- 1Mundus maris asbl, Brussels, Belgium

- 2Linkrural, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

The Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries in the Context of Food Security and Poverty Eradication (SSF Guidelines) have been adopted by FAO’s Committee of Fisheries in 2014. In this short research report, we present action research with self-selected men and women in small-scale fisheries in Senegal, a country with a large and dynamic SSF, which suffers, however, from diminishing profitability as a result of multiple pressures. We report ongoing work on the principles and approaches of the Small-Scale Fisheries Academy as a way to support the implementation of these Guidelines. The first phase of developing the SSF Academy focuses on testing learning methods aimed at developing critical thinking, planning and action. Respectful dialogue in the secure space of the Academy made academy learners, particularly women and younger participants, gradually more confident, articulate, and active. They started harvesting the results of enacted planning. We cautiously argue that it would be useful to expand these tests combining dialogue, the art of hosting communication and visual thinking to different places in Senegal and elsewhere. They provide an opportunity to address sensitive social issues like gender equity and intra-household violence and open perspectives on other societal challenges that hamper the implementation of the Guidelines. Despite the difficult conditions of the pandemic and given the rather limited work during the pilot phase before, the Academy’s participatory and inclusive learning and empowerment approach had an impact on the individual learners and the group and thus contributed to the implementation of the SSF Guidelines.

Introduction

The Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries in the Context of Food Security and Poverty Eradication (SSF Guidelines) have been adopted by FAO’s Committee of Fisheries (COFI) in 2014. The provisions of the Guidelines are based on human rights recognizing the roles and importance of previously typically neglected men and women and their communities (Chuenpagdee and Jentoft, 2011). They cover the guiding principles and how governments should translate these into responsible fisheries and sustainable development along entire value chains and ensuring gender equality. Governance, research and information, capacity development and efforts to support and monitor implementation are also covered. Their adoption followed an extensive, bottom-up consultation process between 2010 to 2013 that involved more than 4,000 stakeholders from governments, professional and civil society organizations and scientists from 120 countries (FAO, 2015). The voluntary nature of the SSF Guidelines allows flexibility in adjusting the concrete implementation to national and local conditions. While small-scale fisheries around the world share aggregate characteristics (Jacquet and Pauly, 2008) they lack a unique technical definition (Smith and Basurto, 2019). Sustainable Development Goal 14 Target B (SDG 14.B) gives further recognition to the need for explicit implementation efforts1.

The last decade has seen numerous initiatives and research efforts to demarginalize small-scale fisheries and strengthen gender equity to counterbalance dominant technocratic policy approaches focused on industrial fisheries. Among these, the global network of researchers and practitioners ‘‘Too big to ignore’’2 has significantly increased the documentation of SSF across the globe (Jentoft and Chuenpagdee, 2015; Jentoft et al., 2017; Johnson et al., 2018), while FAO3 focuses on keeping the SSF Guidelines on the political agenda and the ‘‘Sea Around Us’’ reconstructs marine catches, including those of SSF4.

Gender has been an even more neglected dimension, not only in fisheries and aquaculture (Williams et al., 2005), but in many societal spheres (Gaye et al., 2010) notwithstanding some progress (Dorius and Firebaugh, 2010). We note an increase in attention to gender in fisheries following the adoption of the SDGs in 2015 (Nauen and Williams, 2019). Despite the scant gender differentiation in national accounting systems, Harper et al. (2020) even managed to estimate the contribution of women to fish food production.

Nevertheless, the implementation gap of global agreements remains high (Hudson et al., 2019). This is aggravated during the corona pandemic, which reversed advances in several areas and widened the gap between rich and poor within and between countries (Engzell et al., 2021; Fenner and Cernev, 2021).

Senegal has burgeoning artisanal fisheries (Fontana and Samba, 2013). Employment figures (Sall et al., 2006; République du Sénégal, 2007) are, however, difficult to ascertain under conditions where official statistics covered only a fraction of the reconstructed catches (Belhabib et al., 2015). The competition – and occasional cooperation – between industrial and artisanal fisheries together with very high levels of IUU fishing (Belhabib et al., 2015) and climate change weigh heavily on a shrinking resource base. These conditions reduced the profitability of SSF (Ba et al., 2017). This has particularly affected women because, without access to affordable credit, they cannot continue to pre-finance now more expensive fishing trips (Sall, 2018). Countering the associated weakening of social solidarity chains requires enacting reforms at the macro-level, such as phasing out harmful subsidies to industrial fleets (SDG 14.6) and social innovations at the micro-level for greater participation of SSF in governance.

Here we present the principles and approaches of action research for the development of the Small-Scale Fisheries Academy in Senegal as a way to help close the implementation gap. The first phase serves to test active and inclusive learning methods and spread awareness of the Guidelines to improve livelihoods and strengthen capacity for participation in fisheries governance.

Methods

The methodological approach dwells on a broad foundation constituted by Freire’s vision of dialogue (1987) as a mode in which an educator accompanies a learner to reflect, apprehend and act on the world around them. Boaventura de Sousa Santos’ notion of ecologies of knowledges (2007, 2009) recognizes different ways of coding and expressing knowledge as legitimate. He demands their recognition and blending through dialogue processes as a way to address situational complexities in a non-hegemonic way.

Moreover, we apply the social communication for behavior change and art of hosting approach to leadership that scales up from the personal to the systemic using personal practice, dialogue, facilitation and the co-creation of innovation to address complex challenges (Nauen and Hillbrand, 2015). More specifically, we refer to the Gender Action Learning System (Mayoux and Oxfam-Novib, 2014) to operationalize the research and test these affirmed methods in a different context. The visual practices used ensure that adults with little or no formal schooling can actively participate in critical thinking and action for change at individual and collective levels.

This action research aims to enhance the planning skills of learners through a fun process of envisioning, clarifying thoughts and acting toward their individual and collective goals (Arraes Treffner, 2019a). The facilitation process during workshops ensures that all learners have equal rights in terms of time and space to speak about their experiences, their views and their perspectives. By encouraging learners to use drawings and symbols to articulate their dreams and a main objective they want to achieve within a year, the abstract becomes concrete. The process of drawing out what opportunities they expect to create during quarterly steps, but also reflecting on the obstacles they might encounter, requires them to critically analyze their change journey. Graphical facilitation offers the learners a range of tools to foster richer dialogues and to explore specific aspects more in-depth (Nauen and Arraes Treffner, 2021). An important part of the process is to motivate participants to discuss their individual plans with other participants, with family, neighbors and peers in order to enrich the reflection and make it more robust by building collective visions and mutual support around such plans. As the learners gain confidence, it is envisaged to support the development of collective plans, for example by women’s savings groups, fishers, fish processors, or community members engaged in marine protected areas and co-management (Nauen and Arraes Treffner, 2021).

We thus design the SSF Academy as a multi-stakeholder space, where fishers, women fish processors and their economic interest groups, traders, boatbuilders and other professionals from the entire value chain can respectfully dialogue with one another as well as with representatives of administrations, scientists, civil society organizations and other resource persons. Such settings can produce locally adapted knowledge to generate innovative solutions and pave the way for more social justice and gender equity. It is intended “as a secure place for co-learning and co-production of knowledge for wellbeing in the sector, protection of marine biodiversity and better governance” (Nauen and Sall, 2017). Champions are expected to become facilitators for others in order to strengthen collective action to play a more adequate role in addressing the structural disadvantages of SSF value chain actors.

Participants were invited from the local communities of Hann and Yoff, Senegal, to test the methodologies. The engagement of organizational and religious leaders and men and women active in different segments of the value chain was encouraged for diversity and multiplier effects. The original schedule called for a 1-year pilot phase, which, however, had to be extended due to the covid-19 pandemic. A more detailed account of the methodology and the testing phase is provided in Arraes Treffner (2019a; 2019b; 2019c) and Nauen and Arraes Treffner (2021). In the following, we summarize some results up to early 2021.

Results of the Small-Scale Fisheries Academy Pilot Phase

The inaugural event in November 2018 launched the SSF Academy in Senegal (Photo 1) with the active participation of some 60 men and women from all SSF related professions, age groups, associations and regions as well as academics and representatives of the fisheries department.

Photo 1. Inaugural event of the Small-Scale Fisheries Academy in Dakar, Senegal, November 2018 (Photo Mundus maris).

In the following, several training workshops took place with self-selected participants in both locations. They started with a contextualization, reminding academy learners of the SSF Guidelines as they relate to their own realities. Story-telling based on the experience of resource persons, an animated video in the local language, a documentary film on the status of fisheries in Senegal, and graphical recording supported deeper dialogue.

A visioning exercise inviting participants to draw what represents a good life to them allowed for individual and group reflections on what is important to them. As homework, the vision was then enriched by discussing each participant’s drawing with family, neighbors and professional groups. The immediate “outreach” encouraged the integration of individual and small-group visioning processes in the wider community. The comparison of drawings also made the commonalities directly visible to all.

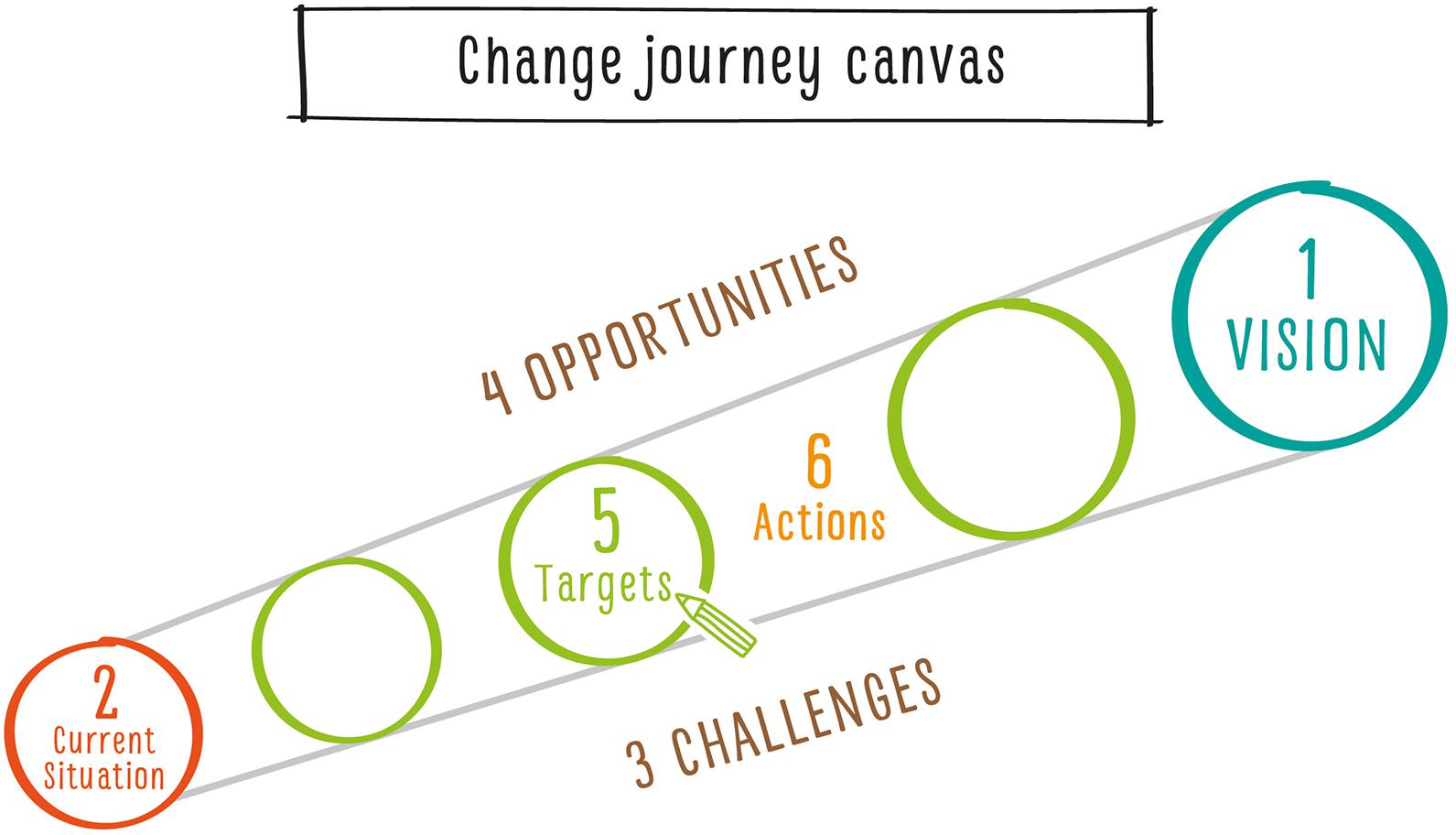

On the strength of that vision for the future, the academy learners were invited to identify and draw a concrete objective they expected to achieve within a year, along with quarterly intermediate targets. This structured planning was supplemented by a reflection on possible roadblocks, but also opportunities and support that could likely be enrolled during the implementation of the action plan (Figure 1). The individual planning was reinforced through group discussions and through plenary presentations and exchanges within the academy, honing capacities for clear and structured presentations to others in the process.

Figure 1. Change journey canvas for individual or collective one-year action plans (adapted from Mayoux and Oxfam-Novib, 2014).

The introduction of several canvasses also facilitated a more in-depth dialogue on the important features of life and livelihood. The visual exercises using the diamond canvas invited participants to explore the positive and negative aspects of their economic occupations in order to identify ways to improve their business organization.

A follow-up exercise allowed each participant’s specific activities to connect with others as part of the SSF value chain. The conversations made them more aware of their interdependence in the value-chain segments (Photo 2). It showed how the improvement efforts in their respective segment could have positive or negative effects on others.

Photo 1. Intense group deliberation preceding the presentation and discussion of results in plenary (Photo Maria Fernanda Arraes Treffner).

All academy exercises bring participants to prepare for action, in this case, identify how to increase synergistic effects for mutual benefits. Again, the drawings produced in gender-mixed groups by profession and then in plenary contributed to a deeper understanding of the interrelationships, prioritization and realization of operational gains.

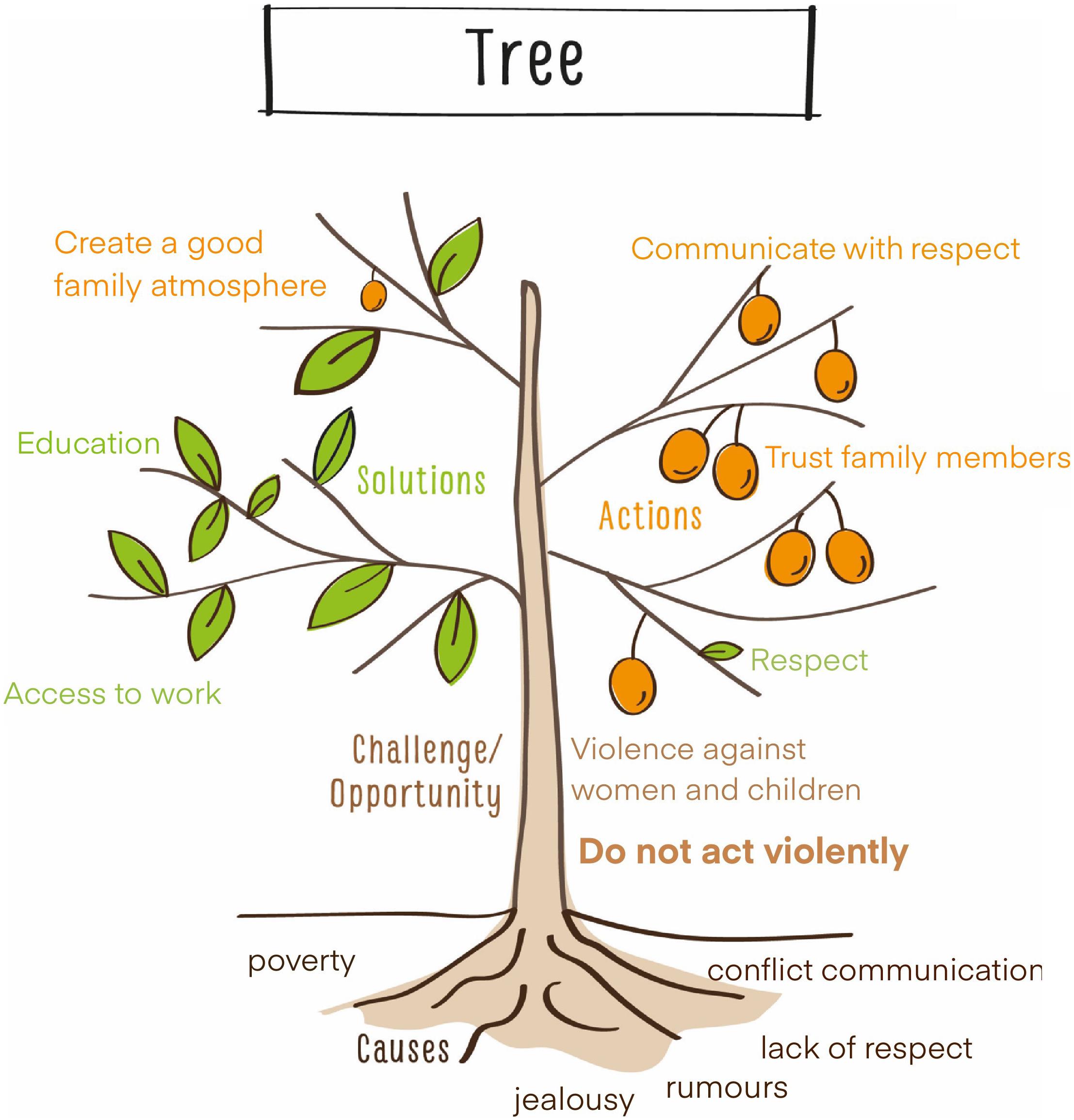

These discussions also brought to light a number of social and gender issues (Nauen and Arraes Treffner, 2021). Such issues might have been considered taboo in a more traditional teaching context. In this case, given the principles of gender justice, explicit attention was paid to concrete individual and local group conditions and dynamics. Participants were first offered the diamond to reflect on these challenges in sex-specific groups to identify aspects that should be addressed as a priority. Among these was domestic violence. Using a tree canvas, each group then exchanged what participants saw as the root causes and what needed to be changed to promote a safe space where women would have a voice in the household, the business and the decision-making (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The results of one group discussion applied in the generic canvas of an action tree – synthesis drawing made by the facilitator to capitalize on Academy experiences. All canvasses can be adapted to different topics.

The need to end violence against women and children was considered desirable by all. The consensus was that the fruits of common labor needed to accrue to all members in an equitable manner for the family business to be strong and resilient.

Introducing external expertise through an academic resource person also permitted to animate a critical reflection on how climate change is already affecting the community and what could be done about it.

The pandemic slowed down face-to-face meetings and relegated mentoring to more sporadic and limited exchanges through WhatsApp groups enabling at least some exchanges between participants and a subsequently elected academy committee in Yoff. The committee features both men and women in responsible positions and ensures at least some contact continuity with other learners.

At the end of February 2021, more than a year after the last substantive training, a short catch-up workshop was convened. The intention was to reconnect members of the entire group in a more structured way through an on-site meeting, to refresh memories and methods, and to test the feasibility of a hybrid format, combining a physical meeting with online co-facilitation. The greatest responsibility for facilitation rested with the local team to host the session.

Significantly, all previous learners attended. In small groups, they explained to each other how they had succeeded in relation to their annual action plans. Few examples could be presented in plenary. One particularly keen woman, Nabia, who had already set herself apart earlier by achieving her first quarterly target, had not only met her annual objective, but managed to earn enough to improve the roofing of her house. By systematically cutting costs through reducing non-essential expenses like clothes for social ceremonies, she had gathered sufficient investment money to increase her sales from one to six crates of fish a week, and also diversified into dried fish.

Other learners had dealt with unexpected adversities quite well by branching out into sheep husbandry and clothing sales, respectively. Diversification is not uncommon (Sall and Nauen, 2017), but not always within reach. Thus, some fishers had been prevented from going to sea and got indebted as they had been forced to use an operational loan for a fishing trip to cover living expenses.

In the event, the supportive online co-facilitation was only partially effective. Connection and translation difficulties prevented smooth interaction throughout. The members of the local hosting team were motivated, but did not yet have sufficient experience for autonomous facilitation. Nevertheless, the final appreciation of participants was to continue. Having one or more experienced facilitators “on the ground” is, of course, the preferred configuration for progressing in the development of the academy program and allowing the learners to become facilitators themselves and to strengthen collective action.

Discussion and Conclusion

Here we describe work in progress during the initial development phase of the SSF Academy in Senegal based on a range of conceptual (Freire, 1987; de Sousa Santos, 2007, 2009) and methodological approaches for engaging adults in the social process of learning to develop critical thinking, planning and action (Mayoux and Oxfam-Novib, 2014; Arraes Treffner, 2019a). As expected, the initial curiosity turned into greater commitment. Gradually, the women and younger participants became more confident, articulate and active over time, harvesting the results of enacting their planning. The methodological tests combining dialogue, the art of hosting communication and visual thinking exercises give rise to the expectation that the approach can be gainfully used in different situations and even allow to address sensitive social issues such as gender equity and domestic violence. It can gradually open to other stakeholders and offer new perspectives with external resource persons (Nauen and Arraes Treffner, 2021).

Even under the difficult conditions of the pandemic and considering the rather limited work during the pilot phase, the participatory and inclusive active learning and empowerment approach characteristic of the SSF Academy had an impact on the individual learners and the group as a whole beyond what could have been expected with more conventional training (see Supplementary Material). The participants clearly called for the continuation of the learning program. This request was particularly outspoken among those who were emerging as a new type of leader by appropriating the planning methods and implementing their action plans systematically. The set up and ongoing dialogue process in the Academy arena helps to manage this without creating conflict between the different sources of standing in the community.

The experience with the SSF Academy is still too recent to determine when the first group of learners will have reached a level of autonomy to act as champions/competent facilitators. But the first results not only justify to continue the next development steps in Senegal, but also try the approach in a different country and in other contexts to test its robustness and scalability.

The current pandemic illustrates the usefulness of reinforcing preparedness for the unexpected (Carpenter et al., 2008). Some elements are already present in the planning approach. Likewise, greater interaction between the public sector administration and the SSF Academy should foster improved governance by building trust and broadening perspectives brought to bear on the multiple challenges (Bohle et al., 2019).

In conclusion, the early results of this action research suggest that the SSF Academy’s adult education approach holds potential to make progress toward reducing the implementation gap between global frameworks and local realities. By providing information on the SSF Guidelines and having participants develop what they can mean for their livelihoods, the Academy gradually strengthens their capacities for collective action, advocacy and active participation in governance.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the General Assembly of Mundus maris. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the relevant individuals for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

CEN and MFAT conceptualized the research, critically reviewed the draft and produced the final version. MFAT led on-site field work and provided graphics. CEN wrote most of the manuscript. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The research for this brief research report is part of the development of the Small-Scale Fisheries Academy in Senegal. It is financially supported by Mundus maris asbl through its project “Exploring fisherfolk perspectives in Senegal in relation to policy reform and the future of the fisheries” (https://www.researchgate.net/project/Exploring-fisherfolk-perspectives-in-Senegal-in-relation-to-policy-reform-and-the-future-of-the-fisheries) and the project “Gender as an undervalued lens in fisheries and aquaculture,” respectively.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary video material: https://www.youtube.com/watch? v=DbcjY5PDUuc

Footnotes

- ^ https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal14

- ^ www.toobigtoignore.net

- ^ http://www.fao.org/voluntary-guidelines-small-scale-fisheries/en/

- ^ www.seaaroundus.org

References

Arraes Treffner, M. F. (2019a). Académie de la Pêche Artisanale au Sénégal. Design de L’initiative Pilote. Système d’apprentissage-Action Focalisé sur les Aspects du Genre Pour une Pêche Artisanale Durable. Rapport du Projet Mundus maris Académie de la Pêche Artisanale. Brussels: Mundus maris asbl, 26.

Arraes Treffner, M. F. (2019b). Formation de test et d’adaptation du 10 au 12 Juin 2020 Dans la Communauté de Yoff. Système D’apprentissage Action Focalisée sur les Aspects de Genre Pour une Pêche Artisanale Durable. Rapport du Projet Mundus maris Académie de la Pêche Artisanale. Brussels: Mundus maris asbl, 45.

Arraes Treffner, M. F. (2019c). Formation de test et d’adaptation du 13 au 15 juin 2020 Dans la Communauté de Hann. Système d’apprentissage Action Focalisée sur les Aspects de Genre Pour une Pêche Artisanale Durable. Rapport du Projet Mundus maris Académie de la Pêche Artisanale. Brussels: Mundus maris asbl, 47.

Ba, A., Schmidt, J., Deme, M., Lancker, K., Chaboud, C., Cury, P., et al. (2017). Profitability and economic drivers of small pelagic fisheries in West Africa: a twenty-year perspective. Mar. Policy 76:152. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2016.11.008

Belhabib, D., Sumaila, U. R., Lam, V. W. Y., Zeller, D., Le Billon, P., and Pauly, D. (2015). Euros vs. Yuan: comparing European and Chinese fishing access in West Africa. PLoS One 10:e0118351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118351

Bohle, M., Nauen, C. E., and Marone, E. (2019). Ethics to intersect civic participation and formal guidance. Sustainability 11:773. doi: 10.3390/su11030773

Carpenter, S. R., Folke, C., Scheffer, M., and Westley, F. R. (2008). Resilience: accounting for the noncomputable. Ecol. Soc. 14:13.

Chuenpagdee, R., and Jentoft, S. (2011). “Situating poverty: a chain analysis of small-scale fisheries,” in Poverty Mosaics: Realities and Prospects in Small-Scale Fisheries, eds S. Jentoft and A. Eide (Dordrecht: Springer), 27–42. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-1582-0_3

de Sousa Santos, B. (2007). Beyond abyssal thinking: from global lines to ecologies of knowledges. Review 30, 45–89.

de Sousa Santos, B. (2009). A non-occidentalist west?: learned ignorance and ecology of knowledge. Theory Cult. Soc. 26, 103–125. Special Issue Occidentalism: Jack Goody and Comparative History,

Dorius, S. F., and Firebaugh, G. (2010). Trends in global gender inequality. Soc. Forces 88:5. doi: 10.1353/sof.2010.0040

Engzell, P., Frey, A., and Verhagen, M. D. (2021). Learning loss due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118:e2022376118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2022376118

FAO (2015). Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries in the Context of Food Security and Poverty Eradication. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Fenner, R., and Cernev, T. (2021). The implications of the Covid-19 pandemic for delivering the Sustainable Development Goals. Futures 128:102726. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2021.102726

Fontana, A., and Samba, A. (eds) (2013). Artisans de la Mer. Une Histoire de la Pêche Maritime Sénégalaise. Dakar: Imprimé par La Rochette, 159.

Gaye, A., Klugman, J., Kovacevic, M., Twigg, S., and Zambrano, E. (2010). Measuring Key Disparities in Human Development: The Gender Inequality Index. Human Development Reports Research Paper, 46. New York, NY: United Nations Development Programme, 37.

Harper, S., Adshade, M., Lam, V. W. Y., Pauly, D., and Sumaila, U. R. (2020). Valuing invisible catches: estimating the global contribution by women to small-scale marine capture fisheries production. PLoS One 15:e0228912. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228912

Hudson, B., Hunter, D., and Peckham, S. (2019). Policy failure and the policy-implementation gap: can policy support programs help? Policy Design Pract. 2, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/25741292.2018.1540378

Jacquet, J., and Pauly, D. (2008). Funding priorities: big barriers to small-scale fisheries. Conserv. Biol. 22:832. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.00978.x

Jentoft, S., and Chuenpagdee, R. (eds.) (2015). Interactive Governance for Small-Scale Fisheries. MARE Publication Series, Vol. 13, Cham: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-17034-3

Jentoft, S., Chuenpagdee, R., Barragán-Paladines, M. J., and Franz, N. (eds.) (2017). The Small-Scale Fisheries Guidelines. Global Implementation. MARE Publication Series, Vol. 14, Cham: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-55074-9

Johnson, D. S., Acott, T. G., Stacy, N., and Urquhart, J. (eds.) (2018). Social Wellbeing and the Values of Small-Scale Fisheries. MARE Publication Series, Vol. 17, Cham: Springer.

Mayoux, L., and Oxfam-Novib (2014). Rocky Road to Diamond Dreams. GALS Phase 1. Visioning and Catalysing a Gender Justice Movement. Process Catalyst Manual. The Hague: OXFAM-NOVIB, WEMAN Programme, 120.

Nauen, C. E., and Arraes Treffner, M. F. (2021). “Strengthening capabilities of individuals and communities through a Small-Scale Fisheries Academy,” in Blue Justice: Small-Scale Fisheries in a Sustainable Ocean Economy, eds S. Jentoft, R. Chuenpagdee, A. Said, and M. Isaacs (London: Springer International Publishing).

Nauen, C. E., and Hillbrand, U. (2015). “Underpinning conflict prevention by international cooperation,” in Handbook of international negotiation: Interpersonal, intercultural, and diplomatic perspectives, ed. M. Galluccio (Cham: Springer), 157–172. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-10687-8_12

Nauen, C. E., and Sall, A. (2017). An Academy for Small-Scale Fisheries. Concept Note for an Exploratory Case Study. Available online at: https://www.mundusmaris.org/index.php/en/projects/2017/1684-academy-en (accessed March 18, 2021).

Nauen, C. E., and Williams, S. (2019). “Gender in fisheries in the times of sustainable development goals,” in Presentation at the MARE Conference, Amsterdam. Available online at: https://www.mundusmaris.org/index.php/en/projects/proj2019/2240-mare-en (accessed March 18, 2021).

République du Sénégal (2007). Lettre de Politique Sectorielle des Pêches et de l’Aquaculture. Dakar: Ministère de l’Economie maritime, des Transports maritimes, de la Pêche et de la Pisciculture, 44.

Sall, A. (2018). Entretien Avec Madame Khady SARR au Port de Pêche Artisanale de Hann. Available online at: https://www.mundusmaris.org/index.php/fr/rencontres/gens/2000-khadysarr-fr (accessed September 24, 2021).

Sall, A., and Nauen, C. E. (2017). “Supporting the small-scale fisheries Guidelines implementation in Senegal: alternatives to top-down research,” in The Small-Scale Fisheries Guidelines. Global Implementation. MARE Publication Series, Vol. 14, eds S. Jentoft, R. Chuenpagdee, M. J. Barragán, and N. Franz (Cham: Springer). doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-55074-9_29

Sall, A., Deme, M., and Diouf, P. S. (2006). L’évaluation des Emplois dans les Pêcheries Maritimes Sénégalaises. Dakar: WWF-WAMER et PRCM, 44.

Smith, H., and Basurto, X. (2019). Defining small-scale fisheries and examining the role of science in shaping perceptions of who and what counts: a systematic review. Front. Mar. Sci. 6:236. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00236

Williams, S. B., Hochet-Kibongui, A.-M., and Nauen, C. E. (eds) (2005). Gender, Fisheries and Aquaculture: Social Capital and Knowledge for the Transition Towards Sustainable Use of Aquatic Ecosystems. / Genre, Pêche et Aquaculture: Capital Social et Connaissances Pour la Transition Vers L’utilisation Durable des Écosystèmes Aquatiques. / Género, Pesca y Acuicultura: Capital Social y Conocimientos Para la Transición Hacia el Desarrollo Sostenible. / Género, Pesca e Aquacultura: Capital Social e Conhecimento Para a Transição Para um Uso Sustentável dos Ecosistemas Aquáticos. ACP-EU Fish. Res. Rep. 16. Brussels: European Commision, 128.

Keywords: Small-Scale Fisheries Academy, Gender Action Learning System (GALS), visual thinking, collective action, governance, SDG 14, Senegal

Citation: Nauen CE and Arraes Treffner MF (2021) Translating SSF Guidelines Into Practice With the Small-Scale Fisheries Academy. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:730396. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.730396

Received: 24 June 2021; Accepted: 03 November 2021;

Published: 29 November 2021.

Edited by:

Michele Barbier, Institute for Science, Ethics, FranceReviewed by:

Ouafae Kafaf, The Ministry of Agriculture, Maritime Fisheries, Rural Development and Water and Forestry, MoroccoRafael Tubino, Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Copyright © 2021 Nauen and Arraes Treffner. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Cornelia E. Nauen, Y2UubmF1ZW5AbXVuZHVzbWFyaXMub3Jn

Cornelia E. Nauen

Cornelia E. Nauen Maria Fernanda Arraes Treffner

Maria Fernanda Arraes Treffner