Abstract

Background:

This study investigated whether a 24-week, community-based multicomponent exercise intervention (MCEI) can improve body composition and cognitive function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

Methods:

In this single-center, parallel-group randomized controlled trial (RCT), 64 community-dwelling adults aged 65–75 years with MCI characterized by Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) ≥ 24, Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) ≤ 26, Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) = 0.5, low skeletal muscle mass were randomly allocated (1:1) to a MCEI (aerobic, resistance and balance training, 3 × 60 min/week) or to a usual-activity control (UAC) group receiving weekly health education. Primary outcomes were skeletal muscle mass (SMM), fat-mass index (FMI), MMSE and MoCA; secondary outcomes included skeletal muscle index (SMI), basal metabolic rate (BMR), Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) and Animal Fluency Test (AFT). Assessments were conducted at baseline and within 1 week post-intervention by trained, blinded assessors. Intervention effects were examined with a 2 (group) × 2 (time) repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), reporting partial eta-squared (η2) as the effect-size estimate.

Results:

A significant Group × Time interaction was observed for SMM (p < 0.001, η2 = 0.195) and FMI (p = 0.003, η2 = 0.153), indicating differential changes between groups; with significant improvements observed only in the MCEI group. SMI showed no significant interaction effect (p = 0.270, η2 = 0.021), whereas no significant interactions were found for MMSE, MoCA, or AFT (p ≥ 0.18, η2 ≤ 0.03).

Conclusion:

A 24-week community-based multicomponent exercise program safely increased skeletal muscle mass and reduced fat mass in older adults with MCI, but did not produce measurable improvements on screening-level cognitive measures. Future studies with longer duration, larger samples, and inclusion of cognitive challenges are warranted to clarify exercise–cognition interactions and establish dose–response relationships for both body composition and domain-specific cognition.

Clinical trial registration:

Identifier ChiCTR2000035012.

Introduction

China is among the fastest-aging countries in the world, with the prevalence of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in adults aged 65 years and above reaching approximately 19% (Shi et al., 2022). Aging itself represents the strongest non-modifiable risk factor for late-life cognitive decline and neurodegenerative diseases. As an intermediate stage between normal aging and dementia, MCI significantly increases the risk of progression to Alzheimer’s disease (Busse et al., 2003; Ravaglia et al., 2008), adversely affects quality of life in older adults (Khan et al., 2023), and imposes substantial economic and caregiving burdens on families and society (Teveles, 2023). In the persistent absence of effective pharmacological interventions capable of halting cognitive decline, identifying safe and scalable strategies to preserve cognitive and brain health in older adults has become an urgent priority (Luo et al., 2021).

Among various intervention strategies, non-pharmacological approaches have emerged as central methods for enhancing cognitive function in older adults. These strategies can be broadly categorized into three groups: (1) physical exercise, (2) cognitive training, and (3) social engagement (Silva et al., 2024; Venegas-Sanabria et al., 2020). Physical exercise has received particular attention due to its multi-target, multi-system benefits. Accumulating evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses indicates that regular exercise not only improves cardiometabolic and physical health but also enhances cerebral perfusion, elevates brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels, mitigates chronic neuroinflammation, and subsequently benefits memory, attention, and global cognitive function (Falck et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2022; Mielniczek and Aune, 2024; Titus et al., 2021; Ruiz-González et al., 2021). In contrast, cognitive training primarily yields domain-specific gains (Chan et al., 2024; Cabreira et al., 2024), whereas social engagement largely contributes to emotional and psychosocial well-being (Li et al., 2024). Collectively, physical exercise is considered one of the most cost-effective non-pharmacological strategies to promote healthy aging.

Recently, multicomponent exercise intervention (MCEI) and cognitive–physical combined training have gained increasing attention (Rieker et al., 2022; Meng et al., 2021). These programs typically integrate aerobic, resistance, and balance exercises with varying levels of cognitive challenge. Previous studies have suggested that such comprehensive interventions may confer broad cognitive benefits in older adults, including older adults with MCI, potentially improving attention, memory, executive functions (EFs), and daily functional abilities (Li et al., 2025; Lai et al., 2025; Chen et al., 2023). Attention, executive functions, and related cognitive domains are among the areas most likely to benefit, although the extent of improvement can vary across studies.

Despite promising findings, several limitations remain in the current literature. First, many intervention trials are relatively short (typically ≤12 weeks), limiting the ability to assess the long-term effects of exercise on cognition and body composition. Second, while body composition indicators—such as skeletal muscle mass and fat mass—serve as important markers of physical and metabolic health in older adults, most studies focus predominantly on cognitive outcomes, often overlooking body composition despite its relevance to cognitive aging. Third, long-term, community-based randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that simultaneously assess cognitive function and body composition in older adults remain scarce.

To address these gaps, the present study implemented a 24-week community-based MCEI randomized controlled trial (RCT) to examine whether a multicomponent exercise intervention could simultaneously improve cognitive function and body composition in older adults with MCI. We hypothesized that participants in the intervention group would show greater improvements than those in a usual-activity control group.

Methods

Study design and ethics

This single-center, community-based RCT was conducted in accordance with the SPIRIT 2013 statement and reported following the CONSORT 2025 guidelines. The trial was led by West China Hospital, Sichuan University, and implemented in two urban communities in Chengdu. A parallel-group design was used, in which eligible participants were randomly allocated (1:1) to either the MCEI group or the usual activity control (UAC) group. The 24-week intervention consisted of three 60 min supervised MCEI sessions per week, while the UAC group maintained habitual activities and attended weekly health education sessions. No interim assessments were conducted; a comprehensive endpoint evaluation was performed within 1 week after the intervention (December 1–7, 2023) by trained, blinded assessors. Participants remained unaware of group allocation. To ensure consistency, all exercise and assessment sessions were scheduled at the same time of day (08:00–10:00). Participants were instructed to avoid caffeine, alcohol, and strenuous physical activity for 24 h prior to assessments, consume a standardized light meal 2 h beforehand, and maintain hydration (≥1,500 mL/day), with fluid intake recorded prior to each assessment.

Participants

Sample size

An a priori power analysis (G*Power 3.1, repeated-measures mixed ANOVA, within–between interaction) indicated that a medium effect size of f = 0.25, α = 0.05, and power = 0.80 required a minimum of 34 participants. We enrolled 64 participants (32 per group), yielding an actual power >0.80.

Recruitment and screening

A four-stage recruitment protocol was implemented to maximize 24-week retention by addressing common causes of early dropout and enhancing participants’ engagement.

-

(1) Community outreach: Local health stations and senior-citizen centers collaborated to establish preliminary trust, which reduced immediate post-enrolment withdrawal.

-

(2) Spaced screening: Assessment sessions were scheduled 2–5 days apart to avoid cognitive overload and early dropout due to fatigue.

-

(3) Individualized feedback: Certified geriatricians provided face-to-face feedback to enhance participants’ perceived safety and the value of participation, thereby strengthening commitment.

-

(4) Proactive exclusion of high-risk individuals: The principal investigator integrated medical, logistical, and family-support information to identify and exclude participants with high attrition risk (e.g., transportation or health constraints), keeping expected loss below 5%.

Together, these steps ensured that participants felt safe, supported, and capable of completing the full 24-week intervention.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligibility was based on the 2018 Chinese Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Dementia and Cognitive Impairment (Part V: MCI) and other standardized frameworks (Petersen et al., 2018.).

Inclusion criteria

-

(1) Aged 65–75 years, community-dwelling, with self-reported or clinically confirmed memory complaints.

-

(2) Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) = 0.5, Global Deterioration Scale (GDS) 2–3, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) ≥ 24, Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) ≤ 26, Animal Fluency Test (AFT) ≥ 15, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) ≥ 6, preserved basic activities of daily living.

-

(3) Skeletal Muscle Index (SMI) < 7.0 kg·m−2 (men) or < 5.7 kg·m−2 (women), Skeletal Muscle Mass (SMM) < 26.3 kg (men) or < 18.9 kg (women), Fat Mass Index (FMI) < 7.0 kg·m−2 (men) or < 14.0 kg·m−2 (women).

-

(4) Able to ambulate independently, with moderate-intensity exercise tolerance confirmed by cardiopulmonary exercise testing and Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q).

-

(5) Signed informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Irreversible visual impairment, severe cardio-cerebrovascular or uncontrolled metabolic diseases, participation in structured multicomponent exercise within the past 3 months, or clinical diagnosis of dementia.

Randomization and allocation

A two-stage randomization procedure was employed (Wu et al., 2023):

-

Community-level: Two urban communities served as recruitment sites only and were not used as randomization units.

-

Individual level: Eligible participants from both communities were randomized (1:1) to the MCEI or UAC group using computer-generated variable block sizes (4 and 6), stratified by sex.

The sequence was generated by an independent statistician and stored in a password-protected file. Allocation concealment was maintained until baseline assessments were completed. Participants were not blinded, but outcome assessors and data analysts were.

Ethics approval and consent

All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of West China Hospital, Sichuan University (approval No. 2020-287). The trial was registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2000035012).

Intervention protocol

Multicomponent exercise intervention

A fixed 60 min template was used for all 72 supervised sessions (Mon/Wed/Fri, 08:30–09:30). Table 1 presents a minute-by-minute blueprint for Phase A (Week 3, Monday); identical structure was applied in Phases B and C with progressed loads (see Appendix 1). The minute-by-minute blueprint for Phase A (Week-3, Monday); identical structure was applied in Phases B & C with progressed loads detailed in Appendix 1.

Table 1

| Time (min) | Sequence & load | HR/RPE | Rest | Safety notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 00–02 | BP & HR screen | – | – | Abnormal→seated track |

| 02–10 | Warm-up | 50% HRmax | 30 s | Non-slip floor; 2 m spacing |

| 10–25 | Block A-Baduanjin | 55% HRmax | 30 s water | Tablet flashes if >80 %HRmax |

| 25–37 | Block B-Resistance | RPE 11–12 | 45 s intra | Auto “half-set” after3fails |

| 37–45 | Block C-Balance | ≤60% HRmax | 30 s walk | Fall: stop-ice-report ≤24 h |

| 45–53 | Cool-down | ≤50% HRmax | – | Photo taken; missing |

| 53–60 | Hydration, RPE | – | – | Upload within 24 h |

Example 60-minute session blueprint (Phase A, Week-3, Monday).

Target HR zones 50–75% HRmax; intra-set rest 45 s, between-set 60s; real-time HR monitored at 1 Hz.

Intensity progression (see Appendix 1 for full tables)

Load increased every 4 weeks: +1 kg dumbbell or medicine ball, upper HR ceiling 75% HRmax. Three consecutive full-set failures → automatic “half-set”; two consecutive “half-set” sessions triggered individual reassessment.

Time feasibility

Pilot runs (12 older adults × 3 sessions) showed the main exercise block was completed in 46.8 ± 1.2 min; total 8 min warm-up + 47 min main + 5 min cool-down fits exactly 60 min without compression.

Safety measures beyond ACSM guidelines

-

(1) Pre-session health checklist and accident insurance coverage.

-

(2) AED and first-aid kit on site; instructors certified in first aid.

-

(3) Real-time HR alert at 80% HRmax; automatic load reduction or extra rest.

-

(4) Post-session “three-in-one” e-package (QR sign-in, HR.csv, de-identified photo); missing components supplemented within 24 h.

Fidelity and adherence audit

20% of sessions were randomly audited using a 19-item checklist (α = 0.88); mean score 94.3% (SD 3.1). Adherence was defined as ≥58/72 sessions (80%) meeting “on-target” criteria (≥20 min within prescribed HR zone + full 60 min attendance). Weekly SMS feedback was sent to participants.

Usual activity control group

Participants in the UAC group continued their regular daily activities and attended weekly 1 h health education sessions for 24 weeks. Educational content was prepared by the project team, with printed handouts distributed. During the pilot phase, experts in medicine and exercise science delivered in-person guidance, ensuring engagement without structured physical training.

Outcome assessments

All assessments were conducted at baseline and within 1 week post-intervention under standardized conditions by trained, blinded assessors.

Cognitive testing was performed individually in a quiet room by two certified neuropsychologists:

-

(1) MMSE: Assesses global cognition, including orientation, registration, attention, calculation, recall, language, and visuospatial skills.

-

(2) MoCA: Evaluates multiple cognitive domains, including EFs, attention, abstraction, and visuospatial abilities through tasks such as trail-making, cube and clock drawing. A score ≤26 indicates MCI.

-

(3) AFT: Measures semantic memory and verbal processing speed by counting the number of animals named within 90 s.

-

(4) IADL: Assesses functional ability across seven complex daily tasks that require executive function and memory application.

Body composition was assessed with the InBody 770 multi-frequency BIA after ≥ 8 h fasting, emptied bladder, removal of metal, full limb-electrode contact, daily calibration (impedance error <1%), room temperature 23 ± 1 C.

Heart rate monitoring

Heart rate (HR) was continuously monitored during each MCEI session using Huawei Band 6 (1 Hz sampling). Data were exported to determine time spent in target HR zones.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

Primary outcomes included MMSE, MoCA, SMM, and FMI. Interrelationships among these indicators were also explored.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes comprised AFT, IADL, SMI, and BMR. Interrelationships among these variables were similarly examined.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). An intention-to-treat (ITT) approach was adopted, retaining participants with at least one post-baseline assessment and imputing missing values using the last-observation-carried-forward (LOCF) method. A per-protocol (PP) sensitivity analysis (attendance ≥ 80%) was also conducted to verify robustness. Outliers were identified using the box-plot method (1.5 × IQR) and Winsorized to the nearest non-outlier value. Normality was assessed via Shapiro–Wilk tests, and homogeneity of variances using Levene’s test. Baseline characteristics were compared between groups using independent-samples t-tests (for normally distributed data) or Mann–Whitney U tests (for non-normal data), while categorical variables were analyzed using χ2 tests. For primary and secondary outcomes, a 2 (Group) × 2 (Time) repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted using Type-III sums of squares. The assumption of sphericity was automatically met given the two measurement points. Partial eta-squared (η2) was reported for main and interaction effects, and Cohen’s d (calculated using pooled baseline SD) was provided for change scores. Following significant interactions, post-hoc pairwise comparisons were performed with a Bonferroni correction. All tests were two-tailed, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05 (Figure 1).

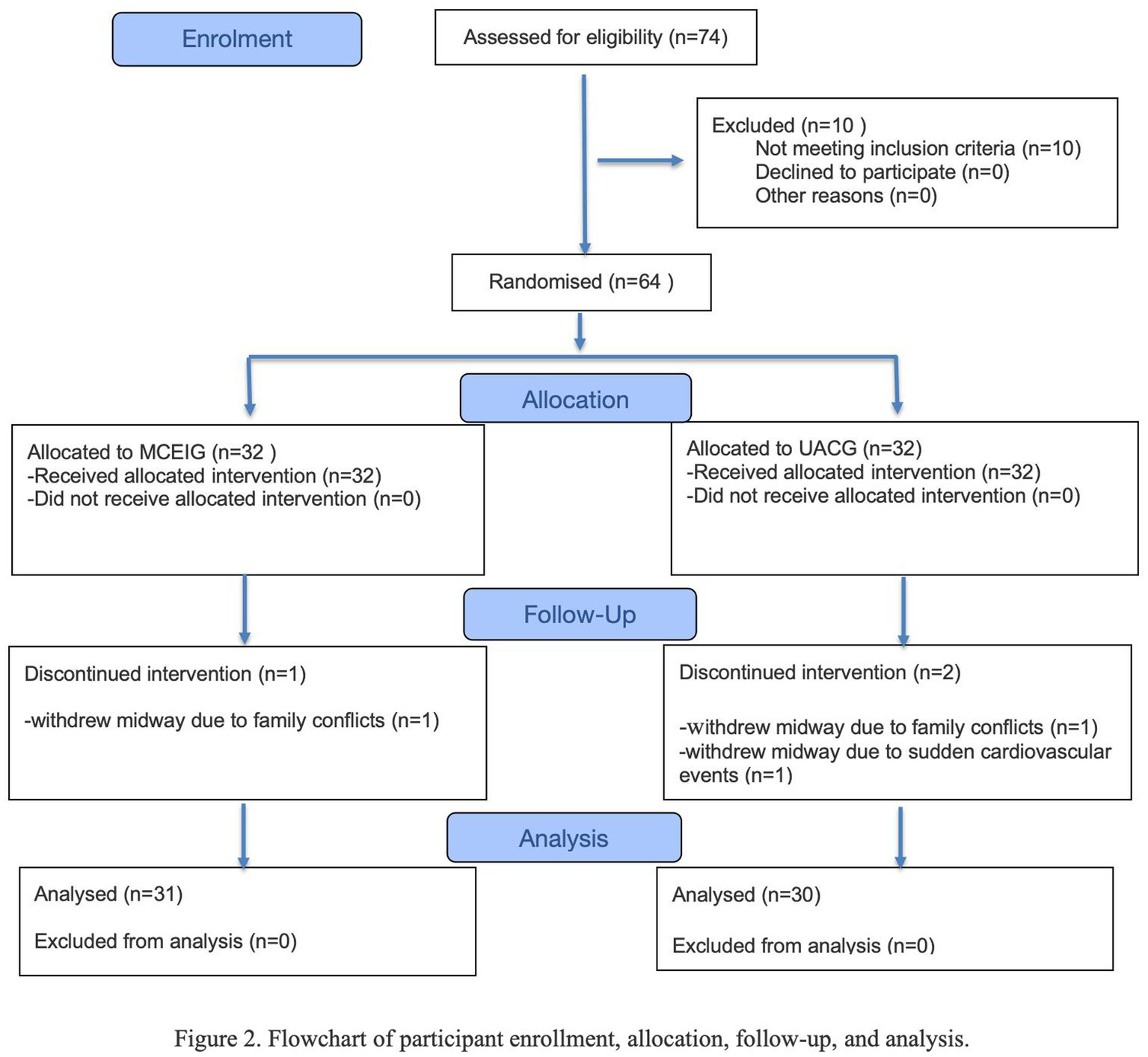

Figure 1

Study flowchart. Flow of participants through the study, including recruitment, screening, randomization, intervention, and assessment phases. MCEI, multi-component exercise intervention; UAC, usual activity control.

Result

CONSORT diagram

Figure 2 shows that 95.3% of participants (61/64) completed the endpoint assessment; three withdrawals occurred for family conflicts (n = 2) or acute cardiovascular events (n = 1).

Figure 2

Flowchart of participant enrollment, allocation, follow-up, and analysis.

Baseline characteristics of the study population

Table 2 summarizes baseline demographics and key variables. No significant between-group differences were observed in age, sex distribution, height, weight, BMI, MMSE, MoCA, AFT, IADL, SMI, SMM, FMI, or BMR (all p > 0.05), indicating successful randomization.

Table 2

| Variable | All participants (n = 61) | MCEIG (n = 31) | UACG (n = 30) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 68.49 (4.4) | 68.63 (5.31) | 69.37 (4.44) | 0.540 |

| Gender (%) | ||||

| Male | 19 (31.1) | 9 (29.00) | 10 (33.30) | 0.716 |

| Female | 41 (68.9) | 22 (71.00) | 20 (66.70) | |

| Mean (SD) Height (cm) | ||||

| Male | 162.90 (4.8) | 162.26 (5.91) | 163.56 (4.04) | 0.620 |

| Female | 152.30 (4.4) | 153.07 (3.72) | 151.50 (5.15) | 0.289 |

| Mean (SD) Weight (Kg) | ||||

| Male | 63.65 (7.74) | 61.98 (7.89) | 64.50 (7.86) | 0.570 |

| Female | 55.45 (6.86) | 56.51 (7.86) | 54.63 (6.02) | 0.391 |

| Mean (SD) BMI (kg/m) | ||||

| Male | 23.98 (2.81) | 23.51 (2.30) | 24.4 (3.27) | 0.639 |

| Female | 23.87 (2.40) | 23.96 (2.71) | 23.77 (2.06) | 0.645 |

| Mean (SD) cognitive function indicators | ||||

| MMSE Score (/30) | 26.85 (2.10) | 26.90 (2.50) | 26.80 (1.63) | 0.913 |

| MoCA score (/30) | 20.38 (3.48) | 20.77 (3.64) | 20.07 (3.38) | 0.504 |

| AFT score | 26.26 (5.25) | 27.03 (6.15) | 25.47 (4.08) | 0.28 |

| IADL (/8) | 7.54 (0.99) | 7.52 (0.96) | 7.57 (1.04) | 0.783 |

| Mean (SD) body composition indicators | ||||

| SMI (kg·m⁻2) | 5.83 (0.60) | 5.84 (0.64) | 5.82 (0.58) | 0.759 |

| SMM (kg) | 19.32 (2.82) | 19.20 (2.88) | 19.44 (2.82) | 0.879 |

| FMI (kg·m⁻2) | 9.05 (1.62) | 8.89 (1.96) | 9.13 (1.21) | 0.591 |

| BMR (kcal·day⁻1) | 1246.43 (136.4) | 1266.26 (140.25) | 1225.93 (131.67) | 0.261 |

Baseline characteristics of participants.

Data are presented as number (percentage) of participants unless otherwise specified. MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; IADL, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; AFT, Animal Fluency Test; SMI, Skeletal Muscle Mass Index; SMM, Skeletal Muscle Mass; FMI, Fat Mass Index; BMR, Basal Metabolic Rate; SD, Standard Deviation; p value, the result of statistical hypothesis testing, indicating whether the observed differences are statistically significant.

Impact of the 24-week multi-component exercise program on primary outcomes

The results revealed a statistically significant Group × Time interaction effect for SMM (F(1, 59) = 12.08, p ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.166). Simple effects analysis indicated that the exercise group exhibited a significant pre-to-post difference in SMM (F(1, 59) = 14.32, p ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.195), whereas no significant change was observed in the control group (F(1, 59) = 0.21, p = 0.65, η2 = 0.004). Furthermore, post-intervention SMM in the exercise group was significantly higher than that in the control group (F(1, 59) = 5.92, p = 0.018, η2 = 0.091).

Similarly, for FMI, a significant Group × Time interaction was found (F(1, 59) = 9.89, p = 0.003, η2 = 0.140). Simple effects analysis showed a significant pre -to-post difference in FMI in the exercise group (F(1, 59) = 10.67, p = 0.002, η2 = 0.153), but not in the control group (F(1, 59) = 0.15, p = 0.70, η2 = 0.003). Post-intervention FMI was also significantly lower in the exercise group compared to the control group (F(1, 59) = 4.33, p = 0.042, η2 = 0.068) (Tables 3–5).

Table 3

| Overtime measure | Group factor effect | Time factor effect | Group × Time effect | Measure time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| η2 | P-value | η2 | P-value | η2 | P-value | T0 (Pre) | T1 (Post) | |

| MMSE (points) | 0.007 | 0.511 | 0.001 | 0.841 | 0.011 | 0.418 | – | – |

| MCEIG | 26.87 ± 2.54 | 26.53 ± 2.83 | ||||||

| UACG | 26.80 ± 1.63 [0.02] | 27.17 ± 1.58 [0.174] | ||||||

| MoCA (points) | 0.012 | 0.396 | 0.252 | 0.000** | 0.033 | 0.161 | – | – |

| MCEIG | 20.77 ± 3.64 | 22.50 ± 3.66 | ||||||

| UACG | 20.07 ± 3.38 [0.12] | 20.60 ± 3.24 [0.32] | ||||||

| AFT (points) | 0.061 | 0.054 | 0.012 | 0.402 | 0.002 | 0.720 | – | – |

| MCEIG | 26.93 ± 6.23 | 28.07 ± 6.46 | ||||||

| UACG | 25.47 ± 4.07 [0.20] | 25.50 ± 3.95 [0.33] | ||||||

| IADL (points) | 0.006 | 0.552 | 0.020 | 0.281 | 0.002 | 0.730 | – | – |

| MCEIG | 7.50 ± 0.97 | 7.70 ± 0.70 | ||||||

| UACG | 7.57 ± 1.04 [0.05] | 7.53 ± 1.04 [0.15] | ||||||

| SMI (kg·m⁻ 2 ) | 0.020 | 0.283 | 0.179 | 0.001** | 0.021 | 0.270 | – | – |

| MCEIG | 5.84 ± 0.63 | 6.02 ± 0.73 | ||||||

| UACG | 5.82 ± 0.58 [0.06] | 5.91 ± 0.54 [0.13] | ||||||

| SMM (kg) | 0.014 | 0.369 | 0.140 | 0.003* | 0.166 | 0.001** | – | – |

| MCEIG | 19.32 ± 2.85 | 19.99 ± 2.96 | ||||||

| UACG | 19.44 ± 2.82 [0.03] | 19.39 ± 2.70 [0.14] | ||||||

| FMI (kg·m⁻ 2 ) | 0.001 | 0.001** | 0.087 | 0.021* | 0,140 | 0.003* | – | |

| MCEIG | 8.99 ± 1.99 | 8.52 ± 1.70 | ||||||

| UACG | 8.84 ± 1.59 [0.21] | 8.74 ± 1.73 [0.17] | ||||||

| BMR (kcal·day⁻ 1 ) | 0.031 | 0.175 | 0.000 | 0.864 | 0.019 | 0.289 | – | – |

| MCEIG | 1271.23 ± 139.83 | 1283.70 ± 149.24 | ||||||

| UACG | 1225.93 ± 131.67 [0.21] | 1222.50 ± 149.13 [0.2] | ||||||

Impact of the 24-week multi-component exercise program on cognitive and body-composition outcomes at two timepoints (Group × Time) in older adults with MCI (mean ± SD) (N = 61).

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Repeated-measures ANOVA was used to examine the Group×Time interaction, with Group (Intervention vs. Control) as the between-subjects factor and Time (Pre vs. Post) as the within-subjects factor. Ges, generalized eta-squared; P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; Moca, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; AFT, Animal Fluency Test; IADL, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; SMI, Skeletal Muscle Index; SMM, Skeletal Muscle Mass; FMI, Fat Mass Index; BMR, Basal Metabolic Rate; T0, baseline; T1, post-intervention.

Table 4

| Outcome measures | Between-group comparison | T0 | T1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference (95% CI) | t | P value | Difference (95%CI) | t | P-value | ||

| SMI (kg·m⁻2) | MCEIG:UACG | 0.02 (−0.28, 0.32) | 0.15 | 0.882 | 0.09 (0.04, 0.14) | 3.71 | <0.001** |

| SMM (kg) | MCEIG:UACG | −0.24 (−1.45, 0.97) | −0.40 | 0.694 | 0.46 (0.05, 0.87) | 2.21 | 0.032* |

| FMI (kg·m⁻2) | MCEIG:UACG | −0.15 (−0.93, 0.63) | −0.38 | 0.707 | −0.47 (−1.05, 0.11) | −1.59 | 0.118 |

Simple-effect analysis, between-group difference (mean ± SD) (N = 61).

*Indicates significant intra−/inter group differences before/after intervention (p < 0.05);**indicates extremely significant differences (p < 0.01); Cohen’s d (95% CI) = effect size with 95% confidence interval. MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; Moca, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; AFT, Animal Fluency Test; IADL, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; SMI, Skeletal Muscle Index; SMM, Skeletal Muscle Mass; FMI, Fat Mass Index; BMR, Basal Metabolic Rate; T0, baseline; T1, post-intervention.

Table 5

| Outcome measures | MCEIG | UACG | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | P | Difference 95% CI | T | P | Difference 95% CI | |

| SMI (kg·m⁻2) | ||||||

| T0:T1 | −2.961 | 0.006** | 0.53 (−0.28, −0.05) | −2.050 | 0.049* | 0.37 (−0.17, −0.00) |

| SMM (kg) | ||||||

| T0:T1 | −3.521 | 0.001** | 0.63 (−1.02, −0.27) | 0.799 | 0.431 | 0.15 (−0.09, 0.20) |

| FMI (kg·m⁻2) | ||||||

| T0:T1 | 3.364 | 0.002* | 0.60 (0.18, 0.76) | 0.386 | 0.702 | 0.08 (−0.32, 0.48) |

Simple-effect analysis, within-group change (mean ± SD) (N = 61).

*Indicates significant intra−/inter group differences before/after intervention (p < 0.05); ** indicates extremely significant differences (p < 0.01); Cohen’s d (95% CI) = effect size with 95% confidence interval. SMI, Skeletal Muscle Index; SMM, Skeletal Muscle Mass; FMI, Fat Mass Index; BMR, Basal Metabolic Rate; T0, baseline; T1, post-intervention.

Impact of the 24-week multi-component exercise program on secondary outcomes

For SMI, no significant Group × Time interaction was observed (F(1, 59) = 1.21, p = 0.270, η2 = 0.021), whereas a significant main effect of Time was found (F(1, 59) = 12.86, p = 0.001, η2 = 0.179). Simple-effects analysis showed a significant pre-to-post increase in the exercise group (F(1, 59) = 8.77, p = 0.006) and a smaller but significant increase in the control group (F(1, 59) = 4.20, p = 0.049). Between-group comparisons indicated no baseline difference (F(1, 59) = 0.02, p = 0.882) but a significant post-intervention difference favoring exercise (F(1, 59) = 13.76, p < 0.001).

Discussion

The 24-week multicomponent exercise program significantly increased SMM and decreased FMI in community-dwelling older adults with MCI. No Group × Time interaction was observed for MMSE or MoCA total scores; both are screening-level instruments with limited sensitivity to detect subtle cognitive changes (D’Ignazio et al., 2025; Roalf et al., 2012). The negligible between-group difference on the AFT suggests that observed changes were task-specific rather than indicative of broader cognitive improvement. Within-group improvements in MoCA scores should be interpreted cautiously, as they may reflect practice effects or random variation.

Exercise is hypothesized to support cognitive reserve through enhanced neuroplasticity, increased cerebral blood flow, up-regulation of BDNF, and reduced chronic inflammation (Marmeleira, 2013; Cabral et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2025). However, in the present trial, no significant cognitive effects were detected, which aligns with prior studies reporting ceiling effects that can obscure small changes (Baker et al., 2010; Suzuki et al., 2012).

Body-composition changes were intervention-specific. Skeletal muscle acts as an endocrine organ, releasing myokines that may modulate neuroinflammation (Isaac et al., 2011), whereas excess adipose tissue is associated with pro-inflammatory states linked to brain atrophy (Walston, 2012). The present 72-session protocol produced a “muscle-gain, fat-loss” profile exceeding typical fixed-intensity aerobic benchmarks (Djosic et al., 2025) and meeting inflammatory thresholds proposed for MCI cohorts (Cadore et al., 2013; Zhang and Wang, 2021). Minimal changes in the control group indicate that habitual physical activity alone is insufficient to alter SMM or FMI over 24 weeks (Lim et al., 2023), providing dose-reference values for future trials.

This study had several limitations. The absence of a cognitive-only arm precludes quantifying the independent contribution of cognitive stimulation. The over-representation of women may have influenced results through sex-specific social baselines (Wheatley et al., 2021; Rai et al., 2020). The protocol did not include dual-task or cognitive-enrichment components, which may be necessary to elicit broader transfer effects, including potential improvements in executive functions. Future trials could incorporate dual-task challenges or executive function-specific tasks (e.g., Stroop, N-back) to better capture cognitive outcomes beyond screening tools. Additionally, the lack of blood-based biomarkers such as BDNF limits our ability to assess potential neurobiological mechanisms underlying the observed effects, suggesting that future studies should incorporate biomarker measurements to strengthen mechanistic interpretations.

Conclusion

In summary, the 24-week community-based multicomponent exercise program was safe, well-tolerated, and effective in increasing SMM and reducing FMI in older adults with MCI. No significant improvements were observed on screening-level cognitive outcomes (MMSE/MoCA), and AFT changes were task-specific. Future studies should consider three-arm designs (exercise-only, cognitive-only, combined) with dual-task or cognitive-enrichment components to explore exercise-cognition synergies and establish dose–response relationships for both body composition and domain-specific cognitive outcomes. The present 60 min, thrice-weekly, ≥24-week template can be readily implemented in community medical-fitness services, offering a low-cost, scalable approach for managing SMM and FMI in older adults with MCI.

Statements

Data availability statement

The trial protocol and statistical analysis plan presented in this study are available through the following BMC Neurology citation: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-023-03390-5.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Medical Ethics Committee, West China Hospital, Sichuan University No. 37 Guoxue Alley, Chengdu, Sichuan 610041, China. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

DX: Conceptualization, Data curation, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft. XW: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Resources. JD: Investigation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. QL: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Methodology, Software. ZW: Investigation, Validation, Writing – review & editing. YH: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. YZ: Writing – review & editing, Validation. JC: Software, Writing – original draft. BL: Writing – original draft, Visualization. YD: Writing – original draft, Validation. YT: Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by the National Key Technologies R&D Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China [grant numbers 2022YFC3602300 and 2022YFC3602303] and the Project of Max Cynader Academy of Brain Workstation, West China Hospital, Sichuan University [grant number 21 HXYS19005].

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the participants and on-site staff for their dedicated efforts in completing the assessments and intervention tasks. Additionally, we are deeply thankful to West China Hospital, Sichuan University (WCHSCU) for providing comprehensive support, including research data and technical assistance, which has been instrumental in the successful conduct of this study.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. During the preparation of this work, the authors used DeepSeek solely for language refinement (approximately 10–15% of the total text). All scientific content, data interpretation, statistical reporting, and final decisions regarding wording were produced and verified by the authors, who take full responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnagi.2025.1711554/full#supplementary-material

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- AFT

Animal Fluency Test

- aMCI

amnestic mild cognitive impairment

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- BMR

basal metabolic rate

- CDR

Clinical Dementia Rating

- CONSORT

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

- FMI

fat-mass index

- GDS-15

Geriatric Depression Scale-15

- HRmax

maximum heart rate

- IADL

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

- MCEI

multicomponent exercise intervention

- MCI

mild cognitive impairment

- MMSE

Mini-Mental State Examination

- MoCA

Montreal Cognitive Assessment

- PAR-Q

Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire

- PI

principal investigator

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- RM

repetition maximum

- RPE

rating of perceived exertion

- SMI

skeletal muscle index

- SMM

skeletal muscle mass

- STAI

State–Trait Anxiety Inventory

- UAC

usual activity control

Glossary

References

1

Baker L. D. Frank L. L. Foster-Schubert K. Green P. S. Wilkinson C. W. et al . (2010). Effects of aerobic exercise on mild cognitive impairment. Arch. Neurol.67, 71–79. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.307,

2

Busse A. Bischkopf J. Riedel-Heller S. G. Angermeyer M. C. (2003). Mild cognitive impairment: prevalence and incidence according to different diagnostic criteria: results of the Leipzig longitudinal study of the aged (LEILA75+). Br. J. Psychiatry182, 449–454. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.5.449,

3

Cabral D. F. Rice J. Morris T. P. Rundek T. Pascual-Leone A. Gomes-Osman J. (2019). Exercise for brain health: an investigation into the underlying mechanisms guided by dose. Neurotherapeutics16, 580–599. doi: 10.1007/s13311-019-00749-w,

4

Cabreira V. Wilkinson T. Frostholm L. Stone J. Carson A. (2024). Systematic review and meta-analysis of standalone digital interventions for cognitive symptoms in people without dementia. NPJ Digit. Med.7:278. doi: 10.1038/s41746-024-01280-9,

5

Cadore E. L. Rodriguez-Manas L. Sinclair A. Izquierdo M. (2013). Effects of different exercise interventions on risk of falls, gait ability, and balance in physically frail older adults: a systematic review. Rejuvenation Res.16, 105–114. doi: 10.1089/rej.2012.1397,

6

Chan A. T. C. Ip R. T. F. Tran J. Y. S. Chan J. Y. C. Tsoi K. K. F. (2024). Computerized cognitive training for memory functions in mild cognitive impairment or dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. NPJ Digit. Med.7:1. doi: 10.1038/s41746-023-00987-5,

7

Chen Y. L. Tseng C. H. Lin H. T. Wu P. Y. Chao H. C. (2023). Dual-task multicomponent exercise–cognitive intervention improved cognitive function and functional fitness in older adults. Aging Clin. Exp. Res.35, 1855–1863. doi: 10.1007/s40520-023-02481-0,

8

D’Ignazio G. Carlucci L. Sergi M. R. Palumbo R. Dattilo L. Terrei M. et al . (2025). Is the MMSE enough for MCI? A narrative review of the usefulness of the MMSE. Front. Psychol.16:1727738. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1727738,

9

Djosic A. Zrnic R. Zivkovic D. Purenovic-Ivanovic T. Zivkovic M. Cokorilo N. et al . (2025). Effects of a combined exercise program on body mass, BMI and body composition of elderly women. Is twice a week good enough?Int. J. Morphol.43, 591–599. doi: 10.4067/S0717-95022025000200591,

10

Falck R. S. Davis J. C. Best J. R. Crockett R. A. Liu-Ambrose T. (2019). Impact of exercise training on physical and cognitive function among older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurobiol. Aging79, 119–130. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2019.03.007,

11

Isaac V. Sim S. Zheng H. Zagorodnov V. Tai E. S. Chee M. (2011). Adverse associations between visceral adiposity, brain structure, and cognitive performance in healthy elderly. Front. Aging Neurosci.3:12. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2011.00012,

12

Khan F. M. Fatima M. Qasim S. M. Khan J. T. Saeed A. Shamsi R. F. (2023). Quality of life in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Found. Univ. J. Rehabil. Sci.3, 9–13. doi: 10.33897/fujrs.v3i1.297

13

Lai X. Zhu H. Cai Y. Chen B. Li Y. Du H. et al . (2025). Effects of exercise-cognitive dual-task training on cognitive frailty in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Front. Aging Neurosci.17:1639245. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2025.1639245,

14

Li A. Qiang W. Li J. Geng Y. Qiang Y. Zhao J. (2025). Effectiveness of an exergame-based training program on physical and cognitive function in older adults with cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled trial in rural China. BMC Geriatr.25:892. doi: 10.1186/s12877-025-06341-6,

15

Li Q. Xie Y. Lin J. Li M. Gu Z. Xin T. et al . (2024). Microglia sing the prelude of Neuroinflammation-associated depression. Mol. Neurobiol.62, 5311–5332. doi: 10.1007/s12035-024-04575-w,

16

Lim C. L. Keong N. L. S. Yap M. M. C. Tan A. W. K. Tan C. H. Lim W. S. (2023). The effects of community-based exercise modalities and volume on musculoskeletal health and functions in elderly people. Front. Physiol.14:1227502. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2023.1227502,

17

Luo Y. Su B. Zheng X. (2021). Trends and challenges for population and health during population aging—China, 2015–2050. China CDC Wkly3, 593–598. doi: 10.46234/ccdcw2021.158,

18

Marmeleira J. (2013). An examination of the mechanisms underlying the effects of physical activity on brain and cognition: a review with implications for research. Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. Act.10, 83–94. doi: 10.1007/s11556-012-0105-5

19

Meng Q. Yin H. Wang S. Shang B. Meng X. Yan M. et al . (2021). The effect of combined cognitive intervention and physical exercise on cognitive function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Aging Clin. Exp. Res.34, 261–276. doi: 10.1007/s40520-021-01877-0,

20

Mielniczek M. Aune T. K. (2024). The effect of high-intensity interval training (HIIT) on brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels (BNDF): a systematic review. Brain Sci.15:34. doi: 10.3390/brainsci15010034,

21

Petersen R. C. Lopez O. Armstrong M. J. Getchius T. S. Ganguli M. Gloss D. et al . (2018). Practice guideline update summary: mild cognitive impairment: report of the guideline development, dissemination, and implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of neurology. Neurology90:126. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004826

22

Rai R. Jongenelis M. I. Jackson B. Newton R. U. Pettigrew S. (2020). Factors influencing physical activity participation among older people with low activity levels. Ageing Soc.40, 2593–2613. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X1900076X

23

Ravaglia G. Forti P. Montesi F. Lucicesare A. Pisacane N. Rietti E. et al . (2008). Mild cognitive impairment: epidemiology and dementia risk in an elderly Italian population. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc.56, 51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01503.x,

24

Rieker J. A. Reales J. M. Muiños M. Ballesteros S. (2022). The effects of combined cognitive-physical interventions on cognitive functioning in healthy older adults: a systematic review and multilevel Meta-analysis. Front. Hum. Neurosci.16:838968. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2022.838968,

25

Roalf D. R. Moberg P. J. Xie S. X. Wolk D. A. Moelter S. T. Arnold S. E. (2012). Comparative accuracies of two common screening instruments for classification of Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment, and healthy aging. Alzheimers Dement.9, 529–537. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.10.001,

26

Ruiz-González D. Hernández-Martínez A. Valenzuela P. L. Morales J. S. Soriano-Maldonado A. (2021). Effects of physical exercise on plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor in neurodegenerative disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev.128, 394–405. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.05.025,

27

Shi L. Yao S. Wang W. (2022). Prevalence and distribution trends of mild cognitive impairment among Chinese older adults: a meta-analysis. Chin. Gen. Pract.25:109. doi: 10.12114/j.issn.1007-9572.2021.00.31

28

Silva N. C. B. S. Barha C. K. Erickson K. I. Kramer A. F. Liu-Ambrose T. (2024). Physical exercise, cognition, and brain health in aging. Trends Neurosci.47, 402–417. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2024.04.004,

29

Suzuki T. Shimada H. Makizako H. Doi T. Yoshida D. Tsutsumimoto K. et al . (2012). Effects of multicomponent exercise on cognitive function in older adults with amnestic mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Neurol.12:128. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-12-128,

30

Teveles M. (2023). The economic impact of mild cognitive impairment: a comprehensive review. Available online at: https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4581150.

31

Titus J. Bray N. W. Kamkar N. Camicioli R. Nagamatsu L. S. Speechley M. et al . (2021). The role of physical exercise in modulating peripheral inflammatory and neurotrophic biomarkers in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mech. Ageing Dev.194:111431. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2021.111431,

32

Venegas-Sanabria L. C. Martínez-Vizcaino V. Cavero-Redondo I. Chavarro-Carvajal D. A. Cano-Gutierrez C. A. Álvarez-Bueno C. (2020). Effect of physical activity on cognitive domains in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Aging Ment. Health25, 1977–1985. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2020.1839862

33

Walston J. D. (2012). Sarcopenia in older adults. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol.24, 623–627. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328358d59b,

34

Wang M. Hua Y. Bai Y. (2025). A review of the application of exercise intervention on improving cognition in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: mechanisms and clinical studies. Rev. Neurosci.36, 1–25. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2024-0046,

35

Wheatley C. Glogowska M. Stathi A. Sexton C. Johansen-Berg H. Mackay C. (2021). Exploring the public health potential of RED January, a social media campaign supporting physical activity in the community for mental health: a qualitative study. Ment. Health Phys. Act.21:100429. doi: 10.1016/j.mhpa.2021.100429,

36

Wu X. Zhang T. Tu Y. Deng X. Sigen A. Li Y. et al . (2023). Multidomain interventions for non-pharmacological enhancement (MINE) program in Chinese older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a multicenter randomized controlled trial protocol. BMC Neurol.23:341. doi: 10.1186/s12883-023-03390-5,

37

Zhang R. L. Wang X. (2021). Effect of different modes of exercise on sarcopenia in older adults: a meta-analysis. Chin. J. Rehabil. Theory Pract.27, 1291–1298. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-9771.2021.11.008

38

Zhou B. Wang Z. Zhu L. Huang G. Li B. Chen C. et al . (2022). Effects of different physical activities on brain-derived neurotrophic factor: a systematic review and bayesian network meta-analysis. Front. Aging Neurosci.14:981002. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.981002,

Summary

Keywords

body composition, cognitive function, multicomponent exercise intervention, randomized controlled trial (RCT), skeletal muscle mass

Citation

Xu D, Wu X, Dai J, Li Q, Wang Z, Huang Y, Zhang Y, Cao J, Li B, Dong Y and Tu Y (2026) A 24-week multi-component exercise program improves cognition and body composition in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled trial. Front. Aging Neurosci. 17:1711554. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2025.1711554

Received

23 September 2025

Revised

02 December 2025

Accepted

15 December 2025

Published

12 January 2026

Volume

17 - 2025

Edited by

Bruce Alan Watkins, University of California, Davis, United States

Reviewed by

Soledad Ballesteros, National University of Distance Education (UNED), Spain

Mingyuan Jia, Qingdao University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Xu, Wu, Dai, Li, Wang, Huang, Zhang, Cao, Li, Dong and Tu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yanhao Tu, phcemb@gmail.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.