- 1Heze Hospital Affiliated of Shandong First Medical University, Heze, China

- 2Shandong First Medical University and Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences, Jinan, China

- 3Department of Neurology, Affiliated Yantai Yuhuangding Hospital of Qingdao University, Yantai, China

- 4Shandong Provincial Key Laboratory of Neuroimmune Interaction and Regulation, Yantai, China

- 5Department of Neurology, Jiaozhou Branch of Shanghai East Hospital, Tongji University, Jiaozhou, China

- 6Department of Neurology, Yantaishan Hospital, Yantai, China

Objective: Subsyndromal symptomatic depression (SSD) has been increasingly implicated in the pathophysiological processes of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). However, it remains unclear whether SSD and amyloid-β (Aβ) pathology jointly contribute to tau deposition. This study aimed to investigate the interaction between SSD and Aβ status on regional tau accumulation in non-demented older adults.

Materials and methods: We analyzed data from 391 non-demented older adults in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) who underwent Aβ and tau positron emission tomography (PET) scans, as well as Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) assessments. Aβ positivity (Aβ+) was defined by established tracer-specific standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) thresholds (≥1.11 for 18F-florbetapir or ≥1.08 for 18F-florbetaben). SSD was defined as a GDS-15 score of 1–5. Linear mixed-effects models were applied to assess the longitudinal effects of SSD and Aβ status on regional tau accumulation over 2 years.

Results: At baseline, significant interactions between SSD and Aβ status were observed for regional tau SUVRs, with the Aβ+/SSD+ group exhibiting significantly higher tau levels across all Braak stages compared with the other groups. Longitudinal analyses identified a significant three-way interaction among SSD, Aβ status, and time in the Braak III/IV and Braak V/VI regions. Moreover, the Aβ+/SSD+ group demonstrated significantly faster tau accumulation compared to all other groups. The Aβ+/SSD− group also exhibited greater tau accumulation than the Aβ−/SSD− group, whereas no significant differences were observed between the Aβ− groups.

Conclusion: These findings suggest that SSD is associated with greater early tau accumulation in individuals with Aβ pathology.

1 Introduction

Dementia represents a major and growing global health concern, with rising prevalence and significant social and economic impacts. By 2050, the number of people living with dementia is expected to more than double, placing unprecedented strain on healthcare systems worldwide (GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators, 2022). Late-life depression is common in older adults and has consistently been associated with an increased risk of developing dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Green et al., 2003; Diniz et al., 2013; Bennett and Thomas, 2014; Ly et al., 2021). Meta-analyses further indicate that individuals with depression have approximately twice the risk of developing dementia compared to those without depressive symptoms (Jorm, 2001; Ownby et al., 2006).

Depressive symptoms range from mild subthreshold conditions, such as subsyndromal symptomatic depression (SSD), to major depressive disorder (MDD). SSD is more prevalent than MDD in older adults and has been associated with functional disability (Hybels et al., 2009) and cognitive impairment (Boyle et al., 2010). Longitudinal studies have shown that SSD is linked to an approximately threefold higher risk of developing dementia in non-demented older adults (Oh et al., 2021), suggesting that SSD may represent an early and potentially modifiable marker of dementia risk. Recent meta-analytic evidence has identified depression, along with age, APOE ε4, and lower education, as key predictors of cognitive decline among non-demented individuals (Li et al., 2023). Neuroimaging studies have consistently associated SSD with accelerated cognitive decline and regional brain atrophy, particularly in AD-vulnerable regions such as the hippocampus and temporal cortex (Zhang et al., 2020; Jing et al., 2024). Importantly, emerging evidence suggests that SSD is also associated with AD-related pathology. SSD has been shown to exacerbate cognitive deterioration in the presence of elevated amyloid-β (Aβ) burden (Zhang et al., 2020), suggesting a potential interaction between depressive symptoms and amyloid pathology. Similarly, recent evidence has shown that individuals with both Aβ positivity and mild depressive symptoms have the fastest structural brain atrophy and metabolic decline, along with more rapid cognitive deterioration (Zhang et al., 2025). Beyond these Aβ-related effects, cross-sectional neuroimaging studies have also demonstrated higher tau burden in individuals with depressive symptoms (Gatchel et al., 2017), raising the possibility that depression may be linked not only to Aβ burden but also to tau pathology. However, it remains unclear whether SSD and Aβ pathology jointly contribute to tau accumulation.

To address this gap, the present study investigated whether amyloid pathology modulates the association between SSD and regional tau accumulation in non-demented older adults. We hypothesized that SSD would be associated with greater tau accumulation primarily in the presence of Aβ positivity.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Data sources

Participants for this study were drawn from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database,1 with data downloaded on October 10, 2023. ADNI was launched in 2003 under the leadership of Dr. Michael W. Weiner. It incorporates serial MRI, positron emission tomography (PET), fluid biomarker measurements, and comprehensive neuropsychological assessments to support the early detection and longitudinal tracking of AD.

2.2 Participants

A total of 391 non-demented participants were included from the ADNI database. Eligibility required availability of a baseline amyloid PET scan (18F-florbetapir or 18F-florbetaben) and longitudinal 18F-flortaucipir tau PET imaging. All baseline scans were acquired within a six-month window. Participants were classified as cognitively normal (CN; MMSE > 24, CDR = 0) or as having mild cognitive impairment (MCI; MMSE > 24, CDR = 0.5, objective memory impairment on the education-adjusted Wechsler Memory Scale II, preserved activities of daily living) according to ADNI diagnostic protocols. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are available on the ADNI website (see text footnote 1).

2.3 Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

The ADNI study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of each participating site, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The present analyses used data from the ADNI-3 phase, which is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02854033).

2.4 Depression scale measurement

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) in the ADNI cohort. Total scores range from 0 to 15, with higher scores indicating greater severity of depressive symptoms. A GDS-15 score of ≥ 6 is generally considered indicative of clinically significant depression (Marc et al., 2008). Consistent with prior studies (Mackin et al., 2012; Bertens et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2020), SSD was defined as a GDS-15 score of 1–5 (coded as SSD+), whereas a score of 0 indicated the absence of depressive symptoms (coded as SSD−).

2.5 PET imaging biomarkers

Amyloid PET scans were acquired 50–70 min after intravenous injection of 18F-florbetapir or 90–110 min after injection of 18F-florbetaben, each scan was reconstructed into 4 × 5-min frames. Tau PET imaging was performed 75–105 min after injection of 18F-flortaucipir and reconstructed into 6 × 5-min frames. Detailed information on PET acquisition and preprocessing procedures in ADNI is available at https://adni.loni.usc.edu/data-samples/adni-data/neuroimaging/pet/.

For amyloid PET, standardized uptake value ratios (SUVRs) were calculated by dividing the mean tracer uptake within a predefined cortical composite region comprising the frontal, lateral parietal, anterior and posterior cingulate, and lateral temporal cortices by the uptake in the whole cerebellum (Landau et al., 2012). Aβ positivity (Aβ+) was determined using global SUVR thresholds of ≥1.11 for florbetapir and ≥1.08 for florbetaben (Royse et al., 2021). Amyloid PET data were obtained from the ADNI files: “UCBERKELEYAV45_04_26_22.csv” for florbetapir and “UCBERKELEYFBB_04_26_22.csv” for florbetaben.

For tau PET, SUVRs were calculated for three composite regions of interest (ROIs) approximating Braak stages I, III/IV, and V/VI. Braak stage I included the entorhinal cortex. Braak stages III/IV included the parahippocampal gyri, fusiform gyri, lingual gyri, amygdala, middle temporal gyri, inferior temporal gyri, insula, anterior cingulate cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, isthmus cingulate cortex, and temporal poles. Braak stages V/VI included the frontal poles, superior frontal gyri, middle frontal gyri, lateral orbitofrontal gyri, medial orbitofrontal gyri, pars opercularis, pars orbitalis, pars triangularis, supramarginal gyri, superior parietal lobules, inferior parietal lobules, lateral occipital cortex, precuneus, banks of the superior temporal sulcus, superior temporal gyri, and transverse temporal gyri. In addition, a meta-temporal region was examined, defined as the bilateral entorhinal cortex, amygdala, fusiform gyrus, and inferior and middle temporal cortices, based on FreeSurfer segmentation as specified in the “Meta Temporal ROI” section (Jack et al., 2017). The Braak stage II region (hippocampus) was excluded from all analyses due to potential off-target binding from the adjacent choroid plexus (Lemoine et al., 2018). Longitudinal tau PET data were acquired at baseline, 1-year, and 2-year follow-up visits using 18F-flortaucipir and retrieved from the ADNI file “UCBERKELEYAV1451_04_26_22.csv.”

2.6 Covariate data collection

All covariate information used for statistical adjustment, including age (years, continuous), sex (0 = male, 1 = female), years of education (continuous), APOE ε4 carrier status (0 = non-carrier, 1 = carrier), and diagnostic status (0 = CN, 1 = MCI), was extracted from the ADNI files (“ADNIMERGE.csv” and “APOERES.csv”). These variables were included to control for demographic and genetic factors known to influence both depressive symptoms and AD pathology.

2.7 Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26 and R software (version 4.3.3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A two-tailed p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. For continuous variables with a normal distribution, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by false discovery rate (FDR) correction was applied to adjust for multiple comparisons. For categorical variables, group differences were assessed using the chi-square test. For non-normally distributed continuous variables, the Kruskal–Wallis test with FDR correction was used.

Regional tau SUVRs were mildly right-skewed. We assessed the normality of model residuals by inspecting residual-versus-fitted plots and normal Q–Q plots and found them to be approximately symmetric and centered around zero, with only modest departures in the tails. Therefore, untransformed tau PET SUVR values were used in all baseline and longitudinal regression models. For baseline analyses, multiple linear regression models were fitted for each tau PET region of interest (ROI). Each model included SSD status, Aβ status, and their interaction term (SSD × Aβ) as predictors, with age, sex, years of education, diagnostic status, and APOE ε4 carrier status as covariates. Multicollinearity among covariates was assessed using variance inflation factors (VIFs), all of which were below 5, indicating no significant collinearity.

For longitudinal analyses, linear mixed-effects models were employed to examine the effects of SSD and Aβ status on changes in regional tau PET SUVRs over time. Each model included the main effects of baseline age, sex, APOE ε4 carrier status, diagnostic status, and years of education, their interactions with time, and a random intercept for each participant. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted to evaluate differences in tau accumulation trajectories among the four joint SSD/Aβ groups (Aβ−/SSD−, Aβ−/SSD+, Aβ+/SSD−, and Aβ+/SSD+), with FDR correction applied for multiple comparisons.

3 Results

3.1 Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics

This study included 391 non-demented participants, comprising 115 Aβ−/SSD−, 124 Aβ−/SSD+, 70 Aβ+/SSD−, and 82 Aβ+/SSD+ individuals (Table 1). Regarding demographic characteristics, the Aβ+/SSD+ group was significantly older and had a higher proportion of APOE ε4 carriers compared with both the Aβ−/SSD− and Aβ−/SSD+ groups. The Aβ+/SSD+ group also showed the highest prevalence of MCI compared with the other three groups. There were no significant differences in sex distribution or years of education among the four groups.

Regarding regional tau burden, significant group differences were observed across all Braak regions and the meta-temporal region (all p < 0.001). The Aβ+/SSD+ group exhibited the highest SUVRs in Braak I, Braak III/IV, Braak V/VI, and the meta-temporal region compared with other groups. The Aβ+/SSD− group also showed significantly higher tau SUVRs than both Aβ− groups, whereas no significant differences were observed between the Aβ−/SSD− and Aβ−/SSD+ groups.

3.2 Baseline regional tau differences by SSD and Aβ status

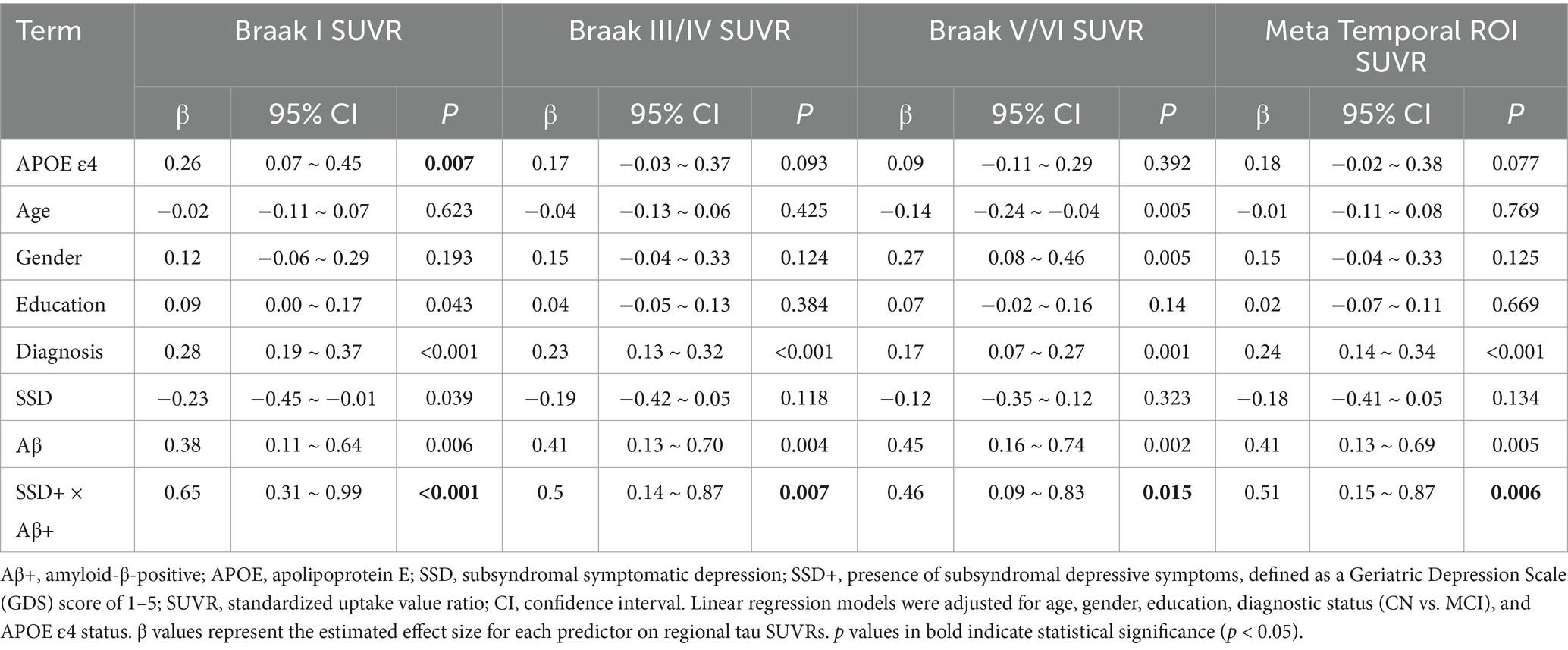

To assess the interaction between Aβ status and SSD on baseline regional tau deposition, multiple linear regression models were fitted for each tau PET ROI (Braak I, Braak III/IV, Braak V/VI, and the meta-temporal region), adjusting for age, sex, education, diagnostic status (CN vs. MCI), and APOE ε4 carrier status. A significant interaction between SSD and Aβ status was observed across all regions, including Braak I (β = 0.65, p < 0.001), Braak III/IV (β = 0.50, p = 0.007), Braak V/VI (β = 0.46, p = 0.015), and the meta-temporal region (β = 0.51, p = 0.006), as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Associations of Aβ status, SSD, and their interaction with baseline regional tau SUVRs among non-demented participants.

3.3 Longitudinal change models

To examine longitudinal changes in tau accumulation, linear mixed-effects models were used to assess the effects of Aβ status, SSD, and their interaction with time on regional tau PET SUVRs over a two-year follow-up period.

Significant three-way interactions among Aβ status, SSD, and time were observed in the Braak III/IV (estimate = 0.0335, p = 0.049) and Braak V/VI (estimate = 0.0285, p = 0.047; see Table 3) regions, indicating that the joint presence of Aβ pathology and SSD was associated with a faster rate of tau accumulation over time.

Table 3. Longitudinal linear mixed-effects models for changes in regional tau PET SUVRs among non-demented participants.

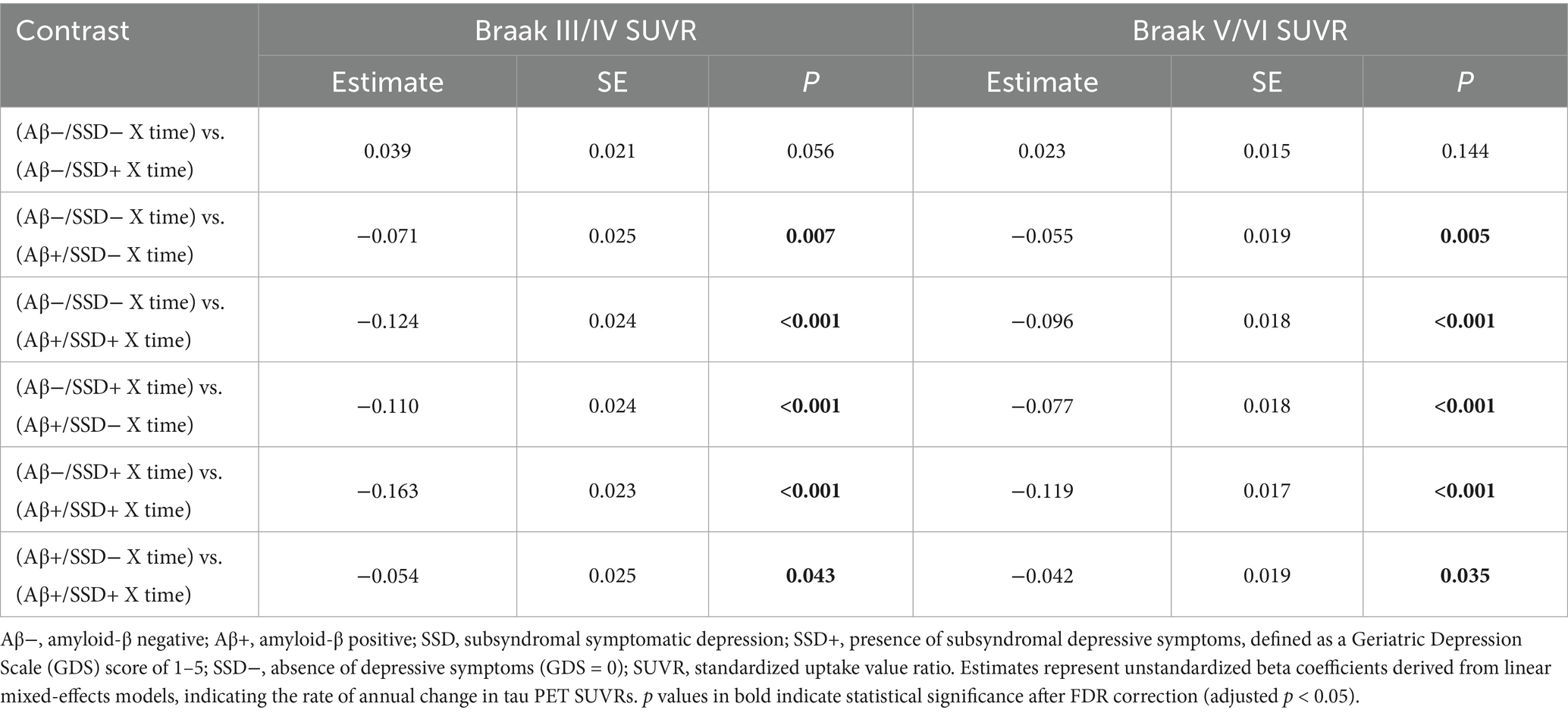

To further characterize these effects, post hoc pairwise comparisons were performed across the four groups (Aβ−/SSD−, Aβ−/SSD+, Aβ+/SSD−, and Aβ+/SSD+), as shown in Table 4 and Figures 1A,B. The Aβ+/SSD+ group exhibited significantly greater annual tau SUVRs in Braak III/IV (p = 0.043) and Braak V/VI (p = 0.035) compared with the Aβ+/SSD− group. Moreover, relative to both Aβ− groups, the Aβ+/SSD+ group showed markedly faster tau accumulation in Braak III/IV and Braak V/VI (all p < 0.001). Consistent with established Aβ-related tau propagation patterns, the Aβ+/SSD− group exhibited significantly faster tau accumulation in Braak III/IV (p = 0.007) and Braak V/VI (p = 0.005) compared with the Aβ−/SSD− group. However, no significant differences were observed between the Aβ−/SSD− and Aβ−/SSD+ groups.

Table 4. Pairwise comparisons of longitudinal tau accumulation across Aβ/SSD groups among non-demented participants.

Figure 1. Longitudinal changes in tau accumulation by joint Aβ and SSD status. Aβ−, amyloid-β-negative; Aβ+, amyloid-β-positive; SSD, subsyndromal symptomatic depression; SSD+, presence of SSD (GDS score 1–5); SSD−, absence of depressive symptoms (GDS = 0). The Aβ+/SSD + group exhibited higher tau accumulation over time compared with the other groups in the Braak III/IV (A) and Braak V/VI (B) regions.

3.4 Sensitivity analysis

To assess the robustness of our findings, we repeated the baseline and longitudinal analyses using square-root–transformed tau-PET SUVRs to address potential non-normality. At baseline, the interaction between SSD and Aβ status remained significant across all examined regions (Supplementary Table S1). In the longitudinal models, a significant three-way interaction among Aβ status, SSD, and time was observed in the Braak V/VI region (estimate = 0.013, p = 0.046; Supplementary Table S2). The corresponding interaction in Braak III/IV showed a similar pattern but did not reach statistical significance. Pairwise comparisons further showed that the Aβ+/SSD+ group exhibited the greatest annual increase in tau-PET SUVRs in both Braak III/IV and Braak V/VI compared with other groups (Supplementary Table S3). These findings indicate that the pattern of associations was consistent after transformation.

4 Discussion

The present study identified significant interactions between SSD and Aβ pathology in relation to regional tau burden among non-demented older adults. At baseline, significant interactions between SSD and Aβ status were observed for regional tau SUVRs, with the Aβ+/SSD+ group exhibiting significantly higher tau accumulation across all Braak stages compared with the other groups. Longitudinal analyses further identified a significant three-way interaction among SSD, Aβ status, and time in the Braak III/IV and Braak V/VI regions, suggesting that the joint presence of SSD and Aβ pathology accelerated tau accumulation over time. The Aβ+/SSD− group exhibited greater tau accumulation than the Aβ−/SSD− group, while no significant differences were observed between the Aβ− groups. Furthermore, the Aβ+/SSD+ group exhibited the most pronounced longitudinal increases in tau SUVRs within these regions compared with the other groups. Taken together, these findings suggest that the relationship between SSD and tau accumulation is evident primarily in the context of Aβ positivity, implying that amyloid pathology may modulate how depressive symptoms relate to tau deposition in non-demented older adults.

Depression is characterized by mood disturbances, impaired attention and concentration, and a diminished sense of self-worth. While depression and AD are generally considered distinct clinical entities, they share several common features, complicating the understanding of their interrelationship and making it difficult to differentiate between the two conditions when they co-occur. Depression and cognitive impairment share a bidirectional relationship, where midlife or late-life depression symptoms are related to a higher risk of subsequent MCI, and individuals with MCI are more prone to developing depression (Guo et al., 2023). The deposition of AD-related biomarkers, including Aβ and tau, has been linked to depression, further complicating the relationship between depression and AD. A systematic review of 15 cross-sectional studies has provided evidence for a potential link between amyloid pathology and MDD in older adults (Harrington et al., 2015). Moreover, SSD has been found to be associated with higher cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) amyloid levels and an 83% increased likelihood of developing AD in elderly adults without dementia (Xu et al., 2021). The relationship between SSD and Aβ pathology was bidirectional, with the effects of depressive symptoms on cognitive impairment and AD risk being partially mediated by Aβ pathology (Xu et al., 2021). In terms of tau pathology, a meta-analysis indicated that CSF total tau levels were similar in individuals with MDD and healthy controls. Cross-sectional neuroimaging and postmortem studies have reported associations between depressive symptoms and elevated cerebral tau burden (Gatchel et al., 2017; Babulal et al., 2020; Gonzales et al., 2021; Moriguchi et al., 2021; Tommasi et al., 2021), suggesting a potential contribution of depression to early tau pathology. Building on prior research, our results reveal significant interactions between SSD and Aβ status in relation to tau accumulation, as measured by tau PET. Specifically, we observed a significant interaction among Aβ status, time, and SSD in relation to tau accumulation in the Braak III/IV and Braak V/VI regions. These findings indicate that SSD is associated with faster tau accumulation primarily among Aβ-positive individuals, with no association observed in Aβ-negative participants. Together, these results suggest that amyloid pathology may modulate the relationship between depressive symptoms and tau deposition.

Several mechanisms may explain the interaction between depressive symptoms and Aβ pathology in tau accumulation in AD. First, depressive symptoms have been associated with impaired hippocampal neurogenesis (Kreisel et al., 2014), which may exacerbate neurodegenerative processes and accelerate the accumulation of toxic proteins in AD, including Aβ and tau. Second, chronic inflammation has been identified as a key mechanism linking depression to AD (Hayley et al., 2020). Recent studies have demonstrated that inflammatory alterations in the CSF closely parallel the burden of Aβ and tau (Cullen et al., 2021), while sustained activation of glial cells and inflammatory signaling pathways further exacerbates tau hyperphosphorylation and propagation (Chen and Yu, 2023). Third, depressive symptoms have been associated with dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, leading to chronically elevated glucocorticoid levels that may contribute to neurodegeneration (Galts et al., 2019). Moreover, sustained glucocorticoid exposure increases neuronal activity and Aβ release, thereby facilitating Aβ aggregation into plaques (Dong and Csernansky, 2009). In addition, experimental studies have further shown that stress-level glucocorticoid exposure increases Aβ production and promotes tau accumulation, suggesting that elevated glucocorticoids accelerate both Aβ and tau pathology (Green et al., 2006). These mechanisms collectively point to a complex interaction between depression, Aβ pathology, and tau accumulation, with implications for AD progression.

The relationship between depression and tau pathology may be bidirectional, with SSD potentially representing the downstream clinical phenotype of tauopathy. Several studies suggest that neurodegeneration may be a key cause of depression, disrupting circuits involved in emotional regulation. A significant correlation between tau levels and psychological symptoms of dementia was found in a study of memory clinic patients (Cotta Ramusino et al., 2021). Similarly, a study involving older adults demonstrated that elevated tau levels were associated with an increased likelihood of depression, with participants who had elevated tau being twice as likely to be depressed (Babulal et al., 2020). Moreover, elevated plasma total tau levels have been shown to be significantly associated with symptoms of depression, apathy, anxiety, worry, and sleep disturbances (Hall et al., 2021), and higher CSF tau levels have been associated with a greater risk of depression and apathy over time (Banning et al., 2021). These findings support the hypothesis that tau pathology may not only be a consequence of depression but may also contribute to the onset of depressive symptoms. Thus, future studies are needed to further investigate the bidirectional relationship between depressive symptoms and tau pathology.

Several limitations should be acknowledged when interpreting these findings. First, although all non-demented participants were included, the Aβ+/SSD+ group remained relatively small, which may limit the robustness and generalizability of group-specific results. Second, participants were drawn from the ADNI cohort, which predominantly includes well-educated, health-conscious volunteers, potentially limiting the representativeness of the sample. Third, the inclusion of both CN and MCI participants may have introduced residual heterogeneity. Although diagnostic status (CN vs. MCI) was included as a covariate in all statistical models, unmeasured diagnostic differences may still have influenced the results. Fourth, external validation was not feasible as other publicly available cohorts currently lack tau PET imaging data, limiting replication of tau-related findings. Fifth, the relatively short follow-up duration for longitudinal tau PET may have reduced sensitivity to detect slower or nonlinear trajectories of tau accumulation, potentially underestimating long-term effects. Finally, given the observational design, the reported associations among SSD, Aβ pathology, and tau accumulation should not be interpreted as causal. Future studies incorporating larger and more heterogeneous cohorts, longer longitudinal follow-up, and multimodal biomarker approaches will be essential to replicate and extend these findings.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that SSD is associated with greater tau accumulation primarily in individuals with Aβ positivity, suggesting that amyloid pathology modulates the relationship between depressive symptoms and tau pathology during the early stages of AD. These findings indicate that SSD may serve as an early clinical marker of increased vulnerability to tau aggregation in the presence of Aβ pathology. Further longitudinal and mechanistic studies are warranted to clarify the underlying biological pathways and to determine whether early identification and management of SSD could help mitigate tau-related neurodegeneration.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://adni.loni.usc.edu.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the institutional review boards of all participating sites, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their authorized representatives in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The current analysis used de-identified data from the ADNI database, and no additional ethical approval was required. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

JB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft. XW: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. HW: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. YT: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. MK: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. MB: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. CZ: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81571234) and the Shandong Provincial Key Research and Development Program (Grant No. 2018GSF118235). Data collection and sharing for this project were funded by the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California

Group member of the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (http://adni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in the analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at: https://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf.

Acknowledgments

ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California. As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnagi.2025.1679285/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

Babulal, G. M., Roe, C. M., Stout, S. H., Rajasekar, G., Wisch, J. K., Benzinger, T. L. S., et al. (2020). Depression is associated with tau and not amyloid positron emission tomography in cognitively Normal adults. J Alzheimer's Dis 74, 1045–1055. doi: 10.3233/JAD-191078,

Banning, L. C. P., Ramakers, I. H. G. B., Rosenberg, P. B., Lyketsos, C. G., and Leoutsakos, J.-M. S.Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (2021). Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers as predictors of trajectories of depression and apathy in cognitively normal individuals, mild cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease dementia. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 36, 224–234. doi: 10.1002/gps.5418

Bennett, S., and Thomas, A. J. (2014). Depression and dementia: cause, consequence or coincidence? Maturitas 79, 184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.05.009,

Bertens, D., Tijms, B. M., Vermunt, L., Prins, N. D., Scheltens, P., and Visser, P. J. (2017). The effect of diagnostic criteria on outcome measures in preclinical and prodromal Alzheimer’s disease: implications for trial design. Alzheimers Dement. 3, 513–523. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2017.08.005,

Boyle, L. L., Porsteinsson, A. P., Cui, X., King, D. A., and Lyness, J. M. (2010). Depression predicts cognitive disorders in older primary care patients. J. Clin. Psychiatry 71, 74–79. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04724gry,

Chen, Y., and Yu, Y. (2023). Tau and neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease: interplay mechanisms and clinical translation. J. Neuroinflammation 20:165. doi: 10.1186/s12974-023-02853-3,

Cotta Ramusino, M., Perini, G., Vaghi, G., Dal Fabbro, B., Capelli, M., Picascia, M., et al. (2021). Correlation of frontal atrophy and CSF tau levels with neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with cognitive impairment: a memory clinic experience. Front. Aging Neurosci. 13:595758. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2021.595758,

Cullen, N. C., Mälarstig, A. n., Stomrud, E., Hansson, O., and Mattsson-Carlgren, N. (2021). Accelerated inflammatory aging in Alzheimer’s disease and its relation to amyloid, tau, and cognition. Sci. Rep. 11:1965. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-81705-7,

Diniz, B. S., Butters, M. A., Albert, S. M., Dew, M. A., and Reynolds, C. F. (2013). Late-life depression and risk of vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based cohort studies. Br. J. Psychiatry 202, 329–335. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.118307,

Dong, H., and Csernansky, J. G. (2009). Effects of stress and stress hormones on amyloid-β protein and plaque deposition. J Alzheimer's Dis 18, 459–469. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1152,

Galts, C. P. C., Bettio, L. E. B., Jewett, D. C., Yang, C. C., Brocardo, P. S., Rodrigues, A. L. S., et al. (2019). Depression in neurodegenerative diseases: common mechanisms and current treatment options. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 102, 56–84. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.04.002,

Gatchel, J. R., Donovan, N. J., Locascio, J. J., Schultz, A. P., Becker, J. A., Chhatwal, J., et al. (2017). Depressive symptoms and tau accumulation in the inferior temporal lobe and entorhinal cortex in cognitively Normal older adults: a pilot study. J Alzheimer's Dis 59, 975–985. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170001,

GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators (2022). Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Public Health 7, e105–e125. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00249-8,

Gonzales, M. M., Samra, J., O’Donnell, A., Mackin, R. S., Salinas, J., Jacob, M. E., et al. (2021). Association of Midlife Depressive Symptoms with regional amyloid-β and tau in the Framingham heart study. J Alzheimer's Dis 82, 249–260. doi: 10.3233/JAD-210232,

Green, K. N., Billings, L. M., Roozendaal, B., McGaugh, J. L., and LaFerla, F. M. (2006). Glucocorticoids increase amyloid-β and tau pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 26, 9047–9056. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2797-06.2006,

Green, R. C., Cupples, L. A., Kurz, A., Auerbach, S., Go, R., Sadovnick, D., et al. (2003). Depression as a risk factor for Alzheimer disease: the MIRAGE study. Arch. Neurol. 60, 753–759. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.5.753,

Guo, Y., Pai, M., Xue, B., and Lu, W. (2023). Bidirectional association between depressive symptoms and mild cognitive impairment over 20 years: evidence from the health and retirement study in the United States. J. Affect. Disord. 338, 449–458. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2023.06.046,

Hall, J. R., Petersen, M., Johnson, L., and O’Bryant, S. E. (2021). Plasma Total tau and neurobehavioral symptoms of cognitive decline in cognitively Normal older adults. Front. Psychol. 12:774049. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.774049,

Harrington, K. D., Lim, Y. Y., Gould, E., and Maruff, P. (2015). Amyloid-beta and depression in healthy older adults: a systematic review. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 49, 36–46. doi: 10.1177/0004867414557161,

Hayley, S., Hakim, A. M., and Albert, P. R. (2020). Depression, dementia and immune dysregulation. Brain 144, 746–760. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa405,

Hybels, C. F., Pieper, C. F., and Blazer, D. G. (2009). The complex relationship between depressive symptoms and functional limitations in community-dwelling older adults: the impact of subthreshold depression. Psychol. Med. 39, 1677–1688. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709005650,

Jack, C. R., Wiste, H. J., Weigand, S. D., Therneau, T. M., Lowe, V. J., Knopman, D. S., et al. (2017). Defining imaging biomarker cut points for brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 13, 205–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.08.005,

Jing, C., Kong, M., Ng, K. P., Xu, L., Ma, G., Ba, M., et al. (2024). Hippocampal volume maximally modulates the relationship between subsyndromal symptomatic depression and cognitive impairment in non-demented older adults. J. Affect. Disord. 367, 640–646. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2024.09.018,

Jorm, A. F. (2001). History of depression as a risk factor for dementia: an updated review. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 35, 776–781. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00967.x,

Kreisel, T., Frank, M. G., Licht, T., Reshef, R., Ben-Menachem-Zidon, O., Baratta, M. V., et al. (2014). Dynamic microglial alterations underlie stress-induced depressive-like behavior and suppressed neurogenesis. Mol. Psychiatry 19, 699–709. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.155,

Landau, S. M., Mintun, M. A., Joshi, A. D., Koeppe, R. A., Petersen, R. C., Aisen, P. S., et al. (2012). Amyloid deposition, hypometabolism, and longitudinal cognitive decline. Ann. Neurol. 72, 578–586. doi: 10.1002/ana.23650,

Lemoine, L., Leuzy, A., Chiotis, K., Rodriguez-Vieitez, E., and Nordberg, A. (2018). Tau positron emission tomography imaging in tauopathies: the added hurdle of off-target binding. Alzheimers Dement. 10, 232–236. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2018.01.007,

Li, H., Tan, C.-C., Tan, L., and Xu, W. (2023). Predictors of cognitive deterioration in subjective cognitive decline: evidence from longitudinal studies and implications for SCD-plus criteria. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 94, 844–854. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2022-330246,

Ly, M., Karim, H. T., Becker, J. T., Lopez, O. L., Anderson, S. J., Aizenstein, H. J., et al. (2021). Late-life depression and increased risk of dementia: a longitudinal cohort study. Transl. Psychiatry 11:147. doi: 10.1038/s41398-021-01269-y,

Mackin, R. S., Insel, P., Aisen, P. S., Geda, Y. E., and Weiner, M. W. (2012). Longitudinal stability of subsyndromal symptoms of depression in individuals with mild cognitive impairment: relationship to conversion to dementia after three years. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 27, 355–363. doi: 10.1002/gps.2713

Marc, L. G., Raue, P. J., and Bruce, M. L. (2008). Screening performance of the 15-item geriatric depression scale in a diverse elderly home care population. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 16, 914–921. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318186bd67,

Moriguchi, S., Takahata, K., Shimada, H., Kubota, M., Kitamura, S., Kimura, Y., et al. (2021). Excess tau PET ligand retention in elderly patients with major depressive disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 26, 5856–5863. doi: 10.1038/s41380-020-0766-9,

Oh, D. J., Han, J. W., Bae, J. B., Kim, T. H., Kwak, K. P., Kim, B. J., et al. (2021). Chronic subsyndromal depression and risk of dementia in older adults. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 55, 809–816. doi: 10.1177/0004867420972763,

Ownby, R. L., Crocco, E., Acevedo, A., John, V., and Loewenstein, D. (2006). Depression and risk for Alzheimer disease: systematic review, meta-analysis, and metaregression analysis. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 63, 530–538. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.530,

Royse, S. K., Minhas, D. S., Lopresti, B. J., Murphy, A., Ward, T., Koeppe, R. A., et al. (2021). Validation of amyloid PET positivity thresholds in centiloids: a multisite PET study approach. Alzheimer's Res Ther 13:99. doi: 10.1186/s13195-021-00836-1,

Tommasi, N. S., Gonzalez, C., Briggs, D., Properzi, M. J., Gatchel, J. R., Marshall, G. A., et al. (2021). Affective symptoms and regional cerebral tau burden in early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 36, 1050–1058. doi: 10.1002/gps.5530,

Xu, W., Feng, W., Shen, X.-N., Bi, Y.-L., Ma, Y.-H., Li, J.-Q., et al. (2021). Amyloid pathologies modulate the associations of minimal depressive symptoms with cognitive impairments in older adults without dementia. Biol. Psychiatry 89, 766–775. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.07.004,

Zhang, X.-H., Tan, C.-C., Zheng, Y.-W., Ma, X., Gong, J.-N., Tan, L., et al. (2025). Interactions between mild depressive symptoms and amyloid pathology on the trajectory of neurodegeneration, cognitive decline, and risk of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Affect. Disord. 368, 73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2024.08.235,

Zhang, Z., Wei, F., Shen, X.-N., Ma, Y.-H., Chen, K.-L., Dong, Q., et al. (2020). Associations of Subsyndromal symptomatic depression with cognitive decline and brain atrophy in elderly individuals without dementia: a longitudinal study. J. Affect. Disord. 274, 262–268. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.097,

Keywords: subsyndromal symptomatic depression, amyloid-β, tau, Alzheimer’s disease, neuroimaging biomarkers

Citation: Bai J, Wei X, Wei H, Tai Y, Kong M, Ba M and Zhang C (2025) Amyloid pathology modulates the relationship between subsyndromal symptomatic depression and tau accumulation in non-demented older adults. Front. Aging Neurosci. 17:1679285. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2025.1679285

Edited by:

Giuseppina Amadoro, National Research Council (CNR), ItalyReviewed by:

Wei Xu, Qingdao University Medical College, ChinaLaura Vegas Gómez, University of Malaga, Spain

Copyright © 2025 Bai, Wei, Wei, Tai, Kong, Ba and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chunhua Zhang, ZHJfemhhbmdjaHVuaHVhQDE2My5jb20=; Maowen Ba, YmFtYW93ZW5AMTYzLmNvbQ==; Min Kong, a2tfa21tQHNpbmEuY29t

Jiahe Bai

Jiahe Bai Xiaonan Wei2

Xiaonan Wei2 Hongchun Wei

Hongchun Wei Maowen Ba

Maowen Ba Chunhua Zhang

Chunhua Zhang