Abstract

Background:

Patients with severe traumatic brain injury (sTBI) often require mechanical ventilation and have a high incidence of aspiration pneumonia, leading to prolonged antibiotic exposure. This study assesses the association between high lateral position (HLP) and antibiotic exposure duration in sTBI patients, and reports on safety and feasibility.

Methods:

This study retrospectively collected data from 138 patients with severe traumatic brain injury complicated by aspiration pneumonia who were treated in the intensive care unit from January 2023 to June 2024. Patients were divided into two groups based on whether they received high lateral position (HLP) therapy: the HLP group (n = 45) and the non-HLP group (n = 93). Univariate and multivariate linear regression analyses were used to identify independent risk factors associated with the duration of antibiotic use, and the association between HLP therapy and antibiotic use duration was evaluated by comparing the two groups.

Results:

Patients who received HLP had a shorter duration of antibiotic use; both univariate and multivariate regression analyses suggested an association between HLP and shorter duration of use. Univariate linear regression analysis showed that HLP, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), arterial oxygen partial pressure, and oxygenation index were all associated with the duration of antibiotic use. Multivariate linear regression analysis further confirmed that HLP was independently associated with a shorter duration of antibiotic use (β = −2.58; 95% CI, −4.44 to −0.71; p = 0.008), while COPD was associated with a longer duration of use (β = 8.78; 95% CI, 4.42 to 13.13; p < 0.001).

Conclusion:

In this retrospective cohort, HLP was associated with a shorter duration of antibiotic exposure and showed trends toward fewer days of mechanical ventilation and a lower tracheostomy rate. Given the nonrandomized design and potential residual confounding, these findings are exploratory and should be confirmed in prospective randomized studies.

Introduction

Severe traumatic brain injury (sTBI) affects more than 50 million individuals worldwide each year and is a leading cause of death and long-term disability, with substantial socioeconomic burden (1, 2). Patients with sTBI commonly experience impaired cough, secretion retention, and a heightened risk of aspiration due to neurogenic respiratory dysregulation (3, 4). Secondary pulmonary infection increases mortality three- to five-fold, underscoring the importance of early, targeted respiratory care (5). Optimizing respiratory management is therefore central to improving outcomes in sTBI, and enhanced airway care has been associated with shorter antibiotic courses, reduced multidrug-resistant (MDR) infections, and lower rates of failed extubation (6, 7).

In neurocritical care, secretion retention and ventilation–perfusion mismatch are major drivers of prolonged antibiotic therapy and pulmonary complications. Among non-pharmacological strategies, body positioning can be used to leverage gravity for mucus clearance and to improve V/Q matching (8). Prone positioning (PP) enhances oxygenation and aids secretion clearance in acute respiratory distress syndrome (9, 10), but its use in patients with acute brain injury is limited by concerns about intracranial pressure (ICP) and practical challenges. Several studies report moderate but significant ICP elevations during PP with premature termination in a proportion of patients (11), whereas others suggest acceptable changes in ICP (12). Proposed mechanisms include increased intra-abdominal pressure and restricted jugular or vertebral venous outflow, which may impair cerebral venous drainage (13). PP can also complicate bedside care (e.g., pressure injury risk, constraints on pupillary assessment) (14–16), further limiting its adoption in this population.

Given these limitations, high lateral positioning (HLP) is considered a more feasible alternative that may be friendlier to cerebral venous outflow. Executed at roughly 90° lateral tilt with 15–30° head-of-bed elevation and a neutral neck, HLP avoids abdominal compression and may help preserve ICP and cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) stability while gravity supports secretion drainage—a mechanistic hypothesis that requires clinical testing. Preliminary evidence in neurosurgical cohorts suggests that, under appropriate angles with head elevation, lateral positioning does not significantly alter ICP or CPP (17), and the physiologic rationale that ~30° head elevation lowers ICP and supports CPP is relatively consistent (18). Hemodynamic modeling and observational signals further indicate that the lateral decubitus position may reduce extracranial venous resistance and optimize cerebral venous outflow (19). Although oxygenation benefits comparable to PP have been reported with HLP (20), data in sTBI on antibiotic exposure duration, pulmonary physiology, and secretion drainage remain limited. We therefore assessed the association between HLP and antibiotic exposure in a real-world neurocritical care setting, and we report safety and feasibility to inform future trials.

Methods

Study design and participants

This retrospective cohort study was conducted in the intensive care unit of the aforementioned hospital from January 2023 to June 2024. All procedures were strictly in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Clinical Medical College of Fujian Medical University (Approval No. K2022-09-061). Data were retrospectively extracted from the clinical information system database of the participating hospital. Given the non-interventional and observational nature of this study and the absence of any physiological risks to patients, the ethics committee waived the requirement for informed consent. All patient data were anonymized and processed in strict compliance with institutional privacy protection protocols.

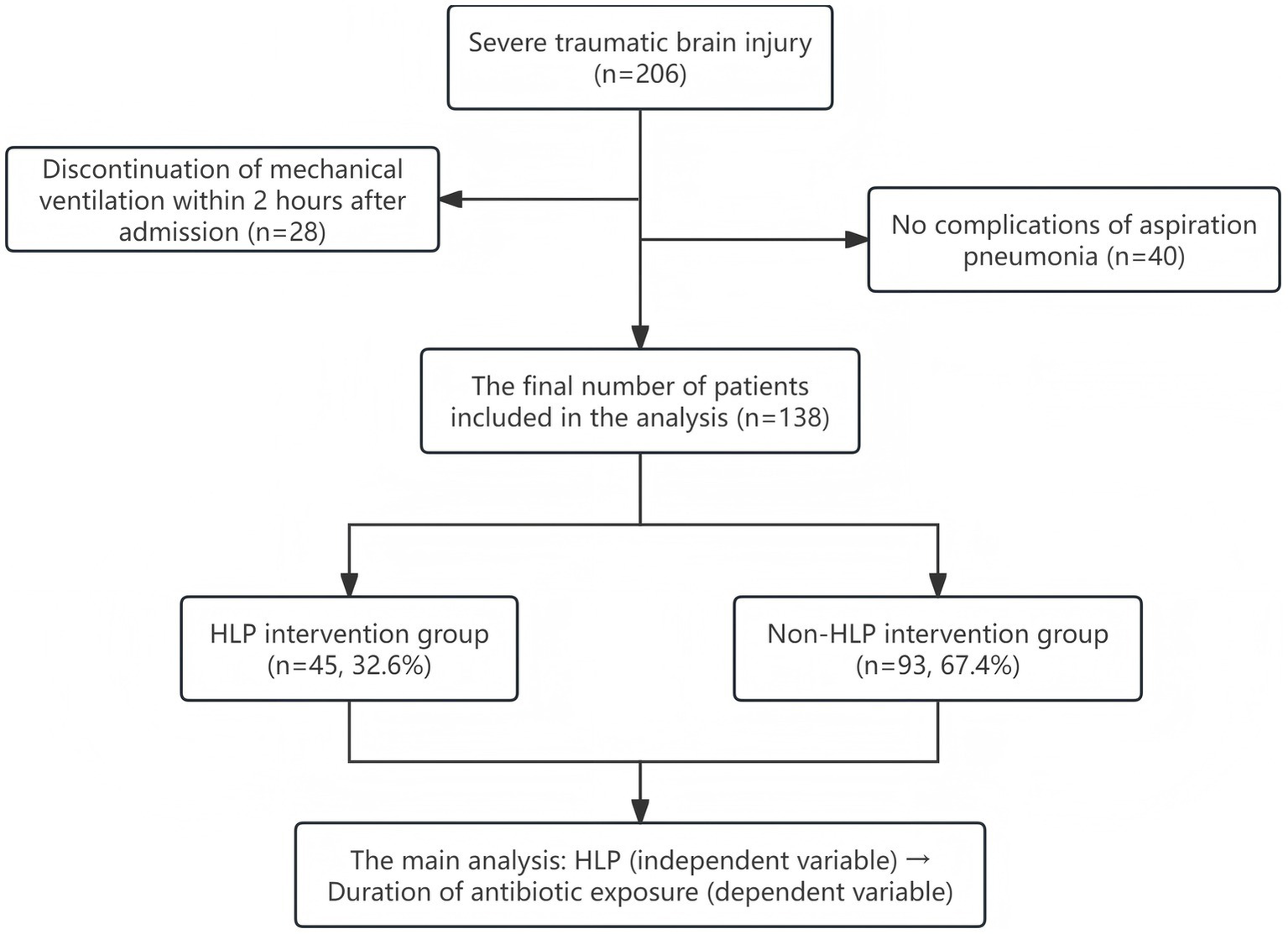

All patients included in this study met the following criteria: (1) Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score ≤8; (2) radiologically confirmed aspiration pneumonia; (3) age between 18 and 80 years; (4) ICU stay of at least 7 days; (5) initiation of invasive mechanical ventilation upon admission. Exclusion criteria included: (1) presence of active bleeding, spinal cord injury, or patients in late pregnancy; (2) combined hemothorax and pneumothorax or severe arrhythmias; (3) death or self-discharge within 7 days of admission. Based on the diagnostic criteria for traumatic brain injury (TBI), a total of 863 TBI patients were initially identified. According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 206 patients with GCS scores ≤8 who received mechanical ventilation upon admission were selected as severe TBI (sTBI) patients. Among them, 28 patients had mechanical ventilation discontinued within 2 h of admission. Based on chest X-ray or CT findings, 40 patients were diagnosed with simple pneumonia and were excluded from the study. After screening, a total of 138 sTBI patients with aspiration pneumonia were finally included for analysis (see Figure 1). This study primarily investigated the association between HLP and antibiotic exposure duration, with HLP as the independent variable and antibiotic exposure duration as the dependent variable. The screening results showed that approximately 67.4% (93/138) of the finally selected patients did not receive HLP intervention, while 32.6% (45/138) did. Through a strict screening process, the homogeneity of the patients was ensured, and the impact of confounding factors was minimized to the greatest extent. This provided a solid basis for analyzing the effectiveness of HLP intervention and a certain degree of comparability for subsequent association analysis.

Figure 1

Flowchart of patient selection.

Intervention

Positioning intervention and control

Both groups in this study received standardized evidence-based position care. The control group (non-HLP) implemented head-of-bed (HOB) elevation at 30° (acceptable range 25–35°) and routine position changes every 2 h (15–30° lateral rotation), and routinely performed chest physiotherapy and airway management, with processes in line with guidelines for neurocritical care and pressure ulcer prevention (21).

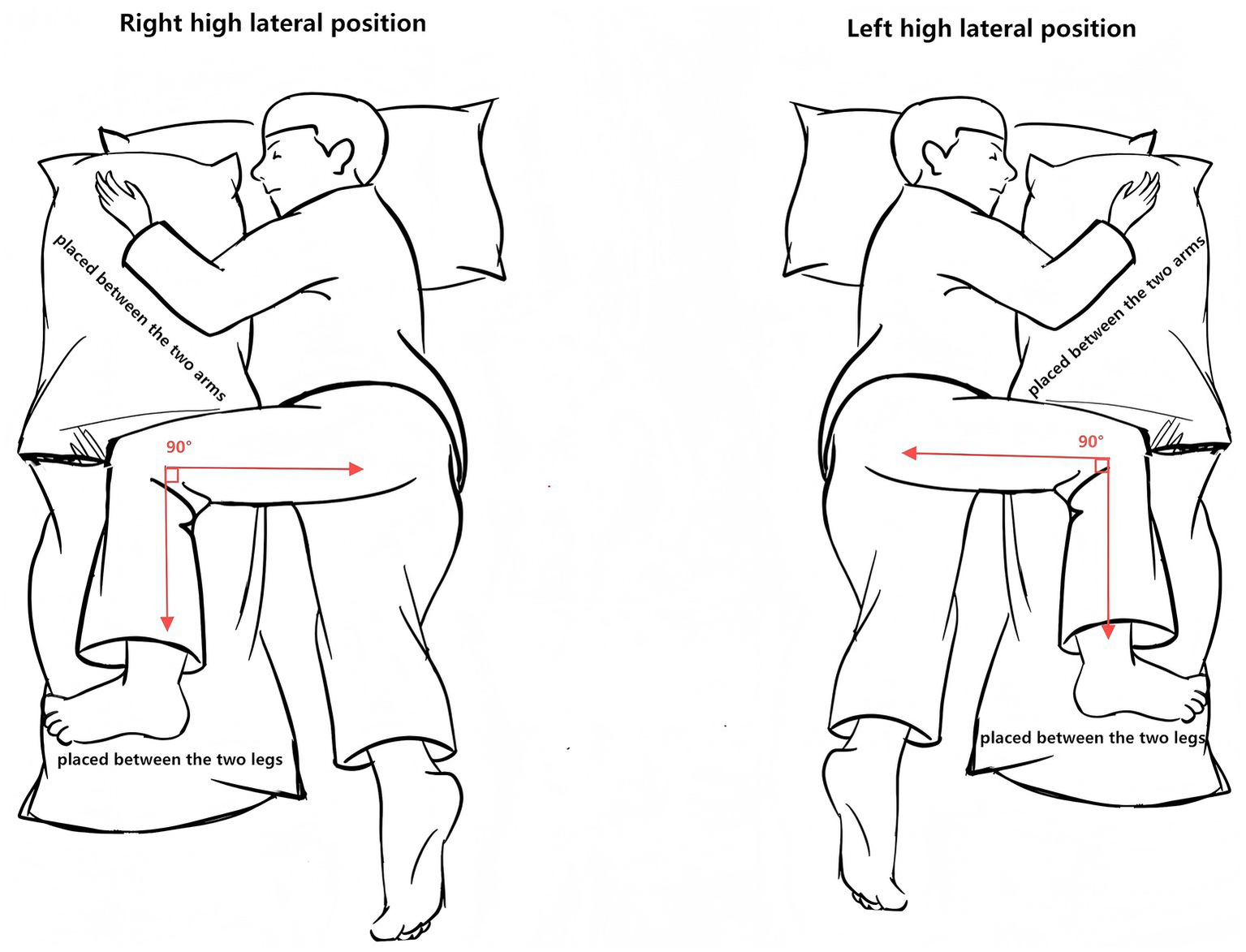

The HLP group added high lateral position (HLP) as a positioning intervention on top of the above standard care and implemented it according to a predefined standard operating procedure (SOP). Patients were turned to approximately 90° lateral tilt with 15–30° head-of-bed elevation and a neutral neck position, with all catheters carefully secured. HLP sessions alternated left and right every ~2 h (approximately 2 h on each side), targeting a cumulative daily duration of 10–12 h, based on previous positioning-therapy studies aiming to redistribute ventilation/perfusion and enhance gravitational secretion drainage (20, 22). Throughout HLP, patients were placed on a pressure-relieving mattress to minimize the risk of pressure injury (22). Before initiating HLP, major contraindications (e.g., spinal cord injury, active bleeding, severe arrhythmia) were screened, and catheter patency and skin condition were checked. Vital signs, skin integrity, and respiratory parameters were monitored throughout, and HLP was stopped if ICP exceeded 25 mmHg for ≥ 5 min, mean arterial pressure decreased by > 20%, or persistent hypoxemia or new-onset arrhythmia occurred. Spinal neutrality and line protection were maintained at all times. A detailed step-by-step description of staff roles, turning technique, and device use is provided in Supplementary Appendix 1 and is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Diagram of the high lateral positioning (HLP) protocol.

Covariates and pre-intervention physiologic window

To control for the impact of confounding factors on the association between HLP and antibiotic exposure duration, we systematically collected four categories of covariates: (1) baseline characteristics, including sex, age, and comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], chronic kidney disease, coronary heart disease); (2) physiological indicators, including Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, APACHE II score, SOFA score, ICP, CPP, MAP, and use of vasopressors; (3) laboratory parameters, including arterial blood gas analysis, inflammatory markers, and related biochemical indicators on the first and seventh days of admission; and (4) sedation depth, assessed using the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS). Based on clinical relevance and prior literature, only a subset of these variables (age, sex, COPD, PaO₂ on day 1, and PaO₂/FiO₂[P/F] ratio on day 7) was entered into the multivariable regression models, whereas the remaining variables were used for descriptive comparisons and sensitivity checks.

In addition, to reduce the selection bias that “more stable patients are more likely to receive HLP,” we systematically collected data before the first implementation of HLP (for the non-HLP group, the corresponding disease course time window was used), including physiological and intensity of care variables: ICP, CPP, MAP, P/F, PaCO₂, ventilator parameters, RASS, exposure to sedation/paralysis, 24-h cumulative fluid balance, and microbiological/antibiotic resistance information. This dataset was used to test the comparability of pre-intervention physiology and care intensity between groups and to inform the selection of clinically relevant covariates for the multivariable models, thereby reducing residual confounding as far as possible in this retrospective design.

Outcome definition and antimicrobial stewardship

Primary outcome: antibiotic exposure days, defined at the patient level as the number of calendar days from the first dose of any systemic antibiotic to the final discontinuation of all systemic antibiotics (end − start + 1). Days on which two or more systemic antibiotics were administered concurrently were counted as a single antibiotic exposure day. Antibiotic switches without gaps were considered part of the same treatment episode. An independent Antimicrobial Stewardship Program (ASP) oversaw discontinuation decisions throughout the 18-month period without changes in team or policy. Discontinuation required concurrent, prespecified criteria (23, 24): (a) clinical improvement—temperature < 38 °C for ≥ 24 h; (b) laboratory improvement—procalcitonin ≤ 0.5 ng/mL or ≥ 80% reduction from baseline and normalization of white blood cell count; and (c) radiological improvement—documented by a radiologist on chest X-ray or CT.

All patients received standardized ICU management, including neurosurgical intervention, dehydration to reduce intracranial pressure when indicated, anti-infective treatment, prevention of complications, and enteral nutrition. Sedation/analgesia followed contemporary ICU guidelines (25): propofol, midazolam, or dexmedetomidine were selected based on the condition, and the RASS target was controlled at −3 to −2 during the acute phase of mechanical ventilation; when the condition permitted, a transition to lighter sedation (−2 to 0) was attempted, with assessment every 2 h. Core body temperature was maintained at 36–37 °C using physical cooling methods. Nursing interventions included continuous monitoring of vital signs, airway humidification management, and repositioning and back percussion every 2 h to facilitate sputum expulsion.

Statistical analysis

Normally distributed variables were presented as mean (SD), skewed variables as median [IQR], and categorical variables as n (%). Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables, as appropriate, and Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables. Linear regression models (β, 95% CI) were used to assess associations between covariates and antibiotic exposure duration. Model assumptions were evaluated using residual plots, which did not reveal major violations.

Three nested linear regression models were specified a priori. Model I provided unadjusted estimates of the association between high lateral position (HLP vs. non-HLP) and antibiotic exposure duration without controlling for any covariates. Model II additionally adjusted for demographic variables (age and sex). Model III further incorporated covariates that were judged clinically relevant beforehand and showed at least a modest association with antibiotic exposure in univariable analyses. Multicollinearity among candidate covariates was assessed using variance inflation factors (VIFs). When both arterial PaO₂ and the PaO₂/FiO₂ (P/F) ratio measured on day 7 were entered simultaneously, the two oxygenation indices exhibited pronounced collinearity (VIFs 19.21 and 22.49, respectively), whereas all other covariates had VIFs < 2. Because the P/F ratio better reflects oxygenation under varying FiO₂ conditions, day-7 PaO₂ was removed to avoid redundancy and only the P/F ratio was retained. Consequently, the final Model III included HLP and five covariates—age, sex, COPD, PaO₂ on day 1, and the P/F ratio on day 7—with all VIFs < 2, indicating low collinearity. Statistical significance was set at two-sided p ≤ 0.05. Analyses were performed with R 3.3.2 and Free Statistics 1.9.2.

Results

Cohort characteristics and clinical outcomes

A total of 138 sTBI patients were finally included in this study. Among them, 82.6% (114/138) were male and 17.4% (24/138) were female, with a mean age of 56.8 ± 16.5 years. The main comorbidities included: epidural hematoma (51.4%), basilar skull fracture (50.7%), subdural hematoma (38.4%), skull fracture (34.1%), and subarachnoid hemorrhage (21.7%). The distribution of intracranial injury combinations is detailed in Supplementary Figure S1. Baseline characteristics did not differ significantly between groups (Table 1), and there was no statistically significant difference in age between the HLP group (n = 45) and the non-HLP group (n = 93) (59.7 ± 15.5 vs. 55.4 ± 16.8 years, p = 0.15). However, some variables showed numerically higher values in the HLP group, so a degree of residual clinical imbalance cannot be excluded.

Table 1

| Variables | Total (n = 138) |

sTBI patients | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-HLP group n = 93 | HLP group n = 45 | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 114 (82.6) | 77 (82.8) | 37 (82.2) | 0.934 |

| Female | 24 (17.4) | 16 (17.2) | 8 (17.8) | |

| Age, years | 56.8 ± 16.5 | 55.4 ± 16.8 | 59.7 ± 15.5 | 0.151 |

| Epidural hematoma, n (%) | 71 (51.4) | 48 (51.6) | 23 (51.1) | 0.956 |

| Subdural hematoma, n (%) | 53 (38.4) | 37 (39.8) | 16 (35.6) | 0.632 |

| Basal fracture, n (%) | 70 (50.7) | 48 (51.6) | 22 (48.9) | 0.764 |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage, n (%) | 30 (21.7) | 21 (22.6) | 9 (20) | 0.730 |

| Calvarial fractures, n (%) | 47 (34.1) | 30 (32.3) | 17 (37.8) | 0.521 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 27 (19.6) | 20 (21.5) | 7 (15.6) | 0.409 |

| IHD, n (%) | 4 (2.9) | 2 (2.2) | 2 (4.4) | 0.596 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 52 (37.7) | 32 (34.4) | 20 (44.4) | 0.254 |

| COPD, n (%) | 7 (5.1) | 6 (6.5) | 1 (2.2) | 0.427 |

| CHD, n (%) | 7 (5.1) | 5 (5.4) | 2 (4.4) | 1.000 |

| MAP (mmHg) | 86.2 ± 16.9 | 86.8 ± 17.3 | 84.8 ± 16.0 | 0.501 |

| ICP (mmHg) | 11 (9, 14) | 11 (9, 14) | 11 (8, 14) | 0.943 |

| CPP (mmHg) | 76 (64, 86) | 78 (65, 86) | 72 (64, 86) | 0.516 |

| Vasoactive drugs, n (%) | 62 (44.9) | 41 (44.1) | 21 (46.7) | 0.775 |

| GCS score | 5.0 ± 1.9 | 5.2 ± 2.0 | 4.7 ± 1.6 | 0.167 |

| APACHE II, score | 30.7 ± 7.9 | 30.4 ± 8.5 | 31.3 ± 6.4 | 0.549 |

| SOFA, score | 12.0 ± 3.4 | 11.8 ± 3.8 | 12.4 ± 2.2 | 0.331 |

| RASS, score | −3.6 ± 0.7 | −3.5 ± 0.8 | −3.7 ± 0.5 | 0.088 |

| pH day 1 | 7.4 ± 0.1 | 7.4 ± 0.1 | 7.4 ± 0.1 | 0.895 |

| PaCO₂ day 1 | 42.9 ± 7.6 | 43.3 ± 8.0 | 42.0 ± 6.7 | 0.336 |

| PaO₂ day 1 | 131.2 ± 47.1 | 132.9 ± 50.2 | 127.6 ± 40.0 | 0.536 |

| P/F day 1 | 286.1 ± 118.1 | 292.5 ± 125.5 | 273.0 ± 101.3 | 0.364 |

| PCT day 1 | 1.2 (0.7, 3.0) | 1.3 (0.8, 3.0) | 1.0 (0.5, 2.5) | 0.171 |

| WBC day 1 | 14.0 ± 4.2 | 13.7 ± 3.3 | 14.5 ± 5.6 | 0.261 |

| pH day 7 | 7.4 ± 0.1 | 7.4 ± 0.1 | 7.4 ± 0.1 | 0.945 |

| PaCO₂ day 7 | 41.9 ± 8.4 | 43.1 ± 9.7 | 39.5 ± 3.9 | 0.018 |

| PaO₂ day 7 | 157.6 ± 49.3 | 153.5 ± 49.9 | 166.2 ± 47.5 | 0.158 |

| P/F day 7 | 349.3 ± 103.6 | 342.0 ± 106.8 | 364.4 ± 96.2 | 0.235 |

| PCT day 7 | 0.4 (0.2, 1.2) | 0.5 (0.2, 1.3) | 0.2 (0.1, 0.5) | 0.010 |

| WBC day 7 | 11.3 ± 3.8 | 12.0 ± 3.8 | 10.0 ± 3.5 | 0.004 |

| 28-day mortality, n (%) | 21 (15.2) | 17 (18.3) | 4 (8.9) | 0.150 |

| Mechanical ventilation, days | 8.0 (6.0, 10.8) | 9.0 (7.0, 11.0) | 7.0 (5.0, 8.0) | 0.004 |

| Length of ICU stay | 12.1 ± 5.7 | 12.6 ± 6.1 | 11.0 ± 4.8 | 0.135 |

| Duration of antibiotic exposure | 11.5 ± 5.6 | 12.4 ± 6.1 | 9.5 ± 4.0 | 0.004 |

| Tracheostomy, n (%) | 22 (15.9) | 19 (20.4) | 3 (6.7) | 0.038 |

Baseline characteristics and outcomes.

IHD: Ischemic Heart Disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CHD: coronary heart disease; MAP: mean arterial pressure; ICP: intracranial pressure; CPP: cerebral perfusion pressure; GCS: Glasgow coma scale; APACHE II: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score; SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; RASS: Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale; PaCO2: Partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood; PaO2: Partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood; P/F: PaO2/FiO2; PCT: procalcitonin; WBC: white blood cell count; ICU: intensive care unit.

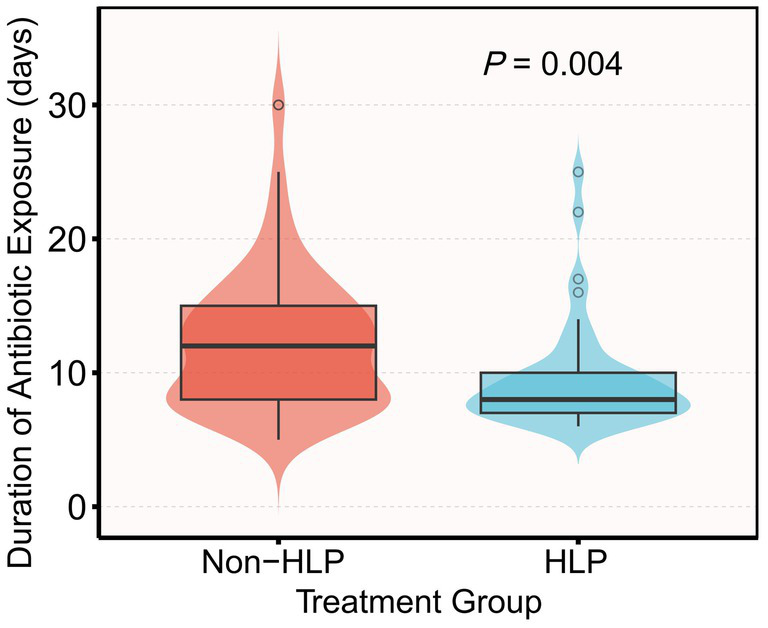

Pre-intervention physiological profiles did not show statistically significant differences between groups (Table 1). Median ICP was 11 mmHg in both groups (IQR 8–14 vs. 9–14; p = 0.94), and CPP medians were 72 (64–86) vs. 78 (65–86) mmHg (p = 0.52); other oxygenation, ventilation, and circulatory indices showed no material imbalances. On day 7, the HLP group had significantly lower PaCO₂, procalcitonin (PCT), and white blood cell (WBC) levels, fewer days of mechanical ventilation, a shorter duration of antibiotic exposure, and a lower tracheostomy rate compared with the non-HLP group (all p < 0.05; Table 1 and Figure 3).

Figure 3

Violin and box plots of antibiotic exposure duration by group (HLP vs. non-HLP). Mean antibiotic exposure was 12.4 ± 6.1 days in the non-HLP group and 9.5 ± 4.0 days in the HLP group (mean difference −2.9 days; p = 0.004 by Mann–Whitney U test).

Regarding safety, 2 cases (4.4%) in the HLP group were prematurely terminated due to triggering the predefined stopping criteria: 1 case with ICP > 25 mmHg for ≥5 min and 1 case with MAP decrease >20% combined with hypoxia. In the non-HLP group, 4 cases (4.3%) experienced similar events (2 cases with elevated ICP, 1 case with MAP decrease, and 1 case with new-onset arrhythmia). There was no statistically significant difference in event occurrence rates between the two groups (Fisher’s exact test, OR = 1.03, 95% CI 0.18–5.87, p = 1.000). Given the very low event counts, confidence intervals around these estimates are wide, and the analysis is underpowered to rule out small to moderate differences; therefore, the safety results should be viewed as descriptive (Supplementary Tables S2, S3).

Factors associated with antibiotic exposure

We then examined factors associated with the duration of antibiotic exposure using univariable and multivariable linear regression models. The results of univariate analysis showed that ICP and CPP before intervention were not significantly linearly correlated with the duration of antibiotic exposure (both p > 0.80). Protective factors included HLP (β = −2.93; 95% CI, −4.90 to −0.96; p = 0.004), PaO₂ on day 1 (β = −0.02; 95% CI, −0.04 to 0; p = 0.039), PaO₂ on day 7 (β = −0.02; 95% CI, −0.04 to 0; p = 0.018), and P/F ratio on day 7 (β = −0.01; 95% CI, −0.02 to 0; p = 0.011), indicating that better oxygenation was associated with shorter antibiotic exposure. Conversely, COPD (β = 9.72; 95% CI, 5.71 to 13.74; p < 0.001) and days of mechanical ventilation (β = 1.03; 95% CI, 0.92 to 1.14; p < 0.001) were associated with longer antibiotic exposure (Table 2).

Table 2

| Covariate | β (95%CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| High lateral position | −2.93 (−4.9,-0.96) | 0.004 |

| Gender | −0.07 (−2.58,2.45) | 0.957 |

| Age, per 1 year | 0.04 (−0.01,0.10) | 0.128 |

| Epidural hematoma | 1.67 (−0.22,3.55) | 0.082 |

| Subdural hematoma | 0.99 (−0.96,2.94) | 0.318 |

| Basal fracture | 1.04 (−0.85,2.94) | 0.278 |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 0.4 (−1.91,2.71) | 0.731 |

| Calvarial fractures | 0.07 (−1.94,2.08) | 0.945 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.56 (−0.83,3.95) | 0.198 |

| IHD | 0.79 (−4.89,6.46) | 0.784 |

| Hypertension | 1.07 (−0.89,3.03) | 0.281 |

| COPD | 9.72 (5.71,13.74) | < 0.001 |

| CHD | 1.44 (−2.89,5.78) | 0.511 |

| MAP | 0 (−0.05,0.06) | 0.944 |

| ICP | 0.03 (−0.26, 0.28) | 0.834 |

| CPP | 0 (−0.05,0.06) | 0.981 |

| Vasoactive drugs | 0.85 (−1.06,2.76) | 0.382 |

| GCS score | 0.1 (−0.4,0.61) | 0.685 |

| APACHE II score | −0.07 (−0.19,0.05) | 0.265 |

| SOFA score | −0.03 (−0.32,0.25) | 0.819 |

| RASS score | 0.58 (−0.78,1.94) | 0.398 |

| PH day 1 | 0.02 (−1.04,1.07) | 0.975 |

| PaCO2 day 1 | −0.01 (−0.13,0.12) | 0.913 |

| PaO₂ day 1 | −0.02 (−0.04,0.00) | 0.039 |

| P/F day 1 | −0.01 (−0.01,0.00) | 0.199 |

| PCT day 1 | 0.04 (−0.06,0.14) | 0.395 |

| WBC day 1 | −0.15 (−0.38,0.07) | 0.179 |

| PH day 7 | 0.98 (−0.12,2.09) | 0.080 |

| PaCO2 day 7 | −0.04 (−0.15,0.07) | 0.483 |

| PaO2 day 7 | −0.02 (−0.04,0.00) | 0.018 |

| P/F day 7 | −0.01 (−0.02, 0.00) | 0.011 |

| PCT day 7 | −0.03 (−0.13,0.08) | 0.579 |

| WBC day 7 | −0.11 (−0.36,0.14) | 0.396 |

Univariate analysis for duration of antibiotic exposure.

Continuous covariates are modeled per unit increase unless otherwise specified. β coefficients represent the change in antibiotic exposure days per unit increase in the covariate; 95% CIs are shown in parentheses. p values are two-sided. Abbreviation: IHD: Ischemic Heart Disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CHD: coronary heart disease; MAP: mean arterial pressure; ICP: Intracranial Pressure; CPP: Cerebral Perfusion Pressure; GCS: Glasgow coma scale; APACHE II: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score; SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; RASS: Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale; PaCO2: Partial pressure of carbon dioxide in artery blood; PaO2: Partial pressure of oxygen in artery blood; P/F: PaO2/FiO2; PCT: procalcitonin; WBC: white blood count; ICU: intensive care unit.

Multivariable models

Model I (without adjusting for any covariates) showed that HLP (β = −2.93; 95% CI -4.9 to −0.96; p = 0.004), PaO₂ on day 1 (β = −0.21; 95% CI -0.41 to −0.01; p = 0.039), and P/F ratio on day 7 (β = −0.12; 95% CI -0.21 to −0.03; p = 0.011) were each associated with shorter antibiotic exposure in univariable analysis. COPD (β = 9.72; 95% CI 5.71 to 13.74; p < 0.001) was a significant risk factor.

Model II (adjusted for age and gender): HLP (β = −3.17; 95% CI, −5.13 to −1.22; p = 0.002) and P/F ratio on day 7 (β = −0.11; 95% CI, −0.2 to −0.01; p = 0.027) remained protective factors. COPD (β = 9.69; 95% CI, 5.43 to 13.94; p < 0.001) remained a significant risk factor.

Model III (further adjusted for age, gender, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, PaO₂ value on day 1, and P/F value on day 7): HLP (β = −2.58; 95% CI –4.44 to −0.71; p = 0.008) remained a protective factor for antibiotic exposure duration in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (β = 8.78; 95% CI, 4.42 to 13.13; p < 0.001) remained a significant risk factor for antibiotic exposure duration in patients with severe traumatic brain injury (see Table 3).

Table 3

| Model I | Model II | Model III | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95%CI) | P-value | β (95%CI) | P-value | β (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age | ||||||

| Per 10 | 0.45 (−0.13,1.02) | 0.128 | 0.45 (−0.13,1.03) | 0.128 | 0.45 (−0.13,1.03) | 0.128 |

| <65 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| ≥65 | 2.26 (0.29,4.24) | 0.025 | 2.75 (−0.44,5.95) | 0.094 | 2.75 (−0.44,5.95) | 0.094 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | −0.07 (−2.58,2.45) | 0.957 | ||||

| Female | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| HLP | ||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Yes | −2.93 (−4.9,–0.96) | 0.004 | −3.17 (−5.13,–1.22) | 0.002 | −2.58 (−4.44,–0.71) | 0.008 |

| COPD | ||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Yes | 9.72 (5.71,13.74) | <0.001 | 9.69 (5.43,13.94) | <0.001 | 8.78 (4.42,13.13) | <0.001 |

| PaO₂ day 1 (per 10) | −0.21 (−0.41,–0.01) | 0.039 | −0.18 (−0.39,0.04) | 0.115 | −0.09 (−0.33,0.14) | 0.445 |

| P/F Day 7 (per 10) | −0.12 (−0.21,–0.03) | 0.011 | −0.11 (−0.2,–0.01) | 0.027 | −0.09 (−0.19,0.01) | 0.084 |

Multivariate analyses of risk factors associated with duration of antibiotic exposure.

Data presented are β and 95% CIs. β (days) with 95% CI from linear regression; two-sided P-values. Model I: Did not adjust any covariates. Model II: Adjusted age, gender. Model III: Adjusted age, gender, COPD, PaO2 Day 1, P/F Day 7. Abbreviation: HLP: High Lateral Position; COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; PaO2: Partial pressure of oxygen in artery blood; P/F: PaO2/FiO2; Per 10: denotes the linear effect on the outcome (days) for every 10-unit increase in the independent variable.

Discussion

This single-center retrospective cohort observed an association between high lateral positioning (HLP) and a shorter duration of antimicrobial exposure, along with trends toward fewer days of mechanical ventilation and a lower tracheostomy rate. These endpoints were not prespecified and were examined as exploratory post-hoc analyses; the study was not powered for them and no adjustment for multiple comparisons was performed, so these observations should be interpreted with caution.

From a physiological perspective, combining a modest head-up tilt (approximately 15–30°) with a 90° lateral position may better preserve relative stability of ICP/CPP through favorable extracranial venous return and intrathoracic pressure gradients. Concurrently, gravity may facilitate secretion drainage and improve ventilation–perfusion matching, thereby accelerating infection control and shortening the course of antimicrobial therapy. If HLP is indeed associated with reduced antimicrobial exposure, direct drug costs and related supportive-care expenditures could theoretically be reduced, consistent with prior estimates of the economic burden associated with antibiotic resistance and prolonged antibiotic treatment (26). However, such economic effects are highly context-dependent across institutions and pricing structures, and no formal economic evaluation was performed in this study. Prospective work using micro-costing and cost-effectiveness or cost-utility analyses will be needed to quantify and verify these signals.

Under the retrospective design framework, we attempted to mitigate the selection bias that “more stable patients are more likely to receive HLP” by systematically collecting immediate data before the first HLP session, with corresponding data extracted at the same disease-course node in the non-HLP group. There were no systematic differences in ICP, CPP, sedation depth, intensity of care, fluid balance, or microbial resistance patterns between groups (all p > 0.05), suggesting broadly comparable pre-intervention physiological profiles. Nonetheless, these strategies can only partially address confounding, and unmeasured factors such as subtle differences in disease trajectory or team preferences may still have influenced HLP assignment. As a result, the observed associations should be interpreted cautiously as hypothesis-generating and require confirmation in randomized controlled trials.

In terms of safety and feasibility, the premature termination rate in the HLP group was 4.4%, with a median daily cumulative implementation of 10.0 (10.0–12.0) h and a target achievement rate of 95.6%. The non-HLP group also recorded 4 cases (4.3%) of similar events, with no statistically significant difference between the two groups (p = 1.000). No adverse events such as catheter dislodgement or pressure ulcers occurred throughout the study. The above data suggest that under high-level monitoring and standardized procedures, HLP is well-tolerated in the short term, with risk signals no higher than those of routine position management.

Although the 28-day mortality rate in the HLP group was numerically lower than that in the non-HLP group (8.9% vs. 18.3%), the difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.150). In sTBI, death is more often dominated by the severity of neurotrauma, intracranial lesions, and secondary brain injury (27). Systematic evidence in the field of critical care indicates that improving pulmonary intermediate endpoints such as oxygenation alone does not necessarily translate into mortality benefits, reinforcing the uncertainty of translating intermediate endpoints into hard outcomes (28). This evidence is consistent with the phenomenon observed in our study, where pulmonary indicators improved but short-term mortality did not significantly decrease. Therefore, we cautiously interpret the mortality results as hypothesis-generating: The potential benefits of HLP are more likely to be reflected in the control of complications and resource utilization rather than short-term survival.

In sTBI, depression of the respiratory drive, sedation, and mechanical ventilation can impair mucociliary clearance and cough reflex, leading to secretion retention and a vicious cycle of “infection–inflammation–reinfection,” thereby prolonging ICU length of stay (29). Under gravitational influence, HLP may promote secretions from upper-lobe bronchi to drain into larger airways and improve ventilation–perfusion matching, reducing the risks of mucus accumulation, atelectasis, and infection; the observed decline in PaCO₂ on day 7 (p < 0.05) in this study is consistent with this direction of effect (30–32). In addition, a high lateral position can expand chest-wall excursion and optimize diaphragmatic–abdominal muscle synergy, increasing peak expiratory flow and facilitating sputum clearance (33). These mechanistic clues provide a physiologically plausible backdrop for the directional associations observed here.

We also found that concomitant COPD was consistently associated with longer antibiotic exposure (β = 8.78, p < 0.001). This is biologically plausible, as COPD is characterized by chronic airway inflammation, airflow limitation, and structural changes such as small airway disease and emphysema, which are strongly linked to future exacerbations and recurrent lower respiratory events (34, 35). These exacerbations are frequently infection-driven and commonly managed with systemic antibiotics, so patients with COPD tend to experience a higher cumulative burden of antibiotic-treated episodes over time, particularly in high-risk phenotypes with structural disease (34, 35). In our cohort, HLP was associated with fewer days of mechanical ventilation and reductions in inflammatory markers (PCT ↓ 0.3 ng/mL, WBC ↓ 2.0 × 10 (9)/L), suggesting a potential role as a non-pharmacological adjunct to short-course antibiotic strategies, in line with evidence supporting shorter antibiotic courses in appropriately selected critically ill patients (36). However, these observations remain hypothesis-generating and require validation through randomized trials and stratified subgroup analyses in patients with COPD.

In summary, HLP was consistently associated with a shorter duration of antimicrobial exposure in this study and showed several favorable directional signals. Given design limitations, multicenter randomized controlled trials are warranted, incorporating standardized and quantified comparator SOPs, structured safety endpoints, and standardized antibiotic discontinuation pathways, while evaluating both intermediate pulmonary outcomes and patient-centered hard endpoints to test the effectiveness, safety, and generalizability of HLP.

Conclusion

In this retrospective cohort, HLP was associated with a shorter duration of antibiotic exposure and showed trends toward fewer days of mechanical ventilation and a lower tracheostomy rate. Given the nonrandomized, single-center design and potential residual confounding, these findings are exploratory and should be confirmed in prospective randomized studies. Future randomized controlled trials should incorporate standardized ventilation and positioning protocols, predefined safety stopping criteria, and quantitative measures of secretion clearance and pulmonary mechanics to more definitively evaluate the causal effects of HLP on antibiotic exposure and clinically important outcomes.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Shengli Clinical Medical College of Fujian Medical University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

ZL: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Conceptualization. DC: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Project administration. MY: Data curation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. XW: Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. LQ: Data curation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. LH: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by the Scientific Foundation of Fujian Health Department (Grant No. 2020QNB006), the Startup Fund for Scientific Research, Fujian Medical University (Grant No. 2020QH1139 and 2021QH1285), the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (No. 2024J011028), and the Joint Funds for the Innovation of Science and Technology, Fujian Province (No. 2024Y9069).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Fujian Provincial Hospital’s intensive care units staff for their support and guidance in performing this study. Additionally, we gratefully thank the Free Statistics team (Beijing, China) for providing technical assistance and practical data analysis and visualization tools.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2025.1665953/full#supplementary-material

- HLP

High Lateral Position

- COPD

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- sTBI

Severe Traumatic Brain Injury

- TBI

Traumatic Brain Injury

- PP

prone positioning

- APACHE II

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score

- GCS

Glasgow coma scale

- ICU

intensive care unit

- PCT

procalcitonin

- SOFA

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- ICP

Intracranial Pressure

- CPP

Cerebral Perfusion Pressure

- RASS

Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale

- P/F

PaO2/FiO2

- WBC

White Blood Cell Count

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- CHD

coronary heart disease

- CI

confidence intervals

- IQR

interquartile range

- PEF

Peak Expiratory Flow

- SOP

Standard Operating Procedure

- ASP

Antimicrobial Stewardship Program

Glossary

References

1.

Max JE Troyer EA Arif H Vaida F Wilde EA Bigler ED et al . Traumatic brain injury in children and adolescents: psychiatric disorders 24 years later. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2022) 34:60–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.20050104,

2.

Jiang J-Y Gao GY Feng JF Mao Q Chen LG Yang XF et al . Traumatic brain injury in China. Lancet Neurol. (2019) 18:286–95. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30469-1,

3.

Coritsidis G Diamond N Rahman A Solodnik P Lawrence K Rhazouani S et al . Hypertonic saline infusion in traumatic brain injury increases the incidence of pulmonary infection. J Clin Neurosci. (2015) 22:1332–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2015.02.025,

4.

Song RR Tao YF Zhu CH Ju ZB Guo YC Ji Y . Effects of nasogastric and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube feeding on the susceptibility of pulmonary infection in long-term coma patients with stroke or traumatic brain injury. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. (2018) 98:3936–40. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0376-2491.2018.48.006,

5.

McIlwaine M Bradley J Elborn JS Moran F . Personalising airway clearance in chronic lung disease. Eur Respir Rev. (2017) 26:160086. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0086-2016,

6.

Seder DB . Tracheostomy practices in Neurocritical care. Neurocrit Care. (2019) 30:555–6. doi: 10.1007/s12028-019-00706-7,

7.

Bösel J . Who is safe to Extubate in the neuroscience intensive care unit?Semin Respir Crit Care Med. (2017) 38:830–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1608773,

8.

Lee AL Burge AT Holland AE . Airway clearance techniques for bronchiectasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2015) 2015:CD008351. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008351.pub3,

9.

Guérin C Reignier J Richard JC Beuret P Gacouin A Boulain T et al . Prone positioning in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. (2013) 368:2159–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214103,

10.

Gattinoni L Busana M Giosa L Macrì MM Quintel M . Prone positioning in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. (2019) 40:94–100. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1685180,

11.

Does prone positioning increase intracranial pressure? A retrospective analysis of patients with acute brain injury and acute respiratory failure - PubMed. Available online at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24985500/ (Accessed December 11, 2025).

12.

Prone position in mechanically ventilated patients with reduced intracranial compliance - PubMed. Available online at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16923087/ (Accessed December 11, 2025).

13.

The prone position must accommodate changes in IAP in traumatic brain injury patients - PubMed. Available online at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33827641/ (Accessed December 11, 2025).

14.

Mechanical ventilation in patients with acute brain injury: recommendations of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine consensus - PubMed. Available online at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33175276/ (Accessed December 11, 2025).

15.

Walter T Zucman N Mullaert J Thiry I Gernez C Roux D et al . Extended prone positioning duration for COVID-19-related ARDS: benefits and detriments. Crit Care. (2022) 26:208. doi: 10.1186/s13054-022-04081-2

16.

Challoner T Vesel T Dosanjh A Kok K . The risk of pressure ulcers in a proned COVID population. Surgeon. (2022) 20:e144–8. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2021.07.001,

17.

Uğraş GA Yüksel S Temiz Z Eroğlu S Şirin K Turan Y . Effects of different head-of-bed elevations and body positions on intracranial pressure and cerebral perfusion pressure in neurosurgical patients. J Neurosci Nurs. (2018) 50:247–51. doi: 10.1097/JNN.0000000000000386

18.

Alarcon JD Rubiano AM Okonkwo DO Alarcón J Martinez-Zapata MJ Urrútia G et al . Elevation of the head during intensive care management in people with severe traumatic brain injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2017) 12:CD009986. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009986.pub2

19.

Simka M Czaja J Kowalczyk D . Collapsibility of the internal jugular veins in the lateral decubitus body position: a potential protective role of the cerebral venous outflow against neurodegeneration. Med Hypotheses. (2019) 133:109397. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2019.109397,

20.

Siswanto S Utama OS Adistyawan G Sujalmo P GPD Tunggadewi Shafa PN et al . The physiological effect of prone positioning and lateral decubitus in non-intubated patients with severe COVID-19: a prospective cohort study. Annal Med Surg. (2023) 85:5359–64. doi: 10.1097/MS9.0000000000001317

21.

Lulla A Lumba-Brown A Totten AM Maher PJ Badjatia N Bell R et al . Prehospital guidelines for the management of traumatic brain injury - 3rd edition. Prehosp Emerg Care. (2023) 27:507–38. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2023.2187905,

22.

Schaller SJ Scheffenbichler FT Bein T Blobner M Grunow JJ Hamsen U et al . Guideline on positioning and early mobilisation in the critically ill by an expert panel. Intensive Care Med. (2024) 50:1211–27. doi: 10.1007/s00134-024-07532-2,

23.

de Jong E van Oers JA Beishuizen A Vos P Vermeijden WJ Haas LE et al . Efficacy and safety of procalcitonin guidance in reducing the duration of antibiotic treatment in critically ill patients: a randomised, controlled, open-label trial. Lancet Infect Dis. (2016) 16:819–27. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00053-0

24.

Septimus EJ . Antimicrobial resistance: an antimicrobial/diagnostic stewardship and infection prevention approach. Med Clin North Am. (2018) 102:819–29. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2018.04.005,

25.

Devlin JW Skrobik Y Gélinas C Needham DM Slooter AJC Pandharipande PP et al . Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and Management of Pain, agitation/sedation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption in adult patients in the ICU. Crit Care Med. (2018) 46:e825–73. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003299,

26.

Zhen X Stålsby Lundborg C Sun X Zhu N Gu S Dong H . Economic burden of antibiotic resistance in China: a national level estimate for inpatients. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. (2021) 10:5. doi: 10.1186/s13756-020-00872-w,

27.

Hawryluk GWJ Rubiano AM Totten AM O’Reilly C Ullman JS Bratton SL et al . Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: 2020 update of the Decompressive Craniectomy recommendations. Neurosurgery. (2020) 87:427–34. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyaa278,

28.

Cao L Chen Q Xiang YY Xiao C Tan YT Li H . Effects of oxygenation targets on mortality in critically ill patients in intensive care units: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. (2024) 139:734–42. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000006859,

29.

Pieterse A Hanekom SD . Criteria for enhancing mucus transport: a systematic scoping review. Multidiscip Respir Med. (2018) 13:22. doi: 10.1186/s40248-018-0127-6,

30.

Leelarungrayub J Eungpinichpong W Klaphajone J Prasannarong M Boontha K . Effects of manual percussion during postural drainage on lung volumes and metabolic status in healthy subjects. J Bodyw Mov Ther. (2016) 20:356–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2015.11.002,

31.

Chechenin MG Voevodin SV Pronichev EI Shuliveĭstrov IV . Kinetic therapy for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Anesteziol Reanimatol. (2004) 8–12.

32.

Wang Q-Y Zhou Y Wang M-R Jiao Y-Y . Effects of starting one lung ventilation and applying individualized PEEP right after patients are placed in lateral decubitus position on intraoperative oxygenation for patients undergoing thoracoscopic pulmonary lobectomy: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. (2024) 25:500. doi: 10.1186/s13063-024-08347-8,

33.

Chong Y Nan C Mu W Wang C Zhao M Yu K . Effects of prone and lateral positioning alternate in high-flow nasal cannula patients with severe COVID-19. Crit Care. (2022) 26:28. doi: 10.1186/s13054-022-03897-2,

34.

Maselli DJ Yen A Wang W Okajima Y Dolliver WR Mercugliano C et al . Small airway disease and emphysema are associated with future exacerbations in smokers with CT-derived bronchiectasis and COPD: results from the COPDGene cohort. Radiology. (2021) 300:706–14. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021204052,

35.

Bhatt SP Agusti A Bafadhel M Christenson SA Bon J Donaldson GC et al . Phenotypes, Etiotypes, and Endotypes of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2023) 208:1026–41. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202209-1748SO,

36.

Kubo K Kondo Y Yoshimura J Kikutani K Shime N . Short- versus prolonged-course antibiotic therapy for sepsis or infectious diseases in critically ill adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Dis (Lond). (2022) 54:213–23. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2021.2001046,

Summary

Keywords

antibiotic exposure, aspiration pneumonia, high lateral position, neurocritical care, severe traumatic brain injury

Citation

Lin Z, Chen D, Ye M, Wang X, Qiu L and Huang L (2026) The effect of high lateral position on antibiotic exposure duration in patients with severe traumatic brain injury: a retrospective observational cohort study. Front. Med. 12:1665953. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1665953

Received

14 July 2025

Revised

04 December 2025

Accepted

08 December 2025

Published

05 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Jian-cang Zhou, Zhejiang University, China

Reviewed by

Muhammad Ashir Shafique, Jinnah Post Graduate Medical Centre, Pakistan

Wagner Malago Tavares, Ana Rosa Health Group, Brazil

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Lin, Chen, Ye, Wang, Qiu and Huang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Long Huang, huanglong1988@fjmu.edu.cn; Liman Qiu, liman0280@163.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

‡These authors have contributed equally to this work and share last authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.