- Institute of Biochemistry, Graz University of Technology, Graz, Austria

Fungi produce a plethora of natural products exhibiting a fascinating diversity of chemical structures with an enormous potential for medical applications. Despite the importance of understanding the scope of natural products and their biosynthetic pathways, a systematic analysis of the involved enzymes has not been undertaken. In our previous studies, we examined the flavoprotein encoding gene pool in archaea, eubacteria, the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Arabidopsis thaliana, and Homo sapiens. In the present survey, we have selected the model fungus Neurospora crassa as a starting point to investigate the flavoproteomes in the fungal kingdom. Our analysis showed that N. crassa harbors 201 flavoprotein-encoding genes amounting to 2% of the total protein-encoding genome. The majority of these flavoproteins (133) could be assigned to primary metabolism, termed the “core flavoproteome”, with the remainder of flavoproteins (68) serving in, as yet unidentified, reactions. The latter group of “accessory flavoproteins” is dominated by monooxygenases, berberine bridge enzyme-like enzymes, and glucose-methanol-choline-oxidoreductases. Although the exact biochemical role of most of these enzymes remains undetermined, we propose that they are involved in activities closely associated with fungi, such as the degradation of lignocellulose, the biosynthesis of natural products, and the detoxification of harmful compounds in the environment. Based on this assumption, we have analyzed the accessory flavoproteomes in the fungal kingdom using the MycoCosm database. This revealed large differences among fungal divisions, with Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, and Mucoromycota featuring the highest average number of genes encoding accessory flavoproteins. Moreover, a more detailed analysis showed a massive accumulation of accessory flavoproteins in Sordariomycetes, Agaricomycetes, and Glomeromycotina. In our view, this indicates that these fungal classes are proliferative producers of natural products and also interesting sources for flavoproteins with potentially useful catalytic properties in biocatalytic applications.

Introduction

Fungi are known to produce a large number of natural products for an array of functions, such as communication, detoxification, and defense. Typically, simple activated structures constitute the basis for the generation of natural products, and various enzymatic modifications of these compounds eventually lead to structurally diverse and highly complicated organic molecules. In addition to acylation, alkylation, and glycosylation, redox reactions are pivotal to defining the bioactivity of the final products. In this regard, oxidoreductases like cytochrome P450- and flavin-dependent enzymes (containing either flavin mononucleotide, FMN, and/or flavin adenine dinucleotide, FAD) play a major role (Toplak and Teufel, 2022). In order to analyze the involvement of flavoenzymes in the biosynthesis of natural products, we chose the saprotrophic filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa as a starting point. This fungus served as an important experimental model organism for almost a century culminating in the one-gene-one-enzyme hypothesis by Beadle and Tatum (Beadle and Tatum, 1941). Furthermore, N. crassa played a central role in advancing our knowledge of the molecular mechanisms of physiological and genetic processes such as the circadian rhythm and genome defense mechanisms (Galagan et al., 2003). In the same vein, N. crassa was also employed as a source for several flavin-containing enzymes and proteins in order to gain insight into central biochemical processes, for example, the isolation and characterization of the assimilatory nitrite and nitrate reductase by Garrett and coworkers (Garrett and Nason, 1967; Lafferty and Garrett, 1974; Colandene and Garrett, 1996). Another prominent example was the isolation and characterization of chorismate synthase, the last enzyme of the common shikimate pathway, by Gaertner and coworkers who demonstrated the requirement for (reduced) FMN to sustain enzymatic activity (Welch et al., 1974). Other examples include l-amino acid oxidase, which is induced in response to the addition of l-amino acids after nitrogen starvation (Sikora and Marzluf, 1982; Niedermann and Lerch, 1990), and 2-nitropropane oxygenase. The latter enzyme produces nitrite and acetone, and thus, enables the utilization of nitro-organic compounds as nitrogen and carbon source (Gorlatova et al., 1998). Finally, the discovery and characterization of cellobiose dehydrogenase (CDH) is worth mentioning (Westermark and Eriksson, 1974). As a saprotrophic fungus, N. crassa accommodates lignocellulosic biomass-degrading enzymes, including CDH. Two active CDHs of N. crassa (IIA and IIB) were expressed and characterized (Zhang et al., 2011; Sygmund et al., 2012). Recently, they have been shown to play a crucial role in lignocellulosic material degradation by providing electrons to lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase (LPMO) (Kracher et al., 2016). To date, CDHs are classified in the Carbohydrate-Active enZyme (CAZy) database and are assigned to the group AA3 (Auxiliary Activity 3). All enzymes in this group, which show a wide range of functional diversity, belong to the glucose-methanol-choline (GMC) family, which was first outlined by Cavener, 1992.

N. crassa also played a central role in the discovery of the enigmatic blue light receptor. The early work by Muñoz and Butler in 1974 provided the first experimental evidence that a flavin cofactor might serve as the light-sensing chromophore (Muñoz et al., 1974). This was eventually confirmed independently by Liu and Dunlap and their coworkers (Froehlich et al., 2002; He et al., 2002). In the case of the fungal blue light receptor, FAD is bound to the LOV domain of the protein called “white collar” (WC)-1, which forms a heterodimer with WC-2 and acts as a regulator for light-dependent processes such as the circadian rhythm and carotenoid biosynthesis. The discovery of the flavin-dependent blue light receptor WC-1, as well as other flavin-dependent proteins such as VIVID (VVD) and cryptochrome (CRY), have established N. crassa as a paradigm for the study of light-regulated developmental processes and responses in fungi (Corrochano, 2007).

On the other hand, the number of reported secondary metabolites produced by N. crassa is rather limited, comprising the histidine-derived ergothioneine, the non-ribosomal peptide coprogen, and the polyketide oxoalkylresorcylic acid (Huschka et al., 1985; Funa et al., 2007; Bello et al., 2012).

In this study, we first defined a basic (“core”) flavoproteome for N. crassa comprising flavoenzymes operating in energy metabolism and degradation of general metabolites (catabolism), biosynthesis of amino acids, cofactors and pigments, acquisition of nutrients (e. g., metal ions), redox homeostasis, RNA/DNA modifications, and light regulation. In the course of our analysis, we also found a large number of predicted flavoenzymes with an undefined function. Interestingly, these flavoenzymes belong mainly to three families: flavin-dependent monooxygenases, berberine bridge enzyme-like enzymes (BBEs), and GMC oxidoreductase. Since members of these families are frequently involved in the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, we assume that these flavoenzymes play a role in the generation of compounds with functions that are relevant to the ecological niche as well as the life cycle of N. crassa. The discovery of this accessory flavoproteome in N. crassa has prompted us to analyze the occurrence of the above-mentioned flavoenzyme families in the fungal kingdom. This led to interesting insights into the distribution of certain flavoenzyme families, indicating important contributions to the chemodiversity in fungal metabolism.

Results

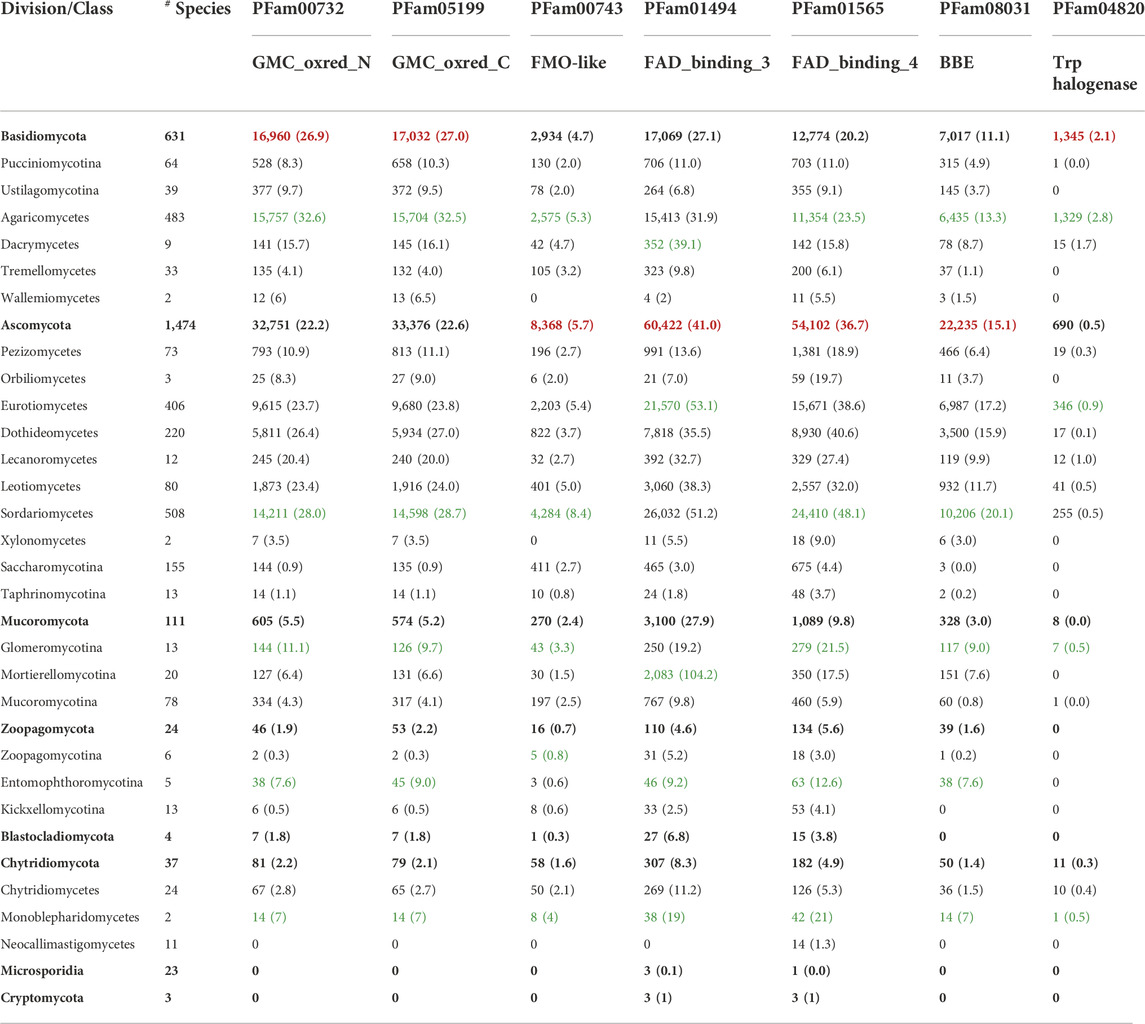

The N. crassa flavoproteome

We identified a total of 201 flavoproteins encoded in the N. crassa genome, amounting to 2% of the protein-encoding genes (Galagan et al., 2003). The functional analysis of the flavoenzymes revealed that 133 are associated with principal metabolic functions such as energy production, degradation, and biosynthesis of primary metabolites. These flavoenzymes were assigned to a core flavoproteome, summarized in Table 1. In addition to the core flavoproteome, we identified 68 flavoenzymes with mostly unknown functions. These flavoenzymes were assigned to the accessory flavoproteome of N. crassa (Table 2). We propose that these flavoenzymes operate in secondary pathways, for example, the biosynthesis of natural products that serve various crucial roles in adaptation and defense as well as the detoxification of harmful compounds, such as plant phytoalexins. The saprotrophic lifestyle of N. crassa also suggests that some of the flavoenzymes listed in Table 2 are involved in lignin degradation. We assume that the accessory flavoproteome varies substantially among fungal species depending on the ecological niche inhabited by the fungus and its survival strategy, for example, with respect to nutrient acquisition and defense requirements. We have also noticed that the accessory flavoproteome is mainly made up of a few protein families (PFam): 00732 (GMC_oxred_N), 05199 (GMC_oxred_C), 00743 (FMO-like), 01494 (FAD_binding_3), 01565 (FAD_binding_4), and 08031 (BBE). Flavoenzymes belonging to PFam01494 and 00743 catalyze monooxygenation reactions of aromatic ring systems (e. g., salicylate hydroxylase) and Baeyer-Villiger-type reactions, respectively (e. g., cyclohexanone monooxygenase). In addition, flavin-containing monooxygenase (FMO)-like enzymes (PFam00743) are known to catalyze the monooxygenation of heteroatoms such as nitrogen and sulfur. Unfortunately, reliable biochemical data on the function of these monooxygenases is currently not available. In the case of the predicted monooxygenase encoded by NCU07224T0, our analysis indicated a close relationship to FqzB (37% sequence identity), a group A FPMO epoxidase from Aspergillus fumigatus involved in the biosynthesis of fumiquinazoline (Matsushita et al., 2020; Westphal et al., 2021). Moreover, structural superposition of the FqzB crystal structure (PDB code: 7cp6) with the AlphaFold model generated for the N. crassa protein encoded by NCU07224T0 shows a Cα-RMSD of 1.7 Å, confirming a close structural relationship. Interestingly, FqzB itself was reported as a monooxygenase similar to the maackiain detoxification enzyme (MAK1) discovered in Nectria haematococca (Covert et al., 1996). MAK1 reduces the toxicity of the phytoalexin maackiain by hydroxylation of one of its aromatic rings, thus contributing to the virulence of the phytopathogenic fungus. It is thus conceivable that the protein encoded by NCU07224T0 assumes a similar role, although the producer, as well as the chemical structure of the potentially harmful substance, remain unknown.

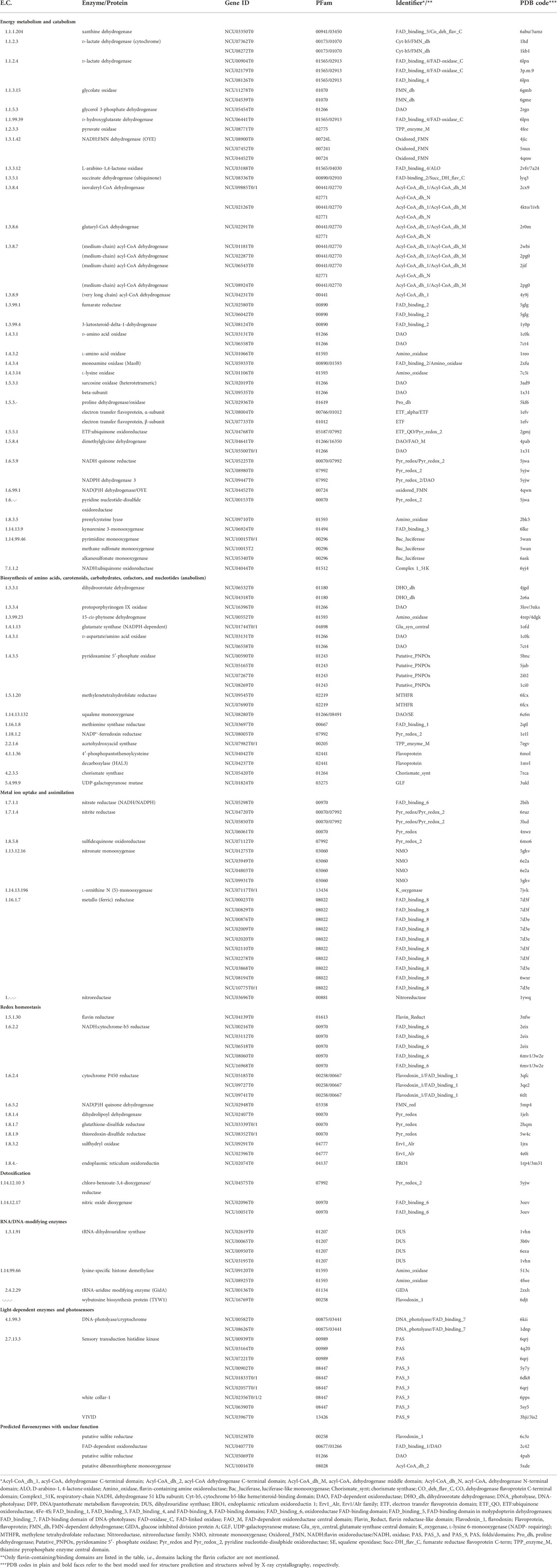

TABLE 1. The core fungal flavoproteome of Neurospora crassa (tricarboxlic acid cycle, β-oxidation, amino acid metabolism, cofactor biosynthesis, carotenogenesis, metal uptake, tRNA-modifications, light regulation, pyrimidine and purine metabolism).

TABLE 2. The accessory flavoproteome of N. crassa. The Table comprises flavoenzymes potentially involved in secondary metabolism (for example encoded in biosynthetic gene clusters) or catalyzing unidentified reactions. The PDB codes indicate the closest structural model.

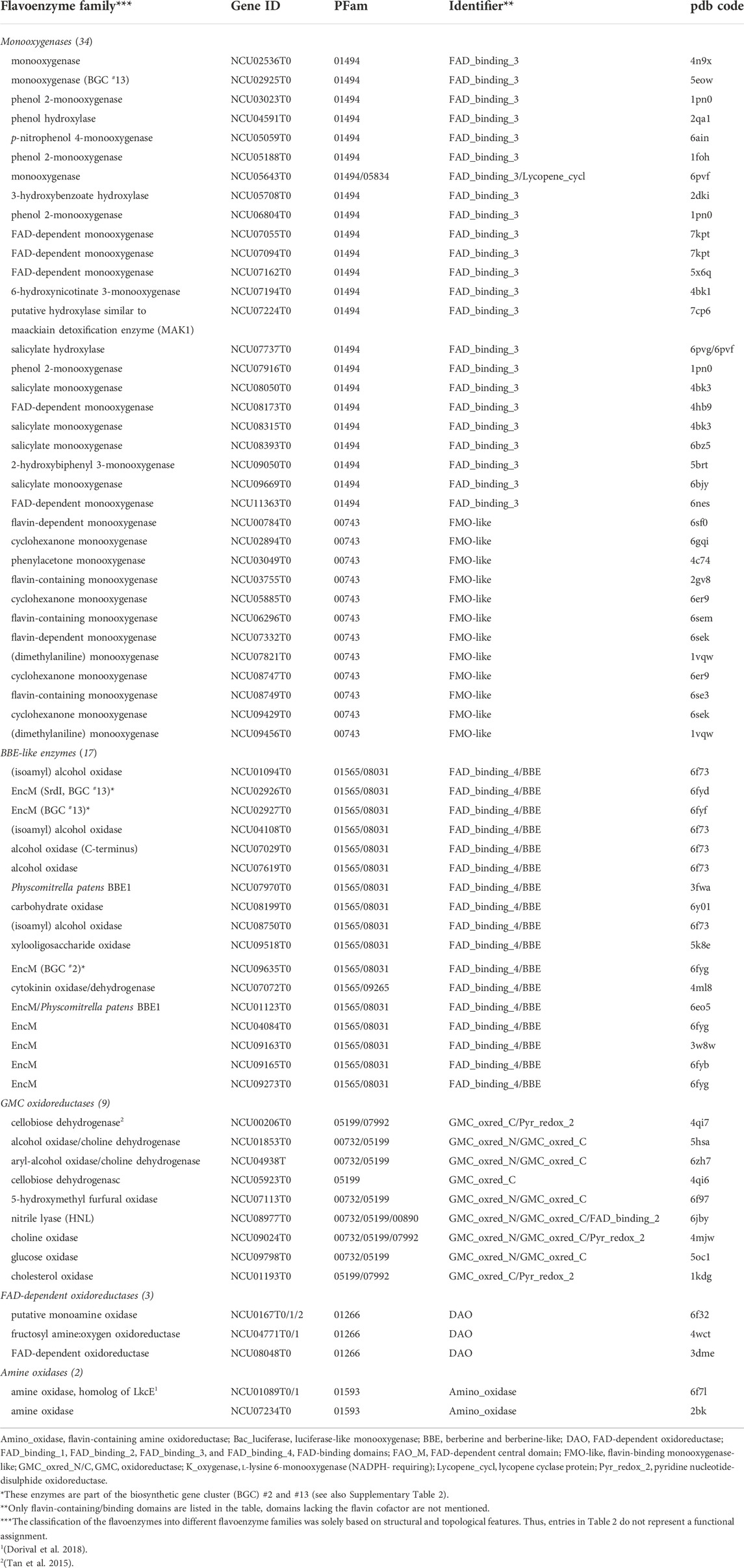

The second-largest group of accessory flavoenzymes are the BBE-like enzymes. They belong to the superfamily of FAD-linked oxidases and are closely related to the VAO/PCMH family (vanillyl alcohol oxidase/para-cresol methylhydroxylase). They share common structural features such as the conserved flavin binding (FAD_binding_4) and substrate binding domain (cap domain). In addition to these shared elements, BBE-like enzymes exhibit a unique C-terminal structural element preceding the substrate binding region (Daniel et al., 2017; Ewing et al., 2020). Another salient characteristic of the BBE-like enzymes is their propensity to bind FAD bicovalently, whereas VAO-like enzymes tend to attach their flavin cofactors either mono- or non-covalently (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. BBE-like enzymes in N. crassa. The crystal structure of BBE from Eschscholzia californica (PDB entry: 3d2d) was used as a reference (upper left). The AlphaFold models of the BBE-like enzymes from N. crassa are shown according to their structural deviation (expressed as Cα-RMSD) from the reference model. The BBE domain and the FAD-binding domain 4 of all enzymes are colored in red and magenta, respectively. The domains were assigned and colored according to their PFam annotation (Mistry et al., 2021). The remaining structure of each enzyme, including the substrate-binding domain, was colored according to the putative enzymatic function (color code: BBE, green; alcohol oxidase, yellow; carbohydrate oxidase, grey; cytokinin oxidase, blue; EncM, cyan; PpBBE1, orange; xylooligosaccharide oxidase, brown). The Cα-RMSD value to the reference model and the gene ID for each BBE-like enzyme are given in square and round brackets, respectively.

In the simplest cases, the BBE-like enzymes perform the oxidation of alcohol groups, for example, at the anomeric center of mono-, di-, or oligosaccharides, leading to the corresponding lactones (reviewed by Daniel et al., 2017). On the other hand, BBE-like enzymes also carry out complex cyclization reactions that are part of the biosynthesis of many important natural products such as alkaloids and terpenes (Sirikantaramas et al., 2004; Winkler et al., 2008). In order to evaluate the catalytic capacities, we generated structural models of the seventeen putative BBE-like enzymes in N. crassa using AlphaFold (Jumper et al., 2021). As shown in Figure 1, the models feature similar structural domains as identified in our reference model BBE from Eschscholzia californica. Intriguingly, this analysis revealed a close relationship to EncM, carbohydrate and alcohol oxidases. EncM is a bacterial flavoenzyme involved in the biosynthesis of enterocin in Streptomyces maritima and catalyzes a complex dual oxidation reaction (Teufel et al., 2013). Moreover, this enzyme was shown to form an unusual flavin N-5 oxide species during the catalytic cycle, and therefore, it is tempting to speculate that the structural relatives from N. crassa share the propensity to generate this catalytic intermediate for yet unknown (biosynthetic) transformations. The remainder of the BBE-like enzymes in N. crassa are putative oxidases/dehydrogenases of carbohydrates (e.g., cellobiose and oligosaccharides) and alcohols. Regarding the putative carbohydrate oxidases/dehydrogenases, the recent identification of fungal oligosaccharide-oxidizing flavoenzymes from the auxiliary activity family 7 (AA7) is very intriguing (Haddad Momeni et al., 2021). Apparently, members of this family are capable of donating electrons to the copper-dependent LPMOs and thus boost the oxidative cleavage of recalcitrant polysaccharides such as lignocellulose (Vaaje-Kolstad et al., 2010). Two of the BBE-like enzymes discovered in N. crassa, namely NCU08199T0 (putative carbohydrate oxidase) and NCU09518T0 (putative xylooligosaccharide oxidase), share high structural similarity (Cα-RMSD of 1.6 and 0.8 Å, respectively) with an oligosaccharide dehydrogenase from Fusarium graminearum (FgChi7B, (Haddad Momeni et al., 2021), and therefore, may constitute a relevant enzymatic system to fuel LPMOs. A hallmark of the BBE-like enzyme family is the bicovalent attachment of the FAD cofactor by a histidine and cysteine residue to the 8α- and 6-position, respectively, of the isoalloxazine ring system (Winkler et al., 2008). In fact, eleven of the BBE-like enzymes of N. crassa (Figure 1) feature these two residues according to the generated AlphaFold models at the appropriate positions, and thus, we predict that a bicovalent linkage is formed in these proteins.

GMC-oxidoreductases (represented by PFam00732 and PFam05199) predominantly catalyze the oxidation of hydroxyl groups in a large variety of substrates (e.g., carbohydrates and alcohols) but also the oxidative deamination of N-methyl groups (e.g., choline) (see Table 2). Recently, it could be demonstrated that the proteins encoded by NCU00206T0 and NCU05923T0 act as cellobiose dehydrogenases (part of the AA3_1 family in the CAZy database) and deliver electrons via a cytochrome domain to LPMOs (Tan et al., 2015; Kracher et al., 2016). Apparently, flavoenzymes from the BBE-like (part of the AA4 family in the CAZy database) enzyme as well as the GMC-oxidoreductase family participate in the enzymatic degradation of extracellular lignocellulose by providing electrons to LPMOs (AA7 family in the CAZy database).

Although not very numerous, amine oxidases are also an interesting group of accessory flavoenzymes (PFam01593, Table 2) with respect to their potential role in the biosynthesis of natural products. In fact, N. crassa harbors a gene (NCU01089T0/1) that encodes an amine oxidase homologous to LkcE from the lankacidin polyketide biosynthetic pathway of the bacterium Streptomyces rochei (Dorival et al., 2018). Since the biosynthesis of polyketide macrocycles in N. crassa has not been described, the role of the N. crassa homolog is currently unknown.

The genes encoding enzymes for the biosynthesis of natural products are frequently organized in so-called biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs). The genome of N. crassa harbors sixteen BGCs, but only two of them (#2 and #13) contain one and three flavoenzymes, respectively (see Supplementary Table S1). In the latter case, it has been suggested that this BGC synthesizes the phytotoxic salicylaldehyde sordarial known from the fungus Magnaporthe oryzae (Zhao et al., 2019). The role of the BBE-like enzyme (NCU02926T0, termed SrdI) appears to be the oxidation of an alcohol group to the corresponding aldehyde yielding a salicylaldehyde derivative. The role of the other BBE-like enzyme (NCU02927T0), however, is unclear, as is the case for the (aromatic-ring) hydroxylase found in the same BGC (NCU02925T0). Thus, only four out of 68 flavoenzymes listed as part of the accessory flavoproteome (see Table 2) are related to BGCs, whereas the majority (>90%) are not organized within BGCs.

Despite its importance as a model organism, the number of elucidated three-dimensional structures of N. crassa proteins is surprisingly low. In fact, only 127 PDB entries (as of 15 August 2022) describe structures of N. crassa proteins, with 10 entries related to flavoproteins. However, these PDB entries cover only two flavoproteins, VIVID (9 entries!) and cellobiose dehydrogenase (see Tables 1, 2; Kracher et al., 2016). This large bias toward VIVID reflects the importance of N. crassa as a model organism to investigate light-dependent processes. In contrast to N. crassa, 5,371 entries (as of 15 August 2022) presently relate to proteins from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (5,885 protein-encoding genes, (Goffeau et al., 1996), and 101 PDB entries to yeast flavoproteins (68 genes encode flavoproteins, (Gudipati et al., 2014).

Occurrence and distribution of accessory flavoenzymes in fungi

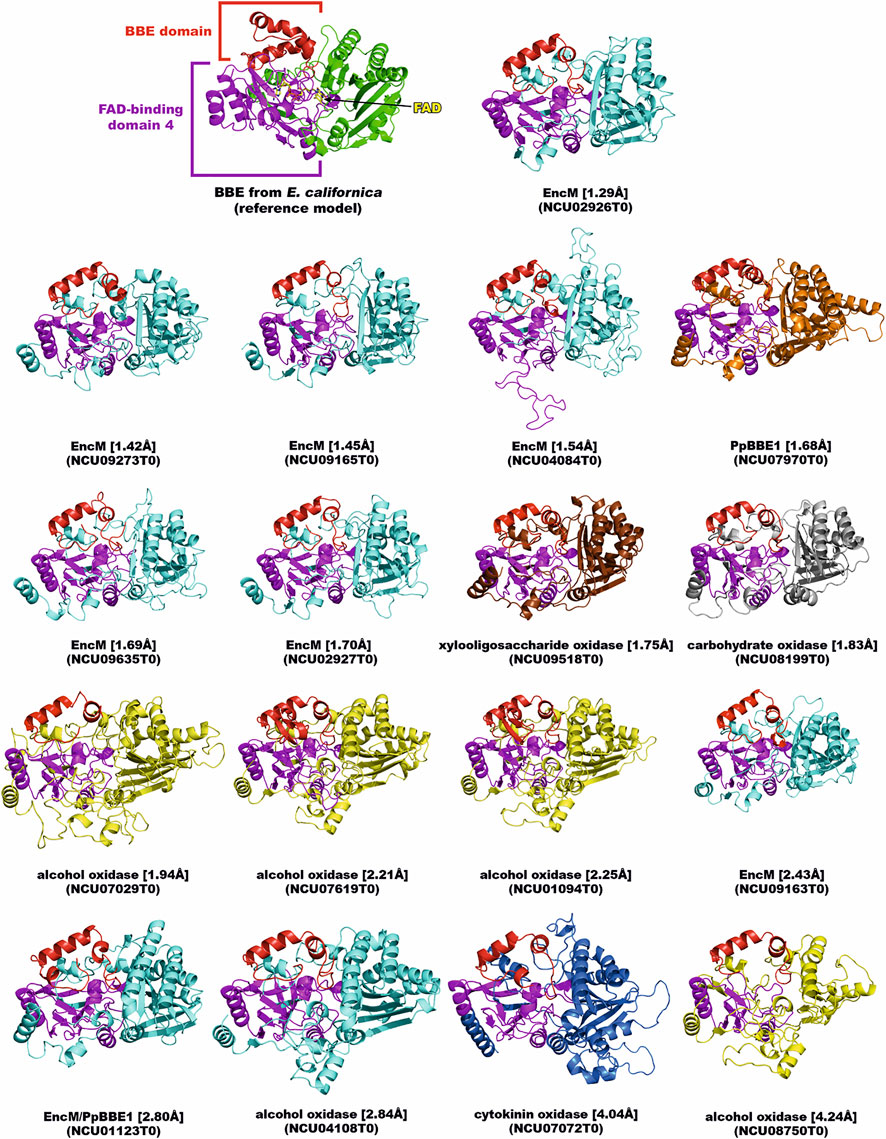

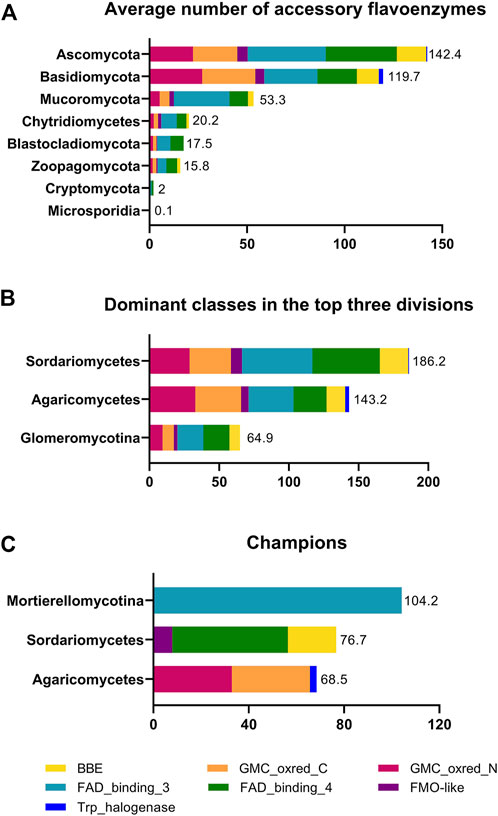

The large number of accessory flavoenzymes in N. crassa prompted us to conduct a global analysis of the fungal kingdom based on the information available at the MycoCosm resource database (www.mycocosm.jgi.doe.gov). Since the analysis of the N. crassa genome indicates that the accessory flavoproteome is dominated by flavin-dependent (aromatic) monooxygenases (represented by PFam01494), FMO-like monooxygenases (represented by PFam00743), FAD-dependent oxidoreductases/BBE-like enzymes (represented by PFam01565 and PFam08031), and GMC-oxidoreductases (represented by PFam00732 and PFam05199), we focused on these flavoenzyme families. This analysis revealed large differences between the fungal divisions and also within the classes. As shown in Table 3, Basidiomycota and Ascomycota are very rich in all of the flavoenzymes characteristic of the accessory flavoproteome, whereas Mucoromycota, Zoopagomycota, Blastocladiomycota, and Chytridiomycetes feature only a few accessory flavoenzymes. In two divisions, i. e., Microsporidia and Cryptomycota, accessory flavoenzymes appear to be completely absent (Table 3 and Figure 2, panel A).

TABLE 3. Accessory flavoproteomes in the fungal kingdom. The Table provides the total number of genes encoding for flavin-dependent enzymes that belong to the family of GMC oxidoreductases (GMC_oxred_N and GMC_oxred_C), FMN-dependent monooxygenases (FMO-like), FAD-dependent monooxygenases (FAD_binding_3), BBE-like enzymes (FAD_binding_4 and BBE), and the FAD-dependent monooxygenases (Trp_halogenases). The numbers in parentheses indicate the average number of genes found in each division and class. The highest average numbers found in the fungal divisions are highlighted in red; the highest average numbers within a division are highlighted in green (last updated on 15 August 2022).

FIGURE 2. Distribution of accessory flavoenzymes in fungi. Panel (A) shows the average number of accessory flavoenzymes in the eight fungal divisions. Panel (B) shows the classes with the highest average number of accessory flavoenzymes for the divisions Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, and Mucoromycota, i.e., Sordariomycetes, Agaricomycetes, and Glomeromycotina, respectively. Panel (C) highlights the classes with the highest average number of accessory flavoenzymes in fungi. The data used in the figure was extracted from Table 3.

Interestingly, the accessory flavoenzymes are most prevalent in certain classes such as the Agaricomycetes, Sordariomycetes, and Mortierellomycotina for the divisions Basidiomycota, Ascomycota, and Mucoromycota, respectively (Figure 2, panel B). As a matter of fact, Agaricomycetes have the highest content of GMC-oxidoreductases (PFam00732/05199), whereas Sordariomycetes harbor the largest number of FMO-like (PFam00743) and BBE-like enzymes (PFam01565 and PFam08031). Remarkably, in the class Mortierellomycotina, an exceptionally large number of FAD-dependent monooxygenases (PFam01494, FAD_binding_3) was found. In fact, the average occurrence in this genus (104.2/species) is more than twice as high as in Eurotiomycetes (52.4/species). On the other hand, the occurrence of all other accessory flavoenzymes in Mortierellomycotina, as well as in the entire division Mucoromycota, is rather low (see Table 3). In Mortierellomycotina, the highest number of FAD-dependent monooxygenases was found in Mortierella elongata NVP64 (encoded by 215 genes). This fungus is known to host bacterial endosymbionts, such as Mycoavidus cysteinexigens (Uehling et al., 2017). However, it is unclear whether the large number of FAD-dependent monooxygenases is connected to this distinct lifestyle. Interestingly, in the case of Mortierella verticillata (152 genes encoding FAD-dependent monooxygenases), it was demonstrated that the bacterial endosymbiont produces protective compounds against fungivorous nematodes (Büttner et al., 2021). These cytotoxic benzolactones (necroximes) feature several groups, such as hydroxyl, epoxy, and oxime, that suggest the involvement of FAD-dependent monooxygenases. In other words, it is conceivable that fungal enzymes might participate in the biosynthesis of these anthelmintic compounds. On the other hand, this does not rationalize the extremely large number of genes encoding FAD-dependent monooxygenases.

Although flavin-dependent halogenases are not very numerous (total number in fungi: 2054 genes as of 15 August 2022), their appearance is strongly linked to the occurrence of the other families of accessory flavoenzymes, and thus, Agaricomycetes (in the division Basidiomycota), as well as Sordariomycetes and Eurotiomycetes (both in the division of Ascomycota), contain by far most of the flavin-dependent halogenases (see Table 3). Since flavin-dependent halogenases (group F of the flavin-dependent monooxygenases, Paul et al., 2021) are known to catalyze the halogenation of aromatic rings such as indole or phenyl rings, it can be expected that fungal halogenases are involved in the halogenation of similar structures en route to species-specific natural products. It should also be noted that flavin-dependent halogenases can utilize chlorine, bromine, and iodine for substrate halogenations, mostly depending on the availability of the halide. In this context, it is worthwhile mentioning that flavin-dependent halogenases are attractive biocatalytic tools to broaden the scope of accessible compounds in medicinal chemistry (Fraley and Sherman, 2018).

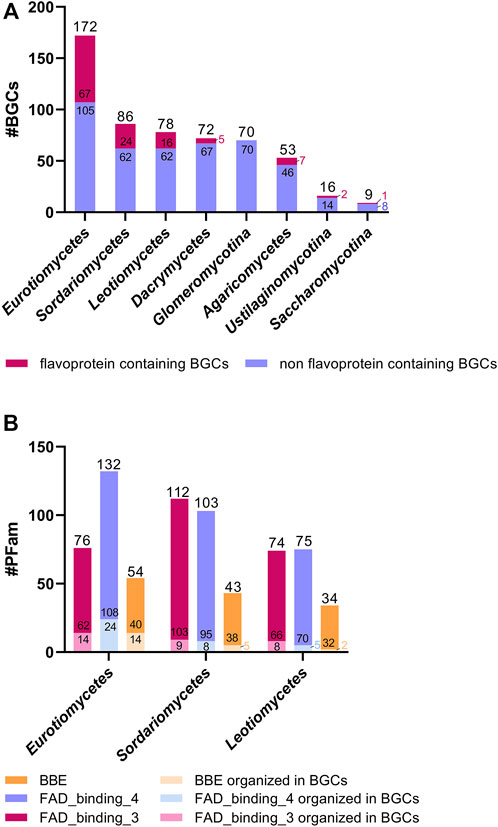

Finally, we have analyzed the occurrence of flavoenzymes in BGCs in various fungal classes. As shown in Figure 3A, the number of BGCs, as well as the number of BGCs containing flavoenzymes, varies considerably. The highest number of BGCs was found in Eurotiomycetes, with 67 BGCs containing at least one flavoenzyme (i.e., 40%, for details, see Table S2). The other fungal classes contain fewer BGCs and also fewer BGCs harboring flavoenzymes (>28%–0%). The most dominant flavoenzyme families occurring in fungal BGCs are FAD-dependent monooxygenases (PFam01494), oxidoreductases (PFam01595), and BBE-like enzymes (PFam08031). However, it should be noted that the majority of genes encoding members of these flavoenzyme families are not part of a BGC, as shown in Figure 3B.

FIGURE 3. Occurrence of flavoenzymes in BGCs. Three species were analyzed for each class. Panel (A) shows the total number of BGCs, with the top part (in red) representing the number of BGCs containing at least one flavoenzyme. Panel (B) shows the distribution of the three most common families of flavoenzymes, FAD_binding_3, FAD_binding_4, and BBE, in Eurotiomycetes, Sordariomycetes, and Leotiomycetes. The analysis is based on the data compiled in Supplementary Table S2.

Discussion

The previous analysis of the flavoproteome of S. cerevisiae (class Saccharomycotina) has revealed a relatively small number of flavoenzymes (68 out of 5,885 protein-encoding genes, i.e., 1.1% of the proteome) (Gudipati et al., 2014). Moreover, it appears that most, if not all flavoenzymes, are involved in basic metabolic functions, in other words, they belong to the core flavoproteome. In contrast, the flavoproteome of N. crassa (class Sordariomycetes) comprises not only a much higher number of core flavoenzymes (201 of 10,082, i.e., 2% of the protein-encoding genes (Galagan et al., 2003) but also a substantial number of accessory flavoenzymes (68 of 201, i.e. 33.8% of flavoprotein coding genes). It should be noted that the classification into core and accessory flavoenzymes reflects to some extent the lack of solid biochemical knowledge currently available for these enzymes. Hopefully, future research efforts will allow more accurate functional assignments of the accessory flavoenzymes, leading to a consolidated classification (detoxification, defense, etc.). In any case, in the course of further analysis, we noticed that the accessory flavoproteome of N. crassa is dominated by two types of reactions: monooxygenation and oxidation. The former reaction is catalyzed by flavoenzymes, which either exhibit the FAD_binding_3 or the FMO-like domain. Oxidation reactions, on the other hand, belong either to the BBE-like enzymes or to the GMC-oxidoreductases (see Table 2). Both types of biochemical transformations are frequently found in natural product biosynthesis, and therefore, we assume that N. crassa synthesizes several more yet unidentified compounds. In this context, it is noteworthy that members of the BBE-like enzyme family catalyze rather unusual and complex oxidation reactions that lead, for example, to the formation of additional ring systems in alkaloid, terpene, and polyketide biosynthetic pathways (Kutchan and Dittrich, 1995; Shoyama et al., 2012; Teufel et al., 2013).

Intrigued by the large and unexpected number of monooxygenases and oxidases in N. crassa, we expanded our analysis and explored the occurrence of the accessory flavoenzymes in the entire fungal kingdom by using the MycoCosm database. As shown in Table 3, accessory flavoenzymes are predominantly found in Ascomycota and Basidiomycota, with a much lower occurrence in the other fungal divisions. Within the Basidiomycota, the class Agaricomycetes features the highest average number of all accessory flavoprotein families except for the flavin hydroxylases (FAD_binding_3), which show a slightly higher occurrence in Dacrymycetes. Similarly, Sordariomycetes in the division Ascomycota also harbor the highest number of these accessory flavoenzymes. Interestingly, VAO-like enzymes, which are absent in N. crassa, were mainly found in the class of Agaricomycetes, Eurotiomycetes, and Sordariomycetes (Gygli et al., 2018). Thus, accessory flavoenzymes are not uniformly distributed but exhibit accumulation in certain fungal classes, reflecting their outstanding chemodiversity. To further substantiate this relationship, we have included the flavin-dependent halogenases in our analysis (Table 3 and Figure 2). In terms of their reaction mechanism, flavin-dependent halogenases are related to the monooxygenases in that they also generate a flavin 4a-hydroperoxide intermediate. However, instead of transferring an oxygen atom to the substrate, this intermediate reacts with a halide (typically chloride or bromide) and subsequently transfers the halogen to the aromatic ring of the substrate. Thus, the halogenation reaction relies on the “invention” of the flavin 4a-hydroperoxide, and therefore, it is tempting to hypothesize that flavin-dependent halogenases have evolved from the flavin-dependent monooxygenases. This notion is also supported by the structural similarity of these enzyme families, as both feature a three-layer ββα sandwich flavin-binding domain (Paul et al., 2021).

The rapidly increasing number of fungi-derived organohalogens suggests an important role for the producing species. As noted recently, 217 organohalogen compounds were described in marine fungi from 1994 to 2019 (Wang et al., 2021). Most of these compounds are produced by Aspergillus and Penicillium species, which belong to the Eurotiomycetes. In terrestrial fungi, organohalogens were isolated from Aspergillus, Malbranchea, and Penicillium species (Eurotiomycetes); Colletotrichum and Diaporte species (Sordariomycetes); and Alternaria, Cochliobolus, and Helminthosporium species (Dothiodeomycetes) (Gribble, 2018). Notably, all of these classes belong to the division Ascomycota (and subdivision Pezizomycotina), which represents the division with the highest average number of accessory flavoenzymes (see Table 3 and Figure 2, panel A). Similarly, Agaricomycetes in the division Basidiomycota feature the highest average number of flavin-dependent halogenases (see Table 3 and Figure 2, panels A–C). Interestingly, the flavin-dependent halogenase described for some Russula species is similar to CmlS, which carries out the dichlorination of N-acetyl-p-nitrophenylserinol to chloramphenicol in the bacterium Streptomyces venezuelae (Podzelinska et al., 2010). Thus, it is conceivable that Russula species also produce chloramphenicol or a similar organohalogen. This would be in line with the recent proposal that the edible mushroom Russula nigricans might be responsible for the production of dichloroacetic acid, which could be released by hydrolysis of the amide bond in chloramphenicol (Lajin et al., 2021). In summary, flavin-dependent halogenases are an interesting addition to expand the scope of modifications in natural product biosynthesis.

As mentioned before, the genes encoding the enzymes of a biosynthetic pathway are frequently organized in so-called BGCs. Much to our surprise, we found that most fungal BGCs do not contain any flavoenzymes, even the classes with the highest average number of accessory flavoenzymes, such as Agaricomycetes and Sordariomycetes (Figure 3A). In line with this, the majority of accessory flavoenzymes are encoded by genes that are not part of BGCs, as shown in Figure 3B. For example, in the case of N. crassa, only three out of 68 accessory flavoenzymes are encoded by genes in BGC #2 and #13 (see Table 2). Does this finding contradict the hypothesis that accessory flavoenzymes are largely involved in natural product biosynthesis or does it indicate that many fungal biosynthetic processes involving flavoenzymes are not encoded by BGCs? Although it is too early to make a final judgement about this question, flavoenzymes apparently assume other important roles, such as the degradation and detoxification of harmful compounds released into the environment by other species, as exemplified by the putative maackiain detoxification enzyme in N. crassa (Table 2).

Conclusion

Fungi possess a remarkable number of flavoenzymes employed for both basic as well as “secondary” reactions, leading to a plethora of natural products. Most of these reactions and their products remain unidentified, even for N. crassa, which has been investigated as a model organism for many decades. Despite substantial progress in accurately predicting protein structures through computational methods, the reliable assignment of biochemical function lacks far behind and remains a major challenge for many years to come. Clearly, the enormous scope of fungal flavoproteomes requires a joint effort employing biochemical and genetic approaches guided by robust predictions of potential substrates and enzyme reactivities. This endeavor will not only pave the way for the discovery of many more natural products and complex biological interactions but will also enable scientists to tap into this vast reservoir of flavoenzymes with exciting perspectives for applications in biocatalysis.

Methods

Identification and annotation of flavoproteins from N. crassa

In our previous study of selected pro- and eukaryotic flavoproteomes, 156 genes encoding flavoproteins were identified in N. crassa (Supplementary Table S1, (Macheroux et al., 2011). This preliminary list was further refined by a keyword search (dehydrogenase, FAD, flavin, FMN, halogenase, hydroxylase, monooxygenase, oxidase, and reductase) in the MycoCosm database. In addition, we have compiled a list of protein domains associated with FMN or FAD binding (see Supplementary Table S1). These PFam domains were used to search the MycoCosm database to retrieve genes encoding flavoproteins in N. crassa and also in the fungal divisions and classes reported in Table 3. A literature search (PubMed) was performed using the same keywords mentioned above as well as the commonly used names of known flavoproteins based on previous analyses (Macheroux et al., 2011; Lienhart et al., 2013; Gudipati et al., 2014; Eggers et al., 2021).

Structure predictions of BBE-like enzymes from N. crassa

To confirm and assess the structural features and domains of all identified BBE-like enzymes from N. crassa (Table 2), we used AlphaFold2 (Jumper et al., 2021) to predict their 3D structures because of the lack of available crystal structures. We used AlphaFold2 via the Collaboratory service from Google Research (https://colab.research.google.com/github/sokrypton/ColabFold/blob/main/beta/AlphaFold2_advanced.ipynb). The sequence of each BBE-like enzyme was submitted to AlphaFold2, and as a first step, a multiple sequence alignment was performed employing the mmseq2 method (Steinegger and Söding, 2017). Five models per enzyme were predicted and ranked by pLDDT (predicted local distance difference test), a per-residue confidence score. The five predicted models for each enzyme were superimposed on the crystal structure of BBE from E. californica (PDB entry: 3D2D), which was used as a BBE reference model. The model with the lowest Cα-RMSD to the reference model and the highest pLDDT score (i.e., highest confidence) was refined with the Amber-Relax protocol of the AlphaFold pipeline. The resulting model (of each enzyme) was used for structural and visual inspection after trimming regions exhibiting a low pLDDT score (i.e., regions of high uncertainty such as the N- and C-termini). PyMOL (DeLano, 2002) was used for trimming and visual inspection.

Author contributions

BK has retrieved data from the MycoCosm database and generated Figure 3; AB retrieved data from the PDB and generated Figure 1; PM initiated the project, collected data from the MycoCosm database and generated Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, and Figure 2; all three authors have jointly written the paper.

Funding

Austrian Science Fund (FWF) Doc.funds project 46: Catalytic applications of oxidoreductases (CATALOX).

Acknowledgments

We thank the Austrian Research Fund (FWF) for financial support through the doc. fund project “CATalytic AppLications of OXidoreductases” (CATALOX; DOC 46).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fctls.2022.1021691/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

AA3, Auxiliary Activity three; BBE, berberine bridge enzyme; BGC, biosynthetic gene cluster; CDH, cellobiose dehydrogenase; FMO, flavin-containing monooxygenase; FPMO, flavoprotein monooxygenase; GMC, oxidoreductase, glucose-methanol-choline-oxidoreductase; LPMO, lytic polysaccharide monooxygenase; MAK1, maackiain detoxification enzyme one; N. crassa, Neurospora crassa; PCMH, para-cresolmethyl hydroxylase; PFam, Protein Family; S. cerevisiae, Saccharomyces cerevisiae; VAO, vanillyl alcohol oxidase.

References

Beadle, G. W., and Tatum, E. L. (1941). Genetic control of biochemical reactions in Neurospora. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 27 (11), 499–506. doi:10.1073/pnas.27.11.499

Bello, M. H., Barrera-Perez, V., Morin, D., and Epstein, L. (2012). The Neurospora crassa mutant NcΔEgt-1 identifies an ergothioneine biosynthetic gene and demonstrates that ergothioneine enhances conidial survival and protects against peroxide toxicity during conidial germination. Fungal Genet. Biol. 49 (2), 160–172. doi:10.1016/j.fgb.2011.12.007

Büttner, H., Niehs, S. P., Vandelannoote, K., Cseresnyés, Z., Dose, B., Richter, I., et al. (2021). Bacterial endosymbionts protect beneficial soil fungus from nematode attack. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 118, e2110669118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2110669118, no.

Cavener, D. R. (1992). GMC oxidoreductases. J. Mol. Biol. 223 (3), 811–814. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(92)90992-s

Colandene, J. D., and Garrett, R. H. (1996). Functional dissection and site-directed mutagenesis of the structural gene for NAD(P)H-nitrite reductase in Neurospora crassa. J. Biol. Chem. 271 (39), 24096–24104. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.39.24096

Corrochano, L. M. (2007). Fungal photoreceptors: Sensory molecules for fungal development and behaviour. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 6 (7), 725–736. doi:10.1039/b702155k

Covert, S. F., Enkerli, J., Miao, V. P., and VanEtten, H. D. (1996). A gene for maackiain detoxification from a dispensable chromosome of Nectria haematococca. Molec. Gen. Genet. 251 (4), 397–406. doi:10.1007/bf02172367

Daniel, B., Konrad, B., Toplak, M., Lahham, M., Messenlehner, J., Winkler, A., et al. (2017). The family of berberine bridge enzyme-like enzymes: A treasure-trove of oxidative reactions. Archives Biochem. biophysics 632, 88–103. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2017.06.023

DeLano, W. L. (2002) PyMOL [computer program]. Available at: http://www.pymol.org/pymol.

Dorival, J., Risser, F., Jacob, C., Collin, S., Dräger, G., Paris, C., et al. (2018). Insights into a dual function amide oxidase/macrocyclase from lankacidin biosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 9 (1), 3998. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-06323-w

Eggers, R., Jammer, A., Jha, S., Kerschbaumer, B., Lahham, M., Strandback, E., et al. (2021). The scope of flavin-dependent reactions and processes in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytochemistry 189, 112822. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2021.112822

Ewing, T. A., Gygli, G., Fraaije, M. W., and van Berkel, W. J. H. (2020). Vanillyl alcohol oxidase. Enzymes 47, 87–116. doi:10.1016/bs.enz.2020.05.003

Fraley, A. E., and Sherman, D. H. (2018). Halogenase engineering and its utility in medicinal chemistry. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 28 (11), 1992–1999. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2018.04.066

Froehlich, A. C., Liu, Y., Loros, J. J., and Dunlap, J. C. (2002). White Collar-1, a circadian blue light photoreceptor, binding to the frequency promoter. Sci. (New York, N.Y.) 297 (5582), 815–819. doi:10.1126/science.1073681

Funa, N., Awakawa, T., and Horinouchi, S. (2007). Pentaketide resorcylic acid synthesis by type III polyketide synthase from Neurospora crassa. J. Biol. Chem. 282 (19), 14476–14481. doi:10.1074/jbc.m701239200

Galagan, J. E., Calvo, S. E., Borkovich, K. A., Selker, E. U., Read, N. D., Jaffe, D., et al. (2003). The genome sequence of the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa. Nature 422 (6934), 859–868. doi:10.1038/nature01554

Garrett, R. H., and Nason, A. (1967). Involvement of a B-type cytochrome in the assimilatory nitrate reductase of Neurospora crassa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 58 (4), 1603–1610. doi:10.1073/pnas.58.4.1603

Goffeau, A., Barrell, B. G., Bussey, H., Davis, R. W., Dujon, B., Feldmann, H., et al. (1996). Life with 6000 genes. Sci. (New York, N.Y.) 274, 546–547. doi:10.1126/science.274.5287.546

Gorlatova, N., Tchorzewski, M., Kurihara, T., Soda, K., and Esaki, N. (1998). Purification, characterization, and mechanism of a flavin mononucleotide-dependent 2-nitropropane dioxygenase from Neurospora crassa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64 (3), 1029–1033. doi:10.1128/aem.64.3.1029-1033.1998

Gribble, G. W. (2018). Newly discovered naturally occurring organohalogens. Arkivoc 2018 (1), 372–410. doi:10.24820/ark.5550190.p010.610

Gudipati, V., Koch, K., Lienhart, W.-D., and Macheroux, P. (2014). The flavoproteome of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochimica Biophysica Acta - Proteins Proteomics 1844 (3), 535–544. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2013.12.015

Gygli, G., Vries, R., and van Berkel, W. J. H. (2018). On the origin of vanillyl alcohol oxidases. Fungal Genet. Biol. 116, 24–32. doi:10.1016/j.fgb.2018.04.003

Haddad Momeni, M., Fredslund, F., Bissaro, B., Raji, O., Vuong, T. V., Meier, S., et al. (2021). Discovery of fungal oligosaccharide-oxidising flavo-enzymes with previously unknown substrates, redox-activity profiles and interplay with LPMOs. Nat. Commun. 12 (1), 2132. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-22372-0

He, Q., Cheng, P., Yang, Y., Wang, L., Gardner, K. H., and Liu, Y. (2002). White collar-1, a DNA binding transcription factor and a light sensor. Sci. (New York, N.Y.) 297 (5582), 840–843. doi:10.1126/science.1072795

Huschka, H., Naegeli, H. U., Leuenberger-Ryf, H., Keller-Schierlein, W., and Winkelmann, G. (1985). Evidence for a common siderophore transport system but different siderophore receptors in Neurospora crassa. J. Bacteriol. 162 (2), 715–721. doi:10.1128/jb.162.2.715-721.1985

Jumper, J., Evans, R., Pritzel, A., Green, T., Figurnov, M., Ronneberger, O., et al. (2021). Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596 (7873), 583–589. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2

Kracher, D., Scheiblbrandner, S., Felice, A. K. G., Breslmayr, E., Preims, M., Ludwicka, K., et al. (2016). Extracellular electron transfer systems fuel cellulose oxidative degradation. Sci. (New York, N.Y.) 352 (6289), 1098–1101. doi:10.1126/science.aaf3165

Kutchan, T. M., and Dittrich, H. (1995). Characterization and mechanism of the berberine bridge enzyme, a covalently flavinylated oxidase of benzophenanthridine alkaloid biosynthesis in plants. J. Biol. Chem. 270 (41), 24475–24481. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.41.24475

Lafferty, M. A., and Garrett, R. H. (1974). Purification and properties of the Neurospora crassa assimilatory nitrite reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 249 (23), 7555–7567. doi:10.1016/s0021-9258(19)81274-7

Lajin, B., Braeuer, S., Borovička, J., and Goessler, W. (2021). Is the water disinfection by-product dichloroacetic acid biosynthesized in the edible mushroom Russula nigricans? Chemosphere 281, 130819. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.130819

Lienhart, W.-D., Gudipati, V., and Macheroux, P. (2013). The human flavoproteome. Archives Biochem. biophysics 535 (2), 150–162. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2013.02.015

Macheroux, P., Kappes, B., and Ealick, S. E. (2011). Flavogenomics--a genomic and structural view of flavin-dependent proteins. FEBS J. 278 (15), 2625–2634. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08202.x

Matsushita, T., Kishimoto, S., Hara, K., Hashimoto, H., and Watanabe, K. (2020). Structural and functional analyses of a spiro-carbon-forming, highly promiscuous epoxidase from fungal natural product biosynthesis. Biochemistry 59 (51), 4787–4792. doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.0c00896

Mistry, J., Chuguransky, S., Williams, L., Qureshi, M., Salazar, G. A., Sonnhammer, E. L. L., et al. (2021). Pfam: The protein families database in 2021. Nucleic acids Res. 49 (D1), D412–D419. doi:10.1093/nar/gkaa913

Muñoz, V., Brody, S., and Butler, W. L. (1974). Photoreceptor pigment for blue light responses in Neurospora crassa. Biochem. Biophysical Res. Commun. 58 (1), 322–327. doi:10.1016/0006-291x(74)90930-9

Niedermann, D. M., and Lerch, K. (1990). Molecular cloning of the L-amino-acid oxidase gene from Neurospora crassa. J. Biol. Chem. 265 (28), 17246–17251. doi:10.1016/s0021-9258(17)44895-2

Paul, C. E., Eggerichs, D., Westphal, A. H., Tischler, D., and van Berkel, W. J. H. (2021). Flavoprotein monooxygenases: Versatile biocatalysts. Biotechnol. Adv. 51, 107712. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2021.107712

Podzelinska, K., Latimer, R., Bhattacharya, A., Vining, L. C., Zechel, D. L., and Jia, Z. (2010). Chloramphenicol biosynthesis: The structure of CmlS, a flavin-dependent halogenase showing a covalent flavin-aspartate bond. J. Mol. Biol. 397 (1), 316–331. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2010.01.020

Shoyama, Y., Tamada, T., Kurihara, K., Takeuchi, A., Taura, F., Arai, S., et al. (2012). Structure and function of ∆1-tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA) synthase, the enzyme controlling the psychoactivity of Cannabis sativa. J. Mol. Biol. 423 (1), 96–105. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2012.06.030

Sikora, L., and Marzluf, G. A. (1982). Regulation of L-amino acid oxidase and of D-amino acid oxidase in Neurospora crassa. Molec. Gen. Genet. 186 (1), 33–39. doi:10.1007/bf00422908

Sirikantaramas, S., Morimoto, S., Shoyama, Y., Ishikawa, Y., Wada, Y., Shoyama, Y., et al. (2004). The gene controlling marijuana psychoactivity: Molecular cloning and heterologous expression of delta1-tetrahydrocannabinolic acid synthase from cannabis sativa L. J. Biol. Chem. 279 (38), 39767–39774. doi:10.1074/jbc.m403693200

Steinegger, M., and Söding, J. (2017). MMseqs2 enables sensitive protein sequence searching for the analysis of massive data sets. Nat. Biotechnol. 35 (11), 1026–1028. doi:10.1038/nbt.3988

Sygmund, C., Kracher, D., Scheiblbrandner, S., Zahma, K., Felice, A. K. G., Harreither, W., et al. (2012). Characterization of the two Neurospora crassa cellobiose dehydrogenases and their connection to oxidative cellulose degradation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78 (17), 6161–6171. doi:10.1128/aem.01503-12

Tan, T.-C., Kracher, D., Gandini, R., Sygmund, C., Kittl, R., Haltrich, D., et al. (2015). Structural basis for cellobiose dehydrogenase action during oxidative cellulose degradation. Nat. Commun. 6, 7542. doi:10.1038/ncomms8542

Teufel, R., Miyanaga, A., Michaudel, Q., Stull, F., Louie, G., Noel, J. P., et al. (2013). Flavin-mediated dual oxidation controls an enzymatic Favorskii-type rearrangement. Nature 503 (7477), 552–556. doi:10.1038/nature12643

Toplak, M., and Teufel, R. (2022). Three rings to rule them all: How versatile flavoenzymes orchestrate the structural diversification of natural products. Biochemistry 61 (2), 47–56. doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.1c00763

Uehling, J., Gryganskyi, A., Hameed, K., Tschaplinski, T., Misztal, P. K., Wu, S., et al. (2017). Comparative genomics of Mortierella elongata and its bacterial endosymbiont Mycoavidus cysteinexigens. Environ. Microbiol. 19 (8), 2964–2983. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.13669

Vaaje-Kolstad, G., Westereng, B., Horn, S. J., Liu, Z., Zhai, H., Sørlie, M., et al. (2010). An oxidative enzyme boosting the enzymatic conversion of recalcitrant polysaccharides. Sci. (New York, N.Y.) 330 (6001), 219–222. doi:10.1126/science.1192231

Wang, C., Lu, H., Lan, J., Zaman, K. H. A. U., and Cao, S. (2021). A review: Halogenated compounds from marine fungi. Mol. Basel, Switz. 26, 1–21. doi:10.3390/molecules26020458

Welch, G., Cole, K. W., and Gaertner, F. H. (1974). Chorismate synthase of Neurospora crassa: A flavoprotein. Archives Biochem. biophysics 165 (2), 505–518. doi:10.1016/0003-9861(74)90276-8

Westermark, U., and Eriksson, K.-E.. (1974). Cellobiose: Quinone Oxidoreductase, a new wood-degrading enzyme from white-rot fungi. Acta Chem. Scand., 209–214. doi:10.3891/acta.chem.scand.28b-0209

Westphal, A. H., Tischler, D., and van Berkel, W. J. H. (2021). Natural diversity of FAD-dependent 4-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylases. Archives Biochem. biophysics 702, 108820. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2021.108820

Winkler, A., Lyskowski, A., Riedl, S., Puhl, M., Kutchan, T. M., Macheroux, P., et al. (2008). A concerted mechanism for berberine bridge enzyme. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4 (12), 739–741. doi:10.1038/nchembio.123

Zhang, R., Fan, Z., and Kasuga, T. (2011). Expression of cellobiose dehydrogenase from Neurospora crassa in Pichia pastoris and its purification and characterization. Protein Expr. Purif. 75 (1), 63–69. doi:10.1016/j.pep.2010.08.003

Keywords: dehydrogenase, flavin, halogenase, monooxygenase, natural product (bio)synthesis, Neurospora crassa, oxidase, reductase

Citation: Kerschbaumer B, Bijelic A and Macheroux P (2022) Flavofun: Exploration of fungal flavoproteomes. Front. Catal. 2:1021691. doi: 10.3389/fctls.2022.1021691

Received: 17 August 2022; Accepted: 16 November 2022;

Published: 14 December 2022.

Edited by:

Dirk Tischler, Ruhr University Bochum, GermanyReviewed by:

Florian Rudroff, Vienna University of Technology, AustriaDietmar Haltrich, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna, Austria

Willem JH Van Berkel, Wageningen University and Research, Netherlands

Andrea Mattevi, University of Pavia, Italy

Copyright © 2022 Kerschbaumer, Bijelic and Macheroux. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Peter Macheroux, cGV0ZXIubWFjaGVyb3V4QHR1Z3Jhei5hdA==

Bianca Kerschbaumer

Bianca Kerschbaumer Aleksandar Bijelic

Aleksandar Bijelic Peter Macheroux

Peter Macheroux