- 1School of Education, Beit Berl College, Kfar Saba, Israel

- 2Doctoral School of Multilingualism, University of Pannonia, Veszprem, Hungary

- 3School of Communication Disorders, Haifa University, Haifa, Israel

This study investigates the development of rhetorical competence in Hebrew-speaking elementary students' argumentative writing through their use of discourse stance (DS). DS was analyzed across three dimensions each containing three characterizing categories (i.e., for (orientation dimension the categories: writer, text, audience; for attitude dimension: epistemic, deontic, emotional, and for generality dimension: personal, impersonal and generic). Participants (N = 293) in 2nd grade (age range 7 to 8 years), 3rd grade (ages 8–9), 4th grade (ages 9–10) and 5th grade (ages 10–11) wrote an argumentative essay on a familiar topic. Texts were segmented at the clause level and coded for DS categories; analyses addressed grade differences in dimension use (research question 1), developmental trajectories of categories (research question 2), and within-grade co-occurrence patterns (research question 3). Results show uneven pathways. Orientation and generality increased with grade, whereas attitude was relatively stable. Category-level patterns shifted from reliance on writer orientation, emotional stance, and personal generality in younger students to text orientation, epistemic stance, and generic generality in older students. Association analyses revealed that stance resources clustered into coherent profiles that reorganized developmentally: Grade 2 texts centered on a writer-personal-emotional bundle, whereas Grade 5 texts consolidated a text-generic-epistemic profile, with Grades 3–4 as a transitional phase. Across grades, audience orientation was rare. These findings provide one of the first systematic accounts of DS development in Hebrew children's writing and extend cross-linguistic evidence on early academic literacy. They indicate that rhetorical competence develops not only via increased use of individual stance resources but also through their reorganization into coherent stance profiles, underscoring the value of instruction that fosters generic formulations, epistemic reasoning, and audience awareness.

1 Introduction and background

Transforming an idea into a coherent, well-structured text requires integrating different layers of writing-related knowledge, including linguistic, textual, and structural knowledge. Linguistic knowledge refers to control over morphology, syntax, and lexical choice; textual knowledge involves cohesion and the use of discourse relations across clauses; and structural knowledge concerns the global organization of ideas and genre-specific components that shape the overall rhetorical architecture of the text (see Berman and Nir-Sagiv, 2007; Ravid and Tolchinsky, 2002). It also requires awareness of the social context, the intended audience, the purpose, and the rhetorical strategies. Writing is a complex activity that encompasses both product and process aspects. In this study, we emphasize the process-oriented view of writing, where text production is understood as recursive planning, monitoring, and revising rather than a static end-product. This perspective is crucial for examining how children's rhetorical competence develops through their deployment of discourse stance. It unfolds recursively, involving planning, generating, monitoring, and revising (Bereiter and Scardamalia, 1987; Hayes, 2012). In this sense, writing is as much about discovering or inventing ideas as about articulating them convincingly (Hayes and Flower, 1980) especially in argumentative texts. From a developmental perspective, children's attention to written forms begins before formal instruction, when they experiment with what they deem to be “readable writing” (Ferreiro and Teberosky, 1979, 1982; Stavans, 2015a,b; Teubal et al., 2007). With age and experience, they contend with both the “what” of writing—content—and the “how”— audience, language, and genre constraints (Deane et al., 2008), progressing along a continuum marked by continuity, complexity, and sociality (Stavans et al., 2019; Seroussi et al., 2020b; Ravid and Tolchinsky, 2002). As writers develop greater control over these cognitive and linguistic processes, their attention increasingly shifts toward rhetorical competence-translating ideas into effective and appropriate linguistic forms to communicate with readers or interlocutors. This competence evolves from a personal activity-ideation-into a socially situated act, necessitating the adoption of an appropriate discursive stance. Discourse stance is “a linguistically articulated form of social action” (Du Bois, 2007, p. 139), encompassing language, social interaction, and sociocultural values, and requiring contextual assessment. From a process perspective, stance-taking is not merely the product of writing but an integral part of the ongoing act of composing, as writers negotiate ideas, audience, and genre constraints in real time.

Discourse stance emerges through both cultural traditions and early communicative experiences. For example, Israeli discourse practices have been linked to the dialogic and interpretive nature of Talmudic traditions (Blum-Kulka et al., 2002). These culturally rooted habits of debate and interpretive exchange may make stance-taking more natural for Hebrew-speaking children, who encounter evaluative and argumentative talk from an early age, even before formal instruction. From a developmental perspective, research has shown that stance-taking appears early in oral interactions, even before formal schooling begins, as children engage in evaluative, affective, epistemic, and generality expressions in everyday conversations (Kyratzis, 2004; Shiro, 2008; Shiro et al., 2019). These early stance markers serve as foundations for written discourse, particularly as children begin producing texts in school settings. The form and frequency of stance markers in children's writing have been shown to vary with grade level and genre (Berman et al., 2002; Uccelli et al., 2013).

What is discourse stance? Stance is a multifaceted construct examined across disciplines. In sociolinguistics and discourse analysis, this concept refers to how individuals position themselves within social interactions and cultural contexts (Kyratzis, 2004; Ochs, 1996), with stance markers being context-dependent (Kärkkäinen, 2006). Narrative studies have highlighted evaluative language as a tool for expressing subjectivity and stance (Labov and Waletzky, 1967). Linguistic approaches focus on lexical and grammatical markers of attitude and commitment (Biber and Finegan, 1989). Communication studies view stance as a strategic linguistic choice to achieve communicative goals and influence audience. Despite the varied disciplinary perspectives, a common thread is the emphasis on how language users convey attitude, beliefs, and positioning through linguistic choices. Stance reflects authorial positioning—adopting a perspective on issues and relating to others with differing viewpoints (Bazerman, 2023, p. 81).

Given the complexity of discourse stance, scholars have called for operational definitions that delineate its scope (Englebretson, 2007). We adopt the framework of Berman and colleagues (Berman et al., 2002; Berman, 2004; Berman and Ravid, 2009), which treats stance as a multidimensional construct. It identifies three interrelated dimensions through which speakers and writers position themselves in relation to content, audience, and communicative context. These dimensions-orientation, attitude, and generality-function interactively to reflect the rhetorical choices embedded in text construction. Orientation addresses the relationship between writer, text, and reader. It may center on the sender (e.g., “I think”), the recipient (e.g., “you know”), or the text itself (e.g., “this essay will discuss”). These orientations are not mutually exclusive and can alternate within a single discourse, reflecting communicative intentions and audience awareness. attitude reflects the writer's evaluation of text propositions. It includes epistemic stance (certainty, doubt, evidentiality), deontic stance (judgment, obligation), and affective stance (emotional responses). These attitudinal modes span a continuum from objective and abstract to personal and emotionally invested, and their integration is considered a hallmark of advanced discourse competence. Generality concerns the level of abstraction or specificity in reference, ranging from personal and specific (e.g., “my parents think”), to generic (e.g., “people tend to think”), to impersonal (e.g., “it is well known that…”). This dimension pertains to the specificity or impersonal generality in referencing people, places, events, and temporal markers, and interacts with the other two dimensions. For instance, sender-oriented discourse tends to be more specific and personalized, while recipient or text-oriented discourse often adopts impersonal forms. The interplay of these dimensions determines the degree of involvement or detachment in discourse stance (Jisa and Tolchinsky, 2009). Notably, this framework promotes the view of stance as a continuum of functional linguistic choices that unfold dynamically within the context of genre, modality, and development.

We chose to adopt Berman et al.'s (2002) multidimensional framework for analyzing discourse stance because it draws on a rich interdisciplinary body of theory and is particularly suited to capturing the developmental and functional aspects of children's written production. The multidimensionality of this work is grounded in key concepts such as evaluation, involvement, perspective, agentivity, and distancing, providing a principled lens for examining how writers position themselves in relation to content, audience, and genre. Its emphasis on the interrelated dimensions of orientation, attitude, and generality aligned well with our goal of tracing how discourse stance emerged and evolved in children's argumentative writing. Having outlined the multidimensional nature of discourse stance, we next consider how these dimensions are realized across different modalities of communication, particularly in the contrast between spoken and written discourse.

How is discourse stance manifested? Discourse stance varies across linguistic modalities due to differing communicative contexts and purposes. Spoken discourse, characterized by real-time interaction, often employs first and second-person pronouns, contractions, and discourse markers to convey immediacy and personal engagement (Biber and Conrad, 2009). These features facilitate stance expression through interactive cues and immediate feedback. In oral interactions, stance tends to be subjective and engaging (e.g., “Listen to this!”), incorporating non-linguistic elements, such as intonation, posture, and gestures. Conversely, written discourse stance, particularly expository writing in educational contexts, conveys stance through linguistic means, reflecting an assertive and epistemically grounded attitude (Uccelli et al., 2013). In academic writing, assertive and emotionally charged stances, typical of narrative writing, are often less valued than detached approaches that are open to alternative viewpoints (Aull and Lancaster, 2014). As writers develop, they must acquire a wide range of linguistic resources that allow them to adapt their stance to different genres and contexts. While modality highlights differences between spoken and written stance, genre imposes an additional layer of constraints. To better situate our study, we therefore turn to how stance varies across genres, with particular attention to argumentative writing.

Is discourse stance intrinsically linked to genre? The overarching answer is yes. Narrative writing constructs plots connecting readers to protagonists and events, often employing emotive stances to express attitude (Biber, 2004). In contrast, academic and informative writing prioritizes precision, logic, and substantiation, generally adopting a detached or “depersonalized” stance, minimizing personal emotions to align with academic conventions that emphasize objectivity and evidence-based arguments. Argumentative writing is widely regarded as one of the most cognitively and linguistically demanding genres, particularly in the context of school-based literacy development (Uccelli et al., 2013). Unlike narrative or descriptive genres, argumentative writing requires students to formulate a clear claim, support it with coherent reasoning, anticipate opposing views, and organize their ideas in a logically structured manner (Stavans et al., 2019; Seroussi et al., 2020b; Vilar and Tolchinsky, 2022; Wang et al., 2024). These demands foster the use of advanced linguistic resources, including complex syntax, abstract vocabulary, and cohesive devices (Olinghouse and Wilson, 2013). Well-constructed arguments require students to adopt a clear position, provide supporting evidence, and often acknowledge alternative viewpoints (Ferretti and Lewis, 2013). Thus, argumentative writing demands a high degree of rhetorical planning and audience awareness. The cognitive and rhetorical demands of argumentative writing make it a particularly suitable context for examining discourse stance, the linguistic expression of a writer's attitude, positioning, and engagement with content and audience. When writing an argumentative text, writers are required to take a position, justify it through reasoning, and often anticipate counterarguments, thus making their stance linguistically explicit (Berman, 2004). As students express certainty or doubt, appeal to shared knowledge, or distance themselves from claims, they employ linguistic tools such as epistemic markers, modal verbs, evaluative language, and impersonal references-features closely linked to the development of rhetorical competence (Uccelli et al., 2013). These markers reflect how students position themselves both cognitively and socially in relation to their arguments and readers. Given the cognitive and rhetorical demands of argumentative writing, it is important to ask what empirical evidence exists for children's use of stance in this genre. The following section reviews developmental studies of school-age writers.

Is there evidence of discourse stance in the argumentative writing of school-age children? Research shows that stance-taking emerges early in dialogic argumentation. For example, preschoolers and adolescents use evaluative and evidential markers, politeness strategies, and embodied cues to express and negotiate positions (Goodwin, 2006; Shiro et al., 2019). Research has also shown that preschoolers use distancing devices (such as appeals to generality, impersonal attributions, and third-party referencing) to maintain peer solidarity during disagreement or argumentative episodes (Stavans and Zadunaisky-Ehrlich, 2024). However, these findings pertain primarily to dialogic, interaction-based discourse, where children co-construct meaning with a peer in real time. In contrast, little is known about how children express stance in autonomous, self-sustained written texts. This is especially true in the early school years, when students are still developing familiarity with expository genres and argumentative writing. This task poses distinct developmental challenges. In writing, children must encode their stance through linguistic means without the support of real-time interlocutors, while also meeting conventional expectations for syntax, coherence, text structure, and genre conventions. (Gómez Vera et al. 2016), for example, showed that higher-quality opinion texts in the fourth grade were associated with greater lexical diversity. Such lexical flexibility supports the expression of discourse stance by enabling writers to signal their epistemic and affective positioning more effectively. Over time, writers shift from affective or deontic attitude (e.g., obligation, imposition) toward epistemic attitude grounded in evidence and belief (Bascelli and Barbieri, 2002; Öztürk and Papafragou, 2015). Children often master the deontic stance before the epistemic stance, and these attitudes are closely linked to theory of mind (Shiro et al., 2019). In dialogic writing, 8- to 12-year-olds use epistemic stances to claim knowledge, assert equal access to information, and signal shared understanding (Herder et al., 2020); however, such stance-taking is more challenging in individual writing, which relies on internal linguistic, cognitive, and meta textual resources. (Aparici et al. 2021) showed in their analyses written analytical texts by Spanish learners' across primary, secondary, and university levels a clear developmental shift in discourse stance, moving away from personal and affective positioning toward greater use of epistemic and impersonal resources, which can be further reinforced with instructional work to strengthen these academic-language features.

Research by (Berman 2004), (Berman and Ravid 2009) and (Reilly et al. 2005) indicated that young school-age children tend to adopt a more monolithic and prescriptive stance in writing, expressing judgmental attitude through concrete and moral evaluations. Their use of attitude stance taking is primarily deontic, reflecting subjectively personalized or socially normative views rather than epistemic expressions of uncertainty or reflection. While even the youngest children show some ability to use personal and generic references, their stance remains relatively undifferentiated, lacking flexibility. In contrast, mature writers display greater rhetorical sophistication, considering multiple perspectives, engaging in conditional reasoning, and adopting more distanced, analytical positions.

At later ages, a study by (Figueroa Miralles 2018) analyzing 8th-grade students' argumentative essays identified distinct writer profiles: some effectively utilized academic language resources, including epistemic and impersonal stances, while others combined academic vocabulary with deontic markers, indicating a transitional phase in the development of discourse stance. The researchers concluded that students require more opportunities to practice constructing arguments and employing academic language to articulate viewpoints effectively. (Tolchinsky et al. 2023) investigated how Spanish students' analytical writing evolves across educational levels, focusing on their ability to assert standpoints and provide supporting evidence. The study identifies a developmental progression from texts containing unsupported opinions to those where reasons and backing evidence prevail, reflecting increasing sophistication in students' rhetorical choices influenced by both developmental and instructional factors.

In sum, school writing shifts from personal, deontic, or affective stances toward epistemic stances that signal knowledge, certainty, or possibility. This shift reflects social cognitive development, moving from subjectively personalized attitude to socially conditioned perspectives, and ultimately to abstract, distanced, and universal perspectives common in academic writing. However, this transition does not strictly divide between academic-cognitive attitudes and social-communicative attitudes. Instead, it highlights that mature speakers and writers can adopt multiple perspectives, integrate abstract theorizing while they express social values within the same discourse context. Discourse stance is generally linked to later stages of language development, yet little is known about its emergence in early elementary writing.

Argumentative writing provides a rich site for stance analysis, as it inherently requires the writer to articulate and justify a personal position on a given topic, with the intention of persuading a hypothetical or real reader. As such, this genre provides fertile ground for investigating how young writers express epistemic, affective, and evaluative positions through their linguistic and rhetorical choices. Despite the growing recognition of the importance of discourse stance in school and academic writing, empirical research on how Hebrew-speaking elementary school students express stance in writing remains scarce. To date, the only systematic investigation conducted in Hebrew has focused on 4th Grade students (Berman et al., 2002), meaning that no studies have examined the written discourse stance competence of younger school-age children in Hebrew within the Israeli context.

Despite the centrality of process-oriented theories of writing (Bereiter and Scardamalia, 1987; Hayes, 2012), most empirical studies of stance have examined it primarily as a product of written texts. Our study extends this view by analyzing discourse stance as a process-embedded resource, reflecting the recursive meaning-making that underlies children's argumentative writing. In this way, we aim to bridge product- and process-oriented perspectives, providing a more comprehensive account of how rhetorical competence develops across the elementary school years. The present study aimed to investigate the development of rhetorical competence inherent in the expression of stance-taking in argumentative text writing across elementary school grade levels.

1.1 Research questions

To chart how rhetorical competence is reflected in the deployment of discourse-stance (DS) dimensions and their categories in elementary students' argumentative texts develops across grades, we address the following research questions:

Research question 1 (dimension level): How do the three DS dimensions-orientation, attitude, and generality-vary by grade level?

Research question 2 (category level): Which of the nine DS categories (i.e., writer, text, audience in orientation; epistemic, deontic, emotional in attitude; and personal, generic, impersonal in generality) vary by grade level, and what are the trajectories (e.g., emergence, increase/decrease, plateau) of each category?

Research question 3 (association structure): Within each grade, to what extent do specific DS categories co-occur or trade off within the same texts, and does this association pattern change with grade level?

Three hypotheses concur with these research questions. First, we anticipated age-related consolidation in DS dimensions (research question 1). Second, we expected uneven developmental trajectories across stance categories without committing to specific category-by-category outcomes (research question 2). Third, we hypothesized that categories would form systematic within-grade bundles, with greater consolidation at higher grades (research question 3).

2 Methods

This study investigated the development of rhetorical competence in Hebrew-speaking elementary school children by analyzing their use of discourse stance markers in argumentative texts. Discourse stance encompassed three dimensions—orientation, attitude, and generality—each of which included three categories. We examined how these dimensions of rhetorical competence were manifested across grade levels.

2.1 Participants

We recruited 331 children in 2nd to 5th grade (age ranges for 2nd grade 7–8; for 3rd grade 8–9, for 4th grade 9–10, and for 5th grade 10–11 years old). Thirty eight children were excluded (Grade 2: 10; Grade 3: 9; Grade 4: 10; Grade 5: 9) based on predefined criteria, yielding a final analytic sample of 293 (Grade 2 = 68, Grade 3 = 70, Grade 4 = 65, Grade 5 = 90). The participants were 293 Hebrew-speaking schoolchildren (142 boys, 151 girls) from three public secular schools in middle- to high-SES areas in central Israel. Exclusions were as follows: 7 newcomers, 6 moved schools before study end, 6 declined participation, and 19 produced texts lacking a basic argumentative component (a claim). All included participants had written parental consent.

Participants attended schools that followed the writing instruction as delineated in the Israeli elementary school's National Literacy Curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2002). The curriculum outlined the teaching of various genres-including narrative, descriptive, informative, and argumentative texts-across both oral and written formats and encouraged their application in different discourse domains such as interpersonal, academic, and public communication. While discourse stance is not explicitly mentioned, related concepts-such as rhetorical flexibility, linguistic choices, and distancing devices-were implicitly embedded in curricular expectations. Each genre was characterized in the curriculum by distinct discourse features that reflect its communicative goals (e.g., narratives typically employed temporal sequencing, evaluative language, and personal reference to construct a story world; expository texts often relied on definitional statements and hierarchical organization, and argumentative texts foregrounded stance through explicit claims, logical connectors, and modal expressions that indicated degrees of certainty or obligation). However, the curriculum lacked developmental guidelines for the teaching of stance expressions. In practice, classroom instruction tended to emphasize structural features that were easier to model and assess-especially text organization-while discursive and interpersonal features, such as stance, received limited explicit attention. This was evident from an informal review of teacher-created instructional materials and Ministry-supported resources.

Although students were expected to encounter a variety of genres from the early grades, expository genres, such as argumentative writing, were generally taught more systematically only in the upper elementary grades. Thus, while younger students (e.g., in Grade 2) may have been exposed to basic argumentation, explicit instruction in stance-related functions tended to emerge primarily in Grades 4 and 5. Our selection of Grades 2 to 5 reflected this instructional progression and enabled us to examine how students begun to express discourse stance, even in the absence of direct teaching focused on this construct.

Recent amendments resulted in the development of a new language education curriculum that refined the existing framework by delineating developmental milestones. At present, this updated curriculum had been implemented solely for the transition from kindergarten to Grade 2, and its adoption in classrooms was in the preliminary stages. There remained a lack of clarity regarding how teachers nationwide would incorporate these changes into their instructional practices. It is important to note that these developments were recent and were not pertinent to the current study.

2.2 Data collection

2.2.1 Procedure

Each child produced an argumentative text on one of the following topics: (a) shortening the school week in exchange for longer study days, (b) introducing vending machines in schools, and (c) introducing a compulsory school uniform dress code. The writing prompts used in this study were adapted from pedagogical repositories commonly used in Israeli elementary language instruction and were designed to elicit argumentative texts in alignment with national curriculum expectations. These prompts had been consistently employed across several studies based on the same dataset (e.g., Stavans et al., 2020a, 2019; Seroussi et al., 2020b). The developmental appropriateness of the writing prompts and genre relevance were reviewed and approved by experienced literacy educators and researchers. No comprehension difficulties were reported during administration.

The time limit for the task was the class period (roughly 40 min), and the topics of the texts were assigned randomly, both of which were authentic and familiar to elementary school students. The instructions for the text production were (in free translation from Hebrew) as follows:

Now, I would like you to write me a text (essay) about:

a) ... running a long school day in exchange for no school on Fridays. You probably know that there is disagreement as to whether it is right to run a long school day throughout the week in return for no school on Friday.

b) …introducing vending machines selling sweets, snacks, and drinks in schools. You probably know that there is a debate about whether or not to install candy, snacks, and sweetened drinks vending machines in schools.

c) ...enforcing a dress code in the school where a uniform will be compulsory. You probably know that there are students who have different views on this matter of enforcing a school uniform.

The participants produced the argumentative text in the regular Hebrew lesson hour as an individual activity in the regular classroom, with the teacher physically present but not leading the activity, intervening to encourage the children to continue writing, revise their text, or providing any assistance. The task instructions were introduced by one of the researchers with whom the children were acquainted a priori. The writing production was entirely individual and handwritten (i.e., not typed), and no external support or feedback was provided during the task.

We collected texts in two contexts (in-class and one-on-one), but all analyses reported here use the in-class corpus. This restriction avoids confounds introduced by interactional support in one-on-one sessions (e.g., prompting, repair, turn-taking differences) and keeps task conditions comparable across students, so observed differences more cleanly reflect grade-related development in discourse stance rather than context effects. All descriptive and inferential statistics were recomputed on the in-class dataset.

2.3 Data scoring

All texts were transcribed orthographically exactly as the children wrote them, including their spelling and punctuation. The texts were segmented into clauses based on the framework provided by (Berman and Slobin 1994) and were analyzed for discourse stance dimensions, building upon the work of (Berman et al. 2002). For cross-linguistic comparability, text length was operationalized as the number of clauses per text (t-clause segmentation), rather than word count. We define a clause as a minimal predication with a predicate (verbal or non-verbal) and an overt or null subject, counting both coordinate and subordinate clauses. This definition explicitly includes Hebrew verbless (copular) clauses and subject-less clauses licensed by Hebrew syntax; coordinated clauses linked by ve- “and” are counted as separate clauses. In written Hebrew, high-frequency function morphemes (e.g., ha- “the”, ve- “and”, be- “in/at”, le- “to/for”, mi- “from”, ke- “as/like”, she- “that”) are prefixed to the following word; consequently, word counts are not commensurate with languages where these items are orthographically independent. Some Hebrew studies address this by caret-splitting such prefixes for counting; we do not retokenize in this way because our analyses are clause-based and our stance coding is performed per clause. Using clauses therefore provides a language-neutral structural unit that avoids Hebrew-specific tokenization artifacts and aligns the length metric with the unit of analysis for discourse stance.

Discourse stance was operationally defined through three interrelated dimensions: orientation, attitude, and generality. These dimensions were not mutually exclusive; rather, they interact dynamically within a discourse. They examine how writers position themselves in relation to their discourse, audience, and the content they convey. For a coarse overview we also report DS density (markings per clause), defined as the total number of DS category assignments divided by the total number of clauses at the grade level; DS density is descriptive only, whereas all inferential tests use per-text proportions.

Orientation pertains to the relational positioning between the writer (the sender) and the future reader (recipient). This dimension was categorized into three categories:

• Sender-oriented: the discourse centered on the speaker or writer's personal perspective, often utilizing first-person pronouns (e.g., “I think”, “In my opinion”, etc.).

• Recipient-oriented: the discourse directly addressed the audience, employing second-person pronouns or directives (e.g., “You should consider “,” you need to know”, etc.).

• Text (neutral) oriented. The focus shifted to the content or structure of the text itself, often using impersonal constructions or meta-discursive elements (e.g., “The following reasons explain why...”).

These orientations could alternate within a single discourse, reflecting a shift in focus and engagement strategies.

Attitude encompassed the writer's evaluative stance toward the content of the discourse. It is categorized as:

• Epistemic: expressed degrees of certainty, belief, or knowledge about the content (e.g., “It is known that...”, “I believe...”, etc.).

• Deontic: conveyed necessity, obligation, or permission (e.g., “One must...”, “You should...”, etc.).

• Emotional attitude: reflected emotional responses or feelings toward the content (e.g., “I am mad at...”, "I am happy that...”, etc.).

These attitudes significantly enhanced the persuasive and emotional impact of the message, allowing the audience to connect with it more meaningfully.

Generality addressed the specificity or general abstraction level in references within the discourse. It included:

• Personal references: mentioned specific individuals, events, or situations (e.g., “My friend Shahar insulted us”).

• Generic references: referred to classes or categories in a general sense (e.g., “Children often do not like...”).

• Impersonal references: utilized constructions that removed agency or specificity (e.g., “Grades are important at school...”).

The use of generality allowed writers to position their discourse along a continuum from personal to universal.

In the initial step of our analysis, we identified whether in each articulated clause there was any of the three DS dimensions: orientation, attitude, or generality. It is essential to note that these dimensions are not mutually exclusive and may co-occur within the same clause. Subsequently, we assigned exactly one DS category within each dimension identified in a clause. The three dimensions were operationalized as follows: orientation (writer, text, audience), Attitude (epistemic, deontic, emotional), and Generality (personal, generic, impersonal). A clause can realize one, two, or all three dimensions, but within any given dimension only a single category is coded. For instance, the clause “I think that …” would be coded as DS category: attitude- epistemic alongside orientation-sender. While each clause could have 1–3 DS dimensions (a maximal score of 3 on dimension) the characterizing category within a dimension could only be one of the three (a maximal score of 1 for category within a dimension).

Two independent raters double-coded 48 texts (16.3% of the corpus). Agreement was 89.6%. Cohen's κ = 0.73 (substantial). Because the categories were skewed (prevalence index = 0.48), we also report PABAK = 0.79. Discrepancies were adjudicated before analysis.

2.4 Data analysis/analytical strategy

We coded each text on three discourse-stance (DS) dimensions-orientation (writer, text, audience), attitude (epistemic, deontic, emotional), and generality (personal, generic, impersonal)—yielding nine proportion scores (0–1). Because these variables are bounded with frequent floor/ceiling values, we summarize M, SD, Mdn, and N, and use non-parametric inference.

Analyses were conducted at the level of the in-class text (one text per student), which served as the unit of analysis. Accordingly, research question 3 correlations are within-task, within-grade, between-subjects (one text per student). To provide context, we report a brief descriptive overview of total clauses and DS markers per grade (reported in Table 1 as DS density), but all inferential tests are based on individual texts and Table 1 is descriptive only (not used for hypothesis testing). This psychometric approach avoids the limitations of grade-level corpus aggregation and controls for differences in text length by using per-text proportions. For research questions 1and 2 (grade differences), the primary analyses were Kruskal-Wallis tests (α = 0.05) with Dunn-Holm pairwise comparisons where applicable. Effect sizes (ε2 for omnibus tests; r for pairwise contrasts) are reported alongside test statistics. To control multiplicity, we applied Benjamini-Hochberg FDR at the family level of each research question: research question 1 across the three dimension tests (k = 3), research question 2 across the nine category tests (k = 9), and research question 3 within each grade across the 36 pairwise correlations (k = 36) reporting unadjusted p and FDR-adjusted q. Reported statistics are H, p, q (FDR-adjusted), and ε2.

For research question 3 (within-grade structure), we estimated Spearman's ρ among the nine categories within each grade and applied BH-FDR within grade (36 pairs). In addition, ordinal logistic models were used for selected DS categories with skewed distributions, reporting odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

As a robustness check, we fit Welch one-way ANOVAs on arcsine-square-root-transformed proportions, reporting F(df1, df2), p, and ω2; results corroborated the non-parametric pattern (Supplementary Tables 4S, 5S). Analyses were run in Python (SciPy, statsmodels), and the research questions 1 and 2 Kruskal-Wallis tests were replicated in SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics 29). Outputs matched exactly, so only Python tables are reported.

3 Results

3.1 Overview of results

Before turning to the research questions, we provide a brief descriptive overview of grade-level productivity and the density of discourse stance (DS) marking (Table 1). Length is operationalized as clauses per text (t-clause segmentation). For each grade, Table 1 reports (a) per-text length descriptives (Mean, SD, Median, Min-Max), (b) the total number of clauses produced across all texts, (c) the total number of DS markings (sum of category assignments across the three DS dimensions), and (d) DS density is defined as Total DS markings divided by Total clauses. This format separates how much children write (productivity) from how densely they deploy stance within clauses.

For clarity, Table 1 is descriptive and is presented at the grade level. All inferential tests reported in Sections 3.1–3.3 are conducted at the text (participant) level. As expected, per-text clause counts tended to increase from Grade 2 to Grade 5, indicating longer texts in later grades. Crucially, the DS density appeared to remain around 2.8 markings per clause across grades (2.82, 2.81, 2.86, 2.78). Thus, developmental gains reflect greater productivity (more clauses per text) rather than a change in how densely stance is encoded within clauses. The following sections address the research questions in turn: research question 1 examines grade-level differences in the three DS dimensions (Orientation, Attitude, Generality); research question 2 turns to the nine DS categories; and research question 3 analyzes within-grade associations among these categories.

3.2 Development of DS dimensions (research question 1)

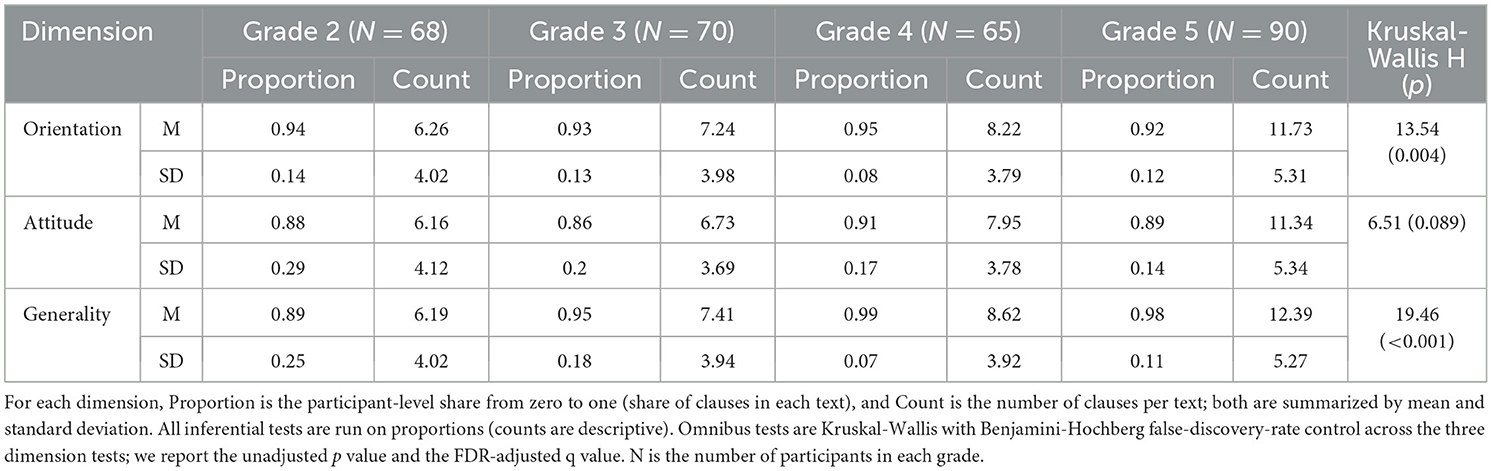

To address research question 1, we examined how rhetorical competence in children's argumentative texts was manifested across the three discourse stance (DS) dimensions— orientation, attitude, and generality. Research question 1 addressed Hypothesis 1, which predicted that the deployment of DS dimensions would increase across grade levels and diversify in nature. Table 2 reports participant-level proportions from zero to one and count-based productivity in clauses per text (both summarized by mean and standard deviation), together with Kruskal-Wallis tests across Grades 2 to 5. While Table 2 below relates to participant-level results, Table 2S in the Supplementary material complements this information by providing the relative weighting of the three dimensions within the stance system overall.

Table 2. DS dimensions by grade by participant-level proportions (0-1) and count productivity (clauses/text): Mean (SD); Kruskal-Wallis tests.

Counts index productivity in clauses per text and rise with grade, reflecting longer texts rather than denser stance. Although the inferential tests are rank-based (Kruskal Wallis), we report means in the narrative to highlight small fluctuations across grades; the table also reports standard deviations to reflect dispersion.

Orientation was already frequent from Grade 2 onward, with means consistently high across grades with little fluctuations (Grade 2 = 0.94, Grade 3 = 0.93, Grade 4 = 0.95, Grade 5 = 0.92). The omnibus Kruskal Wallis test was statistically significant, H(3) = 13.54, p = 0.004, but the effect size was small (ε2 = 0.04) and the mean differences were modest. Post hoc contrasts confirmed that the most reliable divergence was between Grades 2 and 5, reflecting the slight dip in Grade 5 relative to the earlier grades. Overall, orientation resources were well in place from the outset, with stability punctuated by minor fluctuations rather than a linear upward trend. Orientation counts increase with grade, from 6.26 clauses per text in Grade 2 to 11.73 in Grade 5.

Attitude, by contrast, remained stable and high throughout, with limited dispersion in Grade 2 M = 0.88 (SD = 0.29), Grade 3 M = 0.86 (SD = 0.20), Grade 4 M = 0.91 (SD = 0.17), Grade 5 M = 0.89 (SD = 0.14). The Kruskal Wallis was not significant, H(3) = 6.51, p = 0.089, ε2 = 0.01, indicating no systematic developmental change in average attitude use. This stability suggests that, within the present task, attitude marking was broadly available across grades and may be shaped more by task or communicative demands than by age. Attitude counts also increase with grade, from 6.16 to 11.34 clauses per text, consistent with longer texts.

Generality showed the most consistent increase in means, from Grade 2 M = 0.89 (SD = 0.25) to Grade 3 M = 0.95 (SD = 0.18) to Grade 4 M = 0.99 (SD = 0.07), remaining high at Grade 5 M = 0.98 (SD = 0.11). The omnibus Kruskal Wallis was statistically significant, H(3) = 19.46, p < 0.001, with a small to moderate effect (ε2 = 0.06), consistent with a progressive consolidation of generality stance with age. The narrowing SDs by Grades 4 and 5 point to greater consistency of use as average generality increases toward ceiling. Taken together, the pattern is consistent with a consolidation of decontextualized, abstract argumentation by mid-elementary school. Generality counts show the same pattern, from 6.19 to 12.39 clauses per text, rising steadily and then leveling high.

Standard deviations for counts are sizable in several cells, indicating meaningful individual differences within grades.

In all, the results show an uneven developmental pattern: orientation remains high with small fluctuations across grades; attitude remains stable; and generality shows a steady increase in means from Grade 2 to Grades 4 and 5 before plateauing. Building on these dimension-level findings, Section 3.2 examines the nine stance categories to show how these patterns are realized in writer, text, audience; epistemic, deontic, emotional; and personal, generic, general choices.

3.3 Development of DS categories (research question 2)

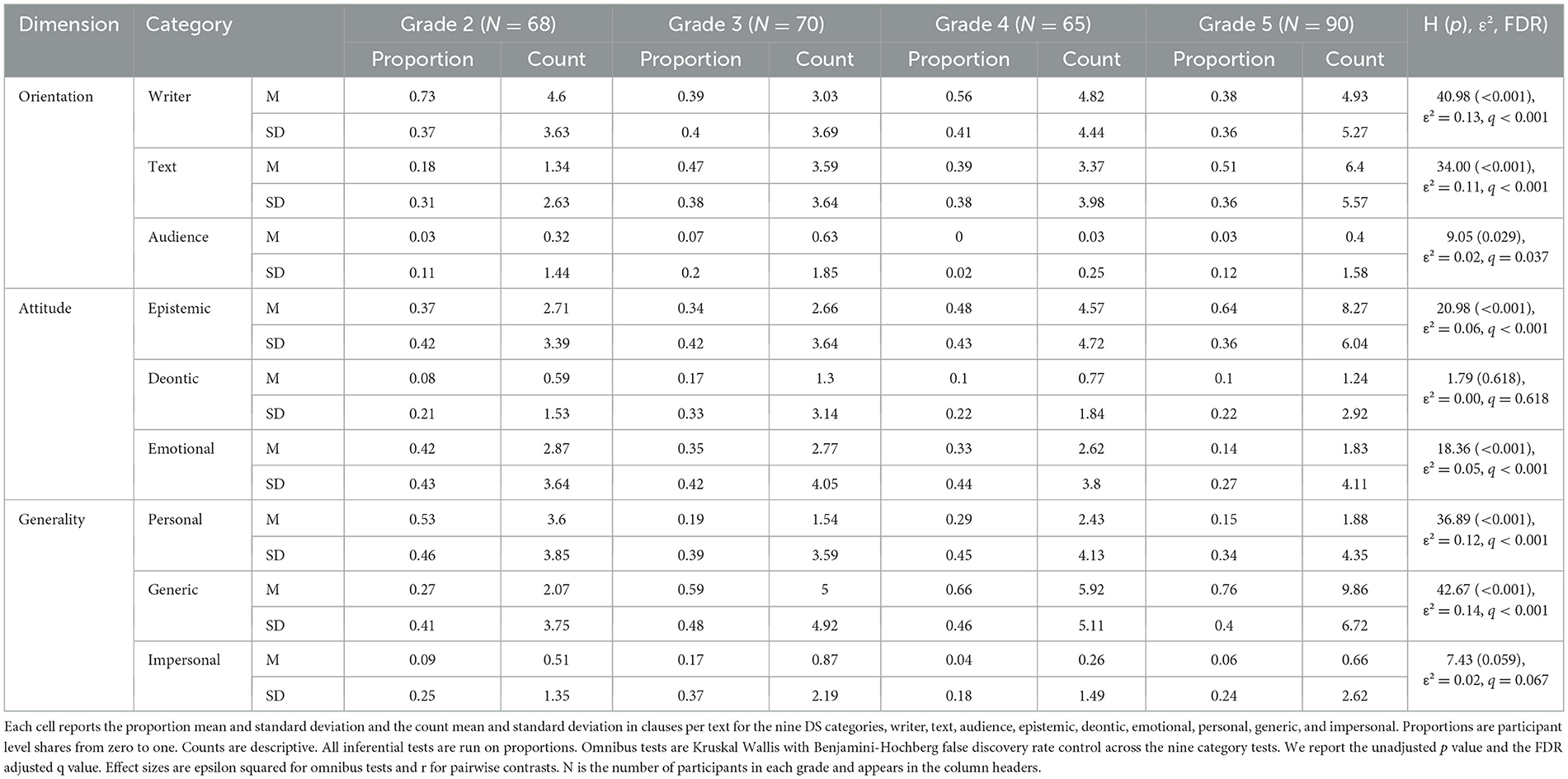

To address research question 2, we analyzed how each of the nine discourse stance (DS) categories was used across Grades 2 to 5. Research question 2 corresponds to Hypothesis 2, which anticipated distinct developmental trajectories for individual stance categories (for instance, increases in text orientation, epistemic stance, and generic generality, and decreases in personal and emotional stance). Specifically, we examined the categories nested within the three dimensions: orientation (writer, text, audience), attitude (epistemic, deontic, emotional), and generality (personal, generic, impersonal). Table 3 presents participant-level proportions and count-based productivity in clauses per text, both summarized by mean and standard deviation, alongside Kruskal Wallis omnibus tests, effect sizes, and FDR-adjusted p values for each category. While Table 3 reports participant-level results, Supplementary Table 3S complements this information by providing clause-level counts and percentage shares for each stance category within grade. Counts mix two processes. They reflect how much a student writes and which stance category the student chooses. Proportions hold text length constant by using clauses as the denominator, so they tell us how writers allocate stance within their texts. In our data, mean counts are often smaller than their standard deviations, which signals high dispersion driven by large differences in text length and many zero values. This makes counts noisy and can blur the profile of stance written expression. Proportions provide a stable, comparable scale across grades, they isolate choice rather than productivity, and they are the basis for our inference. Counts remain in the tables to give context about productivity, but the developmental story is best read from the proportion values.

Table 3. DS categories by grade by participant-level proportions (0–1) and count productivity (clauses/text): mean (SD); Kruskal-Wallis tests.

Looking more closely at the nine stance categories (Table 3) reveals how children's rhetorical profiles evolve in uneven but meaningful ways. The category-level analyses present sharper developmental contrasts than those observed at the dimension level. Counts rise mainly because texts get longer, so category profiles are best interpreted from proportions.

Within the orientation dimension, Grade-2 students leaned heavily on the writer-oriented stance. For many, this was the default. Nearly every text contained such references and the mean use was high in Grade 2 (M = 0.73). Reliance on this resource did not decline monotonically. It fell sharply from Grade 2 to Grade 3 (M = 0.39), rebounded in Grade 4 (M = 0.56), and dipped again by Grade 5 (M = 0.38). The change was robust, H(3) = 40.98, p < 0.001, ε2 = 0.13, with FDR-adjusted Dunn post-hoc tests showing Grade 2 significantly higher than Grades 3 to 5. What replaces it is text orientation. Initially rare (Grade 2: M = 0.18), it increased to become the dominant resource by Grade 5 (M = 0.51), H(3) = 34.00, p < 0.001, ε2 = 0.11, reflecting a shift toward framing claims in relation to textual content rather than the self. Audience orientation, by contrast, remained marginal (M ≤ 0.07), though a small effect emerged, H(3) = 9.05, p = 0.029, ε2 = 0.02, largely due to a brief uptick in Grade 3. In short, stance moves from egocentric positioning to text-based reasoning, while audience-direct address is still largely absent in elementary writing. This movement away from self-anchored positioning is mirrored in how children manage evaluative stance.

The attitude dimension showed a similar rebalancing of resources. Epistemic stance-the language of knowledge and evidence-was modest in Grade 2 (M = 0.37) but rose steadily across grades, reaching M = 0.64 by Grade 5, H(3) = 20.98, p < 0.001, ε2 =.06. In parallel, emotional stance, which was quite frequent in Grade 2 (M = 0.42) declined sharply by Grade 5 (M = 0.14), H(3) = 18.36, p < 0.001, ε2 = 0.05. Deontic stance remained infrequent and showed no developmental trend (M ≤ 0.17; H(3) = 1.79, p = 0.618). In all, these shifts indicate a rebalancing from affective to epistemic grounding in argumentation, with obligation-style wording playing little role at this age.

The generality dimension captured perhaps the starkest transformation. Personal generality, common in Grade 2 (M = 0.53), faded as students advanced, falling to M = 0.15 by Grade 5, H(3) = 36.89, p < 0.001, ε2 =.12. At the same time, generic generality surged as it was rare at the outset in Grade 2 (M = 0.27) but increased markedly by Grade 3 (M = 0.59) through Grades 4 and 5 (M = 0.66 and 0.76, respectively), H(3) = 42.67, p < 0.001, ε2 =.14, the strongest developmental gain of any category. Impersonal references were consistently low (M ≤ 0.17) and showed only a marginal trend, H(3) = 7.43, p = 0.059, ε2 = 0.02. In practical terms, children move from “I/my friend…” to kind-level claims about “kids/people/everyone” by Grade 3 and sustain this abstraction thereafter.

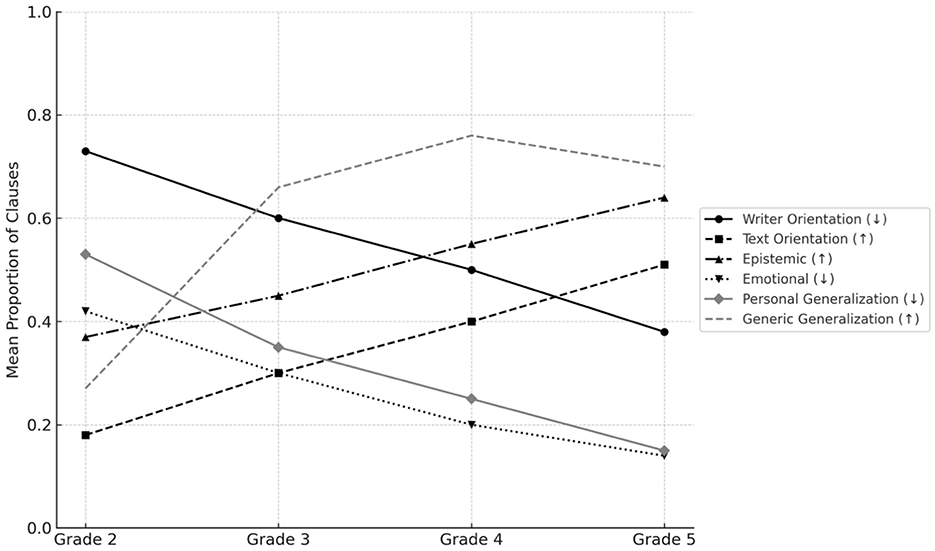

In summary, the category-level findings sketch a clear developmental story. Second graders often anchor arguments in the self through writer orientation, personal generality, and emotional stance, whereas by Grade 5 they increasingly rely on text-based positioning, generic formulations, and epistemic reasoning. The sharpest inflection points occur early, between Grades 2 and 3 when generic generality and text orientation surge, and again later, between Grades 4 and 5 when epistemic stance consolidates. These results broadly support Hypothesis 2: that DS categories would show distinct developmental trajectories across grade levels, with text orientation, epistemic stance, and generic generality increasing with grade, while personal and emotional stance declined; deontic stance showed no growth. Table 3 provides the exact values, and Figure 1 visualizes the contrasting trajectories (early rise in generic generality; gradual consolidation of epistemic stance). Building on these category-level patterns, Section 3.3 examines how the categories co-occur within grade to form coherent stance profiles.

Detailed descriptive statistics and Kruskal-Wallis tests for each category appear in Table 3. Figure 1 complements those results by showing the developmental trajectories—most notably the sharp Grade-2 to Grade-3 rise in Generic generality and Text orientation, and the continued consolidation of Epistemic stance through Grades 4–5. Together, Table 3 and Figure 1 provide a fuller account of category-level change than either alone.

The lines in this figure show means of participant-level proportions. Writer orientation, Personal generality, and Emotional stance decline with grade, while Text orientation, Generic generality, and Epistemic stance increase. The steepest shifts occur between Grades 2 and 3 (Text and Generic rise), and Epistemic continues to strengthen from Grades 4 to 5. Audience and Deontic remain low and change little. These trajectories align with Hypothesis 2, indicating a move from self-anchored, affective stance in younger writers toward a text-anchored, impersonal, and epistemically grounded stance in later grades.

3.4 Relations among discourse stance categories within grade level (research question 3)

The frequency analyses in research questions 1 and 2 clarified which stance resources increase, decrease, or remain stable across development. To address research question 3, within the same writing task we examined between-student associations among per-text DS proportions within each grade, asking whether categories cluster into systematic bundles and how such structure changes developmentally. We therefore computed pairwise Spearman rank correlations (ρ) among the nine discourse-stance (DS) categories within each grade (36 pairs per grade). Analyses use participant-level proportions (one text per student), which control for text-length differences across grades. In practice, within each grade we asked whether students who used more of one category also tended to use more (or less) of another across students (e.g., in Grade 2, whether greater text-orientation accompanied greater epistemic stance). These associations represent co-use tendencies rather than causal dependencies; they map the grade-by-grade structure of stance written expression. Multiple comparisons were controlled with Benjamini-Hochberg FDR within grade.

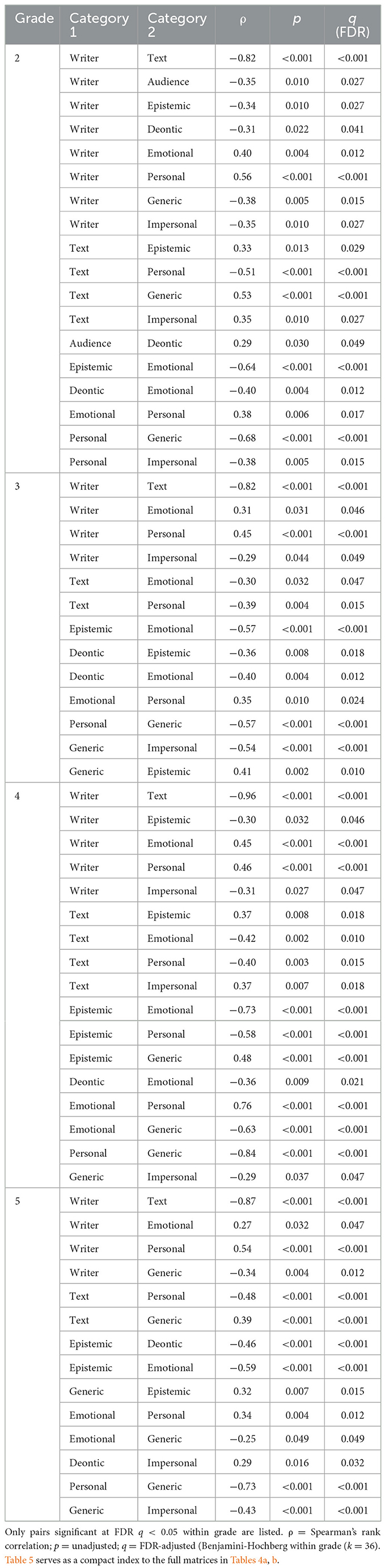

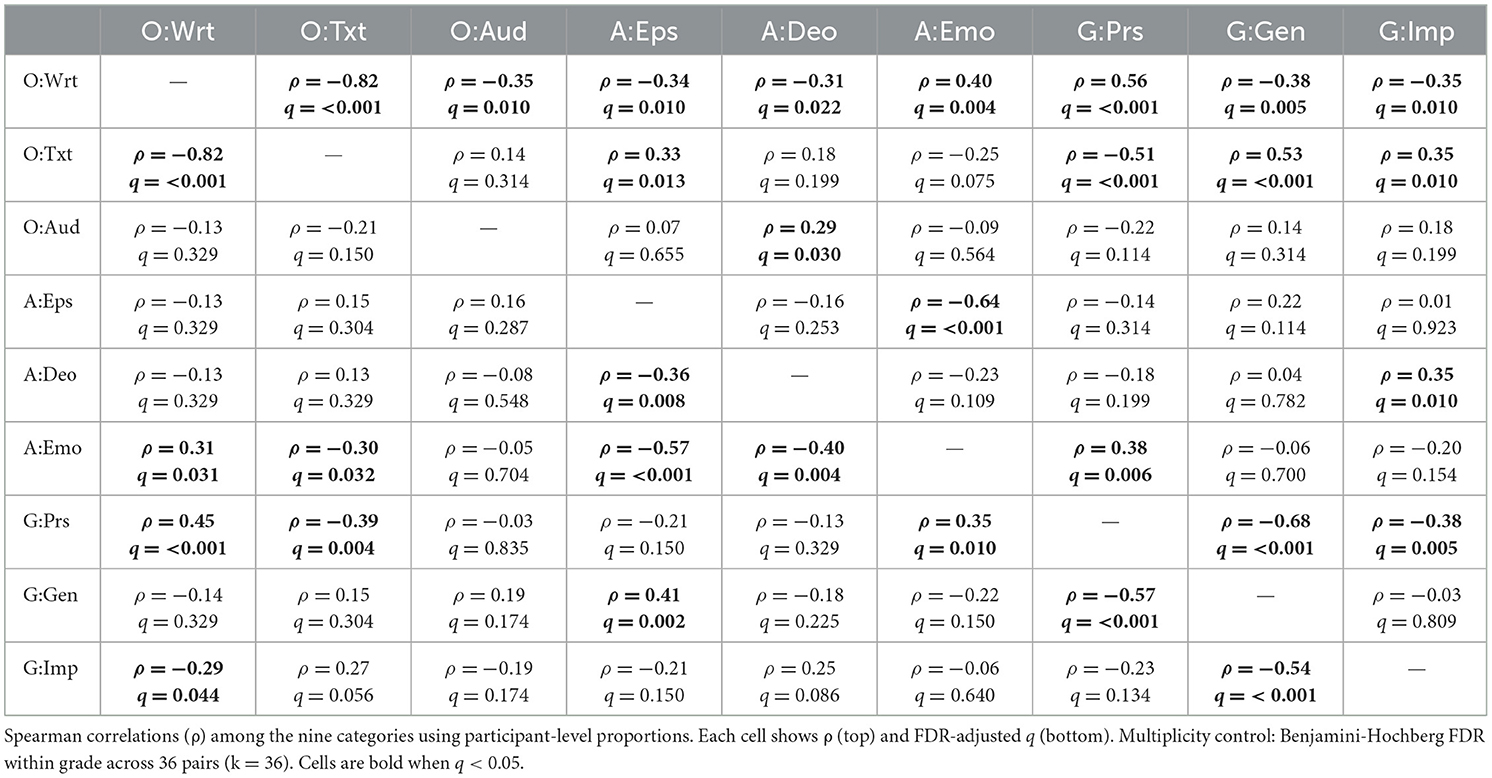

We controlled multiplicity with Benjamini-Hochberg FDR within grade (k = 36) and report ρ together with FDR-adjusted q; cells with q < 0.05 are interpreted as reliable. The complete Tables 4a, b present the full 9 × 9 matrices (in Supplementary Tables; Grade 2 above/Grade 3 below in Table 4a; Grade 4 above/Grade 5 below in Table 4b). Table 5 lists only the FDR-significant associations reported across Grades 2–5. This summary highlights the contrasts between the early writer-personal-emotional cluster and the later text-generic-epistemic cluster, complementing the full correlation matrices in Tables 4a, b (see Supplementary Tables). Within-dimension associations are especially robust for orientation (writer vs. text) and generality (personal vs. generic), while cross-dimension associations include the alignment of emotional stance with personal generality and the tie between text orientation and generic generality. Because Table 5 mixes within- and cross-dimension links, we interpret these classes separately in the narrative.

Table 4a. Spearman correlations among DS categories stratified by grade level for Grade 2 (above diagonal, N = 68) and Grade 3 (below diagonal, N = 70).

Table 4b. Spearman correlations among DS categories stratified by grade level for Grade 4 (above diagonal, N = 65) and Grade 5 (below diagonal, N = 90).

The findings shows that in Grade 2, writer orientation is prevalent (M = 0.73). Orientation patterns point to a largely self-anchored stance whereby writer and text are strongly and inversely related (ρ = −0.82, q < 0.001), and writer is modestly inversely related to audience (ρ = – 0.35, q = 0.010). This suggests that when children ground arguments in the self, they rarely anchor them in the neutral text or address the reader directly. By contrast, text and audience are not reliably associated (q = 0.314), suggesting that anchoring arguments in the text orientation does not yet go hand-in-hand with addressing the reader. In the attitude dimension, epistemic and emotional are strongly and inversely related (ρ = −0.64, q < 0.001), meaning that when children ground claims in knowledge or experience, they tend not to rely on affective language, while deontic shows no reliable links (all q ≥ 0.05), indicating that prescriptive wording is rare at this grade and not yet coordinated with evidential or emotional stance. In the generality dimension, personal and generic are strongly and inversely related (ρ = – 0.68, q < 0.001). Impersonal is negatively related to personal (ρ = −0.38, q = 0.005) but shows no reliable link with generic (q = 0.809), suggesting that broad, population-wide assertions are beginning to separate from self-anchored talk but are not yet coordinated with kind-level generalizations.

In looking at cross-categories links in Grade 2, two configurations are immediately visible. When children make generic, kind-level claims, they also tend to anchor arguments in text orientation (text-generic, ρ = 0.53, q < 0.001). And when the tone turns affective, it usually travels with self-anchored statements (emotional-personal, ρ = 0.38, q = 0.006). Beyond these headline pairings, the pattern resolves into two contrasting bundles. A writer-centered profile brings personal and emotional resources with it (writer-personal, ρ = 0.56, q < 0.001; writer-emotional, ρ = 0.40, q = 0.004) and moves away from epistemic, deontic, generic, and impersonal resources (writer with epistemic, ρ = −0.34, q = 0.010; with deontic, ρ = −0.31, q = 0.022; with generic, ρ = −0.38, q = 0.005; with impersonal, ρ = −0.35, q = 0.010). The text orientation-based profile shows the complementary shape because it pairs with epistemic, generic, and impersonal resources and pulls away from personal (text with epistemic, ρ = 0.33, q = 0.013; with generic, ρ = 0.53, q < 0.001; with impersonal, ρ = 0.35, q = 0.010; with personal, ρ = −0.51, q < 0.001). Audience plays only a minor role here. It links weakly to deontic (ρ = 0.29, q = 0.030), and text-audience is not reliable (q = 0.314).

What emerges is that Grade 2 stance-taking in argumentative texts coalesces around a writer-personal-emotional profile, with a less frequent text-generic-epistemic alternative, while deontic and impersonal resources remain marginal and unintegrated at this stage.

In Grade 3 (lower triangle), as in Grade 2, writer and text orientation were again strongly and inversely related (Spearman's ρ = −0.82, q < 0.001), whereas audience orientation still sits on the sidelines, showing no reliable links with writer or text orientation (q = 0.329, 0.150). This pattern suggests that by Grade 3 students treat self-based and text-based positioning as alternative choices rather than complementary ones, while audience-directed stance is still peripheral and not integrated with the other resources. Within the attitude dimension, a clear rebalancing emerges. Epistemic and emotional move in opposite directions (ρ = −0.57, q < 0.001), supporting the idea that evidence-based framing tends to come at the expense of affective language. Deontic remains infrequent on average, but when it appears it functions as an alternative rather than a companion because it correlates negatively with epistemic (ρ = −0.36, q = 0.008) and with emotional (ρ = −0.40, q = 0.004). In short, prescriptive wording typically replaces both evidential appeals and affective coloring, rather than being layered on top of them. Within the generality dimension, the shift away from self-anchored claims is clear. Personal and generic stance are inversely associated (ρ = −0.57, q < 0.001), which fits a move from “I/my friend…” toward kind-level statements such as “students,” “children,” or “people”. At the same time, children begin to separate generic from impersonal. The generic-impersonal stance is negatively associated (ρ = −0.54, q < 0.001), signaling that students distinguish generic, kind-level statements (e.g., “kids need…”) from sweeping population-wide assertions (e.g., “everyone,” “always”). Personal-impersonal is not reliable (q = 0.134), which fits the view that impersonal claims are a distinct and infrequent option rather than just a stronger form of generic wording. No other links within the generality categories are reliable (all q ≥ 0.05), so the structure at Grade 3 is still driven mainly by the personal-generic trade-off.

Cross-category links in Grade 3 were selective and informative. A writer-centered bundle is visible. Writer aligns with personal (ρ = 0.45, q < 0.001) and with emotional (ρ = 0.31, q = 0.031), and it pulls away from impersonal (ρ = −0.29, q = 0.044). The text-based profile shows the complementary shape. Higher text is associated with lower personal (ρ = −0.39, q = 0.004) and lower emotional (ρ = −0.30, q = 0.032). The evidential route consolidates as generic co-occurs with epistemic (ρ = 0.41, q = 0.002). The affective route also remains in play since emotional co-occurs with personal (ρ = 0.35, q = 0.010). Audience offers little connective tissue at this grade, and its small link with deontic from Grade 2 is not reliable here (q = 0.548). All remaining cross-category associations are small and do not survive FDR (q ≥ 0.05). Taken together, these links suggest that co-use is guided by two competing logics: self-anchored vs. text-anchored, so categories tend to cluster within rather than acros those logics at this stage.

What emerges from these findings is that Grade-3 texts sort into two recognizable profiles, a writer-personal-emotional profile and a text-leaning pathway that couples generic with epistemic, while audience and deontic remain peripheral. Relative to Grade 2, Grade 3 shows a clear redistribution of stance. Writer drops from M = 0.73 in Grade 2 to M = 0.39 in Grade 3, while text rises from M = 0.18 in Grade 2 to M = 0.47 in Grade 3. Personal stance marking falls from M = 0.53 in Grade 2 to M = 0.19 in Grade 3, as generic stance increases from M = 0.27 to M = 0.59, respectively. Emotional attitude is lower on average, moving from M = 0.42 in Grade 2 to M = 0.35 in Grade 3, and deontic remains infrequent (means ≤ 0.17) or below. Together with the Grade-3 correlations, this shift marks a move away from a writer-personal-emotional profile toward a text-leaning route that increasingly pairs generic with epistemic, while audience and deontic remain peripheral.

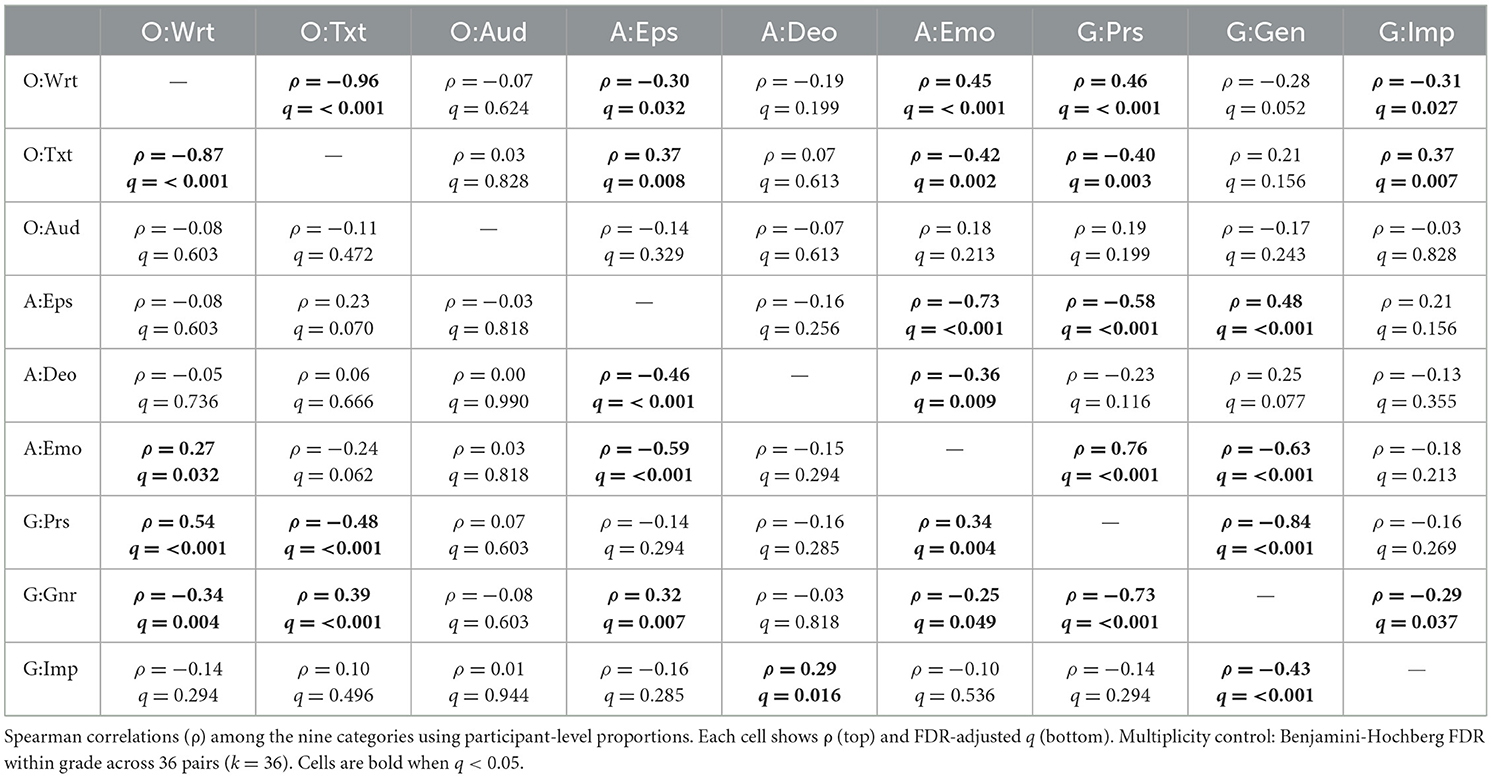

The findings also indicate that in Grade 4, writer orientation and text orientation were very strongly and inversely related (Spearman's ρ = −0.96, q < 0.001), suggesting that texts that leaned more on the writer's perspective tended to be less text-anchored, and vice versa. Audience orientation did not relate reliably to writer (q = 0.624) or to text (q = 0.613) after FDR adjustment. As for attitude, epistemic standpoint was negatively related to emotional standpoint (ρ = −0.73, q < 0.001). In addition, writer orientation decreased as epistemic stance increased (ρ = −0.30, q = 0.032), suggesting that evidential framing pulls writers away from self-anchored positioning, while affect draws them back to it. By contrast, text orientation showed the complementary shape, higher with epistemic (ρ = 0.37, q = 0.008) and lower with emotional (ρ = −0.42, q = 0.002). Deontic was lower when emotional was higher (ρ = −0.36, q = 0.009). These findings suggest that by Grade 4 students link evidence with text and emotion with writer, while deontic stays marginal and tends to replace emotion rather than accompany it. Within the generality dimension, personal and generic are strongly and inversely related (ρ = −0.84, q < 0.001), indicating that self-anchored claims and kind-level generality seldom appear together in the same text. Generic also contrasts with impersonal (ρ = −0.29, q = 0.037), signaling a growing distinction between kind-level statements (e.g., “children”) and sweeping population-wide assertions (e.g., “everyone”). No other within-generality links are significant (all q ≥ 0.05). Hence, Grade 4 generality choices are organized around the personal-generic trade-off, with impersonal treated as a distinct, infrequent option.

Cross-category associations in Grade 4 sketch two magnetic poles, but the figures anchor the story. On the writer-anchored side, emotional rises with personal (ρ = 0.76, q < 0.001), writer goes hand in hand with emotional (ρ = 0.45, q < 0.001) and with personal (ρ = 0.46, q < 0.001), and writer steps away from impersonal (ρ = −0.31, q = 0.027). On the text-leaning side, text pairs with epistemic (ρ = 0.37, q = 0.008) and recedes when emotional is higher (ρ = −0.42, q = 0.002) or personal is higher (ρ = −0.40, q = 0.003). Generic aligns with epistemic (ρ = 0.48, q < 0.001) and pulls against emotional (ρ = −0.63, q < 0.001), while text shows a modest link with impersonal (ρ = 0.37, q = 0.007). No additional links met the FDR-corrected threshold. Overall, Grade 4 shows two coordinated pathways: writer with personal and emotional, and text with generic and epistemic, while impersonal tilts to the text path and audience and deontic stay peripheral.

What emerges from these findings is that Grade 4 texts sort into two coordinated profiles. One profile centers on the writer, personal stance, and emotional language. The other brings together text orientation, generic generality, and epistemic stance, with impersonal beginning to align with this text-anchored pathway. Audience and deontic remain largely peripheral. Relative to Grade 3, Grade 4 shows a clearer and tighter organization. The opposition between writer and text strengthens from ρ = −0.82 in Grade 3 to ρ = −0.96 in Grade 4. The pairing of generic with epistemic stance becomes stronger from ρ = 0.41 to ρ = 0.48, respectively; and a new association appears between text and impersonal with ρ = 0.37 and q = 0.007. On the writer side, the association of emotional with personal increases from ρ = 0.35 in Grade 3 to ρ = 0.76 in Grade 4, and text separates further from emotional from ρ = −0.30 to ρ = −0.42, respectively. Deontic remains marginal, tending to decline when emotional stance increases (ρ = −0.36, q = 0.009). Together these changes mark a developmental step from the looser Grade 3 pattern toward a more systematically organized stance system in Grade 4.

The findings of Grade 5 showed that writer orientation and text orientation were strongly and inversely related (Spearman's ρ = −0.87, q < 0.001). In plain terms, texts that leaned on the writer's own perspective tended not to be text-anchored, and texts that anchored arguments in the text tended not to foreground writer orientation. Similar to most other grade levels so far, audience orientation did not associate reliably with either writer or text orientation after FDR adjustment (q = 0.603, 0.472), suggesting that the arguments did not address the reader directly in a way systematically coordinated with these other orientation categories. In terms of the attitude dimension in stance-taking, the epistemic attitude was negatively related to the emotional one (ρ = −0.59, q < 0.001) and was also negatively related to deontic attitude (ρ = −0.46, q < 0.001). Practically, when students framed their arguments in terms of what is known, shown, or can be justified, they were less likely to use affective language or prescriptive evaluations. This pattern points to a more evidential approach to argumentation in Grade 5. As for the generality dimension, personal and generic categories were strongly and inversely related (ρ = −0.73, q < 0.001), consistent with a move away from self-anchored claims when generic formulations were made. Moreover, generic contrasted with impersonal generality (ρ = −0.43, q < 0.001), indicating that students differentiate between generic statements (e.g., “children need…”) and broad, sweeping assertions (e.g., “everyone,” “always”). No other within-generality associations are significant after FDR (e.g., personal-impersonal q = 0.294).

Across categories, several associations remained after FDR adjustment. Text orientation is positively associated with generic generality (ρ = 0.39, q < 0.001), and generic co-occurs with epistemic (ρ = 0.32, q = 0.007). Writer aligns with personal (ρ = 0.54, q < 0.001) and with emotional (ρ = 0.27, q = 0.032), text is lower when personal is higher (ρ = −0.48, q < 0.001), writer is lower when generic is higher (ρ = −0.34, q = 0.004), emotional co-occurs with personal (ρ = 0.34, q = 0.004), and deontic shows a modest positive link with impersonal (ρ = 0.29, q = 0.016). All other cross-dimension associations are small and do not survive FDR (e.g., text-emotional q = 0.062).

By Grade 5 the stance system crystallizes into two stable profiles. One profile centers on writer, personal, and emotional resources, reflected in reliable co-use of writer with personal (ρ = 0.54, q < 0.001) and writer with emotional (ρ = 0.27, q = 0.032), alongside the personal-emotional link (ρ = 0.34, q = 0.004). The other profile is text anchored, generalized, and evidential: text aligns with generic (ρ = 0.39, q < 0.001) and generic aligns with epistemic (ρ = 0.32, q = 0.007), while text is lower when personal is higher (ρ = −0.48, q < 0.001) and writer is lower when generic is higher (ρ = −0.34, q = 0.004). Deontic remains peripheral but shows a modest tie with impersonal (ρ = 0.29, q = 0.016). Audience continues to be peripheral, with no reliable links to writer or text (q = 0.603, 0.472). Taken together, Grade 5 writing shows children choosing between two coordinated routes rather than blending them, with the text, generic, and epistemic pathway clearly predominant. Compared to Grade 4, Grade 5 keeps the two-profile structure but completes the text-generic-epistemic cluster and strengthens several cross-profile separations, marking a more fully crystallized, text-anchored rhetorical option by the end of elementary school.

What transpires from Table 5 summary of the FDR-significant associations within each grade is an uneven distribution. Grade 2, with 18 associations, and Grade 4, with 17 associations, form dense networks. Grade 5, with 14 significant associations, remains highly connected, suggesting a streamlined rather than weakened structure by the end of elementary school. Grade 3, with 12 associations, is sparser and consistent with a transitional stage. The most stable within-dimension contrasts that recur across grades are writer vs. text, personal vs. generic, and epistemic vs. emotional, with an additional epistemic vs. deontic contrast emerging by Grades 4 and 5. Cross-dimension associations-for example, text with generic, emotional with personal, and text with epistemic-are already visible in Grade 2, thin out in Grade 3, and become more coordinated by Grades 4 and 5. Read alongside Tables 4a, b, the pattern shows a shift from early writer-personal-emotional profiles toward a text-generic-epistemic profile in the upper grades.

Across grades, stance reorganizes from a Grade 2 mix of writer-personal-emotional and text-generic profiles, through a sparse Grade 3 transition, to a Grade 4 consolidation and a Grade 5 endpoint where the text-generic-epistemic profile predominates and audience/deontic stay peripheral.

Considered alongside research question 1 and 2, the research question 3 findings give a structural view of how stance is organized within grade. Research question 1 showed broad gains most clearly in Generality, and research question 2 traced the category shifts—from writer to text orientation, from personal to generic, and from emotional to epistemic. Research question 3 adds that these categories increasingly travel together in coherent profiles. Early in development, children's arguments tend to combine writer orientation, personal generality, and emotional stance; by the upper grades, texts consolidate around text orientation, generic generality, and epistemic stance. Grades 3 and 4 function as a hinge: both profiles are present, and their differentiation sharpens. Taken together, the three analyses trace a movement from self-anchored, affective positioning toward more text-anchored, impersonal, and epistemically grounded stance in Hebrew elementary-school writing. By Grade 5, the text-generic-epistemic profile predominates and the writer-personal-emotional profile recedes, consistent with Hypothesis 3.

4 Discussion

4.1 Overview of findings

This study examined how Hebrew-speaking children in Grades two to five deploy discourse stance in argumentative writing. Three broad findings stand out. First, the three stance dimensions do not move in lockstep. Generality shows clear growth across grades. Orientation is already frequent and changes only slightly. Attitude is essentially stable at the dimension level. Under that surface stability, however, the attitude categories redistribute with age. Epistemic use increases, emotional use decreases, and deontic remains sparse. Second, when we look at the nine categories, a rebalancing of resources becomes clear. In the early grades children lean on writer orientation, emotional stance, and personal generality. In the later grades they draw more on text orientation, epistemic stance, and generic generality. Impersonal remains comparatively rare throughout. Third, the pattern of associations shows that stance choices cohere into recognizable profiles that become more organized with age. In the younger grades, children tend to combine writer, personal, and emotional resources. By the end of elementary school, texts more often bring together text orientation, generic generality, and epistemic stance. The middle grades function as a hinge where both profiles are present and begin to sort. Taken together, development involves two intertwined changes. Children adjust how often they use particular stance resources, and they also learn to combine those resources in more coordinated ways.

4.2 Developmental trajectories of stance dimensions (research question 1)

The results reveal uneven growth across the three DS dimensions. Generality exhibits the sharpest change. Generic formulations surge by Grade 3 and remain high thereafter, signaling an early shift toward abstract, decontextualized, and more impersonal ways of stating claims. Orientation is already frequent from Grade 2 and shows only small fluctuations overall, with the developmental signal reflecting a redistribution from writer-anchored to text-anchored positioning. By contrast, attitude appears broadly stable across grades at the dimension level.

This pattern is theoretically coherent. The growth in text-anchored orientation reflects a gradual decentering from egocentric positioning toward genre-appropriate referencing practices, drawing explicitly on what “the text says” or what “the writer shows.” Such movement accords with accounts of academic writing development as a shift from personal narration to source-mediated argument (Berman and Nir-Sagiv, 2010; Uccelli et al., 2013). It likely rides on gains in reading comprehension and genre knowledge: children get better at identifying relevant textual evidence and at using it rhetorically, even though audience orientation remains comparatively rare at this age.

The leap in generality, from personal to generic claims, points to growing conceptual and linguistic control over category-based statements (“children need…,” “people tend to…”). These formulations invite readers to treat an assertion as broadly applicable rather than episodic, and they are central in school-valued reasoning. The fact that this shift is already evident by mid-elementary grades suggests that when tasks invite argumentative generality, young writers can mobilize the lexical and clause-level resources needed to express it.

The apparent stability of attitude at the dimension level masks a meaningful rebalancing at the category level (research question 2): epistemic marking gradually expands while emotional marking recedes, and deontic remains sparse. In other words, children do not simply express “more attitude” with age; they redistribute how stance is realized—from feeling-laden to knowledge-based justifications. The lack of a strong grade effect for the attitude dimension therefore reflects offsetting trends within it rather than developmental stasis and is consistent with the idea that evaluative resources are available early but deployed in task-sensitive ways.

Finally, because all inferential tests were conducted at the text level (one text per student), these trajectories index changes in stance selection rather than mere increases in verbosity. Hence, the findings portray development not as a uniform accumulation of stance devices but as a coordinated shift toward text-anchored and generic argumentation, with evaluative language progressively reframed in epistemic terms.

4.3 Shifts in stance categories (research question 2)

At the category level, the developmental story comes into sharp focus. Within orientation, writer references are the default in Grade 2 and then recede, while text orientation gains ground and becomes the preferred anchor by Grade 5. This shift from writer to text orientation suggests that students increasingly anchor their arguments in the textual space itself rather than in personal voice, marking a move toward more rhetorically conventional forms of argumentative writing (Berman and Nir-Sagiv, 2010; Uccelli et al., 2013). Audience orientation, by contrast, remains rare across grades and does not integrate reliably with the other resources. That scarcity is unsurprising: crafting an argument with a reader explicitly in view is a late-emerging skill, and elementary-school writers often struggle to coordinate content and audience design simultaneously (Nippold et al., 2005). In our data, then, children first learn to re-anchor claims in textual evidence; direct engagement with the reader is not yet the lever they routinely pull. Direct engagement with the reader is not yet the lever they routinely pull.

The attitude cluster shows a complementary rebalancing. Epistemic stance—talking in terms of what is known, shown, or can be justified—steadily increases, while emotional stance declines. The result is a gradual tilt from “feeling” toward “knowing,” consistent with accounts of growing control over academic evaluative language and justification (Figueroa Miralles, 2018; Shiro et al., 2019; Uccelli et al., 2013;). Deontic stance remains sparse and inconsistently coordinated with the other categories, which fits the difficulty of sustaining prescriptive evaluation in early writing and the stronger pull of epistemic justification in school tasks.

The most dramatic shift appears in generality. Personal generality—claims anchored in the self or a specific episode—is common in Grade 2 but drops quickly. Generic generality rises just as quickly, reaching near-ceiling by Grade 3 and staying high thereafter. This leap toward generalized, kind-level claims is a hallmark of the academic register and signals increasing capacity for decontextualization—moving beyond the here-and-now to talk about people or situations in the abstract (Berman and Nir-Sagiv, 2010; Schleppegrell, 2004; Uccelli et al., 2013). Impersonal generality remains comparatively rare, suggesting that children's developmental route to abstraction favors generic formulations over impersonal ones.

In summary, the category-level patterns confirm Hypothesis 2. Development is not merely additive but a rebalancing of the stance toolkit: children pivot from writer to text orientation, from personal to generic generality, and from emotional to epistemic stance. By the end of elementary school, this constellation supports more decontextualized, academically styled argumentation in Hebrew.

4.4 Association patterns and stance profiles (research question 3)

Beyond frequency changes, the association analyses show how stance resources converge into patterned rhetorical profiles. In Grade 2, writer orientation, personal generality, and emotional stance cohere into a self-anchored and affective profile. By Grade 5, text orientation, generic generality, and epistemic stance align to form an impersonal and evidence-oriented profile, with Grades 3 and 4 functioning as transitional phases in which both constellations coexist and become increasingly differentiated. In other words, children are not simply accumulating resources. They gradually reshape how resources combine, and different profiles become more salient across grades.

This restructuring resonates with Du Bois's stance triangle, which models stance as a configuration that links evaluation, positioning, and alignment (Du Bois, 2007). In our correlations, the early texts align the self through writer orientation, personal generality, and emotional stance, whereas later texts align evidence and content through text orientation, generic generality, and epistemic stance. The findings also extend the Appraisal framework in Systemic Functional Linguistics (Martin and White, 2005). With development, writers move away from inscribed affect and toward engagement and graduation resources that signal evidentiality and commitment, which maps onto the rise of epistemic stance and generic reference in our data.