Abstract

Background and objective:

The association between infection and acute ischemic stroke (AIS) with diabetes mellitus (DM) remains unknown. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the effect of infection on AIS with DM.

Materials and methods:

The data of patients with AIS and DM were extracted from the Chinese Stroke Center Alliance (CSCA) database from August 2015 to July 2019. The association between infections [pneumonia or urinary tract infection (UTI)] and in-hospital mortality was analyzed. Logistic regression models were used to identify the risk factors for in-hospital mortality of patients with infection.

Results:

In total, 1,77,923 AIS patients with DM were included in the study. The infection rate during hospitalization was 10.5%, and the mortality rate of infected patients was 3.4%. Stroke-associated infection was an independent risk factor for an early poor functional outcome [odds ratio (OR) = 2.26, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.97–2.34, P < 0.0001] and in-hospital mortality in AIS patients with DM. The in-hospital mortality after infection was associated with age (OR = 1.02, 95% CI: 1.01–1.03, P < 0.0001), male (OR = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.13–1.71, P = 0.0018), reperfusion therapy (OR = 2.00, 95% CI: 1.56–2.56, P < 0.0001), and fasting plasma glucose at admission (OR = 1.05, 95% CI: 1.03–1.08, P < 0.0001). In contrast, antiplatelet drug therapy (OR = 0.63, 95% CI: 0.50–0.78, P < 0.0001) and hospital stay (OR = 0.96, 95% CI: 0.94–0.97, P < 0.0001) were independent protecting factors against in-hospital mortality of patients with infection.

Conclusion:

Infection is an independent risk factor of in-hospital mortality for patients with AIS and DM, and those patients require strengthening nursing management to prevent infection.

Introduction

Stroke is a serious and life-threatening disease and the second leading cause of death in the world (GBD 2019 Stroke Collaborators, 2021). Acute ischemic stroke (AIS) accounts for 62.4% of all stroke cases (GBD 2019 Stroke Collaborators, 2021). A study has shown that up to 9.6% of ischemic stroke (IS) patients developed an infection during hospitalization, with more than 95% of the infections being pneumonia and urinary tract infections (Zonneveld et al., 2017; Westendorp et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2020). Stroke-associated infection is not merely associated with increased mortality and longer hospital stays but is also an independent risk factor for early stroke recurrence (Kwan and Hand, 2007; Rocco et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2020).

According to the China Stroke Statistics 2019, about 23.5% of IS patients had diabetes mellitus (DM; Wang et al., 2020). DM is a common complication of stroke and is also an independent risk factor for IS (Tuttolomondo et al., 2008). Stroke patients with DM generally have a poor prognosis (Szlachetka et al., 2020; Yao et al., 2020). Evidence suggests that DM can increase the risk of pneumonia and urinary tract infection (UTI) in stroke patients (Liao et al., 2015). Admission hyperglycemia is associated with post-stroke infection, even in patients without DM (Zonneveld et al., 2017). A 7-year nationwide prospective research of 5,12,869 adults demonstrated an increased risk of death after infection in DM patients (Bragg et al., 2017). Impaired immune function during hyperglycemia may be involved in the increased susceptibility to infection and mortality in DM patients (Donnelly et al., 2017). In addition, in AIS patients, the activation of inflammatory factors at the infarct location, the immunosuppression induced by stroke, the immune exhaustion after the inflammatory response, and the sympathetic activation further promote immune disorders (Emsley and Hopkins, 2010; Shim and Wong, 2018). Considering the scarcity of epidemiological data on the effects of stroke-associated infection in patients with DM and IS and the increased poor prognosis observed with DM and infection in stroke patients, we suspected that stroke-associated infection during hospitalization might increase the risk of in-hospital mortality in patients with AIS and DM.

Therefore, the study aims to determine the effects of stroke-associated infection on early functional outcomes and in-hospital mortality in patients with AIS and DM and to identify independent risk factors for in-hospital mortality in these patients. The results will elucidate the relationship between stroke-associated infection, the risk of in-hospital mortality, and early poor functional outcomes in patients with AIS and DM, providing clinical evidence for strengthening nursing management.

Materials and methods

Patients

This study used data from a national prospective multicenter registration study, the Chinese Stroke Center Alliance (CSCA). All hospitals participating in the CSCA have received approval to collect data without obtaining individual patient informed consent or a waiver of authorization and exemption from their institutional review board. All procedures in this study conformed to the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research council and the principles of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. A total of 1,77,923 patients diagnosed with AIS and DM from August 1, 2015 to July 31, 2019, were enrolled in the study. The inclusion criteria of our study were as follows: (1) age ≥18 years; (2) diagnosis of AIS confirmed by brain computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging; (3) within 7 days of onset; (4) a previous history of DM. Patients with missing data, including in-hospital mortality, time from symptom onset to admission, or symptom onset beyond 7 days, were excluded. The diagnosis of DM was based on previous clinical medical records.

Infection and baseline characteristics

In the following analyses, stroke-associated infections were defined as pneumonia and UTI in stroke patients during hospitalization (the most common stroke-associated infections), and the relevant data were obtained from discharge records (Davenport et al., 1996). The baseline characteristics included demographic characteristics, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure at admission, personal history, past medical history, medication history, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score, modified Rankin Scale score (mRS), hospital stay, and biochemical data. The range of the NIHSS score is 0–42, with a higher score indicating a more severe neurological deficit (Yoshimura et al., 2022). The range of mRS score is 0–6, with 0 indicating no disability, 6 death and a higher score indicating greater disability (Yoshimura et al., 2022). The NIHSS and mRS scores were rated by a trained professional neurologist and recorded in the inpatient medical records.

Outcome

The primary outcome was all-cause death during hospitalization, i.e., in-hospital mortality. The secondary outcome was the early poor functional outcome, defined as discharge mRS score 3–6 (Boehme et al., 2016).

Statistical analyses

Measurement data were presented as means ± standard deviation (SD) or medians with interquartile ranges (IQR). Enumeration data were presented as numbers and percentages. The Mann–Whitney u-test was used to compare continuous data that did not comply with a normal distribution, while the student’s t-test was used to compare continuous data complying with a normal distribution. The Chi-Squared test was used to compare the proportions of categorical variables. Univariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses were used to estimate the relationship between stroke-associated infection (including total infection, pneumonia, and UTI) and early poor functional outcomes and in-hospital mortality. Univariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses were also used to identify risk factors for in-hospital mortality after infection in patients with AIS and DM. The odds ratio (OR) was presented with the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). A P-value <0.05 (bilateral) was considered statistically significant.

Results

Population characteristics

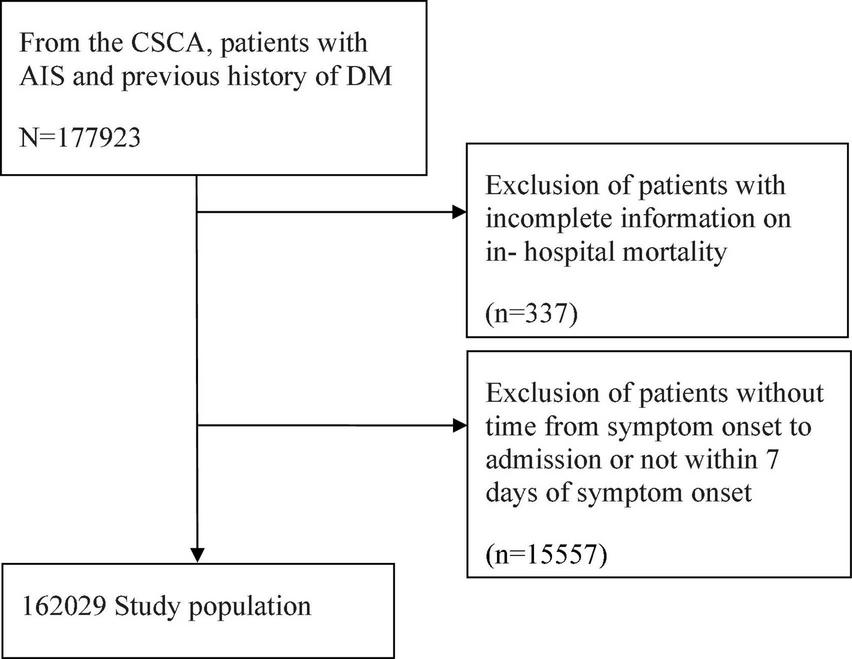

A total of 1,77,923 AIS patients with DM were registered in the CSCA database. However, 337 patients were excluded due to incomplete information on in-hospital mortality, and 15,557 patients were excluded as the time from symptom onset to admission was unavailable or exceeded 7 days from symptom onset. Finally, 1,62,029 patients were included in this study (Figure 1). The median age of all patients was 66 (IQR, 59–74) years, and 92,375 (57%) patients were male. Infection was found in 17,055 (10.5%) of the 1,62,029 patients (Table 1).

FIGURE 1

Flowchart of subject selection. CSCA, Chinese Stroke Center Alliance; AIS, acute ischemic stroke; DM, diabetes mellitus.

TABLE 1

| Variables* | Total (n = 162029, 100%) | Non-infection (n = 144974, 89.5%) | Infection (n = 17055, 10.5%) | P-value |

| Age, years | 66 (59–74) | 66 (58–73) | 72 (64–79) | < 0.0001 |

| Male | 92375 (57.0) | 83477 (57.6) | 8898 (52.2) | < 0.0001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.2 (22.3–26.0) | 24.2 (22.4–26.0) | 23.9 (21.8–26.0) | < 0.0001 |

| SBP, mmHg | 151.3 ± 22.4 | 151.1 ± 22.2 | 152.9 ± 24.3 | < 0.0001 |

| DBP, mmHg | 86.1 ± 13.1 | 86.1 ± 12.9 | 85.7 ± 14.2 | < 0.0001 |

| Previous TIA | 2476 (1.5) | 2179 (1.5) | 297 (1.7) | 0.0164 |

| Previous IS | 61524 (38.0) | 53766 (37.1) | 7758 (45.5) | < 0.0001 |

| Previous ICH | 3811 (2.4) | 3245 (2.2) | 566 (3.3) | < 0.0001 |

| Previous SAH | 443 (0.3) | 376 (0.3) | 67 (0.4) | 0.0016 |

| Previous MI | 4266 (2.6) | 3575 (2.5) | 691 (4.1) | < 0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 123791 (76.4) | 110227 (76.0) | 13564 (79.5) | < 0.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 23581 (14.6) | 20546 (14.2) | 3035 (17.8) | < 0.0001 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 7614 (4.7) | 5584 (3.9) | 2030 (11.9) | < 0.0001 |

| Heart failure | 1959 (1.2) | 1322 (0.9) | 637 (3.7) | < 0.0001 |

| COPD | 1389 (0.9) | 881 (0.6) | 508 (3.0) | < 0.0001 |

| Current smokers | 31724 (19.6) | 29236 (20.2) | 2488 (14.6) | < 0.0001 |

| Alcohol drinkers | 33715 (20.8) | 30786 (21.2) | 2929 (17.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Reperfusion therapy | 11205 (6.9) | 9496 (6.6) | 1709 (10.0) | < 0.0001 |

| Antiplatelet | 138125 (85.2) | 124419 (85.8) | 13706 (80.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Anticoagulation | 7708 (4.8) | 6217 (4.3) | 1491 (8.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Lipid-lowering drug | 11296 (7.0) | 10167 (7.0) | 1129 (6.6) | 0.0565 |

| NIHSS score at admission | 3 (2–6) | 3 (2–6) | 7 (3–14) | < 0.0001 |

| mRS score ≥3 | 29647 (18.3) | 24131 (16.6) | 5516 (32.3) | < 0.0001 |

| Hospital stay, day | 12 (8–14) | 11 (8–14) | 13 (9–19) | < 0.0001 |

| CRP, mg/L | 2.8 (1.0–6.5) | 2.5 (0.9–6.0) | 6.2 (2.0–21.9) | < 0.0001 |

| LDL, mmol/L | 2.7 (2.1–3.4) | 2.7 (2.1–3.4) | 2.6 (2.0–3.4) | < 0.0001 |

| FPG at admission, mmol/L | 8.2 (6.4–10.9) | 8.1 (6.4–10.8) | 8.7 (6.7–11.9) | < 0.0001 |

| HbAlc,% | 7.6 (6.5–9.2) | 7.6 (6.5–9.2) | 7.6 (6.5–9.3) | 0.0602 |

| HCY, mmol/L | 13.0 (10.0–17.6) | 13.0 (9.9–17.5) | 13.4 (10.0–18.4) | < 0.0001 |

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients.

BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; TIA, transient ischemic attacks; IS, ischemic stroke; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; MI, myocardial infarction; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; mRS, modified Rankin Scale score; CRP, C-reactive protein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HbAlc, hemoglobin A1c; HCY, homocysteine. *Continuous variables were expressed as means ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range), and classifying variables were expressed as numbers (percentages).

Stroke-associated infection and early poor functional outcome

Table 1 displays the baseline characteristics of the patients included in the study. The results show that compared with patients without infection, the infected patients were older [median, 72 (IQR, 64–79) vs. 66 (IQR, 58–73), P < 0.0001], had a lower proportion of male patients (52.2 vs. 57.6%, P < 0.0001), had higher admission systolic blood pressure (SBP) (P < 0.0001), had lower BMI (P < 0.0001), had more underlying diseases such as hypertension (P < 0.0001), dyslipidemia (P < 0.0001), atrial fibrillation/flutter (P < 0.0001), heart failure (P < 0.0001), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (P < 0.0001). Furthermore, patients with infection demonstrated higher rates of previous cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, including transient ischemic attacks (TIA) (P = 0.0164), IS (P < 0.0001), intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) (P < 0.0001), subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) (P = 0.00016), and myocardial infarction (MI) (P < 0.0001), and had a higher NIHSS score at admission [median, 7 (IQR, 3–14) vs. 3 (IQR, 2–6), P < 0.0001]. Regarding blood chemical indexes, infected patients had higher levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) [median, 6.2 (IQR, 2.0–21.9) vs. 2.5 (IQR, 2.0–21.9), P < 0.0001], fasting plasma glucose (FPG) at admission [median, 8.7 (IQR, 6.7–11.9) vs. 8.1 (IQR, 6.4–10.8), P < 0.0001], and homocysteine (HCY) (P < 0.0001). In addition, patients with infection were more likely to be treated with reperfusion therapy (10.0 vs. 6.6%, P < 0.0001) and anticoagulation (8.7 vs. 4.3%, P < 0.0001) but less likely to be treated with antiplatelets (80.4 vs. 85.8%, P < 0.0001).

Remarkably, infected patients not only had longer hospital stays [median, 13 (IQR, 9–19) vs. 11 (IQR, 8–14), P < 0.0001) but also had a higher proportion of patients with early poor functional outcome (mRS score ≥3 of hospital discharge) (32.3 vs. 16.6%, P < 0.0001, Table 1). The multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed that stroke-associated infection is an independent risk of early poor functional outcomes in AIS patients with DM (OR = 2.26, 95% CI: 1.97–2.34, P < 0.0001, Table 2). In subgroup analysis, pneumonia (OR = 2.15, 95% CI: 2.06–2.48, P < 0.0001) and UTI (OR = 1.82, 95% CI: 1.50–2.22, P < 0.0001) were independent risk factors.

TABLE 2

| Covariate | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Infection | 4.40 (4.19–4.62) | <0.0001 | 2.15(1.97–2.34) | <0.0001 |

| Pneumonia | 4.82(4.57–5.08) | <0.0001 | 2.26(2.06–2.48) | <0.0001 |

| UTI | 2.76(2.46–3.07) | <0.0001 | 1.82(1.50–2.22) | <0.0001 |

Association between stroke-associated infection and early poor functional outcome.

Adjusted for age, sex, BMI, NIHSS score, SBP, DBP, hypertension, atrial fibrillation/flutter, heart failure, previous TIA, previous IS, previous MI, previous SAH, COPD, antiplatelet, anticoagulation, lipid-lowering drug, reperfusion therapy, smoking, alcohol, LDL, FBG, HbA1c, HCY.

Stroke-associated infection and in-hospital mortality

Table 3 shows the baseline characteristics of the infected patients subgrouped by mortality. Among 17,055 infected patients with AIS and DM, 574 (3.4%) cases resulted in in-hospital death. Compared with patients who survived, the dead patients were older [median, 76 (IQR, 66–82) vs. 72 (IQR, 64–79), P < 0.0001], had a higher proportion of male patients (57.0 vs. 52.0%, P = 0.0193), had higher admission SBP (P < 0.0001), had more underlying diseases, including hypertension (P = 0.0179), atrial fibrillation/flutter (P < 0.0001), and heart failure (P < 0.0001), and had a higher frequency of previous cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, such as IS (P = 0.0137), SAH (P = 0.0110), and MI (P < 0.0001). Moreover, the mortality subgroup demonstrated more severe neurological dysfunctions NIHSS score at admission, [median, 16 (IQR, 10–23) vs. 7 (IQR, 3–13), P < 0.0001]. Regarding blood chemical indexes, the dead patients had higher CRP levels [median, 12.0 (IQR, 3.0–54.9) vs. 6.1 (IQR, 2.0–21.2), P = 0.0033], FPG at admission [median, 10.5 (IQR, 7.8–14.1) vs. 8.6 (IQR, 6.6–11.8), P < 0.0001], and HCY [median, 14.8 (IQR, 10.0–20.7) vs. 13.4 (IQR, 10.0–18.3), P = 0.0052]. Regarding treatment, patients with infection were more likely to be treated with reperfusion therapy (P < 0.0001) but less likely to be treated with antiplatelets (P < 0.0001) and lipid-lowering drugs (P = 0.0264).

TABLE 3

| Variables* | Total (N = 17055, 100%) | Non-death (N = 16481, 96.6%) | Death (N = 574, 3.4%) | P-value |

| Age, years | 72 (64–79) | 72 (64–79) | 76 (66–82) | < 0.0001 |

| Male | 8898 (52.2) | 8571 (52.0) | 327 (57.0) | 0.0193 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.9 (21.8–26.0) | 23.9 (21.8–26.0) | 23.7 (21.5–26.1) | 0.2931 |

| SBP, mmHg | 152.9 ± 24.3 | 152.9 ± 24.2 | 154.5 ± 27.0 | 0.1482 |

| DBP, mmHg | 85.7 ± 14.2 | 85.6 ± 14.1 | 86.2 ± 15.6 | 0.3936 |

| Previous TIA | 297 (1.7) | 287 (1.7) | 10 (1.7) | 0.9989 |

| Previous IS | 7758 (45.5) | 7468 (45.3) | 290 (50.5) | 0.0137 |

| Previous ICH | 566 (3.3) | 546 (3.3) | 20 (3.5) | 0.8217 |

| Previous SAH | 67 (0.4) | 61 (0.4) | 6 (1.0) | 0.0110 |

| Previous MI | 691 (4.1) | 626 (3.8) | 65 (11.3) | < 0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 13564 (79.5) | 13085 (79.4) | 479 (83.4) | 0.0179 |

| Dyslipidemia | 3035 (17.8) | 2932 (17.8) | 103 (17.9) | 0.9244 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 2030 (11.9) | 1867 (11.3) | 163 (28.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Heart failure | 637 (3.7) | 582 (3.5) | 55 (9.6) | < 0.0001 |

| COPD | 508 (3.0) | 485 (2.9) | 23 (4.0) | 0.1404 |

| Current smokers | 2488 (14.6) | 2415 (14.7) | 73 (12.7) | 0.1434 |

| Alcohol drinkers | 2929 (17.2) | 2823 (17.1) | 106 (18.5) | 0.4034 |

| Reperfusion therapy | 1709 (10.0) | 1594 (9.7) | 115 (20.0) | < 0.0001 |

| Antiplatelet | 13706 (80.4) | 13347 (81.0) | 359 (62.5) | < 0.0001 |

| Anticoagulation | 1491 (8.7) | 1432 (8.7) | 59 (10.3) | 0.1849 |

| Lipid-lowering drug | 1129 (6.6) | 1104 (6.7) | 25 (4.4) | 0.0264 |

| NIHSS score at admission | 7 (3–14) | 7 (3–13) | 16 (10–23) | < 0.0001 |

| Hospital stay, day | 13 (9–19) | 14 (9–19) | 7 (3–14) | < 0.0001 |

| CRP, mg/L | 6.2 (2.0–21.9) | 6.1 (2.0–21.2) | 12.0 (3.0–54.9) | 0.0033 |

| LDL, mmol/L | 2.6 (2.0–3.4) | 2.6 (2.0–3.4) | 2.6 (1.8–3.4) | 0.8156 |

| FPG at admission, mmol/L | 8.7 (6.7–11.9) | 8.6 (6.6–11.8) | 10.5 (7.8–14.1) | < 0.0001 |

| HbAlc,% | 7.6 (6.5–9.3) | 7.6 (6.5–9.3) | 7.6 (6.5–9.4) | 0.8192 |

| HCY, mmol/L | 13.4 (10.0–18.4) | 13.4 (10.0–18.3) | 14.8 (10.0–20.7) | 0.0052 |

Demographic and clinical characteristics of infected patients.

BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; TIA, transient ischemic attacks; IS, ischemic stroke; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; MI, myocardial infarction; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; mRS, modified Rankin Scale score; CRP, C-reactive protein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HbAlc, hemoglobin A1c; HCY, homocysteine. *Continuous variables were expressed as means ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range), and classifying variables were expressed as numbers (percentages).

The significant differences in previous SAH (P = 0.0108), hypertension (P = 0.0227), reperfusion therapy (P < 0.0001), lipid-lowering drug therapy (P = 0.0359), antiplatelet therapy (P < 0.0001), hospital stay (P < 0.0001), and CRP (P = 0.0053) between the mortality and survivor groups were mainly observed in patients with pneumonia. In contrast, the significant differences in gender (P = 0.0046), previous TIA (P = 0.0008), and therapy with anticoagulation (P = 0.0053) between the mortality and survivor groups were mainly found in patients with UTI (Table 4).

TABLE 4

| Variables* | Pneumonia |

Urinary tract infection |

||||||

| characteristics | Total (N = 15037) | Non-death (N = 14472, 96.2%) |

Death (N = 565, 3.8%) |

P-value | Total (N = 2,866) | Non-death (N = 2801, 97.7%) |

Death (N = 65, 2.3%) |

P-value |

| Age, years | 72 (64–79) | 72 (64–79) | 76 (66–82) | < 0.0001 | 71(64–78) | 71 (64–78) | 78 (71–82) | 0.0003 |

| Male | 8330 (55.4) | 8006 (55.3) | 324 (57.3) | 0.3422 | 904 (31.5) | 873 (31.2) | 31 (47.7) | 0.0046 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.8 (21.8–25.9) | 23.8 (21.8–25.9) | 23.7 (21.5–26.1) | 0.2750 | 24.0 (21.9–26.3) | 24.0 (21.9–26.3) | 23.9 (20.8–26.6) | 0.1255 |

| SBP, mmHg | 153.0 ± 24.4 | 153.0 ± 24.3 | 154.7 ± 26.8 | 0.1310 | 152.1 ± 24.4 | 152.2 ± 24.3 | 149.0 ± 29.8 | 0.3897 |

| DBP, mmHg | 85.8 ± 14.3 | 85.7 ± 14.2 | 86.3 ± 15.5 | 0.4319 | 84.9 ± 13.7 | 84.9 ± 13.6 | 84.6 ± 19.3 | 0.9054 |

| Previous TIA | 255 (1.7) | 246 (1.7) | 9 (1.6) | 0.8469 | 71 (2.5) | 67 (2.4) | 4 (6.2) | 0.0008 |

| Previous IS | 6803 (45.2) | 6521 (45.1) | 282 (49.9) | 0.0230 | 1436 (50.1) | 1390 (49.6) | 46 (70.8) | 0.1018 |

| Previous ICH | 498 (3.3) | 479 (3.3) | 19 (3.4) | 0.9449 | 110 (3.8) | 105 (3.7) | 5 (7.7) | 0.6127 |

| Previous SAH | 60 (0.4) | 54 (0.4) | 6 (1.1) | 0.0108 | 11 (0.4) | 11 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 0.6127 |

| Previous MI | 632 (4.2) | 568 (3.9) | 64 (11.3) | < 0.0001 | 118 (4.1) | 107 (3.8) | 11 (16.9) | < 0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 11965 (79.6) | 11494 (79.4) | 471 (83.4) | 0.0227 | 2293 (80.0) | 2238 (79.9) | 55 (84.6) | 0.3474 |

| Dyslipidemia | 2678 (17.8) | 2576 (17.8) | 102 (18.1) | 0.8773 | 551 (19.2) | 534 (19.1) | 17 (26.2) | 0.1516 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 1888 (12.6) | 1729 (11.9) | 159 (28.1) | < 0.0001 | 296 (10.3) | 275 (9.8) | 21 (32.3) | < 0.0001 |

| Heart failure | 594 (4.0) | 539 (3.7) | 55 (9.7) | < 0.0001 | 106 (3.7) | 95 (3.4) | 11 (16.9) | < 0.0001 |

| COPD | 487 (3.2) | 464 (3.2) | 23 (4.1) | 0.2547 | 44 (1.5) | 42 (1.5) | 2 (3.1) | 0.3065 |

| Current smokers | 2299 (15.3) | 2226 (15.4) | 73 (12.9) | 0.2044 | 261 (9.1) | 256 (9.1) | 5 (7.7) | 0.8586 |

| Alcohol drinkers | 2713 (18.0) | 2610 (18.0) | 103 (18.2) | 0.9057 | 309 (10.8) | 298 (10.6) | 11 (16.9) | 0.1063 |

| Reperfusion therapy | 1570 (10.4) | 1455 (10.1) | 115 (20.4) | < 0.0001 | 232 (8.1) | 226 (8.1) | 6 (9.2) | 0.7341 |

| Antiplatelet | 11983 (79.7) | 11628 (80.3) | 355 (62.8) | < 0.0001 | 2367 (82.6) | 2318 (82.8) | 49 (75.4) | 0.1213 |

| Anticoagulation | 1370 (9.1) | 1313 (9.1) | 57 (10.1) | 0.4104 | 243 (8.5) | 231 (8.2) | 12 (18.5) | 0.0035 |

| Lipid-lowering drug | 988 (6.6) | 963 (6.7) | 25 (4.4) | 0.0359 | 196 (6.8) | 191 (6.8) | 5 (7.7) | 0.7827 |

| NIHSS score at admission | 8 (4–14) | 8 (3–14) | 16 (10–23) | < 0.0001 | 6 (3–11) | 6 (2–11) | 20 (12–27) | < 0.0001 |

| Hospital stay, day | 13 (9–19) | 14 (9–19) | 7 (3–14) | < 0.0001 | 14 (10–19) | 14 (10–19) | 13 (4–30) | 0.5621 |

| CRP, mg/L | 6.8 (2.1–23.0) | 6.7 (2.1–22.4) | 12.0 (3.0–54.9) | 0.0053 | 5.0 (1.7–19.6) | 5.0 (1.7–18.0) | 30.0 (1.0–57.4) | 0.0855 |

| LDL, mmol/L | 2.6 (2.0–3.4) | 2.6 (2.0–3.4) | 2.6 (1.8–3.4) | 0.9189 | 2.7 (2.0–3.5) | 2.7 (2.0–3.5) | 2.4 (1.5–3.6) | 0.2042 |

| FPG at admission, mmol/L | 8.7 (6.7–11.9) | 8.6 (6.6–11.8) | 10.5 (7.8–14.1) | < 0.0001 | 8.7 (6.6–11.9) | 8.7 (6.6–11.8) | 11.1 (7.9–14.0) | 0.0041 |

| HbAlc, % | 7.6 (6.5–9.3) | 7.6 (6.5–9.2) | 7.6 (6.5–9.4) | 0.5157 | 7.8 (6.5–9.6) | 7.8 (6.5–9.6) | 7.3 (6.5–9.1) | 0.2077 |

| HCY, mmol/L | 13.5 (10.0–18.5) | 13.5 (10.0–18.5) | 15.0 (10.0–20.7) | 0.0078 | 13.1 (9.6–18.0) | 13.0 (9.6–18.0) | 16.1 (12.0–25.0) | 0.0004 |

Clinical features after infection in patients with pneumonia or urinary tract infection.

BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; TIA, transient ischemic attacks; IS, ischemic stroke; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; MI, myocardial infarction; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; CRP, C-reactive protein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HbAlc, hemoglobin A1c; HCY, homocysteine. *Continuous variables were expressed as means ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range), and classifying variables were expressed as numbers (percentages).

Next, the relationship between stroke-associated infection and in-hospital mortality was analyzed. Multiple logistic regression analysis revealed an independent association between stroke-associated infection and in-hospital mortality in AIS patients with DM (OR = 5.22, 95% CI: 3.74–7.28, P < 0.0001). In the subgroup analysis, pneumonia (OR = 5.81, 95% CI: 4.16–8.11, P < 0.0001) and UTI (OR = 2.52, 95% CI: 1.36–4.67, P = 0.0032) were identified as independent risk factors (Table 5).

TABLE 5

| Covariate | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value |

| Infection | 14.56(12.72–16.65) | <0.0001 | 5.22(3.74–7.28) | < 0.0001 |

| Pneumonia | 16.12(14.10–18.43) | <0.0001 | 5.81(4.16–8.11) | < 0.0001 |

| UTI | 4.30(3.33–5.55) | <0.0001 | 2.52(1.36–4.67) | 0.0032 |

Association between post-stroke infection and in-hospital mortality.

Adjusted for age, sex, BMI, NIHSS score, SBP, DBP, hypertension, atrial fibrillation/flutter, heart failure, previous TIA, previous IS, previous MI, previous SAH, COPD, antiplatelet, anticoagulation, lipid-lowering drug, reperfusion therapy, smoking, alcohol, LDL, FBG, HbA1c, HCY. UTI, urinary tract infection.

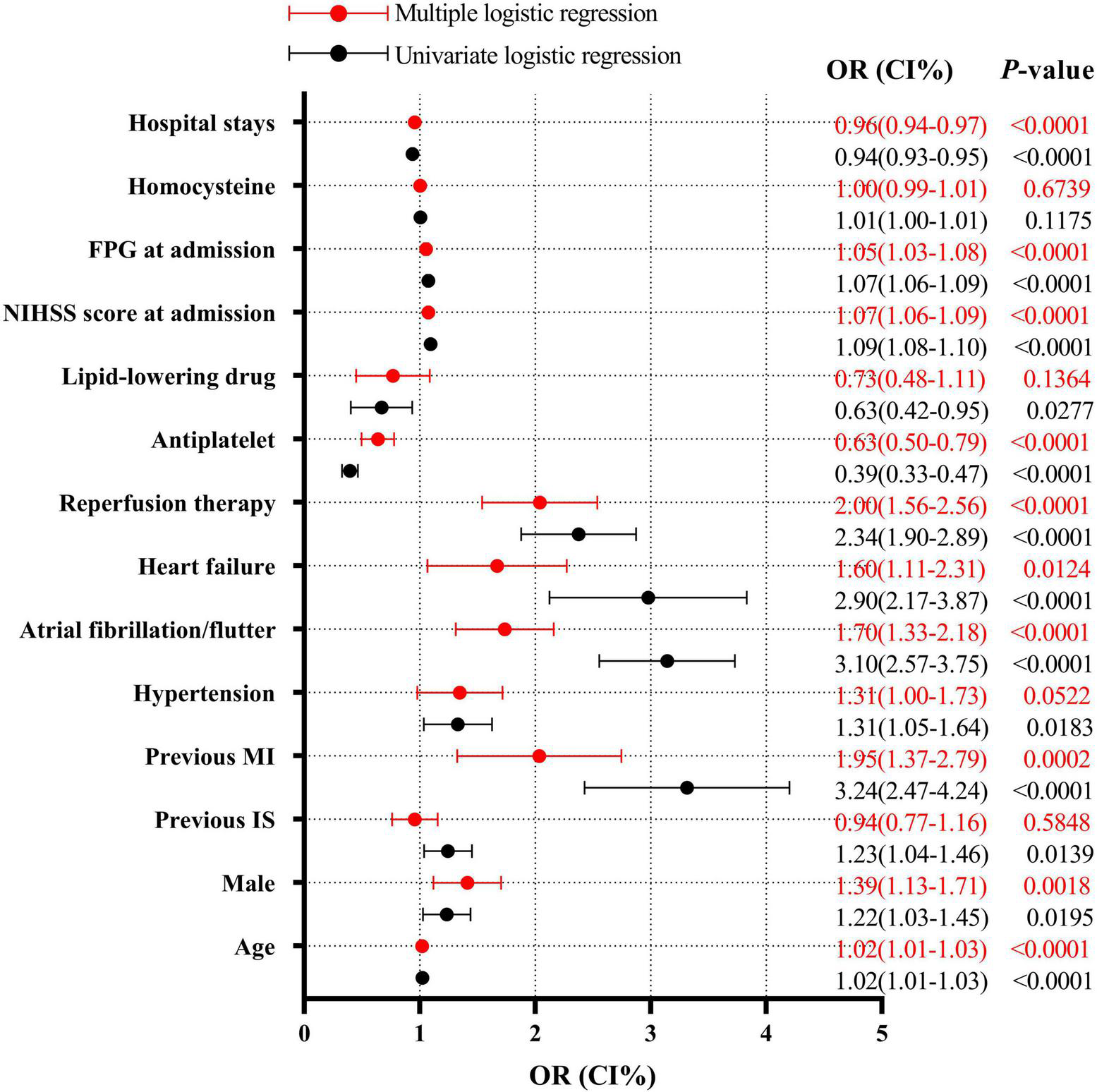

Analysis of risk factors for in-hospital mortality

Further multiple regression analysis indicates that age (OR = 1.02, 95% CI: 1.01–1.03, P < 0.0001), male genderC (OR = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.13–1.71, P = 0.0018), previous MI (OR = 1.95, 95% CI: 1.37–2.78, P = 0.0002), atrial fibrillation/flutter (OR = 1.70, 95% CI: 1.33–2.18, P < 0.0001), heart failure (OR = 1.56, 95% CI: 1.11–2.31, P = 0.0124), reperfusion therapy (OR = 2.00, 95% CI: 1.56–2.56, P < 0.0001), NIHSS score at admission (OR = 1.07, 95% CI: 1.06–1.09, P < 0.0001), and FPG at admission (OR = 1.05, 95% CI: 1.03–1.08, P < 0.0001) were all the independent risk factors of in-hospital mortality in AIS patients with DM and infection. However, antiplatelet drug therapy (OR = 0.63, 95% CI: 0.50–0.78, P < 0.0001) and hospital stay (OR = 0.96, 95% CI: 0.94–0.97, P < 0.0001) were independent protecting factors against in-hospital mortality in AIS patients with DM and infection (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2

Logistic regression analysis for mortality after infection. FPG, fasting plasma glucose; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; MI, myocardial infarction; IS, ischemic stroke.

Discussion

Our study provided solid and convincing evidence for the relationship between stroke-associated infection and patients with AIS and DM. Stroke-associated infection was found in 10.5% of patients with AIS and DM, and the rate of in-hospital mortality in patients with stroke-associated infection was 3.4%. Stroke-associated infection was an independent risk factor of early poor functional outcome and in-hospital mortality in patients with AIS and DM.

Xu et al. (2020) analyzed data from the CSCA database and found that the rate of stroke-associated infection was 9.6%, and the rate of in-hospital mortality in stroke patients with infection was 2.6%, which were all lower than the results of our study. Since our study population included AIS patients with DM, the disparity in results may indicate that DM patients are more likely to suffer from infection after AIS and more likely to die during hospitalization after infection. However, in 2004, data from large German stroke registers showed that post-stroke infections (namely pneumonia) contributed to in-hospital death in up to 31.2% of stroke patients (Heuschmann et al., 2004). In 2009, data from a small sample study in the Netherlands showed that 21% of patients with stroke-associated infection had died in the hospital, and 82% had a poor outcome at discharge (Vermeij et al., 2009). Although the AIS patients in our study were all complicated by DM, the in-hospital mortality of patients with stroke-associated infection was much lower than that of previous studies, which may reflect the gradual improvement of medical care, leading to a decline in mortality in stroke patients with infection.

Our results showed a greater risk of stroke-associated infection in females compared to male patients with AIS and DM, which was consistent with previous studies in AIS patients without DM (Suda et al., 2018). However, further analysis revealed that the patients who died after infection were more likely to be male and that the male gender is an independent risk factor of in-hospital mortality in patients with AIS and DM. Hormones may be responsible for the increased mortality risk. Research showed that estrogen could inhibit inflammation by reducing proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and reducing the cytotoxicity of natural killer cells. In contrast, androgens like testosterone could reduce immunocompetence, leading to decreased resistance to infection (Fish, 2008). Furthermore, studies in animal models have demonstrated a lower incidence and severity of sepsis in females compared to males, which may be attributed to the protective effect of estrogen (Sener et al., 2005; Marriott et al., 2006). However, further study is required to identify the specific mechanism of gender on the risk of in-hospital mortality after infection in patients with AIS and DM.

Various heart-related complications are also important causes of in-hospital mortality in AIS patients with DM after infection. In our study, previous MI was associated with a 1-fold increase, atrial fibrillation/flutter with a 70% increase, and chronic heart failure with a 60% increase of in-hospital mortality in DM patients who suffered from AIS and infection. The results indicated the lethality of the infection for patients with AIS and DM with cardiac diseases. Similar to the results of the current research, previous studies demonstrated that the severity of AIS (i.e., NIHSS score at admission) was independently associated with poor functional outcomes and in-hospital mortality after infection in patients with AIS (Aslanyan et al., 2004; Rocco et al., 2013; Suda et al., 2018).

In our study, elevated FPG at admission was an independent risk factor for in-hospital mortality after infection in AIS patients with DM. Furthermore, hyperglycemia on admission has been reported to be independently associated with poor outcomes and increased risk of death in AIS patients with or without DM (Williams et al., 2002; Kostulas et al., 2009; Poppe et al., 2009). Susceptibility to infection may partially explain the association between admission hyperglycemia and poor outcome of AIS. A large multicenter prospective randomized controlled trial showed that hyperglycemia is predictive of post-stroke infections in patients with AIS (Zonneveld et al., 2017). Moreover, admission hyperglycemia is associated with mortality in a multitude of infectious diseases, such as Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), pneumonia, and central venous catheter-related bloodstream infection (Schuetz et al., 2014; Xie et al., 2020; Mamtani et al., 2021). Hyperglycemia aggravates inflammation and the oxidative stress response by damaging the brain-blood barrier, exacerbating brain edema, increasing apoptosis, disordering the coagulation function, and increasing plasma concentrations of free fatty acids, which may affect stroke outcomes after infection (Song et al., 2003; Yamato et al., 2007; Kruyt et al., 2010; Chiu et al., 2013; Fiorentino et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2022).

Remarkably, our study found that reperfusion therapy can increase the risk of in-hospital mortality in stroke patients with infection, while antiplatelet drug therapy reduces the risk of death. All the subjects included in our study had a history of diabetes, indicating the possibility that DM mediates the association between reperfusion therapy and the heightened risk of in-hospital mortality after infection. On the one hand, DM leads to suboptimal recanalization or hemorrhagic transformation after intravenous thrombolysis (Jiang et al., 2021). On the other hand, the inflammation in patients with infection is further amplified via the expression of cytokines triggered by up-regulated matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), an inflammatory mediator induced by the synergy between DM and tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) (Jiang et al., 2021). Aspirin and clopidogrel, widely used as antiplatelet drugs in the fields of cardiovascular disease and stroke, have been reported to decrease the severity of infection and mortality in patients with sepsis (Gross et al., 2013; Valerio-Rojas et al., 2013). Aspirin plays an anti-inflammatory role by preventing the formation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines and reducing the migration and infiltration of neutrophils (Toner et al., 2015). Clopidogrel mitigates inflammation by antagonizing the P2Y12 receptor, a key factor in systemic inflammation in sepsis (Liverani et al., 2016). Patients who are not treated with antiplatelets generally have contraindications such as serious hemorrhage, and the weak constitution of such patients may be related to higher in-hospital mortality after infection.

Considering the lethality of stroke-associated infection for AIS patients with DM, especially elderly patients or those with many complications, prevention of infection is crucial. The results of two multicenter, randomized, open-label, blinded endpoint design, controlled trials published in The Lancet in 2015 showed that prophylactic antibiotics after AIS did not reduce the incidence of pneumonia and did not improve 3-month functional outcomes (Kalra et al., 2015; Westendorp et al., 2015). In Ulm et al. (2017) conducted a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial in which AIS patients with procalcitonin ultrasensitive (PCTus) >0.05 ng/ml (considered a possible bacterial infection) were treated with prophylactic antibiotics. The results showed no improvement in mRS function and no reduction in mortality at 90 days in the intervention group (Ulm et al., 2017). However, these randomized controlled trials were conducted in patients with AIS, while the patients with AIS and DM exhibited a higher rate of in-hospital mortality after infection. Therefore, these patients may benefit more from prophylactic antibiotic treatment, and further study is necessary to confirm this theory. However, appropriate measures should be taken for each patient to prevent infection regardless of the use of prophylactic antibiotics.

Nevertheless, this study has several limitations. First, stroke-associated infection was based on discharge diagnosis and did not exclude pre-stroke infection, which may bias the results. Second, antibiotic therapy could not be adjusted for due to data unavailability, which might influence the results of early outcomes and in-hospital mortality. Third, as our study population included only Chinese patients, the results might not be applicable to other populations. Finally, we only focused on the short-term effects of infection on AIS patients with DM, while the long-term effects need to be clarified via large-scale prospective studies in the future.

In summary, findings from this study reveal that infection is an independent risk factor of in-hospital mortality for patients with AIS and DM. Those patients require strengthened nursing management to prevent infection.

Statements

Data availability statement

All analysis data are available with permission from the China National Clinical Research Center for Neurological Diseases. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee at Beijing Tiantan Hospital. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the Institutional requirements.

Author contributions

JX, MW, and YD: experimental design. MW, YJ, HG, RT, and DL: data curation. MW: writing—original draft. QinH, FY, XF, and YfL: data interpretation and validation. MW and TZ: visualization. JX and YD: writing—review and editing. JX, ZL, QingH, WG, and YhL: resources. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by the Project Program of National Clinical Research Center for Geriatric Disorders (Xiangya Hospital, Grant No. 2020LNJJ16), the Provincial Key Plan for Research and Development of Hunan (Grant No. 2020SK2067), the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (Grant No. 2021JJ31109), the National Key R&D Programme of China (Grant No. 2017YFC1310901), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 92046016), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of Central South University (Grant No. 2021zzts1029).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participating centers in the Chinese Stroke Center Alliance (CSCA) program for their contribution.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

- AIS

acute ischemic stroke

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- CSCA

Chinese Stroke Center Alliance

- UTI

urinary tract infection

- BMI

body mass index

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- NIHSS

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

- mRS

modified Rankin Scale score

- SD

standard deviation

- IQR

interquartile ranges

- OR

odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

- TIA

transient ischemic attacks

- IS

ischemic stroke

- ICH

intracerebral hemorrhage

- SAH

subarachnoid hemorrhage

- MI

myocardial infarction

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- FPG

fasting plasma glucose

- HCY

homocysteine

- COVID-19

coronavirus disease 2019

- PCTus

procalcitonin ultrasensitive.

References

1

Aslanyan S. Weir C. J. Diener H. C. Kaste M. Lees K. R. Gain International Steering Committee and Investigators (2004). Pneumonia and urinary tract infection after acute ischaemic stroke: a tertiary analysis of the GAIN International trial.Eur. J. Neurol.1149–53. 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2003.00749.x

2

Boehme A. K. Martin-Schild S. Marshall R. S. Lazar R. M. (2016). Effect of aphasia on acute stroke outcomes.Neurology872348–2354. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003297

3

Bragg F. Holmes M. V. Iona A. Guo Y. Du H. Chen Y. et al (2017). Association between diabetes and cause-specific mortality in rural and urban areas of China.JAMA317280–289. 10.1001/jama.2016.19720

4

Chen S. Li L. Peng C. Bian C. Ocak P. E. Zhang J. H. et al (2022). Targeting oxidative stress and inflammatory response for blood-brain barrier protection in intracerebral hemorrhage.Antioxid. Redox Signal.37115–134. 10.1089/ars.2021.0072

5

Chiu C.-D. Chen C.-C. V. Shen C.-C. Chin L. T. Ma H. I. Chuang H. Y. et al (2013). Hyperglycemia exacerbates intracerebral hemorrhage via the downregulation of aquaporin-4: temporal assessment with magnetic resonance imaging.Stroke441682–1689. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.675983

6

Davenport R. J. Dennis M. S. Wellwood I. Warlow C. P. (1996). Complications after acute stroke.Stroke27415–420. 10.1161/01.STR.27.3.415

7

Donnelly J. P. Nair S. Griffin R. Baddley J. W. Safford M. M. Wang H. E. et al (2017). Association of diabetes and insulin therapy with risk of hospitalization for infection and 28-day mortality risk.Clin. Infect. Dis.64435–442.

8

Emsley H. C. A. Hopkins S. J. (2010). Post-stroke immunodepression and infection: an emerging concept.Infect. Disord. Drug Targets1091–97. 10.2174/187152610790963528

9

Fiorentino T. V. Prioletta A. Zuo P. Folli F. (2013). Hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress and its role in diabetes mellitus related cardiovascular diseases.Curr. Pharm. Design195695–5703. 10.2174/1381612811319320005

10

Fish E. N. (2008). The X-files in immunity: sex-based differences predispose immune responses.Nat. Rev. Immunol.8737–744. 10.1038/nri2394

11

GBD 2019 Stroke Collaborators (2021). Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.Lancet Neurol.20795–820.

12

Gross A. K. Dunn S. P. Feola D. J. Martin C. A. Charnigo R. Li Z. et al (2013). Clopidogrel treatment and the incidence and severity of community acquired pneumonia in a cohort study and meta-analysis of antiplatelet therapy in pneumonia and critical illness.J. Thromb. Thromb.35147–154. 10.1007/s11239-012-0833-4

13

Heuschmann P. U. Kolominsky-Rabas P. L. Misselwitz B. Hermanek P. Leffmann C. Janzen R. W. et al (2004). Predictors of in-hospital mortality and attributable risks of death after ischemic stroke: the German Stroke Registers Study Group.Arch. Intern. Med.1641761–1768. 10.1001/archinte.164.16.1761

14

Jiang Y. Liu N. Han J. Li Y. Spencer P. Vodovoz S. J. et al (2021). Diabetes mellitus/poststroke hyperglycemia: a detrimental factor for tpa thrombolytic stroke therapy.Transl. Stroke Res.12416–427. 10.1007/s12975-020-00872-3

15

Kalra L. Irshad S. Hodsoll J. Simpson M. Gulliford M. Smithard D. et al (2015). Prophylactic antibiotics after acute stroke for reducing pneumonia in patients with dysphagia (STROKE-INF): a prospective, cluster-randomised, open-label, masked endpoint, controlled clinical trial.Lancet3861835–1844. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00126-9

16

Kostulas N. Markaki I. Cansu H. Masterman T. Kostulas V. (2009). Hyperglycaemia in acute ischaemic stroke is associated with an increased 5-year mortality.Age Ageing38590–594. 10.1093/ageing/afp120

17

Kruyt N. D. Biessels G. J. Devries J. H. Roos Y. B. (2010). Hyperglycemia in acute ischemic stroke: pathophysiology and clinical management.Nat. Rev. Neurol.6145–155.

18

Kwan J. Hand P. (2007). Infection after acute stroke is associated with poor short-term outcome.Acta Neurol. Scand.115331–338. 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2006.00783.x

19

Liao C.-C. Shih C.-C. Yeh C.-C. Chang Y. C. Hu C. J. Lin J. G. et al (2015). Impact of diabetes on stroke risk and outcomes: two nationwide retrospective cohort studies.Medicine94:e2282. 10.1097/MD.0000000000002282

20

Liverani E. Rico M. C. Tsygankov A. Y. Kilpatrick L. E. Kunapuli S. P. (2016). P2Y12 receptor modulates sepsis-induced inflammation.Arteriosc. Thromb. Vasc. Biol.36961–971. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.307401

21

Mamtani M. Athavale A. M. Abraham M. Vernik J. Amarah A. R. Ruiz J. P. et al (2021). Association of hyperglycaemia with hospital mortality in nondiabetic COVID-19 patients: a cohort study.Diabetes Metab.47:101254.

22

Marriott I. Bost K. L. Huet-Hudson Y. M. (2006). Sexual dimorphism in expression of receptors for bacterial lipopolysaccharides in murine macrophages: a possible mechanism for gender-based differences in endotoxic shock susceptibility.J. Reprod. Immunol.7112–27. 10.1016/j.jri.2006.01.004

23

Poppe A. Y. Majumdar S. R. Jeerakathil T. Ghali W. Buchan A. M. Hill M. D. et al (2009). Admission hyperglycemia predicts a worse outcome in stroke patients treated with intravenous thrombolysis.Diabetes Care32617–622. 10.2337/dc08-1754

24

Rocco A. Fam G. Sykora M. Diedler J. Nagel S. Ringleb P. (2013). Poststroke infections are an independent risk factor for poor functional outcome after three-months in thrombolysed stroke patients.Int. J. Stroke8639–644. 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.00822.x

25

Schuetz P. Friedli N. Grolimund E. Kutz A. Haubitz S. Christ-Crain M. et al (2014). Effect of hyperglycaemia on inflammatory and stress responses and clinical outcome of pneumonia in non-critical-care inpatients: results from an observational cohort study.Diabetologia57275–284. 10.1007/s00125-013-3112-9

26

Sener G. Arbak S. Kurtaran P. Gedik N. Yeðen B. C. (2005). Estrogen protects the liver and intestines against sepsis-induced injury in rats.J. Surg. Res.12870–78. 10.1016/j.jss.2005.02.019

27

Shim R. Wong C. H. Y. (2018). Complex interplay of multiple biological systems that contribute to post-stroke infections.Brain Behav. Immun.7010–20. 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.03.019

28

Song E.-C. Chu K. Jeong S.-W. Jung K. H. Kim S. H. Kim M. et al (2003). Hyperglycemia exacerbates brain edema and perihematomal cell death after intracerebral hemorrhage.Stroke342215–2220. 10.1161/01.STR.0000088060.83709.2C

29

Suda S. Aoki J. Shimoyama T. Suzuki K. Sakamoto Y. Katano T. et al (2018). Stroke-associated infection independently predicts 3-month poor functional outcome and mortality.J. Neurol.265370–375. 10.1007/s00415-017-8714-6

30

Szlachetka W. A. Pana T. A. Tiamkao S. Clark A. B. Kongbunkiat K. Sawanyawisuth K. et al (2020). Impact of diabetes on complications, long term mortality and recurrence in 608,890 hospitalised patients with stroke.Glob. Heart15:2. 10.5334/gh.364

31

Toner P. McAuley D. F. Shyamsundar M. (2015). Aspirin as a potential treatment in sepsis or acute respiratory distress syndrome.Crit. Care19:374.

32

Tuttolomondo A. Pinto A. Salemi G. Di Raimondo D. Di Sciacca R. Fernandez P. et al (2008). Diabetic and non-diabetic subjects with ischemic stroke: differences, subtype distribution and outcome.Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis.18152–157. 10.1016/j.numecd.2007.02.003

33

Ulm L. Hoffmann S. Nabavi D. Hermans M. Mackert B. M. Hamilton F. et al (2017). The randomized controlled STRAWINSKI trial: procalcitonin-guided antibiotic therapy after stroke.Front. Neurol.8:153. 10.3389/fneur.2017.00153

34

Valerio-Rojas J. C. Jaffer I. J. Kor D. J. Gajic O. Cartin-Ceba R. (2013). Outcomes of severe sepsis and septic shock patients on chronic antiplatelet treatment: a historical cohort study.Crit. Care Res. Pract.2013: 2013782573.

35

Vermeij F. H. Scholte op Reimer W. J. M. de Man P. van Oostenbrugge R. J. Franke C. L. de Jong G. et al (2009). Stroke-associated infection is an independent risk factor for poor outcome after acute ischemic stroke: data from the netherlands stroke survey.Cerebrovasc. Dis.27465–471. 10.1159/000210093

36

Wang Y. J. Li Z. X. Gu H. Q. Zhai Y. Jiang Y. Zhao X. Q. et al (2020). China Stroke Statistics 2019: a Report From the National Center for Healthcare Quality Management in Neurological Diseases, China National Clinical Research Center for Neurological Diseases, the Chinese Stroke Association, National Center for Chronic and Non-communicable Disease Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention and Institute for Global Neuroscience and Stroke Collaborations.Stroke Vasc. Neurol.5211–239. 10.1136/svn-2020-000457

37

Westendorp W. F. Vermeij J.-D. Hilkens N. A. Brouwer M. C. Algra A. van der Worp H. B. et al (2018). Development and internal validation of a prediction rule for post-stroke infection and post-stroke pneumonia in acute stroke patients.Eur. Stroke J.3136–144. 10.1177/2396987318764519

38

Westendorp W. F. Vermeij J.-D. Zock E. Hooijenga I. J. Kruyt N. D. Bosboom H. J. et al (2015). The Preventive Antibiotics in Stroke Study (PASS): a pragmatic randomised open-label masked endpoint clinical trial.Lancet3851519–1526. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62456-9

39

Williams L. S. Rotich J. Qi R. Fineberg N. Espay A. Bruno A. et al (2002). Effects of admission hyperglycemia on mortality and costs in acute ischemic stroke.Neurology5967–71. 10.1212/WNL.59.1.67

40

Xie Z. Y. Meng G. L. Xiong Y. Li Y. F. Yang H. Yang Z. L. (2020). [Prognostic factors of central venous catheter-related bloodstream infections].Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao42789–794.

41

Xu J. Yalkun G. Wang M. Wang A. Wangqin R. Zhang X. et al (2020). Impact of infection on the risk of recurrent stroke among patients with acute ischemic stroke.Stroke512395–2403. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.029898

42

Yamato M. Shiba T. Yoshida M. Ide T. Seri N. Kudou W. et al (2007). Fatty acids increase the circulating levels of oxidative stress factors in mice with diet-induced obesity via redox changes of albumin.FEBS J.2743855–3863. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05914.x

43

Yao T. Zhan Y. Shen J. Xu L. Peng B. Cui Q. et al (2020). Association between fasting blood glucose and outcomes and mortality in acute ischaemic stroke patients with diabetes mellitus: a retrospective observational study in Wuhan, China.BMJ Open10:e037291. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037291

44

Yoshimura S. Sakai N. Yamagami H. Uchida K. Beppu M. Toyoda K. et al (2022). Endovascular therapy for acute stroke with a large ischemic region.New Engl. J. Med.3861303–1313. 10.1056/NEJMoa2118191

45

Zonneveld T. P. Nederkoorn P. J. Westendorp W. F. Brouwer M. C. van de Beek D. Kruyt N. D. et al (2017). Hyperglycemia predicts poststroke infections in acute ischemic stroke.Neurology881415–1421. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003811

Summary

Keywords

infection, ischemic stroke, diabetes mellitus, in-hospital mortality, early poor functional outcome

Citation

Wei M, Huang Q, Yu F, Feng X, Luo Y, Zhao T, Tu R, Liao D, Du Y, Huang Q, Gu W, Liu Y, Jiang Y, Gu H, Li Z and Xia J (2022) Stroke-associated infection in patients with co-morbid diabetes mellitus is associated with in-hospital mortality. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14:1024496. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.1024496

Received

01 September 2022

Accepted

02 November 2022

Published

01 December 2022

Volume

14 - 2022

Edited by

Dai-Shi Tian, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, China

Reviewed by

Charles Lo, Australian College of Applied Professions, Australia; Konstantinos Tziomalos, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Wei, Huang, Yu, Feng, Luo, Zhao, Tu, Liao, Du, Huang, Gu, Liu, Jiang, Gu, Li and Xia.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jian Xia, xjian1216@csu.edu.cn

This article was submitted to Neuroinflammation and Neuropathy, a section of the journal Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.