- 1School of Data Science, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, United States

- 2Institute for Clinical and Translational Science, University of California, Irvine, CA, United States

- 3Department of Pediatrics, Pediatric Exercise and Genomics Research Center, University of California, Irvine, CA, United States

This research analyzed the sample entropy (SampEn) of breath-by-breath cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) data from 170 healthy pediatric participants (85 males) 8 to 18-years-old, using a Bayesian statistics approach. SampEn measures the complexity of time series data, providing quantitative insight into the predictability of breathing patterns in pediatric participants. To address non-stationarity, signals were differenced prior to SampEn calculation. In addition to sex and age group comparisons, we examined SampEn before and after the midpoint of each participant’s CPET to assess how SampEn changes as exercise intensity increases. We corroborated previous findings that SampEn decreases in the later half of CPET for healthy pediatric participants for oxygen uptake

1 Introduction

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) is a non-invasive clinical tool with the ability to provide wide-ranging insights into human health for clinical applications (Myers et al., 2014; West et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2022; Cooper et al., 2023). During a progressive CPET, the intensity of exercise increases incrementally, typically on a treadmill or cycle ergometer, while physiological metrics such as heart rate

Despite the richness of these continuous breath-by-breath data, clinical practice generally refers to maximal, submaximal, or aggregated metrics (Leclerc, 2017; Kristenson et al., 2024). In particular, CPET in clinical practice has traditionally focused on

Some research has begun exploring methodologies to take advantage of the entire breath-by-breath data set from CPET (Cooper et al., 2014; Ntalianis et al., 2024; Ross et al., 2024). One promising approach involves the value of information science analytics such as entropy, a statistical measure that can quantify the complexity or unpredictability within time-series data. Entropy provides insights distinct from variability; for example, a highly variable but predictable signal (e.g., a sine wave) demonstrates low entropy. Entropy analysis may be especially informative in pediatric CPET as younger participants' breathing patterns tend to be more irregular than those of adults (Nagano et al., 1998; Ondrak and McMurray, 2006). This increased irregularity in breath timing and volume can produce greater fluctuations in the underlying time-series signal, enhancing the usefulness of entropy to detect differences in physiological control and adaptation during exercise.

Previous research (Blanks et al., 2024a; Blanks et al., 2024b) applied entropy analysis to pediatric populations, finding significant insights related to pubertal status and sex differences in CPET metrics. However, analyzing entropy of CPET variables presents unique challenges due to the short duration and non-stationary nature of the ramp CPET protocols where work rate and physiological signal responses change continuously without reaching a steady state. Non-stationarity violates assumptions of constant mean, variance, and autocorrelation, complicating entropy analysis. The method introduced in Blanks and Brown (2024) effectively addresses this by incorporating techniques to handle these non-stationary signals.

Building on this work, and continuing the process of validation of these new CPET analytics in the context of the growing child, the present study applies the entropy-based methodology used by Blanks et al. (2024b) to a larger pediatric data set (170 participants in this study vs. 81 in the previous study) with some key differences. For instance, the previous study separated the data at the ventilatory threshold

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Data description

2.1.1 CPET

Children and adolescents were recruited for this study, which was approved by the University of California, Irvine Institutional Review Board. All procedures adhered to relevant ethical guidelines and regulations. Demographic and anthropometric measurements were collected using a calibrated scale and stadiometers. Participants then performed a CPET following an established ramp progressive protocol in the laboratory by pedaling on an electronically braked, servo-controlled cycle ergometer (Lode, Groningen, Netherlands) (Cooper et al., 2014). During testing, the Sensor Medics System (Vmax Encore 229, Yorba Linda, CA) collected gas exchange data and at each breath instantaneous

2.1.2 Pediatric participant demographics and sample characteristics

This study included 170 participants aged 8–18 years (85 males) with no known cardiac, metabolic, or respiratory conditions and no history of taking medication for chronic disorders. The body mass index (BMI) of all participants fell between the 5.34% and 84.16% percentiles. [These BMI percentile values are sex-age specific, calculated utilizing CDC growth charts (Kuczmarski et al., 2002)]. The time series of breaths recorded during CPET for the 170 participants had a mean of

where

Similarly, we defined the moving standard deviation at observation

Finally, we considered

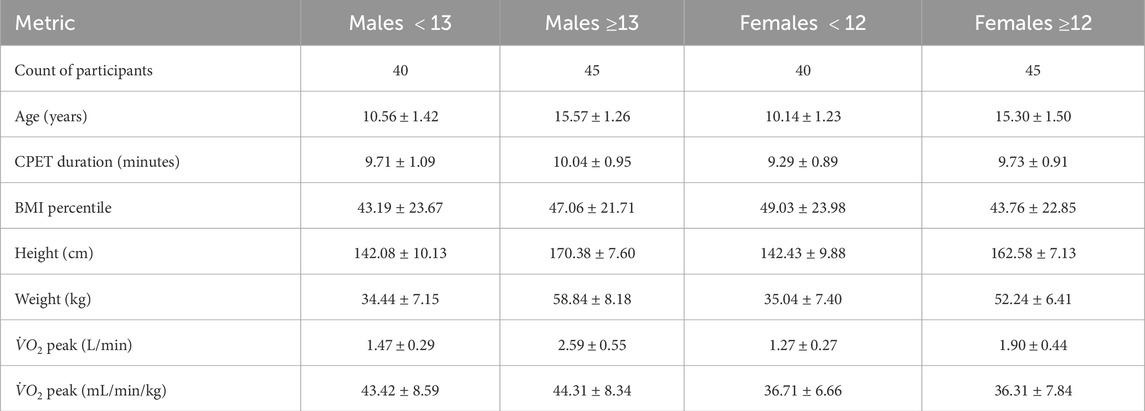

After the mentioned data cleaning techniques, participants with missing breath-by-breath data for 30 consecutive seconds or more for any metric were excluded from this study. More participant information can be found in Table 1, where

To examine the effects of age and sex on Sample Entropy (SampEn), participants were first divided by sex into male and female groups. Within each sex, males were classified as younger than 13 years or older than 13 years, and females as younger than 12 years or older than 12 years. These cutoffs approximate the typical ages at which each sex reaches Tanner Stage 3 of 5 (Brix et al., 2019). Since this is an imperfect estimation, we also conducted additional analyses using an alternative female group cutoff at age 11 instead of 12 and excluding the 8 male participants between 12.5 (inclusive) and 13.5 years old (exclusive) and the 12 female participants between 11 (inclusive) and 12 (exclusive). The former provides some sensitivity analysis for the age delineator for female participants, and the latter creates more distinct age groups for both males and females. Minimal differences in results were observed between the groups. The results for these additional grouping mechanisms can be found in the Supplementary Data section. Since we created groups based off age, all results are interpreted as related to the age of the participants, and not to their maturational status.

2.2 Sample entropy and stationarity

The participants included in this study had a mean of

SampEn measures the uncertainty and predictability of dynamic time series data (Richman and Moorman, 2000). Let

where

where

To compute the probability that the time series data remain within a distance

Finally, SampEn can be calculated using Equation 8.

Richman and Moorman (2000) provides details of the mathematical foundations of SampEn. Chatain et al. (2020) discusses that it is vital to work with stationary signals for accurate SampEn analysis. To account for CPET signals being non-stationary, we modified the signals into a weakly stationary form by applying a differencing algorithm. In particular, if

where

2.3 SampEn Pre- and post- midpoint

Blanks et al. (2024b) also studied the SampEn of each participant before and after they reached their

2.4 Bayesian statistical testing

To analyze differences in the entropy of the gas exchange and

•

•

•

•

•

•

The following specifications were placed on the model:

•

•

• •

•

•

•

•

These prior distributions and parameter decisions are the same as those in Blanks et al. (2024b) for effective comparison of SampEn results. Specifically, the Gaussian prior for

We utilized PyMC Abril-Pla et al. (2023) for Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling via the No U-Turn Sampler algorithm. For each sample, 4000 posterior draws were made from MCMC. We evaluated convergence using trace plots, effective sample size, and the

2.4.1 Midpoint entropy differences

To compare SampEn pre- and post-midpoint, we defined

The estimated probability that

based on

2.4.2 Total entropy analysis: effect of age on SampEn

In this section, we examined the entropy differences across the age groups for the entire CPET, regardless of the midpoint. We evaluated the following mean posterior SampEn percentage difference between the older participants and the younger participants in Equation 12.

where

The estimated probability that

based on

2.4.3 Total entropy analysis: effect of sex on SampEn

As a part of this study, we also explored the entropy differences between males and females for the entire CPET, regardless of the midpoint. For each CPET metric

where

The estimated probability that

based on

3 Results

3.1 Midpoint entropy differences

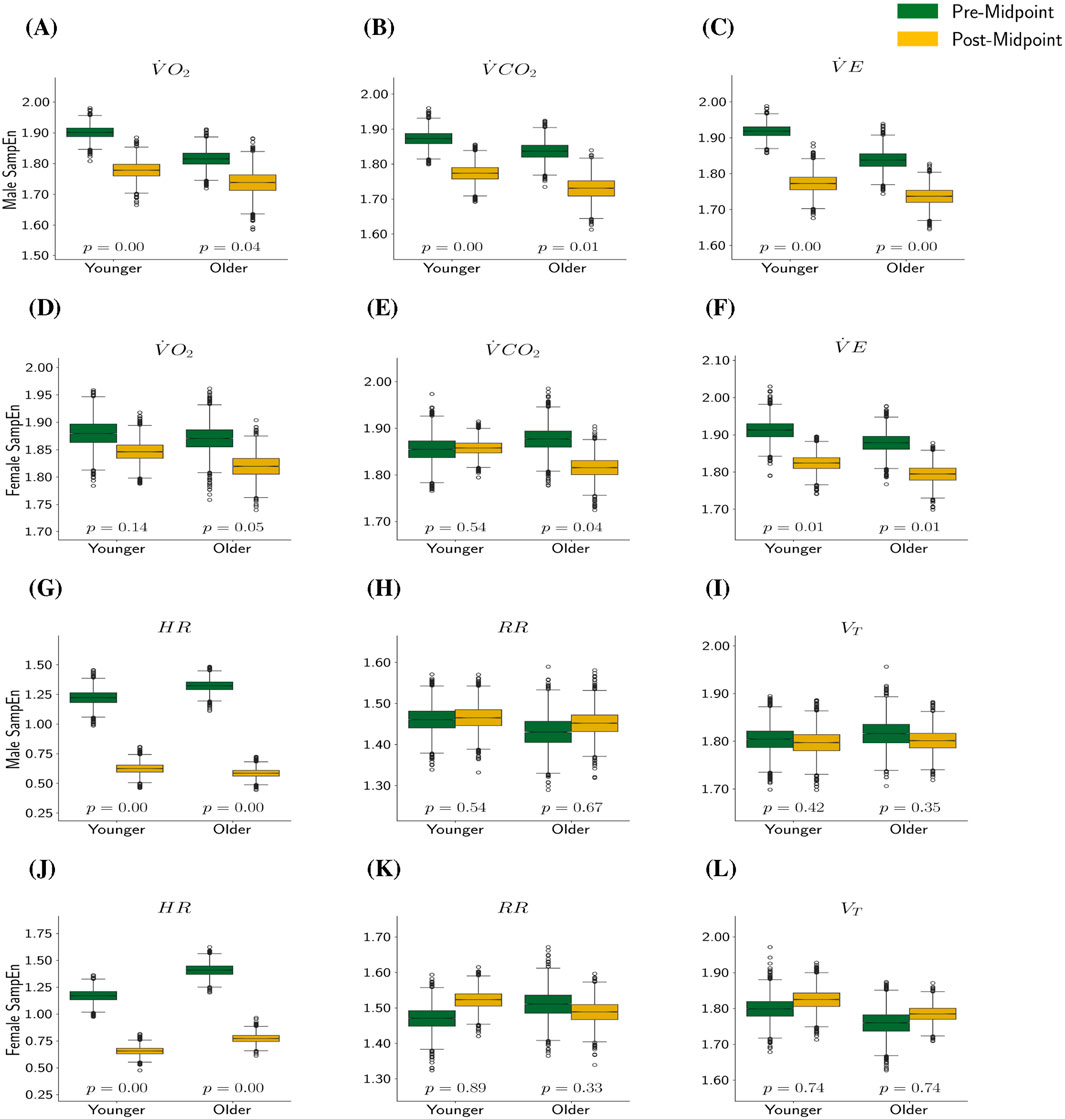

Similar to the post

• For all four combinations of age and sex, (except for younger females’

• The differences between

Figure 1. SampEn Pre- and Post-Midpoint by Metric, Sex, and Age. In this plot,

3.2 Total entropy analysis

In this section, we examine the differences in entropy between sexes and age groups for the entire CPET, regardless of the midpoint.

3.2.1 Effect of age on SampEn

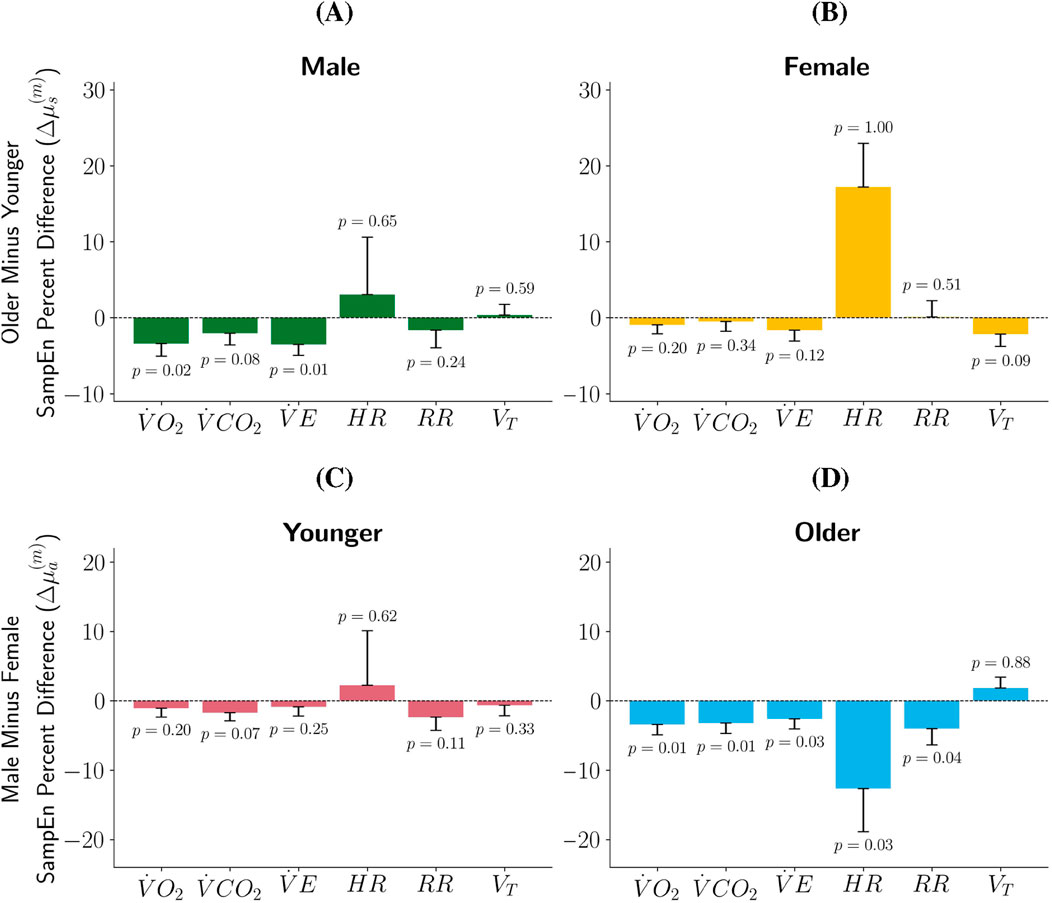

Results and analysis detailed in Blanks et al. (2024a) and Blanks et al. (2024b) both suggest that early-pubertal participants tend to have higher SampEn than late-pubertal participants, particularly female participants. Thus, we hypothesized that the younger participants would have higher SampEn than the older participants in our sample. Recall that if

• Younger male participants have higher SampEn than older male participants with statistical significance for

• Older male participants have higher SampEn than younger male participants for

• Younger female participants have a higher SampEn than older female participants without statistical significance for metrics

• Older female participants have a higher SampEn than younger female participants for

Figure 2. Percent Difference in SampEn by Sex and Age Group. In plots (A,B)

3.2.2 Effect of sex on SampEn

Blanks et al. (2024a) and Blanks et al. (2024b) found that pediatric female participants tend to exhibit greater SampEn of CPET metrics than pediatric male participants. We aimed to determine if this claims extends to the participants in this study. Results shown in Figures 2C,D indicate:

• For the younger participants, females have a higher SampEn for

• Younger male participants have higher SampEn for

• Older females have statistically significant higher SampEn than their male counterparts for

• Older males have higher SampEn than their female counterparts for

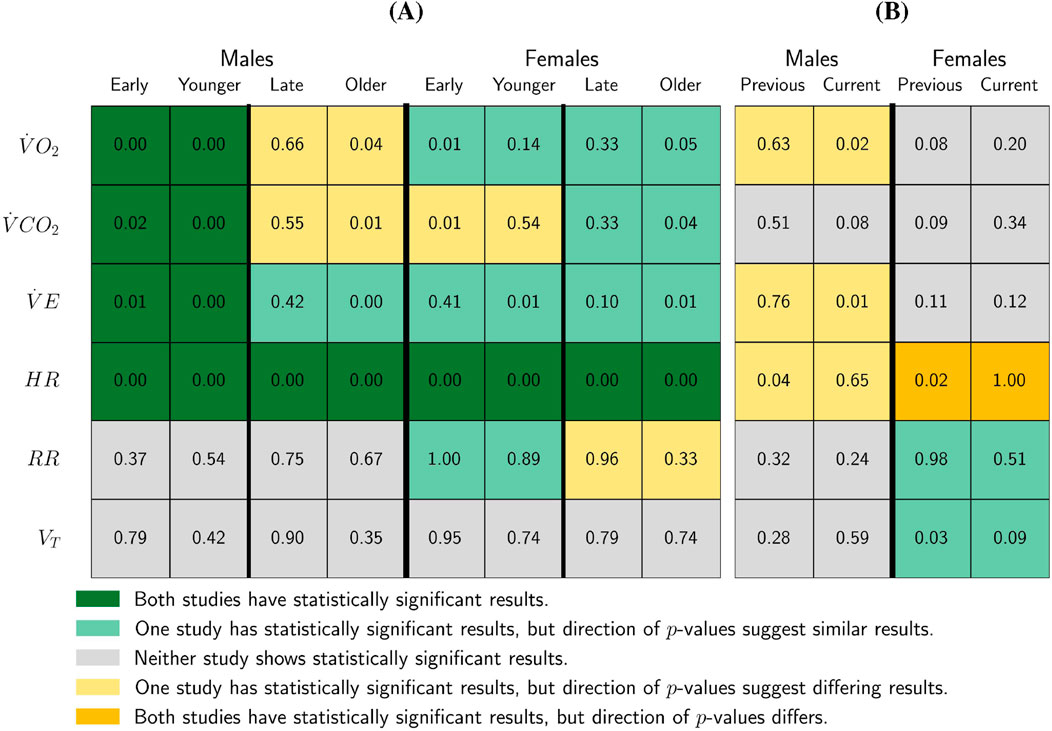

3.3 Comparison to previous study

We compared these results to those reported in Blanks et al. (2024b) (Figure 3). In that study, participants were grouped by pubertal status, while in this study, we used age. For direct comparison, we aligned Blanks et al. (2024b) early pubertal participants with the younger participants in this study, and the late pubertal participants with our older participants. Note that the same statistical procedures and significance thresholds were used in both studies.

Figure 3. Study Comparison of SampEn Pre-/Post-

Key points from Figure 3 include:

• Consistent findings across studies: Both studies find statistically significant decreases in SampEn post-

Differences in statistical significance: Although the direction of results was generally consistent, statistical significance varied. Only one study presented statistically significant results for:

• A decline in SampEn of

• A decline in SampEn of

• A decline in SampEn for

• Male adolescent differences: The present study finds a statistically significant decline in SampEn post-midpoint for older male participants, whereas Blanks et al. (2024b) observed a non-significant increase in

• Younger female

• Older female

Figure 3 also compares the

• Both the present study and Blanks et al. (2024b) younger female participants (early-puberty) to have higher SampEn than their older (late-puberty) counterparts for the

• Both studies found older female participants (late-puberty) to have higher SampEn than younger female participants (early-puberty) for the

• For males, the current study found the younger participants to have higher SampEn than the older participants for

• Blanks et al. (2024b) found younger male participants (early-puberty) to have statistically significantly higher SampEn than their older male (late-puberty) counterparts for the

• The current work found older female participants to have higher

4 Discussion

This study strengthens the findings of Blanks et al. (2024b) regarding how SampEn changes as exercise intensity increases during CPET. Specifically, SampEn consistently decreases for

The consistent decreases in SampEn for

In this study, females had higher SampEn than males in both age groups for

One limitation of this work relates specifically to the

As a part of this experiment, the SampEn of the differenced signal was calculated to produce a weakly stationary form. This step is necessary as Chatain et al. (2020) found that failing to account for the non-stationarity of physiological force signals increases SampEn. Differencing the signal emphasizes short-term fluctuations versus the gradually increasing trend of CPET metrics over time.

We also chose to group participants by age rather than pubertal status. This decision was intentional, as age is an objective and easily collected measure, whereas pubertal status is more difficult to obtain (Ernst et al., 2018; Ebo et al., 2024). While age may not perfectly align with maturational status, our sensitivity analyses using alternative age cutoffs and excluding participants near the thresholds produced minimal differences in results. This supports the suitability of age as a practical proxy in this context, while acknowledging that maturational status can provide additional developmental insight.

Finally, we segmented the CPET at the midpoint rather than

The stark disagreement between this study and (Blanks et al., 2024b) for the female age and pubertal status groups’

In conclusion, this study builds on the work of Blanks et al. (2024b) by applying entropy-based analysis to a larger pediatric CPET cohort. We confirmed consistent post-midpoint declines in

Data availability statement

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because human subjects’ data is protected beyond the research team. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to Shlomit Radom Aizik, c2FpemlrQGhzLnVjaS5lZHU=.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the University of California, Irvine Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the minor(s)' legal guardian/next of kin for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

KO: Investigation, Writing – review and editing, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Visualization. DB: Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing. DC: Writing – review and editing, Conceptualization, Formal Analysis. AS: Data curation, Writing – review and editing, Validation. SR: Data curation, Writing – review and editing, Formal Analysis. NK: Formal Analysis, Writing – review and editing, Project administration, Visualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants: 1) Project REACH (Revamping Exercise Assessments in Child Health) National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) U01 TR002004, 2) the UCI Clinical Translational Science Award (CTSA) NCATS UCI TR004927.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI was used to debug code to create plots using matplotlib in own python environment.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2025.1698399/full#supplementary-material

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE S1 | SampEn Pre- and Post-Midpoint by Metric, Sex, and Age - Female Age Cut Off of 11 Years. In this plot,

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE S2 | SampEn Pre- and Post-Midpoint by Metric, Sex, and Age - Remove Middle Aged Male and Female Participants. In this plot,

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE S3 | Percent Difference in SampEn by Sex and Age Group - Female Age Cut Off of 11 Years. In plots (A,B)

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE S4 | Percent Difference in SampEn by Sex and Age Group - Remove Middle Aged Male and Female Participants. In plots (A,B)

References

Abril-Pla O., Andreani V., Carroll C., Dong L., Fonnesbeck C. J., Kochurov M., et al. (2023). PyMC: a modern, and comprehensive probabilistic programming framework in python. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 9, e1516. doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.1516

Bassett D. R. (2002). Scientific contributions of A. V. Hill: exercise physiology pioneer. J. Appl. Physiology 93, 1567–1582. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.01246.2001

Blanks Z., Brown D. E. (2024). Bayesian optimization of sample entropy hyperparameters for short time series. doi:10.48550/ARXIV.2405.06112

Blanks Z., Brown D. E., Cooper D. M., Aizik S. R., Bar-Yoseph R. (2024a). Signal variability comparative analysis of healthy Early- and late-pubertal children during cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Med. and Sci. Sports and Exerc. 56, 287–296. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000003296

Blanks Z., Brown D. E., Cooper D. M., Aizik S. R., Bar-Yoseph R. (2024b). Dynamics of gas exchange and heart rate signal entropy in standard cardiopulmonary exercise testing during critical periods of growth and development. Physiol. Rep. 12, e70034. doi:10.14814/phy2.70034

Brix N., Ernst A., Lauridsen L. L. B., Parner E., Støvring H., Olsen J., et al. (2019). Timing of puberty in boys and girls: a population-based study. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 33, 70–78. doi:10.1111/ppe.12507

Chatain C., Gruet M., Vallier J.-M., Ramdani S. (2020). Effects of nonstationarity on muscle force signals regularity during a fatiguing motor task. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabilitation Eng. 28, 228–237. doi:10.1109/TNSRE.2019.2955808

Cooper D. M., Radom-Aizik S., Schwindt C., Zaldivar F. (2007). Dangerous exercise: lessons learned from dysregulated inflammatory responses to physical activity. J. Appl. Physiology 103, 700–709. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00225.2007

Cooper D. M., Leu S.-Y., Galassetti P., Radom-Aizik S. (2014). Dynamic interactions of gas exchange, body mass, and progressive exercise in children. Med. and Sci. Sports and Exerc. 46, 877–886. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000000180

Cooper D., Bar-Yoseph B., Olin T., Lovinsky S., Radom-Aizik S. (2023). “Exercise and lung function in child health and disease,” in Kendig and Wilmott’s disorders of the respiratory tract in children. Editors E. L. Kendig, and R. W. Wilmott 10th edition edn. (Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier), 182–200.

Dominelli P. B., Molgat-Seon Y. (2022). Sex, gender and the pulmonary physiology of exercise. Eur. Respir. Rev. 31, 210074. doi:10.1183/16000617.0074-2021

Ebo C., McCray J., Bowers K., Rose S. R., Jones N.-H. Y. (2024). Self-puberty staging in endocrine encounters during the COVID pandemic. Front. Endocrinol. 15, 1487329. doi:10.3389/fendo.2024.1487329

Ernst A., Lauridsen L. L. B., Brix N., Kjersgaard C., Olsen J., Parner E. T., et al. (2018). Self-assessment of pubertal development in a puberty cohort. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metabolism 31, 763–772. doi:10.1515/jpem-2018-0178

Fukumoto Y., Tsuji Y., Kakuda A., Hori R., Kitano M., Sakamoto K., et al. (2022). Evaluation of autonomic nervous system responses during isometric handgrip exercise using nonlinear analysis of heart rate variability. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 34, 689–693. doi:10.1589/jpts.34.689

Grassmann M., Vlemincx E., Von Leupoldt A., Mittelstädt J. M., Van Den Bergh O. (2016). Respiratory changes in response to cognitive load: a systematic review. Neural Plast. 2016, 8146809–8146816. doi:10.1155/2016/8146809

Hesse A., White M., Lundstrom C. (2025). The prevalence of gas exchange data processing methods: a semi-automated scoping review. Int. J. Sports Med. 46, 227–236. doi:10.1055/a-2495-5364

Jiang Y., Costello J. T., Williams T. B., Panyapiean N., Bhogal A. S., Tipton M. J., et al. (2021). A network physiology approach to oxygen saturation variability during normobaric hypoxia. Exp. Physiol. 106, 151–159. doi:10.1113/EP088755

Kim K. J., Rivas E., Prejean B., Frisco D., Young M., Downs M. (2021). Novel computerized method for automated determination of ventilatory threshold and respiratory compensation point. Front. Physiology 12, 782167. doi:10.3389/fphys.2021.782167

Kristenson K., Gerring E., Björnsson B., Sandström P., Hedman K. (2024). Peak oxygen uptake in combination with ventilatory efficiency improve risk stratification in major abdominal surgery. Physiol. Rep. 12, e15904. doi:10.14814/phy2.15904

Kuczmarski R. J., Ogden C. L., Guo S. S., Grummer-Strawn L. M., Flegal K. M., Mei Z. (2002). 2000 CDC growth charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital Health Stat. 246, 1–190.

Leclerc K. (2017). Cardiopulmonary exercise testing: a contemporary and versatile clinical tool. Clevel. Clin. J. Med. 84, 161–168. doi:10.3949/ccjm.84a.15013

Myers J., De Souza C. R., Borghi-Silva A., Guazzi M., Chase P., Bensimhon D., et al. (2014). A neural network approach to predicting outcomes in heart failure using cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Int. J. Cardiol. 171, 265–269. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.12.031

Nagano Y., Baba R., Kuraishi K., Yasuda T., Ikoma M., Nishibata K., et al. (1998). Ventilatory control during exercise in normal children. Pediatr. Res. 43, 704–707. doi:10.1203/00006450-199805000-00021

Ntalianis E., Cauwenberghs N., Sabovčik F., Santana E., Haddad F., Claes J., et al. (2024). Improving cardiovascular risk stratification through multivariate time-series analysis of cardiopulmonary exercise test data. iScience 27, 110792. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2024.110792

Ondrak K. S., McMurray R. G. (2006). Exercise-induced breathing patterns of youth are related to age and intensity. Eur. J. Appl. Physiology 98, 88–96. doi:10.1007/s00421-006-0248-z

Pincus S. M. (1994). Greater signal regularity May indicate increased system isolation. Math. Biosci. 122, 161–181. doi:10.1016/0025-5564(94)90056-6

Rasmussen A. R., Wohlfahrt-Veje C., Tefre De Renzy-Martin K., Hagen C. P., Tinggaard J., Mouritsen A., et al. (2015). Validity of self-assessment of pubertal maturation. Pediatrics 135, 86–93. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-0793

Richman J. S., Moorman J. R. (2000). Physiological time-series analysis using approximate entropy and sample entropy. Am. J. Physiology-Heart Circulatory Physiology 278, H2039–H2049. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.6.H2039

Ross H. J., Peikari M., Vishram-Nielsen J. K. K., Fan C.-P. S., Hearn J., Walker M., et al. (2024). Predicting heart failure outcomes by integrating breath-by-breath measurements from cardiopulmonary exercise testing and clinical data through a deep learning survival neural network. Eur. Heart J. - Digital Health 5, 324–334. doi:10.1093/ehjdh/ztae005

Rossiter H. B. (2021). The “Anaerobic Threshold” concept is valid in physiology and medicine. Med. and Sci. Sports and Exerc. 53, 1089–1092. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000002548

Smith K. N., Baynard T., Fischbach P. S., Hankins J. S., Hsu L. L., Murphy P. M., et al. (2022). Safety of maximal cardiopulmonary exercise testing in individuals with sickle cell disease: a systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 56, 764–769. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2021-104450

Solís-Montufar E. E., Gálvez-Coyt G., Muñoz-Diosdado A. (2020). Entropy analysis of RR-Time series from stress tests. Front. Physiology 11, 981. doi:10.3389/fphys.2020.00981

Tipton C. M. (1998). Contemporary exercise physiology: fifty years after the closure of harvard fatigue laboratory. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 26, 315–339.

Vehtari A., Gelman A., Simpson D., Carpenter B., Bürkner P.-C. (2021). Rank-normalization, folding, and localization: an improved Rˆ for assessing convergence of MCMC (with discussion). Bayesian Anal. 16. doi:10.1214/20-BA1221

Keywords: entropy, pediatrics, cardiopulmonary exercise testing, breath-by-breath, bayesian statistics

Citation: O’Hara K, Brown DE, Cooper DM, Stehli A, Radom Aizik S and Kupperman N (2025) Entropy as a marker of physiological transition during pediatric cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Front. Physiol. 16:1698399. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2025.1698399

Received: 03 September 2025; Accepted: 28 October 2025;

Published: 01 December 2025.

Edited by:

Giuseppe D’Antona, University of Pavia, ItalyReviewed by:

Soheil Keshmiri, Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University, JapanAlireza Mani, University College London, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2025 O’Hara, Brown, Cooper, Stehli, Radom Aizik and Kupperman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kaleigh O’Hara, ZWFyM2NnQHZpcmdpbmlhLmVkdQ==

†These authors share senior authorship

Kaleigh O’Hara

Kaleigh O’Hara Donald E. Brown1

Donald E. Brown1 Dan M. Cooper

Dan M. Cooper Natalie Kupperman

Natalie Kupperman