- 1Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Sciences, University of Miami, Miami, FL, United States

- 2Black Women in Ecology, Evolution, and Marine Science, Miami, FL, United States

- 3Department of Oceanography, University of Hawaii at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI, United States

- 4Duke University Marine Lab, Duke University, Beaufort, NC, United States

- 5Community Conservation, Perry Institute for Marine Science, Waitsfield, VT, United States

- 6Abess Center for Ecosystem Science & Policy, Department of Environmental Science, University of Miami, Miami, FL, United States

- 7Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada

- 8Chief Conservation Office, The Nature Conservancy, Arlington, VA, United States

- 9NOAA Oceanic and Atmospheric Research, Silver Spring, MD, United States

- 10The School for Field Studies, Center for Tropical Island Biodiversity Studies, Big Creek, Isla Colón, Bocas del Toro, Panama

Systemic racism and sexism are well documented in ecology, evolution, and marine science. To combat this, institutions are making concerted efforts to recruit more diverse people by focusing on the recruitment of Black people. However, despite these initiatives, white supremacy culture still prevails. The retention of Black people in ecology, evolution, and marine science has not increased in the ways that were hoped for. This is particularly true for Black women, who struggle to find a safe working environment that values their contributions and allows them to openly celebrate their own culture and identity. In this perspective article, we discuss the challenges that Black women face every day, and the needs of Black women to thrive in ecology, evolution, and marine science. We have written this directly to Black women and provide information on not only our challenges, but our stories. However, readers of all identities are welcome to listen and examine their role in perpetuating systemic racism and sexism. Lastly, we discuss support mechanisms for navigating ecology, evolution, and marine science spaces so that Black women can thrive.

1 Background

Since 2020 the United States has experienced a racial re-awakening due to the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and many others. Institutions have held more discussions about systemic racism, established working groups, and funded administrative departments focused on increasing diversity. In the fields of ecology, evolution, and marine science (EEMS) the lack of diversity in employees, faculty members, and students is well documented (Smith et al., 2017; Chaudhury and Colla, 2020; Miriti et al., 2020; Morales et al., 2020; Tulloch, 2020; Duc Bo Massey et al., 2021; Duffy et al., 2021; Smythe and Peele, 2021; Johri et al., 2021; Khelifa and Mahdjoub, 2022). To address this efforts and resources have been allocated to recruit more people of color (POC) and women of color (WOC), in particular Black women. However, EEMS has historically supported racist science, sexist practices, gender exclusion, and promoted elitism creating inhospitable environments for Black women, and other POC to thrive(Miriti et al., 2020), (Farinde and Lewis, 2012; Howard, 2016; McGee and Bentley, 2017; “Keeping Black Students in STEM” n.d.; Graham et al., 2022).

WSC is defined by the National Education Association (NEA) as “a form of racism centered upon the belief that white people are superior to people of other racial backgrounds and that whites should politically, economically, and socially dominate non-whites. Often associated with violence perpetrated by white supremacist groups, it also describes a political ideology and systemic oppression that perpetuates and maintains the social, political, historical, and/or industrial white domination” (NEA Center for Social Justice, n.d.). Black women in EEMS work within WSC structures rooted in hierarchies that perpetuate biases against Black women that take the form of microaggressions, racism, sexual and gender harassment.(Miriti et al., 2020; Morales et al., 2020; Callwood et al., 2022).

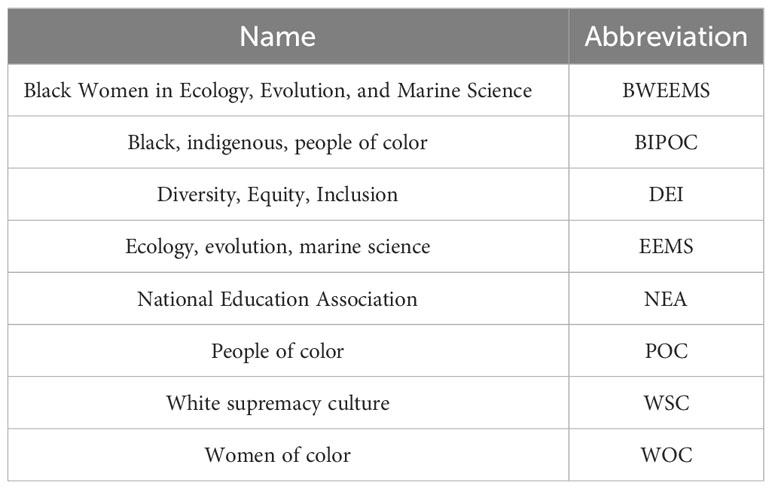

Continued disregard of Black women’s contributions to EEMS and the upholding of social structures rooted in white supremacy culture (WSC) has led to public calls to acknowledge the work and intersectional perspectives of Black women in EEMS (Miriti et al., 2020). Systemic change can only occur via the concurrent dismantling of WSC and the full recognition of the contributions of us, the Black women in EEMS (see Table 1 for acronym summary). This perspective piece offers advice for Black women attempting to navigate this system.

As Black women, we know WSC in EEMS hinders our collective ability to address major environmental crises of the time. For example, the mitigation and adaptation to the climate crisis cannot be fully realized until all groups are fully incorporated into policy processing and planning for its reversal, especially considering that Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) are disproportionately impacted by climate change (Shonkoff et al., 2011; Sarfaty et al., 2014; Frosch et al., 2018). While this should make dismantling WSC culture important to everyone, we are speaking amongst ourselves here, addressing other Black women.

1.1 The women of BWEEMS: embracing our true selves

In 2020, Black Women in Ecology, Evolution, and Marine Science (BWEEMS) was formed to facilitate a community for Black women in EEMS fields. We developed BWEEMS to help Black women navigate hostile systems entrenched in WSC by holding space for our voices, perspectives, and accomplishments. At BWEEMS, we seek to bring visibility to Black women in EEMS disciplines and support Black women in all stages of their careers. We, at BWEEMS, know that for many of us our perspective is one of privilege because of our past and current education, family (or local community) support, and financial support. Our intent with this perspective is start a conversation about the diversity of Black women in EEMS and the current needs for our success and retention.

Blackness is not one-size fits all. Indeed, the authors of this paper are of myriad, intersectional, and dynamic identities including African-American, Afro-Indigenous, Afro-Asian, Afro-Caribbean, Afro-Brazilian, Mixed-Race/Biracial Black, and Black. Each one of us has arrived at her identity via paths shaped by ancestry, skin-tone, nationality, cultural influences, and personal experience. An important juxtaposition to this self-identification is the perception of Blackness, or lack thereof, put on us by others. For example, those of us considered Black in the United States via the “one-drop rule,” which emphasizes African ancestry, may be perceived as white or “other” in countries where skin color plays a larger role in Black identity (“Mixed Race America - Who Is Black? One Nation’s Definition” n.d.; Omi and Winant, 1994; Parra et al., 2003; Telles, 2014). In a world where identity has severe consequences, it is of the utmost importance that Black women be inclusive. The challenges and solutions that we outline here are adaptable; the only hard lines we make are against WSC and all that it stands for.

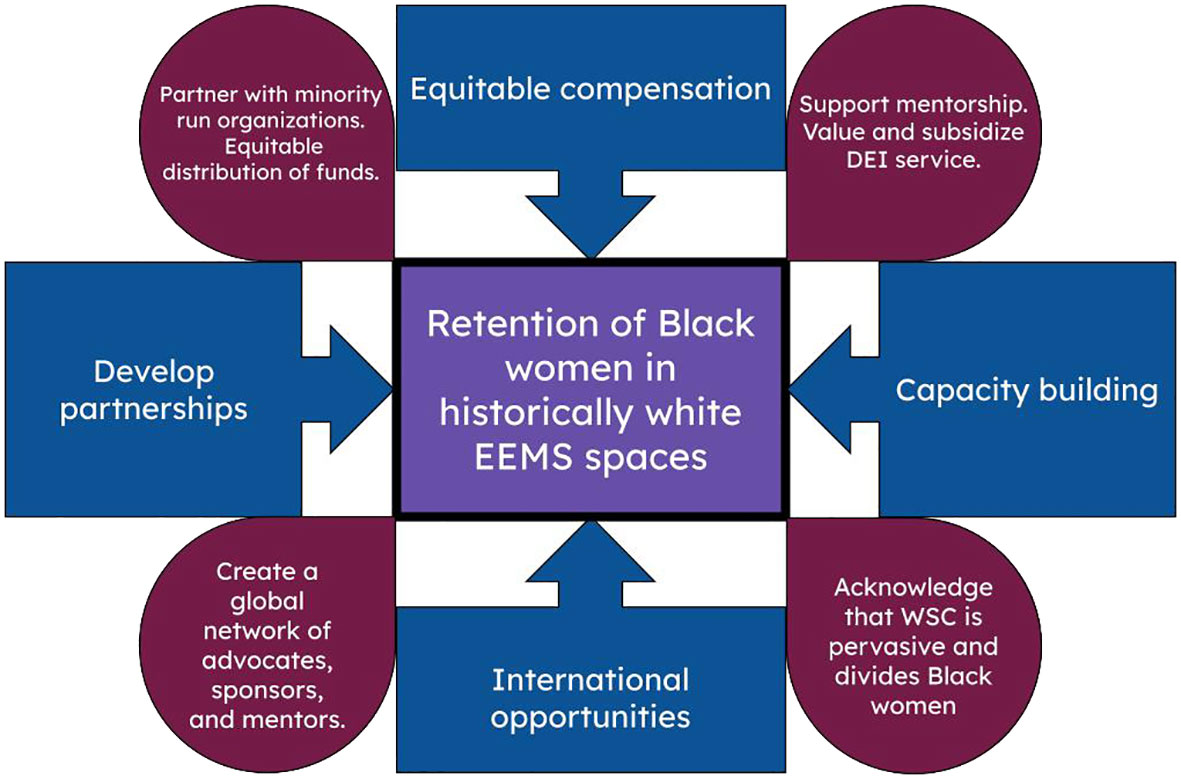

In what follows, we explore what Black women need to succeed in EEMS fields, which includes describing the destructive effects of WSC (Figure 1). Our narrative is directed toward you, fellow Black women in EEMS, who are living in WSC, with the goal of giving both context and strategies for managing your day-to-day. In each section, we discuss an overview of the problem, our experiences, and supportive mechanisms and questions to ask yourself. Lastly, Readers of other identities are welcome to listen and examine their role within WSC which persists within ecology, evolution, and marine science. We also encourage readers of other identities to read previous publications about BIPOC experiences in these spaces (Ireland et al., 2018; Sanchez et al., 2019; Schell et al., 2020; Duc Bo Massey et al., 2021).

Figure 1 A conceptual figure of how the different components mentioned in this manuscript come together to support Black women in ecology, evolution, and marine science.

2 Retention of black women in EEMS

2.1 Overview

Institutions often use recruitment and retention as metrics to evaluate diversity initiatives. However, very few put the same resources into retention as they do into recruitment, which is reflected in the data. High rates of dropout at the undergraduate and graduate level and quitting/relocating at the professional level due to toxic environments is often the norm (Ali and Kohun, n.d.; Lovitts and Nelson, 2000; Baum and Steele, 2017). For example, according to NSF, in 2018, 6751 Black women graduated with undergraduate degrees in biological, earth, atmospheric, or ocean sciences, but only 193 pursued a doctoral degree (Hamrick, n.d.).

While all women are more likely to face workplace microaggressions than their male counterparts, this is more pronounced for us (Thomas et al., 2021). To combat hostile environments and navigate the professional and scientific world, Black women may conform to the dominant culture, internally reject who they are, confront stereotypes, overachieve, and/or experience identity shifts (McGee and Bentley, 2017; Sparks, 2017; Dickens and Chavez, 2018; Morton and Parsons, 2018). However, even when employing these strategies, Black women still experience microaggressions and stereotyping (Lewis et al., 2013; Lewis and Neville, 2015; Moody and Lewis, 2019). Additionally, there often is a lack of support for Black women in the way of mentorship or apprenticeship. Mckinsey & Company’s 2021 study, Women in the Workplace, found that regardless of industry, Black women experience lack of access to senior leaders, mentorship and sponsorship and training, which ultimately leads to fewer opportunities in career advancement. All of this, rooted in WSC, has led to higher rates of attrition for Black women.

2.2 Experiences

Anecdotally, BWEEMS members have shared feelings of isolation and inadequacy and stories of daily microaggressions. These accounts replicate sentiments reported in literature documenting lost opportunities for Black scholars in STEM (Charleston et al., 2014; McGee and Bentley, 2017; Ireland et al., 2018; Sanchez et al., 2019; Bryson and Grunert Kowalske, 2022). The barriers we experience are widespread because we operate within a WSC that dictates norms and practices. Perhaps more jarring are stories of colleagues within our institutions who continue to perpetuate WSC.

Compounding these career challenges is our knowledge that Black women are expected to perform at a higher level than our white counterparts, (Wingfield and Chavez, 2020) which can lead to burnout and manifest as an imbalance in our mental health. This leads to a vicious cycle of burnout and withdrawal, thus propagating the lack of Black women within STEM careers.

2.3 Support mechanisms

2.3.1 Acknowledge and identify white supremacy culture in ecology, evolution, and marine sciences

Describing the characteristics and impacts of WSC helps to bring the underlying context of these issues to the forefront. Only by naming what we experience can we make it visible and change it (Bryant et al., 2021). Collective interrogation of the role of WSC within EEMS is key to creating accountability and bringing about transformation. For your preservation, seek information about the organizations that you are joining and ask about policies regarding hiring, firing, and promotion, and workplace culture. Do the tenets of WSC dominate this organization without any acknowledgement or desire to change? If the answer is yes, then be cautious when joining and seek outside support and guidance.

2.3.2 Ask, will this institution work to retain me?

Institutions can increase recruitment without thinking about retention, but they cannot increase retention without recruitment. For example, institutions may address both by doing cluster hires. By recruiting many Black individuals at the same time companies immediately have a peer cohort that can help create a sense of belonging and support (Tilghman et al., 2021). Does the organization actively work to create a diverse environment where you feel valued and respected? If the answer is no, then be cautious as WSC is not being acknowledged or addressed, and the environment may be hostile.

2.3.3 Ask, does this institution create space for me to thrive?

Creating a space where we Black women can be ourselves is essential for self-preservation, comfort, and rejuvenation (Mansfield, 2015; McGee and Bentley, 2017; Ong et al., 2018). Such spaces allow us to openly have conversations about our experiences in predominantly white spheres. If your institution doesn’t create a space where you can be yourself, seek one out. Your professional development and well-being need the nourishment of community support, training, mentorship, and networking that groups like BWEEMS can offer.

2.3.4 Seek diverse mentorship to support your growth

Traditional mentorship, rooted in WSC, has historically been framed as a 1 mentor: 1 mentee relationship that promotes an unsustainable power dynamic, where the mentor can act as a gatekeeper from which a mentee seeks all career and life advice. For Black women in EEMS this automatically creates an imbalance because there are few senior Black women leaders. Additionally, your needs can change with your career progression. Therefore, seeking out a diverse group of mentors who can give you access and help you navigate systems with more confidence as you seek out bigger opportunities is critical. Supportive communities, formed through mentorship, can be instrumental in growing and persisting in EEMS.

2.3.5 Support other Black women in EEMS

Positive interactions with peers, teachers, mentors, and the community at the early stages of a Black woman’s career can highly influence career trajectory and academic advancement (McGee and Bentley, 2017). Many of us who have successfully navigated EEMS got here because of support from people who opened doors, wrote recommendations, or advocated for us. Most Black women in EEMS do not see women who look like them or who have similar professional experiences. If you are in a place of power, support the rising generation of Black women through sponsorship and mentorship. We must support each other if we truly want to change this system.

2.3.6 Seek mental, physical, and emotional health support

The physical, mental, and emotional toll of working in EEMS can be detrimental to Black women’s health. Continued gaslighting, microaggressions, and other forms of racism can create anxiety, depression, and isolation. Remember that it is okay to seek out help and that you do not have to be always “resilient”. Operating in isolation and not getting support is not sustainable. Whether it is professional mental health support, religious groups, friends, family, or other organizations, do not be afraid to be vulnerable and seek out support.

3 Equitable compensation for black women in EEMS

3.1 Overview

Income inequality has detrimental impacts on life expectancy, stress levels, and overall mental and emotional health(Truesdale and Jencks, 2016) This issue disproportionately impacts Black women, as we participate in the workforce at higher rates than most other women (“Black Women & the Pay Gap”, 2020). Black women make 63 cents for every dollar a non-Hispanic white male makes, significantly lower than the 83-cent national average for women (“The Simple Truth about the Gender Pay Gap”, 2020). Despite numerous initiatives (e.g., affirmative action, cluster hires, specific job calls for marginalized applicants) to address this inequality, the problem has only become more severe. A study by the Economic Policy Institute found that the white-Black wage gap is larger today than in 2000, almost two decades ago (“Black-White Wage Gaps Are Worse Today than in 2000” n.d.; “State of Working America Wages 2019: A Story of Slow, Uneven, and Unequal Wage Growth over the Last 40 Years” n.d.).

The current hiring model in science reinforces systems of inequality. Higher education jobs are traditionally posted without a salary range, leaving most applicants in the dark. Additionally, the application process is typically lengthy, with offers and subsequent negotiations lasting months. This creates more inequity because as a candidate is waiting to be hired, time and opportunities from other potential jobs are squandered or lost.

Furthermore, EEMS heavily rely on uncompensated labor, typically called ‘service’. This type of service includes but not limited to administration, committee work, mentorship, advising, and panels. WOC disproportionately do more service than white colleagues (Social Sciences Feminist Network Research Interest Group, 2017). While service is valued as a contribution, it is oftentimes deprioritized for promotions or job searches. This leaves Black women at a clear disadvantage. We are expected to sustain and maintain productivity and do extra service yet do not get the recognition, opportunities, promotions, or monetary compensation commensurate with these efforts.

3.2 Experiences

Members of BWEEMS have experienced inequitable pay or uncompensated service expectations that are beyond those expected of their white male counterparts. For example, we are often asked to serve on DEI panels, which entails sharing personal experience. The stories we are asked to recount are often traumatic and triggering. In our opinion, these go above and beyond sharing of science and broader impacts in our community–they are personal and therefore require compensation. Additionally, lack of salary transparency and comparably low pay in EEMS for the work and education expected has led many BWEEMS members to seek employment outside of academia, where transparency in pay and growth are often more apparent.

3.3 Support mechanisms

3.3.1 Seek jobs that have transparent financial compensation

Depending on the job(s) you are applying for, the compensation may or may not be stated. Outside academia, ranges are typically given so that you can understand how the pay grade matches the education and training expected for the potential job. If you are applying for an academic job, and the pay is not stated, ask. Many public institutions will post their salary ranges publicly; however, most private institutions do not have this practice. There is no harm in asking for a pay range from the hiring committee.

3.3.2 Seek out the unwritten rules of the promotion processes

When applying to jobs, ask how the promotion or tenure (if in academia) process proceeds. Different institutions have very different expectations and structures. It is critical to get that information upfront so that you can make an informed decision. Speak with colleagues at other institutions to find out how their expectations compare to your current or future institution. Much of this information is not formally written out, but discussed verbally, so it is important to talk with people to get the information that will be most useful for you.

3.3.2 Remember that service is undervalued at promotion

Although service work should be recognized and incentivized, it is generally accepted that service is not valued equally to research output or securing grant funding during promotion or tenure processes. This presents a challenge to Black women because we are expected to do more service work, especially if we are the only Black person at an institution. Before saying yes to service committees, examine the benefits and the costs. Does this commitment require a lot of emotional energy? Will this commitment take up a lot of time without recognition? If the answer is yes, consider saying no. It is not your responsibility to address the lack of diversity or institutional problems.

4 Unity for black women in EEMS

4.1 Overview

As Black women operating in predominantly white professional spaces, we are often viewed as “other.’’ This otherness relies on the idea of whiteness as a default to personhood (Green et al., 2007), i.e., the assumption is that a person is white unless otherwise stated. This creates a power dynamic where WSC is centered, and Black women must navigate and adapt. Many Black women in STEM have reported “code-switching” in professional spaces, embracing dominant cultures within professional spaces over their more authentic self to “fit in,” increase their chances of increasing capital gains, to help protect oneself against negative stereotypes, or other forms of discrimination (Young, 2009). This coping strategy is imperfect and can be damaging (McCluney et al., 2021).

WSC also divides Black women. Skin color, hair texture, and body shape are all weaponized against Black women when beauty standards that conform to WSC expectations are valued (Dixon and Telles, 2017; Mitchell Dove, 2021). In efforts to decolonize westernized science organizations, it is of utmost importance for us to treat Black women as individuals and not as a monolith.

4.2 Experiences

In our monthly meetings at BWEEMS, we often discuss the topic of colorism. For many members, particularly BWEEMS members who identify as biracial or mixed-race, colorism has shaped their existence and is a constant source of identity stress. While light skin has historically been valued, lighter skin Black women often feel like they do not quite fit in with either Black culture or white and/or other cultures. On the other hand, darker skin Black women can experience overt racism and fear for their safety due to not being able to “blend” in with white culture. This is exemplified by members’ personal stories of having to travel with white colleagues to do field work so that they can be safe when working in predominantly white areas, for fear of getting the police called on them. These experiences highlight the challenges and dangers of WSC that Black women must navigate daily.

4.3 Support mechanisms

4.3.1 Acknowledge that WSC is pervasive and divides black women

To live in line with our ideals of embracing ourselves and transcending WSC, we must acknowledge that WSC dictates many parts of Black women’s lives. To overcome this, we must be a unified community. We must reflect on the designations of skin tone, accent, hair texture, and other physical forms that have been used to divide us. Where do you uphold WSC in your own outlook? Do you judge yourself or other Black women more harshly than you judge white people? Do you compare yourself to white ideals and wish that you could “live up to them”? If the answer is yes, this is a chance for growth and self-compassion.

4.3.2 Treat each other as individuals and acknowledge the “diversity.”

Our community is diverse, and we are united under our shared experiences as Black women. Our diversity is what makes us innovative and is a strength. Celebrating this is an important step forward in dismantling WSC and building a culture that prioritizes our health and happiness.

We do not need to assimilate or deny who we are, the Black woman identity is varied. If we can understand this as a group, then we can continue to work together towards our progression, rather than having to focus on assimilation into any specific space. Your identity is what makes you unique and WSC cannot erase that.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

NT-K: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ABDS: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AB: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KC: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AD: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GH: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. VM: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CS: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. NSF Grant # 2116697, Schmidt Foundation Ocean Coalition Award , The Builders Initiative and OceanKind.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the members of BWEEMS for their strength and persistence. The authors would also like to thank the reviewers for their time and feedback. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Katherine Fusco for her edits and feedback. Lastly, the authors would like to acknowledge their ancestors for surviving and giving them the courage, fortitude, and privilege to be here now.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer, CK, declared a past co-authorship with the author, NT-K.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ali A., Kohun F. (n.d.). Dealing with isolation feelings in IS doctoral programs. Int. J. Doctoral Stud. 1, 21–33. doi: 10.28945/2978

(n.d.) Black-White Wage Gaps Are Worse Today than in 2000 (Economic Policy Institute). Available at: https://www.epi.org/blog/black-white-wage-gaps-are-worse-today-than-in-2000/ (Accessed April 8, 2022).

(2020). Black Women & the Pay Gap (AAUW: Empowering Women Since 1881). Available at: https://www.aauw.org/resources/article/black-women-and-the-pay-gap/.

(2020). The Simple Truth about the Gender Pay Gap (AAUW: Empowering Women Since 1881). Available at: https://www.aauw.org/resources/research/simple-truth/.

Baum S., Steele P. (2017). Who Goes to Graduate School and Who Succeeds? (AccessLex Institute Research Paper No. 17-01). doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2898458

Bryant J., Cohen-Stratyner B., Mann S., Williams L. (2021). The White Supremacy Elephant in the Room. Available at: https://www.aam-us.org/2021/01/01/the-white-supremacy-elephant-in-the-room/.

Bryson T. C., Grunert Kowalske M. (2022). Black women in STEM graduate programs: the advisor selection process and the perception of the advisor/advisee relationship. J. Diversity Higher Educ. 15 (1), 111–235. doi: 10.1037/dhe0000330

Callwood K. A., Weiss M., Hendricks R., Taylor T. G. (2022). Acknowledging and supplanting white supremacy culture in science communication and STEM: the role of science communication trainers. Front. Commun. 7. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.787750

Charleston L. J., George P. L., Jackson J. F. L. (2014). Navigating underrepresented STEM spaces: experiences of black women in US computing science higher education programs who actualize success. Higher Educ. 7 (3), 166–176. doi: 10.1037/a0036632

Chaudhury A., Colla S. (2020). Next steps in dismantling discrimination: lessons from ecology and conservation science. Conserv. Lett. 14, e12774. doi: 10.1111/conl.12774

Davis F. J. (n.d.) Mixed Race America - Who Is Black? One Nation’s Definition. Available at: https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/jefferson/mixed/onedrop.html (Accessed April 8, 2022).

Dickens D. D., Chavez E. L. (2018). Navigating the Workplace: The Costs and Benefits of Shifting Identities at Work among Early Career U.S. Black Women. Sex Roles 78 (11-12), 760–774. doi: 10.1007/s11199-017-0844-x

Dixon A. R., Telles E. E. (2017). Skin color and colorism: global research, concepts, and measurement. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 43 (1), 405–245. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-060116-053315

Duc Bo Massey M., Arif S., Albury C., Cluney V. A. (2021). Ecology and evolutionary biology must elevate BIPOC scholars. Ecol. Lett. 24 (5), 913–195. doi: 10.1111/ele.13716

Duffy M. A., García-Robledo C., Gordon S. P., Grant N. A., Green D. A. 2nd, Kamath A., et al. (2021). Model systems in ecology, evolution, and behavior: A call for diversity in our model systems and discipline. Am. Nat. 198 (1), 53–685. doi: 10.1086/714574

Farinde A. A., Lewis C. (2012). The Underrepresentation of African American Female Students in STEM Fields: Implications for Classroom Teachers. Available at: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/0f4fa5e113b30d08c53aa463f023c52c0e62920f.

Frosch, Pastor, Sadd (2018). The climate gap: inequalities in how climate change hurts Americans and how to close the gap. For Climate Change 13. doi: 10.4324/9781351201117

Gould E. (n.d.) State of Working America Wages 2019: A Story of Slow, Uneven, and Unequal Wage Growth over the Last 40 Years (Economic Policy Institute). Available at: https://www.epi.org/publication/swa-wages-2019/ (Accessed April 8, 2022).

Graham J., Hodsdon G., Busse A., Crosby M. P. (2022). BIPOC voices in ocean sciences: A qualitative exploration of factors impacting career retention. J. Geosci. Educ. 3, 369–387. doi: 10.1080/10899995.2022.2052553

Green M. J., Sonn C. C., Matsebula J. (2007). Reviewing whiteness: theory, research, and possibilities. South Afr. J. Psychol. = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif Vir Sielkunde 37 (3), 389–4195. doi: 10.1177/008124630703700301

Hamrick K. (n.d.) Women, Minorities, and Persons with Disabilities in Science and Engineering: 2021. Available at: https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf21321/report (Accessed September 1, 2022).

Howard T. S. (2016) The under-Representation of African American Women in the STEM Fields within the Academy: A Historical Profile and Current Perceptions. Available at: https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2016PhDT........50H.

Ireland D. T., Freeman K. E., Winston-Proctor C. E., DeLaine K. D., Lowe S. M., Woodson K. M. (2018). (Un)hidden figures: A synthesis of research examining the intersectional experiences of black women and girls in STEM education. Rev. Res. Educ. 42 (1), 226–545. doi: 10.3102/0091732X18759072

Johri S., Carnevale M., Porter L., Zivian A., Kourantidou M., Meyer E. L., et al (2021). Pathways to justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion in marine science and conservation. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 696180. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.696180

Khelifa R., Mahdjoub H. (2022). Integrate geographic scales in equity, diversity and inclusion. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 6 (1), 4–55. doi: 10.1038/s41559-021-01609-7

Lewis J. A., Mendenhall R., Harwood S. A., Huntt M. B. (2013). Coping with gendered racial microaggressions among black women college students. J. Afr. Am. Stud. 17 (1), 51–735. doi: 10.1007/s12111-012-9219-0

Lewis J. A., Neville H. A. (2015). Construction and initial validation of the gendered racial microaggressions scale for black women. J. Couns. Psychol. 62 (2), 289–302. doi: 10.1037/cou0000062

Lovitts B. E., Nelson C. (2000). The hidden crisis in graduate education: attrition from Ph.D. Programs. Academe 86 (6), 44–505. doi: 10.2307/40251951

Mansfield K. C. (2015). The importance of safe space and student voice in schools that serve minoritized learners. J. Educ. Leadership Policy Pract. 30 (1), 25–38. doi: 10.21307/jelpp-2015-004

McCluney C. L., Durkee M. I., Smith R. E. II, Robotham K. J., Lee S. S.-L. (2021). To be, or not to be … Black: the effects of racial codeswitching on perceived professionalism in the workplace. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 97 (104199), 1041995. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2021.104199

McGee E. O., Bentley L. (2017). The troubled success of black women in STEM. Cogn. Instruction 35 (4), 265–895. doi: 10.1080/07370008.2017.1355211

Miriti M. N., Bailey K., Halsey S. J., Harris N. C. (2020). Hidden figures in ecology and evolution. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4 (10), 1282. doi: 10.1038/s41559-020-1270-y

Mitchell Dove L. (2021). The influence of colorism on the hair experiences of African American female adolescents. Genealogy 5 (1), 5. doi: 10.3390/genealogy5010005

Moody A. T., Lewis J. A. (2019). Gendered racial microaggressions and traumatic stress symptoms among black women. Psychol. Women Q. 43 (2), 201–145. doi: 10.1177/0361684319828288

Morales N., O’Connell K. B., McNulty S., Berkowitz A., Bowser G., Giamellaro M., et al. (2020). Promoting inclusion in ecological field experiences: examining and overcoming barriers to a professional rite of passage. Bull. Ecol. Soc. America 101 (4), 1–n/a. doi: 10.1002/bes2.1742

Morton T. R., Parsons E. C. (2018). #BlackGirlMagic: the identity conceptualization of black women in undergraduate STEM education. Sci. Educ. 102 (6), 1363–1935. doi: 10.1002/sce.21477

NEA Center for Social Justice (n.d.) White Supremacy Culture Resources. Available at: https://www.nea.org/resource-library/white-supremacy-culture-resources (Accessed April 8, 2022).

Omi M., Winant H. (1994). Racial Formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1990s (New York: Routledge).

Ong M., Smith J. M., Ko L. T. (2018). Counterspaces for women of color in STEM higher education: marginal and central spaces for persistence and success. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 55 (2), 206–455. doi: 10.1002/tea.21417

Parra F. C., Amado R. C., Lambertucci J. R., Rocha J., Antunes C. M., Pena S. D. J. (2003). Color and genomic ancestry in Brazilians. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100 (1), 177–182. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0126614100

Sanchez M. E., Hypolite L. I., Newman C. B. (2019). Black women in STEM: the need for intersectional supports in professional conference spaces. J. Negro Educ. 88 (3), 297–310. doi: 10.7709/jnegroeducation.88.3.0297

Sarfaty M., Mitchell M., Bloodhart B., Maibach E. W. (2014). A survey of African American physicians on the health effects of climate change. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 11 (12), 12473–12855. doi: 10.3390/ijerph111212473

Schell C. J., Guy C., Shelton D. S., Campbell-Staton S. C., Sealey B. A., Lee D. N., et al. (2020). Recreating wakanda by promoting black excellence in ecology and evolution. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4 (10), 1285–1875. doi: 10.1038/s41559-020-1266-7

Shonkoff S. B., Morello-Frosch R., Pastor M., Sadd J. (2011). The climate gap: environmental health and equity implications of climate change and mitigation policies in California—a review of the literature. Climatic Change 109 (1), 485–5035. doi: 10.1007/s10584-011-0310-7

Smith N. S., Côté I. M., Martinez-Estevez L., Hind-Ozan E. J., Quiros A. L., Johnson N., et al. (2017). Diversity and inclusion in conservation: A proposal for a marine diversity network. Front. Mar. Sci. 4. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2017.00234

Smythe W. F., Peele S. (2021). The (un)discovering of ecology by Alaska native ecologists. Ecol. Appl. 31 (6), e02354. doi: 10.1002/eap.2354

Social Sciences Feminist Network Research Interest Group (2017). Social inequalities and time use in five university departments. Humboldt J. Soc. Relations 39, 228–245. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/90007882.

Sparks D. M. (2017). Navigating STEM-worlds: applying a lens of intersectionality to the career identity development of underrepresented female students of color. J. Multicultural Educ. 11 (3), 162–175. doi: 10.1108/JME-12-2015-0049

Suran M. (n.d.) Keeping Black Students in STEM (PNAS). Available at: https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.2108401118 (Accessed April 8, 2022).

Telles E. E. (2014). Race in Another America: The Significance of Skin Color in Brazil (New Jersey, United States: Princeton University Press).

Thomas R., Cooper M., Urban K. (2021). Women in the Workplace 2021 (McKinsey and Company). Available at: https://www.voced.edu.au/content/ngv:91766.

Tilghman S., Alberts B., Colón-Ramos D., Dzirasa K., Kimble J., Varmus H. (2021). Concrete steps to diversify the scientific workforce. Science 372 (6538), 133–135. doi: 10.1126/science.abf9679

Truesdale B. C., Jencks C. (2016). The health effects of income inequality: averages and disparities. Annu. Rev. Public Health 37 (January), 413–430. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032315-021606

Tulloch A. I.T. (2020). Improving sex and gender identity equity and inclusion at conservation and ecology conferences. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4 (10), 1311–1320. doi: 10.1038/s41559-020-1255-x

Wingfield A. H., Chavez K. (2020). Getting in, getting hired, getting sideways looks: organizational hierarchy and perceptions of racial discrimination. Am. Sociological Rev. 85 (1), 31–575. doi: 10.1177/0003122419894335

Keywords: black women, ecology, evolution, marine science, white supremacy culture

Citation: Traylor-Knowles N, Bedi de Silva A, Boyd AD, Callwood KA, Davis ACD, Hall G, Moreno V and Scott CP (2023) Experiences of and support for black women in ecology, evolution, and marine science. Front. Mar. Sci. 10:1295931. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1295931

Received: 17 September 2023; Accepted: 16 November 2023;

Published: 14 December 2023.

Edited by:

Eugenia Zandonà, Rio de Janeiro State University, BrazilReviewed by:

Carly Kenkel, University of Southern California, United StatesJuliana S. Leal, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia (UFRJ), Brazil

Copyright © 2023 Traylor-Knowles, Bedi de Silva, Boyd, Callwood, Davis, Hall, Moreno and Scott. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nikki Traylor-Knowles, bnRrMTcxN0BnbWFpbC5jb20=

Nikki Traylor-Knowles

Nikki Traylor-Knowles Anamica Bedi de Silva

Anamica Bedi de Silva Anjali D. Boyd2,4

Anjali D. Boyd2,4