Abstract

Anthraquinones (AQs) are chemical scaffolds that have been used both naturally and synthetically for centuries in the food, pharmaceutical, cosmetic and paint industries. AQs, such as citreorosein and emodin, are common additives in antifouling paints which help prevent the global issue of biofouling. To determine the antifouling potential of a family of structurally related compounds nineteen AQs (1–19), were tested for their microbial growth and biofilm adhesion inhibition activity against three marine biofilm forming bacteria, Vibrio carchariae, Pseudoalteromonas elyakovii and Shewanella putrefaciens. More than three-quarters of the tested AQ compounds exhibited activity against both V. carchariae and P. elyakovii at 10 μg/ml whilst exhibiting low antimicrobial effects. The most active compounds (1, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 14, 15, 18, 19) were tested for their minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) which highlighted that all the tested compounds were highly effective at inhibiting the biofilm growth of P. elyakovii at a very low concentration of 0.001 μg/ml. The variability in MIC for inhibiting the biofilm growth of V. carchariae was assessed by analysing the structure-activity relationships (SARs) between the AQ compounds, and the key structural features leading to improved biofilm growth inhibition activity are reported. Molecular docking analysis was also performed to assess whether interruption of quorum sensing in V. carchariae could be a possible mode of action for the antifouling activity observed.

1 Introduction

Almost 75% of the marketed bioactive compounds are natural products isolated from living organisms or their semi-synthetic derivatives (Locatelli, 2011). Compounds from natural sources often have biological activity, modulating several targets, which may be effective for the development of new pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals and other products. These natural compounds can be extracted from plants, marine organisms, or microorganism fermentation broths. Amongst these, anthraquinones (AQs) are some of the most explored natural products (Locatelli, 2011). AQs are a class of phenolic compounds characterized by a 9,10-anthracenedione (also called 9,10-dioxoanthracene) core structure substituted by three fused benzene rings with two ketone functional groups on the central ring. The first anthraquinone was encountered in 1840 when Laurent oxidized anthracene to synthesize anthraquinone and entitled the chemical “anthracenuse”, whilst independently the same compound was termed “oxanthracen” by Demselben (1840). Interestingly, the presently used name “anthraquinone” was only given by Graebe and Libermann in the year 1868 almost three decades later (Graebe, 1890). In 1873, Fittig proposed the correct diketone structure of AQ (Malik et al., 2021). Because of their myriad of biological properties, anthraquinones are a significant class of bioactive compound (Fouillaud et al., 2016).

In nature, AQs occur either as glycosides (i.e., linked to a sugar moiety) or as their free aglycones (Stompor-Gorący, 2021). AQ analogues are a large group of mostly colourful polyketides, existing in either oxidized (anthraquinones) or reduced forms (anthrones, anthranols), or as dimers (dianthrones). Reduction of AQs results in the formation of unstable anthrahydroquinones and oxyanthrones (Diaz-Muñoz et al., 2018). The bioactivity of AQs depends on their chemical structure and is correlated with the existence of hydroxyl groups at the C-1 to C-8 positions in the aromatic ring, a substituent at C-3 and the number of sugar moieties (Diaz-Muñoz et al., 2018). So far, approximately 700 molecules featuring AQ skeletons have been characterised, out of which nearly 200 have been isolated from plants, while the remaining ones have been isolated from bacteria, lichens, fungi, and sponges or other marine invertebrates (Diaz-Muñoz et al., 2018).

Interest in AQs arises from the fact that these chemical scaffolds that have been reported to have numerous biological activities, such as laxative (Malik and Müller, 2016), antifungal (Wuthi-udomlert et al., 2018), antibacterial (Malmir et al., 2017), antimalarial (Osman and Ismail, 2018), anti-inflammatory (Kshirsagar et al., 2014; Chien et al., 2015), antiarthritic (Kshirsagar et al., 2014), diuretic (Chien et al., 2015), antiplatelet (Wu et al., 2007; Seo et al., 2012), neuroprotective (Jackson et al., 2013), and anticancer activity (Huang et al., 2007; Srinivas et al., 2007; Malik et al., 2015; Fouillaud et al., 2016; Tian et al., 2020). In addition to their bioactivity, many natural and synthetic anthraquinones are used in the textiles, paints, devices and biochips, foods, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals industries and as imaging photocleavable protecting groups (Furuta et al., 2001; Patnaik et al., 2007; Shaw, 2009; Caro et al., 2012; Dufossé, 2014; Malik et al., 2015). Some AQs have also been identified as effective catalysts in many chemical and biogeochemical processes like the degradation of contaminants based on their redox potential (Forti et al., 2007; Uchimiya and Stone, 2009). Additionally, there is research into novel approaches of functionalization of anthraquinones, and integrating co-polymeric nanostructures designed for photodynamic treatments (Amantino et al., 2020). Various AQs have been patented for use in building materials to deter destruction by pests, birds and fungi, highlighting their commercial value (Ballinger, 2015). While AQs in general have not been extensively explored for their antifouling potential, in the patent literature there is ample evidence for their potential suitability for use as additives in antifouling coatings to prevent marine biofouling (Shanghai Min Xuan Steel Structure Work Co Ltd, 2022; No 750 Test Field of China Shipbuilding Industry Corp, 2020). Interestingly, citreorosein and emodin have been reported to show strong antifouling activity against Balanus amphitrite larvae settlement (Bao., 2013). These findings prompted us to further explore analogues of these AQ compounds for their AF potential.

Biofouling refers to an overgrowth of both micro and macro-organisms on subsea surfaces. When this process occurs on oil and gas and offshore renewable energy installations situated in the marine environment, it can lead to structural degradation which results in economic losses for these industries (Li and Ning, 2019). The shipping industry is also negatively affected by biofouling as attachment of organisms to the hulls of ships leads to increased fuel consumption (Schultz et al., 2011) which in turn further contributes to global greenhouse gas emissions. From an ecological perspective, transportation of foreign organisms via ships can lead to an introduction of invasive species into marine ecosystems, causing devastating effects on marine biodiversity in these areas (Molnar et al., 2008).

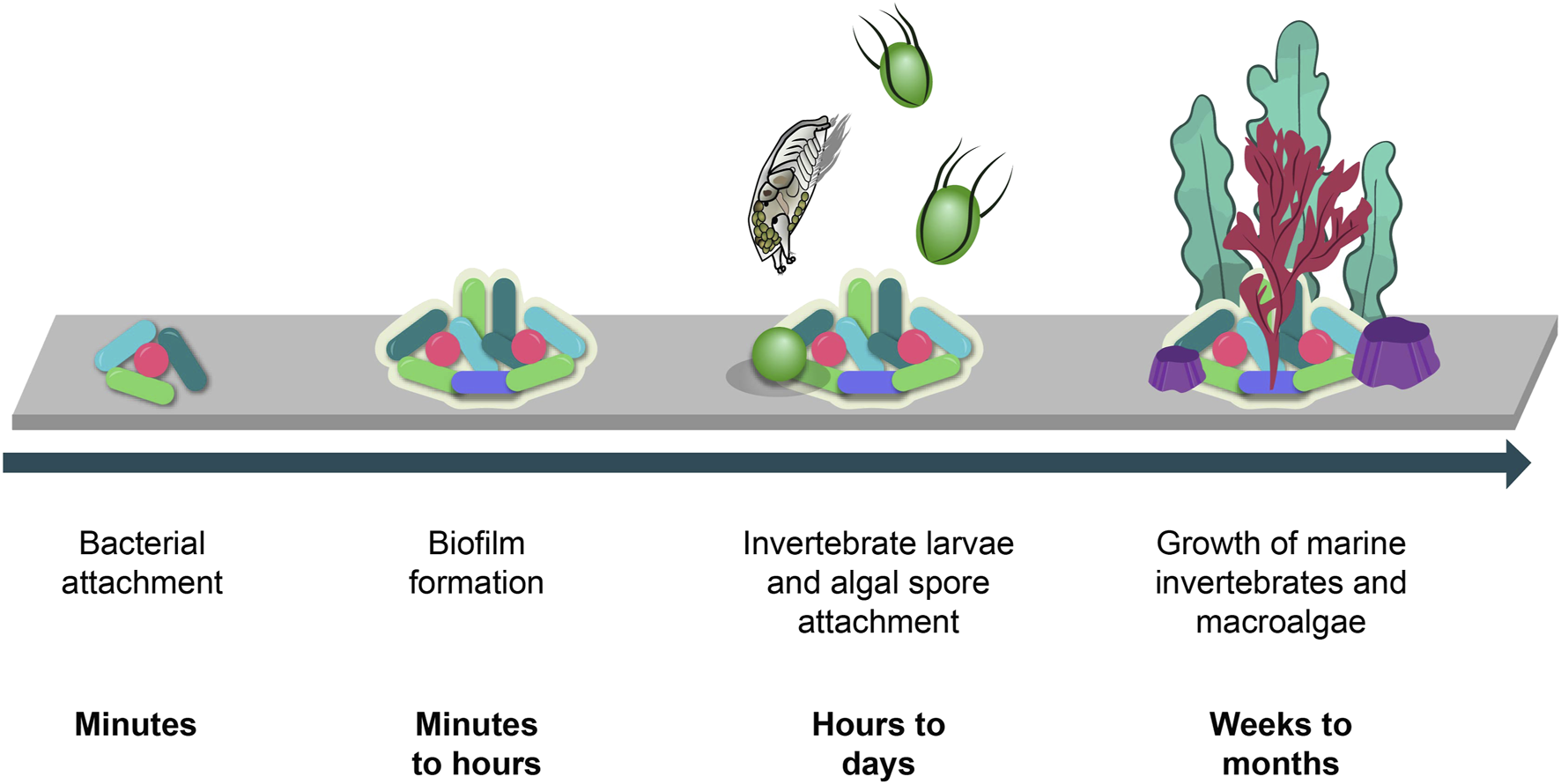

Biofouling is a rapidly occurring process which begins with the attachment of bacterial and diatomic cells to a submerged surface (Figure 1). These cells accumulate and aggregate over a short period of time to form a marine biofilm. Marine biofilms play an important role in the subsequent attraction of macro-organism larvae which are encouraged to settle on these surfaces via a variety of settlement cues (Dobretsov and Rittschof, 2022) Macro-organisms such as mussels, barnacles, hard corals and macroalgae then grow on the surface and, over time, form a dense accumulation of strongly attached organisms which are persistent and hence very difficult to remove.

FIGURE 1

Biofouling process and timeline (Gomez-Banderas, 2022).

As a preventative measure, maritime industries coat subsea structures with antifouling paints which are formulated with antifouling-active compounds to help prevent the attachment of these organisms. Recent studies are now showing that these antifouling agents are in fact coastal pollutants and can be harmful to non-target species, rendering them unsuitable for use in marine environments (Gomez-Banderas, 2022). Between August 2014 to May 2020, 182 antifouling-active compounds were isolated from 173 marine organisms (Liu et al., 2020) showing that natural products could be used as inspiration for developing new antifouling agents. Notable success stories include the potent antifouling activity from butenolides isolated from a marine Streptomyces sp. (Xu et al., 2010), halogenated compounds from macroalgae (Piazza et al., 2011; Umezawa et al., 2014; Dahms and Dobretsov, 2017) and bromotyrosine containing compounds from marine sponges (Ortlepp et al., 2007; Hanssen et al., 2014; Tintillier et al., 2020). Most commonly, antifouling activity is conveyed by inhibition of microalgal growth and adhesion, settlement inhibition of invertebrate larvae or algal spores, and inhibition of microbial growth and biofilm adhesion. When testing for bacterial biofilm inhibitory activity, it is important to consider that besides exhibiting a direct antibiotic activity, compounds of interest may also be interrupting the quorum sensing signaling system and hence inhibiting the biofilm growth. Quorum sensing is a communication system used in bacterial communities to allow for synchronized behaviour such as bioluminescence, virulence and the formation of bacterial biofilms (Miller and Bassler, 2001). Although there has been some success in identifying natural products with antifouling activity, many of the known compounds produced by living organisms have not yet been explored for their antifouling potential.

In the present study, we investigate the microbial growth and biofilm adhesion inhibition activity of nineteen structurally diverse anthraquinones when tested against three marine bacterial species which are key players in the marine biofilm formation process. The MIC of the best performing compounds was also determined, and the related structure activity relationships of these compounds are analysed to determine the structural properties which are fundamental in contributing to the biofilm related antifouling activity. Molecular docking analysis was performed in order to obtain an estimate of the strength of binding between the tested compounds and an important protein involved in the quorum sensing signal system.

2 Results

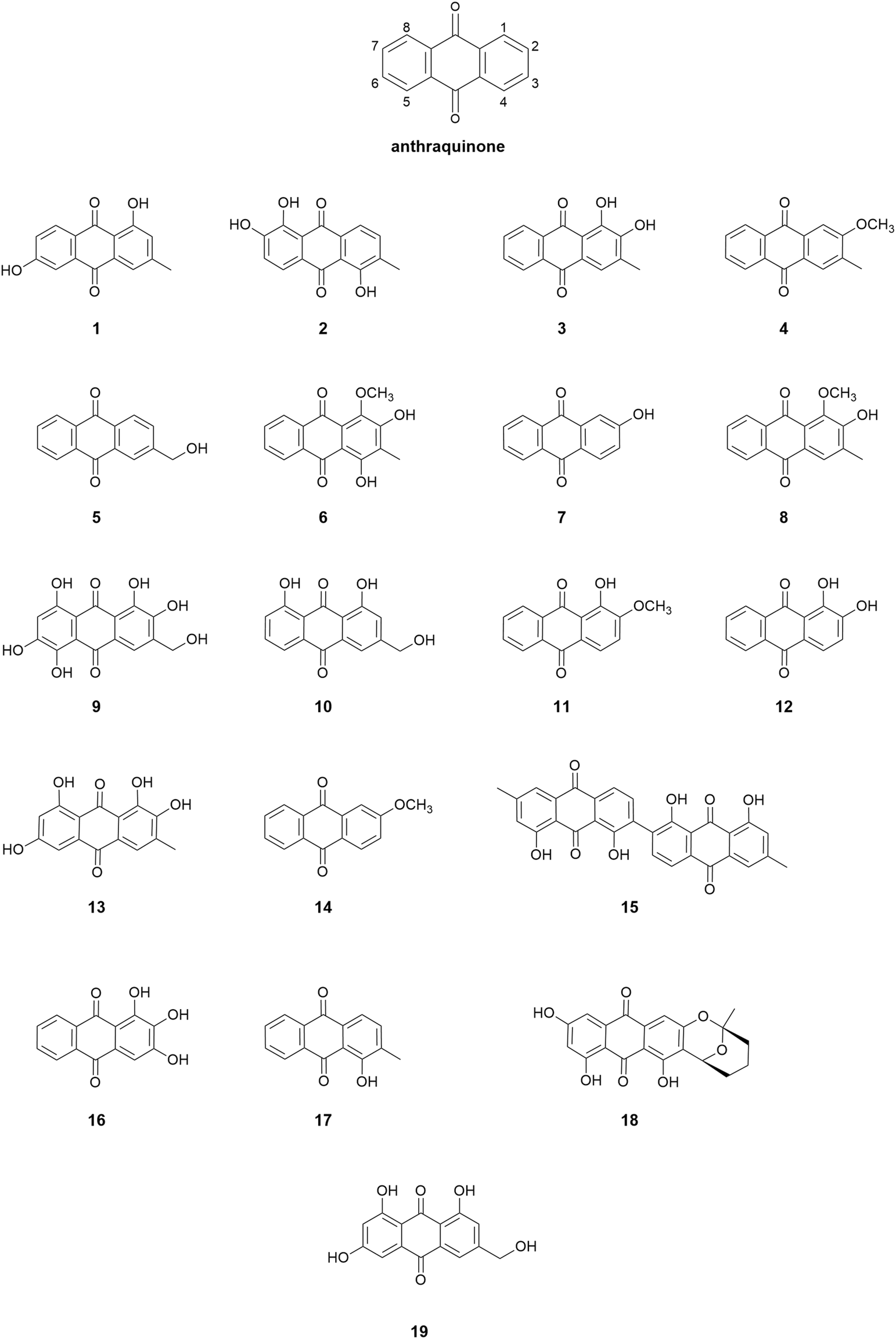

Nineteen structurally diverse AQ compounds (Figure 2), based on the same anthraquinone core structure, were tested for their microbial growth and biofilm adhesion inhibition activity against three marine biofilm forming bacteria: Vibrio carchariae, Pseudoalteromonas elyakovii and Shewanella putrefaciens. Using the DataWarrior software package, a similarity value between the molecules was calculated in a two-step process. Firstly, certain molecule features of all molecules in the dataset were compiled into an abstract molecule description, called descriptor, sometimes are also referred to as fingerprints. In the simplest case the descriptor consists of a binary array of which every bit indicates whether a certain feature is present or not in the molecule. In a second step, these descriptors are converted into the actual similarity value, signifying how much the two compounds have in common, by dividing the number of common features by the number of features being available in any of the two molecules, which is referred to as Tanimoto similarity (Sander et al., 2015). The structural similarity was identified using DataWarrior software where citreorosein was selected as the starting marker and Skelspheres (Sander et al., 2015) were used as molecular descriptor to identify the close similarity between the structures (Supplementary Figures S1, S2).

FIGURE 2

Chemical structures of anthraquinone derivatives used in the study.

For this current study, we chose the following AQ compounds: phomarin (1), morindone (2), 3-methylalizarin (3), 2-methoxy-3-methylanthraquinone (4), 2-hydroxymethylanthraquinone (5), 4-hydroxydigitolutein (6), 2-hydroxyanthraquinone (7), digitolutein (8), asperthecin (9), aloe-emodin (10), alizarin-2-methylester (11), alizarin (12), alaternin (13), 2-methoxyanthraquinone (14), chrysotalunin (15), anthragallol (16), 1-hydroxy-2 methylanthraquinone (17), averufin (18), and citreorosein (19).

2.1 Initial bioactivity screening

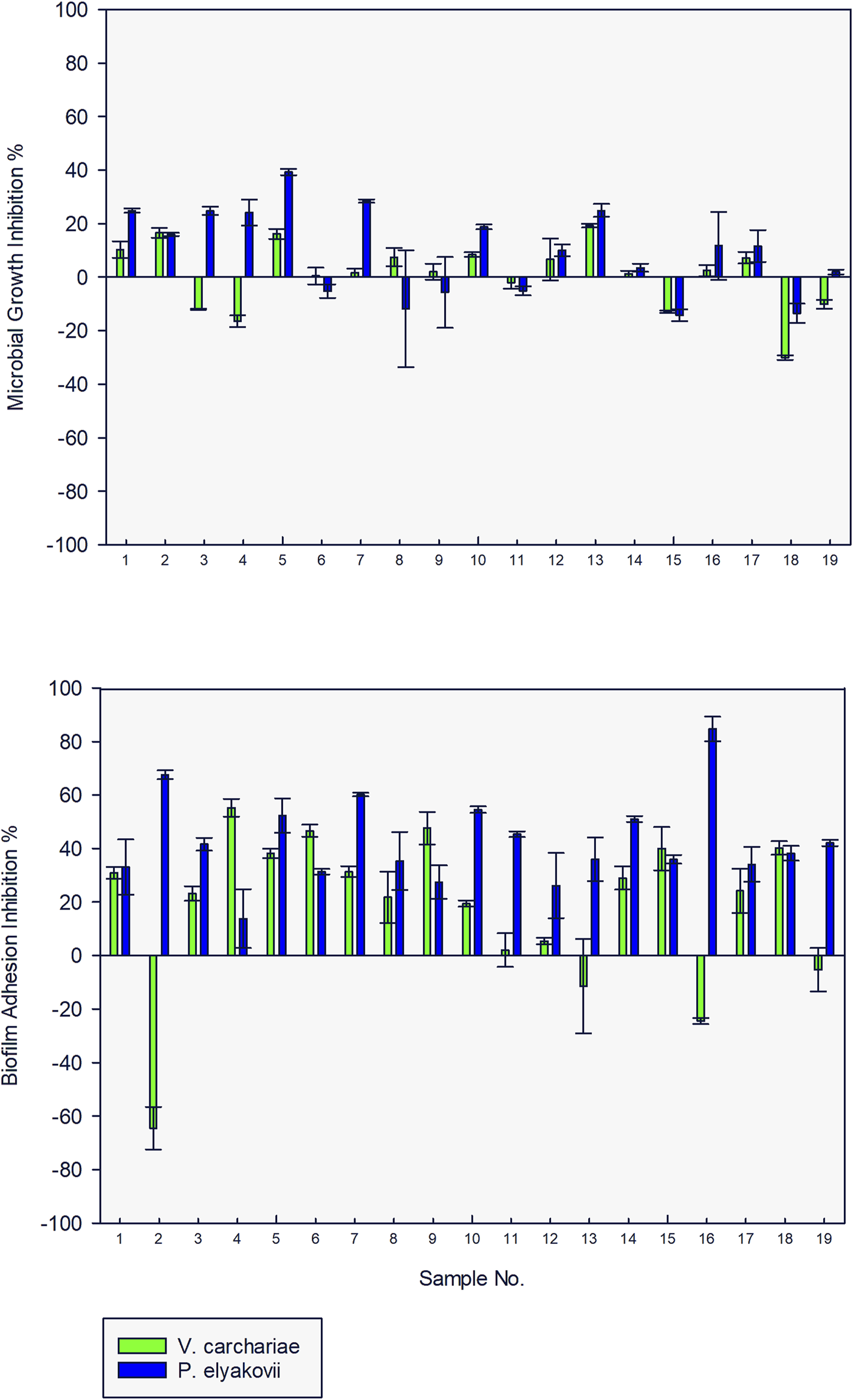

When tested for microbial growth inhibition activity against the three test strains at a concentration of 10 μg/ml, none of the compounds exhibited > 20% inhibition against V. carchariae and only 30% of the compounds inhibited > 20% of the microbial growth of P. elyakovii. In addition, more than 75% of the tested AQ compounds exhibited biofilm adhesion inhibition activity against both V. carchariae and P. elyakovii with many of the compounds inhibiting > 40% of P. elyakovii biofilm growth and > 30% of V. carchariae growth when compared to the untreated controls (Figure 3). Rather surprisingly, in contrast all compounds exhibited microbial growth inhibition and biofilm growth promotion activity when tested against S. putrefaciens, which prompted us to exclude this species from further testing in this study (Supplementary Figure S3).

FIGURE 3

Microbial growth and biofilm adhesion inhibition activity of 19 anthraquinone compounds (10 μg/ml) against V. carchariae and P. elyakovii.

2.2 Minimum inhibitory concentration testing

Ten of the most active AQs from the initial bioactivity screening were further tested at concentrations of 1 μg/ml, 0.1 μg/ml, 0.01 μg/ml, and 0.001 μg/ml to determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) in which more than 5% microbial growth inhibition and biofilm adhesion inhibition activity against V. carchariae and P. elyakovii was observed (Table 1). 10 and 19 were tested alongside these compounds as these are common additives in antifouling and antifungal paints and can be used to determine the efficacy of the AQ analogues in the study.

TABLE 1

| Compound | V. carchariae growth MIC (μg/ml) | V. carchariae adhesion MIC (μg/ml) | P. elyakovii growth MIC (μg/ml) | P. elyakovii adhesion MIC (μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 0.001 |

| 5 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.001 |

| 6 | 0.01 | 0.01 | > 10 | 0.001 |

| 7 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 10 | 0.001 |

| 9 | > 10 | 0.1 | > 10 | 0.001 |

| 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 0.001 |

| 14 | 0.01 | 0.1 | > 10 | 0.001 |

| 15 | > 10 | 0.01 | > 10 | 0.001 |

| 18 | 0.01 | 0.1 | > 10 | 0.001 |

| 19 | > 10 | 0.1 | > 10 | 0.001 |

Microbial growth and biofilm adhesion inhibition activity of the selected AQ compounds (MIC).

All compounds were highly effective at inhibiting the biofilm growth of P. elyakovii at a very low concentration of 0.001 μg/ml, exhibiting a range of biofilm inhibition percentages from 20% to 56%. Additionally, 60% of the compounds have a microbial growth MIC above 10 μg/ml which shows that although the overall growth of the microbes is not affected between 10 μg/ml–0.001 μg/ml, the biofilm adhesion is affected by these compounds. A biofilm adhesion MIC of 0.01 μg/ml was observed for 6, 7, and 15 against V. carchariae, while in general, the compounds tested displayed a larger degree of variation in their activity against this bacterium. 60% of the compounds showed an MIC of 0.01 μg/ml when considering the microbial growth. Interestingly, the commercially applied 10 showed one of the highest microbial growth and biofilm adhesion MICs against V. carchariae of 10 μg/ml.

2.3 Structure-activity relationship analysis

Upon closer observation of the MIC data for the 10 AQs selected, some interesting trends can be derived which connect the exhibited biofilm adhesion inhibition bioactivity against V. carchariae with the structural features of the most structurally similar 8 AQ compounds. Due to the important relationship between biofilm formation and the subsequent attachment of macro-fouler larvae (Dobretsov and Rittschof, 2022), it is important to study possible mechanisms as to how compounds are inhibiting biofilm adhesion. The data demonstrates that the introduction of phenolic hydroxyl (OH) groups at position 2 and 4 position of the AQ skeleton as present in 6 and 7, gives the lowest MIC of 0.01 μg/ml. When the OH groups on positions 2 and 4 are lacking, as in the case of 1, 5, 14 and 19, the bioactivity is reduced (MIC = 0.1 μg/ml). The addition of OH groups at positions 6 and 8, and the presence of other substituents such as methoxy, methyl or hydroxymethyl groups at position 1, 2 and 3 as in 1, 5, 14 and 19, may also be contributing factors to the lower MIC of 0.1 μg/ml witnessed for these compounds. For 9, the presence of multiple OH groups at positions 5, 6 and 8, and the absence of OH groups at positions at the 2 and 4 results in a 10-fold decrease in inhibitory activity (MIC = 0.1 μg/ml) in comparison to 6 and 7. The absence of OH groups at positions 2 and 4 in the case of 10, alongside the presence of an OH group at position 8, resulted in a 100-fold reduction in inhibitory activity (MIC = 10 μg/ml) compared to the best performing AQs.

2.4 Determination of quorum sensing inhibition activity using molecular docking

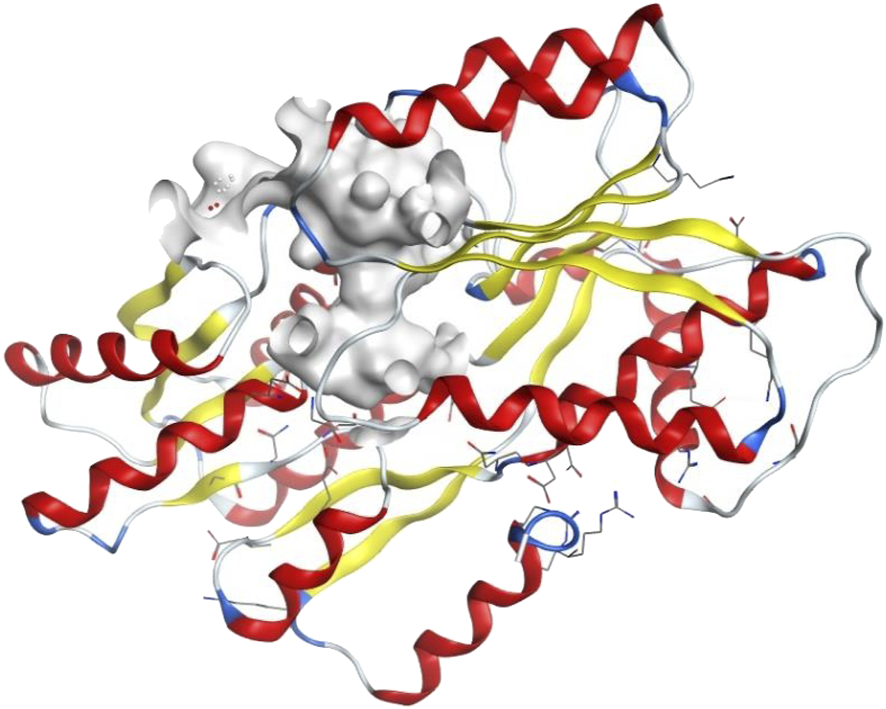

To explore whether the established biofilm inhibitory activity of the studied AQ compounds may be due to potential inhibition of quorum sensing signaling, instead of antibacterial effects, we undertook a molecular docking study. The quorum sensing systems in V. carchariae are well known and involve many different Lux-type proteins (Henke and Bassler, 2004). To gain an insight into the differences in binding between the compounds and the LuxP protein (Figure 4) in V. carchariae, molecular docking (Rigid Receptor Docking (RRD) was performed as per Rajamanikandan et al. (2017). The LuxP protein is an essential binding protein responsible for the transportation of autoinducers which are signaling compounds within the quorum sensing system. LuxP plays an important role near the beginning of the signaling process and hence interrupting the quorum sensing pathway at the beginning could be a favourable approach.

FIGURE 4

The binding site (grey-white colour) of LuxP protein in V. carchariae.

The AQs tested in the MIC study were subjected to docking analysis against LuxP and the specifities of their interaction with this target were investigated. Based on binding energies and interacting residues, the best docked complexes were obtained for 1 (−8.4 kcal/mol), 7 (−7.7 kcal/mol), 10 (−7.7 kcal/mol) and 19 (−8.2 kcal/mol). Four other AQs docked well with slightly lower binding energies, specifically 5 (−7.5 kcal/mol), 6 (−6.9 kcal/mol), 9 (−7.3 kcal/mol) and 14 (−7.5 kcal/mol), whereas AQs 15 (−5.8 kcal/mol), and 18 (−5.3 kcal/mol) did not dock well according to the low binding energies calculated.

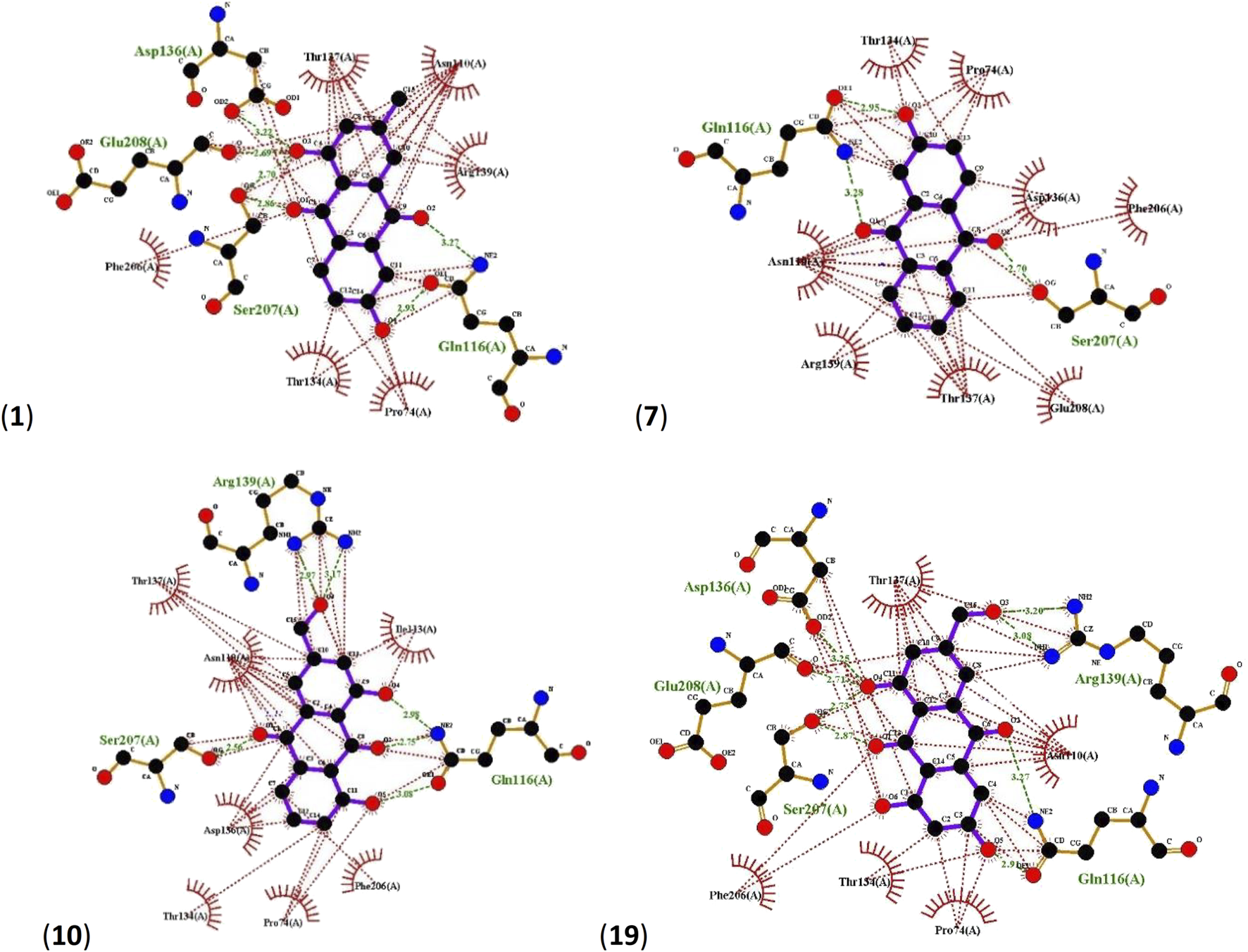

In all four cases, Asp136, Glu208, Ser207, Gln116 and Arg139 residues of LuxP were found to be involved in hydrogen bonding. 1 interacts with LuxP forming H-bonds at the receptor site interacting region involving residues Asp136, Glu208, Ser207 and Gln116. For Asp136 and Glu208, only one interaction between each residue and the ligand was observed with distances of 3.22 Å and 2.69 Å respectively. For Ser207 and Gln116, two interactions per residue could be observed with distances of, 2.70Å and 2.86 Å for Ser207 and 2.93 Å and 3.27 Å for Gln116. LuxP residues Thr137, Asn110, Arg139, Phe206, Thr134 and Pro74 were involved in hydrophobic interactions (Figure 5). The interaction of 7 with LuxP involves three hydrogen bonds, two with the residue Gln116 at distances of 2.95 Å and 3.28 Å and one with Ser207 at a distance of 2.70 Å. Hydrophobic interactions of this compound were found with LuxP residues Thr134, Pro74, Asn110, Arg139, Thr137, Glu208, Phe206 and Asp136 (Figure 5).The interaction of 10 with LuxP involves six hydrogen bonds, two with the residue Arg139 at distances 2.97 Å and 3.17 Å, one with Ser207 at distances 2.56 Å and three with Gln116 at distances 2.98 Å, 2.75 Å and 3.08 Å. Hydrophobic interactions of this compound were found with LuxP residues Thr137, Asn110, Asp136, Pro74, Phe206, Ile113 and Thr134. (Figure 5). Finally, the interaction of 19 with LuxP involves eight hydrogen bonds, two with the residue Arg139 at distances 3.20 Å and 3.08 Å, two with Ser207 at distances 2.73 Å and 2.87 Å, two with Gln116 at distances 2.91 Å and 3.27 Å, one with Glu208 at distance 2.71 Å and one with Asp136 at distance of 3.25 Å. Hydrophobic interactions of this compound were found with LuxP residues Thr137, Asn110, Pro74, Phe206, and Thr134. (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5

Ligplots showing interacting residues of LuxP in complex with AQs 1, 7, 10 and 19. Purple lines, AQ ligands; green dotted lines, hydrogen bonds labelled with distances in Å; red dotted lines, hydrophobic interactions; red circles, oxygen atoms; blue circles, nitrogen atoms.

2.5 Pharmacophore evaluation

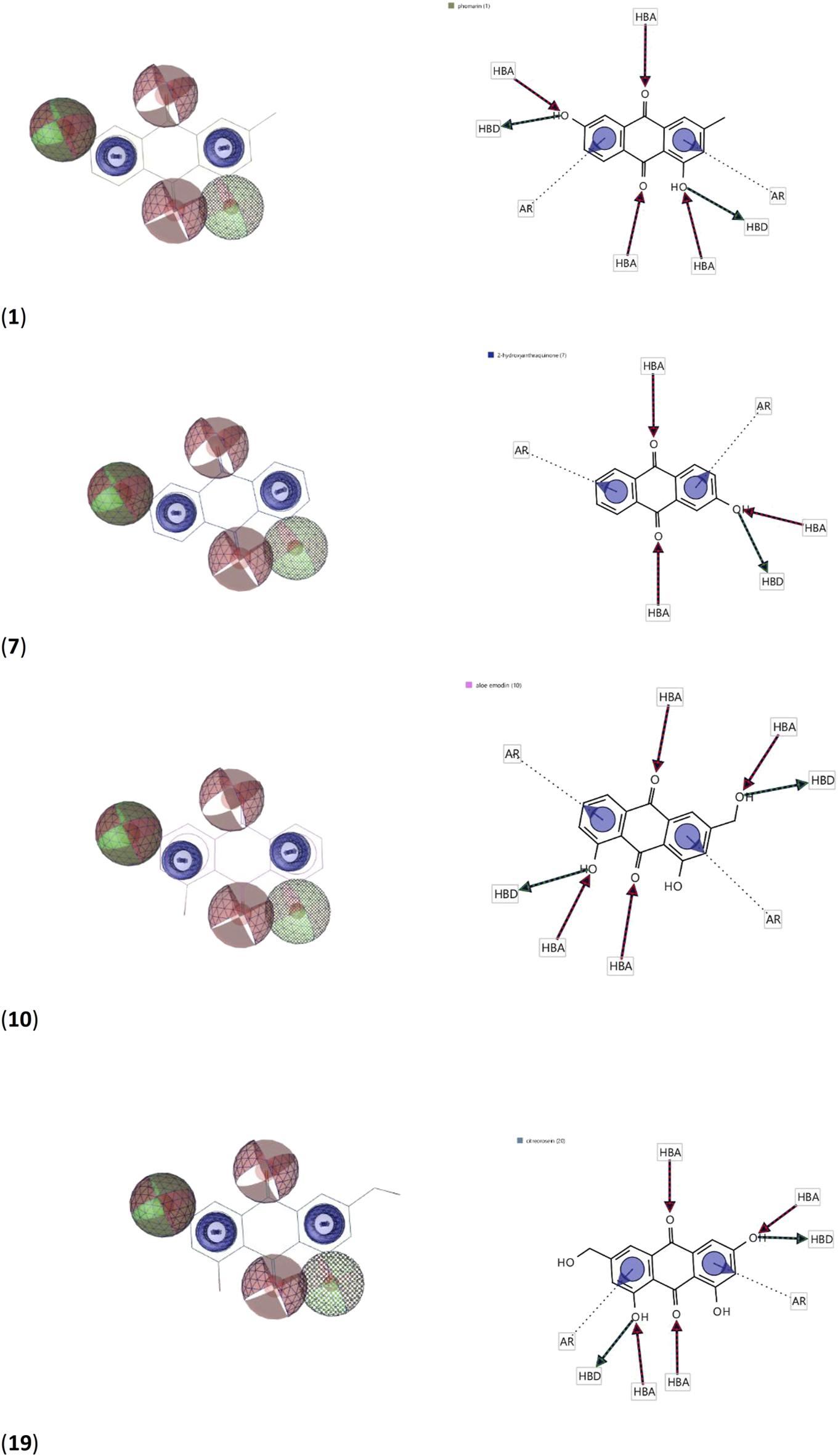

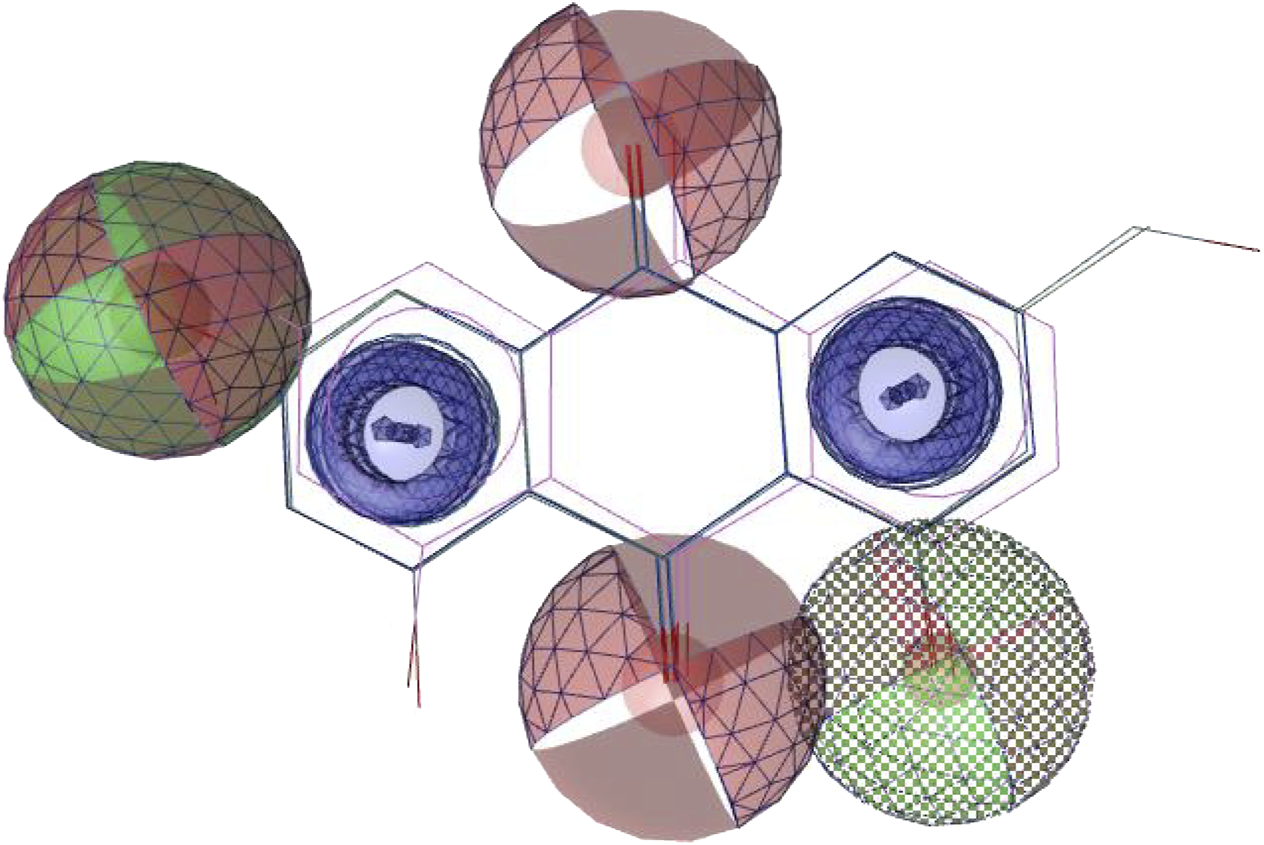

Using the four best docked AQs 1, 7, 10 and 19, a pharmacophore model was generated. The generated pharmacophore showed three main features: hydrogen bond acceptors (HBAs), hydrogen bond donors (HBDs) and aromatic rings (AR). The representative 3D and 2D pharmacophoric features of each compound are shown in Figure 6. Each compound constitutes individual pharmacophoric features and from these individual characteristic pharmacophores, a merged pharmacophore with common features was generated, as shown in Figure 7. This common feature pharmacophore model with a score of 0.9242 showed certain features: two HBDs, four HBAs and two AR.

FIGURE 6

3D and 2D representations of pharmacophoric features of 1, 7, 10 and 19 used in 3D pharmacophore generation. Red, HBAs; green, HBDs; blue, AR.

FIGURE 7

Common feature pharmacophore. Colour codes analogous to Figure 6. Red, HBAs; green, HBDs; blue, AR.

3 Discussion

Citreorosein (19) and emodin have previously shown antifouling activity against macro-organisms and anthraquinones have been used commercially to deter degradation of building materials by pests, birds and fungi and to prevent biofouling related corrosion in the oil and gas industry. This study explored the bioactivity of seventeen analogues of these commercially used compounds and determined the structural features responsible for the bioactivity. Many of the tested compounds exhibited bioactivity at concentrations as low as 0.01 μg/ml and 0.001 μg/ml against V. carchariae and P. elyakovii biofilm production respectively, indicating that exceptionally low amounts of the compounds would need to be incorporated into antifouling paints to exhibit the desired activity against bacterial biofilms. Antimicrobial activity < 5% was also observed for 42% and 61% of compounds against V. carchariae and P. elyakovii at 10 μg/ml respectively, however, the microbial growth inhibition did not exceed 39% in any cases. At lower concentrations, 60% and 20% of the ten tested compounds showed slight antimicrobial effects against V. carchariae and P. elyakovii respectively, not exceeding 25% in any case. This indicates that the studied compounds are not toxic towards the tested strains which is a crucial factor when considering compounds as antifouling agents. Structurally simple anthraquinone compounds such as 2-hydroxyanthraquinone (7) (MIC = 0.01 and 0.001 μg/ml against V. carchariae and P. elyakovii biofilm production respectively) are easy to produce which is advantageous when considering their use as antifouling agents. Interestingly, 6, 7, and 15 exhibited a lower biofilm adhesion MIC against V. carchariae than commercially used 19. Thus, our results, alongside previous studies regarding larval settlement activity of AQs (Bao et al., 2013), present an enhanced insight into the antifouling potential of AQ compounds.

The subsequent analysis of structure activity relationships of the AQs exhibiting the highest activity demonstrated that the presence of phenolic hydroxyl groups at positions 2 and 4 increased biofilm adhesion inhibition activity, while their absence or the addition of OH groups positions 5, 6 and 8 resulted in a 10-fold–100-fold decline in inhibitory activity. From a structural point of view, compounds 15 and 18 were the least similar with the other compounds investigated in this study, and therefore it is possible that the pronounced activity of 15 (0.01 μg/ml against V. carchariae) may be due to the presence of additional aromatic rings within the structure, whereas the presence of an additional sterically demanding heterocyclic ring system in 18 led to reduced activity (0.1 μg/ml).

When considering the antifouling potential of compounds against marine biofilm-forming bacteria, it can be challenging to pinpoint whether the observed activity is a result of antimicrobial or direct antibiofilm effects. One way to determine the mechanisms behind antifouling active compounds is via exploring whether they interrupt the quorum sensing signaling system associated with the production of biofilms. As quorum sensing has been demonstrated to play an important role in the production of virulence factors, stress responses and biofilm formation in V. carchariae, in the present study, we used Rigid Receptor Docking (RRD) to establish the binding mode of the 10 most potent AQs into the binding pocket of LuxP protein in V. carchariae. Multiple poses were generated and evaluated based on binding conformations and common interacting residues at the binding pocket. 1, 7, 10 and 19 showed the best docking to the receptor site with binding energies ranging between −8.4 kcal/mol and −7.7 kcal/mol.

Interestingly, compound 7 was one of the most active AQs in the MIC study, so indeed this compound’s activity may be based on binding to LuxP. In addition, when tested against P. elyakovii, 7 exhibited a high microbial growth MIC of 10 μg/ml whereas it inhibited biofilm adhesion at 0.001 μg/ml which could suggest that the quorum sensing system in P. elyakovii is also disrupted in the presence of this compound. However, further studies including in vivo testing will be required in order to confirm the proposed QS activity.

4 Materials and methods

4.1 Origin of compounds

Supplementary Figures S4-S21; 1H NMR Compounds 1–18 were obtained in a purified form from the compound library maintained at the Marine Biodiscovery Centre, Department of Chemistry, University of Aberdeen, United Kingdom.

Citreorosein (19) was isolated and identified from an unknown fungal strain following a similar approach as outlined in the literature (Kalidhar, 1989; Bao et al., 2013). Orange amorphous powder. ESI-MS m/z 285.0341 [M–H]–. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δH 7.63 (1H, s, H-2), 7.24 (1H, s, H-4), 7.08 (1H, s, H-7), 6.53 (1H, s, H-5), 4.60 (2H, s, H2-15). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC 189.4 (C, C-9), 181.8 (C, C-10), 166.9 (C, C-8), 164.8 (C, C-6), 161.6 (C, C-1), 152.8 (C, C-3), 135.3 (C, C-11), 133.1 (C, C-14), 121.3 (CH, C-2), 117.2 (CH, C-4), 114.5 (C, C-13), 109.7 (CH, C-5), 108.7 (C, C-12), 108.1 (CH, C-7), 62.2 (CH2, C-15).

4.2 Microbial growth inhibition assay

Shewanella putrefaciens, Vibrio carchariae and Pseudoalteromonas elyakovii (NCIMB codes: 540, 12,705 and 13,703 respectively) were obtained from the NCIMB (Aberdeen, United Kingdom). Cultures were prepared in filtered (0.2 μm PVDF, Fisher Scientific) seawater collected from the Ythan estuary, Aberdeen (United Kingdom) enriched with 0.5% peptone (general purpose grade, Fisher Scientific) and grown overnight (28°C, 138 r.p.m, 16 h) to a cell density in the range of 108 CFU/ml. Sample stocks were prepared in DMSO (Acros Organics) and then diluted to the required concentrations using filtered seawater, ensuring that final DMSO concentration in wells did not exceed 0.5% (v/v). Cultures were diluted 1:50 in the previous filtered seawater medium before transferring to the 96-well plate (Costar®, flat bottom, non-treated). Samples and cultures were added to the wells in a 1:1 ratio giving a final volume of 200 μl and all samples were tested in triplicate. The controls were also tested in triplicate and included the 1:50 bacterial cultures with a final concentration of 0.5% DMSO and media control wells. Plates were incubated at 28°C for 48 h and the optical density (OD) of the microbial growth was determine at 620 nm using a microplate reader (Biochrom EZ Read 400). Microbial growth inhibition activity was calculated as follows: 100–(ODsample/ ODcontrol × 100). Experimental errors were expressed as the standard deviation obtained from three replicates.

4.3 Biofilm adhesion inhibition assay

The bioassay method was adapted from the method used by Hanssen et al. (Hanssen et al., 2014). Cultures were prepared as per the microbial growth inhibition assay. Plates were incubated at 28°C for 48 h to allow the biofilms to grow in the presence of the samples. After incubation, liquid contents were removed from the wells and the wells were washed with filtered seawater to remove any planktonic cells. Biofilms were then fixed to the bottom of the wells by drying at 37°C and were then stained using 200 μl of 1% (v/v) crystal violet solution (Pro-Lab Diagnostics). After drying, the biofilms were suspended in 200 μl 70% ethanol [Joseph Mills (Denaturants) Ltd.] and quantified by reading the optical density (OD) at 540 nm using a microplate reader (Biochrom EZ Read 400). Biofilm growth inhibition activity was calculated as follows: 100–(ODsample/ ODcontrol × 100). Experimental errors were expressed as the standard deviation obtained from three replicates.

4.4 Data analysis and visualization

Structure similarity charts showing structure similarity of AQs using SkelSpheres as molecular descriptors were generated using DataWarrior Software (Sander et al., 2015). Structure-activity relationship of AQs were analysed using SAR function in DataWarrior Software to analyse different R-groups at different positions in 8 AQs.

4.5 Molecular docking

Molecular docking analysis was performed using Autodock Vina v.1.2.0 (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA, United States) docking software (Trott and Olson, 2010). The receptor site was predicted using MOE Site Finder program (Molecular Operating Environment, 2022.02.09), which uses a geometric approach to calculate putative binding sites in a protein, starting from its tridimensional structure. This method is not based on energy models, but only on alpha spheres, which are a generalization of convex hulls (Edelsbrunner et al., 1995). The x-ray crystal structure of LuxP in complex with AI-2 (PDB: 1JX6) (Chen et al., 2002) was retrieved from the Protein Data Bank and utilized to perform docking simulations. The box centre and size coordinates were −18.2833 × −9.13497 × 22.3052 and 18.4165 × 9.67157 × 39.6987 around the active site. All coordinates used Angstrom units. Default search parameters were used where number of binding modes were 10, exhaustiveness was 8 and maximum energy difference was 3 kcal/mol. Chimera 1.16 (Pettersen et al., 2004) and LigPlot + software (Laskowski and Swindells., 2011) were used for visualization and calculation of protein–ligand interactions.

4.6 3D pharmacophore model generation

LigandScout (Inte: Ligand) Advanced software (Wolber and Langer, 2005) (evaluation licence key: 81809629175371877209) was used to generate a 3D pharmacophore model. Espresso algorithm was used to generate ligand-based pharmacophore. The generated pharmacophore model compatibility with the pharmacophore hypothesis was created using default settings for LigandScout. The best model was selected from the four generated models.

5 Conclusion

Biofouling in the marine environment is a huge challenge for the maritime industries due to the associated costs and increased labour required to remove fouling from immersed structured and the hulls of ships. Due to the increase of studies presenting the negative impacts of current antifouling agents on marine environments, it is necessary to find new, non-toxic antifouling active compounds. Natural products, such as anthraquinones citreorosein and emodin, have been previously reported to show antifouling activity against marine invertebrate larvae and have been found to be implemented into some antifouling paints.

In this study, nineteen AQ compounds were tested for their marine bacterial growth and biofilm adhesion inhibition activity, of which ten compounds were further tested to determine their minimum inhibitory concentrations. In particular, compounds 6, 7, and 15 exhibited a very low minimum inhibitory concentration (0.01 μg/ml) when tested for biofilm inhibition activity against V. carchariae. All ten compounds in the MIC study showed an impressively low MIC of 0.001 μg/ml against P. elyakovii. The compounds did not exhibit antimicrobial effects above 39% and were hence not deemed as toxic against the tested strains. When the structural features of the most structurally similar AQs in the study were compared with their associated MIC values for V. carchariae biofilm adhesion, it was found that the presence of phenolic hydroxyl groups at positions 2 and 4 position of the aromatic ring was an important for activity, while the presence of additional aromatic moieties increased the activity when compared with the other compounds. Molecular docking analysis was performed on the ten most effective AQ compounds to determine whether the compounds bind to an important protein in the quorum sensing signaling system in V. carchariae. Compounds 1, 7, 10 and 19 gave binding potentials associated with the possibility of QS inhibition activity indicating that the bioactivity observed for these compounds is likely due to antibiofilm and not antimicrobial effects. From these results, a pharmacophore model was proposed to help guide future studies.

Moving forward, attention should be focused on the least structurally complex anthraquinones which show good bioactivity and are simple, and cost effective, to synthesise. Additionally, the proposed pharmacophore model should be used as a future guide for selecting AQ compounds for antifouling purposes. The results in this current study indicate that AQs can be highly effective against marine biofilm forming bacteria at impressively low concentrations without showing toxicity effects, however, bioactivity testing for larval and algal spore settlement activities of the compounds in this study is required to further confirm their abilities as antifouling agents for the maritime industries.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, GP; methodology, GP and JG-B.; software, GP; validation, GP, JG-B., MJ, and RE; formal analysis, GP and JG-B.; investigation, GP and JG-B.; writing—original draft preparation, GP and JG-B.; writing—review and editing, all co-authors; supervision, MJ and RE. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Net Zero Technology Centre and the University of Aberdeen, through their partnership in the United Kingdom National Decommissioning Centre and Albrn Care, India.

Acknowledgments

We thank the late Professor R. H. Thomson for donating the pure compounds used in the study to the compound library of the Marine Biodiscovery Centre. The authors are grateful to Professor Bruce Milne (University of Coimbra, Portugal) for helpful comments regarding the molecular docking studies.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fntpr.2022.990822/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Amantino C. F. de Baptista-Neto Á. Badino A. C. Siqueira-Moura M. P. Tedesco A. C. Primo F. L. (2020). Anthraquinone encapsulation into polymeric nanocapsules as a new drug from biotechnological origin designed for photodynamic therapy. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther.31, 101815. 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.101815

2

Ballinger K. (2015). Use of quinone compound in building materials. WO2015116668A1.

3

Bao J. Sun Y. L. Zhang X. Y. Han Z. Gao H. C. He F. et al (2013). Antifouling and antibacterial polyketides from marine gorgonian coral-associated fungus Penicillium sp. SCSGAF 0023. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo).66, 219–223. 10.1038/ja.2012.110

4

Caro Y. Anamale L. Fouillaud M. Laurent P. Petit T. Dufosse L. (2012). Natural hydroxyanthraquinoid pigments as potent food grade colorants: An overview. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect.2, 174–193. 10.1007/s13659-012-0086-0

5

Chen X. Schauder S. Potier N. Van Dorsselaer A. Pelczer I. Bassler B. L. et al (2002). Structural identification of a bacterial quorum-sensing signal containing boron. Nature415, 545–549. 10.1038/415545a

6

Chien S-C. Wu Y-C. Chen Z-W. Yang W-C. (2015). Naturally occurring anthraquinones: Chemistry and therapeutic potential in autoimmune diabetes. Evidence-Based Complementary Altern. Med.2015, 357357. 10.1155/2015/357357

7

Dahms H. U. Dobretsov S. (2017). Antifouling compounds from marine macroalgae. Mar. Drugs15, 265. 10.3390/md15090265

8

Demselben (1840). Ueber verschiedene Verbindungen des Anthracen’s. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem.34, 287–296. 10.1002/jlac.18400340305

9

Dobretsov S. Rittschof D. (2022). Love at first taste: Induction of larval settlement by marine microbes. Int. J. Mol. Sci.2022, 731. 10.3390/ijms21030731

10

Dufossé L. (2014). Anthraquinones, the dr jekyll and mr hyde of the food pigment family. Food Res. Int.65, 132–136. 10.1016/j.foodres.2014.09.012

11

Edelsbrunner H. Liang J. Fu P. Facello M. (1995). "Measuring proteins and voids in proteins," in 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Hawaii, USA, 03-06 January 1995, pp. 256. 10.1109/HICSS.1995.375331

12

Forti J. C. Rocha R. S. Lanza M. R. V. Bertazzoli R. (2007). Electrochemical synthesis of hydrogen peroxide on oxygen-fed graphite/PTFE electrodes modified by 2-ethylanthraquinone. J. Electroanal. Chem. (Lausanne).601, 63–67. 10.1016/j.jelechem.2006.10.023

13

Fouillaud M. Venkatachalam M. Girard-Valenciennes E. Caro Y. Dufossé L. (2016). Anthraquinones and derivatives from marine-derived fungi: Structural diversity and selected biological activities. Mar. Drugs14, 64. 10.3390/md14040064

14

Furuta T. Hirayama Y. Iwamura M. (2001). Anthraquinon-2-ylmethoxycarbonyl (aqmoc): A new photochemically removable protecting group for alcohols. Org. Lett.3, 1809–1812. 10.1021/ol015787s

15

Gaspar D-M. Miranda I. L. Sartori S. K. de Rezende D. C. Nogueira Diaz M. A. (2018). “Chapter 11: Anthraquinones - an overview,” in Studies in natural products Chemistry. Editor RahmanA-U. (Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier), 58, 313–338. 10.1016/B978-0-444-64056-7.00011-8

16

Gomez-Banderas J. (2022). Marine natural products: A promising source of environmentally friendly antifouling agents for the maritime industries. Front. Mar. Sci.9, 858757. 10.3389/fmars.2022.858757

17

Graebe C. (1890). Ueber Bildung von Chinalizarin aus Alizarin. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges.23, 3739–3740. 10.1002/cber.189002302361

18

Hanssen K. O. Cervin G. Trepos R. Petitbois J. Haug T. Hansen E. et al (2014). The bromotyrosine derivative ianthelline isolated from the arctic marine sponge Stryphnus fortis inhibits marine micro- and macrobiofouling. Mar. Biotechnol. (NY).16, 684–694. 10.1007/s10126-014-9583-y

19

Henke J. M. Bassler B. L. (2004). Three parallel quorum-sensing systems regulate gene expression in Vibrio harveyi. J. Bacteriol.186, 6902–6914. 10.1128/JB.186.20.6902-6914.2004

20

Huang Q. Lu G. Shen H-M. Maxey C. Chung M. Ong C. N. (2007). Anti-cancer properties of anthraquinones from rhubarb. Med. Res. Rev.27, 609–630. 10.1002/med.20094

21

Jackson T. C. Verrier J. D. Kochanek P. M. (2013). Anthraquinone-2-sulfonic acid (Aq2s) is a novel neurotherapeutic agent. Cell Death Dis.4, e451–e51. 10.1038/cddis.2012.187

22

Kalidhar S. B. (1989). Structural elucidation in anthraquinones using 1H NMR glycosylation and alkylation shifts. Phytochemistry28, 3459–3463. 10.1016/0031-9422(89)80364-4

23

Kshirsagar A. D. Panchal P. V. Harle U. N. Nanda R. K. Shaikh H. M. (2014). Anti-inflammatory and antiarthritic activity of anthraquinone derivatives in rodents. Int. J. Inflam.2014, 690596. 10.1155/2014/690596

24

Laskowski R. A. Swindells M. B. (2011). LigPlot+: Multiple ligand-protein interaction diagrams for drug discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model.51, 2778–2786. 10.1021/ci200227u

25

Li Y. Ning C. (2019). Latest research progress of marine microbiological corrosion and bio-fouling, and new approaches of marine anti-corrosion and anti-fouling. Bioact. Mat.4, 189–195. 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2019.04.003

26

Liu L. L. Wu C. H. Qian P. Y. (2020). Marine natural products as antifouling molecules - a mini-review (2014-2020). Biofouling36, 1210–1226. 10.1080/08927014.2020.1864343

27

Locatelli M. (2011). Anthraquinones: Analytical techniques as a novel tool to investigate on the triggering of biological targets. Curr. Drug Targets12, 366–380. 10.2174/138945011794815338

28

Malik E. M. Baqi Y. Müller C. E. (2015). Syntheses of 2-substituted 1-amino-4-bromoanthraquinones (bromaminic acid analogues) - precursors for dyes and drugs. Beilstein J. Org. Chem.11, 2326–2333. 10.3762/bjoc.11.253

29

Malik E. M. Müller C. E. (2016). Anthraquinones as pharmacological tools and drugs. Med. Res. Rev.36, 705–748. 10.1002/med.21391

30

Malik M. S. Alsantali R. I. Jassas R. S. Alsimaree A. A. Syed R. Alsharif M. A. et al (2021). Journey of anthraquinones as anticancer agents - a systematic review of recent literature. RSC Adv.57, 35806–35827. 10.1039/d1ra05686g

31

Malmir M. Serrano R. Silva O. (2017). “Anthraquinones as potential antimicrobial agents - a review,” in Antimicrobial research: Novel bioknowledge and educational programs. Editor Mendez-VilasA. (Badajoz, Spain: Formatex Research Center S.L.), 55–61.

32

Miller M. B. Bassler. B. L. (2001). Quorum sensing in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol.55, 165–199. 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.165

33

Molecular Operating Environment (MOE), (2022.02).Chemical computing group ULC, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2022.

34

Molnar J. L. Gamboa R. L. Revenga C. Spalding M. D. (2008). Assessing the global threat of invasive species to marine biodiversity. Front. Ecol. Environ.6, 485–492. 10.1890/070064

35

Ortlepp S. Sjögren M. Dahlström M. Weber H. Ebel R. Edrada R. et al (2007). Antifouling activity of bromotyrosine-derived sponge metabolites and synthetic analogues. Mar. Biotechnol. (NY).9, 776–785. 10.1007/s10126-007-9029-x

36

Osman C. P. Ismail N. H. (2018). Antiplasmodial anthraquinones from medicinal plants: The chemistry and possible mode of actions. Nat. Prod. Commun.13, 1934578X1801301. 10.1177/1934578X1801301207

37

Patnaik S. Swami A. Sethi D. Pathak A. Garg B. S. Gupta K. C. et al (2007). N-(Iodoacetyl)-N'-(anthraquinon-2-oyl)-ethylenediamine (iaed): A new heterobifunctional reagent for the preparation of biochips. Bioconjug. Chem.18, 8–12. 10.1021/bc0602634

38

Pettersen E. F. Goddard T. D. Huang C. C. Couch G. S. Greenblatt D. M. Meng E. C. et al (2004). UCSF Chimera- a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem.25, 1605–1612. 10.1002/jcc.20084

39

Piazza V. Roussis V. Garaventa F. Greco G. Smyrniotopoulos V. Vagias C. et al (2011). Terpenes from the red alga Sphaerococcus coronopifolius inhibit the settlement of barnacles. Mar. Biotechnol. (NY).13, 764–772. 10.1007/s10126-010-9337-4

40

Rajamanikandan S. Jeyakanthan J. Srinivasan P. (2017). Molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, computational screening to design quorum sensing inhibitors targeting LuxP of Vibrio harveyi and its biological evaluation. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol.181, 192–218. 10.1007/s12010-016-2207-4

41

Sander T. Freyss J. von Korff M. Rufener C. (2015). DataWarrior: An open-source program for chemistry aware data visualization and analysis. J. Chem. Inf. Model.55, 460–473. 10.1021/ci500588j

42

Schultz M. P. Bendick J. A. Holm E. R. Hertel W. M. (2011). Economic impact of biofouling on a naval surface ship. Biofouling27, 87–98. 10.1080/08927014.2010.542809

43

Seo E. J. Ngoc T. M. Lee S-M. Kim Y. S. Jung Y-S. (2012). Chrysophanol-8O-glucoside, an anthraquinone derivative in rhubarb, has antiplatelet and anticoagulant activities. J. Pharmacol. Sci.118, 245–254. 10.1254/jphs.11123FP

44

Shanghai Min Xuan Steel Structure Work Co Ltd (2022). Antifouling anticorrosion coating for surfaces of steel structures. CN104592861A.

45

Shaw D. W. (2009). Allergic contact dermatitis from carmine. Dermatitis20, 292–295. 10.2310/6620.2009.09025

46

Srinivas G. Babykutty S. Sathiadevan P. P. Srinivas P. (2007). Molecular mechanism of emodin action: Transition from laxative ingredient to an antitumor agent. Med. Res. Rev.27, 591–608. 10.1002/med.20095

47

Stompor-Gorący M. (2021). The health benefits of emodin, a natural anthraquinone derived from rhubarb—A summary update. Int. J. Mol. Sci.22, 9522. 10.3390/ijms22179522

48

Test Field of China Shipbuilding Industry Corp (2020). Equipment and method for long-acting environment-friendly inhibition of marine organism adhesion of underwater structure. CN111074871A.

49

Tian W. Wang C. Li D. Hou H. (2020). Novel anthraquinone compounds as anticancer agents and their potential mechanism. Future Med. Chem.12, 627–644. 10.4155/fmc-2019-0322

50

Tintillier F. Moriou C. Petek S. Fauchon M. Hellio C. Saulnier D. et al (2020). Quorum sensing inhibitory and antifouling activities of new bromotyrosine metabolites from the Polynesian sponge Pseudoceratina n. sp. Mar. Drugs18, 272. 10.3390/md18050272

51

Trott O. Olson A. J. (2010). AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem.31, 455–461. 10.1002/jcc.21334

52

Uchimiya M. Stone A. T. (2009). Reversible redox chemistry of quinones: Impact on biogeochemical cycles. Chemosphere77, 451–458. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.07.025

53

Umezawa T. Oguri Y. Matsuura H. Yamazaki S. Suzuki M. Yoshimura E. et al (2014). Omaezallene from red alga Laurencia sp.: Structure elucidation, total synthesis, and antifouling activity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.53, 3909–3912. 10.1002/anie.201311175

54

Wolber G. Langer T. (2005). LigandScout: 3-D pharmacophores derived from protein-bound ligands and their use as virtual screening filters. J. Chem. Inf. Model.45, 160–169. 10.1021/ci049885e

55

Wu C.-M. Wu S.-C. Chung W.-J. Lin H.-C. Chen K.-T. Chen Y.-C. et al (2007). Antiplatelet effect and selective binding to cyclooxygenase (COX) by molecular docking analysis of flavonoids and lignans. Int. J. Mol. Sci.8, 830–841. 10.3390/i8080830

56

Wuthi-udomlert M. Kupittayanant P. Gritsanapan W. (2018). In vitro evaluation of antifungal activity of anthraquinone derivatives of Senna alata”. J. Health Res.24, 117–122. Available at: https://he01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/jhealthres/article/view/156816.

57

Xu Y. He H. Schulz S. Liu X. Fusetani N. Xiong H. et al (2010). Potent antifouling compounds produced by marine Streptomyces. Bioresour. Technol.101, 1331–1336. 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.09.046

Summary

Keywords

anthraquinones, biofouling, antifouling (AF), molecular docking, pharmacophore, structure-activity relationship (SAR), citreorosein, emodin

Citation

Preet G, Gomez-Banderas J, Ebel R and Jaspars M (2022) A structure-activity relationship analysis of anthraquinones with antifouling activity against marine biofilm-forming bacteria. Front. Nat. Prod. 1:990822. doi: 10.3389/fntpr.2022.990822

Received

10 July 2022

Accepted

26 September 2022

Published

18 October 2022

Volume

1 - 2022

Edited by

Sherif S. Ebada, Ain Shams University, Egypt

Reviewed by

Ritesh Raju, Western Sydney University, Australia

Weaam Ebrahim, Mansoura University, Egypt

Iqbal Kabir Jahid, Jashore University of Science and Technology, Bangladesh

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Preet, Gomez-Banderas, Ebel and Jaspars.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marcel Jaspars, m.jaspars@abdn.ac.uk

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

This article was submitted to Isolation and Purification, a section of the journal Frontiers in Natural Products

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.