- School of Law, Jinan University, Guangzhou, China

Increasing plastic pollution is looming worldwide, damaging biodiversity, marine ecosystems, and human health. At the global level, no overarching normative framework sets out the specific rules and principles of general application in international environmental law, leading to difficulties in compliance and enforcement of plastic pollution governance. Developing an effective and legally binding instrument to tackle this emerging issue is imperative. The United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) has called for developing an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment, based on plastic’s full lifecycle approach. As one of the active participants in the negotiations, the European Union (EU) has discussed various aspects of the instrument in detail and sought to introduce the EU governance experience at the international level. This article develops a framework that considers contextual, actor, and process factors to assess the extent of achieving EU targets. On this basis, we argue that the EU’s objectives for the international instrument may be achieved at a high level. However, how the EU responds to challenges will also impact subsequent development, which may require the EU to adopt a more moderate stance and compromise on some controversial issues.

1 Introduction

The impacts of plastic pollution are becoming increasingly palpable – forcing ecosystems to reduce their ability to adapt to climate change, threatening people’s livelihoods, food production capabilities and social well-being, and the health of humans and other living organisms (UNEP, 2022a; Varvastian, 2023). It is estimated that between 1.15 and 2.41 million tons of plastic waste enters the ocean every year from rivers (Lebreton et al., 2017). Plastics account for at least 85 percent of marine waste (UNEP, 2022a). The mismanagement of plastic waste on shorelines and at the sea surface from pole to pole has damaged the entire marine environment (Woodall et al., 2014). The worldwide community should be aware of the urgent global issue since it will unavoidably cause harm to all nations directly and indirectly (Nellyana et al., 2023).

United Nations (UN) mechanisms played an increasingly important role in making the environmental concerns genuinely global from Stockholm to Paris, notably the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (Kumar, 2020; Chen and Xu, 2022b). According to the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) resolution 5/14, it is required that the executive Director should convene an Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) to develop an internationally legally binding instrument1 on plastic pollution, including marine plastic pollution, henceforth referred to as “the instrument,” which could include both binding and voluntary approaches, based on a comprehensive approach that addresses the full lifecycle2 of plastics (UNEP, 2022c; UNEP, 2023a). In September 2023, the essential “Zero Draft” 3was launched with an alternative scenario for an overall target year of 2040. The revised version, including most of the proposed text submissions from global actors, will be discussed in April 2024 (Xu et al., 2023; IISD, 2023a).

As the INC meetings progressed, discussions in the academic literature increased proportionately. Some studies emphasize the need for an instrument that could fill the regulatory and governance gaps in international environmental law and provide concrete recommendations for a solid and effective agreement and the interaction between the instrument and other agreements, such as the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) (Beltran et al., 2023; Vidar et al., 2023; Mendenhall, 2023a, b). Some discuss the fundamental elements of this instrument (Wang, 2023), while others analyze the main drivers behind the global wave of plastic pollution cases and the prospect of plastic treaty negotiations (Stöfen-O’Brien, 2022).

The European Union (EU), as one of the most active global negotiation actors, promotes and implements ambitious environmental policies worldwide (European Commission, 2019b). The EU’s foreign policy agenda and the forward-looking European strategy on plastics (2018) show its ambition and leadership on global marine litter by shifting waste leakage from a linear model to a circular one (Penca, 2018; Iverson, 2019). The EU has enforced the directives to reduce the impact of certain plastic products on the environment (Da Costa et al., 2020). It also develops a more robust “green deal diplomacy” focused on convincing and supporting others to take on their share of promoting more sustainable development (European Commission, 2019b).

Despite the research on the instrument and the EU’s plastic governance already validated in the literature, this article provides a more comprehensive analysis. Through theoretical and practical discussion on the EU’s participation in negotiations of the global plastic pollution instrument under international environmental, we predict the extent to which EU policy objectives are reflected in the outcome of the international negotiations and shed new light on how the EU will contribute to the negotiation of the instrument. We developed a comprehensive assessment framework to guide our analysis. We distinguish here four categories of factors related to (1) global ocean governance and pollution control, (2) the EU’s leadership role in the governance of plastic pollution, (3) the EU’s positions on the instrument elements during INC meetings, (4) the EU’s diplomacy strategy during the negotiations. Finally, we summarize the findings and analyze the challenges and outlook of the EU’s future participation in the plastic pollution instrument.

2 Global ocean governance and pollution control

This section reviews and analyzes the framework of the existing international agreements and international political efforts on plastic pollution, as well as the governance gaps and deficiencies that impede the current efforts to address the issue.

2.1 The existing international agreements and international political efforts

As a branch of international law, international environmental law addresses States and international organizations concerning protecting the environment. Global plastic pollution governance represents a multidimensional governance landscape at international, regional, and national levels (Wysocki and Billon, 2019), with UNCLOS as the core, formal binding legal forms such as environment-related international conventions, agreements, and protocols as the mainstay, and international political efforts as the complement.

The Stockholm Declaration (1972) was one of the first attempts to get States to agree on environmental protection goals (Fritz, 2020) as the conceptual cornerstone to shape five decades of environmental action. Principle 74 was further supported by the Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter (The London Convention of 1972), which regulates the dumping of waste at sea at a global level. Annex V of the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships 1973 (MARPOL) is the complete ban imposed on the disposal into the sea of all plastics (Wysocki and Billon, 2019). Further, the 1982 United Nations Law of the Sea Convention (UNCLOS) provides general obligations to prevent or to reduce marine pollution from land- and ocean-based sources through domestic laws (Wang, 2023). The UNCLOS defines “pollution of the marine environment” 5 in Article 1 and regulates related aspects in other articles.6 However, the framework is rather general, and there are no concrete solutions to address the full lifecycle of plastic and prevent ongoing marine plastic pollution (Raubenheimer et al., 2018; Nagtzaam, 2023). Other binding international instruments also address specific issues of plastic wastes, such as the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes (1989) and the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (2004) (Wysocki and Billon, 2019). The Basel Convention (1989) aims to protect human health and the environment by reducing waste at the source and disposing of hazardous waste in an environmentally sound manner (Guggisberg, 2024). Its amendment in 2019 further strengthened the regulation of transboundary movements of plastic waste, minimizing the potential for new plastic pollution of the oceans. The Stockholm Convention (2004) addressed persistent organic pollutants and was a new milestone in the international community’s response to plastic pollution (Hagen and Walls, 2005).

Since marine environmental matters differ from region to region, implementing differentiated regional legal regimes for protecting the environment is a viable option where global laws cannot be applied uniformly to specific marine areas. At the level of regional regulations, significant agreements such as the Convention on the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Baltic Sea Area (1974), the Convention for the Protection of the Mediterranean Sea against Pollution (1976), and the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (1992), exist to address these concerns. Although the scope of application of these regional action plans or mechanisms varies, the proliferation of relevant international instruments and improved cooperation and coordination among regions enormously fortified the legal foundation for preventing and controlling marine microplastic pollution.

International political efforts have played a complementary role in global governance. In addition to The Stockholm Declaration (1972) mentioned above, the Global Program of Action to Protect the Marine Environment from Land-Based Activities (1995) and the Honolulu Strategy (2012) provided a guiding framework for action to combat plastic pollution (UNEP, 2012). The five resolutions of the UN Environmental Assembly on plastic waste and microplastics in the sea after 2014 signaled the beginning of concrete measures by the international community against plastic waste in the sea (IISD, 2021). Furthermore, regional and global political initiatives also operate voluntarily without a legally binding nature, such as the G20 Implementation Framework for Action on Marine Plastic Litter (2017), the Ocean Plastic Charter (2018), and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Framework of Action on Marine Debris (2019) (Wang, 2023).

2.2 Governance gaps and deficiencies

In this section, “gaps” refers to implementation gaps in the international legal framework and substantive/normative gaps (including procedural and institutional gaps (UNEP, 2018b). While there are comprehensive international legal frameworks to regulate marine plastic pollution at global and regional levels, the amount of plastic waste continues to increase, and plastic continues to leak into rivers and oceans (Wysocki and Billon, 2019; Nagtzaam, 2023).

Current regulations need to be revised to address plastic pollution’s damage effectively. First, legally binding international instruments are primarily directed at the oceans and are less concerned with land-based sources of pollution. Second, the resource-inefficient and linear plastics economy is the biggest culprit in the plastic pollution crisis (Fritz, 2020). Only a tiny fraction of plastics can be recycled from raw plastic production to waste and spills. Third, The emerging plastics governance regime only contains “downstream” (Mendenhall, 2023a) while not offering any solutions to the “upstream” production of plastic as a cause of marine plastic pollution (Nagtzaam, 2023).

Moreover, principles of general international law can also govern matters if the convention does not regulate them. No overarching normative framework sets out the concrete rules and principles of general application in international environmental law (UNEP, 2018b). These principles of the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development (1992) deserve attention, such as precaution7, polluter pay 8and common but differentiated responsibilities9. However, not all principles are well-recognized through international instruments and international courts. The principle of not being content-wise, status-wise, and having a lack of clarity makes it hard to reach a global consensus.

The current piecemeal and reactive framework led to a deficit in coordination at the legislation and implementation level due to the lack of coherence and synergy (UNEP, 2018b). The gaps between states should also be considered regarding financial resources, environmentally sound technologies, and capacities, which contribute to the implementation at the national and international levels. States and the United Nations should work together to address the gaps and deficiencies. Therefore, It is necessary to develop an internationally legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including marine plastic pollution, with the clarification and reinforcement of regulations and principles, the international legally binding force, and robust compliance and enforcement procedures to ensure effective implementation of States’ commitments.

3 EU’s leadership role in the governance of plastic pollution

An actor is qualified as a leader in global governance because it has more ambitions than others in pursuing the common good (Oberthür and Dupont, 2021). In past environmental negotiations and issues, the EU, as a critical contributor to advancing and revising global and regional conventions while amassing considerable negotiation experience, has been found to exert leadership with varying degrees of success (Kilian and Elgstrom, 2010; Bäckstrand and Elgström, 2013; Iverson, 2019; Oberthür and Dupont, 2021). To assess the EU’s ambition in plastic pollution governance, we first put the analytical effort on the EU’s participation in previous international negotiations as the basis for understanding EU marine plastic pollution governance stances. Then, we analyze the EU’s policies and legislation to assess whether they could significantly shape and condition EU leadership.

3.1 Positive actor in international marine plastic pollution governance

The EU Integrated Maritime Policy (2007) extensively delineates the future vision and planning for ocean utilization and protection. It highlights the EU’s crucial role in regional and global ocean governance, signifying the externalization of the EU’s maritime policy. Following this, the EU has actively participated in extraterritorial maritime affairs and promoted European programs globally (European Commission, 2008b). As a role model in environmental protection for its effective path for eliminating marine plastic pollution, the EU has transposed international agreements into its internal legal order through legislation and policies. After the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) issued the first resolution on marine litter emphasizing the urgency to take concrete action (UNEP, 2014), the EU initiated the Marine Safety Strategy (2014), followed by the adoption of the EU Action Plan for the Circular Economy (2015). In 2016, the EU presented its first global ocean governance strategy (European Commission, 2016), suggesting taking marine plastic litter as one of the 50 actions of international ocean governance. Along with the UNEP resolution 3/7 on marine litter and microplastic (2018), the EU adopted the European strategy (2018) for plastics, which highlighted the need to harness global action on plastic (European Commission, 2018) and embraced A new Circular Economy Action Plan (2020), underscoring the global plastic agreement as a global priority (European Commission, 2020).

The EU has contributed to integrating the global plastic waste governance system. Primarily, the EU actively engages in revising established conventions, such as being the vocal and active supporter of the Basel amendments (Environmental Investigation Agency, 2019). Another aspect is to strengthen international cooperation on marine research and data. The European Commission confirmed its commitment to improved ocean governance in the recent Joint communication on the EU’s International Ocean Governance agenda (2022) to build international ocean knowledge for evidence-based decision-making that leads to actions to protect and sustainably manage the ocean, which requires promoting marine research, data, and science to develop comprehensive, reliable, comparable, and accessible knowledge about the oceans (Dañobeitia et al., 2023). Funded by the European Commission (EC), the Copernicus Maritime Service Center provides a comprehensive, scientifically assessed, and regularly updated product portfolio to understand how plastic pollution spreads and reliable inputs for specific plastic applications with free and open access to all stakeholders (Copernicus Marine Service, 2017, 2020). In addition, the EU also provided funding for research and innovation work, such as Horizon 2020, which was succeeded by Horizon Europe. Some programs focus on tackling the problem of marine plastic waste by tracking the amount of plastic in the sea and producing high-quality products from marine plastic waste (European Union External Action, 2021).

3.2 Addressing the gap: EU internal plastic pollution policies and legislation

We include the EU’s internal policies and legislation as one of the factors in assessing its leadership, which underpins the EU’s ambitions. First, the EU has an elaborate policy framework to face the governance of plastic pollution. Critical decisions on the ambition of EU policies have regularly been taken in the context of specific policies. Additionally, almost 26 million tons of plastic waste are generated annually in Europe, and land-based sources represent nearly 80% of plastic inputs to the ocean (Lavers and Bond, 2017; European Commission, 2023b). Therefore, its policies on significant plastic consumption and production can substantially impact the worldwide plastic lifecycle (Eckert et al., 2024). As a framework policy to address the challenges, the European Commission officially launched the European Strategy for Plastics in a Circular Economy (2018) to ensure that plastic materials last longer, can be collected more easily after use, and can be reused or recycled more easily (European Commission, 2018). The transition to higher recycled plastics in Europe increases significantly between 2018 and 2022. The content of recycled plastics in new products reached a new record high of 13.5%. Compared with the nearly 15% European plastics recycling rate in 2018 (with almost 62 million tonnes plastics production and 9.4 million tonnes recycling), it has increased to 26.9% in 2022. It remarks as a crucial circularity milestone and stands as a model for other actors (Plastics Europe, 2019; Plastics Europe, 2024).

The Marine Strategy Framework Directive (2008) is a critical horizontal legislative pillar, providing a cross-sector framework covering all the primary pollution sources. It shows a new approach to EU environmental policy, in which different polluters and sources of pollution are not addressed independently but integrated into a comprehensive legal act. The regulatory framework for marine plastic pollution ranges from water and marine policy to waste and product policy to measures under the common fisheries policy.

In the upstream phase, most monomers used to make plastics, such as ethylene and propylene, are derived from fossil hydrocarbons. None of the commonly used plastics are biodegradable. As sunlight and other elements degrade plastics, they break into thousands of tiny pieces called microplastics, accumulating in the environment and polluting marine ecosystems, causing environmental degradation and health problems for humans and animals alike (Earth Day, 2023). The EU is taking bioplastics as a possible alternative to plastic packaging. There isn’t a comprehensive EU legislation but a non-legal binding policy framework on sourcing, labeling, and using biobased biodegradable and compostable plastics (European Commission, 2023a), and the European Commission adopted a REACH restriction (2023) on microplastics intentionally added to products. In the midstream, the EU Plastic Bags Directive (2015) addresses the unsustainable consumption and use of lightweight plastic carrier bags through consumption limitation (European Commission, 2015). Directives on single-use plastics (2019) aim to reduce the volume and impact of certain plastic products on the environment and introduce waste management and clean-up obligations for producers, including Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) schemes (European Commission, 2019a). EU rules on packaging and packaging waste cover both packaging design and packaging waste management and set additional waste prevention and reuse obligations for EU countries and packaging EPR schemes (European Commission, 1994). In the downstream, the EU launched the Waste Framework Directive (2008) in response to challenges associated with illegal dumping and insufficient downstream waste management (European Commission, 2008a). This policy strives to decrease waste generation at its source by enhancing product design and advocating for the recycling and reuse of waste. The Polluter Pays Principle is a fundamental guiding principle in achieving this objective, ensuring that product manufacturers assume the costs of combating environmental pollution.

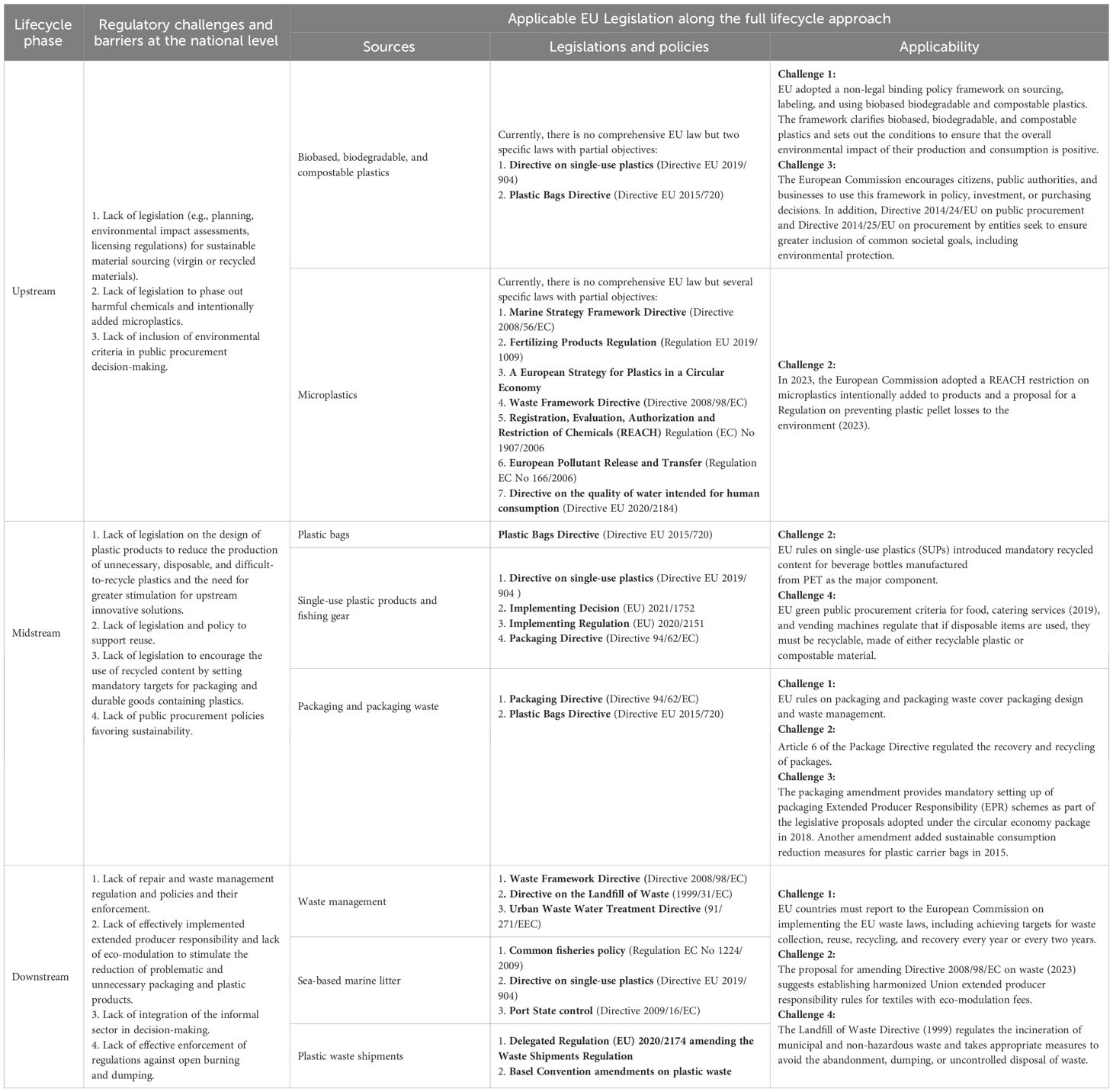

Additionally, measures have been taken to establish a fisheries management regulation (2009), which requires marking fishing gear and recovering fishing gear when fishermen unintentionally lose or intentionally discard fishing in the sea (European Council, 2009). The EU is also grappling with downstream shipments of plastic waste through Delegated Regulation (EU) 2020/2174 amending the Waste Shipments Regulation, which establishes different entries for the classification of hazardous, non-hazardous, or special plastic waste to be taken into account has been changed, ending the export of plastic waste to third countries that lack the capacity and standards for sustainable disposal. To better understand the EU legislation, we compare the national-level regulatory challenges identified by UNEP (UNEP, 2022b) with the EU legislation10 in (Table 1).

(The two leftmost columns of Table 1 are based on UNEP/PP/INC.1/11-Priorities, needs, challenges, and barriers to ending plastic pollution at the national level (UNEP, 2022b). We have compiled the legislation and policies from the official website of the European Union and analyzed how they could address the regulatory challenges and barriers at the national level.)

The EU has generally established a relatively comprehensive system to prevent and control marine plastic pollution through policies and legislation. It could address the regulatory challenges and barriers at the national level. However, EU legislation still has limitations in the full lifecycle approach (Steensgaard et al., 2017). Many measures focus on downstream activities (Milios, 2018), while only a non-legally binding framework is effective at the upstream stage to reduce the overall consumption of primary fossil-based materials. Policy action mostly leaves the upstream material input stage unaddressed (Eckert et al., 2024). The downstream limiting the number of plastics currently disposed of in landfills, which could further optimize resource efficiency, still needs to be regulated in the EU (Steensgaard et al., 2017). In addition, the EU has yet to give a specific response to the lack of integration in the informal waste sector.

In summary, we argue that the EU has played a leading role in international marine plastic pollution governance. It has actively participated in developing relevant international instruments and shared free and open-access knowledge, providing technical support and financial backing for innovation and development. It also transposed international agreements into its internal legal order through legislation and policies. The EU legislation and policies could address the most challenges at the national level, which underpins the feasibility of pursuing EU goals at the international level. However, the EU must focus on improving policy and legislation at each life cycle stage and increase regulation and enforcement if it wants to gain leadership in global governance.

4 The EU’s positions on the instrument elements during INC meetings

Ahead of the negotiations, the European Commission issued a justification for the EU’s participation in the negotiations on an international agreement on plastic pollution, ensuring that the EU’s positions in the instrument are consistent with existing EU policy provisions, which suggested that the agreement should be based on the precautionary principle, the polluter pays principle, and source government (European Commission, 2022b). As discussed earlier, the EU’s position in the instrument negotiations will likely continue the EU’s policy and legislative preferences. However, it also depends on whether the EU pursues conservatism to stick to its goals in the negotiations or adopts reformism to compromise. The following section discusses the EU’s positions on the more controversial elements of the instrument and analyzes the opinions through international environmental law.

4.1 Principles of the instrument

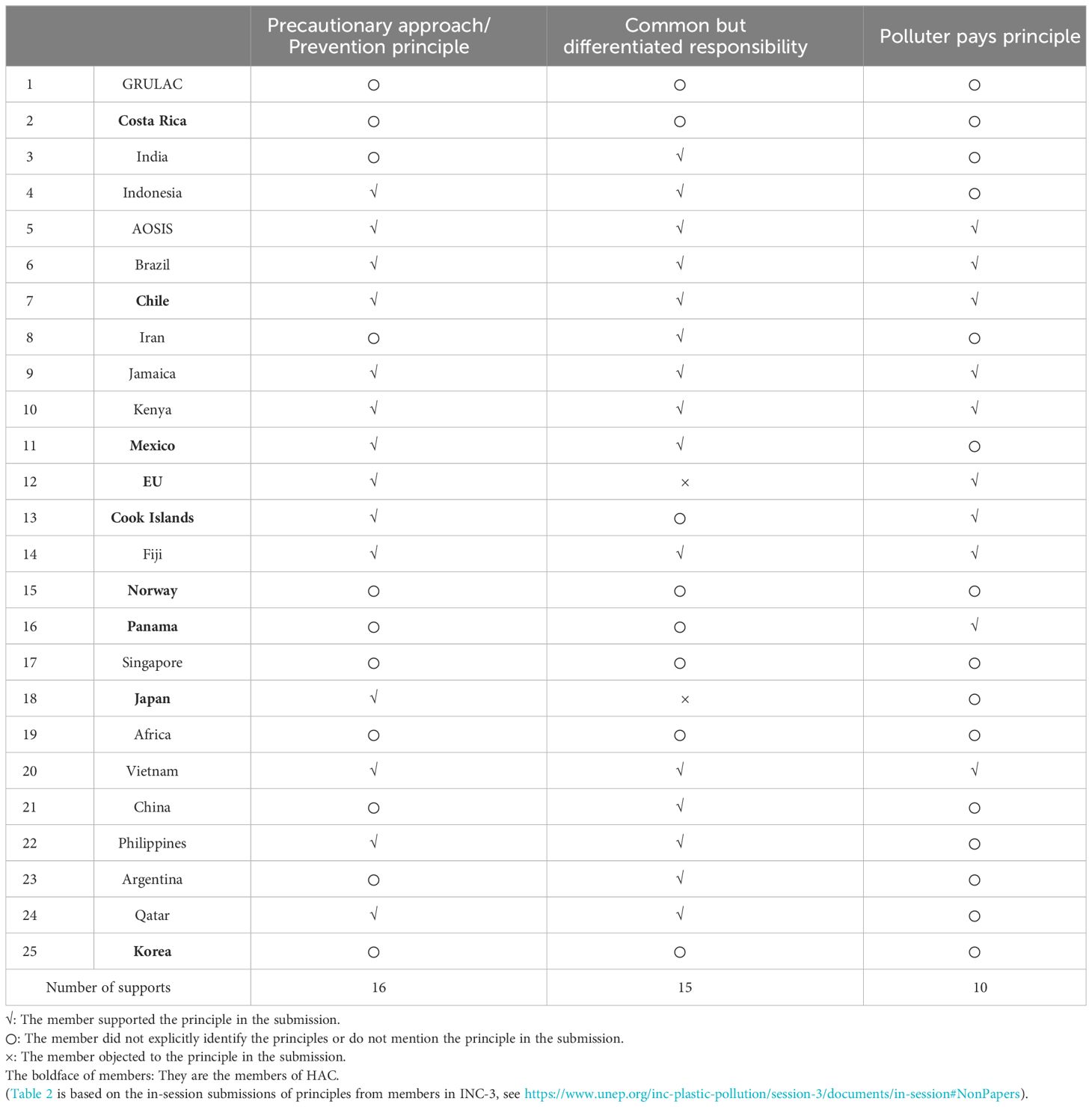

According to the requirements mentioned in resolution 5/14, the instrument should be based on the principles of the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, as well as national circumstances and capabilities. In the third session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC-3) contact group 3 In-session Submissions, 25 countries submitted written comments on the principles. According to Table 2, the principles that received high support are the precautionary principle/precautionary approach, the common but differentiated responsibility, and the polluter pays principle11. It is worth noting that there is a wide divergence of views on the precautionary principle and common but differentiated responsibilities. The position of the EU and the majority of HAC members remains consistent in favor of the precautionary principle and the polluter pays principle. It is also worth noting that the positions of China, Iran, and India on these three principles are the same, stressing the importance of the common but differentiated responsibility. The EU’s positions on the precautionary principle, common but differentiated responsibilities, and the polluter pays principle will be scrutinized below.

4.1.1 The precautionary principle

At the international level, the definition of the precautionary principle in Rio Declaration Principle 15 of 1992 is widely accepted. The precautionary principle is enshrined in many previous plastic pollution control instruments. International organizations and conference resolutions have also contributed to developing the precautionary principle. The 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, regarded as a landmark in national environmental law, further strengthened the precautionary principle in the Rio Declaration and Agenda 21 (UNGA, 1992). In numerous cases, plaintiffs have frequently invoked the precautionary principle, but the International Court of Justice has not responded positively (ICJ, 1996, 1997, 2010).

Through a series of laws, policy documents, and extensive application, the precautionary principle has evolved into the foundation for policy formulation and implementation within the EU. Article 191 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (1958) states that union policy on the environment should be based on the precautionary principle. The environmental damage should be a priority rectified at the source, and the polluter should pay. In addition, the precautionary principle remains a fundamental tenet of successive EU environmental action plans and substantive legislation on environmental pollution. For example, the Industrial Emissions Directive (2010) requires operators to follow the principles of “taking all necessary precautions,” “best available techniques,” and “the principle of avoiding pollution” (European Commission, 2010). In the Waste Framework Directive (2008), prevention was defined as the measures taken before a substance, material, or product became waste and was prioritized in the waste hierarchy. The customary international law status of the precautionary principle is now undisputed, particularly within the EU region (Schröder, 2014). In the EC measures countering meat and meat products Case, the precautionary principle is already, in the view of the European Communities, a general customary rule of international law or at least a general principle of law (WTO, 2014).

Without full scientific certainty, the precautionary principle should require Parties to increase the standard of proof of the safety of plastic polymers, additives, and chemicals, thereby helping to prevent future environmental injustices and irreversible harm (Dauvergne, 2023; Vidar et al., 2023). The EU made a similar proposal during the first session of INC. Furthermore, the EU insisted that the precautionary principle should take precedence to prevent the spread of potentially unsustainable alternatives or substitutes in the second session of INC. In the third session, the EU’s pre-submission reaffirmed this principle’s fundamental and established status, and all the economic sectors must take responsibility that any plastic y plastic material, product, or component they intend to place on the market will not (or is very unlikely to) result in significant harm. It also suggested a technical review committee to assess the application of this principle (European Union, 2023d). The EU’s adherence to the precautionary principle extends from its domestic policy to this negotiation. As we can see from Table 2, its advocacy has progressed relatively smoothly with a relatively high level of support (56%). This principle is supported by most HAC members (Mexico, Cook Islands, Panama, and Japan) and by developing countries (such as Vietnam, Indonesia, and the Philippines).

4.1.2 The common but differentiated responsibilities principle

Throughout INC meetings, there was much discussion about the responsibilities of developed and developing countries and the common but differentiated responsibilities principle that will most likely play a significant part in this instrument (Stöfen-O’Brien, 2023). According to UNEP Resolution 5/14, plastic pollution needs to be tackled under the consideration of national circumstances and capabilities. It was formalized in international law at the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), the concept of which was enshrined as Principle 7 of the Rio Declaration and also strengthened in Article 3(1) of the 1992 UNFCCC, together with Article 2(2) of the Paris Agreement (2015) and the Preamble to the Kyoto Protocol (1997). However, it is hard to determine whether it has legally binding status as a principle since there is no explicit element in the Multilateral Environmental Agreements (MEAs). In general international law, however, the concept of common but differentiated responsibilities is likely to be regarded as an international environmental policy or a far-reaching soft law (Hey and Paulini, 2021).

The establishment of the principle was regarded as a compromise between developed and developing countries during the international climate negotiations and thus has been the target of controversy between them. According to the Rio Declaration, the basic idea of CBDR applied to marine plastic pollution could be that given the different contributions to global environmental degradation, States have common but differentiated responsibilities. Thus, developed countries with advanced technologies and sufficient financial resources have an immense contribution to global plastic waste and thus should carry a larger responsibility in the international pursuit of sustainable development (Wang, 2023). Conversely, developing countries that make a minor contribution to plastic waste should take less responsibility. The EU has accepted its responsibility as a developed country to significantly contribute to reducing global emissions in compliance with the CBDR principle and respecting the capacities of developing countries in the UNFCC, Kyoto Protocol, and Paris Agreement (Gayon, 2023). However, the EU’s position on plastic pollution changed. Most developing countries supported the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities, but Japan and the EU raised clear objections. EU stressed there was no relevance for the general application of the CBDR principle in the agreement and further insisted that it did not support individual principles (European Union, 2023d).

The principle is not always effective and was suspected of impeding the implementation of other international treaties in the climate change regime (Stöfen-O’Brien, 2023). Considering the complexity of plastics’ full life cycle approach, how to equitably allocate responsibility will also pose a significant challenge. On the one hand, this principle has the potential to push high-income plastic producers, consumers, and polluters in Europe and the United States to accept extra global responsibilities, including funding, cleaning up pollution, preventing illegal dumping, and ending the practice of exporting plastic waste to low-income countries (Dauvergne, 2023). On the other hand, the EU’s disagreement with CBDR may be related to its proposed polluter pays principle, which emphasizes that the costs of damages and remediation caused by environmental pollution are borne by the polluter rather than passed on to other groups and individuals.

4.1.3 The polluter pays principle

As complementary to the precautionary principle, the polluter pays principle to blame the polluter who causes environmental damage for the costs of remediation and compensation, ensuring the fair allocation of expenses for preventive and remedial measures (Wang, 2023; Zhu, 2023). In addition, it also acts as an incentive to encourage the polluters who bear the burdensome remediation costs to decrease the pollution. The principle first appeared in a legal context in a document prepared by the International Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) to encourage rational use of scarce environmental resources and to avoid distortions in international trade and investment (Larson, 2005). The principle has been adopted into many pollution-related multilateral conventions, as detailed in the 1992 Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (OSPAR Convention) and the 1996 Protocol to the Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter. The polluter pays principle has not been uniformly recognized in international law regarding legal status and specific content. However, its significance in environmental liability regimes worldwide could not be ignored. In the Rhine Chlorides Arbitration case (2014), the tribunal stated that although it did not view this principle as part of general international law, it admitted its importance in treaty law (PCA, 2014).

The Polluter Pays Principle has been widely recognized in EU environmental policies and legislation. The EU articulated the application of the polluter pays principle progressively. After being adopted in 1973, the polluter pays principle also appeared in the 1975 Recommendation 75/436 and further developed in the 1986 Single European Act (OCED, 2022). In addition, the European Commission adopted a white paper on environmental liability, stating that the Polluter Pays Environmental Liability regime should prevent further damage and allow polluters to internalize the environmental costs themselves, which means that the costs of preventing and restoring environmental damage will be paid by the parties responsible for the damage rather than being financed by society in general (European Commission, 2000). The European Court of Justice also supported this principle in protecting waters against pollution caused by nitrates from agricultural sources Case (CJEU, 1999), indicating that polluters are only liable for actions that impact environmental pollution. This principle has been utilized as an economic tool by implementing legislation such as the Waste Framework Directive (2008), Landfill Directive (1999), and Water Framework Directive (2000).

The EU’s position on the Polluter Pays Principle certainly extends to plastic pollution negotiations, which have been standing pat from the beginning (European Union, 2022a). During the second session, the EU emphasized the role and responsibilities of the private sector in ending plastic pollution, following the polluter pays principle. The responsibility of producers and manufacturers who introduce the raw material/product into the market are required to be accountable for financing collection in the third session (European Union, 2023d). In the latest revised draft, there are various options for providing funding, such as adopting the EU’s proposed polluter pays principle, which suggests that resource mobilization should include all sources, national and international, public and private. Parties should endeavor to mobilize additional private resources, including by aligning public and private investments and financing with the objectives and provisions of the instrument. Other options suggested that developed countries should provide new and additional financing to enable developing countries and Parties with economies in transition to cover the agreed full costs of measures to implement their commitments under this instrument (UNEP, 2023b). It may be one of the reasons why the EU and other Member States have different views on common but differentiated responsibilities. So far, many members stated that EPR was crucial, and there was broad support for the Polluter Pays Principle as a core instrument in contacting Group 1 of the third session.

4.2 Core obligations, control measures, and voluntary approaches

Control measures are clauses in a treaty specifically designed to prevent, minimize, or resolve the problems that prompted the instrument’s adoption. The problem of plastics in the ocean reflects very complex patterns of global ownership, production, and consumption and is thus an example of structural inequality among States (Fritz, 2020). The setback between two different “like-minded” groups—High Ambition, which the EU joined before the first session of INC, and Big Oils, representing the global petrochemical industry and plastic-producing countries, jeopardized a more robust agreement (Environmental Investigation Agency, 2023a). There is an apparent dichotomy between the countries that are the source of the pollution and the countries that are the victims. With High Ambition Coalition countries blaming oil- and plastics-producing countries for the production of plastics and oil- and plastics-producing countries blaming the former for ineffective waste management capacity, there is a greater divergence in the discussion of core obligations that focus on upstream production reduction or downstream waste management.

4.2.1 Reducing the supply of, demand for, and use of primary

At the present growth rate, plastic production is estimated to double within the next 20 years (Lebreton and Andrady, 2019). Global municipal plastic waste generation is projected to triple by 2060 (v. 2015 values) (UNEP, 2018a). To prevent the creation of plastic waste at the source, it is possible, on the one hand, to reduce or limit the production of plastics (polymers) based on fresh fossil fuels, i.e., Gas and petrochemical companies (Busch, 2022b). Another way to prevent plastic waste is by improving the design of plastic products to increase their reusability and recyclability (Simon et al., 2021). Moreover, the 5/14 resolution also stressed the importance of the resources they are made of and of minimizing waste generation, which can significantly contribute to sustainable production and consumption of plastics. The enormous global rate of plastic production, which has surpassed carbon emissions, is the primary cause of the plastic pollution crisis (Varvastian, 2023).

The EU adopted a non-legal binding policy framework on sourcing, labeling, and using biobased biodegradable and compostable plastics. The framework clarifies biobased, biodegradable, and compostable plastics and sets out the conditions to ensure that the overall environmental impact of their production and consumption is positive. It is estimated that the EU’s recycling target of 55 percent for 2025 will double the demand for reusable and recycled plastics to 10 million tons (European Commission et al., 2019). Suppose plastic producers decrease their reliance on fossil fuels and actively shift toward a sustainable, circular plastics economy in both production methods and consumption patterns. In that case, they can harness economic prospects while mitigating the potential for plastics to become waste in landfills, dumps, or environmental pollutants (Busch, 2022a). Preventing waste and pollution at source is less expensive than remediation (UNEP, 2022a). The high costs of both landfilling and energy from waste in the EU promote the circular economy of separation and recycling plastics in the EU because the disposal costs are greater than the combined sorting and recycling costs (Ackerman and Levin, 2023). Therefore, the EU aims to promote the principles of plastic reduction, recycling, and recovery in global governance and reduce the cost of governance by harnessing new technologies and boosting the capacity to produce alternatives.

The High Ambition Coalition to End Plastic Pollution is led by Rwanda and Norway, suggesting restraining and reducing the consumption and production of primary plastic polymers to sustainable levels (High Ambition Coalition to End Plastic Pollution, 2023). As a member of HAC, the EU also stressed the need for all Parties to use the future instrument to reduce the overall production of primary plastics to make production and consumption sustainable.

4.2.2 Waste management

A like-minded group, including Iran, Russia, India, Cuba, and some Western Asian countries, advocated for a legally binding instrument focusing on waste management rather than controlling production to limit the damage to plastic-producing countries. Cuba urged not to go beyond resolution 5/14 by focusing on eliminating plastic pollution and not including the production and commercialization of plastics. Reducing polymer production will significantly impact developing countries, producers, and importers (Cuba, 2023). Concerning waste management, the EU generates more plastic waste than its recycling capacity ( (European Commission, 2018). In 2015, only 9% of the plastics ever produced were recycled. Most plastics have accumulated in landfills or the natural environment (Geyer et al., 2017). European Union member states are the top plastic-consuming and plastic waste-exporting countries (Environmental Investigation Agency, 2023b). In 2020, of the top 10 plastic waste exporting countries, six were EU Member States (Environmental Investigation Agency, 2021). The EU produces large quantities of non-recyclable plastic waste exported to other countries, causing significant environmental damage.

In the context of weak downstream waste management, the EU has strongly urged that the instrument be based on the waste hierarchy as a guiding principle or overall target for waste management obligations. The waste hierarchy considers the entire life cycle of plastics, focusing on upstream waste prevention and preparation for reuse, followed by recycling (European Commission, 2008b). This proposal could be linked to the Basel Convention (1989), which has the principle of environmentally sound management (ESM), taking all practicable measures to ensure that hazardous waste or other waste is managed to protect human health and the environment from harmful effects. In addition, the EU and its MS consider the principle of Extend Producer Responsibility (EPR) as an essential tool to operationalize the polluter pays principle and one way for countries to strengthen waste management. The EU also suggests promoting waste prevention by incentivizing producers to develop sustainable products and putting the cost of collection, sorting, recycling, and littering on the private sector (European Union, 2023e). Generally speaking, the EU proposal on the waste hierarchy encouraging decisions that achieve the best overall environmental outcome rather than being bound by rigid rules aligns with the EU Waste Framework Directive (2008).

4.2.3 Extended producer responsibility

As a common legislative practice of the EU (Wang, 2023), the extended producer responsibility is regulated in the Waste Framework Directive (2008), which requires manufacturers to have and take appropriate measures to promote the design of products in a way that reduces their impact on the environment and the generation of waste during their manufacture and subsequent use can be minimized. Likewise, the Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment Directive (2012) transfers responsibility for collecting, reusing, and recycling electronic waste to the manufacturer (European Commission, 2012). The extended producer responsibility is based on the polluter pays principle—Principle 16 of the 1992 Rio Declaration, assigning long-term environmental responsibility for products (Sachs, 2006). It influences the production and discharge stages in the full lifecycle approach. During production, the plastic producer should ensure the reparability and reusability of products. They are also responsible for retrieving the plastic products they use during the discharge. It differs from the polluter pays principle, which only requires the polluter to shoulder the cost of pollution. The customers and people who discharge the pollution can also be the polluters. If so, the legal basis for EPR would disappear.

Extended producer responsibility is not only taken up in the alternative principles of the latest revised version. It is also controversial whether its implementation should be mandatory for each contracting party or according to their national circumstances. The EPR is a proven policy tool that has gained global support, not only in Europe. In recent years, Vietnam, the Philippines, and India have started implementing an EPR (UNEP, 2023c). However, there exists an unjust imbalance between developing countries that manufacture plastic production (Wang, 2023) and developing countries without advanced recycling technologies. Mandatory EPR responsibilities may be impractical and increase the burden on developing countries. The EU did not include it in the principles but presented the EPR proposal as one of the core commitments, control measures, and voluntary approaches. It suggests that each party shall establish and regulate EPR systems on a sector or product basis based on the modalities for the products in Annex D (European Union, 2023a). In addition, the EU supports a harmonized EPR system at the regional or global level and avoids a single EPR model, whereby each party would have to set up an EPR system adapted to its national circumstances.

4.3 National plans

The EU’s position on national plans, one of the main arguments for the implementation measure, is also worth analyzing. Whether to take a bottom-up (based on voluntary nationally-set commitments) or a top-down approach (based on binding globally-made commitments) remains one of the conflicts that impede the development of negotiations (Ballerini, 2023). Some States support voluntary programs and commitments based on national circumstances and capacities. In particular, each member designs the national plan according to its national circumstances and decides on the content of the engagement by establishing country-specific programs to combat plastic pollution. The goals are achieved jointly, based on the implementation of the commitments made by each party. Many countries may support this bottom-up mechanism because it gives the parties greater autonomy and flexibility and allows them to capitalize on their strengths in national circumstances. However, it could also have a narrow scope, focusing only on downstream issues such as waste management (IISD, 2023b).

Some members have different opinions due to their interests. The countries of the High Ambition Coalition to End Plastic Pollution (HAC) supported binding national plans with mandatory reporting requirements that included a top-down approach and advocated for a global standard of “mandatory Top-down division” (HAC, 2022). The implementation of the “top-down” mechanism is reflected in the adoption of a unified international agreement that sets specific goals and paths of action for the parties involved. Conversely, the “bottom-up” approach passively implements established programs and pathways. This model has a solid international legal binding force and includes strict compliance mechanisms, uniform accounting rules, and strict measurement, reporting, and verification protocols in its implementation framework. Such provisions guide countries’ actions based on scientific evidence and ensure the effectiveness of measures related to legal responsibilities. However, building consensus between all parties in this model proves difficult, leading to generally slow progress in the overall process.

The EU takes a relatively moderate stance on national plans. In the pre-session document of the first session of INC, the European Union referred to the 5/14 Resolution, acknowledging national plans as a plausible foundation. However, creating a global common indicator and monitoring is also significant, which could leverage established monitoring protocols from various regional seas conventions and other pertinent regional and international instruments (e.g., the Minamata Convention), along with the sustainable development goals’ monitoring framework for effective implementation. In the pre-session submission in the second session of INC, the EU stresses that national plans that could harmonize templates and guidance are not the only tool and insists that the core obligations or control measures, the design of recycling standards, the technical guidelines and requirements for transparency, information, and labeling, as well as the provisions for monitoring and reporting, should be global, regional or broadly formulated to allow for further implementation at the national level (European Union, 2023b, c). Overall, it suggested that the implementation should be based on national reporting (bottom-up) and environmental monitoring (top-down) (European Union, 2022b).

Resolution 5/14 and Zero Draft advocated a bottom-up mechanism that would promote more flexible national plans, taking into account national circumstances and capacities. But after several rounds of negotiations, Zero Draft also leaves more room for international monitoring, suggesting that “a combination of nationally and internationally agreed approaches can provide the necessary flexibility in implementing the prevention, reduction, and elimination of plastic pollution,” showing the possibility, of adding mandatory requirements. In general, the position of the EU is consistent with Zero Draft, reflecting the likelihood that international instruments on plastic pollution will further discuss a compromise between a top-down global framework and bottom-up voluntary national action.

4.4 Remarks on the EU’s position in the negotiations of the instrument

In light of our discussion above, the EU’s position on some key instrument elements continues the trend of its internal policies and legislation, such as the positive recommendation of the precautionary principle, the polluter pays principle, and extended producer responsibility. Regarding core obligations and control measures, the EU and HAC support a focus on upstream governance, which focuses on reducing the supply of, demand for, and use of primary. For the implementation measure, the EU has taken a more moderate and compromising stance on national plans, recognizing their importance but also stressing the necessity of regulation at the global level.

The EU’s proposals have made some progress. Firstly, the minimum elements proposed by the EU are partly supported by the Zero draft, such as covering the entire life cycle of plastics, extended producer responsibility, and recycled plastic content. Whether these elements are mandatory is controversial, as the Zero draft uses the term “relevant elements,” which the EU later introduced with a proposal to change to “necessary measures” to make it more binding. Second, among nearly 180 attendees, 135 explicitly call for binding global rules that apply equally to all countries rather than a voluntary agreement (World Wide Fund for Nature, 2023). Therefore, the compromise between a top-down global framework and bottom-up voluntary national action proposed by the EU may get high support in the future. In addition, the EU’s proposal calling for the Treaty to prioritize banning or phasing out problematic polymers, chemicals, and high-risk plastic products is likely reflected in the final instrument because more countries are joining the HAC, and more than half of the attendees favor this obligation (World Wide Fund for Nature, 2023).

5 The EU’s diplomacy strategy during the negotiations

As an international leader, the EU would be expected to pursue highly ambitious policy objectives and realize them to a high degree through its activities (Oberthür and Rabitz, 2014). In addition to assessing the EU’s proposals on instrument elements during the negotiations, we also consider that its diplomacy strategy may translate its weight into actual impact in the negotiations. The EU may promote its goal achievement by building different coalitions or alliances, which may require concessions and compromises. It may also focus on building bridges between other negotiating parties and coordinating between them to maximize their interests (Oberthür and Groen, 2018).

The EU has demonstrated high diplomatic activity inside and outside the plastic instrument negotiations. It utilizes regional and bilateral dialogues and ocean-related development cooperation. As one of the active participants in the negotiations on the plastics instrument, the EU has continued to make written submissions to the conference, and its resolution underscoring the need for concerted action to address the interconnected challenges was adopted by UNEA (European Commission, 2024). Beyond the conferences, the EU engaged very actively in other forums to actively cooperate and communicate with other countries, such as the Ministerial Meeting on Environment and Climate Change between the Ministers of the Environment of Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) and the European Union and G7 Hiroshima 2023. Its diplomacy also involved the highest political levels, such as the Joint Statement of the EU-Japan Summit, EU-Canada Summit, and EU- Republic of Korea 2023 on plastic pollution.

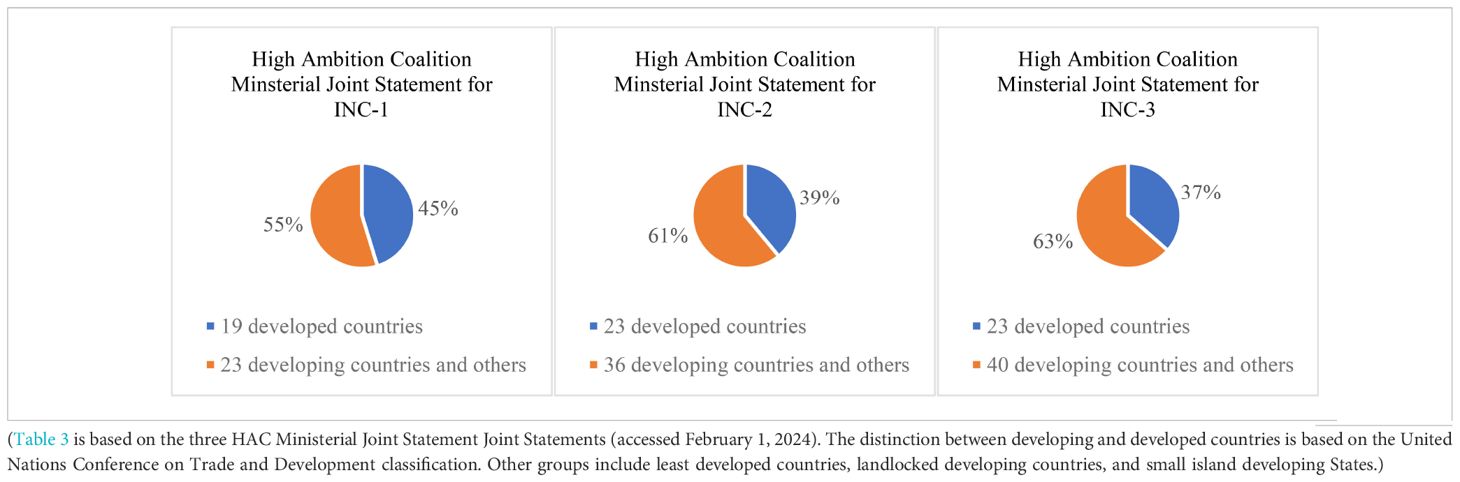

Second, it actively participates in coalition building to increase negotiating influence and expand consensus. The EU joined the HAC Coalition before the first session of INC. So far, according to the INC-3 Ministerial Statement, more developing countries joined the High Ambition Coalition (Table 3). Moreover, the least developed country - Guinea - joined the INC-2 Statement, followed by Solomon Islands and Togo in the INC-3 Joint Statement, which means that in addition to developed countries, the position of HAC, such as the reduction of plastic production and environmentally sound management may be supported by more developing countries and least developed countries.

Third, the EU shows its leadership through example. To reduce shipments of problematic waste outside the EU, it reached a preliminary political agreement in 2023 to amend the Waste Shipment Regulation (2006), meaning that countries in the global south will no longer serve as landfills for European developed countries. In response to the increasing total amount of packaging waste, the EU Parliament has decided to increase the reduction targets for plastic packaging, setting specific targets for reducing plastic packaging (10% by 2030, 15% by 2035, and 20% until 2040) (European Parliament, 2023). The EU also contributes to technical support and funding for developing countries. As one of the most important donors of ocean-related development aid and voluntary contributors to international organizations and processes (European Commission, 2022a), it committed €1 million to Blue Mediterranean to catalyze sustainable blue economy investments in plastic waste reduction in the non-EU countries of the Mediterranean region (EU Blue Economy Observatory, 2023). In addition, the EU is also committed to working with UNEP until 2026 on deploying appropriate technologies, waste recycling systems, and institutional and human capacity.

6 The challenges in the future negotiations

The last but most important aspect of assessing the achievement of the EU’s objectives is to analyze the challenges that the EU now faces. Although most countries call for an ambitious agreement covering the entire life cycle of plastics, the High Ambition Coalition and the EU must confront the conflicts between fossil fuel and petrochemical exporters. It is calculated that 43 chemical and fossil fuel industry lobbyists have signed up for the third round of negotiations, 36 percent more than the last round (Center for International Environmental Law, 2023). Notably, the U.S. – one of the world’s top generators of plastic waste – has been slow to endorse ambitious goals. It showed a wavering attitude towards the plastics instrument, given its previous experience in climate negotiations. The Biden administration recently agreed that national plans should be based on a globally agreed target for reducing plastic rather than simply calling on countries to act individually (Morath, 2023), which may promote the proposal of the EU. Japan opposes the EU’s approach of demanding uniform measures internationally and favors greater national autonomy. In this respect, Japan’s position may not be conducive to implementing the instrument, as it may weaken its unity and binding force (Xu et al., 2023).

The EU needs to adopt more moderate positions, such as the national plans, if it wants to achieve a higher level of achievement of its objectives. In multilateral negotiations, extreme positions have less chance of success than moderate ones, as agreements between several key actors/coalitions require compromises (Oberthür and Groen, 2018). How to seek more consensus in future negotiations while striving for more national interests is a challenge the EU will always need to face in subsequent negotiations. Developing countries may not support the stance against the CBDR principle because this policy preference will reduce the historical responsibility of developed countries in plastic pollution control and reduce the obligation of developed countries to help developing countries in plastic pollution control. The EU should consider the diverse stages of development in developing countries to show greater inclusiveness in future negotiations and share technology, finance, and experience with all parties to support plastic reduction actions on a global scale. Capacity-building and the transfer of marine technology (CBTMT) are key elements for developing countries to fulfill their obligations under the agreement. It remains controversial whether capacity-building and transfer should be limited to assisting states meet their treaty obligations or include realizing broader social and economic objectives (Mendenhall, 2023b).

Moreover, it may gain wider acceptance by sharing best practices, scientific research, and policy experiences from different countries to understand the balance between different interests better. In addition, the EU needs to realize the importance of establishing a transparent information-sharing mechanism. Monitoring and surveillance capabilities are vital for detecting and addressing marine pollution, which includes investing in technology, improving data collection and analysis, and enhancing cooperation among countries for information sharing (Vidar et al., 2023).

7 Conclusion

In conclusion, due to a lack of adequate and concrete rules and principles, the current fragmented and reactive framework for global ocean governance and pollution control has resulted in a coordination gap at the legislative and implementation levels. As a leader in plastics governance, the EU has positively shaped its preferences and role in the plastic pollution governance process. At the global governance level, the EU promoted consolidating the global plastic waste governance system and introduced several relevant initiatives and programs in response to United Nations standards. The internal policies and legislation also address the regulatory challenges and obstacles at the national level with positive and tangible results that could set an example for other states and give credibility to the EU proposal in the negotiations. Given the current negotiation process, the EU made recommendations on instrument elements and tried to integrate EU programs such as the environmentally sound management policy, the waste hierarchy, the precautionary principle, the polluter pays principle, and extended producer responsibility into international rules. The EU’s persistence and coordination of its position, as well as its focus on multilateral cooperation and strong environmental standards, continue the EU’s long-standing commitment to promoting international cooperation and ensuring environmentally sustainable development.

Furthermore, the EU’s diplomatic engagement beyond the negotiations can also contribute to achieving the EU’s proposals to reach a broader consensus with different countries. Our analyses demonstrate the assessment framework’s usefulness, combining multiple factors to reveal the EU’s influence before and after the negotiation process. We therefore assume that the EU’s objectives will be achieved at a high level in future negotiations due to the interaction of the above favorable situations. However, the challenges the EU faces and how it responds will also affect realizing its objectives, which may require the EU to adopt a more moderate stance and compromise on some issues.

States may enjoy a differentiated status in the international law-making of the law of the sea due to differences in their geographical situation (Chen and Xu, 2022a). The matter of plastics goes beyond a mere environmental concern, and the intricacies in negotiating a global legal instrument on plastics pose challenges akin to those encountered in climate negotiations. Plastic’s full life cycle approach holds relevance across various industries. The plastic economy is a fundamental pillar for some chemical and plastics-producing countries, and plastics are also undoubtedly indispensable consumer products for most countries. Thus, it is clear that there will be different positions, concerns, and strategies in this value chain that take time to reconcile. After all, international negotiations are often accompanied by insistence and concession, confrontation and cooperation, unilateralism and multilateralism. The importance and urgency of this global environmental issue and the prioritization of the rights and interests of all parties will influence the direction of this global convention and the effectiveness of the solution to the plastics problem. It remains to be seen whether the EU will seek balance and cooperation in future negotiations and continue to play a leading role by introducing a more comprehensive program that considers all parties’ interests and addresses existing challenges.

Finally, we acknowledge the limitations of this paper. We have constructed an assessment framework by integrating key and process-related factors, providing a more comprehensive analysis than a single-round negotiation analysis. However, there is more room for progress in this framework. Other factors, such as motivation to participate in negotiations and other key instrumental elements, have yet to be discussed. Furthermore, the framework could be better applied by including comparisons with other countries. We will address these gaps in future research and conduct further research to test and refine the framework.

Author contributions

QX: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. MZ: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis. SH: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Formal analysis.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities Project No. 23JNQN04; National Social Science Foundation Project No. 23VHQ016.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

- ^ Legally binding instrument: According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and United Nations Treaty Collection, international instruments binding at international law are treaties, agreements, conventions, charters, protocols, declarations (declarations are not always legally binding), memoranda of understanding, modus vivendi and exchange of note. They can be adopted by intergovernmental organizations’ governing or decision-making bodies or by ad hoc negotiating groups (e.g., negotiating conferences) specifically set up for this purpose. They are addressed to states, who - if any necessary procedures to become parties to them have been completed - will have an obligation under international law to implement them. See https://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/IO-Rule-Based%20System.pdf.

- ^ Full lifecycle: According to UNEP, the full lifecycle approach of plastics may be simplified into upstream, midstream, and downstream activities. Upstream activities include obtaining raw materials from crude oil, natural gas, or recycled and renewable feedstock and polymerization. Midstream activities involve the design, manufacture, packaging, distribution, use (and reuse), and maintenance of plastic products and services. Downstream activities involve end-of-life management--including segregation, collection, sorting, recycling, and disposal. See https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/40767/K2221533%20-%20%20UNEP-PP-INC.1-7%20-%20ADVANCE.pdf.

- ^ Zero Draft: The Zero Draft text is proposed to facilitate and support the intergovernmental negotiating committee’s work towards developing the international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment, called for by United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) resolution 5/14. It does not prejudge the committee’s decisions on the content of the future instrument. See https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/43239/ZERODRAFT.pdf.

- ^ Principle 7 of the Stockholm Declaration (1972): “States shall take all possible steps to prevent pollution of the seas by substances that are liable to create hazards to human health, to harm living resources and marine life, to damage amenities, or to interfere with other legitimate uses of the sea.”

- ^ In accordance with Article 1 of UNCLOS, "Pollution of the marine environment" means the introduction by man, directly or indirectly, of substances or energy into the marine environment, including estuaries, which results or is likely to result in such deleterious effects as harm to living resources and marine life, hazards to human health, hindrance to marine activities, including fishing and other legitimate uses of the sea, impairment of quality for use of sea water and reduction of amenities.

- ^ Article 207 of the UNCLOS provides that States shall adopt laws and regulations to prevent, reduce, and control pollution of the marine environment from land-based sources, including rivers, estuaries, pipelines, and outfall structures, taking into account internationally agreed rules, standards, and recommended practices and procedures. Articles 210 and 211 regulate pollution prevention, reduction, and control by dumping and pollution from vessels. In addition, articles 213 to 222 provide for the implementation by States of measures necessary to prevent, reduce, and control pollution in all its aspects, as well as applicable international rules and standards established through competent international organizations or international conferences.

- ^ Principle 15 of the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development (1992): “In order to protect the environment, the precautionary approach shall be widely applied by States according to their capabilities. Where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation.”

- ^ Principle 16 of the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development (1992): “National authorities should endeavour to promote the internalization of environmental costs and the use of economic instruments, taking into account the approach that the polluter should, in principle, bear the cost of pollution, with due regard to the public interest and without distorting international trade and investment.”

- ^ Principle 7 of the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development (1992): “States shall cooperate in a spirit of global partnership to conserve, protect, and restore the health and integrity of the Earth's ecosystem. In view of the different contributions to global environmental degradation, States have common but differentiated responsibilities. The developed countries acknowledge the responsibility that they bear in the international pursuit of sustainable development in view of the pressures their societies place on the global environment and of the technologies and financial resources they command.”

- ^ According to the European Commission, EU legislation is divided into two classes: Primary legislation consists of treaties between EU member countries. They set out EU objectives, rules for EU institutions, how decisions are made, and the relationship between the EU and its member countries. Every action taken by the EU is founded on treaties. Treaties are comparable to constitutional law in many countries. Secondary legislation consists of regulations, directives, decisions, recommendations, and opinions used to implement the policies set out in the treaties. Regulations are binding legislative acts that apply directly to all member states. They often concern trade issues. Directives are legislative acts that set out goals that all EU countries must achieve. However, it is up to the individual countries to devise their own laws to reach these goals. Decisions are binding on those it addresses (e.g., an EU country or an individual company) and are directly applicable. Recommendations allow EU institutions to make their views known and to suggest a line of action without imposing any legal obligation on those to whom it is addressed. They are not legally binding. Opinions are issued by the main EU institutions (Commission, Council, Parliament), the Committee of the Regions and the European Economic and Social Committee. They are not legally binding.

- ^ The High Ambition Coalition to End Plastic Pollution (HAC) is committed to developing an ambitious international legally binding instrument based on a comprehensive and circular approach that ensures urgent action and effective interventions along the full lifecycle of plastics. According to HAC Member States Ministerial Joint Statement INC-3, there are 63 members. They are Antigua & Barbuda, Armenia, Australia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belgium, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Cabo Verde, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Cook Island, Costa Rica, Denmark, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Estonia, European Union, Federated States of Micronesia, Finland, France, Gabon, Georgia, Germany, Ghana, Greenland, Guinea, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Japan, Jordan, Luxembourg, Malawi, Maldives, Mali, Mauritius, Mexico, Moldova, Monaco, Montenegro, Netherlands, New Zealand, Nigeria, Norway, Palau, Panama, Peru, Portugal, Republic of Korea, Romania, Rwanda, Senegal, Seychelles, Slovenia, Solomon Islands, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Togo, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and Uruguay.

References

Ackerman J., Levin D. B. (2023). Rethinking plastic recycling: A comparison between North America and Europe. J. Environ. Manage. 340, 117859. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.117859

Bäckstrand K., Elgström O. (2013). The EU’s role in climate change negotiations: From leader to ‘leadiator’. J. Eur. Public Policy 20, 1369–1386. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2013.78178

Ballerini T. (2023). Global plastics treaty: upsides and downsides of the second round of negotiations. Available online at: https://www.renewablematter.eu/articoli/article/Global-Plastics-Treaty-the-second-round-of-negotiations-plastic-pollution (Accessed 1/12/2024).

Beltran M., Tjahjono B., Suoneto T. N., Tanjung R., Julião J. (2023). Rethinking marine plastics pollution: Science diplomacy and multi-level governance. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 90 (1), 237–258. doi: 10.1177/00208523231183909

Busch P. O. (2022a). Analysis of Upstream Economic Opportunities from change in the plastics lifecycle. Available online at: https://adelphi.de/system/files/mediathek/bilder/GPA_Economic_Opportunities.pdf (Accessed 1/10/2024).

Busch P. O. (2022b). Small Island Developing States and plastic pollution- Challenges and opportunities of a global agreement on plastic pollution for SIDS. Available online at: https://adelphi.de/en/publications/small-island-developing-states-and-plastic-pollution (Accessed 1/12/2024).

Center for International Environmental Law. (2023). Fossil Fuel and Chemical Industries Registered More Lobbyists at Plastics Treaty Talks than 70 Countries Combined. Available online at: https://www.ciel.org/news/fossil-fuel-and-chemical-industries-at-inc-3/ (Accessed 1/12/2024).

Chen X., Xu Q. (2022a). Mitigating effects of sea-level rise on maritime features through the international law-making process in the Law of the Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 1072390. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.1072390

Chen X., Xu Q. (2022b). Reflections on international dispute settlement mechanisms for the Fukushima contaminated water discharge. Ocean Coast. Manage. 226, 106278. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2022.106278

CJEU. (1999). The Queen v Secretary of State for the Environment and Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, ex parte H.A. Standley and Others and D.G.D. Metson and Others. In Judgment of the Court (Fifth Chamber) of 29 April 1999, European Court Reports 1999. (CJEU, 1999).

Copernicus Marine Service. (2017). Copernicus Marine Service Side Event at the UN Ocean Conference on June 8th. Available online at: https://marine.copernicus.eu/news/copernicus-marine-service-side-event-un-ocean-conference-june-8th (Accessed 1/16/2024).

Copernicus Marine Service. (2020). Marine Plastic Pollution: New content on Copernicus Marine website. Available online at: https://marine.copernicus.eu/news/marine-plastic-pollution-new-content-copernicus-marine-website (Accessed 1/19/2024).

Cuba. (2023). In-session Submissions on Primary Plastic Polymers INC-3. Available online at: https://resolutions.unep.org/resolutions/uploads/cubaprimaryplasticpolymers.pdf (Accessed 12/1/2023).

Da Costa J. P., Catherine M., Mónica M., Armando C. D., Teresa R. S. (2020). The role of legislation, regulatory initiatives and guidelines on the control of plastic pollution. Front. Env. Sci. 8. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2020.00104

Dañobeitia J. J., Pouliquen S., Pade N., Arvanitidis C., Sanders R., Stanica A., et al. (2023). The role of the marine research infrastructures in the European marine observation landscape: present and future perspectives. Front. Mar. Sci. 10. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1047251

Dauvergne P. (2023). The necessity of justice for a fair, legitimate, and effective treaty on plastic pollution. Mar. Policy 155, 105785. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2023.105785

Earth Day. (2023). From fossil fuels to plastic addiction: unveiling the hidden link impacting our world. Available online at: https://www.earthday.org/from-fossil-fuels-to-plastic-addiction-unveiling-the-hidden-link-impacting-our-world/ (Accessed 1/1/2024).

Eckert S., Karassin O., Steinebach Y. (2024). A policy portfolio approach to plastics throughout their life cycle: Supranational and national regulation in the European Union. Environ. Policy Gov. 1–15. doi: 10.1002/eet.2092

Environmental Investigation Agency. (2019). Basel Convention scores a major victory in the war on plastic pollution. Available online at: https://eia-international.org/news/basel-convention-scores-a-major-victory-in-the-war-on-plastic-pollution/ (Accessed 1/12/2024).

Environmental Investigation Agency. (2021). The Truth Behind Trash: The scale and impact of the international trade in plastic waste. Available online at: https://eia-international.org/wp-content/uploads/EIA-The-Truth-Behind-Trash-FINAL.pdf (Accessed 1/15/2024).

Environmental Investigation Agency. (2023a). Big Oil influence at UN talks thwarts progress towards reaching an effective Global Plastics Treaty. Available online at: https://eia-international.org/news/big-oil-influence-at-un-talks-thwarts-progress-towards-reaching-an-effective-global-plastics-treaty/ (Accessed 1/16/2024).

Environmental Investigation Agency. (2023b). Plastic Waste Power Play. Available online at: https://eia-international.org/wp-content/uploads/EIA_UK_Plastic_Waste_Trade_Report_0123_FINAL_SPREADS.pdf (Accessed 1/12/2024).

EU Blue Economy Observatory. (2023). COP28: Commission commits €1 million to Blue Mediterranean Partnership. Available online at: https://blue-economy-observatory.ec.europa.eu/news/cop28-commission-commits-eu1-million-blue-mediterranean-partnership-2023-12-12_en?prefLang=el (Accessed 1/12/2024).

European Commission. (1994). Directive 94/62/EC. Available online at: https://eurlex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:31994L0062:EN:HTML (Accessed 11/11/2023).