- 1Swiss National Center of Competence in Research (NCCR) “LIVES—Overcoming Vulnerability: Life Course Perspectives”, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland

- 2Institute of Sociological Research, Geneva School of Social Sciences, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland

- 3Geneva University Hospital and University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland

It is known that opportunities to cross borders legally, acquired through regularization programs, are acknowledged by previously illegalized migrants as one of the main positive effects of obtaining a residence permit. However, the impact of these policies has rarely been investigated through the “mobility lens.” To fulfill this gap, this study aims, through a case study, (1) to assess how obtaining a residence permit after having endured years of illegalization affects migrants' cross-border mobility and (2) to identify the direct and indirect transformative effects triggered by these changes in cross-border mobility. Our analysis considers regularization policies as a transformation of mobility regimes in which individual mobility trajectories are embedded. Thirty-nine migrants transitioning out of illegalization through an extraordinary regularization program implemented between 2017 and 2018 in the Canton of Geneva, Switzerland, were interviewed twice at a time interval of more than 1.5 years. Changes in actual mobility and perceived potential mobility (“motility”) were identified in the narratives. Inductive thematic analysis was used to identify related transformative effects. As a complement, descriptive statistics using two-wave panel data collected among a broader sample of migrants in the same context provided measures of cross-border mobility. Our findings highlight the importance of considering changes related to cross-border mobility when studying the impact of regularization programs on migrants' wellbeing, as they are a crucial ingredient of deeper adjustments occurring in their lives. We emphasize the importance of considering not only the subjective and objective effects triggered by increased actual mobility but also the subjective effects triggered by perceived increased potential mobility. Indeed, becoming aware of the new opportunities to cross borders leads to transforming imagined futures, subjectivities, identities, concerns, and perceived sources of stress, and it affects emotional wellbeing. The findings underline the relevance of a processual approach for two reasons: first, having experienced a long-lasting illegalization and forced immobility continues to affect individuals' experience of cross-border (im)mobility even after regularization; second, the triggered transformative effects take time to develop and observations at different times provide a richer picture.

Introduction

Individual (im)mobility trajectories are embedded into mobility regimes. Mobility regimes are the set of measures and policies implemented to control human mobility. Visa and migration policies, as well as infrastructure and repressive practices are part of these regimes. Indeed, nation states determine the conditions necessary to cross borders legally and to settle in a territory, the sanctions for people not respecting these rules as well as the intensity of controls (Neumayer, 2006; Hobolth, 2014; Schwarz, 2016). The different legal statuses in the country of residence, which differentiate illegalized migrants, asylum seekers, temporary residents, and citizens, affect the right to settle and work legally and the “power” of the accessible travel documents (Moret, 2018b).

Scholars have highlighted that illegalized migrants often experience forced mobility and/or1 forced immobility. Forced mobility is encountered when, despite the need and the desire to settle down in a safe place, the absence of legal status makes migrants unable to stay anywhere for a prolonged time without exposing themselves to high risks or extreme precarity. This is the case during undocumented migration, for migrants fleeing their country of origin because of war or repression and looking for asylum in a country with restrictive asylum policies, for rejected asylum seekers at risk of imprisonment or deportation, and for groups of migrants facing discrimination because of racial profiling. While they develop strategies to circulate across borders, they might experience prolonged migration journeys characterized by short stays, frequent mobility, and prolonged living in liminal conditions (Schuster, 2005; Schwarz, 2016; Scheel, 2018; Wyss, 2019). Forced immobility is encountered when after entering legally or illegally on a territory, migrants manage to establish for a prolonged period of time despite not being authorized to do so. However, against their the desire to visit the family in the country of origin and to travel like regular migrants do, they have to avoid crossing borders to prevent identity controls that might result in being refused re-entry in the territory where they live and work. This immobility results in long-lasting separations from family and friends as well as in difficulties in social and romantic life, as reported in research on illegalized migrants (Fresnoza-Flot, 2009; Sigona, 2012; Pila, 2016; Bravo, 2017; Dito et al., 2017; Consoli et al., 2022).

In order to reduce undeclared work and to better manage migratory flows, some European countries have implemented selective regularization programs over the last decades. These programs allow certain groups of illegalized residents living and working on the territory for many years—thus, mainly those experiencing forced immobility—to obtain a temporary residence permit (Chauvin et al., 2013). Many studies have examined these regularization programs' economic, social, and health impacts (Finotelli and Arango, 2011; Salmasi and Pieroni, 2015; Bansak, 2016; Kossoudji, 2016; Larramona and Sanso-Navarro, 2016; Fakhoury et al., 2021). Obtaining a legal status from a Schengen country opens the door to legal intra-European mobility and legal mobility between the residence country and the country of origin. Despite qualitative studies showing that the removal of legal barriers to cross-border mobility is perceived by previously illegalized migrants as one of the most significant changes brought by a residence permit (Le Courant, 2014; Kraler, 2019; Consoli et al., 2022), the impact of these programs has rarely been analyzed through the “mobility lens” (Urry, 2007).

At the same time, mobility research provides relevant concepts and theories to study how (im)mobility affects people's lives. For instance, Urry (2007) distinguished several forms of mobility, including corporeal mobility, imaginative mobility, virtual mobility, communicative mobility, and physical movement of objects. Other mobility researchers have argued that it is necessary to observe not only actual movements or lack of movements but also “potential mobility” (also called “mobility capital” or “motility”) and how and why this potential mobility is, or is not, transformed into actual physical movements (Kaufmann et al., 2004; De Vos et al., 2013; Cuignet et al., 2020). Moreover, this literature clarifies that (im)mobility has to be considered together with its effects and consequences in various life domains since it is a constitutive element of human existence. Travel studies have underlined that (im)mobility might affect, positively or negatively, individual wellbeing in different ways: through the feelings experienced during travels, the participation in activities enabled by traveling (activities that require moving between places or to be in contact with persons distributed in different places), the stationary activities at destination, and potential mobility (De Vos et al., 2013). Previous studies also highlighted that (im)mobility affects imagination and anticipation of the future, representations and awareness of available opportunities in other places, and the feeling of belonging. Such imagination constitutes an essential part of individual subjective experience (Cangià and Zittoun, 2020).

However, these mobility theories and concepts have not been much mobilized by migration scholars. Post-migration cross-border (im)mobility remains understudied even though it is known that migrants continue to be mobile while living for several years on a territory (Crettaz and Dahinden, 2019). Research on how post-migration cross-border (im)mobility affects migrants' lives only recently started to consider potential mobility (Horn, 2017; Moret, 2018a, 2020; Cangià and Zittoun, 2020).

In this paper, we aim to contribute theoretically and empirically to this literature by adopting the actual and potential mobility theoretical framework (Kaufmann et al., 2004; De Vos et al., 2013; Moret, 2018b; Cuignet et al., 2020). It is used to analyze the unique experience of illegalized residents in the Canton of Geneva (mainly female transnational migrants from Latin America and the Philippines employed in the domestic sector) who, after more than 10 years of illegalized life, were granted a temporary residence permit through a regularization program implemented in 2017–2018. More precisely, we will answer the following questions:

• How does obtaining a residence permit after having endured years of illegalization affects migrants' cross-border mobility?

• What transformative effects are triggered in the life of concerned individuals by this change in cross-border mobility?

“Transformative effects” refer to the different ways and mechanisms in which (im)mobility affects the life of individuals, including their wellbeing, through enabled activities, feelings experienced during travels, imagination, and so on.

To collect the empirical material to answer these questions, thirty-nine migrants were interviewed a first time when they were either about to submit their regularization application, waiting for the authorities' decision, or experiencing the first months of regularized life. Thirty of them were re-interviewed a second time 17–30 months later. At this time point, they already had gained experience in the diverse facets of a regularized life. In parallel, we collected quantitative data on return visits before and after regularization at two time points among a larger sample of migrants in similar situations and among illegalized migrants.

The paper is structured as follows: first, we review the literature about post-migration cross-border (im)mobility and residence status with a focus on practices and consequences on individuals' life; second, we present the selected theoretical framework; third, the context of the research project and methodology are developed. Then, we describe our findings about illegalized residents' cross-border (im)mobility experiences and their subjective experience of the increased opportunities of crossing borders and its implications on actual mobility. Thereafter, we present the identified transformations in other life domains triggered by those changes. Finally, we discuss the results in relation to the theoretical framework.

Illegalized residents' cross-border (im)mobility

There are different ways to become an illegalized resident in European countries, not necessarily involving crossing borders illegally. Many become illegalized residents by overstaying a visa or an expired residence permit (Black et al., 2006; Scheel, 2018). Illegalized residents have in common that they all managed to “stay” despite not being authorized to do so. This is made possible by resources and capacities available at the individual level (social capital, knowledge on how to avoid controls, the relationship with employers, etc.) but also at the contextual level (less repression toward specific categories of migrants, access to primary goods and services such as schools and hospitals, support from charity associations, etc.) (Ambrosini, 2012, 2016; Huschke, 2014). Illegalized residents in Geneva are mainly transnational migrants keeping strong ties with their families and friends in their country of origin. Originally from the Global South, they often see their prolonged unauthorized stay in the Global North in precarious working conditions, as a temporary situation to accomplish personal or family projects, and as a first step toward a better future for themselves and their family (Consoli et al., 2022). The paradox is that they endure long physical separation from family to accomplish it. Despite compensatory strategies that might be implemented not involving transnational corporeal mobility, such as using communicative and virtual mobility, the literature underlines that the lack of a residence permit might restrict their capacity to maintain their formal and informal duties toward their families (see: Fresnoza-Flot, 2009; Safri and Graham, 2010; Bravo, 2017; Dito et al., 2017). Fresnoza-Flot (2009) studied the impact of illegalization on transnational mothering strategies, comparing documented and illegalized transnational mothers working in the domestic sector. Illegalized mothers who cannot visit their children back home try to compensate using phone calls, sending remittances and gifts more frequently. However, their remittances are lower than those of documented mothers since they earn less; besides, it is harder for them to personalize gifts since they know their children less well. Illegalized mothers are particularly regretful of missing important family events. Bravo (2017) studied illegalized migrants' grieving experiences: not being able to visit the country of origin prevents them from giving and receiving emotional support and it induces guilt and sadness.

Cross-border mobility barriers faced by illegalized residents are also known to affect their social and economic life. Indeed, immobility may keep migrants away from engaging in “normal” friendships and romantic relationships since it prevents them from traveling with their partners and friends (Sigona, 2012; Pila, 2016). Moreover, it has been shown that illegalized migrants engaging in transnational economic and professional activities are hindered in those that require to cross borders physically (Portes et al., 2007; van Meeteren, 2012).

These barriers may be overcome. Some illegalized residents find ways to manage cross-border mobility despite lacking the required legal documents. Strategies like falsifying or manipulating documents in order to obtain a visa have been reported (Scheel, 2018). Besides, some knowledge about how to move and cross borders (“savoir-circuler”) is transmitted within certain migrant communities and transborder networks (Tarrius, 2007). However, these strategies have a cost since they expose migrants to risks and sanctions.

Legal status regularization and cross-border (im)mobility

Obtaining a legal status from a Schengen-area country reduces mobility restrictions since it allows intra-European mobility and traveling between the country of residence and the country of origin. Different studies have shown that newly regularized migrants consider the removal of legal barriers to cross-borders as one of the most significant benefits brought by regularization and that visiting family in the country of origin is one of the first things migrants do after obtaining a residence permit (Schuster, 2005; Le Courant, 2014; Kraler, 2019; Consoli et al., 2022). However, little is known about the transformative effects of those first return visits. Ambivalent effects have been reported, since a first visit after a long separation may bring joy and relief but also new concerns about the future (Le Courant, 2014).

Literature about return visits is therefore useful to understand the potential transformative effects triggered by regularization. Return visits are defined as “temporary visits to an individual's place of birth (or the “external homeland”) from a current country of residence” (Chang et al., 2017, p. 314). They might fulfill multiple functions according to the different contexts. These include the maintenance of family and social ties and intimacy, face-to-face emotional support, forging migrants' transnational identities, cultural transmission to children, economic development, strategies of multi-local life or circular migration, tourism and relaxation (Duval, 2004; O'Flaherty et al., 2007; Vathi and King, 2011; Baldassar, 2015; von Koppenfels et al., 2015; Chang et al., 2017; Horn, 2017). These multiple functions potentially fulfilled by return visits could explain why newly regularized migrants value so much new return visits options. In a study on regular migrants living in Switzerland for <10 years, return visits were common. Indeed, 92.3% had visited their country of origin since their arrival, 39.2% reported visiting once or twice per year, 35.1% 3–6 times per year and 18.1% at least once per month (Crettaz and Dahinden, 2019). However, obtaining a residence permit through a regularization program might only partially increase visiting capacity. Indeed, many studies revealed inequalities in their frequency among regular migrants that could result from different needs and desires to visit, but also from unequal access to resources that are needed for traveling (O'Flaherty et al., 2007; Horn, 2017; Crettaz and Dahinden, 2019). Moreover, despite the undisputed importance of these visits, it is not empirically evident whether return visits positively impact wellbeing. For example, in researching regular migrants' transnational practices, Horn and Fokkema (2020) investigated whether transnational ties and return visits should be considered as a resource or as a source of stress. Their results suggested that more frequent return visits were associated with poorer wellbeing. However, they mentioned that this association could be related to the fact that people who visited more frequently were those suffering more from spatial separation from family and friends; their return visits could thus be motivated by a wish to reduce this suffering.

Newly gained possibilities to travel toward third countries2 for leisure, tourism, work, and visiting friends and family have not been frequently researched in the literature on the impact of regularization programs. We know that obtaining a residence permit might enable new opportunities to move legally, temporarily, or permanently to other locations or to engage in circular mobility across several places (Schuster, 2005; Schwarz, 2020; Tedeschi et al., 2022). However, the direct and symbolic impact on wellbeing of being mobile as a result of newly gained access to activities and practices is also to be considered (De Vos et al., 2013).

The effects of a change in mobility regime on migrants' lives: Beyond actual mobility

We consider regularization programs targeting illegalized long-term residents as changes in mobility regimes, since obtaining a residence permit entails the legal capital to engage in cross-border mobility. Indeed, the institutional context impacting (im)mobility options of certain groups of individuals thus changes. The goal of this study is to highlight the various effects of such a structural change on the life of individuals evolving in the context in which it occurs.

To understand the transformative effects of changing cross-border mobility, we have to define the latter. First, we focus on the changing potential and actual corporeal mobility across borders following regularization, thus leaving aside other forms of mobility that are not regulated by legal status, such as communicative mobility. Moreover, as anticipated, this paper argues that an approach looking only at the effects of changes in actual cross-border mobility practices is not enough. Instead, we find it necessary to also consider the effects of changing “acknowledged and real possibilities to be (im)mobile across borders” or “potential mobility” as suggested by mobility scholars (Kaufmann et al., 2004; De Vos et al., 2013; Cuignet et al., 2020). Kaufmann, Bergam et Joye, stated that “the empirical observation and description of actual mobility (past and present) is insufficient to understand the impact of a particular social phenomenon. A study of the potential of movement will reveal new aspects of the mobility of people with regard to possibilities and constraints of their maneuvers, as well as the wider societal consequences of social and spatial mobility.” (2004 p.749). They defined the concept of “motility” as “the capacity of entities (e.g., goods, information or persons) to be mobile in social and geographic space, or as the way in which entities access and appropriate the capacity for socio-spatial mobility according to their circumstances” (2004, p.750). This concept has been further developed by researchers in various disciplines like for instance by Cuignet et al. (2020) who decomposed “mobility” into “motility” (as the potential mobility) and “movement” (the actual physical mobility), to understand how mobility contributes to the wellbeing of the elderly. Migration researchers have already underlined that being aware of one's capacity to cross borders and visit other countries might enhance wellbeing as well as provide emotional benefits (O'Flaherty et al., 2007; De Haas, 2021). Moret (2020), adapted the concept of motility to post-migration cross-border mobility practices and associates motility with the concept of “mobility capital,” defined as “the ability to engage in cross-border mobility practices at particular times but also to remain immobile by choice” (Moret, 2020 p. 235). In this paper, we want to analyze empirically these aspects, drawing systematically on theories and concepts from mobility studies.

To operationalize the actual and potential mobility theoretical framework (Kaufmann et al., 2004; De Vos et al., 2013; Cuignet et al., 2020), changes in cross-borders movements can be directly measured (increase or decrease in return visits or new cross-border mobility toward third countries), but detecting changes in potential mobility implies to observe the transformations of its determinants, namely: access, skills and appropriation (Kaufmann et al., 2004). Access “refers to the means of mobility that people have available and the ways in which their availability is constrained by place, time and other aspects of context” (De Vos et al., 2013, p.431). The residence permit in the country of residence is a form of legal capital that plays an essential role in accessing cross-border mobility (Moret, 2018b). However, legal capital is not the only resource needed to access mobility capital, and regularization might affect other needed resources, such as economic capital. Skills depend on individuals' ability to organize, plan, find the route, and use transportation means to cross the borders despite restrictive visa and migration policies. Individuals with multiple cross-border mobility experiences possess richer skills since they develop knowledge of how to move (Moret, 2018b). The residence permit does not affect skills, but crossing borders legally might require fewer skills than crossing border illegally since skills on bypassing border controls are no longer necessary. Finally, appropriation differentiates formal and actual access to mobility. Indeed, having the right to move does not mean that one feels comfortable circulating since normative prescriptions, values, and representations play a role in “shaping the options that are and are not chosen” (Moret, 2018b, p.104). In parallel, not having the right to move does not keep some migrants from circulating illegally. Interestingly, appropriation also involves the “cognitive work” needed for an individual to identify, evaluate and choose among the set of available cross-border mobility possibilities. Perceived or anticipated capacity to cross borders might not correspond to the actual capacity to cross borders which might be hindered by not properly anticipated or acknowledged concrete obstacles, conditions, or actual costs. It is a simplified representation or anticipation of present and future reality; nevertheless, such cognitive work is necessary to appropriate mobility (Kellerman, 2012).

Finally, most of the literature on legal status, cross-border (im)mobility and its effects adopts a static approach, assessing how cross-border (im)mobility and its effects are experienced by illegalized migrants or by regular migrants at a specific moment in time. Therefore, this literature is not very useful for assessing the unique situation of illegalized residents transitioning out of long lasting forced immobility. A more processual understanding taking duration into account and in which past, present and future are considered as interwoven, is needed. Indeed, the anticipated future can influence the present since migrants undergoing regularization might already enjoy post-regularization life through imagination and future anticipations (Consoli et al., 2022). Nevertheless, the past might also influence the present. For instance, the forced immobility that migrants have experienced might have contributed to forging a deep desire to “get out” (De Haas, 2021) that will affect new cross-border mobility experiences. Moreover, potential mobility and actual mobility also influence each other. Indeed, initiating new cross-border movements requires awareness of new possibilities of crossing borders; the other way around, experiencing cross-border mobility might provide more skills on how to move, increasing motility (Moret, 2018b). It needs to be highlighted that most changes brought by regularization do not occur immediately after receiving the residence permit but develop over time. A change in one life domain affected by mobility, such as family or professional life, might trigger spillover effects on other life domains. However, those changes appear only later and might be or not be visible depending on the timing of observation.

Context, materials and measurements

Study context

This study is set in the context of Canton Geneva, Switzerland, where the extraordinary pilot public policy “Papyrus Operation” implemented between 2017 and 2018 enabled about 3,000 illegalized residents to obtain a residence permit. It was the first time that such a policy was experimented in Switzerland. Only migrants fulfilling some strict criteria could access this regularization. These criteria were: (1) a length of stay of at least 10 years (reduced to 5 years for those having school-age children); (2) basic French proficiency; (3) sufficient financial resources; (4) having a job, and (5) absence of criminal records other than related to irregular residence status. In addition, applicants had to not be rejected asylum seekers. Information about this political context and population characteristics can be found elsewhere (Jackson et al., 2019; Conseil fédéral., 2020).

This study is part of the Parchemins research project, which collected longitudinal qualitative and quantitative data to analyze how this extraordinary regularization program affected the health and wellbeing of concerned individuals (Jackson et al., 2019, 2022). To understand how regularization influences people's lives, we first assessed how regularization affects potential mobility; then if changes in potential mobility were transformed (or not) into new actual mobility, and finally, we identified the transformative subjective and objective effects triggered by both of those changes that might directly or indirectly affect migrants' wellbeing. The multi-methods strategy chosen for the study is characterized by a core qualitative component focused on participants' narratives about their experience of cross-border mobility (actual and potential mobility). We complement these qualitative analyzes with measures of actual cross-border (im)mobility, namely statistics on return visits.

Qualitative fieldwork and analysis

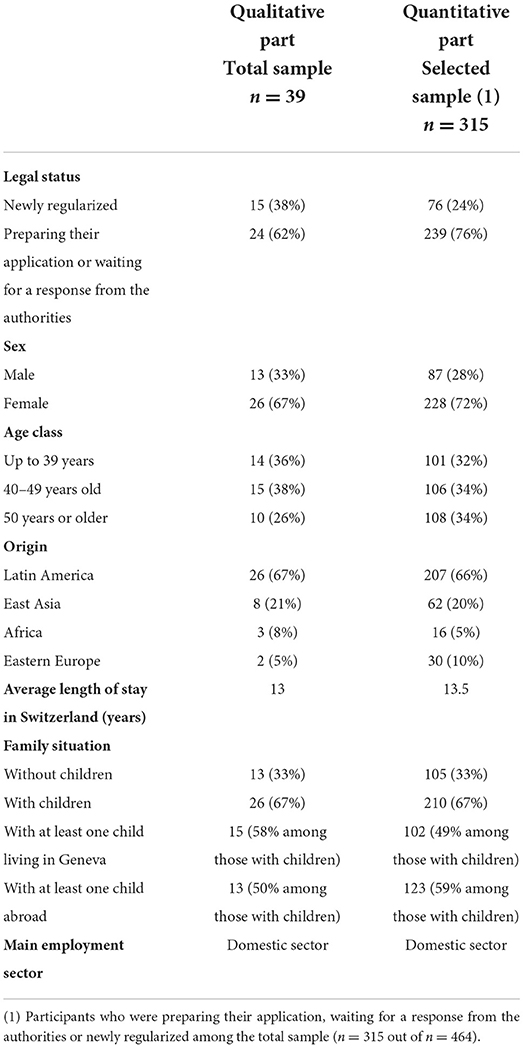

The qualitative longitudinal component of the Parchmin's research project is based on a nested subsample that was recruited among the participants to the quantitative part. The goal was to grasp an in-depth processual understanding of transformations that occur in people's lives triggered by regularization and how individuals adapt to new circumstances. Only individuals transitioning out of illegalization were selected. At the time of recruitment some of them were preparing their application, others were waiting for a response from the authorities, and others were newly regularized. We used a purposive sampling strategy to ensure a heterogeneity of experienced situations according to age, gender, and family situation. Socio-demographic characteristics of the qualitative sample and the selected quantitative samples can be found in Table 1.

The majority of participants were women from Latin America and the Philippines aged between 40 and 49 years. Almost two-thirds had children, either living with them in Switzerland or in the country of origin. Most of them were employed in the domestic sector, as nanny, cleaning lady or in elderly care. Men were more often employed in the sectors of catering or construction.

Thirty-nine participants were interviewed between August 2018 and February 2019, and thirty of them were re-interviewed between March and October 2020 (17–30 months later, 21 months in average) after having experienced the first year(s) of their life with a residence permit. Participants' legal situation was evolving across waves since they were “advancing” in the regularization process. They were asked to talk about their migration trajectory; their life during staying illegally in Geneva; their family dynamics, their aspirations and imagined future and their experience of the regularization and post-regularization life.

Almost all the interviews were conducted in French or English, languages in which most of the participants, who had been living in Geneva for an average of 13 years, were comfortable expressing themselves. A few interviews were conducted in Spanish. The average duration of the first wave interviews was 73 min, the one of the second wave was 65 min. They took place in a location chosen by the participants.

All interviews were recorded and transcribed. Inductive thematic analysis was carried out using Atlas.ti software to detect the perceived effects of the regularization. One of the major themes that emerged in migrants' narratives was the increased opportunities of crossing borders legally and, most importantly, the increased mobility possibilities between the country of origin and the country of residence as well as the subsequent effects of this change on their lives. Therefore, we chose to dedicate the present study to these aspects. After this choice was made, codes were further refined and additional themes inspired by the literature were developed.

It is important to note that most of the second wave interviews were conducted after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated semi-lockdown in Switzerland in March-April 2020 with its related mobility restrictions. Results presented here are based on analyses of narratives that refer to the period up to February 2020 only3.

In the finding section, information on quoted participants includes employment in Switzerland, continental origin, if a visa is necessary to enter Switzerland as a tourist, and family situation or, for participants without dependent young children, age group. This information enables a better understanding of the issues related to regularization and (im)mobility.

Measurements

To supplement the qualitative findings with measurements of actual cross-border (im)mobility before and after regularization, we used quantitative data collected through standardized face-to-face questionnaires during the first two waves of the Parchemins research project (Jackson et al., 2019). Migrants going through the process of regularization and a “control group” of illegalized migrants lacking one or more regularization criteria or who did not intended to apply for regularization were recruited. Since the “control group” needed to be comparable to the “regularization group,” people who were illegalized through asylum rejection and migrants who were in Switzerland for <3 years were not recruited. Data on the sociodemographic, legal, health, financial, living conditions, social participation, migration and employment situation of participants were collected. Return visit practices were assessed with the following questions in the first wave: “Have you returned to visit your home country since your arrival in Switzerland?”, “How many times have you visited your home country since your arrival in Switzerland?” In the second wave questionnaire, participants were asked: “Have you returned to visit your home country since the last interview?” One of the most important limitations of the data is that only information about cross-border mobility between the country of origin and the residence country was collected, leaving aside that migrants could feel at home elsewhere, and other types of cross-border mobility. The variable about visa restrictions applying according to participants' nationalities was constructed from information published by the State Secretariat for Migration of Switzerland4.

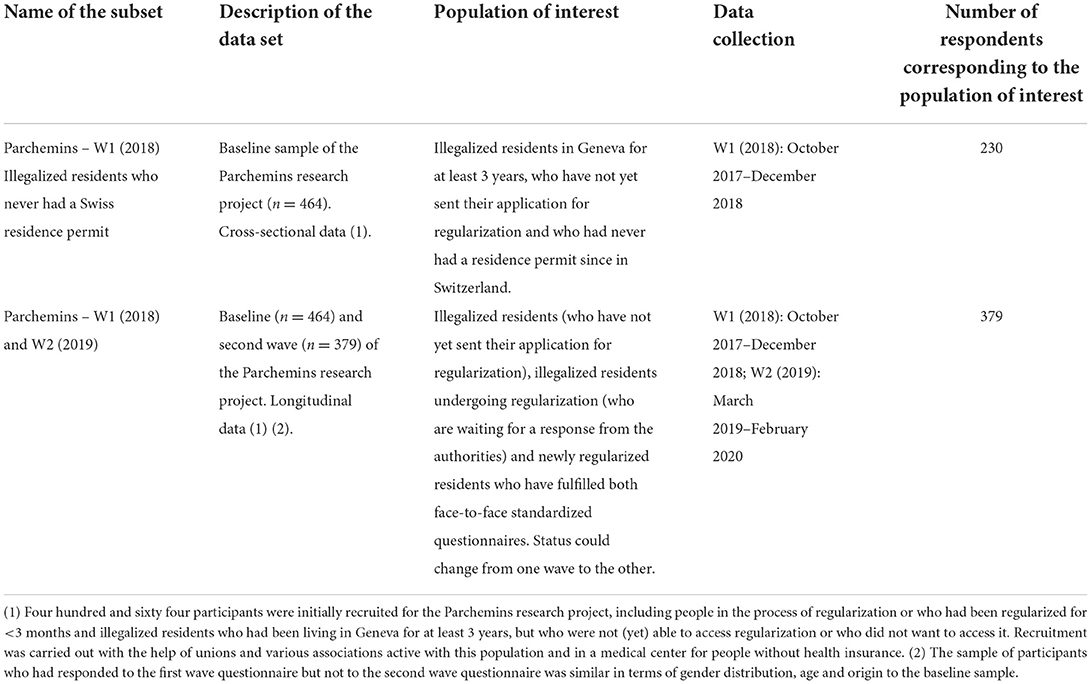

Descriptive analysis was performed using R Statistical Software on two different sub-sets of data. The first subset “Parchemins—W1 (2018) Illegalized residents who never had a swiss residence permit” (Table 2) was used to measure return visit practices during illegalization. The second subset “Parchemins—W1 (2018) and W2 (2019)” (Table 2) was used to observe return visit practices along the phases of the regularization process. For this second step, a “visit history” variable was created from the responses to the questions about return visits in waves 1 and 2.

Differences in the stage of regularization process corresponded to various legal capital endowments and different access to cross-border mobility. For analyzing inequalities in return visit practices, we had to distinguish between: “regularized” who just received their residence permit, “undergoing regularization” who were waiting for a response from the authorities and “illegalized residents” who had not (yet) applied for regularization or had received a negative answer from authorities. As soon as the application for regularization was processed by authorities, concerned individuals could apply for a visa allowing to travel from and to Switzerland legally.

Findings

Cross-border mobility experiences of illegalized residents in Geneva

To better understand changes in perceived potential mobility and actual (im)mobility triggered by regularization, we first present illegalized residents perceived capacity to cross borders and their experiences of actual (im)mobility.

Experiences of cross-border (im)mobility while illegalized

Qualitative analysis reveals two main experiences of cross-border (im)mobility: forced immobility and limited mobility involving risk. Both forms indicate low potential mobility levels that contrast with the aspirations for return visits and travels toward third countries.

Forced cross-border immobility

Many participants stated that crossing borders would have been too risky as it would be impossible for them to return to Switzerland where they had their job which was the main source of income for them and their families; as one participant put it:

“No, I cannot, I cannot go out. Otherwise if I got out, that will be a one-way ticket.” (Transnational mother, Domestic worker, Asia, Visa required).

This perception was mainly expressed when considering return visits or by participants whose nationality required a visa to enter Switzerland. In some cases, it was also reported by people whose nationalities did not require a visa to enter Switzerland but who were very anxious about appropriating cross-border mobility without being authorized to do so because of lack of access, they feared consequences of potential controls at the border for oneself and one's family. For example, in the case of Daya5:

“I'm always afraid of being checked and having to leave everything I've built here” (Mother with children in Switzerland, Domestic worker, Latin America, Visa not required).

For many participants, immobility in the country of residence and the resulting physical separation from family was considered as the price to pay for having enough income for one's family, as expressed in this quote:

“It's always the decision, to decide between money and love. It's difficult to be separated. But it would also be complicated to stay at home and think that my children don't have clothes… it's hard.” (Transnational mother, Domestic worker, Latin America, Visa not required).

Such a statement highlights that being immobile within the country of residence is a constrained choice among a restricted set of possibilities, even a non-choice.

The experience of cross-border immobility was exacerbated by the fact that some of them also limited their movements within the Swiss territory, avoiding cantons or locations where controls could be more frequent, like for this participant:

“The limitations? … before, I didn't take the train going to Zurich, I'was scared. For like … from 2003 to 2004 I didn't travel. I only stayed in Geneva. In the city, the whole time.” (Transnational mother, Domestic worker, Asia, Visa required).

Limited cross-border mobility involving risks

Other participants estimated that they could appropriate cross-border mobility even if their hindered access to legal cross-border mobility implied taking risks. They felt freer to move than those who experienced forced immobility, but the constraints they were facing and the extent of the risks they were exposed to did not allow them to move freely when needed and wanted.

They reported skills and strategies on how to bypass controls, like renewing their passport at each return, to hide the fact that they had overstayed after their visa expiration, entering from an adjacent country, sending friends to check control enforcement at the border before crossing or obtaining a visa illegally. They were however aware that the risk of being discovered and banned from Switzerland was omnipresent, as illustrated by this participant:

“…when you get to the non-European airport [for traveling back to Switzerland after a visit], you can't tell if you're going to come home (Switzerland) or not. You understand ?” (Man in his 50s, Restaurant worker, Latin America, Visa not required).

Many participants know friends or relatives who experienced deportation; some even experienced it themselves. Anticipated stress, as well as past negative experiences at border controls, could be a deterrent to appropriate unauthorized border crossing as frequently as they wished, as in this case:

“At the border (…) sometimes they were not nice toward us… and that bothers me a lot! Because I'm old I don't want to experience bad things. That's why I always avoided going out of Switzerland.” (Woman in her 50s, Domestic worker, Latin America, Visa not required).

Crossing borders could also be particularly stressful and difficult to appropriate when the person was hiding her legal situation to friends, colleagues, and partners, since it revealed their legal status. This is particularly important in the Geneva geographical context, where the city is surrounded by France. As expressed in this case:

“I went to France (…) so we crossed the border and I said: “Oh, nothing happened” And the friend of my boyfriend said: “Oh, you are Asian… where are you from?” (She responds): “Philippines” (The friend): “Oh, so you don't have a permit!” I really cried in front of them.” (Woman in her 30s, Domestic worker, Asia, Visa required).

Moreover, many crossing border strategies involved lying to authorities which could run contrary to one's values and thus be difficult or impossible to appropriate.

This experience of cross-border mobility was mainly expressed by individuals whose nationality did not require a visa to enter Switzerland. Nevertheless, there were also cases of people experiencing it despite being in more unfavorable situations regarding access to legal capital. Appropriation of unauthorized cross-border mobility could be triggered either by the belief that they had nothing to lose in Switzerland or by the confidence in skills about particularly effective strategies to bypass controls. In some extreme cases, forms of cross-border mobility practiced during illegalization were experienced as “forced mobility” due to extremely high pressure and distress related to the need to see relatives, despite the risk exposure. This was the case of Alberta, who was the victim of criminal activities in a desperate tentative to travel to a third country to obtain a document that would have allowed her to visit her country of origin and come back:

“I was caught in France, because I went abroad. (…) there is a person who… was asking 10'000. – EUR to give me a permit. Because I wanted to go home, I wanted to see my family. But she fooled us. She didn't… She didn't do that. And she took the money and she didn't give it back.” (Transnational mother, Domestic worker, Asia, Visa required).

It should be noted that in many cases, the capacity to be mobile was perceived differently according to the aspired form of mobility. Indeed, participants often saw mobility toward third countries as feasible with risk, whereas return visits involving crossing several borders, including those of the Schengen area, were considered not feasible.

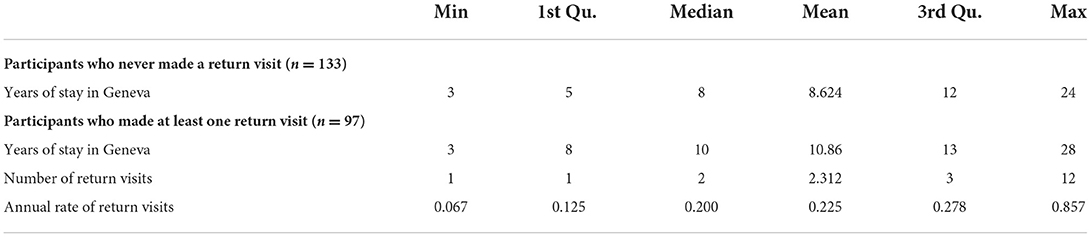

Return visits while illegalized

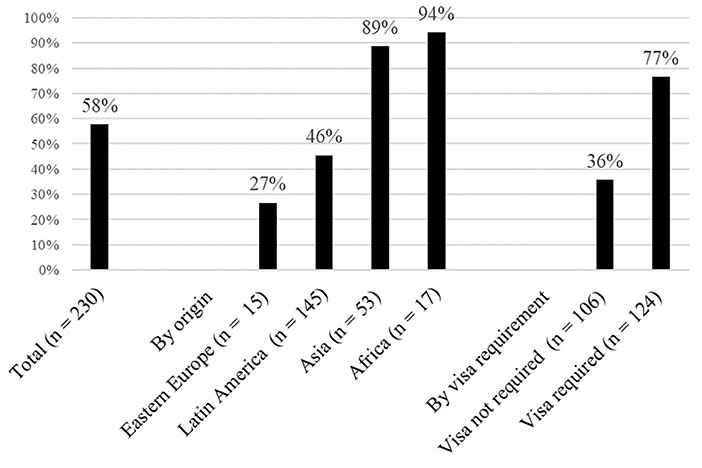

In 2018, among the subset of illegalized participants who had never had a residence permit since arrival in Switzerland (n = 230), 133 (58%) had never made a return visit. This is more than seven times higher than among regular migrants with shorter lengths of stay in Switzerland (see: Crettaz and Dahinden, 2019). Participants from Africa, Asia or with a nationality that requires a visa to re-enter Switzerland were overrepresented among those who had never made a return visit. Participants from Eastern Europe, Latin America and those whose nationality did not require a visa to re-enter Switzerland were underrepresented (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Immobility among illegalized residents by origin and visa requirement in 2018 (% who never made a return visit).

Among those who had never visited their country of origin, the median length of stay in Switzerland was 8 years (minimum 3 years, maximum 24 years) (Table 3). Among those who had returned at least once, the median number of return visits was 2 (minimum 1, maximum 12), the median annual rate of return visits was 0.2 which corresponds to one visit every 5 years. This is shallow compared to regular migrants (see: Crettaz and Dahinden, 2019).

New mobility practices and experience after regularization

In this second section, we present changes in perceived potential and actual mobility, triggered by regularization. Again, we first describe people's perceived capacity of crossing borders and their new crossing borders experiences, then we provide statistics about return visits to give a quantitative measure of actual cross-border (im)mobility.

Experiencing an increase in potential mobility

The narratives regarding new cross-border mobility were similar across individuals and we could not distinguish those who experienced forced immobility from those who experienced limited cross-border mobility anymore. Since the difference in perceived access to cross-border mobility before and after regularization is much stronger than the difference across individuals and groups during illegalization, regularization can be considered as having an important impact on potential mobility compared to other factors such as individual level skills and appropriation; as well as limited access to mobility structurally regulated by various visa regimes.

The new possibilities of crossing borders with the security of being able to return to Switzerland was often acknowledged during the interviews, and it was the predominant theme that emerged when participants talked about what had changed for them during the first year after regularization. For many of them, it was even the only substantial change that occurred in their post-regularization life, like for Alberto:

“The only advantage for me and my wife with the permit is that I can go on vacation to Brazil (country of origin), Italy or Spain without any problems (…).” (Man in his 50s, Restaurant worker, Latin America, Visa not required, 29 months after regularization).

When talking about cross-border mobility, they mostly referred to the capacity to be legally mobile between their country of origin and their country of residence; but the capacity to visit third countries was also often mentioned. Participants became aware of new possibilities of routine, exceptional, emergency, or extended return visits and travel possibilities toward toward other destinations. Awareness of more efficient ways of crossing borders also emerged since participants could start taking direct international flights or trains, options previously avoided due to frequent identity checks. In many cases, the opportunity to cross borders was a completely new experience. Indeed, before arriving in Switzerland, some participants could not move easily across borders because either they had to apply for a visa to travel to the countries they wanted to visit, or they did not have enough resources to travel as one said:

“For me it's something new. (…) In Bolivia I never went out on vacation (…) for me to be here in Switzerland and to be able to go out on vacation with my daughter gives me a lot of pleasure. And my daughter too, we enjoy it, so there you go.” (Mother with children in Switzerland, Domestic worker, Latin America, Visa required, 24 months after regularization).

These new opportunities were quickly internalized as a shift in the mindset encompassing subjectivities and identities, and this was the case even before people actually used them. They started to see themselves as “people who can move across borders and visit their family frequently.” These profound subjective changes continued to unfold after the first experiences of cross-border mobility in post-regularization life.

However, in many cases, pre-existing obstacles limited the perceived gain in freedom of movement. Obstacles that reduce access to cross-border mobility were initially less visible since immobility was attributed to the lack of a residence permit. Subsequently, participants started to experience new trade-offs related to the financial impact of cross-border mobility and expressed difficulties in getting time out of work or in negotiating holidays, especially those who were still working in the domestic sector with many different employers or in non-declared jobs. Many regularized participants thus reported not having acquired real opportunities to make a return visit, like Pablo:

“I want to go there, but it's very expensive. It's on the other side of the world, so (…) I prefer to stay focused and work. For my daughter… to save for her future.” (Father with children in Switzerland, Gardener, Latin America, Visa required, 17 months after regularization).

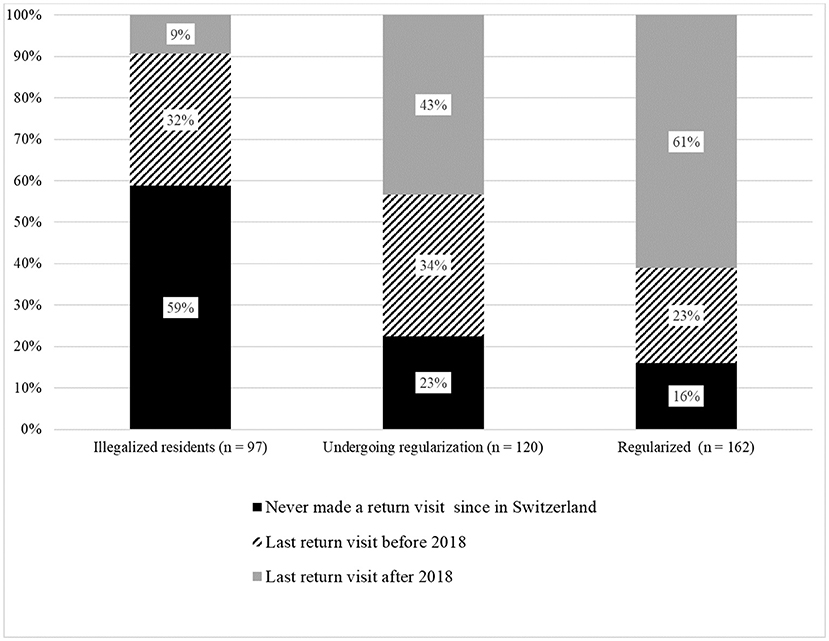

Return visits and regularization

The proportion of illegalized participants who never made a return visit is similar across subsets despite their different composition and despite participants' changing status between waves: this was the case of 58% in the first subset composed entirely of illegalized migrants and 59% in the subset which combines data of the two waves in which only 97 participants out of 379 were still illegalized. Comparing, in the 2019 second subset, illegalized migrants (n = 97), those undergoing the regularization process (n = 120) and newly regularized migrants (n = 162), we notice a significant decline in the percentage of those who never made a return visit, along the stages of the regularization process. Indeed, this percentage drops from 59 to 23% among migrants undergoing regularization and to 16% among newly regularized migrants (Figure 2), a proportion closer to what other studies observed among regular migrants (see: Crettaz and Dahinden, 2019). This can be explained by the fact that 61% percent of newly regularized migrants and 43% of migrants undergoing regularization visited their country of origin after 2018 vs. only 9% percent of migrants still not in the regularization process. For 22% of newly regularized migrants, 22% of those undergoing regularization, and 3% of illegalized migrants, the visit after 2018 was their first return visit since they had arrived in Switzerland.

Transformative effects

Many transformative effects were identified in people's narratives. Some changes were related to actual new mobility practices, some to the awareness of new opportunities of crossing borders, others to the subsequent interplay between both aspects.

Joy, fulfillment and sense of freedom

Immediately after acknowledging their new capacity to legally cross borders, participants felt like regaining control over their lives. They began to feel freer in their social and recreational lives and also less discriminated.

For many, illegalization had felt like “being imprisoned.” Reduced freedom of movement that caused long separation from family and friends, and the feeling of being different were the two main reasons they felt like that. Regularization made them feel they could finally get out of prison after a long sentence, as expressed by Alex:

“And then when I started crossing the border after I got my permit, I felt free … free you know… (…) I felt a bird, free to go.” (Man in his 30s, Construction worker, Latin America, Visa not required, 12 months after regularization).

Many narratives emphasized the intrinsic happiness generated by traveling. New opportunities to travel legally to third countries were particularly appreciated for their symbolic value. In the imaginary, tourism was associated with a feeling of achievement, success, and upward social mobility since in their country of origin, tourism, holiday, and traveling were mainly reserved for the wealthiest groups of the population. When comparing themselves to regular Swiss residents, this mobility enabled them to feel having a normal life like everyone else.

“I enjoyed it very much, because I can go to places in Europe, which was my dream… (…) We went to Italy, we went to lake Como, we went to Rome, yes … and we went to Budapest (…), for me it is fulfillment” (Transnational mother, Domestic worker, Asia, Visa required, 33 months after regularization).

Imagined near and distant futures

Anticipations of the imagined near future began to include a first return visit and the following ones. Participants started to imagine what those visits could look like, anticipating joy and surprise while still being immobile.

The imagined distant future was also affected since plans for the future have been transformed. While illegalized, some had been thinking of returning definitely to the country of origin despite not having earned enough, since the separation from family and friends was too painful; however, after obtaining a residence permit they started to consider the possibility to stay longer in Switzerland while making regular return visits. The following case is very illustrative:

“Before I had in mind that even if I don't have papers, I will go home to see my parents still alive. Because I have a friend here whose parents died, the father and the mother died, and she didn't see them. And it put in my mind that … it wouldn't happen to me. I should go home before my parents are like this. So, I had in mind of going home. Yes. (…) now that I have the permit … it's good. Because financially I can help them also (while seeing them and staying in Switzerland)” (Woman in her 40s, Domestic worker, Asia, Visa required, 7 months after regularization).

More in-depth findings on how imagined futures were affected by regularization are available elsewhere (Consoli et al., 2022).

Family relationships

With the possibility to plan return visits, migrants started to renegotiate their presence and role in the family. The content of the communications with the family changed since the planification of visits and travels toward third countries with family members took up more space. Return visits were perceived as the occasion to restore the relationships that could have suffered from years of separation. In some cases, relatives were unaware that their family member abroad was in an irregular situation. Indeed, it was common for migrants not to reveal their status to their families to prevent them from worrying. As a result, the family back home had assumed they did not want to visit anymore. Other participants could not keep the promises made to their families about meeting again soon. Visits allowed them to provide explanations as well as to manage personal affairs challenging to handle without having been face to face. As one interviewee explained:

“They called me I was a prodigal daughter because I didn't go home for so many years … and when I went home, they had a party, we had a reunion, so it was a memorable one. So, it's like it healed them. (…) I could not explain why I could not go home. (…) I always gave them hope that one day I will come home. (…). My parents cried … oh … it's like there is a needle in their heart that was removed….” (Woman in her 40 s, Domestic worker, Asia, Visa required, 7 months after regularization).

When she was interviewed for the second time, she declared: “I think… the change is they gain their trust in me, because before I said: “I will go home, I will go home” but I didn't fulfill. (…) So it's like the trust was lost. Sometimes I called and they didn't want to talk to me anymore. Because they said: “no you are lying and lying.” But since I went home, they trust me again” (Women in her 40s, Domestic worker, Asia, Visa required, 25 months after regularization).

The first return visits were also the occasions to better organize transnational care arrangements, like in the case of this participant who was able to visit when the person who was taking care of her child died, she said:

“2018 (…) the guardian of my son died. So I went back for 2 weeks (…) It's good for me because I could see personally what's the situation and what they need. So when I saw they are… cause they are already adolescents, they organize themselves. Except the financial…. So, that's it. I saw that I don't have really a problem for my family there.” (Transnational mother, Domestic worker, Asia, Visa required, 29 months after regularization).

Also traveling to third countries contributed to transformative effects regarding family relationships since many participants could finally visit family members who have migrated elsewhere in Europe.

Social inclusion

Higher capacity to travel to third countries enabled participants and their families to take part in social activities from which they used to be excluded, such as trips organized by the school or church, sports and shopping activities, social gatherings, and events in nearby France.

“For example, now, I'm going to France, I have a friend's wedding, you know. It's nice to go to a wedding like that. Now I can even rent a car. It's cool. Now I don't have to find an excuse, like ‘I can't because I work this day and I can't be replaced” (...). No, now I say “Yes I'm coming!”. And that's good, that's the beauty of having a permit.” (Man in his 30s, Construction worker, Latin America, Visa not required, 12 months after regularization).

Those visits also enabled visits to romantic partners and friends who lived outside the Swiss borders.

“Now I go out from time to time in France. I've already been to Spain. This is something that before I couldn't do. Because I have friends who are there, but we were always on the phone saying “we'll see when we can meet.” So that is something pretty important for me.” (Mother with children in Switzerland, Domestic Worker, Latin America, Visa not required, 27 months after regularization).

Economic and administrative situation

Traveling toward the country of origin enabled to solve complex administrative situations, like divorcing after a long separation, renewing a driving license, putting under one's own name proprieties financed by sending remittances, managing savings for retirement or investing in a new project.

“I can put my things under my name, if I want to sell my things over there, I mean, nobody will question me because it's under my name. That's the thing. It worried me a lot because what if I go back home and… I heard a lot of stories that when they go back home, the property is under the sister or the brother, at the end of the day, nothing.” (Woman in her 50s, Domestic worker, Asia, Visa required, Undergoing regularization).

Traveling to third countries also opened up new professional opportunities like driving cars across borders or, for domestic workers, being able to follow their employers when they were traveling. Some participants also highlighted that it was an occasion to reduce the cost of living since buying food is less expensive in France than in Switzerland.

However, costs of traveling and visiting the country of origin started to compete with sending remittances and savings; but also, with expenses associated with the new lifestyle that regularization has made accessible, like renting a bigger apartment, buying a car, having a health insurance, education expenses, leisure activities. Many participants thus reported new trade-offs and a decrease in purchasing power after regularization.

Changing sources of stress

Just knowing to be mobile across borders has a reassuring effect. It marked the end of the fears and perceived risks for those who were used to live near borders or to cross them. It also marked the end of the fear of being unable to visit if a relative was sick or had died, and it opened the possibility to get and give face-to-face emotional support from and to family and friends in rough times.

“If you have to leave Geneva, to take a vacation (…) you just take the flight, you come, you relax, you stay with us for a while, and then you go back to your life in Geneva.” (…) if things ever really went wrong, I can really say to myself “ok, you (family in the country of origin) pay half the ticket because I'll come.” And it's sure that they will still manage to pay half of the ticket to go on vacation and come back. So that was quite important for me, knowing that I had brothers, sisters, mum, uncles, aunts, cousins.” (Mother with children in Switzerland, Latin America, Visa not required, 27 months after regularization).

Even for those who had made return visits while illegalized, having a residence permit enabled them to enjoy better the time spent with the family during visits instead of worrying about going back to Switzerland.

However, anticipations of mobility and awareness of opportunities to cross borders also generated new stress. First, discovering the economic trade-offs brought on by the anticipated and actual costs of cross-border mobility was stressful. When visits were possible legally but not economically, participants felt particularly frustrated. Second, some participants were stressed because of the long-time interval since the last visit to the country of origin. They were apprehensive about becoming aware of how relationships may have evolved at distance, like this one:

“There is a lot of changes since I left the Philippines: I don't even know my nieces and nephews and stuff like that. (…) They know that I am their auntie, but we don't have that kind of physical bonding. It's very hard. (…) It's kind of … you're excited to see them but on the other hand … how are they going to react? They are like strangers. I don't know. It's kind of balanced between positive and negative. But I'm on the side of the positive, you know, of course they are your family.” (Woman in her 50s, Domestic worker, Asia, Visa required, Undergoing regularization).

In some cases, new life dilemmas emerged after a first return visit. This could generate guilt or doubt about oneself's capacity to adapt to the new context. This quotation illustrates this:

“I was in December for a month and a half with them in Ecuador, so after I got there I was homesick because spending time with the family is wow... sharing a lot of things with them every day, and then coming back here again... I've always found that I'm good here. I have made friends; I have a life here but there is something in my heart that is always empty and it is my family.” (Woman in her 30s, Domestic worker, Latin America, Visa required, 27 months after regularization).

Concretely, a first return visit after a long separation meant being exposed to intense contact with relatives with whom migrants were not used sharing everyday life and intimacy and being exposed to their social and economic expectations. During this first visit, migrants also frequently felt disappointed about the limited impact of their remittances on the economic situation of their family and relatives. Like in her case:

“I was frustrated. (…) Because all the things that I provide, it's gone. Seems like nothing. (…) I'm really frustrated because (…) I've spent lots of money, almost all my salary I've sent to them.” (Transnational mother, Domestic worker, Asia, Visa required, Undergoing regularization).

Moreover, return visits often co-occurred with sad events like the illness or funerals of family members and friends. If not being able to return in case of an adverse event was perceived as a big stressor, returning and managing such an event could also be very stressful.

Finally, although visits to the country of origin were highly desired after regularization, some participants mentioned experiencing a certain moral pressure about the frequency of those visits in the future as a result of family expectations or self-imposed expectations. If during illegalization, it was socially accepted that visits were impossible, after regularization, this was not the case anymore.

Discussion and conclusion

The main objectives of this study were (1) to assess how regularization programs affect the cross-border mobility of concerned individuals and (2) to explore the direct and indirect transformative effects triggered by this change.

After entering the regularization process, most participants transformed their increased perceived potential mobility into cross-border mobility practices. An important proportion of those who had never returned to the country of origin could finally make their first return visit, a finding consistent with former qualitative studies (Schuster, 2005; Le Courant, 2014); here, we could additionally quantify this change. We highlighted transformative effects on emotional life, projects for the future, family relationships, social life, the economic and administrative situation as well as perceived sources of stress. Some of the identified transformative effects, such as disappearing stress and fear about not being able to visit the family before it is too late or “feeling normal, like everyone else,” were experienced independently of actual cross-border mobility. These effects could not have been identified if we had not observed potential mobility.

This study reinforces the argument about the importance of considering potential mobility in research on post-migration cross-border (im)mobility and/or consequences of changes in mobility regimes on migrants' life and wellbeing (O'Flaherty et al., 2007; Moret, 2018b; Cangià and Zittoun, 2020). Moreover, shedding light on the perceived potential mobility in which actual movements were embedded enabled to better situate observed actual mobility within its context of possibilities and constraints (Kaufmann et al., 2004). This made it possible to better understand why strongly desired return visits might be experienced as a source of stress in some cases (Horn and Fokkema, 2020). This was the case, for example, when participants had to limit their visits due to limited economic and temporal resources, visiting mostly for emergencies, such as a relative's deteriorating health or death.

Our findings underlined that some groups of illegalized residents were able to appropriate cross-border mobility despite not being authorized to do so. However, those practices remained constrained and limited. Regularization, as a change at the structural level regulating access to cross-border mobility, enabled increased perceived potential mobility. It did so more significantly than—individual level—skills and appropriation, as well as access to mobility regulated by various visa regimes during illegalization. Nevertheless, access is also regulated by economic capital and time resources at the individual level. In some cases, the lack of these resources hindered access to cross-border mobility after regularization. Skills in moving without authorization were no longer required. Instead, new skills were needed, such as managing economic trade-offs (e.g., choosing between return visits or sending remittances). In addition, it was necessary to learn how to integrate return visits in the implemented transnational practices to maintain relationships with family and friends living abroad. Moreover, the residence permit eased the efforts to appropriate cross-border mobility. However, we cannot exclude that appropriating “immobility” could become more problematic in the long-term, due to emerging social expectations of regular visits and travels.

Observing the situation at different points in time was enlightening to analyze the unfolding adaptation process. Some changes, such as imagined and anticipated cross-border mobility, occurred much faster than others. Some participants readjusted their perceived potential mobility after reality checks, acknowledging limited and unanticipated economic and time resources. This suggests that cognitive appropriation of increased potential mobility is a process that requires time and which is built through interactions with the new legal context. More broadly, newly regularized migrants' experience of cross-border mobility cannot be understood without looking at their past. Having experienced long-lasting illegalization and related forced immobility continues to affects their experiences of cross-border mobility even after regularization. This was the case when participants anticipated a first return visit after a very long separation, or experienced only a limited increase in potential mobility since they lacked money or time to move as freely as their new legal situation enabled them. Indeed, the new possibilities of crossing borders did not erase the painful consequences of long years of separation from relatives and did not—at least immediately—solve financial and job precarity. These results match those in Le Courant study (2014), in which participants were also separated for a long time from family and friends. Considering the influence of the past, also helps to understand why return visits can be simultaneously experienced as a resource and a source of stress, and do not have to be either one or the other (Horn and Fokkema, 2020).

Despite offering original results about a hard-to-reach population, several limitations should be considered in the interpretation and generalizability of our findings. First, the baseline Parchemins sample is a convenience sample, and as such, the population under study might not be representative of illegalized residents in Switzerland or Geneva. Second, the sample excludes people who were illegalized after asylum rejection and includes only people who remained in Switzerland for at least 3 years; this, together with the fact that only those who further remained in Switzerland continued to take part in the study, might have led to an “immobility bias.”

We encourage replication of this study in other contexts. Even if most regularization programs in the Schengen area are expected to have similar effects on the cross-border mobility experience, the access criteria required by different regularization programs varies a lot, shaping the effects of illegalization and regularization on people's lives as well as the sociodemographic characteristics of the newly regularized populations. For instance, in European comparison, the length of stay required to access the Operation Papyrus regularization was relatively long (Apap et al., 2000; Baldwin-Edwards and Kraler, 2009). Furthermore, we also encourage quantitative panel studies which operationalize potential and actual mobility, as well as subjective wellbeing in such contexts of changing mobility regimes. Finally, taking into account all the identified subjective and objective transformations occurring simultaneously across various life domains, changes related to cross-border mobility triggered by regularization have to be considered by future research as crucial ingredient in the complex machinery of adaptations and readjustments that occurs in the early stages of post-regularization life. They might lead to significant long-term effects, also concerning family members and friends, that could not be observed in the current study yet.

Data availability statement

Qualitative materials are not publicly available for the respect and protection of the research participants. The quantitative datasets will be deposited in an open archive after the project is completed and are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to bGlhbGEuY29uc29saUB1bmlnZS5jaA==.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of Geneva Canton, Switzerland (CCER 2017–00897). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

LC conceptualized and drafted the manuscript, conducted all the analyses, and collected the qualitative data. YJ and CB-J designed the Parchemins research project, the framework within which this manuscript was elaborated, which provided quantitative data, and also contributed with substantial comments on the first draft. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study is supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant number : 100017_182208) as well as the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research LIVES-Overcoming Vulnerability: Life Course Perspectives (NCCR LIVES) (Swiss National Science Foundation grant number: 51NF40-185901). Funders had no role in the development of the study design, data collection, interpretation and dissemination.

Acknowledgments

First, authors would like to thank the research participants who shared their stories and experiences without which this study would have been impossible. Furthermore, we would like to thank Aline Duvoisin, Jan-Erik Refle and Julien Fakhoury (members of the Parchemins research group) for their expertise and assistance throughout many aspects of our study. The authors also wish to thank all partner organizations, the Swiss Federal Office for Public Health, the University of Geneva, the Geneva University Hospitals, the Fondation Safra and the Geneva Canton Departments of Health and of Social Affairs for their support in the implementation of the Parchemin's research project.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1 It's possible to experience simultaneously forced mobility at one level (e.g., inside the Schengen area) and forced immobility at another level (e.g., across the Schengen area and the country of origin).

2 In this paper, “third countries” refer to all countries that are neither the country of residence nor the country of origin.

3 More details on how migrants were affected by the pandemic can be found in the article by Burton-Jeangros et al. (2020).

4 Available online at: https://www.sem.admin.ch/dam/sem/fr/data/rechtsgrundlagen/weisungen/visa/bfm/bfm-anh01-liste1-f.pdf.download.pdf/bfm-anh01-liste1-f.pdf (accessed February 16, 2022).

References

Ambrosini, M. (2012). Surviving underground: irregular migrants, Italian families, invisible welfare. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 21, 361–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2397.2011.00837.x

Ambrosini, M. (2016). From ‘illegality' to tolerance and beyond: irregular immigration as a selective and dynamic process. Int. Mig. 54, 144–159. doi: 10.1111/imig.12214

Apap, J., De Bruycker, P., and Schmitter, C. (2000). Regularisation of Illegal Aliens in the European Union-Summary Report of a Comparative Study. Available online at: https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/ejml2&i=273 (accessed February 1, 2022).

Baldassar, L. (2015). Guilty feelings and the guilt trip: Emotions and motivation in migration and transnational caregiving. Emot. Space Soc. 16, 81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.emospa.2014.09.003

Baldwin-Edwards, M., and Kraler, A. (2009). REGINE-Regularisations in Europe. Study on Practices in the Area of Regularisation of Illegally Staying Third-Country Nationals in the Member States of the EU. Vienna: International Center for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD).

Bansak, C. (2016). Legalizing undocumented immigrants. IZA World Labor. 245. doi: 10.15185/izawol.245

Black, R., Collyer, M., Skeldon, R., and Waddington, C. (2006). Routes to illegal residence: A case study of immigration detainees in the United Kingdom. Geoforum. 37, 552–564. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2005.09.009

Bravo, V. (2017). Coping with dying and deaths at home: How undocumented migrants in the United States experience the process of transnational grieving. Mortality. 22, 33–44. doi: 10.1080/13576275.2016.1192590

Burton-Jeangros, C., Duvoisin, A., Lachat, S., Consoli, L., Fakhoury, J., and Jackson, Y. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdown on the health and living conditions of undocumented migrants and migrants undergoing legal status regularization. Front. Public Health 8:596887. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.596887

Cangià, F., and Zittoun, T. (2020). Exploring the interplay between (im)mobility and imagination. Cult. Psychol. 26, 641–653. doi: 10.1177/1354067X19899063

Chang, I. Y., Sam, M. P., and Jackson, S. J. (2017). Transnationalism, return visits and identity negotiation: South Korean-New zealanders and the Korean national sports festival. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport. 52, 314–335. doi: 10.1177/1012690215589723

Chauvin, S., Garcés-Mascareñas, B., and Kraler, A. (2013). Working for legality: Employment and migrant regularization in Europe. Int. Migrat. 51, 118–131. doi: 10.1111/imig.12109

Conseil fédéral. (2020). Pour un Examen Global de la Problématique Des Sans-Papiers. Rapport du Conseil Fédéral en Réponse au Postulat de la Commission des Institutions Politiques du Conseil national du 12 avril 2018 (18.3381). Available online at: https://www.parlament.ch/centers/eparl/curia/2018/20183381/Bericht%20BR%20F.pdf (accessed February 1, 2022).

Consoli, L., Burton-Jeangros, C., and Jackson, Y. (2022). When the set of known opportunities broadens: aspirations and imagined futures of undocumented migrants applying for regularization. Swiss J. Sociol. 48, 353–376. doi: 10.2478/sjs-2022-0018

Crettaz, E., and Dahinden, J. (2019). “How transnational are migrants in Switzerland? An analysis of the migration-mobility-transnationality nexus” in Migrants and Expats: The Swiss Migration and Mobility Nexus, eds. I. Steiner, and P. Wanner (Cham: Springer International Publishing) 267–291.

Cuignet, T., Perchoux, C., Caruso, G., Klein, O., Klein, S., Chaix, B., et al. (2020). Mobility among older adults: Deconstructing the effects of motility and movement on wellbeing. Urban Studies. 57, 383–401. doi: 10.1177/0042098019852033

De Haas, H. (2021). A theory of migration: the aspirations-capabilities framework. Comp. Migrat. Studies. 9:8. doi: 10.1186/s40878-020-00210-4

De Vos, J., Schwanen, T., Van Acker, V., and Witlox, F. (2013). Travel and subjective well-being: a focus on findings, methods and future research needs. Trans. Rev. 33, 421–442. doi: 10.1080/01441647.2013.815665

Dito, B. B., Mazzucato, V., and Schans, D. (2017). The effects of transnational parenting on the subjective health and well-being of Ghanaian migrants in the Netherlands. Popul. Space Place. 23:e2006. doi: 10.1002/psp.2006

Duval, D. T. (2004). “Conceptualizing return visits,” in Tourism, Diasporas and Space, eds. T. Coles and J.T. Dallen (London : Routledge), 64–75.

Fakhoury, J., Burton-Jeangros, C., Consoli, L., Duvoisin, A., Courvoisier, D., and Jackson, Y. (2021). Mental health of undocumented migrants and migrants undergoing regularization in Switzerland: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 21:175. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03149-7

Finotelli, C., and Arango, J. (2011). Regularisation of Unauthorised Immigrants in Italy and Spain: Determinants and Effects. Available online at: https://raco.cat/index.php/DocumentsAnalisi/article/view/248439 (acessed February 1, 2022).

Fresnoza-Flot, A. (2009). Migration status and transnational mothering: the case of Filipino migrants in France. Global Networks. 9, 252–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0374.2009.00253.x

Hobolth, M. (2014). Researching mobility barriers: the European visa database. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 40, 424–435. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2013.830886

Horn, V. (2017). Migrant family visits and the life course: interrelationships between age, capacity and desire. Global Networks. 17, 518–536. doi: 10.1111/glob.12154

Horn, V., and Fokkema, T. (2020). Transnational ties: resource or stressor on Peruvian migrants' well-being? Popul. Space Place. 26:e2356. doi: 10.1002/psp.2356

Huschke, S. (2014). Fragile fabric: Illegality knowledge, social capital and health-seeking of undocumented Latin American migrants in Berlin. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 40, 2010–2029. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2014.907740

Jackson, Y., Burton-Jeangros, C., Duvoisin, A., Consoli, L., and Fakhoury, J. (2022). Living and Working Without Legal Status in Geneva. First Findings of the Parchemins Study. Genève, Université de Genève (Sociograph– Sociological Research Studies, 57 b). Available online at: https://www.unige.ch/sciences-societe/socio/files/8216/6083/4918/Sociograph_57_b_open_access.pdf (accessed September 2, 2022).