- 1The Peopled Seas Initiative, North Vancouver, BC, Canada

- 2People and the Ocean Specialist Group, Commission on Environmental, Economic and Social Policy, International Union for Conservation of Nature, Gland, Switzerland

- 3School of Public Policy and Global Affairs, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Equity and Justice in the Ocean

Equity and justice considerations have risen to the surface in policy deliberations, management decisions, and program design related to marine conservation, fisheries management, and blue economy development. These topics have been brought to the forefront by academic documentation of social justice and distributional issues across these different marine policy realms (Kittinger et al., 2017; Cohen et al., 2019; Martin et al., 2019; Armstrong, 2020; Bennett et al., 2021a) and coinciding civil society efforts to raise the profile of the social injustices facing small-scale fishers, coastal communities, different genders, and diverse racial and ethnic groups (Isaacs, 2019; Johnson, 2020; Gustavsson et al., 2021). Academic and civil society groups and individuals have coined a number of catch phrases to refer to the relationship between equity, justice, and the oceans - including blue justice, marine justice, ocean justice and ocean equity (Martin et al., 2019; Armstrong, 2020; Österblom et al., 2020; Bennett et al., 2021a). Small-scale fisheries organizations, for example, coined the now popular term ‘blue justice’ to refer to the effects of blue growth and industrial fisheries on the rights, resources and livelihoods of small-scale fishers and coastal communities (Cohen et al., 2019; Isaacs, 2019; Bennett et al., 2021a; Jentoft et al., 2022). Scholars also recently proposed ‘marine justice’ as an academic concept, a paradigm, and a movement that merges concerns for the marine environment and environmental justice (Widener, 2018; Martin et al., 2019). The idea of ‘ocean equity’ emerged in a 2020 report of the High Level Panel on the Sustainable Ocean Economy titled ‘Towards Ocean Equity’ that highlighted the need for the burgeoning ocean economy to be inclusive and account for equity in the distribution of benefits (Bennett et al., 2019b; Österblom et al., 2020). Marine biologist and conservationist Ayana Elizabeth Johnson uses the phrase ‘ocean justice’ to underscore the importance of paying attention to climate justice and racial justice issues in ocean conservation (Johnson, 2020).

While somewhat different in their history and formulation, the proponents behind each of these catch phrases share a common concern for the need to urgently address emergent equity and justice issues in ocean governance and management. This growing interest in equity and justice in the oceans is positive progress from just a few years ago when these topics were still peripheral in ocean policy deliberations and insufficiently considered in programs and funding focused on oceans and sustainability (Bennett, 2018). Globally, many ocean-focused conservation and development government agencies, non-governmental organizations, and funders have become quite interested in how to embed and operationalize equity and justice in their work (Österblom et al., 2020; Bennett et al., 2021b). Yet, these organizations still often lack the foundational knowledge, mandate, capacity, and diversity to be able to adequately account for and address equity and justice issues. This opinion editorial provides six recommendations for how marine conservation and development organizations can establish a strong internal foundation for mainstreaming equity and justice issues in external marine policies, programs, practices and portfolios.

Recommendations for Mainstreaming Equity and Justice in Ocean Organizations, Policy and Practice

Develop Awareness of Past Equity and Justice Issues in Marine Policy Spheres Where the Organization Works

History is a good teacher. For example, research has shown how the creation of marine protected areas has marginalized, displaced and socially impacted local communities, small-scale fishers, and Indigenous populations (Cross, 2015; Hill, 2017; Kamat, 2018; Sowman and Sunde, 2018). A recent review of the literature on ocean-based economic development provides insights into 10 social issues that require attention: tenure and access, environmental justice, ecosystem services, small-scale fisheries, food security, economic benefits, socio-cultural impacts, gender equity, human rights, and inclusive governance (Bennett et al., 2021a). Past fisheries management has been critiqued for failing to adequately account for social considerations, leading to corporate concentration and inequitable distribution of economic benefits, and undermining Indigenous and human rights (Kittinger et al., 2017; Pinkerton, 2017). Marine spatial planning processes have been shown to provide a voice to powerful actors, while excluding groups who were already marginalized (Flannery et al., 2018; Clarke and Flannery, 2019). Coastal climate adaptation processes can reinforce and entrench pre-existing inequalities for racially diverse groups (Hardy et al., 2017). Familiarity with historical social justice issues in marine conservation, fisheries management, or the ocean economy can provide important insights into how to avoid these issues in the future.

Explore How Equity and Justice Are Defined and Can be Operationalized in Marine Policy and Practice

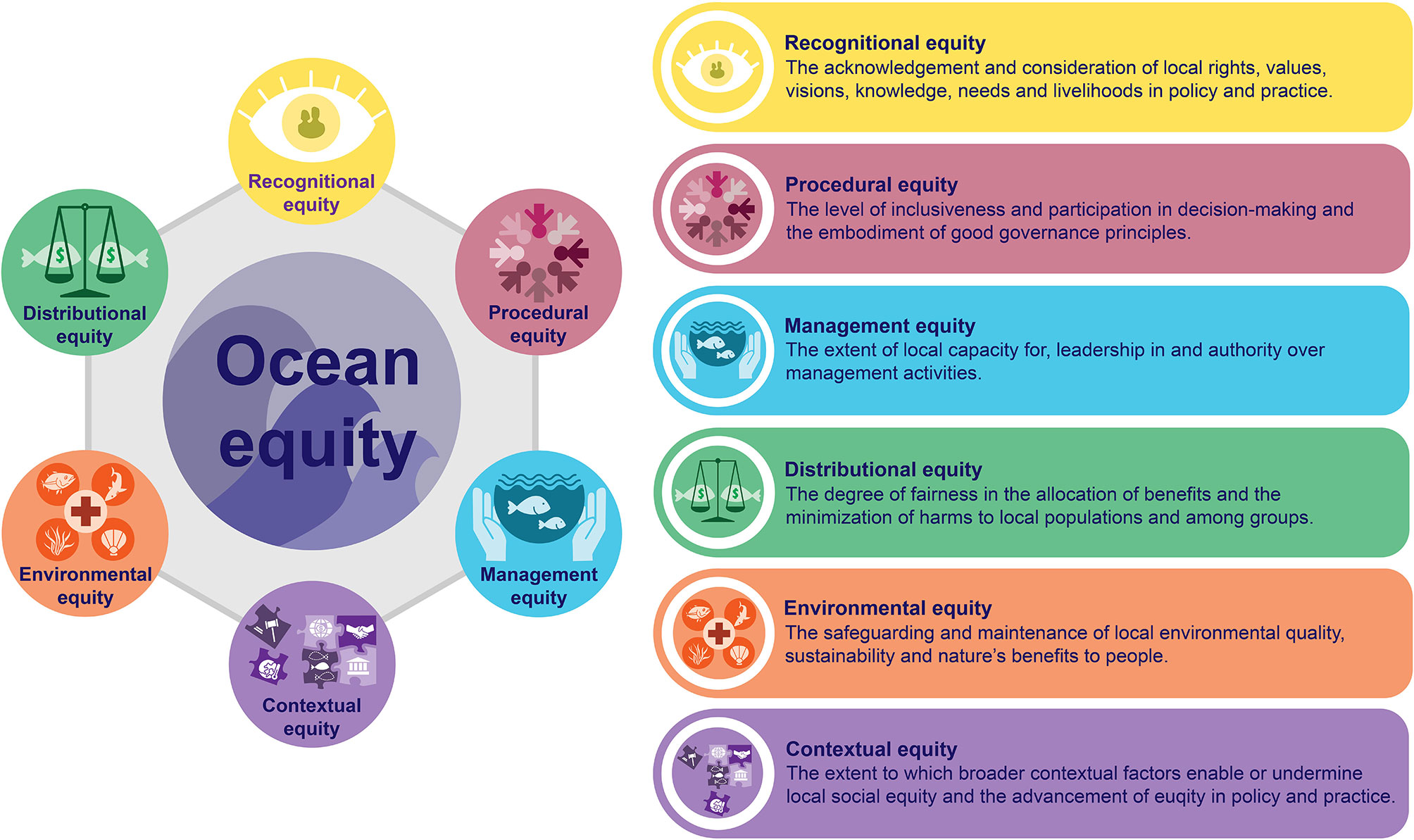

Another step for organizations to take is to develop a foundational understanding of what equity and justice mean, and how these norms might be applied in marine policies and programs. Equity and justice refer, in general terms, to right and fair treatment of people – including in the processes, application and outcomes of a public policy or organizational practice. The academic literature related to conservation, environmental management and the oceans have proposed various dimensions that are integral to equity or justice, including recognitional, procedural, distributional, management, environmental, and contextual dimensions (McDermott et al., 2013; Pascual et al., 2014; Schreckenberg et al., 2016; Zafra-Calvo et al., 2017; Bennett et al., 2019a; Bennett et al., 2021b; Engen et al., 2021). Drawing insights from these literatures, for example, the various dimensions of ‘ocean equity’ might be defined as follows:

a. Recognitional equity: the acknowledgement and consideration of local rights, values, visions, knowledge, needs and livelihoods in policy and practice;

b. Procedural equity: the level of inclusiveness and participation in decision-making, and the embodiment of good governance principles (e.g., transparency, accountability, responsiveness, consensus orientation and efficiency);

c. Distributional equity: the degree of fairness in the allocation of benefits, and the minimization of harms to local populations and among groups;

d. Management equity: the extent of local capacity for, leadership in, and authority over management activities;

e. Environmental equity: the safeguarding and maintenance of local environmental quality, sustainability, and nature’s benefits to people; and,

f. Contextual equity: the extent to which broader contextual factors (e.g., economic, governance, social structures, climate change, environmental conditions, rule of law) enable or undermine local social equity and the advancement of equity in policy and practice (see Figure 1).

The application of each dimension of ocean equity will, of course, differ across social, cultural, economic, historical and political contexts (Dawson et al., 2018; Gurney et al., 2021). Thus ocean organizations should convene strategic teams and inclusive conversations to consider the practical implications and operationalization of each dimension for the design of policies, practices, programs, or funding portfolios for the different marine policies spheres that are within their purview.

Mainstream Equity and Justice in Organizational Policies, Practices, Programs, and Portfolios

Ocean-focused government agencies, non-governmental organizations, and funders should then consider how to explicitly incorporate social equity and justice considerations and actions into their future policy frameworks, management practices, programmatic objectives, and funding portfolios. Governments, for example, might ensure that national laws and policy frameworks mandate the equitable distribution of economic benefits in the blue economy (Cisneros-Montemayor et al., 2019; Österblom et al., 2020) or require consideration of access rights and fair allocation of benefits when fisheries management measures are implemented (Kittinger et al., 2017; Bennett et al., 2019a). Non-governmental organizations should integrate equity and justice considerations (e.g., rights, inclusion, human well-being, local initiatives) into the objectives of marine programs and projects or articulate a code of conduct with social principles that teams and programs should embody (Bennett et al., 2017; Lutz, 2017; Blue Nature Alliance, 2021). Ocean funders have significant power to influence programs and actions on the ground, and thus a corresponding responsibility to examine whether and how their funding portfolio is advancing or undermining social equity or justice in the pursuit of sustainability. Marine conservation efforts and fisheries management initiatives may, for instance, further marginalize local groups, undermine local rights, and entrench inequities if inadequate funding is provided to support enabling activities such as participatory decision-making processes, analysis of the social context, and gender mainstreaming practices. Ocean-focused non-governmental organizations and funders may also elect to prioritize specific issues such as food security in fisheries management, gender inclusion in the blue economy, or Indigenous-led marine conservation through their programs and funding. All ocean-focused organizations should establish their own tracking and accountability mechanisms to ensure they are taking action and achieving their stated objectives.

Increase Organizational Human Dimensions Capacity and Ability to Think Socially

Considering equity requires being able to think socially – to understand and be able to apply human dimensions topics such as rights and tenure, culture, good governance, and human well-being. However, many ocean-focused conservation organizations, government agencies, and foundations have insufficient capacity in the human dimensions. These organizations often hire individuals trained in biology or fisheries, and their education and past experience thus leaves them ill-equipped to consider the people side of ocean policy and practice. A first step is to hire personnel with training, experience and knowledge of working with people and considering the human dimensions in programmatic decisions. Another way to increase human dimensions capacity is to develop the ability of individuals at all levels within the organization to think socially, and to apply that thinking to real world practice. This type of thinking is required at all levels from programmatic staff right up to board members. Marine policy-makers and practitioners need to be able to consider responses to questions such as the following: What is the difference between a stakeholder and a rights-holder, and how should these two groups be treated differently? How can local cultural norms, practices and values be incorporated into management? What is required to practice inclusive decision-making and good governance? How might this initiative support or undermine human well-being for local communities and different groups? Ocean-focused organizations should provide capacity-building opportunities for staff to learn about the human dimensions topics and promote spaces to practice designing solutions that incorporate social thinking (Shapira et al., 2017).

Support Marine Social Science Research and Engage With Evidence Regarding the Human Dimensions

It is often claimed that good environmental decisions require adequate scientific evidence. As much of the coastal and marine environment is populated and used by local people, evidence-informed decision-making processes for the oceans should rely on insights from both the natural and social sciences. The marine social sciences include a broad set of disciplines, theories, methods and analytical approaches that can be used to rigorously study the human dimensions of the oceans (Arbo et al., 2018; Bennett, 2019; McKinley et al., 2020). There are a number of social science topics that are important to comprehend to be able address each aspect of equity or justice. Addressing recognitional equity or justice, for instance, will benefit from research that documents tenure and rights, assesses diverse perspectives on a policy, examines gendered differences in resource use, explores cultural values, or investigates current livelihoods. Social science assessments of legal and policy frameworks, stakeholder engagement and collaborative management processes, or levels of good governance [transparency, accountability, rule of law, free prior and informed consent (FPIC), etc.] can be instructive for advancing procedural equity or justice. Research on the current status of human well-being, socio-economic impacts of initiatives, or potential livelihood opportunities will help to make decisions to advance distributional equity and justice. Social indicators can also be developed to track how well different aspects of equity and justice are being addressed in ocean policies and programs (Zafra-Calvo et al., 2017; Bennett et al., 2021b; Engen et al., 2021). Moreover, without insights from the marine social sciences, ocean policy, programmatic, and funding decisions are often made ‘in the dark’ with regards to the social context and the equity and justice implications for coastal populations. These decisions may even be producing more harm than good.

Commit to Internal Organizational Equity, Diversity and Inclusion as a Foundation for External Equity and Justice Work

Institutional histories of colonialism, racism and sexism have led to the uplifting of some and exclusion of other people of various races, sexes, geographies and backgrounds in ocean organizations (Smith et al., 2017; Ahmadia et al., 2021; Belhabib, 2021). This has meant that the ocean science and conservation communities have historically lacked, and continue to lack, diversity (Smith et al., 2017; Ahmadia et al., 2021; Belhabib, 2021). Yet, equity, diversity and inclusion within ocean organizations are fundamental to be able to gain diverse perspectives, develop shared understandings, and produce transformative solutions to address ocean sustainability challenges, and ocean equity and justice issues. Thus, ocean organizations must work and take actions to address barriers to diverse representation, genuine inclusion, and equitable treatment. Diversity means having a mix of people within an organization who represent a wide range of abilities, experiences, knowledge and strengths due to their differences, which may include race, ethnicity, national origin, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, socioeconomic background, education level, physical and mental ability, age, physical appearance, and political views. Hiring processes need to be attentive to bias and seek to increase diversity within an organization’s staffing and leadership roles to ensure broad and intersectional representation. In particular, underrepresented groups and people from those places, communities, and groups who are involved in or affected by an ocean organization’s policies and practices should be better represented within ocean organizations. Creating a genuine culture of inclusion within organizations requires going deeper to ensure that diverse individuals feel welcome and valued. Practices to increase inclusiveness might include, for example, conducting bias and anti-discrimination training, ensuring effective harassment policies and responses are in place, creating an environment that accepts diverse identities and respects divergent opinions, ensuring everyone has an opportunity to speak in meetings, engaging different communication styles, and recognizing distinct contributions to the workplace (Bailey et al., 2020; National Audubon Society, 2020). Equitable treatment in the workplace means that rates of promotion, wages and treatment should be fair for groups of diverse genders, races and abilities (Jones and Solomon, 2019). Attention to inclusion and equitable treatment will improve retention and advancement of diverse individuals within ocean organizations (Smith et al., 2017). Ultimately, internal teams and processes of ocean organizations should aim to be a mirror of external intentions.

Summary and Concluding Remarks

Addressing equity and justice has become integral to ocean sustainability efforts. Many ocean-focused organizations – including government agencies, non-governmental organizations, and funders – are thus interested in advancing equity and justice in their policies, practices, programs, and portfolios. This opinion paper makes 6 recommendations to ensure ocean organizations have the foundational knowledge, mandate, capacity, and diversity necessary to carry out this work. These recommendations include the following: 1) Develop awareness of past equity and justice issues in marine policy spheres where the organization works; 2) Explore how equity and justice are defined and can be operationalized in marine policy and practice; 3) Mainstream equity and justice in organizational policies, practices, programs, and portfolios; 4) Increase organizational human dimensions capacity and ability to think socially; 5) Support marine social science research and engage with evidence regarding the human dimensions; and, 6) Commit to internal organizational equity, diversity and inclusion as a foundation for external equity and justice work. Concerted efforts are needed to ensure that equity and justice are mainstreamed within marine policies and practice. Creating strong organizational foundations is an important starting place and enabler for advancing equity and justice in the ocean.

Author Contributions

NB is solely responsible for the design, research, writing and editing of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The figure was designed by Ravi Maharaj.

References

Ahmadia G. N., Cheng S. H., Andradi-Brown D. A., Baez S. K., Barnes M. D., Bennett N. J., et al. (2021). Limited Progress in Improving Gender and Geographic Representation in Coral Reef Science. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 731037. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.731037

Arbo P., Knol M., Linke S., St. Martin K. (2018). The Transformation of the Oceans and the Future of Marine Social Science. Maritime Stud. 17, 295–304. doi: 10.1007/s40152-018-0117-5

Armstrong C. (2020). Ocean Justice: SDG 14 and Beyond. J. Global Ethics 16, 239–255. doi: 10.1080/17449626.2020.1779113

Bailey K., Morales N., Newberry M. (2020). Inclusive Conservation Requires Amplifying Experiences of Diverse Scientists. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 1294–1295. doi: 10.1038/s41559-020-01313-y

Belhabib D. (2021). Ocean Science and Advocacy Work Better When Decolonized. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 5, 709–710. doi: 10.1038/s41559-021-01477-1

Bennett N. J. (2018). Navigating a Just and Inclusive Path Towards Sustainable Oceans. Mar. Policy 97, 139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2018.06.001

Bennett N. J. (2019). Marine Social Science for the Peopled Seas. Coastal Manage. 47, 244–252. doi: 10.1080/08920753.2019.1564958

Bennett N. J., Blythe J., Cisneros-Montemayor A. M., Singh G. G., Sumaila U. R. (2019a). Just Transformations to Sustainability. Sustainability 11, 3881. doi: 10.3390/su11143881

Bennett N. J., Blythe J., White C. S., Campero C. (2021a). Blue Growth and Blue Justice: Ten Risks and Solutions for the Ocean Economy. Mar. Policy 125, 104387. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104387

Bennett N. J., Cisneros-Montemayor A. M., Blythe J., Silver J. J., Singh G., Andrews N., et al. (2019b). Towards a Sustainable and Equitable Blue Economy. Nat. Sustain 2, 991–993. doi: 10.1038/s41893-019-0404-1

Bennett N. J., Katz L., Yadao-Evans W., Ahmadia G. N., Atkinson S., Ban N. C., et al. (2021b). Advancing Social Equity in and Through Marine Conservation. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 711538. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.711538

Bennett N. J., Teh L., Ota Y., Christie P., Ayers A., Day J. C., et al. (2017). An Appeal for a Code of Conduct for Marine Conservation. Mar. Policy 81, 411–418. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2017.03.035

Blue Nature Alliance (2021). Code of Conduct. In: Blue Nature Alliance. Available at: https://www.bluenaturealliance.org/code-of-conduct (Accessed January 12, 2022).

Cisneros-Montemayor A. M., Moreno-Báez M., Voyer M., Allison E. H., Cheung W. W. L., Hessing-Lewis M., et al. (2019). Social Equity and Benefits as the Nexus of a Transformative Blue Economy: A Sectoral Review of Implications. Mar. Policy 109, 103702. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103702

Clarke J., Flannery W. (2019). The Post-Political Nature of Marine Spatial Planning and Modalities for Its Re-Politicisation. J. Environ. Policy Plann. 0, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/1523908X.2019.1680276

Cohen P. J., Allison E. H., Andrew N. L., Cinner J., Evans L. S., Fabinyi M., et al. (2019). Securing a Just Space for Small-Scale Fisheries in the Blue Economy. Front. Mar. Sci. 6, 171. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00171

Cross H. (2015). Displacement, Disempowerment and Corruption: Challenges at the Interface of Fisheries, Management and Conservation in the Bijagós Archipelago, Guinea-Bissau. Oryx 50, 693–701. doi: 10.1017/S003060531500040X

Dawson N., Martin A., Danielsen F. (2018). Assessing Equity in Protected Area Governance: Approaches to Promote Just and Effective Conservation. Conserv. Lett. 11, e12388. doi: 10.1111/conl.12388

Engen S., Hausner V. H., Gurney G. G., Broderstad E. G., Keller R., Lundberg A. K., et al. (2021). Blue Justice: A Survey for Eliciting Perceptions of Environmental Justice Among Coastal Planners’ and Small-Scale Fishers in Northern-Norway. PloS One 16, e0251467. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251467

Flannery W., Healy N., Luna M. (2018). Exclusion and Non-Participation in Marine Spatial Planning. Mar. Policy 88, 32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2017.11.001

Gurney G. G., Mangubhai S., Fox M., Kiatkoski Kim M., Agrawal A. (2021). Equity in Environmental Governance: Perceived Fairness of Distributional Justice Principles in Marine Co-Management. Environ. Sci. Policy 124, 23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2021.05.022

Gustavsson M., Frangoudes K., Lindström L., Ávarez M. C., de la Torre Castro M. (2021). Gender and Blue Justice in Small-Scale Fisheries Governance. Mar. Policy 133, 104743. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104743

Hardy R. D., Milligan R. A., Heynen N. (2017). Racial Coastal Formation: The Environmental Injustice of Colorblind Adaptation Planning for Sea-Level Rise. Geoforum 87, 62–72. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.10.005

Hill A. (2017). Blue Grabbing: Reviewing Marine Conservation in Redang Island Marine Park, Malaysia. Geoforum 79, 97–100. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.12.019

Isaacs M. (2019). Is the Blue Justice Concept a Human Rights Agenda? Available at: http://repository.uwc.ac.za/xmlui/handle/10566/5087 (Accessed January 6, 2020).

Jentoft S., Chuenpagdee R., Said A. B., Isaacs M. (2022). “Blue Justice,” in Small-Scale Fisheries in a Sustainable Ocean Economy (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing).

Johnson A. E. (2020). Ocean Justice: Where Social Equity and the Climate Fight Intersect. Available at: https://e360.yale.edu/features/ocean-justice-where-social-equity-and-the-climate-fight-intersect (Accessed June 11, 2021).

Jones M. S., Solomon J. (2019). Challenges and Supports for Women Conservation Leaders. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 1, e36. doi: 10.1111/csp2.36

Kamat V. R. (2018). Dispossession and Disenchantment: The Micropolitics of Marine Conservation in Southeastern Tanzania. Mar. Policy 88, 261–268. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2017.12.002

Kittinger J. N., Teh L. C. L., Allison E. H., Bennett N. J., Crowder L. B., Finkbeiner E. M., et al. (2017). Committing to Socially Responsible Seafood. Science 356, 912–913. doi: 10.1126/science.aam9969

Lutz S. (2017)Blue Carbon Code of Conduct. In: GEF Blue Forests Project. Available at: https://news.gefblueforests.org/blue-carbon-code-of-conduct (Accessed January 16, 2019).

Martin J. A., Gray S., Aceves-Bueno E., Alagona P., Elwell T. L., Garcia A., et al. (2019). What Is Marine Justice? J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 9, 234–243. doi: 10.1007/s13412-019-00545-0

McDermott M., Mahanty S., Schreckenberg K. (2013). Examining Equity: A Multidimensional Framework for Assessing Equity in Payments for Ecosystem Services. Environ. Sci. Policy 33, 416–427. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2012.10.006

McKinley E., Acott T., Yates K. L. (2020). Marine Social Sciences: Looking Towards a Sustainable Future. Environ. Sci. Policy 108, 85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2020.03.015

National Audubon Society. (2020). Equity Diversity and Inclusion How-To Guide: Guide for Incorporating Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Into Chapter Partnerships, Programs and Culture (Washington, DC: National Audubon Society). Available at: https://www.hillcountryalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Audubon-Society-EDI_Chapter_How-To_10-2.pdf (Accessed January 11, 2022).

Österblom H., Wabnitz C. C. C., Tladi D., Allison E. H., Arnaud-Haond S., Bebbington J., et al. (2020). Towards Ocean Equity (Washington, DC: World Resources Institute).

Pascual U., Phelps J., Garmendia E., Brown K., Corbera E., Martin A., et al. (2014). Social Equity Matters in Payments for Ecosystem Services. BioScience 64, 1027–1036. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biu146

Pinkerton E. (2017). Hegemony and Resistance: Disturbing Patterns and Hopeful Signs in the Impact of Neoliberal Policies on Small-Scale Fisheries Around the World. Mar. Policy 80, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2016.11.012

Schreckenberg K., Franks P., Martin A., Lang B. (2016). Unpacking Equity for Protected Area Conservation. Parks 22, 11–26. doi: 10.2305/IUCN.CH.2016.PARKS-22-2KS.en

Shapira H., Ketchie A., Nehe M. (2017). The Integration of Design Thinking and Strategic Sustainable Development. J. Cleaner Production 140, 277–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.10.092

Smith N. S., Côté I. M., Martinez-Estevez L., Hind-Ozan E. J., Quiros A. L., Johnson N., et al. (2017). Diversity and Inclusion in Conservation: A Proposal for a Marine Diversity Network. Front. Mar. Sci. 4, 234. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2017.00234

Sowman M., Sunde J. (2018). Social Impacts of Marine Protected Areas in South Africa on Coastal Fishing Communities. Ocean Coastal Manage. 157, 168–179. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2018.02.013

Widener P. (2018). Coastal People Dispute Offshore Oil Exploration: Toward a Study of Embedded Seascapes, Submersible Knowledge, Sacrifice, and Marine Justice. Environ. Sociol 4, 405–418. doi: 10.1080/23251042.2018.1441590

Keywords: ocean equity, ocean justice, blue justice, marine justice, Ocean governance, Marine policy, marine conservation, ocean sustainability

Citation: Bennett NJ (2022) Mainstreaming Equity and Justice in the Ocean. Front. Mar. Sci. 9:873572. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.873572

Received: 11 February 2022; Accepted: 30 March 2022;

Published: 20 April 2022.

Edited by:

Annette Breckwoldt, Leibniz Centre for Tropical Marine Research (LG), GermanyReviewed by:

Samiya Ahmed Selim, Leibniz Centre for Tropical Marine Research (LG), GermanyCopyright © 2022 Bennett. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nathan J Bennett, bmF0aGFuLmouYmVubmV0dC4xQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Nathan J. Bennett

Nathan J. Bennett