Abstract

Background:

Prior studies have indicated that inhalation anesthesia in cancer surgery might heighten the risk of tumor metastasis and diminish patient survival. Yet, combined inhalation and intravenous anesthesia (CIVA), a prevalent general anesthesia technique, remains underexplored regarding its influence on postoperative survival in cancer surgery patients. To fill this gap, this study compares the short-term and long-term mortality of cancer surgery patients receiving CIVA versus total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA).

Methods:

A retrospective cohort study was conducted at a tertiary care hospital in China, comprising 25,351 patients who underwent cancer surgery under general anesthesia between January 2014 and December 2018. The primary outcomes were short-term mortality (within 3 months) and long-term mortality (within 3 years). CIVA and TIVA were the primary exposures. Propensity score matching (PSM) was employed to adjust for confounding factors, and Cox regression models were utilized to estimate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for mortality outcomes.

Results:

Among the 25,351 patients who underwent tumor resection, 23,790 were administered TIVA, while 1,561 received CIVA. In the 1:3 PSM cohort, 1,536 patients received CIVA, and 4,519 patients received TIVA. The Cox regression models for the 1:1, 1:2, and 1:3 PSM cohorts indicated that CIVA was associated with long-term mortality but not with short-term mortality. The multivariable Cox regression model following 1:3 PSM revealed that CIVA was associated with an increased risk of 3-year mortality (HR: 1.220; 95% CI: 1.043–1.404).

Conclusion:

Our results provided indirect evidence of potential hazard of inhaled anesthetics, even as a compound in CIVA, on long-term mortality after cancer surgery. Given the limitations of this retrospective study, further prospective work exploring the effect of anesthetic technique on mortality is urgently needed.

Introduction

Amid the backdrop of a growing elderly demographic, the prevalence of cancer is projected to escalate from 14 million cases in 2012 to approximately 24 million cases by 2035 (1). For patients with solid organ cancers, surgery serves as a pivotal treatment modality, with estimates suggesting that surgical procedures will be integral to the treatment plans of more than 80% of cancer patients (2). Paradoxically, surgery itself, surgical stress response, and anesthesia treatments can facilitate tumor proliferation or metastasis by multiple pathways, such as metabolic and neuroendocrine perturbations (3–7). This has led to increasing interest in the impact of anesthesia and operation on cancer progression and mortality (8).

Over the past decade, the impact of anesthesia on cancer recurrence has garnered growing interest, prompting a surge in retrospective studies and pre-clinical investigations. Various underlying biological mechanisms have been proposed to explain how different anesthetic agents might affect cancer outcomes involved in tumorigenesis and metastasis (9, 10). In clinical practice, there are two key classes of general anesthetic agents: intravenous propofol and inhalational volatile anesthetics. Inhalational volatile anesthetic agents like sevoflurane, potentially augment proliferation, migration, invasion, and angiogenesis in various cancer cell types (9), while propofol has been shown to counteract these pathways (10, 11). Given these properties, it is theoretically possible that inhalational volatile anesthetics could potentially promote tumor metastasis and recurrence.

Unfortunately, the available evidence regarding the effects of specific anesthetic agents on cancer outcomes, are inconclusive (7, 8, 12–15). Some researchers showed that volatile anesthesia could damage the cancer-specific immune defenses in vitro study (9), and increase the mortality after cancer surgery in retrospective clinical study (7), compared with intravenous anesthetic agents. Yet, others did not observe a significant association between the type of general anesthesia and overall mortality after cancer surgery (12, 13). The inconsistent findings regarding the impact of inhalation and intravenous anesthesia on postoperative cancer survival can be largely attributed to the fact that the majority of studies conducted thus far are retrospective cohort studies, which are prone to issues such as incomplete data, selection bias, and confounding factors. Moreover, the inherent biological characteristics and prognostic factors vary significantly among different types of cancer, such as breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and lung cancer, adding another layer of complexity to the research outcomes. Furthermore, we speculate that regional differences in the types, dosages, and durations of anesthetic agents used in clinical practice may also exert a certain influence on postoperative prognosis.

General anesthesia is presently offered in a variety of forms, including total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA), fluorinated inhalation anesthesia (IA) and combined inhalation and intravenous anesthesia (CIVA). Previous clinical studies have focused on the effects of TIVA and inhalation anesthesia on mortality. Among the published evidence, there are currently no data concerned the effect of CIVA or TIVA on mortality of cancer patient. To further assess the relationship between type of anesthesia and mortality after oncologic surgery, we conducted this retrospective cohort study to compare the short/long-term mortality after cancer surgery in patients receiving CIVA or TIVA.

Methods

Study participants

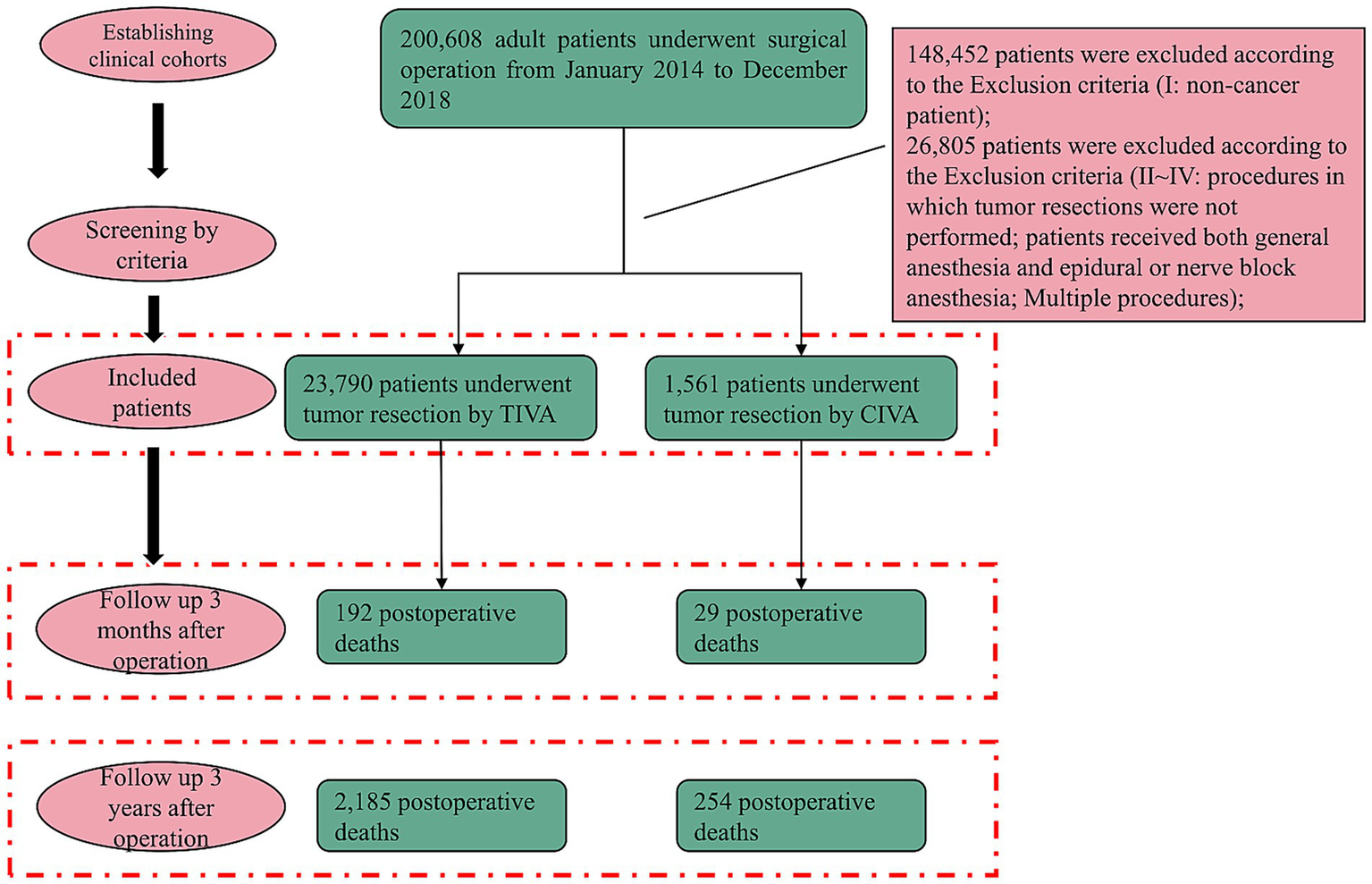

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at Wuhan Union hospital, Hubei, China, a tertiary comprehensive hospital, following the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline. This study was authorized by the ethical committee at Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (20210641) on 19th July, 2023. The committee did not require written informed consent since only aggregated data that was not personally identifiable to the patient was used. All patients presenting for cancer surgery over a five-year period (January 2014 to December 2018) who required general anesthesia were included (Figure 1). Cancer diagnoses were confirmed based on postoperative pathological reports, ensuring accurate identification of tumor characteristics. The exclusion criteria are as follows: (I) Non-cancer patient; (II) Procedures in which tumor resections were not performed; (III) Patients received both general anesthesia and epidural or nerve block anesthesia; (IV) multiple procedures.

Figure 1

Flowchart of patient selection. Exclusions: (I) non-cancer patient; (II) endoscopic polyp resections, intestinal stent insertions, and procedures in which tumor resections were not performed; (III) combined anesthesia; (IV) multiple procedures with different anesthesia forms.

Exposure

The two forms of general anesthesia of interest in this study were TIVA and CIVA. TIVA was identified as relying on sustained infusion of propofol and remifentanil to maintain general anesthesia. In contrast, CIVA technique was defined as the concurrent administration of any inhaled volatile anesthetic (sevoflurane or desflurane) with intravenous propofol and remifentanil for >15 min during the maintenance period. The exact concentrations and the proportional maintenance time contributed by inhalation vs. intravenous agents were not captured in our dataset.

Outcomes

We extracted information from electronic clinical medical records of Wuhan Union Hospital. The primary outcome was cancer-cause mortality derived from the China’s National Disease Surveillance Points (DSP) system spanning the years 2014 to 2021. It was defined as death with cancer as the root cause, recorded in the Life Registration and Cause of Death Monitoring Room, China CDC, which excluded death directly caused by cardiogenic disease and trauma. According to the survival time of patients, the death outcome was further divided into short-term death (3 months after operation) and long-term death (3 years after operation).

This DSP system is established and managed by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC). After a significant upgrade in 2013, the DSP system expanded its surveillance points to 605, covering urban (208 points) and rural (397 points) areas across all 31 provinces/autonomous regions/municipalities (hereafter termed provinces) of the Chinese mainland (16). Mortality data are collected from a wide range of sources, encompassing hospitals, private residences, and various other locations. Trained professionals based at local hospitals or branches of the CDC utilize a standardized protocol to ascertain the causes of death. The DSP system has been validated in prior research as a robust tool for capturing both national and regional data, reliably documenting cancer-related fatalities (17, 18). To maintain the integrity and consistency of the data, annual training sessions are implemented, focusing on the standardized protocol. These sessions incorporate random audits to verify the precision of disease classification and to identify any duplications. Additionally, retrospective reviews are periodically conducted to assess the extent of underreporting and to ensure the accuracy and completeness of disease coding. Every 3 years, underreporting surveys are executed to evaluate the DSP system’s comprehensiveness and to rectify any potential biases stemming from underreporting (19).

Matching covariates

The confounding variables for propensity score matching (PSM) included in this study were sex, age, body mass index (BMI), American society of Anesthesiologists physical status (ASAPS), duration of surgery, type of tumor (including ear, nose & throat [ENT] tumor, Gastrointestinal tract tumor, Orthopedic tumor, Urological tumor, General surgery tumor, Nervous system tumor, Thoracic tumor, and Ophthalmic tumor), previous surgical history, previous heart disease history, previous diabetes history, previous hypertension history, previous cerebral infarction history, history of drinking, history of smoking, surgery grade, emergency surgery, shift change of anesthesiologist, transfusion, intraoperative blood loss, intraoperative blood transfusion volume and intraoperative vasoactive drugs. Detailed definitions of matching variables are provided in Supplementary Method 1.

Statistical analysis

Clinical data are presented as numbers (percentage) for categorical variables and as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (minimum, maximum) for continuous variables, as appropriate. Preliminary assessments of differences in clinical data were conducted using Student’s t-test or Welch’s t-test for continuous variables, and Pearson’s chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, between the TIVA and CIVA groups before and after PSM.

The PSM was applied to balance confounding variables between the TIVA and CIVA groups in this study. A multivariable logistic regression model was used to estimate the propensity scores. The 1:1, 1:2, and 1:3 matching protocols without replacement, along with a caliper of 0.05 SD of the logit of the propensity score, were employed. Standardized mean differences (SMDs) were computed for the three PSM cohorts to assess baseline balance following PSM. Cox regression models were applied to the three PSM cohorts to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and their associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for long- and short-term postoperative mortality. Univariate and multivariable Cox regression models were used to investigate the TIVA/CIVA associated with postoperative mortality. Confounding variables with p < 0.05, identified between the TIVA and CIVA groups after 1:3 PSM, were included in the multivariable Cox regression analyses to calculate the adjusted HR.

All statistical analyses were conducted using the R environment, version 4.2.0. The statistical packages “MatchIt” and “survival” were used for propensity score matching and Cox regression, respectively (Supplementary Method 2).

Results

Study population and baseline characteristics

A total of 200,608 patients who received surgical operation under general anesthesia in Wuhan Union Hospital between January 2014 and December 2018 were identified. 148,452 non-cancer patients were excluded. In the remaining population, 26,805 patients were removed based on exclusion criteria II–IV. Ultimately, 23,790 (93.8%) patients were included in the TIVA group while 1,561 (6.2%) patients were included in the CIVA group (Table 1). Data before PSM demonstrated that when compared to patients received TIVA, patients who received CIVA had a higher incidence of 3-year mortality (254 [16.3%] vs. 2,185 [9.2%]) and 3-month mortality after operation (29 [1.9%] vs. 192 [0.8%]).

Table 1

| Before propensity score matching | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIVA (N = 23,790) | CIVA (N = 1,561) | p-value | SMD | SMD-0.1 | |

| Outcomes | |||||

| Death 3 years after operation | 2,185 (9.2%) | 254 (16.3%) | <0.001 | – | – |

| Death 3 months after operation | 192 (0.8%) | 29 (1.9%) | <0.001 | – | – |

| Matching variables | |||||

| Age | 49.0 (15.2) | 51.0 (20.5) | <0.001 | 0.10 | <0.1 |

| Male | 10,059 (42.3%) | 824 (52.8%) | <0.001 | 0.21 | >0.1 |

| BMI | 23.8 (4.41) | 23.6 (5.22) | 0.208 | 0.03 | <0.1 |

| ASAPS | |||||

| I | 1,586 (6.7%) | 129 (8.3%) | <0.001 | 0.06 | <0.1 |

| II | 11,018 (46.3%) | 1,022 (65.5%) | 0.40 | >0.1 | |

| III | 3,570 (15.0%) | 375 (24.0%) | 0.21 | >0.1 | |

| IV and higher | 7,616 (32.0%) | 35 (2.2%) | 2.23 | >0.1 | |

| Duration of surgery | 2.40 [0, 23.5] | 3.25 [0, 13.1] | <0.001 | 0.39 | >0.1 |

| Tumor type | |||||

| ENT tumor | 1776 (7.5%) | 19 (1.2%) | <0.001 | 0.57 | >0.1 |

| Gynecological tumor | 1,216 (5.1%) | 91 (5.8%) | 0.03 | <0.1 | |

| Gastrointestinal tract tumor | 5,694 (23.9%) | 627 (40.2%) | 0.33 | >0.1 | |

| Orthopedic tumor | 1,646 (6.9%) | 87 (5.6%) | 0.06 | <0.1 | |

| Urological tumor | 1,616 (6.8%) | 147 (9.4%) | 0.09 | <0.1 | |

| General surgery tumor | 8,666 (36.4%) | 354 (22.7%) | 0.33 | >0.1 | |

| Nervous system tumor | 2,171 (9.1%) | 141 (9.0%) | 0.00 | <0.1 | |

| Thoracic tumor | 896 (3.8%) | 78 (5.0%) | 0.06 | <0.1 | |

| Ophthalmic tumor | 109 (0.5%) | 17 (1.1%) | 0.06 | <0.1 | |

| Previous surgical history | 8,756 (36.8%) | 509 (32.6%) | 0.09 | <0.1 | |

| Previous heart disease | 318 (1.3%) | 66 (4.2%) | <0.001 | 0.14 | >0.1 |

| Previous diabetes | 1,041 (4.4%) | 114 (7.3%) | <0.001 | 0.11 | >0.1 |

| Previous hypertension | 3,530 (14.8%) | 353 (22.6%) | <0.001 | 0.19 | >0.1 |

| Previous cerebral infarction | 198 (0.8%) | 28 (1.8%) | <0.001 | 0.07 | <0.1 |

| History of drinking | 2,624 (11.0%) | 201 (12.9%) | <0.001 | 0.06 | <0.1 |

| History of smoking | 3,584 (15.1%) | 318 (20.4%) | 0.027 | 0.13 | >0.1 |

| Surgery grade | <0.001 | ||||

| Intermediate | 10,172 (42.8%) | 952 (61.0%) | 0.37 | >0.1 | |

| Major | 3,067 (12.9%) | 219 (14.0%) | <0.001 | 0.03 | <0.1 |

| Minor | 10,551 (44.4%) | 390 (25.0%) | 0.45 | >0.1 | |

| Emergency surgery | 2,864 (12.0%) | 188 (12.0%) | 0.00 | <0.1 | |

| Shift change of anesthesiologist | 3,627 (15.2%) | 341 (21.8%) | 1 | 0.10 | >0.1 |

| Night shift (18:00 ~ 8:00) | 922 (3.9%) | 100 (6.4%) | <0.001 | 0.16 | >0.1 |

| Transfusion | 1,229 (5.2%) | 281 (18.0%) | <0.001 | 0.33 | >0.1 |

| Intraoperative blood loss | 68.4 (267) | 150 (439) | <0.001 | 0.19 | >0.1 |

| Intraoperative blood transfusion amount | 30.6 (145) | 75.3 (293) | <0.001 | 0.15 | >0.1 |

| Intraoperative vasoactive drugs | 2,784 (11.7%) | 395 (25.3%) | <0.001 | 0.31 | >0.1 |

Data of cancer patients undergoing tumor resection before propensity score matching.

TIVA = total intravenous anesthesia; CIVA = combined inhalation and intravenous anesthesia; SMD=Standard mean deviation; BMI=Body Mass index; ASAPS = American society of Anesthesiologists physical status; ENT surgery = ear, nose, and throat surgery. Data are presented as the number (percentage) for categorical variables and as the mean ± SD or median (minimum, maximum) for continuous variables, as appropriate. The independent samples t-test was used to compare continuous variables and the chi-square test to compare categorical variables between groups.

Regarding baseline characteristics, patients in the CIVA group were older (mean [SD] age, 51.0 [20.5] years vs. 49.0 [15.2] years), more likely to be male (52.8% vs. 42.3%) and had a higher proportion of preoperative comorbidities (heart disease: 4.2% vs. 1.3%; diabetes: 7.3% vs. 4.4%; hypertension: 22.6% vs. 14.8%; cerebral infarction: 1.8% vs. 0.8%). In terms of anesthesia, patients with ASAPS I-III tended to receive CIVA (I: 8.3% vs. 6.7%; II: 65.5% vs. 46.3%; III: 24.0% vs. 15.0%), whereas a higher proportion of patients with ASAPS IV and above received TIVA (32.0% vs. 2.2%). Patients in the CIVA group had a higher percentage of vasoactive drug usage (25.3% vs. 11.7%) and transfusion (18.0% vs. 5.2%), as well as more intraoperative blood loss (mean [SD]: 150 [439] vs. 68.4 [267]) and transfusion amount (mean [SD]: 75.3 [293] vs. 30.6 [145]). In addition, patients in the CIVA group had longer operating times (median [minimum, maximum], 3.25 [0, 13.1] vs. 2.40 [0, 23.5]) and were more likely to undergo intermediate (61.0% vs. 42.8%) or major surgery (14.0% vs. 12.9%). The proportion of those who underwent gynecological surgery (5.8% vs. 5.1%), gastrointestinal tract surgery (40.2% vs. 23.9%), urological surgery (9.4% vs. 6.8%), thoracic surgery (5.0% vs. 3.8%) and ophthalmic surgery (1.1% vs. 0.5%) was higher.

Propensity score matching and cohort balance

PSMs were conducted at a ratio of 1: 1, 1: 2 and 1: 3. After the three PSMs, the distribution of confounders between the CIVA and TIVA groups was relatively balanced, with the SMD distributions depicted in Supplementary Figure S1. Following 1:3 PSM, 1,536 patients were allocated to the CIVA group, and 4,519 patients were allocated to the TIVA group. All matching variables were well balanced, with SMD less than 0.1. The CIVA group exhibited a higher incidence of 3-year (16.1% versus 13.1%) and 3-month (1.8% versus 1.1%) mortality rates compared to the TIVA group (Table 2).

Table 2

| After propensity score matching | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIVA (N = 4,519) | CIVA (N = 1,536) | p-value | SMD | SMD-0.1 | |

| Outcomes | |||||

| Death 3 years after operation | 593 (13.1%) | 248 (16.1%) | 0.004 | – | – |

| Death 3 months after operation | 50 (1.1%) | 28 (1.8%) | 0.043 | – | – |

| Matching variables | |||||

| Age | 50.5 (15.5) | 50.8 (20.5) | 0.644 | 0.00 | <0.1 |

| Male | 2,355 (52.1%) | 807 (52.5%) | 0.796 | 0.00 | <0.1 |

| BMI | 23.7 (4.46) | 23.6 (5.24) | 0.01 | <0.1 | |

| ASAPS | |||||

| I | 373 (8.3%) | 129 (8.4%) | 0.339 | 0.00 | <0.1 |

| II | 3,059 (67.7%) | 1,011 (65.8%) | 0.03 | <0.1 | |

| III | 1,028 (22.7%) | 367 (23.9%) | 0.02 | <0.1 | |

| IV and higher | 59 (1.3%) | 29 (1.9%) | 0.05 | <0.1 | |

| Duration of surgery | 3.12 [0, 12.7] | 3.22 [0, 13.1] | 0.089 | 0.03 | <0.1 |

| Tumor type | |||||

| ENT tumor | 75 (1.7%) | 19 (1.2%) | 0.733 | 0.04 | <0.1 |

| Gynecological tumor | 307 (6.8%) | 91 (5.9%) | 0.03 | <0.1 | |

| Gastrointestinal tract tumor | 1764 (39.0%) | 610 (39.7%) | 0.00 | <0.1 | |

| Orthopedic tumor | 254 (5.6%) | 86 (5.6%) | 0.00 | <0.1 | |

| Urological tumor | 438 (9.7%) | 145 (9.4%) | 0.01 | <0.1 | |

| General surgery tumor | 959 (21.2%) | 351 (22.9%) | 0.05 | <0.1 | |

| Nervous system tumor | 452 (10.0%) | 140 (9.1%) | 0.03 | <0.1 | |

| Thoracic tumor | 222 (4.9%) | 77 (5.0%) | 0.00 | <0.1 | |

| Ophthalmic tumor | 48 (1.1%) | 17 (1.1%) | 0.01 | <0.1 | |

| Previous surgical history | 1,449 (32.1%) | 500 (32.6%) | 0.748 | 0.01 | <0.1 |

| Previous heart disease | 101 (2.2%) | 53 (3.5%) | 0.012 | 0.04 | <0.1 |

| Previous diabetes | 284 (6.3%) | 109 (7.1%) | 0.291 | 0.02 | <0.1 |

| Previous hypertension | 965 (21.4%) | 337 (21.9%) | 0.655 | 0.00 | <0.1 |

| Previous cerebral infarction | 80 (1.8%) | 26 (1.7%) | 0.93 | 0.01 | <0.1 |

| History of drinking | 560 (12.4%) | 198 (12.9%) | 0.642 | 0.01 | <0.1 |

| History of smoking | 866 (19.2%) | 311 (20.2%) | 0.373 | 0.02 | <0.1 |

| Surgery grade | |||||

| Intermediate | 2,763 (61.1%) | 932 (60.7%) | 0.532 | 0.02 | <0.1 |

| Major | 674 (14.9%) | 217 (14.1%) | 0.02 | <0.1 | |

| Minor | 1,082 (23.9%) | 387 (25.2%) | 0.04 | <0.1 | |

| Emergency surgery | 536 (11.9%) | 186 (12.1%) | 0.831 | 0.01 | <0.1 |

| Shift change of anesthesiologist | 891 (19.7%) | 329 (21.4%) | 0.933 | 0.01 | <0.1 |

| Night shift (18:00 ~ 8:00) | 296 (6.6%) | 99 (6.4%) | 0.161 | 0.03 | <0.1 |

| Transfusion | 658 (14.6%) | 264 (17.2%) | 0.015 | 0.05 | <0.1 |

| Intraoperative blood loss | 122 (345) | 139 (402) | 0.142 | 0.03 | <0.1 |

| Intraoperative blood transfusion amount | 61.0 (215) | 71.6 (288) | 0.188 | 0.03 | <0.1 |

| Intraoperative vasoactive drugs | 1,112 (24.6%) | 375 (24.4%) | 0.906 | 0.02 | <0.1 |

Data of cancer patients undergoing tumor resection after 1: 3 propensity score matching.

TIVA = total intravenous anesthesia; CIVA = combined inhalation and intravenous anesthesia; SMD=Standard mean deviation; BMI=Body Mass index; ASAPS = American society of Anesthesiologists physical status; ENT surgery = ear, nose, and throat surgery. Data are presented as the number (percentage) for categorical variables and as the mean ± SD or median (minimum, maximum) for continuous variables, as appropriate. The independent samples t-test was used to compare continuous variables and the chi-square test to compare categorical variables between groups. p-value <0.05 was marked in bold.

Survival outcomes and association analyses

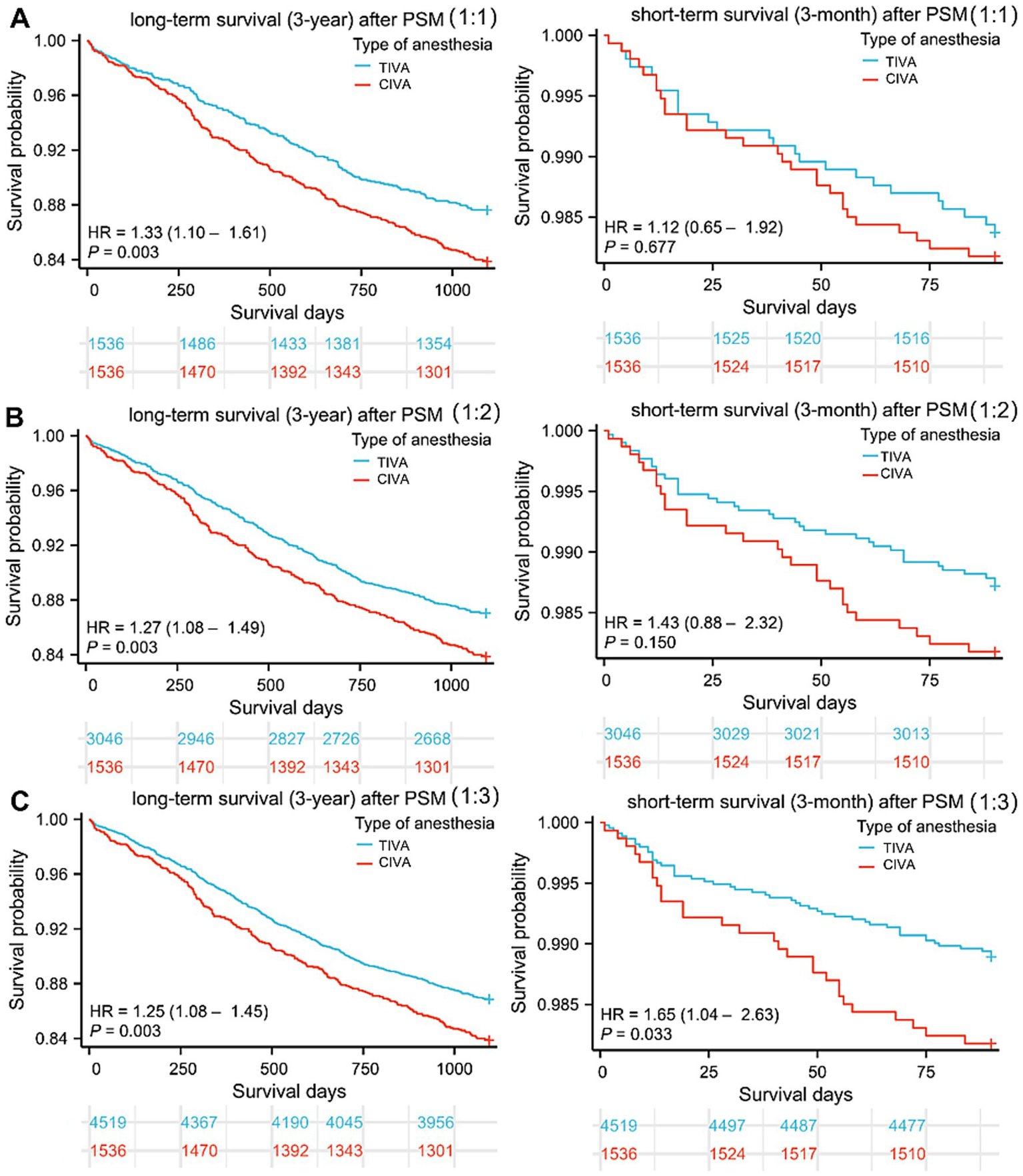

As shown in the Figure 2, the survival curve of CIVA group patients was significantly higher than that of TIVA group patients in three PSM cohorts, irrespective of 3-year or 3-month death after cancer surgery. CIVA was significantly associated with reduced 3-year survival, as indicated by statistically significant HR values across all three PSM cohorts. However, CIVA did not exhibit a significant association with the 3-month survival period. The HRs from the various Cox regression models are presented in Table 3. For 3-year postoperative survival, the HR for CIVA remained relatively stable across both the pre-PSM and the three post-PSM cohorts. Prior to PSM, CIVA was associated with a HR of 1.845 (95% CI: 1.620 to 2.101) for 3-year mortality. After PSM, the HR slightly decreased but retained its statistical significance. Following 1:3 matching, there were still differences in cardiac history and blood transfusion between the CIVA and TIVA groups (p < 0.05). Consequently, a multivariate Cox regression model was employed for adjustment, and even after adjustment, CIVA was still associated with reduced 3-year survival [HR: 1.210 (95% CI: 1.043–1.404)] but not with 3-month survival [HR: 1.574 (95% CI: 0.990–2.501)].

Figure 2

Survival curves after tumor resection. (A–C) Three-year and three-month follow-up survival days of patients in CIVA and TIVA group following 1:1, 1:2, and 1:3 PSM. HR: Hazard ratios; CIVA: combined anesthesia; TIVA: total intravenous anesthesia.

Table 3

| Long-term survival (three-year) | Short-term survival (three-month) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P-value | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P-value | |

| Model 1 (before PSM) | ||||||

| TIVA | Reference | Reference | ||||

| CIVA | 1.845 | 1.620, 2.101 | <0.001 | 2.318 | 1.568, 3.425 | <0.001 |

| Model 2 (After 1: 1 PSM) | ||||||

| TIVA | Reference | Reference | ||||

| CIVA | 1.334 | 1.104, 1.611 | 0.003 | 1.122 | 0.654, 1.923 | 0.677 |

| Model 3 (After 1: 2 PSM) | ||||||

| TIVA | Reference | Reference | ||||

| CIVA | 1.269 | 1.083, 1.487 | 0.003 | 1.428 | 0.879, 2.321 | 0.150 |

| Model 4 (After 1: 3 PSM) | ||||||

| TIVA | Reference | Reference | ||||

| CIVA | 1.254 | 1.081, 1.454 | 0.003 | 1.654 | 1.041, 2.627 | 0.033 |

| Model 5 (After 1: 3 PSM and adjusted) | ||||||

| TIVA | Reference | Reference | ||||

| CIVA | 1.210 | 1.043, 1.404 | 0.012 | 1.574 | 0.990, 2.501 | 0.055 |

Cox regression analysis for long-term survival (three-year) and short-term survival (three-month) in the cancer patients underwent tumor resection.

TIVA = total intravenous anesthesia; CIVA = combined inhalation and intravenous anesthesia; variables with P < 0.05 are included in the multivariate COX regression analysis (Model 4) for adjustment. Bold values indicate statistical significance (p < 0.05).

Subgroup analysis within the CIVA group

To explore heterogeneity, a post hoc analysis was performed comparing outcomes between patients receiving CIVA with desflurane (n = 489) versus sevoflurane (n = 1,072). Baseline characteristics were largely comparable between the two subgroups (Supplementary Table S1), except for a difference in gender distribution (p < 0.05). After adjusting for gender in Cox regression models, no statistically significant difference in 3-year survival (adjusted HR: 0.84, 95% CI: 0.65 to 1.09, p = 0.19) or 3-month survival (adjusted HR: 0.72, 95% CI: 0.34 to 1.54, p = 0.40) was observed between the desflurane and sevoflurane subgroups.

Discussion

Our retrospective cohort study based on PSM, demonstrated that CIVA may decreased postoperative survival of cancer patients, both in univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses. Remarkably, although CIVA was found to significantly impact long-term outcomes, its influence on short-term mortality was not conspicuous.

Experimental studies indicate that volatile anesthetics influence tumor biology through multiple pathways. Isoflurane upregulates HIF-1α/2α in renal and prostate cancer cells, enhancing migration and cytoskeletal reorganization—effects attenuated by HIF-1α siRNA or propofol (20, 21). Sevoflurane promotes glioma stem cell proliferation via the HIF pathway (9). In ovarian cancer, sevoflurane and desflurane suppress miR-138 and miR-210, activating HIF-1α and driving proliferation and migration, reversible with miRNA mimics (22). Huitink et al. (23) compared how various volatile anesthetics affect gene expression in brain and breast tumor cells. They found that anesthetics modulate tumor cell genes in a time-dependent and agent-specific manner, likely due to structural or concentration differences. Altered genes included those linked to DNA repair, metastasis, and coagulation (e.g., RBBP8, CENPE, and TFPI). These expression signatures could serve as genetic fingerprints to guide therapy and predict recurrence.

However, propofol can influence the phenotype of tumor cells, inhibiting their proliferation, migration, and invasion. In non-small-cell lung cancer, propofol might inhibit tumor cell proliferation and induce apoptosis via miR-21/PTEN/AKT signaling axis (10). Propofol also inhibited osteosarcoma cell proliferation and invasion in vitro, involving TGFβ-1 downregulation (15), and AMPK/FOXO1-mediated cellular autophagy and endoplasmic reticulum stress (24, 25). Anesthetics may further influence tumors indirectly via immune modulation: regulatory T cells can promote recurrence (26, 27). However, a recent study in colorectal cancer patients found no significant difference in circulating immune cell subsets between propofol- and sevoflurane-based anesthesia (28). Some studies also suggest that propofol may promote tumor metastasis, primarily through the following mechanisms: on one hand, it can directly act on key RNA molecules and related signaling pathways, thereby accelerating tumor progression; on the other hand, it may also indirectly foster a tumor-favorable microenvironment by modulating host immune function and influencing the degree of immunosuppression (29).

Although the relationship between anesthetic agents and tumors has been explored extensively over the past two decades, these results, as presented above, are quite diverse, reflecting the complexity of the issue. Numerous clinical studies have also been conducted on this topic. A retrospective research from the United Kingdom discovered that inhalational anesthesia was related with a higher postoperative mortality after multivariable analysis of known variables (7). The 1-year postoperative mortality with volatile anesthesia was roughly 50% higher than with TIVA. However, the study did not take into account the type and stage of cancer, which had a significant impact on prognosis. A study from Taiwan, China, revealed that colon cancer surgery under propofol anesthesia is related with higher survival regardless of tumor-node-metastasis stage (30). This finding was further corroborated by another investigation focusing on hepatocellular carcinoma (14). However, several retrospective studies on Korean populations had come to inconsistent conclusions, finding no significant association between the type of general anesthetic agents used during surgery and long-term survival after cancer surgery (12, 13). A recent study in Sweden investigated the impact of propofol vs. inhalational volatile anesthetics on survival outcomes in stage 1–3 colorectal cancer patients undergoing surgery from 2014 to 2019. The results showed no significant association between the type of anesthetic agent used and long-term survival or disease-free survival in patients with either colon or rectal cancer (31). Nevertheless, all of these investigations were retrospective, which reduced the credibility of the results. Few randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were available for reference. The only well-sized RCT in this area (so far), the CAN-study, reported the results of at least 5 years of follow-up for breast cancer surgery. They found no difference in survival between patients anesthetized with propofol or sevoflurane for breast cancer surgery (32).

Further high-quality RCTs are required to investigate the impact of various general anesthesia techniques on patient survival outcomes. The profound initial imbalance between exposure groups underscores a dominant institutional preference for TIVA at our center during the study period. While PSM successfully balanced measured confounders, the matched cohort represents a selected subset of TIVA patients comparable to the smaller CIVA group. This may limit the generalizability of our findings to centers with different practice patterns, and results should be interpreted as most applicable to patients with clinical profiles similar to those in our CIVA cohort. However, few clinical studies have investigated the postoperative mortality of cancer patients under combined anesthesia regimens. Since this combined approach is common in Chinese practice, we focused on comparing TIVA with CIVA. Our analysis—using PSM-adjusted Cox models—shows that CIVA is associated with an increased risk of three-year mortality after cancer surgery, suggesting that the inclusion of inhalational agents may adversely affect long-term survival. Furthermore, this study focused on general anesthetic techniques and did not evaluate the role of regional anesthesia, which may offer benefits in postoperative recovery and potentially influence oncological outcomes. Future studies should aim to integrate the effects of regional anesthesia techniques to inform a more comprehensive perioperative strategy.

It is worth noting that our study found that CIVA had no significant impact on short-term survival. The reasons for this differential effect on short-term and long-term survival are not entirely clear. One possibility is that the impact of CIVA on long-term survival is mediated through its effects on tumor recurrence, metastasis, or the immune response (20, 22). Inhaled anesthetics have been shown to modulate immune function and may affect the body’s ability to combat cancer progression over time (20, 22). Further research is necessary to elucidate the underlying mechanisms that account for the observed differences in survival outcomes. Prospective studies with detailed follow-up and biological marker analysis could help to clarify the specific pathways through which CIVA impacts long-term survival. Additionally, understanding the potential biological mechanisms could inform the development of targeted interventions to mitigate the adverse effects of CIVA on long-term survival after cancer surgery.

The research does have certain limitations. Firstly, although propensity score matching was employed to address known confounders, this design remains susceptible to biases inherent to non-randomized data. Additionally, the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage, a critical indicator of cancer severity, was not integrated into the multifactorial model. However, due to the fact that TNM was not included as a routine extractable variable in the perioperative database, TNM data was missing in this study. Future studies should consider including TNM variable to enhance the robustness of the analysis. Additionally, detailed data on perioperative pain management strategies, including specific analgesic agents and techniques, were not available in our dataset. Differences in postoperative analgesia could represent a potential unmeasured confounder affecting long-term outcomes. Lastly, within the CIVA group, we lacked data on the precise concentration of the volatile anesthetic used (sevoflurane or desflurane) and the proportional contribution of inhalation versus intravenous agents to the total maintenance dose. This absence precludes an analysis of a dose–response relationship and limits the granularity with which the ‘CIVA’ exposure can be interpreted, as the biological impact may vary with the relative intensity of each component.

Conclusion

This retrospective analysis suggests an association between anesthetic technique and mortality in patients undergoing cancer surgery. Our results provide indirect evidence of a potential hazard of inhaled anesthetics on long-term survival after cancer surgery, even as a compound in CIVA. However, due to the limitations of this retrospective study, including the lack of tumor TNM staging and other key variables, these findings should be interpreted with caution. Further prospective studies with detailed follow-up and biological marker analysis are needed to elucidate the specific pathways through which CIVA impacts long-term survival.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by ethical committee at Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because the committee did not require written informed consent since only aggregated data that was not personally identifiable to the patient was used.

Author contributions

YW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SP: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XW: Conceptualization, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YY: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PY: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SY: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research was supported by the Bethune Medical Foundation (grant number: bnmr-2021-002), the China International Medical Foundation (grant number: Z-2017-24-2421), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82002100), and Xinjiang Natural Science Foundation of China (2021D01A07).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2026.1659919/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Pilleron S Sarfati D Janssen-Heijnen M Vignat J Ferlay J Bray F et al . Global cancer incidence in older adults, 2012 and 2035: a population-based study. Int J Cancer. (2019) 144:49–58. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31664,

2.

Sullivan R Alatise OI Anderson BO Audisio R Autier P Aggarwal A et al . Global cancer surgery: delivering safe, affordable, and timely cancer surgery. Lancet Oncol. (2015) 16:1193–224. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00223-5,

3.

Enlund M Berglund A Andreasson K Cicek C Enlund A Bergkvist L . The choice of anaesthetic--sevoflurane or propofol- and outcome from cancer surgery: a retrospective analysis. Ups J Med Sci. (2014) 119:251–61. doi: 10.3109/03009734.2014.922649,

4.

Horowitz M Neeman E Sharon E Ben-Eliyahu S . Exploiting the critical perioperative period to improve long-term cancer outcomes. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2015) 12:213–26. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.224,

5.

Snyder GL Greenberg S . Effect of anaesthetic technique and other perioperative factors on cancer recurrence. Br J Anaesth. (2010) 105:106–15. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq164,

6.

Exadaktylos AK Buggy DJ Moriarty DC Mascha E Sessler DI . Can anesthetic technique for primary breast cancer surgery affect recurrence or metastasis?Anesthesiology. (2006) 105:660–4. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200610000-00008,

7.

Wigmore TJ Mohammed K Jhanji S . Long-term survival for patients undergoing volatile versus IV anesthesia for cancer surgery: a retrospective analysis. Anesthesiology. (2016) 124:69–79. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000936,

8.

Perry N Buggy D Ma D . Can anesthesia influence cancer outcomes after surgery?JAMA Surg. (2019) 154:279–80. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.4619

9.

Shi QY Zhang SJ Liu L Chen QS Yu LN Zhang FJ et al . Sevoflurane promotes the expansion of glioma stem cells through activation of hypoxia-inducible factors in vitro. Br J Anaesth. (2015) 114:825–30. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeu402,

10.

Zheng X Dong L Zhao S Li Q Liu D Zhu X et al . Propofol affects non-small-cell lung cancer cell biology by regulating the mir-21/PTEN/AKT pathway in vitro and in vivo. Anesth Analg. (2020) 131:1270–80. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004778,

11.

Sun C Liu P Pei L Zhao M Huang Y . Propofol inhibits proliferation and augments the anti-tumor effect of doxorubicin and paclitaxel partly through promoting ferroptosis in triple-negative breast cancer cells. Front Oncol. (2022) 12:837974. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.837974,

12.

Jun IJ Jo JY Kim JI Chin JH Kim WJ Kim HR et al . Impact of anesthetic agents on overall and recurrence-free survival in patients undergoing esophageal cancer surgery: a retrospective observational study. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:14020. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14147-9,

13.

Yoon S Jung SY Kim MS Yoon D Cho Y Jeon Y . Impact of propofol-based total intravenous anesthesia versus inhalation anesthesia on long-term survival after cancer surgery in a nationwide cohort. Ann Surg. (2023) 278:1024–31. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005568,

14.

Lai HC Lee MS Lin C Lin KT Huang YH Wong CS et al . Propofol-based total intravenous anaesthesia is associated with better survival than desflurane anaesthesia in hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective cohort study. Br J Anaesth. (2019) 123:151–60. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.04.057,

15.

Xu YB Jiang W Zhao FR Li G Du QH Zhang MY et al . Propofol suppresses invasion and induces apoptosis of osteosarcoma cell in vitro via downregulation of TGF-beta1 expression. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. (2016) 20:1430–5.

16.

Li ML Qi JL Ma YQ Shu W Xiao HD Wang LJ et al . National age-specific mortality trends for cervical and breast cancers in urban-rural areas of China from 2009 to 2021: a population-based analysis. Mil Med Res. (2024) 11:55. doi: 10.1186/s40779-024-00561-4,

17.

Liu J Zhang L Yan Y Zhou Y Yin P Qi J et al . Excess mortality in Wuhan city and other parts of China during the three months of the covid-19 outbreak: findings from nationwide mortality registries. BMJ. (2021) 372:n415. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n415,

18.

Zhao ZP Wang LM Li YC Jiang Y Zhang M Huang ZJ et al . Provincial representativeness assessment of China non-communicable and chronic disease risk factor surveillance system in 2013. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. (2018) 52:165–9. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-9624.2018.02.009,

19.

Liu S Wu X Lopez AD Wang L Cai Y Page A et al . An integrated national mortality surveillance system for death registration and mortality surveillance, China. Bull World Health Organ. (2016) 94:46–57. doi: 10.2471/BLT.15.153148,

20.

Benzonana LL Perry NJ Watts HR Yang B Perry IA Coombes C et al . Isoflurane, a commonly used volatile anesthetic, enhances renal cancer growth and malignant potential via the hypoxia-inducible factor cellular signaling pathway in vitro. Anesthesiology. (2013) 119:593–605. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31829e47fd,

21.

Huang H Benzonana LL Zhao H Watts HR Perry NJ Bevan C et al . Prostate cancer cell malignancy via modulation of HIF-1α pathway with isoflurane and propofol alone and in combination. Br J Cancer. (2014) 111:1338–49. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.426,

22.

Ishikawa M Iwasaki M Zhao H Saito J Hu C Sun Q et al . Sevoflurane and desflurane exposure enhanced cell proliferation and migration in ovarian cancer cells via mir-210 and mir-138 downregulation. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:22. doi: 10.3390/ijms22041826,

23.

Huitink JM Heimerikxs M Nieuwland M Loer SA Brugman W Velds A et al . Volatile anesthetics modulate gene expression in breast and brain tumor cells. Anesth Analg. (2010) 111:1411–5. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181fa3533,

24.

Dai L Li S Li X Jiang B . Propofol inhibits the malignant development of osteosarcoma u2OS cells via AMPK/FOmicronChiO1-mediated autophagy. Oncol Lett. (2022) 24:310. doi: 10.3892/ol.2022.13430,

25.

Wei H Du X Zhao H Sun P Yang J . Propofol regulates ER stress to inhibit tumour growth and sensitize osteosarcoma to doxorubicin. Int J Clin Pract. (2023) 2023:3093945. doi: 10.1155/2023/3093945,

26.

Antonioli L Pacher P Vizi ES Hasko G . CD39 and CD73 in immunity and inflammation. Trends Mol Med. (2013) 19:355–67. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.03.005,

27.

Baghbani E Noorolyai S Shanehbandi D Mokhtarzadeh A Aghebati-Maleki L Shahgoli VK et al . Regulation of immune responses through CD39 and CD73 in cancer: novel checkpoints. Life Sci. (2021) 282:119826. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119826,

28.

Oh CS Park HJ Piao L Sohn KM Koh SE Hwang DY et al . Expression profiles of immune cells after propofol or sevoflurane anesthesia for colorectal cancer surgery: a prospective double-blind randomized trial. Anesthesiology. (2022) 136:448–58. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000004119,

29.

Jiang S Liu Y Huang L Zhang F Kang R . Effects of propofol on cancer development and chemotherapy: potential mechanisms. Eur J Pharmacol. (2018) 831:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.04.009

30.

Wu ZF Lee MS Wong CS Lu CH Huang YS Lin KT et al . Propofol-based total intravenous anesthesia is associated with better survival than desflurane anesthesia in colon cancer surgery. Anesthesiology. (2018) 129:932–41. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002357,

31.

Enlund A Nikberg M Berglund A Ostberg E Enlund M . Total intravenous or inhalational volatile anaesthesia and survival after colorectal cancer surgery: a swedish national registry study. Anaesthesia. (2025) 80:386–94. doi: 10.1111/anae.16495,

32.

Enlund M Berglund A Enlund A Lundberg J Warnberg F Wang DX et al . Impact of general anaesthesia on breast cancer survival: a 5-year follow up of a pragmatic, randomised, controlled trial, the CAN-study, comparing propofol and sevoflurane. EClinicalMedicine. (2023) 60:102037. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102037,

Summary

Keywords

combined inhalation and intravenous anesthesia, propensity score matching, short/long-term mortality, total intravenous anesthesia, tumor resection

Citation

Wang Y, Wu X, Pei S, Chu Y, Yang Y, Lin Y, Ba D, Yin P, Wang J and Yao S (2026) Comparison of total intravenous anesthesia and combined inhalation and intravenous anesthesia on survival after tumor surgery: a propensity score matched cohort study. Front. Med. 13:1659919. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2026.1659919

Received

13 July 2025

Revised

16 January 2026

Accepted

22 January 2026

Published

11 February 2026

Volume

13 - 2026

Edited by

Pradipta Bhakta, Midland Regional Hospital at Tullamore, Ireland

Reviewed by

Hui Zheng, Peking Union Medical College Hospital (CAMS), China

Mohan Mugawar, Midland Regional Hospital at Tullamore, Ireland

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Wang, Wu, Pei, Chu, Yang, Lin, Ba, Yin, Wang and Yao.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shanglong Yao, yaoshanglong@hust.edu.cn; Peng Yin, yinpeng@ncncd.chinacdc.cn; Jie Wang, jiewang1971@hust.edu.cn

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.