- 1Peter Boris Centre for Addictions Research, McMaster University and St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton, Hamilton, ON, Canada

- 2Concurrent Disorders Program, St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton, Hamilton, ON, Canada

- 3Homewood Research Institute, Hamilton, ON, Canada

Objective: Inpatient treatment programs for substance use disorders (SUDs) typically have an abstinence policy for patients, but unsanctioned substance use nonetheless takes place and can have significant negative clinical impacts. The current study sought to understand this problem from a patient perspective and to develop strategies for improved contraband substance management in an inpatient concurrent disorders sample.

Methods: First, a qualitative study (n = 10; 60% female) was undertaken to ascertain perceived prevalence, impact, and patient-generated strategies. Second, an anonymous follow-up survey was conducted with unit staff clinicians to evaluate the suggested strategies.

Results: Patients reported that contraband substance use was present and had significant negative consequences clinically. Recommendations from patients included more extensive urine drug screening, the use of drug-sniffing dogs, and direct contingencies for contraband use. Nineteen staff competed an anonymous follow-up questionnaire to evaluate the viability of these strategies, revealing variable perceptions of feasibility and effectiveness.

Conclusion: These findings emphasize the adverse consequences of contraband substance use in addiction treatment programs and identify patient-preferred strategies for managing this challenge.

Introduction

The annual prevalence of substance use disorders (SUDs) in Canada is 3.0–3.8% (1, 2) and 21.6% of Canadians experience a SUD in their lifetime (3). SUDs are commonly comorbid with other psychiatric conditions and, in contrast to the term dual-diagnosis, individuals with a SUD and another psychiatric condition are referred to as concurrent disorder patients in Canada (4). Annually, 1.2–1.7% of the Canadian population age 15 and above meet criteria for a concurrent disorder. These individuals are disproportionately represented in the mental healthcare system (1, 2, 4). Concurrent disorders are associated with several negative health outcomes and high utilization of the healthcare system, particularly emergency services and inpatient treatment programs (4–6). Concurrent disorders have also been found to be associated with more complex healthcare needs, and potentially more severe substance misuse when compared with those without a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis (7).

Treatment programs for SUDs typically adhere to an abstinence-based policy for patients while in care, but use of alcohol, tobacco cannabis, and other illicit substances nonetheless takes place (5, 6, 8, 9). This is consistent across substance use treatment settings and other health care settings, such that non-sanctioned psychoactive substance use is prohibited while on clinical grounds (10). However, precise management strategies and appropriate administrative response is at times unclear and inconsistent (10). In a 2015 study, 44% of participants who reported using illicit drugs had also used illicit drugs while in the hospital (5). Grewal et al. (6) found similar results, such that 43.9% of participants who used illicit drugs also reported using illicit drugs in the hospital in their lifetime. Contraband substance use of tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, and illicit drugs is a persistent issue in clinical settings, posing a risk not only to the patient, but also to other patients, staff, and visitors (5, 6, 8). Patients who use illicit drugs are more likely to be discharged prior to completing treatment due to non-compliance with hospital policies, resulting in negative health outcomes and greater rates of readmissions (4–6).

Research on contraband substance use in mental healthcare settings is limited, with few effective solutions established. The individual impact contraband substance use has on patients in treatment is also not well explored. The present study was initiated to address contraband substance use in an acute concurrent disorders inpatient program at St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton West 5th campus (SJHH-W5) in Hamilton, Ontario with the goal of providing a safer environment for patients and staff while at the hospital. Similar to other clinical settings, contraband substance use is a challenge at SJHH-W5, but the impact of the problem is not well understood. Despite a well-established illicit substance management policy, substance use is known to take place, demonstrating a need for an effective solution. Both staff and patients have expressed negative feelings about the use of substances in the hospital and the need for more effective management strategies. To better understand the scope of the problem, the impact on patients, and develop strategies for improved contraband substance management and patient experience, we conducted a qualitative study with SJHH-W5 inpatients and then a follow-up survey with unit staff. Specifically, the study had three goals: (1) to understand patient perspectives on contraband substances; (2) to solicit patient-recommend strategies for improving management of contraband substances; (3) to evaluate the strategies identified with a follow-up staff survey.

Study 1

Materials and methods

Participants and setting

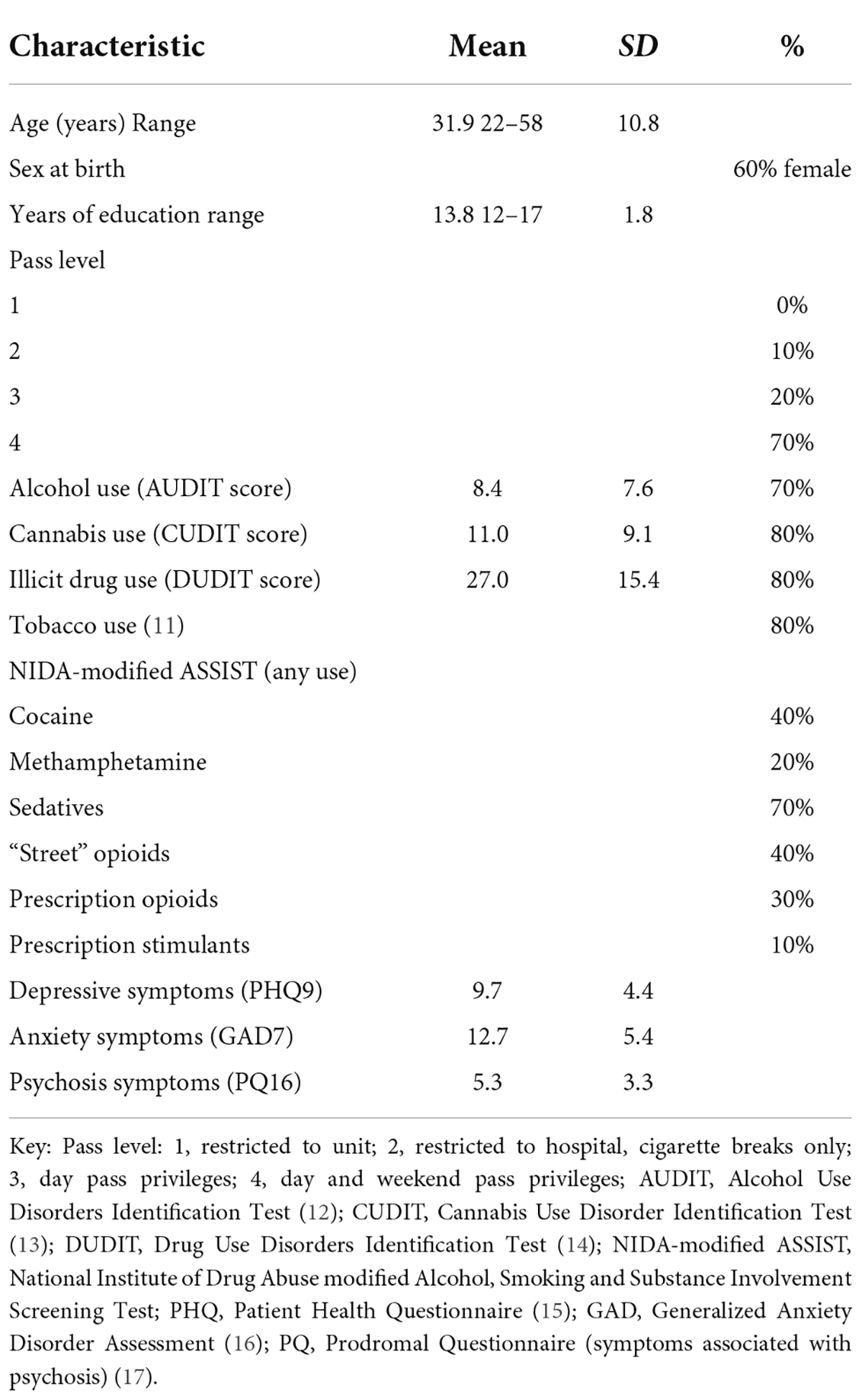

Participants were recruited from a 25-bed acute concurrent disorders inpatient unit at SJHH-W5, between July 2018 and October 2018. All patients on the unit were invited to participate. Inclusion criteria were: (1) > 18 years of age; (2) able to provide informed consent; (3) fluent in English; (4) minimum stay of 7 days. The last criterion was to both ensure psychiatric stability and that all participants had ample exposure to the environment on the unit. Eleven participants expressed interest in the study and were enrolled, but one participant was discontinued for uncooperative behavior, resulting in a sample of 10 (Table 1). All participants had privileges that allowed them to leave the inpatient unit; 70% had privileges permitting them to leave hospital property for extended periods of time with prior approval. Substance use is prohibited within SJHH-W5th and on hospital grounds, including use of tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis. If contraband substances are found on hospital grounds, the substance is confiscated and police are called to collect the substance. It is important to note that police were only contacted about the individual who brought the contraband substance to the hospital if other people were being put at risk as a result.

Procedures and assessments

The research study was advertised on the unit via posters and announcements at inpatient group meetings by research staff (L.R.). Interested participants were contacted and assessed for eligibility. If eligible, informed consent was obtained and an interview was scheduled. Each participant completed an individual 21-question semi-structured qualitative interview with a qualified research assistant (L.R.). The interviews were up to 45-min in length (M = 27 min) and were audio recorded for transcription. Participant responses were iteratively reviewed by the authors to identify common themes throughout data collection. The study adopted a semi-structured framework, such that all participants were asked the same core 21-questions (available upon request), but further individualized questions and prompts were used to explore themes that emerged throughout data collection. The major goal of the interviews was to assess each participant’s experience with contraband substance use at the hospital during their stay on the unit. The interviews also assessed how those experiences had affected their stay at the hospital, impacts on their recovery, and any suggestions they had for staff to better prevent contraband substance use. For descriptive purposes, participants completed self-report assessments of demographics, mental health symptoms and substance use behavior (Table 1). The study was approved by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (Protocol #5015).

Data analysis

All interviews were double transcribed verbatim to ensure accuracy. Qualitative content analysis and open coding modeled data analysis (18). The semi-structured interview items were used to guide initial development of a thematic coding scheme (19, 20). Each transcript was first read from start to finish (L.R. and C.M.) to begin identifying major themes and further develop the coding scheme. With the major themes identified, transcripts were reviewed repeatedly, and individual lines of data were coded and categorized based on the semi-structured interview items. The coding scheme continued to develop throughout data analysis, such that codes were redefined or merged, and new codes and sub-codes were created as new themes emerged. Researchers met regularly with each other, and the larger team throughout code development to discuss and define emerging themes, review the coding structure, and to negotiate discrepancies between coders. When both researchers and the larger team agreed that all major themes had been identified within the data, the coding scheme was complete. Upon completion of the final coding scheme each transcript was again reviewed line-by-line to ensure that all data had been coded according to the final scheme. Data were sorted and themes were quantified based on frequency of endorsement within and across transcripts. Upon completion of data analysis, codes were merged into three overarching themes. The themes were developed to best represent the information and opinions shared by the sample population. These methods are generally consistent with those recommended by the Cochrane Handbook (21), although this study did not solicit feedback from participants on the findings of the interviews throughout data analysis.

Study 1 results

Contraband substance use on hospital grounds and in the hospital

Use of tobacco cigarettes, e-cigarettes, cannabis, and other vaping devices is not permitted anywhere at SJHH-W5. Patients, staff and visitors must go beyond the perimeter of hospital property before using a cigarette, e-cigarette, or vape. Despite this policy, 90% of participants reported frequent and persistent tobacco use on hospital grounds. Individuals were frequently seen smoking tobacco cigarettes outside of the outpatient entrance of the hospital. Most participants (80%) described a high frequency of cannabis use on hospital grounds. Cannabis is used outside on hospital grounds where individuals commonly smoke tobacco cigarettes, as well as near the perimeter of property near a wooded area. The majority of participants (60%) reported that individuals were using illicit drugs on hospital grounds, but did not have many specific examples. See Table 2 for specific examples of contraband substance use on hospital grounds.

Within the hospital, the majority of participants (80%) reported that patients smoke cigarettes. Participants reported that patients smoke cigarettes in their rooms, in bathrooms, or in other common areas, such as the patient gym and stairwells. Some participants admitted to smoking cigarettes in their rooms. They had received advice from other patients on how to use cigarettes on the unit without being noticed. Most participants (70%) described extensive exposure to cannabis use in the hospital. Participants reported smelling cannabis in hallways and stairwells, suggesting that it had been used indoors. Many participants reported being offered cannabis and seeing other patients with cannabis products while on the unit. Most participants (70%) reported that illicit drug use occurs within the hospital. Participants reported seeing or hearing about heroin, fentanyl, and methamphetamine use in the hospital. Materials associated with illicit drug use have been found by participants on the unit. The majority of participants (60%) described encounters with intoxicated patients within the hospital. It was reported that patients used contraband substances within the hospital or returned from an off-campus pass visibly intoxicated by alcohol, cannabis, or illicit drugs. Two participants described a distressing incident of witnessing a co-patient experience an opioid overdose while in the hospital. See Table 2 for specific examples of contraband substance use in the hospital.

Impact of contraband substance use on patients

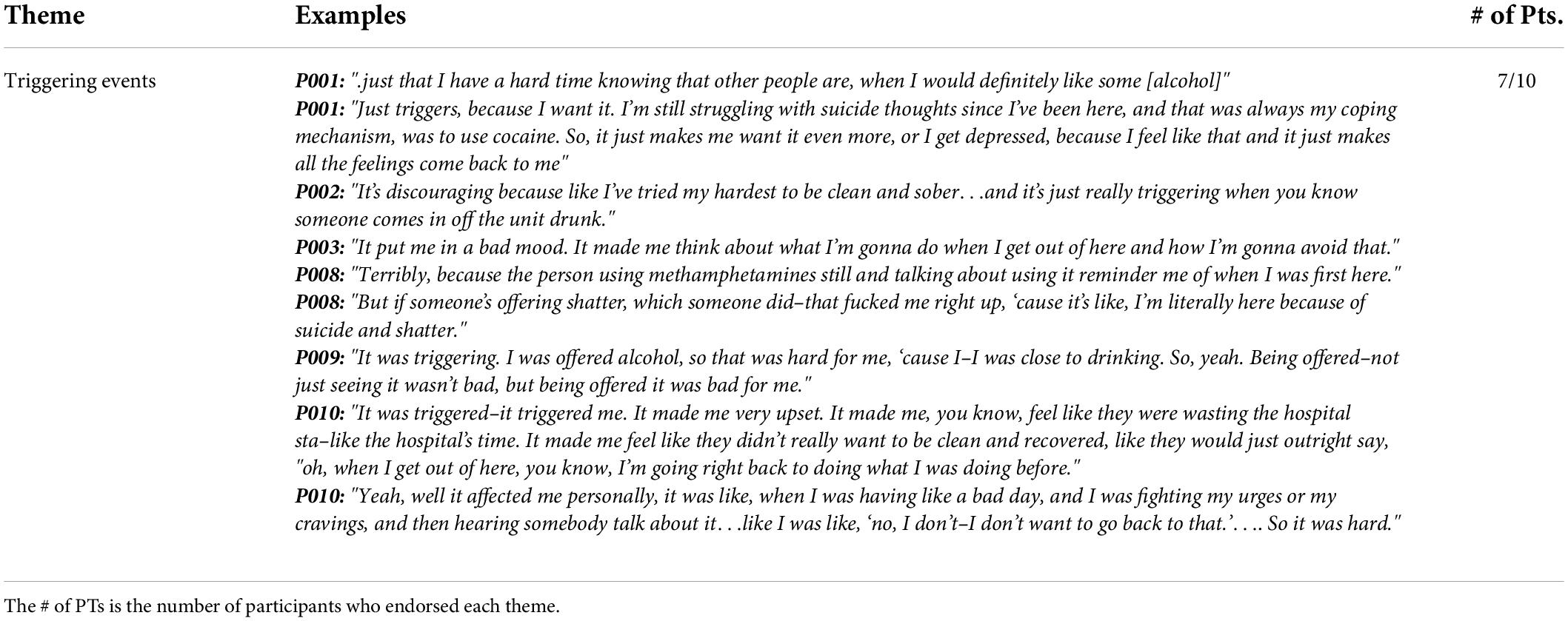

One of the main concerns when addressing this topic is the impact on patient wellbeing. The majority of participants (70%) reported being negatively impacted by the presence of contraband substances at the hospital. Seeing other patients intoxicated, being offered contraband substances, and knowing that patients were using at the hospital was described as “triggering” and frustrating by participants. Participants reported strong cravings, anger toward others, and engaging in substance seeking behavior that interfered with their own recovery. Participants described feeling unsafe in the hospital knowing that contraband substances were present. See Table 3 for specific examples of how participants were affected by contraband substance use in the hospital.

Prospective strategies to prevent contraband substance use

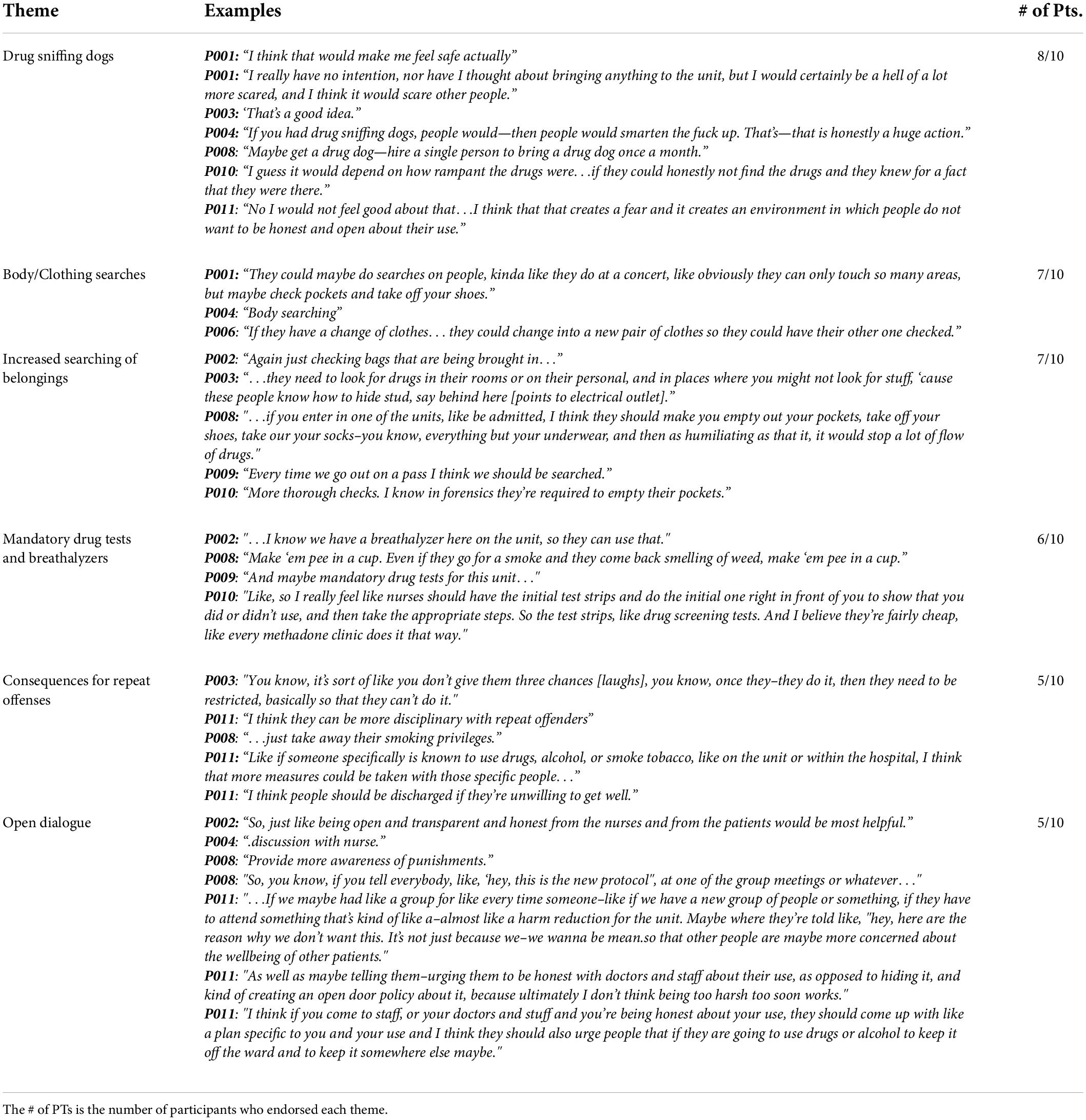

Specific examples of strategies suggested by participants are presented in Table 4. It is routine on the unit for frontline staff to search belongings brought in by patients or visitors. However, several participants (70%) described how patients have been able to smuggle contraband substances such as alcohol, marijuana, and illicit drugs onto the unit by hiding them in their clothing, purses, and backpacks. Many participants suggested that increasing the thoroughness and frequency of clothing and belonging searches on patients would be an effective way to reduce contraband substances from entering the hospital.

Table 4. Direct quotes regarding suggested strategies for staff to prevent contraband substance use in the hospital.

The majority of participants (70%) reported that utilizing drug sniffing dogs on the unit would be effective in not only locating contraband substances, but also preventing them from being brought in. Participants reported that drug sniffing dogs would make them “feel safe” (P001) and would be “a good idea” (P003) for the hospital to implement. One participant noted in reference to drug sniffing dogs that “I really have no intention…about bringing anything to the unit, but I would be a hell of a lot more scared, and I think it would scare other people.” (P001), suggesting a deterrent effect. Two participants reported that drug sniffing dogs may erode trust between patients and staff.

Urine drug screens (UDS) and exhaled breath alcohol tests (i.e., breathalyzers) are currently administered on an as needed basis if a patient is suspected of being intoxicated. Several participants (60%) recommended a more routine system where patients are required to complete a UDS or breathalyzer on a regular basis or whenever they return to the unit after a pass.

Participants expressed an understanding that other patients make mistakes and will use or traffic contraband substances while in treatment. However, 50% of participants suggested that there should be an escalating system of consequences for a patient who persistently traffics or uses contraband substances at SJHH-W5. Participants felt that if a patient repeatedly traffics substances, they should lose their privileges or be discharged for the wellbeing of other patients.

Study 2

Materials and methods

One of the main goals of this study was to evaluate the strategies suggested by participants of Study 1. A follow-up staff assessment was initiated to evaluate some of the strategies that had been suggested by patients for hospital staff to better prevent contraband substance use. Clinical staff on the unit were invited to complete an anonymous survey to evaluate the feasibility and potential efficacy of 10 of the suggested strategies.

Participants

All clinical staff on the unit (i.e., full-time and part-time nurses and addiction counselors) were invited to volunteer to complete the survey anonymously. Nineteen participants completed the survey.

Procedures

Based on study 1, 10 strategies suggested by participants were selected for staff evaluation: (1) body pat-downs on patients when patients re-enter the unit; (2) search patient’s pockets and shoes when they re-enter the unit; (3) search personal belongings when a patient re-enters the unit; (4) drug sniffing dogs on the unit; (5) weekly random drug tests and breathalyzers on patients; (6) search belongings of patient’s visitors; (7) regular searches of patient lockers; (8) move patient lockers onto the unit (“Mailbox” style to allow staff to see the inside of lockers from one side at all times); (9) escalating consequences for repeated offenses; and (10) mandatory groups to discuss rules and consequences of bringing contraband substances onto the unit. The strategies were chosen based on the patient data and clinical priorities. The study was announced at the weekly staff huddle, and paper surveys were made available in the staff meeting room on the unit for 1 month. Staff were invited to complete the survey anonymously by rating each strategy on a 5-point Likert-type scale for feasibility (very feasible, somewhat feasible, unsure, somewhat infeasible, very infeasible) and efficacy (very effective, somewhat effective, unsure, somewhat ineffective, very ineffective). To maintain anonymity, a secure box was placed on the unit to collect the surveys. If staff wanted to participate, they were invited to complete the paper survey and place it in the secure box before the end of the 1 month period. The surveys were gathered from the box by research staff at the end of each workday. All procedures were approved under the same REB protocol.

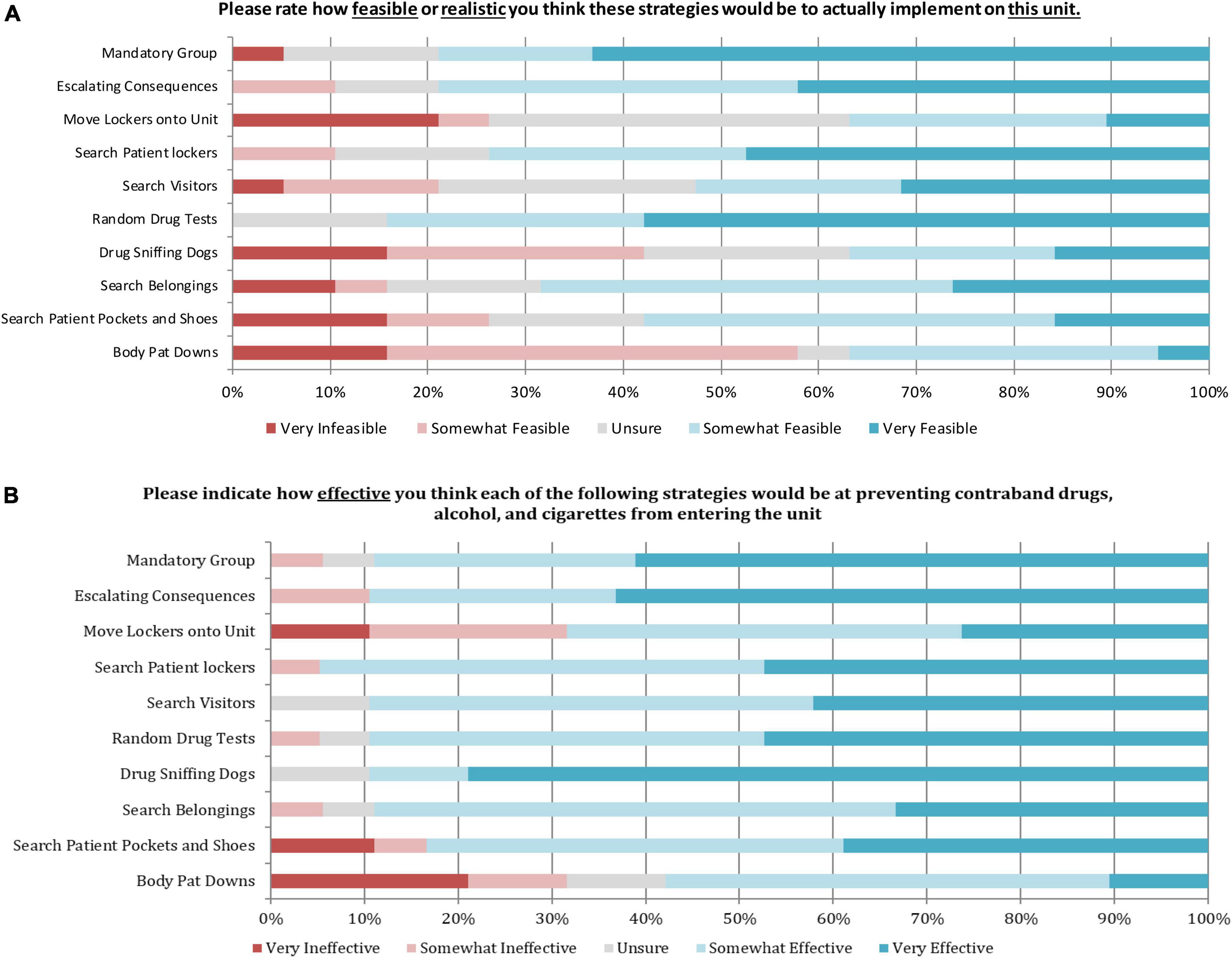

Study 2 results

The results from the survey are presented in Figure 1. Conducting weekly random drug tests and breathalyzers was rated as the most feasible option, with 57.9% of participants rating it as “very feasible” and 26.3% as “somewhat feasible.” Some participants were unsure of the feasibility (26.3%), however, 0% felt that this would be infeasible on the unit. Completing body pat-downs on patients when they re-enter the unit was rated as the least feasible option, with 42.1% of participants rating it as “somewhat infeasible” and 15.8% rating it as very infeasible. Despite that, some staff did feel that body pat-downs were feasible with 31.6% rating the strategy as “somewhat feasible” and 5.3% rating it as “very feasible.” One individual was unsure of the feasibility (5.3%).

Figure 1. Results from the frontline staff survey on the perceived feasibility of the 10 suggested strategies (N = 19). (A) Depicts feasibility. (B) Depicts effectiveness.

Drug sniffing dogs were rated as the most effective strategy with 78.9% of participants rating it as “very effective” and 10.5% reporting it as “somewhat effective.” While some participants were unsure of the effectiveness (10.5%), 0% felt that this would be an ineffective strategy for preventing contraband substance use at SJHH-W5. Patients currently have access to a private locker outside of the unit. Moving patient lockers onto the unit was rated as the least effective strategy with 21.1% of participants rating it as “somewhat ineffective” and 10.1% as “very ineffective.” However, many participants did feel that this would be an effective strategy, as 42.1% rated the strategy as “somewhat effective” and 26.3% felt that it would be “very effective.” Completing body pat-downs on patients when they re-enter the unit was also seen as one of the least effective strategies, as 21.1% of participants believed it would be “very ineffective,” and 10.5% felt that it would be “somewhat ineffective.” Several participants reported that body pat-downs would be effective, as 47.4% rated as “somewhat effective” and 10.5% rated as “very effective,” while others (10.5%) were unsure of the efficacy.

Discussion

The present studies were initiated to gain patient perspectives on contraband substance use on a concurrent disorders inpatient unit, and subsequently solicit strategies from hospital staff in response to patient-generated recommendations. Despite efforts to prevent contraband substance use at the hospital, our findings from study 1 show that use of contraband substances is a significant issue that negatively impacts a patient’s stay and wellbeing. Encounters with contraband substance use at the hospital were reported by the majority of study 1 participants and were described as triggering and upsetting, and many participants reported a negative impact on their recovery. Contraband substance use frequently occurs in common areas of the hospital, including stairwells and around the outside of the building, as well as on the unit in patient rooms and washrooms. Our findings are consistent with previous survey and interview-based studies that found high rates of contraband substance use in hospitals among patients who reported using alcohol or other substances in their lifetime (5, 6, 9, 10). One study from Vancouver, Canada similarly reported that alcohol and other substance use most commonly occurs in washrooms, smoking areas, and in hospital rooms while patients were receiving acute care (6). Another study set in Ontario, Canada reported occurrences of substance use in hospital settings among individuals seeking treatment for non-substance use care. Participants reported leaving the hospital to access drugs, using substances in washrooms or post-surgical rooms, and having substance brought to them by hospital visitors (10). Though neither of the aforementioned studies focused specifically on SUD or concurrent disorder treatment settings, their findings do suggest that contraband substance use is a recurring issue across healthcare settings. Additionally, Strike et al. (10) cited a lack of clear and appropriate administrative response to the presence of contraband substances in the hospital and highlighted the need for a more patient-centered response to the issue. The present study’s focus on patient impact and perspectives hopes to close this gap.

Consistent with previous research, tobacco was commonly used both in the hospital and on hospital grounds despite tobacco-free policies (22). SJHH-W5 adheres to the Smoke Free Ontario Act, such that smoking of any kind is not prohibited within the hospital or on hospital grounds (23). However, participants reported repeated experiences with tobacco use on hospital property, in stairwells, patient rooms, and washrooms. Some participants suggested that the distance required to leave hospital property where smoking is prohibited, combined with the restrictive curfew on the unit motivates patients to smoke within the hospital. Several participants suggested that creating a smoking area on hospital grounds would eliminate the need to smoke in restricted areas, and significantly mitigate the issue. This strategy cannot be implemented, as Ontario laws do not permit smoking of any kind within public establishments, like hospitals, or on hospital property (23). Existing research suggests accessibility to smoking cessation or nicotine replacement products is a possible solution to tobacco use in the hospital, but may not be enough to significantly reduce a patient’s likelihood to smoke (24). Patients on the unit are provided with nicotine replacement products as needed, but still resort to smoking in their rooms and elsewhere in the hospital, suggesting the need for additional approaches to reduce illicit tobacco use.

In addition to tobacco use, alcohol, cannabis, and other illicit drugs were commonly used among patients at the hospital. While other studies have found similar results, few have formulated solutions to the problem. A major goal of this study was to address this gap in the research by soliciting suggestions from patients for staff to better manage contraband substance use at the hospital. Findings from study 1 demonstrated that illicit substance use is a significant issue affecting patients within the hospital. Study 1 also supported the need for further interventions and strategies to manage contraband substance use. To address this, study 2 was initiated to solicit input from frontline staff on potential management strategies suggested by patients. Participants from Study 1 provided several potential strategies based on their perspectives as patients. Our findings reflect that several participants are aware that patients can smuggle contraband substances in and out of the unit on their person or in their personal belongings. Participants reported that patients may commonly return from a pass intoxicated by alcohol or other drugs. To mitigate these behaviors, participants suggested strict policies for searching patient clothing and belongings anytime they return to the unit, as well as frequent searches of patient rooms and lockers. Frontline staff did not see this as a feasible or effective strategy, possibly due to the amount of time and resources required, and the potentially invasive nature.

Breathalyzer tests and UDSs were suggested by patients to occur on a frequent and random basis. Frontline staff also endorsed more frequent breathalyzer tests and UDSs as a feasible and potentially effective strategy, as demonstrated by the results of study 2. It is important to note that breathalyzers and UDSs are currently part of the SJHH-W5 illicit substance management policy. However, participants of study 1 reported that they happen infrequently and only when intoxication is suspected. Implementing a policy where breathalyzers or UDSs can be administered frequently and at random may deter patients from using contraband substances while staying at the hospital. Other units at SJHH-W5 are reported to implement a “marble” strategy, whereby patients are selected at random to receive a UDS and breathalyzer if their marble is selected from a bin. Implementing a similar strategy on other inpatient units may be affective in better integrating regular and random UDSs and breathalyzers as a management strategy.

One of the most popular strategies endorsed by participants was the implementation of drug sniffing dogs. This strategy was seen as a way to not only to find substances that have already been brought onto hospital grounds, but also to deter patients from trafficking contraband substances in the future. Participant’s felt that even the knowledge that drug sniffing dogs could be brought into the facility would reduce the presence of contraband substances in the hospital and increase feelings of safety among patients. Frontline staff expressed agreement with this suggestion, as most participants of study 2 believed it would be an effective strategy. Drug sniffing dogs can be utilized to efficiently and effectively identify and locate illicit substances in public settings (8, 25). Drug sniffing dogs were approved as a strategy at SJHH-W5th in September 2020 following findings from the present study. Drug sniffing dogs were brought into the hospital on two separate occasions, and a thorough search of inpatient units, public spaces, and the hospital perimeter was conducted. Following implementation, feedback was gathered via survey from both staff and patients present during the drug dog visits. Overall, use of drug sniffing dogs was perceived positively by both staff and patients, as both felt it to be an effective and valuable strategy that would benefit the safety of the hospital environment. The majority of staff and patient respondents agreed that the strategy was not an invasion of patient privacy and would be in support of this as on ongoing strategy.

Several considerations bear noting. Our findings were somewhat limited by a relatively small sample size. In addition, the unit is an acute treatment care setting for concurrent disorders patients with a degree of acuity and clinical complexity and, over the course of recruitment, a sizable proportion of patients were unwell or uninterested in participating. Finally, although we anticipate substantial similarities, this study had only one treatment site. All of these factors will potentially affect the generalizability to other clinical settings.

Conclusion

This study provides rich patient perspectives on the issue of contraband substance use on an acute concurrent disorders unit. Several strategies were put forward by the patients who participated and were supported by the frontline staff who would be primarily responsible for implementing new policies. Moving forward, these strategies warrant consideration in similar care settings to create more effective contraband substance management protocols. Maintaining a safe and substance-free environment in acute concurrent disorder inpatient units, and SUD treatment settings more generally, is critical to fostering the best possible clinical outcomes and quality of care.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

LR contributed to protocol development, conducted all data collection, transcription, qualitative coding, data analysis for Study 1 and 2, and wrote the manuscript. HR contributed to study conceptualization, protocol development, and manuscript revisions. BL provided clinical oversight, contributed to protocol development, and manuscript revisions. HG, KH, JB, and MA provided guidance during data analysis and contributed to manuscript revision. JM developed study concept, contributed to protocol development, provided oversight during data collection and analysis, and manuscript revisions. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

JM was supported by the Peter Boris Chair in Addictions Research and a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Translational Addiction Research.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the administrative contributions of Ms. Carmen McPherson.

Conflict of interest

JM was a principal in BEAM Diagnostics, Inc., and a consultant to Clairvoyant Therapeutics, Inc., but neither role has any bearing or relevance to the reported research.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

SJHH-W5, St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton West 5th Campus.

References

1. Rush B, Urbanoski K, Bassani D, Castel S, Wild TC, Strike C, et al. Prevalence of co-occurring substance use and other mental disorders in the Canadian population. Can J Psychiatry Revue Can Psychiatrie. (2008) 53:800–9. doi: 10.1177/070674370805301206

2. Khan S. Concurrent Mental And Substance Use Disorders In Canada. Statistics Canada. (Catalogue no. 82-003-X). (2017). Available online at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-003-x/2017008/article/54853-eng.htm

3. Pearson C, Janz T, Ali J. Mental And Substance Use Disorders In Canada. Statistics Canada. (Catalogue no.82-624-X). (2013). Available online at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/82-624-x/2013001/article/11855-eng.pdf?st=PLGU-QNS

4. Raymond H, Amlung M, De Leo JA, Hashmani T, Younger J, MacKillop J. Adaptation of an acute psychiatric unit to a concurrent disorders unit to increase capacity and improve patient care. Can J Addict. (2016) 7:25–33. doi: 10.1097/02024458-201609000-00004

5. Ti L, Voon P, Dobrer S, Montaner J, Wood E, Kerr T. Denial of pain medication of health care providers predicts in-hospital illicit drug use among individuals who use illicit drugs. Pain Res Manag. (2015) 84:84–8. doi: 10.1155/2015/868746

6. Grewal HK, Ti L, Hayashi K, Dobrer S, Wood E, Kerr T. Illicit drug use in acute care settings. Drug Alcohol Rev. (2015) 34:499–502. doi: 10.1111/dar.12270

7. Carra G, Rcioli R, Monti MC, Marinoni A. Severity profiles of substance-abusing patients in Italian community addiction facilities: influence of psychiatric concurrent disorders. Eur Addict Res. (2006) 12:96–101. doi: 10.1159/000090429

8. Khalifa N, Gibbon S, Duggan C. Police and sniffer dogs in psychiatric settings. Psychiatr Bull. (2008) 32:253–6. doi: 10.1192/pb.bp.107.017483

9. Rachlis BS, Kerr T, Montaner JSG, Wood E. Harm reduction in hospitals: is it time? Harm Reduct J. (2009) 6:1–4. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-6-19

10. Strike C, Robinson S, Guta A, Tan DH, O’Leary B, Cooper C, et al. Illicit drug use while admitted to hospital: patient and health care provider perspectives. PLoS One. (2020) 15:e0229713. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229713

11. Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström K-O. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerström tolerance questionnaire. Br J Addict. (1991) 86:1119–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x

12. Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, De La Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction. (1993) 88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x

13. Adamson SJ, Kay-Lambkin FJ, Baker AL, Lewin TJ, Thornton L, Kelly BJ, et al. An improved brief measure of cannabis misuse: the cannabis use disorders identification test-revised (CUDIT-R). Drug Alcohol Depend. (2010) 110:137–43. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.017

14. Berman A, Bergman H, Palmstierna T, Schlyter F. DUDIT Manual. (2003). Available online at: http://www.paihdelinkki.fi/sites/default/files/duditmanual.pdf (accessed May 1, 2018).

16. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Int Med. (2006) 166:1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

17. Ising HK, Veling W, Loewy RL, Rietveld MW, Rietdijk J, Dragt S, et al. The validity of the 16-item version of the prodromal questionnaire (PQ-16) to screen for ultra high risk of developing psychosis in the general help-seeking population. Schizophr Bull. (2012) 38:1288–96. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs068

18. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. (2005) 15:1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

19. Cope M. Part III “interpreting and communicating” qualitative research. 3rd ed. In: H Iain editor. Qualitative Research Methods In Human Geography. Don Mills, ON: Oxford University Press Canada (2010).

20. Saldana J. An introduction to codes and coding. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications (2009). p. 1–31. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181dd

21. Noyes J, Booth A, Cargo M, Flemming K, Harden A, Harris J, et al. Qualitative evidence. 2nd ed. In: JPT Higgins, J Thomas, J Chandler, M Cumpston, T Li, MJ Page, et al. editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Oxford:Wiley-Blackwell (2019). p. 525–45. doi: 10.1002/9781119536604.ch21

22. Rigotti NA, Arnsten JH, McKool KM, Wood-Reid KM, Pasternak RC, Singer DE. Smoking by patients in a smoke-free hospital: prevalence, predictors, and implications. Prev Med. (2000) 31:159–66. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0695

23. Smoke Free Ontario Act. (S.O.) c. 26, Sched 3.(Can.). (2017). Available online at: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/17s26

24. Regan S, Viana JC, Reyen M, Rigotti N. Prevalence and predictors of smoking by inpatients during a hospital stay. Arch Int Med. (2012) 172:1670–4. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.300

Keywords: concurrent disorders, patient perspectives, contraband substance use, patient substance use, frontline staff perspectives

Citation: Rahman L, Raymond H, Labuguen B, Gladysz H, Holshausen K, Brasch J, Amlung M and MacKillop J (2022) Perceptions of prevalence, consequences, and strategies for managing contraband substance use in an inpatient concurrent disorders program: A qualitative study of patient perspectives and survey of clinician perspectives. Front. Psychiatry 13:911552. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.911552

Received: 02 April 2022; Accepted: 15 August 2022;

Published: 06 September 2022.

Edited by:

Yi-Lang Tang, Emory University, United StatesReviewed by:

Giuseppe Carrà, University of Milano-Bicocca, ItalyPäivi Marjatta Soininen, Helsinki University Central Hospital, Finland

Copyright © 2022 Rahman, Raymond, Labuguen, Gladysz, Holshausen, Brasch, Amlung and MacKillop. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: James MacKillop, jmackill@mcmaster.ca

Liah Rahman

Liah Rahman Holly Raymond2

Holly Raymond2 Michael Amlung

Michael Amlung James MacKillop

James MacKillop