Abstract

Rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis (ROCM) is a rapidly progressing and life-threatening fungal infection caused by fungi in the order Mucorales. It predominantly affects immunocompromised individuals, such as those undergoing chemotherapy for hematological malignancies. Despite its high mortality rate, ROCM remains underrecognized, and its clinical features in patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+) mixed phenotype acute leukemia (MPAL) are rarely reported. This report describes a 48-year-old female who presented with a one-week history of fever without localized pain and was diagnosed with Ph+ MPAL by laboratory blood tests and comprehensive bone marrow examination. She was treated with imatinib and received acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)-like chemotherapy, and used voriconazole to prevent fungal infections. On day 9 of admission, the patient developed fever and skin lesions on the right nasal area. The skin lesions spread rapidly, indicating a potentially aggressive infection. A pathological biopsy of the affected area confirmed the diagnosis of ROCM. We administered liposomal amphotericin B (L-AmB) in a timely manner and effectively controlled the infection. The most common fungal infections in Ph+ MPAL are Candida and Aspergillus. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of ROCM. Our case reports support the limitations of voriconazole in preventing Mucorales infections and emphasizes the importance of broad coverage in antifungal prevention strategies, early diagnosis, and timely treatment. In addition, we reviewed 27 other cases of rhinocerebral mucormycosis in patients with acute leukemia and provide an analysis of these cases.

1 Introduction

Mucormycosis is a globally invasive fungal infection caused by members of the genera Mucor, Rhizopus, Rhizomucor, and Lichtheimia (formerly Absidia) in the order Mucorales (1). Mucormycosis rarely occurs in immunocompetent individuals but frequently occurs in immunocompromised patients (2). The incidence of mucormycosis has been increasing over the past decade, especially since the onset of COVID-19, and the condition is fatal in most patients (3, 4). Mucormycosis can present in different forms, including pulmonary, cutaneous, rhino-orbito-cerebral, gastrointestinal, and disseminated types (5). In the clinical situations, diabetes mellitus has evolved as a major risk factor for mucormycosis, while in more recent years, underlying malignancy has emerged as a critical risk factor due to the increasing number of patients undergoing chemotherapy or cancer immunotherapy (6–8).

A number of retrospective studies have shown that mucormycosis accounts for only a small proportion of breakthrough invasive fungal infection in patients with hematological malignancies (9). According to the SEIFEM study, mucormycosis is present in only 0.1% of patients with hematological malignancies (10), with pulmonary mucormycosis being the most common (11, 12). Biopsy is the preferred method for mucormycosis diagnosis but may not be an option in the early course of the disease, resulting in delayed diagnosis and missed opportunities for timely treatment (13). Antifungal therapy is usually used clinically, but it is usually difficult to treat infections effectively by drugs. Combined surgical debridement can improve the treatment effect and patient survival rate (14, 15).

Herein, we report a case of Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+) mixed phenotype acute leukemia (MPAL) combined with rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis (ROCM) infection, with the timely use of liposomal amphotericin B (L-AmB) to treat and control the infection. Highlighting the importance of early diagnosis and treatment of mucormycosis, it also provides important insights into the selection of prophylactic therapy for patients with hematological malignancies.

2 Case description

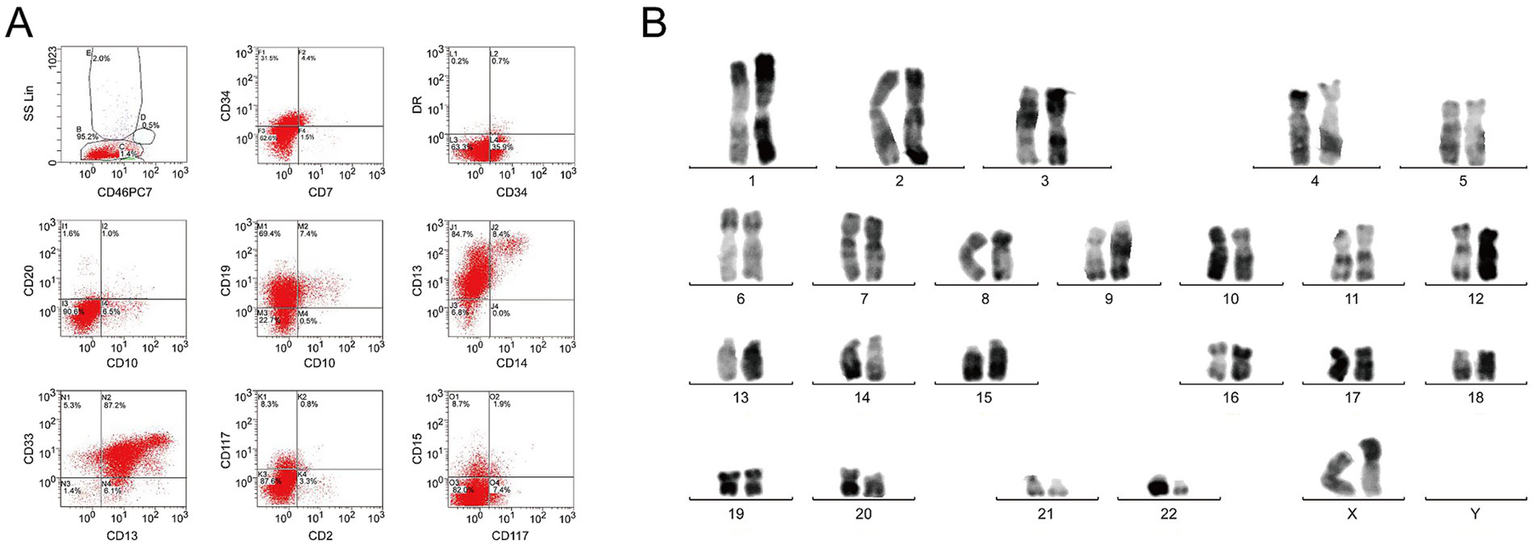

A 48-year-old woman who presented with fever in the absence of pain for 1 week was admitted to People’s Hospital of Xinghua City (Jiangsu Province, China). Physical examination was negative. Blood routine test demonstrated a white blood cell count (WBC) of 180.7 (4.0–10.0) × 109/L; hemoglobin of 123 (110–150) g/L and platelets of 53 (100–300) × 109/L. Bone marrow biopsy showed hypercellularity with 83.5% blast cells. Eosinophilia was not evident in either peripheral blood or bone marrow. Flow cytometry analysis showed that the blast cells, which accounted for 95.2% of bone marrow karyocytes, were strongly positive for CD34, CD19, CD13, CD33, CD11b, CD64, myeloperoxidase, and CD79a (Figure 1A). According to the World Health Organization (WHO) 2022 criteria, the patient was diagnosed with MPAL with co-expression of myeloid and B lymphoid lineage antigen. The chromosomal analysis of bone marrow cells revealed t(9;22) (q34;q11) translocation (Figure 1B). Molecular genetics showed BCR/ABL (e1a2) fusion gene, thereby confirming the diagnosis of Ph+ MPAL.

Figure 1

Immunophenotype and karyotype characteristics of bone marrow specimens. (A) Representative flow cytometry histograms demonstrate the expression of CD34, CD19, CD13, CD33, CD 11b, CD64, and CD79a. (B) G-banding karyotype of the BM cells demonstrates t(9;22) (q34;q11).

The timeline of diagnosis and treatment is shown in Table 1. On the 6th day of admission, the patient was treated with imatinib (400 mg/day) and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)-like chemotherapy (VDP regimen: vincristine 2 mg/qwx4; daunorubicin 30 mg/m2, day 1–3; prednisone 60 mg/m2, day 1–28). Also, preventive treatment was given with voriconazole (4 mg/kg, q12h).

Table 1

| Time | Clinical features | Biology results | Therapy strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Fever | CRP 112.6 mg/L | Hefoperazone/sulbactam 9 g/day IV and hydroxyurea 3 g/day p.o. |

| Day 3 | Bone marrow pathology and fever | MPAL, WBC 136.8 × 109/L | Cyclophos-phamide 0.4 g/day IV, dexamethasone 10 mg/day I, and voriconazole 4 mg/kg, q12h IV |

| Day 6 | Bone marrow pathology and fever | Ph + MPAL, WBC 73.2 × 109/L | Imatinib 400 mg/day, vincristine 2 mg/qwx4, daunorubicin 30 mg/m2 day 1–3, prednisone 60 mg/m2 day 1–28 |

| Day 9 | Fever again, skin lesions on the nasal | WBC 2.51 × 109/L, ANC 0.1 × 109/L, CRP 57.81 mg/L, CT of the chest (−) | Imipenem and cilastatin sodium 1.0 q6hIV, vancomycin 2.0 q12h, voriconazole 4 mg/kg q12h IV |

| Day 15 | Skin lesions expand | Pathology shows mucormycosis, wound secretion culture shows Rhizomucor, (1,3)-β-D-glucan assay (−), galactomannan test (−) | L-AmB at 3 mg/kg qdIV, imipenem and cilastatin sodium 1.0 q6hIV |

| Day 18 | Persistence of fever | WBC 0.30 × 109/L, ANC 0.1 × 109/L | Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor 150 μg bid subcutaneous |

| Day 23 | Bone marrow pathology and persistence of fever | WBC 4.47 × 109/L, ANC 3.5 × 109/L, complete remission | Discharge home |

Timeline of events.

CRP, C-reactive protein; IV, intravenous; p.o., per os; MPAL, mixed phenotype acute leukemia; WBC, white blood cell count; Ph+, Philadelphia chromosome-positive; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; CT, computed tomography; L-AmB, liposomal amphotericin B.

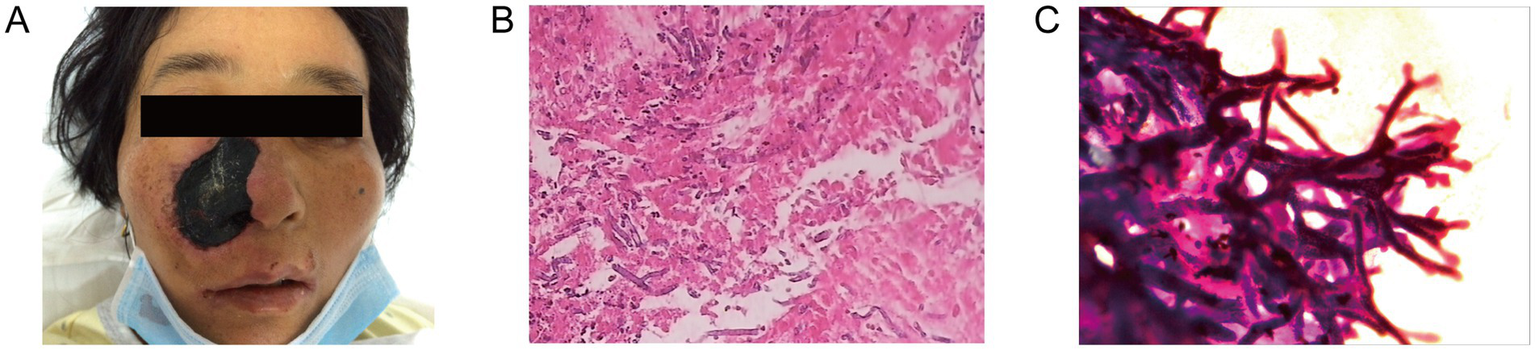

On day 9 after admission, the patient’s body temperature reached 38.6 °C, and developed skin lesions on the right nasal area. The skin lesions spread rapidly to the entire right nasal area after 6 days (Figure 2A). Blood routine test demonstrated WBC 2.51 × 109/L, hemoglobin 80.2 g/L, platelets 18 × 109/L, and absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of 0.1 × 109/L. C-reactive protein (57.81 mg/L) and procalcitonin (0.13 ng/mL) were both elevated. Chest computed tomography (CT) examination was negative, and serum (1,3)-β-D-glucan, galactomannan tests, and blood culture examinations were negative. Skin biopsy revealed hyphae consistent with mucormycosis. Wound secretion culture was positive for Rhizomucor species (Figures 2B,C). After the diagnosis of mucormycosis, according to the guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), we administered L-AmB at 3 mg/kg/day and successfully controlled the infection. On the 23rd day of admission, the patient achieved complete remission of the infection.

Figure 2

Characterization of infected tissues. (A) Initial clinical presentation on the whole right nasal. The skin lesion area is approximately 4 cm × 3 cm. Pathological section of necrotic tissue of right nasal cavity. Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections show an angioinvasive growth of mucormycosis at a magnification of ×100 (B) and ×400 (C).

We suggested bone marrow transplantation as the best option for her treatment, but she refused. The patient died of intracranial hemorrhage after 1 year.

3 Literature review

Because no cases of MPAL infection with mucormycosis have been reported, we searched PubMed using the terms “rhinocerebral mucormycosis,” “acute leukemia” and “case report” and found 44 articles published between 1982 and June 2025. There were 24 eligible case reports, which included complete information on a total of 27 patients (16–39). Information on age, sex, disease type, treatment, and clinical outcomes was collected for these patients (Table 2).

Table 2

| Case reports | Age and sex | Type of disease | Surgical debridement | Therapeutic drugs | Effective remission of the infection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ding et al. (16) | 46/F | AML | Yes | AmB | No |

| Yamamoto et al. (17) | 42/M | AML | Yes | L-AmB, micafungin | Yes |

| Popa et al. (18) | 7/F | ALL | Yes | AmB | Yes |

| Yang et al. (19) | 1/M | ALL | No | AmB, posaconazole | No |

| Yeung et al. (20) | 57/M | AML M5a | No | L-AmB, imipenem, amikacin | No |

| Samanta et al. (21) | 8/M | ALL | Yes | L-AmB | Yes |

| Siriwardena et al. (22) | 35/F | AML | Yes | L-AmB | No |

| Siriwardena et al. (22) | 29/F | AML | Yes | L-AmB, antibiotics | Yes |

| Siriwardena et al. (22) | 42/M | AML | Yes | L-AmB | No |

| Hu et al. (23) | 1/M | ALL | No | L-AmB, voriconazole | No |

| Ojeda-Diezbarroso et al. (24) | 12/F | ALL | Yes | L-AmB, posaconazole | Yes |

| Uraguchi et al. (25) | 70/M | AML M5b | Yes | L-AmB, antibiotics | No |

| Wehl et al. (26) | 1/M | ALL | No | L-AmB, antibiotics | No |

| Mutchnick et al. (27) | 2/M | ALL | Yes | AmB, posaconazole, micafungin | Yes |

| Dworsky et al. (28) | 17/F | BCP-ALL | Yes | L-AmB, micafungin | Yes |

| Gumral et al. (29) | 40/M | ALL | Yes | L-AmB | Yes |

| Raj et al. (30) | 55/M | APL | Yes | L-AmB | Yes |

| Sigera et al. (31) | 19/M | B-ALL | Yes | L-AmB | No |

| Lerchenmüller et al. (32) | 28/M | ALL | Yes | L-AmB | Yes |

| Cofré et al. (33) | 2/F | ALL | Yes | AmB | Yes |

| Ammon et al. (34) | 24/F | AML | No | AmB, flucytosine | Yes |

| Jacobs et al. (35) | 35/F | AML | No | AmB | No |

| Jacobs et al. (35) | 17/M | ALL | No | AmB, echinocandin FK463 | Yes |

| Parkyn et al. (36) | 3/M | BCP-ALL | No | L-AmB | Yes |

| Andreani et al. (37) | 59/M | sAML | Yes | L-AmB, isavuconazole | Yes |

| Funada et al. (38) | 21/M | BCP-ALL | No | AmB | Yes |

| Brusis and Rister (39) | 12/M | ALL | Yes | AmB | Yes |

Case data of 27 acute leukemia patients with rhinocerebral mucormycosis.

F, female; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; AmB, amphotericin B; M, male; L-AmB, liposomal amphotericin B; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML M5a, acute monoblastic leukemia; AML M5b, acute monocytic leukemia; BCP-ALL, B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia; APL, acute promyelocytic leukemia; B-ALL, B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia; sAML, secondary acute myeloid leukemia.

The patients, 18 males and 9 females, were mainly young and middle-aged, with a median age of 21 years (age range: 1–70 years). All patients were treated with amphotericin B (AmB) or L-AmB, and 48% were also treated with other microbicides. Surgical resection proved highly effective in controlling mucormycosis, with only 44% of non-surgical patients successfully controlled the infection, compared with 72% of surgical patients. In our case, the patients’ symptoms were effectively relieved by drug therapy alone. This encouraging result might be attributed to the timely diagnosis of Mucorales infection and the implementation of effective antifungal strategies.

This encouraging result may be attributed to the timely diagnosis at the early stage of Mucor infection.

4 Discussion

In 2022, the WHO classification was updated, but the main criteria for MPAL remained unchanged, except for cases defined by myeloperoxidase alone for the myeloid lineage. A new subcategory of BCR/ABL1-positive MPAL was introduced (40). In this case, the patient’s heightened susceptibility to invasive fungal infections likely arises from a confluence of immune impairments directly linked to both the disease biology and its treatment (41). Specifically relevant to this Ph+ MPAL case, the BCR-ABL1-driven tyrosine kinase activity is known to disrupt neutrophil functional capacities, including chemotaxis, oxidative burst, and phagocytosis (42, 43). Furthermore, the leukemic blasts in MPAL exhibit aberrant differentiation that disrupts normal hematopoiesis, leading to both quantitative and qualitative defects in innate immune cells (44). This intrinsic immune compromise is further exacerbated by intensive induction chemotherapy, particularly anthracycline-based regimens. Anthracyclines (such as daunorubicin) not only cause profound myelosuppression but also induce mucosal barrier injury and impair tissue-resident macrophage function, creating a permissive environment for fungal invasion (45, 46). The combination of these factors—the underlying immune dysfunction from BCR-ABL1 signaling, treatment-related immunosuppression, and mucosal barrier breakdown—creates a perfect storm for opportunistic fungal infections, necessitating robust antifungal prophylaxis strategies.

In hematological oncology regimens, voriconazole is a widely used empirical prophylactic broad-spectrum fungicide that potently inhibits Candida, Aspergillus, Scedosporium, and Fusarium, reducing the risk of invasive fungal infection in immunocompromised patients (47). However, there is evidence that voriconazole inhibition of Aspergillus creates a favourable environment for Mucorales (12, 22), associated with increased mucormycosis, and animal studies have suggested that exposure to voriconazole enhances Mucorales virulence (48). Our case provides a notable exception to the conventional management paradigm of ROCM, which emphasizes the necessity of combined surgical and medical therapy. The successful control of infection with L-AmB monotherapy, in contrast to the high surgical intervention rate observed in the literature review, warrants further analysis. We postulate that this favorable outcome is attributable not merely to the “timely adjustment” of antifungal therapy, but more fundamentally to the exceptionally early stage and superficial localization of the infection at the time of diagnosis. The patient’s initial presentation was limited to cutaneous involvement on the nasal dorsum without clinical or radiological evidence of sinusitis, osteomyelitis, or orbital/central nervous system invasion—a finding corroborated by the negative chest CT. This confined disease extent stands in stark contrast to most reported cases of ROCM in leukemic patients, which typically present with advanced sino-orbital or cerebral involvement necessitating aggressive debridement to remove necrotic, avascular tissue and reduce the fungal burden. According to the IDSA guidelines, L-AmB is strongly recommended as first-line treatment, while intravenous isavuconazole or the delayed-release posaconazole tablets are moderately recommended (49). Among them, posaconazole has emerged as the prophylactic agent of choice due to its reliable activity against Mucorales.

As observed in the current case, ROCM infection usually originates from the paranasal sinuses, with bone destruction and subsequent invasion of the orbit, eye, and brain (50). Unilateral facial edema, proptosis, and palatal or palpebral fistula developing into necrosis may be observed. When invasive fungal infection is suspected, particularly in cases of ROCM involvement, a diagnostic paradigm shift is warranted. Rather than relying on serum biomarkers such as galactomannan testing, which demonstrates poor sensitivity for mucormycosis, immediate tissue-based diagnostic approaches should be prioritized (51). Early and aggressive tissue sampling for histopathological examination, coupled with molecular diagnostics and fungal culture, is crucial for several reasons: (1) it allows definitive identification of Mucorales through characteristic histological features (broad, pauciseptate hyphae with right-angle branching); (2) enables timely differentiation from other invasive molds like Aspergillus; and (3) provides material for antifungal susceptibility testing. This diagnostic strategy is particularly critical in Ph+ MPAL patients, where delayed diagnosis of mucormycosis carries catastrophic consequences due to their profound immunosuppression and the infection’s characteristically aggressive course. This case emphasizes the need for high clinical suspicion in immunocompromised patients.

5 Conclusion

Mucormycosis is a rare but life-threatening infection in immunocompromised patients, particularly those with hematological malignancies. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment with L-AmB are crucial for improving outcomes. This case underscores the importance of vigilant monitoring and tailored antifungal therapy in managing mucormycosis in Ph+ MPAL patients.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of Xinghua City People’s Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article. Written informed consent was obtained from the participant/patient(s) for the publication of this case report.

Author contributions

YZ: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. MH: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. QZ: Resources, Writing – review & editing. JY: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. ZW: Resources, Writing – review & editing. BC: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. JG: Writing – review & editing. FG: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. ZL: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82170158), the Open Project of Jiangsu Biobank of Clinical Resources (TC2022B008).

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the patient and her family for their contribution and support to the study, as well as all the clinicians and nurses involved in the treatment of this patient. We also thank the members of the Department of Pathology, Zhongda Hospital, School of Medicine, Southeast University, Nanjing Jiangsu Province.

Conflict of interest

JG was employed by Dian Diagnostics Group Co., Ltd. FG was employed by Nanjing Dian Diagnostics Group Co., Ltd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

Pham D Howard-Jones AR Sparks R Stefani M Sivalingam V Halliday CL et al . Epidemiology, modern diagnostics, and the management of Mucorales infections. J Fungi. (2023) 9:659. doi: 10.3390/jof9060659

2.

Hussain MK Ahmed S Khan A Siddiqui AJ Khatoon S Jahan S . Mucormycosis: a hidden mystery of fungal infection, possible diagnosis, treatment and development of new therapeutic agents. Eur J Med Chem. (2023) 246:115010. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2022.115010

3.

Sharma A Alam MA Dhoundiyal S Sharma PK . Review on mucormycosis: pathogenesis, epidemiology, microbiology and diagnosis. Infect Disord Drug Targets. (2024) 24:e220823220209. doi: 10.2174/1871526523666230822154407

4.

Lynch JP Fishbein MC Abtin F Zhanel GG . Part 1: Mucormycosis: prevalence, risk factors, clinical features, and diagnosis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. (2023) 21:723–36. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2023.2220964

5.

Jeong W Keighley C Wolfe R Lee WL Slavin MA Kong DCM et al . The epidemiology and clinical manifestations of mucormycosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of case reports. Clin Microbiol Infect. (2019) 25:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.07.011

6.

Prakash H Chakrabarti A . Epidemiology of mucormycosis in India. Microorganisms. (2021) 9:523. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9030523

7.

Hallur V Prakash H Sable M Preetam C Purushotham P Senapati R et al . Cunninghamella arunalokei a new species of Cunninghamella from India causing disease in an immunocompetent individual. J Fungi. (2021) 7:670. doi: 10.3390/jof7080670

8.

Alqarihi A Kontoyiannis DP Ibrahim AS . Mucormycosis in 2023: an update on pathogenesis and management. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2023) 13:1254919. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2023.1254919

9.

Puerta-Alcalde P Monzo-Gallo P Aguilar-Guisado M Ramos JC Laporte-Amargos J Machado M et al . Breakthrough invasive fungal infection among patients with haematologic malignancies: a national, prospective, and multicentre study. J Infect. (2023) 87:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2023.05.005

10.

Pagano L Caira M Candoni A Offidani M Fianchi L Martino B et al . The epidemiology of fungal infections in patients with hematologic malignancies: the SEIFEM-2004 study. Haematologica. (2006) 91:1068–75. PMID:

11.

Prakash H Chakrabarti A . Global epidemiology of mucormycosis. J Fungi. (2019) 5:26. doi: 10.3390/jof5010026

12.

Suo T Xu M Xu Q . Clinical characteristics and mortality of mucormycosis in hematological malignancies: a retrospective study in Eastern China. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. (2024) 23:82. doi: 10.1186/s12941-024-00738-8

13.

Schwartze VU Jacobsen ID . Mucormycoses caused by Lichtheimia species. Mycoses. (2014) 57:73–8. doi: 10.1111/myc.12239

14.

Hu ZM Wang LL Zou L Chen ZJ Yi Y Meng QB et al . Coinfection pulmonary mucormycosis and aspergillosis with disseminated mucormycosis involving gastrointestinalin in an acute B-lymphoblastic leukemia patient. Braz J Microbiol. (2021) 52:2063–8. doi: 10.1007/s42770-021-00554-8

15.

Fujisaki T Inagaki J Kouroki M Honda Y Matsuishi T Kamizono J et al . Pulmonary actinomycosis and mucormycosis coinfection in a patient with Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia undergoing chemotherapy. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. (2022) 44:e529–31. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000002181

16.

Ding WJ Ma XY Li L . Rhinocerebral mucormycosis secondary to acute leukemia: a case report. Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. (2021) 56:1207–9. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn115330-20210122-00030

17.

Yamamoto K Mawatari M Fujiya Y Kutsuna S Takeshita N Hayakawa K et al . Survival case of rhinocerebral and pulmonary mucormycosis due to Cunninghamella bertholletiae during chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia: a case report. Infection. (2021) 49:165–70. doi: 10.1007/s15010-020-01491-8

18.

Popa G Blag C Sasca F . Rhinocerebral mucormycosis in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a case report. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. (2008) 30:163–5. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31815c255f

19.

Yang S Du W Zhang Y Fan Y Wang N . A case report of acute lymphoblastic leukemia complicated by naso-ophthalmic mucormycosis. Cureus. (2025) 17:e79984. doi: 10.7759/cureus.79984

20.

Yeung CK Cheng VC Lie AK Yuen KY . Invasive disease due to Mucorales: a case report and review of the literature. Hong Kong Med J. (2001) 7:180–8.

21.

Samanta DR Senapati SN Sharma PK Shruthi BS Paty PB Sarangi G . Hard palate perforation in acute lymphoblastic leukemia due to mucormycosis—a case report. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. (2009) 25:36–9. doi: 10.1007/s12288-009-0009-3

22.

Siriwardena P Wariyapperuma U Nanayakkara P Jayawardena N Mendis D Bahar M et al . Rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis in acute myeloid leukemia patients: a case series from Sri Lanka. BMC Infect Dis. (2024) 24:1465. doi: 10.1186/s12879-024-10334-y

23.

Hu L Liu G Chen X . Rhinocerebral mucormycosis and Trichosporon asahii fungemia in a pediatric patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a rare coinfection. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. (2024) 66:e41. doi: 10.1590/S1678-9946202466041

24.

Ojeda-Diezbarroso K Aguilar-Rascon J Jimenez-Juarez RN Moreno-Espinosa S Resendiz-Sanchez J Romero-Zamora JL . Successful posaconazole salvage therapy for rhinocerebral mucormycosis in a child with leukemia. Review of the literature. Rev Iberoam Micol. (2019) 36:160–4. doi: 10.1016/j.riam.2018.07.008

25.

Uraguchi K Kozakura K Oka S Higaki T Makihara S Imai T et al . A case of rhinocerebral mucormycosis with brain abscess drained by endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery. Med Mycol Case Rep. (2020) 30:22–5. doi: 10.1016/j.mmcr.2020.09.004

26.

Wehl G Hoegler W Kropshofer G Meister B Fink FM Heitger A . Rhinocerebral mucormycosis in a boy with recurrent acute lymphoblastic leukemia: long-term survival with systemic antifungal treatment. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. (2002) 24:492–4. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200208000-00017

27.

Mutchnick S Soares D Shkoukani M . To exenterate or not? An unusual case of pediatric rhinocerebral mucormycosis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. (2015) 79:267–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2014.11.028

28.

Dworsky ZD Bradley JS Brigger MT Pong AL Kuo DJ . Multimodal treatment of rhinocerebral mucormycosis in a pediatric patient with relapsed pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2018) 37:555–8. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001839

29.

Gumral R Yildizoglu U Saracli MA Kaptan K Tosun F Yildiran ST . A case of rhinoorbital mucormycosis in a leukemic patient with a literature review from Turkey. Mycopathologia. (2011) 172:397–405. doi: 10.1007/s11046-011-9449-z

30.

Raj P Vella EJ Bickerton RC . Successful treatment of rhinocerebral mucormycosis by a combination of aggressive surgical debridement and the use of systemic liposomal amphotericin B and local therapy with nebulized amphotericin—a case report. J Laryngol Otol. (1998) 112:367–70. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100140484

31.

Sigera LSM Ahmed SA Al-Hatmi AMS Welagedara P Jayasekera PI de Hoog S . Actinomortierella wolfii: identity and pathology. Med Mycol Case Rep. (2022) 38:48–52. doi: 10.1016/j.mmcr.2022.10.005

32.

Lerchenmuller C Goner M Buchner T Berdel WE . Rhinocerebral zygomycosis in a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Ann Oncol. (2001) 12:415–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1011119018112

33.

Cofré F Villarroel M Castellon L Santolaya ME . Successful treatment of a persistent rhino-cerebral mucormycosis in a pediatric patient with a debut of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Rev Chilena Infectol. (2015) 32:458–63. doi: 10.4067/S0716-10182015000500015

34.

Ammon A Rumpf KW Hommerich CP Behrens-Baumann W Ruchel R . Rhinocerebral mucormycosis during deferoxamine therapy. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. (1992) 117:1434–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1062461

35.

Jacobs P Wood L Du Toit A Esterhuizen K . Eradication of invasive mucormycosis—effectiveness of the echinocandin FK463. Hematology. (2003) 8:119–23. doi: 10.1080/1024533031000090810

36.

Parkyn T McNinch AW Riordan T Mott M . Zygomycosis in relapsed acute leukaemia. J Infect. (2000) 41:265–8. doi: 10.1053/jinf.2000.0397

37.

Andreani G Fadda G Gned D Dragani M Cavallo G Monticone V et al . Rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and isavuconazole therapeutic drug monitoring during intestinal graft versus host disease. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. (2019) 11:e2019061. doi: 10.4084/MJHID.2019.061

38.

Funada H Mochizuki Y Machi T Ohtake S Matsuda T . Successful medical treatment of rhinocerebral mucormycosis complicating acute leukemia. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. (1991) 65:604–7. doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.65.604

39.

Brusis T Rister M . Rhinocerebral mucormycosis as a complication of cytostatic therapy. HNO. (1986) 34:262–6. PMID:

40.

Arber DA Orazi A Hasserjian RP Borowitz MJ Calvo KR Kvasnicka HM et al . International consensus classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemias: integrating morphologic, clinical, and genomic data. Blood. (2022) 140:1200–28. doi: 10.1182/blood.2022015850

41.

Braun TP Eide CA Druker BJ . Response and resistance to BCR-ABL1-targeted therapies. Cancer Cell. (2020) 37:530–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.03.006

42.

Hopke A Viens AL Alexander NJ Mun SJ Mansour MK Irimia D . Spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitors disrupt human neutrophil swarming and antifungal functions. Microbiol Spectr. (2025) 13:e0254921. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.02549-21

43.

McCreedy DA Abram CL Hu Y Min SW Platt ME Kirchhoff MA et al . Spleen tyrosine kinase facilitates neutrophil activation and worsens long-term neurologic deficits after spinal cord injury. J Neuroinflammation. (2021) 18:302. doi: 10.1186/s12974-021-02353-2

44.

Lefeivre T Jones L Trinquand A Pinton A Macintyre E Laurenti E et al . Immature acute leukaemias: lessons from the haematopoietic roadmap. FEBS J. (2022) 289:4355–70. doi: 10.1111/febs.16030

45.

Dempke WCM Zielinski R Winkler C Silberman S Reuther S Priebe W . Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity—are we about to clear this hurdle?Eur J Cancer. (2023) 185:94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2023.02.019

46.

Thomsen M Vitetta L . Adjunctive treatments for the prevention of chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced mucositis. Integr Cancer Ther. (2018) 17:1027–47. doi: 10.1177/1534735418794885

47.

Sharifpour A Gholinejad-Ghadi N Ghasemian R Seifi Z Aghili SR Zaboli E et al . Voriconazole associated mucormycosis in a patient with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia and hematopoietic stem cell transplant failure: a case report. J Mycol Med. (2018) 28:527–30. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2018.05.008

48.

Lamaris GA Ben-Ami R Lewis RE Chamilos G Samonis G Kontoyiannis DP . Increased virulence of Zygomycetes organisms following exposure to voriconazole: a study involving fly and murine models of zygomycosis. J Infect Dis. (2009) 199:1399–406. doi: 10.1086/597615

49.

Adler-Moore J Lewis RE Bruggemann RJM Rijnders BJA Groll AH Walsh TJ . Preclinical safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and antifungal activity of liposomal amphotericin B. Clin Infect Dis. (2019) 68:S244–59. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz064

50.

Vadivel S Gowrishankar M Vetrivel K Sujatha B Navaneethan P . Rhino orbital cerebral mucormycosis in COVID-19 crisis. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. (2023) 75:1014–20. doi: 10.1007/s12070-023-03474-1

51.

Liang M Xu J Luo Y Qu J . Epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical characteristics, and treatment of mucormycosis: a review. Ann Med. (2024) 56:2396570. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2024.2396570

Summary

Keywords

mucormycosis, fungal infection, rhino-orbital-cerebral, mixed phenotype acute leukemia, Philadelphia chromosome

Citation

Zhou Y, He M, Zhang Q, Yao J, Wang Z, Chen B, Guo J, Gao F and Liu Z (2025) Disseminated rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis in Philadelphia chromosome-positive mixed phenotype acute leukemia: a case report and literature review. Front. Med. 12:1672939. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1672939

Received

25 July 2025

Accepted

22 September 2025

Published

03 October 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Daniele Roberto Giacobbe, University of Genoa, Italy

Reviewed by

Seyed Amirhossein Dormiani Tabatabaei, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran

Claudia Bartalucci, University of Genoa, Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Zhou, He, Zhang, Yao, Wang, Chen, Guo, Gao and Liu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zefa Liu, ynliuzefa@126.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.