- 1Injury Prevention Research Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, United States

- 2Department of Epidemiology, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, United States

- 3Highway Safety Research Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, United States

- 4Department of Health Policy and Management, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, United States

- 5North Carolina Institute for Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, United States

Introduction: While collaboration and cooperation are regarded as foundational to Vision Zero (VZ) and Safe Systems initiatives, there is little guidance on structuring VZ collaboration, conducting collaborative goal setting, and aligning tangible action across organizations. As part of a larger VZ mutual learning model, we developed a VZ Leadership Team Institute to support communities in collaborative VZ strategic planning and goal setting. The purpose of this paper is to describe the development and evaluation of the Institute, which can serve as a foundation for other initiatives seeking to move VZ planning and implementation forward in a collaborative, systems-aware manner.

Methods: In June 2021, eight multi-disciplinary teams of 3–6 persons each (n = 42 participants) attended the Institute, representing leaders from communities of various sizes. Surveys were administered pre, immediately post, and 6 months following the Institute. We measured confidence in a range of skills (on a 5-point scale, 1: not confident to 5: very confident). Surveys also measured coalition collaboration pre-Institute and 6 months post-Institute (on a 4-point scale, 1: strongly disagree to 4: strongly agree).

Results: The largest increases in confidence from pre- to immediately post-Institute were for collaboratively drafting objectives and actions for VZ goals (pre-mean: 2.6, SD: 0.9 to post-mean: 3.8, SD: 0.9); incorporating equity into goals (pre-mean: 2.8, SD: 1.0 to post-mean: 3.9, SD: 0.8); and knowing how to keep VZ planning and implementation efforts on track (pre-mean: 2.6, SD: 1.0 to post-mean: 3.7, SD: 0.7). For all measures, average confidence in skills decreased from immediately post-Institute to 6 months post-Institute, but remained greater than average scores pre-Institute. Several measures of coalition collaboration maintained high agreement across time, and mean agreement increased for reporting that the future direction of the coalition was clearly communicated to everyone (pre-mean: .6, SD: 0.8; 6 months post-mean: 3.1, SD: 0.4). However, average scores decreased for feeling like the coalition had adequate staffing (pre-mean: 3.0, SD: 0.6; 6 months post-mean: 2.3, SD: 0.5).

Discussion: The Institute utilized innovative content, tools, and examples to support VZ coalitions’ collaborative and systems-aware planning and implementation processes. As communities work toward zero transportation deaths and serious injuries, providing effective support models to aid multidisciplinary planning and action around a Safe Systems approach will be important to accelerate progress toward a safer transportation system.

1 Introduction

Road traffic crashes are a leading cause of death with more than 1.3 million people killed annually on roadways around the world (World Health Organization, 2018). Millions more suffer from nonfatal injuries with many of these injuries resulting in debilitating and lifelong consequences (e.g., physical or cognitive disability). Recognizing the preventable toll of these crashes, several cities have adopted comprehensive and aggressive strategies to reduce roadway injuries and deaths, namely Vision Zero or Safe Systems strategies (Tingvall and Haworth, 1999; Johansson, 2009; Belin et al., 2012; Hughes et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2017).

Vision Zero is an initiative that aims to eliminate all deaths and serious injuries on our roadways (Tingvall and Haworth, 1999; Johansson, 2009; Vision Zero Network, 2017a; Vision Zero Network, 2017b; Kim et al., 2017). It centers healthy and safe mobility for all road users, often focusing on improving conditions for the most vulnerable road users (e.g., pedestrians, bicyclists) in recognition of 1) the long-held imbalance of prioritizing vehicle occupants in road design, funding investments, and policies and 2) the understanding that improving safety for vulnerable road users (e.g., through traffic calming and design improvements) generally translates to improved safety for all road users (Tingvall and Haworth, 1999; Johansson, 2009; Vision Zero Network, 2017a; Vision Zero Network, 2017b; Kim et al., 2017). At the core of robust Vision Zero initiatives is a commitment to a Safe Systems approach. A Safe Systems approach starts from the understanding that people are imperfect and make mistakes that can lead to crashes and that when these crashes do occur, people have limits in terms of crash forces that can be absorbed before death or serious injury results (Collaborative Sciences Center for Road Safety, 2020; Johansson, 2009; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2008; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2016; U.S. Federal Highway Adminstration, 2022). It recognizes that no one should die as a result of an error and that the overreliance on personal responsibility in the field of transportation safety has led to detrimental transportation injury trends. With that understanding, a Safe Systems approach includes proactively strengthening all parts of the transportation system (e.g., infrastructure, vehicle design, safety-related behavioral norms) and building in redundancies so that if an error occurs or a prevention measure fails, the others still protect people from death or serious injury. A Safe Systems approach further recognizes that strengthening all parts of the transportation system and building in redundancies requires acknowledgement that road safety is a shared responsibility (not the responsibility of any one person), and therefore necessitates active collaboration among several essential stakeholders (e.g., planners, engineers, public health practitioners, policymakers) (Collaborative Sciences Center for Road Safety, 2020; Johansson, 2009; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2008; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2016; U.S. Federal Highway Adminstration, 2022).

Vision Zero and the related adoption of a Safe Systems approach often represent a notable shift from traditional transportation safety approaches in several ways (Khorasani-Zavareh, 2011; Vision Zero Network, 2022). For example, Vision Zero and Safe Systems approaches move away from an often-central focus on individual behavior change to system-wide change and involve a strong commitment to collaboration across sectors and disciplines. Cross-sector and cross-discipline collaboration and alignment has long been a strategy for addressing complex and deep-seated health and social problems (e.g., tobacco, HIV/AIDs, physical inactivity, housing instability), and several communities have cited the importance of this fundamental tenet in supporting effective Safe Systems work (Butterfoss et al., 1993; Butterfoss et al., 1996; Roussos and Fawcett, 2000; Abel et al., 2019; Rutgers University Center for Advanced Infrastructure and Transportation, 2022). While collaboration and cooperation are generally regarded as foundational to Vision Zero, there is little guidance or support on how best to initiate and sustain effective collaboration and cooperation, including how to establish common goal setting and action alignment across organizations working toward Vision Zero.

As part of a larger Vision Zero mutual learning model, supported by an academic-state transportation partnership between the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the North Carolina Governor’s Highway Safety Program, we developed an intensive Vision Zero Leadership Team Training Institute to support communities in collaborative Vision Zero strategic planning and goal setting. The purpose of this paper is to describe the development of the novel Leadership Institute and lessons learned, which can serve as a foundation for other Vision Zero initiatives seeking to move their Vision Zero planning and implementation efforts forward in a collaborative, systems-aware manner (Naumann et al., 2020). Additionally, we provide evaluation results on the Institute’s effectiveness as a tool to spark multi-sector Vision Zero collaboration and goal development using a pre-post study design.

2 Materials and methods

The Vision Zero Leadership Team Training Institute curriculum was developed from September 2020 through May 2021. Any group in North Carolina interested in pursuing Vision Zero within their community was eligible to apply to attend the Institute. To participate in the Institute, a group was required to submit an application that included a team of at least three members from different agencies or sectors to represent their core Vision Zero planning team, demonstrating a commitment to collaboration and shared responsibility. Institute sessions were designed to provide a mix of didactic material, practice-based examples and talks, and team time for groups to reflect on material and relate it to plans for their specific community Vision Zero efforts.

Below, we first discuss the underlying theory and framework that was used to guide the design of Institute components. We then describe data collected on the teams attending the Institute. Finally, we outline the skills and team collaboration measures and analyses used to evaluate the Institute.

2.1 Leadership Institute conceptualization and underlying framework

The Community Coalition Action Theory (CCAT) was the theoretical underpinning for Vision Zero Leadership Team Training Institute curriculum development (Butterfoss and Kegler, 2002; Kegler And Swan, 2011; Kegler and Swan, 2012). The CCAT, grounded in extensive literature and practice, includes an underlying framework of constructs and propositions for developing successful coalition structures, processes, and outcomes (Butterfoss and Kegler, 2002; Butterfoss, 2004; Kegler et al., 2010; Kegler And Swan, 2011; Sharma And Smith, 2011; Kegler and Swan, 2012; Harooni and Ghaffari, 2021). The CCAT identifies that coalition development progresses through stages from coalition formation through institutionalization with frequent cycles back to earlier stages as challenges arise, planning cycles within the coalition are repeated, or coalition members change (Butterfoss and Kegler, 2002). In other words, coalitions working to achieve large scale health and social change, like Vision Zero, do not often progress in a linear fashion, but rather through an iterative process with periods of growth and periods of setback or stagnation. The CCAT also acknowledges that community context, including norms, social capital, sociopolitical climate, and trust, plays a critical role and affects movement through stages (Butterfoss and Kegler, 2002).

Vision Zero and a Safe Systems approach are relatively new in a United States setting and specifically in North Carolina. We therefore focused Leadership Institute development and design on key factors and processes that generally occur in the initial CCAT stage, the formation stage (Butterfoss and Kegler, 2002). The formation stage includes establishing a convener or lead agency for the coalition who has linkages to several key stakeholders and partners. The lead agency is responsible for bringing together core agencies and organizations that are critical to shaping the desired outcome. Core organizations are expected to recruit additional partners to establish a coalition focused on achieving the health or social goal (i.e., Vision Zero). As part of the CCAT formation stage, coalition leaders are also expected to develop structures (e.g., working groups, task forces, committees) and processes (e.g., communication frequency, workgroup or committee rules) to support effective coalition functioning (Butterfoss and Kegler, 2002). Established structures and processes help ensure the coalition is equipped to take necessary steps to assess community readiness for initiative planning and implementation, develop mutual goals and actions, and move toward program implementation. A notable component of this stage includes ensuring that the costs of participation are appropriately balanced with benefits of involvement to support coalition sustainability. These core CCAT processes and principles were used to guide all Institute components and evaluation measures.

2.2 Team characteristics and team-specific Vision Zero goals

For all teams attending the Institute, we collected data on team characteristics, including disciplines represented on teams, Vision Zero and Safe Systems-related challenges faced prior to the Institute, and current context and support for Vision Zero in attendee communities. A central aim of the Institute was supporting communities in developing collaborative and Safe Systems-informed Vision Zero goals. To support this process, we asked teams to bring draft goal(s) to the Institute. We collected information on the specific Vision Zero goals that teams entered the Institute with (i.e., anticipated Vision Zero goal(s) they wanted to focus on and refine throughout the Institute) and goals they had formulated by the end of the Institute.

2.3 Evaluation measures

As part of the Institute application, all participants were asked to sign and submit a letter of commitment to completing all parts of the Institute, including evaluation surveys. We used several self-reported web-based measures to evaluate the Institute’s impact on confidence in Vision Zero and Safe Systems-related skills and on team collaboration and cooperation.

2.3.1 Confidence in skills

We administered web-based surveys prior to the Institute, immediately following the Institute, and 6 months post-Institute that asked participants about their confidence in several skills, including their ability to explain what Vision Zero means to a variety of audiences; draft Vision Zero-related goals, objectives, and actions; develop a strong Vision Zero coalition; deliver an effective Vision Zero “pitch” (i.e., an “elevator speech”); and keep Vision Zero planning and implementation efforts on track. Confidence in each measure was assessed on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not confident, 2 = a little confident, 3 = somewhat confident, 4 = confident, 5 = very confident).

2.3.2 Collaboration and cooperation

We also used several collaboration measures to assess the characteristics of, magnitude of, and change in collaboration across teams and within teams over time. Similarly, measures were assessed via web-based surveys; however, collaboration measures were only assessed prior to the Institute and 6 months post-Institute, as no change was expected in the short-term (i.e., over the few days of the Institute). We adapted measures from three tools to develop the assessment: the Wilder Collaboration Factors Inventory (Mattessich et al., 2001; Ziff et al., 2010; McCullough et al., 2017; Wells et al., 2021), the Organizational Climate Measure Tool (Patterson et al., 2004; Patterson et al., 2005; Nordgård, 2011; Schneider et al., 2013), and the Council Assessment Tool (Calancie et al., 2017; Calancie et al., 2018a; Calancie et al., 2018b).

The Wilder Collaboration Factors Inventory has been used extensively in prior research and practice to measure and guide coalition coordination and collaboration efforts (Mattessich et al., 2001; Ziff et al., 2010; McCullough et al., 2017; Wells et al., 2021). We used the third (and most recent) edition of the Inventory, which includes 44 items that measure 22 factors. We retained 21 items that were most pertinent to Vision Zero coalitions and made minor wording changes to tailor the items to Vision Zero and transportation safety contexts (Appendix, Supplementary Table S1). Retained items measured the extent to which members share a stake in the coalition and its work, acknowledge benefits of coalition membership, possess shared and formalized decision-making, believe the coalition sits within a favorable political and social climate, perceive clear roles and structure within the coalition, feel the coalition has adequate resources (e.g., staffing, funds), and have created evaluation and continuous learning processes. Each item was measured on a 4-point Likert scale from strongly disagree 1) to strongly agree 4) with higher mean scores indicative of greater collaboration strength.

We supplemented measures from the Wilder Collaboration Factors Inventory with additional items from the Organizational Climate Measure Tool (Patterson et al., 2004; Patterson et al., 2005; Nordgård, 2011; Schneider et al., 2013). The Organizational Climate Measure Tool includes questions that assess 17 dimensions of coalition or team perceptions of work environment and climate. Dimensions include team integration, clarity of organizational goals, performance feedback, and involvement in decision-making and direction. Prior research has shown that the tool possesses good reliability and concurrent, predictive, and discriminant validity in previous samples (Patterson et al., 2004; Patterson et al., 2005). As with the Wilder Collaboration Factors Inventory, we retained a subset of items (n = 10 of 95 items) most pertinent to Vision Zero coalition development and climate, including measures examining mission and goal clarity, conflict management, and coalition member integration. As with the Wilder Collaboration Factors Inventory, items were tailored to fit a Vision Zero context, and we used the same 4-point Likert scale from strongly disagree 1) to strongly agree 4) to assess agreement with each of the items.

Lastly, we used the Council Assessment Tool to measure several elements of coalition structure and functioning. The Council Assessment Tool was developed to examine organizational capacity, social capital, and structure and diversity of relationships within coalitions or councils (Calancie et al., 2017; Calancie et al., 2018a; Calancie et al., 2018b). Prior researchers have used the tool to examine functioning and collaboration within food policy councils and family and community violence prevention coalitions (Allen et al., 2012; Calancie et al., 2017; Calancie et al., 2018a; Calancie et al., 2018b). We selected 9 of the 59 items to specifically help measure breadth of active coalition membership, inclusivity within the coalition climate, and trust and communication in the coalition. For each item, minor modifications were made to align with the topic of transportation, and agreement was similarly measured on a 4-point Likert scale from strongly disagree 1) to strongly agree 4).

2.3.3 Satisfaction with the Institute

We also gathered data on satisfaction with the Institute, perceptions of team-based facilitator presence, and clarity of material covered. Complete wording of these items is available in the Appendix (Supplementary Figure S1). We measured these perceptions on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = agree, 4 = strongly agree).

The Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill reviewed and approved this study.

2.4 Analyses

We synthesized and described the development of the Institute, including daily objectives, tools used, and connections to practice-based examples. We also synthesized key characteristics and goals by team, including Vision Zero community size, disciplines represented on Vision Zero leadership teams at the Institute, current support from community leadership for Vision Zero, and Vision Zero goal evolution during the Institute.

We calculated means and standard deviations for confidence in skills across the three time points: pre-Institute, immediately post-Institute, and 6 months post-Institute. Due to small sample sizes and non-normal distribution of the data, we used Wilcoxon signed-rank tests to test for statistical significance in changes across these three time points, using a statistical cut point of 0.05. Similarly, for collaboration and cooperation measures, we calculated means and standard deviations of measures pre-Institute and 6 months post-Institute and used Wilcoxon signed-rank tests to assess change across time. As a sub-analysis, we also demonstrate a team-specific analysis for coalition collaboration to illustrate how team-specific feedback can be used to pinpoint specific coalition facets requiring attention. While a primary objective of this paper is to examine how confidence in skills and collaboration characteristics changed across the larger group attending the Institute, demonstrating how these tools can be used by individual coalitions for continuous monitoring and quality improvement is important.

3 Results

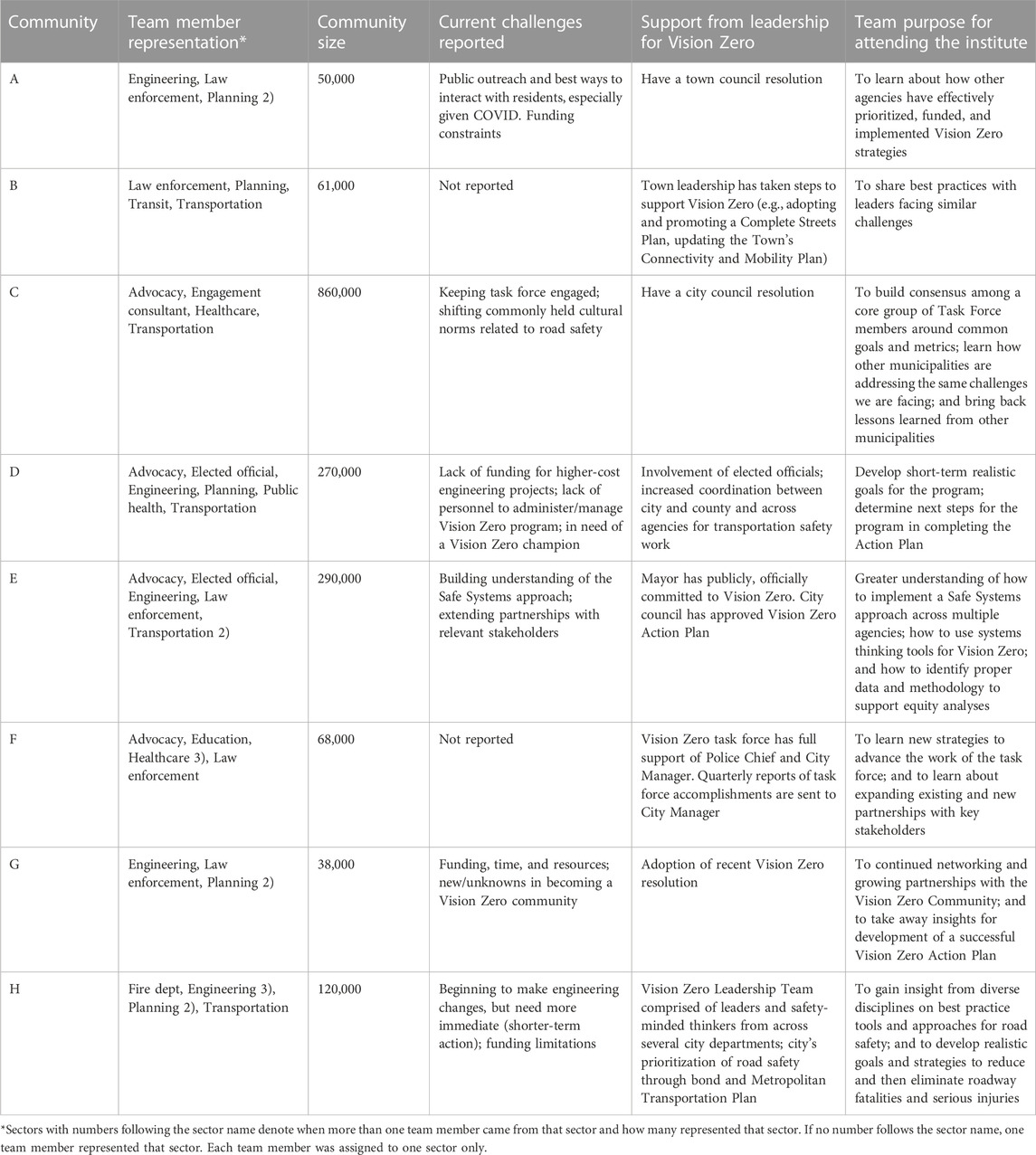

Guided by the CCAT framework, we developed a four-part Institute focused on leading change within multisector coalitions and collaborations, gaining a robust understanding of collaborators’ roles and responsibilities related to Vision Zero, understanding the importance of establishing specific coalition structures and processes, examining the larger context or climate within which one’s coalition work sits, and establishing specific collaborative goals and actions for next step Vision Zero planning and implementation grounded in equity. Table 1 summarizes the focus of each Institute part or session, detailing the specific objectives, tools used to support coalitions’ training and application of core concepts, and practice-based examples. Practice-based examples were provided by Vision Zero leaders from across the U.S. who could translate principles into real-world examples from their own Vision Zero and Safe Systems-informed work. We describe the specific components of each Institute session in greater detail in Section 3.1.

TABLE 1. Overview of Vision Zero Institute objectives, tools used, and connections to practice-based examples.

3.1 Leadership Institute objectives, tools, and outcomes

Prior to the Institute, we provided teams with information briefs and links to short video clips that covered core Vision Zero and Safe Systems concepts to ensure that all team members had a common understanding of key principles prior to arrival (Table 1). Additionally, at the Institute, we supported each team in working through collaborative Vision Zero goal setting, with goals tailored to where they were in their Vision Zero planning and implementation process. This process was used to translate key principles learned at the Institute into tangible future plans and next steps. We instructed teams that goal ideas or themes could range from establishing a coalition to building up community engagement efforts to focusing on implementation of specific speed management strategies, among others. To prepare for goal work at the Institute, we provided teams with a Goal Development Handout and short video on effective goal setting. They were encouraged to review the materials, discuss potential goal ideas, and submit their idea to the facilitation team prior to the Institute, so that team time at the Institute could be spent refining the goal and detailing actionable steps to achieve their goal, utilizing content taught at the Institute.

The four Institute sessions were conducted remotely due to the COVID-19 pandemic in June 2021 with each session lasting 3 h. One 3-h session was held per day, such that the Institute spanned 4 days. Each session was designed to support core CCAT processes and to help coalitions plan for the coming year, with focused discussion around goals. Each session included a mix of lectures, discussion, presentations from Vision Zero leaders from across the country, and team time to relate the content back to their specific community goals. Each team was assigned a facilitator to help guide them through structured activities to ensure that Institute content was translated and applied to their own community Vision Zero work. The content and tools used in each session are described below (Table 1).

In Session 1, we discussed road traffic injury as a complex and adaptive problem, requiring skills in adaptive leadership (i.e., the ability to lead a group into a co-learning space that allows group members to build relationships, expand perspectives, and test solutions, building capacity to iterate effectively over time), systems change, and multisector collaboration (through coalitions) to support action. We provided time for teams to work through a conversation guide called the “6 Core Conversations,” adapted from Peter Block’s book Community: The Structure of Belonging, to support teams in establishing accountability and commitment, explore unique team member assets, and articulate possibilities and hopes for future coalition work together (Block, 2008). Facilitators also encouraged teams to use the guide and prompts at larger coalition meetings post-Institute to support community building and commitment within larger Vision Zero coalitions. Teams then heard from a Vision Zero leader from outside of North Carolina, who provided perspective on how she saw Vision Zero as a complex problem and the adaptive solutions her city worked to implement as part of their initiative. Finally, teams were introduced to a “Goal Reflection and Refinement” handout that they utilized throughout the Institute to refine the goal idea they had brought to the Institute within the context of the material covered that day. The handout included specific prompts to relate daily content to their goal refinement process. For example, after Session 1, teams were asked to reflect on their goal, the larger importance of their goal, potential barriers that might stand in the way of their coalition achieving the goal, and proactive plans and processes for responding or adapting to potential foreseen and unforeseen barriers to goal achievement.

Building from Session 1, Session 2 focused on exploring roles and relationships in the broader transportation system and how these relate to coalition make-up. We also specifically discussed equity as a central tenet of Vision Zero and employed new skills in equity- and systems-aware thinking to further consider coalition formation and refine specific Vision Zero team goals. To accomplish this, we used a guide called the “Five Rs.” The Five R’s is a simple framework, originally developed by the U.S. Agency for International Development and adapted by our team for work on complex health and social issues (U.S. Agency for International Development, 2016). The framework, applied with an equity framing, helped teams center equity in their coalition and goal development work. Specifically, the Five Rs is designed to help a team: 1) define meaningful and equitable Vision Zero-related outcomes related to the goals selected by each team (results; “What does equity in Vision Zero look like?”); 2) ensure the coalition is engaging and collaborating with all relevant stakeholders (roles) to achieve these results/goals; 3) consider action mindful of available assets (resources) to achieve goals; 4) reflect on rules/norms at play in the system that might help or hinder goal achievement; and 5) consider what needs to be true about key relationships among system actors (i.e., those with a role in the system) and elements (e.g., between actors and resources) to achieve the specified outcome/goal. Following this activity, another Vision Zero leader discussed how equity was centered in their city’s Vision Zero coalition, goal development, and implementation work, and following this discussion, teams returned to their goal reflection and refinement work to apply content to their community’s plans. Specific goal reflection and refinement handout prompts for Session 2 led the teams through the development of equity-centered objectives for their goal, drawing from the Five Rs work and equity discussions from the day.

In Session 3 we continued to work through frameworks and guides introduced in Session 2, while providing additional detail on tangible coalition structure and the importance of and approaches to establishing a coalition with sustainability in mind from the outset. In this session, we discussed how to assess and improve teams’ coalition structure and makeup given new thinking about larger systems and equity (from Session 2) (Calancie et al., 2021), and we heard from a Vision Zero leader who spoke about specific coalition structures and processes they used to support Vision Zero planning and implementation. Teams spent time relating this content to their specific goals by using the goal reflection and refinement handout to outline specific actions (to be embedded under their goals and objectives) and to discuss how their coalition structure and resources could support these actions, or might need to adapt to better support specified actions.

Finally, in Session 4, we focused on maintaining coalition momentum and accountability. Three tools were used to accomplish this objective. We used a “Making the Pitch Guide” that outlined components needed to formulate an effective pitch to recruit or engage a potential Vision Zero partner (e.g., new coalition member, potential funder, policymaker), recognizing this as a key skill for maintaining robust coalition membership. Teams also worked with two tools to support their coalition processes and momentum in the short- and long-term. For short-term planning, we introduced a tool called the “30/30 tool” for suggested use during coalition meetings. The 30/30 tool includes a series of prompts to help coalitions quickly reflect on what they have learned in the last 30 days and adapt potential actions for the next 30 days—to support a 30-min meeting discussion. For longer-term self-assessment and planning, we introduced a coalition “Sustainability Toolkit,” adapted from a toolkit developed by the North Carolina Division of Public Health for violence prevention coalitions (North Carolina Division of Public Health Injury and Violence Prevention Branch, 2019). Our adapted toolkit summarized several of the topics covered across the Institute (e.g., coalition structure, equity, and diversity assessments), as well as additional domains (e.g., financing, community engagement), to consider when forming and maintaining coalitions aimed at addressing complex transportation problems. Teams were provided time to use the 30/30 tool to plan next steps post-Institute, reflecting on what they learned. Finally, Session 4 included a series of recorded interviews with Vision Zero leaders from across the U.S. speaking about Vision Zero integration and sustainability, work to ensure that Vision Zero represents a notable shift as opposed to a short-term program, and lessons learned from their own experiences in Vision Zero planning and implementation thus far.

Taken together, the Institute sessions were designed, within a CCAT framework, to: develop skills, knowledge, and confidence related to Vision Zero and Safe Systems principles; motivate and support coalition building efforts, making greater use of collaboration best practices; and support collaborative and systematic goal setting and planning processes.

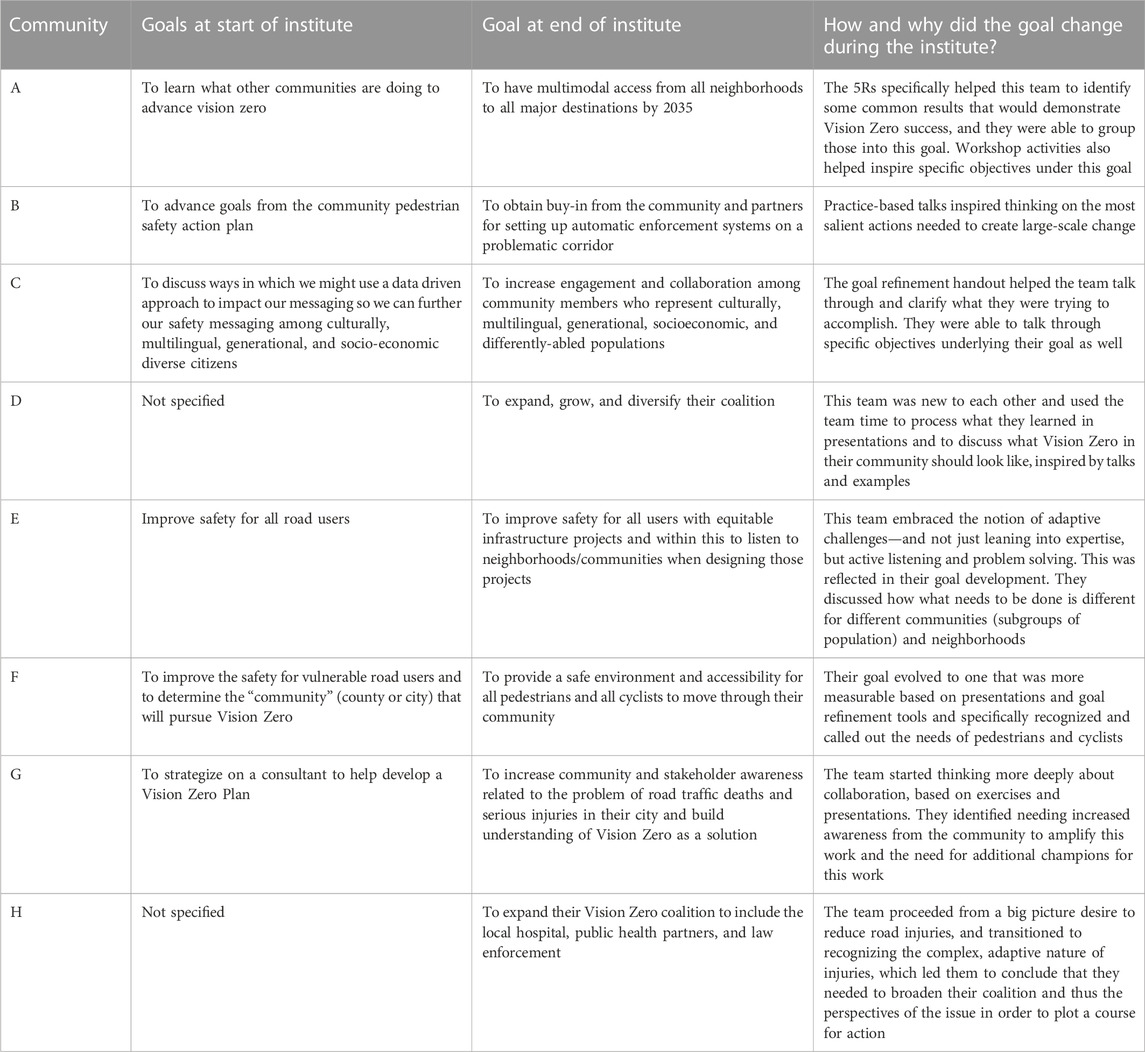

3.2 Team characteristics, enablers, challenges, and team-specific Vision Zero goals

Eight teams participated in the Vision Zero Leadership Team Training Institute (Table 2). Teams ranged in size from three to seven, with members representing several different disciplines or sectors, including advocacy (n = 4), education (n = 1), local elected officials (n = 2), engineering (n = 7), community engagement (n = 1), fire and emergency response (n = 1), healthcare (n = 4), law enforcement (n = 5), planning (n = 8), public health (n = 1), transit (n = 1), and transportation (n = 6). Teams represented communities ranging in size from 38,000 to 860,000 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020).

While all teams reported some support from their community for Vision Zero, as evidenced by a town or city council resolution, public declaration, or involvement of influential persons in specific Vision Zero-related efforts, teams also reported several challenges in their Vision Zero planning and implementation efforts. Challenges included building a shared understanding of a Safe Systems approach, determining how best to keep a task force or coalition engaged, lack of funding and personnel to complete work, conducting effective public outreach and engagement (particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic), recruiting an influential champion for Vision Zero efforts, shifting commonly held transportation and road safety-related norms related to where responsibility rests and the types of actions that should be implemented, growing a partnership network, and knowing where to start as a new Vision Zero coalition (Table 2). Following from these challenges, teams had several objectives they hoped to achieve at the Institute, which included learning from other teams across the state broadly on lessons learned and specifically about how they prioritized and funded Vision Zero strategies, determining how best to build consensus on common goals and metrics within a Task Force or coalition, developing short-term realistic goals for the initiative, learning how to effectively build and grow existing and new partnerships, developing a common understanding of how to apply a Safe Systems approach across agencies, gaining tools to support equity analyses to inform Vision Zero planning, and extracting insights on the best steps for Vision Zero action plan development.

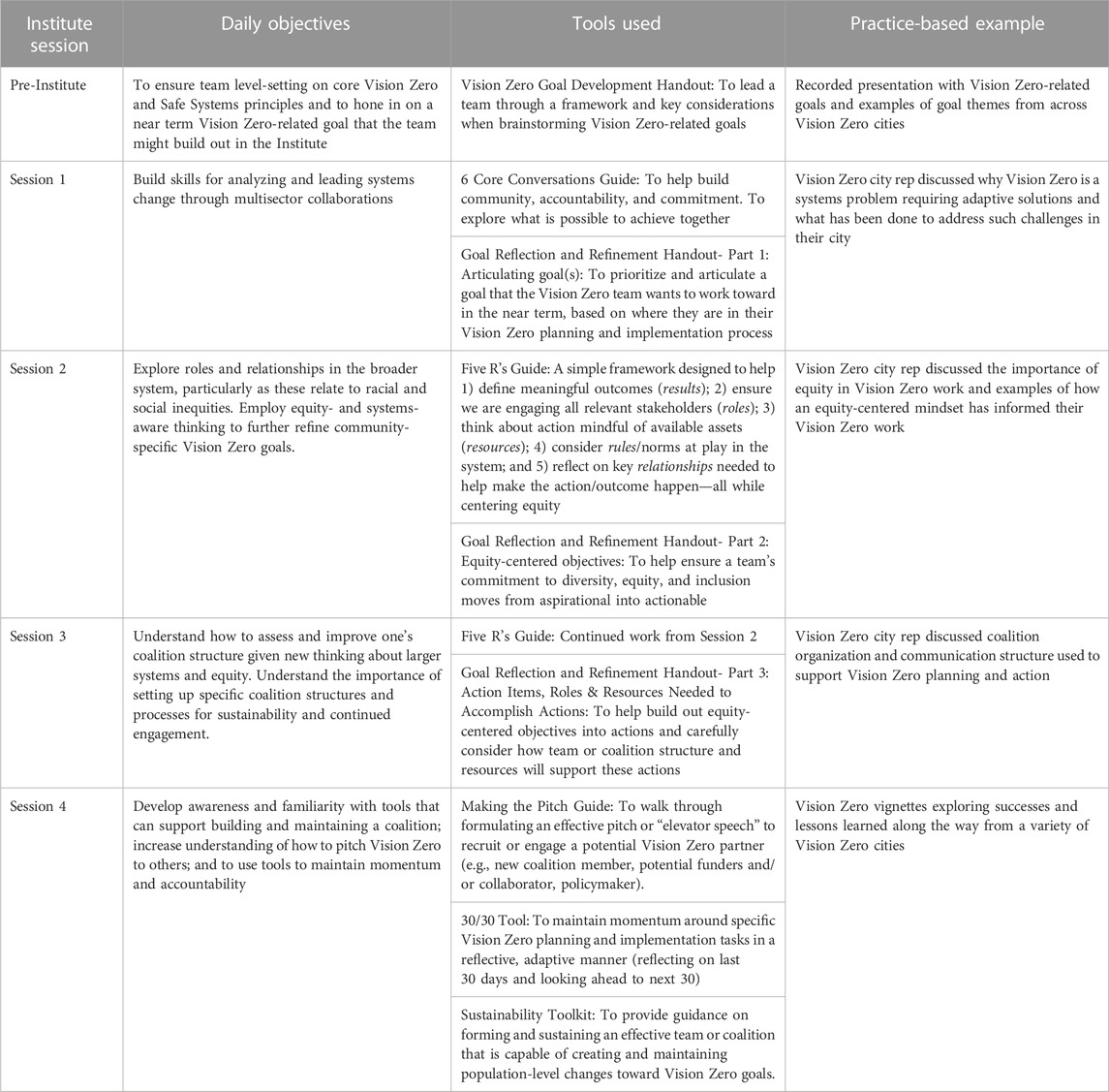

Finally, a central focus of the Institute was on applying principles learned through the Institute in tangible goal setting and action planning (Table 3). Each team was asked to bring an idea of a goal that they wanted to focus on and refine during the Institute. Goals ranged from improving the safety of vulnerable road users to developing a Vision Zero Plan in the coming year to using a data driven approach to improve culturally appropriate Vision Zero messaging. Two communities did not have a specific goal at the start of the Institute. During the course of the Institute, different teams found different tools particularly useful for advancing their Vision Zero-related thinking and goal setting, and at the end of the Institute, goals had evolved with most coalitions having a more prominent focus on authentic collaboration and engagement. Goals at the end of the Institute included improving multimodal access within neighborhoods to major destinations, engaging with the community on Vision Zero efforts (including automated speed enforcement), diversifying coalition membership, authentically listening to and collaborating with communities when designing and implementing Vision Zero-related projects, and increasing awareness of road traffic injury to build community support for action.

3.3 Evaluation measures

We administered surveys to measure changes in confidence in skills and changes in collaboration and cooperation prior to, immediately post, and 6 months post-Institute. Thirty-nine of 42 total participants (93%) responded to the pre-Institute survey, 35 responded immediately post-Institute (83%), and 16 responded 6 months following the Institute (38%).

3.3.1 Confidence in skills

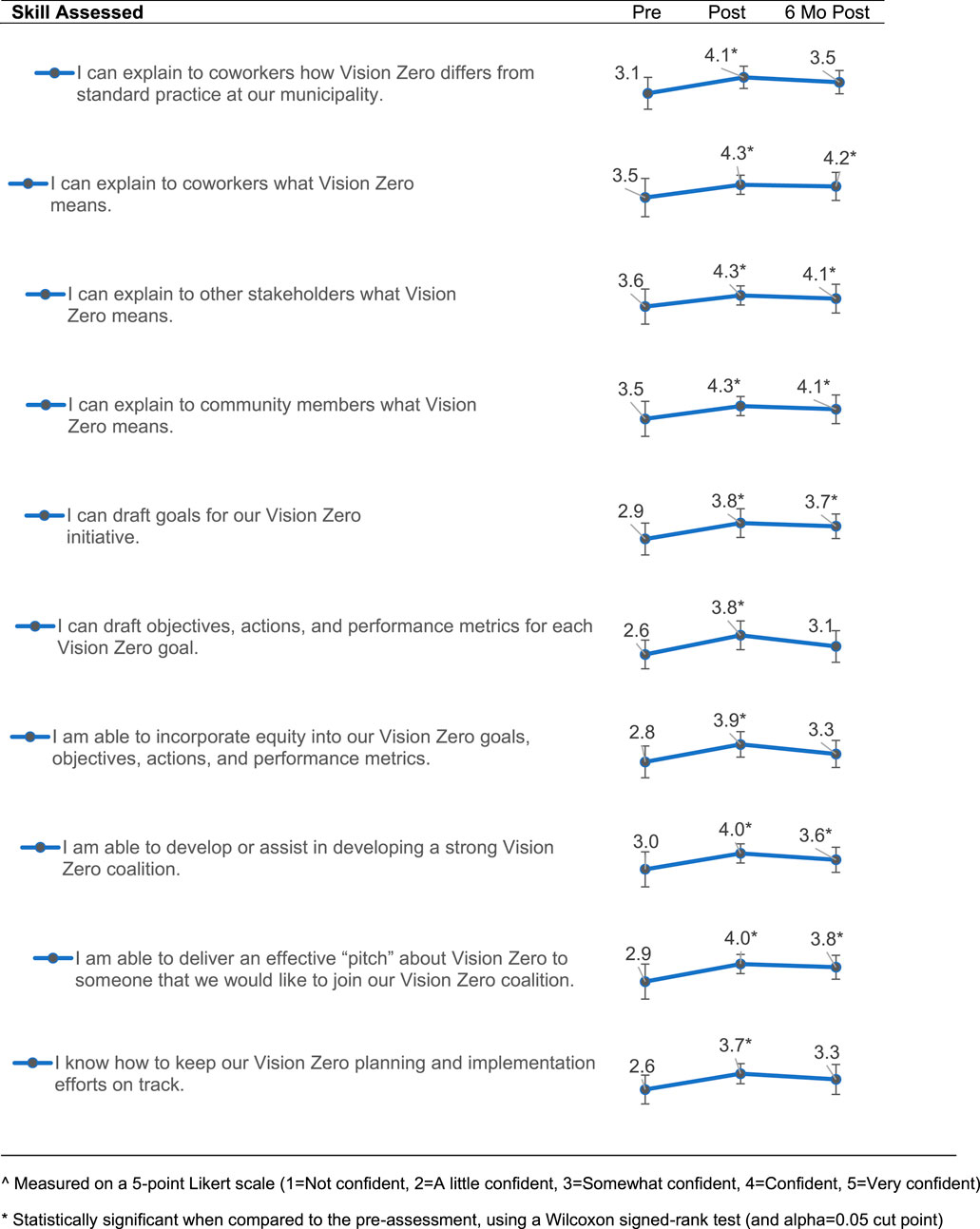

Self-reported confidence in skills was measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not confident, 2 = a little confident, 3 = somewhat confident, 4 = confident, and 5 = very confident) (Figure 1). The highest confidence in skills pre-Institute was reported for participants’ ability to explain what Vision Zero means to coworkers (mean: 3.5; standard deviation (SD): 1.2), other stakeholders (mean: 3.6; SD: 1.1), and community members (mean: 3.5; SD: 1.1). Measures with the lowest mean confidence scores included participants’ self-reported ability to draft objectives, actions, and performance metrics for Vision Zero goals (mean: 2.6; SD: 0.9), knowing how to keep Vision Zero planning and implementation efforts on track (mean: 2.6; SD: 1.0), and knowing how to incorporate equity into Vision Zero goals, objectives, actions, and performance metrics (mean: 2.8; SD: 1.0). Average self-reported confidence in skills increased notably from pre-Institute to immediately post-Institute, with increases in average scores ranging from 0.7 to 1.2 points. Post-Institute average scores ranged from 3.7 to 4.3. The largest increases occurred for feeling confident in drafting Vision Zero-related objectives, actions, and performance metrics (pre, mean: 2.6, SD: 0.9; post, mean: 3.8, SD: 0.9), incorporating equity into Vision Zero goals, objectives, actions, and performance metrics (pre, mean: 2.8, SD: 1.0; post, mean: 3.9, SD: 0.8), delivering an effective “pitch” about Vision Zero (pre, mean: 2.9, SD: 1.1; post, mean: 4.0, SD: 0.6), and knowing how to keep Vision Zero planning and implementation efforts on track (pre, mean: 2.6, SD: 1.0; post, mean: 3.7, SD: 0.7). All increases from pre-to immediately post-Institute were statistically significant.

FIGURE 1. Change in self-reported skills between Vision Zero Leadership pre, immediate post, and 6-month post assessments.

For all measures, average confidence in skills decreased from immediately post-Institute to 6 months post-Institute but generally remained greater than average scores pre-Institute (Figure 1). While some changes in measures at 6 months no longer remained statistically significant, as compared to pre-Institute, a number of measures remained significant, including increases in confidence related to explaining to coworkers and community members what Vision Zero means, in drafting Vision Zero goals, and in developing a strong coalition and effective “pitch” to help recruit individuals.

3.3.2 Collaboration and cooperation

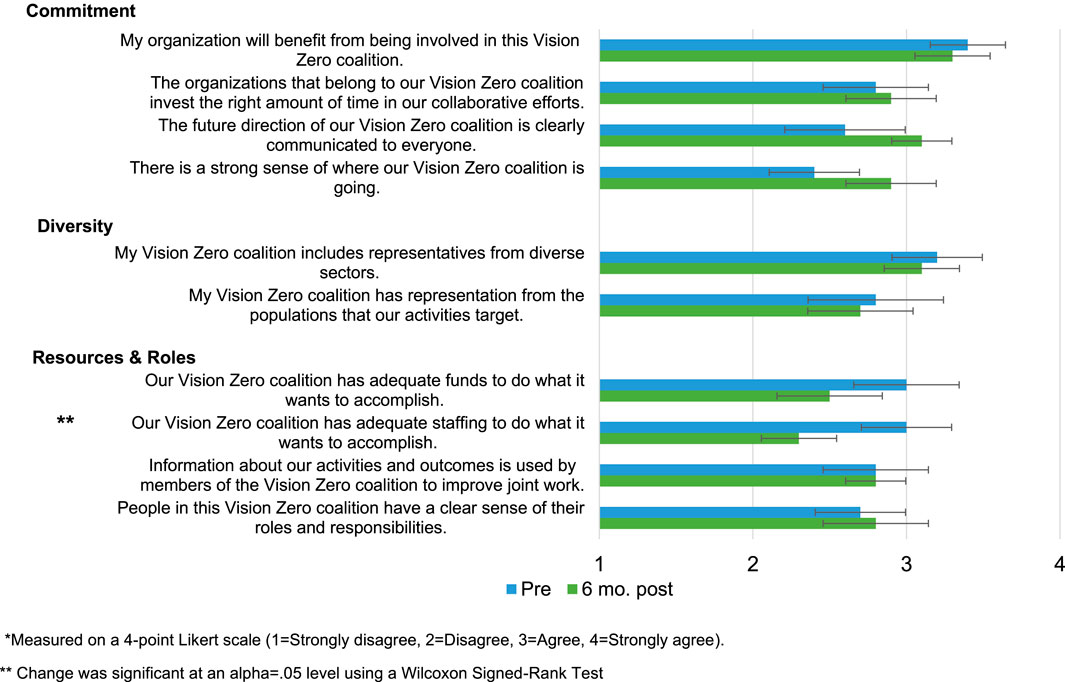

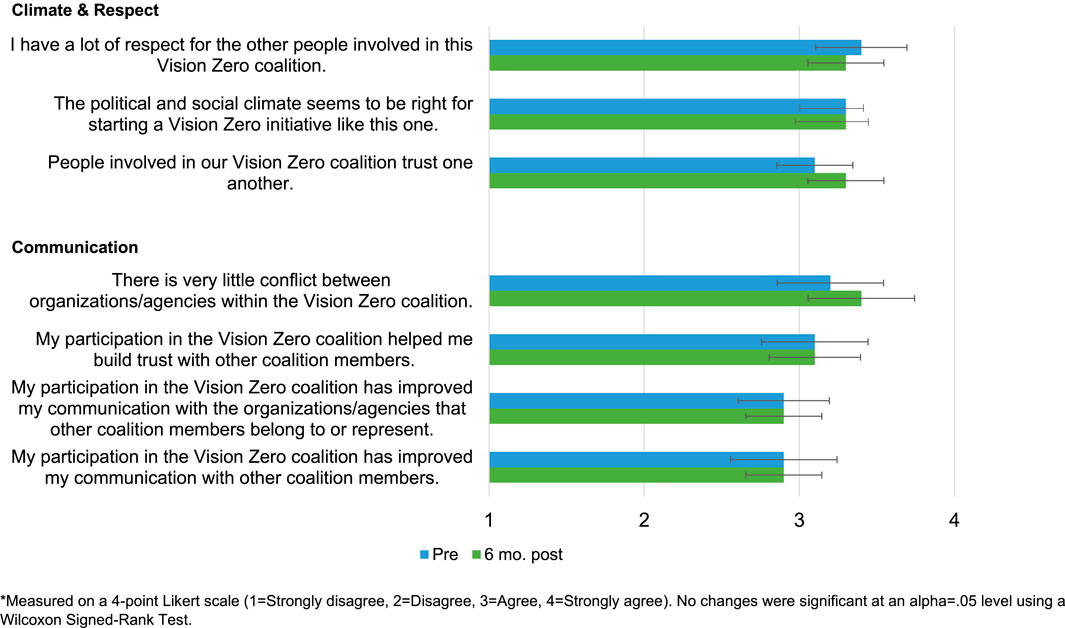

Collaboration and cooperation measures were assessed prior to the Institute and 6 months following the Institute on a four-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = agree, and 4 = strongly agree). Figures 2, 3 display representative measures for each domain assessed. A complete list of all 40 measures with means and changes between pre- and 6-month post-Institute periods is available in the Supplementary Table S1.

FIGURE 2. Changes* in perceived coalition commitment, diversity, and resources between Vision Zero Leadership Institute and 6-month post-assessment.

FIGURE 3. Changes* in perceived coalition climate, communication, and respect between Vision Zero Leadership Institute and 6-month post-assessment.

There was little change in coalition commitment, diversity, climate, respect, and communication across the 6-month period (Figures 2, 3). Several measures maintained high agreement across time points, including feeling like one’s organization would benefit from being involved in the coalition (pre, mean: 3.4, SD: 0.5; 6 months post, mean: 3.3, SD: 0.5); that one’s coalition includes representatives from diverse sectors (pre: 3.2, SD: 0.6; 6 months post: 3.1, SD: 0.5); that there was a lot of respect for the people involved in the coalition (pre: 3.4, SD: 0.5; 6 months post: 3.3, SD: 0.5); that the political and social climate is right for a Vision Zero coalition (pre: 3.3, SD: 0.4; 6 months post: 3.3, SD: 0.5); that people trust one another within the coalition (pre: 3.1, SD: 0.4; 6 months post: 3.3, SD: 0.5); and that there is little conflict between organizations within the coalition (pre: 3.2, SD: 0.4; 6 month post: 3.4, SD: 0.5). While not statistically significant, notable movement in mean agreement occurred for a few measures across time, including increased agreement for feeling like the future direction of the coalition is clearly communicated to everyone (pre, mean: 2.6, SD: 0.8; 6 months post, mean: 3.1, SD: 0.4) and decreased agreement for feeling like the coalition has adequate funds to do what it wants to accomplish (pre: 3.0, SD: 0.7; 6 months post: 2.5, SD: 0.7). Agreement also declined for feeling like the coalition had adequate staffing to do what it wants to accomplish (pre, mean: 3.0, SD: 0.6; 6 months post, mean: 2.3, SD: 0.5).

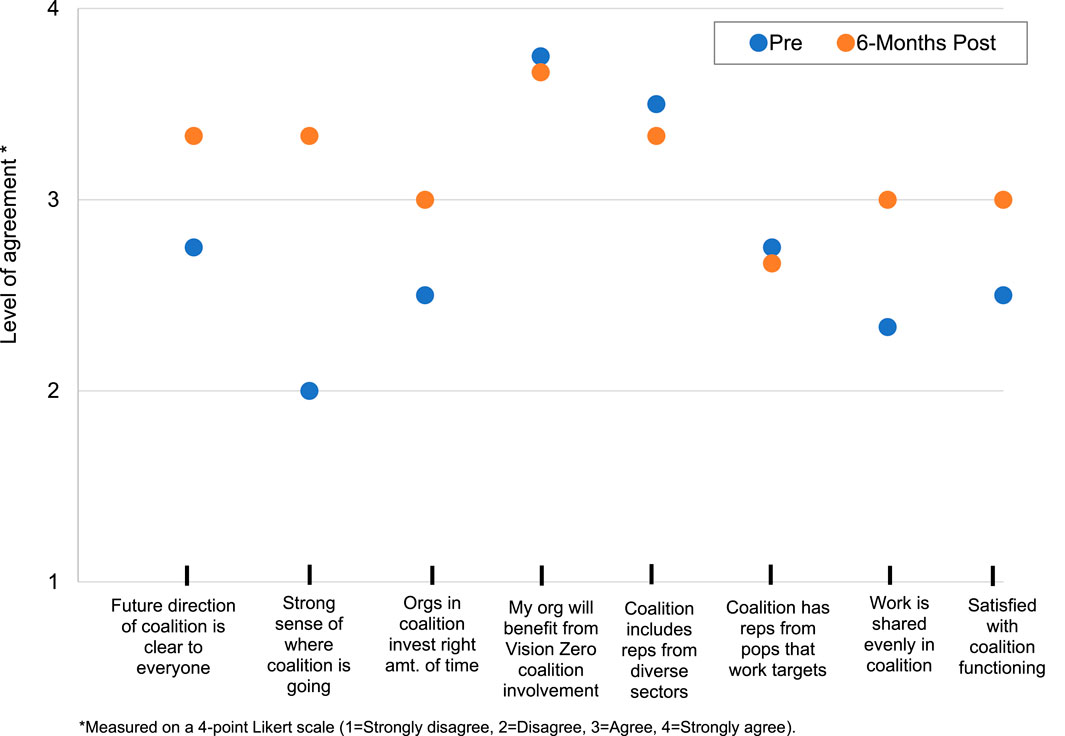

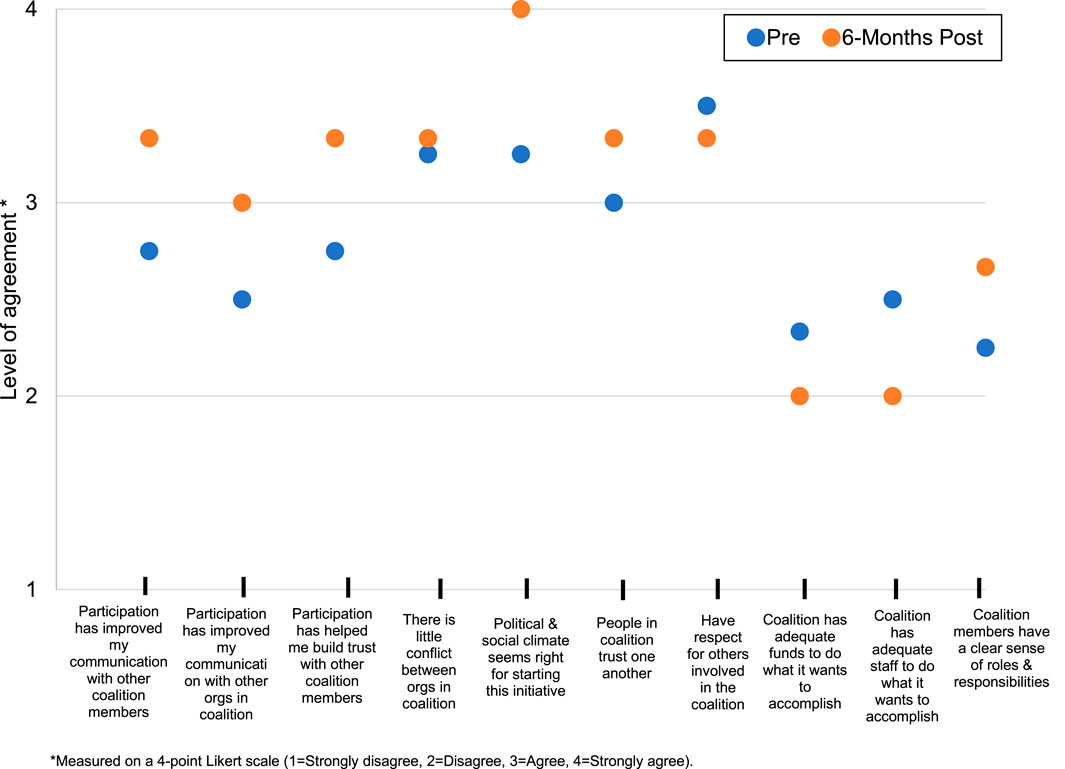

Finally, collaboration and cooperation measures can be used within teams to pinpoint areas for future work and growth. Figures 4, 5 display a sample of measures assessed pre-Institute and 6 months post-Institute for one team (n = 4 persons) to demonstrate how this could be used. The assessment revealed increased agreement over time across several measures, including in coalition members’ belief that the future direction of the coalition was clear, that they had a strong sense of where they were going, that work was shared among members, that participation improved communication and trust with other members and organizations, and that the political and social climate was right for the starting the initiative (indicated by vertical change between blue and green dots). Areas requiring targeted focus for improvement, as indicated by 6-month post-Institute averages either falling or remaining below 3.0, included ensuring that the coalition has representatives from the populations that its work targets, has adequate funds and staff to accomplish its goals, and that members have a clear sense of their roles and responsibilities.

FIGURE 4. Team-specific change in perceived coalition commitment, diversity, and functioning between Vision Zero Leadership Institute and 6-month post-assessment.

FIGURE 5. Team-specific change in perceived coalition communication, trust, climate, and resources between Vision Zero Leadership Institute and 6-month post-assessment.

3.3.3 Satisfaction with the Institute

Responses to questions assessing satisfaction with the Institute content and materials revealed a high level of satisfaction (Supplementary Figure S1). The average agreement among participants exceeded 3.0 on all questions, indicating moderate to strong agreement, including for questions about usefulness of having a coach or facilitator assigned to each team, the relevance of materials to their wok, the clarity of materials, and their likelihood of recommending the Institute to others.

4 Discussion

Implementation of Vision Zero and a Safe Systems approach requires effective collaboration across partners that influence and shape transportation systems, decisions, and outcomes, including partners from engineering, planning, public health, law enforcement, policymaking, and advocacy (Tingvall and Haworth, 1999; Johansson, 2009; Vision Zero Network, 2017a; Vision Zero Network, 2017b; Kim et al., 2017). While often recognized as a core principle of Vision Zero and a Safe Systems approach, little guidance and few resources exist on effective collaboration or coalition building within this context. We described our creation of an intensive Institute, grounded in a well-established framework of coalition development and maintenance. The Institute was designed to sit within a larger mutual learning and peer support model and to specifically train multidisciplinary Vision Zero teams in robust coalition development and planning processes, including collaborative goal setting.

For the eight teams that attended the Institute, evaluation measures revealed that participants’ average confidence in conveying key Vision Zero principles to different audiences, drafting Vision Zero goals, creating a strong coalition, and “pitching” Vision Zero to others increased immediately following the Institute, with increases in confidence sustained for at least 6 months following the Institute. Consistent with growth in goal setting confidence, we also found increased agreement, across the 6 months following the Institute, in feeling like the future direction of one’s coalition was clearly communicated to its members. Additionally, we observed an evolution in goal setting across teams during the Institute, with an increased focus on collaboration and recognized need for larger engagement to achieve outcomes. While there was little movement in perceived coalition collaboration and cooperation measures across the 6 months following the Institute, several measures of average collaboration and coalition were at a high level prior to Institute (e.g., having a high level of trust and respect and low level of conflict). Finally, potentially related to growth in clarifying coalition goals and the future coalition direction, we observed an average decline in confidence for feeling like the coalition had the staffing and funds available to support what they wanted to accomplish.

Prior research has indicated that the CCAT is a robust model for framing coalition development and processes in order to achieve complex health and social change (Butterfoss and Kegler, 2002; Kegler et al., 2010; Kegler And Swan, 2011; Sharma And Smith, 2011); however, it has received little attention in the area of transportation safety (Harooni and Ghaffari, 2021). This intensive Institute was built upon a CCAT foundation for coalition development within a Vision Zero and Safe Systems approach, and we found that the application of this model was associated with an increase in participants’ confidence in several critical skills related to coalition development and initiative planning processes. While confidence in skills declined 6 months post-Institute, confidence generally remained greater than pre-Institute. Research indicates that follow-up supports are critical to maintaining skills developed during a training, with effective supports including action plans, performance assessments, peer meetings, and technical support to maintain knowledge gained and ensure successful transfer into practice (Tannenbaum and Yukl, 1992; Richman-Hirsch, 2001; Martin, 2010). The Institute itself included elements to support action planning through translation of Institute principles into specific goals, objectives, and actions pertinent to the coalitions’ Vision Zero work. Additionally, the Institute sat within a larger model of peer mentoring, regular technical assistance, and monitoring of activities along a Vision Zero and Safe Systems implementation framework. These activities likely also supported maintenance of skill development; however, further research testing the effect of different components (e.g., Institute, Institute + supports) offered to coalitions is needed to disentangle effects on skill development and maintenance.

A central focus of the Institute was on goal development to help communities advance their Vision Zero planning and implementation processes, while weaving in principles and skills learned at the Institute. Prior research indicates that collaborative goal setting across multidisciplinary stakeholders is important for supporting coalition performance by providing the group with structure and connection, strengthening shared beliefs, and enhancing collective efficacy (Ericksen and Dyer, 2004; Kerr and Tindale, 2004; Stokols et al., 2008). Research also indicates that the presence of collaborative team goals, as compared to not having a goal or having a poorly defined goal, can enhance team or coalition performance by elevating member efforts and prompting increased communication and cooperation (Guzzo and Dickson, 1996; Stokols et al., 2008). Coalitions that define clear goals and objectives, agree on shared principles, and reach consensus on issues have been shown to face fewer collaboration-related difficulties (Butterfoss et al., 1993; Israel et al., 1998; Stokols, 2006; Stokols et al., 2008). We found that multidisciplinary teams generally entered the Institute with an abstract idea of a goal or with no goals for their near-term work, as well as with several challenges, including those related to building a shared understanding of a Safe Systems approach, determining how best to keep a task force or coalition engaged, growing a partnership network, and knowing where to start as a new Vision Zero coalition. We found that using a guided goal development process with facilitators and prompts, coalition goals evolved over the course of the Institute. Goals at the end of the Institute included a focus on diversifying coalition membership, authentically listening to and collaborating with communities when designing and implementing Vision Zero-related projects, and increasing awareness of road traffic injury to build community support for action. Given evidence on collaborative goal setting as a critical component of multidisciplinary coalition success (Stokols et al., 2008), we intend to continue to support guided goal setting work in future iterations of the Institute, providing protected time for collaborative goal defining and refining to ensure that the Safe Systems principle of shared responsibility is exemplified.

While confidence in skills increased and goal setting evolved across the Institute and beyond, measures of coalition collaboration and cooperation revealed little change in the 6 months following the Institute. There was general agreement across time that coalitions had a high level of respect and trust and a low level of conflict, that organizations within the coalition benefited from involvement, and that the political and social climate was right for a Vision Zero initiative. Additionally, participants average agreement that the future direction of the coalition was clearly communicated to everyone grew from prior to the Institute to 6 months post-Institute. This finding is consistent with the observed growth in skill development in goal setting and evolution in goal setting across the Institute. Notably, we also observed decreased agreement in feeling like one’s coalition has adequate funds and staffing to do what it wants to accomplish. Given that many teams attending the Institute were at the outset of their Vision Zero work, this is not unexpected and is common among new coalitions (McCullough et al., 2017). Most teams were focused on forming robust coalitions, discussing what they wanted to achieve together, and conducting goal setting and planning, and as these components became clearer, the resources needed to accomplish this work may have also been clarified. Additional work to support strategies around financing and resource acquisition will be an important next step for future trainings. Finally, in addition to using these collaboration and cooperation measures to support identification of targeted areas for larger team trainings, prior research has demonstrated the utility of coalition or team-specific collaboration assessments, as depicted in this paper (Figures 4, 5), for regular appraisal of areas requiring targeted team discussion and action (Ziff et al., 2010; Perrault et al., 2011; McCullough et al., 2017; Wells et al., 2021).

This evaluation should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, given resource constraints, we did not have similar measures on Vision Zero teams or coalitions who did not attend the Institute. Therefore, we were unable to disentangle effects of the Institute on changes in collaboration and cooperation over time from the natural progression of a Vision Zero coalition over time, or other effects. Future work, including not only following an unexposed comparison group but also assessing different types or components of supports for Vision Zero teams, could help determine the most effective models for supporting Vision Zero and Safe Systems efforts within multidisciplinary groups. Second, we did not have measures of validity and reliability on the survey items used for this specific population; however, the tools from which we derived measures have been used extensively in other populations and have had good psychometric properties (Mattessich et al., 2001; Patterson et al., 2004; Patterson et al., 2005; Ziff et al., 2010; Nordgård, 2011; Schneider et al., 2013; Calancie et al., 2017; McCullough et al., 2017; Calancie et al., 2018a; Calancie et al., 2018b; Wells et al., 2021). Third, response rates for the 6-month post-Institute survey were low. Pre- and immediately post-Institute surveys were conducted during Institute time, likely contributing to high response rates. However, despite multiple reminders and a prize for the team with the highest response rate, the 6-month post-Institute survey had a low response rate, with one team having no responses to the 6-month post-Institute survey and all other teams experiencing a drop in the number of responses. Therefore, findings should be interpreted with this in mind. To examine this further, we compared pre- and immediately post-Institute measure means for respondents who did vs. did not respond to the 6-month post-Institute survey. Means were very similar with no notable differences (all differences were ≤ |0.3|), indicating that 6-month non-responders were likely not notably different from those who did respond. Finally, the entire Institute was conducted in a virtual setting due to the COVID-19 pandemic; therefore, findings may not generalize to other formats. Future research should examine the effectiveness of different formats (e.g., in-person, remote, hybrid) for delivering this type of intensive multidisciplinary team-based training.

Vision Zero and Safe Systems involve intentional movement towards a more collaborative approach to transportation safety and encourage utilization of perspectives and skills across disciplines (Tingvall and Haworth, 1999; Johansson, 2009; Vision Zero Network, 2017a; Vision Zero Network, 2017b; Kim et al., 2017). While collaboration and cooperation are generally regarded as foundational to Vision Zero work, there is little guidance or support for how best to initiate or structure Vision Zero collaboration, conduct collaborative goal setting, and align tangible action across organizations. We described the development of a novel Vision Zero Leadership Team Training Institute, built from robust coalition action theory. Overall, the Vision Zero Leadership Team Training Institute provided a promising model for building tangible skills in Vision Zero and Safe Systems planning and implementation in a collaborative manner. We encourage further testing of this model with Vision Zero communities and coalitions of different sizes and at different stages of planning and implementation, including examining the extent to which such a model contributes to improved long-term Vision Zero and Safe Systems planning and implementation processes to ultimately improve road safety outcomes.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Institutional Review Board (IRB approval #21-1388). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

RN, SL, EK, SH, KH, KJ, and KE designed and facilitated the Leadership Institute. KE led the conceptualization and drafting of tailored evaluation questions. RN, SL, EK, and KE contributed to the conception and design of the study. KE prepared the data. KE and RN analyzed the data. RN drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revisions and read and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This project was supported by the Collaborative Sciences Center for Road Safety (www.roadsafety.unc.edu), a U.S. Department of Transportation National University Transportation Center (Award No. 69A3551747113). Support was also provided by the North Carolina Governor’s Highway Safety Program (Project No. 2000049994) and the UNC Injury Prevention Research Center, which is supported by an award (5R49/CE003092) from the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The funding sources played no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants, team facilitators, and guest speakers of the first annual North Carolina Vision Zero Leadership Team Training Institute for their tireless work towards Vision Zero and their contributions to the Institute.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/ffutr.2023.923786/full#supplementary-material

References

Abel, H. M., Kraft, K., Simon, H., Isidro, C., and Mennesson, M. (2019). Walking and biking perspectives on active and sustainable transportation: National complete streets coalition, safe routes to school, and America walks. Inst. Transp. Eng. ITE J. 89, 29–34.

Allen, N. E., Javdani, S., Lehrner, A. L., and Walden, A. L. (2012). “Changing the text”: Modeling council capacity to produce institutionalized change. Am. J. Community Psychol. 49, 317–331. doi:10.1007/s10464-011-9460-z

Belin, M. A., Tillgren, P., and Vedung, E. (2012). Vision Zero–a road safety policy innovation. Int. J. Inj. Contr Saf. Promot 19, 171–179. doi:10.1080/17457300.2011.635213

Block, P. (2008). Community: The structure of belonging. San Francisco, California: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Butterfoss, F. D., Goodman, R. M., and Wandersman, A. (1993). Community coalitions for prevention and health promotion. Health Educ. Res. 8, 315–330. doi:10.1093/her/8.3.315

Butterfoss, F. D., Goodman, R. M., and Wandersman, A. (1996). Community coalitions for prevention and health promotion: Factors predicting satisfaction, participation, and planning. Health Educ. Q. 23, 65–79. doi:10.1177/109019819602300105

Butterfoss, F. D., and Kegler, M. C. (2002). “Toward a comprehensive understanding of community coalitions: Moving from practice to theory,” in Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research: Strategies for improving public health.

Butterfoss, F. D. (2004). The coalition technical assistance and training framework: Helping community coalitions help themselves. Health Promot Pract. 5, 118–126. doi:10.1177/1524839903257262

Calancie, L., Allen, N. E., Ng, S. W., Weiner, B. J., Ward, D. S., Ware, W. B., et al. (2018a). Evaluating food policy councils using structural equation modeling. Am. J. Community Psychol. 61, 251–264. doi:10.1002/ajcp.12207

Calancie, L., Allen, N. E., Weiner, B. J., Ng, S. W., Ward, D. S., and Ammerman, A. (2017). Food policy council self-assessment tool: Development, testing, and results. Prev. Chronic Dis. 14, 160281. doi:10.5888/pcd14.160281

Calancie, L., Cooksey-Stowers, K., Palmer, A., Frost, N., Calhoun, H., Piner, A., et al. (2018b). Toward a community impact assessment for food policy councils: Identifying potential impact domains. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 8, 1–14. doi:10.5304/jafscd.2018.083.001

Calancie, L., Frerichs, L., Davis, M. M., Sullivan, E., White, A. M., Cilenti, D., et al. (2021). Consolidated Framework for Collaboration Research derived from a systematic review of theories, models, frameworks and principles for cross-sector collaboration. PLoS One 16, e0244501. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0244501

Ericksen, J., and Dyer, L. (2004). Right from the start: Exploring the effects of early team events on subsequent project team development and performance. Adm. Sci. Q. 49, 438–471. doi:10.2307/4131442

Guzzo, R. A., and Dickson, M. W. (1996). Teams in organizations: Recent research on performance and effectiveness. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 47, 307–338. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.47.1.307

Harooni, J., and Ghaffari, M. (2021). Moving knowledge to action: Applying community coalition action theory (CCAT) to bus seat belt usage. J. Lifestyle Med. 11, 8–12. doi:10.15280/jlm.2021.11.1.8

Hughes, B. P., Anund, A., and Falkmer, T. (2015). System theory and safety models in Swedish, UK, Dutch and Australian road safety strategies. Accid. Analysis Prev. 74, 271–278. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2014.07.017

Israel, B. A., Schulz, A. J., Parker, E. A., and Becker, A. B. (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 19, 173–202. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173

Johansson, R. (2009). Vision Zero – implementing a policy for traffic safety. Saf. Sci. 47, 826–831. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2008.10.023

Kegler, M. C., Rigler, J., and Honeycutt, S. (2010). How does community context influence coalitions in the formation stage? A multiple case study based on the community coalition action theory. BMC Public Health 10, 90–11. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-90

Kegler, M. C., and Swan, D. W. (2012). Advancing coalition theory: The effect of coalition factors on community capacity mediated by member engagement. Health Educ. Res. 27, 572–584. doi:10.1093/her/cyr083

Kegler, M. C., and Swan, D. W. (2011). An initial attempt at operationalizing and testing the community coalition action theory. Health Educ. Behav. 38, 261–270. doi:10.1177/1090198110372875

Kerr, N. L., and Tindale, R. S. (2004). Group performance and decision making. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 55, 623–655. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142009

Khorasani-Zavareh, D. (2011). System versus traditional approach in road traffic injury prevention: A call for action. J. Inj. Violence Res. 3, 61. doi:10.5249/jivr.v3i2.128

Kim, E., Muennig, P., and Rosen, Z. (2017). Vision zero: A toolkit for road safety in the modern era. Inj. Epidemiol. 4, 1. doi:10.1186/s40621-016-0098-z

Martin, H. J. (2010). Improving training impact through effective follow-up: Techniques and their application. J. Manag. Dev. 29, 520–534. doi:10.1108/02621711011046495

Mattessich, P., Murray-Close, M., and Monsey, B. (2001). Wilder collaboration factors inventory. St. Paul, MN: Wilder Research.

Mccullough, L., Jacobs, L., Orzech, K., Farrell, V., Mcdonald, D., Florian, T. A., et al. (2017). Using the wilder collaboration factors inventory to assess SNAP-ed coalitions in Arizona: Results from four counties. FASEB J. 31, 30–530.5. doi:10.1096/fasebj.31.1_supplement.30.5

Naumann, R. B., Sandt, L., Kumfer, W., Lajeunesse, S., Heiny, S., and Lich, K. H. (2020). Systems thinking in the context of road safety: Can systems tools help us realize a true "Safe Systems" approach? Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 7, 343–351. doi:10.1007/s40471-020-00248-z

Nordgård, M. (2011). Validating the organizational climate measure for Norwegian universities and colleges (NOCM_UH). Master's Thesis. Oslo, Norway: University of Oslo.

Organisation For Economic Co-Operation And Development, (2008). Towards zero: Ambitious road safety targets and the safe system approach.

Organisation For Economic Co-Operation And Development, (2016). Zero road deaths and serious injuries: Leading a paradigm shift to safe systems.

Patterson, M. G., West, M. A., Shackleton, V. J., Dawson, J. F., Lawthom, R., Maitlis, S., et al. (2005). Validating the organizational climate measure: Links to managerial practices, productivity and innovation. J. Organ. Behav. 26, 379–408. doi:10.1002/job.312

Patterson, M., West, M., Shackleton, V., Lawthom, R., Maitlis, S., Robinson, D., et al. (2004). Development and validation of an organizational climate measure. Birmingham, UK: Aston University.

Perrault, E., Mcclelland, R., Austin, C., and Sieppert, J. (2011). Working together in collaborations: Successful process factors for community collaboration. Adm. Soc. Work 35, 282–298. doi:10.1080/03643107.2011.575343

Richman-Hirsch, W. L. (2001). Posttraining interventions to enhance transfer: The moderating effects of work environments. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 12, 105–120. doi:10.1002/hrdq.2.abs

Roussos, S. T., and Fawcett, S. B. (2000). A review of collaborative partnerships as a strategy for improving community health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 21, 369–402. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.369

Rutgers University Center For Advanced Infrastructure And Transportation. 2022. Effectively engaging stakeholders in a safe system approach to transform traffic safety culture. [Online]. Available: [Accessed].

Schneider, B., Ehrhart, M. G., and Macey, W. H. (2013). Organizational climate and culture. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 64, 361–388. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143809

Sharma, M., and Smith, L. (2011). Community coalition action theory and its role in drug and alcohol abuse interventions. J. Alcohol Drug Educ. 55, 3–7.

Stokols, D., Misra, S., Moser, R. P., Hall, K. L., and Taylor, B. K. (2008). The ecology of team science: Understanding contextual influences on transdisciplinary collaboration. Am. J. Prev. Med. 35, S96–S115. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.003

Stokols, D. (2006). Toward a science of transdisciplinary action research. Am. J. Community Psychol. 38, 79–93. doi:10.1007/s10464-006-9060-5

Tannenbaum, S. I., and Yukl, G. (1992). Training and development in work organizations. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 43, 399–441. doi:10.1146/annurev.ps.43.020192.002151

Tingvall, C., and Haworth, N. (1999). “Vision Zero – an ethical approach to safety and mobility,” in Presented at the 6th ITE international conference - road safety & traffic enforcement: Beyond 2000.

U.S. Agency For International Development (2016). Technical Note: The 5 Rs framework in the program cycle. [Online]. Available: [Accessed].

Vision Zero Network (2022). How does Vision Zero differ from the traditional approach to traffic safety? [Online]. Available: [Accessed].

Vision Zero Network (2017a). Moving from vision to action: Fundamental principles, policies and practices to advance vision zero in the U.S.

Wells, R., Yates, L., Morgan, I., Derosset, L., and Cilenti, D. (2021). Using the wilder collaboration factors inventory to strengthen collaborations for improving maternal and child health. Matern. Child. Health J. 25, 377–384. doi:10.1007/s10995-020-03091-2

Keywords: vision zero, safe system, coalition, road safety, injury prevention, collaboration, action plan, transportation planning

Citation: Naumann RB, LaJeunesse S, Keefe E, Heiny S, Hassmiller Lich K, Jones K and Evenson KR (2023) A novel Vision Zero leadership training model to support collaboration and strategic action planning. Front. Future Transp. 4:923786. doi: 10.3389/ffutr.2023.923786

Received: 19 April 2022; Accepted: 06 January 2023;

Published: 25 January 2023.

Edited by:

Meleckidzedeck Khayesi, World Health Organization, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Jidong J. Yang, University of Georgia, United StatesHamid Safarpour, Medical University of Ilam, Iran

Copyright © 2023 Naumann, LaJeunesse, Keefe, Heiny, Hassmiller Lich, Jones and Evenson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rebecca B. Naumann, Uk5hdW1hbm5AdW5jLmVkdQ==

Rebecca B. Naumann

Rebecca B. Naumann Seth LaJeunesse

Seth LaJeunesse Elyse Keefe

Elyse Keefe Stephen Heiny

Stephen Heiny Kristen Hassmiller Lich

Kristen Hassmiller Lich Ki’yonna Jones5

Ki’yonna Jones5 Kelly R. Evenson

Kelly R. Evenson