Abstract

Objective:

The aim of this study was to identify and characterize the 100 most cited articles on Parkinson’s disease (PD) and phenolic compounds (PCs).

Methods:

Articles were selected in the Web of Science Core Collection up to June 2022 based on predetermined inclusion criteria, and the following bibliometric parameters were extracted: the number of citations, title, keywords, authors, year, study design, tested PC and therapeutic target. MapChart was used to create worldwide networks, and VOSviewer software was used to create bibliometric networks. Descriptive statistical analysis was used to identify the most researched PCs and therapeutic targets in PD.

Results:

The most cited article was also the oldest. The most recent article was published in 2020. Asia and China were the continent and the country with the most articles in the list (55 and 29%, respectively). In vitro studies were the most common experimental designs among the 100 most cited articles (46%). The most evaluated PC was epigallocatechin. Oxidative stress was the most studied therapeutic target.

Conclusion:

Despite the demonstrations in laboratorial studies, the results obtained point to the need for clinical studies to better elucidate this association.

1. Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is characterized by neurodegeneration and the presence of Lewy bodies, formed by α-synuclein (α-syn) fibrils, in the dopaminergic neurons (DNs) of the pars compacta of the substantia nigra of the brain (Balestrino and Schapira, 2020).

More than 10 million people worldwide are affected by PD. The prevalence of PD is approximately 0.3% in the general population, but this percentage increases to 1 and >4% in adults over 50 and 65 years, respectively (Balestrino and Schapira, 2020). The sum of the prevalences of PD in the 15 most popular nations in the world could reach 9 million people in 2030, approximately double the current prevalence, owing to population aging and advances in the treatment of PD (Dorsey et al., 2007).

The increase in prevalence influences the increase in the costs of the disease (Dorsey et al., 2007). Direct and indirect costs of PD are derived from drug and nondrug treatment, the payment of social security, the loss of productivity and income, hospitalizations, and laboratory tests. In the USA, the cost of the PD reached approximately USD 52 billion per year (Marras et al., 2018) while in Europe, the cost reached EUR 13.9 billion in 2010 (Gustavsson et al., 2011). In Japan, the direct cost per patient was approximately USD 37,994, and the indirect cost was approximately USD 25,356 (Yamabe et al., 2018).

Current drug treatment for symptom reduction or control includes dopaminergic pharmacological targets such as L-dopa; catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibitors; monoamine oxidase type B inhibitors (MAO-BIs); dopamine (DA) agonists; and non-dopaminergic pharmacological targets such as istradefylline, safinamide, clozapine, and amantadine (Poewe et al., 2017).

Unfortunately, the treatment of PD has side effects, such as impulsive and compulsive behaviors, nausea and hallucinations, due to the hyperstimulation of dopaminergic receptors and the serotonergic and cholinergic systems, which results in disturbances in the limbic and frontal cortical structures. In addition to side effects, drug treatment does not prevent disease progression (Connolly and Lang, 2014).

This fact has motivated the search for new substances and the development of neuroprotective drugs that prevent the death of DNs and delay the progression of the disease while causing fewer side effects (Reglodi et al., 2017). Furthermore, investing in treatments that delay disease progression by up to 20% could result in monetary benefits of USD 60,657 per patient (Johnson et al., 2013).

In this context, MAO-BIs (rasagiline and selegiline; Smith et al., 2015), coenzyme Q10 (Flint Beal et al., 2014), creatine monohydrate (Kieburtz et al., 2015), monoclonal antibodies directed against different parts of α-syn (Bergström et al., 2016), tocopherol, vitamin C (Etminan et al., 2005), docosahexaenoic acid (Cieslik et al., 2013) and phenolic compounds (PCs) have been gaining attention through demonstrations of their neuroprotective properties.

PCs are secondary plant metabolites that have at least one hydroxyl linked to an aromatic ring in their chemical structure, and they are synthesized by two metabolic pathways: the shikimate and/or acetate pathways (Cheynier et al., 2013). PCs can be classified according to their chemical structure mainly into flavonoids, phenolic acids, lignans, and stilbenes (Vuolo et al., 2018).

PCs can act on cellular mechanisms that cause DN degeneration through the modulation of gene expression and the activation of antioxidant enzymes regulated by the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NrF2) pathway, thus suggesting great neuroprotective potential for PD (Magalingam et al., 2015; Hussain et al., 2018; Kujawska and Jodynis-Liebert, 2018).

The number of citations is a bibliometric parameter that indirectly indicates quality, impact, productivity and prestige (Baldiotti et al., 2021). Bibliometric analysis makes it possible to identify the most cited articles and, based on that, characterize the scientific production in the area of interest (Karobari et al., 2021). Bibliometric analyses on PD have already been performed (Li et al., 2008; Bala and Gupta, 2013; Robert et al., 2019; Pajo et al., 2020), but the role of PCs has not been addressed.

The identification and characterization of scientific production through bibliometric parameters could contribute to the understanding of the development and direction of research on PD and PCs. Thus, this study aimed to identify and characterize the 100 most cited papers on PCs in PD.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Search strategy and database

The paper search was carried out using the Web of Science Core Collection (WoS-CC). The search terms are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1

| Database | Section |

|---|---|

| Web of Science | Core Collection |

| Search strategy | |

| TS = (“Phenolic compound” OR “phenolic acid” OR “benzoic acid” OR “hydroxycinnamic acid” OR flavonoid OR anthocyanin OR flavanol OR flavonol OR flavanone OR flavone OR isoflavone OR tannin OR coumarin OR lignan OR quinone OR stilben OR curcuminoid OR provinol OR phenol OR polyphenol OR “polyphenolic antioxidant compound”) AND TS = (“Lewy Body” OR Parkinson OR “Parkinson Disease” OR Parkinsonism OR “neurodegenerative disease” OR synuclein) |

Search strategy.

Papers published up to June 2022 were searched with no restriction for language, publication year range, or methodology selection. Two researchers independently selected papers until the 100th most cited paper was found. Disagreements were resolved by the concordance method.

2.2. Data extraction

The articles were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: the words PD or PCs or their synonyms (Table 1) were present in the title and/or abstract and/or keywords, tests were carried out only with PD models, tests were carried out with natural PCs, and pure PCs or the major PCs (in the case of extracts) were identified and quantified. Conference papers and editorial papers were excluded.

The 100 most cited papers list was compiled in descending order based on the number of citations in the WoS-CC. In the event of a tie, the ranking was based on the highest citation density (the number of citations per year).

The article citation count, article title, publication year, study design, names of authors, the continent and country of origin, keywords, tested PC, tested therapeutic target and results of the top 100 most cited articles were recorded. The country of origin was determined by the published corresponding address.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistical analysis of the data extracted as described in the previous section was performed using the number of citations as the main variable. MapChart was used to represent the number of publications by country and continent. Articles were grouped according to the year of publication in 3-year periods.

Study designs were classified as follows: bibliographic studies, laboratory studies (in vitro, in vivo, in situ, and ex vivo) and observational studies. Furthermore, compounds were classified according to the subclass determined in the Phenol Explorer database (Rothwell et al., 2013).

2.4. Quantitative and qualitative analysis

Visualization of Similarities Viewer (VOSviewer) software was used to generate coauthor ship and author keyword co-occurrence cluster maps (van Eck and Waltman, 2010).

The analysis units used were author name in the coauthor ship cluster maps and author keyword in the co-occurrence networks. Author names were linked to each other based on the number of joint authors, and author keywords were linked by occurrence. Units were included when they appeared in at least one of the 100 most cited articles in both networks.

The terms were organized into clusters, with each cluster represented by a color. More important terms had larger circles, and strongly related terms were positioned close to each other. Moreover, lines were drawn between items to indicate relations, with thicker lines indicating a stronger link between 2 items (van Eck and Waltman, 2010).

3. Results

Through the search strategy used (Table 1), 2,273 articles were obtained. After listing the articles in descending order on the basis of the number of citations, 530 articles were screened by the eligibility criteria, of which 420 articles were excluded for not directly addressing PD and/or PCs (the titles of excluded articles can be found in the Supplementary material; Supplementary Table), resulting in the 110 most cited articles on PD and PCs. The 110 most cited articles were ranked from highest to lowest citation number. The first 100 articles were selected to compose the bibliometric analysis (Figure 1). The 100 most cited articles were ranked based on the number and density of citations in WoS-CC. The list of all articles and the data extracted for carrying out the bibliometric analysis are shown in Table 2.

Figure 1

Methodological flowchart of the search, evaluation and selection of the most cited articles on PD and PC. The search for articles was carried out in WoS-CC, the retrieved articles were sorted in descending order based on the citation number in WoS-CC. The articles were evaluated with the eligibility criteria. Articles that did not address only PD and CP were excluded, as well as articles that did not address natural CP. 100 articles were selected and the necessary data for bibliometric analysis were extracted. Data were analyzed quantitatively and qualitatively using descriptive statistics. Software with VosViewer and Mapchart contributed to illustrate the results of the bibliometric analysis.

Table 2

| R | Author (Reference) | Number of citations in the WoS-CC | Study design | Model | Pure compound(s) or extract (#) | Neuroprotective effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Levites et al. (2001) | 434 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | EGCG | Decreased oxidative stress by increasing SOD and CAT activity, preventing DN loss and reducing TH levels |

| 2 | Zhu et al. (2004) | 339 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | Purified human α-syn | Baicalein | Inhibited the formation and disaggregation of α-syn fibrils |

| 3 | Levites et al. (2002a) | 317 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | SH-SY5Y cells | EGCG | Decreased oxidative stress through PKC stimulation and genetic modulation preventing cell death |

| 4 | Zbarsky et al. (2005) | 306 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | Curcumin Naringenin Quercetin Fisetin | Curcumin and naringenin decreased oxidative stress, preventing the reduction of TH positive cells and DA levels |

| 5 | Levites et al. (2002b) | 245 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | SH-SY5Y cells | # | Decreased oxidative stress through inhibition of nuclear translocation and NF-ĸB binding activity |

| 6 | Bureau et al. (2008) | 203 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | Neuronal PC12 cells and Microglial cell line N9 | Resveratrol Quercetin | both prevented cell death by decreasing neuroinflammation |

| 7 | Caruana et al. (2011) | 178 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | Purified human α-syn | 14 natural PCs and BTE | Baicalein, EGCG, myricetin, NDGA and BTE were classified as being the best combined inhibitors and disaggregators of α-syn fibrils |

| 8 | Mercer et al. (2005) | 178 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | Neuronal PC12 cells | Catechin Quercetin Chrysin Puerarin Naringenin Genistein | All attenuated the damage caused by oxidative stress in midbrain NDs. Catechin also reduced oxidative stress damage produced by hydrogen peroxide, 4-hydroxynonenal, rotenone and 6-OHDA |

| 9 | Mythri and Bharath (2012) | 175 | Bibliographic | Curcumin | Acted on oxidative/nitrosative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and protein aggregation | |

| 10 | Khan et al. (2010) | 172 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | Resveratrol | Increased antioxidant status; decreased DA loss; and attenuated the elevated level TBARS, PCa and PLA2 activity |

| 11 | Aquilano et al. (2008) | 170 | Bibliographic | # | Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory agents based on PCs were proposed for the treatment of PD | |

| 12 | Meng et al. (2010) | 164 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | Purified human α-syn | 48 flavonoids belonging to several classes | Eriodictyol, gossypetin, baicalein and 5,6,7,4′-tetrahydroxyflavone bound and stabilized α-syn in its native unfolded conformation |

| 13 | Gao et al. (2012) | 160 | Observational | Prospective cohort study | # | Men with high consumption of foods rich in flavonoids, mainly anthocyanins, were less likely to develop PD during 20–22 years of follow-up |

| 14 | Guo et al. (2005) | 158 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | SH-SY5Y cells | # | Modulated cell death by reducing oxidative stress from ROS sequestration, inhibition of PKC/ERK1/2 and NF-kB pathways, and gene modulation |

| 15 | Pandey et al. (2008) | 156 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | Recombinant wild-type α-syn | Curcumin | Inhibited α-syn fibril aggregation, disaggregated preforms and increased the solubility of α-syn fibrils in cells |

| 16 | Okawara et al. (2007) | 151 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | Organotypic midbrain slice cultures | Resveratrol | Prevented DNs death by decreasing oxidative stress and preventing GSH depletion and increasing propidium iodide uptake |

| 17 | Datla et al. (2001) | 145 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | Tangeretin | Showed evidence of crossing the BBB preventing TH cell loss and striatal DN content by reducing oxidative stress |

| 18 | Li et al. (2004) | 144 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | Microglia purified from rat; SH-SY5Y and Primary Mesencephalic Cultures | EGCG | Decreased neuroinflammation from inhibition of microglial secretion of NO and TNF-α through negative regulation of NO synthase and TNF-α expression |

| 19 | Wruck et al. (2007) | 138 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | PC12 and C6 cells | Luteolin | Decreased oxidative stress through activation of the Nrf-2 pathway |

| 20 | Hong et al. (2008) | 132 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | Purified human α-syn | Baicalein | Oligomers did not form fibrils even after a long time of incubation; they were globular species that were quite compact and extremely stable |

| 21 | Bournival et al. (2009) | 131 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | PC12 cells | Resveratrol Quercetin | Both decreased cell death through the reduction of oxidative stress that occurred from the modulation of the expression of the anti-apoptotic genes Bax and BCL2 |

| 22 | Lou et al. (2014) | 130 | Laboratorial (in vitro and in vivo) | SH-SY5Y cells | Naringenin | Decreased oxidative stress from increased levels of Nrf-2 protein and activation of ARE pathway genes |

| 23 | Guo et al. (2007) | 130 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | # | Decreased oxidative stress, preventing increases in ROS and NO levels, lipid peroxidation, nitrite/nitrate content, inducible iNOS, and protein-bound 3-nitro-tyrosine |

| 24 | Chao et al. (2008) | 125 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | SH-SY5Y cells | Oxyresveratrol | Decreased oxidative stress demonstrated from reduced LDH release, caspase-3 activity, and ROS generation |

| 25 | Zhang Z. et al. (2012) | 122 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | PC12 cells | Baicalein | Increased transcriptional Nrf2/HMOX-1 expression and decreased Keap1, attenuating apoptosis, attenuating oxidative stress |

| 26 | Mu et al. (2009) | 121 | Laboratorial (in vitro and in vivo) | SH-SY5Y and PC12 cells and Rats | Baicalein | Attenuated muscle tremor by reducing oxidative stress, preventing cell death and neurite outgrowth |

| 27 | Karuppagounder et al. (2013) | 120 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | Quercetin | Prevented damage induced by oxidative stress, reduced unilateral rotations, reduced GSH activity, increased CAT and SOD activity, and regulated mitochondrial complex I activity |

| 28 | Lu et al. (2008) | 118 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | Resveratrol | Decreased oxidative stress by attenuating ROS generation, decreasing cell death and reducing motor deficit |

| 29 | Lorenzen et al. (2014) | 117 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | Purified human α-syn | EGCG | Inhibited α-syn fibril toxicity, moderately reduced membrane binding and immobilized the C-terminal tail of the oligomer |

| 30 | Zhang F. et al. (2010) | 117 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | Primary Rat Midbrain Neuron–Glia and Neuron-Astroglia, Microglia-Enriched Cultures | Resveratrol | Inhibited microglial activation and subsequently reduced pro-inflammatory factor release |

| 31 | Zhang et al. (2011) | 113 | Laboratorial (in vitro and in vivo) | PC12 cells and in zebrafish | Quercetin | Inhibited the overproduction of NO and the overexpression of iNOS and downregulated the overexpression of pro-inflammatory genes |

| 32 | Patil et al. (2014) | 111 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | Apigenin Luteolin | Both protected DNs, probably by reducing oxidative stress damage, neuroinflammation and microglial activation and enhancing neurotrophic potential |

| 33 | An et al. (2006) | 111 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | PC12 cells | Protocatechuic acid | Attenuated oxidative stress, increased cell viability and SOD and CAT activity, and decreased cell death |

| 34 | Nie et al. (2002b) | 110 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | PC12 cells | Catechin EGCG Epicatechin EGC Epicatechin gallate | EGCG or epicatechin gallate had greater effects on oxidative stress and led to inhibition of cell death, while other catechins had little effect |

| 35 | Jagatha et al. (2008) | 108 | Laboratorial (in sílico and in vitro) | N27 cells | Curcumin | Prevented cellular damage caused by oxidative stress, restored depleted GSH levels, protected against protein oxidation, and preserved mitochondrial complex I activity |

| 36 | Strathearn et al. (2014) | 105 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | Primary mesencephalic cultures | # | Extracts rich in anthocyanins and proanthocyanidins exhibited greater neuroprotective activity than extracts rich in other PCs |

| 37 | Kim et al. (2010) | 102 | Laboratorial (in vitro and in vivo) | SH-SY5Y and Primary mesencephalic cultures and Rats | # | Decreased oxidative stress from ROS regulation, NO generation, Bcl-2 and Bax proteins, mitochondrial membrane depolarization and caspase-3 activation and prevention of bradykinesia and ND damage |

| 38 | Nie et al. (2002a) | 100 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | PC12 cells | EGCG | Exerted significant protective effects against cell death induced by oxidative stress. EGCG was more effective than the GTP mixture |

| 39 | Zhang et al. (2015) | 98 | Laboratorial (in vitro and in vivo) | PC12 cells and Zebrafish | Protocatechuic acid Chrysin | When used in combination increased neuroprotective effects through a combination of cellular mechanisms of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory cytoprotection |

| 40 | Vauzour et al. (2010) | 98 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | Primary cortical neuron culture | Caffeic acid Tyrosol p-Coumaric acid | All induced neuroprotective effects related to the decrease in oxidative stress more powerful than those observed for flavonoids |

| 41 | Pan et al. (2003b) | 94 | Bibliographic | EGCG | Studies to understand biological activities and health benefits are still very limited. Further studies are needed to assess safety and efficacy in humans and determine neuroprotective mechanisms | |

| 42 | Meng et al. (2009) | 93 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | Wild Type α-Syn and α-Syn Mutants purified | 48 flavonoids belonging to several classes | Baicalein, eriodictoil, and 6-hesperidin were classified as strong inhibitors of α-syn fibrils |

| 43 | Tamilselvam et al. (2013) | 90 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | SK-N-SH cells | Hesperidin | Decreased oxidative stress from attenuation of loss of mitochondrial membrane potential; ROS generation; GSH depletion; improved CAT, SOD and GPx activities; upregulation of Bax, cyt C and caspases 3 and 9; and the downregulation of Bcl-2 |

| 44 | Jimenez-Del-Rio et al. (2010) | 90 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Drosophila melanogaster | Gallic acid Ferulic acid Caffeic acid Coumaric acid Propyl gallate Epicatechin EGC EGCG | The impairment of locomotor activity induced by oxidative stress was significantly recovered, although times of efficacy differed between compounds |

| 45 | Cheng et al. (2008) | 90 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | Baicalein | Inhibited oxidative stress causing increased DA, HVA and 5-HT levels and increased TH-ir neurons |

| 46 | Long et al. (2009) | 89 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Drosophila melanogaster | Resveratrol | Improved oxidative stress-induced damage in climbing ability and lengthening average lifespan |

| 47 | Chen et al. (2008) | 85 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | Primary mesencephalic neuron–glia and microglia-enriched cultures | Luteolin | Attenuated the decrease in DA uptake and loss of TH-ir neurons from inhibition of neuroinflammation by decreasing excessive production of TNF-α, NO and SOD |

| 48 | Liu et al. (2008) | 84 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | Genistein | Prevented DN loss by reducing oxidative stress by increasing the expression of the BCL-2 gene |

| 49 | Molina-Jiménez et al. (2004) | 79 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | SH-SY5Y cells | Fraxetin Myricetin | Both restored the GSH redox ratio and decreased the oxidative stress |

| 50 | Magalingam et al. (2015) | 75 | Bibliographic | # | Gaps were identified in understanding the mechanism why flavonoids protect neuronal cells; few clinical studies showing evidence of the neuroprotection of PCs in patients with PD | |

| 51 | Ye et al. (2012) | 75 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | PC12 cells | EGCG | Increased cell viability by decreasing oxidative stress through increasing mRNA expression of SOD1 and GPX1 and PGC-1α |

| 52 | Anusha et al. (2017) | 73 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | Apigenin | Decreased neuroinflammation through attenuated upregulation of NF-κB gene expression; inhibition of TNF-α, IL-6 and iNOS-1 release; prevented the reduction of mRNA expression of BDNF and GDNF |

| 53 | Cui et al. (2016) | 72 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | Curcumin | Alleviated motor dysfunction induced by oxidative stress, increased TH activity and GSH levels, reduced ROS and MDA content, and restored the expression levels of HMOX-1 and NQO1 |

| 54 | Ardah et al. (2014) | 72 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | Purified human α-syn | Gallic acid | Binds to soluble oligomers with no β-sheet content and stabilized their structure |

| 55 | Bournival et al. (2012) | 72 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | Neuronal PC12 cells and Microglial cell line N9 | Quercetin Sesamin | Both defended against neuroinflammation by preventing increases in IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α mRNA and reduced expression of iNOS and mitochondrial superoxide radicals |

| 56 | Yu et al. (2010) | 72 | Laboratorial (in vitro and in vivo) | SH-SY5Y cells and Rats | Curcumin | Improved behavioral deficits induced by oxidative stress, enhanced the survival of TH+ neurons, inhibited the phosphorylation of JNK1/2 and C-Jun and cleaved caspase-3 |

| 57 | Vauzour et al. (2008) | 71 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | Primary cortical neuron culture | Pelargonidin Quercetin Hesperetin Caffeic acid 4’-O-Me derivatives of Catechin Epicatechin | No effects on oxidative stress were observed with O-methylated flavan-3-ols. Concentrations above 0.3 μM of quercetin were toxic |

| 58 | Chaturvedi et al. (2006) | 71 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | # | Motor and neurochemical deficits induced by oxidative stress improved when BTE was given before 6-OHDA. Increased number of TH-ir neurons, TH protein level and TH mRNA expression in substantia nigra |

| 59 | Zhang Z. T. et al. (2010) | 70 | Laboratorial (in vivo and in vitro) | PC12 cells and Rats | Morin | attenuated behavioral deficits and ND death induced by oxidative stress |

| 60 | Sriraksa et al. (2012) | 68 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | Quercetin | Improved motor deficits induced by oxidative stress; increased DN density; increased SOD, CAT and GPx activity; and decreased AChE activity and MDA levels |

| 61 | Wang et al. (2005) | 68 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | Primary ventral mesencephalic neuron–glia cultures | Genistein | Attenuated neuroinflammation through inhibited microglial activation and the production of TNF-α, NO and superoxide |

| 62 | Kim et al. (2009) | 67 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | SH-SY5Y Cells | Naringin | Blocked JNK and P38 phosphorylation induced by inhibition of mitochondrial complex I, prevented changes in BCL2 and BAX expression, and reduced the activity of caspase 3 and the cleavage of caspase 9 |

| 63 | Chen et al. (2015) | 66 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | Piceid | Attenuated motor deficits induced by oxidative stress; prevented the changes induced in the levels of GSH, thioredoxin, ATP, MDA and SOD in the striatum; and rescued DN degeneration |

| 64 | Liu et al. (2014) | 66 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | A53TαS purified | Gallic acid | Stabilized the extended native structure and interacted with α-syn transiently, inhibiting fibril formation |

| 65 | Zhang Z. J. et al. (2012) | 66 | Laboratorial (in vivo and in vitro) | PC12 cells and Zebrafish | Chrysin | Attenuated neuroinflammation and oxidative stress by decreasing IL-1β and TNF-α gene expression and inhibiting NO production and iNOS expression |

| 66 | Haleagrahara et al. (2011) | 66 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | Quercetin | Increase in DN levels through the attenuation of oxidative stress from the increase in GSH and decrease in the carbonyl protein content |

| 67 | Tapias et al. (2014) | 64 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | # | Increased oxidative stress leading to increased terminal nigrostriatal depression, loss of NDs and increased neuroinflammation from caspase activation |

| 68 | Lee et al. (2014) | 64 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | Baicalein | Reduction of neuroinflammation from the reduction of microglial activations, astrocytes, JNK and ERK; Improves motor skills and prevents the loss of DN |

| 69 | Kim et al. (2012) | 64 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | BV-2 and SH-SY5Y cells | Licochalcone E | Attenuated oxidative stress and neuroinflammation through modulation of the Nrf2-ARE system and upregulated downstream NQO1 and HMOX-1 |

| 70 | Anandhan et al. (2012) | 63 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | Theaflavin | Regulated mitochondrial dysfunction by increasing TH and DA transporter expression and reducing caspase-3, 8, and 9 |

| 71 | Chung et al. (2007) | 62 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | SH-SY5Y cells | EGCG | Potentiated cytotoxicity induced by oxidative stress generated by rotenone |

| 72 | Antunes et al. (2014) | 60 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | Hesperidin | Improved motor and behavioral deficits induced by oxidative stress; attenuated the reduction in GPx and CAT activity and TRAP and DA levels; and mitigated ROS levels and GSH activity |

| 73 | Ay et al. (2017) | 59 | Laboratorial (in vivo and in vitro) | MN9D cell and Rats | Quercetin | Induced the activation of PKD1 and Akt, increased mitochondrial biogenesis, improved behavioral deficits, and increased levels of TH-positive cells and DA |

| 74 | Kavitha et al. (2013) | 58 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | Mangiferin | Prevented behavioral deficits, oxidative stress, apoptosis, dopaminergic neuronal degeneration and DA depletion |

| 75 | Haleagrahara and Ponnusamy (2010) | 58 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | # | Reduced oxidative stress and the protein carbonyl content and increased the levels of SOD, CAT and GPx |

| 76 | Xu et al. (2017) | 57 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | EGCG | Rescued neurotoxicity by decreased oxidative stress; improved DA levels and substantia nigra ferroportin expression |

| 77 | Yabuki et al. (2014) | 57 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | Nobiletin | Rescued Motor and cognitive dysfunction by attenuation of oxidative stress |

| 78 | Roghani et al. (2010) | 57 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | Pelargonidin | Attenuated the rotational behavior, protected the neurons and decreased the oxidative stress |

| 79 | Hou et al. (2008) | 57 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | PC12 cells | EGCG | Attenuated apoptosis, maintaining mitochondrial membrane potential, inhibiting caspase-3 activity and downregulating the expression of SMAC |

| 80 | Ren et al. (2016) | 56 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | Dihydromyricetin | Attenuated behavioral impairments and ND loss, cell damage and ROS production induced by oxidative stress; increased phosphorylation of GSK-3 β |

| 81 | Zhu et al. (2013) | 56 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | Human wild-type α-syn | Quercetin Oxyquercetin | Oxidized quercetin species were stronger inhibitors of α-syn fibrils than quercetin |

| 82 | Molina-Jimenez et al. (2003) | 56 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | SH-SY5Y cells | Fraxetin Myricetin | Significantly decreased cytotoxicity generated by rotenone-induced oxidative stress, as well as LDH release, through the effect of fraxetine |

| 83 | Goes et al. (2018) | 55 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | Chrysin | Prevented behavioral changes; Modulated neuroinflammation through increased levels of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6 and NF-ĸB; and decreased levels of IL-10, DA, DOPAC, HVA and TH and TRAP |

| 84 | Cao et al. (2017) | 54 | Laboratorial (in vivo and in vitro) | SHSY5Y cells and Rats | Amentoflavone | Rescued DN loss; increased PI3K and Akt activation and the Bcl-2/Bax ratio; attenuated neuroinflammation through alleviated gliosis and levels of IL-1β and iNOS gene expression |

| 85 | Khan et al. (2013) | 54 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | Pycnogenol | Decreased stress oxidative; restored GSH levels and the activities of GPx, GSH and SOD; inhibited the expression of NF-ĸB and attenuated neuroinflammation through the release of COX-2, iNOS, TNF-α and IL-1β |

| 86 | Brunetti et al. (2020) | 53 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Caenorhabditis elegans | Hydroxytirosol Oleuropein aglycone | Increased the survival after heat stress oxidative, but only hydroxytirosol could prolong the lifespan in unstressed conditions |

| 87 | Wu et al. (2015) | 53 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | BV-2 cells | Biochanin A | Decreased neuroinflammation through attenuated the mRNA expression of TNF-α and IL-1β; inhibited iNOS mRNA and protein expression and the phosphorylation of JNK, ERK and P38 |

| 88 | Pan et al. (2003a) | 53 | Laboratorial (in vivo and in vitro) | Primary culture of embryonic mesencephalic and primary mensencephalic cells | # | Significantly attenuated the loss of TH-positive cells induced by mitochondrial dysfunction |

| 89 | Leem et al. (2014) | 52 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | Naringin | Increased GDNF levels in DA neurons, activated the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1, and attenuated neuroinflammation by decreasing the level of TNF-α in microglia |

| 90 | Du et al. (2012) | 52 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | Curcumin | Prevented the decrease in the levels of DA and DOPAC and inhibited the decrease in TH + neurons and the numbers of iron + cells induced by oxidative stress |

| 91 | Xu et al. (2016) | 51 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | Synthetic α-syn | EGCG | Inhibited α-syn fibril aggregation through unstable hydrophobic bonds |

| 92 | Subramaniam and Ellis (2013) | 51 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | Umbelliferone Esculetin | Both significantly attenuated oxidative stress y in the substantia nigra pars compacta but not the striatum, prevented the increase in nitrosative stress and prevented caspase 3 activation but inhibited MAO activity |

| 93 | Kang et al. (2010) | 51 | Laboratorial (in vivo and in vitro) | HT22 hippocampal neuronal cells and Rats | EGCG | Inhibited the O-methylation of L-dopa and moderately reduced the accumulation of 3-O-methyldopa in plasma and striatum decreasing oxidative stress |

| 94 | Guan et al. (2006) | 51 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | PC12 cells | Protocatechuic acid | Prevented the formation of ROS, GSH depletion and the activation of caspase-3 and upregulatedBcl-2 induced by mitochondrial dysfunction |

| 95 | Jiang et al. (2010) | 50 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | E46K α-syn | Baicalein | Attenuated mitochondrial depolarization and proteasome inhibition and protected cells from toxicity as well as reduced α-syn fibrillation |

| 96 | Kujawska and Jodynis-Liebert (2018) | 49 | Bibliographic | # | Analyzed studies encouraged the search for phytochemicals exerting neuroprotective effects on DA neurons, and delaying their degeneration was found to be highly desirable | |

| 97 | Macedo et al. (2015) | 49 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | Synthetic α-syn | Myricetin | Inhibited α-syn toxicity and aggregation in cells |

| 98 | Li et al. (2012) | 49 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | PC12 cells and rat brain mitochondria | Baicalein | Attenuated oxidative stress, suppressed apoptosis, inhibited the accumulation of ROS, alleviated ATP deficiency, and acted in mitochondrial membrane potential dissipation and caspase-3/7 activation |

| 99 | Park et al. (2008) | 49 | Laboratorial (in vitro) | SN4741 cells | Carnosic acid | Inhibited oxidative stress by preventing caspase-3 activation, JNK phosphorylation, and caspase-12 activation |

| 100 | Datla et al. (2007) | 49 | Laboratorial (in vivo) | Rats | Tangeritin Nobiletin Catechin Epicatechin Epicatechin gallate Formononetin Genistein | Pretreatment with plant extracts rich in catechins had no effect on oxidative stress of nigrostriatal NDs |

The 100 most cited articles on Parkinson’s disease and phenolic compounds.

R = ranking.

3.1. Oldest, newest and most cited article

The article “Green tea polyphenol (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate prevents N-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced dopaminergic neurodegeneration. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2001 Sep; 78 (Yamabe et al., 2018): 1073–1082” is the most cited (434 citations) and the oldest on the top 100 list in the WoS-CC.

Additionally, on the same criteria, the most recent article on the list is “Healthspan Maintenance and Prevention of Parkinson’s-like Phenotypes with Hydroxytyrosol and Oleuropein Aglycone in C. elegans. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2020, 21,” with 53 citations.

3.2. Authors who contributed to the 100 most cited articles

The top 100 most cited articles were contributed by 497 authors forming 66 clusters (Figure 2). The major contribution with number of paper was made by a Fink, A. L. (n = 5) followed by Lee, S. M. Y.; Zhang, Z. J.; Zhao, B. L. (n = 4), followed by Datla, K. P.; Dexter, D. T.; Du, G. H.; Essa, M. M.; Haleagrahara, N.; He, G. R.; Le, W. D.; Levites, Y.; Li, G. H.; Li, X. X.; Mandel, S.; Manivasagam, T.; Martinoli, M. G.; Mu, X.; Uversky, V. N.; Xu, B.; Youdim, M. B. H. (n = 3). The other authors contributed ≤2 papers.

Figure 2

VOSviewer co-authorship map demonstrating the bibliographic coupling between the 497 authors of the 100 most cited articles on PD and PCs. The authors form 66 clusters. The cluster size represents the frequency of publications. The color scale represents the period in which the publications occurred. Overlapping nodes does not allow viewing the name of all authors who contributed to the 100 most cited articles. Authors with the highest number of publications are superimposed on authors with the lowest number of publications.

The cluster with the most authors is formed by Lee, S. M. Y. and more 19 researchers. Collaborations carried out in 2012 produced more articles, as can be seen by the thickness of the lines between authors who are present in that period of time, for example Lee, S. M.Y. and Zhang, Z. J. Figure 3A in addition, these authors received more citations, as can be seen in the heat map (Figure 3B).

Figure 3

The cluster with the highest number of publications. (A) The cluster is composed of 20 authors. The period of publication of the cluster’s papers is indicated by the color scale that varies from blue (2012) to yellow (2015). The node size represents the citation number of each author. The authors who collaborated in publications that occurred between the years 2012–2013 have higher numbers of citations compared to the authors who collaborated with publications that occurred between the years 2014–2015. The number of citations contributes to the strength of the connection between the authors represented by the distance between the authors. Authors with higher numbers of citations have higher binding strength. This representation suggests that the articles published by the cluster in the period 2012–2013 have higher numbers of citations. (B) The authors who make up the cluster with the highest number of publications are represented by heat islands demonstrating the citation density (number of citations/year of publication). The size of the heat island corresponds to the citation density. Authors with high citation density are closer, suggesting that publications that occurred in collaboration between them have higher numbers of citations.

3.3. Global distribution of the 100 most cited articles

The list of the 100 most cited articles of WoS-CC has more articles from the Asian (55%) and North America (23%) continents. China is the country with the most articles and most citations on the list. In addition to China, countries like the USA, India and South Korea also have high numbers of articles on the list. The Asian continent has more countries with articles on the list compared to other continents. Africa and Central America are the only continent that does not have countries with articles on the list (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Worldwide distribution of the 100 most cited articles in PD and PC. Countries from the same continent are represented by the same color. The intensity of the color varies according to the presence or absence of publications with a high number of citations on PD and CP by country. Countries with stronger color intensity have publications with a high number of citations on PD and PC.

3.4. Distribution of the 100 most cited articles by journals, periods, and experimental design

Brain Research Journal has the highest number of articles in the list (5 articles). The journals Free Radical Biology and Medicine and Journal of Neuroscience Research presented four articles. The other journals that are part of the list have less than three articles (Table 3).

Table 3

| Characteristics | n papers | n citationsa |

|---|---|---|

| Journal (at least 4 papers) | ||

| Brain Research Journal | 5 | 481 |

| Free Radical Biology and Medicine | 4 | 489 |

| Journal of Neuroscience Research | 4 | 462 |

| Period of publications | ||

| 2021–2019 | 1 | 53 |

| 2018–2016 | 9 | 526 |

| 2015–2013 | 22 | 3,681 |

| 2012–2010 | 26 | 2,249 |

| 2009–2007 | 23 | 2,479 |

| 2006–2004 | 10 | 1,505 |

| 2003–2001 | 9 | 1,554 |

| Study design | ||

| Bibliographic studies | 5 | 563 |

| Observational studies | 1 | 160 |

| Laboratorial studies | ||

| in vitro + in vivo | 14 | 1,134 |

| in vitro + in silico | 1 | 2,008 |

| in vivo | 32 | 3,120 |

| in vitro | 47 | 5,124 |

Frequencies of characteristics of the 100 most-cited papers in PD and PC.

Citation count (Web of Science Core Collection).

The most prolific periods in terms of publications on list of the 100 most cited articles of WoS-CC were 2012–2010 (26 publications), 2009–2007 (23 publications), and 2015–2013 (22 publications) respectively (Table 3). On the other hand, the period with most papers citations was 2015–2013 (3,681 citations), followed by 2009–2007 (2,479) and 2012–2010 (2,249).

The most used PD models were in vitro (47 papers), in vivo (32 papers) and in vitro + in vivo (14 papers) study designs, totaling the largest number of citations (5,124, 3,120, and 1,134 respectively; Table 3). Other study designs like bibliographic studies that did not have the type of review determined (5 papers), observational study (cross-sectional; 01 paper) and in vitro + in silico (01 paper) had a low occurrence on the top 100 list in the WoS-CC (Table 3).

3.5. Most evaluated compounds, subclasses and therapeutic targets among the 100 most cited articles

The compounds EGCG, quercetin, curcumin e baicalein are the most discussed (19, 15, 9, and 9 papers respectively) in the top 100 list in the WoS-CC, totaling the largest number of citations (2,394, 1,798, 1,183, and 1,060 respectively). The subclasses flavanol, flavones and flavonol are the most discussed (27, 22, and 21 papers respectively) in the top 100 list in the WoS-CC, totaling the largest number of citations (3,354, 2,434, and 2,444, respectively; Table 4).

Table 4

| Compound | n papers | n citationsa |

|---|---|---|

| EGCG | 19 | 2,394 |

| Quercetin | 15 | 1798 |

| Curcumin | 9 | 1,183 |

| Baicalein | 9 | 1,060 |

| Resveratrol | 7 | 981 |

| Epicatechin | 5 | 480 |

| Chrysin | 4 | 397 |

| Genistein | 4 | 379 |

| Catechin | 4 | 323 |

| Naringenin | 3 | 614 |

| Luteolin | 3 | 334 |

| Theaflavin | 3 | 312 |

| Pelargonidin | 3 | 288 |

| Protocatecuic acid | 3 | 260 |

| Caffeic acid | 3 | 259 |

| Gallic acid | 3 | 228 |

| Epigallocatechin | 2 | 200 |

| Tangeritin | 2 | 194 |

| Apigenin | 2 | 184 |

| Epicatechin gallate | 2 | 159 |

| Fraxetin | 2 | 135 |

| Hesperetin | 2 | 131 |

| Myricetin | 2 | 128 |

| Naringin | 2 | 119 |

| Nobiletin | 2 | 106 |

| Subclasses | ||

| Flavanol | 27 | 3,354 |

| Flavone | 22 | 2,434 |

| Flavonol | 21 | 2,444 |

| Stilbene | 11 | 1,455 |

| Curcuminoids | 9 | 1,183 |

| Benzoic acids | 9 | 869 |

| Flavanone | 7 | 976 |

| Isoflavone | 7 | 774 |

| Anthocyanin | 5 | 495 |

| Hydroxycinamic acids | 5 | 542 |

| Proanthocyanidin | 4 | 394 |

| Coumarin | 3 | 186 |

| Lignan | 1 | 178 |

| Xanthone | 1 | 58 |

| Flavanonol | 1 | 56 |

| Therapeutic targets | ||

| Oxidative stress | 68 | 7,183 |

| Neuroinflammation | 20 | 1,821 |

| Fibrils of α-syn | 15 | 1,773 |

| Mitochondrial dysfunction | 8 | 489 |

Number of articles published by phenolic compounds, subclasses and therapeutic target.

Citation count (Web of Science Core Collection).

The most discussed targeted PD therapy on the WoS-CC Top 100 list was oxidative stress (68 articles), followed by neuroinflammation (20 articles), α-syn fibrils (15 articles) and mitochondrial dysfunction (8 articles; Table 4). However, evaluating the citation ratio it is evident that α-syn fibrils have the highest citation rate per article followed by oxidative stress, neuroinflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction (Table 4).

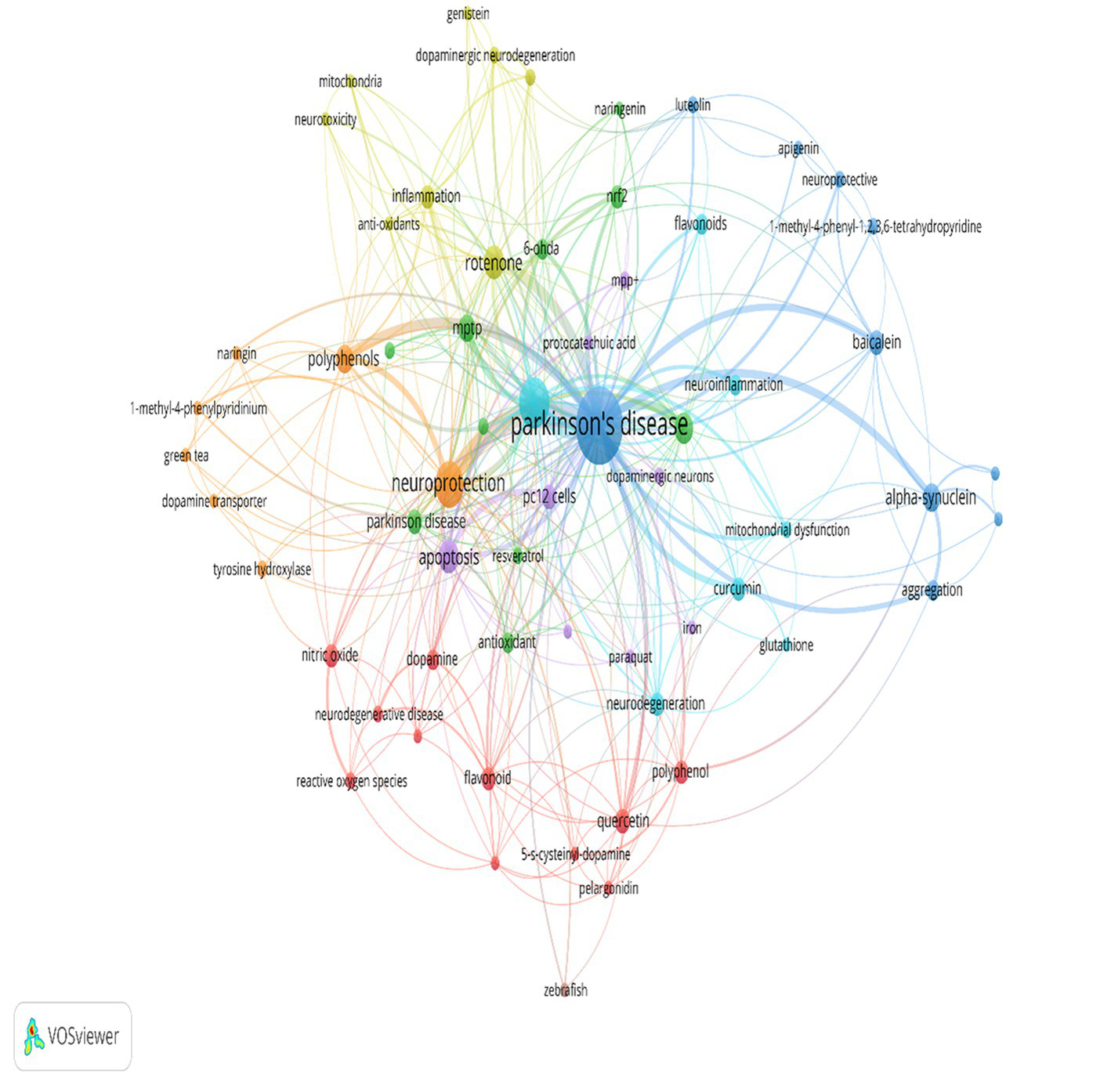

3.6. Keywords that occurred in the 100 most cited articles

Out of the top 100 most-cited publications, only 82 articles contained author keywords. The keywords that occurred in at least two articles were presented in Figure 5. The most frequently used keyword was parkinson’s disease (n = 54), followed by neuroprotection (n = 20), apoptosis (n = 11), rotenone (n = 11), 6-OHDA (n = 9), 11 alpha-synuclein (n = 8), polyphenols (n = 8). A total of 214 author keywords were identified.

Figure 5

Author keyword network analysis with 2 or more occurrences. The node size represents the frequency of the author keyword with larger nodes indicating greater frequency. The color of the node represents the possibility of co-occurrence of author keywords among the 100 most cited articles on PD and PC with nodes of the same color demonstrating that there is co-occurrence between author keywords in the same article. The thickness of the line between nodes represents the strength of linkage between author keywords with strong linkage strengths being demonstrated by thicker lines. More frequent author keywords have stronger linking strength.

4. Discussion

From the list of the 100 most cited articles on PD and PCs, the oldest article published in 2001, which also has the highest number of citations and the most recent article published in 2020, was identified. Asia and China were the continent and the country with the highest number of papers on the list. The period with the highest number of articles published was between 2012 and 2010 and the most common experimental design was laboratory studies, especially in vitro studies. The compounds EGCG, quercetin, curcumin andbaicalein were the most evaluated compounds and oxidative stress was the most therapeutic target among the papers.

The number of citations indicates the quality of an article according to the scientific community (Fardi et al., 2017). Articles with more than 100 citations are recognized as classics depending on the research area. Classic articles influence research and scientific practice (Arshad et al., 2020). In the list of the 100 most cited, 38 articles received more than 100 citations and can be called classics. The other articles received at least 49 citations.

Older articles tend to accumulate citations over time, then become references, as is the case of the most cited article (n citation = 434) in the list that was published in 2001. More recent articles, despite having lower numbers of citations, present new research possibilities within the area of interest (Feijoo et al., 2014). The most recent article on the list demonstrates that the mechanism involved in neuroprotection against PD may also occur due to the anti-inflammatory potential of PCs through the regulation of cytokines and neurotrophic factors (Brunetti et al., 2020).

Author Lee, S. M. Y. leads the cluster with the highest number of research (n = 20) in addition to having greater link strength (total link strength = 30), although he is not the author with the highest number of citations (n citation = 399). He is a professor and deputy director of the Institute of Chinese Medical Sciences at the University of Macau. He is interested in natural products that can be used as therapeutic agents in brain disorders. His dedication to education and research in the fields of molecular biochemistry biology, pharmacology pharmacy and neuroscience neurology.

PD is the second neurodegenerative disease with the highest incidence in the world. Its prevalence is higher in Anglo-Saxon America and Europe compared to Asia, Latin America and Africa (Benito-León and Louis, 2013). Despite the fact that the Asian continent has a low prevalence of the disease, it was the one that published the most articles on PD and PCs. The research on PD has increased 33-fold in the last 35 years in the Asian continent. This increase may be related to population aging and the new phase of economic development based on the production, communication and consumption of knowledge (Pajo et al., 2020).

China was the country with the most articles and the most citations in the list. In addition to China, countries such as the USA, India and South Korea also had high numbers of articles in the list. The high scientific production on PD and PCs may be related to traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), which has lower costs than Western medicine and more than 170 ingredients for the treatment of the disease, including PCs. The benefits and molecular mechanisms of TCM have been evaluated in preclinical studies, which may lead to the discovery of new therapeutic candidates for the treatment of PD (Li and Le, 2021).

In addition, China already stood out in scientific production on PD between 2013 and 2017, publishing 3,986 articles, behind only the USA. The high number of publications in this period was related to the standardization through guidelines (Chen et al., 2016) on the management of the disease in the country, efforts to reduce the economic burden related to the treatment of the disease and government incentives for publication in English newspapers (Robert et al., 2019).

The number of citations an article receives also contributes to the impact factor that determines the academic prestige of scientific journals. This factor in the year 2020 depended on the sum of the number of citations of early access articles with an early access year in 2020, early access articles with a final publication year in 2020 and an early access year in 2019 or earlier, and unanticipated access articles with a final publication year in 2020 divided by the sum of the number of articles published in the year of evaluation and in the year prior to the evaluation. Thus, journals that have articles with a high number of citations do not necessarily have a high impact factor, as is the case of the 3 three journals with the highest number of articles in the list.

The level of evidence of research is related to the experimental design. According to evidence-based practice systematic reviews and clinical studies are considered more important. As seen, in vitro laboratory studies are the most common experimental designs among the 100 articles. The development of these preliminary studies is necessary to carry out an initial screening regarding the effective concentration for bioactivity and toxicity (Ferreira et al., 2017). However, the concentrations evaluated in laboratory studies are not representative of the concentrations and chemical structure that reach the target organ (Perdigão et al., 2023).

After consumption, PCs can be hydrolyzed by intestinal enzymes, but most reach the colon, where they undergo hydrolysis and biotransformation reactions by microbiota enzymes and are then absorbed. Metabolites undergo conjugation reactions in the liver before entering the brain. The penetration of metabolites into the brain depends on the ability to bind to brain efflux transporters present in the blood–brain barrier and on lipophilicity. Metabolites reach the brain at concentrations less than 1 nmol/g of brain tissue (Pandareesh et al., 2015).

More than 10,000 PCs have been identified, of which approximately 500 are dietary compounds (Vuolo et al., 2018). The number of compounds that occurred among the 100 most cited articles (n = 51) is not representative of the amount of dietary phenolic compounds, however the compounds EGCG, quercetin, curcumin and baicalein were the most evaluated among the papers (19, 15, 9, and 9 papers, respectively), with the highest number of citations (2,394, 1,798, 1,183, and 1,060, respectively).

EGCG, the most evaluated compound in the list, can be found abundantly in green tea leaves, oolong tea, and black tea leaves (Eng et al., 2018). The estimated daily intake of EGCG through green tea consumption can reach approximately 560 mg/day for individuals consuming an average of 750 ml/day of green tea (Hu et al., 2018). Green tea is among the foods that are prescribed for the prevention of PD in TCM (Li and Le, 2021).

Quercetin, curcumin and baicalein compounds were widely evaluated among the papers as well. Quercetin is mostly conjugated to sugar moieties such as glucose or rutinose and can be found in high concentrations in Ginkgo Biloba, a TCM herb, onion, lettuce, chili pepper, cranberry, tomato, broccoli and apple, which contribute to an estimated dietary intake of 6–18 mg/day in the USA, China and the Netherlands (Ishisaka et al., 2011; Guo and Bruno, 2015).

The compound curcumin is extracted from turmeric and is widely used in Asian medicine to treat respiratory and liver diseases and inflammation. The pharmacological activities of curcumin include anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antioxidant, among others. Strategies such as nanoencapsulation, liposomes, micelles are being developed to increase bioavailability (Zhenqi et al., 2020).

Baicalein can be found in the root of Scutellaria baicalensis, an east Asian plant widely used in TCM to treat diseases (Arredondo et al., 2015). Baicalein has low water solubility for this reason, and it is poorly bioavailable, which makes its application in neuroprotectiv therapies difficult (Zhang et al., 2020). PCs, despite having common structural elements, have structural characteristics such as their degree of oxidation and substituents (position, number and nature of groups attached to rings A and B and the presence of glycosidic bonds) that affect their bioactive potential (Castillo et al., 2000). The subclasses flavanol, flavones, and flavonol were the most discussed (27, 22, and 21 papers, respectively) in the top 100 list in the WoS-CC, with the highest number of citations (3,547, 2,434, and 2,444, respectively; Table 4).

Flavanols, the most evaluated subclass among the 100 articles, present the ortho-dihydroxy (catecholic) group in the B ring, providing the delocalization of electrons, which contributes to a high antioxidant activity, which may be related to the number of studies that evaluated PCs and their effects on oxidative stress as a therapeutic target (Latos-Brozio and Masek, 2019).

The most discussed targeted PD therapy in the WoS-CC top 100 list was oxidative stress (68 articles). The interest in the mechanism used by PCs to reduce intracellular levels of ROS is recent, although the demonstration of the antioxidant potential of PCs in neurons is not (Reglodi et al., 2017). The search for answers makes this therapeutic target the most studied through laboratory models that are important tools, as they provide insights into behavioral improvements in parallel with the improvement in the oxidative state after exposure to PCs, for example, modulating the Nrf-2 signaling pathway and inducing increased expression of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD, CAT, and GSH (Table 2).

Other therapeutic targets for PCs in PD demonstrated in the 100 most cited articles were neuroinflammation (20 articles), α-syn fibrils (15 articles) and mitochondrial dysfunction (8 articles; Table 4). The neuroprotective effects of PCs include reduced expression of cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1b, and COX-2; the breakdown and inhibition of the formation of α-syn fibrils; and the upregulation of complex I activity in the mitochondria (Table 2).

Keywords are essential for discovering scientific articles. They are used as codes to access literature in a particular area. When using keywords in the search, you get more relevant results compared to using a phrase. Despite its importance, there are articles that do not bring keywords and make retrieval difficult during the search (Natarajan et al., 2010).

The most used keywords among the 100 articles include neuroprotection 6-OHDA antioxidant apoptosis. These words can help in the search for articles related to the topic in addition to indicating an overview of the research because they are words that represent therapeutic targets mechanisms of the neuroprotective effect and neurotoxins used in the papers.

5. Conclusion

The present study identified the 100 most cited articles on PD and PCs. The increased incidence of aging-related diseases due to the increase in the number of elderly people in the world has motivated countries such as China and the USA to seek other strategies for the treatment of PD in order to reduce the side effects and costs of available treatment. Plant foods and beverages have been used for a long time by TCM to treat neurodegenerative diseases, encouraging the search for the mechanisms behind the neuroprotective effect. Research mainly in laboratory models on the use of PCs against PD has grown since 2007 and has highlighted bioactive potentials that include antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity. Despite the promising results obtained, clinical studies are needed to obtain more conclusive answers about the neuroprotective effects of PCs in humans, as the bioactive potential is influenced by bioavailability.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Author contributions

JP, BT, and DB-d-S performed experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. PN, RL, and HR formulated the study concept, designed the study, and made critical revisions of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnagi.2023.1149143/full#supplementary-material

Glossary

| 5-HT | Serotonin |

| 6-OHDA | 6-Hydroxydopamine |

| α-syn | α-synuclein |

| AChE | Acetylcholinesterase |

| Akb | Protein kinase B |

| ARE | Antioxidant response elemento |

| Bax | BCL2 Associated X |

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| BCL2 | BCL2 Apoptosis Regulator |

| BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic fator |

| BTE | Black tea extract |

| CaMKII | Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II |

| CAT | Catalase |

| C-Jun | Protein encoded by the JUN gene |

| COMT | Catechol O-methyltransferase |

| Cyt c | Cytochrome c |

| DA | Dopamine |

| DARPP-32 | Dopamine- and cAMP-regulated phosphoprotein-32 |

| EGCG | Epigallocatechin gallate |

| ERK 1/2 | Extracellular signal-regulated kinases |

| GDNF | Glial cell-derived neurotrophic fator |

| GPx | Glutathione peroxidase |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| GSK-3β | Glycogen synthase kinase-3β |

| GTP | Green tea polyphenols |

| HMOX1 | Heme oxygenase-1 |

| HVA | Homovanillic acid |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-gamma |

| IL | Interleukin |

| iNOS | Nitric oxide synthase |

| JNK 1/2 | c-Jun N-terminal cinase |

| Keap1 | Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| MAO-Bis | monoamine oxidase type B inhibitors |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| MMP | Mitochondrial Membrane Potential |

| mRNA | Messenger ribonucleic acid |

| NDGA | Nordihydroguaiaretic acid |

| NF-ĸB | Nuclear factor-kappa B |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| NQO1 | NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase |

| Nrf-2 | Erythroid nuclear factor-2 related to factor 2 |

| P38 | p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases |

| PCa | Carbonyl protein |

| PC | Phenolic compound |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| PIK-3 | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| PKC | Protein kinase C |

| PLA2 | Phospholipase A2 |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SMAC | Second mitochondria-derived activator of caspase |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| TBARS | Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances |

| TCM | Traditional Chinese medicine |

| TH | Tyrosine hydroxylase |

| TH-ir | TH-immunoreactive |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| TRAP | Total reactive antioxidant potential |

| VOSviewer | Visualization of Similarities Viewer |

| WoS-CC | Web of Science Core Collection |

References

1

An L. J. Guan S. Shi G. F. Bao Y. M. Duan Y. L. Jiang B. (2006). Protocatechuic acid from Alpinia oxyphylla against MPP+-induced neurotoxicity in PC12 cells. Food Chem. Toxicol.44, 436–443. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2005.08.017

2

Anandhan A. Tamilselvam K. Radhiga T. Rao S. Essa M. M. Manivasagam T. (2012). Theaflavin, a black tea polyphenol, protects nigral dopaminergic neurons against chronic MPTP/probenecid induced Parkinson’s disease. Brain Res.1433, 104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.11.021

3

Antunes M. S. Goes A. T. R. Boeira S. P. Prigol M. Jesse C. R. (2014). Protective effect of hesperidin in a model of Parkinson’s disease induced by 6-hydroxydopamine in aged mice. Nutrition30, 1415–1422. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2014.03.024

4

Anusha C. Sumathi T. Joseph L. D. (2017). Protective role of apigenin on rotenone induced rat model of Parkinson’s disease: suppression of neuroinflammation and oxidative stress mediated apoptosis. Chem. Biol. Interact.269, 67–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2017.03.016

5

Aquilano K. Baldelli S. Rotilio G. Ciriolo M. R. (2008). Role of nitric oxide synthases in Parkinson’s disease: a review on the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of polyphenols. Neurochem. Res.33, 2416–2426. doi: 10.1007/s11064-008-9697-6

6

Ardah M. T. Paleologou K. E. Lv G. Khair S. B. A. Al K. A. K. Minhas S. T. et al . (2014). Structure activity relationship of phenolic acid inhibitors of α-synuclein fibril formation and toxicity. Front. Aging Neurosci.6:197. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00197

7

Arredondo F. Echeverry C. Blasina F. Vaamonde L. Díaz M. Rivera F. et al . (2015). “Flavones and Flavonols in brain and disease: facts and pitfalls” in Bioactive nutraceuticals and dietary supplements in neurological and brain disease: Prevention and therapy. eds. WatsonR. R.PreedyV. R. (Elsevier Inc.), 229–236.

8

Arshad A. I. Ahmad P. Karobari M. I. Asif J. A. Alam M. K. Mahmood Z. et al . (2020). Antibiotics: a bibliometric analysis of top 100 classics. Antibiotics9:219. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9050219

9

Ay M. Luo J. Langley M. Jin H. Anantharam V. Kanthasamy A. et al . (2017). Molecular mechanisms underlying protective effects of quercetin against mitochondrial dysfunction and progressive dopaminergic neurodegeneration in cell culture and MitoPark transgenic mouse models of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurochem.141, 766–782. doi: 10.1111/jnc.14033

10

Bala A. Gupta B. (2013). Parkinson′s disease in India: An analysis of publications output during 2002-2011. Int. J. Nutr. Pharmacol. Neurol. Dis.3:254. doi: 10.4103/2231-0738.114849

11

Baldiotti A. L. P. Amaral-Freitas G. Barcelos J. F. Freire-Maia J. de França P. M. Freire-Maia F. B. et al . (2021). The top 100 most-cited papers in cariology: a bibliometric analysis. Caries Res.55, 32–40. doi: 10.1159/000509862

12

Balestrino R. Schapira A. H. V. (2020). Parkinson disease. Eur. J. Neurol.27, 27–42. doi: 10.1111/ene.14108

13

Benito-León J. Louis E. D. (2013). The top 100 cited articles in essential tremor. Tremor Other Hyperkinet. Mov.3, 1–14. doi: 10.5334/tohm.128

14

Bergström A. L. Kallunki P. Fog K. (2016). Development of passive immunotherapies for Synucleinopathies. Mov. Disord.31, 203–213. doi: 10.1002/mds.26481

15

Bournival J. Plouffe M. Renaud J. Provencher C. Martinoli M. G. (2012). Quercetin and sesamin protect dopaminergic cells from MPP+-induced neuroinflammation in a microglial (N9)-neuronal (PC12) coculture system. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev.2012:921941, 1–11. doi: 10.1155/2012/921941

16

Bournival J. Quessy P. Martinoli M. G. (2009). Protective effects of resveratrol and quercetin against MPP+ -nduced oxidative stress act by modulating markers of apoptotic death in dopaminergic neurons. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol.29, 1169–1180. doi: 10.1007/s10571-009-9411-5

17

Brunetti G. di Rosa G. Scuto M. Leri M. Stefani M. Schmitz-Linneweber C. et al . (2020). Healthspan maintenance and prevention of parkinson’s-like phenotypes with hydroxytyrosol and oleuropein aglycone in C. elegans. Int. J. Mol. Sci.21, 1–23. doi: 10.3390/ijms21072588

18

Bureau G. Longpré F. Martinoli M. G. (2008). Resveratrol and quercetin, two natural polyphenols, reduce apoptotic neuronal cell death induced by neuroinflammation. J. Neurosci. Res.86, 403–410. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21503

19

Cao Q. Qin L. Huang F. Wang X. Yang L. Shi H. et al . (2017). Amentoflavone protects dopaminergic neurons in MPTP-induced Parkinson’s disease model mice through PI3K/Akt and ERK signaling pathways. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol.319, 80–90. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2017.01.019

20

Caruana M. Högen T. Levin J. Hillmer A. Giese A. Vassallo N. (2011). Inhibition and disaggregation of α-synuclein oligomers by natural polyphenolic compounds. FEBS Lett.585, 1113–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.03.046

21

Castillo J. Benavente-García O. Lorente J. Alcaraz M. Redondo A. Ortuño A. et al . (2000). Antioxidant activity and radioprotective effects against chromosomal damage induced in vivo by X-rays of flavan-3-ols (Procyanidins) from grape seeds (Vitis vinifera): comparative study versus other phenolic and organic compounds. J. Agric. Food Chem.48, 1738–1745. doi: 10.1021/jf990665o

22

Chao J. Yu M. S. Ho Y. S. Wang M. Chang R. C. C. (2008). Dietary oxyresveratrol prevents parkinsonian mimetic 6-hydroxydopamine neurotoxicity. Free Radic. Biol. Med.45, 1019–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.07.002

23

Chaturvedi R. K. Shukla S. Seth K. Chauhan S. Sinha C. Shukla Y. et al . (2006). Neuroprotective and neurorescue effect of black tea extract in 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis.22, 421–434. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.12.008

24

Chen S. Chan P. Sun S. Chen H. Zhang B. Le W. et al . (2016). The recommendations of Chinese Parkinson’s disease and movement disorder society consensus on therapeutic management of Parkinson’s disease. Transl. Neurodegener.5:12. doi: 10.1186/s40035-016-0059-z

25

Chen H. Q. Jin Z. Y. Wang X. J. Xu X. M. Deng L. Zhao J. W. (2008). Luteolin protects dopaminergic neurons from inflammation-induced injury through inhibition of microglial activation. Neurosci. Lett.448, 175–179. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.10.046

26

Chen Y. Zhang D. Q. Liao Z. Wang B. Gong S. Wang C. et al . (2015). Anti-oxidant polydatin (piceid) protects against substantia nigral motor degeneration in multiple rodent models of Parkinson’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener.10, 1–14. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-10-4

27

Cheng Y. He G. Mu X. Zhang T. Li X. Hu J. et al . (2008). Neuroprotective effect of baicalein against MPTP neurotoxicity: behavioral, biochemical and immunohistochemical profile. Neurosci. Lett.441, 16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.05.116

28

Cheynier V. Comte G. Davies K. M. Lattanzio V. Martens S. (2013). Plant phenolics: recent advances on their biosynthesis, genetics, andecophysiology. Plant Physiol. Biochem.72, 1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.05.009

29

Chung W. G. Miranda C. L. Maier C. S. (2007). Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) potentiates the cytotoxicity of rotenone in neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Brain Res.1176, 133–142. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.07.083

30

Cieslik M. Pyszko J. Strosznajder J. B. (2013). Docosahexaenoic acid and tetracyclines as promising neuroprotective compounds with poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitory activities for oxidative/genotoxic stress treatment. Neurochem. Int.62, 626–636. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2013.02.016

31

Connolly B. S. Lang A. E. (2014). Pharmacological treatment of Parkinson disease: a review. JAMA311, 1670–1683. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3654

32

Cui Q. Li X. Zhu H. (2016). Curcumin ameliorates dopaminergic neuronal oxidative damage via activation of the Akt/Nrf2 pathway. Mol. Med. Rep.13, 1381–1388. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.4657

33

Datla K. P. Christidou M. Widmer W. W. Rooprai H. K. Dexter D. T. (2001). Tissue distribution and neuroprotective effects of citrus avonoid tangeretin in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Neuropharmacol. Neurotoxicol. Nneuro.12, 959–4965. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200112040-00053

34

Datla K. P. Zbarsky V. Rai D. Parkar S. Osakabe N. Aruoma O. I. et al . (2007). Short-term supplementation with plant extracts rich in flavonoids protect nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. J. Am. Coll. Nutr.26, 341–349. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2007.10719621

35

Dorsey E. R. Constantinescu R. Thompson J. P. Biglan K. M. Holloway R. G. Kieburtz K. et al . (2007). Projected number of people with Parkinson disease in the most populous nations, 2005 through 2030. Neurology68, 384–386. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000247740.47667.03

36

Du X. X. Xu H. M. Jiang H. Song N. Wang J. Xie J. X. (2012). Curcumin protects nigral dopaminergic neurons by iron-chelation in the 6-hydroxydopamine rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci. Bull.28, 253–258. doi: 10.1007/s12264-012-1238-2

37

Eng Q. Y. Thanikachalam P. V. Ramamurthy S. (2018). Molecular understanding of Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. J. Ethnopharmacol.210, 296–310. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.08.035

38

Etminan M. Gill S. S. Samii A. (2005). Intake of vitamin E, vitamin C, and carotenoids and the risk of Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol.4, 362–365. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70097-1

39

Fardi A. Kodonas K. Lillis T. Veis A. (2017). Top-cited articles in implant dentistry. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants32, 555–564. doi: 10.11607/jomi.5331

40

Feijoo J. F. Limeres J. Fernández-Varela M. Ramos I. Diz P. (2014). The 100 most cited articles in dentistry. Clin. Oral Investig.18, 699–706. doi: 10.1007/s00784-013-1017-0

41

Ferreira I. C. F. R. Martins N. Barros L. (2017). Phenolic compounds and its bioavailability: in vitro bioactive compounds or health promoters?Adv. Food Nutr. Res.82, 1–44. doi: 10.1016/bs.afnr.2016.12.004

42

Flint Beal M. Oakes D. Shoulson I. Henchcliffe C. Galpern W. R. Haas R. et al . (2014). A randomized clinical trial of high-dosage coenzyme Q10 in early parkinson disease no evidence of benefit. JAMA Neurol.75, 543–552. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.131

43

Gao X. Cassidy A. Schwarzschild M. A. Rimm E. B. Ascherio A. (2012). Habitual intake of dietary flavonoids and risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology78, 1138–1145. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31824f7fc4

44

Goes A. T. R. Jesse C. R. Antunes M. S. Lobo Ladd F. V. AAB L. L. Luchese C. et al . (2018). Protective role of chrysin on 6-hydroxydopamine-induced neurodegeneration a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease: involvement of neuroinflammation and neurotrophins. Chem. Biol. Interact.279, 111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2017.10.019

45

Guan S. Jiang B. Bao Y. M. An L. J. (2006). Protocatechuic acid suppresses MPP+-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptotic cell death in PC12 cells. Food Chem. Toxicol.44, 1659–1666. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2006.05.004

46

Guo S. Bezard E. Zhao B. (2005). Protective effect of green tea polyphenols on the SH-SY5Y cells against 6-OHDA induced apoptosis through ROS-NO pathway. Free Radic. Biol. Med.39, 682–695. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.04.022

47

Guo Y. Bruno R. S. (2015). Endogenous and exogenous mediators of quercetin bioavailability. J. Nutr. Biochem.26, 201–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2014.10.008

48

Guo S. Yan J. Yang T. Yang X. Bezard E. Zhao B. (2007). Protective effects of green tea polyphenols in the 6-OHDA rat model of Parkinson’s disease through inhibition of ROS-NO pathway. Biol. Psychiatry62, 1353–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.04.020

49

Gustavsson A. Svensson M. Jacobi F. Allgulander C. Alonso J. Beghi E. et al . (2011). Cost of disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol.21, 718–779. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.08.008

50

Haleagrahara N. Ponnusamy K. (2010). Neuroprotective effect of Centella asiatica extract (CAE) on experimentally induced parkinsonism in aged Sprague-Dawley rats. J. Toxicol. Sci.35, 41–47. doi: 10.2131/jts.35.41

51

Haleagrahara N. Siew C. J. Mitra N. K. Kumari M. (2011). Neuroprotective effect of bioflavonoid quercetin in 6-hydroxydopamine-induced oxidative stress biomarkers in the rat striatum. Neurosci. Lett.500, 139–143. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.06.021

52

Hong D. P. Fink A. L. Uversky V. N. (2008). Structural characteristics of α-synuclein oligomers stabilized by the flavonoid baicalein. J. Mol. Biol.383, 214–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.08.039

53

Hou R. R. Chen J. Z. Chen H. Kang X. G. Li M. G. Wang B. R. (2008). Neuroprotective effects of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) on paraquat-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells. Cell Biol. Int.32, 22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2007.08.007

54

Hu J. Webster D. Cao J. Shao A. (2018). The safety of green tea and green tea extract consumption in adults - results of a systematic review. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol.95, 412–433. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2018.03.019

55

Hussain G. Zhang L. Rasul A. Anwar H. Sohail M. U. Razzaq A. et al . (2018). Role of plant-derived flavonoids and their mechanism in attenuation of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases: an update of recent data. Molecules23:814. doi: 10.3390/molecules23040814

56

Ishisaka A. Ichikawa S. Sakakibara H. Piskula M. K. Nakamura T. Kato Y. et al . (2011). Accumulation of orally administered quercetin in brain tissue and its antioxidative effects in rats. Free Radic. Biol. Med.51, 1329–1336. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.06.017

57

Jagatha B. Mythri R. B. Vali S. Bharath M. M. S. (2008). Curcumin treatment alleviates the effects of glutathione depletion in vitro and in vivo: therapeutic implications for Parkinson’s disease explained via in silico studies. Free Radic. Biol. Med.44, 907–917. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.11.011

58

Jiang M. Porat-Shliom Y. Pei Z. Cheng Y. Xiang L. Sommers K. et al . (2010). Baicalein reduces E46K α-synuclein aggregation in vitro and protects cells against E46K α-synuclein toxicity in cell models of familiar Parkinsonism. J. Neurochem.114, 419–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06752.x

59

Jimenez-Del-Rio M. Guzman-Martinez C. Velez-Pardo C. (2010). The effects of polyphenols on survival and locomotor activity in drosophila melanogaster exposed to iron and paraquat. Neurochem. Res.35, 227–238. doi: 10.1007/s11064-009-0046-1

60

Johnson S. J. Diener M. D. Kaltenboeck A. Birnbaum H. G. Siderowf A. D. (2013). An economic model of Parkinson’s disease: implications for slowing progression in the United States. Mov. Disord.28, 319–326. doi: 10.1002/mds.25328

61

Kang K. S. Wen Y. Yamabe N. Fukui M. Bishop S. C. Zhu B. T. (2010). Dual beneficial effects of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate on levodopa methylation and hippocampal neurodegeneration: in vitro and in vivo studies. PLoS One5:e11951. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011951

62

Karobari M. I. Maqbool M. Ahmad P. Abdul M. S. M. Marya A. Venugopal A. et al . (2021). Endodontic microbiology: a bibliometric analysis of the top 50 classics. Biomed. Res. Int.2021, 1–12. doi: 10.1155/2021/6657167

63

Karuppagounder S. S. Madathil S. K. Pandey M. Haobam R. Rajamma U. Mohanakumar K. P. (2013). Quercetin up-regulates mitochondrial complex-I activity to protect against programmed cell death in rotenone model of Parkinson’s disease in rats. Neuroscience236, 136–148. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.01.032

64

Kavitha M. Nataraj J. Essa M. M. Memon M. A. Manivasagam T. (2013). Mangiferin attenuates MPTP induced dopaminergic neurodegeneration and improves motor impairment, redox balance and Bcl-2/Bax expression in experimental Parkinson’s disease mice. Chem. Biol. Interact.206, 239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2013.09.016

65

Khan M. M. Ahmad A. Ishrat T. Khan M. B. Hoda M. N. Khuwaja G. et al . (2010). Resveratrol attenuates 6-hydroxydopamine-induced oxidative damage and dopamine depletion in rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Brain Res.1328, 139–151. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.02.031

66

Khan M. M. Kempuraj D. Thangavel R. Zaheer A. (2013). Protection of MPTP-induced neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration by pycnogenol. Neurochem. Int.62, 379–388. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2013.01.029

67

Kieburtz K. Tilley B. C. Elm J. J. Babcock D. Hauser R. Ross G. W. et al . (2015). Effect of creatine monohydrate on clinical progression in patients with parkinson disease: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA313, 584–593. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.120

68

Kim H. G. Ju M. S. Shim J. S. Kim M. C. Lee S. H. Huh Y. et al . (2010). Mulberry fruit protects dopaminergic neurons in toxin-induced Parkinson’s disease models. Br. J. Nutr.104, 8–16. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510000218

69

Kim S. S. Lim J. Bang Y. Gal J. Lee S. U. Cho Y. C. et al . (2012). Licochalcone E activates Nrf2/antioxidant response element signaling pathway in both neuronal and microglial cells: therapeutic relevance to neurodegenerative disease. J. Nutr. Biochem.23, 1314–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.07.012

70

Kim H. J. Song J. Y. Park H. J. Park H. K. Yun D. H. Chung J. H. (2009). Naringin protects against rotenone-induced apoptosis in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol.13, 281–285. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2009.13.4.281

71

Kujawska M. Jodynis-Liebert J. (2018). Polyphenols in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review of in vivo studies. Nutrients10, 1–34. doi: 10.3390/nu10050642

72

Latos-Brozio M. Masek A. (2019). Structure-activity relationships analysis of monomeric and polymeric polyphenols (quercetin, Rutin and Catechin) obtained by various polymerization methods. Chemist. Biodiv.16:e1900426. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201900426

73

Lee E. Park H. R. Ji S. T. Lee Y. Lee J. (2014). Baicalein attenuates astroglial activation in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyridine-induced Parkinson’s disease model by downregulating the activations of nuclear factor-κB, ERK, and JNK. J. Neurosci. Res.92, 130–139. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23307

74