Abstract

Gliomas are a group of primary brain tumors, the most common and aggressive subtype of which is glioblastoma. Glioblastoma has a median survival of just 15 months after diagnosis. Only previous exposure to ionizing radiation and particular inherited genetic syndromes are accepted risk factors for glioma; the vast majority of cases are thought to occur spontaneously. Previous observational studies have described associations between several risk factors and glioma, but studies are often conflicting and whether these associations reflect true casual relationships is unclear because observational studies may be susceptible to confounding, measurement error and reverse causation. Mendelian randomization (MR) is a form of instrumental variable analysis that can be used to provide supporting evidence for causal relationships between exposures (e.g., risk factors) and outcomes (e.g., disease onset). MR utilizes genetic variants, such as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), that are robustly associated with an exposure to determine whether there is a causal effect of the exposure on the outcome. MR is less susceptible to confounding, reverse causation and measurement errors as it is based on the random inheritance during conception of genetic variants that can be relatively accurately measured. In previous studies, MR has implicated a genetically predicted increase in telomere length with an increased risk of glioma, and found little evidence that obesity related factors, vitamin D or atopy are causal in glioma risk. In this review, we describe MR and its potential use to discover and validate novel risk factors, mechanistic factors, and therapeutic targets in glioma.

The Public Health Burden of Glioma

Malignant gliomas are responsible for approximately 80% of all malignant brain tumors, with glioblastoma being the most prevalent histological subtype (Ostrom et al., 2014) (∼45% of all gliomas Ostrom et al., 2014; Visser et al., 2015). Although glioma is a relatively rare cancer, with ∼9,200 cases diagnosed each year in the United Kingdom (Cancer Research United Kingdom, 2015), the disease poses a serious health burden owing to its poor prognosis. The heterogeneous nature of the tumor cells makes the vast majority of gliomas surgically incurable (Kelly, 2010). Additionally, difficulty is faced as therapeutic agents need to penetrate the blood brain barrier (Azad et al., 2015). As a result the median survival rate of grade III gliomas is two to 5 years (Wen and Kesari, 2008) and just 15 months for glioblastoma (WHO grade IV) (Stupp et al., 2009). The 5-year survival for glioma varies, from approximately 58% for ependymoma patients to approximately 5% for glioblastoma patients (Ostrom et al., 2014; Visser et al., 2015; Cancer Research United Kingdom, 2016).

Risk Factors for Glioma

Accepted Risk Factors for Glioma

The only environmental factor consistently associated with glioma risk is moderate to high exposure to ionizing radiation, accounting for only a small proportion of cases (Bondy et al., 2008; Braganza et al., 2012; Urbanska et al., 2014). Evidence was first provided from the Israeli Tinea Capitus cohort of children who had undergone radiation therapy for a benign medical condition (Sadetzki et al., 2005). This was supported by data from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study that followed-up 14,361 children and adolescents (aged < 21 at initial diagnosis) who had survived for 5 years (Neglia et al., 2006). During follow-up, 40 gliomas were diagnosed, compared to an anticipated incidence of 4.62 (standardized incidence ratios (SIR) = 8.66, 95% confidence interval (CI) 6.24–11.6). These gliomas arose at a median of 9 years after original diagnosis. In a case-control analysis (with 4 controls per case, matched on age at diagnosis, sex and time since diagnosis, and the analysis adjusted for original cancer diagnosis) the odds ratio (OR) for glioma amongst children who underwent radiation therapy vs. those who did not was 6.78 (95% CI 1.54–29.7) (Neglia et al., 2006). The authors found that the risk of glioma per Gray of radiation was greatest among children who received radiation therapy at less than 5 years of age. After adjustment for radiation dose, neither original cancer diagnosis nor chemotherapy was associated with risk (Neglia et al., 2006). Taylor et al. (2010) carried out a study of 17,980 participants who had survived at least 5 years after diagnosis of childhood cancer. In this study the risk of glioma increased linearly with dose of radiation (Taylor et al., 2010).

Rarely, glioma occurs in more than one family member, indicating a genetic susceptibility. This susceptibility is most often described within cases where inherited tumor syndromes are present, such as Li-Fraumeni syndrome, Turcot syndrome and neurofibromatosis type 1 (Louis et al., 2016). Kinnersley et al. (2018) reviewed glioma genome wide association study (GWAS) and summarized reported associations at the 27 glioma-risk SNPs (Kinnersley et al., 2018); genetic susceptibility loci are summarized in Table 1. These risk variants contribute to an increase in glioma risk; however, additional somatic mutations are a requisite for tumorigenesis in individuals with these germline variants or familial syndromes (Rice et al., 2016).

Table 1

| Gene | SNP | Alleles | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TERT | rs2736100 | T/G | 1.27 (1.19–1.37 |

| CCDC26 | rs4295627 | G/T | 1.36 (1.29–1.43) |

| CCDC26 | rs891835 | G/T | 1.24 (1.17–1.30) |

| CDKN2A/B | rs4977756 | A/G | 1.24 (1.19–1.30) |

| PHLDB1 | rs498872 | C/T | 1.18 (1.13–1.24) |

| RTEL1 | rs6010620 | G/A | 1.28 (1.21–1.35) |

| TP53 | rs78378222 | T/G | 2.35 (1.61–3.44) |

| CCDC26 | rs55705857 | A/G | 6.3 (4.6–8.8) |

| Near TERC | rs1920116 | G/A | 1.30 (1.19–1.42) |

| VTI1A | rs11196067 | A/T | 1.19 (1.12–1.27) |

| ZBTB16 | rs648044 | C/T | 1.25 (1.17–1.34) |

| Intergenic | rs12230172 | G/A | 1 1.23 (1.16–1.32) |

| POLR3B | rs3851634 | T/C | 1.23 (1.15–1.32) |

| ETFA | rs180159 | G/A | 1.36 (1.23–1.51) |

| JAK1 | rs12752552 | T/C | 1.22 (1.15–1.31) |

| MDM4 | rs4252707 | G/A | 1.19 (1.12–1.26) |

| AKT3 | rs12076373 | G/C | 1.23 (1.16–1.32) |

| Near IDH1 | rs7572263 | A/G | 1.20 (1.13–1.26) |

| LRIG1 | rs11706832 | A/C | 1.15 (1.09–1.20) |

| OBFC1 | rs11598018 | C/A | 1.14 (1.09–1.20) |

| Intergenic | rs11233250 | C/T | 1.24 (1.16–1.33) |

| MAML2 | rs7107785 | T/C | 1.16 (1.11–1.21) |

| AKAP6 | rs10131032 | G/A | 1.33 (1.22–1.44) |

| Near MPG | rs2562152 | A/T | 1.21 (1.13–1.29) |

| LMF1 | rs3751667 | C/T | 1.18 (1.12–1.25) |

| HEATR3 | rs10852606 | T/C | 1.18 (1.13–1.24) |

| SLC16A8 | rs2235573 | G/A | 1.15 (1.10–1.20) |

| Near TERC | rs3772190 | G/A | 1.11 (1.06–1.15) |

| TERT | rs10069690 | C/T | 1.61 (1.53–1.69) |

| EGFR | rs75061358 | T/G | 1.63 (1.50–1.76) |

| EGFR | rs723527 | A/G | 1.25 (1.20–1.31) |

| CCDC26 | rs55705857 | G/A | 3.39 (3.09–3.71) |

| CDKN2A/B | rs634537 | T/G | 1.37 (1.31–1.43) |

| VTI1A | rs11599775 | G/A | 1.16 (1.10–1.22) |

| ZBTB16 | rs648044 | A/G | 1.19 (1.13–1.25) |

| PHLDB1 | rs12803321 | G/C | 1.42 (1.35–1.49) |

| Intergenic | rs1275600 | T/A | 1.16 (1.10–1.21) |

| RFX4 | rs12227783 | A/T | 1.16 (1.08–1.24) |

| ETFA | rs77633900 | G/C | 1.35 (1.25–1.46) |

| TP53 | rs78378222 | T/G | 2.53 (2.19–2.91) |

| RTEL1 | rs2297440 | T/C | 1.48 (1.40–1.56) |

Summary of the genetic susceptibility loci identified by GWAS in Europeans.

Table 1 is a modified version of Table 1 in Kinnersley et al. (2018). The table describes the gene, the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), the allele and the odds ratio (OR) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI). ORs are reported with respect to the risk allele, highlighted in bold.

Other Postulated Risk Factors

There have been several risk factors that have been linked to the occurrence of glioma, though results from these investigations may be spurious because of the biases that pervade observational studies (Louis et al., 2016). A recently published systematic review presents risk factors for glioma onset that are shown to increase, decrease or have a null association with glioma risk (Quach et al., 2017).

Observational studies suggest that allergies (asthma, eczema, hay fever) are associated with lower glioma risk (Wigertz et al., 2007; Berg-Beckhoff et al., 2009; Amirian et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016) and, consistent with this, asthma-susceptibility genotypes are associated with a reduced risk of glioma (Schwartzbaum et al., 2005). Short term use of anti-inflammatory medicine has also been reported to reduce glioma risk (Scheurer et al., 2011); although other studies have found conflicting results (Daugherty et al., 2011; Gaist et al., 2013). The possible role of allergies in decreasing the risk of glioma, including glioblastoma, may be due to an increase in immune surveillance, which in turn may destroy damaged, pro-cancerous cells earlier (Scheurer et al., 2011; Safaeian et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2014). This hypothesis is supported by reports of a higher occurrence of glioma in HIV and AIDS patients (Blumenthal et al., 1999; Jukich et al., 2001; Hall and Short, 2009); as this is based on the result from a small number of studies with small sample sizes the estimate may be biased.

Brain tumors are observed to occur more often in Europeans compared with individuals of an African or Asian origin (McLendon et al., 1985; Kuratsu et al., 2001; Darefsky and Dubrow, 2009; Ostrom et al., 2013), an observation that has also been reported within children. Robertson et al. (2002) investigated ethnic variation in the incidence of adult brain cancer in 994,725 individuals over 10.5 years of follow-up. The authors identified 373 people who developed brain cancer (232 glioblastomas, 106 astrocytomas and 35 oligodendrogliomas) of whom 50 were of African ancestry and 323 of European ancestry. Age adjusted incidence rates (per 100,000 race specific-population/year) were 0.11 and 0.46 (p = 0.003) in the African and European populations, respectively. The authors report a significant difference in incidence rates for the three most common gliomas and suggest that glioma is more common in individuals of European ancestry than in individuals of African ancestry (Robertson et al., 2002). Other studies have reported that glioma occurs 3.5 times more often in Europeans compared to African Americans (Davis et al., 1999). The explanation for this observed ethnic discrepancy remains unclear and while it is possible that a genetic difference exists between the two groups (Mochizuki et al., 1999; Chen et al., 2001; Das et al., 2002), detection bias cannot be ruled out (Dubrow and Darefsky, 2011).

Certain occupations are reported to be linked with a higher risk of glioma, including physicians (Carozza et al., 2000; Krishnan et al., 2003; Pukkala et al., 2009), firefighters (Carozza et al., 2000; Krishnan et al., 2003) and farmers (Khuder et al., 1998; Zheng et al., 2001). Occupational exposure to metals such as arsenic and lead has attracted attention with respect to brain tumors as they are able to penetrate the blood brain barrier (Sunderman, 2001; Wang and Du, 2013; Liao et al., 2016). Exposure to lead has been associated with glioma risk (Anttila et al., 1996; van Wijngaarden and Dosemeci, 2006) and brain cancer mortality (Cocco et al., 1998; van Wijngaarden and Dosemeci, 2006). In a cohort study of 1,779,646 men and 1,066,346 women aged 25–64 years at baseline and subsequently followed for 19 years, an increased glioma risk was observed amongst men exposed to arsenic, mercury, and petroleum products (Navas-Acien et al., 2002). However, no relationship of lead, cadmium, nickel, chromium and iron with glioma risk was reported in a study of 1856 cases and 5189 controls (Parent et al., 2017). Other studies investigating the relationship between glioma and occupational exposure to metal (Samkange-Zeeb et al., 2010) or lead (Rajaraman et al., 2006; Bhatti et al., 2009), and between brain cancer more generally and lead (Lam et al., 2007) reported no strong evidence of a causal association.

There has been speculation that certain lifestyle choices, including alcohol intake, the use of drugs, or dietary exposure to nitrous compounds affect the risk of glioma; however, to date the evidence is inconclusive (Giles et al., 1994; Michaud et al., 2009; Kyritsis et al., 2011; Little et al., 2013; Shao et al., 2016; Tamimi and Juweid, 2017).

Mobile phone use has been speculated to be associated with brain tumor risk (Schüz et al., 2006). However, conflicting finding have also been reported (Frei et al., 2011). In a nationwide study involving Danish citizens aged 30 years or older (born after 1925), there was no evidence that mobile phone use increased brain tumor risk (Frei et al., 2011).

Other risk factors that are not discussed here have been investigated in relation to glioma risk, including but not limited to: Type 1 and type 2 diabetes, body mass index, birth weight, hypertension, height, birth weight, menarche (age at onset), menopause (age at onset), coffee/caffeine consumption, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, insulin-like growth factor 1, insulin-like growth factor binding protein, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, pesticide exposure, extremely low frequency magnetic fields, vitamin E, A and C levels (Preston-Martin and Mack, 1991; Kaplan et al., 1997; Houben et al., 2004; Linos et al., 2007; Holick et al., 2010; Kabat et al., 2011; Little et al., 2013; Malerba et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2014; Andersen et al., 2015; Li et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2015; Seliger et al., 2016a,b; Zhao et al., 2016; Wiedmann et al., 2017).

Observational Epidemiological Studies Vs. Mendelian Randomisation

Problems With Observational Epidemiological Studies for Identification of Causal Risk Factors

As described above, and in common with many other diseases, the search for risk factors for glioma has largely been based on observational cohort, case-control and cross-sectional studies (Lawlor et al., 2004). Numerous cases exist of seemingly robust observational associations between putative risk factors and disease outcomes; however, interventions to modify these risk factors do not produce the anticipated benefits under randomized controlled trial (RCT) conditions (Davey Smith and Hemani, 2014). One of the postulated reasons for this is the susceptibility of observational (non-experimental) studies to several biases (specifically, confounding, measurement error and reverse causation) that can generate spurious associations and which can be difficult to eradicate even through statistical adjustment (Davey Smith and Hemani, 2014).

A confounder is a factor that is a common cause of both the disease under consideration and the exposure of interest. Importantly, a confounder is not on the causal pathway between the exposure and outcome (Hammer et al., 2009). For instance, in 2002 an association had been established between alcohol intake and the incidence of 3.6% of all cancers (Boffetta et al., 2006; Testino, 2011) but it is still uncertain whether an association exists between any class of glioma and alcohol intake (Braganza et al., 2014; Qi et al., 2014). An observed association between glioma incidence and alcohol intake could be because individuals who consume more alcohol are more likely to smoke (Hart et al., 2010) and to adhere to an unhealthy life-style; (Sayon-Orea et al., 2011; Bendsen et al., 2013) thus, it could be these other factors that influence the risk of glioma rather than alcohol consumption per se (Sergentanis et al., 2015).

Reverse causation occurs when the disease outcome precedes, and leads to, the exposure rather than being a consequence of the exposure (Flegal et al., 2011). For example a higher level of blood glucose has been reported to be protective against glioma (Kitahara et al., 2014); however, an alternative explanation is that tumors take-up glucose, leading to low glucose levels (Schwartzbaum et al., 2017).

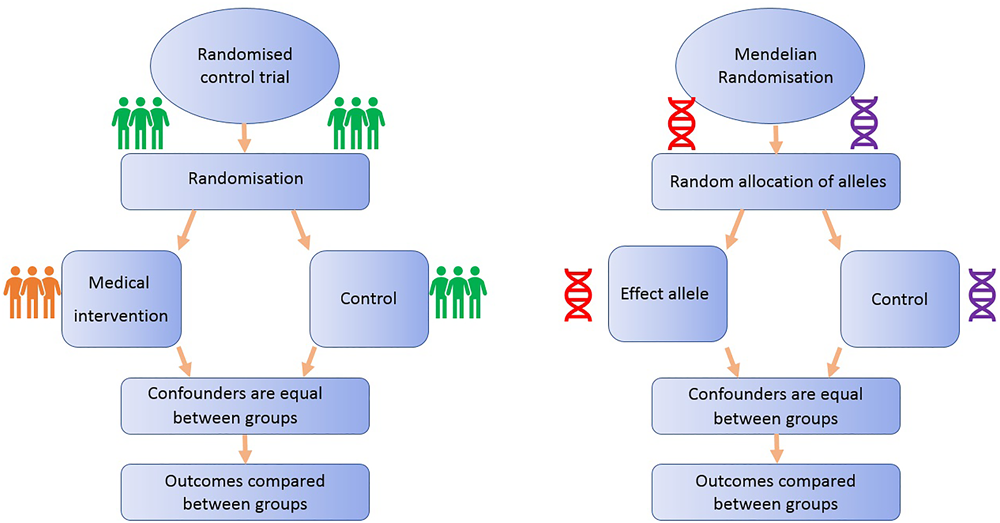

Mendelian Randomization Analogous to Randomized Control Trials (Figure 1)

FIGURE 1

Comparison of Mendelian randomization (MR) with randomized control trial. This demonstrates the analogy between a randomized control trial and a Mendelian randomized study.

Randomized controlled trials are considered the gold standard study design for inferring causality, as successful randomization, adequately blinded implementation of the intervention, high rates of follow-up and intention-to-treat analysis should yield results that are relatively free from the biases afflicting observational studies (Iturrieta-Zuazo and Walter, 2015). On the other hand, RCTs often reflect short-term exposures at one time point in life, with limited follow-up, and participants are usually not representative of general populations, a particularly important issue if the priority is to identify primary prevention targets (Meyer, 2010). Additionally, due to ethical, practical and financial reasons, it is not feasible to randomize people to every risk factor (Bochud and Rousson, 2010): e.g., exposure to power lines, mobile phone use or breastfeeding.

One method to appraise causality within observational epidemiology is the use of Mendelian randomization (MR). MR is a type of “instrumental variable” analysis that utilizes genetic variants, such as SNPs, that are robustly associated with an exposure as proxies for the risk factor of interest. The aim of MR is to strengthen causal inference in observational studies of associations between risk factors and disease (Lawlor et al., 2008).

All MR studies make use of germline genetic data as opposed to somatic data. Germline genetic variants tend to be randomly distributed with respect to most human traits in the general population. This is because of Mendel’s laws of inheritance (segregation, independent assortment) and the fixed nature of germline genotypes (Castle, 1903). Thus, germline genetic variants are less likely to be affected by the sorts of confounding factors that typically bias observational findings (Qi, 2009). Additionally, as germline genotype cannot be affected by the presence of disease, the generation of spurious results through reverse causation is avoided (Larsson et al., 2017). Germline genetic variants can thus be regarded as randomized proxies for an exposure of interest, in the same way that the allocation group in an RCT is a proxy for an intervention of interest (Figure 1). MR can exploit SNPs that are associated with modifiable risk factors to strengthen causal inference about the nature of relationships between risk factors and disease (Larsson et al., 2017).

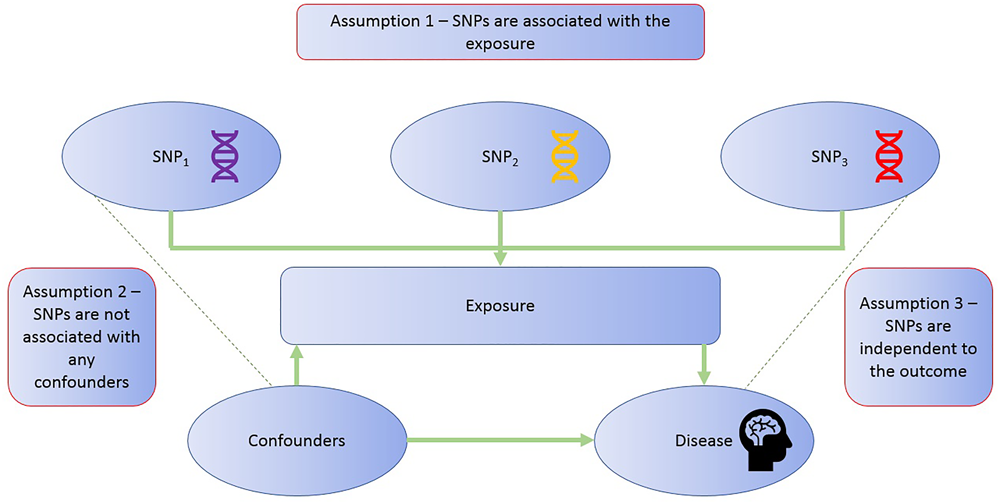

The application of MR involves three assumptions (Figure 2): (1) the genetic variants (“instruments”) are reliably associated with the risk factor of interest; (2) the genetic variants are independent of confounding factors (Didelez and Sheehan, 2007; VanderWeele et al., 2014); and (3) the genetic variants are only associated with the disease outcome through the risk factor of interest (Greenland, 2000; Lawlor et al., 2008). Within the constraints of these assumptions, genetic instruments (SNPs) can be used as proxies for a large range of cancer-related modifiable exposures. One-sample MR is the standard application of MR. There is one data set that contains all the data on the SNPs, exposure, and outcome for all participants (Haycock et al., 2016). Due to the rare nature of glioma, one-sample MR is likely to be statistically underpowered. As a result, MR techniques have been developed to allow analysis when genetic association studies are conducted in two separate samples sets: one set for the exposure of interest and one for the outcome (Inoue and Solon, 2010). This method is referred to as two-sample MR (Hartwig et al., 2016).

FIGURE 2

MR assumptions. The diagram illustrates the three assumptions of the MR methodology.

Like most diseases, glioma GWAS to date have examined genetic variation in relation to the causes of disease risk, using case-control study designs, as opposed to disease progression (Melin et al., 2017). The primary application of MR in glioma research has, therefore, focused primarily on causal effects of environmental exposures on disease risk (Walsh et al., 2015; Haycock et al., 2017; Disney-Hogg et al., 2018a; Takahashi et al., 2018), as opposed to survival. There are some instances where factors are involved in both disease incidence and progression, such as low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels for heart disease risk and recurrence (Ference et al., 2017), although such instances may be exceptional. Cases do exist where a risk factor for a disease is not implicated in progression, as has been proposed for the relationship between folate consumption and colon cancer (Kim, 2003). Thus, current case-control GWAS of glioma risk have the potential to inform on the underlying causal mechanisms of disease onset but (at the current time) may be less informative for discovering drug targets to improve glioma survival (Paternoster et al., 2017). The latter requires case-only GWAS that examine genetic variation in relation to disease progression, but such studies are currently rare (Melin et al., 2017). The most probable explanation for this is due to a research focus to determine mechanisms that cause disease incidence and because of the challenges inherent in collecting progression data (see section “Future of MR in research” below). At present, a few MR studies have been conducted that investigate progression of disease (Brunner et al., 2017) but none in glioma progression, which is required for the discovery of targets for improving glioma survival (Paternoster et al., 2017).

Mendelian randomization can be used to identify and investigate potential drug targets (Mokry et al., 2015; Zheng et al., 2017). A quarter of the drugs that enter clinical development fail due to their ineffectiveness (Ashburn and Thor, 2004; Arrowsmith and Miller, 2013). Current drug targets are authenticated using in-vitro and animal models, but these can fail to predict the potential benefits (or harms) in humans (Mokry et al., 2015; Zheng et al., 2017). Nelson et al. (2015) aimed to establish whether current genetic evidence could predict drug mechanisms. The authors reported that opting for targets that are genetically supported may result in twice the success rate in clinical development (Nelson et al., 2015). MR could substantially augment these methods (Mokry et al., 2015; Zheng et al., 2017). The theory is that specific genetic variants can be utilized to imitate the effects of targeting a protein pharmacologically. If the variant codes for a potential drug target that causes an alteration in activity of the encoded protein, the causal effect of the drug on disease can be assessed by MR (Sofat et al., 2010; Evans and Smith, 2015). Additionally, MR can be used to examine all pairwise associations between serum protein levels and disease risk (Sun et al., 2018). If a variant is identified that is robustly associated with levels of a serum protein that display a putative causal relationship with disease risk, methods can be employed to search for available drugs that cause an alteration in the levels of that protein (Corsello et al., 2017). As discussed, only case-control GWAS exist at present for glioma which may be less informative for the discovery of drug targets to improve survival (Paternoster et al., 2017).

Table 2 provides a summary of some of the different methods used to obtain MR estimates (Hemani et al., 2018).

Table 2

| Statistical Method | Description |

|---|---|

| Inverse-variance weighted (IVW) | Assumes causal estimate due to each SNP is the same (fixed effects IVW) or that if their effects differ that their deviations are balanced (random effects IVW) (Hemani et al., 2018). Gives an unbiased estimate when there is no horizontal pleiotropy (fixed effects IVW) or when horizontal pleiotropy is balanced (random effects IVW). |

| Maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) | Assumes effect of the exposure on the outcome due to each SNP is equal (fixed effects IVW makes the same assumption). A benefit of this method is that it might give more reliable results when measurement error in the SNP-exposure effect is present (Hemani et al., 2018). Gives an unbiased estimate when there is no horizontal pleiotropy or when horizontal pleiotropy is balanced (but variance of the estimate will be underestimated in the latter scenario). |

| Weighted median estimate (WME) | Takes the median effect of all SNPs. Returns an unbiased estimate if half the SNPs are valid instruments (Hemani et al., 2018). Requires a large number of instrumental SNPs otherwise method is underpowered. |

| Mode-based estimate (MBE) | SNPs are clustered into groups determined by similarity of causal effects. Returns the causal effect estimate based on the cluster that has the greatest number of SNPs (Hemani et al., 2018). Gives an unbiased estimate if the SNPs in the largest cluster are valid, even if most SNPs are invalid instruments. Requires a large number of instrumental SNPs otherwise method is underpowered. |

| MR-Egger | Modifies the IVW analysis by permitting a non-zero intercept, permitting the net-horizontal pleiotropic effect for all SNPs to be unbalanced, or directional (Hemani et al., 2018). Gives an unbiased estimate even if all SNPs do not adhere to instrumental variable assumptions but requires the InSIDE (instrument strength independent of direct effects) assumption to be valid. Requires a large number of instrumental SNPs otherwise method is underpowered. |

| Wald ratio | This is the easiest method to estimate a causal effect. Wald ratio method is appropriate when only a single SNP is available to proxy the risk factor of interest. However, a limitation is that it is much harder to appraise MR assumptions with only a single SNP. (Wald, 1940). |

Description of statistical methods used in Mendelian randomization analysis.

The statistical methods described are the inverse variance weighted (IVW), maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), weighted median estimate (WME), mode-based estimate (MBE) and MR-Egger.

Limitations of MR Pertinent to Glioma

Mendelian randomization has widely recognized limitations (Glynn, 2010). For some exposures there is a lack of genetic variants (SNPs) available for instrumentation (Smith and Ebrahim, 2004). For example, ionizing radiation emitted by mobile phones has been suggested as a risk factor for glioma (Yang et al., 2017). However, currently no genetic variants have been associated with exposure (or response) to ionizing radiation and therefore MR analysis cannot be performed for this particular risk factor (Smith, 2010).

A key limitation of MR is pleiotropy (Sheehan et al., 2008). Pleiotropy occurs when a genetic variant has more than one effect. If one or more of these effects influence the outcome through pathways other than the exposure of interest (so called horizontal pleiotropy) a core MR assumption is violated, i.e., that variants only exert their effect on the outcome via their influence on the exposure of interest (Evans et al., 2013; Burgess, 2014; Bennett and Holmes, 2017; Yarmolinsky et al., 2017). Techniques have been developed, such as MR-Egger regression, that can quantify the amount of bias caused by horizontal pleiotropy, as well as providing a valid causal estimate despite the presence of horizontal pleiotropy (Bowden et al., 2015). Another type of pleiotropy that exists is vertical pleiotropy. This is where the genetic variants have associations with biomarkers that are downstream of the biomarker of interest (Bennett and Holmes, 2017). Thus, they are on the causal pathway and should be considered as intermediates of the relationship between an exposure and an outcome, not as confounding factors.

Mendelian randomization studies typically require large sample sizes, an issue that can be compounded by the rare nature of glioma. One way to increase power is to develop genetic risk scores that contain multiple alleles to explain more of the variance in the exposure of interest. This runs the risk of including invalid variants, such as those that do not exert their effect on the outcome via the exposure of interest (Evans et al., 2013; Burgess, 2014; Yarmolinsky et al., 2017), although such potential violations of the MR assumption can be formally tested using MR-Egger regression. Power can also be increased by using a two-sample approach, where large case-control GWAS can be used even if they have not measured the exposure of interest.

Limitations of MR have been discussed in detail in several published papers (Davey Smith and Ebrahim, 2003; Smith and Ebrahim, 2004; Lawlor et al., 2008; Sheehan et al., 2008; Bochud and Rousson, 2010; Davey Smith, 2011b; VanderWeele et al., 2014).

Mr in Glioma Research

Studies That Have Evaluated Risk Factors for Glioma Using MR

Two-sample MR is a method that can harness information from GWAS summary statistics and has been applied to the context of glioma to look at several risk factors. We discuss key studies that have used two-sample MR to investigate associations between previously reported risk factors and glioma (Table 3).

Table 3

| Author of the study | Number of glioma | Risk factor of interest | Main Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| cases and controls | |||

| Haycock et al., 2017 | 1,130 cases and 6,294 controls | Telomere Length | Risk of glioma increases per standard deviation (SD) increase in telomere (OR 5.27; 95% CI: 3.15–8.81. P = 0.01) |

| Walsh et al., 2015 | 1,130 cases and 6,294 controls | Telomere Length | Risk of glioma increases monotonically with each increasing septile of telomere length (O.R 1.12; 95% CI: 1.09–1.16. P = 3.83 × 10-12) |

| Takahashi et al., 2018 | 12,488 cases and 18,169 controls | Vitamin D levels | Little evidence of any association. (OR per SD increase in Vitamin D levels 1.21; 95% CI: 0.90–1.62. P = 0.201) |

| Disney-Hogg et al., 2018a | 12,488 cases and 18,169 controls | Atopy | For binary risk factors the results can be interpreted by risk of disease/odds ratio for glioma per 2.7-fold increase in odds of the risk factor (exposure). No strong evidence of any association between glioma and asthma and hay fever (OR 0.96; 95% CI: 0.90–1.03. P = 0.248), IgE levels (OR 0.88; 0.69–1.13. P = 0.319), or self-reported allergy (OR 1.03; 95% CI: 0.95–1.11. P = 0.534). For atopic dermatitis an inverse association was found by IVW (OR 0.96; 95% CI: 0.93–1.00. P = 0.041) and MLE (OR 0.96; 95% CI: 0.94–0.99. P = 0.003) |

| Disney-Hogg et al., 2018b | 12,488 cases and 18,169 controls | Obesity-related factors | No strong evidence of any association for all factors (P = > 0.05). |

Description of MR studies that have investigated the causal association between a factor and glioma risk.

An MR study to evaluate the causal relevance of telomere length on the risk of cancer and non-neoplastic diseases found that genetically predicted longer telomeres increased the risk of glioma, while being protective for certain non-neoplastic diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases (Zheng et al., 2017). The analysis employed summary genetic data for 35 cancers and 45 non-neoplastic diseases, including 1,130 glioma cases and 6,294 controls. The strongest association was for glioma (OR per SD increase in genetically predicted telomere length was 5.27; 95% CI: 3.15–8.81) (Zheng et al., 2017). A possible explanation for this observation is that telomere shortening may act as a tumor suppressor, restricting the proliferative potential of cells. Therefore, those with longer telomeres have a greater probability of obtaining somatic mutations due to an increased proliferative potential (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011).

Walsh et al. (2015) also used an MR approach to establish whether a genotypically estimated longer or shorter telomere length was linked with an increased risk of glioma and whether inheritance of SNPs associated with telomere length are indicators of glioma risk. The authors accessed differences in genotypically estimated relative telomere length in a total of 1,130 glioma patients and 6,294 controls. The average approximated telomere length was 31bp (5.7%) longer in glioma cases compared with controls in discovery analyses (P = 7.82 × 10-8). This finding was supported in the replication analysis as the mean telomere length was 27 bp (5.0%) longer in glioma cases than controls (1.48 × 10-3). The authors reported that the risk of glioma increases monotonically with each increasing septile of telomere length (O.R 1.12; 95% CI: 0.90–1.62). Additionally, the authors reported that four telomere length-associated SNPs were significantly related with glioma risk in pooled analyses, including those in the telomerase component genes TERC (O.R 1.14; 95% C.I. = 1.03–1.28) and TERT (O.R 1.39; 95% C.I. = 1.27–1.52), and those in the CST complex genes OBFC1 (O.R 1.18; 95% C.I. = 1.05–1.33) and CTC1 (O.R 1.14; 95% C.I. = 1.02–1.28). The indication of risk alleles for glioma close to TERC and TERT that are also related with telomere length suggests that telomerase is important in glioma formation (Walsh et al., 2014).

Takahashi et al. (2018) used two-sample MR to investigate whether a causal relationship exists between circulating vitamin D and glioma risk, involving 12,488 glioma cases and 18,169 controls. The authors reported no strong evidence of a causal relationship between vitamin D and glioma when either the inverse-variance weighted (IVW) method (OR per SD increase 1.21, 95% CI: 0.90–1.62, P = 0.201) or the maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) method (OR per SD increase 1.20, 95% CI: 0.98–1.48, P = 0.083) was used (Takahashi et al., 2018).

Disney-Hogg et al. (2018a) used an MR approach to evaluate the observed inverse relationship between allergies and glioma risk. The instrumental variables were SNPs robustly associated with atopic dermatitis, asthma and hay fever, IgE levels, and self-reported allergy. The study involved 12,488 cases and 18,169 controls. The authors found no significant association between glioma and asthma, hay fever, IgE levels, or self-reported allergy. For atopic dermatitis an inverse association was found (OR per 2.7-fold increase in odds of atopic dermatitis) by the IVW (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.93–1.00, P = 0.041) and MLE methods (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.94–0.99, P = 0.003), but not for weighted median estimate (WME) and mode-based estimate (MBE) methods (Disney-Hogg et al., 2018a), suggesting that having atopic dermatitis reduces the risk of glioma.

Disney-Hogg et al. (2018b) carried out an MR analysis to interrogate the observed association between obesity-related factors and risk of glioma. The authors identified variants that were robustly associated with 10 key obesity-related factors: 2-h post-challenge glucose, BMI, fasting glucose, fasting insulin, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, type-2 diabetes, total cholesterol, triglycerides and waist-hip ratio. This study encompassed 12,488 cases and 18,169 controls. This study found little evidence that indicated that obesity-related factors contribute to glioma (Disney-Hogg et al., 2018b).

Potential Application of Different MR Study Designs in Glioma Research

There are several different design strategies for MR that have been discussed in detail by Zheng et al. (2017). The potential application of these different MR study designs in glioma research are outlined below.

Improved knowledge of signaling pathways that are causally associated glioma incidence can be helpful to design preventative strategies and effective therapeutic targets (Wang et al., 2015). A useful MR strategy to establish whether a molecular intermediate plays a role in the causal pathway between a risk factor and disease is the use of two-step MR (Relton and Davey Smith, 2012). An improved understanding of the molecular changes that drive glioma formation will allow for opportunities to modify disease causing factors.

Bidirectional MR involves using instruments for both the exposure and the outcome to assess the direction of causality: i.e., does the exposure cause the outcome or does the outcome cause the exposure (Timpson et al., 2010). For instance, observational studies have suggested that there is an inverse association between allergies and glioma risk, but the direction and causality of the association remains uncertain: it is not clear whether allergies decrease the risk of glioma or whether the inverse association arises because of suppression of the immune system by glioma itself (Schoemaker et al., 2006).

There are cases in which genetic variants are related to numerous correlated phenotypes (Low, 2001), for example, genetic variants that associate with lipoprotein metabolism tend not to correlate with just one specific lipid fraction (Wurtz et al., 2013). As a result assessing the causal association of one specific intermediate phenotype with disease can be challenging (Davey Smith and Hemani, 2014). Multi-phenotype MR can be used in these cases (Davey Smith and Hemani, 2014; Burgess et al., 2015; Burgess and Thompson, 2015; Kemp et al., 2016). Multivariable MR can be applied to glioma research when testing the effect of lipids on glioma to identify the independent effect of each lipid subtypes on glioma.

Hypothesis-driven MR has huge potential in glioma research. Hypothesis-driven MR can validate the relationship between a risk factor and glioma for which a causal association has previously been reported.

In addition, hypothesis-free MR has the potential to identify novel causal associations. Hypothesis-free MR can be used to examine causality in complex frameworks in glioma, as a well as a method to data mine high-dimensional studies (Evans and Davey Smith, 2015). Haycock et al. (2017) implemented a mixture of hypothesis-driven and hypothesis-free MR to investigate the relationship between telomere length and 22 cancers and 32 primary non-neoplastic diseases.

Mendelian randomization-Base is a tool that improves the accessibility of GWAS summary data for MR research (Hemani et al., 2016). MR-Base can assist hypothesis-free testing as it allows researchers to examine all pairwise associations to data mine for causal relationships of interest (Davey Smith, 2011a). Where novel associations are identified, these associations can then be subjected to formal and extensive hypothesis-testing studies (Evans and Smith, 2015).

Factorial MR can be used to develop therapeutic strategies to improve glioma survival. Factorial RCT is where a participant is either assigned to a group that obtains neither intervention, one of the interventions, or both (Montgomery et al., 2003). In a factorial trial the separate effects of each intervention can be considered, as well as, the benefits of obtaining both interventions together (Montgomery et al., 2003). Similarly, factorial MR can be performed by using combinations of genetic variants to attain unconfounded estimates of the effect of co-occurrence of the two drug targets on disease (Davey Smith and Hemani, 2014). In glioma research if we have two drug targets and we want to know the combined effects of these two drugs on glioma, then we can apply factorial MR. Factorial MR can assess the antitumor efficacy of drug targets on glioma by investigating the combination of different targeted drugs (Reardon and Wen, 2006).

Future of MR in Glioma Research

For GWAS and MR of glioma progression to be successful for the development of drug targets to improve glioma survival, large scale case-only studies will be required with both progression and germline genetic data. RCTs offer a potential reservoir of data for such studies; however, due to the rare nature of glioma, sample size is limited (Vuorinen et al., 2003; Gehring et al., 2009; U.S.National Library of Medicine, 2018). A limitation of progression studies is the introduction of collider bias, discussed in detail in Paternoster et al. (2017). Collider bias is problematic in MR of disease progression as a risk factor of interest that causes the disease may be correlated with other risk factors involved in incidence, and any association between the index risk factor and progression can be confounded by these correlated risk factors. If the problems of sample size and collider bias can be adequately overcome, GWAS and MR of disease progression offer a promising opportunity to identify new treatments for glioma that could enhance survival (Davey Smith et al., 2017). Additionally, an improved understanding of the molecular changes that drive glioma progression will allow for opportunities to develop targeted molecular therapies. At present, although there are some examples where targeted therapy responses have been recorded in glioma patients, no targeted therapy has been approved as an effective treatment in clinical trials (Touat et al., 2017).

Future research will involve hypothesis free MR, which make use of omics data. There is a growing body of evidence showing that epigenetic biomarkers of glioma can be used for prediction and prognosis. Notably in neuro-oncology the O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase promoter methylation can act both a prognostic and predictive biomarker for glioblastoma (Esteller et al., 2000; Olson et al., 2011; Reifenberger et al., 2012; Wick et al., 2012). As genetic variants associated with DNA methylation seem to overlap with expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) at many loci throughout the genome (Bell et al., 2012; Shi et al., 2014), both DNA methylation and gene expression may exist on the causal pathway between genetic variation and disease. The ability to identify epigenetic and transcriptomic markers for glioma risk and progression could be important in understanding the underlying mechanisms of glioma. Using an MR approach, the causal chain between DNA methylation, gene expression and glioma onset/progression can be investigated (Relton and Davey Smith, 2012).

Given the lack of large-scale case-only studies with data on progression and germline genetic data, a priority of research in the near term should be to identify causes of glioma onset. The findings from such studies will be informative for the design of primary and secondary prevention strategies. The latter could be particularly valuable for glioma prevention in high risk populations, such as childhood cancer survivors (who received radiation therapy), people with genetic syndromes known to increase risk of glioma and people exposed to known causal factors because of their occupations. For example, if a specific dietary factor is found to be causally associated with a decrease in glioma risk, high risk populations could be advised to increase their consumption of that specific dietary factor.

Conclusion

Mendelian randomization offers a promising, novel way to identify risk factors and drug targets for glioma to both inform public health policy for prevention, as well as, allowing the development of therapeutic approaches to improve prognosis. The latter will require the development of large-scale case-only studies with data on progression and germline genetic data.

Statements

Author contributions

AH contributed to the manuscript research and writing. KK, PH, RM, CR, JZ, and AM reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Brain Tumour Bank and Research Fund and Southmead Hospital Charity. Charity registration number:1055900. RM, AM, and CR are supported by a Cancer Research United Kingdom programme grant, the Integrative Cancer Epidemiology Programme (Grant no. C18281/A19169). Dr. Haycock is supported by CRUK Population Research Postdoctoral Fellowship C52724/A20138.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1

Amirian E. S. Zhou R. Wrensch M. R. Olson S. H. Scheurer M. E. Il’yasova D. et al (2016). Approaching a scientific consensus on the association between allergies and Glioma risk: a report from the glioma international case-control study.Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev.25282–290. 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-15-0847

2

Andersen L. Friis S. Hallas J. Ravn P. Kristensen B. W. Gaist D. (2015). Hormonal contraceptive use and risk of glioma among younger women: a nationwide case-control study.Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol.79677–684. 10.1111/bcp.12535

3

Anttila A. Heikkila P. Nykyri E. Kauppinen T. Pukkala E. Hernberg S. et al (1996). Risk of nervous system cancer among workers exposed to lead.J. Occup. Environ. Med.38131–136. 10.1097/00043764-199602000-00010

4

Arrowsmith J. Miller P. (2013). Trial watch: phase II and phase III attrition rates 2011-2012.Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.12:569. 10.1038/nrd4090

5

Ashburn T. T. Thor K. B. (2004). Drug repositioning: identifying and developing new uses for existing drugs.Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.3673–683. 10.1038/nrd1468

6

Azad T. D. Pan J. Connolly I. D. Remington A. Wilson C. M. Grant G. A. (2015). Therapeutic strategies to improve drug delivery across the blood-brain barrier.Neurosurg. Focus38:E9. 10.3171/2014.12.Focus14758

7

Bell J. T. Tsai P. C. Yang T. P. Pidsley R. Nisbet J. Glass D. et al (2012). Epigenome-wide scans identify differentially methylated regions for age and age-related phenotypes in a healthy ageing population.PLoS Genet.8:e1002629. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002629

8

Bendsen N. T. Christensen R. Bartels E. M. Kok F. J. Sierksma A. Raben A. et al (2013). Is beer consumption related to measures of abdominal and general obesity? A systematic review and meta-analysis.Nutr. Rev.7167–87. 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2012.00548.x

9

Bennett D. A. Holmes M. V. (2017). Mendelian randomisation in cardiovascular research: an introduction for clinicians.Heart1031400–1407. 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-310605

10

Berg-Beckhoff G. Schuz J. Blettner M. Munster E. Schlaefer K. Wahrendorf J. et al (2009). History of allergic disease and epilepsy and risk of glioma and meningioma (INTERPHONE study group, Germany).Eur. J. Epidemiol.24433–440. 10.1007/s10654-009-9355-6

11

Bhatti P. Stewart P. A. Hutchinson A. Rothman N. Linet M. S. Inskip P. D. et al (2009). Lead exposure, polymorphisms in genes related to oxidative stress, and risk of adult brain tumors.Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers. Prev.181841–1848. 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-09-0197

12

Blumenthal D. T. Raizer J. J. Rosenblum M. K. Bilsky M. H. Hariharan S. Abrey L. E. (1999). Primary intracranial neoplasms in patients with HIV.Neurology521648–1651. 10.1212/WNL.52.8.1648

13

Bochud M. Rousson V. (2010). Usefulness of Mendelian randomization in observational∗ epidemiology.Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health7711–728. 10.3390/ijerph7030711

14

Boffetta P. Hashibe M. La Vecchia C. Zatonski W. Rehm J. (2006). The burden of cancer attributable to alcohol drinking.Int. J. Cancer119884–887. 10.1002/ijc.21903

15

Bondy M. L. Scheurer M. E. Malmer B. Barnholtz-Sloan J. S. Davis F. G. Il’yasova D. et al (2008). Brain tumor epidemiology: consensus from the brain tumor epidemiology consortium.Cancer113 7(Suppl.)1953–1968. 10.1002/cncr.23741

16

Bowden J. Davey Smith G. Burgess S. (2015). Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression.Int. J. Epidemiol.44512–525. 10.1093/ije/dyv080

17

Braganza M. Z. Kitahara C. M. Berrington de Gonzalez A. Inskip P. D. Johnson K. J. Rajaraman P. (2012). Ionizing radiation and the risk of brain and central nervous system tumors: a systematic review.Neuro Oncol.141316–1324. 10.1093/neuonc/nos208

18

Braganza M. Z. Rajaraman P. Park Y. Inskip P. D. Freedman N. D. Hollenbeck A. R. et al (2014). Cigarette smoking, alcohol intake, and risk of glioma in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study.Br. J. Cancer110242–248. 10.1038/bjc.2013.611

19

Brunner C. Davies N. M. Martin R. M. Eeles R. Easton D. Kote-Jarai Z. et al (2017). Alcohol consumption and prostate cancer incidence and progression: a mendelian randomisation study.Int. J. Cancer14075–85. 10.1002/ijc.30436

20

Burgess S. (2014). Sample size and power calculations in mendelian randomization with a single instrumental variable and a binary outcome.Int. J. Epidemiol.43922–929. 10.1093/ije/dyu005

21

Burgess S. Dudbridge F. Thompson S. G. (2015). Re: ”Multivariable Mendelian randomization: the use of pleiotropic genetic variants to estimate causal effects”.Am. J. Epidemiol.181290–291. 10.1093/aje/kwv017

22

Burgess S. Thompson S. G. (2015). Multivariable Mendelian randomization: the use of pleiotropic genetic variants to estimate causal effects.Am. J. Epidemiol.181251–260. 10.1093/aje/kwu283

23

Cancer Research United Kingdom (2015). Brain, Other CNS and Intracranial Tumours Incidence Statistics.Available: http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/brain-other-cns-and-intracranial-tumours/incidence#collapseTen [accessed April, 18 2018].

24

Cancer Research United Kingdom (2016). Survival for All Types of Brain Tumour.Available: http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/brain-other-cns-and-intracranial-tumours/incidence#collapseTen [accessed 09 2018].

25

Carozza S. E. Wrensch M. Miike R. Newman B. Olshan A. F. Savitz D. A. et al (2000). Occupation and adult Gliomas.Am. J. Epidemiol.152838–846. 10.1093/aje/152.9.838

26

Castle W. E. (1903). Mendel’s law of heredity.Science18396–406. 10.1126/science.18.456.396

27

Chen P. Aldape K. Wiencke J. K. Kelsey K. T. Miike R. Davis R. L. et al (2001). Ethnicity delineates different genetic pathways in malignant Glioma.Cancer Res.613949–3954.

28

Cocco P. Dosemeci M. Heineman E. F. (1998). Brain cancer and occupational exposure to lead.J. Occup. Environ. Med.40937–942. 10.1097/00043764-199811000-00001

29

Corsello S. M. Bittker J. A. Liu Z. Gould J. McCarren P. Hirschman J. E. et al (2017). The drug repurposing hub: a next-generation drug library and information resource.Nat. Med.23405–408. 10.1038/nm.4306

30

Darefsky A. S. Dubrow R. (2009). International variation in the incidence of adult primary malignant neoplasms of the brain and central nervous system.Cancer Causes Control201593–1604. 10.1007/s10552-009-9404-1

31

Das A. Tan W. L. Teo J. Smith D. R. (2002). Glioblastoma multiforme in an Asian population: evidence for a distinct genetic pathway.J. Neurooncol.60117–125. 10.1023/A:1020622415786

32

Daugherty S. E. Moore S. C. Pfeiffer R. M. Inskip P. D. Park Y. Hollenbeck A. et al (2011). Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and glioma in the NIH-AARP diet and health study cohort.Cancer Prev. Res.42027–2034. 10.1158/1940-6207.capr-11-0274

33

Davey Smith G. (2011a). Random allocation in observational data: how small but robust effects could facilitate hypothesis-free causal inference.Epidemiology22460–463; discussion 467–468. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31821d0426

34

Davey Smith G. (2011b). Use of genetic markers and gene-diet interactions for interrogating population-level causal influences of diet on health.Genes Nutr.627–43. 10.1007/s12263-010-0181-y

35

Davey Smith G. Ebrahim S. (2003). ‘Mendelian randomization’: can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease?Int. J. Epidemiol.321–22. 10.1093/ije/dyg070

36

Davey Smith G. Hemani G. (2014). Mendelian randomization: genetic anchors for causal inference in epidemiological studies.Hum. Mol. Genet.23R89–R98. 10.1093/hmg/ddu328

37

Davey Smith G. Paternoster L. Relton C. (2017). When will mendelian randomization become relevant for clinical practice and public health?JAMA317589–591. 10.1001/jama.2016.21189

38

Davis F. G. McCarthy B. Jukich P. (1999). The descriptive epidemiology of brain tumors.Neuroimaging Clin. N. Am.9581–594.

39

Didelez V. Sheehan N. (2007). Mendelian randomization as an instrumental variable approach to causal inference.Stat. Methods Med. Res.16309–330. 10.1177/0962280206077743

40

Disney-Hogg L. Cornish A. J. Sud A. Law P. J. Kinnersley B. Jacobs D. I. et al (2018a). Impact of atopy on risk of glioma: a Mendelian randomisation study.BMC Med.16:42. 10.1186/s12916-018-1027-5

41

Disney-Hogg L. Sud A. Law P. J. Cornish A. J. Kinnersley B. Ostrom Q. T. et al (2018b). Influence of obesity-related risk factors in the aetiology of Glioma.Br. J. Cancer1181020–1027. 10.1038/s41416-018-0009-x

42

Dubrow R. Darefsky A. S. (2011). Demographic variation in incidence of adult glioma by subtype, United States, 1992-2007.BMC Cancer11:325. 10.1186/1471-2407-11-325

43

Esteller M. Garcia-Foncillas J. Andion E. Goodman S. N. Hidalgo O. F. Vanaclocha V. et al (2000). Inactivation of the DNA-repair gene MGMT and the clinical response of gliomas to alkylating agents.N. Engl. J. Med.3431350–1354. 10.1056/nejm200011093431901

44

Evans D. M. Brion M. J. Paternoster L. Kemp J. P. McMahon G. Munafo M. et al (2013). Mining the human phenome using allelic scores that index biological intermediates.PLoS Genet.9:e1003919. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003919

45

Evans D. M. Davey Smith G. (2015). Mendelian randomization: new applications in the coming age of hypothesis-free causality.Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet.16327–350. 10.1146/annurev-genom-090314-050016

46

Evans D. M. Smith G. D. (2015). Mendelian randomization: new applications in the coming age of hypothesis-free causality.Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet.16327–350. 10.1146/annurev-genom-090314-050016

47

Ference B. A. Ginsberg H. N. Graham I. Ray K. K. Packard C. J. Bruckert E. et al (2017). Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1. Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. A consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel.Eur. Heart J.382459–2472. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx144

48

Flegal K. M. Graubard B. I. Williamson D. F. Cooper R. S. (2011). Reverse causation and illness-related weight loss in observational studies of body weight and mortality.Am. J. Epidemiol.1731–9. 10.1093/aje/kwq341

49

Frei P. Poulsen A. H. Johansen C. Olsen J. H. Steding-Jessen M. Schüz J. (2011). Use of mobile phones and risk of brain tumours: update of Danish cohort study.BMJ343:3. 10.1136/bmj.d6387

50

Gaist D. García-Rodríguez L. A. Sørensen H. T. Hallas J. Friis S. (2013). Use of low-dose aspirin and non-aspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of Glioma: a case–control study.Br. J. Cancer1081189–1194. 10.1038/bjc.2013.87

51

Gehring K. Sitskoorn M. M. Gundy C. M. Sikkes S. A. Klein M. Postma T. J. et al (2009). Cognitive rehabilitation in patients with gliomas: a randomized, controlled trial.J. Clin. Oncol.273712–3722. 10.1200/jco.2008.20.5765

52

Giles G. G. McNeil J. J. Donnan G. Webley C. Staples M. P. Ireland P. D. et al (1994). Dietary factors and the risk of glioma in adults: results of a case-control study in Melbourne. Australia.Int. J. Cancer59357–362. 10.1002/ijc.2910590311

53

Glynn R. J. (2010). Promises and limitations of mendelian randomization for evaluation of biomarkers.Clin. Chem.56388–390. 10.1373/clinchem.2009.142513

54

Greenland S. (2000). An introduction to instrumental variables for epidemiologists.Int. J. Epidemiol.29722–729. 10.1093/ije/29.4.722

55

Hall J. R. Short S. C. (2009). Management of glioblastoma multiforme in HIV patients: a case series and review of published studies.Clin. Oncol.21591–597. 10.1016/j.clon.2009.04.006

56

Hammer G. P. du Prel J. B. Blettner M. (2009). Avoiding bias in observational studies: part 8 in a series of articles on evaluation of scientific publications.Dtsch Arztebl. Int.106664–668. 10.3238/arztebl.2009.0664

57

Hanahan D. Weinberg R. A. (2011). Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation.Cell144646–674. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013

58

Hart C. L. Davey Smith G. Gruer L. Watt G. C. (2010). The combined effect of smoking tobacco and drinking alcohol on cause-specific mortality: a 30 year cohort study.BMC Public Health10:789. 10.1186/1471-2458-10-789

59

Hartwig F. P. Davies N. M. Hemani G. Davey Smith G. (2016). Two-sample Mendelian randomization: avoiding the downsides of a powerful, widely applicable but potentially fallible technique.Int. J. Epidemiol.451717–1726. 10.1093/ije/dyx028

60

Haycock P. C. Burgess S. Nounu A. Zheng J. Okoli G. N. Bowden J. et al (2017). Association between telomere length and risk of cancer and non-neoplastic diseases: a mendelian randomization study.JAMA Oncol.3636–651. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5945

61

Haycock P. C. Burgess S. Wade K. H. Bowden J. Relton C. Davey Smith G. (2016). Best (but oft-forgotten) practices: the design, analysis, and interpretation of Mendelian randomization studies.Am. J. Clin. Nutr.103965–978. 10.3945/ajcn.115.118216

62

Hemani G. Zheng J. Elsworth B. Wade K. H. Haberland V. Baird D. et al (2018). The MR-Base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome.eLife7:e34408. 10.7554/eLife.34408

63

Hemani G. Zheng J. Wade K. H. Laurin C. Elsworth B. Burgess S. et al (2016). MR-Base: a platform for systematic causal inference across the phenome using billions of genetic associations.bioRxiv[Preprint]. 10.1101/078972

64

Holick C. N. Smith S. G. Giovannucci E. Michaud D. S. (2010). Coffee, tea, caffeine intake, and risk of adult glioma in three prospective cohort studies.Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev.1939–47. 10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-09-0732

65

Houben M. P. Louwman W. J. Tijssen C. C. Teepen J. L. van Duijn C. M. Coebergh J. W. (2004). Hypertension as a risk factor for glioma? Evidence from a population-based study of comorbidity in glioma patients.Ann. Oncol.151256–1260. 10.1093/annonc/mdh306

66

Inoue A. Solon G. (2010). Two-sample instrumental variables estimators.Rev. Econ. Stat.92557–561. 10.1162/REST_a_00011

67

Iturrieta-Zuazo I. Walter S. (2015). Mendelian randomization: present and future of epidemiological studies in cardiology.Revista Española Cardiología6887–91. 10.1016/j.recesp.2014.06.026

68

Jukich P. J. McCarthy B. J. Surawicz T. S. Freels S. Davis F. G. (2001). Trends in incidence of primary brain tumors in the United States, 1985-1994.Neuro Oncol.3141–151. 10.1093/neuonc/3.3.141

69

Kabat G. C. Park Y. Hollenbeck A. R. Schatzkin A. Rohan T. E. (2011). Reproductive factors and exogenous hormone use and risk of adult glioma in women in the NIH-AARP diet and health study.Int. J. Cancer128944–950. 10.1002/ijc.25413

70

Kaplan S. Novikov I. Modan B. (1997). Nutritional factors in the etiology of brain tumors: potential role of nitrosamines, fat, and cholesterol.Am. J. Epidemiol.146832–841. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009201

71

Kelly P. J. (2010). Gliomas: survival, origin and early detection.Surg. Neurol. Int.1:96. 10.4103/2152-7806.74243

72

Kemp J. P. Sayers A. Smith G. D. Tobias J. H. Evans D. M. (2016). Using Mendelian randomization to investigate a possible causal relationship between adiposity and increased bone mineral density at different skeletal sites in children.Int. J. Epidemiol.451560–1572. 10.1093/ije/dyw079

73

Khuder S. A. Mutgi A. B. Schaub E. A. (1998). Meta-analyses of brain cancer and farming.Am. J. Ind. Med.34252–260. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0274(199809)34:3<252::AID-AJIM7>3.0.CO;2-X

74

Kim Y. I. (2003). Role of folate in colon cancer development and progression.J. Nutr.133(11 Suppl. 1)3731s–3739s. 10.1093/jn/133.11.3731S

75

Kinnersley B. Houlston R. S. Bondy M. L. (2018). Genome-wide association studies in Glioma.Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev.27418–428. 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-17-1080

76

Kitahara C. M. Linet M. S. Brenner A. V. Wang S. S. Melin B. S. Wang Z. et al (2014). Personal history of diabetes, genetic susceptibility to diabetes, and risk of brain glioma: a pooled analysis of observational studies.Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers. Prev.2347–54. 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-13-0913

77

Krishnan G. Felini M. Carozza S. E. Miike R. Chew T. Wrensch M. (2003). Occupation and adult Gliomas in the San Francisco Bay Area.J. Occup. Environ. Med.45639–647. 10.1097/01.jom.0000069245.06498.48

78

Kuratsu J. Takeshima H. Ushio Y. (2001). Trends in the incidence of primary intracranial tumors in Kumamoto, Japan.Int. J. Clin. Oncol.6183–191. 10.1007/pl00023928

79

Kyritsis A. P. Bondy M. L. Levin V. A. (2011). Modulation of glioma risk and progression by dietary nutrients and antiinflammatory agents.Nutr. Cancer63174–184. 10.1080/01635581.2011.523807

80

Lam T. V. Agovino P. Niu X. Roche L. (2007). Linkage study of cancer risk among lead-exposed workers in New Jersey.Sci. Total Environ.372455–462. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2006.10.018

81

Larsson S. C. Traylor M. Malik R. Dichgans M. Burgess S. Markus H. S. (2017). Modifiable pathways in Alzheimer’s disease: mendelian randomisation analysis.BMJ359:j5375. 10.1136/bmj.j5375

82

Lawlor D. A. Davey Smith G. Bruckdorfer K. R. Kundu D. Ebrahim S. (2004). Observational versus randomised trial evidence.Lancet364755–756. 10.1016/s0140-6736(04)16926-2

83

Lawlor D. A. Harbord R. M. Sterne J. A. Timpson N. Davey Smith G. (2008). Mendelian randomization: using genes as instruments for making causal inferences in epidemiology.Stat. Med.271133–1163. 10.1002/sim.3034

84

Lee S. T. Bracci P. Zhou M. Rice T. Wiencke J. Wrensch M. et al (2014). Interaction of allergy history and antibodies to specific varicella-zoster virus proteins on glioma risk.Int. J. Cancer1342199–2210. 10.1002/ijc.28535

85

Li H. X. Meng H. Y. Peng X. X. Zong Q. Zhang K. Han G. L. (2015). A meta-analysis of association between pesticides exposure and glioma risk in adults.J. Craniofac. Surg.26e672–e673. 10.1097/scs.0000000000001707

86

Liao L. M. Friesen M. C. Xiang Y. B. Cai H. Koh D. H. Ji B. T. et al (2016). Occupational lead exposure and associations with selected cancers: the shanghai men’s and women’s health study cohorts.Environ. Health Perspect.12497–103. 10.1289/ehp.1408171

87

Linos E. Raine T. Alonso A. Michaud D. (2007). Atopy and risk of brain tumors: a meta-analysis.J. Natl. Cancer Inst.991544–1550. 10.1093/jnci/djm170

88

Little R. B. Madden M. H. Thompson R. C. Olson J. J. Larocca R. V. Pan E. et al (2013). Anthropometric factors in relation to risk of glioma.Cancer Causes Control241025–1031. 10.1007/s10552-013-0178-0

89

Louis D. N. Perry A. Reifenberger G. von Deimling A. Figarella-Branger D. Cavenee W. K. et al (2016). The 2016 world health organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary.Acta Neuropathol.131803–820. 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1

90

Low K. B. (2001). “Pleiotropy A2 - brenner, sydney,” inEncyclopedia of Geneticsed.MillerJ. H. (New York, NY: Academic Press) 1490–1491.

91

Malerba S. Galeone C. Pelucchi C. Turati F. Hashibe M. La Vecchia C. et al (2013). A meta-analysis of coffee and tea consumption and the risk of glioma in adults.Cancer Causes Control24267–276. 10.1007/s10552-012-0126-4

92

McLendon R. E. Robinson J. S. Jr. Chambers D. B. Grufferman S. Burger P. C. (1985). The glioblastoma multiforme in georgia, 1977-1981.Cancer56894–897. 10.1002/1097-0142(19850815)56:4<894::AID-CNCR2820560432>3.0.CO;2-#

93

Melin B. S. Barnholtz-Sloan J. S. Wrensch M. R. Johansen C. Il’yasova D. Kinnersley B. et al (2017). Genome-wide association study of glioma subtypes identifies specific differences in genetic susceptibility to glioblastoma and non-glioblastoma tumors.Nat. Genet.49789–794. 10.1038/ng.3823

94

Meyer R. M. (2010). Generalizing the results of cancer clinical trials.J. Clin. Oncol.28187–189. 10.1200/jco.2009.25.8608

95

Michaud D. S. Holick C. N. Batchelor T. T. Giovannucci E. Hunter D. J. (2009). Prospective study of meat intake and dietary nitrates, nitrites, and nitrosamines and risk of adult glioma.Am. J. Clin. Nutr.90570–577. 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27199

96

Mochizuki S. Iwadate Y. Namba H. Yoshida Y. Yamaura A. Sakiyama S. et al (1999). Homozygous deletion of the p16/MTS-1/CDKN2 gene in malignant gliomas is infrequent among Japanese patients.Int. J. Oncol.15983–989. 10.3892/ijo.15.5.983

97

Mokry L. E. Ahmad O. Forgetta V. Thanassoulis G. Richards J. B. (2015). Mendelian randomisation applied to drug development in cardiovascular disease: a review.J. Med. Genet.5271–79. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2014-102438

98

Montgomery A. A. Peters T. J. Little P. (2003). Design, analysis and presentation of factorial randomised controlled trials.BMC Med. Res. Methodol.3:26. 10.1186/1471-2288-3-26

99

Navas-Acien A. Pollan M. Gustavsson P. Plato N. (2002). Occupation, exposure to chemicals and risk of gliomas and meningiomas in Sweden.Am. J. Ind. Med.42214–227. 10.1002/ajim.10107

100

Neglia J. P. Robison L. L. Stovall M. Liu Y. Packer R. J. Hammond S. et al (2006). New primary neoplasms of the central nervous system in survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study.J. Natl. Cancer Ins.981528–1537. 10.1093/jnci/djj411

101

Nelson M. R. Tipney H. Painter J. L. Shen J. Nicoletti P. Shen Y. et al (2015). The support of human genetic evidence for approved drug indications.Nat. Genet.47856–860. 10.1038/ng.3314

102

Olson R. A. Brastianos P. K. Palma D. A. (2011). Prognostic and predictive value of epigenetic silencing of MGMT in patients with high grade gliomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis.J. Neurooncol.105325–335. 10.1007/s11060-011-0594-5

103

Ostrom Q. T. Bauchet L. Davis F. G. Deltour I. Fisher J. L. Langer C. E. et al (2014). The epidemiology of glioma in adults: a ”state of the science” review.Neuro Oncol.16896–913. 10.1093/neuonc/nou087

104

Ostrom Q. T. Gittleman H. Farah P. Ondracek A. Chen Y. Wolinsky Y. et al (2013). CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2006-2010.Neuro Oncol.15(Suppl. 2)ii1–ii56. 10.1093/neuonc/not151

105

Parent M. E. Turner M. C. Lavoue J. Richard H. Figuerola J. Kincl L. et al (2017). Lifetime occupational exposure to metals and welding fumes, and risk of glioma: a 7-country population-based case-control study.Environ. Health16:90. 10.1186/s12940-017-0300-y

106

Paternoster L. Tilling K. Davey Smith G. (2017). Genetic epidemiology and Mendelian randomization for informing disease therapeutics: conceptual and methodological challenges.PLoS Genet.13:e1006944. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006944

107

Preston-Martin S. Mack W. (1991). Gliomas and meningiomas in men in Los Angeles county: investigation of exposures to N-nitroso compounds.IARC Sci. Publ.105197–203.

108

Pukkala E. Martinsen J. I. Lynge E. Gunnarsdottir H. K. Sparén P. Tryggvadottir L. et al (2009). Occupation and cancer – follow-up of 15 million people in five Nordic countries.Acta Oncol.48646–790. 10.1080/02841860902913546

109

Qi L. (2009). Mendelian randomization in nutritional epidemiology.Nutr. Rev.67439–450. 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00218.x

110

Qi Z. Y. Shao C. Yang C. Wang Z. Hui G. Z. (2014). Alcohol consumption and risk of glioma: a meta-analysis of 19 observational studies.Nutrients6504–516. 10.3390/nu6020504

111

Quach P. El Sherif R. Gomes J. Krewksi D. (2017). A systematic review of the risk factors associated with the onset and progression of primary brain tumours.Neurotoxicology61214–232. 10.1016/j.neuro.2016.05.009

112

Rajaraman P. Stewart P. A. Samet J. M. Schwartz B. S. Linet M. S. Zahm S. H. et al (2006). Lead, genetic susceptibility, and risk of adult brain tumors.Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev.152514–2520. 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-06-0482

113

Reardon D. A. Wen P. Y. (2006). Therapeutic advances in the treatment of glioblastoma: rationale and potential role of targeted agents.Oncologist11152–164. 10.1634/theoncologist.11-2-152

114

Reifenberger G. Hentschel B. Felsberg J. Schackert G. Simon M. Schnell O. et al (2012). Predictive impact of MGMT promoter methylation in glioblastoma of the elderly.Int. J. Cancer1311342–1350. 10.1002/ijc.27385

115

Relton C. L. Davey Smith G. (2012). Two-step epigenetic Mendelian randomization: a strategy for establishing the causal role of epigenetic processes in pathways to disease.Int. J. Epidemiol.41161–176. 10.1093/ije/dyr233

116

Rice T. Lachance D. H. Molinaro A. M. Eckel-Passow J. E. Walsh K. M. Barnholtz-Sloan J. et al (2016). Understanding inherited genetic risk of adult glioma – a review.Neuro Oncol. Pract.310–16. 10.1093/nop/npv026

117

Robertson J. T. Gunter B. C. Somes G. W. (2002). Racial differences in the incidence of gliomas: a retrospective study from Memphis, Tennessee.Br. J. Neurosurg.16562–566. 10.1080/02688690209168361

118

Sadetzki S. Chetrit A. Freedman L. Stovall M. Modan B. Novikov I. (2005). Long-term follow-up for brain tumor development after childhood exposure to ionizing radiation for tinea capitis.Radiat. Res.163424–432. 10.1667/RR3329

119

Safaeian M. Rajaraman P. Hartge P. Yeager M. Linet M. Butler M. A. et al (2013). Joint effects between five identified risk variants, allergy, and autoimmune conditions on glioma risk.Cancer Causes Control241885–1891. 10.1007/s10552-013-0244-7

120

Samkange-Zeeb F. Schlehofer B. Schuz J. Schlaefer K. Berg-Beckhoff G. Wahrendorf J. et al (2010). Occupation and risk of glioma, meningioma and acoustic neuroma: results from a German case-control study (interphone study group, Germany).Cancer Epidemiol.3455–61. 10.1016/j.canep.2009.12.003

121

Sayon-Orea C. Martinez-Gonzalez M. A. Bes-Rastrollo M. (2011). Alcohol consumption and body weight: a systematic review.Nutr. Rev.69419–431. 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00403.x

122

Scheurer M. E. Amirian E. S. Davlin S. L. Rice T. Wrensch M. Bondy M. L. (2011). Effects of antihistamine and anti-inflammatory medication use on risk of specific glioma histologies.Int. J. Cancer1292290–2296. 10.1002/ijc.25883

123

Schoemaker M. J. Swerdlow A. J. Hepworth S. J. McKinney P. A. van Tongeren M. Muir K. R. (2006). History of allergies and risk of glioma in adults.Int. J. Cancer1192165–2172. 10.1002/ijc.22091

124

Schüz J. Jacobsen R. Olsen J. H. Boice J. J. D. McLaughlin J. K. Johansen C. (2006). Cellular telephone use and cancer risk: update of a nationwide danish cohort.J. Natl. Cancer Inst.981707–1713. 10.1093/jnci/djj464

125

Schwartzbaum J. Ahlbom A. Malmer B. Lonn S. Brookes A. J. Doss H. et al (2005). Polymorphisms associated with asthma are inversely related to glioblastoma multiforme.Cancer Res.656459–6465. 10.1158/0008-5472.can-04-3728

126

Schwartzbaum J. Edlinger M. Zigmont V. Stattin P. Rempala G. A. Nagel G. et al (2017). Associations between prediagnostic blood glucose levels, diabetes, and glioma.Sci. Rep.7:1436. 10.1038/s41598-017-01553-2

127

Seliger C. Meier C. R. Becker C. Jick S. S. Bogdahn U. Hau P. et al (2016a). Statin use and risk of glioma: population-based case-control analysis.Eur. J. Epidemiol.31947–952. 10.1007/s10654-016-0145-7

128

Seliger C. Ricci C. Meier C. R. Bodmer M. Jick S. S. Bogdahn U. et al (2016b). Diabetes, use of antidiabetic drugs, and the risk of glioma.Neuro Oncol.18340–349. 10.1093/neuonc/nov100

129

Sergentanis T. N. Tsivgoulis G. Perlepe C. Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I. Tzanninis I. G. Sergentanis I. N. et al (2015). Obesity and risk for brain/CNS tumors, gliomas and meningiomas: a meta-analysis.PLoS One10:e0136974. 10.1371/journal.pone.0136974

130

Shao C. Zhao W. Qi Z. He J. (2016). Smoking and glioma risk: evidence from a meta-analysis of 25 observational studies.Medicine95:e2447. 10.1097/md.0000000000002447

131

Sheehan N. A. Didelez V. Burton P. R. Tobin M. D. (2008). Mendelian randomisation and causal inference in observational epidemiology.PLoS Med.5:e177. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050177

132

Shi J. Marconett C. N. Duan J. Hyland P. L. Li P. Wang Z. et al (2014). Characterizing the genetic basis of methylome diversity in histologically normal human lung tissue.Nat. Commun.5:3365. 10.1038/ncomms4365

133

Smith G. D. (2010). Mendelian randomization for strengthening causal inference in observational studies:application to gene × environment interactions.Perspect. Psychol. Sci.5527–545. 10.1177/1745691610383505

134

Smith G. D. Ebrahim S. (2004). Mendelian randomization: prospects, potentials, and limitations.Int. J. Epidemiol.3330–42. 10.1093/ije/dyh132

135

Sofat R. Hingorani A. D. Smeeth L. Humphries S. E. Talmud P. J. Cooper J. et al (2010). Separating the mechanism-based and off-target actions of cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibitors with CETP gene polymorphisms.Circulation12152–62. 10.1161/circulationaha.109.865444

136

Stupp R. Hegi M. E. Mason W. P. van den Bent M. J. Taphoorn M. J. Janzer R. C. et al (2009). Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial.Lancet Oncol.10459–466. 10.1016/s1470-2045(09)70025-7

137

Sun B. B. Maranville J. C. Peters J. E. Stacey D. Staley J. R. Blackshaw J. et al (2018). Genomic atlas of the human plasma proteome.Nature55873–79. 10.1038/s41586-018-0175-2

138

Sunderman F. W. Jr. (2001). Nasal toxicity, carcinogenicity, and olfactory uptake of metals.Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci.313–24.

139

Takahashi H. Cornish A. J. Sud A. Law P. J. Kinnersley B. Ostrom Q. T. et al (2018). Mendelian randomisation study of the relationship between vitamin D and risk of glioma.Sci. Rep.8:2339. 10.1038/s41598-018-20844-w

140

Tamimi A. F. Juweid M. (2017). “Epidemiology and outcome of glioblastoma,” inGlioblastomaed.De VleeschouwerS. (Brisbane, QLD: Codon Publications Copyright).

141

Taylor A. J. Little M. P. Winter D. L. Sugden E. Ellison D. W. Stiller C. A. et al (2010). Population-based risks of CNS tumors in survivors of childhood cancer: the British childhood cancer survivor study.J. Clin. Oncol.285287–5293. 10.1200/jco.2009.27.0090

142

Testino G. (2011). The burden of cancer attributable to alcohol consumption.Maedica6313–320.

143

Timpson N. J. Nordestgaard B. G. Harbord R. M. Zacho J. Frayling T. M. Tybjærg-Hansen A. et al (2010). C-reactive protein levels and body mass index: elucidating direction of causation through reciprocal Mendelian randomization.Int. J. Obes.35300. 10.1038/ijo.2010.137

144

Touat M. Idbaih A. Sanson M. Ligon K. L. (2017). Glioblastoma targeted therapy: updated approaches from recent biological insights.Ann. Oncol.281457–1472. 10.1093/annonc/mdx106

145

U.S.National Library of Medicine (2018). Intraoperative Ultrasound Guided Glioma Surgery; a Randomised, Controlled Trial.Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03531333?id=NCT03531333&rank=1&load=cart

146

Urbanska K. Sokolowska J. Szmidt M. Sysa P. (2014). Glioblastoma multiforme - an overview.Contemp. Oncol.18307–312. 10.5114/wo.2014.40559

147

van Wijngaarden E. Dosemeci M. (2006). Brain cancer mortality and potential occupational exposure to lead: findings from the national longitudinal mortality study, 1979-1989.Int. J. Cancer1191136–1144. 10.1002/ijc.21947

148

VanderWeele T. J. Tchetgen Tchetgen E. J. Cornelis M. Kraft P. (2014). Methodological challenges in mendelian randomization.Epidemiology25427–435. 10.1097/ede.0000000000000081

149

Visser O. Ardanaz E. Botta L. Sant M. Tavilla A. Minicozzi P. et al (2015). Survival of adults with primary malignant brain tumours in Europe; results of the EUROCARE-5 study.Eur. J. Cancer512231–2241. 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.07.032

150

Vuorinen V. Hinkka S. Farkkila M. Jaaskelainen J. (2003). Debulking or biopsy of malignant glioma in elderly people - a randomised study.Acta Neurochir.1455–10. 10.1007/s00701-002-1030-6

151

Wald A. (1940). The fitting of straight lines if both variables are subject to error.Ann. Math. Stat.11284–300. 10.1214/aoms/1177731868

152

Walsh K. M. Codd V. Rice T. Nelson C. P. Smirnov I. V. McCoy L. S. et al (2015). Longer genotypically-estimated leukocyte telomere length is associated with increased adult glioma risk.Oncotarget642468–42477. 10.18632/oncotarget.6468

153

Walsh K. M. Codd V. Smirnov I. V. Rice T. Decker P. A. Hansen H. M. et al (2014). Variants near TERT and TERC influencing telomere length are associated with high-grade glioma risk.Nat. Genet.46731–735. 10.1038/ng.3004

154

Wang B. Du Y. (2013). Cadmium and its neurotoxic effects.Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev.2013:898034. 10.1155/2013/898034

155

Wang G. Xu S. Cao C. Dong J. Chu Y. He G. et al (2016). Evidence from a large-scale meta-analysis indicates eczema reduces the incidence of glioma.Oncotarget762598–62606. 10.18632/oncotarget.11545

156

Wang H. Xu T. Jiang Y. Xu H. Yan Y. Fu D. et al (2015). The challenges and the promise of molecular targeted therapy in malignant gliomas.Neoplasia17239–255. 10.1016/j.neo.2015.02.002

157

Wen P. Y. Kesari S. (2008). Malignant gliomas in adults.N. Engl. J. Med.359492–507. 10.1056/NEJMra0708126

158

Wick W. Platten M. Meisner C. Felsberg J. Tabatabai G. Simon M. et al (2012). Temozolomide chemotherapy alone versus radiotherapy alone for malignant astrocytoma in the elderly: the NOA-08 randomised, phase 3 trial.Lancet Oncol.13707–715. 10.1016/s1470-2045(12)70164-x

159

Wiedmann M. K. H. Brunborg C. Di Ieva A. Lindemann K. Johannesen T. B. Vatten L. et al (2017). The impact of body mass index and height on the risk for glioblastoma and other glioma subgroups: a large prospective cohort study.Neuro Oncol.19976–985. 10.1093/neuonc/now272

160

Wigertz A. Lonn S. Schwartzbaum J. Hall P. Auvinen A. Christensen H. C. et al (2007). Allergic conditions and brain tumor risk.Am. J. Epidemiol.166941–950. 10.1093/aje/kwm203

161