- 1Duke University Marine Laboratory, Division of Marine Science and Conservation, Nicholas School of the Environment, Beaufort, NC, United States

- 2International Whaling Commission, The Red House, Cambridge, United Kingdom

Bycatch is the leading global threat to cetaceans, with at least 300,000 cetaceans estimated to be killed each year in fisheries. Regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs) are key actors in global fisheries management, including bycatch reduction, but their role in cetacean bycatch management is often overlooked. The primary mandate of RFMOs is to manage fisheries of target stocks, but many of their Convention Agreements call for addressing bycatch of threatened and protected species in their fisheries, including cetaceans. We reviewed 14 RFMOs to understand their current cetacean bycatch management efforts. We developed twenty-five criteria for best practices in cetacean bycatch management to understand efforts made by each RFMO, grouped into five categories: 1) general bycatch governance; 2) observer coverage; 3) quantitative bycatch limits; 4) data analysis and transparency; and 5) mitigation efforts. Collectively, based on our application of these criteria, RFMOs scored highest in “data analysis and transparency” (average=0.74) and lowest in setting “quantitative bycatch limits” (average=0.15). Overall, RFMOs have passed few binding conservation and management measures focused on cetacean bycatch, particularly compared to those addressing the bycatch of seabirds and sea turtles; the few existing measures are primarily focused on bycatch in purse seines. Notwithstanding the United Nations (UN) large-scale drift gillnet ban (46/215) on the high seas, only one RFMO has passed a management measure specifically focused on cetaceans and gillnets, widely recognized as the gear type posing the highest risk to cetaceans. No measure in any RFMO specifically addresses cetacean bycatch in longlines. We provide recommendations to the RFMO community to encourage progress on this critical issue, including leveraging other recent policy developments such as the adoption of the 2021 UN Food and Agriculture Organization Guidelines to prevent and reduce bycatch of marine mammals in capture fisheries and implementation of the U.S. Marine Mammal Protection Act Import Provisions.

1 Introduction

A critical component of sustainable fisheries management is managing the incidental capture of non-target species, commonly known as bycatch (Alverson et al., 1994; Reeves et al., 2013). The mobile nature of fish stocks and fisheries, coupled with geopolitical realities of managing bycatch across jurisdictions, make bycatch an inherently complex issue (Lewison et al., 2011; Harrison et al., 2018; O'Leary et al., 2020). Bycatch is one of the largest global conservation threats to marine megafauna (Lewison et al., 2004; Lewison et al., 2014; Phillips et al., 2016) and is recognized as the most significant threat to marine mammals on a global scale (Lewison et al., 2004; Read et al., 2006; Reeves et al., 2013; Lewison et al., 2014). Substantial data gaps remain regarding the magnitude of global cetacean bycatch (Lewison et al., 2014), but the best available evidence suggests that more than 300,000 cetaceans are killed as bycatch each year (Read et al., 2006).

Many fisheries pose some level of risk to marine mammals. In summary: longlines pose a risk to odontocetes that depredate catch and bait (Clarke et al., 2014; Werner et al., 2015; Fader et al., 2021); coastal trap fisheries pose a risk for some baleen whales (e.g. Read et al., 2006; Pace et al., 2014); some purse seine fisheries have a long history of high cetacean bycatch in certain regions (e.g. Hall, 1998; Ballance et al., 2021); and fish aggregating devices (FADs) can interact with or entangle marine mammals (Escalle et al., 2015; IOTC-IWC, 2021). Gillnets, however, are recognized as the most perilous gear type for cetaceans (e.g., Read et al., 2006; Kiszka et al., 2009; Reeves et al., 2013; Brownell et al., 2019; Anderson et al., 2020). The slow life histories of cetaceans (i.e, long lifespans, slow growth, and low fecundity) increase the potential for adverse effects of bycatch on their populations (Lewison et al., 2014).

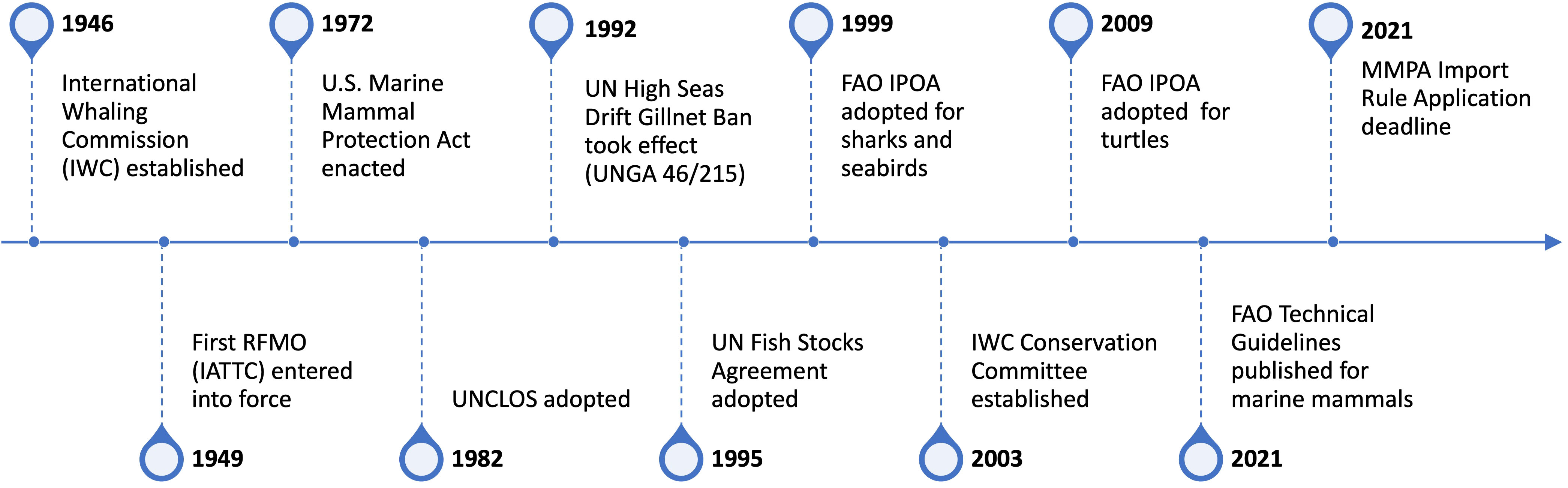

Bycatch has gained increased attention in the international policy arena over the past several decades through identification of bycatch reduction measures, and other efforts (Figure 1) (e.g. FAO, 2021; Lenfest Ocean Program, 2022). For example, the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS) calls for Parties to reduce bycatch through a variety of recommendations in Resolution 12.22 (Convention on Migratory Species (CMS), 2017). The International Whaling Commission has established the Bycatch Mitigation Initiative (IWC BMI), which aims to raise awareness of cetacean bycatch and available solutions, build capacity, and work to reduce bycatch through multi-disciplinary solutions (IWC, 2021). These institutions offer a variety of frameworks to address cetacean bycatch and have made significant progress in recent years, but neither the IWC or the CMS have a mandate to manage fisheries, so their work on this issue must be undertaken in partnership with national governments and other regional bodies to maximize efforts.

Figure 1 Timeline of major international fisheries and marine mammal governance and agreement actions.

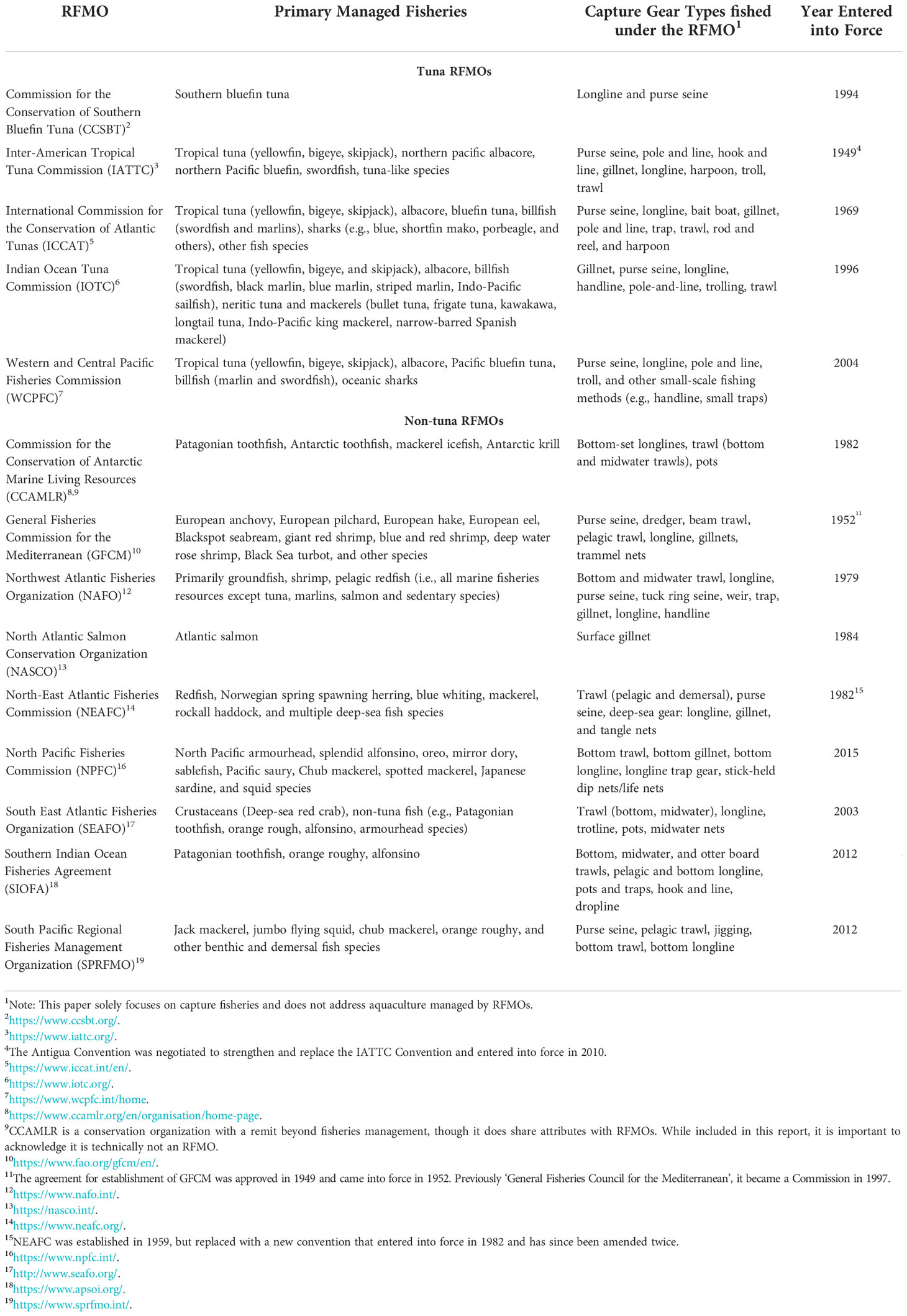

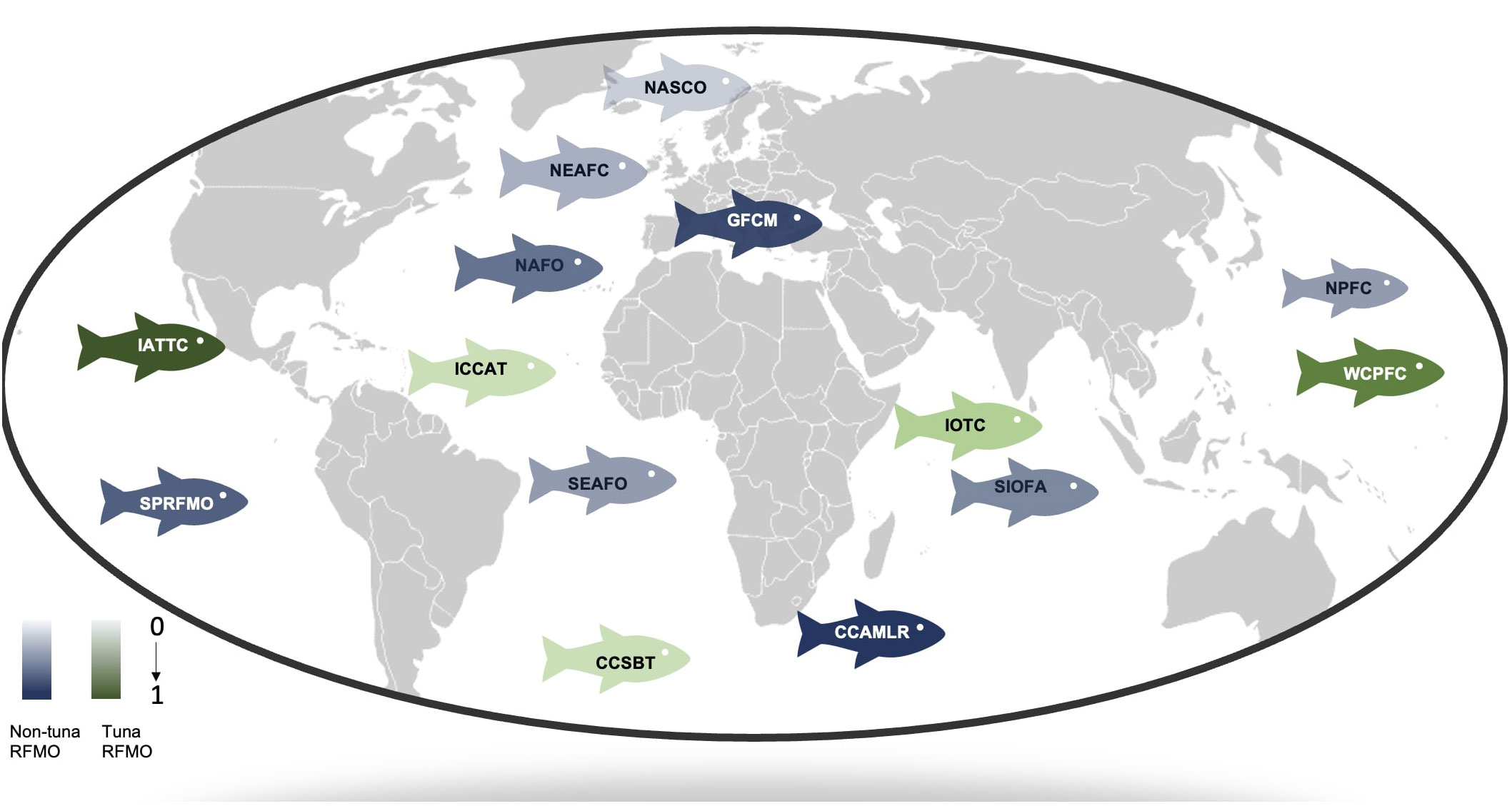

The key actors in the management of high seas and international fisheries are regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs) and their contracting parties (Lodge et al., 2007; FAO, 2020). The FAO defines RFMOs as organizations which “[ … ] have mandates to adopt legally binding conservation and management measures based on the best scientific evidence” (FAO, 2020). Five RFMOs manage tuna and tuna-like species (tRFMOs) and a number of other RFMOs (non-tRFMOs) manage non-tuna fisheries (see Table 1). The primary objective of RFMOs is to manage specific fisheries in their respective Convention Areas, achieved primarily through legally binding conservation and management measures (CMMs).

At the core of international fisheries management lie bedrock agreements governing fisheries – including the United Nations Law of the Sea Convention (UNCLOS) and the United Nations Fish Stocks Agreement (UNFSA). Importantly, UNFSA and UNCLOS both set a legal basis for RFMOs to manage interactions with non-target stocks (e.g. UNFSA Article 5.f, 6.5) and apply the precautionary approach towards living marine resources (UNCLOS Article 119). Many RFMO Convention Agreements, especially those formed after adoption of the 1995 UN Fish Stocks Agreement (e.g., IATTC and its Antigua Convention), require the respective RFMO to address bycatch and/or take an ecosystem-based approach to fisheries management (e.g., Lodge et al., 2007; De Bruyn et al., 2013; Gilman et al., 2014; Juan-Jordá et al., 2018).

The RFMOs’ global footprint and requirements under UNCLOS provide an important potential framework to address cetacean bycatch, given their mandate to manage fisheries within their Convention Areas and, for some, to address the management of other living marine resources. Some RFMOs have passed binding CMMs focused on bycatch, with some addressing multiple taxa and others focusing on specific taxonomic groups (Supplementary Material II). RFMOs are increasingly being called upon to address bycatch more effectively, and existing literature often finds that some RFMOs are underperforming in some aspects of ecosystem-based fisheries management (EBFM) efforts, including bycatch (e.g., Small, 2005; Lodge et al., 2007; Cullis-Suzuki and Pauly, 2010; Gilman et al., 2014; Juan-Jordá et al., 2018, Crespo et al., 2019, Zollett and Swimmer, 2019) (Supplementary Material I and Table 1).

No known previous study of RFMOs has specifically focused on cetacean bycatch management, and the bycatch of cetaceans has received less attention than the bycatch of other megafauna in RFMOs. This comes with one notable exception: dedicated efforts to reduce the mortality of pelagic dolphins from direct setting in yellowfin tuna purse seine fisheries in the Eastern Tropical Pacific (Ballance et al., 2021). For example, cetaceans have fewer safe-handling CMMs than sea turtles, seabirds, or sharks across tRFMOs (Zollett and Swimmer, 2019). At the level of the United Nations, the UN FAO created a framework for International Plans of Action (IPOA) for seabirds and sea turtles, which are voluntary instruments that help operationalize the FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries that suggest States adopt National Plan of Actions if bycatch is an issue in their fisheries (Figure 1) (FAO, 1999b; IOTC, 2021a). The FAO published non-binding technical guidelines decades ago for seabirds (FAO, 2009a), sharks (FAO, 1999a), and sea turtles (FAO, 2009b), but did not finalize their guidelines for marine mammals until 2021 (FAO, 2021).

In light of several recent policy developments – particularly the 2021 FAO Guidelines to prevent and reduce bycatch of marine mammals in capture fisheries (FAO, 2021) and implementation of the U.S. Marine Mammal Protection Act Import Provisions Rule20 which covers many fisheries managed by RFMOs, we find it timely to document the current landscape for managing cetacean bycatch in RFMOs (Figure 1). We review all RFMOs, regardless of known cetacean bycatch rates, to establish a policy review of the current management frameworks to manage cetaceans. This paper acts as a first step to highlight cetacean bycatch management in RFMOs, establish a baseline of the current management framework, and suggest improvements for consideration.

2 Methods

2.1 RFMO selection

We selected 14 RFMOs to review (Table 1), which generally align with those considered elsewhere in the literature (e.g. Small, 2005; Lodge et al., 2007; Gilman et al., 2014; Ewell et al., 2020). We reviewed these 14 RFMOs regardless of known cetacean bycatch levels, which likely vary considerably within RFMOs. Criteria for selection included that each RFMO must be a multilateral and not a bilateral arrangement; must manage capture fisheries in coastal and high seas waters, as opposed to anadromous fishing or management of non-target taxa; must currently be active and established as a decision-making body; and must be an RFMO, rather than a Regional Fisheries Body. Note: This paper includes a considerable number of acronyms; please see the Glossary for a list.

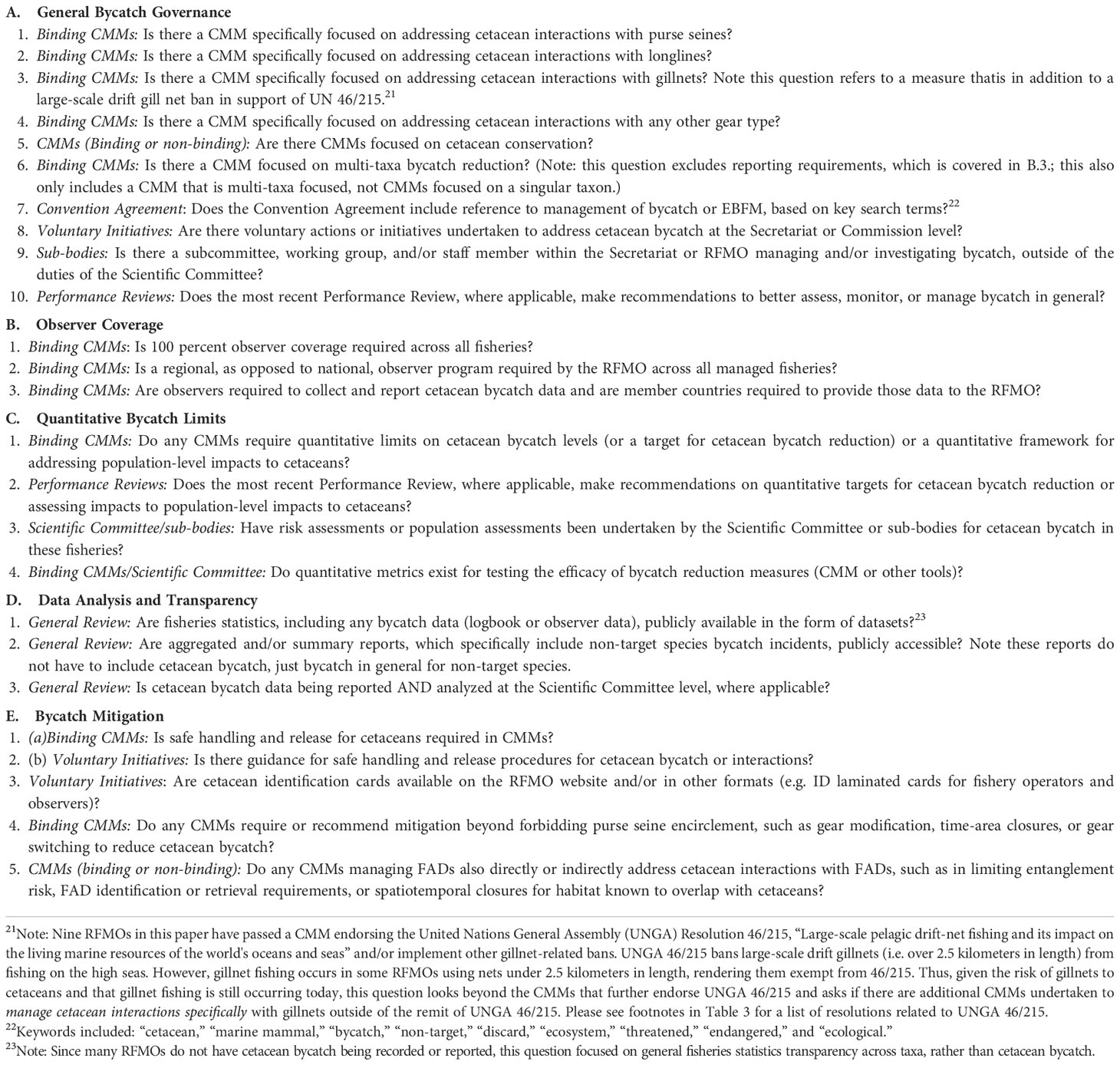

2.2 Criteria to assess bycatch efforts of RFMOs

We designated five categories relevant to bycatch management for review: 1) General bycatch governance, 2) Observer coverage, 3) Quantitative bycatch limits, 4) Data analysis and transparency, and 5) Bycatch mitigation. These five criteria represent a number of key objectives and principles required to manage bycatch, as identified by other studies and reviews (e.g. Lewison et al., 2004; Read et al., 2006; Lodge et al., 2007; Moore et al., 2009; Gilman, 2011; Kirby and Ward, 2014; Komoroske and Lewison, 2015; NOAA, 2016; Hammond et al., 2021; Wade et al., 2021).

We then posed a suite of 25 questions nested within the five categories to assess whether RFMOs had implemented specific measures relevant to cetacean bycatch (Table 2). We selected a contextual balance of criteria that included: 1) a review of elements forming the backbone of RFMO management: binding CMMs, Convention Agreements, Performance Reviews, the Scientific Committee and relevant sub-bodies, and voluntary initiatives (elements noted in italics at the beginning of each question in Table 2); and 2) criteria most relevant to best practices in cetacean bycatch management. We note that for the questions in Category A (General Bycatch Governance), we reviewed CMMs specifically for whether they had measures specific to cetacean interactions for the purposes of this study; some RFMOs more often craft CMMs by fishery or target species depending on the goal of the CMM, rendering a cetacean-focused approach challenging to apply to some RFMOs, but the approach here allowed for a systematic review specific to cetaceans. Finally, in the case of RFMOs with multiple Performance Reviews or revised Convention Agreements, we reviewed only the most recent versions. We reviewed the publicly information available as of March 2022 on each RFMO website in order to address the 25 questions.

The criteria developed here closely align with questions posed in other studies of RFMO governance and/or bycatch performance (e.g. Small, 2005; Cullis-Suzuki and Pauly, 2010; Gilman et al., 2014), but those addressed here focus exclusively on cetacean bycatch.

2.3 Scoring

One author reviewed information for each RFMO for each question with a binary “0” or “1” score, recording a “1” if the RFMO fully fulfilled the criteria. If a question did not apply to an RFMO – for example, if a question asked about purse seine CMMs and an RFMO does not have purse seine fisheries, the RFMO received a “not applicable” (N/A) for the question. To account for N/As, we calculated basic descriptive statistics (range, median) and a scaled average score on a 0.00 to 1.00 scale for 1) each RFMO, 2) sub-criterion, and 3) category, as well as overall total scaled mean that accounted for the N/As. Here, the scaled, average score (“score”) is the proportion of applicable RFMOs with that specific criterion implemented, averaging the scores that received a numerical point only and discounting N/As. For example, for question A.1. on purse seines, nine out of 14 RFMOs manage fisheries with purse seines, so the average score was only calculated across nine RFMOs, discounting the five RFMOs as N/As that do not manage purse seines. We also tallied overall count data, but typically report only scaled scores for consistency given N/As. While the binary scoring facilitated high-level interpretation of results, scoring RFMOs on a binary 0 or 1 category was sometimes challenging (e.g. Category D, Category E regarding FADs, etc. — please see Results and Discussion section). Again, our scoring is simply intended to illuminate trends in RFMOs and aid in a high-level review to understand trends across RFMOs rather than function as a robust statistical analysis of performance.

3 Results

3.1 Overall results

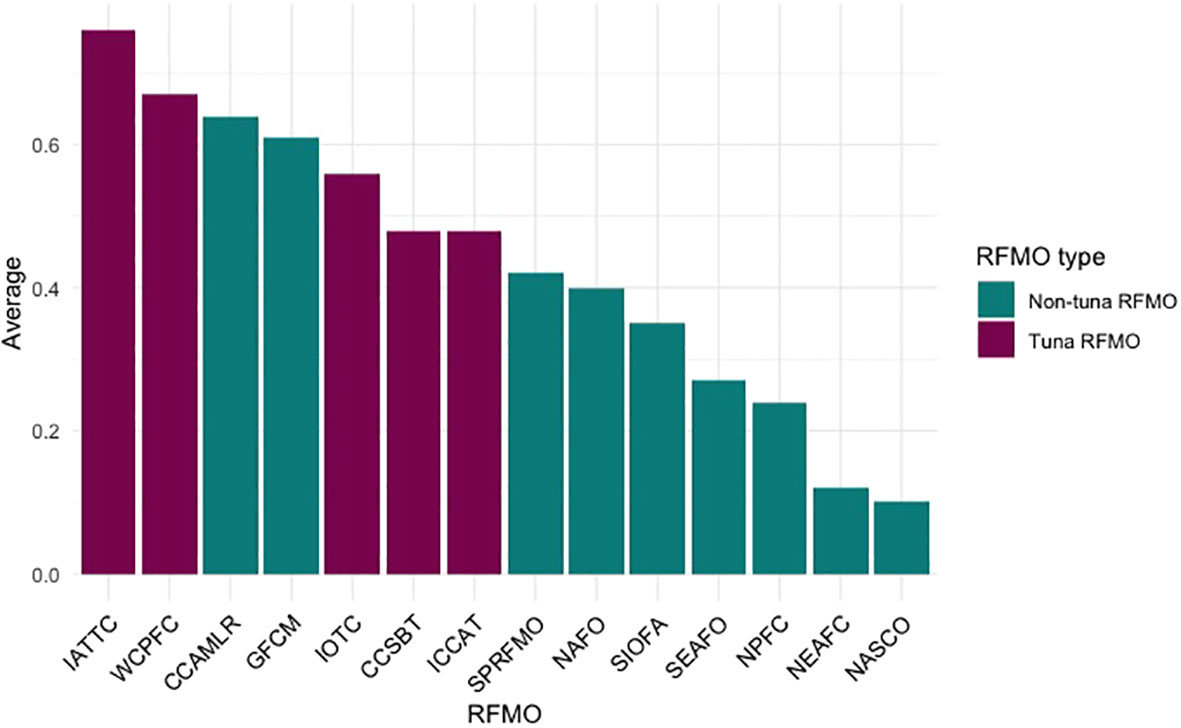

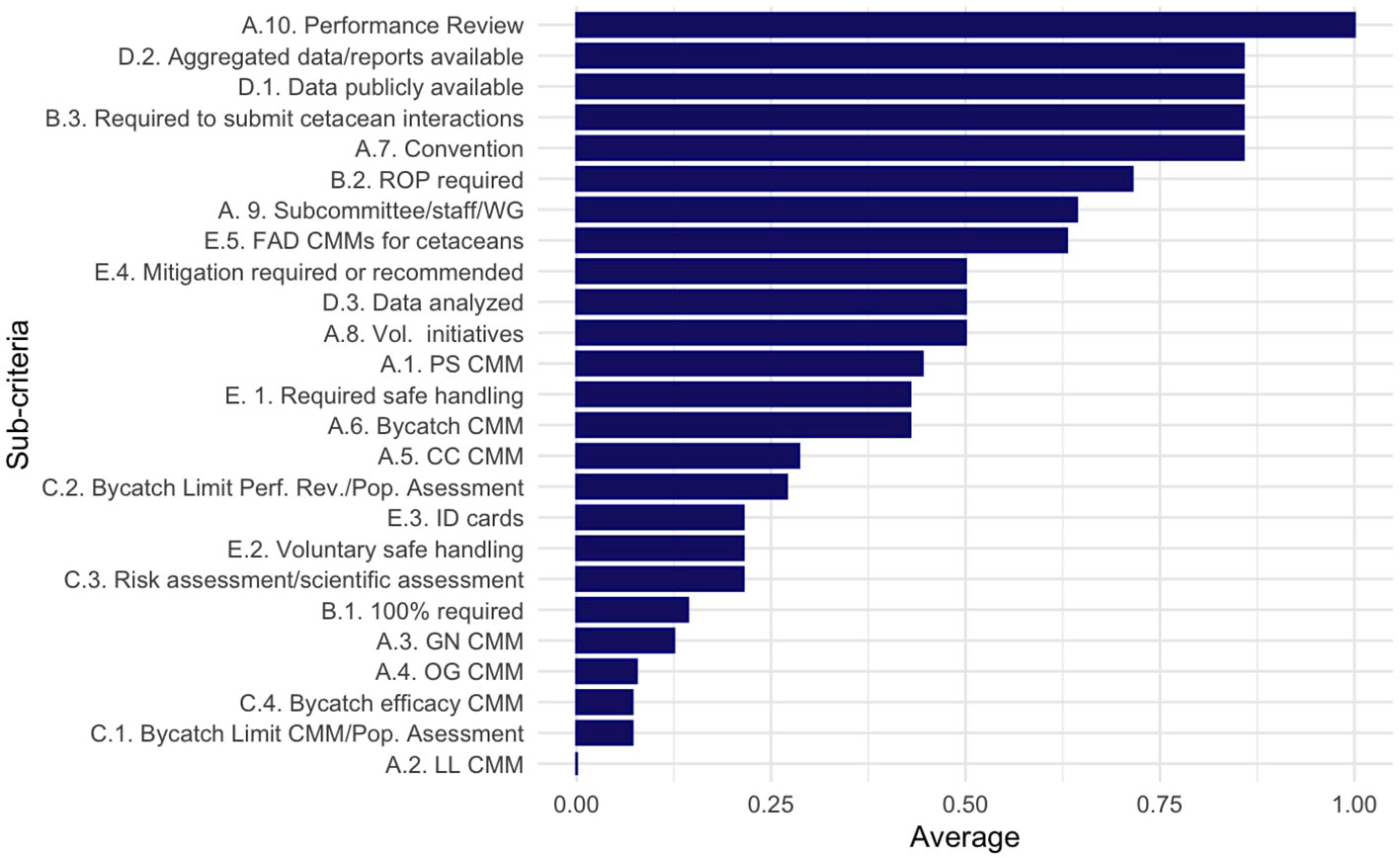

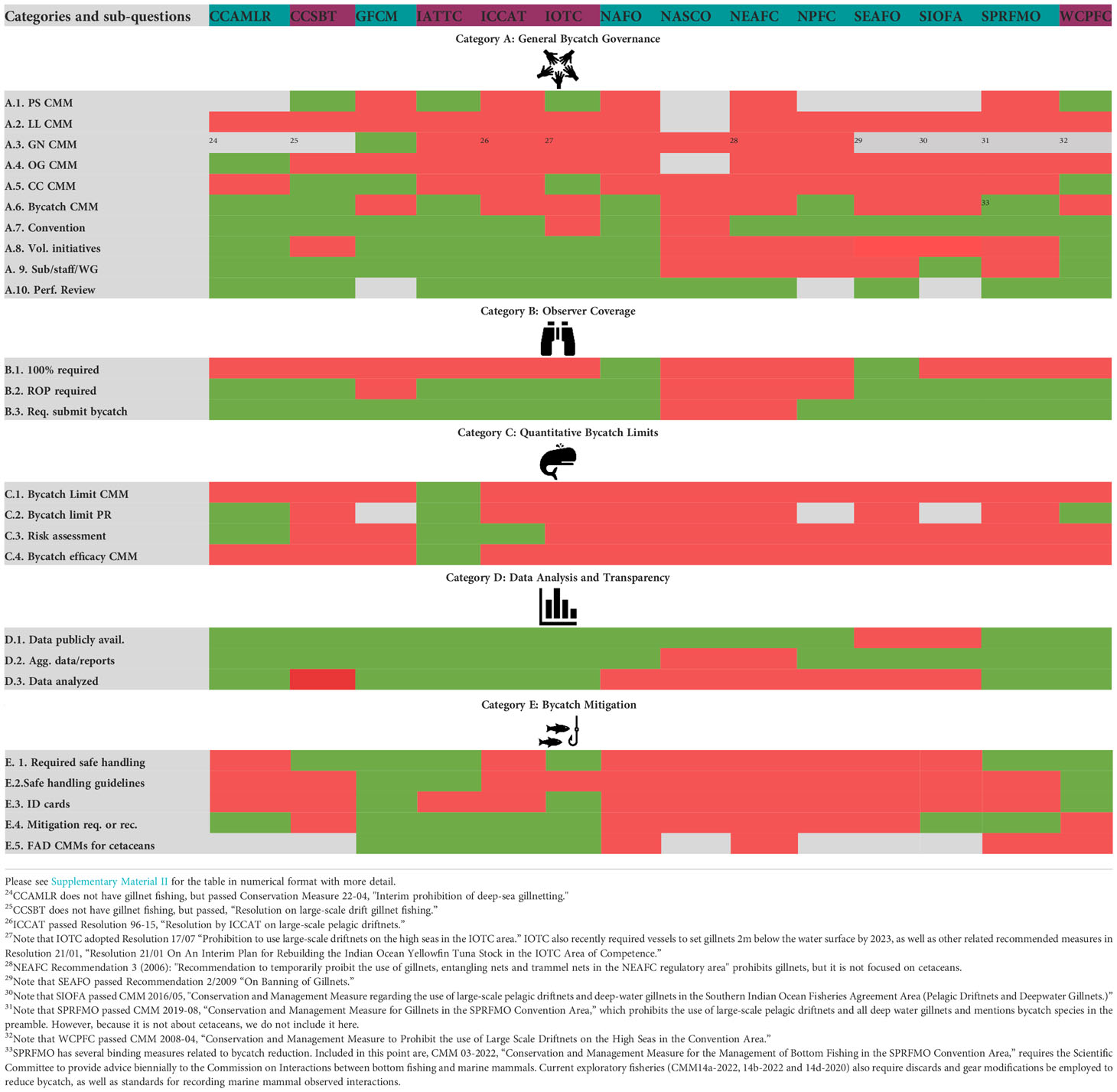

The overall average scaled score for all criteria was 44% and ranged from 0.00% to 100% (Figures 2–5). IATTC scored highest (average=0.76) followed by WCPFC (average=0.67); NASCO scored lowest (average=0.10), preceded by NEAFC (average=0.12) (Figure 2). RFMOs collectively scored highest for Category D, Data Analysis and Transparency (average=0.74) and lowest in Category C, Quantitative Bycatch Limits (average=0.15), which was consistent for both tRFMOs and non-tRFMOs. Overall, tRFMOs scored higher than non-tuna RFMOs across all five categories (Figure 2). See Table 3 and Figure 5, and Supplemental Material II for specific scores for each question, as well as information on the measures or actions for each question; we describe general results here by the five categories.

Figure 3 Overall RFMO score based on the analysis of 25 questions; a darker fish icon represents a higher average score for tuna RFMOs (green) and non-tuna RFMOs (blue), respectively.

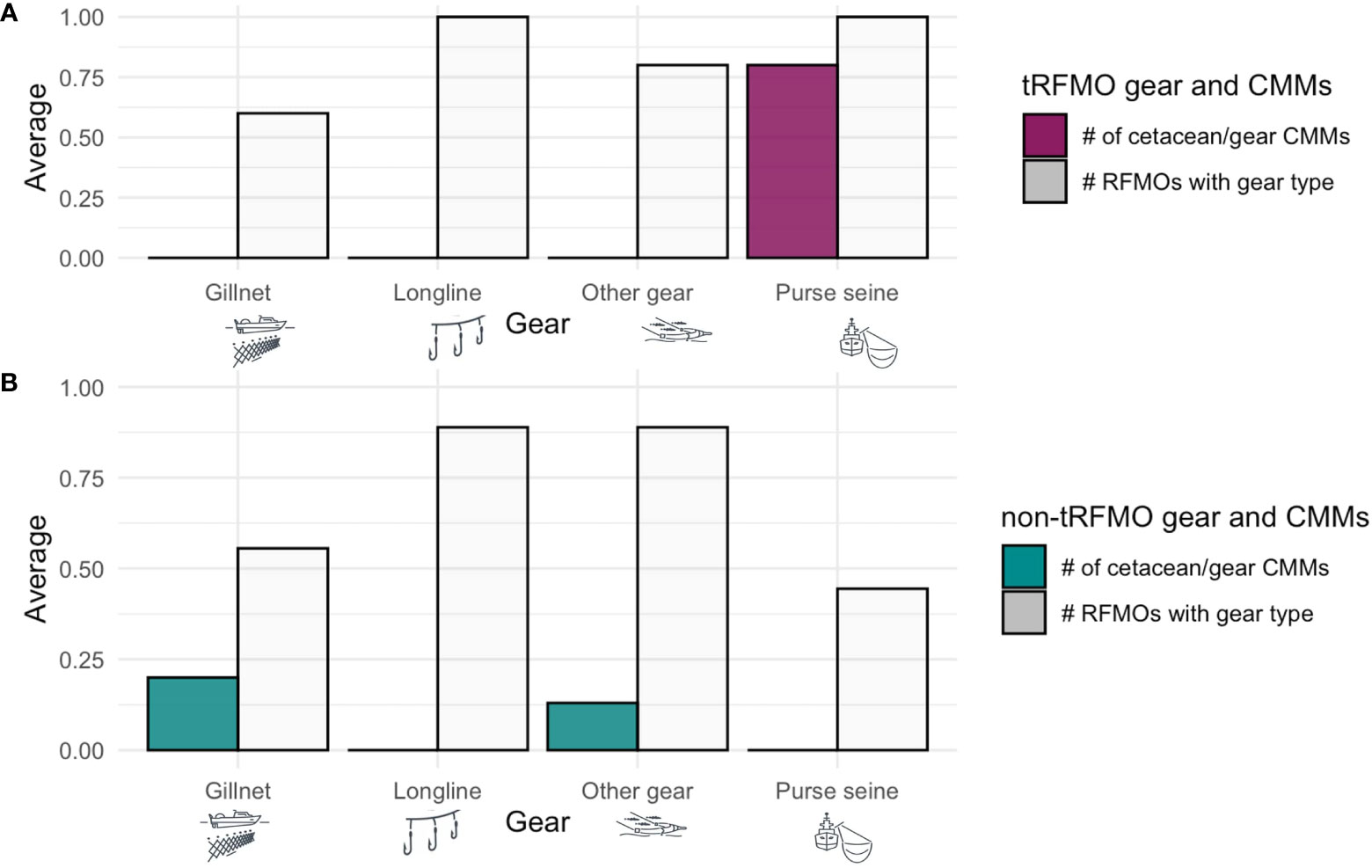

Figure 4 Adopted CMMs compared to total number of RFMOs that have at least one fishery under their purview using purse seines, longlines, gillnets, or other gear in tuna (A) and non-tuna RFMOs (B).

Table 3 Scores by RFMO for each question. A red cell indicates the RFMO did not have the relevant criterion, green indicates they did have the criterion, and grey indicates the question did not apply to the RFMO.

3.2 Results by category

3.2.1 Category A

Within the General Bycatch Governance category, CCAMLR scored highest on average (average=0.75) and NASCO (average=0.14) scored lowest. The five highest-scoring RFMOs all have adopted at least one CMM focused on addressing cetacean interactions with fishing gear (i.e. fulfilling at least one of questions A1-4).

The highest-scoring sub-criterion across all categories was Performance Reviews mentioning the need to address bycatch (100% of applicable RFMOs) (Figure 5). All RFMOs that have conducted a Performance Review mentioned the need to better assess, monitor, and manage bycatch in that review (NPFC and SIOFA have not conducted their first Performance Review, and GFCM’s most recent Performance Review was not publicly available at the time of writing). The second-highest performing sub-criterion across all categories was also in Category A: Convention Agreement references to the key ecologically-related terms; the only two RFMOs without a reference in the Convention to the key EBFM-related terms are IOTC and NASCO. The RFMOs without a dedicated subcommittee, working group, or staff member (i.e. person or sub-committee in addition to work done by the Scientific Committee) dedicated to bycatch were all non-tuna RFMOs: NASCO, NEAFC, NPFC, and SPRFMO.

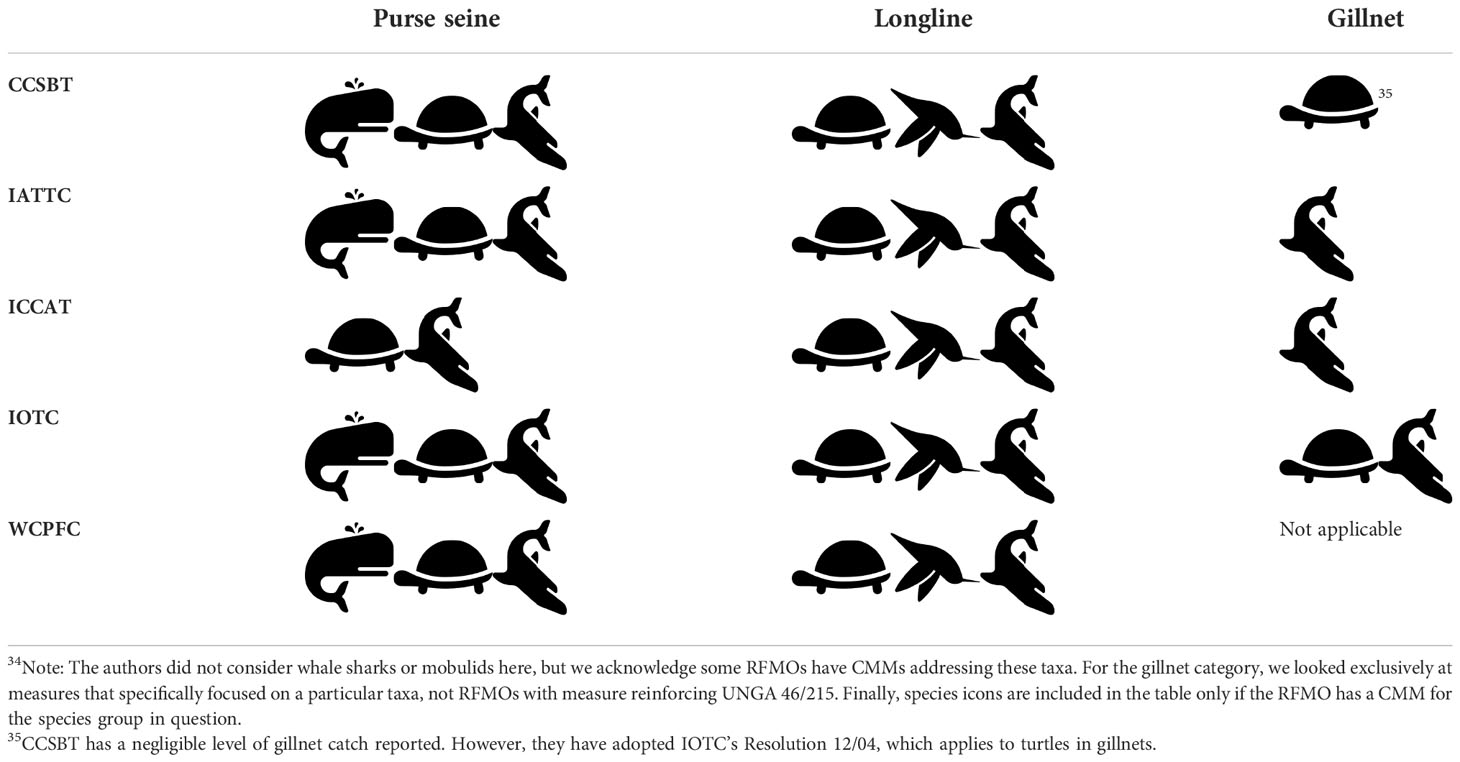

In terms of CMMs covering different gear types, the only gear-specific CMMs adopted for reducing cetacean interactions are for purse seines in tRFMOs; furthermore, ICCAT is the only tRFMO to not have adopted a CMM with any specificity to cetaceans to-date (Figure 4). Importantly, no RFMO has adopted a CMM focused on cetacean interactions with longlines, although discussions on this are underway in WCPFC and IOTC. WCPFC, CCSBT, and IOTC’s cetacean-purse seine measures discuss elements of cetacean conservation; and CCAMLR is the only RFMO with a CMM focused specifically on cetaceans in trawl gear. GFCM is the only RFMO with dedicated measures to both cetacean conservation and cetacean bycatch in gillnets. Nine RFMOs have measures banning large-scale driftnets (all RFMOs except IATTC, NAFO, NASCO, NPFC), some of which also ban deep-water gillnets (Table 3 and Supplemental Material II).

3.2.2 Category B

Eight RFMOs scored highest (average=0.67) in the Observer Coverage category (CCAMLR, CCSBT, IATTC, ICCAT, IOTC, SIOFA, SPRFMO, and WCPFC). All tRFMOs have a Regional Observer Program (ROP) in place requiring varied levels of coverage. The RFMOs that scored the lowest (average=0.00), NASCO and NEAFC, do not require cetacean bycatch be reported. The highest scoring sub-criterion was a requirement to submit information on cetacean bycatch (average=0.86); the lowest was the requirement for 100% percent observer coverage (average=0.14). Two RFMOs require 100% observer coverage (NAFO and SEAFO), but they did not score in the highest for the overall category.

3.2.3 Category C

For the Quantitative Bycatch Limit category, IATTC scored highest (average=1.00). Ten RFMOs tied for the lowest score: CCSBT, GFCM, IOTC, NAFO, NASCO, NEAFC, NPFC, SEAFO, SIOFA, and SPRMO (average=0.00). IATTC’s score in this category is due to the Agreement on the International Dolphin Conservation Program (AIDCP), the only legally binding program in any RFMOs intended to reduce cetacean bycatch in fishing gear, which is managed by the IATTC Secretariat. Although this pertains to direct setting on cetaceans rather than bycatch as considered elsewhere in the paper, the Agreement is binding, includes bycatch limits and 100 percent observer coverage (on large vessels) and metrics to review its efficacy, so it is included as a relevant measure here (AIDCP, 1999). No other RFMO has passed a CMM with bycatch limits or a CMM that contains metrics to test the efficacy of any bycatch-reduction measures for cetaceans.

Like Category A, the highest scoring sub-criterion was whether Performance Reviews called for the establishment of bycatch limits or population assessments, although the average score for this question was much lower than in Category A (average=0.27) (Figure 5). CCAMLR, IATTC, and WCPFC’s Performance Reviews call for bycatch limits regarding cetaceans. The questions about CMMs focused on bycatch limits and CMMs calling for evaluating the efficacy of bycatch metrics (C1 and C4) scored lowest (average=0.07) as IATTC was the only RFMO to meet these criteria.

3.2.4 Category D

In the Data Analysis and Transparency category, seven RFMOs tied for the highest score: CCAMLR, GFCM, IATTC, ICCAT, IOTC, SPRFMO, and WCPFC (average=1.00). NASCO, NEAFC, SEAFO, and SIOFA tied lowest (average=0.33). Publicly available datasets and aggregated reports tied for the highest (average = 0.86). The third and final question in the category about cetacean bycatch being analyzed scored lowest, with half of the RFMOs doing so. However, this is challenging to answer; thus, a “1” was given if the Secretariat or Scientific Committee or other subsidiary body within the RFMO has analyzed bycatch records at the species level. This scoring system rendered two suboptimal outcomes: RFMOs with bycatch received a higher score, and RFMOs without bycatch were penalized in a sense because they received a lower score for not having reported bycatch. RFMOs not reporting bycatch were assigned a zero instead of an N/A because, given low observer coverage rates and underreporting in many RFMOs, particularly non-tRFMOs, the true absence of bycatch in a fishery cannot be confirmed. Nevertheless, the RFMOs that scored highest here also generally track with those scoring higher in other categories.

3.2.5 Category E

For the Bycatch Mitigation category, GFCM scored highest (average=1.00), closely followed by IATTC, IOTC, and WCPFC (average=0.80). Five of the non-tRFMOs received no points in this category (NAFO, NASCO, NEAFC, NPFC, SEAFO) (average=0.00). The mitigation required or recommended question scored highest (average=0.50). IATTC, GFCM, and recently, WCPFC, are the only RFMOs which have endorsed actual guidelines for safe handling and release of cetaceans (WCPFC, 2021a); several others call for it within CMMs but do not currently have guidelines. Only three RFMOs provide ID cards online at the time of writing: GFCM, IOTC, and WCPFC for use by crew and observers in recording accurate information about interactions. Five RFMOs (ICCAT, IATTC, IOTC, WCPFC, and GFCM) have some form of FAD requirements or guidelines with some level of relevance to cetaceans; the wording for this question was quite ambiguous, and essentially any RFMO with a measure calling for reducing entanglement or mitigating FADs in any way was awarded a point.

4 Discussion

RFMOs form the backbone of international fisheries management and governance (FAO, 2020) and are key actors in implementing bycatch measures. Despite this global responsibility, many previous assessments indicate that RFMOs are underperforming in managing both target stocks and bycatch (e.g., Cullis-Suzuki and Pauly, 2010; Gilman et al., 2014). Our analysis underscores the fact that RFMOs vary considerably in their commitment to address bycatch. The overall average score (44%) demonstrates that there is considerable room for improvement across all bycatch management areas. Our findings, however, demonstrate an improvement by RFMOs from the most recent bycatch performance review (Gilman et al., 2014), which found a mean performance score of 25 percent across 13 RFMOs (albeit for slightly different five criteria). Our study provides the first review of RFMO management frameworks for cetacean bycatch — a taxon that has been historically overlooked by most RFMOs — but our approach only addresses RFMO efforts ‘on paper’ as a starting point, rather than assessing actual compliance, implementation, or effectiveness of these measures. Further, the scoring was conducted at a very high-level; the scores are meant to illuminate key trends and progress in the bycatch criteria rather than provide a robust statistical analysis. RFMOs are complex institutions, with many factors affecting actions of member countries, such as politics, technical capacity, and finances, informing RFMO decision making (e.g. Haas et al., 2020; Petersson, 2020). We do not attempt to do quantify these challenges here. Despite the trade-offs of the analytical approach taken here, this paper nevertheless provides a landscape of the existing tools and framework within RFMOs to manage cetacean bycatch as a starting point for future reviews. Below, we briefly review the general trends in the five reviewed categories and sub-criteria.

4.1 General trends in each category

4.1.1 General bycatch governance

The General Bycatch Governance Category was the largest and most diverse set of questions, and thus only highlights from this section are discussed here. Two of the top five highest-performing sub-criteria overall occurred in the General Bycatch Governance Category (A10, Performance Reviews, and A7, Convention references) but, at the same time, three of the five lowest-scoring questions also came from this category (A3, A4, A5 on gear interactions) (Figures 4, 5). Every RFMO which has undertaken a Performance Review has mentioned the need to address bycatch and most RFMOs’ Convention Agreements include the key search terms to address bycatch, particularly those that were formulated or amended after the UN Fish Stocks Agreement. Importantly, no RFMO has adopted a CMM focused on cetacean bycatch in longline fishing gear, although discussions are underway at some RFMOs, primarily led by Korea (e.g. IOTC, 2021b; IOTC, 2021c; WCPFC, 2021b). Existing measures are almost exclusively focused on purse seines (WCPFC, 2011; IOTC, 2013).

The topic of CMMs addressing the bycatch of cetaceans in gillnets is particularly important given the risk of this gear type to cetaceans (e.g. Brownell et al., 2019; Anderson et al., 2020). The GFCM is the only RFMO to adopt a cetacean-specific gillnet measure; most gillnet-focused measures in RFMOs prohibit large-scale drift gillnets in support of United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) resolution 46/215 banning large-scale drift gillnets on the high seas, together with some deep-water gillnet bans (see Supplementary Material II). These measures significantly reduce the potential for bycatch, but they do not address gillnets under 2.5 km in length or those fished in Exclusive Economic Zones, nor are they aimed specifically at cetaceans. The exception is the IOTC, where two recent measures have moved beyond the UN drift gillnet ban: 1) IOTC Resolution 17/07 “To prohibit the use of large-scale driftnets on the high seas in the IOTC area,” expanded the ban of large-scale drift gillnets on the high seas to include the IOTC’s entire Area of Competence, including EEZs, and (IOTC, 2017) 2) Resolution 21/01, “On An Interim Plan for Rebuilding the Indian Ocean Yellowfin Tuna Stock in the IOTC Area of Competence,” required vessels to set gillnets 2 meters below the water surface by 2023 (IOTC, 2021), a technique shown to be promising in reducing bycatch in Pakistan (Kiszka et al., 2021), as well as other voluntary recommendations to increase observer coverage and phase out gillnets. However, multiple IOTC Members have objected to one or both of these measures, thereby eroding the efficacy of the CMMs.

Finally, although non-binding, voluntary initiatives scored in the top-ten questions. Highlights include that WCPFC (together with the Pacific Community and with support from the FAO) recently established the Bycatch Management Information System and the Bycatch Data Exchange Protocol, two online resources which collate information on best available science and bycatch management efforts. The FAO has also launched several bycatch projects involving RFMOs under its Global Sustainable Fisheries Management and Biodiversity Conservation in the Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction Program. In the Indian Ocean, under Phase I, the Common Oceans ABNJ Project supported work between the IOTC and the World Wildlife Fund Pakistan to conduct trials reducing the depth of drift gillnets, which reduced bycatch and sustained target catch (e.g. Kiszka et al., 2021). Additionally, the tRFMOs convened several joint dialogues to discuss bycatch issues under the cooperative “Kobe” process since 2007 (Joint T-RFMOs Bycatch Working Group, 2019). These efforts are all promising, but their efficacy in reducing cetacean bycatch is poorly understood, apart from the gillnet mitigation trials in Pakistan. We note this is certainly not an exhaustive list of voluntary initiatives, and we encourage RFMOs to increase public awareness and messaging about voluntary initiatives where they exist.

4.1.2 Observer coverage

All tRFMOs and just over half of non-tRFMOs (i.e. CCAMLR, NAFO, SEAFO, SIOFA, SPRFMO) have a Regional Observer Program – considered the standard for observer coverage (Northridge, 1996). With the exception of AIDCP under IATTC and icefish and toothfish fisheries under CCAMLR, no RFMO requires that the observer be from a different flag state than the vessels, which may lead to bias and observer effects (Ewell et al., 2020). Some RFMOs are also working to increase observer coverage via electronic monitoring, with trials underway within some RFMOs (Ewell et al., 2020; Pew Charitable Trusts, 2022).

We used full observer coverage as the standard in this study, but we recognize that this is not necessary in all fisheries. Babcock et al. (2003) suggested that observer coverage should be at least 50 percent to generate accurate estimates of bycatch, and the goal of any observer program should be to generate information that allows for a robust estimation of target catch and bycatch rates. In some fisheries, bycatch of cetaceans is rare, so relatively high levels of observer coverage may be needed to generate robust estimates of the magnitude of this mortality (Hall, 1999; Moore et al., 2009; Curtis and Carretta, 2020). Only two RFMOs, NAFO and SEAFO, have 100 percent observer coverage on all fisheries; other RFMOs have full coverage on some, but not all, fisheries (e.g. NPFC’s CMM 2019-10, SPRFMO CMM 03-2022) (NPFC, 2019, SPRFMO, 2022a).

4.1.3 Quantitative bycatch limits

Most of the RFMOs have not developed quantitative limits, biological reference points, or other quantitative information related to cetacean bycatch, so this category scored lowest. The only RFMO to include such quantitative limits for cetaceans is the IATTC, through AIDCP – a legally binding agreement that requires dolphin mortality limits in tuna purse seine fisheries. CCAMLR does require certain bycatch limits, but they are not specifically for cetaceans (e.g., Measure 33-02, “Limitation of by-catch in Statistical Division 58.5.2 in the 2021/22 season”) (CCAMLR, 2020b). Of course, setting limits on the total number of animals permitted to be captured in a fishery is a top-down approach to reducing bycatch and may not be the most effective option in some fisheries (Wade, 1998; Dawson and Slooten, 2005; Squires et al., 2021); we included it here as an example of a quantitative performance metric.

Importantly, no RFMO has a CMM that calls for the review of existing bycatch measures or any metric to test the efficacy of bycatch reduction, apart from the International Review Panel established under AIDCP to monitor mortality and compliance through observer data (AIDCP, 1999). This limits an understanding of rewarding what is working in RFMOs and identifying where management improvements are necessary.

4.1.4 Data analysis and transparency

This category scored the highest of the five categories, with almost all RFMOs having bycatch (general bycatch) datasets available to the public in some form; most also have aggregated reports available created by the Scientific Committee, Secretariat, or other subsidiary body. Half of the RFMOs are analyzing these data, although in some cases it may be that the RFMOs do not have cetacean bycatch data being reported to analyze. However, there was wide variation in the detail and level of reporting in these datasets, and the binary nature of the scoring system used in this study did a disservice to the variation in both data quality and data availability. Essentially, if a dataset existed, regardless of the number of interactions or level of detail to make a dataset research-grade, an RFMO received a score, when sometimes there could be just very few records without detail. When data was missing, it was sometimes unclear whether this was symptomatic of a lack of bycatch, practical difficulties in observing the bycatch or insufficient observer coverage, or underreporting, and made this category challenging to score. In the end, we did not consider a lack of cetacean bycatch data as a reason to score an RFMO an “N/A” for review of this category, given sometimes very low observer coverage rates and underreporting (please see Results for further discussion).

It is clear that there is room for growth in transparency, data reporting, observer coverage, and other factors that would improve bycatch analyses (Clark et al., 2015; Haas et al., 2019; Ewell et al., 2020; Heidrich et al., 2022), but the three questions posed in this category were at a very high level and do not cover finer details of robust bycatch assessments, such as spatially explicit data on bycatches, post release mortality, and fishing effort. Heidrich et al. (2022) recently analyzed data analysis efforts in tRFMOs for target stocks and painted a comprehensive picture of the strengths and gaps in tRFMO data coverage. They did not assess cetaceans, however, and we encourage a similar analysis of megafauna bycatch that would illuminate data gaps and needs in data transparency and analysis for bycaught species. Thus, while this category received the highest score overall of the five categories, this is another example of needing to interpret the scores themselves with caution.

4.1.5 Bycatch mitigation

Half of the RFMOs stood out for their mitigation measures: 1) IATTC (via AIDCP: backdown procedures to release live dolphins, Medina panels to prevent entanglement, no night setting, catch limits per vessel in purse seine fisheries (AIDCP, 1999), 2) ICCAT (Resolution 05-08 encourages the use of circle hooks) (ICCAT, 2008), 3) IOTC (Resolution 21/01 to set gillnets at 2m depth) (IOTC, 2021), 4) CCAMLR (CM 51-02, 51-03, 51-04 requires marine mammal exclusion devices on trawls) (CCAMLR, 2008a; CCAMLR, 2008b, CCAMLR, 2020a), 5) GFCM (Recommendation GFCM/37/2013/2 sets monofilament diameter limits to reduce entanglement; Recommendation GFCM/36/2012/2 recommends pingers and reflective mitigation on gear) (GFCM, 2012; GFCM, 2013), 6) SIOFA (CMM 2021/15 which requires mitigation for reducing depredation in longlines) (SIOFA, 2021), and 7) SPRFMO (CMM 14d-2020, trotlines use Cachalotera) (SPRFMO, 2020). Currently, CMMs related to FADs in most of the RFMOs are indirectly related to cetaceans, requiring parties to reduce the risk of entanglement and use biodegradable material among other measures, but they are typically not directly focused on reducing cetacean interactions (Supplementary Material). As more technical information becomes known about cetacean interactions with FADs (material, configurations posing the highest risk of entanglement, etc.), it would be prudent for RFMOs to consider more-specific measures for cetaceans.

Only three RFMOs currently offer detailed safe handling and release guidelines for cetaceans (Zollett and Swimmer, 2019) (WCPFC, IATTC, and GFCM) (IATTC n.d; FAO and ACCOBAMS, 2018; WCPFC, 2021a). Studies have also highlighted the importance of identification cards for fishermen and observers (e.g. Moore et al., 2010), but only two RFMOs (GFCM and IOTC) offer publicly accessible cetacean identification cards. Many of the above efforts would be advantageous to improving safe release and post-capture survival.

4.2 Overall RFMO performance

IATTC, WCPFC, CCAMLR, and GFCM have been the most proactive RFMOs in addressing cetacean bycatch (Figures 2, 3 and Table 3) (Gilman et al., 2012; Juan-Jordá et al., 2018). The IATTC and WCPFC reference non-target species and other ecological components in their Convention; both have binding measures to reduce cetacean bycatch in purse seine or other fisheries; both have safe handling and release guidelines; and both are analyzing bycatch data. In the case of the IATTC, the AIDCP clearly sets it apart in terms of observer coverage and quantitative bycatch limits, although this is a unique case because these requirements pertain to intentional encirclement of dolphins and result from a negotiated agreement. CCAMLR is exceptional in its focus on a precautionary, science-based approach to management and has a variety of CMMs directly and indirectly related to cetaceans and pinnipeds, some of which set limits on bycatch. CCAMLR also identifies sentinel species representative of ecosystem change (including the Antarctic fur seal, Arctocephalus gazella). CCAMLR is widely recognized for its ecosystem-based management approach (Small, 2005; Cullis-Suzuki and Pauly, 2010, etc.).

The GFCM has recently been undertaking efforts to address cetacean bycatch. For example, this RFMO adopted a CMM in 2012 that sets conservation objectives, calls for data recording, and references a review of gear type as a possible mitigation measure for cetacean bycatch (GFCM/36/2012/2) (GFCM, 2012; GFCM, 2013, GFCM, 2019), as well as a cetacean-specific measure that calls for enhanced data reporting, mitigation implementation, and other conservation objectives (GFCM/43/2019/2) (GFCM, 2019). GFCM is also working on a large-scale study to better understand and mitigate bycatch in the Mediterranean and has developed a standard methodology for bycatch data collection (FAO, 2019). However, GFCM had very little observer coverage, indicating room for improvement to improve cetacean bycatch monitoring and assessment.

Several RFMOs scored primarily in the mid-range of RFMOs (0.56 to 0.35), including: IOTC, CCSBT, ICCAT, SPRFMO, NAFO, and SIOFA, respectively. CCSBT is unique in that it does not have a formalized Convention Area and overlaps with IOTC, WCPFC, and ICCAT. CCSBT has adopted Ecologically Related Species-CMMs from other RFMOs, including the IOTC’s Resolution 13-04 “On the Conservation of Cetaceans” and ICCAT’s Recommendation 11-10, “Information Collection and Harmonization of Data on By-catch and Discards in ICCAT Fisheries” (ICCAT, 2011). To-date, CCSBT reports negligible interactions with cetaceans.

In 2013, the IOTC passed a binding measure prohibiting setting purse seines on cetaceans on the high seas and required reports of interactions in other gear (Resolution 13/04) (IOTC, 2013). A serious concern for cetaceans within IOTC fisheries is the widespread and increasing use of drift gillnets (e.g., Shahid et al., 2015; Anderson et al., 2020). The IOTC made changes in recent years to two measures (Resolution 21/01 and 17/07) to better manage gillnet fisheries and bycatch, but some of the new changes are voluntary (e.g. Resolution 21/01 encourages Members to transition to sub-surface gillnetting) and several Members have objected to these measures. IOTC does not reference non-target species in its Convention and underreporting on cetacean bycatch remains an issue (Gilman et al., 2012; Anderson et al., 2020).

ICCAT has no cetacean-focused CMM, including in its purse seine fisheries. Its Subcommittee on Ecosystems tracks and analyzes bycatch, but predominantly for sharks, turtles, and seabirds. A 2018 ICCAT Standing Committee on Research and Statistics (SCRS) report notes that ICCAT is lacking data to inform what constitutes a cetacean interaction, that observer data are currently not used to constitute bycatch estimates, and that such observer data are confidential (ICCAT, 2018). However, ICCAT recently reappointed a staff bycatch coordinator and the ICCAT Subcommittee of Ecosystems is also developing an Ecosystem report card that, once finalized, should have indicators for cetaceans.

SPRFMO has made considerable progress on addressing bycatch, and quickly, since coming into force in the past decade. SPRFMO’s convention has an emphasis on an ecosystem-based and precautionary approach to management; a ban on the use of gillnets; and has several CMMs with reference to cetacean bycatch mitigation. SPRFMO has a suite of CMMs for various fisheries that include marine mammal monitoring and reporting (e.g. CMM 02-2022 and 16-2022) (SPRFMO, 2022b, SPRFMO, 2022c). SPRFMO has published reports of interactions with marine mammals; for example, the latest Scientific Committee meeting report summarizes bycatch events with several dolphin species, although cetaceans were caught much less frequently than other taxa (e.g. seabirds and sharks) (SPRFMO, 2021).

NAFO has a requirement for 100 percent observer coverage, and undertakes communication with relevant regional scientific bodies (i.e. the North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO) and the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES)) on conservation (i.e., the ICES/NAFO/NAMMCO Working Group on Harp and Hooded Seals). SIOFA, a relatively young organization, has started addressing marine mammal interactions in work on an Ecological Risk Assessment (SIOFA, 2022), and it also addresses marine mammal depredation in its longline fisheries in measure CMM 2021/15 – the only known CMM within RFMOs to do so.

The RFMOs with the fewest CMMs to address cetacean bycatch are SEAFO, NPFC, NEAFC, and NASCO. Every RFMO except NASCO and NEAFC has a requirement to report cetacean interactions. Some of these organizations have minimum bycatch reporting requirements or observer requirements (see Supplementary Material II), but it is important to note that some of these RFMOs turn to ICES for scientific advice (i.e. NEAFC), have relatively low levels of fishing effort (e.g., SEAFO and NASCO), have extremely limited fisheries altogether (e.g. NASCO), combined with a perceived low likelihood of marine mammal interactions, so there is arguably little need for cetacean bycatch measures.

4.3 Lessons from other policy developments

In 2021, the FAO published its “Guidelines to Prevent and Reduce Bycatch of Marine Mammals in Capture Fisheries” which outline tools to reduce marine mammal bycatch (FAO, 2021). The Guidelines also make recommendations to a variety of stakeholders, including RFMOs: “Where appropriate, adopting binding measures to prevent and reduce marine mammal bycatch and incorporating the appropriate text into other regional agreements,” “requiring appropriate levels of monitoring and reporting regarding marine mammal bycatch throughout their region;” “establishing and supporting working groups to provide scientific advice on bycatch management in fisheries, and ensuring that marine mammals get adequate attention in such working groups;” and others (FAO, 2021). These guidelines, as well as FAO International Plans of Action, have been in place for some time for seabirds, sea turtles, and sharks (Lewison et al., 2011), and more measures exist for these other taxa than for marine mammals within RFMOs (Table 4). There is a longer history of engagement by scientists working on the bycatch of other taxa at RFMO meetings, as well as often more data for other taxa. RFMOs could seize on the publication of these guidelines as a starting point towards adoption of these measures.

Table 4 Binding CMMs focused on addressing other taxa (whales, sea birds, sea turtles, and sharks) with fishing interaction measures in tRFMOs34.

Additionally, the United States MMPA Import Provisions now requires that nations exporting fish and fish products to the U.S. develop standards to address marine mammal bycatch in their fisheries comparable to those implemented in the U.S. (81 FR 54389). The Rule is focused on bycatch management by individual nations, but there is a clause in the Rule that requires that nations demonstrate that “they are implementing the requirements of an RFMO or intergovernmental agreement to which the U.S. is a party” as part of achieving a “comparability finding,” which is necessary to continue exporting fish and fish products to the U.S. (81 FR 54389). Recognizing that the Rule poses serious challenges for many nations to comply (Williams et al., 2016), it affords an unprecedented opportunity to address cetacean bycatch at a global scale. There is an opportunity for RFMOs to play an important role in sharing information and developing technical capacity, particularly for RFMOs in which the U.S. is a member, so that individual Member states can meet the provisions of the MMPA Import Rule. The Pew Lenfest Ocean Program has developed a suite of marine mammal bycatch guidance and expertise that is tailored to help nations comply with the Rule, which offers additional resources for addressing bycatch that could be relevant at RFMOs (Lenfest Ocean Program, 2022). To-date, we are unaware of any public-facing synergy or collaborations linking the Import Provisions with RFMO efforts.

4.4 Looking ahead

This work describes the current framework for managing cetacean bycatch in RFMOs and is intended to serve as a preliminary discussion on improving bycatch management in RFMOs. Moving forward, as a priority, we believe an important opportunity and priority exists to collate and comprehensively examine bycatch data at a global level – coupled with improvements in bycatch data collection, data reporting frequency and data quality, and observer coverage. Substantial data gaps remain concerning cetacean bycatch, particularly within RFMO fisheries. Underreporting, a lack of compliance, and a lack of observer coverage, particularly in artisanal and semi-artisanal fisheries, such as drift gillnets in the Indian Ocean, has often prevented managers and scientists from identifying fisheries in which bycatch occurs. This would provide mangers with a much better sense of where the problems lie, and reward RFMOs that have undertaken work to monitor, report and mitigate bycatch. At this point in time, cetacean bycatches are under-reported, seldom analyzed, and no comprehensive global review of these holdings has been conducted. Some fisheries with high bycatches have already been documented, such as tuna drift gillnet fisheries in the Indian Ocean (Anderson et al., 2020) and, historically, IATTC purse seine fisheries (Ballance et al., 2021), but there are likely others.

In addition to data reporting, we also recommend that RFMOs consider adopting more taxon-specific conservation measures, like some of the cetacean purse seine measures in tRFMOs. Figure 4 provides a high-level overview of the gaps between gear use and corresponding CMMs; Table 4 also depicts a high-level overview of the other available CMMs for other taxa in tRFMOs. There is a need for RFMO contracting parties to put forward additional binding measures for cetaceans across gear types, with supporting performance metrics of the currently existing measures. Further, with the use of FADs increasing in some purse seine fisheries (Pew Charitable Trusts, 2015; Gomez et al., 2020; Swimmer et al., 2020), RFMOs should develop protocols to reduce and mitigate interactions between cetaceans and FADs. RFMOs should also consider additional gear mitigation measures, such as altering the set depths of gillnets, the use of circle hooks in longlines, and other changes that have proven to be effective (e.g. Cox et al., 2007; Swimmer et al., 2020; Kiszka et al., 2021). The complex interplay between international politics and addressing cetacean bycatch often prohibits progress, but solutions must be put forward. In the interim, non-binding safe handling and release guidelines, coupled with fisher training (Zollett and Swimmer, 2019), can help to mitigate the consequences of bycatch.

Finally, we recommend that the RFMOs convene a technical workshop, similar to the 2019 Joint tRFMO meeting on elasmobranch bycatch held in Porto (Joint T-RFMOs Bycatch Working Group, 2019), to focus on cetacean bycatch and synergize knowledge from the FAO and the IWC BMI, including discussion on better bycatch data collection and improved observer coverage. Such a workshop would offer an opportunity to generate momentum, given the timeliness of the FAO guidelines and the U.S. MMPA Import Provisions Rule. We encourage discussion about increased capacity at the national level and within RFMOs to address cetacean bycatch, such as through various funding opportunities like those provided under the IWC BMI or FAO Common Oceans project.

Conclusion

There is considerable room for improvement across all RFMOs in managing cetacean bycatch. Improving observer coverage, better data reporting, and collaboration with regional and global organizations will enable RFMOs to gather more information on the bycatch of cetaceans. These improvements are needed to properly understand bycatch risk, potential population-level impacts, and develop an effective management response. The recent publication of the FAO Technical Guidelines, implementation of the U.S. MMPA Import Provisions, actions under the FAO Commons Oceans ABNJ projects, and growth of the IWC’s Bycatch Mitigation Initiative all provide impetus, support, and frameworks for effective action to reduce bycatch. We encourage RFMOs to build on this momentum and work towards developing cetacean bycatch monitoring programs and develop practical, workable solutions for their fishing fleets.

Data availability statement

The data used for RFMOs is summarized in the Supplementary Material II and came from public-facing RFMO websites. For additional information, please direct inquiries to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

BE led planning, scoping, research, writing, and analysis (including scoring). MT assisted with planning, research, contacting RFMOs, providing technical expertise, and editing. AR assisted with editing, writing, and idea development. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

We thank Duke University for a Graduate Student Training and Enhancement Grant for BE to support this work in 2020 as well as funding from Duke’s Open Access Publishing Equity (COPE) Fund to support publication of this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We graciously thank staff at the RFMO Secretariats for their time and efforts in reviewing drafts of this manuscript; this paper would not have been possible without their input and expertise in 2020 and 2022. We also thank Dr. Rebecca Lent and IWC Secretariat staff with assistance early on with this work, as well as overall support during the writing process; we similarly thank the IWC’s Scientific Committee ´Human Impacts and Mortality´ subcommittee for comments on this work in 2020.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2022.1006894/full#supplementary-material

Glossary

Footnotes

- ^ Note: This paper solely focuses on capture fisheries and does not address aquaculture managed by RFMOs.

- ^ https://www.ccsbt.org/

- ^ https://www.iattc.org/

- ^ The Antigua Convention was negotiated to strengthen and replace the IATTC Convention and entered into force in 2010.

- ^ https://www.iccat.int/en/

- ^ https://www.iotc.org/

- ^ https://www.wcpfc.int/home

- ^ https://www.ccamlr.org/en/organisation/home-page

- ^ CCAMLR is a conservation organization with a remit beyond fisheries management, though it does share attributes with RFMOs. While included in this report, it is important to acknowledge it is technically not an RFMO.

- ^ https://www.fao.org/gfcm/en/

- ^ 1The agreement for establishment of GFCM was approved in 1949 and came into force in 1952. Previously ‘General Fisheries Council for the Mediterranean’, it became a Commission in 1997.

- ^ https://www.nafo.int/

- ^ https://nasco.int/

- ^ https://www.neafc.org/

- ^ NEAFC was established in 1959, but replaced with a new convention that entered into force in 1982 and has since been amended twice.

- ^ https://www.npfc.int/

- ^ http://www.seafo.org/

- ^ https://www.apsoi.org/

- ^ https://www.sprfmo.int/

- ^ The United States recently implemented its Import Provisions under the MMPA, requiring over 100 nations exporting fish and fish products to the U.S. to demonstrate that they have developed regulatory programs managing marine mammal bycatch “comparable in effectiveness” to those in the United States (81 FR 54389).

References

81 FR 54389 (2016). Fish and fish product import provisions of the marine mammal protection act. Final Rule. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 15 CFR 902 and 50 CFR 216.

Alverson D., et al. (1994) A global assessment of fisheries bycatch and discards. FAO fisheries technical paper. no. 339. Available at: http://www.fao.org/3/t4890e/T4890E00.htm#TOC.

Anderson R. C., Herrera M., Ilangakoon A. D., Koya K. M., Moazzam M., Mustika P. L., et al. (2020). Cetacean bycatch in Indian ocean tuna gillnet fisheries. Endangered. Species. Res. 41, 39–53. doi: 10.3354/esr01008

Babcock E. A., Pikitch E. K., Hudson C. G. (2003). How much observer coverage is enough to adequately estimate bycatch? (Miami, FL: Pew Institute of Ocean Science and Oceana. Report).

Ballance L. T., Gerrodette T., Lennert-Cody C., Pitman R. L., Squires D. (2021). A history of the tuna-dolphin problem: Successes, failures, and lessons learned. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 1700. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.754755

Brownell R. L. Jr., Reeves R. R., Read A. J., Smith B. D., Thomas P. O., Ralls K., et al. (2019). Bycatch in gillnet fisheries threatens critically endangered small cetaceans and other aquatic megafauna. Endangered. Species. Res. 40, 285–296. doi: 10.3354/esr00994

CCAMLR (2008a). “Precautionary catch limitation on euphausia superba in statistical division 58.4.1.” conservation measure 51-02.

CCAMLR (2008b). “Precautionary catch limitation on euphausia superba in statistical division 58.4.2.” conservation measure 51-03.

CCAMLR (2020a). “General measure for exploratory fisheries for euphausia superba in the convention area in the 2020/21 season.” conservation measure 51-04.

CCAMLR (2020b). “Limitation of by-catch in statistical division 58.5.2 in the 2018/19 season.” conservation measure 33-02.

Clark N. A., Ardron J. A., Pendleton L. H. (2015). Evaluating the basic elements of transparency of regional fisheries management organizations. Mar. Policy 57, 158–166. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2015.03.003

Clarke S., Sato M., Small C., Sullivan B., Inoue Y., Ochi D. (2014). Bycatch in longline fisheries for tuna and tuna-like species: A global review of status and mitigation measures. FAO fisheries and aquaculture technical paper, Vol. 588. 1–199.

Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) (2017). “Resolution 12.22: By-catch,” in Adopted by the Conference of the Parties at its 12th Meeting, Manila, October 2017. Available at: https://www.cms.int/sites/default/files/document/cms_cop12_res.12.22_bycatch_e.pdf.

Cox T. M., Lewison R. L., Žydelis R., Crowder L. B., Safina C., Read A. J. (2007). Comparing effectiveness of experimental and implemented bycatch reduction measures: The ideal and the real. Conserv. Biol. 21 (5), 1155–1164. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2007.00772.x

Crespo G. O., Dunn D. C., Gianni M., Gjerde K., Wright G., Halpin P. N. (2019). High-seas fish biodiversity is slipping through the governance net. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3 (9), 1273–1276. doi: 10.1038/s41559-019-0981-4

Cullis-Suzuki S., Pauly D. (2010). Failing the high seas: a global evaluation of regional fisheries management organizations. Mar. Policy 34 (5), 1036–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2010.03.002

Curtis K. A., Carretta J. V. (2020). ObsCovgTools: Assessing observer coverage needed to document and estimate rare event bycatch. Fish. Res. 225, 105493. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2020.105493

Dawson S. M., Slooten E. (2005). Management of gillnet bycatch of cetaceans in new Zealand. J. Cetacean. Res. Manage. 7 (1), 59.

De Bruyn P., Murua H., Aranda M. (2013). The precautionary approach to fisheries management: How this is taken into account by tuna regional fisheries management organisations (RFMOs). Mar. Policy 38, 397–406. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2012.06.019

Escalle L., Capietto A., Chavance P., Dubroca L., De Molina A. D., Murua H., et al. (2015). Cetaceans and tuna purse seine fisheries in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans: Interactions but few mortalities. Marine Ecology Progress Series 522, 255–268. doi: 10.1007/s10531-018-1672-1

Ewell C., Hocevar J., Mitchell E., Snowden S., Jacquet J. (2020). An evaluation of regional fisheries management organization at-sea compliance monitoring and observer programs. Mar. Policy 115, 103842. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.103842

Fader J. E., Elliott B. W., Read A. J. (2021). The challenges of managing depredation and bycatch of toothed whales in pelagic longline fisheries: Two US case studies. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 123. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.618031

FAO (1999a) International plan of action for conservation and management of sharks. Available at: http://www.fao.org/ipoa-sharks/background/about-ipoa-sharks/en/.

FAO (1999b) International plan of action for reducing incidental catch of seabirds in longline fisheries. international plan of action for the conservation and management of sharks. international plan of action for the management of fishing capacity. Available at: https://www.fao.org/3/x3170e/x3170e.pdf.

FAO (2009a) Fishing operations 2. best practices to reduce incidental catch of seabirds in capture fisheries. Available at: http://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/936cafe3-3e5b-5d15-8a86-3e80c69ffc34.

FAO (2009b) Guidelines to reduce Sea turtle mortality in fishing operations. Available at: http://www.fao.org/3/i0725e/i0725e00.htm.

FAO (2019) Monitoring the incidental catch of vulnerable species in Mediterranean and black Sea fisheries: Methodology for data collection. Available at: http://www.fao.org/publications/card/en/c/CA4991EN/.

FAO (2020) Regional fisheries management organizations and advisory bodies activities and developments 2000–2017. Available at: http://www.fao.org/3/ca7843en/CA7843EN.pdf.

FAO (2021) Fishing operations. guidelines to prevent and reduce bycatch of marine mammals in capture fisheries. Available at: http://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/cb2887en/.

FAO and ACCOBAMS (2018). Good practice guide for the handling of cetaceans caught incidentally in Mediterranean fisheries (Rome, Italy: FAO). Available at: https://www.fao.org/publications/card/en/c/CA0015EN.

GFCM (2012). “On the mitigation of incidental catches of cetaceans in the GFCM area of application.” GFCM/36/2012/2.

GFCM (2013). “on the establishment of a set of minimum standards for bottom-set gillnet fisheries for turbot and conservation of cetaceans in the black sea.” GFCM/37/2013/2.

GFCM (2019). “on enhancing the conservation of cetaceans in the GFCM area of application.” GFCM/43/2019/2.

Gilman E. L. (2011). Bycatch governance and best practice mitigation technology in global tuna fisheries. Mar. Policy 35 (5), 590–609. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2011.01.021

Gilman E., Passfield K., Nakamura K. (2012) Performance assessment of bycatch and discards governance by regional fisheries management organizations. IUCN report. Available at: https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/2012-034.pdf.

Gilman E., Passfield K., Nakamura K. (2014). Performance of regional fisheries management organizations: Ecosystem-based governance of bycatch and discards. Fish. Fish. 15 (2), 327–351. doi: 10.1111/faf.12021

Gomez G., Farquhar S., Bell H., Laschever E., Hall S. (2020). The IUU nature of FADs: Implications for tuna management and markets. Coast. Manage. 48 (6), 534–558. doi: 10.1080/08920753.2020.1845585

Haas B., Haward M., McGee J., Fleming A. (2019). The influence of performance reviews on regional fisheries management organizations. ICES. J. Mar. Sci. 76 (7), 2082–2089. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsz088

Haas B., McGee J., Fleming A., Haward M. (2020). Factors influencing the performance of regional fisheries management organizations. Mar. Policy 113, 103787. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103787

Hall M. A. (1998). An ecological view of the tuna–dolphin problem: impacts and trade-offs. Rev. Fish. Biol. Fish. 8 (1), 1–34. doi: 10.1023/A:1008854816580

Hall M. A. (1999). “Estimating the ecological impacts of fisheries: what data are needed to estimate bycatches,” in The international conference on integrated fisheries monitoring (Sydney, Australia. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organisation).

Hammond P. S., Francis T. B., Heinemann D., Long K. J., Moore J. E., Punt A. E., et al. (2021). Estimating the abundance of marine mammal populations. Front. Mar. Sci. 8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.735770

Harrison A. L., Costa D. P., Winship A. J., Benson S. R., Bograd S. J., Antolos M., et al. (2018). The political biogeography of migratory marine predators. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2 (10), 1571–1578. doi: 10.1038/s41559-018-0646-8

Heidrich K. N., Juan-Jordá M. J., Murua H., Thompson C. D., Meeuwig J. J., Zeller D. (2022). Assessing progress in data reporting by tuna regional fisheries management organizations. Fish. Fish 23, 1264–1281. doi: 10.1111/faf.12687

IATTC (n.d) Best practices for safe handling and release of cetaceans in longline fisheries. Available at: https://www.iattc.org/Downloads/Documents/USA_Best%20practices%20for%20safe%20handling%20and%20release%20of%20Cetaceans%20in%20longline%20fisheries.pdf.

ICCAT (2011). “Information collection and harmonization of data on by-catch and discards in ICCAT fisheries.” recommendation 11-10.

ICCAT (2018). Report of the standing committee on research and statistics (SCRS) (Madrid, Spain). Available at: https://www.iccat.int/Documents/Meetings/Docs/2018/REPORTS/2018_SCRS_REP_ENG.pdf.

IOTC (2017). “To prohibit the use of large-scale driftnets on the high seas in the IOTC area.” resolution 17/07.

IOTC (2021). “On an interim plan for rebuilding the Indian ocean yellowfin tuna stock in the IOTC area of competence.” resolution 21/01.

IOTC (2021a) Status of development and implementation of national plans of action for seabirds and sharks, and implementation of the FAO guidelines to reduce marine turtle mortality in fishing operations. Available at: https://www.iotc.org/science/status-of-national-plans-of-action-and-fao-guidelines.

IOTC (2021b) “Proposal to amend resolution 13/04: On the conservation of cetaceans”. Available at: https://www.iotc.org/documents/conservation-cetaceans-rep-korea-cf-res13-04.

IOTC (2021c). Proposal to amend resolution 13/04: On the conservation of cetaceans explanatory memorandum. Available at: https://iotc.org/documents/conservation-cetaceans-rep-korea-cf-res13-04.

IWC (2021) Bycatch. Available at: https://iwc.int/bycatch.

Joint T-RFMOs Bycatch Working Group (2019) Chair’s report of the 1st joint tuna RFMO bycatch working group meeting. Available at: https://www.iccat.int/Documents/meetings/docs/2019/reports/2019_JWGBY-CATCH_ENG.pdf.

Juan-Jordá M. J., Murua H., Arrizabalaga H., Dulvy N. K., Restrepo V. (2018). Report card on ecosystem-based fisheries management in tuna regional fisheries management organizations. Fish. Fish. 19 (2), 321–339. doi: 10.1111/faf.12256

Kirby D. S., Ward P. (2014). Standards for the effective management of fisheries bycatch. Mar. Policy 44, 419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2013.10.008

Kiszka J. J., Moazzam M., Boussarie G., Shahid U., Khan B., Nawaz R. (2021). Setting the net lower: A potential low-cost mitigation method to reduce cetacean bycatch in drift gillnet fisheries. Aquat. Conservation.: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst 31 (11), 3111–3119.

Kiszka J., Muir C., Poonian C., Cox T. M., Amir O. A., Bourjea J., et al. (2009). Marine mammal bycatch in the southwest Indian ocean: Review and need for a comprehensive status assessment. Western. Indian Ocean. J. Mar. Sci. 7 (2), 119–136. doi: 10.1002/aqc.3706

Komoroske L. M., Lewison R. L. (2015). Addressing fisheries bycatch in a changing world. Front. Mar. Sci. 2, 83. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2015.00083

Lenfest Ocean Program (2022) Marine mammal bycatch working group. Available at: https://www.lenfestocean.org/en/research-projects/developing-recommendations-to-estimate-bycatch-for-the-marine-mammal-protection-act.

Lewison R. L., Crowder L. B., Read A. J., Freeman S. A. (2004). Understanding impacts of fisheries bycatch on marine megafauna. Trends Ecol. Evol. 19 (11), 598–604. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2004.09.004

Lewison R. L., Crowder L. B., Wallace B. P., Moore J. E., Cox T., Zydelis R., et al. (2014). Global patterns of marine mammal, seabird, and sea turtle bycatch reveal taxa-specific and cumulative megafauna hotspots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111 (14), 5271–5276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318960111

Lewison R. L., Soykan C. U., Cox T., Peckham H., Pilcher N., LeBoeuf N., et al. (2011). Ingredients for addressing the challenges of fisheries bycatch. Bull. Mar. Sci. 87 (2), 235–250. doi: 10.5343/bms.2010.1062

Lodge M., et al. (2007) Recommended best practices for regional fisheries management organizations. report. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/sd-roundtable/papersandpublications/39374297.pdf.

Moore J. E., Cox T. M., Lewison R. L., Read A. J., Bjorkland R., McDonald S. L., et al. (2010). An interview-based approach to assess marine mammal and sea turtle captures in artisanal fisheries. Biol. Conserv. 143 (3), 795–805. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2009.12.023

Moore J. E., Wallace B. P., Lewison R. L., Žydelis R., Cox T. M., Crowder L. B. (2009). A review of marine mammal, sea turtle and seabird bycatch in USA fisheries and the role of policy in shaping management. Mar. Policy 33 (3), 435–451. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2008.09.003

Northridge S. P. (1996). A review of marine mammal bycatch observer schemes with recommendations for best practice. JNCC report 219 (Aberdeen, United Kingdom: Joint Nature Conservation Committee).

NPFC (2019). “Conservation and management measure for sablefish in the northeastern pacific ocean”. CMM 2019–10.

O'Leary B. C., Hoppit G., Townley A., Allen H. L., McIntyre C. J., Roberts C. M. (2020). Options for managing human threats to high seas biodiversity. Ocean. Coast. Manage. 187, 105110. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2020.105110

Pace R. M. III, Cole T. V., Henry A. G. (2014). Incremental fishing gear modifications fail to significantly reduce large whale serious injury rates. Endangered. Species. Res. 26 (2), 115–126. doi: 10.3354/esr00635

Petersson M. T. (2020). Transparency in global fisheries governance: The role of non-governmental organizations. Mar. Policy 104128. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104128

Pew Charitable Trusts (2015) Estimating the use of FADS around the world. Available at: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2015/11/estimating-the-use-of-fads-around-the-world.

Pew Charitable Trusts (2022) Fisheries managers around the world should advance on electronic monitoring programs in 2022. Available at: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2022/05/27/fisheries-managers-around-the-world-should-advance-on-electronic-monitoring-programs-in-2022.

Phillips R. A., Gales R., Baker G. B., Double M. C., Favero M., Quintana F., et al. (2016). The conservation status and priorities for albatrosses and large petrels. Biol. Conserv. 201, 169–183. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2016.06.017

Read A. J., Drinker P., Northridge S. (2006). Bycatch of marine mammals in US and global fisheries. Conserv. Biol. 20 (1), 163–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00338.x

Reeves R. R., McClellan K., Werner T. B. (2013). Marine mammal bycatch in gillnet and other entangling net fisheries 1990 to 2011. Endangered. Species. Res. 20 (1), 71–97. doi: 10.3354/esr00481

Shahid U., Khan M. M., Nawaz R., Dimmlich W., Kiszka J. (2015). An update on the assessment of sea turtle bycatch in tuna gillnet fisheries of Pakistan (Arabian Sea), Vol. 1. 1–4, IOTC 2015-WPEB-11-47-Rev.

SIOFA (2021). “Conservation and management measure for the management of demersal stocks in the agreement area (Management of demersal stocks)”. CMM 2021/15

SIOFA. (2022). Report of the fourth meeting of the southern Indian ocean fisheries agreement (SIOFA) scientific committee (SC) stock assessment and ecological risk assessment working group (SERAWG). Available at: https://www.apsoi.org/sites/default/files/documents/meetings/SERAWG4-Final-Report.pdf.

Small C. J. (2005). Regional fisheries management organisations: their duties and performance in reducing bycatch of albatrosses and other species (Cambridge, UK: BirdLife International).

SPRFMO (2020). “Conservation and management measure for exploratory fishing for toothfish by Chilean-flagged vessels in the SPRFMO convention area”. CMM 14d-2020.

SPRFMO (2021) A summary of current SPRFMO bycatch records (Including species of concern). SC9-DOC 11. Available at: https://www.sprfmo.int/assets/2021-SC9/SC9-Doc11-Current-SPRFMO-by-catch-records-summary.pdf.

SPRFMO (2022a). “Conservation and management measure for the management of bottom fishing in the SPRFMO convention area”. CMM 03-2022.

SPRFMO (2022b). “Standards for the collection, reporting, verification and exchange of data”. CMM 02-2022.

Squires D., Ballance L. T., Dagorn L., Dutton P. H., Lent R. (2021). Mitigating bycatch: Novel insights to multidisciplinary approaches. Front. Mar. Sci. 8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.613285

Swimmer Y., Zollett E. A., Gutierrez A. (2020). Bycatch mitigation of protected and threatened species in tuna purse seine and longline fisheries. Endangered. Species. Res. 43, 517–542. doi: 10.3354/esr01069

UNCLOS (1982) United nations convention on the law of the Sea. Available at: https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf.

UNFSA (1995) The united nations agreement for the implementation of the provisions of the united nations convention on the law of the Sea of 10 December 1982 relating to the conservation and management of straddling fish stocks and highly migratory fish stocks. Available at: https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/convention_overview_fish_stocks.htm.

Wade P. R. (1998). Calculating limits to the allowable human-caused mortality of cetaceans and pinnipeds. Mar. Mammal. Sci. 14 (1), 1–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.1998.tb00688.x

Wade P. R., Long K. J., Francis T. B., Punt A. E., Hammond P. S., Heinemann D., et al. (2021). Best practices for assessing and managing bycatch of marine mammals. Front. Mar. Sci 8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.757330

WCPFC (2011). “Conservation and management measure to address the impact of purse seine activity on cetaceans.” CMM 11-03.

WCPFC (2021a) “Best practices for the safe handling and release of cetaceans.” adopted at the 18th regular session of the commission. Available at: https://www.wcpfc.int/doc/supplcmm-2011-03/best-practices-safe-handling-and-release-cetaceans.

WCPFC (2021b). An update on available data on cetacean interactions in the WCPFC longline and purse seine fisheries. seventeenth regular session of the scientific committee. WCPFC-SC17-2021/ST-IP-10.

Werner T. B., Northridge S., Press K. M., Young N. (2015). Mitigating bycatch and depredation of marine mammals in longline fisheries. ICES. J. Mar. Sci. 72 (5), 1576–1586. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsv092

Williams R., Burgess M. G., Ashe E., Gaines S. D., Reeves R. R. (2016). US Seafood import restriction presents opportunity and risk. Science 354 (6318), 1372–1374. doi: 10.1126/science.aai8222

Keywords: cetaceans, bycatch, RFMO, marine mammals, international fisheries

Citation: Elliott B, Tarzia M and Read AJ (2023) Cetacean bycatch management in regional fisheries management organizations: Current progress, gaps, and looking ahead. Front. Mar. Sci. 9:1006894. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.1006894

Received: 29 July 2022; Accepted: 21 November 2022;

Published: 22 February 2023.

Edited by:

Ellen Hines, San Francisco State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Gianna Minton, Megaptera Marine Conservation, NetherlandsBarry Baker, University of Tasmania, Australia

Copyright © 2023 Elliott, Tarzia and Read. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Brianna Elliott, QnJpYW5uYS5lbGxpb3R0QGR1a2UuZWR1

Brianna Elliott

Brianna Elliott Marguerite Tarzia

Marguerite Tarzia Andrew J. Read

Andrew J. Read