- 1Faculty of Law, University of Tasmania, Hobart, TAS, Australia

- 2Centre for Marine Socioecology, University of Tasmania, Hobart, TAS, Australia

- 3Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, University of Tasmania, Hobart, TAS, Australia

- 4Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, Oceans and Atmosphere, Hobart, TAS, Australia

Traditional marine governance can create inferior results. Management decisions customarily reflect fluctuating political priorities and formidable special-interest influence. Governments face distrust and conflicts of interest. Industries face fluctuating or confusing rules. Communities feel disenfranchised to affect change. The marine environment exhibits the impacts. While perceived harm to diverse values and priorities, disputed facts and legal questions create conflict, informed and empowered public engagement prepares governments to forge socially legitimate and environmentally acceptable decisions. Integrity, transparency and inclusiveness matter. This article examines positive contributions engaged communities can make to marine governance and relates it to social license. Social license suffers critique as vague and manufactured. Here its traditional understanding as extra-legal approval that communities give to resource choices is broadened to include a legally sanctioned power to deliberate—social license to engage. The starting hypothesis rests in the legal tradition designating oceans as public assets for which governments hold fiduciary duties of sustainable management benefiting current and future generations. The public trust doctrine houses this legal custom. A procedural due process right for engaged communities should stem from this public-asset classification and afford marine stakeholders standing to ensure management policy accords with doctrinal principles. The (free), prior, informed consent participation standard provides best practice for engaged decision-making. Building on theories from law, social, and political science, we suggest robust public deliberation provides marine use actors methods to earn and sustain their social license to operate, while governmental legitimacy is bolstered by assuring public engagement opportunities are available and protected with outcomes utilized.

Introduction

Unsustainable use of marine resources and environmental degradation behooves governments responsible for their marine waters to devise more effective means of governance. The extra-legal concept of social license is one such means but requires a firmer footing to enhance its credibility and usefulness. Legalized rights of stakeholder engagement in decision-making for marine space uses, via stakeholders’ social license to engage (SLE), can provide a sound way for marine project proponents and the governments that oversee them to earn and maintain their social license to operate (SLO). This hypothesis grounds the primary author’s Ph.D. thesis work in process – Legally Sanctioned Engagement in Marine Governance: A New Paradigm for Social License as a Path to Ocean Sustainability.

We propose that the marine space’s distinctive character as a public natural asset generates a public right to engage in making decisions that accord with fiduciary principles of the public trust doctrine applicable to shared environmental assets. Our work contributes to marine governance research by synergistically linking three separate concepts–the legal public trust doctrine, the prior informed consent (PIC) participation model and the social license concept. Utilizing this theoretical linkage, it proposes creation of an implementation framework for best practice marine use decision-making that utilizes a fiduciary model of legal standards customizable to various marine applications and governance regimes.

Challenges to Optimal Marine Governance

Sustainably governing our world’s marine space faces significant challenges. Not only does the interconnected marine estate lie in a multitude of international governmental jurisdictions (United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, 1982) other exigent factors include those dealing with actors, scale and knowledge (Campbell et al., 2016). Below, we overview four themes challenging effective marine governance and the decision-making behind it.

Fluctuating Political Priorities

Marine policy priorities that vary with political party or controlling regimes can lead to one step forward-two step back governance, lacking consistently high standards of sustainable use and protection (Wood, 2014; Bakaki et al., 2019).

Formidable Industry and Public Interest Influence

Diverse values and priorities held by different stakeholder networks (On Common Ground Consultants Inc., and Robert Boutillier and Associates, 2014) can create tension and conflict in marine governance. Economic development priorities can clash with marine conservation, esthetic, or recreational goals. Interest-aligned stakeholders can exert significant pressure on government actors to sway decision-making outcomes (Campbell et al., 2016).

Conflicting Government Roles and Responsibilities

Faced with external policy pressure and intra-governmental disagreements fed by the scope and often divergent nature of public service roles and responsibilities, government actors can find themselves at odds with making sustainable marine decisions. For example, governments’ political responsibility to facilitate a robust and stable yet equitable economy can conflict with its fiduciary responsibility to protect public natural resources, which are often the site or source of economic development activities (Callahan, 2007; Wood, 2014).

Vague Environmental Principles and Bureaucratic Rules

Finally, marine policy principles, enabling statutes, and administrative rules can be vaguely written, leaving final use decisions and law enforcement subject to the variable discretionary interpretation of government administrators. These can also fluctuate based on the bias of political elites and their responsiveness to lobbying by vested economic interests (Wood, 2014; Scotford, 2017). In addition, areas of sovereign marine space usually fall under different bureaucratic regimes. For example, in federally constituted countries such as Australia, Canada, and the United States, the Exclusive Economic Zone customarily falls under national jurisdiction, while inshore areas of territorial seas can be governed under state/provincial legislation (United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, 1982).

Benefits and Costs of Public Stakeholder Engagement

To govern effectively when faced with competing priorities and values, legislators and administrators “need mechanisms with which to view and understand the relevant public values at play for a given policy issue or controversy. (and) frameworks that allow them to more effectively and consciously consider which public values to uphold and which tools and methods are most likely to do so” (Nabatchi, 2018, p. 6). “(N)o single institution can be expected to hold all of the expertise and knowledge needed for good decision-making.” (Richardson and Razzaque, 2006, p. 170). A framework of best-practice marine project review and management procedures containing robust public engagement should provide those entrusted with governing highly valued natural resources, such as the marine space, with a much-needed mechanism to balance conflicting views that often frustrate a clear direction.

Understandably, it can cost additional time and money to implement the integral participatory processes, including those related to early project planning and development (Richardson and Razzaque, 2006). However, a plethora of benefits support increasing citizen participation in governance, including public education, facilitation of transparency, accountability, and legitimacy, and reduction of unproductive conflict (Callahan, 2007; Reed, 2008). These benefits, along with improved corporate relations, goodwill and governmental trust that can develop from inclusive and transparent decision-making, have flow-on rewards.

In times of widespread mistrust and lack of confidence in government leaders (Wike et al., 2019),1 the integrity of the process for governing environmental resources especially matters (van Putten et al., 2018). As beneficiaries of public natural resources, marine stakeholders have a reasonable interest being involved in decision-making regarding activities affecting that resource (Callahan, 2007).

In Arnstein’s renowned “ladder” representing levels of citizen participation, credible consultative processes involve partnerships that include discussion, deliberation, and negotiated outcomes (Arnstein, 1969; International Association for Public Participation, 2017). It is not one-way reporting to keep others informed of pre-determined plans and outcomes (Ross et al., 2002; Callahan, 2007). Robust, legally sanctioned stakeholder engagement should reduce counter-productive conflict about marine governance, support diverse, socially licensed stakeholder relationships, increase likelihood of environmentally sustainable marine management (Nanz and Steffek, 2006) and legitimatize decisions made. Likewise, transparent decision-making should improve management quality (Richardson and Razzaque, 2006; Callahan, 2007; Nordquist et al., 2018). Effective marine management is ultimately measured against ecological sustainability,2 which is in civil society’s highest and best long-term interest (United States Supreme Court, 1892). In the short-term, however, its importance can be diluted by competing policy considerations such as economic development and political expediencies.

We argue that citizen stakeholders are entitled to fair, consistent and accountable treatment with more than merely a voice in legislative decisions about the marine estate. Marine stakeholders have right to a say in those decisions to ensure they utilize local knowledge and conform to standards of care embodied in governments’ fiduciary role. This role carries legal obligations of honesty, full disclosure and acting in public beneficiaries’ best interest as stewards of the natural asset. We further argue that these rights are embodied in a legal theory of public trust, which courts of law can uphold. Discussion of these propositions follows.

Discussion

An Expanded Paradigm for Social License

We envision social license to encompass a framework of marine management standards and public participatory consent rights. We also advocate its use as the ultimate barometer of governmental decision-making in public natural resource governance.

“Social license to operate” is traditionally understood as the extra-legal “stamp of approval” that a substantial majority of community stakeholders give to proponents and operators of commercial endeavors (Parsons et al., 2014; Moffat et al., 2015). One issue with social license concerns what portion of a stakeholder community can sanction a project’s approval (Reed et al., 2009). Without a tallied vote, a quantifiable majority is uncertain. However, attaining acceptance commonly requires factors of legitimacy, credibility and trust being present in relations between the community and a business (On Common Ground Consultants Inc., and Robert Boutillier and Associates, 2014; van Putten et al., 2018). The presence of SLO can be recognized on a continuum from absence of significant conflict over operations to community enrollment in the vision and mission of a company or industry3.

The SLO concept also has geographically diverse usage and endorsement. Its intangible nature and the practical questions that begets create a lack of universal understanding of its meaning and differences in assumptions relative to its application. This includes critique of corporate use as a method to manage development opposition or downplay conflict (Hall et al., 2015; Moffat et al., 2015). We find shortcomings in the concept for additional reasons relating to lack of protocols and processes for its expression and the limited purpose of its traditional meaning. For example, the best criteria and process for SLO attainment in discrete sectors are not well substantiated in current practice. Further, SLO is often used only in relation to community views of private sector conduct (van Putten et al., 2018).

A Proposed New Social License to Engage

Social license should encompass not only more rigorous criteria for its attainment, but also be applied more broadly.

While the literature on SLO suggests a collection of elements believed to necessitate its attainment and, to a lesser extent, its retention, a dearth of practical guidance exists on a process for acquiring and linking those elements to sustainable marine management. Our research aims to help fill this gap by examination of empirical evidence of marine stakeholder views on marine project approval processes and sustainable marine governance. Utilizing case studies of salmon aquaculture industries in Tasmania, Australia, and Nova Scotia, Canada, in addition to drilling offshore Nova Scotia, we aim to propose a customizable implementation framework for participatory marine management. Results of this research, its implications and applications will appear in future publications and presentations associated with the Ph.D. thesis.

In the interim, we posit that the premise behind SLO is best understood and utilized through study of Greek Sophist philosophy reflecting empowerment of the governed (Keeley, 1995). Viewed through this lens, the concept is reframed to encompass civil society’s power to deliberate and negotiate the rules governing them and their domain—what we term a SLE. This imbues social license with a multifaceted grant of action. Social license should not only represent an operational permit for industry predominantly free of non-productive conflict. Rather, the essence of social license should also represent a participation permit for civil society that is legally sanctioned and protected.

Further, a framework for marine governance is best developed from criteria necessary for creation of value-influenced relationships like social license. This research finds these criteria embodied in the concept of PIC as a best-practice standard for engaged participation (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987). Traditionally known as free, prior informed consent, PIC is most often recognized with indigenous peoples in relation to their land, community space and natural resources (United Nations, 2007). In our research, the practice provides a benchmark for high-level engagement of public stakeholder networks in decision-making about marine space uses. The intrinsic nature of PIC is as a qualitative process by which a project proponent strives to achieve agreement to proceed from stakeholder groups potentially affected in some material way. The group members and application method of PIC depends on the specific context of its use because it is not a “stand-alone” right. Rather, the freedom to engage in deliberative decision-making derives from rights associated with underlying things that a marine activity might potentially affect (United Nations REDD Programme, 2013). For example, the right to participate in marine decision-making arguably derives from society’s substantive right of access to and enjoyment of a healthy, sustainable marine space held by the state as a public trust asset.

Elements generally recognized as essential for establishing PIC are:

1. A voluntary participation process with Freely-given project acceptance (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2016);

2. Stakeholder consent given Prior to official project approval or grant of legal license and before financing (Hanna and Vanclay, 2013);

3. Stakeholders fully-Informed about project details, their rights, implications, risks and worst-case scenarios (Goodland, 2004);

4. Consent. Descriptions include:

4.1 a collective decision made in phases by rights-holders, “reached through their customary decision-making processes” (United Nations REDD Programme, 2013);

4.2 acceptance of at least 51% of potentially affected parties (Goodland, 2004) (but ordinarily a substantially larger majority);

4.3 a process with participation and consultation being central (Barelli, 2012);

4.4 a voluntary agreement designed to make a project acceptable (Goodland, 2004).

While application of PIC in diverse marine stakeholder communities can instigate discontent, an inclusive deliberative process should best assure socially licensed decisions. At any rate, management of marine resources by government agencies with only token involvement of impacted and interested stakeholders is already a common source of marine community conflict.

It is through legal legitimization of a participatory consent protocol, like PIC, that extra-legal, socially licensed, mutually endorsed relationships between a network of diverse marine use stakeholders (interested citizens, project proponents, and government officials) has potential to exist.

The Public Trust Doctrine: A Normative Legal Foundation for Social Licenses to Operate and Engage

If project proponents’ SLO and public stakeholders’ SLE include a right of stakeholder consent in public natural resource management decisions, a legal basis is needed for ensuring both management practice standards and a right for citizens to participate in deliberation about them.

The legal public trust doctrine fundamentally stands for the premise that certain natural resources are part of an inalienable public trust. As such, government authorities have a fiduciary role to sustainably manage and guard those resources against harm. Further, every citizen is considered a beneficiary of the trust and may invoke its terms to hold government trustees accountable, with potential judicial protection against violation of their related rights (Sand, 2007). The doctrine’s historic focus in the United States, the jurisdiction where the doctrine has received greatest legal affirmation, is in regard to navigable waters (Sax, 1970; Thompson, 2006).

We look to the doctrine’s ability to serve as the legal basis for required marine standards of care necessary to attain SLO. The SLO can benefit from rigorous linkage to these fiduciary duty elements of the public trust as the criteria under a SLO attainment protocol. We also tap the doctrine as the basis for stakeholder rights to engage in marine decision-making under a model of PIC.

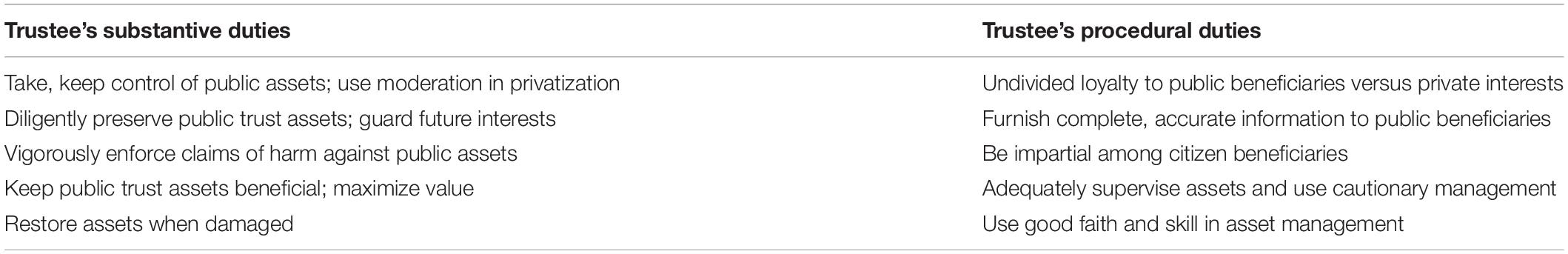

In legal jurisdictions firmly recognizing the doctrine, governments’ role is that of a trustee in a fiduciary capacity to citizen beneficiaries4. The doctrine is commonly understood to include the duties depicted in Table 1, which also may be legislatively enacted or judicially defined (Archer et al., 1994; Wood, 2014). Duties having the nature of overarching policy should be embedded in legislative preambles that direct the laws’ purpose and intent. Duties having discreet methods for operationalization should be contained in appropriate sections of the substantive legislation with sufficient detail as to adequately guide administrative rule-making that supports their mandate.

Our research considers the doctrine’s normative potential for governance of all environmental resources in the marine estate. Because the public trust duties of care should apply equally whether the waters and resources are under local, national, or international management and control, it follows that the right for public stakeholder decision-making participation should also apply. In four large-scale trials, Weeks concluded the possibility exists for large, public deliberation processes that enable governments to take effective action on difficult issues (Weeks, 2000). Further, an international example of participatory decision making in action is the Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC) concerning North American environmental issues. The CEC also enables empowered participation in environmental law compliance via public submissions of enforcement concerns (Commission for Environmental Cooperation, 2020). Finally, direct democracy via ballot issue voting remains the purest form of participatory decision making in appropriate situations.

The Independent World Commission on Oceans has declared “[a] more informed and active civil society with significantly enlarged opportunities to participate in ocean affairs is a precondition for a more responsive and democratic system of ocean governance. It is in the critically important area of ocean governance that competing issues and divergent interests and opinions must be accommodated and reconciled.” (Independent World Commission on the Oceans, 1998).

We propose civil society’s permit for deliberative engagement on marine use affairs, encompassed in a SLE and nested under a standard of PIC, should be legally sanctioned and judicially protected through legislative or common law revitalization of the public trust doctrine. The doctrine can extend legal standing rights to citizens to protect their beneficiary interests in sustainable ocean resource management when government actors abuse or neglect duty of care terms under the public trust (Turnipseed et al., 2009).

Conclusion

“Humanity’s relationship to the sea is not just a legal property relationship, but a social relationship of participation.” (Van Dyke et al., 1993).

The foundational rationale of our research is that diverse stakeholders have a value and/or priority-driven interest in reaching a mutually agreeable position on marine resource uses, especially when their values and priorities diverge. SLO is the carrot that makes a participatory consent process worth pursuing. And a participatory consent process, akin to PIC, presumptively available to civic marine stakeholders under a public trust legal theory of SLE, is a means for possible creation of that social acceptance. While unanimous agreement on decisions is unlikely, our proposals in this article widen the participation sphere for input, thus improving chances of developing a SLO. However, if non-governmental marine stakeholders are not empowered to make final decisions, the full community of consultative and beneficial parties should receive a report of official conclusions reached, including their rationale, along with a process by which stakeholders can petition the governmental authority to reconsider its decision on specified grounds.

When separated, PIC and social license miss not only the nature of their relationship, but also their ability to work symbiotically for creation of win3 outcomes (for project proponents, governments, and concerned stakeholders) in marine space activities. As beneficiaries of public marine assets, civic stakeholders hold power through their SLE in decision-making to shape sustainable management of the public marine trust. These voices, and the decisions made by way of them, represent the real relationship between PIC and social license.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

LU-K conceived of the presented idea and developed the theory. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The Oceans and Atmosphere Division of the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), Hobart, Tasmania, funded the open access publication fee for this article. It did not provide any funding for the primary/corresponding author’s thesis research that is the basis for this Perspective article. That author’s thesis research is funded by the University of Tasmania’s Centre for Marine Socioecology and Faculty of Law.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The corresponding author expresses appreciation to her Ph.D. supervisory team, Professor Richardson, Dr. van Putten, and Dr. Kate Booth, for their ongoing guidance in her thesis progress, and to her supervisor co-authors for their skilled counsel in refining this article’s message. The University of Tasmania’s Centre for Marine Socioecology and Faculty of Law have provided funding for this thesis research and are due heartfelt gratitude.

Footnotes

- ^ For example, in Pew Research’s Spring 2018 Global Attitudes Survey of 27 countries, 60% of respondents felt that, “No matter who wins an election, things do not change very much” describes their country well and 54% felt that, “Most politicians are corrupt” describes their country well (Wike et al., 2019).

- ^ Ecological sustainability as used herein draws from Richardson and Razzaque (2006, p. 166) “Sustainability depends largely on the way economic, social and environmental considerations have been integrated in decision-making.”; Goldsmith et al. (1972). (“. . . a society . . . depend[ing] not on expansion but on stability.”); World Commission on Environment and Development (1987, p. 43), in which resource exploitation and investment direction (among others) are “. . . in harmony and enhance both current and future potential to meet human needs and aspirations.”).

- ^ Ibid, at What Is the Social License?

- ^ To varying degrees, the Doctrine or its core principles exist as a component of environmental law in several countries including Australia, Brazil, Canada, Ecuador, Eritrea, India, Kenya, Nepal, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, Uganda, and the United States. See Hare and Blossey (2014).

References

Archer, J. H., Connors, D. L., Laurence, K., and Chaphin, S. (1994). The Public Trust Doctrine and the Management of America’s Coasts. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press

Bakaki, Z., Bohmelt, T., and Ward, H. (2019). The triangular relationship between public concern for environmental issues, poliy output, and media attention. Environ. Polit. 1:188.

Barelli, M. (2012). Free, prior and informed consent in the aftermath of the UN Declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples: developments and challenges ahead. Int. J. Hum.Rights 16, 1–24. doi: 10.1080/13642987.2011.597746

Callahan, K. (2007). Citizen participation: models and methods. Int. J. Public Admin. 30:1179. doi: 10.1080/01900690701225366

Campbell, L. M., Gray, N. J., Fairbanks, L., Silver, J. J., Gruby, R. L., Dubik, B. A., et al. (2016). Global oceans governance: new and emerging issues. Ann. Rev. Environ. Resourc. 41:21.

Commission for Environmental Cooperation (2020). Available online at: http://www.cec.org/ (accessed May 22, 2020).

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2016). Free Prior and Informed Consent, An Indigenous Peoples’ Right and a Good Practice for Local Communities: Manual for Project Practitioners. Rome: FAO

Goldsmith, E., Allen, R., Allaby, M, Davoll, J., and Lawrence, S. (ed.) (1972). A Blueprint for Survival. The Ecologist, Vol. 2. Surrey: Ecosystems Ltd, 1.

Goodland, R. (2004). Free, prior and informed consent and the world bank group. Sustain. Dev. Law Policy 4, 66–74.

Hall, N., Lacey, J., Carr-Cornish, S., and Dowd, A.-M. (2015). Social licence to operate: understanding how a concept has been translated into practice in energy industries. J. Clean. Product. 86, 301–310. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.08.020

Hanna, P., and Vanclay, F. (2013). Human rights, indigenous peoples and the concept of free, prior and informed consent. Impact Assess. Project Appraisal 31, 146–157. doi: 10.1080/14615517.2013.780373

Hare, D., and Blossey, B. (2014). Principles of public trust thinking. Hum. Dimens. Wildlife 19:397. doi: 10.1080/10871209.2014.942759

Independent World Commission on the Oceans (1998). The Ocean Our Future-The Report of the Independent World Commission on the Oceans. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

International Association for Public Participation (2017). International Association for Public Participation. “IAP2 Spectrum.” Available online at: https://iap2usa.org/resources/Documents/Core%20Values%20Awards/IAP2%20-%20Spectrum%20-%20stand%20alone%20document.pdf (accessed May 26, 2020).

Keeley, M. (1995). Continuing the social contract tradition. Bus. Ethics Q. 5, 241–255. doi: 10.2307/3857355

Moffat, K., Lacey, J., Zhang, A., and Leipold, S. (2015). The social licence to operate: a critical review. Forestry 89, 477–448. doi: 10.1093/forestry/cpv044

Nabatchi, T. (2018). Public values frames in administration and governance. Perspectives on Public Management and Governance 1, 59–72. doi: 10.1093/ppmgov/gvx009

Nanz, P., and Steffek, J. (2006). “Deliberation and democracy in global governance: the role of civil society” in Participation for Sustainability in Trade. eds S. Thoyer and B. Martimort Farnham: Ashgate.

United States Supreme Court (1892). Ill. Cent. R.R. Co. v. Ill. U.S. United States Supreme Court. 146: 387. Washington, DC: United States Supreme Court.

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (1982). United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, 157/168 Parties: 16 November 1994. Geneva: United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

Nordquist, M. H., Moore, J. N., and Long, R. (eds). (2018). Legal Order in the World’s Oceans: UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. Leiden: Brill Nijhoff.

On Common Ground Consultants Inc., and Robert Boutillier and Associates (2014). SociaLicense.com Available online at: http://socialicense.com/index.html (accessed October 29, 2016).

Parsons, R., Lacey, J., and Moffat, K. (2014). Maintaining legitimacy of a contested practice: how the minerals industry understands its ’social licence to operate. Resources Policy 41, 83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.resourpol.2014.04.002

Reed, M. S. (2008). Stakeholder participation for environmental management: a literature review. Biol. Conser. 141:2417. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2008.07.014

Reed, M. S., Graves, A., Dandy, N., Posthumus, H., Hubacek, K., Morris, J., et al. (2009). Who’s in and why? A typology of stakeholder analysis methods for natural resource management. J. Environ. Manag. 90:1933. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2009.01.001

Richardson, B. J., and Razzaque, J. (2006). “Public participation in environmental decision-making” in Environmental Law for Sustainability. eds B. J. Richardson, and S. Wood. Oxford: Hart Publishing, 165.

Ross, H., Buchy, M., and Proctor, W. (2002). Laying down the ladder: a typology of public participation in australian natural resource management. Austr. J. Environ. Manag. 9:205. doi: 10.1080/14486563.2002.10648561

Sand, P. H. (2007). “Public trusteeship for the oceans” in Law of the Sea, Environmental Law and Settlement of Disputes: Libor Amicorum Judge Thomas, eds A. Mensah. T. M. Ndiaye and R. Wolfrum. Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers: 521.

Sax, J. L. (1970). The public trust doctrine in natural resource law: effective judicial intervention. Michigan Law Rev. 68:471. doi: 10.2307/1287556

Scotford, E. (2017). Environmental Principles and the Evolution of Environmental Law. Portland: Hart Publishing.

Thompson, B. H. Jr. (2006). The public trust doctrine: a conservative reconstruction & defense. South. Environ. Law J. 15:47.

Turnipseed, M., Crowder, L. B., Sagarin, R. D., and Roady, S. E. (2009). Legal bedrock for rebuilding America’s ocean ecosystems. Science 324, 183–184. doi: 10.1126/science.1170889

United Nations (2007). United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. 61/295. H. R. Council, Res.1/2, 29 June 2006. Sixty-first: 18. New York, NY: United Nations.

United Nations REDD Programme (2013). Guidelines on Free, Prior and Informed Consent, United Nations: 60. ıGeneva: United Nations REDD Programme.

Van Dyke, J. M., Zaelke, D., and Hewison, G., (eds). (1993). Freedom for the Seas in the 21st Century: Ocean Governance and Environmental Harmony. Washington, DC: Island Press.

van Putten, I. E., Cvitanovic, C., Fulton, E., Lacey, J., and Kelly, R. (2018). The emergence of social licence necessitates reforms in environmental regulation. Ecol. Soc. 23:24.

Weeks, E. C. (2000). The practice of deliberative democracy: results from four large-scale trials. Public Administrat. Rev. 60:360. doi: 10.1111/0033-3352.00098

Wike, R., Silver, L., and Castillo, A. (2019). Many Across the Globe Are Dissatisfied With How Democracy is Working. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2019/04/29/many-across-the-globe-are-dissatisfied-with-how-democracy-is-working/ (accessed 29 April, 2019).

Wood, M. C. (2014). Nature’s Trust: Environmental Law for a New Ecological Age. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Keywords: marine governance, free, prior, and informed consent, public participation, public trust doctrine, social license to engage, stakeholder decision making, stakeholder deliberation, social license to operate

Citation: Uffman-Kirsch LB, Richardson BJ and van Putten EI (2020) A New Paradigm for Social License as a Path to Marine Sustainability. Front. Mar. Sci. 7:571373. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.571373

Received: 10 June 2020; Accepted: 18 September 2020;

Published: 19 October 2020.

Edited by:

Natasa Maria Vaidianu, Ovidius University, RomaniaReviewed by:

Edward Jeremy Hind-Ozan, Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, United KingdomClaudia Baldwin, University of the Sunshine Coast, Australia

Copyright © 2020 Uffman-Kirsch, Richardson and van Putten. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lisa B. Uffman-Kirsch, TGlzYS5VZmZtYW5LaXJzY2hAdXRhcy5lZHUuYXU=

Lisa B. Uffman-Kirsch

Lisa B. Uffman-Kirsch Benjamin J. Richardson1,2,3

Benjamin J. Richardson1,2,3 Elizabeth Ingrid van Putten

Elizabeth Ingrid van Putten