management, and regulations on fisheries, crocodile ranching/farming, and fish farming or aquaculture in Southern Rhodesia and Zimbabwe from 1890 to 2021. The aim was to screen the data set to manageable and relevant sizes. An article was included if it met the following criteria: (a). An Act or policy document on fisheries, crocodile ranching, and aquaculture, and (b) it was published in a reputable journal, international organisation technical report, or book, and (c) relevant government and non-governmental conference proceedings on capture fisheries, crocodile farming, and aquaculture regulatory frameworks and reviews. The flow diagram in Figure 2 summarises the steps adopted after the PRISMA 2020 method and outlines the steps taken to include and exclude the obtained information from the used search engines. The review excluded media reports, as they are not peer reviewed to be valid and reliable, except when they were the only credible source for a vital development in the regulation of fisheries, crocodile ranching, and aquaculture in Zimbabwe.

Data extraction and variables analysed

The key variables extracted from the selected documents (government gazettes, historical periods, fisheries policies, peer-reviewed journals, technical reports, management plans) were coded into the main themes, which comprised fisheries and wildlife Acts, fishing, fisheries and aquaculture regulations, wildlife legislation, policies and governance, statutory instruments, wildlife institutions, fisheries conservation, SADC fisheries and aquaculture policies, natural resources management, and crocodile management plans. The main variables extracted from the main themes which formed the basis for this scoping review included capture fisheries, recreational angling, fisheries research and aquaculture, fish farming, crocodile farming, crocodile ranching, SADC fishing legislation, policy and regulations, and institutional mandates and roles.

Results and discussion

In this section, the development and evolution trajectory of fisheries and aquaculture policies for Southern African (SADC) countries is discussed. The comprehensive list of Acts and policies that were reviewed has been added as Supplementary data (Supplementary Material S1). Subsequently, the evolutionary pathway of the fisheries and aquaculture policies in Zimbabwe is discussed as a case study.

Evolution of the fisheries and aquaculture policies in Southern Africa

Realising the value, and in an endeavour to optimise benefits from the fisheries and aquaculture sector, SADC Heads of State in 2001 endorsed the SADC Protocol on Fisheries that aimed to promote responsible and sustainable use of the living aquatic resources and aquatic ecosystems of interest to State Parties (SADC, 2001, 2016). The SADC 2001 Protocol on Fisheries was adapted, and in context it borrowed heavily from previous African and international protocols on inland fisheries, including the deliberations of the Committee for Inland Fisheries for Africa (CIFA/84/6, CIFA/85/7, CIFA/85/8, and CIFA/94/9) drafted in 1983, 1984, 1985, and 1994, respectively, that stressed the need to safeguard and protect inland fisheries and fund the development of aquaculture for sustainable livelihoods in Southern Africa (FAO, 2020). The resolutions of the regional CIFA meetings, together with those of the continental African Committee of Fisheries (COFI), resonated with the international resolutions of the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), the World Trade Organisation, and related fora on sustainable trade in fish and fish products (FAO, 2020).

From 1973 to 2020 the FAO’s emphasis has been to decongest and minimise exploitation of inland wild capture fisheries with a shift towards aquaculture in African countries and, on a global scale, due to concerns of wild fish stock overexploitation, biodiversity loss, and pollution in aquatic systems (FAO, 2020). This FAO thrust led to the amendment of the 2001 SADC Protocol on Fisheries by the SADC to develop the 2008 and 2016 SADC Protocols on Fisheries (with input based on the New Partners for Africa Development (NEPAD) Fishery and Aquaculture Action Plan (NEPAD, 2005; AUC-NEPAD, 2014). Both the 2008 and 2016 SADC Protocols on fisheries aimed to harmonise regulations and policies governing the management of aquaculture, fisheries, and aquatic resources in Southern Africa. In 2015, the SADC Fisheries Programme (2015–2020), which aims to (i) increase fish production in the region and (ii) safeguard sustainable fish production from aquaculture or fish farming, was adopted to harmonise and incorporate regional policies and regulations on aquaculture.

Appendix 2 summarises the key policies, focus areas, and the percentage of development and coverage of aquaculture, capture fisheries, and crocodile ranching in SADC countries. For coastal/marine (MC) countries there is a skewed lopsided, concerted development of pro-marine policies and strategies currently modelled along the Blue Economy Strategy. SADC states with coastal resources tend to neglect inland aquaculture activities, or rather, policies for inland aquaculture the development lag behind those for marine capture fisheries. There is a poor or negligible consideration of policies towards development of crocodile ranching across the SADC region. Out of necessity to ensure sustainable livelihoods, landlocked countries have highly developed aquaculture policies, with Zimbabwe and South Africa having solid crocodile ranching strategies and plans relative to the rest of the SADC countries (Appendix 2). The main policy challenges relate to the lack of technical capacity, historical colonial systemic exclusion, and elitist-driven and dominated recreational inland angling and marine capture fisheries. Poor resource allocation and armed conflicts in some SADC countries, for example, Mozambique, Angola, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, have affected the development of inland and even coastal aquaculture and capture fisheries and deterred drafting of tangible policies on crocodile ranching. Institutional overlaps and obfuscated roles are clear across most SADC countries, where agriculture, water, and environmental affairs monitoring departments often overlap, intersect, and conflict over the jurisdiction on aquaculture and fisheries resources.

Currently, individual SADC member states, for example, Zimbabwe has developed or is in the process of developing fisheries and/or aquaculture plans or policies in harmony with the 2016 SADC Protocol on Fisheries and the SADC Fisheries Programme with relative successes (SADC, 2015; FAO, 2020). The fact that most SADC member states are constantly reviewing their fisheries and aquaculture policies and plans indicates that governance and management of the aquatic resources and systems are dynamic and correspond to stochasticity in international and regional fisheries and aquaculture protocols (FAO, 2020). In Zimbabwe, like most Southern African countries, aquaculture faces a complex dilemma as the wildlife authorities and other various government agencies and non-governmental organisations have divergent views on the regulations governing the sector (Mabika and Utete, 2024). The recently developed but yet to be enacted Zimbabwe Fisheries and Aquaculture Bill is still being aligned to the SADC Fisheries Policy in line with the Policy Framework and Reform Strategy for Aquaculture in Africa.

Evolutionary pathway of fisheries and aquaculture acts and policies case of Zimbabwe

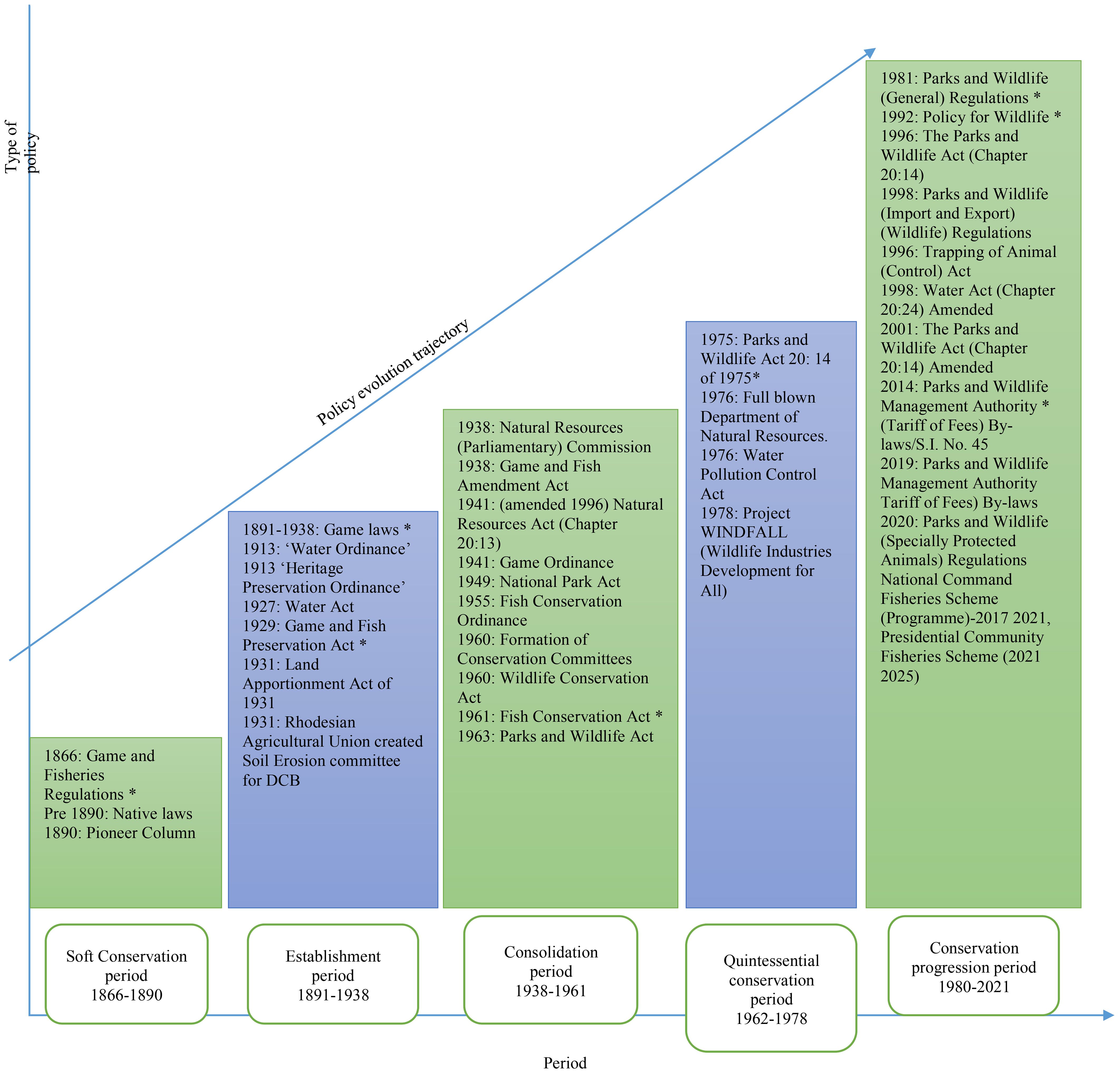

After thorough screening, a total of 49 items were used to reflect the breadth of the context citing crocodile ranching, capture fisheries and aquaculture regulations and policies and the responsible institutions in Zimbabwe in context to Southern Africa. The study classified and summarised existing pre-colonial, colonial and post-colonial conservation legislation and the related institutional frameworks as adapted and modified from Chibememe et al. (2014a). These form the basis for the review and are indicated in Appendix 1. The main phases of fisheries policy evolution follow a rather unclear pattern that has been denoted into rudimentary periods indicated in Figure 3 after the modification of the conservation policy evolution pathway in Figure 1 by Muposhi et al. (2016).

Figure 3. Framework indicating the stand-out acts for capture fisheries, crocodile ranching, and aquaculture conservation in Zimbabwe. * Marks the highlight acts for each period.

“Soft conservation period: pre 1890”

Game and fisheries were managed through Native Laws under different kingdoms and chieftainships in the period prior to 1890 (Chibememe et al., 2014a, b). In this period, the emphasis was on the collective access of game and fish for all community members in a sustainable manner (Chibememe et al., 2014a, b). The different native laws termed ‘indigenous conservation practices’ or ‘traditional informal institutions’ were underlined by conserving game and fish using punitive, coercive, and persuasive methods anchored on recreation, restraint, societal norms, taboos, totemism, cultural and religious beliefs, myths, sacred realm, and outright outlawing of wanton killing and hunting of game and unregulated fishing (Child, 1995). The relative success of these native laws rather owes to the non-destructive hunting and fishing technologies used, the abundance of game and fish, and the low human population in the period (Colchester, 2004).

Nile crocodiles (Crocodylus niloticus) were feared and revered (and used or abused) for their mystical powers of subjugation and predation in rituals, cultural practices, and even witchcraft in some cases, at the same time under native laws in the country (McGregor, 2005). Once the Pioneer Column of Cecil John Rhodes reached modern-day Zimbabwe in 1890, they started implementing some sections of the United Kingdom Game and Fisheries Regulations of 1866. In these statutes, the emphasis on fisheries and game regulations in all British colonies was premised on managing fisheries based on game laws (Murombedzi, 2003a). The same regulations governing game were transferred to fisheries management, and there was no attempt to even regulate crocodile populations. Crocodiles were regarded as vermin or pests to be exterminated in rivers and wetlands (Blake, 1982; Child, 1987; Mutwira, 1989; McGregor, 2005). The highlight of this period is that both ‘traditional informal institutions’ and a formal institution were regulating the management of fisheries with no mention of crocodile ranching, and aquaculture in the legislation.

“Establishment period: 1891–1938”

The Games Laws from 1891 to 1938 which analogously regulated game and the fisheries (wild capture fisheries) sector in Zimbabwe, in this review, are considered the establishment period. In the period 1891–1931 a raft of laws pertaining to water and land resources, for example, the Water Ordinance of 1913, the Water Act of 1927, and the highly contentious 1931 Land Apportionment Act (Appendix 1) were drafted and implemented in Southern Rhodesia (Murombedzi, 2003a). The key threads in these laws were the conservation of water and land resources particularly, veld for livestock. There was a side-track piece of legislation, that is, Game and Fish Preservation Act of 1929. The Act mainly aimed at gazetting and proscribing fishing methods, for example, use of drag, cast, stake, explosives, and dynamites, or other nets, and determined that any undersized fish shall be returned to the water (Malasha, 2002). The act also prohibited fishing without a license. The requirement for a fishing license marginalised already impoverished native Africans, as the cost of purchasing one was high and unaffordable for a majority of them. The Game and Fish Preservation Act of 1929 mainly centred on the preservation of hunted specimens of game, for example, trophy and skin curing, and post-harvest fish handling and preservation rather than on the actual conservation practices.

Nevertheless, the Games Laws from 1891 to 1938 were silent on crocodile conservation. Examination of its provisions also indicated that the analogy between game and fish is flawed, as game movement, behaviour, population trends, slow breeding rate, and migration can be traced and documented, resulting in corrective conservation measures being implemented (Malasha, 2002). Contrastingly, fish stock assessment tends to be scientific and indirect at best and must be done expeditiously as fish breeding rates are faster. The Nile crocodiles were considered as part of game or reptiles, for example, snakes and lizards, and were to be conserved in such a context rather than as part of aquatic or water resources. The net effect was disgruntlement among elite white settlers with vested interests in water resources, particularly recreational fish angling and small-scale crocodile ranching and crocodile egg collection.

“Consolidation fisheries and crocodile conservation period: 1938–1963”

In 1938, the Game and Fish Preservation Act of 1929 was renamed the Game and Fish Amendment Act. A section on fish was included to the Games Law, and hunting restrictions applying to game were transferred to capture fisheries, that is, sport and netting and any other form of fishing. Licenses and permits were introduced for any form of fishing, even for sport fishing, as a form of conservation with restrictions on the rod and line efficiency and catch limits and only for specific species, for example, largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides), tiger fish (Hydrocynus vittatus), and trout (Malasha, 2002). These amendments were a result of strong pressure exerted on government by elitist associations with an interest in angling sport and fly-fishing that wanted direct government funding for their activities (Toots, 1970). The powerful angling associations had financial muscles and were politically connected and constituted part of the elite ruling class in any case, such that they lobbied the government of that time to amend the Games Laws to include a stand-alone section on fisheries. For instance, institutions such as the Flyfishers Association of Southern Rhodesia lobbied government to provide financial assistance to fish angling clubs that wished to import exotic fish species, mainly trout and bass for recreational angling from outside the country (Toots, 1970). The angling societies of that time also asked for more powers to control the manner in which the exotic fish species were stocked and harvested (Bell-Cross and Minshull, 1988). As an indication of their influence and power, between 1936 and 1946, a total of seventy-three (73) government notices were made in relation to the Game and Fish Preservation Act of 1929. Most of these notices were to authorise the Rhodesia Angling Society and the Trout Acclimatisation Society to introduce alien fish into the waters of the colony and also to ban fishing for a period of 5 years to allow the introduced species to expand (Toots, 1970; Bell-Cross and Minshull, 1988). This was effected regardless of the protestations of fish conservationists over the unforeseen impacts of introducing alien exotic invasive fish species on the indigenous and endemic fish species and overall aquatic biodiversity of rivers and lakes in Southern Rhodesia (Toots, 1970; Bell-Cross and Minshull, 1988).

As a show of force, in 1944, the Southern Rhodesia National Anglers Association was formed. In fact, by 1947 similar associations had become so politically entrenched that they began to lobby government to amend the Game and Fisheries Act to give more responsibilities on the management of water bodies to its members. These amendments were made towards the end of 1947 when the Act made members of the Angling Societies into Honorary Fish Wardens. The wardens had powers to regulate, prohibit fishing and apprehend those doing so in water-bodies located on private property which were mostly owned by the elite white ruling class (Toots, 1970; Malasha, 2002). In this period, the ‘fine the offender’ approach was used on those caught illegally fishing in restricted areas and the fines ranged between 5 and 20 Rhodesian pounds (Malasha, 2002). It is prudent to indicate that the ‘fine the offender’ approach has been in effect ever since that time even for modern game and fisheries regulations in Zimbabwe (Muboko and Murindagomo, 2014; Mudzengi et al., 2021). The prominent role of the affluent, predominantly, recreational angling societies in influencing fisheries policy development and implementation forms a part of the ex-ante policy analysis driven by the elite in a society. It serves to dissuade policy formulation processes to be elitist (Chibememe et al., 2014a), as it inevitably disenfranchised the marginalised impoverished native capture fishers and stifled the marginal growths of crocodile ranching during that period.

In as much as fish was classified as an animal and fishing, that is, capture fisheries was a form of hunting, there was a provision for sport fishing which was a form of recreation and a form of conservation as a mark-recapture method in the Games and Fish Amendment Act of 1938 (Malasha, 2002). The fines for illegal fishing were deterrent enough to dissuade, mostly, the poor local ‘natives’ from wantonly fishing (open access restrictions) in various water bodies in the country. This to a certain extent aided in the conservation of the introduced exotic alien invasive fish species such as the Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), brown trout (Salmo trutta) and rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), and largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) (Toots, 1970; Bell-Cross and Minshull, 1988). The flip side was that by regulating and giving room for expansion and invasion of the exotic fish species there was massive biodiversity loss and displacement of indigenous fish species in the water systems (Marshall, 2011).

Nonetheless, the various angling associations also established research stations in the country to improve the strain of imported fish species to local conditions (Malasha, 2002). Some of these research stations were privately run while others relied on government subsidies (Malasha, 2002). There was enforcement of closed seasons, and no breeding zones in some waters in the Games and Fish Amendment Act of 1938 and this was mainly for the protection of fry and to facilitate growth and transfer of fingerlings (Malasha, 2002). Specification of the mesh sizes of nets, width of apertures in traps and baskets was included in this Act. Further, there was proscription of deleterious hunting and fishing methods considered unfair to game and fish, for example, blasting, and dynamite fishing. Although it should be noted that this Act was colonial in that it proscribed, mostly, African fishing methods such as traps, spears, baskets, nets and advocated for more Anglo-Saxon methods, for example, gill nets, hook and line, and kapenta rigging (Malasha, 2002).

In Southern Rhodesia, the development and amendments of fishing regulations during the consolidation period of 1891–1938 were driven more by individuals, associations and clubs with an interest in sport fishing than government initiative (Mudzengi et al., 2021). Also, for the period 1891–1938, licences and permits were enacted and used to control access to fish resources on the surface. However, it appears licences and permits were a revenue channel for the government who were accused of failing to provide adequate institutional and facility support for capture fisheries, never mind aquaculture operators, and totally neglected crocodile ranching (Blake, 1982; Malasha, 2002). In some ways, granting of fishing permits in some dams for ordinary fishers and cooperatives was (and is still being) used as a political tool by unscrupulous politicians during election times. The initiative was never intended to leverage fisheries resources for food security, upliftment and empowerment and sustainable livelihoods of natives at that time but to enhance and sustain the lifestyles of the rich white elites (Malasha, 2002). However, Native Authorities using the then Rhodesian Parks collected the fishing permit and licence and game hunting fees and used part of it to pay the salaries and welfare of Chiefs in the respective areas. Thus, most Chiefs supported the issuing of fishing and game permits per se as it mainly benefitted them to the detriment of the already colonised and impoverished natives.

After the 1938 landmark Game and Fish Amendment Act there was adoption of the Game Ordinance 1941 Act modelled from Northern Rhodesia or modern day Zambia. This Act was intended to consolidate the Game and Fish Amendment Act of 1938. It emphasized on the statutes governing the removal, prohibition and proscription of harmful hunting and fishing methods (Malasha, 2002). Some of the fishing techniques such as fish driving by water splashing and paddle beating in predominantly shallow waters and weedy areas where fish breed and spawn, game driving, stampede and distraction were strictly prohibited (Hey, 1948; Malasha, 2002). The proscribed fishing methods were considered as bad and ‘unecological’ methods although in reality they were considered ‘African’ methods (Malasha, 2002). The scientific justifications masked the political and economic interests of the colonial government at that time which were to preserve recreational and sport fish angling as a domain and activity for the elite and privileged ruling white classes and ‘learned’ middle class income earning African professionals such as teachers, lawyers and nurses at that time (Malasha, 2002). There were no stand-alone provisions for crocodile ranching and neither did they consider fish farming, that is, aquaculture. Rather wild capture fisheries in the form of recreational angling and subsistence gill and seine netting and using various methods and traps, for example, baskets were considered and mentioned in all the provisions (Malasha, 2002).

In 1941, the Natural Resources Act which provided ‘for the conservation and improvement of the Natural Resources of the Colony’ and matters incidental thereto, including the creation of a Natural Resources Board (NRB) was enacted in Southern Rhodesia (Child and Child, 2015). The Governor of Southern Rhodesia was accorded the powers to appoint the board with special regard to having members with knowledge and expertise in its remit, and covering such aspects as water supplies, agriculture, mining, African areas, forestry, and the like. The Act also provided a framework to establish a countrywide network of volunteer Intensive Conservation Area (ICA) committees and, from the outset, broadened the NRB’s mandate beyond soil conservation (Child and Child, 2015). It achieved this feat by defining the country’s natural resources holistically, as: (a) the soil, water and minerals; (b) the animal, bird and fish life; (c) the trees, grasses and other vegetation; d) the springs, vleis, sponges, reed-beds, marshes, swamps and public streams; and (e) such other things as the governor may, by proclamation in the Gazette, declare to be natural resources, including landscapes and scenery, which in his opinion should be preserved on account of their aesthetic appeal and scenic value (Child and Child, 2015). This was a baseline land mark Act as it further broadened the natural resources that warranted full conservation and pertinently it specified fish as a natural resource requiring attention (Murombedzi, 2003a, b). Regardless, the term ‘animal’ is simplistic as it just aggregates all forms of animal life (vertebrate and invertebrate) together without classification. No two species are alike and thus, they require different conservation approaches, strategies and measures. What was important was that the Natural Resources Act of 1941 made a provision for the creation of a Natural Resources Board with sweeping powers over all conservation matters in the country (Murombedzi, 2003a, b).

In 1949, the Natural Resources Board enacted the National Parks Act, and its first task was to upgrade the Wankie (Now Hwange) Game reserve which was initially formed in 1928 to a fully-fledged Wankie National Park with a mandate to preserve game and fish resources in the park (Murombedzi, 2003a). Afterwards, in 1952, the then-Rhodesia’s game section was originally formed as a subsidiary of the Department of Mines, Lands and Surveys (Muboko and Murindagomo, 2003a). The game section was transformed into the Department of National Parks and Wildlife Management in 1964 (Murombedzi, 2003b). Afterwards, in 1960, the Game Section under the guidance and supervision of the Natural Resources Board advocated for the formation of Conservation Committees (Murombedzi, 2003b). These Conservation Committees had clear mandates and specific sections as set out in the 1949 National Parks Act of conserving game resources, that is, terrestrial animals, terrestrial plants, birds and water resources specifically fish and related hydrobionts, for example, crocodiles, hippotamuses among others (Murombedzi, 2003b). The formation of the Conservation Committee was a precursor to the enactment of the Wildlife Conservation Act of 1960, that advocated for the conservation of wildlife in national parks and other ‘designated areas’ which were not really specified in the Act (Murombedzi, 2003b). It was a sweeping Act as it aggregated all plant and animal resources as wildlife with no clear distinction of the specific categories (Murombedzi, 2003b). Further, the Act did not separate different species and categories of plants, animals, hydrobionts and birds and reptiles among others (Murombedzi, 2003b). In fact, it was modelled on the same lines and had similar flaws as the Games Laws of 1891–1938 (Murombedzi, 2003b).

After this realisation and under pressure from the wealthy and powerful Rhodesian Angling Societies, the Natural Resources Board through the Game Section enacted the Fish Conservation Act of 1961 (Malasha, 2002). This Act, specifically, dealt with fish and related hydrobionts such as water birds, hippos and crocodiles. For the first time, the conservation of wildlife acknowledged crocodiles as a stand-alone species that warranted the full and undivided attention of the National Parks Authorities in terms of licencing and permitting the collection of eggs, adult and juvenile specimens from water systems (Blake, 1982). Regardless, the Fish Conservation Act of 1961 was still skewed towards wild capture fisheries, that is, recreational fish angling and restricting fishing methods, and did not even attempt to address the issue of fish farming (aquaculture). Rather, it tightened the requirements for importation permits of exotic and introduced fish species such as trout and kapenta as a way of restricting the entrance of upcoming wealthy local (native) businessmen into the lucrative businesses such as crocodile ranching at that time (Blake, 1982). More, pertinently, it gazetted some provisions for the trade and export of crocodile skins harvested from the wild (which was being done by a few white farmers in shared water ways such as the Zambezi River) and was not enacted to create equity and opportunities for the sustainable exploitation of fish resources by poor native people in Southern Rhodesia (Blake, 1982; Loveridge, 1996).

As a follow through the Parks and Wildlife Act of 1963 was enacted to clearly demarcate the so called ‘designated’ areas in the Wildlife Conservation Act of 1960 and to create a fully-fledged Parks Board with autonomy over the matters of wildlife conservation in the country but still under the Natural Resources Board (Malasha, 2002). The Parks and Wildlife Act of 1963 amalgamated the Wildlife Conservation Act of 1960, Fish Conservation Act of 1961 and the Natural Resources Act of 1949 under the Natural Resources Board (Malasha, 2002). The Parks and Wildlife Act of 1963 exerted a strain on the operational efficiency of the Natural Resources Board which now had total control and oversight of the natural and wildlife and fisheries resources in protected areas, that is, national parks and even in areas outside of the protected wildlife zones (Malasha, 2002). The key provision in this Act was that the ownership, custodianship and regulation of wildlife remained the prerogative of the government or Governor at that time (Malasha, 2002). It was still not clear what the ‘designated wildlife areas’ were? Moreso, there were no clear provisions for aquaculture and crocodile ranching in the Act (Malasha, 2002). However, what is evident from 1891-1963 was the low (if any) number of gazetted statutory instruments (SIs) to any wildlife and fisheries related Act (Malasha, 2002). The statutory instruments in reality are corrective, reactive and afterthought temporary pieces of legislations that may bring confusion to any sector if not properly implemented (Murombedzi, 2003b).

“Quintessential conservation period: 1969–1980”

In context of a latter discussion, the Rhodesian government enacted an incendiary, tenacious, segregatory Land Tenure Act of 1969 that amended an equally more tenacious and segregatory Land Apportionment Act of 1931 (Vudzijena, 1998; Murombedzi, 2003a, b). The Land Tenure Act of 1969 aimed to create different areas for each race creating divisions between Europeans and Africans, with natives settled in Tribal Trust lands and only allowed to move to urban and white only areas after gaining employment and permission respectively (Mombeshora and Le Bel, 2009). More pertinently, the Land Tenure Act of 1969 allowed Europeans to take and own native land for free (Vudzijena, 1998). In most cases, the Europeans took fertile soils and were careful enough to also occupy and own marginal wildlife rich areas in the peripheral zones of the country with harsh climatic conditions, for example, low rainfall and high temperatures, and mostly were Tsetse fly infested through purported ownership of such areas by the government (Tomlinson, 1980). The context here is that mineral and wildlife rich areas were the preserve of the elite and politically powerful in Rhodesia (Tomlinson, 1980). The ensuing conflict, over natural resources and increased poverty induced and increased poaching of wildlife and fish, forced the Natural Resources Board to enact the Trapping of Animals (Control) Act of 1974 (Tomlinson, 1980). This Act mentioned and listed the permitted and proscribed hunting and fishing techniques, and included wild crocodiles among the species with hunting restrictions (Tomlinson, 1980). The whole aim of passing the Trapping of Animals (Control) Act of 1974 was to dissuade Africans or natives from using so called ‘destructive’ hunting and fishing methods under the guise of wildlife conservation (Tomlison, 1980). This Act used the ‘fine and fortress’ approach but was not effective at curbing fish poaching and illegal crocodile egg collection even in aquatic systems located in recreational parks (Tomlinson, 1980). The Act itself was more of a reaction to the intensifying liberation war struggle in Southern Rhodesia where the colonial government aimed to stifle any source of revenue or meat for the local communities and the ‘guerrillas’ who frequently used protected areas as crossing pathways into the country to wage the armed struggle (Murombedzi, 2003b).

After the enactment of the Parks and Wildlife Act of 1963 and Trapping of Animals (Control) Act of 1974 there was a huge task for the Game Section of the Department of Mines, Lands and Surveys to oversee a broad portfolio of conservation priorities and species (Child and Child, 2015). The Natural Resources Board enacted the Parks and Wildlife Act of 1975 which established the Parks and Wildlife Management Department and repealed the Fish Conservation Act of 1961 and further amended the Parks and Wildlife Act of 1963 (Child and Child, 2015). Broadly, the Parks and Wildlife Act of 1975 aimed to ‘establish a Parks and Wild Life Board; to confer functions and impose duties on the Board; to provide for the establishment of national parks, botanical reserves, botanical gardens, sanctuaries, safari areas and recreational parks; to make provision for the preservation, conservation, propagation or control of the wildlife, fish and plants of Zimbabwe (Southern Rhodesia then) and the protection of her natural landscape and scenery; to confer privileges on owners or occupiers of alienated land as custodians of wild life, fish and plants; to give certain powers to intensive conservation area committees; and to provide for matters incidental to or connected with the foregoing’ (Gandiwa et al., 2021). The 1975 Parks and Wildlife Act established national parks, botanical reserves, botanical gardens, sanctuaries, safari areas and recreational parks – all six categories in which wildlife is carefully managed and species diversity protected (Gandiwa et al., 2021). Under the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Act of 1975 and its subsequent amendments (e.g., the Parks and Wildlife Act Chapter 20:14 of 2001) all forms of hunting are prohibited in national parks, with hunting permitted in safari areas and sanctuaries under a permit system (Child and Child, 2015).

The Parks and Wildlife Act of 1975 and its associated statutory instruments formed a comprehensive wildlife management framework which thrives for both preservation and conservation (Gandiwa et al., 2021). The Act is regarded as a quintessential breakthrough for conservation as it altered the core philosophy of local perceptions towards wildlife in Southern Rhodesia (Child and Child, 2015). Under the Parks and Wildlife Act of 1975, the ownership of wildlife passed from the state to whoever owned the land, the animal, plant or fish lived on (Malasha, 2002; Barnett and Patterson, 2002). Matter of fact, it has been viewed as the game changer of Zimbabwean modern policies of wildlife management as it quashed the confusion that prevailed over separation of administration of parks on one hand and of wildlife outside national parks on the other (Barnett and Patterson, 2005; Muboko and Murindagomo, 2014). It was also a milestone in trying to provide legitimacy to commercial farmers to manage and utilise game on their own farms (Child and Child, 2015). Commercial farmers were designated as “appropriate authority” for deciding the wildlife use on their land (Gandiwa et al., 2021). The Parks and Wildlife Act of 1975 changed the game and abetted commercial farmers who expanded their range of ownership to wildlife rich areas and had favourable provisions for crocodile ranchers (Gandiwa et al., 2021). However, its provisions restricted aquaculture developers and rural communities seeking fishing rights in water bodies inside and outside of protected areas (Gandiwa et al., 2021). Moreso, water bodies outside of protected areas fell (and still fall) under the jurisdiction of other line ministries such as the Zimbabwe National Water Authority (ZINWA), Department of Livestock Production (DLPD), and Department of Fisheries etc (Mudzengi et al., 2021). Thus, there were inevitable institutional overlaps and conflicts over the fisheries resources and aquaculture development (Mudzengi et al., 2021).

The Parks and Wildlife Act of 1975 had its positives and negatives. First, in the context of fish, crocodiles and aquaculture, it specifically set out to protect fish species in aquatic systems inside and outside of the six designated protected areas (Mudzengi et al., 2021). However, it is clear that the Act was referring to wild capture fish species and by extension to wild capture fishing cooperatives and companies, for example, kapenta rigs and never considered the issue of farmed fish or aquaculture (Mudzengi et al., 2021). Second, it did not consider the issue of crocodile ranching and its associated activities like crocodile egg and juvenile collection and harvesting methods (Van Jaarsveldt, 1982a, b). This resulted in the crafting of associated statutory instruments, for example, the Parks and Wildlife (Hunting of Crocodiles and Removal of Crocodiles’ Eggs) Notice, 1975 (S.I. No. 969 of 1975) (Blake, 1982; Loveridge, 1996). This regulated the hunting, capture, hunting authorization and permit conditions, permissible hunting gear and methods for reptiles specifically crocodiles (Blake, 1982; Loveridge, 1972). Subsequent Wildlife and Parks Acts: Parks Acts 14/1975, 42/1976 (s. 39), 48/1976 (s. 82), 4/1977, 22/1977, 19/1978, 5/1979, 4/1981 (s. 19), 46/1981, were more explicit on the permissible hunting and fishing and crocodile capturing and egg collection methods and seasons, parks access modalities, specifications on the trade and export of crocodile skins (Blake, 1982; Loveridge, 1996).

Nevertheless, all the statutory instruments and notices related to fisheries and crocodile ranching, issued up to 1981, failed to adequately regulate fish farming or aquaculture which was placed in the Ministry of Lands and Agriculture with different aspects supervised by different Departments such as the Department of Research and Specialist Services (DR& SS), Department of Livestock Production (DLPD) and some under the auspices of the Department of Parks and Wildlife Management (DNPWLM) (Mudzengi et al., 2021). Regardless, there was poor definition and regulation of the fish farming or aquaculture sector in the laws and policies of Southern Rhodesia and this persisted even up to the end of the ‘quintessential conservation period’ for wild capture fisheries and freely roaming crocodiles in 1980 (Mudzengi et al., 2021). Crocodile ranching was never properly regulated with laws skewed more towards the capturing, and hunting of crocodiles and crocodile egg collection and trade in crocodile skins from the wild (Blake, 1982; Loveridge, 1996). The attendant historical institutional overlaps and conflation persist even up to now with no clear jurisdiction over different aspects of the aquaculture sector such as fingerling production, hatchery specifications, hormonal and probiotic uses as well as placement of aquaculture either in the Ministry of Lands, Agriculture, Fisheries, Water and Rural Resettlement or Ministry of Environment, Climate and Tourism (Mabika and Utete, 2024).

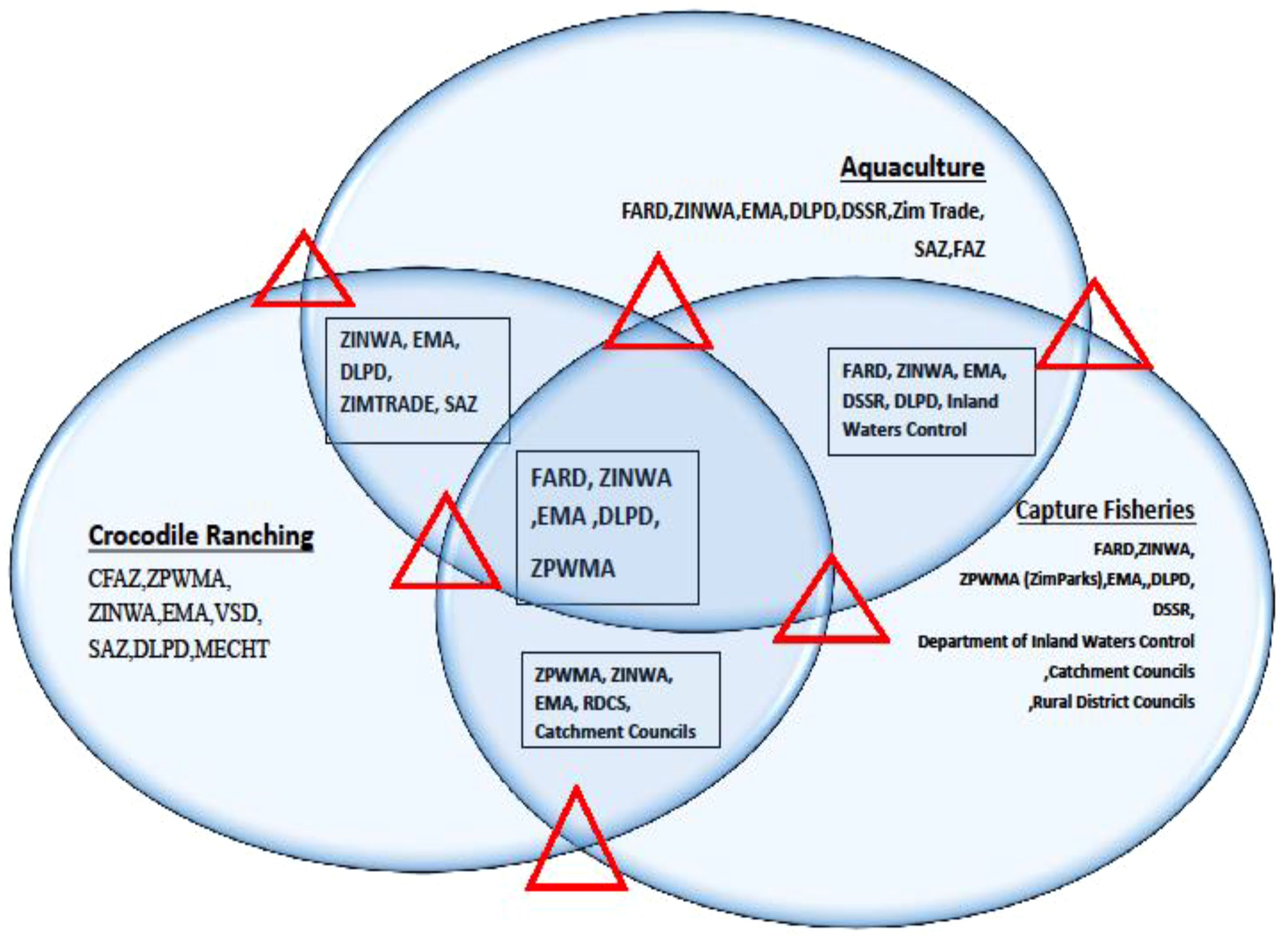

The political economy of fisheries and aquaculture policy reform in Zimbabwe predates independence and started in the colonial period where there was a concerted effort by elite white supremacists to usurp the control of fisheries and game mainly for recreational and leisure purposes (Mudzengi et al., 2021). This was achieved by heavy lobbying for deliberate exclusionary policies and laws that were skewed against the native poor communities through banning of supposedly primitive fishing methods, deliberately gazetting high and prohibitive fishing access fees, and developing selective fishing and crocodile ranching permit systems that dissuaded the participation of impoverished indigenous locals (Malasha, 2002). After enactment of the Parks and Wildlife Act of 1975 transfer of ownership of wildlife to land owners mostly, rich white commercial farmers, further complicated institutional mandates of different departments (Mudzengi et al., 2021). The ZPWMA, the Department of Fisheries, ZINWA, DLPD, Department of Fisheries, Department of Inland Waters Control, Environmental Management Authority, Rural District Councils etc all have a say in their mandates towards water bodies and the aquatic and fisheries resources therein (Mabika and Utete, 2024). This was complicated by the proliferation of different private associations such as the Crocodile Farmers Association of Zimbabwe (CFAZ), Zimbabwe Fish Producers Association, different Safari and Tour operators who have different interests in the aquaculture, fisheries, wildlife and crocodile ranching sectors (Utete, 2021; Mabika and Utete, 2024). Figure 4 outlines the institutional overlaps for the aquaculture, fisheries, crocodile ranching, and wildlife sectors in Zimbabwe. The elite capture, for example, affluent angling societies shaped recreational-biased regulations (Malasha, 2002), compounded by bureaucratic turf conflicts, for example, overlapping mandates between ZPWMA, ZINWA, and the Department of Fisheries (Mudzengi et al., 2021), and donor-driven agendas, for example, international conventions such as the CITES influencing crocodile ranching more than aquaculture (Utete, 2021) have contributed to fragmented governance and policy inertia. This, partially, explains the persistence of institutional confusion and aquaculture neglect (Mabika and Utete, 2024). Regardless, the institutional conflation and overlap is not historical or technical, but rooted in power dynamics and competing interests for fisheries and aquaculture and crocodile ranching among politicians, wildlife conservationists, conservancy owners, crocodile ranchers, water authorities, livestock and wildlife authorities alike (Utete, 2021; Mabika and Utete, 2024).

Figure 4. Institutional overlaps for the aquaculture, fisheries, crocodile ranching, and wildlife sectors in Zimbabwe. The triangle represents the nodes or intersecting points for the different institutions for each sector. Abbreviations used in this figure are listed and defined in Supplementary Table S1.

“Conservation progression period 1981–2021”

From 1981, a newly independent Zimbabwe adopted and ratified a number of international wildlife conservation treaties and conventions like the Protocol on Economic and Technical Cooperation concerning the Management and Development of Fisheries on Lake Kariba, Transboundary Waters of the Zambezi River, SADC Protocol on Fisheries, the Convention on Biological Diversity, CITES and the Ramsar Convention and is a Member of the Aquaculture Network of Africa (ANAF) (Muboko and Murindagomo, 2014; Gandiwa et al., 2021). Pertinently, the Wildlife and Parks Act of 1975 and its spill over Acts after independence began to consider, seriously, the issue of wildlife capture fisheries in cooperatives and not only for recreational and subsistence angling (Malasha, 2002). For instance, in 1981 the Parks and Wildlife (General) Regulations, 1981 (S.I. No. 900 of 1981) were gazetted. These General Regulations specifically regulated the operational modalities of inland fisheries, permitted fishing gear and fishing method, fishery management and conservation. In addition, the regulations further defined and specified protected areas, the management and conservation, and responsible institutions (Gandiwa et al., 2021). Further, the regulations specified the permissible hunting and capture, and hunting gear and hunting methods for game, birds and crocodiles, as well as hunting authorization and permit. The regulations aligned the local Acts to provisions in international conventions and treaties governing international trade in wild fauna and flora, and wildlife products (Gandiwa et al., 2021). They also specified the prosecutable wildlife offences and liable penalties, all for the protection of classified wildlife species (Gandiwa et al., 2021).

However, there was a glaring lack of regulations governing the setting up and operational modalities of fish farming or aquaculture ventures as were done for privately owned conservancies and safari and wildlife gaming areas (Malasha, 2002). In terms of crocodile ranching, there was a massive increase from the single (1) registered crocodile ranch in 1965 to at least 46 registered crocodile farms in the country from 1985 as a result of the alignment of the Parks and Wildlife (General) Regulations, 1981 (S.I. No. 900 of 1981) (CSG, 2004). Currently, there are about 18–32 crocodile farms licenced to operate in Zimbabwe with the bulk of the businesses located in hot regions such as Kariba, Chiredzi, Binga, Victoria Falls and the Lowveld, with smaller concerns also scattered in Deka (Hwange), Darwendale, Mhangura and Chinhoyi (Crocodile Farmers’ Association Zimbabwe. (CFAZ), 2016). Because of the earlier influence of Rhodesian angling societies, the permits issued by Parks and Wildlife Management Agency or Authority, as they are currently known, have always been heavily skewed towards wild capture fishing permits mainly angling and as an afterthought fishing cooperatives (disregarding the kapenta rigging enterprises) (Malasha, 2002; Mudzengi et al., 2021). A stand out Act was the Parks and Wildlife (Payment for Hunting of Animals and Fish) Notice, 1987 (S.I. No. 101 of 1987). This Act gazetted the regulations for fishing charge, and hunting authorization and permit fees for game and crocodiles and birds (Mudzengi et al., 2021). The Act was silent on the regulations of fish farming which were already established albeit at small-scale in some parts of Zimbabwe.

A notable development was the 2013 National Constitution of Zimbabwe (Government of the Republic of Zimbabwe, 2013) that spelt out the environmental rights of every Zimbabwean. Section 73(1) indicates that every person has the right to an environment that is not harmful to their health or well-being; and to have the environment protected for the benefit of the present and future generations, through reasonable legislative and other measures that-prevent pollution and ecological degradation, promote conservation, and secure ecologically sustainable development and use of natural resources while promoting economic and social development (Government of the Republic of Zimbabwe, 2013). The weakness of the 2013 Constitution as a document is that it is sweeping and does not have explicit provisions for the promulgation of specific Acts for the protection of different components of the environment from abuse by humans, who are not deterred by legal instruments and physical barriers when they want to use wildlife resources (Macheka, 2021). Regardless, it set the tone for different sectors, for example, wildlife protection, viticulture, fisheries and forestry units to instigate for amendments of different Acts to suit specific sectors (Macheka, 2021). On the previous section 72 (1) on rights to agricultural land, there is a provision for human rights to initiate wildlife and aquaculture or any other husbandry purposes on suitable land in Zimbabwe (Government of the Republic of Zimbabwe, 2013). These two sections of the national constitution of Zimbabwe recognise the importance of wildlife and fisheries for human development in the country (Macheka, 2021). Nonetheless, the convenient categorisation of the evolution of the wildlife conservation policies and practices for Zimbabwe by most authors, for example, Murombedzi (2003a, b) and Muboko and Murindagomo (2014) and Muposhi et al. (2016), is heavily skewed towards game and in most cases is silent on the conservation of fisheries moreso crocodiles that were regarded as reptiles to be managed from the same perspective as snakes and lizards.