- 1Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD, Australia

- 2WorldFish, Penang, Malaysia

- 3Wildlife Conservation Society, New York, NY, United States

- 4Lancaster Environment Center, Lancaster University, Lancaster, United Kingdom

- 5Department of Environmental Studies, Ashoka University, Sonipat, Harayana, India

- 6Department of Natural Resources and the Environment, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, United States

- 7Wildlife Conservation Society, Karnataka, India

- 8Talanoa Consulting, Suva, Fiji

- 9Interdisciplinary Centre for Conservation Science, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

Human rights matter for marine conservation because people and nature are inextricably linked. A thriving planet cannot be one that contains widespread human suffering or stifles human potential; and a thriving humanity cannot exist on a dying planet. While the field of marine conservation is increasingly considering human well-being, it retains a legacy in some places of protectionism, colonialism, and fortress conservation. Here, we i) provide an overview of human rights principles and how they relate to marine conservation, ii) document cases where tensions have occurred between marine conservation goals and human rights, iii) review the legal and ethical obligations, and practical benefits, for marine conservation to support human rights, and iv) provide practical guidance on integrating human rights principles into marine conservation. We argue that adopting a human rights-based approach to marine conservation, that is integrating equity as a rights-based condition rather than a charitable principle, will not only help meet legal and ethical obligations to respect, protect, and fulfil human rights, but will also result in greater and more enduring conservation impact.

1 Background

Under what circumstances, if any, is it acceptable to implement marine protected areas in Indigenous marine territories without consultation or consent? When is it appropriate to stop local fishers from harvesting food within marine protected areas? Do these circumstances change if fishers face extreme food insecurity or malnutrition? Do rules differ for migrant fishers without long-term connections to place? Do past rights abuses need to be addressed by conservation programs acting today? And what methods are considered appropriate to enforce environmental restrictions? Shooting, public flogging, or vessel rammings? Fines on those who are already food insecure? These actions are all reported to have been carried out in recent years in the name of marine conservation (e.g., Sand, 2012; Cross, 2016; Hill, 2017; Kamat, 2018; Sowman and Sunde, 2018; Crosman et al., 2022; Talukdar et al., 2022). But how much are these issues a question of legal obligation, moral discretion, or practical decision-making (Newing and Perram, 2019)?

The field of marine conservation, and the conservation sector more broadly, retains a legacy in some places of protectionism, colonialism, and fortress conservation (e.g., Chapin, 2004; Springer et al., 2011; Singleton et al., 2017; Tauli-Corpuz et al., 2020). These practices often incur great social costs on Indigenous Peoples and other local rights holders by violating human rights to life, health, water, food, and adequate standard of living, non-discrimination, and cultural rights. Furthermore, opportunities to participate in decision-making and management is frequently fraught with difficulties and compensation is often not commensurate with the harm caused. These conflicts between communities and governments or implementing partners of fortress conservation continue to surface, as do reports of arbitrary detention, illegal searches, intimidation and coercion, and violence.

Yet conservation policy and practice is increasingly turning a corner in its understanding of justice and human well-being (e.g., Tan, 2021; Bennett, 2022; Ruano-Chamorro et al., 2022). Many within the conservation movement view social and environmental justice issues as inextricably intertwined – a thriving planet cannot be one that contains widespread human suffering or stifles human potential; and a thriving human population cannot exist on a dying planet (Forum For the Future, 2022). Effective and equitable conservation principles are now embedded within the Convention for Biological Diversity (CBD), such as with the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework acknowledging “a human rights-based approach respecting, protecting and fulfilling rights, and being mindful of diverse world views, values and knowledge systems, including different conceptualizations of nature and people’s relationship with it” (CBD, 2022). Community-based and co-management principles are now considered priorities by many leading conservation organizations. Yet despite best intentions, as 196 countries around the world continue to negotiate the successor to the Strategic Plan – the CBD Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework – that will guide conservation policy over the next 30 years, there remains limited understanding of how effective and equitable conservation unfolds in practice.

Human rights recognize the inherent value of each person, regardless of background, geography, appearance, or beliefs. They are based on principles of dignity, equality, and mutual respect, shared across cultures, religions, and philosophies (U.N., 1948). Further, rights are just that – rights – and as such international law requires that they should be respected, protected, and fulfilled by governments, who are the primary ‘duty-bearers’ (Newing and Perram, 2019). Yet other institutions, including conservation organizations, also have a responsibility to respect rights (i.e., ‘do no harm’), meaning a responsibility to avoid causing rights violations, and avoid contributing to human rights violations by others (Newing and Perram, 2019). While calls to adopt human rights principles are growing in the conservation sector, most center on terrestrial issues (e.g. Tauli-Corpuz et al., 2020), with far fewer focusing on how these concepts relate to marine conservation issues and the blue economy.

In this essay, we argue that adopting human rights principles is key for progressing effective and equitable marine conservation outcomes, and that there are strong legal, ethical, and practical reasons for marine conservation practitioners to support human rights. While we primarily use the intersection between the small-scale fisheries (SSF) sector and international conservation NGOs (hereafter, NGOs) (Box 1) to explore these topics, we also acknowledge the breadth of ways in which marine conservation and human rights can intersect. This essay is divided into five components:

● First, we provide an overview of human rights and a human rights-based approach (HRBA) and how they relate to marine conservation (i.e., what are human rights and an HRBA, who is responsible for supporting human rights, and how is it relevant to marine conservation)?.

● Second, drawing examples from SSF, we present a series of case studies that document tensions between marine conservation and human rights, and key social impacts that have accrued when human rights are not sufficiently supported (i.e., exposing impacts of not supporting human rights).

● Third, we outline legal and ethical obligations to respect human rights law as the bottom line, regardless of whether it leads to improved biodiversity conservation outcomes, while considering the rights of future generations (i.e., why we must respect human rights).

● Fourth, we review the evidence that supporting the rights of people, including by acknowledging the leading role of many Indigenous Peoples in conservation, is an effective tool for positive and enduring marine conservation impact (i.e., practical benefits).

● Lastly, we provide some practical guidance on incorporating an HRBA into marine conservation, including steps and tools that can be used to operationalize marine conservation programs that are interested in adopting this approach (i.e., how to do it).

Box 1 International conservation NGOs and small-scale fisheries.

One lens by which to investigate relationships between human rights and marine conservation is through interactions between the small-scale fisheries (SSF) sector and international conservation NGOs. Arguably, the largest group of ocean users and those most vulnerable to human rights violations by marine conservation actions, in both scale and degree, are small-scale fishers (Ratner et al., 2014; Cohen et al., 2019) (Figure 1). This sector typically includes self-employed fishers involved in locally-based artisanal fishing and encompassing all activities along the value chain – pre-harvest, harvest, and post-harvest (FAO, 2015). These women and men account for 90% of the world’s fishers (approximately 492 million people are dependent at least partially on SSF for their livelihoods), 40% of global catch (FAO, 2022), and 5.8 million small-scale fishers earn less than USD 1 per day (FAO, 2022). They tend to be firmly rooted in local communities, traditions, and values, and as such provide employment and food and nutrition security to local economies (FAO, 2015). Yet despite their potential as critical allies for ocean conservation, small-scale fishers have been consistently sidelined from dialogue between international environmental and economic actors with stronger political and economic influence (e.g., conservation, energy, mining, and tourism). For example, fishers are often excluded from access to other employment opportunities, from equitable access to land, and have weak political representation (Allison et al., 2012). Their dependence on natural production systems also introduces substantial uncertainty and risk in livelihoods and exposes them to environmental or socio-economic shocks including failures in policy or governance. All of this makes it difficult for small-scale fishers to have their voices heard, defend their rights, and secure the sustainable use of the fisheries on which they depend (FAO, 2015).

International conservation NGOs are now a key force in the global marine conservation movement, with budgets in the billions of dollars, and existing relationships with national governments, multinational corporations, and a voice in the international policy arena (Chapin, 2004; Singleton et al., 2017; Larsen and Brockington, 2018). Accordingly, the extent to which NGOs view people as ‘allies’ versus ‘opportunity costs’ has substantial bearing on how people and nature intersect. Increasingly, international conservation NGOs work in (and increasingly with) communities in developing countries, and can be in a strong position of local influence and power, particularly when the state has weak governance or is poorly resourced (Singleton et al., 2017). While the primary mandate of most conservation NGOs is to preserve values of nature (i.e., biodiversity and wilderness) (Allison et al., 2020), they are also increasingly held to account to do so in a way that respects and promotes international human rights standards. This includes through supportive processes, such as through the Conservation Initiative on Human Rights (CIHR) (Springer et al., 2011), as well as guiding policy documents, such as the Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries (FAO, 2015). While larger conservation NGOs nominally support the CIHR and SSF Guidelines, integrating human rights into overarching policies has been slow, and many policies are yet to be institutionalized (Singleton et al., 2017). Regardless, international NGOs have great potential to act as a conduit for communication between people made vulnerable and other parties, although to do so in many instances they are required to rebuild the trust of communities and demonstrate genuine commitment to people-as-well-as parks (Singleton et al., 2017).

2 A human rights-based approach to marine conservation

2.1 What are human rights?

Human rights are possessed by all persons, by virtue of their common humanity, to live a life of freedom and dignity (Winer et al., 2007). They are universal and non-discriminatory (held equally by all human beings), inalienable (they cannot be taken away), unconditional (they do not depend on behaviour), indivisible (they all have equal status) and interdependent and interrelated (they are all equally important and they cannot be separated) (U.N., 2003; Newing and Perram, 2019). They embrace principles of participation and inclusion (all people are entitled to participate in, contribute to, and enjoy the realization of their rights), as well as that of accountability and Rule of Law (States and other duty-bearers are answerable for the observance of human rights) (U.N., 2003).

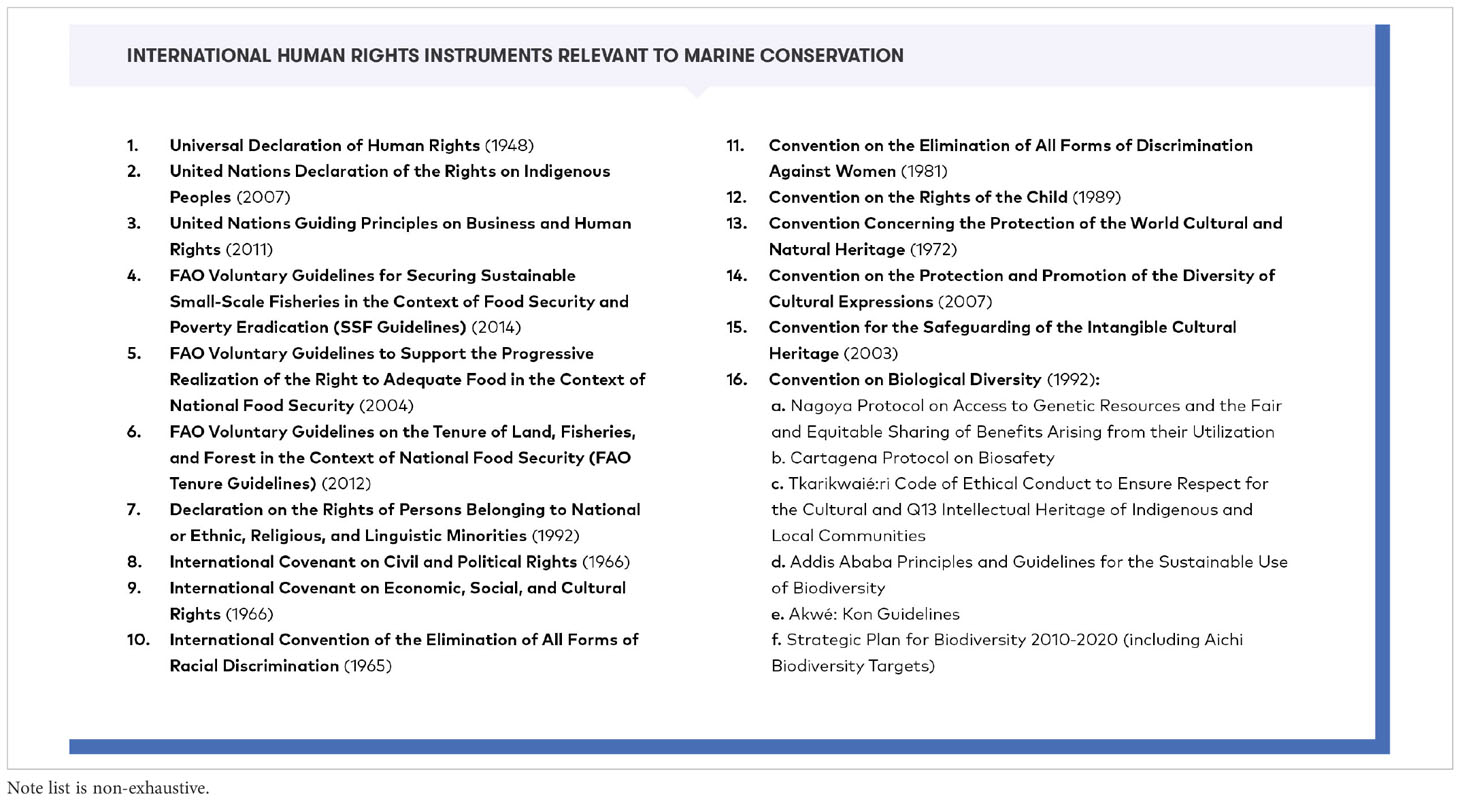

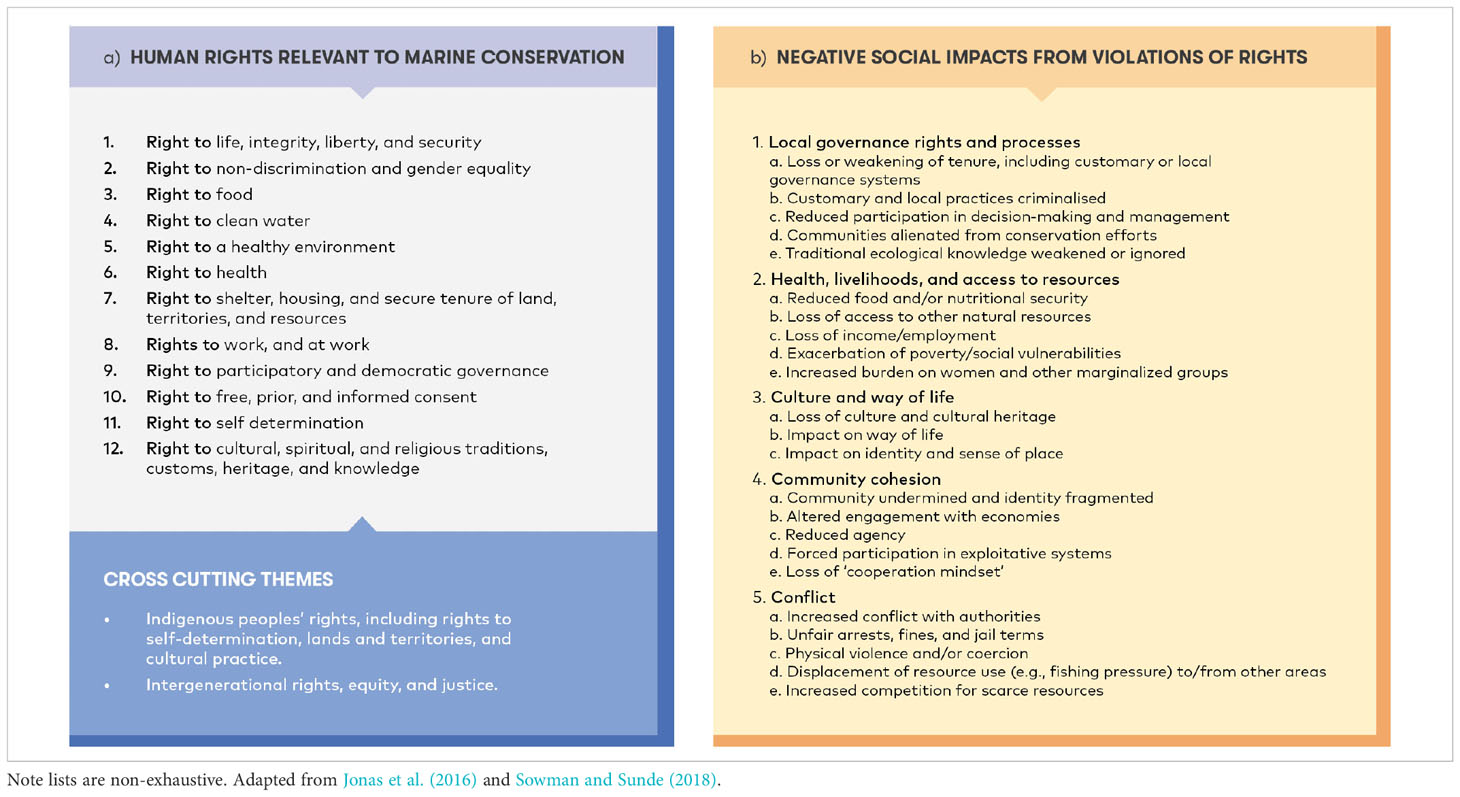

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, ratified in 1948, includes the right to life (Article 3); freedom from discrimination (Article 7); the right to not be “arbitrarily deprived of his [sic] property” (Article 17b); and the right to adequate standard of living and health, including food (Article 25a). In addition to individual rights there are also collective rights enshrined in legally binding agreements (e.g., International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, adopted 1966) as well as commitments (e.g., United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, adopted 2007), including: the right of all peoples to determine their own future; the right to own, possess, manage and use ancestral lands and natural resources; the right to participate in the management and conservation of resources on their lands; and more broadly; the right to participate effectively in decision-making in all matters that would affect their rights (Newing and Perram, 2019). Recently, the United Nations General Assembly also declared access to clean and healthy environment a universal human right (U.N., 2022a). Table 1 lists 12 international human rights standards that are of strong relevance in a marine conservation context and the negative social impacts that can accrue if they are violated. Table 2, adapted from Jonas et al. (2016), outlines key international instruments with human rights implications in the context of marine conservation.

Table 1 (A) Human rights of strong relevance for marine conservation and (B) the negative social impacts that can accrue from violations of these rights.

2.2 What responsibilities pertain to human rights?

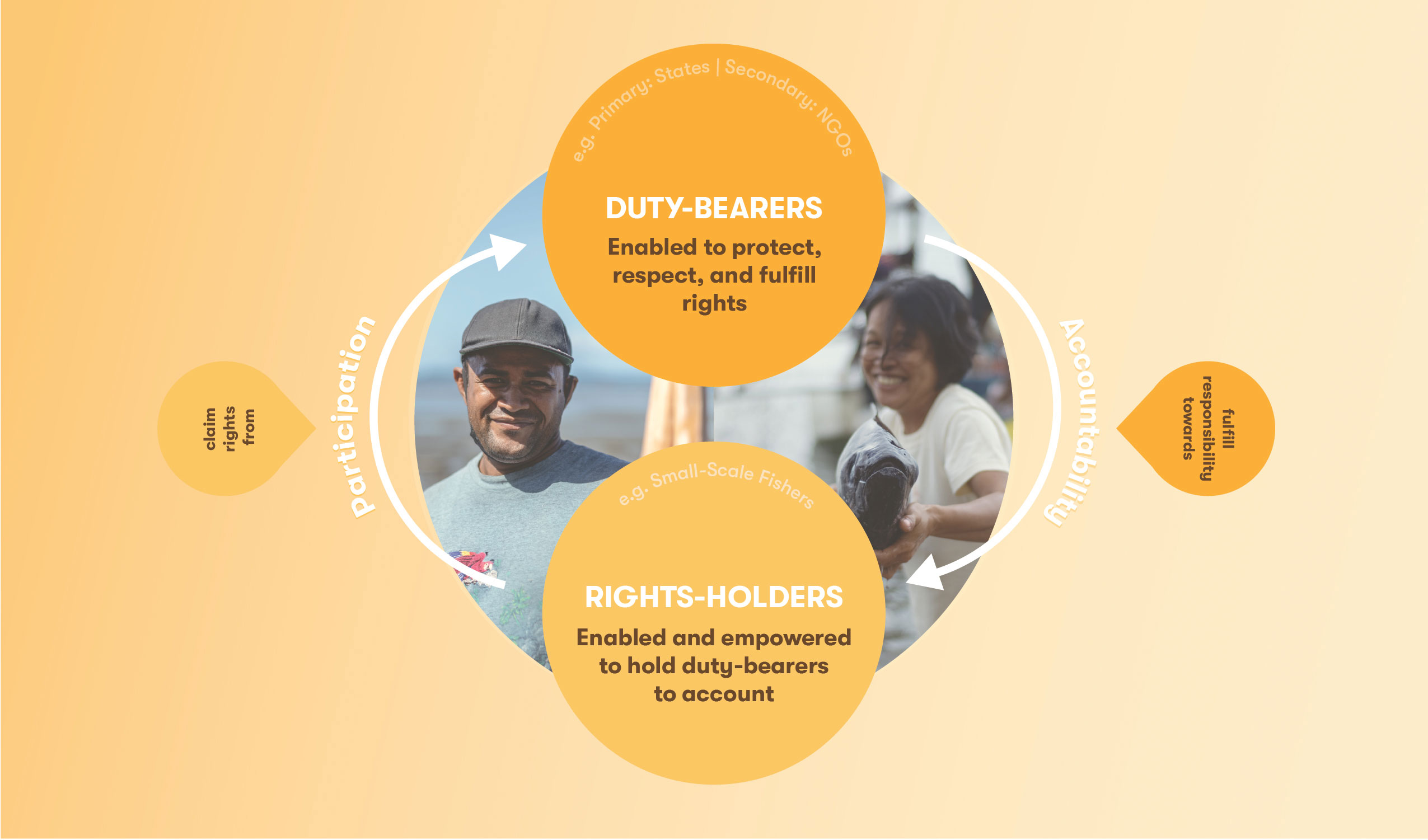

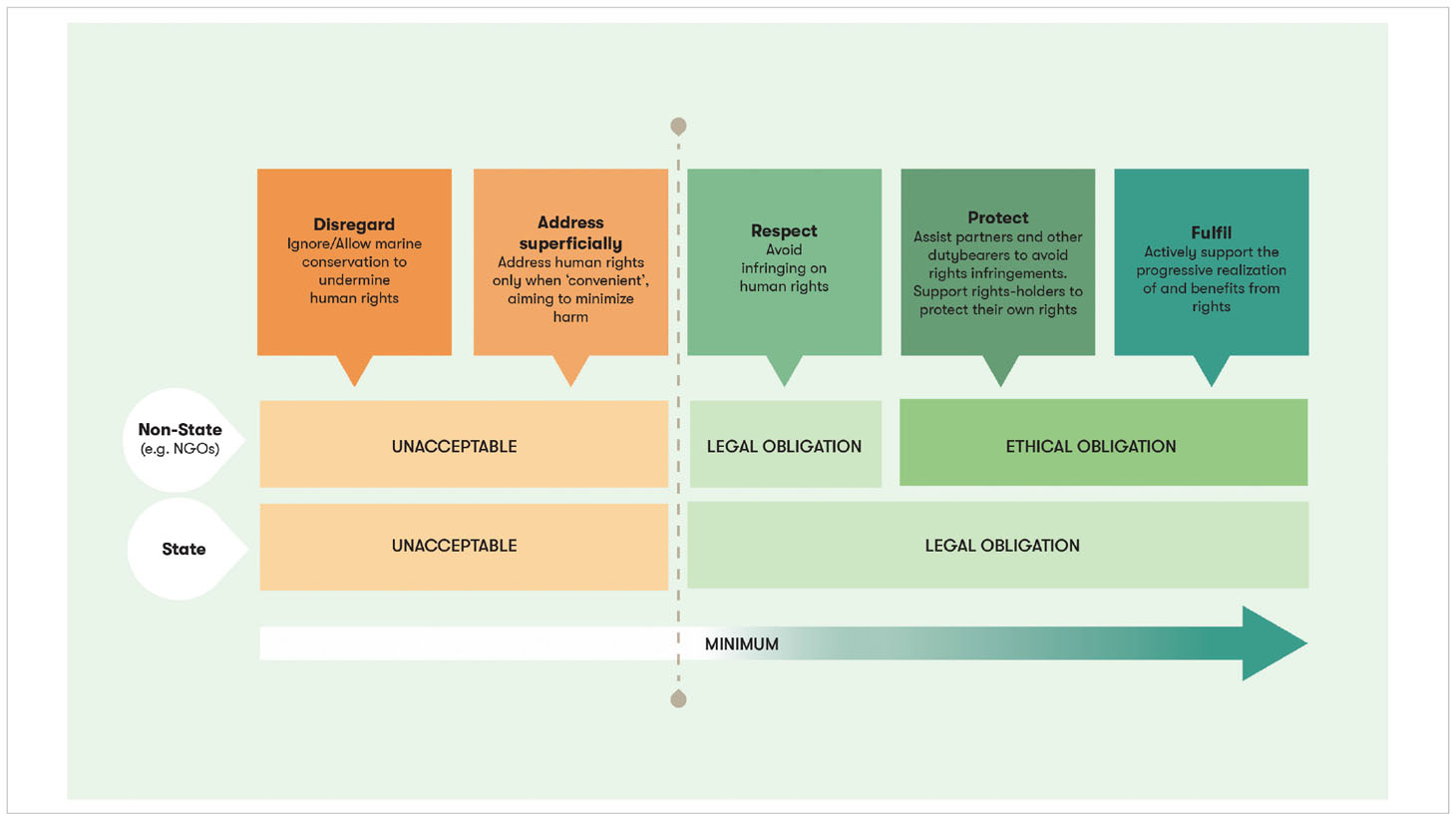

As rights, international law requires “duty bearers”, that is the actors collectively responsible for the realization of these rights, to respect (refrain from taking action that violates), protect (prevent the violation by others), and fulfil (enable people to claim and enjoy) the rights of “rights holders”, that is the individuals that have particular entitlements in relation to duty bearers (Winer et al., 2007) (Figure 2). Duty bearers are defined as an “entity or individual having a particular obligation or responsibility to respect, promote and realize human rights and to abstain from human rights violations. The term is most used to refer to State actors, but non-State actors can also be considered duty bearers” (U.N., 2017). Hence States are the primary duty bearers, and bear responsibility for implementing national laws that uphold human rights obligations. There is also growing recognition that states should take responsibility for the human rights effects of their policies in other countries, particularly regarding the obligations to respect and protect (Campese, 2009).

Figure 2 The relationship between Duty-Bearers and Rights-Holders. Photographers: Tom Vierus (left) and Rebecca Weeks (right).

Non-State actors are also increasingly being called to account to respect, protect, and fulfil human rights, and the increasingly powerful role of non-state conservation actors (e.g., NGOs) must carry increased human rights responsibility, even if ultimate responsibility lies with the state (Campese, 2009). For ‘for profit’ businesses, the United Nations Guiding principles on Business and Human Rights sets out responsibilities and makes clear the “responsibility to respect” (U.N., 2011; Jonas et al., 2016). Yet no formal human rights framework for accountability currently exists for ‘non profit’ NGOs as a negotiated and adopted document. Despite this limitation, with time it is likely that a more progressive interpretation will emerge, with NGOs, like businesses, requiring a minimum duty to respect human rights. Regardless, this responsibility warrants a minimum acceptable standard for the conduct of non-State actors rather than a level to aspire to. Non-State accountability should also neither weaken the role of the state, nor absolve responsibilities of states, since only states provide the institutional, policy, and legal framework within which civil society exists and exercises its rights (Campese, 2009).

Rights holders are the individuals or groups that have particular entitlements in relation to duty bearers. In the context of SSF, rights holders are the small-scale fishers, fish workers, their organizations, and the communities they are part of (FAO, 2015). They need to know their rights and be able to claim them. For instance, they should be able to participate in decision-making processes in a non-discriminatory and transparent manner, including access to free, prior, and informed consent (Hanna and Vanclay, 2013; U.N., 2014). They also need to be aware of ways to claim their right to food, to an adequate standard of living, and to decent working conditions, among others. Yet rights holders also bear certain responsibilities (U.N., 2022b), such as not infringing on the rights of others, raising challenging questions pertaining to marine conservation (Campese, 2009). For example, how can communities respect the rights of others, and fulfil their own, when resources are insufficient? Further, if rights holders are already struggling with scarcity, then how can they respect the rights of future generations to those same resources?

2.3 What is a human rights-based approach?

The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) describes a HRBA in the context of development as:

“a conceptual framework for the process of human development that is normatively based on international human rights standards and operationally directed to promoting and protecting human rights. It seeks to analyse inequalities that lie at the heart of development problems and redress discriminatory practices and unjust distributions of power that impede development progress. Under the HRBA, the plans, policies and processes [of conservation] are anchored in a system of rights and corresponding obligations established by international law, including all civil, cultural, economic, political and social rights, and the right to development. HRBA requires human rights principles (universality, indivisibility, equality and non-discrimination, participation, accountability) to guide United Nations development cooperation, and focus on developing the capacities of both ‘duty-bearers’ to meet their obligations, and ‘rights-holders’ to claim their rights.” (OHCHR, 2006, p. 15).

In simple terms, extending an HRBA to conservation practice means that conservation policies, governance and management do not violate human rights and that those implementing such policies actively seek ways to support and promote human rights in their design and implementation (Human Rights in Biodiversity Working Group, 2022). Regarding SSF, an HRBA is operationalized through the Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries in the Context of Food Security and Poverty Eradication (SSF Guidelines) (FAO, 2015). These guidelines were developed through a participatory process incorporating more than 4000 fishers, fish workers, and fisher representatives from 120 countries and represent a global consensus on principals and guidance for SSF governance and development (FAO, 2015).

The United Nations Statement of Common Understanding towards a Human Rights-Based Approach (U.N., 2003) provides a consensus-based interpretation of how an HRBA should be operationalized for development, also pertaining to conservation:

First, “all programmes … should further the realisation of human rights as laid down in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments”. This means that conservation programs only incidentally contributing to the realization of human rights do not necessarily constitute an HRBA. Within an HRBA the explicit aim of activities is to contribute directly to the realization of one or several human rights (although not necessarily exclusively).

Second, “Human rights standards contained in, and principles derived from, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments guide all … programs in all sectors and in all phases of the programming process”. This includes all program sectors, such as: sustainable resource management, water and sanitation, governance, and nutrition. This also includes all phases, such as: planning, design (including goal setting, objectives, and strategies), implementation, and monitoring and evaluation.

Third, programs enable “duty-bearers to meet their obligations and of rights-holders to claim their rights”. This means that conservation programs incorporating an HRBA identify rights-holders (and their entitlements) and duty-bearers (and their obligations), and work towards strengthening the capacities of rights-holders to make their claims, and of duty-bearers to meet their obligations.

According to The United Nations Statement of Common Understanding towards an HRBA (U.N., 2003), the following elements are necessary, specific, and unique to an HRBA:

A. Assessment and analysis to identify the human rights claims of rights-holders and the corresponding human rights obligations of duty-bearers as well as the immediate, underlying, and structural causes of the non-realization of rights.

B. Programmes to assess the capacity of rights-holders to claim their rights, and of duty-bearers to fulfill their obligations. They then develop strategies to build these capacities.

C. Programmes to monitor and evaluate both outcomes and processes guided by human rights standards and principles.

D. Programming informed by the recommendations of international human rights bodies and mechanisms.

Other elements of good programming practices that are also essential under an HRBA, include (U.N., 2003):

1. People are recognized as key actors in their own development, rather than passive recipients of commodities and services.

2. Participation is both a means and a goal.

3. Strategies are empowering, not disempowering.

4. Both outcomes and processes are monitored and evaluated.

5. Analysis includes all stakeholders.

6. Programmes focus on marginalized, disadvantaged, and excluded groups.

7. The development process is locally owned.

8. Programmes aim to reduce disparity.

9. Both top-down and bottom-up approaches are used in synergy.

10. Situation analysis is used to identity immediate, underlying, and basic causes of development problems.

11. Measurable goals and targets.

12. Strategic partnerships are developed and sustained.

13. Programmes support accountability to all stakeholders.

2.4 A human rights-based approach to co-management

Rather than replacing other conservation approaches, such as co-management, an HRBA instead enhances them by stressing the legal framework that includes obligations and declarations to human rights underpinning these approaches (Figure 3). We suggest that many of the good practice elements essential to an HRBA are also common to most local and collaborative governance strategies. For example, effective local and collaborative governance should support: the recognition of people as key actors in their own development, participation both as a means and a goal, empowerment, and focus on marginalized, disadvantaged, or excluded groups. Hence while an HRBA and local and collaborative governance may not be equivalent, they both often occur in ways that respect, protect, and fulfill rights, and hence are supportive of the same principles. Furthermore, adopting an explicit an HRBA within the marine conservation sector would also help bolster political, social, and economic support for nature stewardship by marginalized groups not or unable to be associated with local and collaborative governance arrangements.

Figure 3 A Human Rights-Based Approach enhances practices such as co-management by stressing the legal framework and human rights obligations that underpin these approaches.

3 Case studies: How human rights issues manifest in marine conservation

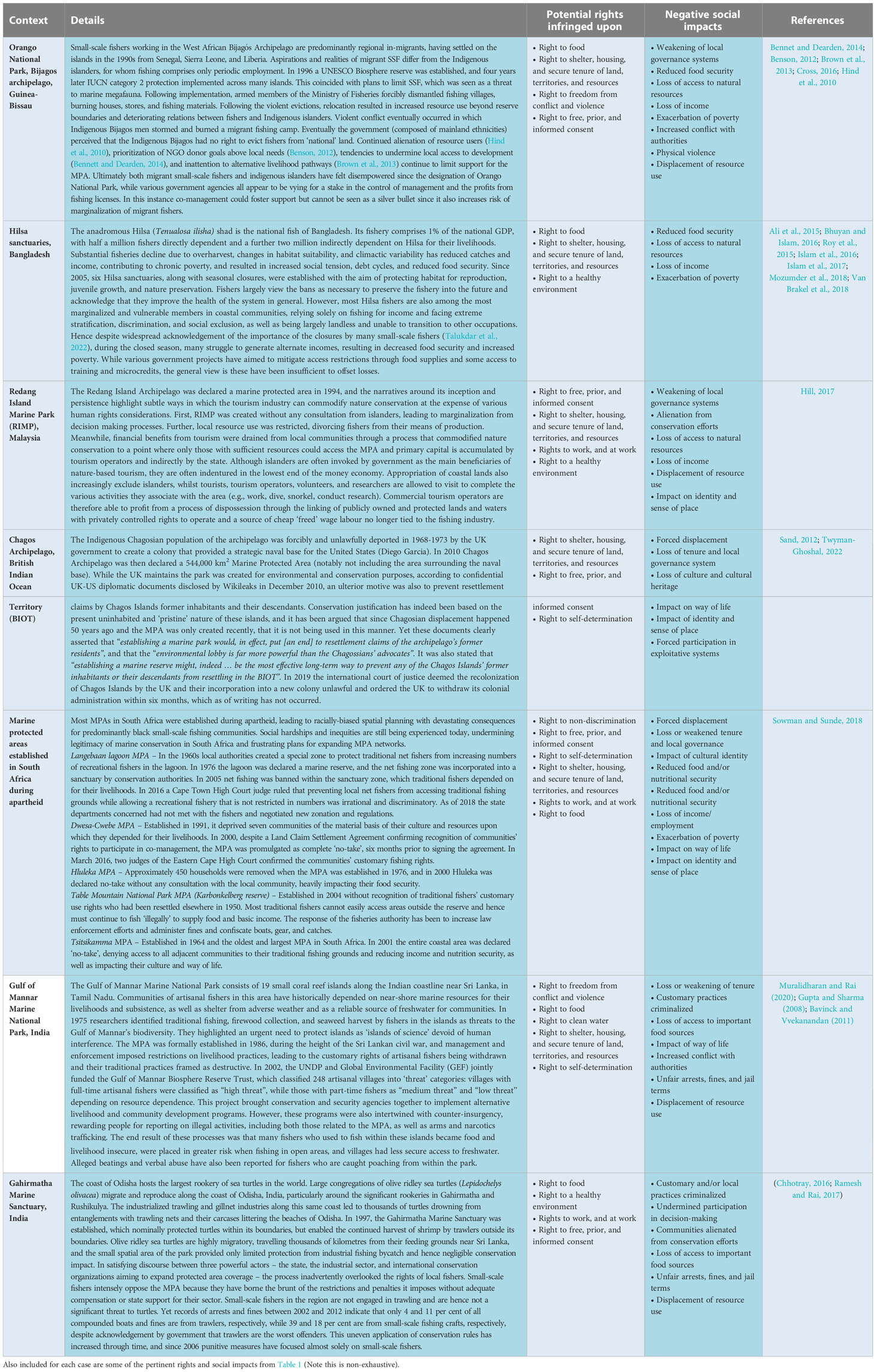

Tensions between marine conservation and human rights range from subtle to overt. They are heavily context dependant, and in many instances it is difficult to clearly identify infringements by State or non-State actors and whether they relate directly to marine conservation. Issues are often wicked, meaning they are difficult to delineate from bigger problems, they are not solved once in perpetuity, it can be unclear when they are solved, or even what solving it means, and solutions from one context might not be applicable in any other (Rittel and Webber, 1973). The aim of this section is not to imply rampant human rights abuses in the conservation sector, but rather emphasize the need to be aware of what rights are, and which ones conservation groups need to be sensitive to. Table 3 provides some case studies of where marine conservation initiatives have introduced recent tensions with human rights, acknowledging the many uncertainties, opinions, and externalities around each issue.

Table 3 Examples of tensions between marine conservation and human rights, with focus on small-scale fisheries and marine protected areas.

4 Legal and ethical obligations for marine conservationists to support human rights

4.1 Legal obligations for marine conservationist to support human rights

Legal obligations for marine conservationists to support human rights standards depend on the nature of those practising conservation. State actors engaged in marine conservation are the primary duty-bearers, and hence are obligated to respect, protect, and fulfill, human rights as the bottom-line. Non-State actors such as marine conservation NGOs must meet the minimum standard of respecting human rights. This means that they must “avoid infringing on the human rights of others and should address adverse human rights impacts with which they are involved” (Jonas et al., 2016; U.N., 2012). For example, when implementing a marine protected area that will limit the livelihoods, or nutritional security, of vulnerable peoples, conservation organizations have a legal responsibility to provide viable, sustainable, and better alternatives. Failure to do so constitutes a violation of these basic rights. The duty to respect rights is therefore categorical – whether support is given from the conservation sector should not be based on the ability to fulfil the needs of the sector. Not only are conservation organizations themselves signatories to various declarations, but they are also entities incorporated in countries that are signatories to various declarations affirming these rights (e.g., Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948; U.N., 2007; Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, 1981), as well as entities that operate in countries that are also signatories to these declarations (Newing & Perram, 2019).

While we acknowledge that the primary mandate of conservation NGOs is often not human wellbeing, the legal obligation to respect rights while practicing conservation is irrespective of overarching objectives – hence claims of ends justifying means are insufficient in this respect (Allison et al., 2012). We also acknowledge that not practicing conservation and having resources depleted may also infringe on the rights of others, specifically individual and community rights to a healthy environment, or the rights of future generations, leading to issues of trade-offs that can be difficult to resolve. While in many instances there are indeed common interests between conservationists and small-scale fishers, Indigenous Peoples, and local communities (see section five), it is critical to acknowledge genuine conflicts of interest where these exist and work towards negotiated settlements, with full respect for rights as the bottom line (Newing and Perram, 2019). This is not to say that international human rights law is perfect nor subject to change, but it should be acknowledged that these laws are the result of over half a century of negotiation and consensus building.

4.2 Ethical obligations for marine conservationists to support human rights

In practice, international human rights law can often be difficult to uphold. With many governments flagrantly violating human rights, why should marine conservation organizations in those same countries be bound to uphold them? Yet as nominal agents of positive global change, we argue that in addition to legal obligations, marine conservationists also have deep ethical obligations to support human rights. The ethical argument for marine conservation supporting human rights is based on the generalized principle that it is morally wrong for one people to dispossess, subjugate, or exterminate another people to promote their own ideological views (Diamond, 2005). While a key aim of conservation is to address the harms society is perceived to have inflicted upon nature, it must be acknowledged that this is only one issue, and only one way of viewing our interactions with non-human nature, among many (Allison et al., 2020) (Box 2). Just and equitable conservation is hence a moral imperative because it acknowledges the existing differences in how human-nature relations are understood.

Box 2 Western and Non-Western values of nature.

A fundamental premise in western philosophy is the differentiation between humankind and nature (Colchester, 1994; Redford, 1991). While this framework originated with the wilds in conflict with society, in the 19th century ideas were popularized considering wilderness as a place of refuge, with intrinsic value away from impacts wrought by society (Adams and Mulligan, 2003; Allison et al., 2020). These viewpoints underpin the modern western conservation movement, and hence have implications for how western countries conduct conservation today. For example, most western conservation organizations place principal value on concepts of ‘biodiversity’ and ‘wilderness’ (Callicott, 1990), although this does not disregard the importance for other cultures and societies of these same values. Rather it suggests that only two of the many intrinsic (e.g., diversity, animal welfare, Gaia, Mother Earth), instrumental (e.g., food, energy, and materials), and relational (e.g., way of life, social cohesion, cultural identity, sense of place) ways in which humanity can value nature (Allison et al., 2020) are promoted by western conservation, and thus a major portion of the global conservation movement. Understanding and acknowledging this makes clear the dynamic ways by which people value their place in nature (e.g., Smith, 1998). Thus while biodiversity and wilderness may be considered paramount for western conservationists, other values can be just as fundamental for different cultures and societies (Foale, 2001). Acknowledging this is a key step towards integrating equity, in particular recognitional equity, into modern conservation. In contrast, for many cultures it is difficult to distinguish society from nature, particularly those grounded within their local environment (Jupiter, 2017). In these instances, the intrinsic value of biodiversity and wilderness may not be shared, or may be difficult to meaningfully separate from ‘sustainable use’ (Foale et al., 2016; Jupiter, 2017) (Figure 4). Organizations proceeding to impose ‘fortress’ conservation to preserve primarily western values can therefore lead to substantial social impacts by perpetuating un-equal relationships, dispossessing peoples of their cultural and spiritual values, as well as limiting access to resources (Foale, 2001; Wilkie, 2017). Further, while most conservation projects focus on the global south (Chapin, 2004; Larsen and Brockington, 2018), accountability (i.e., funding, support, most head offices) is generally based in developed, western countries. While many of these organizations invest heavily in country programs, hiring nationals from those countries, there are often complex dynamics of power and privilege between headquarters and field programs, and these can be exacerbated by the often colonial nature of philanthropy and aid.

Equity and justice refer to the right and fair treatment of people (and nature see Sikor et al., 2014) – including the processes, application, and outcomes of public policy and organizational practices (e.g., Schlosberg, 2004; Fraser, 2009) – and hence provides foundational moral arguments for why human rights are important in marine conservation (Bennett, 2022). Pursuing equitable conservation requires attention to the three dimensions of justice that make up contemporary framings of environmental justice and equity, as well as how they relate to an HRBA (e.g., Bennett et al., 2021, Schlosberg, 2004; Pascual et al., 2014; Sikor et al., 2014). Recognitional justice relates to the status afforded to the human dignity of all peoples and the diversity of human experiences, including local rights, values, visions, knowledge, needs, and livelihoods in policy and practice (Pascual et al., 2014; Martin et al., 2016). Procedural justice is concerned with the fairness of how decisions are made and by whom (Ruano-Chamorro et al., 2022). This involves participation in decision-making by all relevant actors in rule and decision-making and good governance processes such as transparency and accountability (Seufert, 2013). Distributional justice relates to the fairness of how costs and benefits (including material, non-material, objective, subjective), opportunities, risks and responsibilities are distributed among different groups, including current and future generations (Gurney et al., 2021a). As an example of application to an HRBA, pursuing recognitional justice in conservation requires assessing the alignment between ontologies of human-nature relationships embedded in conservation and those held by different stakeholders and rightsholders. While conservation approaches, such as protected areas, tend to be underpinned by the western world view of humans as apart from nature, ontologies of human-nature relations held by many Indigenous cultures place humans as part of nature, and hence other management approaches endorsing sustainable use may be more applicable in these contexts.

Practically, the ethical imperative to support an HRBA in marine conservation means moving beyond minimum standards for respecting rights. It requires marine conservation to proactively support work to protect and fulfil rights. Protecting rights requires securing Indigenous Peoples and local communities tenure and governance authority over the resources in question. For example, protecting rights can be achieved by encouraging and building the capacity of partners (including other duty bearers and state actors) to respect rights, such as by specific rights-based actions in contractual arrangements, or through supporting rights holders themselves to build capacity and governance systems for protecting their own rights. Fulfillment of rights means Indigenous Peoples and local communities can both exercise their rights and subsequently benefit from those rights. Rights can be fulfilled by marine conservation organizations that identify areas to synergize conservation objectives and human rights objectives, so that conservation goals are reached in a way that also strengthens people’s rights. This can be achieved, for example, not only by supporting fisheries co-management initiatives that increase the health of marine ecosystems and strengthen traditional tenure rights (Cinner et al., 2012), but also enable fisheries to benefit from those resource improvements through overall abundance and food security or value-chain additions. Table 4 provides a spectrum along which marine conservation actions can occur in relation to respecting, protecting, and fulfilling human rights, as well as where the legal and ethical obligations lie.

Table 4 Legal and ethical obligations for state and non-state actors to support human rights in marine conservation.

5 Practical benefits for marine conservationist to support human rights

At the outset it is important to recognize that supporting human rights in conservation should be viewed as an end in and of itself, and not just a means to achieve conservation targets. This is not to say conservation organizations will conduct projects solely based on supporting human rights, their missions require conservation outcomes. But recognizing the critical role of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in conservation and including human rights and conservation targets alongside one another within conservation projects should be the norm rather than the exception.

The marine conservation sector increasingly recognizes the practical benefits that many local communities and fishers provide in maintaining biodiversity. In many instances fishers and local communities have long and deep histories of nature stewardship that situate them as global leaders in maintaining biodiversity and other natural values through collaborative governance systems, ancestral territorial management systems, and traditional knowledge and practices (Gurney et al., 2021b). Indeed, an increasingly large body of empirical evidence (e.g., Dawson et al., 2021; Oldekop et al., 2016) shows that supporting the rights of local people leads to consistently positive and enduring conservation impacts, and the marine sector is replete with evidence demonstrating biodiversity and ecosystem benefits from fisheries co-management, community-based marine conservation, and locally managed marine areas (e.g., Cinner et al., 2019; Villaseñor-Derbez et al., 2019; Gilchrist et al., 2020; Smallhorn‐West et al., 2020a; Cohen et al., 2021).

Whilst the marine conservation sector and one of the key tools it employs (i.e., MPAs) are underpinned by a primary objective of biodiversity conservation, there are many other forms of nature stewardship with other priorities and goals (e.g., maintain cultural practice, sustainable harvesting) that are also highly effective at maintaining biodiversity and ecosystem health, and in many cases more effective (Gurney et al., 2021b). These approaches, particularly when rooted in local customary practices, can lead to better conservation and social impacts, and can successfully navigate the complex interplay between people and marine ecosystems like coral reefs (Kapono et al., 2022). For example, global meta-analysis of 171 published studies of 165 protected areas demonstrated that protected areas associated with positive socioeconomic outcomes were also more likely to report positive conservation outcomes (Oldekop et al., 2016). In these studies, positive conservation outcomes were more likely to occur when protected areas adopted co-management regimes, empowered local people, reduced economic inequalities, and maintained cultural and livelihood benefits. Likewise, a review of 12 large MPAs (>10,000 km2) found correlations between participation, well-being, and ecosystem health (Ban et al., 2017). A review of 65 MPAs from the Pacific found that community-based and co-management governance was just as likely as centralized governance to produce positive ecological impacts (Smallhorn-West et al., 2020a). A systematic review of 169 publications investigating governance and conservation outcomes found that when interventions were controlled externally and involved strategies to change local practices and supersede customary institutions, they tended to result in relatively ineffective conservation at the same time as producing negative social outcomes (Dawson et al., 2021). This review suggested that equitable conservation represents the primary pathway to effective long-term conservation of biodiversity, and that it is most effective when fostering solutions that reinforce the role, capacity, and rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

Despite the significant practical benefits for marine conservationists to support human rights, these arguments should not be relied upon absolutely to justify adopting these approaches. For example, the current view held by most western conservation organizations appears to be that deep spiritual connections and cultural knowledge will foster strong environmental stewards, and that fishers, local communities, and Indigenous Peoples can often be allies and stewards because of these connections (Dawson et al., 2021). Yet this raises the important risk that if these movements fail in the future to drive positive impacts towards resource recovery, then they will lose value and be exchanged for strategies with greater impact. Indigenous knowledge is tremendously important for many reasons: it reflects the accumulated wisdom of unique cultures; it echoes the experiences of groups whose survival is threatened; and it offers important insights into sustainable use (Davis, 2009; U.N., 2014). But it is not always a given that cultural inhibitions will prevent adoption of unsustainable practices, or that alternate visions of nature-human balance will always conform to western interpretation of conservation (nor should they). Further, resource users who have been dispossessed, such as migrant fishers or refugees may not have long-term connections to their environment. Hence, it is reckless to invoke assumptions about the environmental practices of various peoples to justify treating them fairly, since if these assumptions are refuted, it is still wrong to mistreat people (Diamond, 2005). In this context, tensions remain about when the right to a healthy environment comes into conflict with other rights and conservation as a practice will need to evolve ways for understanding and balancing these nuanced situations.

6 Integrating human rights into marine conservation

Practically, what does an HRBA mean for how marine conservation organizations conduct their business, while ensuring they respect, protect, and fulfill people’s rights? Importantly, an HRBA is not a specific method or toolkit, but rather a lens through which to view how institutions attempt to influence power relations and how rights-holders hold the more powerful (i.e., duty-bearers) to account. Hence in the context of conservation, an HRBA provides the legal and ethical principles that motivate, guide, and bound what conservation actions are possible and socially beneficial. For example, whenever a project aims to support gender equity, they could be doing so out of a charitable desire to support women who have been marginalized or made vulnerable, or because they recognize that women have equal rights under international law – and hence are implicitly applying an HRBA. In this section we offer several suggestions for approaches and mechanisms that, if adopted, could significantly improve the uptake of human rights principles in marine conservation, including an HRBA.

6.1 Sequence investments in human rights and marine conservation

Pursuing a human rights-based agenda in marine conservation requires a diagnostic process in which those made vulnerable by the current societal structures are themselves the principal agents of change (Andrew et al., 2007; Allison et al., 2012). The key is to locate and target binding constraints on sustainable resource and conservation objectives and address those constraints first. Failure to do so will result in further actions also being subject to those same binding constraints (Hausmann et al., 2006). While in some instances this will still mean beginning with explicitly conservation focused projects, it is wrong to assume this will always be the most effective place to start (Allison et al., 2012). In many instances there are multiple dimensions of challenge for those who have been made vulnerable, many of which are external to specific marine issues. For example, vulnerability assessments of African fishing communities showed that concerns over the state of fish stocks were not found to be priorities in communities facing high crime rate, disease, climate change, and insecure resource access (Goulden, 2006; Thorpe et al., 2007; Mills et al., 2011; Barratt, 2012). In such circumstances, the need for conservation measures to halt overfishing may not be tied to the status of the fishery, but rather to these external factors. Marine conservationists aiming to support marginalized groups to effectively participate in conservation will therefore need to address the root causes of their vulnerabilities and insecurities (Allison et al., 2012). Solutions that work in a more developed system with secure fundamental rights, can fail, or exacerbate, both vulnerabilities and sustainability issues if applied where basic human rights are missing (Ratner and Baran, 2008).

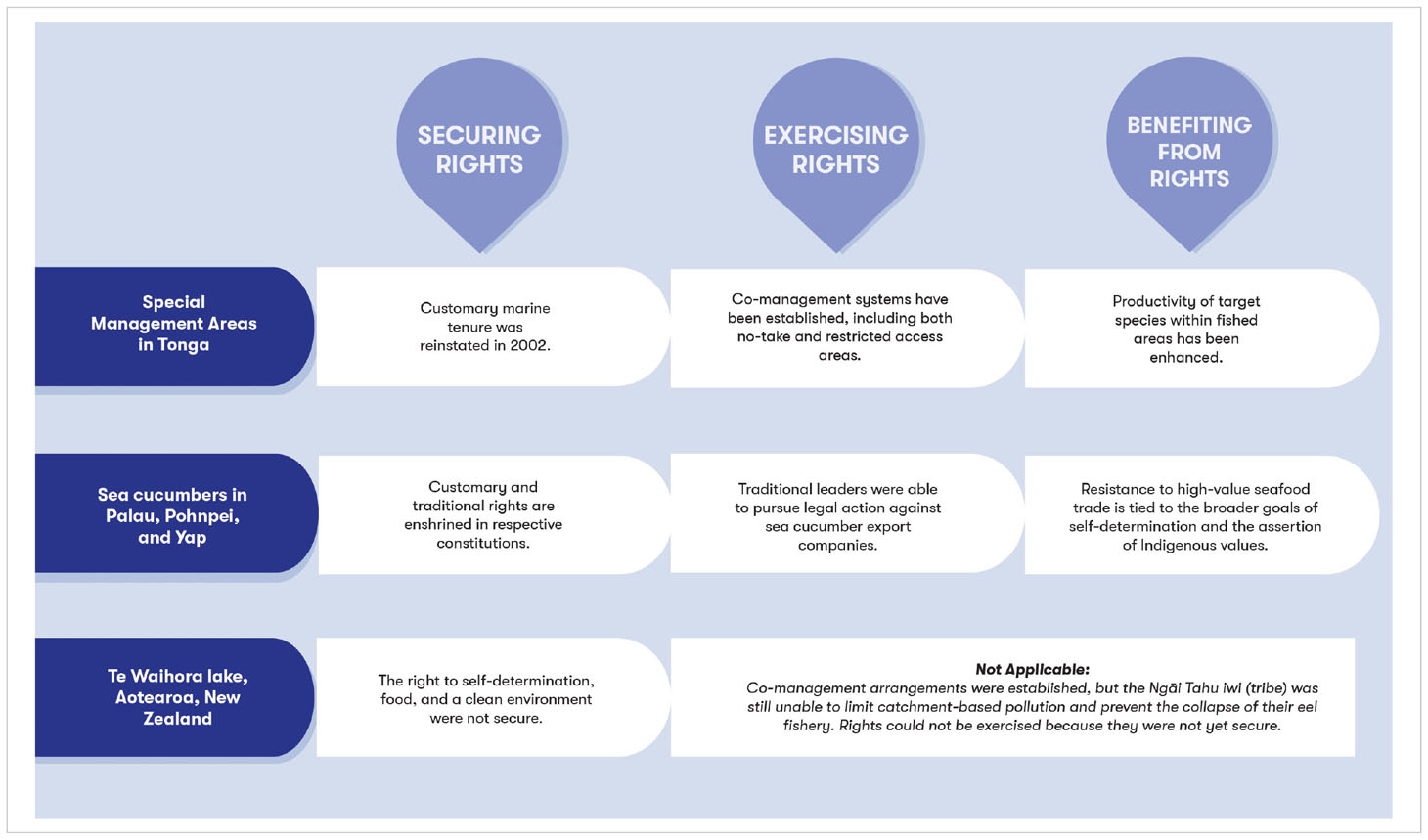

Sequencing marine conservation interventions implies that securing basic human rights is a necessary first step to ultimate conservation impact. Only once basic rights are secure can people then exercise those rights by addressing issues such as resource governance failures (e.g., impacts from external actors), including weak tenure rights, which can then begin to lead to biodiversity outcomes (Allison et al., 2012). For example, benefits will not accrue from even a perfectly designed co-management scheme if people are continuously subject to acts of violence and dispossession that limit their ability to participate in co-management. Likewise, only once people have both secure rights and the ability to exercise those rights is it useful to address remaining market failures that exacerbate sustainability and conservation issues, so that people and ecosystems can then begin to benefit from those rights. Investing out of sequence, for example by addressing market failures without first (or also) securing basic rights and then enabling people to exercise those rights will only accelerate depletion of resources by connecting them to more lucrative markets, hence further marginalizing vulnerable groups without tangible benefits for conservation (Karnad et al., 2021).

It is important to note that in some cases deep-rooted issues may also need to be tackled in parallel. For example, it is infeasible to wait until gender equality has been addressed before acting on the environment. In these instances, care needs to be taken to ensure rights issues are addressed while conservation actions occur, and to ensure those actions do not widen gender inequalities.

Three examples, two successful and one unsuccessful, highlight how this process can unfold in practice (Table 5). Note additional examples of these processes are also available in Allison et al. (2012) from Lake Victoria (Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania), Philippines, and Chile.

6.1.1 Special management areas in Tonga

During the 1980s and 1990s there were unsuccessful attempts to implement top-down, exclusionary MPAs in Tonga, and due to weak governance and limited respect for local fishing practices this only resulted in ‘paper parks’ (Likiliki and Haraldsson, 2006; Smallhorn-West & Govan, 2018). In 2002, Tonga implemented a two-part approach to local marine management that reinstated customary tenure and embraced participatory design principles, called the Special Management Area program (Likiliki and Haraldsson, 2006; Taufa and Tupou, 2018) (Figure 5). In exchange for implementing no-take reserves, the government also granted communities exclusive access to fishing zones around the reserves in which they could control resource use and regulations. This two-part system therefore supported securing legal access rights for fishers (i.e., acknowledging their right to fishing areas) in conjunction with developing co-management arrangements that enabled them to exercise those rights (i.e., the mechanism by which they could apply their rights). As such the program generated substantial local support so that by 2019 it had grown to include over 50% of coastal communities and more than 100 no-take or community fishing zones configured primarily in areas of historically high fishing pressure (Smallhorn-West et al., 2019, Smallhorn-West et al., 2020). Twenty years after its initial implementation there have been consistent benefits in biodiversity, fisheries biomass, density, and productivity in no-take reserves (Smallhorn-West, Stone, et al., 2020b), as well as enhanced fisheries productivity in areas that continue to be fished (Smallhorn-West et al., 2022c).

Figure 5 Small-scale fishers from the Lofanga Special Management Area in the Ha’apai island group of Tonga. Photographer: Patrick Smallhorn-West.

6.1.2 Sea cucumber fisheries in Palau, Pohnpei, and Yap

Sea cucumber or bêche-de-mer fisheries are notorious for ‘boom-bust’ cycles throughout the Pacific that provide limited local benefits (Crona et al., 2016), increase conflict within communities (Kaplan-Hallam et al., 2017), and increase inequity among fishers (Ferguson, 2021). In Palau, Pohnpei, and Yap, commercial harvest of sea cucumbers occurred intermittently throughout the 20th century for export to Asian markets. Yet despite overwhelming short-term financial incentives to harvest for export, in all three instances fishers, youth, elected and traditional leaders, and civil society organizations coordinated to ban the trade at its peak, using public protest, court battles, and customary and statutory law (Ferguson et al., 2022) (Figure 6). Because the rights of fishers and communities were sufficiently secured within customary and statutory law so that they could then proceed to exercise their right through local institutions and assertion of Indigenous values, they were able to then benefit from these actions, re-commonizing the resource and preventing fisheries collapse.

Figure 6 Citizens protest the sea cucumber trade in Pohnpei (source: “Block Unsustainable Sea Cucumber Harvest, Pohnpei”, Indiegogo Campaign). From Ferguson et al., 2022.

6.1.3 Te Waihora lake, Aotearoa (Lake Ellesmere, New Zealand)

Te Waihora is a Māori owned and governed coastal lake managed through the Indigenous-state co-governance agreement between the Ngāi Tahu iwi (tribe) and the Canterbury Regional Council (Lomax et al., 2015) (Figure 7). Historically, Te Waihora contained New Zealand’s most robust eel fishery. However, from 2000 – 2015 there was a dramatic expansion in dairy farming across the Te Waihora drainage basin, resulting in increased agricultural runoff and the eventual pollution driven collapse of the fishery. A government funded analysis stated that for the fishery to recover, Te Waihora required a 76% reduction in nitrogen and 50% reduction in phosphorous, requiring every dairy in the region to be shutdown. The Regional Council then requested a compliance exemption, on the grounds that the “social and economic consequences” would be “too severe” for farmers. This example demonstrates the problem with investing out of sequence: co-management in this case was ineffectual because the rights of the Ngāi Tahu iwi to control their coastal resources were not actually secure from upstream pollution sources. Hence these co-management arrangements failed because they were still subject to the same binding constraint of insecure resource rights – in this case the ability to manage water quality.

Figure 7 View of agricultural land adjacent to Te Waihora lake, Aotearoa (Lake Ellsemere, New Zealand).

6.2 Implement social safeguards and human rights impact assessments

Social safeguards are a set of mutually reinforcing processes designed to respect and protect the rights of people whose lives may be impacted by development or conservation actions (Wilkie et al., 2022). They act as a mechanism by which to identify and implement measures to avoid and mitigate adverse social impacts from conservation policy and practice. Globally acknowledged best-practice standards currently consider seven key social safeguards (World Bank, 2017). These include: 1) free, prior, and informed consent (U.N., 2007); 2) avoiding physical and economic displacement of rights-holders from their territories and homelands; 3) grievance redress in the face of impacts; 4) gender impact risk assessment; 5) human rights training for staff; 6) ensuring confidential source or informant consent; and 7) human subject’s protections in research.

Human rights impact assessments analyse the effects activities, including conservation activities, have on rights-holders (Harrison, 2011). This includes assessment of activities that directly and intentionally aim to alter human rights conditions, as well as actions that may have unintended human rights consequences. Impact assessments embrace counterfactual framing by asking ‘what would have happened in the absence of the intervention’? This faming can assess past activities (ex post), as well as planned future activities (ex ante). A common theme to human rights impact assessments is their evidence-based nature and concern with attempting to measure actual or potential human rights impacts (Bakker et al., 2009). The techniques by which this is done vary, as does the analytical rigour, but at the very least the goal is to use evidence to systematically bring human rights framing into program cycles (Landman, 2003).

While social safeguards and human rights impact assessments are necessary, they should not be applied formulaically or as one-size-fits-all solutions. Rather, they should be tailored to local ecological, social, cultural, and historical contexts, since projects differ both in their objectives and the risks they pose to affected communities (Humphrey, 2016). Applying single top-down standards can therefore lead to inadvertent rights violations (Wilkie et al., 2022). For example, attempting to impose a free, prior, and informed consent process on communities that requires naming of fishing access rights would be inappropriate in contexts where access rights are viewed as fluid. Likewise, different conservation interventions also require different safeguards, based on their risks to rights-holders. For example, informant intelligence on poaching from marine parks in conflict zones poses much greater risks than does understanding patterns of fish consumption for research subjects. Lastly, the most appropriate methodology to employ in each context should reflect the interests and preferred protocols of the rights-holders themselves, and risks will be best avoided or mitigated when rights-holders take the lead in determining relevant safeguards and assessment priorities for conservation in their context.

7 Conclusions

Acknowledging the contextuality of marine conservation activities, what generalized guidance might foster greater support for human rights and an HRBA in the sector? In simple terms, what does ‘doing’ marine conservation that embraces human rights principles look like? We suggest that, in general, marine conservation practices that are aligned with an HRBA and respecting, protecting, and fulfilling people’s rights will have many of the following characteristics (note this list is non-exhaustive):

1. Acknowledges that all people have basic rights that must be supported and understands that conservationists are duty-bound to respect those rights.

2. Supports the empowerment of fishers, Indigenous Peoples, and local communities, as leaders of nature stewardship in their own right, as well as being allies in support of biodiversity conservation.

3. Acknowledges that not all people in situations of vulnerability have deep connections to country, but all people still have fundamental rights regardless of their ability to support conservation.

4. Inherent respect for anti-racism, non-discrimination, diversity and gender equality principles.

5. Recognizes people as key actors in their own development, rather than passive recipients of commodities and services.

6. Focuses supportive actions towards those most marginalized, disadvantaged, and excluded.

7. Promotes long-term environmental and social security over short-term targets, since short-termism exacerbates inequitable results and leads to net negatives over time.

8. Acknowledges that increased vulnerability reduces people’s agency to adopt sustainable practices, and hence securing human rights can be a good conservation investment.

9. Implements policies and actions that address the root causes of vulnerabilities and insecurities.

10. Understands that conservation gains achieved through human rights violations will increase disenfranchisement, widen inequalities, potentially increase resource dependence, and heighten resistance to current and future conservation activities.

Conversely marine conservation policies and programs that fail to uphold human right-based principles in a meaningful way will have many of the following characteristics: (but are not limited to, and ranging from overt to subtle):

1. Overt violations of people’s rights, including forced displacement, food insecurity, increased poverty, violence, or coercion.

2. Respect for human rights only if they help achieve conservation targets, or through superficial or tick the box approaches, but not as a bottom line that cannot be crossed.

3. View people (including fishers, Indigenous Peoples, and local communities) fundamentally as opportunity costs and hazards that limit conservation from ‘getting done’, rather than allies in the process.

4. A focus on western concepts of nature, including intrinsic values of biodiversity and wilderness, as of greater importance than other values or concepts of nature stewardship. For example, by viewing the values of fishers and local communities as secondary to the ‘main goal’ of biodiversity conservation.

5. Paternalistic interactions with stakeholders, for example by external actors ‘knowing best’ and ‘doing’ conservation in regions with little engagement or understanding of local context, desires, or needs.

6. A lack of free, prior, and informed consent of stakeholders.

7. Limited or no acknowledgement of, or offset of, socioeconomic costs incurred by people from conservation actions. This includes failing to address the root causes of vulnerabilities.

8. Failure to account for the vulnerability of those affected, nor understanding that those marginalized and disadvantaged typically bear disproportionate costs.

9. Limited understanding of equity and justice principles, that is an understanding of social, economic, and political conditions that influence peoples pre-existing status.

10. Unwillingness to acknowledge positionality and historic transgressions by conservation actors, including the need to recognize intergenerational trauma.

As 196 countries around the world continue to negotiate the CBD Post-2020 Biodiversity Framework that will guide future conservation policy, we argue that human rights in general, and an HRBA specifically, should be a foundational component of effective and equitable conservation policy. While an HRBA cannot resolve all issues, it provides a useful framework for understanding key issues and grievances, as well as a minimum standard that should not be ‘traded-off’ in negotiations (Filmer-Wilson and Anderson, 2005). While some might argue this can be a slower pathway to conservation impact, inclusive and broader reaching processes that focus on the underlying or distal drivers of poverty and vulnerability can bring much more lasting outcomes. Conversely, if conservation gains are achieved through human rights violations, then this will only increase disenfranchisement, widen inequalities, potentially increase resource dependence, and heighten resistance to current and future conservation activities, ultimately leading to non-compliance and ineffective biodiversity conservation.

We acknowledge the interdependence of nature and people – that biological and cultural diversity are interconnected and mutually reinforcing. We acknowledge that Indigenous Peoples and local communities frequently represent the most active defenders of nature, and we believe that respecting and protecting their rights is the best pathway to achieving durable conservation impact. We also believe that conservation stakeholders are uniquely positioned to address human rights issues at this juncture in history – many are acknowledging the injustices of the past, are taking corrective action, and are seeking ways to move towards just and regenerative conservation that embraces principles of equity and respect.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

PSW, EA, GG, HN, HP, AT & SR conceived the initial form of this manuscript. DK, HK, ASL, SM, HW, and KP contributed to follow up versions and provided input on writing, language, and arguments. All authors contributed to the final version of this manuscript.

Funding

This work was undertaken as part of the CGIAR Research Initiative on Resilient Aquatic Food Systems for Healthy People and Planet, and funded by CGIAR Trust Fund donors. Funding support for this work was provided by CGIAR Trust Fund donors, the Wildlife Conservation Society, and the Australian Research Council Centre for Excellence in Coral Reef Studies, James Cook University.

Acknowledgments

In the spirit of reconciliation, we acknowledge that many of us live and work on unceded lands. We therefore acknowledge the Traditional Owners and Custodians of the land and sea country on which we work, and pay our respects to their Elders, past, present, and emerging.

Conflict of interest

Author Sangeeta Mangubhai was employed by company Talanoa Consulting.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adams W. B., Mulligan M. (2012). Decolonizing nature: Strategies for conservation in a post-colonial era. Routledge.

Ali M. Y., Rahmatullah R., Asadujjaman M., Bablu M. G. U., Sarwer M. G. (2015). Impacts of banning period on the socio-economic condition of hilsa fishermen in shakhchor union of lakshmipur sadar upazila, Bangladesh. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 23, 2479–2483.

Allison E. H., Kurien J., Ota Y., Adhuri D. S., Bavinck J. M., Cisneros Montemayor A., et al. (2020). The human relationship with our ocean planet. Blue paper commissioned by the High Level Panel for A Sustainable Ocean Economy. Available at: https://oceanpanel.org.

Allison E. H., Ratner B. D., Åsgård B., Willmann R., Pomeroy R., Kurien J. (2012). Rights-based fisheries governance: From fishing rights to human rights. Fish Fisheries 13 (1), 14–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2979.2011.00405.x

Andrew N. L., Béné C., Hall S. J., Allison E. H., Heck S., Ratner B. D. (2007). Diagnosis and management of small-scale fisheries in developing countries. Fish Fisheries 8 (3), 227–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2679.2007.00252.x

Bakker S., Van Den Berg M., Düzenli D., Radstaake M. (2009). Human rights impact assessment in practice: The case of the health rights of women assessment instrument (HeRWAI). J. Hum. Rights Pract. 1 (3), 436–458. doi: 10.1093/jhuman/hup017

Ban N. C., Davies T. E., Aguilera S. E., Brooks C., Cox M., Epstein G., et al. (2017). Social and ecological effectiveness of large marine protected areas. Global Environ. Change 43, 82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2017.01.003

Barratt C. (2012). Netting the benefits now or later? Exploring the relationship between risk and sustainability in lake Victoria fisheries, uganda. in. Risk Afr. Multi-disciplinary Empirical Approaches.

Bavinck M., Vivekanandan V. (2011). Conservation, conflict and the governance of fisher wellbeing: Analysis of the establishment of the Gulf of Mannar National Park and Biosphere Reserve. Environmental Management 47(4), 593–602.

Bennett N. J. (2022). Mainstreaming equity and justice in the ocean. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 587. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.873572

Bennett N. J., Blythe J., White Campero C. S.C. (2021). Blue growth and blue justice: Ten risks and solutions for the ocean economy. Marine Policy 125, p.104387.

Bennett N. J., Dearden P. (2014). Why local people do not support conservation: community perceptions of marine protected area livelihood impacts, governance and management in Thailand. Marine Policy 44, 107–116

Benson C. (2012). Conservation NGOs in Madang, Papua New Guinea: understanding community and donor expectations. Society & Natural Resources 25, 71–86

Bhuyan S., Islam S. (2016). Present status of socio-economic conditions of the fishing community of the meghna river adjacent to narsingdi district. Bangladesh. J. Fish. Livest. Prod 4 (4), 1–5.

Brown N. K., Gray T. S., Stead S. M. (2013). Co-management and adaptive co-management: two modes of governance in a Honduran marine protected area. Marine Policy 39, 128–134.

Campese J. (2009). Rights-based approaches: Exploring issues and opportunities for conservation. CIFOR.

Chapin M. (2004) A challenge to conservationists. Available at: www.worldwatch.org.

Chhotray V. (2016). Justice at Sea: Fishers’ politics and marine conservation in coastal Odisha, India. Maritime Studies 15, 1–24.

Cinner J. E., Lau J. D., Bauman A. G., Feary D. A., Januchowski-Hartley F. A., Rojas C. A., et al. (2019). Sixteen years of social and ecological dynamics reveal challenges and opportunities for adaptive management in sustaining the commons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116 (52), pp.26474–26483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1914812116

Cinner J. E., McClanahan T. R., MacNeil M. A., Graham N. A., Daw T. M., Mukminin A., et al. (2012). Comanagement of coral reef social-ecological systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109 (14), 5219–5222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121215109

Cohen P. J., Allison E. H., Andrew N. L., Cinner J., Evans L. S., Fabinyi M., et al. (2019). Securing a just space for small-scale fisheries in the blue economy. Front. Mar. Sci. 6, 171. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00171

Cohen P. J., Roscher M., Wathsala Fernando A., Freed S., Garces L., Jayakody S., et al. (2021). Characteristics and performance of fisheries co-management in Asia: Synthesis of knowledge and case studies: Bangladesh, Cambodia, Philippines and Sri Lanka. Food Agric. Org.

Colchester M. (1994). Salvaging Nature: indigenous peoples, protected areas and biodiversity conservation. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/284691747.

Crona B. I., Basurto X., Squires D., Gelcich S., Daw T. M., Khan A., et al. (2016). Towards a typology of interactions between small-scale fisheries and global seafood trade. Mar. Policy 65, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2015.11.016

Crosman K. M., Jurcevic I., Van Holmes C., Hall C. C., Allison E. H. (2022). An equity lens on behavioral science for conservation. Conserv. Lett. 15 (5), e12885. doi: 10.1111/conl.12885

Cross H. (2016). Displacement, disempowerment and corruption: Challenges at the interface of fisheries, management and conservation in the bijagós archipelago, Guinea-Bissau. Oryx 50 (4), 693–701. doi: 10.1017/S003060531500040X

Dawson N. M., Coolsaet B., Sterling E. J., Loveridge R., Gross-Camp N. D., Wongbusarakum S., et al. (2021). The role of indigenous peoples and local communities in effective and equitable conservation. Ecology and Society 26 (3), 19. doi: 10.5751/ES-12625-260319

FAO (2015). Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries in the Context of Food Security and Poverty Eradiction, Committee on World Food Security. Retrieved from https://policycommons.net/artifacts/2132725/voluntary-guidelines-for-securing-sustainable-small-scale-fisheries-in-the-context-of-food-security-and-poverty-eradiction/2888023/ on 07 Feb 2023. CID: 20.500.12592/6trcbc.

Ferguson C. E. (2021). A rising tide does not lift all boats: Intersectional analysis reveals inequitable impacts of the seafood trade in fishing communities. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 246. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.625389

Ferguson C. E., Bennett N. J., Kostka W., Richmond R. H., Singeo A. (2022). The tragedy of the commodity is not inevitable: Indigenous resistance prevents high-value fisheries collapse in the pacific islands. Global Environ. Change 73, 102477. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2022.102477

Filmer-Wilson E., Anderson M. (2005). Integrating human rights into energy and environment programming: A reference paper. Nova York: PNUD.

Foale S. (2001). ‘Where's our development?’ landowner aspirations and environmentalist agendas in Western Solomon islands. Asia Pacific J. Anthropology 2 (2), pp.44–pp.67.

Foale S., Dyer M., Kinch J. (2016). The value of tropical biodiversity in rural Melanesia. Valuation Stud. 4 (1), pp.11–pp.39. doi: 10.3384/VS.2001-5992.164111

Fraser N. (2009). Scales of justice: Reimagining political space in a globalizing world Vol. Vol. 31) (USA: Columbia University Press).

Gilchrist H., Rocliffe S., Anderson L. G., Gough C. L. (2020). Reef fish biomass recovery within community-managed no take zones. Ocean Coast. Manage. 192, 105210. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2020.105210

Goulden M. C. (2006). Livelihood diversification, social capital and resilience to climate variability amongst natural resource dependent societies in Uganda (Doctoral dissertation, university of East Anglia).

Gupta C., Sharma M. (2012). Contested coastlines: Fisherfolk, nations and borders in South Asia. Routledge India.

Gurney G. G., Darling E. S., Ahmadia G. N., Agostini V. N., Ban N. C., Blythe J., et al. (2021b). Biodiversity needs every tool in the box: use OECMs. Nature 595 (7869), 646–649.

Gurney G. G., Mangubhai S., Fox M., Kim M. K., Agrawal A. (2021a). Equity in environmental governance: perceived fairness of distributional justice principles in marine co-management. Environ. Sci. Policy 124, 23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2021.05.022

Hanna P., Vanclay F. (2013). Human rights, indigenous peoples and the concept of free, prior and informed consent. Impact Assess. Project Appraisal 31 (2), 146–157. doi: 10.1080/14615517.2013.780373

Harrison J. (2011). Human rights measurement: Reflections on the current practice and future potential of human rights impact assessment. J. Hum. Rights Pract. 3 (2), 162–187. doi: 10.1093/jhuman/hur011

Hill A. (2017). Blue grabbing: reviewing marine conservation in redang island marine park, Malaysia. Geoforum 79, 97–100. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.12.019

Hind E. J., Hiponia M. C., Gray T. S. (2010). From community-based to centralised national management—A wrong turning for the governance of the marine protected area in Apo Island, Philippines? Marine policy 34(1), pp.54–62.

Humphrey C. (2016). Time for a new approach to environmental and social protection at multilateral development banks. Overseas Dev. Institute April.

Islam M. M., Islam N., Sunny A. R., Jentoft S., Ullah M. H., Sharifuzzaman S. M. (2016). Fishers’ perceptions of the performance of hilsa shad (Tenualosa ilisha) sanctuaries in Bangladesh. Ocean Coast. Manage. 130, 309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2016.07.003

Islam M. M., Shamsuzzaman M. M., Mozumder M. M. H., Xiangmin X., Ming Y., Jewel M. A. S. (2017). Exploitation and conservation of coastal and marine fisheries in Bangladesh: Do the fishery laws matter? Mar. Policy 76, 143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2016.11.026

Jonas H., Makagon J., Roe D. (2016). Conservation standards. From Rights to Responsibilities. London: IIED

Jupiter S. (2017). Culture, kastom and conservation in Melanesia: What happens when worldviews collide? Pacific Conserv. Biol. 23 (2), 139–145.

Kamat V. R. (2018). Dispossession and disenchantment: The micropolitics of marine conservation in southeastern Tanzania. Mar. Policy 88, 261–268. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2017.12.002

Kaplan-Hallam M., Bennett N. J., Satterfield T. (2017). Catching sea cucumber fever in coastal communities: Conceptualizing the impacts of shocks versus trends on social-ecological systems. Global Environ. Change 45, 89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2017.05.003

Kapono C., Kain M., Raj S., Rao M. (2022) Centring indigenous-led governance of coral reefs. Available at: https://ocean.economist.com/governance/articles/prioritising-indigenous-led-governance-of-coral-reefs.

Karnad D., Gangadharan D., Krishna Y. C. (2021). Rethinking sustainability: From seafood consumption to seafood commons. Geoforum 126, 26–36.

Likiliki P. M., Haraldsson G. (2006). Fisheries co-management and the evolution towards community fisheries management in Tonga. Reykjavik Iceland: United Nations University.

Lomax A., Johnston K. A., Hughey K., Taylor K. J. W. (2015). Te Waihora/Lake Ellesmere: state of the lake 2015 (New Zealand: Waihora Ellesmere Trust).

Martin A., Coolsaet B., Corbera E., Dawson N. M., Fraser J. A., Lehmann I., et al. (2016). Justice and conservation: The need to incorporate recognition. Biol. Conserv. 197, 254–261. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2016.03.021

Mills D., Béné C., Ovie S., Tafida A., Sinaba F., Kodio A., et al. (2011). Vulnerability in African small-scale fishing communities. J. Int. Dev. 23 (2), 308–313. doi: 10.1002/jid.1638

Mozumder M. M. H., Wahab M. A., Sarkki S., Schneider P., Islam M. M. (2018). Enhancing social resilience of the coastal fishing communities: A case study of hilsa (Tenualosa ilisha h.) fishery in Bangladesh. Sustainability 10 (10), 3501. doi: 10.3390/su10103501

Muralidharan R., Rai N. D. (2020). Violent maritime spaces: Conservation and security in gulf of mannar marine national park, India. Political Geogr. 80, 102160. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102160

Newing H., Perram A. (2019). What do you know about conservation and human rights? Oryx 53 (4), 595–596. doi: 10.1017/S0030605319000917

Oldekop J. A., Holmes G., Harris W. E., Evans K. L. (2016). A global assessment of the social and conservation outcomes of protected areas. Conserv. Biol. 30 (1), 133–141. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12568

Pascual U., Phelps J., Garmendia E., Brown K., Corbera E., Martin A., et al. (2014). Social equity matters in payments for ecosystem services. Bioscience 64 (11), 1027–1036. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biu146

Ramesh M., Rai N. D. (2017). Trading on conservation: A marine protected area as an ecological fix. Mar. Policy 82, 25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2017.04.020

Ratner B. D., Åsgård B., Allison E. H. (2014). Fishing for justice: Human rights, development, and fisheries sector reform. Global Environ. Change 27, 120–130. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.05.006

Ratner B. D., Baran E. (2008). From sound economics to sound management: Practical solutions to small-scale fisheries governance in the developing world. MAST 6(2), 29–33

Rittel H. W., Webber M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 4 (2), 155–169. doi: 10.1007/BF01405730

Roy N. C., Rahman M. A., Haque M. M., Momi M. A., Habib A. Z. (2015). Effects of incentive based hilsa shad (Tenualosa ilisha) management and conservation strategies in Bangladesh. J. Sylhet Agric. Univ 2, 69–77.

Ruano-Chamorro C., Gurney G. G., Cinner J. E. (2022). Advancing procedural justice in conservation. Conserv. Lett. 15 (3), e12861. doi: 10.1111/conl.12861

Sand P. H. (2012). Fortress conservation trumps human rights? the “marine protected area” in the chagos archipelago. J. Environ. Dev. 21 (1), 36–39. doi: 10.1177/1070496511435666

Schlosberg D. (2004). Reconceiving environmental justice: Global movements and political theories. Environ. politics 13 (3), 517–540. doi: 10.1080/0964401042000229025

Seufert P. (2013). The FAO voluntary guidelines on the responsible governance of tenure of land, fisheries and forests. Globalizations 10 (1), 181–186. doi: 10.1080/14747731.2013.764157

Sikor T., Martin A., Fisher J., He J. (2014). Toward an empirical analysis of justice in ecosystem governance. Conserv. Lett. 7 (6), 524–532. doi: 10.1111/conl.12142

Singleton R. L., Allison E. H., Le Billon P., Sumaila U. R. (2017). Conservation and the right to fish: International conservation NGOs and the implementation of the voluntary guidelines for securing sustainable small-scale fisheries. Mar. Policy 84, 22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2017.06.026

Smallhorn-West P. F., Bridge T. C., Malimali S. A., Pressey R. L., Jones G. P. (2019). Predicting impact to assess the efficacy of community-based marine reserve design. Conserv. Lett. 12 (1), e12602. doi: 10.1111/conl.12602

Smallhorn-West P., Govan H. (2018). Towards reducing misrepresentation of national achievements in marine protected area targets. Mar. Policy 97, 127–129. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2018.05.031

Smallhorn-West P. F., Sheehan J., Malimali S. A., Halafihi T., Bridge T. C., Pressey R. L., et al. (2020b). Incentivizing co-management for impact: mechanisms driving the successful national expansion of tonga's special management area program. Conserv. Lett. 13 (6), e12742. doi: 10.1111/conl.12742

Smallhorn-West P. F., Stone K., Ceccarelli D. M., Malimali S. A., Halafihi T. I., Bridge T. C., et al. (2020c). Community management yields positive impacts for coastal fisheries resources and biodiversity conservation. Conserv. Lett. 13 (6), e12755. doi: 10.1111/conl.12755

Smallhorn-West P. F., Weeks R., Gurney G., Pressey R. L. (2020a). Ecological and socioeconomic impacts of marine protected areas in the south pacific: Assessing the evidence base. Biodiversity Conserv. 29 (2), 349–380. doi: 10.1007/s10531-019-01918-1

Smallhorn-West P., Cohen P. J., Morais R. A., Januchowski-Hartley F. A., Ceccarelli D. M., Malimali S. A., et al. (2022). Hidden benefits and risks of partial protection for coral reef fisheries.

Smith D. M. (1998). An athapaskan way of knowing: Chipewyan ontology. Am. Ethnologist 25 (3), 412–432. doi: 10.1525/ae.1998.25.3.412