- 1Marine and Environmental Sciences Centre – Lisbon University (MARE-UL), Lisboa, Portugal

- 2Seascape Consultants, Ltd., Romsey, United Kingdom

- 3Faculty of Sciences of the University of Lisbon, Lisboa, Portugal

An ecosystem-based forward-looking vision for the global ocean, encompassing ocean health and productivity, ecosystem integrity and resilience, incorporating area beyond national jurisdiction, is fundamental. A vision which is holistic and universally acceptable to guide future sustainable ocean policies, plans and programmes (PPPs). We argue that Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) is the best available framework to develop such a vision and its suitability for this purpose should be recognised within the on-going process to negotiate an International Legally Binding Instrument (ILBI) for the conservation and sustainable use of Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ Agreement). This perspective paper justifies why such an ecosystem-based Global Ocean Vision is essential. It then describes the key characteristics it must integrate and how it can be elaborated in the framework of a collective SEA within the BBNJ process. We advocate expanding text in Part I General Provisions of the draft BBNJ Agreement to include development of such a global ocean vision. We conclude by highlighting the opportunity and timeliness of this proposal, with the fifth session of the IGC of BBNJ tentatively scheduled for August 2022.

Introduction – The Need for an Ecosystem Based Global Ocean Vision Under BBNJ

The ocean is the largest ecosystem on Earth, covering more than two thirds of the planet’s surface and encompassing 99% of all the habitable space for life on Earth (IPCC, 2019a). We rely on the continued supply of ecosystem services provided by a healthy ocean (e.g., IPBES, 2019; SCBD, 2020; UN, 2021), whose use must take place within the planetary boundaries of a sustainable development for humankind (Rockström et al., 2009), ensuring ocean ecosystems remain sufficiently intact and resilient to human disturbance (Rockström et al., 2021). However, that is not our current global trajectory (Steffen et al., 2015). The ocean is changing fast in the Anthropocene: warming, deoxygenating and acidifying. Eutrophication and other types of pollution, changing oceanographic conditions, and concomitant effects on biotic communities, such as species migrations and die-off, are increasingly evident as a direct combined result of human activities (UN, 2021; United Nations Environment Programme, 2021; IOC-UNESCO, 2022). The growing range of maritime economic sectors with a direct or indirect link to the ocean (e.g., Boschen-Rose et al., 2020), is further contributing to increased and cumulative pressures on the ocean, including overexploitation of living (and non-living) marine resources, chemical and physical pollution (including noise), the spread of invasive alien species, and physical destruction of habitats (UN, 2021). These combined pressures on the ocean ecosystem, namely on marine biodiversity, are impairing (and even threatening) the continued delivery of essential ecosystem services throughout the water column, all the way down to the deep sea and ocean floor (e.g., Levin and Le Bris, 2015), making the need to safeguard marine biodiversity ever more urgent (Johnson et al., 2019; Johnson et al., 2018a).

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea is the international agreement that establishes a legal framework for all marine and maritime activities. Conceived in the 1970s and signed in 1982, Part XII of UNCLOS contains special provisions for protection of the marine environment. However, our understanding of the complexity of the biosphere and the climate-ocean nexus, as well as humanity’s collective ocean literacy, has evolved. This has raised awareness of important governance gaps concerning the protection of marine biodiversity particularly in areas beyond national jurisdiction (e.g., Druel and Gjerde, 2014; Warner, 2014). In 2017 the UN General Assembly established an Intergovernmental Conference to negotiate an International Legally Binding Instrument under UNCLOS on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ) (General Assembly resolution 72/249). Negotiations are ongoing but the latest draft text of an agreement includes a short General objective in Article 2 stating that “The objective of this Agreement is to ensure the [long-term] conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction through effective implementation of the relevant provisions of the Convention and further international cooperation and coordination.” (UNGA, 2019).

Our contention is that this negotiation, and an expansion of the draft General objective specifically, is a golden opportunity to articulate a global ecosystem-based ocean vision, to guide any and all human activities in the ocean, as the common denominator for future policies, strategies, plans (including those resulting from marine spatial planning (MSP), programmes and projects, involving maritime activities. It would enhance their mutual coherence, framing the ‘new narrative for the ocean’ that the ocean is ‘too big to ignore’, called for by Lubchenko and Gaines (2019), and establishing the foundation for future ocean stewardship ensuring sustainable active management of the ocean ecosystem to promote multi-generational human wellbeing, as proposed by Rockström et al. (2021).

Proposed Tenets of an Ecosystem-Based Global Ocean Vision

A global ocean vision will be a picture of a desired future ocean (Lukic et al., 2018; Stuchtey et al., 2020): an image of what the marine environment should look like to be able to deliver to humanity the ecosystem services it relies on in a predefined but dilated timeline. Given that such a holistic and overarching future vision for the ocean must be capable of underpinning any and all relevant future global policies, plans and programmes, it must integrate key considerations such as global ecosystem scale, dilated time scale, a rapidly changing environment, globally agreed principles, and ‘strategicness’:

- global ecosystem scale (not always captured by framework conventions or lines on maps): this vision must assume an ocean basin scale as the only appropriate scale able to cover/integrate global ocean ecosystem level information (such as ecological connectivity (Harrison et al., 2018)) and all ocean uses and governance scales (jurisdictions), ranging from that of small local MPAs to national marine spaces, to regional seas and all the way through to ocean basins integrating areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ), including the high-seas and the subjacent seafloor, a.k.a., the Area. Global ecosystem scale is in fact the one at which phenomena such as major ocean migrations or the global ocean circulation that cross the whole range of existing jurisdictions and corresponding borders can be understood and sustainably managed;

- dilated time scales: time scales at stake also span a wide range, from seasonal or yearly licensing of fisheries quotas through multidecadal concessions for exploitation of non-living marine resources or the installation of fixed infrastructures, e.g., for renewable energies production (e.g., Ferreira & Andrade, 2021). For these reasons, a useful vision must be able to see beyond multiple decades (and correspondingly encompass a transgenerational horizon);

- rapidly changing environment/shifting baselines in the Anthropocene: a useful future global ocean vision must integrate current planetary ocean-climate and marine biodiversity trends (IPBES, 2019; IPCC, 2019b; Sweetman et al., 2017; Steneck and Pauly, 2019; Paulus, 2021) to be able to provide a realistic backdrop to the visioning process;

- globally agreed-principles: such as the so called ‘modern conservation principles’, which include the ecosystem approach and the precautionary approach, integrated and adaptive management, use of best available scientific information and application of best practices and technologies, stakeholder consultation, etc. (Gjerde et al., 2008)1. This is consistent with the call for a precautionary approach enshrined in many international instruments [e.g., ITLOS Advisory opinion in para. 131-135 (ITLOS, 2011) and UN Fish Stocks Agreement Art. 6 (UNGA, 1995)];

- ‘strategicness’: refers to a holistic, anticipatory, prospective, all-encompassing integrative approach/framework to address the planning and management of these global environmental challenges, and to assess the effectiveness of the measures adopted (Stoeglehner, 2020). Such a strategic approach must be capable of guiding all vested interests towards a sustainable ocean economy; setting a general direction towards robust ocean health; building and promoting a culture of sustainability; serving both the short- and the long-term interests which will likely cover decadal time spans; and achieving delivery of lasting wellbeing.

Discussion - Building the Ecosystem-Based Global Ocean Vision Under BBNJ - A Key Role for SEA

Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA), “a process to facilitate strategic decisions toward sustainability” (Noble and Nwanekezie, 2017), is an approach for future visions development and evaluation, and has been considered the best option for the delivery of lasting wellbeing, building a culture of sustainability, and serving the long and the short-term interest (Gibson et al., 2016). It has been mooted as a “modern conservation tool”, together with other instruments, alongside MSP or networks of representative MPAs, that apply to human activities or to their effects in the ocean (Gjerde et al., 2008). We argue below how an SEA approach could inform the BBNJ Agreement, specifically its General objective text.

Potential of SEA in BBNJ: From EIA-Based to Strategy-Based

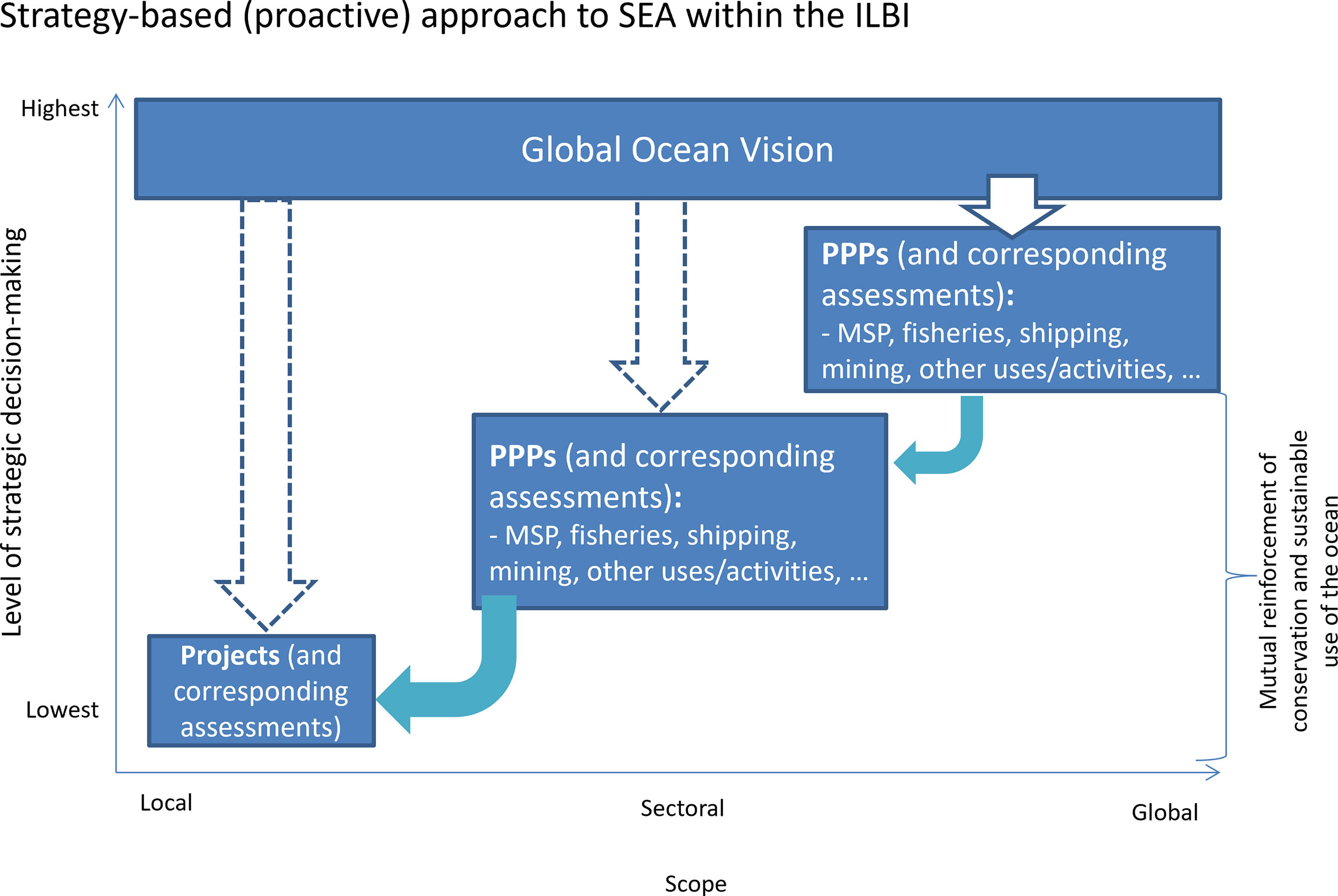

SEA is still predominantly applied as an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA)-based approach to the identification and evaluation of the environmental consequences of policies, plans or programmes2 (PPP), differing from the traditional EIA of projects (see Glasson and Therivel, 2019)3 mainly in terms of its scope (Noble & Nwanekezie, 2017). Under this understanding SEA is commonly used as a post-evaluation procedure whose main aim is to ensure the formal consistency of the high-level management instrument it applies to with environmental requirements (ibid.) (Figure 1). As such, although it may contribute to “greening” such instruments (CEC, 2009, 10), it is often seen as a ‘necessary evil’ to be hurdled to enable economic endeavours or “a simple procedural box-ticking requirement” (EC, 2017, 10). Even where efforts are being made to introduce SEA at the earliest stages of planning processes (see European MSP Platform, 2021; UNESCO-IOC/European Commission, 2021), its role is still limited to addressing “the environmental impacts of regional planning and sectoral plans as well as planning alternatives” (ibid., 113). In this ‘EIA-based’ application of SEA, as a process used to review predefined proposals after key strategic decisions have been taken, SEA has value but its contribution to the decision-making process is effectively limited and relevant opportunities are lost (Gibson et al., 2016). This EIA-based SEA is the model adopted by the Convention on Biological Diversity [see COP 6 Decision VI/7 (CBD, 2002)] and is the sense in which it is included in the current draft of the International Legally Binding Instrument (ILBI) on BBNJ [see articles 28 and 42 (UNGA, 2019)].

Figure 1 Traditional, EIA-based (reactive) approach to SEA, where SEA is at best a greening mechanism of a corresponding high-level management instrument. indicates potential connections.

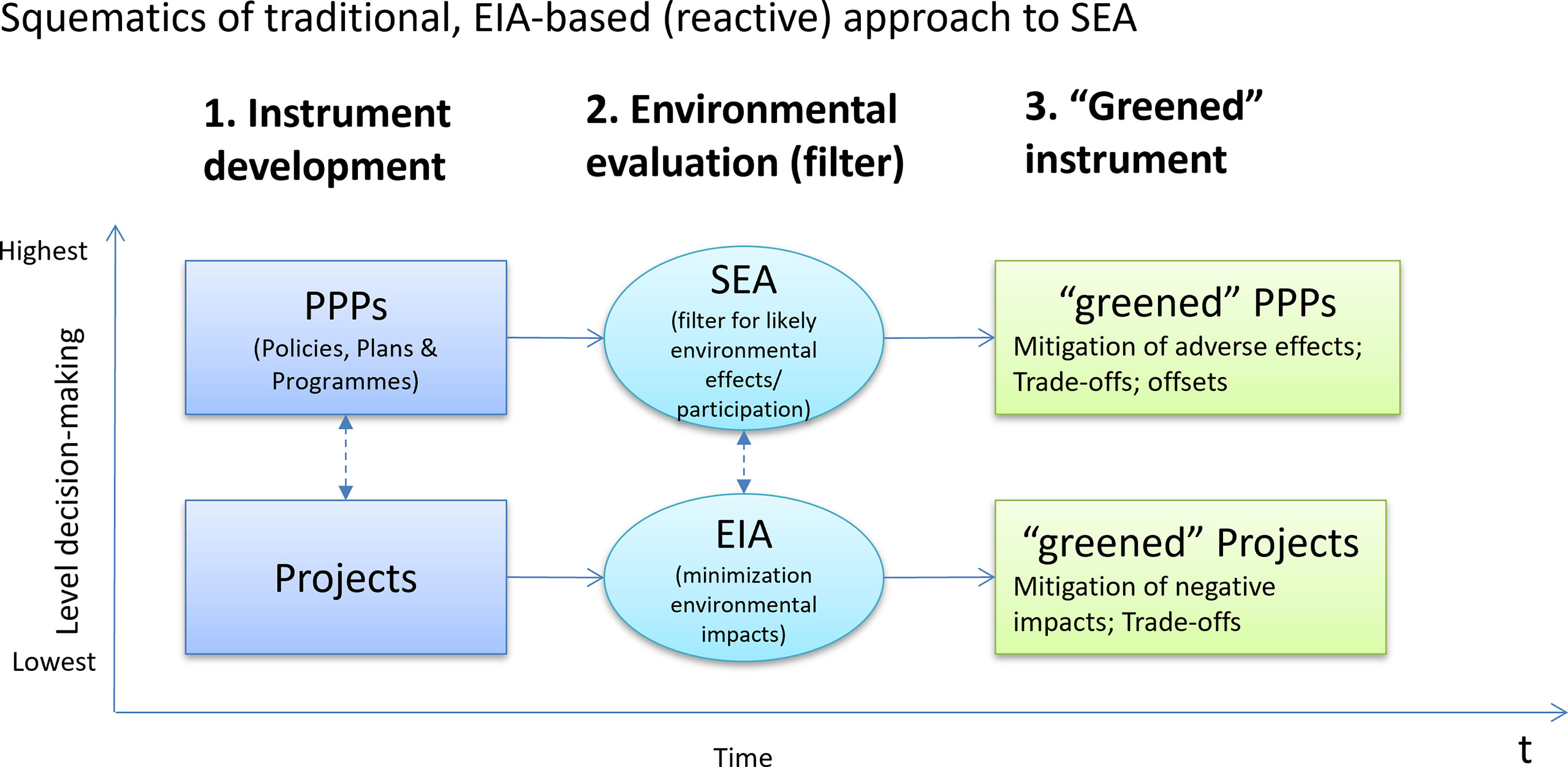

Conversely, adoption of SEA as a strategy-based4 or proactive approach opens up for new opportunities, able to reconcile multiple ambitions and perspectives. With such an approach SEA becomes a process for driving the decision-making process and institutional change. Use of strategy-based SEA has been advocated in the context of the Convention for Biodiversity Sustainable Ocean Initiative (CBD/SOI, n.d.) and within the BBNJ agreement/negotiations, to promote cooperation and conservation (e.g., Doelle & Sander, 2020; Hassanali and Mahon, 2022; WWF, 2019; Hills, 2020). WWF (2019) suggested that States should be required to conduct a ‘collective’ SEA, which would act as a warrant of environmental oversight and as an “exercise in ‘enhanced cooperation’”, and Hills (2020, p. 27), reporting on the results of a 2020 EC workshop on EIAs and SEAs in ABNJ, noted ‘the need to harmonise processes to create a cooperative and integrated approach’. Doelle & Sander (2020) listed the basic building blocks of next generation environmental assessments (including SEA) that need to be in place under Hassanali and Mahon (2022) detailed the components of a proactive process for conservation of BBNJ with an SEA track informing subsequent region-specific policies and plans (including MSP).

An obligation for States to undertake SEA of “plans and programmes relating to activities” is currently given a place holder (Article 28) in the revised draft text of the BBNJ Implementing Agreement (A/CONF.232/2020/3) (UN, 2020). This was considered at the fourth substantive session (IGC4) of the Intergovernmental Conference held from 7-18 March 2022. During IGC4 there was no consensus on SEA with mixed opinions regarding its application and some States continuing to promote voluntary application. However, this interpretation relates to instruments meeting set criteria (yet to be agreed), albeit supporting the use of SEA to address cumulative pressures, instead of addressing/pursuing an overarching holistic future vision.

Employing a Strategy-Based SEA to Reach a Global Ocean Vision Within BBNJ

We specifically argue that a strategy-based SEA could inform the BBNJ Agreement General objective text, framing the development of an ecosystem-based global ocean vision that can guide and support the development of any subsequent (related) instruments and of their corresponding assessments (Figure 2). Expanding text in Part I General Provisions of the draft BBNJ Agreement – for example in Article 2 General Objective, or in a new Article 2 bis, or strengthening Article 5 (General principles and approaches) – could, in succinct terms, incorporate a vision resulting from a strategy-based SEA approach. Contributions to a virtual dialogue convened from 29-31 March 2022 (i.e., shortly after IGC4) by the STRONG High Seas Project5 underlined the benefits of a common goal or purpose; an overarching set of principles, and more explicit State obligations to cooperate.

Building, agreeing and ratifying such an all-encompassing global ocean vision is a complex task, with multiple and interlinking layers. To use a theatrical analogy, some key elements need to be considered:

- Selling the concept: understanding and incorporating the tenets described above as the backdrop (scenario) for developing the vision;

- Writing the script: a clear, simple, synthetic, consensual message that can be used to guide action (the vision);

- Casting: carefully identifying the full range of actors that need to be won over and involved, across all geographic scales and sectors of society. This translates into a major challenge in view of the diversity of interests and of stakeholders at play: from states, to regional bodies and to international organisations; from individuals to NGOs, business companies, investors;

- Setting the scenario: ensuring incorporation of the strongly stated pre-condition of the BBNJ negotiation that it should ‘not undermine existing relevant legal instruments and frameworks and relevant global, regional and sectoral bodies’ (UN, 2019) (see below);

- Connecting with the audience (society and its various elements) and its needs: well-being, health, prosperity,… and scope, from humankind (for the High Seas or the Area) to the individual (e.g., a fisherman).

Various methods could be used to operationalise this proposal. A conceptual flexible framework for SEA has been laid out by Partidário (2012), with a set of key structural elements to be combined in the best adapted way, including the identification of internal and external driving forces, either drivers of change or inhibitors; establishing priority/determinant environmental and sustainability issues; identifying government and non-governmental organizations and institutions; and establishing a network of relevant stakeholders. Base information to underpin such an SEA process is now increasingly available as a result of comprehensive, basin scale research (Cf. Supplementary Material: North Atlantic case study). Also, an emerging scenario building methodological framework that could be employed to establish this type of forward-looking vision is the Nature Futures Framework Approach (NFF), which shifts the traditional scenario building focus from exploring impacts of society on nature, to nature-centred visions and pathways (Pereira et al., 2020).

A major role should be attributed to participatory approaches in strategic contexts to contribute to the new consistent narrative underlying construction of the global ocean vision. Abundant guidance is available on participatory processes and stakeholder involvement6. In the context of on-going negotiations, this could be coordinated by any new BBNJ Scientific and Technical Body perhaps as an Annex to the Agreement.

Inspiration could be drawn from The Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty7. The Protocol is a significant, high ambition and long-standing binding instrument8. Article 3 of the Protocol covers Environmental Principles relating to human activities. In effect, this Article takes an SEA stance: prioritizing protection, placing limitations on activities that could cause adverse impacts, insisting on informed decision-making and risk assessment, and establishing monitoring obligations. Articles 4, 5 and 6 cover context (i.e., relationship with other components of the Antarctic Treaty System), consistency with other components (of the Antarctic Treaty System) and Co-operation.

Opportunity and Timeliness

IGC4 did not conclude negotiations, with States requesting a fifth negotiating session. Following IGC4, Article 2 of the draft BBNJ Agreement remains unchanged although many delegations called for streamlining text on international cooperation and Treaty. Recognition of the ‘not undermining principle’9. This is further reflected in language pertaining to international cooperation and coordination of Area-Based Management Tools stressing the need to recognise their coherence and complementarity. Several commentators have also reflected on implications of this principle for institutional arrangements of the new Agreement (e.g., Clark, 2020; Berry, 2021) and global cooperation (Friedman, 2019). Considerable discussion was devoted to cross-cutting issues such as the remit of the Conference of the Parties (COP) and subsidiary bodies that the COP could establish.

An ‘environment for well-being’ approach (Ntona and Morgera, 2018) enshrined in a globally shared normative framework would reflect high-level commitments made in a range of international policy processes (Pretlove and Blasiak, 2018). Such an approach would explicitly align a BBNJ instrument with the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda and SDG 14 (UNGA, 2015) while maintaining consistency with the Convention on Biological Diversity (Article 5) and the United Nations Fish Stocks Agreement and the mandate of Regional Fisheries Management Organizations.

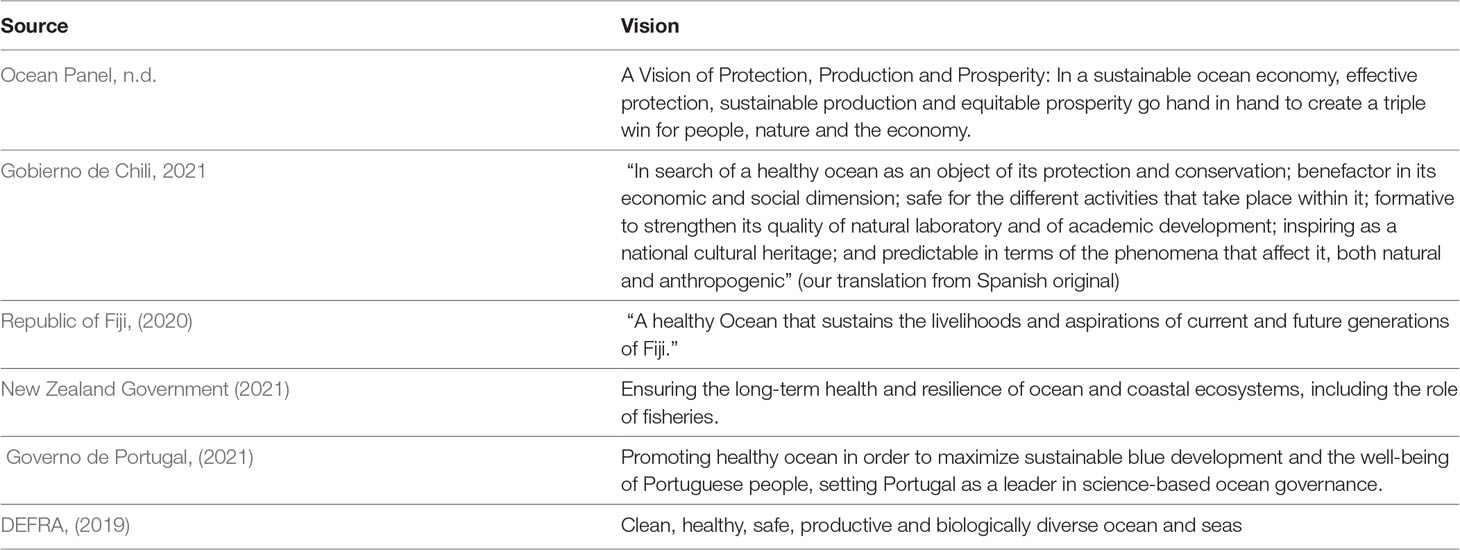

Our proposal has strong synergy with the ‘New Action Agenda’ of the Ocean Panel that seeks a vision for protection, production and prosperity in national waters10, and complements national visions, such as those published by Chili, Fiji, New Zealand, Portugal and the UK (Table 1) (Gobierno de Chili, 2021; DEFRA, 2019; Republic of Fiji, 2020; Governo de Portugal, 2021; New Zealand Government, 2021). The One Ocean Summit (9-11 February 2022, in Brest, France) highlighted multiple non-coherent talks taking place in different sectoral initiatives and called for simpler governance to involve civil society and preserve global commons, a notion that has synergy with an overall global ocean vision.

A global ocean vision as envisaged here is timely as 2022 marks the 40th anniversary of UNCLOS, the legal framework that, to date, has successfully provided the foundation for cooperation and consistency in terms of global multilateralism for all marine and maritime activities11. A fifth session of the IGC of BBNJ is tentatively scheduled for August 2022 at which it is hoped that the implementing agreement will be concluded, so this critical negotiation can provide a final chance to implement the suggestion we are promoting here.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

DEJ is funded by the Global Ocean Biodiversity Initiative (GOBI). GOBI is supported by the International Climate Initiative (IKI). The German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU) supports this initiative on the basis of a decision adopted by the German Bundestag.

Conflict of Interest

Author DeJ is employed by the company Seascape Consultants, Ltd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling Editor JMR declared a past collaboration with the author DEJ.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

With grateful thanks to Phil Weaver for his contribution on the International Seabed Authority’s Regional Environmental Management Plan for the Mid Atlantic Ridge in the Atlantic case study (see Supplementary Material). The authors are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments which prompted a radical revision of the manuscript and greatly improved its coherence.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2022.878077/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

- ^ Included in Article 5 of the draft BBNJ Agreement.

- ^ In EU member-states, under Directive 2001/42/EC, SEA only applies to plans and programmes.

- ^ ‘EIA is a process, a systematic process that examines the environmental consequences of development actions, in advance.’ (Glasson and Therivel, 2019).

- ^ For an in-depth discussion of the gradient from less to more strategic aspects that SEA can assume, see Noble and Nwanekezie, 2017.

- ^ https://www.prog-ocean.org/our-work/strong-high-seas/.

- ^ e.g., CBD SOI training modules (https://www.cbd.int/soi/training/soi-training-modules).

- ^ https://www.ats.aq/e/protocol.html.

- ^ Until 2048 the Protocol can only be modified by unanimous agreement of all Consultative Parties to the Antarctic Treatyprinciple’.

- ^ The ‘not undermining’ principle is a key issue and relates to achieving a harmonious coexistence between the BBNJ Agreement and existing instruments. Article 4, para 3 (as currently drafted) affirms that the ILBI: “…does not undermine existing relevant legal instruments and frameworks and relevant global, regional and sectoral bodies”.

- ^ The High-Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy (The Ocean Panel), co-chaired by Norway and Palau, have set out a vision for how to build a sustainable ocean economy (https://www.oceanpanel.org/).

- ^ This stance is consistent with Arvid Pardo’s inspiration in the 1960s to look at the ocean’s problems as a whole (UNGA, 1967; UN, 1999), that represented the underlying rationale of UNCLOS, whose preamble acknowledges that ‘the problems of ocean space are closely interrelated and need to be considered as a whole’.

References

Berry D. S. (2021). Unity or Fragmentation in the Deep Blue: Choices in Institutional Design for Marine Biological Diversity in ABNJ. Front. Mar. Sci. 8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.761552

Boschen-Rose R. E., Ferreira M. A., Johnson D. E., Gianni M. (2020). “Engaging With Industry to Spur Blue Growth,” in Proceedings From the International Coastal Symposium (ICS) 2020 (Seville, Spain. Eds. Malvárez G., Navas F. (Coconut Creek (Florida: Journal of Coastal Research). ISSN 0749-0208

CBD/SOI Strategic Environmental Assessment: A Strategic Thinking Framework for Achieving Sustainable Development. Available at: https://www.cbd.int/marine/soi/soi-training-modules/SOI-SEA_Training-Guide-en.pdf.

CBD (2002) COP6 Decision VI/7. Identification, Monitoring, Indicators and Assessments. Available at: https://www.cbd.int/decision/cop/?id=7181.

CEC (2009). Final Report From the Commission to the Council, the European Parliament, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on the Application and Effectiveness of the Directive on Strategic Environmental Assessment, Directive 2001/42/EC). COM(2009) 469.

Clark N. A. (2020). Institutional Arrangements for the New BBNJ Agreement: Moving Beyond Global, Regional and Hybrid. Mar. Policy 122, 104143. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104143

DEFRA (2019) Marine Strategy Part One: UK Updated Assessment and Good Environmental Status. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/921262/marine-strategy-part1-october19.pdf.

Doelle M., Sander G. (2020). Next Generation Environmental Assessment in the Emerging High Seas Regime? An Evaluation of the State of the Negotiations. Int. J. Mar. Coast. Law 35, 498–532. doi: 10.1163/15718085-BJA10022

Druel E., Gjerde K. (2014). Sustaining Marine Life Beyond Boundaries: Options for an Implementing Agreement for Marine Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. Mar. Policy 49, 90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2013.11.023

EC (2017). COM, (2017) 234 Final REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE COUNCIL AND THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT Under Article 12(3) of Directive 2001/42/EC on the Assessment of the Effects of Certain Plans and Programmes on the Environment. Brussels: European Commission.

European MSP Platform (2021) Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA). Available at: https://www.msp-platform.eu/faq/strategic-environmental-assessment-sea.

Ferreira M. A., Andrade F. (2021). “A Protecção do Mar E O Ordenamento do Espaço Marítimo,” in Ministério do Mar 2021. Proteger O Mar. IPMA, I.P, 200 pp. Available at: https://www.ipma.pt/resources.www/docs/publicacoes.site/Proteger-O-Mar-Eletronico.pdf, ISBN: ISBN: 978-972-9083-24-2. Lisboa, IPMA - Instituto Português do Mar e da Atmosfera, I.P.

Friedman A. (2019). Beyond “Not Undermining”: Possibilities for Global Cooperation to Improve Environmental Protection in Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 76 (2), 452–456. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsy192

Gibson R. B., Doelle M., Sinclair A. J. (2016). Fulfilling the Promise: Basic Components of Next Generation Environmental Assessment. J. Environ. Law Pract. 29, 251–276.

Gjerde K. M., et al. (2008). Options for Addressing Regulatory and Governance Gaps in the International Regime for the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biodiversity in Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (IUCN, Gland, Switzerland), + 20.

Glasson J., Therivel R. (2019). Introduction to Environmental Impact Assessment (5th Edition) (Routledge), 394 pages. Oxon and New York

Gobierno de Chili (2021) Política Oceánica Nacional De Chile. Available https://www.acanav.cl/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/poli:tica_ocea:nica_nacional_de_chile_ok-1.pdf

Governo de Portugal (2021) National Ocean Strategy 2021-2030. Available at: https://www.dgpm.mm.gov.pt/_files/ugd/eb00d2_066d6252d6f84342aa34d8f9f301ae32.pdf.

Harrison A.-L., Costa D.P., Winship A.J., Benson S.R., Bograd S.J., Antolos M., et al. (2018). The Political Biogeography of Migratory Marine Predators. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 1571–1578. doi: 10.1038/s41559-018-0646-8

Hassanali K., Mahon R. (2022). Encouraging Proactive Governance of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction Through Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA). Mar. Policy 136, 104932 doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104932

Hills J. M. (2020). Report of the Workshop “Environmental Impact Assessments and Strategic Environmental Assessments in Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction” (Brussels, Belgium: European Commission). 28-29 January 2020.

IOC-UNESCO (2022). Multiple Ocean Stressors: A Scientific Summary for Policy Makers. Ed. Boyd P. W. (Paris, UNESCO: IOC Information Series, 1404), 20 pp. doi: 10.25607/OBP-1724

IPBES (2019). Summary for Policymakers of the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Eds. Díaz S., Settele J., E. S. Brondízio E. S., Ngo H. T., Guèze M., Agard J., Arneth A., Balvanera P., Brauman K. A., Butchart S. H. M., Chan K. M. A., Garibaldi L. A., Ichii K., Liu J., Subramanian S. M., Midgley G. F., Miloslavich P., Molnár Z., Obura D., Pfaff A., Polasky S., Purvis A., Razzaque J., Reyers B., Chowdhury R.R., Shin Y. J., Visseren-Hamakers I. J., Willis K. J., Zayas C. N., 56 pages, (Bonn, Germany:IPBES secretariat).

IPCC (2019a). Annex I: Glossary [Weyer, N.M. (ed.)]. In: IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate [Pörtner H.-O., Roberts D.C., Masson-Delmotte V., Zhai P., Tignor M., Poloczanska E., Mintenbeck K., Alegría A., Nicolai M., Okem A., Petzold J., Rama B., Weyer N.M.(eds.)] Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY,USA, pp. 677–702. doi: 10.1017/9781009157964.010

IPCC (2019b). Summary for Policymakers. In: IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate[ Pörtner H.-O., Roberts D.C., Masson-Delmotte V., Zhai P., Tignor M., Poloczanska E., Mintenbeck K., Alegría A., Nicolai M., Okem A., Petzold J., Rama B., Weyer N.M.(eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK andNew York, NY, USA, pp. 3–35. doi: 10.1017/9781009157964.001

ITLOS (2011). Responsibilities and Obligations of States Sponsoring Persons and Entities With Respect to Activities in the Area, Advisory Opinion, 1 February 2011. Hamburg, Germany: International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea. p.10.

Johnson D. E., Barrio-Frojan C., Bax N., Dunstan P., Woolley S., Halpin P., et al. (2018a). The Global Ocean Biodiversity Initiative: Promoting Scientific Support for Global Ocean Governance. Aquat. Conserv. Special Issue. 29(S2): 162–169. doi: 10.1002/aqc.3024

Johnson D., Ferreira M. A., Kenchington E. (2019). Climate Change is Likely to Severely Limit the Effectiveness of Deep-Sea ABMTs in the North Atlantic. Mar. Policy 87, 111/122. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2017.09.034

Levin L. A., Le Bris N. (2015). Deep Oceans Under Climate Change. Science 350, 766–768. doi: 10.1126/science.aad0126

Lubchenko J., Gaines S. (2019). A New Narrative for the Ocean. Science 364, 6444. doi: 10.1126/science.aay2241

Lukic I., Schultz-Zehden A., de Grunt L. S. (2018). “Handbook for Developing Visions in MSP,” in Technical Study Under the Assistance Mechanism for the Implementation of Maritime Spatial Planning. Brussels: European Commission.

New Zealand Government (2021) Government Adopts Oceans Vision. 26 June 2021. Available at: https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/government-adopts-oceans-vision.

Noble B., Nwanekezie K. (2017). Conceptualizing Strategic Environmental Assessment: Principles, Approaches and Research Directions. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 61: 165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2016.03.005

Ntona M., Morgera E. (2018). Connecting SDG14 With Other SDGs Through Marine Spatial Planning. Mar. Policy 93, 214–222. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2017.06.020

Ocean Panel, n.d. A Vision of Protection, Production and Prosperity. Available at https://www.oceanpanel.org/. Accessed 22.06.2022

Pacific Regional Ocean Policies (2017) Our Sea of Islands Our Livelihoods Our Oceania. Available at: http://www.forumsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Overview-of-Pacific-Islands-Forum-Ocean-Policies-2017.pdf.

Partidário M. R. (2012). Strategic Environmental Assessment Better Practice Guide - Methodological Guidance for Strategic Thinking in SEA (Lisboa: Agência Portuguesa do Ambiente e Redes Energéticas Nacionais).

Paulus E. (2021). Shedding Light on Deep-Sea Biodiversity—A Highly Vulnerable Habitat in the Face of Anthropogenic Change. Front. Mar. Sci. 8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.667048

Pretlove B., Blasiak R. (2018) Mapping Ocean Governance and Regulation. Working Paper for Consultation for UN Global Compact Action Platform for Sustainable Ocean Business. Available at: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/library/5710.

Pereira L.M., Davies K.K., den Belder E., Ferrier S., Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen S., Kim H., et al. 2020. Developing Multiscale and Integrative Nature–Peoplescenarios Using the Nature Futures Framework. People Nat. 2, 1172–1195. doi: 10.1002/pan3.10146.

Republic of Fiji (2020) National Ocean Policy. To Secure and Sustainably Manage All of Fiji’s Ocean and Marine Resources. Available at: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1w7skJdv7PvZ0cUYfZxKSanMLQDEA3Sip/view.

Rockström J., Beringer T., Griscom B., Mascia M. B., Folke C., Creutzig F. (2021). Opinion: We Need Biosphere Stewardship That Protects Carbon Sinks and Builds Resilience. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Sep 2021 118 (38), e2115218118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2115218118

Rockström J., Steffen W., Noone K., Persson A., Chapin F. S., Lambin E. F., et al. (2009). A Safe Operating Space for Humanity. Nature 461, 472–475. doi: 10.1038/461472a

SCBD (2020). Global Biodiversity Outlook 5 (Montreal : Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity). Available at: www.cbd.int/GBO5.

Steffen W., Broadgate W., Deutsch L., Gaffney O., Ludwig C. (2015). The Trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration. Anthropocene Rev. 2 (1), 81–98. doi: 10.1177/2053019614564785

Steneck R., Pauly D. (2019). Fishing Through the Anthropocene. Curr. Biol. 29, R942–R995. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.07.081

Stoeglehner G. (2020). Strategicness – the Core Issue of Environmental Planning and Assessment of the 21st Century. Impact Assess. Project Appraisal 38 (2), 141–145. doi: 10.1080/14615517.2019.1678969

Stuchtey M. R., Vincent A., Merkl A., Bucher M., Haugan P.M., Lubchenco J., et al. (2020). Ocean Solutions That Benefit People, Nature and the Economy (Washington, DC: World Resources Institute). Available at: www.oceanpanel.org/ocean-solutions.

Sweetman A. K., Thurber A. R., Smith C. R., Levin L. A., Mora C., Wei C.-L., et al, (2017). Major Impacts of Climate Change on Deep-Sea Benthic Ecosystems. Elementa: Sci. Anthropocene(2017)5, 4. doi: 10.1525/elementia.203

UN (1982) United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. Available at: https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf.

UN (1999). DR. ARVID PARDO, ‘Father OF LAW OF SEA Conference’DIES AT 85, IN HOUSTON (TEXAS: Press Release SEA/1619). Available at: https://www.un.org/press/en/1999/19990716.SEA1619.html.

UN (2019) Revised Draft Text of an Agreement Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction. (New York:United Nations,. Available at: https://www.un.org/bbnj/sites/www.un.org.bbnj/files/revised_draft_text_a.conf_.232.2020.11_advance_unedited_version.pdf.

UN (2020). Textual Proposals Submitted by Delegations by 20 February 2020, for Consideration at the Fourth Session of the Intergovernmental Conference on an International Legally Binding Instrument Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (the Conference), in Response to the Invitation by the President of the Conference in Her Note of 18 November 2019, (A/CONF.232/2020/3).

UNESCO-IOC/European Commission (2021). MSPglobal International Guide on Marine/Maritime Spatial Planning (Paris: UNESCO). IOC Manuals and Guides no.89.

UNGA (1967). Official Records of the United Nations General Assembly Twenty-Second Meeting. First Committee 1515th Meeting, 1 November 1967 (New York : United Nations General Assembly). Available at: https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/pardo_ga1967.pdf.

UNGA (1995). Agreement for the Implementation of the Provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 10 December 1982 Relating to the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks, United Nations, New York A/CONF.164/37.

UNGA (2015). 70/1. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015, A/RES/70/1.

UNGA (2019) Revised Draft Text of an Agreement Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction. Available at: https://undocs.org/en/a/conf.232/2020/3.

UNGA (2021). Singapore Draft Decision: Intergovernmental Conference on an International Legally Binding Instrument Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction, A/75/L.96. 9 June 2021.

United Nations Environment Programme (2021). Making Peace With Nature: A Scientific Blueprint to Tackle the Climate, Biodiversity and Pollution Emergencies. Nairobi: United Nations Rnvironment Programme

Warner R. M. (2014). Conserving Marine Biodiversity in Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction: Co-Evolution and Interaction With the Law of the Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 1 doi: 10.3389/fmars.2014.00006

WWF (2019) Strategic Environmental Assessments in the Context of the BBNJ ILBI. A Webinar for Delegates Produced by WWF, With the Collaboration of the UK Government, the Government of Sweden, the University of Waterloo and the University of Lisbon. July 2019. Available at: https://wwf.zoom.us/recording/play/m6w1wFMND5TPHjc3HNiYQ-KWfvUp9omR3mssYJdzRZzmnaK7nLqy1JGzk93lkExk?continueMode=true.

Keywords: ecosystem-based approach, global ocean vision, strategic environmental assessment, UNCLOS, BBNJ Agreement

Citation: Ferreira MA, Johnson DE and Andrade F (2022) The Need for a Global Ocean Vision Within Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction: A Key Role for Strategic Environmental Assessment. Front. Mar. Sci. 9:878077. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.878077

Received: 17 February 2022; Accepted: 09 June 2022;

Published: 15 July 2022.

Edited by:

J. Murray Roberts, University of Edinburgh, United KingdomReviewed by:

Glen Wright, Institut du Développement Durable et des Relations Internationales, FranceCopyright © 2022 Ferreira, Johnson and Andrade. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maria Adelaide Ferreira, bWFmZXJyZWlyYUBmYy51bC5wdA==

Maria Adelaide Ferreira

Maria Adelaide Ferreira David E. Johnson

David E. Johnson Francisco Andrade1,3

Francisco Andrade1,3