- 1Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Lübeck, Lübeck, Germany

- 2Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, University Hospital Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany

Background: The aim of this survey is to determine students’ preferences of the University Lübeck in Germany regarding various supplementary digital learning opportunities in the field of Gynecology and Obstetrics in order to better address students’ needs and to improve and modernize teaching.

Methods: An online questionnaire was carried out from the Medical Education Team of the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics at the University Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Lübeck among students during the gynecology rotation at the end of summer semester 2023.

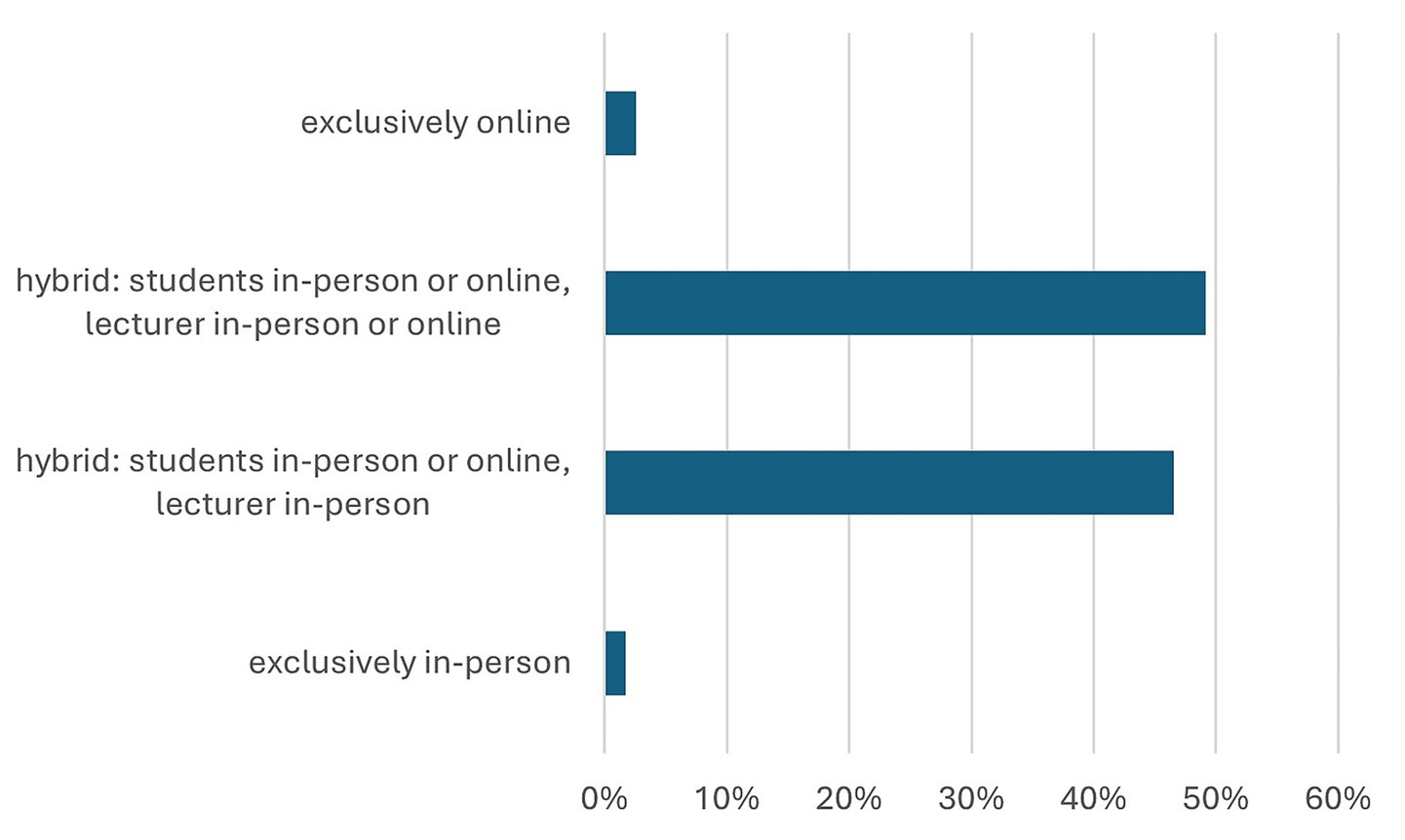

Results: A total of 117 students participated in this online questionnaire [32 male (28%) and 84 female (72%) students]. Hybrid lectures (participation either online or in the lecture hall) were preferred by 111 students (96%), whereas only 2 students (1.7%) favored exclusively in-person attendance. Online learning opportunities were rated as highly or very highly valuable by 93 students (80%). Online learning tools were mainly used for exam preparation [108 students (92%)], for targeted deepening of specific topics [82 students (70%)], to catch up on missed lectures [85 students (72%)] and to review or repeat a lecture content [83 students (71%)].

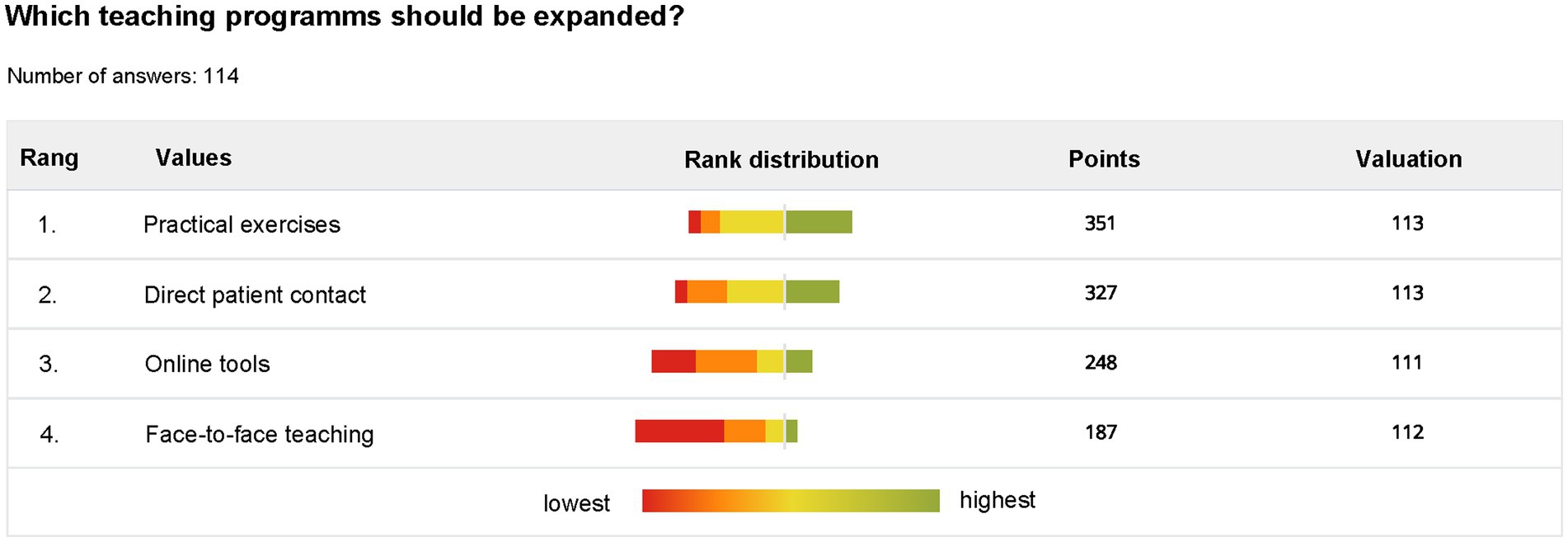

Conclusion: Traditional teaching methods such as practical exercises and “bed-side teaching”/patient contact are still highly valued by medical students, which students wish to see expanded. Additional online learning opportunities such as on-demand lectures are increasingly important in medical education and are very appreciated by students. Findings indicate that lecturers may consider these needs of the new medical student generation.

Introduction

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic led to a global crisis in the economy, society, and the healthcare system worldwide. While before the pandemic, the curriculum at medical faculties primarily consisted of in-person teaching, during the pandemic and especially under the suspension of in-person teaching temporarily mandated by national legislation, the question arose about the redesign and repositioning of medical university education (1).

As part of in-person teaching at the University Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Lübeck and generally in Germany as well as in many parts of Europe various subject-specific teaching formats are offered: lecturer-centred lectures in auditoriums, problem-oriented learning, small-group seminars, and clinical clerkships. Attendance at lectures is typically optional, while mandatory group seminars aim to convey course content through interactive discussions and hands-on practice. Further, bedside teaching and clinical clerkships provide students with practical insights. Students’ learning progress is assessed through written examinations and practical tests, including the Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE), a standardized assessment format widely used across Europe to evaluate clinical and communication skills (2).

Within the teaching context of the University Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Lübeck, a survey was conducted to evaluate student preferences regarding online and in-person lecture formats and various supplementary digital learning options in the field of Gynecology and Obstetrics. These should serve as supplements in preparing for examinations and clinical clerkships.

Although digital teaching formats were widely implemented during the pandemic, there is still limited evidence on how students in specific clinical disciplines—such as Gynecology and Obstetrics—perceive and evaluate these formats once regular in-person teaching has resumed. This study therefore aims to address this gap by analyzing students’ preferences regarding different teaching modalities within this subject area. The underlying hypothesis is that students’ preferences depend on the type and objectives of the learning activity, with digital formats being particularly valued for flexibility and exam preparation. The findings of this study are intended to contribute to a better understanding of how blended and digital learning components can be meaningfully integrated into the curriculum to support both educational quality and learner satisfaction.

Materials and methods

The following provides an overview of the questionnaire and the survey.

Participation was entirely anonymous. Multiple responses from the same participant were excluded through IP address verification. By participating in the online survey, participants provided informed consent for their involvement in the study as well as for the anonymous publication of the resulting data. The analysis included only questionnaires from participants who fully completed the survey.

Between May 12, 2023 and July 20, 2023, the Medical Education Team of the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics at the University Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Lübeck carried out an online survey among medical students in their fourth or fifth year of study (out of a total regular study period of approximately 6.5 years in Germany). In addition, midwifery and physiotherapy students were also invited to participate in the survey. Target groups were students participating in the learning course Gynecology and Obstetrics. The questionnaire was administered in German. A standardized digital questionnaire consisting of 19 questions (Supplementary Table 1) was constructed using an online survey platform.1 Participants were invited by email, via the official gynecology course homepage and by a reminder during the Gynecology and Obstetrics lecture. Individual questions could be skipped if participants were unable or unwilling to answer them.

The questionnaire was divided into two main sections: (1) student’s interests and teaching preferences and (2) demographic questions. The survey was conducted in accordance with the Office of Academic Affairs of the University of Lübeck. Respondents remained anonymous. Since no personally identifiable information was collected, there was no possibility of revoking the collected data at a later timepoint after completion. Responses to the questionnaire were changeable until final submission. Respondents were informed about the purpose of the survey and actively consented to participate.

Two questions regarded the grade on the Abitur (which is important for admission into medical school in Germany and comparable with A-Level grade or Scholastic Aptitude Test or the American College Test) and the grade achieved at the first part of state examination after 2 years of medical studies (so-called Physikum). The required average grade of the Abitur for admission to higher education institutions ranges from 1.0 to 4.0 with 1.0 being the best possible grade. To successfully pass the first part of state examinations, the students are required to achieve a grade between 1.0 and 4.0. Grades range from very good (1), good (2), satisfactory (3) to sufficient (4). These variables were collected to obtain a general overview of the participants’ educational background and overall academic performance.

The data analysis was conducted using the common statistical analysis programs Microsoft® Excel® for Microsoft 365 MSO (Version 2509 Build 16.0.19231.20138) and with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 29.0.2.0, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.), and the results were evaluated with descriptive statistics. To examine associations between categorical variables, such as the use of online learning resources and students’ age or gender, a chi-square test of independence was applied. This method is particularly suitable for comparing frequency distributions in contingency tables and allows assessment of whether observed group differences are random or statistically significant. The chi-square test was therefore considered the most appropriate approach, as the focus was on descriptive group comparisons rather than on modeling multivariate relationships, as would be the case with more complex methods such as logistic regression. p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All reported p values are two-sided. For the question: “How do you overall assess your personal learning gain from online learning options?,” a mean value analysis was also carried out using a t-test for 2 independent variables with two-sided significance. As the Levene test rejected the null hypothesis of equality of variance (significance 0.010), the calculation for sex was based on the assumption of inequality of variance. In the calculation for the age groups, the Levene test confirmed the null hypothesis, so that variance homogeneity was assumed here.

Results

Characteristics of the participants

A total of 358 students were invited to participate in the study, of whom 117 completed the survey (response rate 33%). Of the 131 students who started the survey, 117 completed it in full. The completion rate was therefore 89%. Within this group, for whom general descriptive information was available (n = 116), 110 students (95%) were studying human medicine, and 6 students (5%) were studying university-level midwifery out of a total of 69 midwifery students among the 358 students invited (8.6%).

In total, 84 students (72%) were female, and 32 students (28%) were male, no sex was stated by 1 student. On average, the respondents were 25 years old (n = 116) (range: 21–34), in the 9th university semester or 8th semester in their curriculum (n = 114), with a high school grade point average of 1.5 (range: 1.0–3.3) (n = 111), and an average score of 2.4 in the first part of their state examination (range: 1.0–4.0) (n = 101). A total of 42 respondents (36%) out of 114 reported having completed a previous vocational training: 14 students (12%) in nursing, 6 students (5%) bachelor/master in another university program, and 22 students (19%) in other medical training professions.

Evaluation and implementation of online learning opportunities

Medical specialties respondents (n = 117) were most interested in (multiple answers were possible) Obstetrics and Gynecology (43 students, 37%), internal medicine (40 students, 34%), paediatrics (39 students, 33%), general medicine (31 students, 27%), and anaesthesiology (30 students, 26%). The majority (89 students, 77%) of respondents wished for additional online learning tools. Participants’ preference on the mode of lecture is shown in Figure 1. Hybrid lectures, allowing participation either in person or online, were preferred by most respondents (111 students, 96%). While 57 students (49%) expressed no preference regarding the lecturer’s mode of participation (in person or remotely connected), 54 students (47%) preferred the lecturer to be physically present in the lecture hall. Only two students (2%) preferred exclusively face to face lectures and three students (3%) exclusively online lectures.

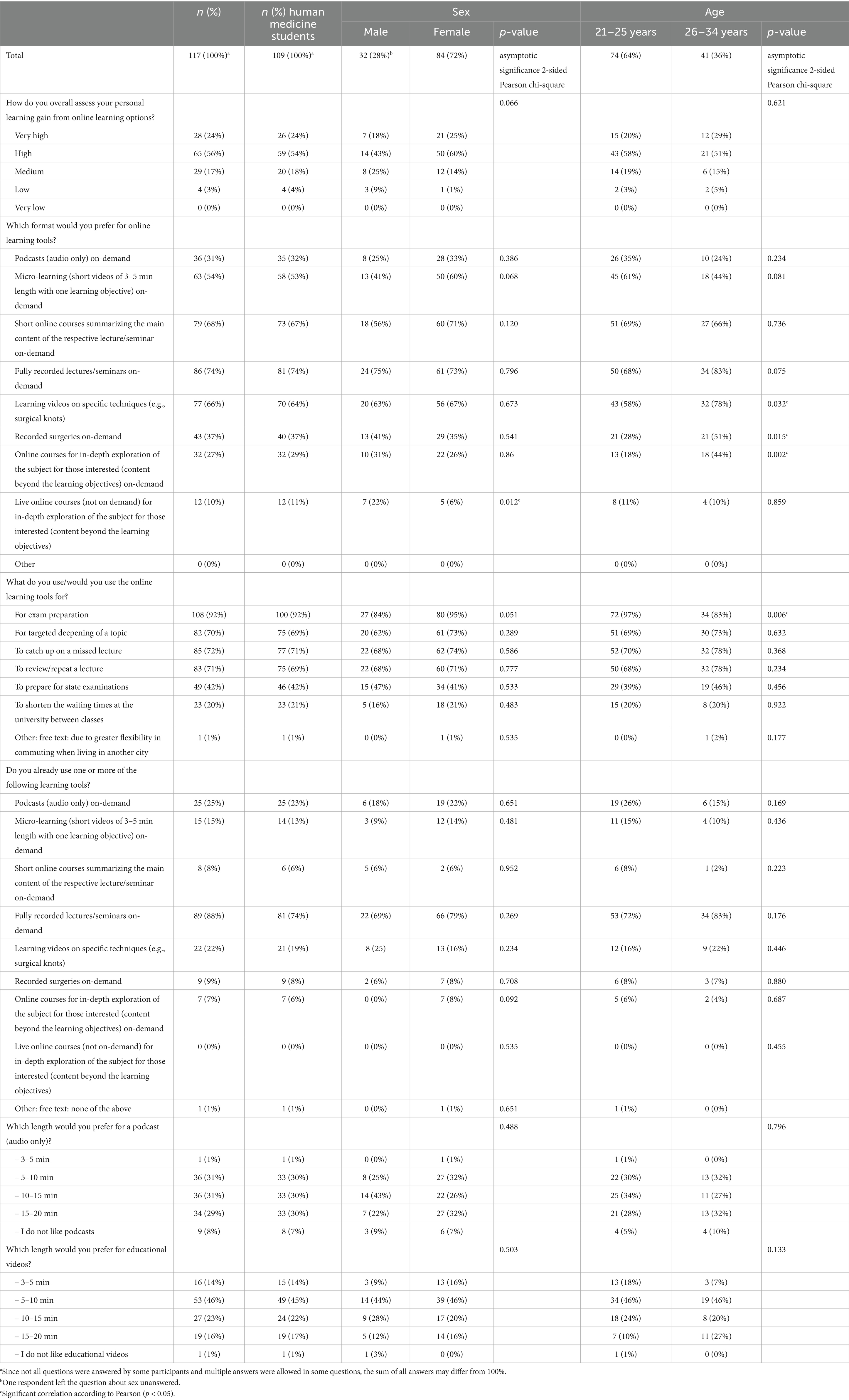

The learning gain from online learning tools was generally rated as high (65 students, 56%) or very high (28 students, 4%) (Table 1), with on-demand lectures and seminars being the most preferable options (86 students, 74%), followed by short online courses summarizing the content of lectures and/or seminars. Online tutorials for specific techniques (77 students, 66%), and micro-learning (63 students, 54%) were also considered helpful.

Table 1. Current preferences and previous experiences of students regarding online learning and the length of supplementary podcasts and educational videos.

Respondents used online learning tools primarily to prepare for examinations (108 students, 92%), catching up on missed lectures (85 students, 73%), as well as reviewing and deepening on specific topics (83 students, 71%). So far, recorded lectures and on-demand seminars were most frequently used (89 students, 88%), followed by on-demand audio podcasts (25 students, 25%) and instructional videos for specific techniques (22 students, 22%) (Table 1).

The respondents were also asked to rank four teaching methods depending on their preference for further future extension of these teaching formats. Depending on the order chosen by the student, the methods were awarded one to four points. Practical exercises achieved the highest total number (351 points), followed by direct patient contact (327 points) and online tools (248 points). Most students saw the lowest priority in expanding face-to-face teaching (Figure 2).

A further statistical comparison was conducted by dividing the students into two age groups based on the median age of 25 years (Table 1). The first age group (21–25 years) was designated as the younger age group, while the second age group (26–34 years) was designated as the older age group. Interestingly, nearly all students (72, 97%) in the younger age group already use or would use online learning options to prepare for examinations, compared to 34 students (83%) in the older age group (p = 0.006), showing a significant difference. In contrast, no significant differences were found with regard to sex or prior vocational training.

The personal learning gain by online learning options was given a mean value of 2.00 (standard deviation SD 0.74) and 1.92 (SD 0.66) for women and 2.2 (SD 0.91) for men in comparison (1 = very high; 2 = high; 3 = medium; 4 = low; 5 = very low). Overall, this indicates only a trend toward a potentially higher benefit for women, but no significant difference between the sexes (p = 0.092). There was also no significant difference in the mean values in both age groups (21–25; mean value 2.04 SD 0.71; 26–34 years, mean value 1.95 SD 0.80) although the older age group tended to give slightly higher ratings (p = 0.539).

In terms of format preferences, distinct age-specific patterns were observed that may be relevant for designing needs-oriented online curricula. Preferences for learning videos on specific techniques (p = 0.032), recorded surgeries (p = 0.015), and live online courses for in-depth exploration (p = 0.002) were particularly age-dependent: students in the older age group (26–34 years) chose these formats noticeably more often than younger students. Sex-related differences were observed only for the format ‘short online courses,’ which was preferred more frequently by women (p = 0.012).

Discussion

The results of this survey provide new insights into the preferences of students and the opportunities of digital learning tools.

According to the participants of this survey, the implementation of additional online content in medical education is of a high importance. The advantages reported by students are, among others, the increased learning flexibility and focused preparation for examinations. Various studies showed that e-learning technologies are easy to implement and lead to increased satisfaction and motivation for both teachers and students (3–6). As the spectrum of digital learning tools widened, the role of teachers has changed from content deliverers to learning companions and assessors of specific competencies (4). Students benefit from on-demand tools through increased flexibility and individual deepening of learning content based on their priorities and interests. In this context, it is crucial to emphasize that students in our survey, as well as other surveys previously conducted (7–9), generally reject exclusively digital teaching. However, the majority of the students in our survey indicated their wish for hybrid lectures, suggesting a strong preference for deciding their own mode of participation and pace of learning. Interestingly, nearly half of the respondents expect the lecturer to be present in the lecture hall (as opposed to remotely connected). This indicates that the option of face-to-face teaching and direct communication remains an important part of student-teacher interaction.

Hands on teaching especially during clerkships and sub internships in an in- and out-patient setting is more extensive in the German medical curriculum compared to other countries. Particularly the entire final year of their studies consists of mandatory trimester sub internships in Internal Medicine, General Surgery and a subject of choice (10). Before that, they only gain insights into the clinical routine of various disciplines for short periods (freely selectable short internships and defined clinical clerkships), thus acquiring specific practical experiences. Therefore, German medical education offers limited self-determined orientation, making positive experiences in clinical clerkships a major factor that influences the choice of the third elective subject in the final year of medical school. International studies confirm the importance of positive experiences in medical internships and their influence on students’ interest in a particular medical field and the choice of discipline (11–13).

A complete overhaul of the medical curriculum with exclusively digital events and learning tools is not only undesirable for students but also seems counterproductive in terms of acquiring practical skills and positive clinical experiences. Therefore, blended learning concepts, which synergistically combine analogue (clinical clerkships, practical seminars) and digital (lecture recordings, podcasts, micro-learning) learning offerings, have gained particular importance over the last years (7). They allow courses for participants from different training and study programs in the spirit of interprofessional education. Furthermore, they provide options for flexible participation, benefiting students in various life stages (parents, commuters, working professionals etc.) (5, 14–17).

When expanding digital teaching offerings in medical education, several key considerations must be addressed to ensure educational quality and learner outcomes.

Learner engagement is often reduced in online and hybrid formats, with increased distraction and off-task activities documented among online participants, which correlates with lower learning performance compared to on-site learners (18). Strategies to enhance engagement—such as interactive synchronous sessions, regular formative assessments, and structured opportunities for peer and instructor interaction—are essential (19, 20).

Preference for digital formats does not consistently translate into superior assessment scores. While some students report greater satisfaction and flexibility with digital or blended learning, studies show that exam performance may be lower in hybrid or fully digital settings, especially when interactivity and direct communication are limited (18, 21, 22).

In the context of the German medical education system, these findings align with international trends emphasizing the integration of digital tools into traditionally practice-oriented curricula. While universities worldwide have increasingly adopted blended learning models to enhance flexibility and lifelong learning skills (23, 24), the challenge remains to ensure that digital education complements rather than replaces essential clinical experiences (25, 26). At the University Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Lübeck, the results of this survey highlight the need to adapt curricular structures in a way that leverages digital tools for preparatory and supplementary learning while preserving direct patient contact and interactive small-group formats as core elements of clinical training. Future curricular reforms should therefore focus on developing a sustainable hybrid teaching framework that supports competence-based learning, fosters self-directed study, and maintains high standards of practical and professional skill acquisition (27, 28). Furthermore, the curricular integration of blended learning formats should be supported by appropriate infrastructural and didactic frameworks, such as faculty development programs, technical platforms, and quality assurance measures.

Conclusion

In summary, this survey demonstrates the strong preferences of students for the expansion of digital teaching formats. However, it should be noted that a successful expansion of digital teaching in medical education requires robust technical support, active measures to foster engagement, and a blended approach that preserves essential in-person elements to optimize both satisfaction and learning outcomes. Blended learning concepts seem to be a suitable option for combining digital and analog approaches, thereby positively influencing teaching and making it future-oriented.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The study involving humans was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Lübeck. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because prior to the start of the survey, participants were required to confirm that their participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time. They were only able to proceed with the survey after providing consent by selecting ‘I agree’ to these statements.

Author contributions

CC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NT: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NK: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AR: Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MB-P: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The results of the survey were presented for the first time at the European Board & College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (EBCOG) Congress as a selected oral presentation by the scientific committee on June 6, 2025, in Frankfurt, Germany.

Conflict of interest

NT received honoraria for lectures and advisory boards: Novartis, Exact Sciences, Pfizer, Georg Thieme Verlag, if-kongress, Deltamed; Study support: Novartis; Travel expenses: Novartis, Daiichi sankyo, Astra Zeneca, Aurikamed. AR received honoraria for lectures: Roche, Pfizer, Novartis, Celgen, LEO Pharma, Novartis, ExactSciences, Pierre Fabre, Lilly, Seagen, Targos, RG; Advisory Boards: Roche, Astra Zeneca, Pfizer, Celgen, Eisai, Novartis, MSD, Hexal, Amgen, ExactSciences, Pierre Fabre. MB-P received honoraria for lectures and advisory boards: Roche, Novartis, Pfizer, pfm, Eli Lilly, Onkowissen, Seagen, AstraZeneca, Eisai, Amgen, Samsung, Canon, MSD, GSK, Daiichi Sankyo, Gilead, Sirius Medical, Syantra, resitu, Pierre Fabre, ExactSciences, Aurikamed; Study support: Korean Breast Cancer Society, Eugen & Irmgard Hahn Stiftung, EndoMag, Mammotome, MeritMedical, Sirius Medical, Gilead, Hologic, ExactSciences, Claudia von Schilling Stiftung, Damp Stiftung, Ehmann Stiftung Savognin; Travel expenses: Eli Lilly, ExactSciences, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer, Daiichi Sankyo, Roche, Stemline.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2025.1705733/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

1. Olmes, GL, Zimmermann, JSM, Stotz, L, Takacs, FZ, Hamza, A, Radosa, MP, et al. Students’ attitudes toward digital learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey conducted following an online course in gynecology and obstetrics. Arch Gynecol Obstet. (2021) 304:957–63. doi: 10.1007/s00404-021-06131-6

2. Nikendei, C, Weyrich, P, Jünger, J, and Schrauth, M. Medical education in Germany. Med Teach. (2009) 31:591–600. doi: 10.1080/01421590902833010

3. Kay, D, and Pasarica, M. Using technology to increase student (and faculty satisfaction with) engagement in medical education. Adv Physiol Educ. (2019) 43:408–13. doi: 10.1152/advan.00033.2019

4. Ruiz, JG, Mintzer, MJ, and Leipzig, RM. The impact of e-learning in medical education. Acad Med. (2006) 81:207–12. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200603000-00002

5. Riedel, M, Amann, N, Recker, F, Hennigs, A, Heublein, S, Meyer, B, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on medical teaching in obstetrics and gynecology-a nationwide expert survey among teaching coordinators at German university hospitals. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0269562. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0269562

6. Naciri, A, Radid, M, Kharbach, A, and Chemsi, G. E-learning in health professions education during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. J Educ Eval Health Prof. (2021) 18:27. doi: 10.3352/jeehp.2021.18.27

7. Mudenda, S, Daka, V, Mufwambi, W, Matafwali, SK, Chabalenge, B, Skosana, P, et al. Student's perspectives, satisfaction and experiences with online and classroom learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: findings and implications on blended learning. SAGE Open Med. (2023) 11:20503121231218904. doi: 10.1177/20503121231218904

8. Chilton, JK, Hanks, S, and Watson, HR. A blended future? A cross-sectional study demonstrating the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on student experiences of well-being, teaching and learning. Eur J Dent Educ. (2024) 28:170–83. doi: 10.1111/eje.12934

9. Çakmakkaya, ÖS, Meydanlı, EG, Kafadar, AM, Demirci, MS, Süzer, Ö, Ar, MC, et al. Factors affecting medical students' satisfaction with online learning: a regression analysis of a survey. BMC Med Educ. (2024) 24:11. doi: 10.1186/s12909-023-04995-7

10. Recker, F, Schulmeyer, C, Becker, L, and Weiss, M. PJ-Wahlfach in der Corona-Krise. Frauenarzt. (2020) 4:311.

11. Riedel, F, Fremd, C, Tabatabai, P, Smetanay, K, Doster, A, Heil, J, et al. Exam preparation course in obstetrics and gynecology for the German medical state examination: proof of concept and implications for the recruitment of future residents. Arch Gynecol Obstet. (2016) 294:1235–41. doi: 10.1007/s00404-016-4168-9

12. Dornan, T, Littlewood, S, Margolis, SA, Scherpbier, A, Spencer, J, and Ypinazar, V. How can experience in clinical and community settings contribute to early medical education? A BEME systematic review. Med Teach. (2006) 28:3–18. doi: 10.1080/01421590500410971

13. Riedel, M, Eisenkolb, G, Amann, N, Karge, A, Meyer, B, Tensil, M, et al. Experiences with alternative online lectures in medical education in obstetrics and gynecology during the COVID-19 pandemic-possible efficient and student-orientated models for the future? Arch Gynecol Obstet. (2022) 305:1041–53. doi: 10.1007/s00404-021-06356-5

14. Fischer, MR. Digital teaching after the pandemic—enriching diversity of teaching methods and freedom for inclination-oriented learning? GMS J Med Educ. (2021) 38:Doc111. doi: 10.3205/zma001507

15. Restini, C, Faner, M, Miglio, M, Bazzi, L, and Singhal, N. Impact of COVID-19 on medical education: a narrative review of reports from selected countries. J Med Educat Curri Develop. (2023) 10:23821205231218122. doi: 10.1177/23821205231218122

16. Mlinar Reljić, N, Drešček Dolinar, M, Štiglic, G, Kmetec, S, Fekonja, Z, and Donik, B. E-learning in nursing and midwifery during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare (Basel). (2023) 11:3094. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11233094

17. Nees, J, Struewe, F, and Schott, S. Medical students' knowledge on cancer predisposition syndromes and attitude toward eHealth. Arch Gynecol Obstet. (2024) 309:1535–41. doi: 10.1007/s00404-023-07266-4

18. Ochs, C, Gahrmann, C, and Sonderegger, A. Learning in hybrid classes: the role of off-task activities. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:1629. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-50962-z

19. Lee, J, Choi, H, Davis, RO, and Henning, MA. Instructional media selection principles for online medical education and emerging models for the new normal. Med Teach. (2023) 45:633–41. doi: 10.1080/0142159x.2022.2151884

20. Li, X, Lin, X, Zhang, F, and Tian, Y. What matters in online education: exploring the impacts of instructional interactions on learning outcomes. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:792464. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.792464

21. Holzmann-Littig, C, Zerban, NL, Storm, C, Ulhaas, L, Pfeiffer, M, Kotz, A, et al. One academic year under COVID-19 conditions: two multicenter cross-sectional evaluation studies among medical students in Bavarian medical schools, Germany students' needs, difficulties, and concerns about digital teaching and learning. BMC Med Educ. (2022) 22:450. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03480-x

22. McGee, RG, Wark, S, Mwangi, F, Drovandi, A, Alele, F, and Malau-Aduli, BS. Digital learning of clinical skills and its impact on medical students' academic performance: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. (2024) 24:1477. doi: 10.1186/s12909-024-06471-2

23. Sandars, J, Correia, R, Dankbaar, M, de Jong, P, Goh, PS, Hege, I, et al. Twelve tips for rapidly migrating to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. MedEdPublish (2016). (2020) 9:82. doi: 10.15694/mep.2020.000082.1

24. O'Doherty, D, Dromey, M, Lougheed, J, Hannigan, A, Last, J, and McGrath, D. Barriers and solutions to online learning in medical education—an integrative review. BMC Med Educ. (2018) 18:130. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1240-0

25. Rose, S. Medical student education in the time of COVID-19. JAMA. (2020) 323:2131–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5227

26. Dost, S, Hossain, A, Shehab, M, Abdelwahed, A, and Al-Nusair, L. Perceptions of medical students towards online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national cross-sectional survey of 2721 UK medical students. BMJ Open. (2020) 10:e042378. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042378

27. Fu, XT, Hu, Y, Yan, BC, Jiao, YG, Zheng, SJ, Wang, YG, et al. The use of blended teaching in higher medical education during the pandemic era. Int J Clin Pract. (2022) 2022:3882975. doi: 10.1155/2022/3882975

Keywords: medical education, COVID pandemics, digital teaching, micro-learning, podcast, questionnaire

Citation: Cirkel C, Tauber N, Krawczyk N, Scharf JL, Rody A and Banys-Paluchowski M (2025) Medical education in Obstetrics and Gynecology: preferences of medical students regarding digital teaching. Front. Med. 12:1705733. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1705733

Edited by:

Florian Recker, University of Bonn, GermanyReviewed by:

Vedran Katavic, University of Zagreb, CroatiaFabian Riedel, Heidelberg University Hospital, Germany

Copyright © 2025 Cirkel, Tauber, Krawczyk, Scharf, Rody and Banys-Paluchowski. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nikolas Tauber, bmlrb2xhcy50YXViZXJAdWtzaC5kZQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Christoph Cirkel1†

Christoph Cirkel1† Nikolas Tauber

Nikolas Tauber