- 1School of Human Evolution and Social Change, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, United States

- 2Department of Anthropology, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR, United States

With antecedents reaching back to the Olmec era (1500–600 BCE), complex societies from CE 300–900/1000 in the Gulf lowlands display architectural and material culture indications of both authoritarian and collective governance principles over two large areas, each with a distinctive version of a common architectural layout. The two areas include multiple polities adhering to particular layouts of structures providing key urban services. Our information derives from pedestrian surveys and mapping covering about 5,000 km2, plus remote sensing over 53,000 km2. Remote sensing reveals the extraordinary extent and consistency of the predominant architectural patterns. Starting with the Olmec era and continuing to CE 600 some sculpture glorifies individual rulers, but, at the same time, architecture shows the importance of corporate groups and public access to services that represent a more collective emphasis. Between CE 300 to 900, monumental platforms that supported palatial residences indicate powerful elites and rulers. Long mounds located on each side of the main plazas likely supported multiple rooms used by corporate civic groups. In some centers, multiple plaza groups attest to division of authority across several factions, as do chains of plazas in other cases. Thus, both authoritarian and collective principles are built into the design of urban centers. The replication of common architectural patterns across the study area suggests open networks of interaction consonant with low-density urbanism in the tropics. We concentrate our discussion of governance in south-central Veracruz during CE 300–900, for which we have more complete data, and we more briefly characterize the larger temporal and spatial framework. Eventually these urban networks collapsed due to a complex set of factors, but one ingredient may have been increasing disparities in wealth and corrosion of collective action.

Introduction

Since Wittfogel's (1957) publication of Oriental Despotism: A Comparative Study of Total Power, many ideas about ancient states formed a compelling contrast to modern democratic governments. Wittfogel's ideas about hydraulic management and powerful government resonated with a class system in the history of European monarchies. Neoevolutionists in anthropology recognized both authoritative (Service, 1971/1962:151–152, 1975:16) and exploitative (Fried, 1967; Carneiro, 1970) relationships that concentrated power in a few hands. Nevertheless, research on ancient states increasingly has shown organizational variety.

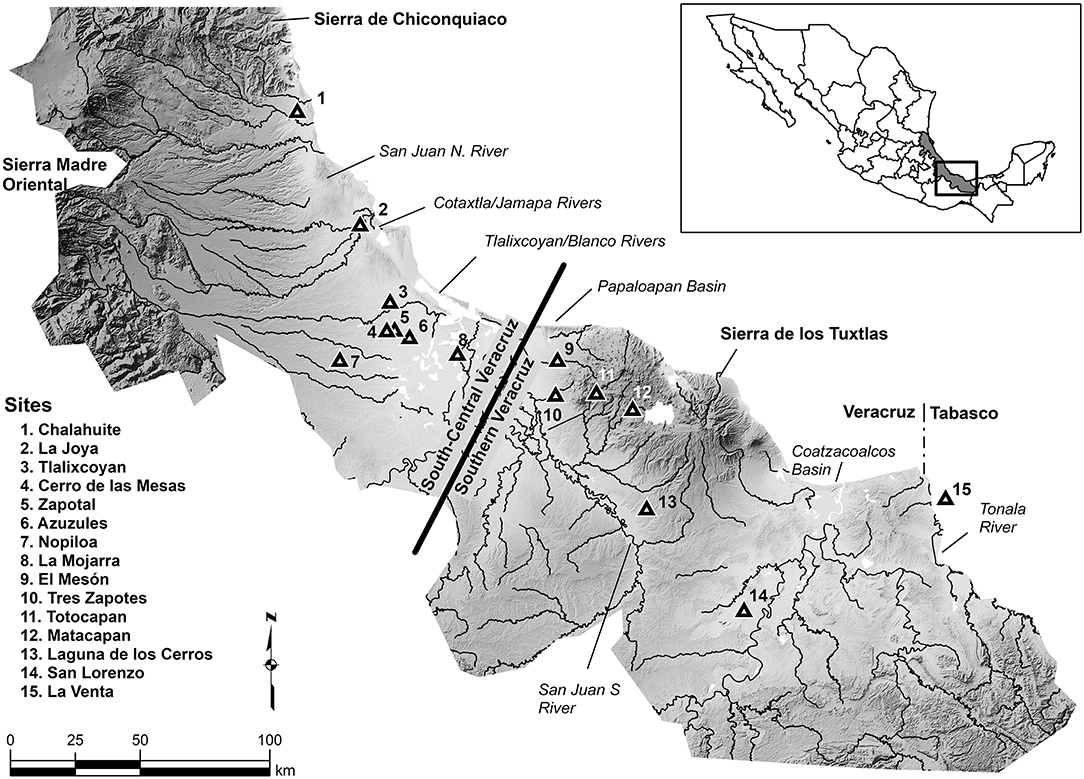

Initial cracks in the conceptual bias emphasizing rulers over the ruled came from the exploration of heterarchies instead of hierarchies (e.g., Ehrenreich et al., 1995) and factionalism (e.g., Brumfiel and Fox, 1994). Ideas about the coherence of states and their centralization of power were reexamined (e.g., Yoffee, 2005). An important thread in recent work is the recognition of variety in governance principles (or “strategies”). Another thread concerns tropical low-density urbanism. We bring these two recent subjects together in our Gulf lowland case study of mixed governance principles. We address the half of Veracruz south of the Sierra de Chiconquiaco (Figure 1), encompassing the south-central and southern areas traditionally separated by the Papaloapan River (Arnold and Pool, 2008:4). In the case study both autocratic and collective principles coexist and operate simultaneously in a widespread and relatively stable manner (see also Pool, 2010:100) and provide some points of contrast with low-density urbanism seen with the Classic Maya in Mesoamerica (e.g., Isendahl and Smith, 2013) and Khmer society in southeast Asia (e.g., Evans et al., 2007). There is more to ancient states than autocratic principles, which have been overrepresented in many traditional studies.

Figure 1. South-central and southern Veracruz, showing select physiographic features and archaeological sites.

Degrees of representation of the two principles are recognized in Blanton and Fargher's (2008) comparative scoring of historically documented states, but we assess archaeological traits related to governance in Gulf societies, rather than scoring numerous cases. Archaeological cases may vary considerably in available evidence, making large-scale comparisons difficult. We address whether both principles are represented as a mix and whether shifts occur in their prominence over time in purely archaeological contexts. Many criteria adapted to historic sources to evaluate pluralistic representation in governance and the provision of services to the general populace are not directly feasible for archaeological cases (Blanton et al., 2021).

We describe an extensive, long-lived record of mixed governance principles in part of the Gulf lowlands in Mesoamerica. There, the settlement record of low-density urbanism shows differences in governance compared to similar urban patterns in the Maya lowlands to the east, where there was an emphasis on authoritarian dynastic rule. Architecture and its arrangements, sculpture, tombs, and ritual activities in the Gulf lowlands form the primary data; inscriptions associated with leaders are few and do not provide the rich basis for decipherment that is the case for the Classic Maya. Gulf sculpture and labor mobilization point to authoritarian rulers, particularly during parts of the sequence. Collective principles in governance are attested by architectural layouts that include buildings likely associated with institutional or, more precisely, corporate groups, such as councils or lineages, and by other traits addressed below.

We briefly examine early and transitional periods (1500–600 BCE; 600 BCE-CE 300, respectively) as antecedents but concentrate on CE 300–900, particularly in south-central Veracruz, for which we have more data than southern Veracruz. The quantity of archaeological excavations in the Gulf area lags far behind many other regions of ancient complex society. Future research has a key role to play in confirmation or correction of our interpretations.

Background

Blanton and Fargher (2008) used a sample of historically documented states to argue for a range of emphases in governance depending on the primary source(s) of state revenue, drawing on ideas advanced by Levi (1988). They considered authoritarian and collective principles, scoring societies on several measures. Authoritarian principles involve a centralized government with autocratic powers, tending to rely on external revenues and/or valuable resources easily sequestered. The central government does not rely on the populace greatly for revenue. Little investment in infrastructure is one consequence, and local groups take care of a range of local affairs. Collective principles involve more participation by the general population in decision-making, whether through representative councils or assemblies. Internal revenues are important for the government, and, as a consequence, the populace has some leverage to demand more public goods or services from the state. In ancient states, corporate groups may play important roles in representing segments of the populace in collective governance rather than general enfranchisements seen in modern democracies. In an earlier treatment of Mesoamerican governance, Blanton et al. (1996) proposed analysis in terms of network vs. corporate governance principles, with oscillations in which one predominates over time. Autocratic leaders operate through patronage networks, but in corporate governance, a larger array of people is represented in decision-making through memberships in social, kin, and political groups.

With these two fresh looks at governance in premodern states, a greater political variety is evident than had been appreciated previously. In particular, collective action was not accommodated by schema in which ruling groups dominated the formation and maintenance of states. The latter are highlighted in neoevolutionary proposals for changes from egalitarian societies to chiefdoms (in some formulations) or to class-based societies (in others), and then to states (e.g., Fried, 1967; Service, 1975). We add to the understanding of ancient governance with Mesoamerican Gulf lowland societies that are particularly interesting for the longevity and scope of mixed principles in governance.

Scholars have begun to translate the principles of collective vs. authoritarian governance to archaeological contexts (e.g., Fargher et al., 2010, 2011; Carballo and Feinman, 2016; Feinman and Carballo, 2018; Stark, 2021). Many valuable measures used by Blanton and Fargher (2008) for historically documented cases do not translate well into archaeology and tend over-rely on information about the capitals of states and the upper classes. Archaeological data potentially compensate for information usually missing in historical documents. In our study, regionally-oriented systematic survey and mapping, as well as remote sensing, document varied sizes and ranks of settlements as well as patterns of civic architecture over time and across space. In another example that draws on architecture, Small (2009) uses accompanying inscriptions to assess corporate and networking avenues to power within a Greek city. This Greek case study contrasts with the Gulf regional scale we use, but, similar to our study, shows an eventual decrease in the strength of corporate institutions. In both cases, a focus on mixed principles and their changing contexts is strategic for perceiving governance dynamically.

Subjects that we examine include (1) sources of revenue for polities (whether internal or external), (2) accessibility of plaza groups with key urban services (whether open or restricted), (3) placement of palatial platforms (whether part of urban cores or somewhat removed), (4) the presence and prominence of corporate architecture (whether present in the civic core), (5) ritual offerings in residences and in public structures (if rituals are distinct or similar), (6) sculptural and ritual themes (leaders vs. general cosmological principles), (7) investment in funerary temples (if temples commemorate leaders), (8) if exchange was open or socially restricted (the presence of a market system), and (9) the degree of centralization of resources, public services, and authority (whether concentrated at primary centers or more widely distributed).

Indications of authoritarian principles include tendencies to a reliance on external or sequestered revenue, more restrictive access to central services, palaces proximal to major public buildings, lack of prominent corporate architecture in the civic core, contrasts in state rituals and popular practices, imagery favoring leaders, funerary temples, highly restricted markets or lack of any market system, and highly centralized resources, services, and authority. Collective tendencies in governance, in contrast, are indicated by internal revenue, open access to civic plazas, palaces not amalgamated with civic plazas, prominent corporate architecture in the civic core, commoner ritual practices also present in major buildings, imagery emphasizing cosmological themes, lack of funerary temples, open market exchange opportunities for the general population, and more decentralized resources, services, and authority. Throughout, our essay about governance, evidence is presented for scholars outside our discipline; we keep archaeological details to a minimum but note sources providing more background.

Brief Archaeological Overview

Initially, during the Gulf Olmec era 1500–400 BCE, sculpture and labor mobilization testify to strong rulers with important ties to ritual (see Pool, 2007 concerning the Gulf Olmecs). Apart from three major, partly sequential, Olmec centers and a few secondary centers (Cyphers, 2008), communal or corporate architecture takes similar but often simpler forms in the countryside and lacks leader representations and equally large-scale labor mobilization (Inomata et al., 2021; Stoner and Stark, 2022). Later, CE 300–900/1000, two dominant architectural plans build upon Olmec era precedents and show great longevity until around CE 800. These two layouts show evidence of both authoritarian and collective governance principles and are our primary focus. See Ladrón de Guevara (2012) for an archaeological overview of the ancient Gulf coast.

Around CE 800, a process of collapse began that brought an end to the long-lived traditions. It changed the sociopolitical landscape profoundly, with a substantial reduction in Gulf population. Some localities witnessed settlement reorganization, and others, the immigration of highland groups (Stark and Eschbach, 2018). Since both the Maya lowlands and the south-central and southern Gulf lowlands experienced a collapse process at about the same time, yet each had different governance emphases, the demise of centers in these areas is not attributable entirely to governance but to a more complex set of interdependencies likely including resources and food production. Possible causes of collapse form a separate issue we do not address.

Location and Data

Pedestrian surveys have generated comprehensive information on settlement patterns, from the largest monumental architecture to common residences (e.g., Santley and Arnold, 1996; Borstein, 2001, 2005; Killion and Urcid, 2001; Symonds, 2002; Symonds et al., 2002; Urcid and Killion, 2008; Stoner, 2011; Loughlin, 2012; Budar, 2016; Daneels, 2016; Stark, 2021). In areas not surveyed on the ground, satellite and lidar (light detection and ranging) remote sensing provide preliminary data on the distribution and configuration of monumental architecture (Stoner, 2017; Inomata et al., 2021; Stoner et al., 2021; Stoner and Stark, 2022). Remote sensing relied mostly on five-m horizontal resolution lidar scans flown across the entire southern half of Veracruz, publicly available from the Instituto Nacional de Geografía y Estadística in Mexico. In some instances, multispectral satellite images (WorldView 2 and 3) assisted in the recognition of architectural configurations, such as the presence of ballcourts. A data base was compiled that coded variables concerning structures and spaces of monumental plaza groups (Stoner and Stark, 2022). The database also drew on archaeological surveys covering about 5,000 km2 of the 53,000 km2 covered by remote sensing.

Through these data, we observe low-density agrarian urbanism forming a distributed urban network (Evans et al., 2007; Isendahl and Smith, 2013; Scarborough and Isendahl, 2020; Stoner and Stark, 2022). In low-density cities, occupation is interspersed with fields and gardens, and monumental epicenters are both widely and regularly distributed. Polities generally do not fit the model of relatively discreet city-state or kingdom territories. Settlement sprawls over a large area with monumental nodes distributed in a network that covers an entire region. Gaps in settlement are rare, but we can recognize cores of centers where the largest and densest arrays of monumental architecture are clustered.

Most of our study area comprises a tropical lowland environment laced with streams and rivers. Different landforms presented diversified agricultural opportunities. One basic agricultural pursuit for parts of the entire area involved extensive swidden fields. Swidden requires fallow periods and crop rotation to rebound from nutrient depletion. During the CE 300–900 period, however, many groups added more diverse and intensive agricultural techniques: raised fields in wetlands, limited terracing of hill slopes, and recessional planting in seasonal wetlands (Sluyter and Siemens, 1992; Heimo et al., 2004; Stoner et al., 2021). More intensive agricultural methods permitted somewhat larger population densities around some monumental centers (Daneels, 2020). Evidence of strategies to preserve wet season rain accumulations well into the dry season also dot the landscape. Stoner et al. (2021) identified canals linked to natural water catchment sinks. Several researchers have observed that the borrow pits excavated to obtain materials to build up earthen architecture were likely filled with water for much of the year (Daneels, 2020), and in some cases were also connected into networks of raised field canals (Stoner et al., 2021). In some areas, even common residential mounds are associated with small ponds that would have been useful for splash or pot irrigation (Stark and Ossa, 2007).

Preference was for residence close to agricultural fields. The horizontal expansion of this varied agricultural system, with activities shifting to different landforms seasonally, coincided with an equivalent sprawl of residences. Because settlement spread forced families farther from the monumental centers of public life, outlying people increasingly constructed smaller civic/religious plaza groups closer to their residences. Over the CE 300–900 span, this architectural proliferation led to a more decentralized pattern of interactions with new architectural nodes in the hinterlands duplicating key services formerly offered only in the older centers.

Olmec Era Antecedents

Three partly sequential Gulf centers are renowned for the carving of multi-ton basalt monuments from stone blocks hauled up to 70 km from the Tuxtla Mountains, a low volcanic massif situated on the coast (see Pool, 2007 for synthesis about Olmecs). At the earliest center, San Lorenzo, massive leveling of a natural plateau represents a considerable mobilization of labor (Cyphers, 1997, 2012). Colossal heads carved in basalt show important individuals, linking these considerable labor investments to specific leaders. Other monuments feature supernatural themes, suggesting an important role for ritual in Olmec society. Later, at the center of La Venta, a tall earthen mound, buried offerings of mosaic pavements, and a tomb constructed of basalt columns, presumably for an important leader, constitute some of the spectacular remains. Tres Zapotes, a third Olmec center also produced sculpted heads and basalt columns, but it was especially active during the transition away from the Olmec style.

Recent discoveries show that when San Lorenzo and La Venta thrived, out in the countryside people were engaged in construction of extremely large public plazas, up to a kilometer long, but, with few exceptions (so far as known), without the investment in sculptures lionizing rulers. These long rectangular plazas are distributed across southern Veracruz and into Tabasco (Inomata et al., 2021) and show several variants, but their proportions and plans resemble those of San Lorenzo and La Venta on a more modest scale of earth-moving. The plazas seem to represent a widespread mobilization of communities in construction of ritual places without all the trappings of centralized autocratic rule, although local leaders may have played roles in planning and coordinating the construction (see ethnographic Mapuche, Dillehay, 1990). Thus, the Olmec era now has evidence of collective activities represented by these countryside site plans, as well as the emergence of more autocratic leaders at a few big Olmec centers. Other archaeological evidence not detailed here contributes information about community- or household-scale ritual and economic activities not tied to authoritarian rule (Stoner and Stark, 2022).

The transition to later societies (CE 300–900) is not well-understood, in part because many of the centers built at that time continued in use with later rebuilding and additions. Tres Zapotes, though, provides helpful information. It had four plazas with a similar layout between 400 BCE and CE 300. The repetition of the Tres Zapotes Plaza Group suggests multiple segments in the settlement rather than a single centralized authority (Pool, 2008). Highly centralized authority seen in Olmec times had waned in favor of multiple groups with corporate functions—minimally the building and upkeep of structures.

Gulf Polities CE 300–900

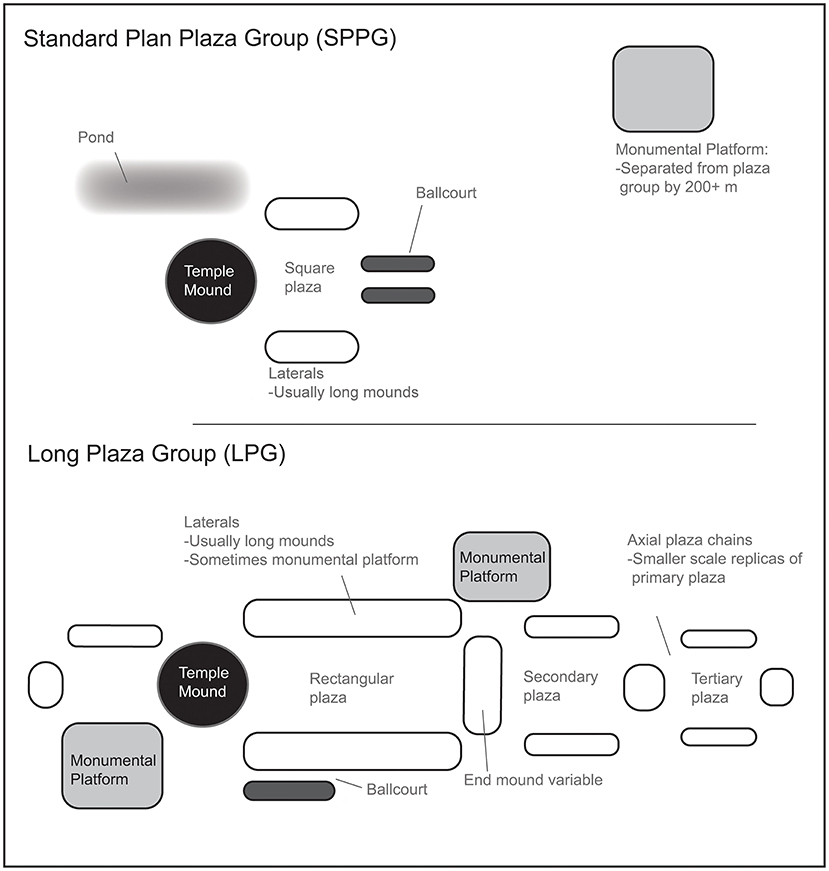

In south-central Veracruz, by about CE 300, a distinctive architectural layout of structures around a plaza had appeared in south-central Veracruz. Daneels (2016:207–215) labeled the arrangement the Standard Plan because of its widely repeated canon (Figure 2). In her original definition a temple mound was positioned at one end of a roughly square plaza. Opposite the temple mound was a ballcourt for the Mesoamerican ballgame, a competition with cosmic symbolism of death and rebirth (sometimes a ballplayer or stand-in was sacrificed). Usually, long mounds were placed on both sides of the plaza, but occasionally only one with the opposite side left open. We refer to this as the Standard Plan Plaza Group (SPPG). Daneels includes in her definition the presence of a monumental palatial platform within 200 m, a subsidiary plaza, and often artificial ponds.

Figure 2. The Standard Plan Plaza Group (above) and the Long Plaza Group (below) in idealized diagrams.

We concentrate on the main plaza, with its service functions: (1) temple rituals, likely in accord with the Mesoamerican calendar; (2) sport and ritual at the ballcourt, with an architectural court consisting of two elongate mounds with a narrow playing alley between them; and (3) an institutional role for long mounds, each likely representing a corporate group with rights to property and particular actions. Our analogy is multiroom long structures in the Maya highlands and lowlands, which provided locations for corporate groups, possibly important lineages or councils, to conduct affairs in a civic context. At Tres Zapotes, excavations on or behind three long mounds yielded some residential trash (Pool, 2008:129, 133, 138). SPPG long mounds may have housed permanent personnel and/or have been occupied periodically. (4) Plazas potentially hosted periodic markets, and evidence for market distribution of products is beginning to appear (Pool and Stoner, 2008; Stark and Ossa, 2010; Stoner, 2013; Ossa, 2021).

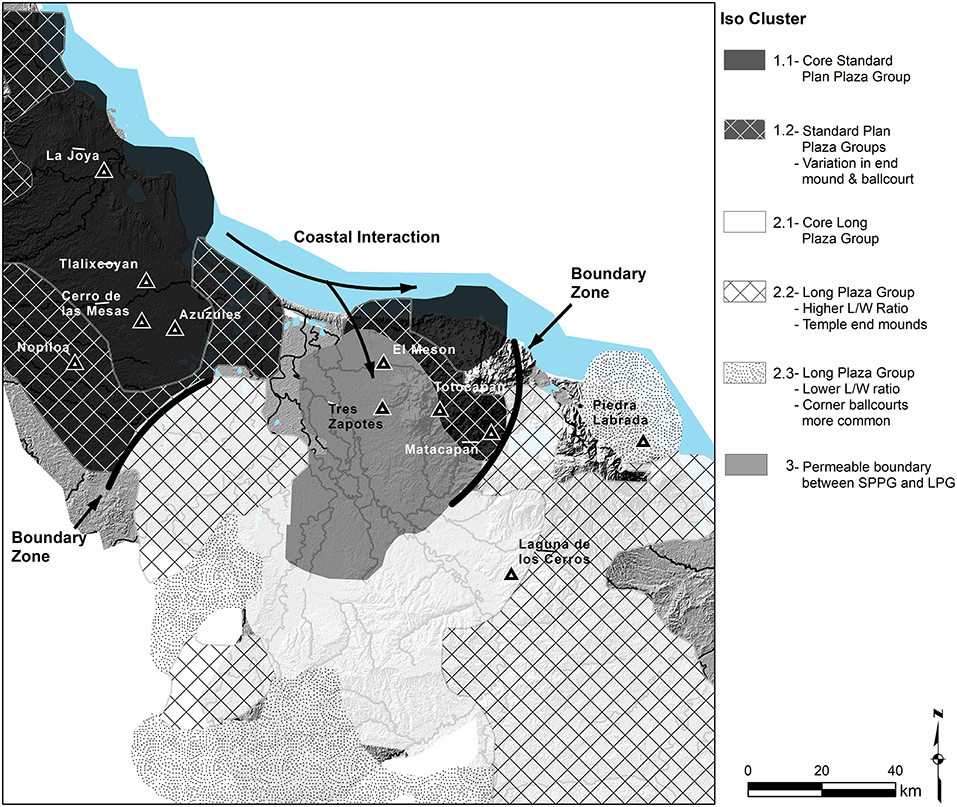

The SPPG arrangements, with little variation (Stoner and Stark, 2022), are spread across a large spatial extent, ~7,500 km2 in south-central Veracruz and across multiple polities (Figure 3). They endure until ca. CE 900. Typically, they are found at first and second ranked centers, but at lower ranked centers the strict canons of architectural planning are often relaxed or one or more ingredients of the SPPG may be missing, especially the ballcourt (Stark, 2021).

Figure 3. The distribution of Standard Plan Plaza Groups and variants and of the Long Plaza Groups and variants in south-central and southern Veracruz.

In most of southern Veracruz, a related arrangement is characteristic, the Long Plaza Group (LPG) (see Figure 2). It bears a close resemblance in its proportions to some of the Olmec era elongate plazas, but it is not as large and, typically, has an architectural ball court. A temple mound occupies one end of the plaza, and the opposite end may have a long mound, another temple mound, or a monumental platform. The sides of the plaza are occupied by long mounds (longer than the SPPG ones, and they extend to the ends of the plaza). The ballcourt is created by a mound flanking one of the long mounds outside the plaza (rather than the end of the plaza opposite the temple as with the SPPG). Not uncommonly, a chain of long plazas of diminishing sizes extends along the axial line, perhaps representing ranked groups or lineages. Some archaeologists have proposed a settlement hiatus between the Olmec occupation and the development of LPGs, assigning the LPG to the Late Classic period (Symonds et al., 2002; Borstein, 2005) but this time gap remains to be tested with a broader sample of radiocarbon dates. The total extent of the LPG group is hard to judge and, as with the SPPG, there are some variants, but the main concentration covers an area of ~14,000 km2 (Figure 3). Overall, fewer field investigations have studied the LPGs, especially excavations of key structures and documentation of surrounding habitations.

Evidence Related to Governance Principles

We address each of the categories of evidence mentioned at the outset, noting whether it points to autocratic or collective principles in governance. Blanton and Fargher (2008) show that societies vary in the degree to which they express either principle. Polar contrasts are not typical.

Sources of Revenue for Polities

Comparative studies indicate that revenues from internally produced wealth that is not localized and readily sequestered tends to promote more collective action in governance (Blanton and Fargher, 2008). We assess Gulf lowland resources valued in Mesoamerica and how localized they were.

South-Central Veracruz

South-central Veracruz was a major cotton producer in Aztec times according to ethnohistoric documents from the time of the Spanish conquest, and fiber processing implements suggest widespread production at commoner households during the period considered here (Stark, 2020). Cotton was in wide demand in highland areas where it did not grow, and it provided a basis for trade (e.g., exchange for highland obsidian for cutting edges and volcanic grinding stones to process corn into flour). Cotton was a basis for internal production of agricultural wealth in south-central Veracruz. Evidence shows that spinning cotton into thread took place in common residential contexts, evading centralized control. Other valued tropical resources for both south-central and southern Veracruz included feathers of colorful birds, jaguar pelts, rubber, cacao, liquidambar, honey, and seashells. Like cotton they were not highly localized and could be obtained by a variety of people. Because of reliable seasonal rainfall and possibilities for agricultural intensification in wetlands (e.g., raised fields), foodstuffs could be widely produced (Stoner, 2017; Stoner et al., 2021). In the Tlalixcoyan Basin in south-central Veracruz, Stoner et al. (2021) observed that maintenance and regulation of impounded waters and field drainage for raised fields appears to have been distributed among public plaza nodes representing localized cooperation among farmers rather than centralized control.

To an unknown extent, elites or rulers may have played a key role in arranging “foreign” exchanges with high-ranking people in highland polities or in arranging access to distant markets there. Nevertheless, it seems unlikely they had a stranglehold on long-distance exchanges in view of the widespread access to imported highland obsidian and metates used routinely by commoner households. Grinding tools for processing maize do not seem to have come to south-central Veracruz from the nearby Tuxtla Mountains. Recent Gulf research indicates open exchanges, such as would occur in market contexts (Pool and Stoner, 2008; Stark and Ossa, 2010; Stoner, 2013; Ossa, 2021). We presume that Gulf elites and rulers required in kind taxes and labor from commoners, but they also may have had their own lands with attached client farmers. A proliferation of polities, most of them not too different from one another in the amount of monumental construction, suggests that it was difficult for rulers in any one polity to amass wealth and power far beyond the scale of their neighbors, an indication that valued products could not be accumulated in an extremely disproportionate manner.

Southern Veracruz

We lack relevant archaeological data for most of southern Veracruz (Hall, 1997 is an exception), but cotton could have been grown there [although not as well as in south-central Veracruz, which has less winter rain (Stark et al., 1998)]. Some other traits are similar to south-central Veracruz, such as widespread agricultural production, widespread availability of valued fauna, and an extensive network of comparable centers.

Accessibility of Plaza Groups

Whether public core buildings and services are readily accessible is one indicator of whether they serve the general population or are more exclusively controlled by privileged governing authorities (Feinman and Carballo, 2018:10).

South-Central Veracruz

Particularly in the SPPG layouts, entrance to the plaza and its urban services is relatively unimpeded at the four corners of the plaza. The SPPG are not surrounded by walls, and residential mounds typically occur nearby. The vast majority of plaza groups in the region are in easily accessible on ground level in valley bottoms or on terraces overlooking floodplains. Very few are elevated on natural or artificial rises, which might restrict access to the populace. Thus, spatial patterns allow the populace access to the plaza to witness ceremonies or assemblies. Political strategies likely favored attraction of large gatherings: an inclusive rather than exclusive principle. The SPPG ballcourts have limited opportunities to witness the game because the court lies between two closely spaced flanking mounds which restrict viewership (Stark and Stoner, 2017). The number of people who could be accommodated with a good view of the game is only about 10% of those who could assemble in plazas to witness processions or ceremonies on a temple mound. Ceremonies and processions before or after the game may have been held in the adjacent main plaza, however, and widely viewed. Overall, the abundance and relatively close spacing of SPPGs points to convenient access to their services.

Southern Veracruz

The LPG plazas have somewhat more restricted access because the long lateral mounds extend along the length of the plaza, but people could still file into the plaza at the four corners. The LPG plazas also lack surrounding walls or other restrictions to access. As with the SPPG locations, the LPG are readily accessible in valley bottoms or on terraces. The LPG plazas on average are longer but narrower than the SPPG plazas, and thus have less area to accommodate people, but the differences are not great. Viewership of LPG ballcourts has not been measured but should be somewhat higher than for the SPPG ballcourts because one of the sides of the playing field is bounded by a long lateral mound, usually longer and taller than the opposing ballcourt mound. The use of a plaza long mound on one side of the court suggests that the group represented by the long mound had a particular role in construction or maintenance of the court and in viewing the game. If so, the position of the court reflects a more proprietary relationship than in the SPPG.

In cases of chains of LPG plazas, multiple plazas accommodated what likely were somewhat distinct crowds, perhaps representing different districts or lineages. In sum, both the SPPG and LPG arrangements provided urban services that were accessible to the population, but the LPGs are less open and the ballcourts are possibly sponsored by a particular corporate group. The profusion of centers offering similar services also suggests good access for the populace.

Placement of Palatial Platforms

The centrality of palaces is a trait identified by Carballo and Feinman (2016:292) as sensitive in respect to the degree of collective action in governance. If palaces are not central in settlements, collective action is likely to be higher. We discuss the degree to which palaces are adjacent to or contiguous to the main plazas of centers.

South-Central Veracruz

In the CE 300–900 interval, monumental palatial platforms are usually associated with rank 1 and rank 2 SPPG centers where pedestrian surveys have yielded a settlement hierarchy (e.g., Daneels, 2016; Stark, 2021). These platforms often have additional mounds constructed on top, usually including a long mound that may have supported a row of residential rooms. The structures on top of the platforms may have been used for residential, ritual, and administrative activities. Excavations at La Joya show diverse functions for rooms and spaces, some residential, some for audiences, and one room where maize was stored (Daneels, 2011:465). The SPPG monumental platforms vary in size but commonly are large, usually slightly longer than wide. Among 50 platforms mapped in one project (Stark, 2021), half were 90 m or more in length and 30 were 5 m or more in height. The scale of the earthen platforms indicates wider labor mobilization than the elite household. The residents may have been royals, collaterals, or other elite persons.

Monumental platform placement in the SPPG arrangement is at distances between 200 and 1,000 m from the main plaza. This physical separation from the nucleus of urban services indicates a degree of separation of wealthy families and/or authoritarian rulers from important civic life. Although it is likely that rulers helped commission and organize some of the construction around SPPG plazas, those spaces also hosted corporate groups with a prominent civic position. The two poles of authority provide evidence of a mix of governance principles.

At lower levels in the SPPG settlement hierarchy, 3rd and 4th ranked centers typically lack either ball courts or monumental platforms. They also tend to deviate from the rigid adherence to the SPPG layout principles. The long mounds that may represent key groups are still present along with temple mounds, but the lower-order settlements have little evidence of local authoritarian leaders because of the lack of carvings and monumental platforms in all but a few cases, and they likely operated on a more collective community basis.

Southern Veracruz

As was the case in south-central Veracruz, monumental platforms are typically found at rank 1 and 2 plaza groups. LPG plazas differ from the SPPG arrangements, however, because monumental platforms are typically placed fronting the plaza or at its corners. This close association suggests a greater role for leaders in supervising and organizing public activities. Lidar imagery shows that in some cases of chained plazas, there are multiple monumental platforms, likely an indication of divided rule, with important persons in lower-ranked plazas playing some roles in decision making. We see this as a variant of the segmental patterns mentioned earlier for Tres Zapotes.

Presence and Prominence of Corporate Architecture

A prominent position of structures representing corporate groups in civic centers is an indicator of the degree to which they played a central role in public affairs. This expectation is analogous to the one above concerning the placement of palatial residences. A few Maya centers have a possible council house fronting an important plaza in the center (if not the main plaza) and interpreted by Stomper (1996:246–294) as representing elite councilors to dynasts. In the most thoroughly studied example at Copan, Stomper (2001) notes the council house was created during a possible time of dynastic change, not a constant structure at the center.

South-Central and Southern Veracruz

Interpreted as structures representing corporate groups, the lateral mounds in both the SPPG and LPG are among the defining structures for the plaza group arrangements. In the case of the SPPG, they usually are present as two lateral mounds, but sometimes only one, especially at low-ranked centers or in subsidiary plazas within some later settlements. In the western lower Papaloapan basin, single laterals are more common in the CE 600–900 interval than earlier, suggesting a decline in the representation of collective actions (Stark, 2016). In contrast, the LPGs rather consistently have two lateral long mounds, but one may have a ballcourt alongside (but outside the plaza), suggesting a role for people connected to that lateral in oversight or maintenance of the court. With chains of LPGs, the higher number of long mounds suggests factions but also a larger-scale integration of groups. Both the LPG and SPPG arrangements feature corporate group architecture consistently in prominent positions in the main civic plaza(s), and this key positioning holds throughout the CE 300–900 urban tradition, contrasting with the patchier evidence of council houses with the Maya.

Ritual Offerings in Residences and Public Structures

We lack a comparative analysis of patterns of ritual dedicatory or termination offerings at public structures in relation to governance, but, in the study region, differences in the distribution of popular vs. restricted offerings offer evidence about participation in events at centers. As with the ease of access to civic complexes, such patterns can help assess the exclusiveness or inclusiveness of civic structures, which in turn may signal whether autocratic or collection principles predominate.

South-Central Veracruz

Information differs in two drainages in south-central Veracruz where the SPPGs are common, but we have no data concerning ritual offerings for the LPGs in southern Veracruz. In the Cotaxtla-Jamapa drainage, a particular kind of ceramic figurine (dios narigudo) is often buried in grouped arrangements, sometimes in a shallow vessel as dedicatory offerings in palatial platforms (Daneels, 2010). These offerings occur in ordinary residential contexts as well (Daneels, 2008:65–69). This figurine style is not found in the western lower Papaloapan basin, where the Tlalixcoyan, Blanco, and other rivers flow toward the lagoons and swamps at the mouth of the Papaloapan. Instead, other figurines are characteristic, such as the “smiling figurines” (sonrientes) (Medellín Zenil and Peterson, 1954). Sonrientes have been recovered from residential excavations (Stark, 2001:188) and from burials in monumental structures at the site of Zapotal (Torres Guzmán, 1972:5). Although the figurine styles are different, in both drainages the presence of particular figurines in residential and public monumental contexts indicates a degree of integration of commoner ritual practices in rituals connected with monumental structures. Such broad participation is in keeping with a degree of involvement of the general population in civic and ritual affairs and a collective emphasis in governance.

In contrast to the figurine evidence, Daneels (2017) notes from her excavations at La Joya and from published reports, mainly from south-central Veracruz, that human sacrifice in dedicatory deposits for monumental structures is almost entirely confined to rank 1 and 2 centers. She interprets this pattern as an indication of a state cult separate from the ones related to figurines. These sacrificial deposits suggest a dichotomy in ritual and a link to higher level authorities who likely played key roles in orchestrating the building labor. Overall, ritual evidence is split, with some aspects pointing to collective and others to authoritarian principles. The contrast does not conform exactly to a contrast identified by Brumfiel (1998, 2001) between Aztec state ideology and commoner ideology as expressed in figurines. Aztec commoner figurines were not incorporated into state rituals, and household rituals generally emphasized subsistence themes, not warfare and sacrifice that were prominent in Aztec state rituals.

Sculptural and Ritual Themes

Sculpture or other public imagery that prioritizes individual leaders and their ancestry to legitimize rule point to autocratic principles in governance. Conversely the prominence of mythic and cosmic themes apart from rulers presents more universal messages that may underwrite the polity. These two emphases are distinguished by Carballo and Feinman (2016:292).

South-Central and Southern Veracruz

In Olmec times, portrayals of leaders are prominent but other works feature sacred imagery of supernatural realms or creatures. The Formative plazas out in the countryside shown in remote sensing have not produced stone sculpture (widespread modern farming and ranching activities make it unlikely that stone monuments are common at these plazas because they have not been reported).

Monument carving continued from 600 BCE to approximately CE 1 in the Tuxtla Mountains at Tres Zapotes in the eastern lower Papaloapan basin (Pool, 2010) and later at other sites in the lower Papaloapan drainage, such as El Mesón, La Mojarra, and Cerro de las Mesas. The last center gained its greatest extent during CE 300–600 and continued to produce stone carvings, some of them showing leaders accompanied by Long-Count calendar dates and writing (Stirling, 1943; Justeson and Kaufman, 2008). This continuation of carvings lionizing leaders at Cerro de las Mesas is not typical elsewhere in south-central and southern Veracruz. By CE 600–900, two successor primary centers in south-central Veracruz each produced only one or two stone monuments (Nopiloa and Azuzules). Leaders are not shown (but the stelae from Azuzules are uncarved—perhaps stuccoed or painted surfaces have been lost). Elsewhere, stone monuments are not reported from the myriad SPPG centers, nor from LPG centers. Thus, for most of Veracruz, stone carving featuring leaders is not present CE 300–600 and, even in the area dominated by Cerro de las Mesas, it wanes after about CE 600. This signature of authoritarian power at major centers undergoes a marked process of decline following the Gulf Olmec era.

Funerary Temples

In the Maya lowlands, some pyramidal platforms for temples were also funerary mounds containing the tomb of an exalted ruler (Coe, 1956). Lucero (2007) mentions the funerary temple mounds were not very common, however. Like the Maya carved monuments and inscriptions recording events in the lives of rulers, they point to authoritarian rule.

South-Central Veracruz

The presence of funerary temples for exalted rulers is uncertain for the Gulf lowlands. Few Gulf temple mounds have been excavated by archaeologists with modern methods, so information is scarce. In one case, a burial of an important person was encountered at La Joya associated with temple mound construction (Daneels and Ruvalcaba Sil, 2012). In view of the amount of looting of monumental structures in the region (including southern Veracruz), the evidence is meager for a strong funerary mound tradition. Local people often report looting, prompting investigation by personnel from national archaeological institute that governs archaeological and historical sites.

Open or Restricted Exchange

Blanton and Fargher (2010; 2016:260) argue that a market system with open access for exchange is an economic asset to households and tends to occur with more collective emphases in governance. Open exchange in markets affords families flexible opportunities to exchange their products for other items. Marketplaces can be hard to locate because ephemeral stalls may be erected in a plaza, and meticulous excavation is required to obtain chemical or mineral residues or postholes to indicate market stalls (Coronel et al., 2015). Nevertheless, two categories of information suggest that market systems, likely periodic markets, existed CE 300–900 and continued to the Spanish conquest (CE 900–1521).

South-Central and Southern Veracruz

One category of evidence is specialization in production. Obsidian tool manufacture, pottery manufacture, and salt production have been detected that suggest production beyond household needs coupled with a distribution system that supplied many households with utilitarian items (e.g., Santley et al., 1989; Stark, 1989; Barrett, 2003; Santley, 2004; Pool and Stoner, 2008). For the interval CE 300–900, some studies have examined fall-off patterns around centers in the incidence of products at households to argue for open exchanges in a market system (Stark and Ossa, 2010; Stoner, 2013; Ossa, 2021). Although less visible architecturally than temples and ballcourts, market activities would have been an important service at centers.

The Degree of Centralization of Resources, Public Services, and Authority

Blanton and Fargher (2008) use the prevalence of public goods as one trait linked to more collective governance. Highly centralized services will not be convenient to the population in low-density urbanism because people are spread out. If the population is spread out to take advantage of agricultural resources but central authority and civic structures are nucleated, the latter will mainly serve commoners in the immediate vicinity of the capital and associated elite and ruling groups. Centralization concentrates services at the primary center and would be congruent with more authoritarian governance.

South-Central and Southern Veracruz

Our remote sensing database shows that plaza groups, ranked by size of structures, associated secondary plazas, and service facilities such as ballcourts, are widely distributed (Stoner and Stark, 2022). The average distance between rank 1 plaza groups, the largest in each area that provide the full range of services as evident from the building inventories found there, is 9.8 km. If space is apportioned to each rank 1 plaza group according to Thiessen polygons, each encompasses a variety of lesser ranked plaza groups in the space allocated to them. The overall picture shows a proliferation of various ranks of centers and a relatively close spacing of plaza groups, affording families the opportunity to attend events not only at the higher-ranked plaza groups nearest to them but also those in neighboring areas. Buildings for key public services are repeated at multiple plaza groups, not centralized at one or a few centers.

Mesoamerica lacked draft animals and wheeled vehicles, and various studies identify a 30 km radius as the distance feasible to walk to a location and return the same day (e.g., Drennan, 1984; Hansen, 2000; Rosenswig, 2021). Gulf Classic period rank 1 plaza groups are more closely spaced. Across the study area, the average walk to the nearest rank 1 plaza group is < 5 km (roughly half the average spacing between them), and 1.25 km when plaza groups of all ranks are considered. Social and kin relationships were likely maintained across plaza group service areas. The standardized layouts would have promoted inclusion of visitors from neighboring areas by using recognized architectural patterns. Further, there are few signs of any defensive architecture or defensive site positioning, commensurate with an open network.

Agricultural fields also point to local controls. Tlalixcoyan and Blanco wetlands in south-central Veracruz have abundant raised fields. Lower-ranked centers are distributed through the area and could have provided local community coordination of canal and reservoir maintenance (Stoner, 2017; Stoner et al., 2021).

Discussion

Several categories of evidence during the CE 300–900 interval support the idea of both authoritarian and collective governance principles. From the Olmec era through CE 300–900, indicators of collective voice are fairly steady in their presence (with different manifestations) even though there are signs of shifting emphases over time according to parts of the study area. Governance strategies employed at and near the top of the settlement hierarchy do not correspond closely with those that are emphasized at lower levels, where less authoritarian activity is indicated.

Throughout the transition into and during CE 300–900, our most consistently available data are architectural and support the idea of corporate groups participating in governance—perhaps gaining ground as the sculptural investments focused on leaders declined. Nevertheless, palatial platforms continued to be built and renovated. They testify to the presence of wealthy powerful families, some of whom undoubtedly played important roles as leaders or rulers, perhaps partly sponsoring and also organizing some of the civic construction. In the SPPG case, palatial residences seldom front the main plaza and are located at varying distances away, but in the LPG arrangements monumental platforms were closely integrated, suggestive of a stronger role.

Eventually, during CE 600–900, there are indications that collective political action weakened. In survey in the western lower Papaloapan basin, plazas with a single lateral long mound, rather than two, became more common, possibly reflecting a drop in collective representation in civic affairs (Stark, 2016, 2021). Also, palatial monumental platforms proliferated, many of them likely representing headquarters of estates of important families (Stark, 2021). A shift toward more authoritarian power (perhaps oligarchic) and increasing wealth differentials may have heralded social strains before the collapse of the urban network. Nevertheless, LPGs proliferated during CE 600–900. LPGs have palatial monumental platforms positioned facing the main plaza or in a corner of the plaza, allowing closer oversight. As noted, the plazas are not as open as in south-central Veracruz, and the ballcourt is positioned alongside one of the long lateral mounds, perhaps a sign that one public function had come under the oversight of corporate groups.

Key questions remain concerning how and why political and economic power tilted back toward elites (in at least some locations) late in the long tradition of a mix of principles. We lack the archaeological data necessary to address these questions, but one possibility is the acquisition of more land by prominent elites who relied on client farmers to produce food and valued products (see Klassen and Evans, 2020:4, for a related process in the Khmer Angkoran realm). Archaeologists will need precise building sequences and dates to assess the roles of monumental platforms as estate headquarters. All the categories of monumental structures, including at different settlement ranks, warrant careful excavations to assess their functions, any ritual deposits, building sequences, timing, and labor investments. Evaluation of the economic well-being of a range of households over time will also provide significant data to determine how commoners fared.

In terms of collective action as an important principle in ancient societies, the Veracruz archaeological record corresponds relatively well to a persistent mix of principles. There is no indication of inherent instability, but the balance is dynamic. Was the Gulf area an example of “good” government? We avoid the “good” label in general, but note that the centers show the presence of both elites and important corporate civic groups. The proliferation of a network of centers diffused autocratic power, rather than centralizing it, and produced a political and social mosaic of checks and balances and interdependencies. See Martin (2020:esp. 374–378) for an argument about a political balance of power among Classic Maya polities, but he includes a role for conflict and warfare that is not yet documented at the same scale in the Gulf area.

The profound changes starting around CE 800 seem to lend support to the suggestions by Blanton and Fargher (2010) that complex societies emphasizing collective principles are more vulnerable to collapse, but neighboring Classic Maya centers and their authoritarian royal dynasties also underwent collapse. Inversely, Pool and Loughlin (2015) attribute the earlier resiliency of Tres Zapotes, compared to other Olmec centers that declined, to a shift to more collective governance. Polities decline or collapse for many reasons, and as yet we lack sufficient data to assess these processes in relation to collective action. We suggest analyses of interactions among low-density urban centers across a broad regional framework to determine if these inter-dependencies rendered them more susceptible to a spread of problems across the network.

Although many of the criteria for evaluating collective action and governmental accountability mentioned by Blanton et al. (2021) as part of their essay about good government are inaccessible for a purely archaeological case, there is nevertheless striking archaeological evidence for a mix of principles. As yet there is no equivalent cross-cultural schema for evaluating archaeological cases to Blanton and Fargher's (2008) framework, but Feinman and Carballo (2018) advance several criteria, and some of the criteria we employed can be applied to or reformulated for other cases. The research question shifts in our case study, from scoring a sample of polities with the same criteria to asking what criteria can be applied to available evidence and for which governance principles is there strong evidence. We examined variation spatially and temporally (the SPPG and LPG patterns and their antecedents). With over 2,000 years of a mix in governance principles on the basis of architectural and other evidence, the Gulf record is not easily subsumed in traditional neoevolutionary schema. Our regional data contribute to the indications that substantial internal revenue corresponds with considerable collective action in governance because of widespread production of both foods and tropical items valued in external exchange. We also point to low-density urbanism as a particular framework for examining governance because at a regional scale it accommodates interdependencies and a degree of checks and balances among polities and powerful individuals within them.

Comparative data for Angkor in Cambodia and for the lowland Classic Maya are too complex to discuss in detail, but a few points show the challenges and potential for comparisons. The prevailing settlement patterns involve low-density urbanism, but there is more evidence from Maya and Angkor research for some particularly large and sometimes denser centers (see, e.g., Evans et al., 2013; Hutson, 2016). Nevertheless, in both cases population and smaller civic-religious centers spread out across the countryside. All three examples of low-density urbanism encompass important internal variation, which is still being actively addressed by researchers. Only the Gulf area is characterized by extensive repetition of architectural layouts, which may signal a greater intensity of cross-cutting relationships (but relevant lidar data about outlying nodes in the Angkor realm are not yet assessed).

Each comparative case has evidence of authoritarian principles (e.g., for Angkor, Carter et al., 2021; for the Maya, Freidel, 2012; Martin, 2020). Because of the amount of research focused on major centers and associated inscriptions, both Angkor and the Maya have well-documented powerful rulers and centers. Evidence for collective action has yet to be assessed consistently for them. Collective action is addressed indirectly for Angkor and the Maya by arguments in favor of a degree of local independent action. Both have more evidence of infrastructural investments in roadways or hydraulic features than we have detected for the Gulf area (greater infrastructural investments and other public goods have been argued by Blanton and Fargher (2008:133–164) to be associated with more collective action). In parts of the Gulf lowlands and in the Angkor realm, smaller local nodes for water management likely contributed to the proliferation of collective representation, but not all the Gulf lowlands nor most of the Maya lowlands had a similar scale of water management for food production. All three display an important role for internal resource production, associated cross-culturally with more possibilities for collective action. In short, continued attention to interest groups and decision-making and actions at different levels is warranted. We suspect that the regional-scale interdependencies among communities and centers, characteristic in low-density urbanism and rooted in ecological conditions, contributed to a diffusion of authoritarian power that accommodated a degree of collective action. In the Gulf case, expressions of collective action can be detected over an extremely long time and with a relatively prominent role.

Author Contributions

BS designed the initial organization of the manuscript. BS and WS contributed relevant data and drafted sections of the manuscript. Both authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editors for their invitation to participate and for helpful suggestions from them, three reviewers, and Michael Smith to improve our essay, but they are not responsible for the content. The essay draws upon a number of sources of data, and we thank Gulf colleagues for their research that made an overview of governance principles possible.

References

Arnold III, P. J., and Pool, C. A. (2008). “Charting Classic Veracruz,” in Classic Period Cultural Currents in Southern and Central Veracruz, eds P. J. Arnold III and C. A. Pool (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection), 1–21.

Barrett, T. P. (2003). Tuxtlas obsidian: organization and change in a regional craft industry. (Dissertation). University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, United States.

Blanton, R. E., and Fargher, L. F. (2008). Collective Action in the Formation of Pre-modern States. New York, NY: Springer.

Blanton, R. E., and Fargher, L. F. (2010). “Evaluating causal factors in market development in premodern states: a comparative study, with critical comments on the history of ideas about markets,” in Archaeological Approaches to Market Exchange in Ancient Societies, eds C. P. Garraty and B. L. Stark (Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado), 207–226.

Blanton, R. E., and Fargher, L. F. (2016). How Humans Cooperate: Confronting the Challenges of Collective Action. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado.

Blanton, R. E., Fargher, L. F., Feinman, G. M., and Kowalewski, S. A. (2021). The fiscal economy of good government. Curr. Anthropol. 62, 77–100. doi: 10.1086/713286

Blanton, R. E., Feinman, G. M., Kowalewski, S. A., and Peregrine, P. N. (1996). A dual-processual theory for the evolution of Mesoamerican civilization. Curr. Anthropol. 37, 1–14. doi: 10.1086/204471

Borstein, J. A. (2001). Tripping over colossal heads: settlement patterns and population development in the upland Olmec heartland (Dissertation). Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA, United States.

Borstein, J. A. (2005). Epiclassic political organization in southern Veracruz, Mexico: segmentary versus centralized integration. Ancient Mesoamerica 16, 11–21. doi: 10.1017/S095653610505008X

Brumfiel, E. M. (1998). Huitzilopochtli's conquest: Aztec ideology in the archaeological record. Cambridge Archaeol. J. 8, 3–13. doi: 10.1017/S095977430000127X

Brumfiel, E. M. (2001). “Aztec hearts and minds: religion and the state in the Aztec empire,” in Empires: Perspectives from Archaeology and History, eds S. E. Alcock, T. N. D'Altroy, K. D. Morrison, and C. M. Sinopoli (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 283–310.

Brumfiel, E. M., and Fox, J. W., (eds.). (1994). Factional Competition and Political Development in the New World. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Budar, L. (2016). “El corredor costero del volcán de Santa Marta el otro lado de Los Tuxtlas,” in Arqueología de Los Tuxtlas: Antiguos paisajes, nuevas miradas, eds L. Budar and P. J. Arnold III (Xalapa, Veracruz, México: Universidad Veracruzana), 73–92.

Carballo, D. M., and Feinman, G. M. (2016). Cooperation, collective action, and the archaeology of large-scale societies. Evol. Anthropol. 26, 288–296. doi: 10.1002/evan.21506

Carneiro, R. L. (1970). A theory of the origin of the state. Science 169, 733–738. doi: 10.1126/science.169.3947.733

Carter, A. K., Klassen, S., Stark, M. T., Polkinghorne, M., Heng, P., Evans, D., et al. (2021). The evolution of agro-urbanism: a case study from Angkor, Cambodia. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 63, 101323. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2021.101323

Coe, M. D. (1956). The funerary temple among the Classic Maya. Southwest. J. Anthropol. 12, 387–394. doi: 10.1086/soutjanth.12.4.3629063

Coronel, E. G., Hutson, S., Magnoni, A., Balzotti, C., Ulmer, A., and Terry, R. E. (2015). Geochemical analysis of Late Classic and Postclassic Maya marketplace activities at the plazas of Cobá, Mexico. J. Field Archaeol. 40, 89–109. doi: 10.1179/0093469014Z.000000000107

Cyphers, A. (1997). “Olmec architecture at San Lorenzo,” in Olmec to Aztec: Settlement Patterns in the Ancient Gulf Lowlands, eds B. L. Stark and P. J. Arnold III (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press), 96–114.

Cyphers, A. (2008). “Los tronos y la configuración del poder olmeca,” in Ideología, política y sociedad en el periodo Formativo, eds A. Cyphers and K. G. Hirth (México, DF: Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México), 311–341.

Cyphers, A. (2012). Las bellas teorías y los terribles hechos: Controversias sobre los olmecas del Preclásico Inferior. México, DF: Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Daneels, A. (2010). “Earthen architecture in Classic Period Central Veracruz, Mexico: development and function,” in Monumental Questions: Prehistoric Megaliths, Mounds, and Enclosures, British Archaeological Reports, International Series, BAR S2123, eds D. Calado, M. Baldia, and M. Boulanger (Oxford: Archaeopress), 223–230.

Daneels, A. (2011). “Arquitectura cívica-ceremonial de tierra en la costa del Golfo: el sitio de La Joya y el urbanismo del periodo Clásico,” in Monte Albán en la crucijada regional y disciplinaria: Memoria de la Quinta Mesa Redonda de Monte Albán, ed N. M. Robles García and A. I. Rivera Guzmán (México, DF: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia), 445–477.

Daneels, A. (2016). Juego de pelota y política: Un estudio sobre cómo se desarrolló la sociedad del periodo Clásico en el Centro de Veracruz. México, DF: Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Daneels, A. (2017). “Arquitectura y sacrificio humano: la importancia política e ideológica de los depósitos rituales en la arquitectura monumental de tierra en el centro-sur de Veracruz,” in Arqueología de la Costa del Golfo: Dinámicas de la interacción política, económia e ideológica, eds L. Budar, M. L. Venter, and S. Ladrón de Guevara (Xalapa, Veracruz: Arqueología de Paisaje y Cosmovisión UV-CA-258, Facultad de Antropología, Universidad Veracruzana, and Administración Portuaria Integral de Veracruz), 179–200.

Daneels, A. (2020). “El agua en la arquitectura y la arquitectura del agua en el Centro-sur de Veracruz durante el Clásico,” in Uso y Representación del Agua en la Costa del Golfo, eds L. Budar and S. Ladrón de Guevara (Xalapa, Veracruz, México: Universidad Veracruzana), 95–110.

Daneels, A., and Ruvalcaba Sil, J. L. (2012). “Cuentas de piedra verde en una residencia Clásica del Centro de Veracruz,” in El jade y otras piedras verdes: perspectivas interdisciplinarias e interculturales, eds W. Wiesheu and G. Guzzi (México, DF: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia-CONACULTA), 81–114.

Dillehay, T. D. (1990). Mapuche ceremonial landscape, social recruitment and resource rights. World Archaeol. 22, 223–241. doi: 10.1080/00438243.1990.9980142

Drennan, R. D. (1984). Long-distance transport costs in pre-Hispanic Mesoamerica. Am. Anthropol. 86, 105–112. doi: 10.1525/aa.1984.86.1.02a00100

Ehrenreich, R. M., Crumley, C. L., and Levy, J. E., (eds.) (1995). Heterarchy and the Analysis of Complex Societies. Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association No. 6. Arlington, VA: American Anthropological Association.

Evans, D., Fletcher, R., Pottier, C., Chevance, J. -B., Soutif, D., Tan, B. S., et al. (2013). Uncovering archaeological landscapes at Angkor using LiDAR. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 12595–12600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306539110

Evans, D., Pottier, C., Fletcher, R., Hensley, S., Tapley, I., Milne, A., et al. (2007). A comprehensive archaeological map of the world's largest preindustrial settlement complex at Angkor, Cambodia. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 14277–14282. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702525104

Fargher, L. F., Blanton, R. E., and Heredia Espinoza, V. Y. (2010). Egalitarian ideology and political power in prehispanic Central Mexico: the case of Tlaxcallan. Latin Am. Antiq. 21, 227–251. doi: 10.7183/1045-6635.21.3.227

Fargher, L. F., Blanton, R. E., Heredia Espinoza, V. Y., Millhauser, J., Xiuhtecutli, N., and Overholtzer, L. (2011). Tlaxcallan: the archaeology of an ancient republic in the New World. Antiquity 85, 172–186. doi: 10.1017/S0003598X0006751X

Feinman, G. M., and Carballo, D. M. (2018). Collaborative and competitive strategies in the variability and resiliency of large-scale societies in Mesoamerica. Econ. Anthropol. 5, 7–19. doi: 10.1002/sea2.12098

Freidel, D. A. (2012). “Maya divine kingship,” in Religion and Power: Divine Kingship in the Ancient World and Beyond, ed N. Brisch (Chicago, IL: The Oriental Institute, University of Chicago), 191–206.

Fried, M. H. (1967). The Evolution of Political Society: An Essay in Political Anthropology. New York, NY: Random House.

Hall, B. A. (1997). “Spindle whorls and cotton production at Middle Classic Matacapan and in the Gulf Lowlands,” in Olmec to Aztec: Settlement Patterns in the Ancient Gulf Lowlands, eds B. L. Stark and P. J. Arnold III (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press), 115–135.

Hansen, M. H., (ed.). (2000). A Comparative Study of Thirty City-State Cultures: An Investigation. Copenhagen: Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab.

Heimo, M., Siemens, A. H., and Hebda, R. (2004). Prehispanic changes in wetland topography and their implications to past and future wetland agriculture at Laguna Mandinga, Veracruz, Mexico. Agric. Human Values 21, 313–327. doi: 10.1007/s10460-003-1217-3

Hutson, S. (2016). The Ancient Urban Maya: Neighborhoods, Inequality, and Built Form. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida.

Inomata, T., Fernandez-Diaz, J. C., Triaden, D., García Mollinedo, M., Pinzón, F., García Hernández, M., et al. (2021). Origins and spread of formal ceremonial complexes in the Olmec and Maya regions revealed by airborne lidar. Nat. Human Behav. 5, 1487–1501. doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01218-1

Isendahl, C., and Smith, M. E. (2013). Sustainable agrarian urbanism: the low-density cities of the Mayas and Aztecs. Cities 31, 132–143. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2012.07.012

Justeson, J., and Kaufman, T. (2008). “The epi-Olmec tradition at Cerro de las Mesas in the Classic Period,” in Classic Period Cultural Currents in Southern and Central Veracruz, eds P. J. Arnold III and C. A. Pool (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection), 160–194.

Killion, T. W., and Urcid, J. (2001). The Olmec legacy: cultural continuity and change in Mexico's southern Gulf Coast lowlands. J. Field Archaeol. 28, 3–25. doi: 10.1179/jfa.2001.28.1-2.3

Klassen, S., and Evans, D. (2020). Top-down and bottom-up water management: a diachronic model of changing water management strategies at Angkor, Cambodia. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 58, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2020.101166

Ladrón de Guevara, S., (ed.). (2012). Culturas del Golfo. Milan; Mexico, DF: Editoriale Jaca Book SpA and Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

Loughlin, M. L. (2012). El Mesón regional survey: settlement patterns and political economy in the eastern Papaloapan Basin, Veracruz, Mexico (Dissertation). University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, United States.

Lucero, L. J. (2007). Classic Maya temples, politics, and the voice of the people. Latin Am. Antiq. 18, 407–427. doi: 10.2307/25478195

Martin, S. (2020). Ancient Maya Polities: A Political Anthropology of the Classic Period 150-900 CE. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Medellín Zenil, A., and Peterson, F. A. (1954). A smiling head complex from Central Veracruz, Mexico. Am. Antiq. 20, 162–169. doi: 10.2307/277569

Ossa, A. (2021). “Scaling centers and commerce in Preclassic and Late Classic settlements in South-Central Veracruz,” in Urban Commerce in Ancient Mesoamerica, ed E. H. Paris (Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association), 66–69. doi: 10.1111/apaa.12136

Pool, C. A. (2007). Olmec Archaeology and Early Mesoamerica. Cambridge; New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Pool, C. A. (2008). “Architectural plans, factionalism, and the Proto-Classic-Classic transition at Tres Zapotes,” in Classic Period Cultural Currents in Southern and Central Veracruz, eds P. J. Arnold III and C. A. Pool (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection), 121–158.

Pool, C. A. (2010). “Stone monuments and earthen mounds: polity and placemaking at Tres Zapotes, Veracruz,” in The Place of Stone Monuments: Context, Use, and Meaning in Mesoamerica's Preclassic Transition, eds J. Guernsey, J. E. Clark, and B. Arroyo (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection), 97–127.

Pool, C. A., and Loughlin, M. L. (2015). “Tres Zapotes: the evolution of a resilient polity in the Olmec heartland of Mexico,” in Beyond Collapse: Archaeological Perspectives on Resilience, Revitalization, and Transformation in Complex Societies, Occasional Paper No. 12, ed R. K. Faulseit, (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press), 287–309.

Pool, C. A., and Stoner, W. D. (2008). But Robert, where did the pots go? Ceramic exchange and the economy of ancient Matacapan. J. Anthropol. Res. 64, 411–423. doi: 10.3998/jar.0521004.0064.307

Rosenswig, R. M. (2021). Reconstructing sovereignty on ancient Mesoamerica's southern Pacific coast. Am. Anthropol. 123, 370–388. doi: 10.1111/aman.13566

Santley, R. S. (2004). Prehistoric salt production at El Salado, Veracruz, Mexico. Latin Am. Antiq. 15, 199–221. doi: 10.2307/4141554

Santley, R. S., and Arnold III, P. J. (1996). Prehispanic settlement patterns in the Tuxtla Mountains, Southern Veracruz, Mexico. J. Field Archaeol. 23, 225–249. doi: 10.2307/530505

Santley, R. S., Arnold III, P. J., and Pool, C. A. (1989). The ceramics production system at Matacapan, Veracruz, Mexico. J. Field Archaeol. 16, 107–132. doi: 10.1179/jfa.1989.16.1.107

Scarborough, V. L., and Isendahl, C. (2020). Distributed urban network systems in the tropical archaeological record: toward a model for urban sustainability in the era of climate change. Anthropocene Rev. 7, 208–230. doi: 10.1177/2053019620919242

Service, E. R. (1971/1962). Primitive Social Organization: An Evolutionary Perspective, 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Random House.

Service, E. R. (1975). Origins of the State and Civilization: The Process of Cultural Evolution. New York, NY: W. W. Norton and Company, Inc.

Sluyter, A., and Siemens, A. H. (1992). Vestiges of prehispanic, sloping-field terraces on the piedmont of Central Veracruz, Mexico. Latin Am. Antiq. 3, 148–160. doi: 10.2307/971941

Small, D. B. (2009). The dual-processual model in ancient Greece: applying a post-neoevolutionary model to a data-rich environment. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 28, 205–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2009.02.004

Stark, B. L. (1989). Patarata Pottery: Classic Period Ceramics of the South-central Gulf Coast, Veracruz, Mexico. Anthropological Papers of the University of Arizona no. 51. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press.

Stark, B. L. (2001). “Figurines and other artifacts,” in Classic Period Mixtequilla, Veracruz, Mexico: Diachronic Inferences from Residential Investigations, Monograph 12, ed B. L. Stark (Albany, NY: Institute for Mesoamerican Studies. The University at Albany), 179–226.

Stark, B. L. (2016). “Central precinct replications,” in Alternative Pathways to Complexity: A Collection of Essays on Architecture, Economics, Power, and Cross-Cultural Analysis, eds L. F. Fargher and V. Y. Heredia Espinoza (Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado), 105–130.

Stark, B. L. (2020). Long-term economic change: craft extensification in the Mesoamerican cotton textile industry. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 59, 1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2020.101194

Stark, B. L. (2021). The Archaeology of Political Organization: Urbanism in Classic Period Veracruz, Mexico, Monograph 72. Los Angeles: UCLA Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press.

Stark, B. L., and Eschbach, K. L. (2018). Collapse and diverse responses in the Gulf lowlands, Mexico. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 50, 98–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2018.03.001

Stark, B. L., Heller, L., and Ohnersorgen, M. A. (1998). People with cloth: Mesoamerican economic change from the perspective of cotton in South-Central Veracruz. Latin Am. Antiq. 9, 7–36. doi: 10.2307/972126

Stark, B. L., and Ossa, A. (2007). Ancient settlement, urban gardening, and environment in the Gulf lowlands of Mexico. Latin Am. Antiq. 18, 385–406. doi: 10.2307/25478194

Stark, B. L., and Ossa, A. (2010). “Origins and development of Mesoamerican marketing: evidence from South-central Veracruz, Mexico,” in Archaeological Approaches to Market Exchange in Ancient Societies, eds C. P. Garraty and B. L. Stark (Boulder, CO: University of Colorado Press), 99–126.

Stark, B. L., and Stoner, W. D. (2017). Watching the game: viewership of architectural Mesoamerican ball courts. Latin Am. Antiq. 28, 409–430. doi: 10.1017/laq.2017.36

Stirling, M. W. (1943). Stone Monuments of Southern Mexico. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office.

Stomper, J. A. (1996). The popol na: a model for ancient Maya community structure at Copán, Honduras (Dissertation). Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States.

Stomper, J. A. (2001). “A model for Late Classic community structure at Copán, Honduras,” in Landscape and Power in Ancient Mesoamerica, eds R. Koontz, K. Reese-Taylor, and A. Headrick (Boulder, CO: Westview Press), 197–229.

Stoner, W. D. (2011). Disjuncture among Classic period cultural landscapes in the Tuxtla Mountains, Southern Veracruz, Mexico (Dissertation). University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, United States.

Stoner, W. D. (2013). Interpolity pottery exchange in the Tuxtla Mountains, Southern Veracruz, Mexico. Latin Am. Antiq. 24, 262–288. doi: 10.7183/1045-6635.24.3.262

Stoner, W. D. (2017). Risk, agricultural intensification, political administration, and collapse in the Classic Period Gulf lowlands: a view from above. J. Archaeol. Sci. 80, 83–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2017.02.002

Stoner, W. D., and Stark, B. L. (2022). Low-density urbanism in the Gulf lowlands of Veracruz. SocArXiv[Preprint]. doi: 10.31235/osf.io/x29ht

Stoner, W. D., Stark, B. L., Vanderwarker, A., and Urquhart, K. R. (2021). Between land and water: hydraulic engineering in the Tlalixcoyan Basin, Veracruz, Mexico. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 61, 1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2020.101264

Symonds, S., Cyphers, A., and Lunagómez, R. (2002). Asentamiento prehispánico en San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán. México, DF: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Symonds, S. C. (2002). Settlement distribution and the development of cultural complexity in the lower Coatzacoalcos drainage, Veracruz, Mexico: an archaeological survey at San Lorenzo Tenochtitlan (Dissertation). Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, United States.

Torres Guzmán, M. (1972). Hallazgos en El Zapotal, Ver: informe preliminar (segunda temporada). Boletín INAH, Época II 2, 3–8.

Urcid, J., and Killion, T. W. (2008). “Social landscapes and political dynamics in the southern Gulf Coast lowlands (AD 500-1000),” in Classic Period Cultural Currents in Southern and Central Veracruz, eds P. J. Arnold III and C. A. Pool (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection), 259–291.

Wittfogel, K. A. (1957). Oriental Despotism: A Comparative Study of Total Power. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Keywords: governance, autocratic, collective, archaeology, Gulf lowlands, Veracruz, Mexico

Citation: Stark BL and Stoner WD (2022) Mixed Governance Principles in the Gulf Lowlands of Mesoamerica. Front. Polit. Sci. 4:814545. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2022.814545

Received: 13 November 2021; Accepted: 02 March 2022;

Published: 28 April 2022.

Edited by:

Gary M. Feinman, Field Museum of Natural History, United StatesReviewed by:

Christopher Pool, University of Kentucky, United StatesChris Beekman, University of Colorado Denver, United States

Annick Daneels, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico

Copyright © 2022 Stark and Stoner. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Barbara L. Stark, blstark@asu.edu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Barbara L. Stark

Barbara L. Stark Wesley D. Stoner

Wesley D. Stoner