- 1Faculty of Environment, School of Environment, Enterprise and Development (SEED), University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada

- 2Rekhi Centre of Excellence for the Science of Happiness, Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur, Kharagpur, India

The survivability of the small-scale fishery and dried fish production in Indian Sundarbans, despite increasing threats posed by climate, environmental, economic, and policy drivers, suggests that they possess certain unique strengths and capabilities. One thread of these strengths is connected to the fact that Sundarbans’ fishery system is strongly anchored in the values and beliefs of the local fishing communities. There is, however, limited empirical information available on the prevailing individual and collective attitudes, expectations, traditions, customs, and, above all, values and beliefs that strongly influence local fishing communities of Sundarbans. This manuscript aims to address this gap by drawing on qualitative data to (1) map the nature of values and beliefs associated with the Sundarbans’ Sagar Island fishing communities who are engaged in small-scale fishery and dried fish production; and (2) highlight the contributions of values and beliefs to the small-scale fishery and dried fish production systems of Sagar Island. Our study reveals that historical factors such as the patriarchal and patrilineal system prevalent in the Indian Sundarbans as well as the current drivers, including environmental and social-economic changes, create inconsistent values and beliefs among male and female members of its society. Issues around values and beliefs are heavily influenced by social-ecological realities comprising material, relational and subjective dimensions. They can range from being strictly personal to largely community-oriented as they are shaped by realities of gender, class, power dynamics, and politics. Values and beliefs are fundamental to human perception and cognition but often get neglected in mainstream literature covering human dimensions of resource management. Our research adds weight to the theoretical and place-based understanding of the contributions of values and beliefs to the small-scale fishery and dried fish production systems. We learn from the case study that values and beliefs can act as mirrors, reflecting the current as well as future realities of small-scale fisheries and dried fish production systems and provide important directions for sustainability and viability of the entire social-ecological system that hosts this sector.

Introduction

Fisheries are complex social-ecological systems (SESs) (Berkes, 2011) that often involve multiple actors from various cultural groups. Small-scale fisheries (SSF) is an important sector that makes valuable contributions toward the society and human wellbeing (Weeratunge et al., 2014; Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, 2015; Johnson et al., 2018, 2019). SSF is generally characterized as a dynamic and evolving sector employing labor-intensive harvesting, processing, and distribution technologies to exploit marine and inland water fishery resources (Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, 2003). SSF contributes two-thirds of the global fish catch destined for direct human consumption, and provide critical contributions to food security, poverty alleviation, and local and national economies (Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, 2015). This suggests that SSF does not operate in isolation from the rest of the fishing industry, from other sectors, or society as a whole. Rather, it is a part of a larger social-ecological system, which can even be termed a “system within systems,” interwoven with economic, social, and cultural life in local communities (Jentoft et al., 2017). There is no global definition for SSF because they are highly diverse and include low-technology, low-capital fishing methods, rudimentary fish processing and marketing, as well as modernized and sophisticated gear and technology that fishers own and operate (Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, 2015). For instance, Indian fisheries remain far from homogenized as they span multiple social and economic classes and communities of fishers and fishery workers, and most of them could fall under the umbrella adjective “small-scale” (Jadhav, 2018). SSF provides support to over 90 per cent of the 120 million people occupied in fisheries globally and contributes to two-thirds of the global fish catch destined for direct human consumption, thereby making critical contributions to food security, poverty alleviation, and local and national economies (Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, 2015).

In comparison to highly modern, industrial fisheries of the Global North, SSF in developing part of the world involves less capital, smaller boats, lower-tech gears, fishing nearer to shore, community economic orientation, traditional governance, and production dedicated to local consumption needs (Jadhav, 2018). Although the activities within SSF can be conducted full-time, the prevalence of part-time or just seasonal employment is more in practice. The employment peaks in the months of the year when fishery resources are more abundant or available in coastal and offshore areas but shifts to other occupations during the off-season. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations (2008) has reported that the number of full-time fishers has declined in the past three decades while part-time fishers have grown quite rapidly, especially in Asia. This trend clarifies the deteriorating conditions of the ecosystems that host SSF and a corresponding decrease in availability and actual catch of fish by people involved in this sector. These changes have tremendous impact on the human dimension of SSF and DF production.

A large share of fish produced in developing countries such as India is preserved using simple techniques such as sun drying, salting, fermentation, and smoking (collectively referred to as ‘Dried Fish’ (DF) in this manuscript and forms a sub-sector within SSF). Much of the catch is dried, as facilities for freezing and transporting frozen fish remain poorly developed, particularly as many fish landing sites are in remote locations. It is interesting to note that the nutritional value of dried fish remains unchanged and sometimes even retains higher quality standards compared to fresh fish (Faruque et al., 2012). The high nutritional value of dried fish, their typically low prices, and their ready divisibility into small portions make them widely and readily available and of great importance to the nutritional intake of the fishing communities who cannot afford other sources of nutrition.

Considering the limited resources small-scale fishers possess in terms of investment capacity and fishing gears, dried fish production comes as one of the most preferred livelihood opportunities improving the viability of the entire SFF. Two overarching trends are evident from the above understanding of SSF and DF sectors. Firstly, SSF and DF production provide critical contributions to nutrition and food security, poverty alleviation and livelihoods, and local and national economies, especially in developing countries (Béné et al., 2007; Berkes, 2015). They (SSF and DF production) substantially add to the overall human security, especially to the economic, cultural, social, and political aspects of the poor and marginalized sections of society who remain involved in SSF and related activities. Secondly, despite these contributions, most SSF and DF communities are economically marginalized, increasingly vulnerable to climate and environmental change, and, until recently, have remained largely invisible in global and national policy discussions (Berkes, 2015). Consequently, an estimated 5.8 million fishers in the world reportedly earn less than $1 per day (Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, 2015).

In terms of gender roles in SSF, women and men often perform different roles in fisheries labor. SSF employ more than 90 percent of the world’s capture fishers and fish workers, about half of whom are women particularly in post-harvest and processing activities (Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, 2015). Globally, SSF production activities involve an estimated 2.1 million women (±86,000), who mainly target invertebrates from intertidal and nearshore habitats, representing approximately 11% of small-scale fishers worldwide and within that catches by women were found to be highest in Asia, estimated at over 1.7 million tons per year (±523,000) (Harper et al., 2020). Women also make up a significant portion of the workforce in dried fish, which is a sub-sector within SSF (Hossain et al., 2015; Belton et al., 2018; Medard et al., 2019). Women play a crucial role in supporting their livelihoods, cultures, and local economies (e.g., income, employment, food, social ties, and cultural values) through their engagement in SSF and DF production (e.g., production, processing, and marketing) (Galappaththi et al., 2021). Paradoxically, serious concerns have been raised regarding the sustainability of SSF and also about the people associated with it. First, the ecological integrity of the fisheries on which these sectors rely, is threatened, resulting in fish shortages and price shocks (Khan et al., 2002). Second, many producers and workers belong to marginalized groups (widows, refugees, religious minorities, and lower castes, for example) and are vulnerable to various forms of exploitation and exposure to health and personal safety risks due to poor working conditions (Belton et al., 2018). Third, the utilization of dried fish to produce feeds for growing aquaculture and livestock industry seem to divert fish away from human food chains (Funge-Smith et al., 2005).

These trends expose the simultaneous presence of both vulnerabilities and prospects for viability within the SSF and DF production sectors (Nayak and Berkes, 2019). Together with increasing threats due to climate, environmental, economic and policy drivers, these trends have created a global crisis in SSF (Paukert et al., 2017; Satumanatpan and Pollnac, 2017). Despite persistent neglect and the onslaught of marginalization, the survivability of many SSF and DF systems can be an outcome of certain strengths and forms of capabilities which fishers and DF producers of the region possess. One thread of these strengths is connected to the fact that SSF and DF systems are strongly anchored in local communities, and they reflect a way of life (Gatewood and McCay, 1990; Onyango, 2011) which in turn is strongly influenced by the prevailing traditions, customs, and value and belief systems. The pursuit of a good life, or living well, is shaped primarily by the values fishers practice. Also, one’s socially recognized capabilities to achieve what is being valued decide the degree of wellbeing (Johnson et al., 2018). It is precisely for this reason, the concepts of wellbeing and values are receiving considerable attention in terms of defining alternatives to the highly problematic ecological and social effects of human activities in the Anthropocene (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA), 2005; Rockström et al., 2009; Hicks et al., 2016). This manuscript aims to explore further the role of values and beliefs in the small-scale fishery and dried fish production systems using the case study of Sagar Island in Indian Sundarbans.

We address an important research gap in our understanding of the social-ecological system encompassing SSF and DF production in the Sundarbans region of India by highlighting the often-neglected perspective of values and beliefs. Values and beliefs are fundamental to human perception and cognition but often get neglected in mainstream literature covering human dimensions of resource management. Although small-scale fishery and fish processing is considered the backbone of the Sundarbans’ economy, it faces some serious problems related to biodiversity, sustainability, and livelihood (Chandra and Sagar, 2003). There is a strong need to bring more human dimensions to understand the Sundarbans’ fishing communities and the kinds of values and beliefs they practice, as they are the ones who possess the capability of saving the world’s largest mangrove forest region (Ghosh, 2015). When reviewed through the prism of the social wellbeing framework, SSF can be seen as embedded within an assemblage of human needs, desires, valuations, and relationships that are often particular to a place (Jadhav, 2018). The topic of SSF and DF production in the Sundarbans, with specific attention to values and beliefs, has not received the research attention it deserves considering the vital contribution it makes to the local economy and society. This manuscript responds to this particular gap by mapping the nature of values and beliefs associated with the Sundarbans’ Sagar Island fishing communities engaged in SSF and DF production and broadly highlights their significance.

Values and Beliefs in Small-Scale Fisheries and Dried Fish Production

Shealy (2016) states that “beliefs and values are at the very heart of why we humans do what we do – and who we say we are – to ourselves, others, and the world at large” (p. 3). Yet, values are not the only predictors of behavior as similar behavior may have different determinants. Indeed, value orientations, combined with capabilities, yield insights into the underlying motivations for choices and behavior (de Vries and Petersen, 2009). It is crucial to acknowledge that people’s values, customs, and traditional knowledge systems offer alternatives and adaptive strategies to strengthen livelihood assets and generate new opportunities during vulnerabilities caused by social-ecological changes (Daskon, 2010). These values are crucial for rural communities to recover from vulnerable situations by enabling them to adapt through the use of traditional skills, knowledge, practices, norms, etc., that are passed from generation to generation (Daskon and Binns, 2010).

“Values” are enduring conceptions of what human beings see as preferable and influence their choice and action (Brown, 1984). They are assumed to affect an individual’s beliefs, perceptions, and behavior in various ways. Schwartz (1994) defines values as “desirable goals, varying in importance, that serve as guiding principles in people’s lives” (p. 88). On the other hand, beliefs are more specific than values, as they typically refer to specific domains of life (Collins et al., 2007). Fishbein and Ajzen (1977) define beliefs as statements indicating a person’s subjective probability that an object has one or more attributes. For example, one may have beliefs about the role of stakeholders in fisheries management, about one’s behavior, or about the behavior of a government. Compared to values that are more deep-rooted and resistant to change (Burch and Sun DeLuca, 1984), beliefs may be more easily changed in the presence of new and contradictory information or life experiences – for example, fads and fashions in political and social thinking or the influence of a new social circle may change the existing beliefs (Collins et al., 2007).

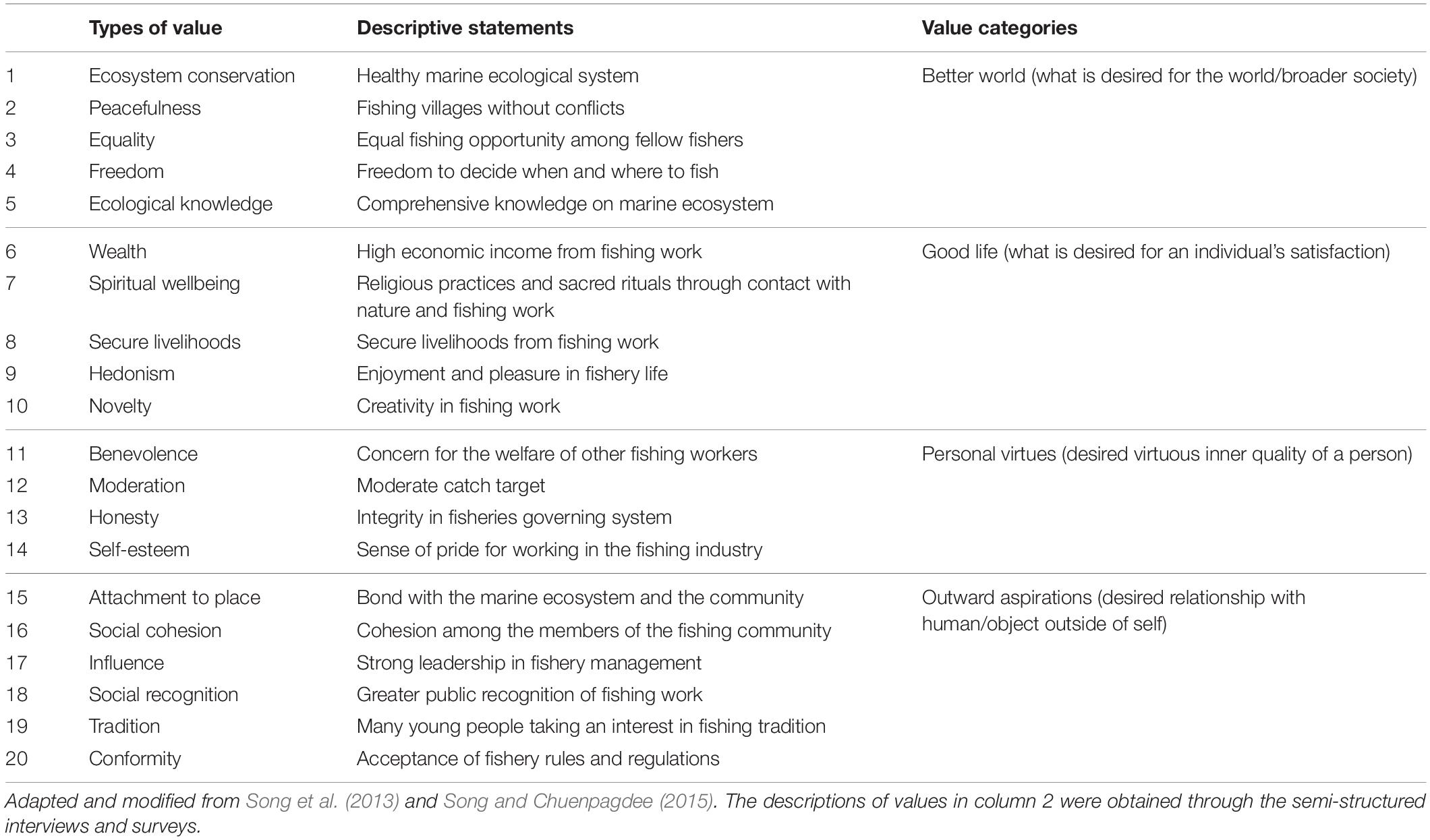

The most common types of values used in social science research are associated with the work of Shalom Schwartz on “universal” human values. Song et al. (2013) and Song and Chuenpagdee (2015) have adapted and modified value schemes introduced in Schwartz (1990, 1992, 1994) to compile a value inventory specific to fisheries governance context (Table 1). Although we are adopting the aforementioned value inventory without any critical evaluation (this can be one of the limitations of this study), one has to keep in mind that this set of value inventory comes out as the most widely discussed and potentially significant when we consider research related to fisheries governance. The other aspect to note is that this value inventory also has its limitation in that it does not cover categories such as gender prejudices, caste hierarchies, and differences even though these notions are strongly present in the value types and categories. Song et al. (2013) categorized these twenty distinct thematic value types into four broader categories according to desired virtues of the society and inner self. They include (1) “better world” which implies what is desired for the world and broader society; (2) “good life” that includes what is desired for an individual’s satisfaction; (3) “personal virtues” which means desired virtuous inner qualities of a person and; (4) “outward aspirations” that includes desired relationship with humans or objects outside of self.

Value theory in social science explains that values are constructed through human action while also motivating human action (Johnson et al., 2018). We try to live consistently with our values while adjusting them according to our lived experiences (Graeber, 2001). Therefore, the question is not only what values are attached to SSF and DF production but also what they mean for the small-scale fishing people and the significance of those values in the viability of SSF and DF production. The present study intends to identify diverse common beliefs and the level of importance for every value held by male and female members of SSF/DF production in Sagar Island through four value categories that are identified by Song et al. (2013) and Song and Chuenpagdee (2015). Through this process, the relations of conflict and congruence among values and beliefs of fishing members will be revealed. According to Schwartz (1970), actions in pursuit of any value can have consequences that conflict with some values while being in congruence with others. In fisheries governance, having high numbers of conflicting values would not only cause the current issues in the governance to persist but would also contribute to lower governability (Song et al., 2013).

Study Area and Research Methods

The Sundarbans, located within 21°32′ to 22°40′N and 88°05′ to 89°51′E, covers an area of approximately 10,000 km2 of which 62% lies within Bangladesh and 38% in India (Islam, 2014) and forms the largest contiguous mangrove forest on earth. The Sundarbans delta provides a physiologically suitable environment with respect to temperature, salinity, and other physiochemical parameters. Therefore, the Sundarbans have been the nursery grounds for nearly 90% of the important commercial aquatic species of the eastern coast of India (Chandra and Sagar, 2003). After agriculture, fishing is the most common means of livelihood (Danda, 2010) for over 4.4 million people residing in the Sundarbans (Census of India, 2011). The estimated percentage of households in the Sundarbans that list “fishing” as one of the family occupations is 11% of the total households inhabiting the area (Sánchez-Triana et al., 2014). This percentage goes up to 60–70% in areas with easy access to rivers (Sen, 2019) like Sagar Island. In the Indian Sundarbans Delta, caste and religious identities are not determining factors of access to resources and opportunities, as verified by a Danda et al. (2011) report. Following the principles of traditional livelihood practices and customary rights, both river and sea fish are considered as “commons” and “collectable” by everyone. The proximity of different religions, castes, and indigenous and immigrant households in the region points toward shared cultural and livelihood practices.

Sagar Island, located on the south-west edge of the Indian Sundarbans, was used as a location to narrow the geospatial scope of this research. Within the broader community of Sagar Island, five districts located in the south and west coastal area of the island were approached for participation, namely Gangasagar, Mahisamari, Dhablat, Beguakhali, and Mayagoalinighat. These districts were selected because of their: (1) geographical position (Sagar Island is in the extreme south-west island of the Sundarbans, and hence its south and west coasts are facing a severe threat from phenomena caused by climate change, including soil erosion, breach of embankments, loss of landmass, and rising sea levels); (2) proximity to the estuary and sea (provide both estuary and marine fishing); (3) famous sacred place (the location of Gangasagar pilgrimage at the meeting point of the sacred Ganges river and the Bay of Bengal; the ashram of Kapil Muni); (4) number of immigrants relocated after the submergence of northern islands; and (5) previously established social networks with “Fishermen Association of Sagar Island” to facilitate the researchers in sampling and providing useful information. After contacting one of the previous researchers working on Sagar Island, we were introduced to a local NGO. The NGO members then established our first meeting with the Secretary of the “Fishermen Association of Sagar Island.” The Secretary acted as the initial informant and connected the researchers to other potential key informants.

Traditionally, fish has a special place in Bengali culture and cuisine. Fish species, especially Rohu (Rui), Hilsa (Ilish), and Pomfret (Pomfret), are sought-after food in West Bengal. Hilsa (Ilish), one of the most valuable and in-demand fish of the Indian Sundarbans, is mainly caught during the monsoon season. While situating the Sagar Island fishery in the context of the Indian food industry, fisheries in India is generally perceived as a sector that is ever-expanding and therefore should act as an ideal livelihood option for fishers. In contrast, the reality is that the island’s fishing communities live in harsh and demanding conditions. In the Sundarbans, the villages are in remote areas, with minimal access to education and health facilities. The accessibility of the island from the mainland, including the market spots, is only possible through waterways by mechanized or non-motorized boats. The remoteness and transportation constraints in most villages are two factors for the region’s poor development.

Primary data collection for the present study was undertaken in two parts. In the first round, a household survey was conducted using a household questionnaire through snowball sampling (i.e., the process by which previous participants identify new participants) covering 45 households. In the second round, 45 fishers/dried fishers (25 males and 20 females) were identified among the households covered in the first round and were interviewed following a semi-structured interview schedule. Further, focus group discussions (n = 2 with a total of 33 participants) were carried out in the study area itself. We followed three-point criteria in shortlisting the participants. For the present study, the respondent must (1) be a legal resident of Sagar Island; (2) practice fishing in the sea, creeks, and estuarine rivers with wooden boats (non-motorized boats and 2-, 4-, and 6- cylinder boats) or homemade Styrofoam floating boards; and (3) be a dried fish producer.

During the surveys, each value was converted into a descriptive statement (Table 1), and then it was put forward for the respondent. The descriptive statements, which reveal what values mean among fishing communities, were derived from explanations of each value provided by Song et al. (2013), Song and Chuenpagdee (2015), and our interpretations based on initial interactions with Sagar Island fishing communities. The questions were translated from English to Indian Bengali language in consultation with a village group and delivered verbally to the participants. Further, to minimize the possibility of meaning getting lost in the translation, a research assistant for the data collection process was selected from the local area commanding language proficiency in both English and Bengali. The primary data was supported by an extensive literature review to define the conceptual and methodological approach. The literature review helped us to (1) extract existing data relevant to case study context (e.g., location, policy, and demographics), theoretical context, and research questions (e.g., values and beliefs, wellbeing, and social-ecological drivers), (2) increase familiarity with the historical background and prevailing culture of the research case, and (3) deductively develop a preliminary framework and context-specific interview and survey questions.

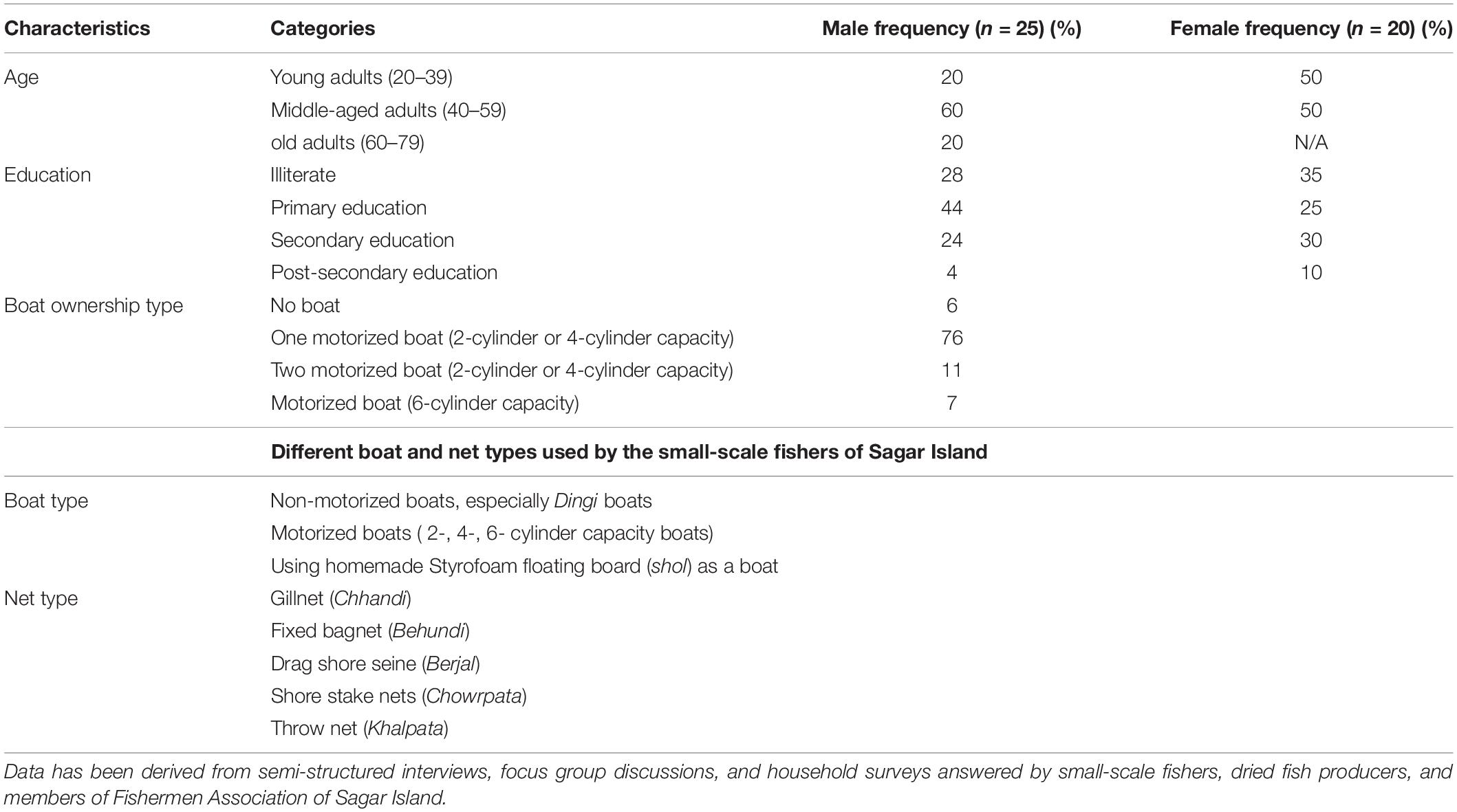

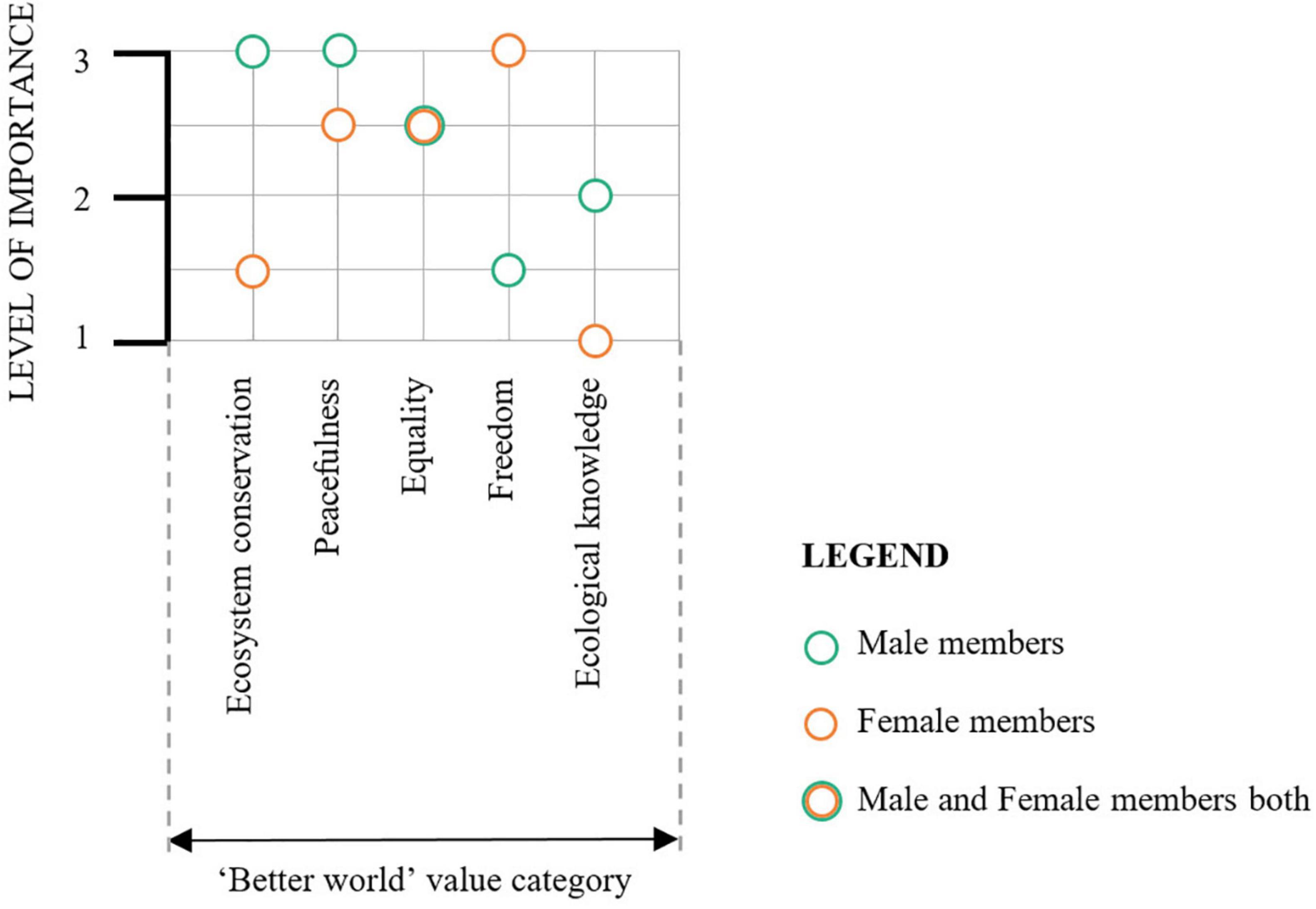

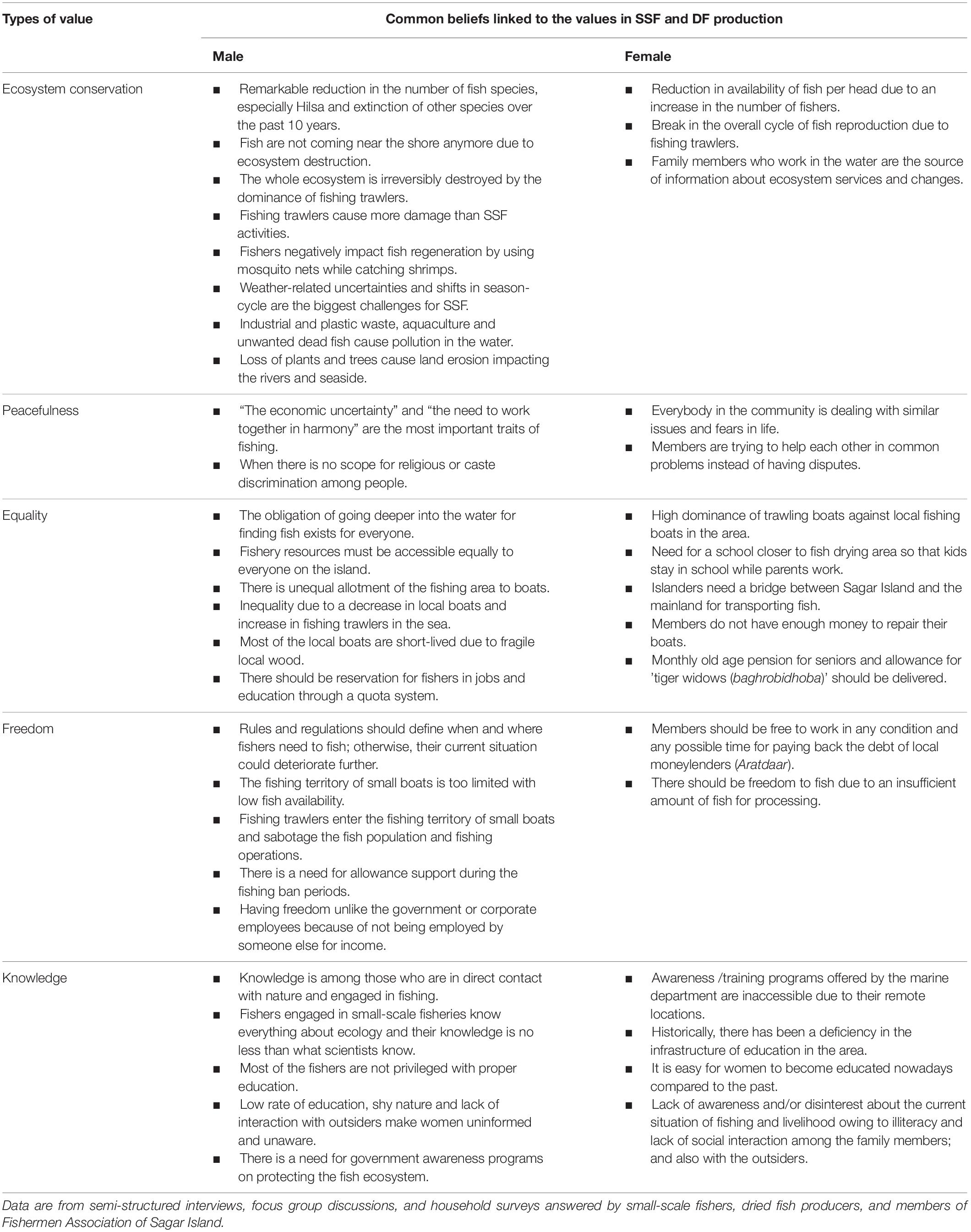

Table 2 demonstrates the socio-economic profile of the respondents. It is good to note that owning a boat on the island does not mean that the owner necessarily is running a fishing business. During the interviews, many participants stated that they alone could not afford the cost of one particular fishing voyage; therefore, they share their boats among family members to offset the cost. Further, fishing is primarily a combined effort, with two to three fishers working together (CARICOM, 2000). In the case of boats with four or less than four-cylinder capacity, the boat captain (i.e., the owner) takes a 50% share from the profit, and the remaining share is divided among the rest of the members. But in the case of 6-cylinder boats, the boat captain takes 60% of the share. During data collection, it was noticed that small-scale fisher households in Sagar Island are also dried fish producers. Also, male members are mainly involved with fishing, and female members are mainly involved with dried fish production (fish drying and processing). In addition, there are different choices male and female fishing members pursue regarding their livelihood and socialization. Therefore, both male and female groups were sampled within each village to gain a breadth of these differences in relation to their values and beliefs. In this research, the semi-structured interview data first underwent a thematic analysis using qualitative coding with the help of NVivo qualitative data analysis computer software. The questionnaire results were quantitatively analyzed using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Inferential statistics (taking data from samples and making generalizations about a population) were attained regarding ranking the most (and least) esteemed thematic values among each male (n = 25) and female (n = 20) fishing community group. The results were coded as 1, 2, and 3 according to the rank they received (i.e., 1 implies “not important”, 2 implies “somewhat important”, and 3 implies “very important”). For instance, it was coded as one if a respondent said that the “honesty” value was not important in terms of its contribution to Sagar Island’s SSF and DF production. Then, the mean values of these codes were acquired by adding all the values together and dividing the result by the number of respondents. The mean values were used to create figures representing the importance hierarchy among the male and female members. These actions have been taken to better compare the value types and emphasize their level of importance. It is also good to note that we have used a grounded approach in this research and presented some noteworthy quotes from the community members to explain their perspective on values and beliefs and also to back up the research findings.

The Diverse Small-Scale Fisheries and Dried Fish Production-Related Values and Beliefs in Sagar Island

“Better World” Value Category

“Better World” value category includes values that are desired for the world/broader society (i.e., universal nature) (Song et al., 2013). They strive to achieve the wellbeing of all people and nature by promoting the principles of conservation, peace, equality, freedom, and knowledge (see Table 1 above). Schwartz (1970) highlights values that support ecosystem conservation, help advocate for equality, and deepen knowledge. These values do not develop in society until people become aware of the scarcity of natural resources and encounter others outside the extended primary group (Schwartz, 2012). Such realization makes them understand that failure to respect these values will lead to chaos and conflicts. Besides, they may realize that failure to protect and conserve the natural environment will lead to the destruction of the resources on which their lives depend (Schwartz, 2012). The values of freedom and knowledge offer the opportunity to ensure that the right people make the right decisions using the right knowledge. The hierarchy of “better world” value types as per their level of importance among the fishing community of Sagar Island is represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Importance hierarchy of “better world” value types in the small-scale fishery and dried fish production of Sagar Island based on the male and female fishers and dried fish producers who judged each value (note that 1 implies “not important”, 2 implies “somewhat important”, and 3 implies “very important”). Data are from household surveys answered by fishers and dried fish producers of Sagar Island.

Male members of the fishing community, who are involved mainly with small-scale fishing rather than dried fish production, ranked “ecosystem conservation” and “peacefulness” as the most important values in the “better world” value category. The strong connections between the ecosystem and community livelihood became visible during the past 5–10 years due to the experience of adverse changes in the ecosystem and the decline in fishers’ income. This tendency of putting more importance on the “ecosystem conversation” is a direct outcome of realization among male fishers that the sustainability of their livelihood (fishing) is solely attached to the ecological balancing of Sagar Island and its natural resources. As two of the fishers acknowledged through statements such as “Unlike my wife, I am in direct contact with the water” and “I speak about the changes in seasonal catch with fellow fishers constantly” that their close contact with their environment and fellow fishers made them aware about the “ecosystem conservation.” It should be noted that most male fishers referred to ecosystem changes as a reason for the decline in their annual income and livelihood situation. Thus, neglect of the conservation values has taken a toll on the economic and livelihood conditions of the fishing community.

Both male and female fishers believed that they were suffering from the lack of sufficient income throughout the year and could not afford conflict among each other. Many of them added that if they lose “peacefulness” in the village, their mental health and livelihood security would be in danger as they will not be able to support each other emotionally or financially during tough times. Historically, Sagar Island communities are known for a rich tradition of community support in times of crisis. They include the ability to lend and borrow money, support in ensuring food security, mutual protection and security such as being rescued while encountering an accident during fishing trips, being there for each other through community-level interactions and socialization, and psychological support while dealing with distress. Each member’s efforts toward maintaining peaceful coexistence have a significant contribution to the value of “equality”. That is why both male and female fishers highly rank the value of “equality” which has its roots in the fisheries being traditionally managed as a commons. A male fisher with 24 years of fishing experience said:

One thing I love about this village is that we all try our best to maintain peace in it. We are mixed! From different places and different religions. But we keep this strong bond of friendship because we have only each other to support in harsh moments. I am aware that in other villages in the region and even in other places in India, people are fighting over their differences which is sad.

(Male, Fisher)

In comparison to the high importance given to ecosystem conservation and peacefulness, fishers accorded low importance to the “freedom” value, i.e., freedom to engage in fishing activities. There are concerns regarding multiple restrictions imposed on fishing activities (by the government) due to which 54% of the male members (n = 25) expressed that there should be clearly demarcated rules and regulations to guide when and where to fish; otherwise, the current confusing situation could push them into conflicts with each other. In their view, the current regulations should be updated to match the recent ecosystem changes in the region because they can no longer catch sufficient fish within their fishing territories. Regulating the incessant operation of fishing trawlers, delivering allowance during the fishing ban period, and access to diverse livelihood options were the most mentioned demands (from the fishing community to the government). Fishers further believed that their preferences should be given priority when it comes to where and when to fish, mainly because of their minor impacts on the ecosystem compared to fishing trawlers.

There were diverse views on the importance of “ecological knowledge” as a value. Male fishers illustrated medium importance to “ecological knowledge”. Those members who put low importance on the value of “ecological knowledge” attributed their reason to their poor economic conditions such as this:

There will not be much of a difference if one knows everything about ecology since the knowledge will not change the desire of human beings to survive. Even if we harm the ecosystem by catching infant fishes, we are bound to catch them for our survival. Besides, it is fishing trawlers that are harming ecosystem the most, and the government is equally guilty for not banning them. Our business will disappear in the near future if they [fishing trawlers] continue like this. Knowledge seems to have no value here.

(Male, Seasonal fisher)

Female members are active mainly in fish processing (Figure 2) and catching shrimps and small fishes in the riverside. Therefore, their responses showed little emphasis on “ecosystem conservation” and “ecological knowledge” values simply due to lack of knowledge about and direct involvement in topics related to the fisheries ecosystem. Regarding women’s knowledge of the fisheries ecosystem, weak inter-gender (between males and females) interactions among community members and family members were observed during the field visits. It was found that women’s lack of knowledge about the fisheries ecosystem is connected to social deprivation and taboos rather than their “lack of interest”. A leader of the Women Self-help Group and a local secretary of the Fishermen Association describe their point of view in the following statements:

Figure 2. Female members are participating in dried fish processing. They use the broom on a special net for flipping fish (Photo credit: Abdar Mallik).

Involvement in dried fish production has led women to be aware of many issues in society. One of the main improvements in this society is when almost all these women encourage their daughters to get a proper education. Securing enough funds to support kids’ education has become one of the main reasons for these women to get involved in fishing. Despite all of these, most women prefer to have minimum contact with outsiders due to social deprivation.

(Female, Leader of Self-help Group)

The average rate of education among women is very low in this locality. Women are very shy to go out and interact with people coming from outside the village or from a foreign country. For example, when an American couple visited the place last year and tried to call women for a meeting to offer some help, no women came to attend it. Lack of interaction is the main reason behind their lack of awareness. These women do not know the current status of their business and the factors behind the recent changes.

(Male, Local Secretary of Fishermen Association and active fisher and dried fish producer)

“Freedom” is a strongly desirable value among 94% of the female respondents (n = 20). They stressed the importance of both “freedom” and “equality” by referring to the insufficient amount of fish they get for processing due to decreasing catch these days. They have identified “equitable fishing among fellow fishers” and “freedom in deciding when and where to fish” as solutions to this problem. When it comes to the “ecosystem conservation” value among female members, only a few of them were able to explain the recent ecosystem changes and the necessity of having a healthy marine ecological system. Thus, there seems to be a disconnect between the actors and the activities of fishing and fish processing, which is significantly gender-based. Some female members were educated and had jobs other than dried fish production, like teaching in public school, heading a local self-help group, or representing women in the Fishermen Association. The rest mentioned that whatever information they have about the recent ecosystem changes is from their husbands or sons who go fishing regularly.

The common beliefs linked to the “better world” value category among male and female members of SSF/DF production in Sagar Island have been listed in Table 3. It shows that most female members lacked awareness regarding the environment and the possible damages caused by intensive fishing or non-compliance with the fisheries rules. This lack of awareness among the female members and their status in the fisheries sector is inherently linked to the predominantly patriarchal and patrilineal system in the society of Sundarbans that causes the low average rate of literacy and high level of social deprivation among female members.

Table 3. Common beliefs related to the “better world” value category among male and female members of SSF and DF production in Sagar Island.

“Good Life” Value Category

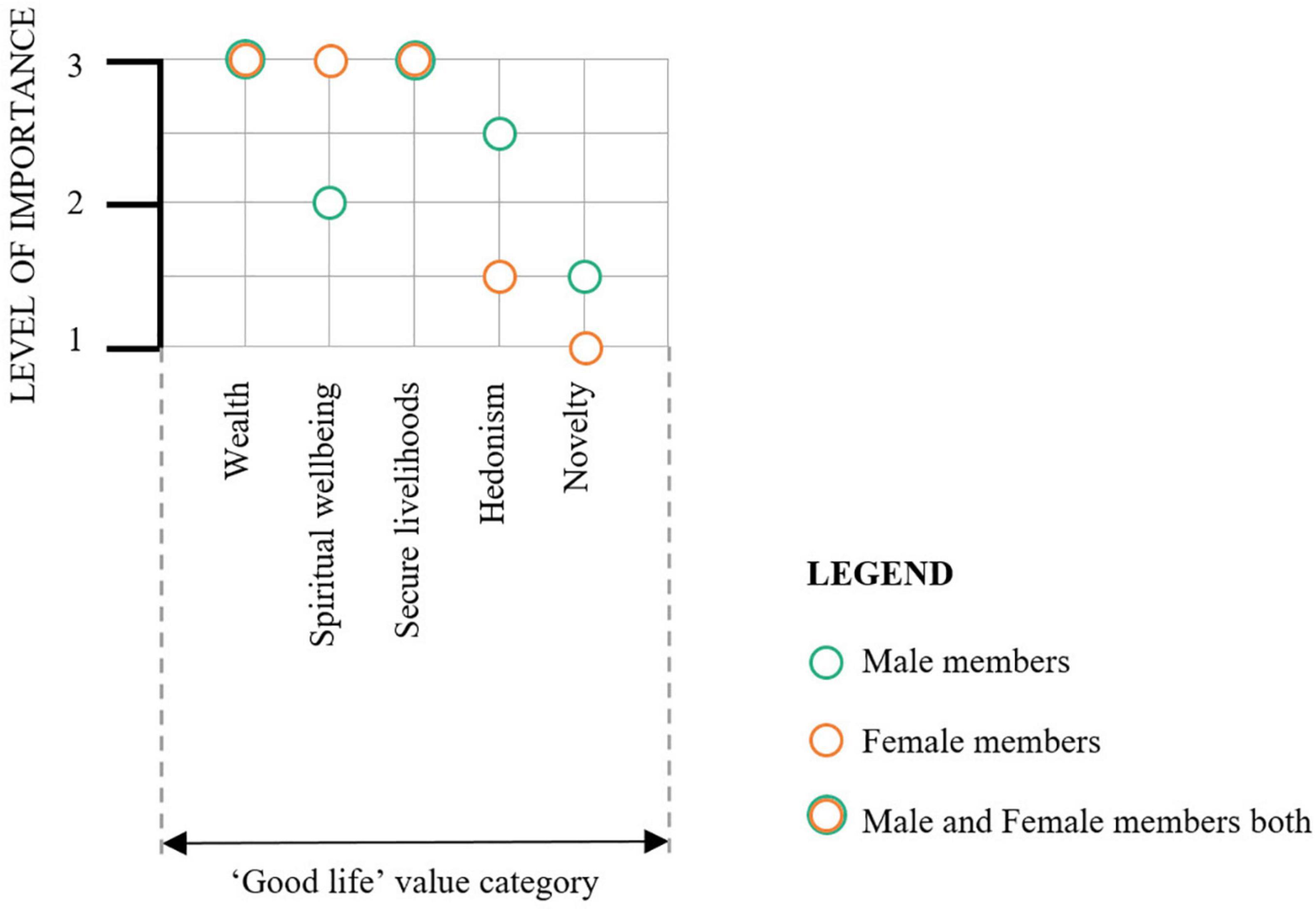

The values under the “good life” category emphasize the attainment or preservation of a dominant position over people and resources within a social system, together with pleasure or sensuous gratification for oneself (Schwartz, 2012; Song et al., 2013). Schwartz (2012) states that although pursuing power and achievement values such as “wealth” may harm or exploit others and damage social relations, they help motivate individuals to work for group interests. Other researchers acknowledge that “what a person values materially and the way he/she perceives the question of “how he/she is doing” depends on his/her relationships with others and the ideas that frame this social bonding” (White and Ellison, 2007; Deneulin and McGregor, 2010; Coulthard et al., 2011). In addition, pursuing values that are derived from pleasure and satisfaction (e.g., spiritual wellbeing) does not necessarily threaten positive social relations, unlike in power values (e.g., wealth) (Schwartz, 2012). The importance hierarchy of “good life” value types among the fishing community of Sagar Island as per their level of importance is represented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Importance hierarchy of “good life” value types in the small-scale fishery and dried fish production of Sagar Island based on the male and female fishers and dried fish producers (note that 1 implies “not important”, 2 implies “somewhat important”, and 3 implies “very important”). Data are from household surveys answered by fishers and dried fish producers of Sagar Island.

In the “good life” value category, “wealth,” and “secure livelihoods” were accorded the highest importance by both male and female members of the fishing community in Sagar Island. Such preference can be gauged by respondents’ statements such as “without having it, you cannot even think about other things in life” and “more than being the most important thing for fishers, it is better to say that it is the most fundamental value for everyone on earth to survive”. Also, male members stressed on the vital connection of these values to their livelihoods; an example includes:

The current situation has made us more financially and socially deprived than before. Most of us are in debt to local moneylenders. We need to show that we are active in the business (fishing) in the hope of paying off our debts. That is why I have not sold my boat, and I cannot even think of moving somewhere else.

(Male, Former fishing business owner and a monthly hired fisher at present)

During the field visit, it was found that the current economic situation of fishery households was determined primarily by the amount of debt they owe to local moneylender (Aratdaar) and their ability to pay it off. Likewise, the debt and its associated contract acted as undesirable glue holding the fishers/dried fish producers attached to the profession and the place. Life satisfaction of individuals is also dependent on different factors such as where do they stand in comparison to their past situations and; in comparison to the people around them. As is visible from the below-mentioned two separate statements, one from a former fishing business owner and the other from a daily wage laborer:

Since I lost my business and boat because of my debt, I started working as a daily wage laborer. My family’s health has deteriorated considerably after I joined the current job. My wife started to consume medicines to improve her mental health. Without these medicines, she is unable to do daily chores and take care of our children.

(Male, Former fishing business owner and a monthly hired fisher at present)

I am grateful to have fishing as my livelihood. It has been a reliable source of income for many years. I have been able to feed my children and support their education thanks to it.

(Male, daily wage laborer)

These two diametrically opposite perspectives of the same situation suggest that all the activities, relations, and emotions prevalent within the community are controlled directly or indirectly by the sudden changes in the economic situation of the households. For example, lack of life satisfaction and deterioration of mental health was noticed much more among those who had lost their family business and recently became daily wage laborers than those who have been daily wage laborers right from the beginning. It implies that the adaptation to a sudden financial setback is harder for the households that are used to having a good economic status.

When it comes to “spiritual wellbeing”, religion holds a special place in the lives of male fishers of Sagar Island. Every activity in the community, starting from buying new boats, going to sea in the morning, or opening of the fishing season, is preceded by a religious ritual, either individually or in the group. These practices provide a sense of shared risks and an acknowledgment of divine powers for fishers and their families. Among Hindus, who form the majority in Sagar Island (Census of India, 2011), protection, prosperity, and success are expected in a reciprocal relationship with the deities based on offerings and prayers. A sense of fear or subservience to these divine powers can also be observed. During the interviews, male members stated that following traditional beliefs and rituals is part of their routine activities; hence its importance is unquestionable, but they cannot perceive it as the most important value. A fisher explained:

Before the beginning of every fishing season, we repair the boats and re-color them. We start this process about 10 days before the beginning of the season. After boats get repaired and put in the canals, we do Ganga puja on them. We also perform a separate puja at the start of each voyage. Other than that, the Fishermen Association organizes a big Ganga puja every year where all the fishers and their families take part together. The whole celebration goes on for 5–6 days when they arrange numerous cultural programs and social activities apart from the main puja.

(Male, Fishing business owner)

From the field interactions, it has been observed that among the fishers, who had to go against their religious norms to embrace a lifestyle more in accordance with their economic activities, this process of prioritizing profession over faith creates psychological obstruction – e.g., feeling guilty, stress, anxiety, and depression. This pattern can be aligned with Schwartz’s (1970) value theory: actions in pursuit of values have practical, psychological, and social consequences. One male fisher explained his mental state by referring to his religious belief below. In this example, we can see practically that choosing an action that promotes one value (e.g., vigorously pursuing wealth) may contravene or violate a competing value (e.g., sacrificing religion). Hence, the person who faces the choice may sense that such actions are psychologically dissonant.

I am Hindu and follow Vaishnavism [A Hindu denomination in which killing any living things, mostly animals, is forbidden, and the followers are normally vegetarian]. I have been in this business for 50 years now, but I am still facing psychological guilt for catching fish (thereby killing them) every time I go to the water because of my religion.

(Male, Fisher, and farmer)

When asked about the importance of “spiritual wellbeing” among females, 74% of them (n = 20) associated the reduction in fish or the rise in accidental deaths while fishing with religious beliefs. They believed that a fisherman killing a mermaid in one of the neighboring states made deities furious and led to the catch’s decline. This is a key finding to understand how people rationalize the events for which they have no logical explanation. Further, seeking refuge and blessing for life’s protection and economic prosperity by wearing Maduli or Tabeez (objects which are believed to have magic powers for protection or bringing luck) was practiced mostly among the women whose husbands were working in the sea. Such tendency among female members can be a reflection of perceiving deities as manifestations of power – to protect, destroy, or prohibit – rather than of sacredness only for the sake of spiritual elevation. Overall, female fishers gave higher importance to “spiritual wellbeing” than males. A female fisher illustrated her high rank to the “spiritual wellbeing” value through her statement:

I am very concerned about the health of my husband and my son. I do puja [a Hindu manner of ritual offering] every day, and I wear Maduli to keep them safe from danger. I believe that killing a mermaid in the neighboring state brought many adversities to the lives of the fishing community. This season we are experiencing a much greater number of accidents and a lesser number of fish.

(Female, Dried fish producer)

When asked about “hedonism”, male members declared the relatively high importance of “hedonism” value in fishery livelihood, but only 45% of them (n = 25) felt complete enjoyment and pleasure toward fishing. The respondents gave explanations for their feelings by phrases such as “addiction of fishing”, “socializing with others”, “very laborious job”, “causing severe health problems”, “hatred toward the water”, and “feeling compulsion toward continuing it”. The reasons behind enjoyment among fishers were briefed in Box 1 (the sequence does not reflect priority). On the other side, female members perceive “hedonism” value as an almost unimportant value in the fishery. Almost all of them indicated that they could not comment on “hedonism” value as they have been active in DF production out of compulsion. Although they could not answer how “hedonism” value would (not-) matter in their career, they related some of their illnesses to fish processing activities.

Box 1. Reasons for holding enjoyment and pleasure feelings in fishing; stated by the fishing community.

(1) Having an addiction to fishing and going into the sea.

(2) The possibility of securing a bounty catch in one of the voyages to gain a sudden profit.

(3) Getting to know new people with similar hobbies and concerns.

(4) Holding a job that feeds the family and enables kids to continue their education.

(5) Working with other family members in the same job.

(6) Working independently in the job without having an employer.

The “Novelty” value garnered little importance among male and female members.

Although male members mentioned a few alternative methods for fishing, like using Styrofoam board (shol) (Figure 4), both male and female fishers stated that there is no scope for novelty and innovative thinking in the fishery. The common beliefs of the “good life” value category among male and female members of SSF/DF production in Sagar Island have been listed in Table 4. The informants’ responses show that values and beliefs related to “spiritual wellbeing”, “hedonism”, and “self-esteem” hold different levels of importance for male and female fishing members.

Figure 4. Using Styrofoam board (Shol) for fishing. A small motor is attached to the bottom part of the board for riding it by overcoming the waves coming toward the shore. A long rope holds the board from the shore and prevents it from getting lost inside the water (Photo credit: Sevil Berenji).

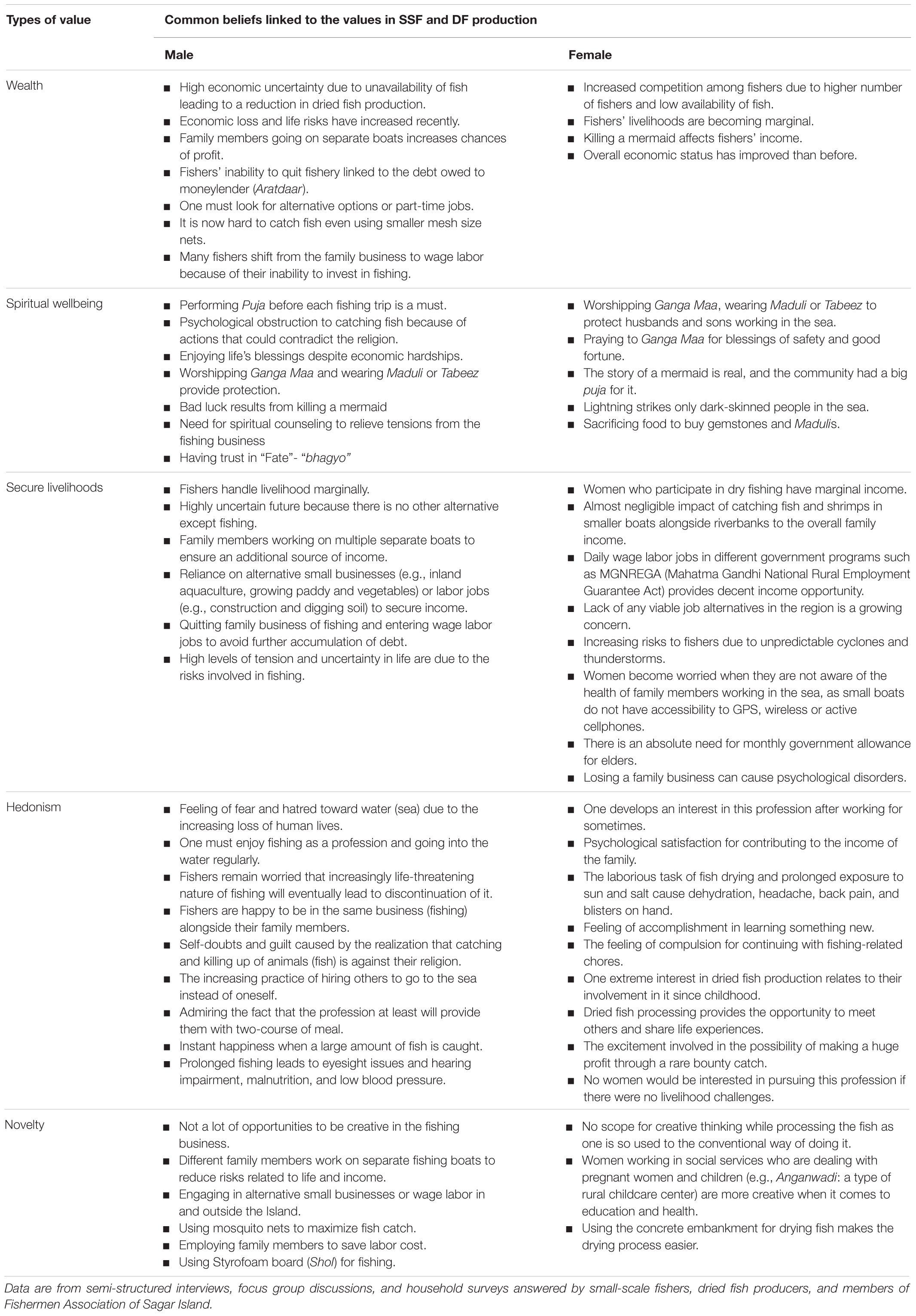

Table 4. Common beliefs related to the “good life” value category among male and female members of SSF and DF production in Sagar Island.

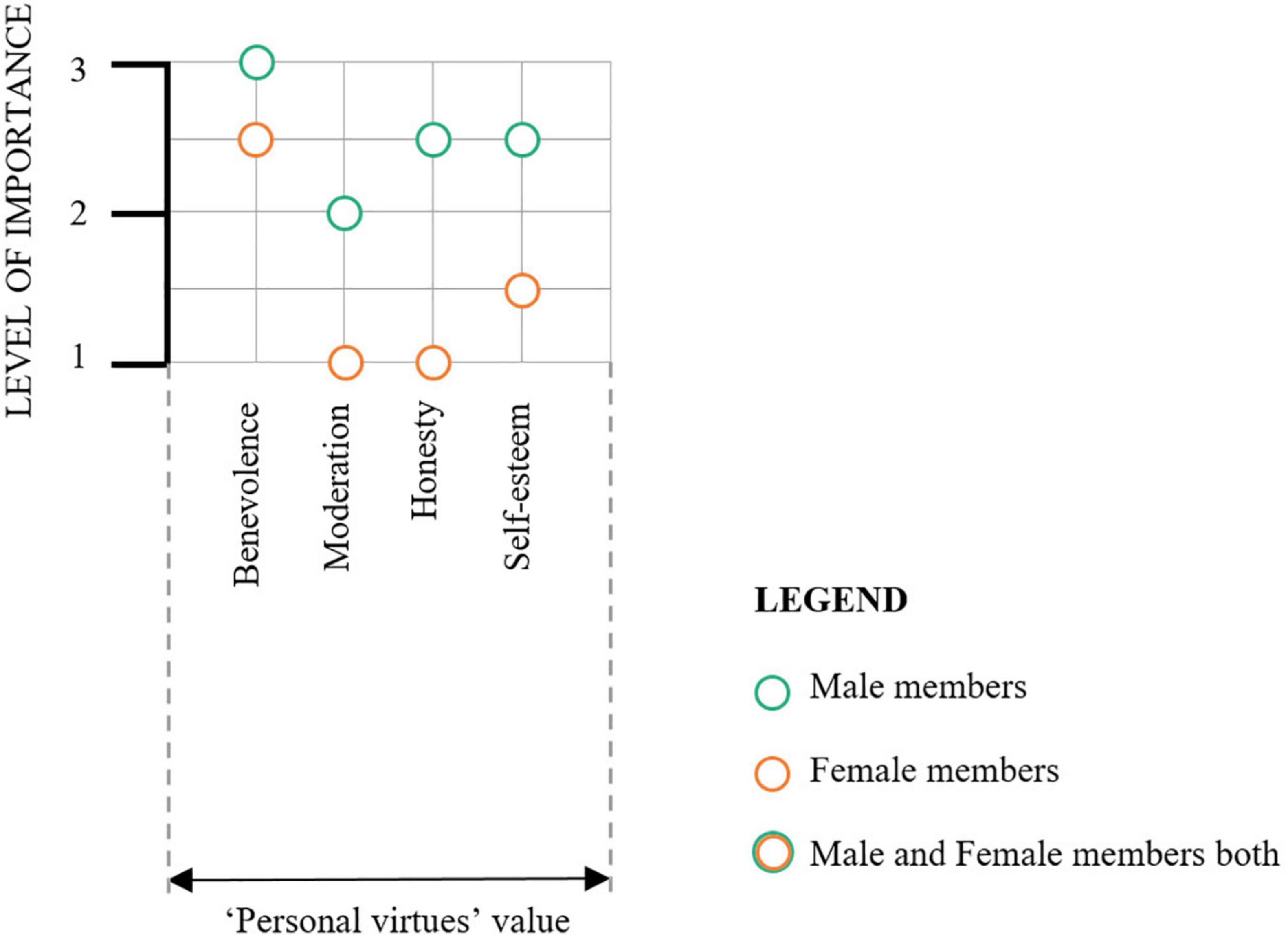

“Personal Virtues” Value Category

The “Personal virtues” value category comprises values derived from preserving and enhancing the welfare of those with whom one is in frequent personal contact, within the family and other primary groups (Schwartz, 2012; Song et al., 2013). According to Schwartz (2012), the high importance of values related to “personal virtues” derives from the centrality of positive and cooperative social relations in the family where the initial and continuing value acquisition of an individual takes place. Values in this category promote the desired righteousness of a person by striving for benevolence, moderation, honesty, or self-esteem. Both the “better world” and “personal virtues” value categories have the tendency of paying attention to the welfare of others, but the “personal virtues” category concerns the welfare of the “in-group” whereas the “better world” category concerns the welfare of all – even outside the primary group. The hierarchy of “personal virtues” value types among the fishing community of Sagar Island as per their level of importance is represented in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Importance hierarchy of “personal virtues” value types in the small-scale fishery and dried fish production of Sagar Island based on the male and female fishers and dried fish producers who judged each value (note that 1 implies “not important”, 2 implies “somewhat important”, and 3 implies “very important”). Data are from household surveys answered by fishers and dried fish producers of Sagar Island.

In the “personal virtues” value category, “benevolence” value is perceived as an incredibly important value among male and female fishers. During the interviews, male members explained the events related to rescuing the lives of fellow fishers or helping each other financially. Female members also acknowledged the culture of emotional and financial support among the community members. Speaking about “moderation” and “honesty” values, male members declared relatively high importance to them in fisheries while recalling the damages caused through incessant fishing by trawlers and unregulated fishing by small-scale fishers (e.g., using mosquito nets for fishing).

Unlike male members, the female respondents have indicated lower importance to “moderation” and “honesty” values. They believed that they are getting a moderate amount of catch most of the time because of less availability of fish in the sea; therefore, there is no use in taking “moderation” value as an important value because that is the new normal. When it comes to integrity in the fisheries governing system (“honesty” value), most of the female fishers were not fully aware of the fishery rules and regulations (e.g., fishing ban period, prohibition of using concrete embankments known as “chatals” among locals for fish drying, banning of trawlers) in the region to make anything out of the “honesty” value. They stated that their employers had merely informed them or family members that the government bans them from performing fish processing on concrete embankments along the shore as the chemicals used by them in fish processing cause deterioration to the embankments.

When it comes to the “self-esteem” value, male fishers confirmed that it has relatively high importance in fisheries through statements similar to those in “hedonism” value (e.g., proud of providing food and education for family members). Some fishermen believed that to survive in such a harsh profession, one should derive strength from the positive aspects and feel proud. These findings suggest that this pride aspect of fisheries leads to male members feeling like an entrepreneur working independently without having to serve under an employer and acts as a motivator against the harsh nature of fishing. On the other side, female respondents mentioned that they are grateful for finding an added source of income by working in DF production, as they can contribute to the family’s economy and be able to socialize with outsiders. But they do not put high importance on holding “self-esteem” value through their job because they do not share the proud feeling (unlike their men) due to the “necessity aspect” of their job. Furthermore, they stated that their social status is enhanced compared to their previous generations, but they still feel socially deprived because of not getting proper education during their childhood. These results show that despite enhancement in women’s social status in the community because of their involvement in DF production, the impact of social deprivation is long-lasting, which is enough not to let women perceive the profession as a source of self-esteem or hedonism value. Common beliefs of the “personal virtues” value category among male and female members of SSF and DF production in Sagar Island are shown in Table 5.

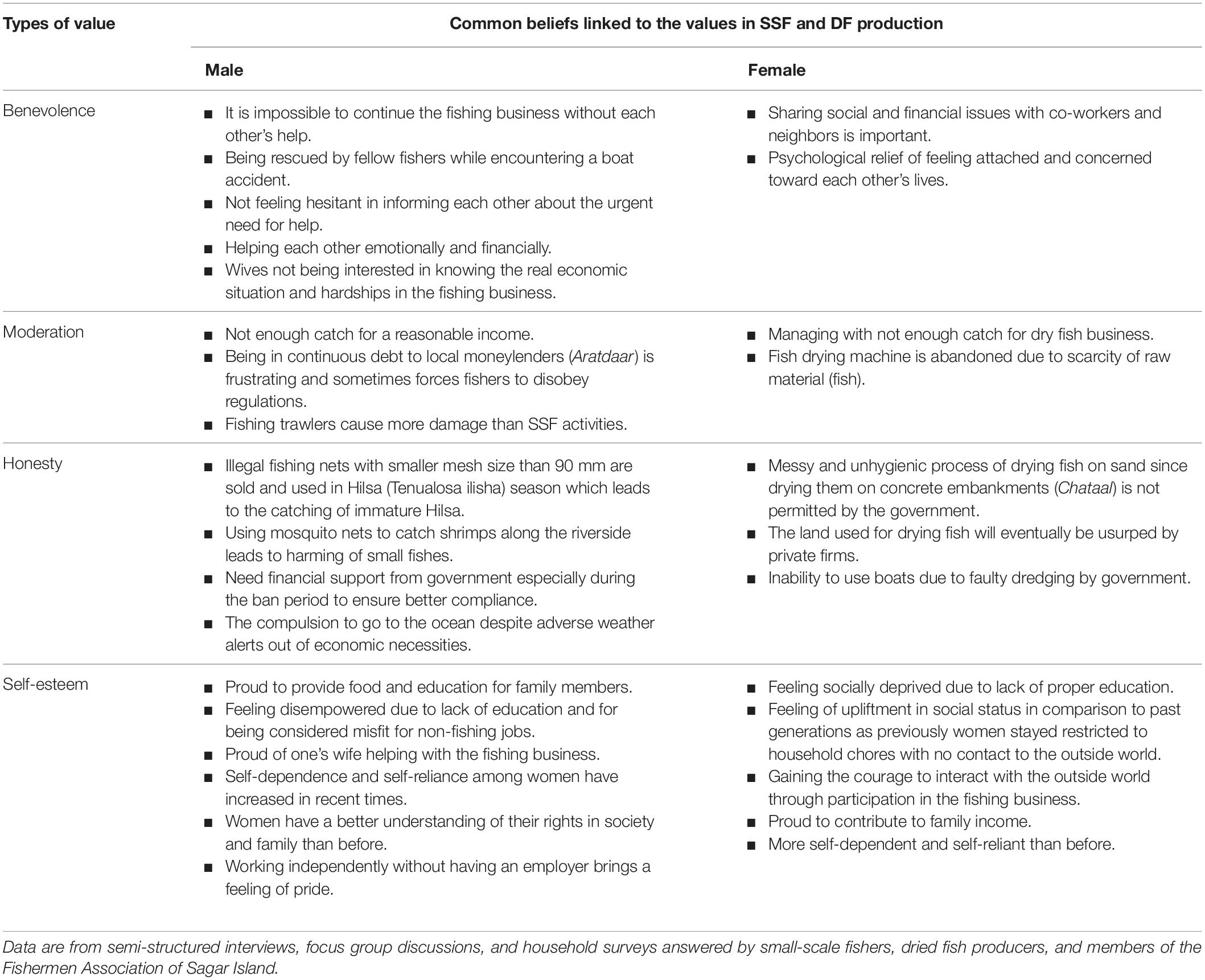

Table 5. Common beliefs related to the “personal virtues” value category among male and female members of SSF and DF production in Sagar Island.

“Outward Aspirations” Value Category

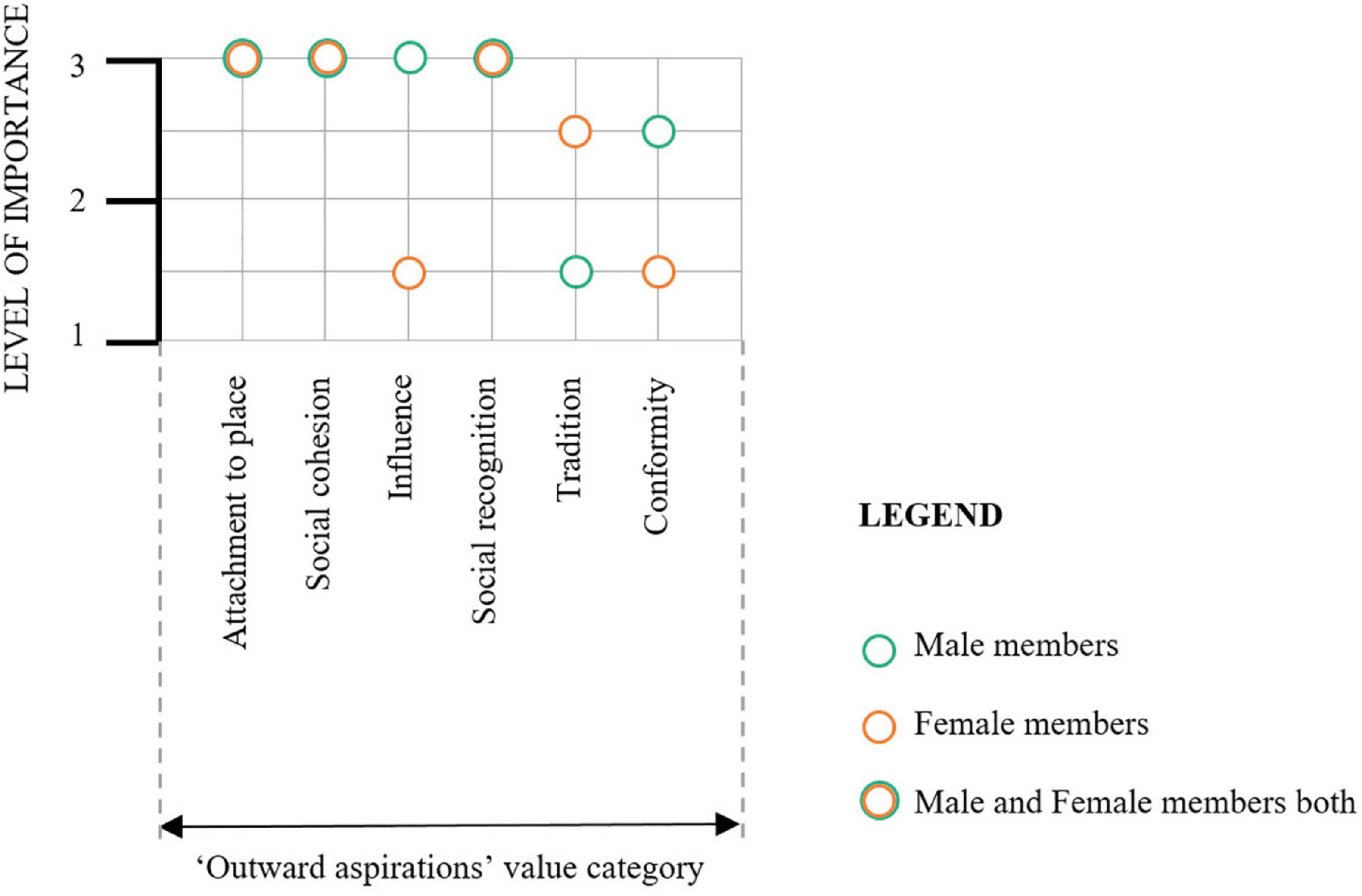

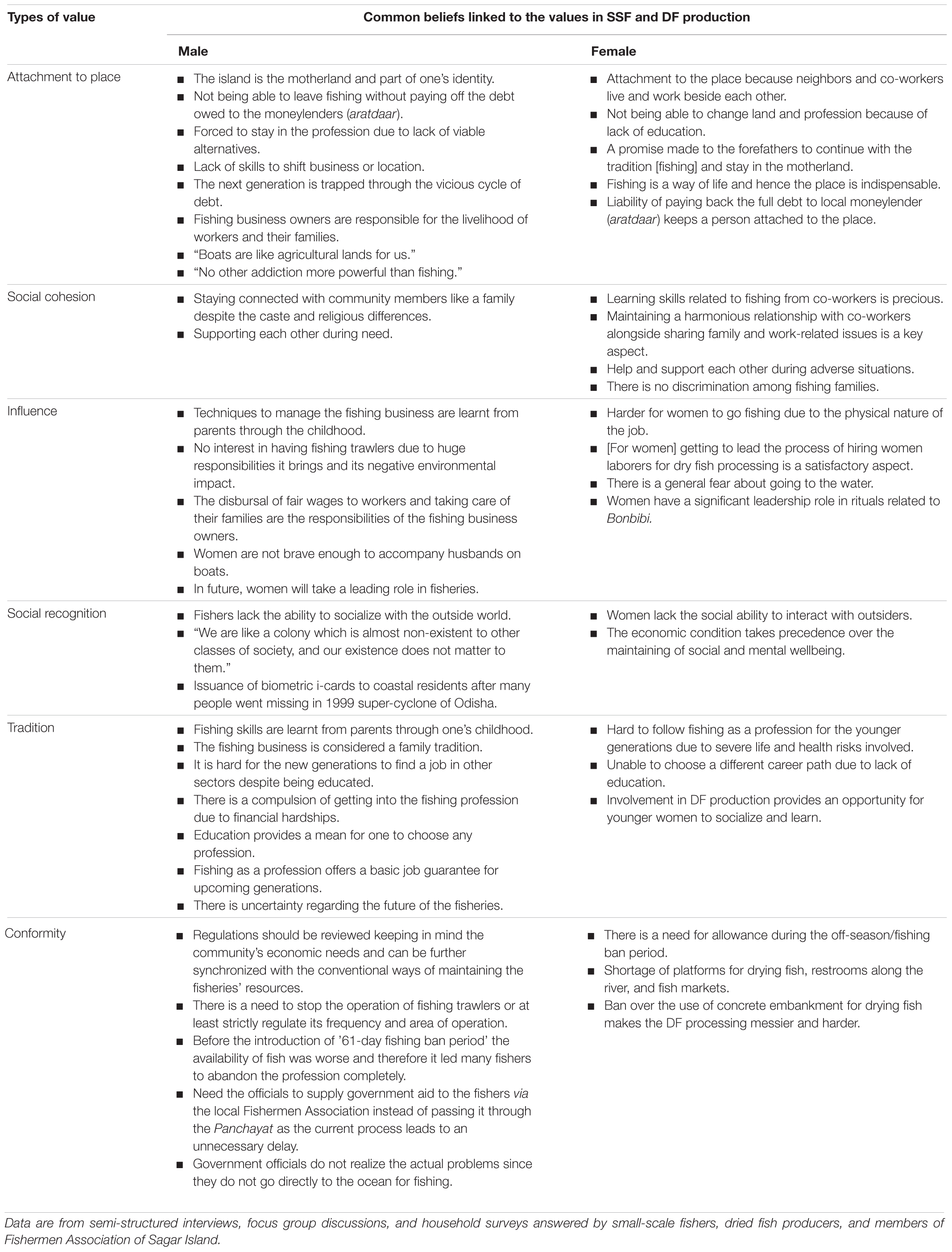

The values in the “outward aspirations” category signify the desired relationship with outer beings that guide interactions with fellow humans or objects outside of self (Song et al., 2013). They are derived from restraining actions and inclinations that might disrupt and undermine group functioning by violating social expectations and traditions (Schwartz, 2012). Groups everywhere develop some practices, symbols, ideas, and beliefs representing shared experience and fate. These traditions symbolize the group’s solidarity, express its uniqueness, and contribute to its survival (Parsons, 1951; Durkheim, 1954). During field visits, it has been found that the unavailability of alternate livelihood and the debt trap are two of the most dominant factors in keeping the individuals continue with fishing and stay attached to the place. Moreover, these adversities have motivated the communities to put off their religious and caste differences and maintain high social cohesion and unity. The hierarchy of “outward aspirations” value types among the fishing community of Sagar Island as per their level of importance is represented in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Importance hierarchy of “outward aspirations” value types in the small-scale fishery and dried fish production of Sagar Island based on the male and female fishers and dried fish producers who judged each value (note that 1 implies “not important”, 2 implies “somewhat important”, and 3 implies “very important”). Data are from household surveys answered by fishers and dried fish producers of Sagar Island.

“Attachment to place”, “social cohesion” and “social recognition” values were judged to be the highest in terms of importance among both male and female fishers. The top status of these values can be exemplified by respondents’ explanations such as “this is the main factor of fisheries’ survival in this place” and “this is the most desired thing for all of us”. The study reveals that the fishery of the island has been a “character of the community” and that all other practices, ideas, identities, values, and beliefs take shape based on it. Brookfield et al. (2005) conclude, “fishing is the glue that holds the community together” and “the community understands and makes sense of the world from a perspective that is garnered from years of involvement with the fishing industry” (p. 56). Therefore, it is no surprise that the fishers on the island see the fishery as an inseparable part of their lives and demand greater public recognition for fishing activities. The importance hierarchy shows the “attachment to place” value as one of the most important values contributing to the fishery of the island. Jacob et al. (2001) suggest that strong attachment toward fishing supports the sense of belongingness in a region. This is one reason why members perceive “social cohesion” as an extremely important value. The high importance of “social cohesion” is reflected through the community’s existing harmony among the followers of different faiths.

Throughout the Sundarbans history, Muslims have been respectful to Maa Ganga – a Hindu goddess (Figure 7: left), and, in the same way, Hindus have shown their acknowledgment toward Bonbibi’s Muslim parentage (Figure 7: right). The rich tradition of syncretism (the combination of different religions, cultures, or ideas) has a long history in many parts of India, and Bengal is no exception (Chacraverti, 2014). However, the fact that the Sundarbans’ syncretism has been successful in achieving the union among its residents is even more noteworthy. Through the interviews and discussions in the field, it has been found that the community’s economic challenges, uncertainties, and problems have carried them toward positives such as strong union and solidarity. A male fisher’s explanation regarding the importance of high social cohesion in the fishery is as follows:

Figure 7. The idols of Ganga Maa (goddess of Ganges) [left] and Bonbibi (goddess of the forest) [right] (Photo credit: Sevil Berenji).

In this business [fishing], the most important traits are economic uncertainty and the need to work together. So, there is no scope for religious discrimination among co-workers from different faiths. We share the same issues as well as grievances during fishing. Considering that we do not get any significant help from the government, of course, we need to help each other.

(Male, Former fisher and dried fish producer at present)

There is a remarkable difference in how the male and female members perceive the prevalence of the “influence” value. Male members ranked “influence” as one of the most important values in the fishery by explaining the essentiality of leadership in fishery management. Most females did not perceive the high importance of “influence” value because most of them stated that a sense of leadership could not be an important part of their fishing activity as they are mostly assigned non-leadership roles (most of the female informants are daily wage laborers). “Laborers cannot be leaders” is a prevalent view among female fishers, which is also linked to the deep-rooted patriarchal system in the community. Male members believe that leadership and decision-making processes should be handled by them both in society and households as it ensures better management. These kinds of gendered notions (e.g., excluding women from meaningful participation) are the outcome of the prevailing patriarchal and patrilineal structures, institutions, and practices in Sundarbans. Most of the activities concerning the overall community are controlled by men, including the ownership rights of the property. This mechanism makes the women feel they are “lesser members of the society”, submerging their social leadership potential in the process and giving rise to inconsistent values among male and female members.

It was observed that being a business owner or a crew member does not change the perception of male fishers regarding the importance of “influence” value. Crew members acknowledged how having a skillful boat leader can positively affect their income as they are paid according to the amount of catch rather than daily or monthly wages. One fishing business owner explained:

Although I consult with my wife and elder son in decision-making, I am the one who makes the final call. Males manage this business mostly, and women like my wife and daughter-in-law help during the processing phase. Their help provides extra safeguard to the family’s financial situation as the money required for hiring extra labor gets saved.

(Male, Fishing, and DF production business owner)

The constant dangers to assets and lives mainly due to sudden changes in weather conditions and rampant industrial fishing in the area have changed people’s beliefs regarding the future of fisheries and the relevance of transferring their fishing skills on to the next generation. Male fishers stated that the number of fishers had increased recently; therefore, the fishery in the region is suffering from the problem of having a higher number of fishers and a reduced pool of catch. As a result, male fishers do not give high importance to the “tradition” value because of an uncertain future for younger generations when it comes to the fishery. This could imply that the tradition of transferring the family business from one generation to the next is losing centrality that may have existed sometime in the past within the fishing community. Among male respondents (n = 25), 60 per cent do not want their kids to continue the fishing business mainly because of high life risk and economic uncertainties. Only 23 per cent of them, mostly family business owners, wanted their next generation to continue fishing. The rest, 17 per cent, declared that they are open to whatever their kids prefer. On the other hand, “tradition” was strongly desirable for female members. They stated that involvement in DF production has made them socialize more within society and has further enhanced their chances of getting a proper education. It shows that DF production on the island has indeed broken up some patriarchal traditions in society. Female members illustrated their high rank to the “tradition” value by stating that many young women are taking an interest in the tradition of post-harvest fishing activities through statements such as:

Our social status has improved a lot compared to the generation of our mothers and grandmothers. Earlier, there was no chance of getting an education for women, and they used to sit at the corner of the house throughout the year. But now, we can go outside and participate in dried fish production. This also gives us an opportunity for social interaction with the outside world. Therefore, young women develop enough interest and courage to join this profession.

(Female, Dried fish producer)

Table 6 exposes the common beliefs around the ‘outward aspirations’ value category among male and female members of SSF and DF production in Sagar Island.

Table 6. Common beliefs related to the “outward aspirations” value category among male and female members of SSF and DF production in Sagar Island.

Key Insights, Policy Recommendations, and Possible Future Directions

Drawing on qualitative data, we examined the nature of values and beliefs associated with the Sundarbans’ Sagar Island fisher communities. We documented contributions of values and beliefs to the social and ecological aspects of small-scale fishery and dried fish production systems. Our study confirmed that Sundarbans’ fishery system is strongly anchored in the values and beliefs of the local fishing communities, even though there are differences at times in how they are perceived and practiced across social, economic, and gender groups. This finding significantly contributes to the limited empirical information available on how values and beliefs strongly influence local fisher communities and their fishing practices in the India Sundarbans. We used Song et al. (2013) framework on twenty thematic value types in fisheries and four broader categories according to desired virtues of the society and inner self. Data collected from fishers and dried fish producers in the Sagar Island helped generate a comprehensive understanding of their values and beliefs in four areas: (1) “better world” which implies values that are desired for the broader society of the fishers and dried fish producers; (2) “good life” that includes values contributing to the satisfaction and fulfillment in individual life, and supports their state of being; (3) “personal virtues” that facilitate desired virtuous inner qualities of a person to contribute to the fishing society and fisheries; and (4) “outward aspirations” that includes values necessary for maintaining a relationship with humans or objects outside of self. Together, these categories of values provide a nuanced understanding of small-scale fisheries and dried fish production systems. Based on our findings and with support from value theory, we provide several insights, policy recommendations, and possible future research directions on values and beliefs in SSF and DF production systems similar to the Sundarbans (Sagar Island).

Small-scale fisheries and DF production-related values and beliefs are materially, relationally, and subjectively oriented. These three aspects are reflected through the four value categories outlined by Song et al. (2013) and Song and Chuenpagdee (2015). They are also strongly connected with the concept of wellbeing, defined as “a state of being with others, where human needs are met, where one can act meaningfully to pursue one’s goals and where one enjoys a satisfactory quality of life” (Gough and McGregor, 2007, p. 1). They discuss three dimensions of wellbeing: the material, relational, and subjective aspects of human life, and experiences from the Sagar Island confirm that values and beliefs are integrally linked to these wellbeing dimensions. The material dimension involves the question of how fishers’ tangible and physical needs, expectations, circumstances shape values and beliefs. The relational dimension addresses the role of relationships and interactions fishers depend on to derive values and beliefs. The subjective dimension of values and beliefs explains fishers’ feelings and gives meaning to their personal and inner meanings in how they perceive and make sense of life. Thus, these three dimensions shaped the nature of values and the level of wellbeing and the interconnections between the two within the SSF and DF production context of the Sundarbans. Values and beliefs help fishers think of the material, relational, and subjective limits that are useful to pursue their “state of being” and “quality of life” (Coulthard et al., 2011; Fischer et al., 2015; Nayak and Berkes, 2019).

Values and beliefs are influenced and shaped by social-ecological realities. They are as much socially driven as they are ecologically influenced. Sagar Island fishers reported that they drew their values from both social and ecological sources. The use of a social-ecological systems (SES) perspective is quite effective in linking the social and ecological components that work together to facilitate SSF and DF production-related values and beliefs. An SES perspective is understood as one that builds on the premise of a highly interconnected system of humans and the environment (Berkes, 2011). A social-ecological system is seen as coupled, interdependent, co-evolutionary (Turner et al., 2003; Glaser, 2006; Kotchena and Young, 2007), multi-level and nested, both vertically and horizontally, and includes the human (social) and the biophysical (ecological) subsystems (Berkes et al., 1998; Berkes, 2011). These subsystems have multiple components ranging from the cultural, economic, and political aspects within the social domain and the geochemical, physical, biological, and hydrological features within the ecological domain, which are integrally linked in a continuous process of complex interactions, and they influence each other (Nayak, 2014). The churning that takes place in this entire process tends to facilitate the formation and continuation of values and beliefs. Further, the material, relational and subjective dimensions of values and beliefs, as discussed above, are deeply rooted in both social and ecological realities: (1) Material dimension is linked to income, livelihoods, asset, shelter, food, and other physical resources; (2) Relational dimension includes social relations, family, dignity, social obligations, institutions, rules and norms that guide relationships; and (3) Subjective dimension relies on security, peace, freedom of choice and action, knowledge, sense of control and power, identity and norms (Narayan et al., 2000; Dasgupta, 2001; Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA), 2005; White, 2010; Coulthard et al., 2015).

Values and beliefs are driven by power and politics. Power is often an invisible but dynamic force in how values within SSF emerge, are held, and practiced. Regarding values and beliefs, power exposes itself through social relations and institutional hierarchies, the positions held by actors within the society, and the language and narrative expressions used. The tremendous potential in connecting the discussions about values and beliefs to the narratives of power should not be underestimated (see Nayak et al., 2016). In this context, important questions to further examine include: (1) Who wins and who loses in the tussle for whose values and beliefs take precedence? (2) Are there premediated efforts to put in place certain kinds of values to guide SSF and DF production at the cost of others? (3) Whether it is possible that certain sections of the SSF society can make deliberate attempts to steer the discourse and practice of values for their selfish interests? These questions suggest that outcomes of values and beliefs are driven by power and political dynamics and can have disproportionate effects on existing social relationships and interactions. Consequently, a key reflection by fishers and dried fish producers on Sagar Island was about possible ways to accommodate diverse views, opinions, and perceptions of values.

It is important to point out here that the values and beliefs perceived and used in the context of SSF in Sundarbans are gender-differentiated in nature. In simple words, men and women in Sagar Island hold quite different views about their values and beliefs regarding SSF and DF production, and also of the factors influencing these perceptions. These differences are not often conflicting in nature but mainly result from their respective social, economic, and political positions in society and overall exposure to the social-ecological realities of SSF and DF production. For example, while male members were fully aware of the value of ecosystem conservation and its vital connection to their livelihoods, most female members were unsure about the recent changes in the ecosystem and the urgent need for its conservation. This difference in value perceptions involving resource and ecosystem conservation as a critical element of small-scale fisheries and dried fish production processes have been primarily attributed to physical proximity and day to day interactions of male members with the fisheries natural system and the opportunity to observe what is going on with the ecosystem and its impact on fish catch. In contrast, women in Sagar Island do not engage in fishing activities directly. Most of them have never actually come in direct contact with the place “where fish lives” (the ecosystem of fish). Factors such as low average rate of literacy, lack of socializing outside the household, and in some cases, weak relationship within the household, along with more historical and deep-rooted structures like the prevailing patriarchal and patrilineal social order, have also been attributed to differences in value perceptions and beliefs. Despite these differences in values and beliefs between male and female fishers, values pertaining to wealth, secure livelihood, attachment to place, social cohesion, and social recognition were recorded as most important to both.

Gender differences and gender relations discussed in the case study of this research are outcomes predominantly influenced by the existing patriarchal and patrilineal socio-cultural construct (structures, institutions, and practices) of Sundarbans. Men control fishing activities, set the societal rules, and own household property and assets. As a result, women’s position in the fishing society has remained weak and their roles subordinate to men, thereby restricting their leadership and decision-making potentials. Our study recorded that many women fishers in the Sundarbans experience social and economic deprivation, lack of control over income and assets, limited access to resources and opportunities, all of which contribute to the existing inconsistencies in the values and beliefs among male and female members of the society. However, there are also some exceptions that were noted in our study in Sagar Island where the predominant role and socio-economic engagements of women in dried fish production is not consistent with the deeprooted patriarchal traditions. Moreover, many fishermen also confirmed that they often consulted women in their households in making major decisions. These experiences in Sagar island of the Sundarbans align with findings of recent studies that emphasize women are more likely to become transformational leaders as compared to men (Eagly et al., 2003).

With regard to policy implications, several of our key findings provide further directions: (1) The increasing loss of life and economic opportunities experienced by Sagar Island’s small-scale fishers and dried fish producers has made community members realize the need for ecosystem conservation. This realization is prominent among those who are under the direct influence of the changes taking place and experience it first hand; (2) The differential awareness between male and female fishers about ecosystem conservation, its connection with their livelihoods, and the change processes impacting the fishery is linked to their levels of direct interaction with the fisheries ecosystem. For example, male fishers who go to the sea frequently were able to articulate the changes taking place and the need for conservation, whereas women were somewhat unsure about such changes; (3) Levels of knowledge and awareness among men and women regarding the environment, ecology, economy and society surrounding the fishery were also related to their levels of literacy, extent of socializing with others outside of their households, and in some cases, weak relationships within the households; (4) Most female fishers associated the reduction in the number of fish or the rise in accidental deaths to religious beliefs as a way to rationalize the events for which they lacked logical explanations due to no direct interaction with the fishing areas; (5) Most fishing and processing activities, relations, and emotions prevalent within the SSF community are controlled directly or indirectly by the changes in the economic situation of the households; (6) The prevalent economic uncertainties, challenges, and problems have led the community toward positive responses such as building strong unions and social solidarity; (7) A critical reflection by fishers and dried fish producers on Sagar Island was about possible creative ways to accommodate diverse views, opinions, and perceptions of values and ways to respond to their imposition and dominance; and (8) Prevailing patriarchal and patrilineal structure in the society of Sundarbans create inconsistent values among male and female members of the society.

Small-scale fisheries and dried fish production have long been a key sector in the Sundarbans and a prominent part of Sagar Island’s social-economy and ecological history. We can no longer ignore the mutual contributions between this sector and the values and beliefs as they tend to have shaped each other. The differences in values and beliefs of stakeholder groups and variations within the same group have been identified as a crucial impediment in resource conservation, planning, and implementation (Vennix, 1999; Wondolleck and Yaffee, 2000; Dietz et al., 2003). Values and beliefs are multidimensional and can be significantly context-specific. Our experience in Sagar Island confirms that they are inherently linked even though values are more long-term, philosophical, non-compromisable, non-negotiable, non-alterable, whereas beliefs can be comparatively short-term, practical, subject to negotiations and alterations. Within SSF and DF production, the former is often held at group and community levels, and the latter remains in practice at the levels of an individual, family, or small group. Thus, values and beliefs can range from being strictly personal to largely community-oriented. They act as mirrors that reflect the current as well as the future realities of SSF and DF production and provide important directions for the sustainability and viability of the entire social-ecological system that hosts this sector.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available due to Ethics approval restrictions. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to SB (c2V2aWxiZXJlbmppQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==).

Ethics Statement

The study involving human participants was reviewed and received ethics clearance through the University of Waterloo Office of Research Ethics (ORE) (ORE #41043). The participants provided their verbal informed consent to participate in this study. Informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

SB designed and conceptualized the research, conducted the data collection, performed the data analysis, and led writing and revising. PN provided the advice on design, conceptualization of research and data analysis, contributed to the writing, revised the manuscript, and supervised the research. AS supported the data collection, transcription of interview recordings and reviewing and writing specific sections. All authors contributed to the substantively to the manuscript and the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding