- 1School of Education, Guangzhou University, Guangzhou, China

- 2Zhongshan Institute, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Zhongshan, China

- 3Jiangsu Provincial Key Constructive Laboratory for Big Data of Psychology and Cognitive Science, Yancheng Teachers College, Yancheng, China

- 4Institute of Situational Education and School of Education, Nantong University, Nantong, China

- 5School of Public Administration, Hohai University, Nanjing, China

The theory of the mad genius, a popular cultural fixture for centuries, has received widespread attention in the behavioral sciences. Focusing on a longstanding debate over whether creativity and mental health are positively or negatively correlated, this study first summarized recent relevant studies and meta-analyses and then provided an updated evaluation of this correlation by describing a new and useful perspective for considering the relationship between creativity and mental health. Here, a modified version of the dual-pathway model of creativity was developed to explain the seemingly paradoxical relationship between creativity and mental health. This model can greatly enrich the scientific understanding of the so-called mad genius controversy and further promote the scientific exploration of the link between creativity and mental health or psychopathology.

Introduction

Mental health and creativity are the two critical elements driving the sustainable development of human society. With the continued spread of the COVID-19 pandemic around the world, there is an urgent need to address the deepening threats to individuals' mental health and creativity. According to the World Health Organization (1), mental illness, unlike genius, is not a rare phenomenon. In a recent report that surveyed U.S. adults at the end of June 2020, 31% of the respondents reported symptoms of anxiety or depression, 13% reported starting or increasing substance use, 26% reported stress-related symptoms, and 11% reported having had serious suicidal thoughts in the preceding 30 days. These numbers are almost double the rates estimated before the pandemic (2). The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, an event rife with uncertainty and challenge, has led to a sharp rise in the demand for creativity often seen during such periods of unpredictability and change (3). Essentially, creativity can not only help people find meaning and significance during the pandemic by, for example, giving individuals enjoyment and pleasure but also help them feel an increased sense of purpose in a variety of ways, e.g., by producing better career narratives about their meaning-making at work (4). However, this is not the only reason behind the thirst for creativity during the epidemic; the search for creativity has also stemmed from its importance in scientific discovery and technological breakthroughs. Creativity generally involves the production of original and valuable ideas that can help scientists and medical professionals achieve innovative breakthroughs in epidemic management and vaccine development and therefore save more people. In this sense, examining the association between creativity and mental health is important [e.g., (5)].

Another important reason to examine this issue is the longstanding interest in the madness-creativity nexus or the mad genius hypothesis (6, 7), as illustrated by creative people who suffer or have suffered from serious mental disorders, such as Vincent van Gogh, making this nexus one of the oldest, most controversial and most frequently discussed issues in the domain of creativity (8, 9). In recent decades, many meaningful results have accumulated, including in journal articles [e.g., (8, 9)], chapters [e.g., (10)] and books [e.g., (11, 12)]. Overall, the association between creativity and mental health is an important issue, as partially illustrated by the emergence of the Journal of Creativity in Mental Health. Although the studies mentioned above have made important empirical and conceptual advancements, they are mostly fragmented and scattered and do not provide an integrated, accurate or coherent understanding of the topic (13). Given that several authors have already conducted systemic or scoping reviews, this study takes a different approach to update our understanding of the relationship between creativity and mental health. Specifically, the present study involves a state-of-the-art review, wherein a dichotomous approach is taken to integrate the potential positive and negative association between creativity and mental health.

This study is a narrative review that makes at least three contributions. First, it offers a state-of-the-art introduction on mental health and creativity beyond the so-called mad genius hypothesis. Second, this study attempts to profile and theoretically integrate the plausible but seemingly paradoxical association between creativity and mental health from a novel perspective. Third, the present review helps advance related studies on the association between creativity and psychopathology and on the relationship between creativity and mental health (well- and ill-being). Taken together, we provide many useful insights and helpful scaffolding knowledge about theoretical research and practices regarding creativity and/or mental health. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. We first conceptualize creativity and mental health and then briefly review the findings in the paradox of these two constructs. Next, we critically evaluate previous studies on the association between creativity and mental health and present a novel theoretical account. Finally, the paper ends by describing the new state of the art and recommending directions for future research.

The Paradox of Creativity and Mental Health

This section describes the three steps involved in our research. First, we conceptualize creativity and mental health. Then, we briefly review the negative association between creativity and mental health. Finally, we move to a detailed review of the literature on the positive association between creativity and mental health.

The first step in our analysis was conceptualizing creativity and mental health. Although defining creativity may be easy, establishing a consensual definition of creativity is not. Pursuing differing priorities and focuses, recent studies have provided useful insights into how to conceptualize creativity (14–16). According to one standard definition, creativity is the capacity to produce something new/novel and appropriate/useful within a certain sociocultural context (e.g., devices, ideas, or procedures); this capacity encompasses a creative personality/disposition and creative thinking and typically manifests in a variety of human activities, ranging from everyday life (e.g., environmental adaptation) to advanced technological industries [e.g., medical revolution; see (17)]. Importantly, individual maladaptation to a changing environment can easily result in mental illness and negative mental health trends [see (18)]. Generally, mental health is not a subjective status of the absence of disease but “a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community” (19). This involves positive emotion and positive functioning, which individually represent emotional and psychological well-being (20).

A negative link between creativity and mental health has been speculated for centuries (21), and this idea is still widespread and deeply engrained in contemporary culture (22). Early evidence consisted of observations and examples from the lives of creative individuals (18). The often-cited biographical reports of luminaries, such as Sylvia Plath, as well as those of contemporary creatives, including Carrie Fisher and Amy Winehouse, all provide anecdotal support for the negative connection between creativity and mental health. Empirically, the frequently cited studies by Jamison (23), Andreasen (6), and Ludwig (12), which show a link between mental illness and creativity, have been criticized on the grounds that they involve small, highly specialized samples, use weak and inconsistent methodologies and strongly depend on subjective and anecdotal accounts (24). However, many recent strictly designed investigations have replicated the positive association between mental illness and creativity. Rybakowski and Klonowska (25), for instance, experimentally contrasted patients with bipolar disorder with healthy control participants to examine their potential differences in creativity as measured using the Revised Art Scale and the “inventiveness” subscale of the Berlin Intelligence Structure Test. The study looked for a potential association between creativity and mental illness and provided support for the madness-creativity nexus by showing higher scores among bipolar patients than among healthy persons on some creativity scales. Similarly, based on a cross-sectional design and a multimethod approach, Ruiter and Johnson (26) showed that mania risk is positively associated with self-reported creative achievement and creative personality. Johnson et al. (27) further confirmed the positive association between a validated measure of ambition and creativity.

However, after reviewing the previous literature, we found that there is a paradoxical or varied association between creativity and mental health. Relatively, the negative association between them seems more common than the positive association, with more evidence from the early literature, especially anecdotes, biographies, case studies and qualitative studies, pointing to a negative association between them [e.g., (18, 28)]. However, several humanistic and positive psychologists have argued that outstanding creativity constitutes a sure sign of better mental health (29, 30), a theory that is particularly supported by research using experimental, psychometric, psychiatric, and historiometric methods (31). Empirically, an increasing number of studies have provided evidence that simply engaging in creative activity can benefit physical and mental health [e.g., (32)]. For example, Shen et al. (33) reported a positive correlation between well-being and creativity and a partial mediating role of mindfulness in this positive association. Based on two meta-analyses, Yu and Zhang (34) revealed a negative association between creativity and negative well-being and a positive association between creativity and positive well-being. Further, Acar et al. (35) assessed the association between creativity and mental health or well-being by synthesizing 189 effect sizes obtained from 26 different studies and replicated a significantly positive, yet modest, link between creativity and mental health, implying that creative individuals tend to have higher well-being or that those with higher well-being tend to be more creative.

Moreover, several recent meta-analytical studies have provided direct evidence for the mad genius paradox, supporting a dichotomous association between creativity and mental health. That is, the answer to the question of whether creativity and mental health are positively or negatively correlated is that they correlate in both ways. For example, Taylor (36) conducted a systematic meta-analysis, wherein the link between mood disorder and creativity was evaluated using three separate approaches to determine whether creative persons are more likely to exhibit mood disorders, whether individuals with mood disorders behave more creatively, and whether a correlation exists between creativity and mood disorders as continuous constructs. The results across the three analyses varied. Simply put, creative (as opposed to non-creative) individuals indeed exhibited greater levels of mood disorders, which was true for all types of mood disorders except dysthymic disorder, while individuals with mood disorders did not exhibit different creativity levels than healthy controls. Although all mood disorder types were positively associated with creativity, there was a significantly stronger association with bipolar (and unspecified) than with unipolar disorder. Importantly, this correlation worked only when creativity was measured in terms of creative accomplishment and behavior. Differentiating between approach-based psychopathology (e.g., positive schizotypy) and avoidance-based psychopathology (e.g., anxiety), Baas et al. (37) conducted a meta-analysis of 57 empirical studies to determine possible linkages between risk of psychopathology and creativity in non-clinical samples and observed some meaningful results: a small positive relationship between positive schizotypy and creativity, a small negative correlation between negative schizotypy or anxiety and creativity, and the finding that the risk of bipolar disorder (e.g., hypomania) is positively associated with creativity, while depressive mood is negatively associated (albeit weakly) with creativity.

Ultimately, the pattern of association between creativity and mental health is complex. Early research, particularly case and clinical studies, tended to support the mad genius hypothesis, that is, either that mentally unhealthy people are more creative or that most creative people are mentally unhealthy. However, the results of a growing number of experimental and relatively tightly controlled clinical and subclinical studies have been mixed on this matter, and a notable portion of the research evidence does not fully support the traditional mad genius hypothesis. Thus, in response to these findings, several researchers have drawn on big data and large sample meta-analysis techniques, presenting generally contradictory results with both significant negative and significant positive associations between creativity and psychological well-being as well as with patterns of association not identical across studies or across measures.

A New Theoretical Account Drawn From the Dual-Pathway Model

In this section, we conduct a critical analysis on the matter and now present our view. In addition to some potential confounding factors or mediation variables mentioned in previous studies [e.g., (38, 39)], we contend that the association between creativity and mental health varies according to whether creativity is considered a “disposition (body)” or a “strategy use.” Additionally, creativity is often negatively associated with mental health when it is measured as a relatively stable trait or disposition (personality/ability/achievement), i.e., a trait or ability/achievement, thus reflecting the persistence of creativity mentioned in the dual-pathway model. However, an association in the opposite direction is documented when creativity is considered a “use” or “technique/method,” i.e., a flexible approach mentioned in the proposed model or a strategy use. That is, when creativity is measured in terms of strategy use or situational variables, the association between creativity and mental health is mostly positive. We extend this theoretical idea more specifically below.

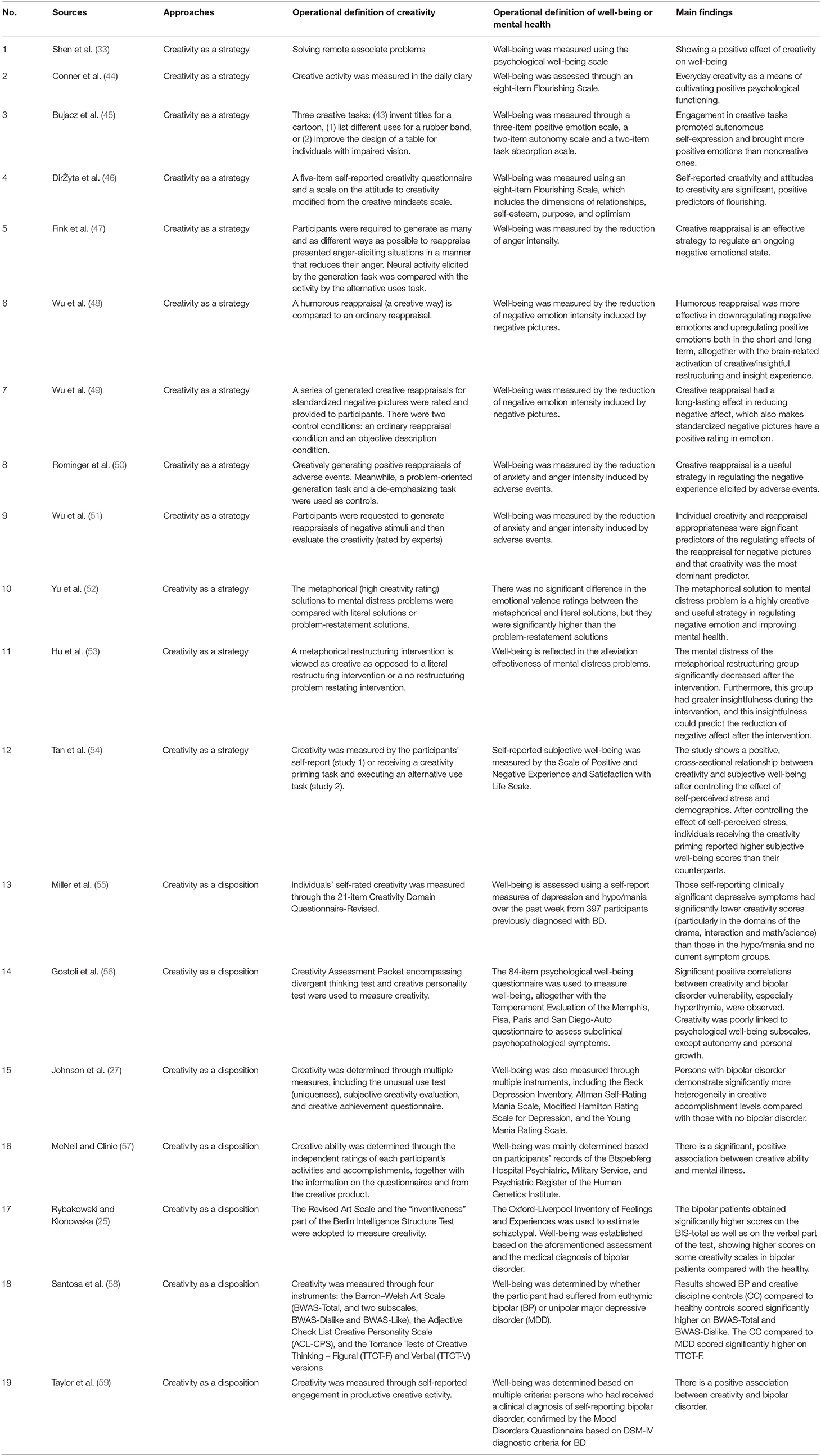

Nijstad et al. (40) proposed a new theory, namely, the dual-pathway model of creativity, which assumes that creativity is a function of cognitive flexibility and cognitive persistence and that dispositional or situational variables can influence creativity through their effects on flexibility, persistence, or both. After a careful review of previous studies, we find that most studies that took the approach of individual difference reported a negative association between creativity and mental health and tended to consider creativity as a type of dispositional or stable difference, that is, either a personality trait or a kind of capability. In fact, creativity is also considered a strategy, which is typically reflected in the expression of creative problem solving. Certain complex problems involve non-routine challenges with no immediately obvious solutions and are not solved until a creative strategy or a novel approach is used. That is, creative problem solving is a strategy or method that attempts to approach a correct solution or a challenge in an innovative way. Another line of studies is improving individuals' creativity performance through priming a creative mindset [e.g., (41)] or instructing them to think differently [e.g., (42)]. Accordingly, creativity is a level of flexibility in certain situations and can vary according to whether it is treated as a strategy. In this regard, creativity can benefit mental health and help individuals improve their mental health. There is no shortage of examples of creativity benefitting mental health in everyday life, such as through creative writing or creative language comprehension, such as humor understanding. For example, for the picture of the vomit in the toilet, creative cognitive reappraisal interprets it as she being inwardly happy that she finally had a child of her own, despite the fact that she threw up a lot. In general, people often experience a surge in emotion and happiness as a result of creative language use or appreciation (e.g., appreciating a visual metaphor) or of the resolution of interpersonal/social dilemmas by engaging in creative self-deprecation [e.g., disparagement humor; for a review, see (43)]. After reviewing previous studies, Table 1 was established to selectively list existing studies on the dichotomous association between creativity and mental health [we provide only a small number of studies supporting the positive association between creativity and mental illness; for more studies, please see some influential reviews or meta-analyses, e.g., (35, 36, 60)]. Specifically, Yu et al. (52), for instance, provided participants with descriptions of various scenarios that included some sort of mental distress and asked them to offer a resolution using one of three solution types: creative, literal, or problem restatement. The authors observed that the emotional positivity and strategic adaptability scores in metaphorical and literal solutions were significantly higher than those in problem restatement solutions. Additionally, the results showed that, compared with literal or problem restatement solutions, creative or metaphorical solutions activated two brain networks, each individually associated with basic metaphorical language processing and insightful problem solving, indicating that the use of creative solutions to resolve problems related to mental distress reliably prompts neural activities that generate positive effects (61). In a recent study by Wu et al. (49), creative reappraisal was reported to have superior performance in regulating emotion, especially negative emotion, accompanying the activation of a similar insight-related network encompassing the hippocampus, amygdala, and striatum. Theoretically, as mentioned above, emotional health is a key part of mental health that typically manifests in appropriately managing or regulating both positive and negative emotions. According to studies on dual-pathway models, positive and negative emotions can flexibly boost creativity or certain key processes of creativity, with negative moods being positively associated with cognitive persistence and positive activating moods being predominantly associated with stronger cognitive flexibility (62). This in turn implies that creativity can boost emotional health through either of these two opposing pathways.

Overall, the present research provides useful insights into the association between creativity and mental health, which could explain some of the complex cognitive and neural processes involved in both creativity and psychopathology and has the potential to paint a clearer picture of some overlapping mechanisms in both constructs rather than linking creativity generally to “madness.”

Discussion and Conclusion

In this study, we review previous research on the association between mental health and creativity. Overall, a dichotomous association is documented, namely, both positive and negative associations are observed. Based on previous findings and the dual-pathway model of creativity, we offer a new view, wherein the positive–negative nature of the association between creativity and mental health is largely determined by the nature of creativity and/or its corresponding measurements. When creativity is conceptualized or operationalized as dispositional, the association is negative, whereas it is positive when creativity is treated as a strategy (e.g., as an intervention method or regulation activity). Indeed, some studies have provided direct support for this idea. For example, Acar et al. (35) found that the approaches to measure creativity are what account for the variation in the association, with a stronger association occurring when creativity is measured by instruments focusing on creative activity and behavior than by those looking at divergent thinking tasks. Nevertheless, we also acknowledge that some alternative explanations cannot be excluded without rigorously controlled studies. For example, Paek et al. (63) conducted a meta-analysis using 89 studies to examine the overall relationships between the most common psychopathologies and little-c creativity and revealed that the overall mean effect size was not different from zero but varied, with effect sizes ranging from −0.97 to 0.95, and 54% of the total effect sizes being below zero and 44.4% of the total effect sizes being above zero. These results actually confirmed the paradoxical association between creativity and mental health. Additionally, their moderator analyses showed that effect sizes varied by the assessment of both psychopathology and creativity as well as by level of intelligence. Furthermore, Drapeau and DeBrule (64) revealed the role of moderating variables, such as the assessment or domain of creativity, in the association between creativity and mental health, wherein the relationships among hypomania, creativity (divergent thinking and creative achievement), and suicidal ideation in college students were examined. Their results showed that, among the creative domains surveyed, students with high creative achievement in architectural design may experience the highest risk for significant suicidal ideation; furthermore, students with visual arts, creative writing, theater/film, and dance achievements were at moderate risk for significant suicidal ideation, thus implying that the (negative) association between creativity and mental health may vary according to the domain of creativity. Future studies could systemically re-examine this new account and exclude alternative accounts [e.g., the inverted-U relationship between creativity and mental illness, see (11); the shared vulnerability model; see Carson (65)] using additional empirical investigations. For example, Ghadirian et al. (66) reported that creativity was at its highest level in patients who suffered a moderate level of manic-depressive illness, whereas the lowest creativity score appeared in the group of patients identified as severely ill.

Taken together, this research provides a novel and useful perspective to evaluate the relationship between creativity and mental health, which has many theoretical or practical implications. Specifically, this research, as a perspective study or mini review, focuses on the association between creativity and mental health, attempting to reconcile the diverging and even contradictory empirical findings regarding the relationship between creativity and mental health. On the one hand, the present research contributes greatly to facilitating positive mental health by showing the positive role of creativity as a strategy to regulate negative emotion and improve positive mental health by creatively reducing negative experiences and insightful or creative reappraisal toward negative situations or things. On the other hand, the current study evaluates a longstanding controversy within the domain of mental health and/or creativity. This research has important implications for future studies on the creativity-well-being nexus and health practices. First, this study hints that, when future research attempts to investigate the relationship between mental health and creativity, they should distinguish between individuals' dispositional creativity and strategic creativity and develop creativity-based mental health adjustment strategies and skills to improve mental health literacy and coping skills. Another important aspect of this study was to deepen the analysis of the concept and structure of mental health literacy and to focus on exploring the constructs, skills, and mechanisms associated with creativity. Practically, this research will help to properly understand the theoretical relevance of creativity and mental health and its models and nudge the application of creativity in the mental health field. In this case, special focus is given to the impact of cognitive reappraisal of creativity and emotional cognitive reappraisal on (emotional) mental health, considering the development of creative regulation strategies and/or creative reappraisal skills as an important component of mental health literacy.

Author Contributions

RZ and WS conceptualized and designed the work. RZ, ZT, and WS drafted the manuscript, with critical comments from QX and FL. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the research fund of Jiangsu Provincial Key Constructive Laboratory for Big Data of Psychology and Cognitive Science (No. 72592162002G), the Guangdong Education Science 2021 Education Science Planning Project A study on digital mental health evaluation system for college students (No. 2021GXJK287) and Guangdong Social Science Planning 2021 project Construction of the Value-added Evaluation system of Adolescents' Mental Health based on Digitization (No. GD21CJY12).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. WHO. Schizophrenia (2019). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/schizophrenia

2. Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E, Wiley JF, Christensen A, Njai R, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. (2020) 69:1049–57. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1

3. Mercier M, Vinchon F, Pichot N, Bonetto E, Bonnardel N, Girandola F, et al. COVID-19: a boon or a bane for creativity? Front Psychol. (2021) 11:3916. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.601150

4. Kapoor H, Kaufman JC. Meaning-making through creativity during COVID-19. Front Psychol. (2020) 11:3659. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.595990

5. Michinov E, Michinov N. Stay at home! When personality profiles influence mental health and creativity during the COVID-19 lockdown. Curr Psychol. (2021). doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-01885-3. [Epub ahead of print].

6. Andreasen NC. Creativity and mental illness: prevalence rates in writers and their first-degree relatives. Am J Psychiatry. (1987) 144:1288–92. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.10.1288

7. Simonton DK. The mad-genius paradox: can creative people be more mentally healthy but highly creative people more mentally ill? Perspect Psychol Sci. (2014) 9:470–80. doi: 10.1177/1745691614543973

8. Fink A, Benedek M, Unterrainer HF, Papousek I, Weiss EM. Creativity and psychopathology: are there similar mental processes involved in creativity and in psychosis-proneness? Front Psychol. (2014) 5:1211. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01211

9. Simonton DK. Creativity and psychopathology: the tenacious mad-genius controversy updated. Curr Opin Behav Sci. (2019) 27:17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2018.07.006

10. Carson SH. Creativity and psychopathology: a relationship of shared neurocognitive vulnerabilities. In: Jung RE, Vartanian O, editors. The Cambridge Handbook of the Neuroscience of Creativity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2018). p. 136–57. doi: 10.1017/9781316556238.009

11. Abraham A. Madness and creativity—yes, no or maybe? Front Psychol. (2015) 6:1055. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01055

12. Ludwig AM. The Price of Greatness: Resolving the Creativity and Madness Controversy. New York, NY: Guilford Press (1995).

13. McEvily B, Perrone V, Zaheer A. Introduction to the special issue on trust in an organizational context. Org Sci. (2003) 14:1–4. doi: 10.1287/orsc.14.1.1.12812

14. Corazza GE. Potential originality and effectiveness: the dynamic definition of creativity. Creat Res J. (2016) 28:258–67. doi: 10.1080/10400419.2016.1195627

15. Runco MA, Jaeger GJ. The standard definition of creativity. Creat Res J. (2012) 24:92–6. doi: 10.1080/10400419.2012.650092

16. Glăveanu VP, Beghetto RA. Creative experience: a non-standard definition of creativity. Creat Res J. (2021) 33:75–80. doi: 10.1080/10400419.2020.1827606

17. Shao Y, Zhang C, Zhou J, Gu T, Yuan Y. How does culture shape creativity? [[i]]A mini-review. Front Psychol. (2019) 10:1219. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01219

18. Carson SH. Creativity and mental illness. In: Kaufman JC, Sternberg RJ, editors. The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity. Cambridge University Press (2019). p. 296–318.

19. WHO. Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice (Summary Report). Geneva: World Health Organization (2004).

20. Galderisi S, Heinz A, Kastrup M, Beezhold J, Sartorius N. Toward a new definition of mental health. World Psychiatry. (2015) 14:231. doi: 10.1002/wps.20231

21. Becker G. The association of creativity and psychopathology: its cultural-historical origins. Creat Res J. (2001) 13:45–53. doi: 10.1207/S15326934CRJ1301_6

22. Kaufman JC, Bromley ML, Cole JC. Insane, poetic, lovable: creativity and endorsement of the “Mad Genius” stereotype. Imagin Cogn Pers. (2006) 26:149–61. doi: 10.2190/J207-3U30-R401-446J

23. Jamison KR. Mood disorders and patterns of creativity in British writers and artists. Psychiatry. (1989) 52:125–34. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1989.11024436

24. Schlesinger J. Creative mythconceptions: A closer look at the evidence for the “mad genius” hypothesis. Psychol Aesthet Creat Arts. (2009) 3:62. doi: 10.1037/a0013975

25. Rybakowski JK, Klonowska P. Bipolar mood disorder, creativity and schizotypy: an experimental study. Psychopathology. (2011) 44:296–302. doi: 10.1159/000322814

26. Ruiter M, Johnson SL. Mania risk and creativity: a multi-method study of the role of motivation. J Affect Disord. (2015) 170:52–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.08.049

27. Johnson SL, Murray G, Hou S, Staudenmaier PJ, Freeman MA, Michalak EE. Creativity is linked to ambition across the bipolar spectrum. J Affect Disord. (2015) 178:160–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.02.021

28. Andreasen NC. The relationship between creativity and mood disorders. Dialog Clin Neurosci. (2008) 10:251. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2008.10.2/ncandreasen

29. Bacon SF. Positive psychology's two cultures. Rev Gen Psychol. (2005) 9:181–92. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.181

30. Cassandro VJ, Simonton DK. Versatility, openness to experience, and topical diversity in creative products: an exploratory historiometric analysis of scientists, philosophers, and writers. J Creat Behav. (2010) 44:9–26. doi: 10.1002/j.2162-6057.2010.tb01322.x

31. Simonton DK. More method in the mad-genius controversy: a historiometric study of 204 historic creators. Psychol Aesthet Creat Arts. (2014) 8:53. doi: 10.1037/a0035367

32. Eschleman KJ, Madsen J, Alarcon G, Barelka A. Benefiting from creative activity: the positive relationships between creative activity, recovery experiences, and performance-related outcomes. J Occup Organ Psychol. (2014) 87:579–98. doi: 10.1111/joop.12064

33. Shen W, Hua M, Wang M, Yuan Y. The mental welfare effect of creativity: how does creativity make people happy? Psychol Health Med. (2020) 26:1045–52. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2020.1781910

34. Yu G, Zhang W. Creativity and mental health: controversies, evidence and prospects. Hebei Acad J. (2020) 40:168–77.

35. Acar S, Tadik H, Myers D, Van der Sman C, Uysal R. Creativity and well-being: a meta-analysis. J Creat Behav. (2021) 55:738–51. doi: 10.1002/jocb.485

36. Taylor CL. Creativity and mood disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Perspect Psychol Sci. (2017) 12:1040–76. doi: 10.1177/1745691617699653

37. Baas M, Nijstad BA, Boot NC, De Dreu CK. Mad genius revisited: vulnerability to psychopathology, biobehavioral approach-avoidance, and creativity. Psychol Bull. (2016) 142:668. doi: 10.1037/bul0000049

38. Kaufman SB, Paul ES. Creativity and schizophrenia spectrum disorders across the arts and sciences. Front Psychol. (2014) 5:1145. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01145

39. Kim KH. Demystifying creativity: what creativity isn't and is? Roeper Rev. (2019) 41:119–28. doi: 10.1080/02783193.2019.1585397

40. Nijstad BA, De Dreu CK, Rietzschel EF, Baas M. The dual pathway to creativity model: creative ideation as a function of flexibility and persistence. Eur Rev Soc Psychol. (2010) 21:34–77. doi: 10.1080/10463281003765323

41. Sassenberg K, Moskowitz GB, Fetterman A, Kessler T. Priming creativity as a strategy to increase creative performance by facilitating the activation and use of remote associations. J Exp Soc Psychol. (2017) 68:128–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2016.06.010

42. Sassenberg K, Moskowitz GB. Don't stereotype, think different! Overcoming automatic stereotype activation by mindset priming. J Exp Soc Psychol. (2005) 41:506–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2004.10.002

43. Li L, Wang F. Disparagement humor: could laughter dissolve hostility? Adv Psychol Sci. (in press). Available online at: http://journal.psych.ac.cn/xlkxjz/CN/

44. Conner TS, DeYoung CG, Silvia PJ. Everyday creative activity as a path to flourishing. J Posit Psychol. (2018) 13:181–9. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2016.1257049

45. Bujacz A, Dunne S, Fink D, Gatej AR, Karlsson E, Ruberti V, et al. Why do we enjoy creative tasks? Results from a multigroup randomized controlled study. Think Skills Creat. (2016) 19:188–97. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2015.11.002

46. DirŽyte A, Kačerauskas T, Perminas A. Associations between happiness, attitudes towards creativity and self-reported creativity in Lithuanian youth sample. Think Skills Creat. (2021) 40:100826. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2021.100826

47. Fink A, Weiss EM, Schwarzl U, Weber H, de Assunção VL, Rominger C, et al. Creative ways to well-being: reappraisal inventiveness in the context of anger-evoking situations. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. (2017) 17:94–105. doi: 10.3758/s13415-016-0465-9

48. Wu X, Guo T, Zhang C, Hong TY, Cheng CM, Wei P, et al. From “Aha!” to “Haha!” using humor to cope with negative stimuli. Cerebral Cortex. (2021) 31:2238–50. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhaa357

49. Wu X, Guo T, Tan T, Zhang W, Qin S, Fan J, et al. Superior emotional regulating effects of creative cognitive reappraisal. Neuroimage. (2019) 200:540–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.06.061

50. Rominger C, Papousek I, Weiss EM, Schulter G, Perchtold CM, Lackner HK, et al. Creative thinking in an emotional context: specific relevance of executive control of emotion-laden representations in the inventiveness in generating alternative appraisals of negative events. Creat Res J. (2018) 30:256–65. doi: 10.1080/10400419.2018.1488196

51. Wu X, Guo T, Tang T, Shi B, Luo J. Role of creativity in the effectiveness of cognitive reappraisal. Front Psychol. (2017) 8:1598. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01598

52. Yu F, Zhang J, Fan J, Luo J, Zhang W. Hippocampus and amygdala: an insight-related network involved in metaphorical solution to mental distress problem. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. (2019) 19:1022–35. doi: 10.3758/s13415-019-00702-6

53. Hu J, Zhang W, Zhang J, Yu F, Zhang X. The brief intervention effect of metaphorical cognitive restructuring on alleviating mental distress: a randomised controlled experiment. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. (2018) 10:414–33. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12133

54. Tan CY, Chuah CQ, Lee ST, Tan CS. Being Creative Makes You Happier: The positive effect of creativity on subjective well-being. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:7244. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18147244

55. Miller N, Perich T, Meade T. Depression, mania and self-reported creativity in bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. (2019) 276:129–33. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.05.006

56. Gostoli S, Cerini V, Piolanti A, Rafanelli C. Creativity, bipolar disorder vulnerability and psychological well-being: a preliminary study. Creat Res J. (2017) 29:63–70. doi: 10.1080/10400419.2017.1263511

57. McNeil TF. Prebirth and postbirth influence on the relationship between creative ability and recorded mental illness 1. J Pers. (1971) 39:391–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1971.tb00050.x

58. Santosa CM, Strong CM, Nowakowska C, Wang PW, Rennicke CM, Ketter TA. Enhanced creativity in bipolar disorder patients: a controlled study. J Affect Disord. (2007) 100:31–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.10.013

59. Taylor K, Fletcher I, Lobban F. Exploring the links between the phenomenology of creativity and bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. (2015) 174:658–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.040

60. Kyaga S, Landén M, Boman M, Hultman CM, Långström N, Lichtenstein P. Mental illness, suicide and creativity: 40-year prospective total population study. J Psychiatr Res. (2013) 47:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.09.010

61. Shen W, Yuan Y, Liu C, Luo J. In search of the ‘Aha!’ experience: elucidating the emotionality of insight problem-solving. Br J Psychol. (2016) 107:281–98. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12142

62. De Dreu CK, Baas M, Nijstad BA. Hedonic tone and activation level in the mood-creativity link: toward a dual pathway to creativity model. J Pers Soc Psychol. (2008) 94:739. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.5.739

63. Paek SH, Abdulla AM, Cramond B. A meta-analysis of the relationship between three common psychopathologies—ADHD, anxiety, and depression—and indicators of little-c creativity. Gifted Child Quar. (2016) 60:117–33. doi: 10.1177/0016986216630600

64. Drapeau CW, DeBrule DS. The relationship of hypomania, creativity, and suicidal ideation in undergraduates. Creat Res J. (2013) 25:75–9. doi: 10.1080/10400419.2013.752231

65. Carson SH. (2011). Creativity and psychopathology: A shared vulnerability model. Can. J. Psychiatry. 56:144–53. doi: 10.1177/070674371105600304

Keywords: dual-pathway model, psychopathology, mental health, creativity, emotion regulation

Citation: Zhao R, Tang Z, Lu F, Xing Q and Shen W (2022) An Updated Evaluation of the Dichotomous Link Between Creativity and Mental Health. Front. Psychiatry 12:781961. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.781961

Received: 23 September 2021; Accepted: 07 December 2021;

Published: 17 January 2022.

Edited by:

Lara Guedes De Pinho, University of Evora, PortugalReviewed by:

Tânia Correia, University of Porto, PortugalDean Keith Simonton, University of California, Davis, United States

Copyright © 2022 Zhao, Tang, Lu, Xing and Shen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhiwen Tang, tangzhiwen@zsc.edu.cn; Fang Lu, tangxiang93@163.com; Qiang Xing, qiang_xingpsy@126.com; Wangbing Shen, won.being.shin@gmail.com

Rongjun Zhao

Rongjun Zhao Zhiwen Tang

Zhiwen Tang Fang Lu3*

Fang Lu3* Qiang Xing

Qiang Xing Wangbing Shen

Wangbing Shen