- 1Laboratory of Extremophile Plants, Centre of Biotechnology of Borj-Cedria, Hammam-Lif, Tunisia

- 2Faculty of Sciences of Tunis, University of Tunis El Manar, Tunis, Tunisia

- 3Plant Stress Tolerance Laboratory, University of Mpumalanga, Mbombela, South Africa

- 4Department of Sciences, Institute for Multidisciplinary Research in Applied Biology, Public University of Navarre, Pamplona, Spain

- 5Department of Science and Innovation - National Research Foundation (DSI-NRF) Centre of Excellence in Food Security, University of the Western Cape, Bellville, South Africa

Introduction: Intercropping has emerged as a promising strategy to enhance crop performance and resilience under conditions of abiotic stress. Medicago sativa and Hordeum marinum constitute a potentially complementary forage system for semi-arid regions, yet their integrated physiological and metabolic responses to combined water and nutrient limitations remain poorly characterized. This study evaluated whether intercropping could improve productivity, nutrient acquisition, and biochemical stress adaptation under drought and reduced fertilization.

Methods: A controlled greenhouse experiment was conducted to compare monocropping and intercropping systems of M. sativa and H. marinum under drought (40% field capacity) and three fertilization regimes (0%, 50%, and 100% of nutrient demand). Plants were harvested at three successive growth stages. Biomass production, mineral ion profiles (Na⁺, Ca²⁺, Cl⁻, NO₃⁻), and metabolite signatures: including carbohydrates, organic acids, and amino acids, were quantified to assess stress responses and resource-use efficiency.

Results: Biomass production was significantly influenced by cultivation system, fertilization level, and their interaction, with intercropping consistently enhancing productivity across all harvests. Ion profiling revealed distinct nutrient redistribution in intercropped plants, particularly in H. marinum, which accumulated higher Cl⁻ and NO₃⁻ in leaves and greater Ca²⁺ and Na⁺ in roots. Metabolomic analyses showed that intercropping under nutrient deficiency promoted the accumulation of stress-mitigating metabolites, including raffinose, fructose, sucrose, citric acid, succinic acid, oxalic acid, proline, GABA, and glutamine, reflecting improved osmotic regulation and energy metabolism.

Discussion: The integrative physiological and biochemical adjustments induced by intercropping resulted in enhanced nutrient uptake, stronger osmotic balance, and more efficient metabolic functioning under stress. These synergistic responses explain the superior biomass performance and resilience of both species under drought and low fertilization. Intercropping M. sativa with H. marinum thus represents a robust, low-input strategy for sustainable forage production in semi-arid environments.

1 Introduction

Desertification poses a significant threat to sustainable agriculture in arid regions (AbdelRahman, 2023) like Tunisia, where rainfall has sharply declined, with only 138.19 mm recorded in 2022 compared to the historical average of 271.48 mm (Trading Economics, 2024). This drastic reduction disrupts agroecosystems and creates challenges such us declining soil fertility (Kirkby, 2021). As a result, nutrient deficiencies arises in crops, limiting their growth and yields, which ultimately threatens food security (Gebrehiwot, 2022), and increases dependence on imports in countries like Tunisia. For instance, Tunisia imported large quantities of alfalfa in 2022 to compensate for its poor harvest.

To counter declining crop productivity in arid regions, experts have proposed several strategies, among which intercropping systems stand out as one of the most sustainable and promising approaches (Amanullah et al., 2020; Yin et al., 2020; Ashoori et al., 2021; Abbasi and Sepaskhah, 2022). This agricultural practice involves growing two or more crops simultaneously in the same field, aiming to optimize resource utilization and enhance overall yield (Guerchi et al., 2024). In arid zones, where water stress and soil fertility are major concerns, intercropping has the potential to revolutionize farming practices and contribute to food security (Guerchi et al., 2023).

Intercropping has shown substantial improvements in resource use efficiency (Stomph et al., 2020). A study on maize-soybean intercropping revealed that the intercropped maize had a radiation use efficiency of 5.2 g MJ-1 and water use efficiency of 16.2 kg ha-1 mm-1 compared to lower values in other configurations (Raza et al., 2022). This study also reported that, land and water equivalent ratios in intercropping systems ranged from 1.22 to 1.55, indicating improved land and water use efficiencies (Raza et al., 2022).

Choosing compatible crops is essential for successful intercropping in arid regions. Legume–cereal pairings are particularly effective, with chickpea–wheat (Dong et al., 2018; Kherif et al., 2021), lentil–wheat (Koskey et al., 2022), and pea–wheat (Pankou et al., 2022) among the well-documented successful combinations. This type of combination has consistently led to higher wheat yields when compared to wheat grown in monoculture. The increase in yield is largely attributed to the nitrogen-enriching properties of the legumes in the soil. Oilseed-legume intercropping, when managed appropriately, has been shown to be a viable strategy for sustainable crop production and improving soil fertility, particularly in low-input systems (Dowling et al., 2023). Maize grown with oilseed rape (Xing et al., 2023) or with potato (Xie et al., 2021) has demonstrated significant yield advantages, primarily due to the complementarity in the crops’ growth periods.

Legumes, being less competitive in nitrogen uptake compared to other plants, can fix atmospheric nitrogen through their root nodules, potentially contributing up to 15% of the nitrogen needed by an intercropped cereal (Kumar et al., 2020; Jensen et al., 2020; Rodriguez et al., 2020). In maize-alfalfa intercropping systems, for example, the presence of alfalfa has been shown to increase the amount of nitrogen in the soil and enhance nutrient uptake by maize crops (Nasar et al., 2022).

Metabolomics provides a powerful approach to explore how plants adjust their biochemical machinery under stress and interspecific interactions. In fact, intercropping has been shown to reshape both rhizospheric and plant metabolomes. For example, in maize–pepper intercropping, shifts in root exudates such as flavonoids and alkaloids were associated with altered microbial communities and nutrient cycling (Chen et al., 2024). In pea–tea intercropping, notable alterations in primary metabolites, particularly amino acids, were observed, which were linked to the regulation of several amino acid metabolism-related genes (Ma et al., 2022). Similarly, a study by Tang et al. (2024) showed that sugarcane–peanut intercropping promoted the release of soluble sugars, organic acids, amino acids, and phenolic acids from peanut roots, thereby enhancing the activity of acid phosphatases, urease, and catalase in the rhizosphere soil. These findings highlight that intercropping not only affects growth and nutrient dynamics but also regulates metabolic pathways involved in stress resilience.

Leguminous plants are commonly chosen for intercropping in agricultural systems. For example, intercropping soybean with tea can regulate both amino acid and secondary metabolite levels in tea leaves, while also increasing the total nitrogen content in the soil of a tea garden (Duan et al., 2019, 2021; Li et al., 2024). Similarly, intercropping peanut with sugarcane enhances soil organic carbon and nutrient availability, and influences soil enzymatic activity at various depths, notably boosting the activity of acid phosphatase, protease, and sucrose (Tang et al., 2024).

Given the crucial role of the plant metabolome in stress response and productivity, we hypothesize that intercropping, particularly under nutrient-limited conditions; can enhance the metabolic profile of plants like Medicago sativa (alfalfa) and Hordeum marinum (sea barley). By facilitating more efficient resource use and promoting beneficial plant interactions, intercropping may boost metabolite production, improving plant resilience and overall growth in arid environments. However, there is still limited understanding of how these species interact when grown together and how intercropping affects their growth, dry matter allocation, competition, and metabolic profiles.

This study seeks to investigate how varying nutrient supply levels within intercropping systems influence the metabolic responses of these two species. The findings could provide valuable insights into optimizing agricultural practices in regions facing water scarcity and nutrient limitations, potentially improving crop productivity and sustainability in challenging environments.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant material

In this study, we utilized the Gabes 2355 variety of Medicago sativa (alfalfa) and the Kl4 line of Hordeum marinum (sea barley). Gabes 2355, a product of a Tunisian breeding program, is recognized for its ability to thrive in saline environments and is widely cultivated in Southern Tunisia (Jabri et al., 2021). Alfalfa is typically planted in April and harvested up to three times annually (Guerchi et al., 2024). The Kl4 line of Hordeum marinum was sourced from the saline region of Sebkhet El Kalbia in Kairouan, central Tunisia. This line, developed over two generations of self-pollination at the Centre of Biotechnology of Borj-Cedria (CBBC), exhibits a high degree of homozygosity, reflecting the self-pollinating nature of H. marinum (Saoudi et al., 2017, 2019). The distinct growth patterns of alfalfa and sea barley allow for efficient resource use, including light, water, and nutrients, due to their temporal and spatial complementarity.

2.2 Growth conditions and experimental design

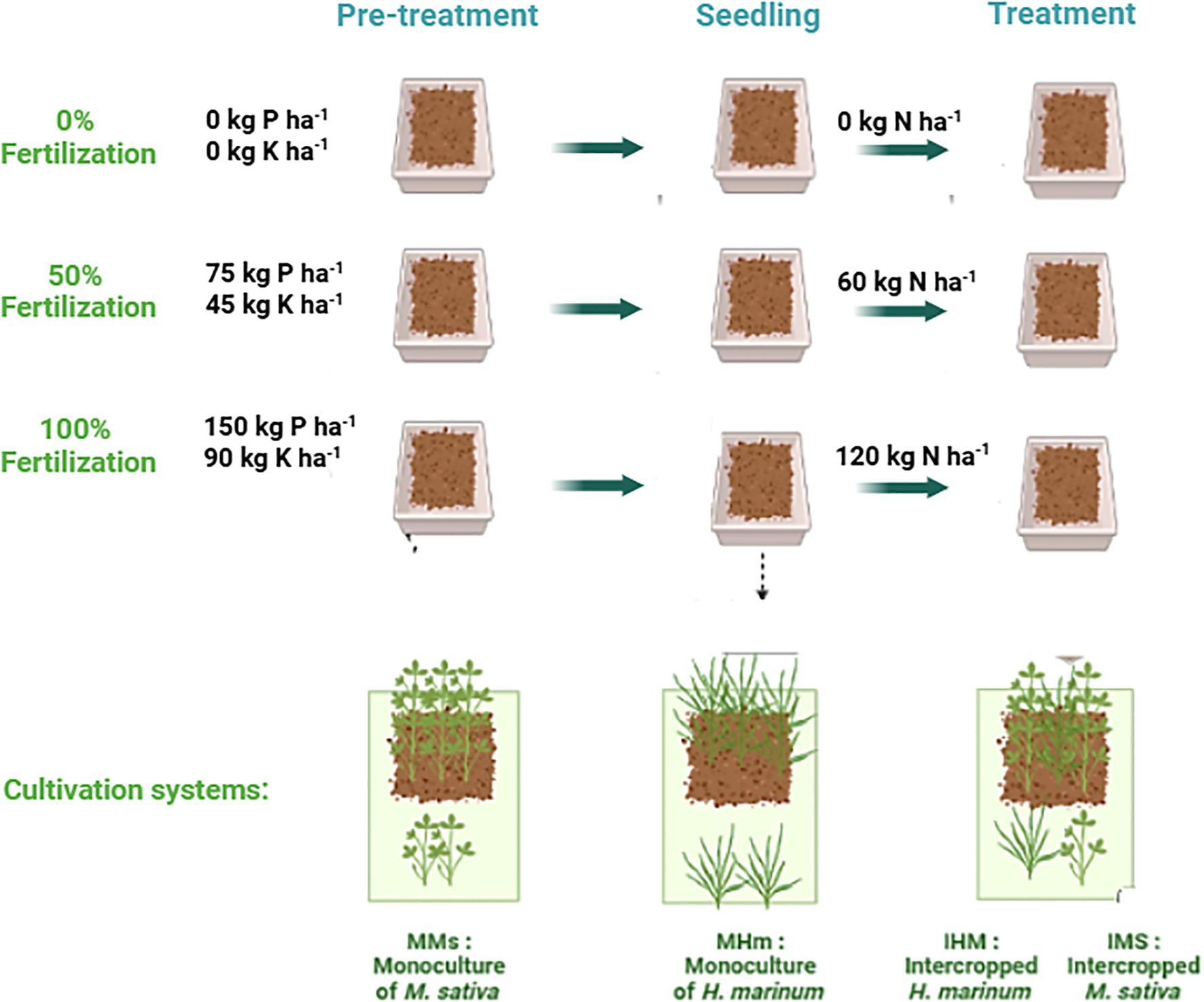

Prior to planting, soil analysis showed a pH of 7.5, available phosphorus of 3.08 ppm, total nitrogen of 0.1%, and exchangeable potassium of 130 ppm. According to standard agronomic thresholds, these values correspond to very low phosphorus (<10 ppm), low nitrogen (≤0.1%), and low potassium (100–150 ppm). Fertilizer treatments were therefore designed to correct these deficiencies and to evaluate plant responses under nutrient limitation. Soil was amended with phosphorus and potassium at three fertilizer levels: nutrient deficiency as 0% fertilization (0 kg P ha−¹, 0 kg K ha−¹), 50% of fertilization (75 kg P ha−¹, 45 kg K ha−¹), and optimum condition as 100% fertilization (150 kg P ha−¹, 90 kg K ha−¹) (Figure 1). Phosphorus was applied as monoammonium phosphate (52% P2O5) and potassium as potassium chloride, with rates selected based on local soil test results and regional alfalfa production guidelines.

Figure 1. Experimental design showing the three fertilization levels of phosphorus, potassium and nitrogen: 0% (0 kg P ha−¹, 0 kg K ha−¹, 0 kg N ha−¹), 50% (75 kg P ha−¹, 45 kg K ha−¹, 60 kg N ha−¹), and 100% (150 kg P ha−¹, 90 kg K ha−¹, 120 kg N ha−¹). Seedlings were planted in a greenhouse under two cropping systems: monoculture for each species Medicago sativa (MMs) and Hordeum marinum (MHm) and intercropping of M. sativa (IMs) with H. marinum (IHm).

Seed germination was initiated by placing the seeds on filter paper saturated with distilled water in Petri dishes, which were incubated in the dark at 25°C. After germination, seedlings were transplanted into 50-liter plastic boxes (61.5 cm × 39.5 cm × 33 cm) filled with 46 kg of meadow soil. In both monocropping and intercropping systems, plants were established in pots with a spacing of 5 cm between rows and 7 cm between plants within each row. In the intercropping treatment, rows of M. sativa and H. marinum were alternated within the same pot to ensure uniform distribution and equal access to growth space.

Each 50-liter box contained 15 plants, arranged in four cultivation modes: i) monoculture of M. sativa, ii) monoculture of H. marinum, iii) M. sativa in parallel intercropping, and iv) H. marinum in parallel intercropping. The intercropping setup consisted of one row of H. marinum (5 plants) intercropped with two rows of M. sativa (10 plants), with 5 cm spacing within rows and clear separation between species.

One week after planting, three nitrogen regimes were applied: nutrient deficiency (0 kg N ha−¹), 50% of fertilization (60 kg N ha−¹), and control (120 kg N ha−¹). Nitrogen was applied in the form of urea to minimize NH3 volatilization. The amount of fertilizer applied per box was calculated from the recommended field dose (kg ha−¹). Specifically, the field dose was first converted to g m−² and then scaled to the box surface area (0.243 m²). Since plant performance under partial (50%) and control fertilization was comparable in the intercropping system at the first harvest, all subsequent metabolic and nutrient‐uptake analyses focused on the nutrient deficiency and partial fertilization (50%) treatments.

The experiment included three replicates for each cultivation method and treatment, totaling 27 boxes. Plants were irrigated every two days with water equivalent to 40% of the container capacity. The water availability level of 40% container capacity was chosen to simulate semi-arid conditions, which are characterized by limited water availability and frequent drought stress.

The study was conducted at the Centre of Biotechnology Borj-Cedria (CBBC) in Tunisia, located at 36°41′13″ N latitude and 10°22′55″ E longitude, 70 meters above sea level. This coastal region with a semi-arid climate has an average annual rainfall of 450 mm and a mean annual temperature of 18.6°C (Oueslati et al., 2024). The controlled glass-covered environment ensured no interference from rainfall or other external factors, with the experiment running from March to July 2023.

We evaluated three forage harvest timings, conducting each harvest at the onset of the earing stage for H. marinum. Simultaneously, the harvest for M. sativa was performed at the same growth stage, following the guidelines by Guerchi et al. (2024). The first harvest took place three months after sowing, at the end of May, followed by the second and third harvests at monthly intervals, at the end of June and the end of July, respectively.

Biomass yield was measured post-harvest by cutting the plants approximately 5 cm above ground level. After harvesting, plants were separated for morphological trait analysis under different treatments. The plants were uprooted, and the soil around the roots was washed away. They were then divided into root and leaf samples.

The fresh weight of the aerial parts and roots was recorded, and the samples were dried at 60°C for 48 hours in a Memmert UN55 oven (Germany). The dry matter content of the leaves and roots was subsequently determined. At the last harvest, for metabolic analyses, samples from each box were collected, lyophilized, and stored at -20°C until further analysis.

2.3 Determination of soluble sugars and starch content

The extraction of soluble sugars was carried out as outlined in Castañeda et al. (2019). Lyophilized root and leaf samples (20 mg and 40 mg, respectively) were subjected to extraction three times with 1 mL of 80% (v/v) boiling ethanol for 30 seconds, followed by a final extraction at room temperature. The combined supernatants were evaporated to dryness in a Turbovap® LV Evaporator (Zymark, Hopkinton, MA, USA) at 40°C and 1.2 bar pressure. The dried residues were reconstituted in 1 mL of deionized water through a two-step process, with 10 minutes of ultrasonication between steps. Subsequently, the reconstituted solution was centrifuged at 2300 g for 10 minutes at 4°C, and the supernatants were stored at −20°C for later analysis.

The remaining tissue, after extracting ethanol-soluble compounds, was transferred to an oven and dried at 70°C for 24 hours. The dried pellet was then weighed and resuspended in 5 mL of water. The suspension was boiled at 100°C to break the starch grains and then allowed to cool to room temperature. Subsequently, a desalted amyloglucosidase solution (EC 3.2.1.3, 0.5 units/mL acetate buffer, pH 4.5) was added to each tube. The tubes were incubated with shaking at 55°C for 12 hours to digest the starch. After incubation, the samples were centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 5 minutes, and the supernatant was collected for further glucose analysis (Gálvez et al., 2005).

Sucrose, fructose, and glucose levels were quantified using ionic chromatography on a 940 Professional IC Vario Metrohm system, equipped with Metrosep Carb2 guard and Metrosep Carb2 150/4.0 columns, operating at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min, at 30°C, using 300 mM NaOH and 1 mM sodium acetate as the mobile phase (Calleja-Satrustegui et al., 2025).

2.4 Ions level determination

Lyophilized samples (approximately 20 mg of roots and 40 mg of leaves) were ground into a fine powder using a mortar and pestle in liquid nitrogen. The resulting powder was homogenized in 1 mL of ultrapure deionized distilled water (DDW) and heated at 90°C for 30 minutes. After heating, the homogenate was filtered using a 0.45 µm filter. Ion levels were measured using ion chromatography on a 940 Professional IC Vario 2, Metrohm. Cations were analyzed through Metrosep C6 150/4.0 Metrohm column (0.9 ml/min; 45°C; HNO3 1.76 mM, picolinic acid 1.7 mM), while anions were analyzed using Metrosep A Supp7 150/4.0 Metrohm column (0.7 ml/min; 45°C; Na2CO3 3.6 mM) following the manufacturer’s protocols.

2.5 Determination of free amino acids and organic acids

Lyophilized samples (approximately 20 mg of root and 40 mg of leaves) were ground into powder under liquid nitrogen and then homogenized using a mortar and pestle. The extraction of free amino acids will be carried out in methanol/water/chloroform extracts (Hacham et al., 2002). Each ground sample was vortexed five times for 15 seconds in a cold water: chloroform: methanol (3:5:12 v/v) solution and incubated on ice for 10 minutes. The extracts were then centrifuged at 1200 rpm and 4°C for 2 minutes. The supernatant was collected in a 2 ml tube, and the pellet was resuspended in 600 μl of the water: chloroform: methanol solution. This mixture was centrifuged again for 2 minutes at 1200 rpm and 4°C. The supernatant was collected and combined with the previous supernatant. To this combined supernatant, 300 μl of chloroform and 450 μl of water were added. The mixture was centrifuged at maximum speed for 2 minutes. The upper phase (water: methanol) was collected and transferred to a new tube, then evaporated in a vacuum centrifuge.

The dry residue was dissolved in distilled water and stored at –80 °C until analysis. Organic acids were quantified by ion chromatography using a 940 Professional IC Vario system (Metrohm) equipped with a Metrosep A Supp16 150/4.0 column, operated at 1 mL min⁻¹ and 55 °C, and employing a gradient of 20 mM Na₂CO₃, 300 mM NaOH, and water. Detection was performed using a conductivity detector. For amino acid analysis, the samples underwent derivatization using 1 mM FITC dissolved in acetone at room temperature for 15 hours in a 20 mM borate buffer (pH 10). The content of free amino acids was measured using a Sciex MDQ+ (AB Sciex LLC, MA, EE.UU.) equipped with laser-induced fluorescence detection as described by Arlt et al. (2001) Takizawa and Nakamura (1998).

2.6 Statistical analysis

The study’s data were subjected to a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to identify significant interactions between cropping mode and variables related to crop performance or metabolomic analysis. Only those variables showing significant interactions were selected for further detailed statistical examination. To compare the means, the Duncan test was applied at a 5% significance level. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software, version 20.0.

3 Results

3.1 Impact of cultivation mode on biomass traits and nutrient uptake of M. sativa and H. marinum under different fertilization levels

Leaf and root ion concentrations showed clear species- and treatment-specific patterns. In leaves, Hordeum marinum (MHm) accumulated higher Cl− and Na+ than Medicago sativa (MMs) under both fertilized (Cl−: 17.88 vs 9.89; Na+: 19.71 vs 13.25) and unfertilized conditions (Cl−: 15.01 vs 2.98; Na+: 18.11 vs 17.26), reflecting MHm’s salt-tolerant nature. In contrast, MMs leaves had higher K+ and Ca²+, particularly under fertilization (K+: 13.25; Ca²+: 35.11), indicating efficient nutrient assimilation. Intercropping further enhanced nutrient uptake, with IMs and IHm leaves showing higher NO3− (IMs: 0.; IHm: 0.18) and PO4³− (IMs: 2.69; IHm: 3.52) compared to monocrops. In roots, MHm maintained higher Cl− and Na+ (fertilized IHm: Cl− 12.19, Na+ 5.3), while MMs roots contained higher PO4³− (fertilized MMs: 3.16) and stable K+, suggesting complementary nutrient strategies. Fertilization amplified these differences, particularly for NO3−, PO4³−, and Mg²+ (IHm roots Mg²+ 8.09), highlighting the combined effects of nutrient supply and interspecific interactions (Table 1).

Table 1. Nutrient content (ion concentration expressed as mg·g−¹ dry weight) in the leaves and roots of Medicago sativa and Hordeum marinum grown under monoculture (MMs, MMh) and intercropping (IMs, IMh) systems at two fertilization levels (0% and 50%).

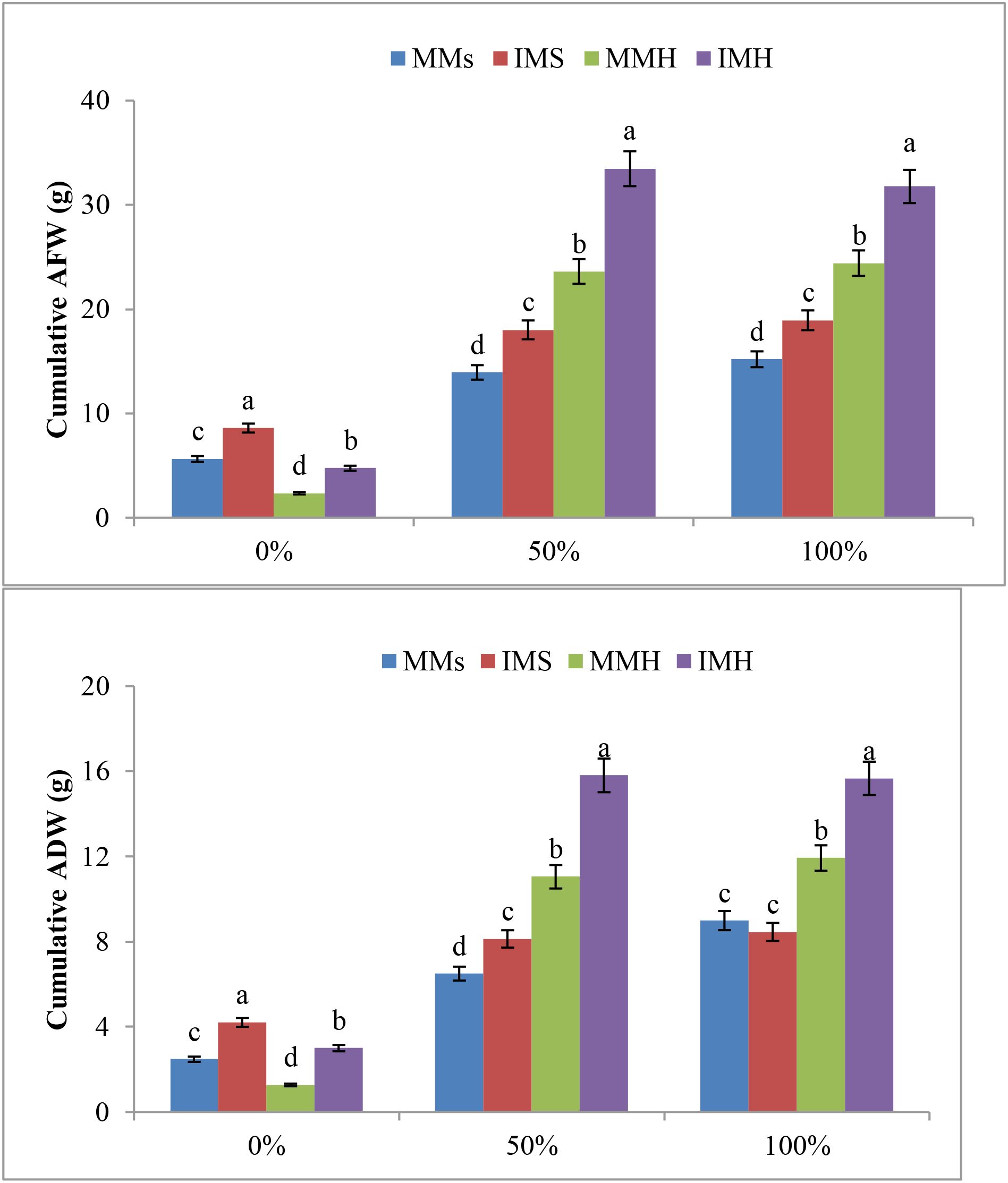

Biomass accumulation reflected these nutrient patterns. Cumulative aerial dry weight (ADW) significantly differed among cropping systems and fertilization levels (Figure 2). Under non-fertilized conditions (0%), M. sativa in intercropping (IMS, 4.0 g plant−¹) accumulated more biomass than its monocrop (MMs, 3.0 g plant−¹), while H. marinum in intercropping (IMH, 5.2 g plant−¹) outperformed its monocrop (MMH, 2.0 g plant−¹). At 50% fertilization, ADW markedly increased across treatments, with IMH exhibiting the highest biomass (15.9 g plant−¹), followed by MMH (11.3 g plant−¹), IMS (8.4 g plant−¹), and MMs (7.0 g plant−¹). Compared to monocropping, intercropping enhanced biomass by approximately 35% for M. sativa and 40% for H. marinum. Under 100% fertilization, IMH maintained the highest cumulative ADW (15.8 g plant−¹), whereas MMH, IMS, and MMs reached 12.0, 8.5, and 8.8 g plant−¹, respectively. Despite the increase in biomass with fertilization, the relative gain between 50% and 100% was limited, suggesting that moderate fertilization (50%) was sufficient to sustain optimal growth within the intercropping system.

Figure 2. Cumulative aerial fresh weight (AFW, g plant−¹) and aerial dry weight (ADW, g plant−¹) of Medicago sativa (MMs, IMS) and Hordeum marinum (MMH, IMH) under different fertilization levels (0%, 50%, and 100%). Error bars represent standard error (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences according to Duncan’s test (P ≤ 0.05).

Overall, ANOVA confirmed that intercropping and fertilization significantly influenced ion homeostasis and biomass production (Supplementary Tables S1, S2). These findings demonstrate that intercropping improved resource use efficiency and nutrient acquisition, particularly under moderate fertilization (50%), enhancing growth and stress resilience in the M. sativa–H. marinum association.

3.2 Effect of intercropping on carbohydrate content in M. sativa and H. marinum under different fertilization levels

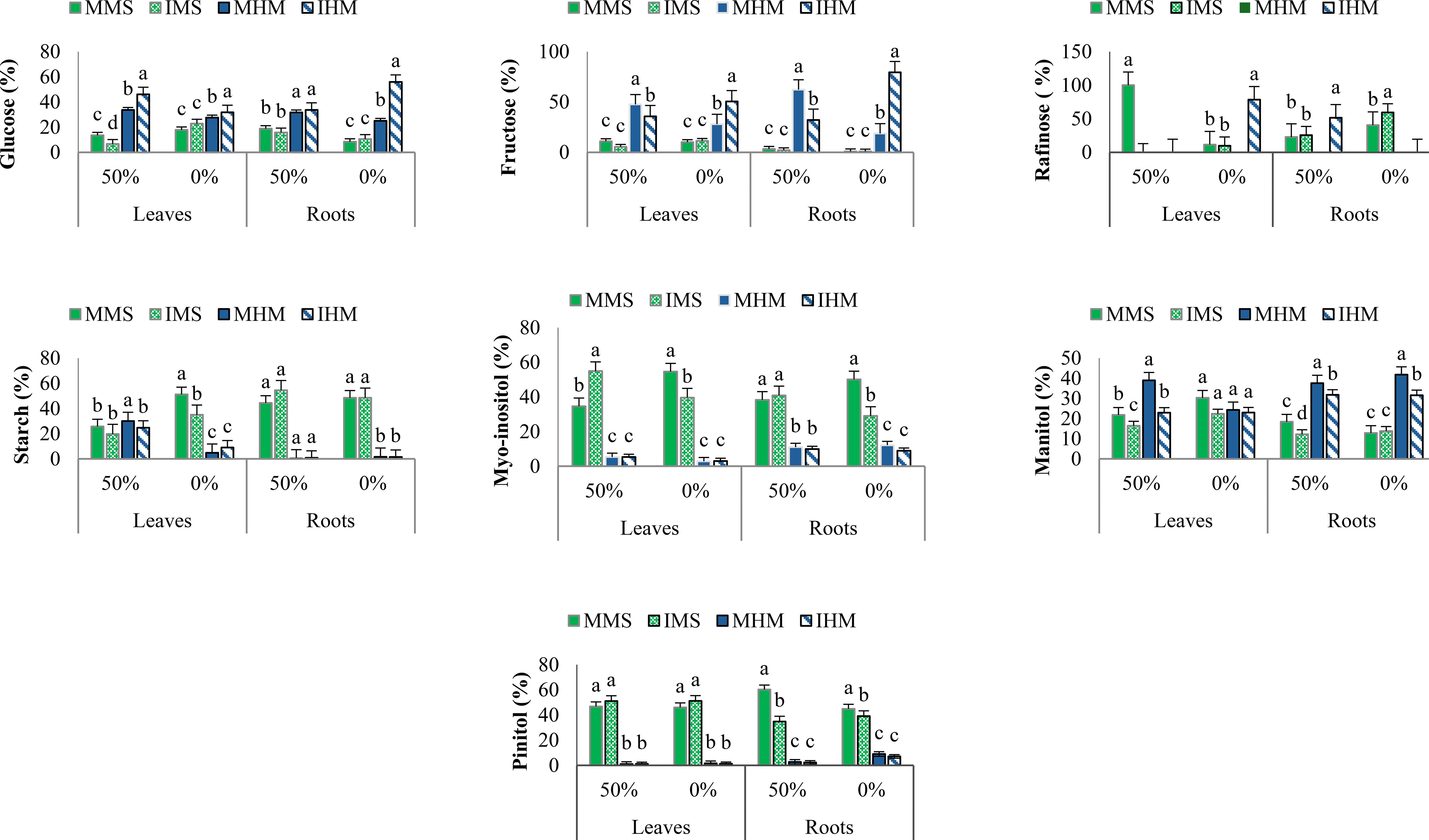

Carbohydrate analyses revealed distinct accumulation patterns in Medicago sativa and Hordeum marinum under varying nutritional regimes and cropping systems.

In M. sativa leaves, intercropping under nutrient deficiency significantly enhanced the accumulation of key osmoprotectants and soluble sugars. Myo-inositol increased to 12.38 µmol/g DW under stressed intercropping, compared to 8.09 µmol/g in fertilized monocropping. Sorbitol rose by 76.5%, while glucose and fructose increased by 6.2% and 99.9%, respectively, compared to intercropping in control. Notably, sucrose remained high across all intercropping conditions. In the roots of M. sativa, intercropping buffered the negative effects of low nutrition. Although myo-inositol and pinitol declined under stress, their levels were better preserved in intercropping than in monocropping. Mannitol showed a slight increase, and sucrose peaked at 200.37 µmol/g DW under intercropping with fertilization significantly higher than in all monocropping conditions. Interestingly, starch accumulation reached 463.66 µmol/g DW under low-intercropping, suggesting improved energy storage capacity under stress (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Carbohydrate concentration profiles (%) under 0% and 50% fertilization conditions across different cultivation systems. Values represent mean ± SE (n = 3 biological replicates). Letters denote significant differences (Duncan’s test, p ≤ 0.05).

In H. marinum leaves, intercropping under stress induced strong accumulation of stress-related sugars. Trehalose increased 9-fold (from 0.17 to 1.65 µmol/g), and raffinose was newly detected at 21.74 µmol/g. Fructose and mannitol increased by 81.1% and 35.1%, respectively, compared to stressed monocropping. In roots, H. marinum under intercropping in stressed condition exhibited the highest levels of glucose (148.0%), fructose (102.7%), and sucrose (42.0%) compared to fertilized condition. Raffinose, absent in control conditions, accumulated under low-intercropping, supporting its role in stress tolerance (Figure 3).

According to the two-way ANOVA (Supplementary Table S3), these trends were statistically supported, with significant interaction effects among species, organ, and treatment. This confirms that the observed changes reflect species-specific metabolic adjustments to intercropping under varying nutritional conditions.

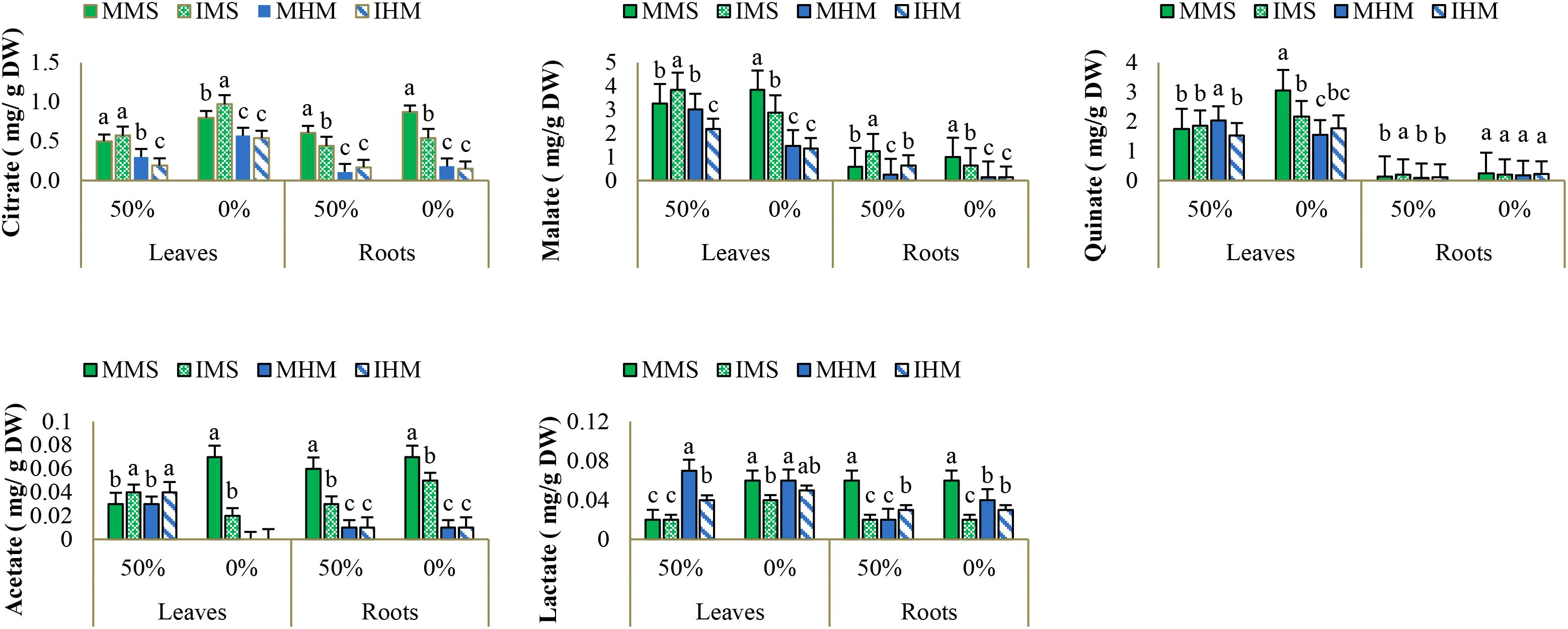

3.3 Effect of intercropping on organic acid distribution in M. sativa and H. marinum under different fertilization levels

Organic acid profiles revealed marked modulation of key metabolic intermediates in response to intercropping and nutrient availabilityIn M. sativa leaves, intercropping with no fertilization significantly boosted citric acid (64.5% vs. fertilized-monocropping; 64.5% vs. unfertilized-intercropping) and succinic acid (66.7% vs. low-monocropping). Malic acid remained stable under intercropping but declined under monocropping. These patterns suggest that intercropping supports energy metabolism and osmotic regulation during stress. In roots, citric acid levels were 40.1% higher under unfertilized-intercropping than in unfertilized-monocropping and only 13.9% lower than in fertilized-intercropping. Succinic acid rose by 87.7%, and oxalic acid by 88.2%, suggesting enhanced ion balance and TCA cycle activity under nutrient deficiency (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Organic acids concentration (mg/g DW) under 0% and 50% fertilization conditions across different cultivation systems: [monoculture of M. sativa (MMs), monoculture of H. marinum (MHm), and M. sativa in intercropping (IMs), and H. marinum in intercropping (IHm)]. Data are shown as mean ± SE (n = 3 biological replicates). Different letters denote significant differences (Duncan’s test, P ≤ 0.05).

In H. marinum leaves, stressed intercropping induced increases in citric acid (55.4%), succinic acid (121.7%), and malic acid (60.7%) compared to stressed monocropping. These compounds are central to energy generation and stress resilience. In roots, intercropping led to higher levels of citric acid (36.4%), succinic acid (77.6%), and oxalic acid (63.5%) when no fertilizer was added compared to stressed monocropping. Compared to intercropping with fertilization, levels declined modestly (14% to 18%), indicating metabolic stability under stress. Overall, intercropping maintained organic acid profiles that support both energy metabolism and detoxification (Figure 4).

According to the two-way ANOVA (Supplementary Table S4), these metabolic shifts were statistically significant, with strong interaction effects among species, organ, and treatment, confirming that intercropping and nutrient availability jointly shape organic acid metabolism in both species.

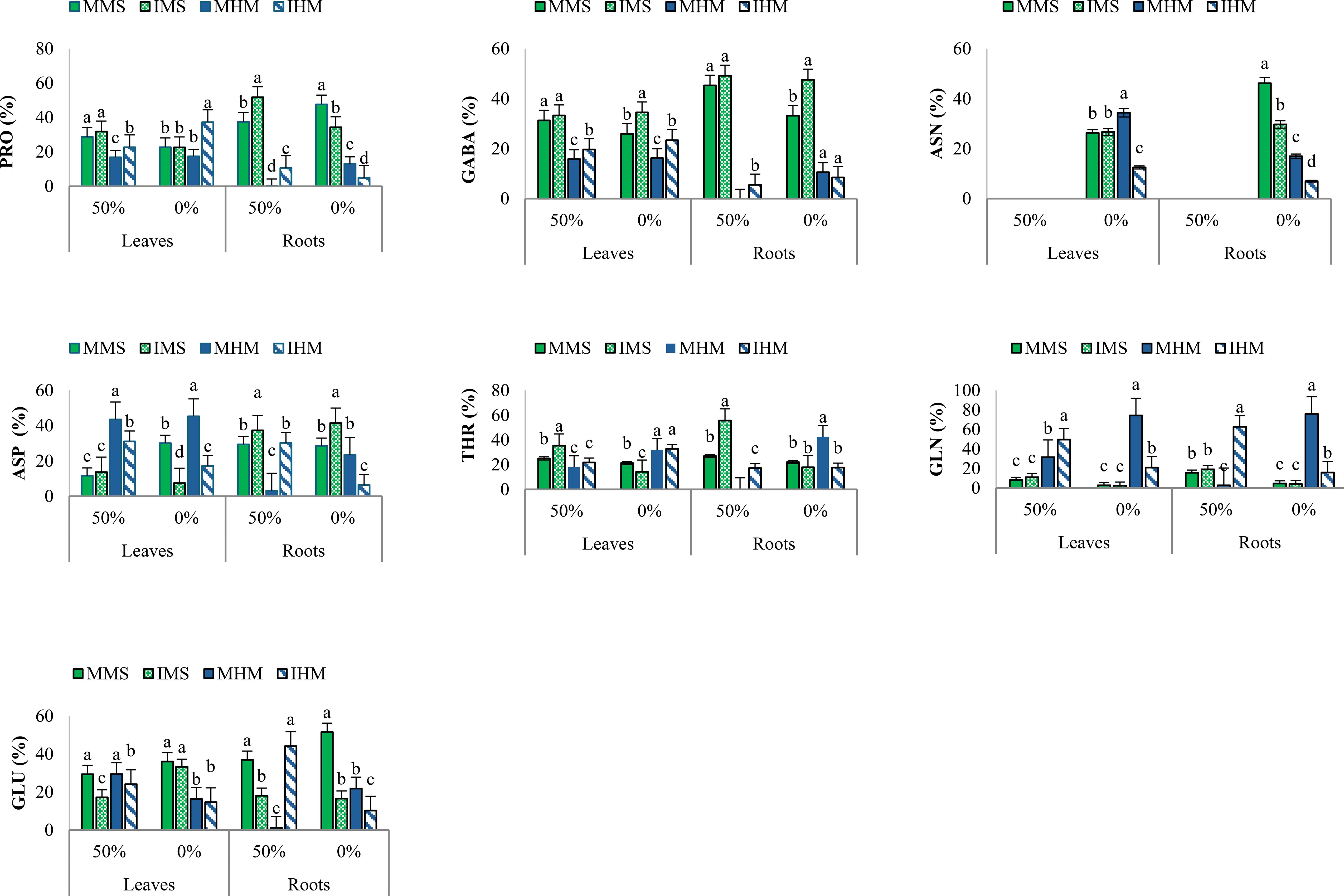

3.4 Effect of intercropping on amino-acid distribution in M. sativa and H. marinum under different fertilization levels

Amino acid analysis showed that intercropping modulates nitrogen and stress-related metabolism depending on species, organ, and nutritional status.

In M. sativa leaves, intercropping with no fertilization increased proline by 59.4% compared to fertilized intercropping, underlining its osmoprotective function. GABA rose by 33.3% and glutamine by 28.6% compared to stressed monocropping, whereas glutamic acid declined by 17.2%, indicating nitrogen flux toward protective metabolism. In roots, intercropping sustained GABA (44.9%) and glutamine (35.2%) under stress. Aspartic acid decreased under stressed monocropping (18.5%) but remained stable with intercropping, demonstrating a stabilizing effect of intercropping on amino acid balance under stress (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Amino acids concentration (%) under 0% and 50% fertilization conditions across different cultivation systems: (monoculture of M. sativa (MMs), monoculture of H. marinum (MHm), and M. sativa in intercropping (IMs), and H. marinum in intercropping (IHm)) Data represent mean ± SE (n = 3 biological replicates). Letters indicate significant differences (Duncan’s test, p ≤ 0.05).

In H. marinum leaves, proline increased by 77.8% (vs. fertilized-monocropping), GABA by 51.4%, glutamine by 60.0%, and aspartic acid by 42.9% under unfertilized-intercropping. These responses suggest enhanced nitrogen redistribution and osmoprotection. In roots, arginine increased by 64.3%, GABA by 55.6%, and glutamine by 46.2% under unfertilized-intercropping vs. unfertilized-monocropping (Figure 5).

According to the two-way ANOVA (Supplementary Table S5), these patterns were statistically significant, with strong interaction effects among species, organ, and treatment, confirming that amino acid metabolism was tightly regulated by both intercropping and nutrient regime.

4 Discussion

The results demonstrated that intercropping significantly influenced biomass accumulation, nutrient uptake, and primary metabolic adjustments in both M. sativa and H. marinum, particularly under nutrient-deficient conditions.

4.1 Impact of cultivation mode on biomass traits and nutrient uptake of M. sativa and H. marinum under different nutrient supplement

Our result showed that the intercropping system consistently produced greater biomass yields, regardless of the treatment applied, highlighting a synergistic interaction between alfalfa and sea barley. The increase in cumulative dry biomass, under optimal intercropping, underscores the complementary resource use between M. sativa and H. marinum (Guerchi et al., 2024). Legume–grass mixtures often enhance overall productivity through resource partitioning and stress buffering (Tang et al., 2021; Salinas-Roco et al., 2024). Legumes such as alfalfa fix atmospheric N2 and exude organic acids and protons that mobilize soil phosphorus, thereby improving soil fertility for companion cereals (Tang et al., 2021). For example, wheat–legume intercrops achieve higher nitrogen accumulation and land‐equivalent ratios under low-N than high-N regimes (Salinas-Roco et al., 2024), and wheat–chickpea mixtures in Mediterranean climates boost wheat yield over monocultures (Kherif et al., 2021). Meta analyses further confirm that cereal–legume systems generally outperform monocultures, especially when nutrients are scarce (Rodriguez et al., 2020). This beneficial effect of intercropping was also reflected in enhanced nutrient uptake in both species. Under mixed cropping, leaves and roots accumulated higher concentrations of NO3−, SO4²−, and Cl−, indicating improved nutrient acquisition process and root-soil interactions. For example, H. marinum roots under low-nutrient intercropping showed notably greater SO4²− and Cl− levels, suggesting that its ion absorption mechanisms are stimulated by proximity to M. sativa (Ma et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2022). Its extensive root system and prolonged lifecycle likely amplify these effects by increasing root contact with nutrient zones (Wang et al., 2020). Similarly, M. sativa in intercrops took up more NO3−, NH4+, and Mg²+ which are critical elements for symbiotic nitrogen fixation and photosynthesis (Zhu et al., 2020; Ahmed et al., 2023). Intercropping also alters the rhizosphere: root-released enzymes (e.g., acid phosphatase, phytase) and organic acids mobilize phosphorus and other minerals, boosting soil and plant nutrient levels (Wang et al., 2014; Tang et al., 2022). Under fertilization, sea barley in the intercrop accumulated more NH4+ and K+, reflecting effective nitrogen transfer from alfalfa and enhanced uptake by the cereal partner (Latati et al., 2014). In line with these results, wheat–soybean and alfalfa–maize intercropping studies report higher N content and uptake in both crops when adequately fertilized (Betencourt et al., 2012; Nasar et al., 2020).

4.2 Effect of intercropping on carbohydrate abundance in M. sativa and H. marinum under different nutrient supplement

These nutritional improvements were accompanied by significant shifts in carbohydrate metabolism, highlighting enhanced osmoprotection and stress buffering (Abid et al., 2016). Under low-N monoculture, M. sativa leaves accumulated large starch reserves (up to ~235 mg g−¹ DW), indicating a carbon sink when growth is limited. In contrast, intercropped alfalfa stored less starch and maintained higher levels of soluble sugars (glucose, fructose, sucrose) and sugar alcohols (myo-inositol, pinitol). This shift suggests that intercropped alfalfa sustained active metabolism using sugars to fuel growth and N assimilation instead of sequestering carbon as starch (Sun et al., 2002). H. marinum showed the opposite pattern: under low N, intercropping increased leaf starch (from ~22 to 41 mg g−¹ DW) and hexose pools, reflecting enhanced carbon fixation when supplied with legume-derived N (Chapagain and Riseman, 2014). Carbohydrate profiling further underscored this metabolic synergy. Under nutrient limitation, alfalfa intercrops exhibited 6–100% increases in soluble sugars and sugar alcohols, enhancing osmoprotection and redox balance (Afzal et al., 2021). In contrast, sea barley accumulated additional starch and hexoses, an energy reserve enabled by the extra N provided by the legume (Amoah et al., 2012). Comparable responses have been documented in other intercropping systems: peanut roots exude more soluble sugars under sugarcane/peanut intercropping (Tang et al., 2024), and same for Bletilla striata when plant alongside companion plants, it build up extra sugars and amino acids that fuel growth and support vital metabolic processes, which not only boost their growth but also make them tougher and more productive (Deng et al., 2023). Same for intercropping Urochloa spp. and Megathyrsus maximus with soybean it positively influences the nutritional profile by adjusting the fractions of proteins and carbohydrates, thereby potentially enhancing their digestibility and value as forage for animals (Dias et al., 2025).

4.3 Effect of intercropping on organic acid distribution in M. sativa and H. marinum under different nutrient supplement

The shifts in carbohydrate metabolism were matched by parallel changes in organic acid accumulation. Under intercropping, both species accumulated higher levels of citrate and isocitrate in leaves compared to monocultures, based on a study by Finkemeier et al. (2013) when a plant is under stress, citrate, an intermediate of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, starts to build up because parts of this metabolic pathway are slowing down. That excess of citrate then acts as a specific signal that triggers changes in gene expression related to photosynthesis, defense, and nutrient management, helping the plant adapt to stress conditions. Moreover, root profiles showed that intercropped plants, particularly H. marinum, built up malate, succinate, malonate, and citrate under N limitation. For example, the rise in succinic acid levels in Hordeum marinum leaves and roots suggests that the plant may be converting GABA into succinic acid to fuel its metabolism via TCA cycle. This process likely helps the plant stay active and resilient when facing stresses like cold, heat, drought, or salinity (Hijaz and Killiny, 2019; Wu et al., 2025).

4.4 Effect of intercropping on amino-acid distribution in M. sativa and H. marinum under different nutrient supplements

Free amino acid profiling completed the picture of stress adaptation by revealing distinct strategies. Under nutrient limitation, H. marinum leaves accumulated very high levels of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and asparagine (Asn), despite low proline, indicating that the halophyte channels nitrogen into these pools rather than into proline under N stress. Barakat (2010) demonstrated that under stress conditions, plants quickly accumulate GABA, which plays a protective role by limiting oxidative damage, modulating hormonal signaling, and maintaining energy production via the GABA shunt, particularly when TCA cycle activity is compromised. Stress-induced accumulation of asparagine may result from underlying mineral deficiencies (Lea et al., 2007), Asparagine accumulation under stress seems to be an adaptive strategy for plants, especially during times of disease or nutrient deficiencies. It likely helps store and transport nitrogen and also aids in detoxifying excess ammonia. When stress causes an increase in proteolysis and ammonia levels, plants convert this surplus ammonia into asparagine using the GS/GOGAT pathway and asparagine synthetase (Oddy et al., 2020).

In contrast, M. sativa leaves under low nutrients showed elevated proline. Proline plays a vital role in helping plants cope with stress by acting as an osmoprotectant. It helps stabilize cell structures and enzymes, neutralize harmful reactive oxygen species (ROS), and maintain the redox balance. Its accumulation is often associated with improved levels of certain mineral nutrients (Cacefo et al., 2021). The decline in glutamate may reflect its use as a precursor for other protective compounds, highlighting a reorientation of nitrogen metabolism (Forde and Lea, 2007). Overall, intercrops displayed improved N status: the H. marinum partner’s surge in GABA and Asn indicates enhanced N assimilation, while alfalfa’s maintenance of glutamate and other amino acids supports sustained symbiotic N fixation. These complementary metabolic shifts mirror observations in other legume–cereal intercrops, where legumes upregulate amino-acid metabolism when grown in mixtures. Studies by Gu et al. (2025) and Liu et al. (2024) show that intercropping, whether Camellia oleifera with peanuts or tobacco with maize or soybean, stimulates amino acid metabolism and transport in plant roots. This includes an increase in key compounds like L-tryptophan and proline, which play vital roles in nutrient assimilation, stress tolerance, and plant growth. Additionally, the modulation of root exudates helps attract beneficial soil microbes, further supporting plant health and resulting in improved photosynthesis and higher yields.

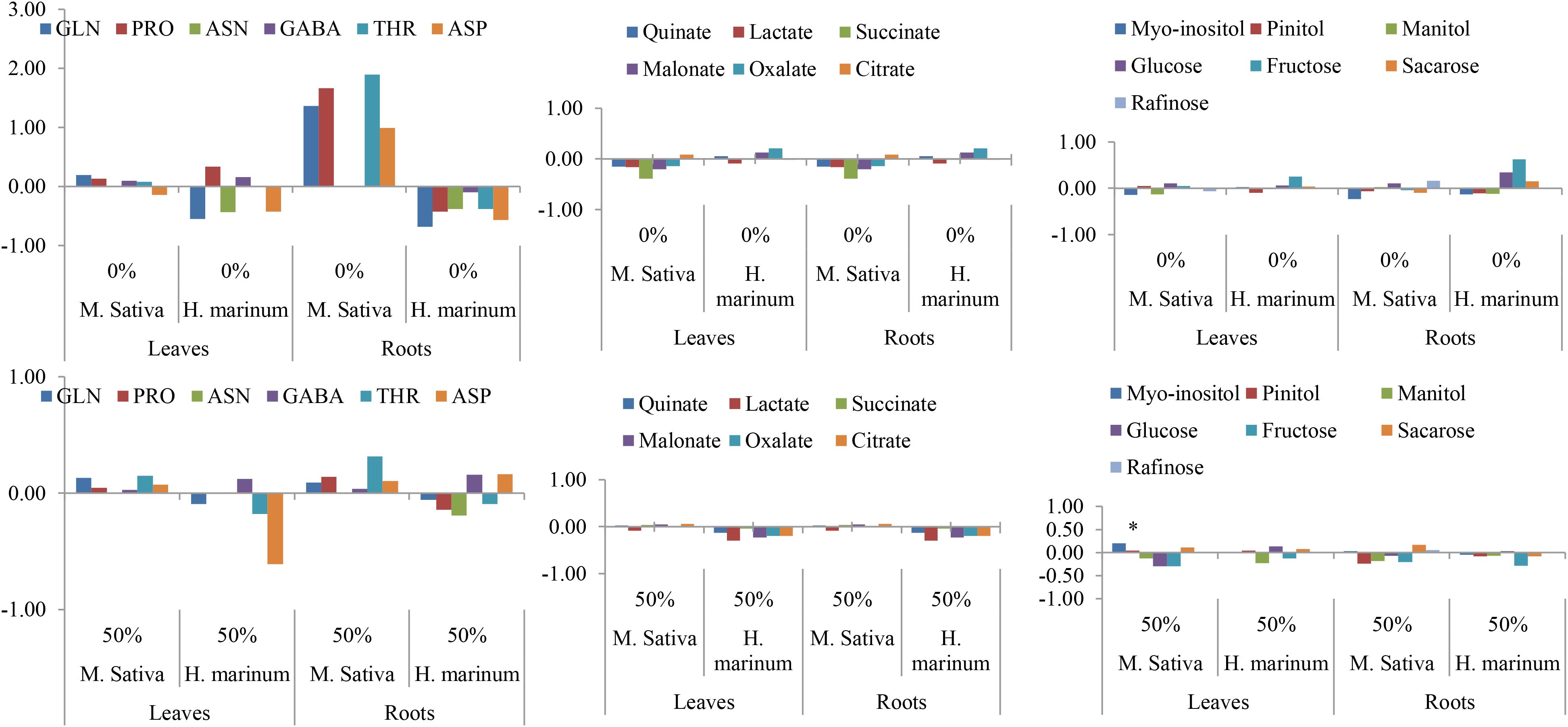

Figure 6 presents the distribution of carbon metabolites. Metabolite profiling revealed distinct species- and tissue-dependent responses to intercropping, as indicated by the log2(intercrop/monocrop) ratios. In Medicago sativa, root concentrations of proline, threonine, and aspartate markedly increased under the 0% nutrient level, whereas in Hordeum marinum, leaf aspartate significantly declined under the 50% treatment. Organic acids, particularly succinate, consistently decreased in both organs of M. sativa, with a similar but less pronounced trend in H. marinum. Conversely, glucose and fructose accumulated in the roots of H. marinum under control conditions, reflecting an adjustment in carbon metabolism.

Figure 6. Log2 (Intercrop/Monocrop) ratios of metabolites (Carbohydrates, amino-acids, and organic acids) in Medicago sativa and Hordeum marinum under two nutrient levels (0% and 50%).

Taken together, these results illustrate how intercropping enhances metabolic flexibility and nutrient economy, enabling both species to better withstand nutrient limitations. The complementary resource use, combined with improved biochemical resilience, underlines the ecological advantage of intercropping systems in low-input conditions. Such findings support the strategic use of intercropping for sustainable forage production in semi-arid environments, offering a pathway to mitigate the effects of nutrient stress while maintaining crop productivity and quality.

5 Conclusions

This study highlights the significant impact of intercropping on biomass production and nutrient uptake under limited nutrient conditions. Overall, the intercropping system between M. sativa and H. marinum enhanced aerial biomass, improved nutrient acquisition, and stimulated key carbon and nitrogen metabolite accumulation under nutrient-limited conditions. These physiological and biochemical improvements underline the potential of this system to optimize plant performance in challenging semi-arid environments. Beyond the biological benefits, such enhancements could translate into reduced fertilizer needs, improved resource-use efficiency, and greater system resilience, making this intercropping strategy not only agronomically promising but also economically feasible for sustainable forage production in resource-limited contexts. To make this work on real farms, we’ll need to run field trials to determine optimal sowing densities and harvest schedules. Performing detailed economic cost–benefit analyses will quantify potential fertilizer savings and profitability gains. Investigating soil–plant–microbe interactions will elucidate the biological mechanisms driving these benefits. Finally, modeling long-term impacts on soil health, water-use efficiency, and regional forage availability will enable the development of scalable, climate-smart intercropping guidelines for semi-arid agricultural systems.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

AG: Validation, Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Software, Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft. WM: Validation, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Software, Supervision. GG: Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Software, Writing – review & editing. AM: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Resources. NL: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Validation. EG: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology. MB: Writing – review & editing, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Visualization, Validation, Resources, Data curation, Project administration, Formal Analysis.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Tunisian Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research (LR15 CBBC02) and the Tunisian-South African project (2019–2024).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fagro.2025.1636363/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Table 1 | ANOVA summary of fresh and dry biomass accumulation in Medicago sativa and Hordeum marinum across cultivation systems (CS) (monocropping vs intercropping), fertilization rates (FR) (0%, 50%), and harvest timing (H) (May, Juin and July) Variation between sample means related to variation within samples (F) and the corresponding p-value (P) is presented for each comparison. Statistically significant values (P ≤ 0.05) are shown in bold. Aerial fresh weight (AFW), aerial dry weight (ADW).

Supplementary Table 2 | Two-ways ANOVA summary of nutrient content in Medicago sativa and Hordeum marinum across cultivation system (CS) (monocropping vs. intercropping) and fertilization rate (FR) (0%, 50%). Variation between sample means related to variation within samples (F) and the corresponding p-value (P) is presented for each comparison. Statistically significant values (P ≤ 0.05) are shown in bold.

Supplementary Table 4 | Two-ways ANOVA summary of carbohydrate content of leaves and roots in Medicago sativa and Hordeum marinum across fertilization rate (FR) (0%, 50%) and cultivation system (CS) (monocropping vs. intercropping) and their interaction. Variation between sample means related to variation within samples (F) and the corresponding p-value (P) is presented for each comparison. Statistically significant values (P ≤ 0.05) are shown in bold.

Supplementary Table 5 | Two-ways ANOVA summary of organic acid content of leaves and roots in Medicago sativa and Hordeum marinum across fertilization rate (FR) (0%, 50%) and cultivation system (CS) (monocropping vs. intercropping) and their interaction. Variation between sample means related to variation within samples (F) and the corresponding p-value (P) is presented for each comparison. Statistically significant values (P ≤ 0.05) are shown in bold. Nitrite, Isocitrate, pyruvate and α-Ketoglutarate were below detection limit in all the samples.

References

Abbasi M. R. and Sepaskhah A. R. (2022). Evaluation of saffron yield affected by intercropping with winter wheat, soil fertilizers, and irrigation regimes in a semi-arid region. Int. J. Plant Prod. 16, 511–529. doi: 10.1007/s42106-022-00194-4

AbdelRahman M. A. E. (2023). An overview of land degradation, desertification and sustainable land management using GIS and remote sensing applications. Rend. Lincei Sci. Fis. Nat. 34, 767–808. doi: 10.1007/s12210-023-01155-3

Abid M., Mansour E., Khaled A. B., Bachar K. D., Yahya L. B., and Ferchichi A. (2016). Induced osmotic adjustment in alfalfa plants confers tolerance to water stress. J. Plant Physiol. 200, 1–10.

Afzal S., Chaudhary N., and Singh N. K. (2021). “Role of soluble sugars in metabolism and sensing under abiotic stress,” in Plant Growth Regulators: Signalling under Stress Conditions. Eds. Aftab T. and Hakeem K. R. (Springer, Cham), 305–334. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-61153-8_14

Ahmed N., Zhang B., Bozdar B., Chachar S., Rai M., Li J., et al. (2023). The power of magnesium: unlocking the potential for increased yield, quality, and stress tolerance of horticultural crops. Front. Plant Sci. 14. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1285512

Amanullah K. S., Khalil F., and Imranuddin (2020). Influence of irrigation regimes on competition indexes of winter and summer intercropping system under semi-arid regions of Pakistan. Sci. Rep. 10, 8129. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-65195-7

Amoah A. A., Miyagawa S., and Kawakubo N. (2012). Effect of supplementing inorganic fertilizer with organic fertilizer on growth and yield of rice–cowpea mixed crop. Plant Prod. Sci. 15, 109–117. doi: 10.1626/pps.15.109

Arlt K., Brandt S., and Kehr J. (2001). Amino acid analysis in five pooled single plant cell samples using capillary electrophoresis coupled to laser-induced fluorescence detection. J. Chromatogr. A 926, 319–325. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9673(01)01052-4

Ashoori N., Abdi M., Golzardi F., Ajalli J., and Ilkaee M. N. (2021). Forage potential of sorghum–clover intercropping systems in semi-arid conditions. Bragantia 80, e1421. doi: 10.1590/1678-4499.20200423

Barakat N. (2010). The role of amino acids in improvement in salt tolerance of crop plants. J. Stress Physiol. Biochem. 6 (3), 25–37.

Betencourt E., Duputel M., Colomb B., Desclaux D., and Hinsinger P. (2012). Intercropping promotes the ability of durum wheat and chickpea to increase rhizosphere phosphorus availability in a low P soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 46, 181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.11.015

Cacefo V., Ribas A. F., Guidorizi K. A., and Vieira L. G. E. (2021). Exogenous proline alters the leaf ionomic profiles of transgenic and wild-type tobacco plants under water deficit. Ind. Crops Prod. 170, 113734. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.113734

Calleja-Satrustegui A., Echeverría A., Ariz I., Peralta de Andrés J., and González E. M. (2025). Unlocking nature’s drought resilience: a focus on the parsimonious root phenotype and specialised root metabolism in wild Medicago populations. Plant Soil 510, 565–581. doi: 10.1007/s11104-024-06943-w

Castañeda V., de la Peña M., Azcárate L., Aranjuelo I., and Gonzalez E. M. (2019). Functional analysis of the taproot and fibrous roots of Medicago truncatula: sucrose and proline catabolism primary response to water deficit. Agric. Water Manage. 216, 473–483. doi: 10.1016/j.agwat.2018.07.018

Chapagain T. and Riseman A. (2014). Barley–pea intercropping: Effects on land productivity, carbon and nitrogen transformations. Field Crops Res. 166, 18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2014.06.014

Chen Z., Wang W., Chen L., Zhang P., Liu Z., Yang X., et al. (2024). Effects of pepper–maize intercropping on the physicochemical properties, microbial communities, and metabolites of rhizosphere and bulk soils. Environ. Microb. 19, 108. doi: 10.1186/s40793-024-00653-7

Deng P., Yin R., Wang H., Chen L., Cao X., and Xu X. (2023). Comparative analyses of functional traits based on metabolome and economic traits variation of Bletilla striata: contribution of intercropping. Front. Plant Sci. 14. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1147076

Dias M. B. D. C., Costa K. A. P., Bilego U. O., Costa J. V. C. P., and Bezerra Fernandes P. (2025). Protein and carbohydrate fractionation of Urochloa spp. and Megathyrsus maximus forages after intercropping with soybean in an integrated crop-livestock system. N. Z. J. Agric. Res. 68 (1), 116. doi: 10.5555/20250062576

Dong N., Tang M.-M., Zhang W.-P., Bao X.-G., Wang Y., Christie P., et al. (2018). Temporal differentiation of crop growth as one of the drivers of intercropping yield advantage. Sci. Rep. 8, 3110. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21414-w

Dowling A., Roberts P., Doolette A., Zhou Y., and Denton M. D. (2023). Oilseed-legume intercropping is productive and profitable in low input scenarios. Agric. Syst. 204, 103551. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2022.103551

Duan Y., Shang X., Liu G., Zou Z., Zhu X., Ma Y., et al. (2021). The effects of tea plant–soybean intercropping on the secondary metabolites of tea plants by metabolomics analysis. BMC Plant Biol. 21, 482. doi: 10.1186/s12870-021-03258-1

Duan Y., Shen J., Zhang X., Wen B., Ma Y., Wang Y., et al. (2019). Effects of soybean–tea intercropping on soil-available nutrients and tea quality. Acta Physiol. Plant 41, 140. doi: 10.1007/s11738-019-2932-8

Finkemeier I., König A.-C., Heard W., Nunes-Nesi A., Pham P. A., Leister D., et al. (2013). Transcriptomic analysis of the role of carboxylic acids in metabolite signaling in Arabidopsis leaves. Plant Physiol. 162, 239–253. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.214114

Forde B. G. and Lea P. J. (2007). Glutamate in plants: metabolism, regulation, and signalling. J. Exp. Bot. 58, 2339–2358. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm121

Gálvez L., González E. M., and Arrese-Igor C. (2005). Evidence for carbon flux shortage and strong carbon/nitrogen interactions in pea nodules at early stages of water stress. J. Exp. Bot. 56, 2551–2561. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri249

Gu Y., Jiao J., Xu H., Chen Y., He X., Wu X., et al. (2025). Intercropping improves the yield by increasing nutrient metabolism capacity and crucial microbial abundance in root of Camellia oleifera in purple soil. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 219, 109318. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2024.109318

Gebrehiwot K. (2022). Soil management for food security. In: Jhariya M.K., Meena R.S., Meena S.N., eds. Natural Resources Conservation and Advances for Sustainability. Chhattisgarh: Elsevier B.V. pp. 61–71. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-822976-7.00029-6

Guerchi A., Mnafgui W., Jabri C., Merghni M., Sifaoui K., Mahjoub A., et al. (2024). Improving productivity and soil fertility in Medicago sativa and Hordeum marinum through intercropping under saline conditions. BMC Plant Biol. 24, 158. doi: 10.1186/s12870-024-04820-3

Guerchi A., Mnafgui W., Mengoni A., and Badri M. (2023). Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.)/Crops intercropping provides a feasible way to improve productivity under environmental constraints. J. Oasis Agric. Sustain. Dev. 5, 38–47. doi: 10.56027/JOASD.112023

Hacham Y., Avraham T., and Amir R. (2002). The N-terminal region of Arabidopsis cystathionine γ-synthase plays an important regulatory role in methionine metabolism. Plant Physiol. 128, 454–462. doi: 10.1104/pp.010819

Hijaz F. and Killiny N. (2019). Exogenous GABA is quickly metabolized to succinic acid and fed into the plant TCA cycle. Plant Signal. Behav. 14, e1573096. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2019.1573096

Jabri C., Zaidi N., Maiza N., Rafik K., Ludidi N., and Badri M. (2021). Effects of salt stress on the germination of two contrasting Medicago sativa varieties. J. Oasis Agric. Sustain. Dev. 3, 13–18. doi: 10.56027/JOASD.spiss022021

Jensen E. S., Carlsson G., and Hauggaard-Nielsen H. (2020). Intercropping of grain legumes and cereals improves the use of soil N resources and reduces the requirement for synthetic fertilizer N: a global-scale analysis. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 40, 5. doi: 10.1007/s13593-020-0607-x

Kherif O., Seghouani M., Zemmouri B., Bouhenache A., Keskes M. I., Yacer-Nazih R., et al. (2021). Understanding the response of wheat–chickpea intercropping to nitrogen fertilization using agro-ecological competitive indices under contrasting pedoclimatic conditions. Agronomy 11, 1225. doi: 10.3390/agronomy11061225

Kirkby M. (2021). Desertification and development: some broader contexts. J. Arid Environ. 193, 104575. doi: 10.1016/j.jaridenv.2021.104575

Koskey G., Leoni F., Carlesi S., Avio L., and Bàrberi P. (2022). Exploiting plant functional diversity in durum wheat–lentil relay intercropping to stabilize crop yields under contrasting climatic conditions. Agronomy 12, 210. doi: 10.3390/agronomy12010210

Kumar N., Srivastava P., Vishwakarma K., Kumar R., Kuppala H., Maheshwari S. K., et al. (2020). “The Rhizobium–plant symbiosis: state of the art,” in Plant Microbe Symbiosis. Eds. Varma A., Tripathi S., and Prasad R. (Springer, Cham), 1–20. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-36248-5_1

Latati M., Blavet D., Alkama N., Laoufi H., Drevon J. J., Gérard F., et al. (2014). The intercropping cowpea–maize improves soil phosphorus availability and maize yields in an alkaline soil. Plant Soil 385, 181–191. doi: 10.1007/s11104-014-2214-6

Lea P. J., Sodek L., Parry M. A. J., Shewry P. R., and Halford N. G. (2007). Asparagine in plants. Ann. Appl. Biol. 150, 1–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.2006.00104.x

Li X., Xu Y., Mao Y., Wang S., Sun L., Shen J., et al. (2024). The effects of soybean–tea intercropping on the photosynthesis activity of tea seedlings based on canopy spectral, transcriptome and metabolome analyses. Agronomy 14, 850. doi: 10.3390/agronomy14040850

Liu M., Xue R., Jin S., Gu K., Zhao J., Guan S., et al. (2024). Metabolomic and metagenomic analyses elucidate the role of intercropping in mitigating continuous cropping challenges in tobacco. Front. Plant Sci. 15. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2024.1447225

Ma Y., Fu S., Zhang X., Zhao K., and Chen H. Y. H. (2017). Intercropping improves soil nutrient availability, soil enzyme activity and tea quantity and quality. Appl. Soil Ecol. 119, 171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2017.06.028

Ma Q., Song L., Niu Z., Qiu Z., Sun H., Ren Z., et al. (2022). Pea–tea intercropping improves tea quality through regulating amino acid metabolism and flavonoid biosynthesis. Foods 11, 3746. doi: 10.3390/foods11223746

Nasar J., Shao Z., Gao Q., Zhou X., Fahad S., Liu S., et al. (2022). Maize–alfalfa intercropping induced changes in plant and soil nutrient status under nitrogen application. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 68, 151–165. doi: 10.1080/03650340.2020.1827234

Nasar J., Zeqiang S., Gao Q., Zhou X., Fahad S., Liu S., et al. (2020). Maize–alfalfa intercropping induced changes in plant and soil nutrient status under nitrogen application. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 68.

Oddy J., Raffan S., Wilkinson M. D., Elmore J. S., and Halford N. G. (2020). Stress, nutrients and genotype: understanding and managing asparagine accumulation in wheat grain. CABI Agric. Biosci. 1, 10. doi: 10.1186/s43170-020-00010-x

Oueslati S., Serairi Beji R., Zar Kalai F., Soufiani M., Zorrig W., Aissam A., et al. (2024). Antioxidant potentialities and gastroprotective effect of Reichardia picroides extracts on ethanol/HCl induced gastric ulcer rats. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 34, 1088–1099. doi: 10.1080/09603123.2023.2198760

Pankou C., Lithourgidis A., Menexes G., and Dordas C. (2022). Importance of selection of cultivars in wheat–pea intercropping systems for high productivity. Agronomy 12, 2367. doi: 10.3390/agronomy12102367

Raza M. A., Yasin H. S., Gul H., Qin R., Mohi Ud Din A., Khalid M. H. B., et al. (2022). Maize/soybean strip intercropping produces higher crop yields and saves water under semi-arid conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1006720

Rodriguez C., Carlsson G., Englund J.-E., Flöhr A., Pelzer E., Jeuffroy M.-H., et al. (2020). Grain legume–cereal intercropping enhances the use of soil-derived and biologically fixed nitrogen in temperate agroecosystems: a meta-analysis. Eur. J. Agron. 118, 126077. doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2020.126077

Salinas-Roco S., Morales-González A., Espinoza S., Pérez-Díaz R., Carrasco B., del Pozo A., et al. (2024). N2 fixation, N transfer, and land equivalent ratio (LER) in grain legume–wheat intercropping: impact of N supply and plant density. Plants 13, 991. doi: 10.3390/plants13070991

Saoudi W., Badri M., Gandour M., Smaoui A., Abdelly C., and Taamalli W. (2017). Assessment of genetic variability among Tunisian populations of Hordeum marinum using morpho-agronomic traits. Crop Sci. 57, 302–309. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2016.03.0205

Saoudi W., Badri M., Taamalli W., Zribi O. T., Gandour M., and Abdelly C. (2019). Variability in response to salinity stress in natural Tunisian populations of Hordeum marinum subsp. marinum. Plant Biol. 21, 89–100. doi: 10.1111/plb.12890

Stomph T., Dordas C., Baranger A., de Rijk J., Dong B., Evers J., et al. (2020). “Designing intercrops for high yield, yield stability and efficient use of resources: Are there principles?,” in Advances in Agronomy. Ed. Sparks D. L. (Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier/Academic Press), 1–50. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2113(19)30107-5

Sun J., Gibson K. M., Kiirats O., Okita T. W., and Edwards G. E. (2002). Interactions of nitrate and CO2 enrichment on growth, carbohydrates, and Rubisco in Arabidopsis starch mutants: significance of starch and hexose. Plant Physiol. 130, 1573–1583. doi: 10.1104/pp.010058

Takizawa K. and Nakamura H. (1998). Separation and determination of fluorescein Isothiocyanate-Labeled amino acids by capillary electrophoresis with laser-induced fluorescence detection. Anal. Sci. 14, 925–992. doi: 10.2116/analsci.14.925

Tang X., He Y., Zhang Z., Wu H., He L., Jiang J., et al. (2022). Beneficial shift of rhizosphere soil nutrients and metabolites under a sugarcane/peanut intercropping system. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1018727

Tang X., Liao L., Wu H., Xiong J., Li Z., Huang Z., et al. (2024). Effects of sugarcane/peanut intercropping on root exudates and rhizosphere soil nutrient. Plants 13, 3257. doi: 10.3390/plants13223257

Tang X., Zhang C., Yu Y., Shen J., van der Werf W., and Zhang F. (2021). Intercropping legumes and cereals increases phosphorus use efficiency: a meta-analysis. Plant Soil 460, 89–104. doi: 10.1007/s11104-020-04768-x

Trading Economics (2024). Tunisia average precipitation. Available online at: https://tradingeconomics.com/Tunisia/precipitation (Accessed May 9, 2025).

Wang X., Feng Y., Yu L., Shu Y., Tan F., Gou Y., et al. (2020). Sugarcane/soybean intercropping with reduced nitrogen input improves crop productivity and reduces carbon footprint in China. Sci. Total Environ. 719, 137517. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137517

Wang Z.-G., Jin X., Bao X.-G., Li X.-F., Zhao J.-H., Sun J.-H., et al. (2014). Intercropping enhances productivity and maintains the most soil fertility properties relative to sole cropping. PloS One 9, e113984. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113984

Wu J., Sun M., Pang A., Ma K., Hu X., Feng S., et al. (2025). Succinic acid synthesis regulated by succinyl-coenzyme A ligase (SUCLA) plays an important role in root response to alkaline salt stress in Leymus chinensis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 220, 109485. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2025.109485

Xie J., Wang L., Li L., Anwar S., Luo Z., Zechariah E., et al. (2021). Yield, economic benefit, soil water balance, and water use efficiency of intercropped maize/potato in responses to mulching practices on the semiarid Loess Plateau. Agriculture 11, 1100. doi: 10.3390/agriculture11111100

Xing Y., Yu R.-P., An R., Yang N., Wu J.-P., Ma H.-Y., et al. (2023). Two pathways drive enhanced nitrogen acquisition via a complementarity effect in long-term intercropping. Field Crops Res. 293, 108854. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2023.108854

Yin W., Chai Q., Zhao C., Yu A., Fan Z., Hu F., et al. (2020). Water utilization in intercropping: a review. Agric. Water Manage. 241, 106335. doi: 10.1016/j.agwat.2020.106335

Zhao X., Dong Q., Han Y., Zhang K., Shi X., Yang X., et al. (2022). Maize/peanut intercropping improves nutrient uptake of side-row maize and system microbial community diversity. BMC Microbiol. 22, 14. doi: 10.1186/s12866-021-02425-6

Keywords: intercropping, Medicago sativa- Hordeum marinum, drought stress, nutrient deficiency, metabolomics, nutrient uptake, biomass productivity

Citation: Guerchi A, Mnafgui W, Garijo G, Mahjoub A, Ludidi N, Gonzalez EM and Badri M (2025) Impact of intercropping on agronomic and metabolic responses of Medicago sativa and Hordeum marinum under nutrient deficiency and drought stress. Front. Agron. 7:1636363. doi: 10.3389/fagro.2025.1636363

Received: 02 June 2025; Accepted: 12 November 2025; Revised: 30 October 2025;

Published: 04 December 2025.

Edited by:

Aqeel Ahmad, University of Florida, United StatesReviewed by:

Srija Priyadarsini, Odisha University of Agriculture and Technology, IndiaJahangir Khan, The University of Queensland, Australia

Copyright © 2025 Guerchi, Mnafgui, Garijo, Mahjoub, Ludidi, Gonzalez and Badri. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mounawer Badri, bW91bmF3ZXIuYmFkcmlAY2JiYy5ybnJ0LnRu

Amal Guerchi1,2

Amal Guerchi1,2 Wiem Mnafgui

Wiem Mnafgui Gustavo Garijo

Gustavo Garijo Ndiko Ludidi

Ndiko Ludidi Esther M. Gonzalez

Esther M. Gonzalez Mounawer Badri

Mounawer Badri