Abstract

Introduction:

Digital Health Interventions (DHIs) have been identified as a solution to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG3) for health promotion and prevention. However, DHIs face criticism for shallow and transactional engagement and retention challenges. Integrating DHIs with health coaching represents a promising solution that might address these issues by combining the scalable and accessible nature of DHIs with the meaningful and engaging nature of health coaching. This systematic review aims to synthesise existing peer-reviewed research on coach-facilitated DHIs to understand how digital health coaching is being used in DHIs and the impact it has on engagement and lifestyle outcomes.

Methods:

Studies examining DHIs with a coaching component addressing lifestyle outcomes were included. A search of APA PsychINFO, Medline, Web of Science, and Scopus was performed from inception to February 2025. Three authors conducted the study selection, quality appraisal using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), and data extraction. Data extraction captured study characteristics, coaching features, participant engagement, and lifestyle outcomes.

Results:

Thirty-five studies were identified and synthesised using a narrative synthesis approach. This review highlights three coaching modalities in DHIs: digital human coaching, Artificial Intelligence (AI) coaching, and hybrid (human-AI) coaching. All coaching modalities demonstrated feasibility and acceptability.

Discussion:

While both human and AI coaching have shown a positive impact on both engagement and lifestyle outcomes, hybrid approaches need further refinement to harness AI's scalability and the depth of human coaching. However, the variability of engagement metrics and coaching protocols limited study comparability. Standardising how engagement and coaching delivery are measured and contextualised is crucial for advancing evidence-based digital health coaching. This review followed PRISMA guidelines and was registered in PROSPERO (Registration number: CRD42022363279). The Irish Research Council supported this work.

Systematic Review Registration:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42022363279, identifier: CRD42022363279.

1 Introduction

The United Nations (UN) has developed a universal agenda for sustainable development, with the overarching vision for all human beings to thrive and to reach their full potential in dignity and equality in a healthy environment (1). The third goal (SDG3) of this agenda is to “ensure healthy lives and promote wellbeing for all at all ages” (1). Under this goal, the UN emphasised reducing noncommunicable disease (NCD)-related mortality rates by one-third through prevention and treatment and promoting mental health and wellbeing (1). Digital health has been identified as a feasible, accessible and affordable solution to the UN goals of preventing NCDs and promoting health and wellbeing (2). Digital health is a complex and multifaceted field of both knowledge and practice, focused on the development and use of various technologies (i.e., smart watches, digital tracking tools, robotics, artificial intelligence and machine learning) for improving health (2–4). There has been substantial growth in the field of digital health research, especially in terms of evidence-based digital health interventions (DHIs) (5).

DHIs create new opportunities for medical doctors, health professionals and other caregivers to scale and tailor health and lifestyle interventions at a lower cost (5). DHIs are particularly effective for promoting healthy lifestyle behaviours like healthy eating, physical activity, stress reduction and psychological wellbeing (6–10). These behaviours, in turn, can promote healthier living and aid in the prevention and management of lifestyle-related NCDs such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, certain cancers and chronic respiratory diseases (4, 5, 11–13). However, challenges exist in DHI implementation, particularly with self-guided or automated interventions. Despite their low cost and scalability, these interventions are often perceived as shallow, impersonal, and transactional, with participants preferring human support for more meaningful engagement (4, 14–17). Retention and engagement also pose significant issues, with a pooled estimated dropout rate of 43% across DHIs (18–20).

Integrating health coaching with DHIs may offer a solution to the limitation of passive or automated interventions by providing live and engaging support to participants. Health coaching is a non-clinical, evidence-based health promotion intervention that promotes sustainable health behaviours and improves lifestyle outcomes through personalised, solution-focused, person-centred support. By tailoring interventions to individual needs and fostering a collaborative relationship, health coaching empowers clients to make informed decisions about their health and facilitates behaviour change (21–23). Health coaching is already recognised as a valuable asset to healthcare systems. Specifically, for the health promotion and prevention of NCDs (24, 25). As such, health coach-facilitated DHIs could create meaningful yet scalable and accessible digital health solutions for health promotion and NCD prevention (26–28).

This integration paves the way for a new field of research relating to digital health coaching. There has already been a substantial surge of professional coaches transitioning to digital spaces, with 93.3% of coaches globally transitioning to online coaching (29). In the digital space, health coaching is mediated through technology, where coaches interact with coachees via digital platforms to guide behaviour change (30). This allows coaches and clients to interact regardless of geographical location and through different modalities (i.e., through text, video call or phone call) (31). While the conversation between coaches and clients remains central to digital health coaching, it can be supported by a variety of technologies, including digital tracking tools (i.e., smart watches, glucose monitors), self-guided educational modules, habit tracking and automated reminders. Additionally, recent advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) have spurred research into conversational agent coaching or chatbot coaches as flexible, accessible and cost-efficient alternatives to human-facilitated digital health coaching (32, 33). Chatbots are AI-driven programmes designed to interact with individuals using natural language that mimics human dialogue through algorithm-generated responses (34). However, the active engagement between the coach (AI or human) and coachee through personalised and real-time interaction is central to digital health coaching.

While there has been increasing interest in the integration of coaching within DHIs, a clear gap remains in understanding the impact of different coaching modalities (e.g., human, AI, and hybrid) on participant engagement and health outcomes. Although some studies have investigated coach-facilitated DHIs, comprehensive analyses and synthesis regarding the effectiveness of these modalities, particularly their role in enhancing lifestyle behaviours and preventing NCDs, are limited. This systematic review aims to synthesise existing research on coach-facilitated DHIs to understand how digital health coaching is being used in DHIs and the impact it has on lifestyle outcomes and engagement. Ultimately, this review seeks to provide evidence to inform the development of future digital health interventions and research.

2 Materials and methods

The methodology for this systematic review complies with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for systematic reviews (35) (Supplementary File S1). This protocol has been registered on PROSPERO (Registration number: CRD42022363279). After registration, amendments were made to enhance the comprehensiveness of the review. The review timeline was updated to incorporate a more recent search date. Additionally, further details were added to the inclusion criteria to clarify modifications. Lastly, the search strategy was revised to reflect the updated search parameters.

2.1 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The PICO framework guided the definition of eligibility for this review (Table 1). However, in this review, the traditional “Comparator” element in PICO was replaced with “Context”, as this review focuses on the integration of coaching within DHIs without the need for a direct comparator.

Table 1

| PICOS heading | Inclusion and exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Population | Studies involving adults aged 18 or older, including adults with or at risk for NCDs (i.e., cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease). Studies involving children or adolescents were excluded |

| Intervention | DHIs delivered online through a web-based platform or mobile application tailored towards one or more of the six pillars of lifestyle medicine. DHIs were excluded if the DHI was a medical intervention or used as a part of medical or mental health treatments |

| Comparator | Studies that explored coach-facilitated DHIs with an active coaching component, meaning that there is two-way interaction between coach and participants via text, video, or phone calls. Non-interactive coaching interventions were excluded. This coaching component could be health, lifestyle, or wellbeing coaching delivered by a human coach or conversational agent. Studies focusing on in-person, career/executive, or athletic coaching were excluded |

| Outcomes | Studies were included if they reported at least one of the pillars of lifestyle as its primary outcome. Studies were excluded if their primary outcomes were clinical or biomedical |

| Study design | Only peer-reviewed studies were included, with no publication date restrictions. Non-English studies were excluded due to language limitations |

PICOS framework for study inclusion and exclusion.

This review seeks to gather evidence of coach-facilitated DHIs implemented to increase the health and wellbeing of populations. While this largely falls into preventative interventions to help reduce the risk of NCDs, substantial studies are using coach-facilitated DHIs to help increase the health and wellbeing of cohorts living with NCDs (predominantly cancers and diabetes). It would be remiss to exclude these cohorts because of their disease status, despite the intervention aligning with inclusion criteria. As a result, we included adults living with NCDs once the primary outcomes were focused on lifestyle outcomes and not clinical or medical outcomes or markers (i.e., HbA1c, Cholesterol, BMI, weight reduction or waist circumference). This review concentrated on the adult population (18 years and older). As such, studies involving adolescents or children were excluded.

Peer-reviewed studies were considered if they explored digital coaching in DHIs and addressed at least one of the lifestyle medicine pillars: sleep, physical activity, psychological wellbeing and stress management, substance use, or healthy eating. Studies were excluded if they focused on medical interventions or used coaching as a part of medical or mental health treatments (i.e., coaching for patient education, trust building for treatments, pain management, medication adherence) that were not directly aimed at increasing lifestyle or wellbeing outcomes. Similarly, studies with clinical primary outcomes or biological markers as the primary outcome were excluded.

Studies that incorporated human, AI or hybrid (AI and human) coaching components alongside DHIs were included. For the inclusion criteria, digital health coaching was defined as a coach-coachee partnership facilitated online with the purpose of providing tailored support to enhance the DHI and promote behaviour change and health outcomes among participants. The coaching component of the DHI must align with this definition, meaning that coaching through ad hoc non-interactive messages or notifications was excluded. Studies that explored in-person or face-to-face interventions only, as well as career, executive or athletic coaching, were excluded. Finally, all peer-reviewed studies from any country were included, and no publication date limit was applied, given the limited literature on coaching, especially digital coaching. Studies that were not available in English were excluded.

2.2 Search strategy

The search strategy used keywords identified through an initial review of the literature. Keywords were grouped using Boolean operators and truncations. The PICO Framework also guided the formation of the final search strategy (Table 2).

Table 2

| Population | Intervention | Context | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult* | “digital health” OR “eHealth” OR “mHealth” OR “mobile health” OR “digital intervention” OR “mobile application” OR “smartphone application” OR “health app” OR “internet intervention” OR “online program” OR “web-based intervention” | “coaching” OR “health coaching” OR “digital coaching” OR “lifestyle coaching” OR “motivational coaching” OR “chatbot” OR “artificial intelligence” “AI chatbot” OR “virtual coaching” OR “AI Coach” OR “automated coaching” OR “health coach” OR “coaching psychology” OR “digital health coach” OR “conversational agent” | “engagement” OR “adherence” OR “participation” OR “user engagement” OR “user adherence” OR “retention” OR “satisfaction” OR “user satisfaction” OR “acceptability” OR “usability” OR “lifestyle” OR “healthy lifestyle” “lifestyle change” OR “wellbeing” OR “healthy living” OR “behaviour change” OR “habit*” OR “Healthy eating” OR “physical activity” OR “nutrition” OR “weight management” OR “stress management” OR “sleep quality” OR “active minutes” |

| And not | “Adolescent*” OR “child*” OR “clinical outcome” OR “treatment” OR “rehab*” OR “athlet*” OR “sports coach*” OR “performance coach*” OR “clinical treatment” | ||

Final search strategy using the PICO framework.

* denotes a truncation operator, used to search for word variations or endings.

2.3 Informational sources

We conducted searches in electronic databases, including APA PsychINFO, Medline, Web of Science, and Scopus, on February 1, 2025. In addition to the electronic database searches, backward and forward citation searching of included studies was conducted to identify any additional relevant studies. Furthermore, forward searching of protocols deemed relevant during screening was carried out to ensure the inclusion of studies that may have been missed in the initial search.

2.4 Study screening

Covidence, an online specialised systematic review website, was used to screen studies. One reviewer (CL) screened the titles and abstracts of the identified studies based on the eligibility criteria. Three reviewers (CL, ROD, and JL) then independently reviewed the identified full-text studies. Reviewers met to discuss and resolve any conflicts or disagreements. If consensus could not be reached, a fourth reviewer (PJD) was designated to assess the relevant records. Three reviewers are qualified health coaches accredited by the European Mentoring and Coaching Council (EMCC). Two reviewers hold psychology degrees (CL, ROD), and the fourth reviewer holds a PhD in immunology and a degree in counselling and psychotherapy (PJD). The third reviewer (JL) has a biomedical engineering degree with specific expertise in digital health research.

2.5 Data extraction process

Two reviewers (CL & ROD) independently extracted the data using the Covidence Data Extraction template. To resolve discrepancies in the data extracted, reviewers came together to review data extraction and any existing conflicts. Conflicts that couldn't be resolved were referred to a third reviewer for resolution (PJD). However, this was not needed. The following characteristics were recorded: author, year, study aim, participant description and inclusion and exclusion status, total participant number, study design, lifestyle focus, measures taken, key outcomes, coaching delivery and intensity, coaching theory, role of coaching, length of intervention, and limitations.

2.6 Quality assessment

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool assessed the quality of all studies included in the systematic review. This was conducted independently by two reviewers (CL and ROD), who then jointly reviewed independent quality appraisal for any conflicts. Unresolved conflicts were referred to a third reviewer (PJD), though this step was not needed. The final MMAT results are included in the supplementary files (Supplementary File S2).

2.7 Study synthesis

The identified studies were synthesised using a narrative synthesis in relation to the study question: How is digital health coaching used in DHIs, and what is the impact of lifestyle outcomes and engagement? The synthesis followed the steps outlined by Popay (36), which included: becoming familiar with the studies, organising them into logical categories, comparing and synthesising the studies, exploring the relationships within and between the studies and synthesising the data under the relevant themes. Studies included in this review were first grouped by coaching modality (i.e., human, AI, or hybrid coaching) and then further categorised by targeted lifestyle outcomes (physical activity, psychological wellbeing, stress management, healthy eating, sleep, and substance use) and engagement outcomes. We evaluated the consistency of the findings across studies to assess the certainty of evidence. Missing or inconsistent data that was not a criterion for inclusion (i.e., engagement statistics, coaching theories, and length of intervention) was noted during synthesis and presented in the results. Studies were not excluded based on these missing data, but it was considered as a limitation during synthesis. A meta-analysis could not be performed due to significant variations in sample populations, outcome measures, and study designs across the included studies.

3 Results

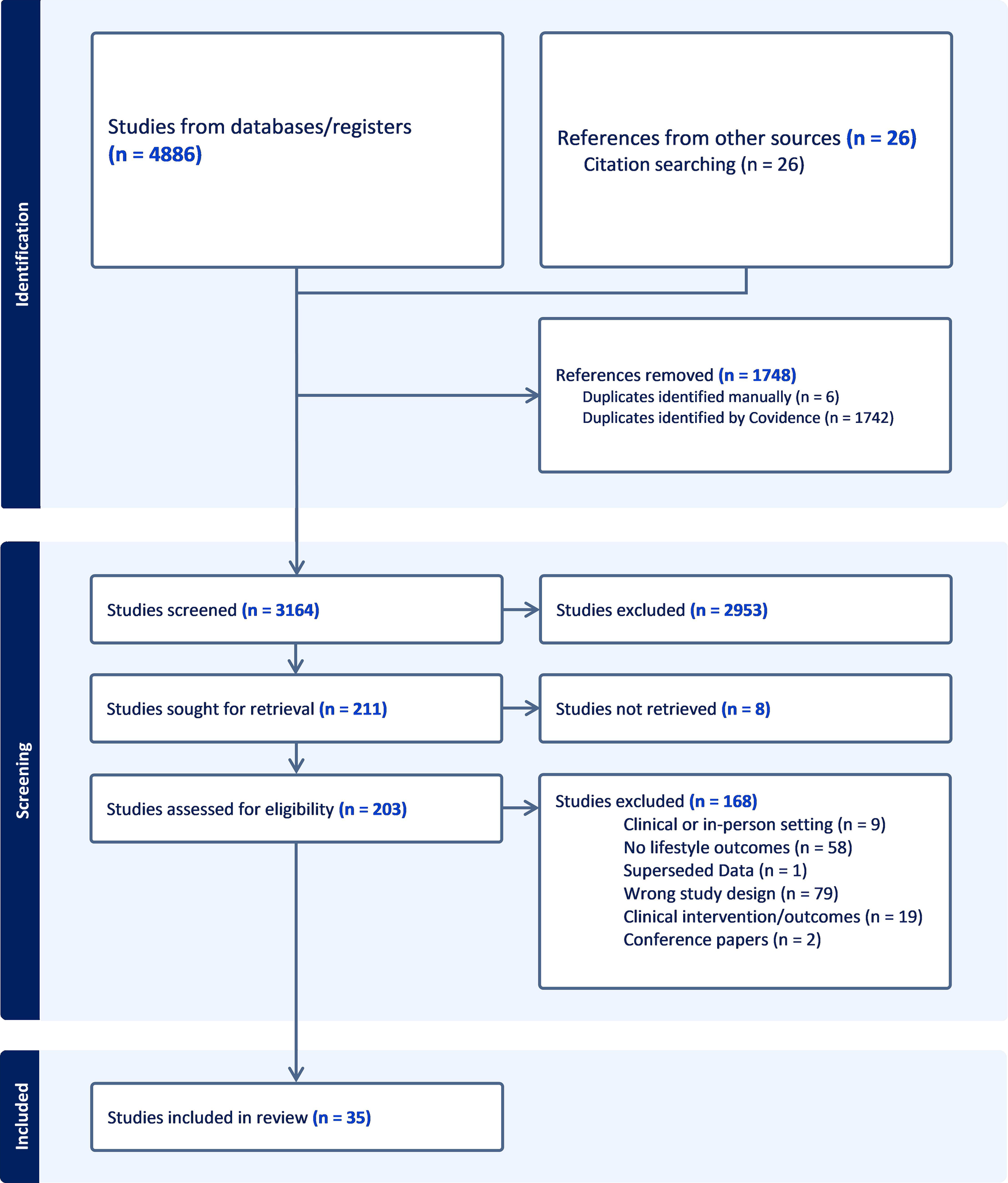

The database search yielded a total of 4,894 studies. After removing 1,748 duplicates, a further 2,936 studies were removed after title and abstract screening. One hundred and seventy-six studies were removed during the full-text review. In total, 35 studies were included in this review. The complete screening process is illustrated through the PRISMA diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1

PRISMA flow diagram for systematic reviews illustrating the study selection process. Adapted with permission from “PRISMA 2020 flow diagram template for systematic reviews”, by Page et al., licensed under CC BY 4.0.

3.1 Quality assessment

No articles were excluded from the review based on the MMAT quality appraisal score (Supplementary File S2). Regarding the methodological rigour of the included articles, 11 studies scored 100% (5/5), and 23 scored 80% (4/5), indicating high quality. Only one study scored 60% (3/5), indicating medium quality. This demonstrates that the majority of studies included in the review met a high standard of methodological rigor.

3.2 Description of the included studies

Thirty-five studies were included for full review and data extraction. Table 3 summarises the study characteristics, including year of publication, country, length of intervention, number of participants, study design, intervention description, lifestyle areas addressed, measures used, and key outcomes. Most of the studies were pilot, feasibility, or early-stage studies, with only seven studies (20.6%) being full-scale randomised controlled trials (37–43). Intervention lengths ranged from 1 week to 12 months, and sample sizes ranged from 7 to 3,629 participants (Table 3).

Table 3

| Author | Year | Country | Length | Participants | Study design | Intervention | Lifestyle pillars | Measures | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alley et al. (44) | 2,016 | Australia | 8 weeks | 84 adults | Randomised controlled trial | Web-based physical activity intervention + video-based coaching |

|

Self-report measures:

|

Increased physical activity: Tailoring + coaching (+150 min/week), Tailoring only (+123 min/week), Waitlist (+34 min/week). Significant mental health improvement in tailoring + video-coaching group only (P = .01) |

| Aymerich-Franch and Ferrer (17) | 2022 | Spain | 3 weeks | 32 adults | Nonrandomised controlled trial | Coaching programme delivered by a speech-based conversational agent (CAC) |

|

Self-report measures:

|

Significant increase in PGI (Pilot: t = 5.28, P = .013; main study: t = 3.84, P = .001). Moderate and significant increase in SLS (Pilot: t = 2.12, P = .124; main study: t = 4.99, P < .001). Moderate and significant decrease in negative affect (pilot: t = 2.37, P = .098; main study: t = 4.31, P < .001) |

| Bakas et al. (45) | 2018 | USA | 3 weeks | 22 older adults | Quasi-experimental design | A nurse-led intervention delivered through a telepresence robot for healthy independent living |

|

|

Intervention group saw a decline in unhealthy days (3.6 to 1.0 vs. control: 3.4 to 2.3). Slight decline in depressive symptoms (10.1 to 9.6 vs. control worsening to 10.6). Self-efficacy increased (8.2 to 9.1 vs. control: 8.8 to 8.4). Physical activity decreased slightly in both groups. Physical activity minutes declined for the intervention group (163.6 to 128.6 min/week) and slightly decreased for the waitlist control group (159 to 152.8 min/week) |

| Blair et al. (46) | 2021 | USA | 13 weeks | 54 older adults | Randomised controlled trial | Jawbone UP2 activity monitor paired with a smartphone app + tech support (control) or health coaching via phone call (intervention) |

|

Wearable device measures:

|

No significant change in sedentary time: tech support group changed by 6.0 min (95% CI −39.5 to 51.6; P = .79), health coaching by 7.9 min (95% CI −30.8 to 46.6; P = .68). Steps/day increased significantly in the health coaching group (+1,675, P = .009) but not in the tech support group (+654, P = .37). Moderate-intensity physical activity increased significantly in the coaching group (P = .008), compared to control group (P = .33). No significant difference in SPPB scores |

| Chang et al. (47) | 2023 | USA | 3 weeks | 15 mothers | A single-group pre-test post-test study | Web-based lessons + health coaching sessions |

|

Self-report measures:

|

Sugar intake decreased (21.07 to 12.53 tsp, d = 0.48, P = 0.126). Fruit/vegetable intake increased (4.73–5.55 cups, d = 0.49, P = 0.138). Physical activity showed minor improvement (107–171.5 METs, d = 0.13, P = 0.67). Stress reduced (18.33 to 14.67, d = -0.52, P = 0.097). Emotional control significantly improved (38.50–42.58, d = 0.71, P = 0.032). Motivation and self-efficacy improved across all domains. Motivation improved across all domains (healthy eating: P = 0.025; physical activity: P = 0.021; stress: P = 0.011). Self-efficacy increased for healthy eating only (P = 0.058) |

| Chew et al. (48) | 2024 | Singapore | 1 week | 251 adults | A single-group pre-test post-test study | AI–assisted weight management app with a chatbot-based check-in system, food-based computer vision image recognition and automated nudges |

|

Self-report measures:

|

Statistically significant improvements in the overeating habit (P < .001), snacking habit (P = .02 - < .001), self-regulation of eating behaviour (P = .007), depression (p = .007), and physical activity (P < .001). Qualitative themes: increased self-monitoring, personalised reminders, food logging with image recognition, and engaging user interface |

| Chow et al. (27) | 2020 | USA | 6 weeks | 19 women cancer survivors | A single-group pre-test post-test study | iCanThrive, an app app-based intervention with eight educational modules + phone coaching |

|

Self-report measures:

|

Significant reduction in depressive symptoms (t = 2.22 and P = 0.04), slight increase in emotional self-efficacy (t = 1.33, P = 0.20), significant reduction in sleep disturbance (t = 3.41 and P = .003.). Continued significant difference in sleep disruption from baseline to the 4-week follow-up (t = 3.71; P = .002) |

| Daley et al. (49) | 2020 | Brazil | 1 month | 3,629 adults | A single-group pre-test post-test study | Vitalk, a mental health chatbot |

|

Self-report measures:

|

Significant reduction in depressive symptoms (d = 0.91, P = 0.001). 46.3% of users moved below the clinical cut off for PHQ-9. Significant anxiety reduction (d = -0.85, P = 0.001) and stress reduction (d = -0.81, P = 0.001), 49.0% of users moved from above to below the clinical cut-off for anxiety (GAD-7 score ≤ 8) |

| Damschroder et al. (37) | 2020 | USA | 12 months | 358 veterans | Randomised controlled trial | StayStrong app, activity monitoring using wearable devices + telephone health coaching |

|

Wearable device measures:

|

Both groups showed a decline in active minutes (intervention: −41 min; control: −65 min) and step count (intervention: −1933; control: −2427). No significant difference between intervention and control at 12 months for active Minutes (P = .48) or step counts (P = .08) |

| D'Avolio et al. (50) | 2023 | USA | 8 weeks | 26 Dyads | Randomised controlled trial | Telehealth coaching program including nutritional education, stress-reduction material and coaching materials |

|

Self-report measures:

|

Protein intake increased significantly in the coached group (1.00 ± 0.17–1.35 ± 0.23 g/kg) vs. the not-coached (0.91 ± 0.19–1.01 ± 0.33 g/kg, P = .01, η² = .24). No significant effect of protein intake in FMWD. No significant changes in MCSI, SF36 physical component scale and mental component scale, or fatigue |

| Dhinagaran et al. (51) | 2021 | Singapore | 4 weeks | 52 adults | Single-arm feasibility study | Conversational agent promoting healthy lifestyle changes |

|

Self-report measures:

|

Vegetable intake increased from 27% to 29% consuming vegetables at least once a day. Fruit intake increased from 3% to 7% (at least three portions). Participants who never consumed sweetened beverages increased from 38% to 45%. Participants who never consumed fried food and snacks increased from 25% to 30%. The stress score was reduced from 17 to 16. Sleep quality did not change significantly. Physical activity increased from 30 to 50 min/week. Time spent sitting reduced from 439 to 406, and METs per week score went from 857 to 765. Time in moderate to vigorous activity increased from 30 min per week at baseline to 50 min at follow-up |

| Foran et al. (38) | 2024 | USA | 1 month | 1,345 adults | Randomised controlled trial | Zenny—conversational agent designed to enhance wellbeing |

|

Self-report measures:

|

Significant improvements in wellbeing (control: d = 0.24, P < .001; intervention: d = 0.26, P < .001), psychological flourishing (intervention: d = 0.19, P < .001; control: d = 0.18, P < .001), and positive psychological health (intervention: d = 0.17, P = .001; control: d = 0.24, P < .001). No significant differences in effectiveness between groups |

| Gabrielli (52) | 2021 | Italy | 4 weeks | 71 students | Proof of concept study | Atena—a psychoeducational chatbot supporting stress management |

|

Self-report measures:

|

Significant reduction in anxiety symptoms (t39 = 0.94; P = .009), stress symptoms (t39 = 2.00; P = .05), and increase in mindfulness (P < .001) |

| Gudenkauf et al. (53) | 2024 | USA | 8 weeks | 13 caregivers | Single-arm pilot feasibility trial | DHI involving monitoring and visualising health-promoting behaviours and health coaching |

|

Self-report measures:

|

Most participants showed improvement or maintenance of QOL (15% and 62%), sleep quality (23% and 62%), social engagement (23% and 69%), and general self-efficacy (23% and 62%). Physical activity outcomes were not reported |

| Han et al. (39) | 2024 | Singapore | 6 months | 148 adults | Randomised controlled trial | nBuddy Diabetes app, including features for diet, physical activity, behaviour change, blood glucose monitoring and health coaching |

|

Self-report measures:

|

Significant improvement in diet quality by 6.2 points (95% CI, 3.8–8.7; P < .001) in the intervention group compared with control. Significant reduction in intake of sugar-sweetened beverages (−0.5 servings/day, 95% CI, −0.8, −0.2; P < .001) and sodium (−726 mg/day, 95% CI, −983, −468; P < .001) |

| Heber et al. (40) | 2016 | Germany | 7 weeks | 264 adults | Randomised controlled trial | Guided web and mobile-based stress management training + written feedback on every completed session from an e-coach |

|

Self-report measures:

|

Large effects observed for perceived stress (P < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.83), depression (d = 0.95, P < .001), anxiety (d = 0.84, P < .001), and worry (d = 0.63, P < .001). Mental health scores improved significantly (d = 0.68, P < .001). Effects maintained at 12-month follow-up |

| Horn et al. (54) | 2023 | USA | 12 months | 26 women | Qualitative study | Balance after baby—web-based educational modules and lifestyle coaching |

|

|

Participants reported changes in diet and physical activity as a result of the intervention. Online modules and support from the lifestyle coach were perceived to have had a positive effect on personal and familial lifestyle change. Other components were less utilised, including the community forum, gym memberships, and pedometers |

| Ly, Ly and Andersson (55) | 2017 | Sweden | 2 weeks | 28 adults | Randomised controlled trial | Smartphone app with an automated chatbot |

|

Self-report measures:

|

Participants who adhered to the intervention (n = 13): significant effects for FS (F1, 27 = 5.12, P = 0.032), PSS-10 (F1, 27 = 4.30, P = 0.048). No significant effect for SWLS [F (1, 27) = 2.83, P = 0.10]. Within-group effects: PSS-10 [t (12) = 2.22, P = 0.046, d = 0.87] and SWLS [t (12) = -2.25, P = 0.044, d = 0.41] showed medium-to-large improvements in the intervention group |

| Maher et al. (56) | 2020 | Australia | 12 weeks | 31 adults | Case-control study | Artificial intelligence virtual health coach-led physical activity and diet intervention |

|

Self-report measures:

|

Participants increased physical activity by 109.8 min/week [F (2, 29) = 6.45, P = .005]. Mediterranean diet scores improved from 3.8 to 9.6 [F(2,29) = 44.56, P < .001] |

| Marler et al. (57) | 2019 | USA | 18.5 weeks | 319 adults | Prospective open-label single-arm study | Digital smoking cessation program incorporating a Food and Drug Administration, cleared carbon monoxide breath sensor, and text-based human coaching |

|

Self-report measures:

|

Positive changes in attitudes were observed from baseline to Mobilise (pre-Quit): increased confidence to quit (4.2–7.4, P < .001) and decreased expected difficulty maintaining quit (3.1–6.8, P < .001). Quit attempt rate: 79.4% (216/272, completer). 7-day PPA: 32.0%, 30-day PPA: 27.6%. 25.9% achieved ≥50% smoking reduction |

| McGuire et al. (58) | 2022 | Australia | 8 Weeks | 43 midlife adults | Two-arm parallel group feasibility study | GroWell for Health Program—eHealth intervention consisting of an interactive ebook and nurse coaching |

|

Self-report measures:

|

Significant improvements in fruit intake, physical activity stage of change, and exercise habits for arm A (ebook and coaching) and arm b (ebook only) (p < .05).Alcohol frequency decreased for both groups, but this was not significant (arm A: 1.9 to 1.8 days a week, p = 0.65; arm B: 2.7 to 2.5 days a week, P = 0.62) |

| Moreno-Blance et al. (59) | 2019 | Spain | 3 weeks | 20 adults | Feasibility study | mHealth platform with an AI chatbot—Paola, educational material, recipes, diet and activity log |

|

Self-report measures:

|

Participants met sleep goals 47.3% of days and logged moderate to vigorous activity 130% over the target. 10,000-step goal met 122% of the time. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet was not reported |

| Olliers et al. (60) | 2023 | Switzerland | Approx. 6 months | 7,135 Adults | Single-arm interventional study | chatbot-led digital health app designed to provide lifestyle coaching across seven health areas to mitigate the collateral damage of the COVID-19 pandemic |

|

|

Significant decrease in anxiety levels between assessments [t(54) = 3.7, P < 0.001, d = 0.499; Intent-to-treat: t(416) = 3.4, p < 0.001, Cohen d = 0.165]. significant change in depression scores occurred (within group): F2,38 = 7.01, P = 0.003, with a large effect size. Physical activity, sleep and healthy eating did not report significant changes in outcomes between assessments (P = .847; P = .208; P = .837 respectively) |

| Partridge et al. (41) | 2015 | Australia | 12 weeks | 250 adults | Two-arm, parallel-group randomised controlled trial | Mobile app with education, self-monitoring and support resources, motivational text messages and coaching calls |

|

Self-report measures:

|

Intervention group increased vegetable intake (P = .009), reduced sugary drinks (P = .002), and improved physical activity (P = .05). They also increased their total physical activity by 252.5 MET-minutes (95% CI 1.2–503.8, P = .05) and total physical activity by 1.3 days (95% CI 0.5–2.2, P = .003) compared to controls |

| Price and Brunet (61) | 2022 | Canada | 12 weeks | 7 young adults | Single-arm feasibility trial | Telehealth behaviour change intervention |

|

Self-report measures:

|

Participants reported significant increase in physical activity (T0 = 30; T1 = 150; P = 0.018), and fruit and vegetable intake (T0 = 2; T2 = 4.71; P = 0.018). There was also a significant increase in sense of autonomy (P = 0.046), competence (P = 0.018) and relatedness (P = 0.028) relating to fruit and vegetable intake, and a significant increase in autonomy (P = 0.027) and competence (p = 0.28) relating to physical activity. Qualitative data suggests the health coach created an autonomous supported environment, developed capacity for positive connections, and increased motivation |

| Sacher et al. (62) | 2024 | Netherlands | 12 months | 107 adults | Prospective single-arm study | Health coach-led, asynchronous, text-based, Digital Behaviour Change Coaching Intervention (DBCCI) |

|

Self-report measures:

|

WEMWBS scores significantly improved at Month 6 and remained significant at Month 12 (P = .02). GAD-7 scores significantly decreased at Month 1 (P = .009). LOCES significantly decreased at month 1 (P < .001) and remained statistically significant at months 6 and 12 (P < .001). BBAQ scores significantly increased at Month 6 (P < .001) but did not remain significant at Month 12 (P = .45) |

| Santini et al. (63) | 2023 | Italy/Netherlands | 10 weeks | 91 adults | Longitudinal Mixed Methods Study | Digital coaching intervention |

|

Self-report measures:

|

Perceived worsened physical health (SF-12-PCS ≤50) increased from T0 to T2 (p = 0.002), while perceived mental well-being (SF-12-MCS ≤42) remained stable (P < 0.001). Physical activity significantly increased from T0 to T1, then stabilised (P = 0.012), with low activity rates decreasing from 8.2% to 6% during the human coach-supported phase but rising to 8.3% when using the system independently. Self-efficacy and socialisation levels fluctuated over time |

| Smart et al. (64) | 2022 | USA | 8 weeks | 28 adults | A single-group pre-test post-test study | Text-based coaching and Fitbit program |

|

Wearable device measures:

|

There was no significant change in the average weekly steps (mean difference 7.26, SD 6209.3; P = .99), sedentary minutes (mean difference −17.6, 95% CI −67.8 to 32.6), or light (mean difference −3.37, 95% CI −28.8 to 22.1) and moderate to vigorous physical activity (mean difference 6.79, 95% CI −3.4 to 17.0) |

| Spring et al. (42) | 2018 | USA | 9 months | 212 adults | Randomised controlled trial | Multicomponent intervention integrating mHealth, modest incentives, and remote coaching |

|

Self-report measures:

|

Sustained improvement in composite diet and activity score at 3, 6, and 9 months (P < .001). Sequential treatment showed slightly greater improvement at 6 months (P = .03), but no difference at 3 or 9 months compared to simultaneous treatment |

| Terblanche et al. (65) | 2022 | South Africa | 6 months | 168 students | Randomised controlled trial | AI Chatbot Coach |

|

Self-report measures:

|

Psychological wellbeing, resilience and stress showed a medium-sized correlation with each other, ranging from r = .50 to r = -.64 (correlations with stress being negative). The experimental group showed an increase of 55% on their goal attainment compared to 24% in the control group. No statistical significance was found between psychological wellbeing, resilience, stress and time and group (resilience, P = 0.80; psychological wellbeing, P = 0.89; and stress, P = 0.91) |

| To, Green and Vandelanotte (66) | 2021 | Australia | 6 weeks | 116 adults | Quasi-experimental design without control group | Physical activity chatbot and a connected wearable device |

|

Self-report measures:

|

Participants reported an increase in steps from baseline (increase of 627, 95% CI 219–1035 steps/day; P < 0.01) and total physical activity (increase of 154.2 min/week; 3.58 times higher at follow-up; 95% CI 2.28–5.63; P < 0.001). Participants were also more likely to meet the physical activity guidelines (odds ratio 6.37, 95% CI 3.31–12.27; P < 0.001) at follow-up |

| Ulrich et al. (67) | 2024 | Switzerland | 7 weeks | 230 students | Randomised controlled trial | Conversational agent–delivered stress management coaching intervention |

|

Self-report measures:

|

Significant reduction in perceived stress (Cohen d = -0.60, P = .001), depressive and psychosomatic symptoms (Cohen d = -0.50, P = .003; Cohen d = −0.36, P = .010). No significant change in anxiety and active coping (Cohen d = −0.29, P = .08; Cohen d = 0.13, P = .06) |

| Wiegand et al. (68) | 2010 | USA | 14 weeks | 562 women | Longitudinal Study | Internet-based online coaching, education programme and olfactive-based personal care products |

|

Self-report measures:

|

Group 1 (coaching, education programme, and olfactive-based products) had statistically significant improvement in the PSS score vs. Group 3 (control) (P < 0.01). Group 2 (coaching and education programme) demonstrated significantly greater reductions vs. baseline (P < 0.001), but there were no statistically significant differences vs. Group 3. Significant improvements in other efficacy outcomes such as POMS total mood disturbance, TICS work overload and social responsibility subscales, STAI and awakenings, (P < 0.05) |

| Wijsman et al. (43) | 2013 | Netherlands | 3 months | 226 older adults | Randomised controlled trial | Philips DirectLife: monitoring and feedback by accelerometer and digital coaching |

|

Wearable device measures:

|

At the ankle, activity counts increased by 46% [standard error (SE) 7%] in the intervention group, compared to 12% (SE 3%) in the control group (P=<.001). Measured at the wrist, activity counts increased by 11% (SE 3%) in the intervention group and 5% (SE 2%) in the control group (P = .11). After processing of the data, this corresponded to a daily increase of 11 min in moderate-to-vigorous activity in the intervention group vs. 0 min in the control group (P = .001) |

| Williams et al. (69) | 2021 | New Zealand | 21 days | 64 students | Open trial single-arm study | Digital mental health intervention delivered by a chatbot |

|

Self-report measures:

|

WHO-5 scores improved significantly (SD = 15.07; P < 0.001). Mean reduction of the PSS-10 = 1.77 (SD = 4.69; P = 0.004) equating to effect sizes of 0.49 and 0.38, respectively. Those who were clinically anxious at baseline (n = 25) experienced a greater reduction of GAD-7 symptoms than those (n = 39) who started the study without clinical anxiety (1.56, SD = 3.31 vs. 0.67, SD = 3.30; P = 0.011) |

Characteristics of included studies.

To assess the heterogeneity of the participants, demographic information, including sex, age, race, and education, was collected and is presented in Table 4. Participants were predominantly Caucasian, though African American/Black, Asian, multiracial, and other racial groups were represented in smaller proportions. Notably, four studies had a larger representation of African American/Black (47) and Asian participants (39, 48, 51). The mean age of participants varied widely. Participants were largely aged between 40 and 60 years, with the exception of outlying studies focusing on younger adults and students (18–34 years) (47–49, 51, 52, 55, 61, 65, 67, 69) and older populations (60 + years) (38, 43, 45, 46, 50). Women were more frequently recruited for digital health interventions, with female participation ranging from 25.2% to 100% across studies. Education levels were inconsistently reported, but in studies that provided this information, the percentage of participants with a college degree ranged from 20.7% to 95%.

Table 4

| Author | Gender %female | Age (mean) | Age (range) | Race % | College degree (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caucasian | African American/Black | Asian | Multiracial | Other | |||||

| Alley et al. (2016) (44) | 76 | 54.21 | 41.66 | ||||||

| Aymerich-Franch and Ferrer (2022) (17) | 53.3 | 40.47 | 76.7 | ||||||

| Bakas et al. (2018) (45) | 71.4 | 84 | 100 | ||||||

| Blair et al. (2021) (46) | 56 | 69.6 | 57 | 7 | 57 | ||||

| Chang et al. (2023) (47) | 100 | 32.9 | 33.33 | 46.66 | 6.66 | 13.33 | 60 | ||

| Chew et al. (2024) (48) | 52 | 31.25 | 97 | 3 | 95 | ||||

| Chow et al. (2020) (27) | 100 | 59.6 | 94 | 3 | 3 | ||||

| Daley et al. (2020) (49) | 76 | 18–24 | |||||||

| Damschroder et al. (2020) (37) | 25.2 | 39.8 | 64.7 | 13.2 | 22.1 | 93.6 | |||

| D'Avolio et al. (2023) (50) | 92.3 | 66.2 | 84.6 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 7.7 | |||

| Dhinagaran et al. (2021) (51) | 62 | 33.7 | 3 | 93 | 2 | 87 | |||

| Foran et al. (2024) (38) | 80.3 | 47.17 | |||||||

| Gabrielli et al. (2021) (52) | 67.6 | 18–34 | |||||||

| Gudenkauf et al. (2024) (53) | 61.5 | 52 | 28–70 | 69.2 | 23.1 | 7.7 | 76.9 | ||

| Han et al. (2024) (39) | 40 | 53.1 | 92.5 | 7.5 | |||||

| Heber et al. (2016) (40) | 73.1 | 43.3 | 83.3 | 16.7 | 76.9 | ||||

| Horn et al. (2023) (54) | 100 | 34.5 | 65 | 23 | 12 | 23 | 62 | ||

| Ly, Ly and Andersson (2017) (55) | 53.5 | 23.3 | |||||||

| Maher et al. (2020) (56) | 67.7 | 56.2 | |||||||

| Marler et al. (2019) (57) | 57.7 | 30–39 | 82.8 | 6.9 | 1.6 | 81.5 | |||

| McGuire et al. (2022) (58) | 89.2 | 50.6 | 77.7 | ||||||

| Moreno-Blanco et al. (2019) (59) | 33.30 | 30 | |||||||

| Ollier et al. (2023) (60) | 71.3 | 46.3 | |||||||

| Partridge et al. (2015) (41) | 27.7 | 61.3 | 80.6 | ||||||

| Price and Brunet (2022) (61) | 85.7 | 33.8 | 71.4 | ||||||

| Sacher et al. (2024) (62) | 89.7 | 41.8 | 59.9 | 1.9 | 10.3 | ||||

| Santini et al. (2023) (63) | 35.5 | 46.8 | |||||||

| Smart et al. (2022) (64) | 77 | 47.1 | 3 | 80 | 17 | 60 | |||

| Spring et al. (2018) (42) | 76.4 | 40.8 | 41 | 46.7 | 3.8 | 8.5 | 69.3 | ||

| Terblanche et al. (2022) (65) | 56 | 22 | |||||||

| To, Green and Vandelanotte (66) | 81.9 | 49.1 | 87.1 | 12.9 | |||||

| Ulrich et al. (2024) (67) | 73.6 | 26.7 | 26.4 | ||||||

| Wiegand et al. (2010) (68) | 100 | 35.7 | 68.3 | 21.7 | 9.7 | 20.7 | |||

| Wijsman et al. (2013) (43) | 40.9 | 64.8 | 56.7 | ||||||

| Williams et al. (2021) (69) | 81 | 18–23 | 2.4 | ||||||

Participant demographics.

3.3 Presence of coaching in DHIs

This review focused on the role and impact of health coaching in DHIs. Table 5 summarises the key characteristics of coaching that are evidenced across included studies. Coaching was exhibited through two crucial elements: (1) an active coaching component and (2) evidence-based coaching theories. Theories not only guided the coaching process (27, 40–42, 45, 46, 50, 53, 57, 58, 61, 62, 68) but also influenced the overall design of DHIs and AI chatbots (17, 38, 48, 49, 51, 52, 55, 56, 60, 65–67, 69). The active coaching component of DHIs was evident through three different delivery modes: (1) digital human coaching, (2) AI-powered coaching, or (3) a mix of both, which we refer to as hybrid coaching (Table 5). Using the three modes of coaching identified, this review presents the features of coaching, followed by the trends of lifestyle outcomes and engagement that emerged from the included studies.

Table 5

| Author | Coaching approach | Theories/frameworks | Coach qualification disclosed | Number of sessions | Frequency of sessions | Session length | Mode of communicationb | Role in digital health |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alley et al. (2016) (44) | Hybrid |

|

No | 4 | Bi-weekly | 10–15 min | Synchronous | Supportive |

| Aymerich-Franch and Ferrer (2022) (17) | AI |

|

N/Aa | 3 | Weekly | 10–14 min | Synchronous | Central |

| Bakas et al. (2018) (45) | Human |

|

Yes | 3 | Not stated | Not stated | Synchronous | Central |

| Blair et al. (2021) (46) | Human |

|

No | 5 | Not stated | 15–20 min | Synchronous | Supportive |

| Chang et al. (2023) (47) | Human |

|

No | 3 | Not Stated | Not stated | Synchronous | Central |

| Chew et al. (2024) (48) | AI |

|

N/Aa | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Asynchronous | Central |

| Chow et al. (2020) (27) | Human |

|

No | 2 | Monthly | 30 and 5 min | Synchronous/asynchronous | Supportive |

| Daley et al. (2020) (49) | AI |

|

N/Aa | 4–5 | Not stated | 5 min | Synchronous | Central |

| Damschroder et al. (2020) (37) | Hybrid |

|

No | 3 | Over 9 weeks | 30 min | Synchronous | Supportive |

| D'Avolio et al. (2023) (50) | Human |

|

No | 8 | Weekly | 45–60 min | Synchronous | Central |

| Dhinagaran et al. (2021) (51) | AI |

|

N/Aa | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Asynchronous | Central |

| Foran et al. (2024) (38) | ÀI |

|

N/A | Not stated | Daily | Not stated | Asynchronous | Central |

| Gabrielli et al. (2021) (52) | AI |

|

N/Aa | 8 | Bi-weekly | 10 min | Synchronous | Central |

| Gudenkauf et al. (2024) (53) | Human |

|

Yes | 8 | Weekly | 15–20 min | Synchronous | Central |

| Han et al. (2024) (39) | Human | Not stated | Yes | Not stated | ad hoc | Not stated | Asynchronous | Supportive |

| Heber et al. (2016) (40) | Human |

|

Yes | 8 | After educational sessions | Not stated | Asynchronous | Supportive |

| Horn et al. (2023) (54) | Human |

|

Yes | 24 | Weekly for 12 weeks, bi-weekly for 12 weeks and monthly thereafter | Not stated | Synchronous | Supportive |

| Ly et al. (2017) (55) | AI |

|

N/Aa | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Synchronous | Central |

| Maher et al. (2020) (56) | AI |

|

N/Aa | Unlimited | Unlimited | Not stated | Note stated | Central |

| Marler et al. (2019) (57) | Human |

|

No | Not stated | 3 times weekly for the first 30 days, 1 weekly for the next 30 days, and biweekly for the last 30 days | Not stated | Asynchronous | Central |

| McGuire et al. (2022) (58) | Human |

|

Yes | 3 | Week 1, 4, and 8 | 30–60 min | Synchronous | Supportive |

| Moreno-Blanco et al. (2019) (59) | Hybrid |

|

No | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Synchronous asynchronous | Central |

| Ollier et al. (2023) (60) | AI |

|

N/A | Not stated | Not stated | 5–10 min | Synchronous | Central |

| Partridge et al. (2015) (41) | Human |

|

Yes | 5 | Not stated | 10–25 min | Synchronous | Central |

| Price and Brunet (2022) (61) | Human |

|

No | 12 | Weekly | 60 min | Synchronous | Central |

| Sacher et al. (2024) (62) | Human |

|

Yes | Not states | Not stated | Not stated | Asynchronous | Central |

| Santini et al. (2023) (63) | Hybrid | Not stated | No | Not stated | Daily | Not stated | Asynchronous/synchronous | Central |

| Smart et al. (2022) (64) | Human |

|

Yes | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Asynchronous | Central |

| Spring et al. (2018) (42) | Human |

|

Yes | 22 | Weekly (week 1–12), bi-weekly (13–24), monthly (25–40) | 10–15 min | Synchronous | Central |

| Terblanche et al., (2022) (65) | AI |

|

N/Aa | Unlimited | Unlimited | Not stated | Synchronous | Central |

| To et al. (66) | AI |

|

N/Aa | 12 | Every 2 to 4 days | Not stated | Synchronous | Central |

| Ulrich et al. (2024) (67) | AI |

|

N/Aa | Unlimited | Unlimited | Not stated | Asynchronous | Central |

| Wiegand et al. (2010) (68) | Human |

|

No | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Synchronous | Central |

| Wijsman et al. (2013) (43) | Human |

|

No | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Asynchronous | Central |

| Williams et al. (2021) (69) | AI |

|

N/Aa | 21 | Daily | 3–5 min | Synchronous | Central |

Characteristics of coaching.

Not Applicable for AI studies.

Mode of communication is catagorised into synchronous, meaning real-time communication between coach and participant, and asynchronous, meaning communication which is not time-bound or instant.

3.3.1 Digital human coaching

Digital human coaching refers to any study that used a human coach alongside DHIs. Eighteen of the included studies (51%) employed human coaching as a part of their interventions (27, 39–43, 45–47, 50, 53, 54, 57, 58, 61, 62, 64, 68). Coaching was often enhanced with digital tracking tools (e.g., smart scales, watches, accelerometers, and breath sensors) (41–43, 46, 53, 57, 58, 62, 64) and educational resources or modules (27, 39–41, 47, 50, 54, 58, 61, 62, 68). One study used a telepresence robot controlled remotely by practitioners to facilitate communication with participants (45). A consistent finding emerged from these studies: the human coach played a crucial role in engaging participants and enhancing motivation, adherence, behaviour change, and personalisation (39, 46, 58, 61, 62). However, the intensity of human coaching delivered varied. In most cases (67%), the coach was central to the intervention, interacting regularly with participants. In contrast, six studies assigned coaches a more supportive role, primarily supplementing educational modules, training, and activity monitors (27, 39, 40, 46, 54, 58). In these instances, participants primarily engaged with the digital components and the coaches provided additional support to reinforce engagement and adherence, focusing only on issues related to the main intervention (27, 39, 40, 46, 54, 58).

3.3.2 AI-powered coaching

Thirteen included studies (37%) analysed the use of AI-powered coaching using conversational agents (i.e., chatbots) to deliver DHIs (17, 38, 48, 49, 51, 52, 55, 56, 60, 65–67, 69). The development of conversational agents and chatbots in these studies was primarily based on Natural Language Processing (NLP) models (17, 49, 51, 56) or rule-based approaches, including decision-tree algorithms (38, 51). Most AI coaching interventions were delivered remotely through a digital platform, available 24/7 (38, 45, 48, 49, 51, 52, 55, 56, 60, 65, 66, 69). However, one study used on-site AI coaching in a controlled environment (17). Eleven studies mimicked human coaching sessions through quick text-based sessions with the AI chatbot. One chatbot, however, was primarily voice-based, with text-based options for certain activities. This chatbot could interpret speech and synthesise voices to respond to participants (17). Three studies provided unlimited access to the AI chatbots, enabling ad hoc questions, as well as guidance, monitoring and feedback outside of structured coaching sessions (56, 65, 66). Unlike human coaches, AI coaches were central to all DHIs. Given the artificial nature of the coaching design, no coaching qualifications or accreditations were reported in AI coaching studies.

3.3.3 Hybrid coaching

Four studies (11%) investigated hybrid coaching in DHIs (37, 44, 59, 63). Hybrid coaching refers to any study that integrates human coaches with AI-powered features within a DHI. Three studies investigated the impact of combining human coaching (delivered via video or text) with automated personalisation, support, advice, and motivation delivered by in-app messages, nudges or knowledge pills (short tips or pieces of advice) (37, 44, 59). The AI in these studies typically performed administrative tasks such as (a) sending personalised interventions and educational content (44, 59, 63), (b) monitoring activities, progress, engagement and adherence (37, 63), (c) sending motivational messages or nudges (37, 63), and (d) administering questionnaires (59). While two studies used AI and human coaching in parallel, the third study employed a “human-in-the-loop” approach for delivering hybrid coaching, where the human coach monitored, modified, and validated the AI coach's recommendations (59). The fourth study combined human coaching with a digital coach (similar to AI-powered coaching). The digital coach was an avatar that participants could interact with in-app through text-based prompts (63). This resulted in the AI-powered coach taking on more interactive and meaningful tasks like goal-setting with participants (63).

3.4 Lifestyle outcomes across coaching modalities

The reviewed studies assessed changes in physical activity, psychological wellbeing, stress management, healthy eating, sleep, and substance use across human-delivered, AI, and hybrid coaching interventions (Table 3). Among these lifestyle domains, physical activity was the most commonly addressed, covered by 55.8% of studies (n = 19), followed by psychological wellbeing (n = 18; 52.9%). Stress management was examined in nine studies and was closely associated with psychological wellbeing, with many studies addressing both constructs together. Given its interrelated role, stress management was discussed as a subset of psychological wellbeing in this review. Healthy eating was explored in 13 studies, while sleep (n = 4) and substance use (n = 2) were less commonly examined.

3.4.1 Physical activity

Physical activity was assessed through a variety measures, including active minutes, Metabolic Equivalent Tasks (METs), daily steps, or sedentary time measured through biometric feedback (37, 42–44, 59, 64, 66) and self-reported physical activity assessments (41, 45–48, 51, 56, 58, 61, 63, 66), and qualitative interviews (54). Studies examining human coaching reported mixed findings regarding its impact on physical activity. Several studies found improvements in physical activity measured through changes in METs (41, 47) and moderate-to-vigorous activity (MVPA) minutes (42, 43). However, other studies showed no meaningful changes or a decline in physical activity (45, 46, 64). Some studies also found that human-coach-facilitated DHIs promoted shifts in participants' awareness, motivation, and readiness to change, leading to active change in physical activity (46, 47), along with an increase in purposeful movement, like taking the stairs or walking instead of driving (54).

AI coaching generally showed consistent positive effects on physical activity. Studies reported improvements in physical activity measures, including METs (48), step count (66), active minutes (56, 66), MVPA minutes, and reduced sitting time (51). AI coaching was also associated with improved adherence and increased motivation (56). All four hybrid studies investigated the impact of this approach on physical activity, reporting variable results. Two studies found significant to moderate improvements in physical activity through active minutes (44, 63). However, a third study found decreased active minutes and steps among both intervention and control groups (37). The fourth study did not assess changes in physical activity from baseline but did report high rates of adherence and goal completion (i.e., achieving step targets and weekly active minute goals) (59).

3.4.2 Psychological wellbeing

Psychological wellbeing was primarily assessed through the reduction of depression and anxiety symptoms (27, 40, 45, 49, 52, 60, 62, 67) and general psychological wellbeing using a variety of wellbeing and mental health scales (50, 53, 62, 63, 65, 69). Other aspects of psychological wellbeing, such as worry, emotional control, mindfulness, personal growth, and life satisfaction, were also assessed to a lesser extent (17, 27, 47, 52, 55). Human coaching interventions were associated with reductions in depressive and anxiety symptoms (27, 40, 45, 62), along with reduced worry (40) and increased emotional self-efficacy and emotional control (47, 62). However, this was not reflected in one study among coached and non-coached groups (50) and another which aimed to improve health and wellbeing but did not use scales to assess wellbeing changes (53). AI coaching generally reported positive improvements in psychological wellbeing, including reductions in depressive symptoms (49, 60, 67) and anxiety (49, 52, 60), as well as improvement in general psychological wellbeing (69). AI coaching interventions also improved other wellbeing constructs like mindfulness (52), personal growth (17, 55), and life satisfaction (55). However, two AI-coaching interventions failed to report differences in psychological wellbeing (65, 67). Only one hybrid coaching study assessed psychological wellbeing (63]. While psychological wellbeing improved from baselines, this was not sustained after the human-coaching element of the intervention ended (63).

3.4.2.1 Stress management

All human coaching interventions examining perceived stress reported positive outcomes (40, 47, 68), with some showing greater improvement compared to control groups (40, 68). However, one study observed only minimal reductions in stress levels from baseline (47). Likewise, AI coaching interventions generally led to reductions in perceived stress, ranging from significant (52, 55, 67, 69) to minor improvements (49). One AI intervention reported no positive changes in stress levels (65). Hybrid coaching interventions did not assess stress management outcomes.

3.4.3 Healthy eating

Healthy eating was examined in AI and human coaching interventions only. The most common measure used to assess dietary improvements was daily fruit and vegetable intake (41, 51, 58, 61). Other measures included overall diet quality assessed via questionnaires (39, 42), adherence to the Mediterranean diet (56), protein intake (50), behaviours related to overeating and self-regulation (48). Intervention utilising human coaching demonstrated significant improvements in protein intake (50), fruit and vegetable consumption (41, 58, 61), and overall diet quality (39, 42). Two studies explored behavioural factors influencing healthy eating, reporting increased autonomy and competence (61) and improved control over eating habits (62). AI coaching interventions also yielded positive effects on healthy eating, though to varying degrees. While all three studies showed positive changes (48, 51, 56), only one found significant improvement in their diet scores (56). The latter study focused on eating habits rather than food quality, reporting significant reduction in overeating and snacking habits as well as self-regulation in eating behaviour (48).

3.4.4 Sleep

Sleep was assessed through self-reported sleep quality (27, 51, 53), and sleep duration measured via wearable devices (59). Studies examining human coaching generally reported improvements in sleep quality. One study found that most participants either improved or maintained their sleep quality (53), while another reduced sleep disturbances, with improvements sustained at follow-up (27). In contrast, AI coaching showed minimal impact, with no significant improvements in sleep quality or sleep scores (51). Hybrid coaching interventions provided limited findings on sleep. While one hybrid study assessed sleep outcomes, baseline comparisons were not available. However, results indicated that participants met the recommended seven to eight hours of sleep on nearly half of the recorded days (59).

3.4.5 Substance use

Substance use was assessed by two studies using human coaching. Both studies showed that coaching interventions had a positive impact on decreasing alcohol consumption (58), tobacco use, and smoking quit rates (57). The human-coach-led smoking cessation intervention also enhanced participants' confidence to quit smoking and reduced perceived difficulty in maintaining abstinence (57).

3.5 Engagement and satisfaction

Engagement was measured inconsistently across studies, with definitions and measures varying widely (Table 6). The most commonly reported metric was retention or intervention completion rate. For human coaching interventions, completion and retention rates varied from 80% to 100% (27, 39–41, 46, 47, 53, 57). AI coaching interventions reported similar completion and retention rates of 90% to 93%, with three outlying studies reporting significantly lower completion rates of 58% (52), 20.3%–45.4% (49), and 9.8% (60). Hybrid coaching interventions had retention rates of 55%–56.5% (37, 44). However, one hybrid study found that the human coaching component improved adherence to syncing data from wearable devices (37).

Table 6

| Author | Engagement | Satisfaction |

|---|---|---|

| Alley et al. (2016) (44) | Total Completion rate: 55% (83/151). 47% completed ≥3 modules, coaching completers: 82% vs. 43% others. Retention: No group difference. Week 9 survey completion: 73% (coaching) vs. 53% (others). Average website visits: 7.53; Average time spent: 87.07 min. Participants who completed coaching spent significantly more time on the website (174.64 min vs. 77.84 min) | 68% satisfied with the program; 77% with website usability; 76% with tailored advice; 91% with module questions. Coaching completers reported higher satisfaction (88% vs. 64%, not significant) |

| Aymerich-Franch and Ferrer (2022) (17) | Completion rate: 92% (30/32 participants) | Medium-high satisfaction with the coaching program. satisfaction with the coaching program at 6.06 out of 7 |

| Bakas et al. (2018) (45) | N/A | N/A |

| Blair et al. (2021) (46) | 79% participants checked the app daily. 93% completed all 5 coaching calls. Retention rate: 87% (47/54 participants) | N/A |

| Chang et al. (2023) (47) | Retention rate—80% (12 of 15 participants). All participants attended all three online health coaching sessions | N/A |

| Chew et al. (2024) (48) | Completion rate: 91.6% | N/A |

| Chow et al. (2020) (27) | The app was launched 21.5 times over 6 weeks. Completion rate: 87% | Mean satisfaction: 5.19/7. Usefulness of coaching calls: 4.22/5 |

| Daley et al. (2020) (49) | Completion rate: 20.34%–45.4%, depending on the program. Higher engagement correlated with lower anxiety and depression. Average response rate: 8.17 responses/day | N/A |

| Damschroder et al. (2020) (37) | Engagement was high initially but declined. 64.4% provided synched data at 6 months, 35.6% at 12 months. 70.8% completed ≥2 coaching calls, 56.7% completed all 3 calls. The coaching group correlated with better adherence to synched data (68.5% vs. 60.3%, difference not sustained) | N/A |

| D'Avolio et al. (2023) (50) | N/A | N/A |

| Dhinagaran (2021) (51) | Completion rate: 93%. 50% of participants completed all conversations. 40% responded immediately 75% of the time | 92% moderately satisfied. 54% likely to recommend, 57% likely to use again |

| Foran et al. (2024) (38) | Participants engaged with the intervention 4.26 days over 30 days, started 3.68 modules, completed 2.78, and sent 51.09 messages on average | 3.21/5 satisfaction score with modules. User satisfaction and participation/engagement were significantly associated with greater improvements in all primary outcomes (P = .04 to < .001). Participants with more unfinished modules (modules started but not completed) showed less improvement in positive psychological health |

| Gabrielli et al. (2021) (52) | Completion rate: 86% (61 out of 71 participants). By the end of the study, 58% (41 out of 71) of participants completed the postintervention questionnaire, representing an attrition rate of 42%. Engagement and willingness to complete a session were higher during the first and last weeks of the study | N/A |

| Gudenkauf et al. (2024) (53) | Participants completed 6.9/8 weekly assessments and attended 6.9/8 coaching sessions (86.5%). Wore wearable device 79.9% of study days. 100% baseline completers did an 8-week follow-up | Satisfaction: 4.7/5. 85% rated satisfaction as 5/5 |

| Han et al. (2024) (39) | Completion rate: 95%. App utilisation: 87% (first 3 months), 92% (4–6 months). Two-way interaction: 3 days/week (first 3 months), 2 days/week (4–6 months) | N/A |

| Heber et al. (2016) (40) | Participants completed 5.7/7 sessions (81.4%) and used the intervention for 8.27 weeks. 43.6% of participants preferred light coaching interaction, and 56.4% preferred intensive coaching. 76.5% requested message support | 92.2% satisfied with overall intervention |

| Horn et al. (2023) (54) | N/A | N/A |

| Ly et al. (2017) (55) | During the 2-week period, 78.6% of participants were active for at least 50% of the days. Active for more than half of the interventions 14 days. (average 8.21 days). Participants opened the app 1.27 times a day | N/A |

| Maher et al. (2020) (56) | Out of the maximum of 11 possible check-ins with chatbot, participants completed an average of 6.9 check-ins (64%). Engagement varied across the intervention. 70% of participants completed check-ins in weeks 2, 3, 4, and 12. Engagement gradually decreased to around 50% through weeks 8 and 9. Participants who completed the first weekly check-in had higher engagement across the intervention period than those who didn’t. completion rate was 90% (28/31) | N/A |

| Marler et al. (2019) (57) | Retention rate: 97.3% (183/188 participants). Completion rate: 95.2% (179/188 participants). The intervention group opened the app an average of 157.9 (vs. 86.5 in control, p < .001) times. High weekly login rates: 86%-98% (intervention), 85%–97% (control) | N/A |

| McGuire et al. (2022) (58) | The nurse coaching group had better adherence and lower attrition (35% vs. 50%) compared to the eBook group | N/A |

| Moreno-Blanco et al. (2019) (59) | Users read 88.09% of knowledge pills and reported following advice for 65.9% | Usability score (SUS): 81.5. indicating usability and high satisfaction |

| Ollier et al. (2023) (60) | Completion of at least one topic: 9.8% (n = 698). 7,135 downloaded the app, and 3,928 opened the app (55.8%) | The net promoter score increased as individuals progressed between periods 1 and 2. Ease of use and usefulness also increased. However, only marginally |

| Partridge et al. (2015) (41) | Completion rate: 85.6%. The mean number of coaching calls completed was 4.6/5, with 82.4% completing all 5 calls. Over half of the intervention participants replied to 8 or more of the 16 SMS text messages, with 20.3% replying to all. Most control participants replied to 2 or more of the 4 text messages, with 62.4% replying to all 4 | N/A |

| Price et al. (2022) (61) | The engagement for this intervention was high, with participants attending 95.2% of the sessions. Session attendance ranged between 66.7% (8 out of 12 sessions) and 100% (12 out of 12 sessions) | N/A |

| Sacher et al. (2024) (62) | Out of the 122 eligible participants who provided consent, 119 were enrolled, and 107 were included in the analysis | 81.9% found the health coaching useful/helpful |

| Santini et al. (2023) (63) | Completion rate: 68% (62/91 participants) | Average SUS score: 59 (below the average score of 68), indicating usability problems with the system |

| Smart et al. (2022) (64) | 73% set at least 7 goals over 8 weeks, and 47% set goals every week. Coaches sent 3–4 more messages/week than participants. Completion rate: 93% (28/30) | N/A |

| Spring et al. (2018) (42) | Retention at 9 months: 82.1%. Self-monitoring adherence declined but remained substantial (96.3% at baseline, 54.6% at 9 months). Coaching calls declined from 66.0% to 57.7% | N/A |

| Terblanche et al. 2022 (65) | Experimental group retention rate: 56% (75 out of 134), and for the control group: 70% (94 out of 134). Participants who used the AI coaching chatbot more frequently (more than 6 sessions) had a higher average increase in goal attainment (37.62) compared to those who used it less frequently (17.62) | N/A |

| To et al. (66) | 60% of the intervention group completed the post-intervention survey. 45% completed all 13 sessions. Engagement ratio: 74.3% (297 responses/400 messages) | N/A |

| Ulrich et al. (2024) (67) | On average, participants sent 6.7 messages per week to the chatbot and spent. Most participants (93.8%) read the messages sent by the chatbot. About half of the participants sent messages to the chatbot at least once a day | The average usability score for the chatbot was 61.6, with the majority of participants rating the chatbot as “OK” (78.8%) or “Good” (10.6%). Less than half of the participants (43.4%) would recommend the chatbot to others |

| Wiegand et al. (2010) (68) | N/A | N/A |

| Wijsman et al. (2013) (43) | Completion rate: 97% (226/235 participants). 95.6% of participants in the intervention group started the program after the initial assessment week. 91.2% of participants in the intervention group completed the 12-week intervention program | N/A |

| Williams et al. (2021) (69) | Completion rate: 27.3% (30/110 participants). Adherence: 11/21 days (M = 11.3, SD = 7.8) | Satisfaction: 6.61/10 (SD = 1.78), 63% rated ≥7/10. 81% found chatbot easy to use |

Engagement and satisfaction.

Several studies reported correlations between engagement levels and outcomes. Studies investigating the addition of a human-coaching component in DHIs found that participants who completed coaching spent more time on the DHI, completed more educational modules (44), had better adherence to the intervention (37, 58), improved retention (61) and increased wellbeing (63). Additionally, higher engagement with AI chatbots correlated with lower anxiety and depressive symptoms (49), improved wellbeing (38), increased physical activity (66), and a higher increase in goal attainment (65). Finally, one study found that early engagement (within the first week) predicted sustained engagement throughout the intervention (56), while another reported that participants who completed the full intervention had lower stress levels (40).

3.5.1 Satisfaction

Satisfaction with the DHI interventions was reported in 37% of the included studies (n = 13) (Table 6). Among hybrid studies, 75% (3 out of 4) reported satisfaction outcomes. However, AI coaching interventions had the highest proportion of studies reporting satisfaction, accounting for 46% (6/13), compared to 22% (4/18) of human coaching studies. Overall satisfaction rates were high across studies using human coaching in their DHIs, with 81.9% to 92.5% of participants reporting satisfaction for coaching interventions (40, 62). Additional studies reporting satisfaction through mean scores reported that 85% of participants rated a full score for satisfaction (5/5) (53) and a mean reporting score of 5.19/7 (27). AI coaching interventions showed mixed satisfaction outcomes, generally ranging from moderate to high satisfaction rates (17, 38, 51, 69). Three studies reported on the likelihood of participants recommending the intervention. One study found a significant change in the Net Promoter Score (60), while two studies reported that 43.4% and 54% of participants would recommend the AI intervention. Additionally, 57% of participants indicated they would use it again (51, 66). Hybrid studies reported varied satisfaction rates varying from 67% to 81.5% (44, 59), with one study reporting usability below the average threshold, indicating low satisfaction (63). Interestingly, one hybrid study found that satisfaction rates were higher among participants who completed the coaching component of the intervention (88% compared to 64%) (44).

3.6 Working alliance

Seven studies (20.6%) examined working alliance and connection between participants and coaches. While one study used a working alliance scale, most explored working alliance through qualitative feedback from participants. Human coaching showed a high working alliance. Participants experienced authentic and strong connections, social support, and accountability (64). They also described a sense of investment and warmth from their coach (61), even in text-based coaching (64). This allowed participants to feel comfortable, motivated, and honest about their progress (61). Participants perceived AI coaches as engaging and lifelike, often viewing their interactions as relational (55, 60, 69). Participants viewed chatbots as a positive addition, appreciating its non-judgemental nature, finding it easier to share information (17) and feeling validated in their experiences (69). On a 7-point working alliance scale, the overall alliance with AI and human coaches was rated 4.23, with the bond component scoring 4.20 (67). Another study using the Session Alliance Inventory (ISA) found a minor but insignificant increase in scores (60). Despite positive connections made, some participants found chatbots patronising and preferred to connect to a real person. Others reported feelings of loneliness, disconnection and a lack of warmth while engaging with chatbots (17, 69). One study noted that chatbot interactions felt repetitive, contributing to feelings of disconnection (55). In one hybrid coaching intervention, participants valued human support alongside the AI coaching and expressed a desire for continued human support alongside the AI interventions, particularly for motivation, confidence, and technical support (63).

4 Discussion

This review explored how digital health coaching is integrated into DHIs and its impact on lifestyle outcomes and engagement. We identified three primary coaching models: human, AI, and hybrid (a combination of both human and AI coaches). Our findings suggest that both human- and AI-delivered coaching are generally perceived as acceptable and satisfactory components of DHIs, with trends indicating positive effects on health and wellbeing. Engagement and retention were generally high across all coaching models, with higher engagement linked to improvements in lifestyle outcomes. However, engagement and satisfaction were typically higher with human-delivered coaching. While working alliance was strong across all coaching models, participants reported a stronger sense of connection with human-delivered coaching, including within hybrid interventions.

Despite advancements in digital health coaching, studies were predominantly exploratory, early-intervention studies, focusing on feasibility and acceptability of coach-facilitated DHIs. While individual studies reported significant findings, the lack of consistency in study designs and outcome measures prevented clear inferences about broader trends in lifestyle and engagement. Likewise, there was an imbalanced representation of human (n = 18), AI (n = 13), and hybrid (n = 4) coaching interventions. This disparity, along with inconsistencies in outcome measures, intervention designs and coaching characteristics, limited direct comparisons and the generalisability of our findings; therefore, caution is warranted when interpreting the results in this review.

4.1 The role of coaching: delivery, standards, and trends

This review examined the integration of health coaching with DHIs, focusing on delivery methods, coaching roles, and standards for protocols and coach engagement (Table 5). Findings revealed a lack of consistency in reporting delivery methods, which contributed to ambiguity in the coaching protocols used. Only six studies provided comprehensive descriptions of all the extracted coaching characteristics that represent delivery (17, 42, 52, 53, 58, 69). The lack of transparency in coaching delivery methods made it difficult to determine the optimal frequency and intensity of coach-participant engagement for best outcomes. The total number of coaching sessions varied widely, ranging from 2 to 24, with a mean of 8.85 sessions per intervention (Table 5). Additionally, coaching sessions were most commonly conducted weekly (17, 50, 53, 61) and biweekly (44, 52), but no clear pattern emerged linking coaching frequency to delivery mode. Among long-term studies (ranging from 3 to 12 months), coaching was typically staggered, starting with weekly coaching sessions before transitioning to bi-weekly and monthly as the intervention progressed (42, 54, 57). Very few studies reported the qualifications of the coaches, making it difficult to determine who was delivering the coaching. Nonetheless, some trends emerged from the studies that did provide details on coaching delivery methods. Most studies indicated that both AI and human coaches played a central role in DHIs, though eight studies employed coaches in a supportive capacity (27, 37, 39, 40, 44, 46, 54, 58). In these cases, the role of the coach typically focused on supporting participants' technology use and enhancing usability through education around app features (27, 37, 46), reviewing and monitoring participant data (46), providing feedback to participants (39, 40, 44), adding accountability and promoting the implementation of skills gathered from the main intervention (i.e., educational modules and training) (27, 44, 54, 58).