- 1School of Tourism, Xinyang Normal University, Xinyang, Henan, China

- 2Henan International Joint Laboratory of Tea-Oil Tree Biology and High Value Utilization, School of Life Sciences, Xinyang Normal University, Xinyang, Henan, China

Rapid urbanization has led to a large-scale loss of cropland to non-agricultural uses. To avoid losses caused by abandonment, farmers working in cities have converted part of their farmland into economic forests (Primarily poplar). To assess how converting cropland to forest land negatively impacts neighboring grain production, we selected five agroforestry interfaces in humid and semi-humid regions of China. We investigated the effects of long-term poplar planting on the production process of summer maize in neighboring fields. Eight sampling points (d1-d8) were established at 1-meter intervals along the agroforestry interface extending into the maize field, at each interface. During the maize maturity stage, morphological structure, yield, and dry matter distribution were measured. The results showed that long-term planting of poplar trees had a significant effect on the growth and harvest parameters of neighboring summer maize. Compared to the farthest distance (control), the maize plants closest to the poplar trees exhibited reductions in plant height, stem diameter, and leaf area by 46.4%, 34.9%, and 60.2%, respectively. Compared to control, root, stem, leaf, tassel, bract, and corncob dry weight at d1 were reduced by 47.2%, 28.7%, 42.6%, 27.5%, 35.3%, and 40.5%, respectively, and the yield per spike and total dry weight at d1 were reduced by 94.9% and 58.0%, respectively. Furthermore, trend analysis revealed that these parameters exhibited logarithmic growth trends with increasing distance (All R2 > 0.80). Structural equation modeling demonstrated that summer maize morphological structure and dry matter distribution directly and indirectly influenced yield per spike and total dry weight through distinct pathways. These findings provide management implications for mitigating the negative impacts of agroforestry systems on agricultural production in humid regions, while also providing a parameter basis for accurately assessing the grain yield reduction effect resulting from the large-scale conversion of agricultural land to forestry.

1 Introduction

Food security is crucial to the survival and development of humankind worldwide (Xu et al., 2022). In particular, in recent years, with the intensification of human activities and climate change, the issue of food production and security has received increasing attention from scholars (Sahu and Liu, 2023). On the one hand, a country or region’s political, economic, and cultural factors may indirectly affect food security (Liu and Zhou, 2021). On the other hand, changes in land use types, the use of bioenergy crops, and global climate change can directly influence food production and security (Cui and Zhong, 2024; Sabir et al., 2024; Xu et al., 2022). Therefore, ensuring food security amid global changes and increasing human activities will be one of the key challenges facing humanity in the future.

Maintaining both the quantity and quality of cropland is one of the key factors in ensuring food security (Sabir et al., 2024). However, irrational cropland utilization may directly or indirectly affect food production and security (Molotoks et al., 2021; Wang, 2022). On the one hand, accelerated urbanization has led to the conversion of significant amounts of cropland to urban use (Liu and Zhou, 2021). Research indicates that over 55,000 square kilometers of cropland in China were converted to urban use between 2010 and 2020 (Zeng et al., 2023). On the other hand, the rapid rural-to-urban population migration may trigger the conversion of agricultural land to other land-use types such as wasteland, woodland, and grassland. This transition could subsequently lead to increased farmland fragmentation and diminished food production capacity (Chen et al., 2024; Sethumadhavan et al., 2024). Between 2010 and 2020, high-risk areas for cropland abandonment in China showed an increasing trend (Zeng et al., 2024), and 83.8% of counties demonstrated an upward trend in the cropland fragmentation index (Qu et al., 2025). The decrease in rural population has created challenges for agricultural production on small-scale farms, leading to cropland abandonment or conversion to forest land (Li and Li, 2016). This replacement of cropland with forest land not only reduces grain yield per unit area but also affects food production in adjacent cropland (Ramesh et al., 2023). According to a study by Yang et al. (2023), agroforestry systems led to average crop yield reductions of 33.9%, 47.8%, 20.6%, and 43.4% in Northwest, East, North, and South China, respectively.

Research on the impact of forestland on the yield of neighboring crops has mainly focused on agroforestry systems (Pohlmann et al., 2024; Saj et al., 2023). An agroforestry system generally refers to an integrated system of agriculture and forestry (Hildreth, 2008; Khan et al., 2022). These systems are based on theories of ecological niche complementarity and species symbiosis to avoid excessive competition and thus achieve a win-win situation (Fernández et al., 2007; Loreau and Hector, 2001). They play an important and positive role in increasing carbon sequestration (Verma et al., 2023), improving soil health (Muchane et al., 2020), regulating soil microbial communities (Wang et al., 2022), improving water use efficiency (Bai et al., 2016), maintaining microclimate conditions (Karvatte et al., 2020), and reducing water and soil losses (Zhu et al., 2020). In arid and semi-arid areas, where water and nutrients are limited, agroforestry systems can create complementary effects and achieve win-win outcomes (Veldkamp et al., 2023; Verma et al., 2023). A study in the Mediterranean demonstrated that agroforestry systems can effectively buffer against adverse climatic conditions, stabilizing or even enhancing crop yields under climate change (Amassaghrou et al., 2023). In contrast, research conducted in Windlach, located in the northern part of Kanton Zürich, indicated that moderate shading had no effect on barley yield within temperate forest-based agroforestry systems (Vaccaro et al., 2022). Therefore, the impact of agroforestry systems on crop yield remains uncertain, particularly regarding its effects across different regions and tree species (Baier et al., 2023; Khan et al., 2022; Ramesh et al., 2023). Moreover, few studies have examined the impact of converting cropland to forestland on agricultural production, especially in humid and semi-humid areas.

In certain regions of China, cropland faces the risk of abandonment due to rural-to-urban migration. To prevent this, some croplands have been converted to economic forests (primarily poplar plantations). Based on the results of the 2018 Ninth National Forest Inventory, compared with 1973, the area of plantation forests saw a net increase of 6.7312 million hm2. Nearly half of this increase (47.97%) originated from afforestation on former cropland, with poplar forests ranking as the second largest category by area within these plantations. The main reason for choosing poplar is that it is known as ‘the people’s tree’ and is widely planted worldwide due to its broad environmental adaptability (Xi et al., 2021). Its natural distribution ranges from 22°N to 70°N, with an altitudinal range reaching 4800m (Xi et al., 2021). Poplar trees exhibit fast growth, easy propagation, and high hybridization potential, making them valuable for environmental improvement and economic benefits in many countries (Richardson and Isebrands, 2014). To optimize poplar cultivation efficiency, mixed cropping systems combining poplar and crops have been developed successfully in many arid and semi-arid regions (Dai et al., 2021). However, significant poplar planting also occurs on cropland in humid and semi-humid areas (Xi et al., 2021). The extent of poplar’s impact on adjacent food production remains unclear in these humid and semi-humid regions.

In summary, while agroforestry systems have been extensively studied in arid and semi-arid regions, research remains relatively limited in humid and semi-humid areas. Moreover, due to the distinct climatic conditions and agricultural practices (such as cropland-to-woodland conversion) in these regions, the response patterns of agroforestry ecosystems may differ significantly. Therefore, this study investigates the effects of long-term poplar planting on the morphology and yield of neighboring summer maize to address the following questions: (1) In humid and semi-humid regions, does poplar cultivation influence the morphology and yield of neighboring maize, and what is the effective impact distance? (2) What underlying factors drive the observed changes in maize yield? (3) How can the response patterns of neighboring maize to long-term poplar planting provide guidance for future agroforestry system management and supply critical parameters for large-scale agricultural yield assessments?

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Experimental site

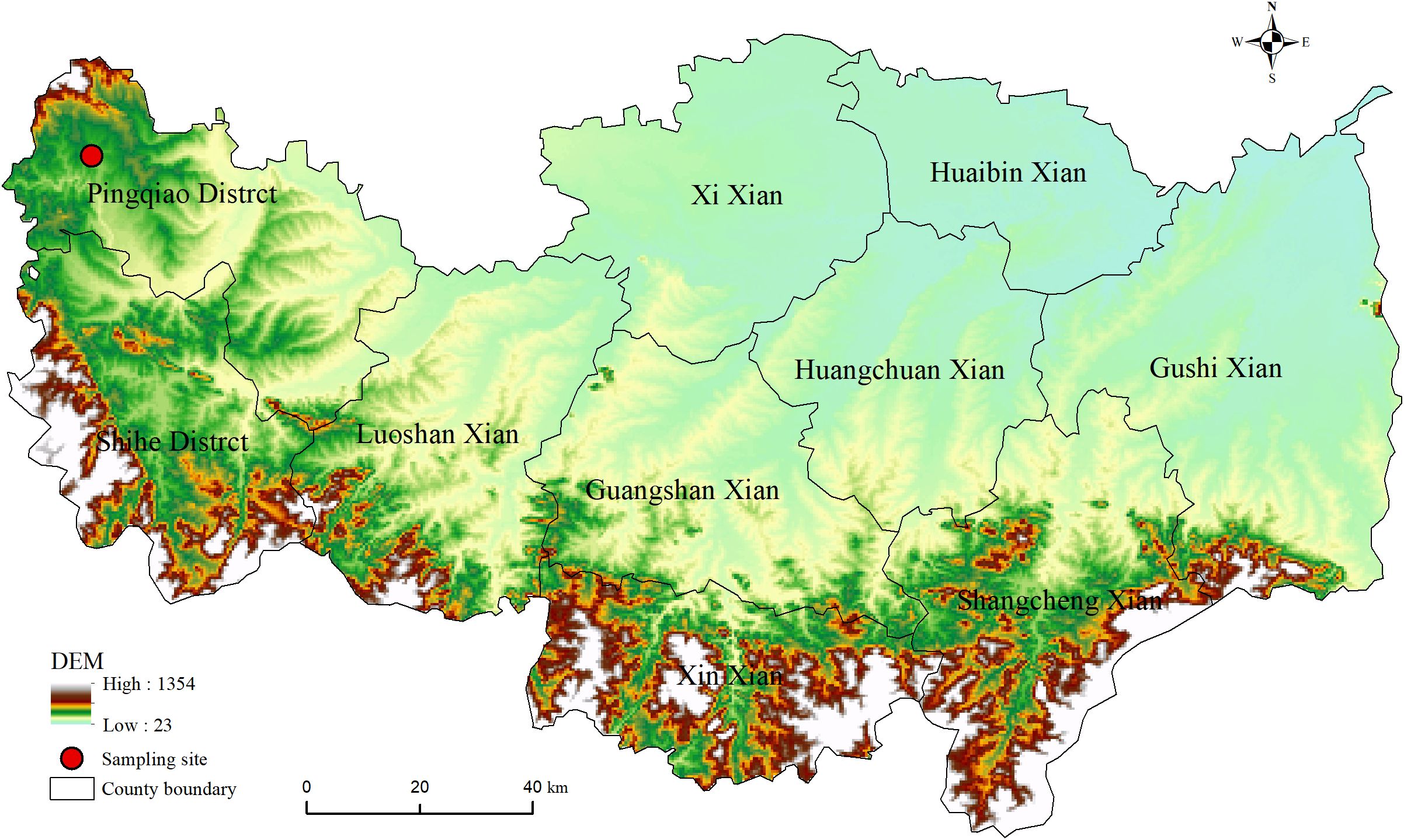

The study area is located in Pingqiao District (113°42’~114°25’E, 31°43’~32°37’N), Xinyang City, Henan Province, China, with an elevation range of 60 to 214m above sea level (Figure 1). This region lies in the transition zone between subtropical and northern temperate zones. The climate is a moist continental temperate type, characterized by cold, dry winters and rainy, hot summers. The long-term mean annual precipitation is approximately 1100mm, with marked seasonal and inter-annual variation. Most precipitation occurs between June and July, accounting for 66% of the annual total. The mean annual temperature is 15.2°C, with monthly averages ranging from 1.9°C in January to 33.6°C in July (China Meteorological Data Sharing Service System, https://data.cma.cn/). Five agroforestry transition zones were selected for investigation in the area. All five transition zones were located within a 1-km radius, covering areas ranging from 2,500 to 10,000 m², with interface lengths of 50–100 m.

The study area is characterized by loamy soils derived from alluvial deposits, typical of humid and semi-humid regions in central China, with moderate fertility and a history of maize–wheat rotation prior to the establishment of poplar plantations. These soils generally exhibit a pH of 6.5–7.5 and organic matter content around 15–20 g kg-1, according to local soil survey data.

2.2 Experimental design

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the long-term poplar planting effects on the morphology and yield of adjacent summer maize. Prior to the establishment of poplar plantations, these sites were typical agricultural areas with a long history of cultivation. Located within humid and semi-humid regions, the primary agricultural land use consisted of rain-fed farmland (without irrigation). The prevailing cropping pattern involved the rotation of crops such as maize, peanuts, soybeans, and wheat without a fixed sequence. The management practices were predominantly characterized by extensive farming. After planting, the poplar trees remained unmanaged and grew naturally over the long term. The crops were cultivated using traditional methods and extensive management, without consideration of any synergistic effects with the poplar stand. Due to recent urbanization, substantial rural-to-urban migration has led to partial cropland abandonment and conversion to non-grain land uses (e.g., economic forests), with poplar being the dominant species in such plantations within the region. The poplar trees were 15–17 years old, with an average height of 17m and mean diameter at breast height of 28.5cm. The planting interval between poplars was approximately 5m. The maize cultivation areas were all situated north of the poplar stands, where summer shading effects were significant. Maize was mechanically planted with 0.5m row spacing in an east-west orientation. The nearest distance between maize and poplar rows was 1m, with 0.3m spacing between individual maize plants. Planting occurred between April 15-30, 2023.

2.3 Plant sampling and analysis

Plant sampling and marking were conducted from September 1-5, 2023. Sampling areas were established in the central zone of each agroforestry interface with five replicates spaced approximately 5 meters apart. Sampling commenced from the row closest to the poplar trees at 1-meter intervals, extending to a maximum distance of 8 meters from the poplar trees, beyond which no significant differences in maize plants were observed (d1 to d8 represent sampling distances of 1 to 8 meters). Therefore, we defaulted to the farthest point (d8) as the control group. At each sampling point (d1 to d8), three maize plants with similar growth were marked. During the early harvest period (prior to leaf wilting; Sampling date: September 1, 2023), we measured plant height, basal stem diameter, and average leaf area of the marked plants. Leaf area was expressed as the average single leaf area. Using the measurement method by Ma and Zhou, 2013, the length and width of all leaves were first measured, and the single leaf area was calculated using the formula: leaf area = leaf length × leaf width × 0.75. The total leaf area was then obtained by summing the areas of all leaves, and the average single leaf area was calculated by dividing the total leaf area by the number of leaves per plant. Basal stem diameter was measured at a height of 3cm above the ground.

From September 10-25, 2023, the marked maize plants were harvested. The harvested maize samples were first cleaned at the root zone to remove surface soil and then transported to the laboratory. All samples were oven dried at 65°C for 48h and weighed (Zhong et al., 2022). Dry matter distribution of summer maize was determined for roots, stems, leaves, tassels, bracts, cobs, and grains. Total dry matter content was calculated by summing all components. Cobs were threshed and weighed to determine yield per plant.

2.4 Photosynthetically active radiation (PAR), soil moisture and temperature measurement

From September 1 to 20, 2023, PAR was measured between 11:00 and 12:00 hours on three consecutive sunny days using a Li-Cor Quantum Sensor (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE, USA; Zhong et al., 2022). Within each sampling point, three measurements were taken at the top of the maize canopy to obtain the average PAR at the canopy level (PARu). The ambient PAR (PARn) was simultaneously measured in an open area without shading from poplar trees. The intercepted PAR (PARi) was then calculated as: PARi = (PARn - PARu)/PARn. Since shade from the trees was completely absent beyond 5 meters, PARi was measured only up to that distance (d1-d5).

Soil temperature and moisture were measured at the identical time points as the PAR measurements. Soil moisture (at 10cm depth) and temperature (0–10 cm depth) were measured three times per sampling point, using a portable soil probe (Diviner-2000, Sentek Pty Ltd., Australia) and a thermocouple connected to a Li-8100 Soil CO2 Flux System (Li-Cor Inc., USA), respectively (Zhong et al., 2019). As no significant variations in soil temperature and moisture were observed, these parameters were omitted from the analysis in the Results section.

2.5 Statistical analyses

All data analyses were performed using R 4.4.0 software. In this study, the five agroforestry zones were treated as independent blocks (replicates), and the sampling distance from poplar trees (d1–d8) was considered a fixed factor. A one-way ANOVA with a randomized block design was performed to test the effects of distance on maize growth traits, with the “agroforestry zone” included as a random blocking factor to account for spatial heterogeneity among zones. Mean values of the three marked plants per sampling point were used for analysis. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to examine differences across sampling distances, with statistical significance set at P<0.05. Linear and nonlinear trend analyses in R were employed to analyze the variation of relevant parameters with distance, with the best-fitting equation (largest R²) selected for result presentation. Additionally, we performed heat map analysis for all measured indicators and developed a structural equation model to explore relationships among variables. The graphics were finalized and optimized in both Excel and R software.

3 Results

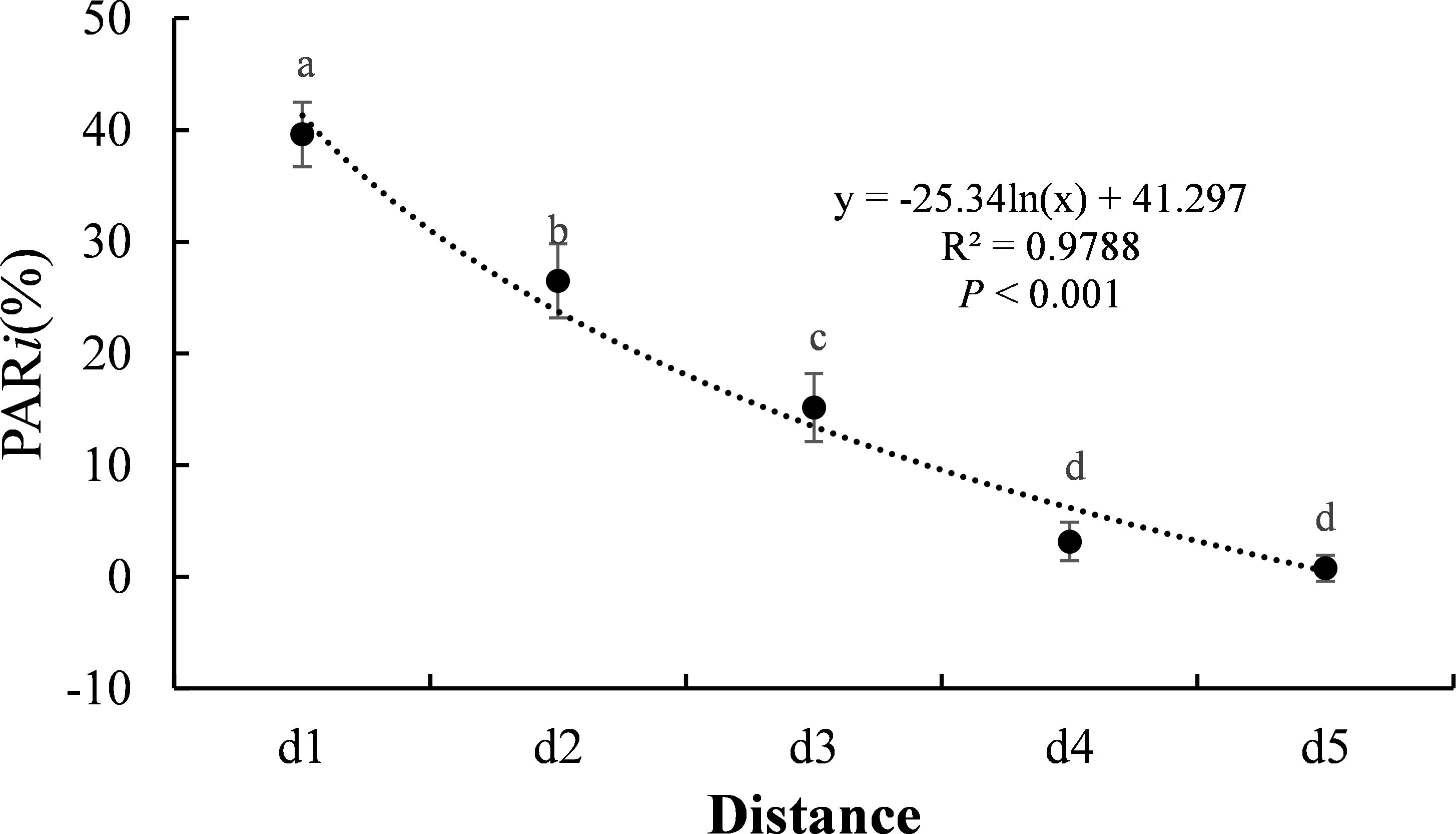

3.1 PARi change

PARi decreased significantly with increasing distance from the interface (P<0.001, Figure 2). The mean PARi at d1 to d5 were 39.6%, 26.5%, 15.2%, 3.2%, and 0.8%, respectively, exhibiting a logarithmic decreasing trend.

Figure 2. The change of PARi along the distance. Different letters indicate significant differences (P<0.05, Duncan’s test).

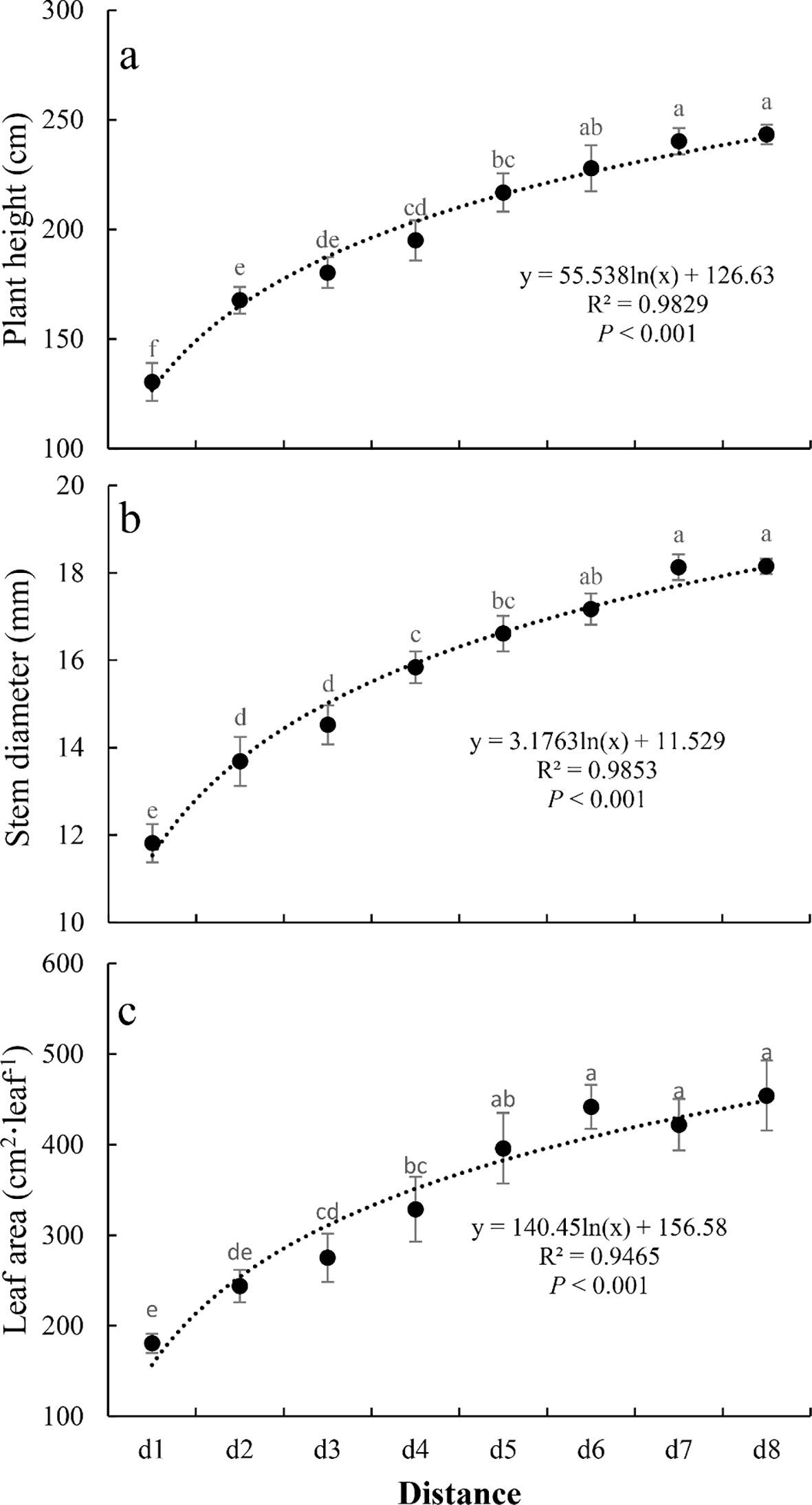

3.2 Plant morphology of summer maize

Summer maize plant height, stem diameter, and leaf area increased significantly with increasing distance from the interface (all P<0.001, Figure 3). The minimum and maximum values of these three morphological parameters all occurred in d1 and d8 locations, respectively. Relative to the maximum values, plant height, stem diameter, and leaf area at the minimum distance (d1) were reduced by 46%, 35%, and 60%, respectively, indicating that leaf area was most affected by distance, followed by plant height.

Figure 3. The change of plant morphology (plant height (a), stem diameter (b), and leaf area (c)) of summer maize along the distance. Different letters indicate significant differences (P<0.05, Duncan’s test).

Trend analysis revealed that all three morphological parameters followed significant logarithmic trends with increasing distance from d1 to d8 (all P<0.001, Figure 1). Plant height and stem diameter stabilized at d6, while leaf area stabilized at d5.

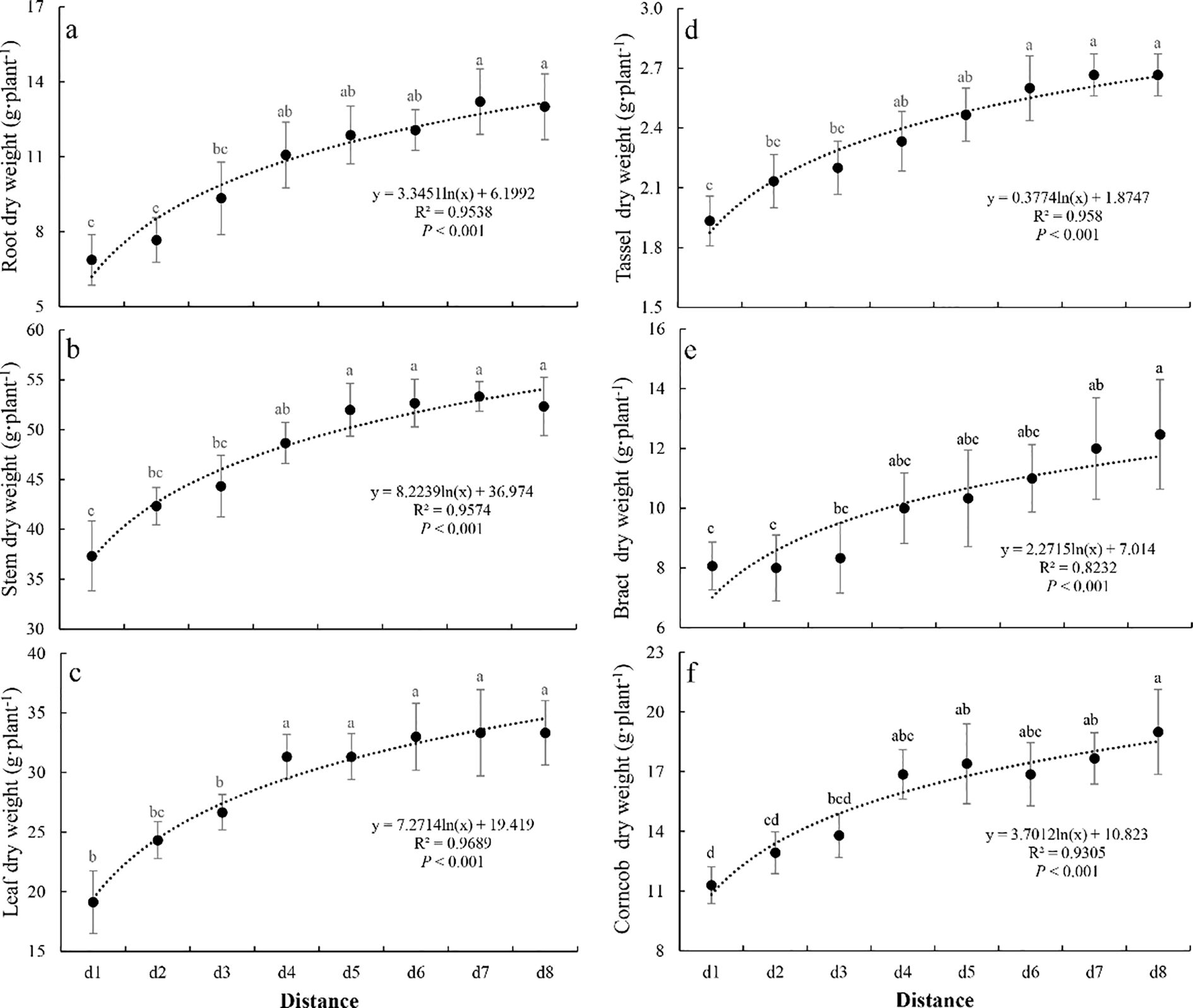

3.3 Dry matter distribution of summer maize

All six dry matter allocation parameters showed a significant increasing trend with increasing distance from the interface (all P<0.001, Figure 4). The minimum values for all parameters occurred in the d1 location, while the maximum values showed some variation: root and stem dry weight peaked at d7, whereas bract and corncob dry weight reached their maxima at d8. Compared to their respective maximum values, root, stem, leaf, tassel, bract, and corncob dry weight at d1 were reduced by 48.0%, 30.0%, 42.6%, 27.5%, 35.3%, and 40.5%, respectively. All six dry matter allocation parameters followed significant logarithmic trends from d1 to d8 (all P<0.001, Figure 4), and stabilized at D4.

Figure 4. The change of dry matter distribution (root (a), stem (b), leaf (c), tassel (d), bract (e), and corncob (f) dry weight) of summer maize along the distance. Different letters indicate significant differences (P<0.05, Duncan’s test).

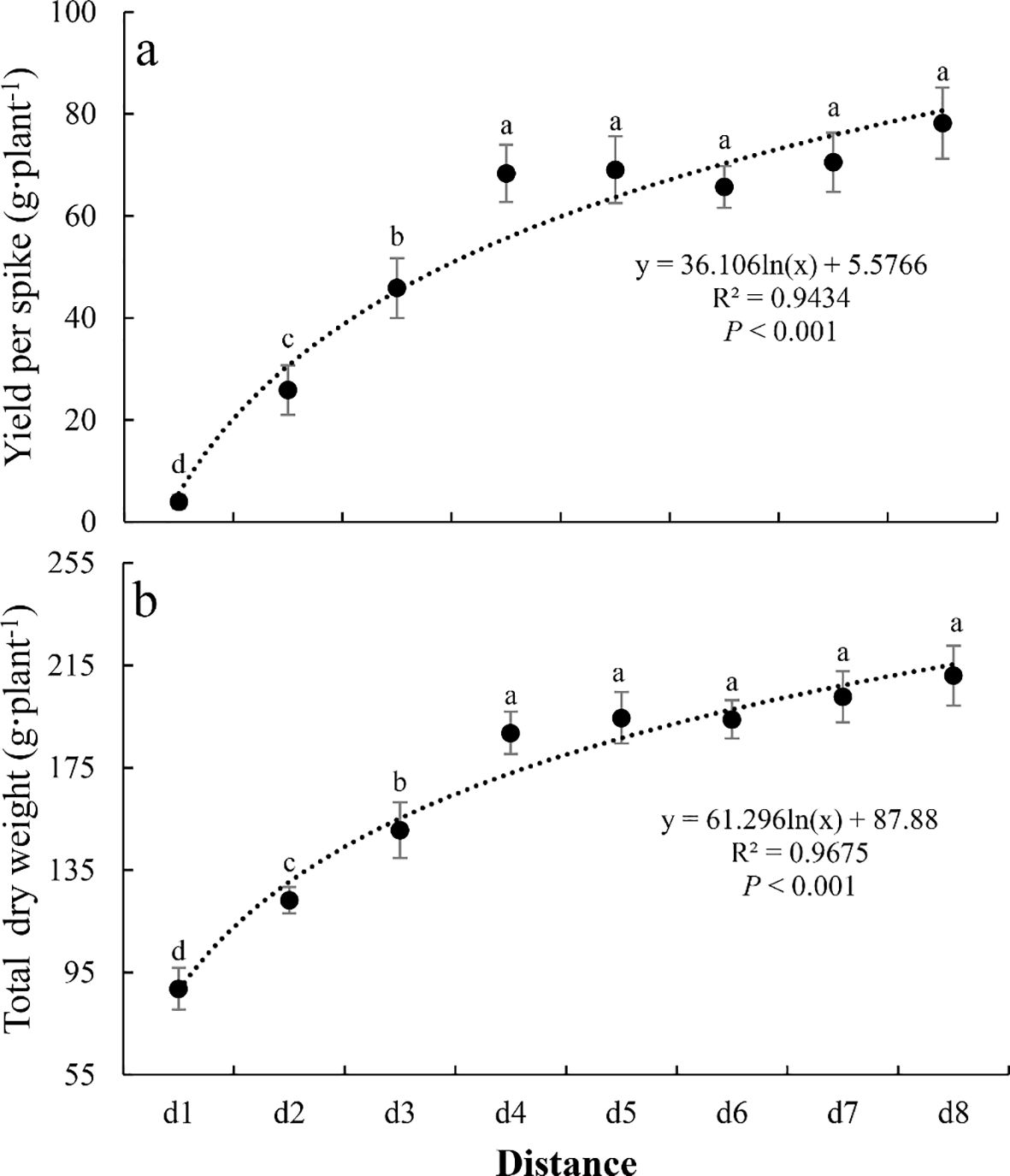

3.4 Yield index of summer maize

Both yield per spike and total dry weight showed a significant increasing trend with increasing distance, stabilizing at the d4 location (both P<0.001, Figure 5). The minimum values occurred at d1 (4.0g and 88.6g for yield per spike and total dry weight, respectively), while the maximum values were observed at d8 (78.2g and 211.0g, respectively). Compared to their respective maximum values, the yield per spike and total dry weight at d1 were reduced by 94.9% and 58.0%, respectively. Relative to the maximum values, the d2 and d3 locations showed reductions of 66.9% and 41.3% in yield per spike, and 41.6% and 28.7% in total dry weight, respectively.

Figure 5. The change of yield (yield per spike (a) and total dry weight (b)) of summer maize along the distance. Different letters indicate significant differences (P<0.05, Duncan’s test).

3.5 Comparative analysis of the parameters in the fitting equations

Comparative analysis of correlation trends among different parameters revealed that morphological structure, dry matter distribution, and yield all exhibited significant logarithmic increases with distance (Table 1). However, the slopes of the fitted equations varied significantly across different parameters. The tassel dry weight had the smallest slope (0.38), while the leaf area exhibited the largest slope (140.45). This indicates that although all parameters were influenced by poplar trees, the degree of impact varied considerably. Furthermore, the fitted equations for plant height, single ear yield, total dry weight, and leaf area all exhibited high slopes (all greater than 36), suggesting these parameters were particularly sensitive to poplar influence. In contrast, the fitted equations for other parameters showed relatively low slopes (all below 10), indicating their ability to maintain relative stability under the influence of poplar trees.

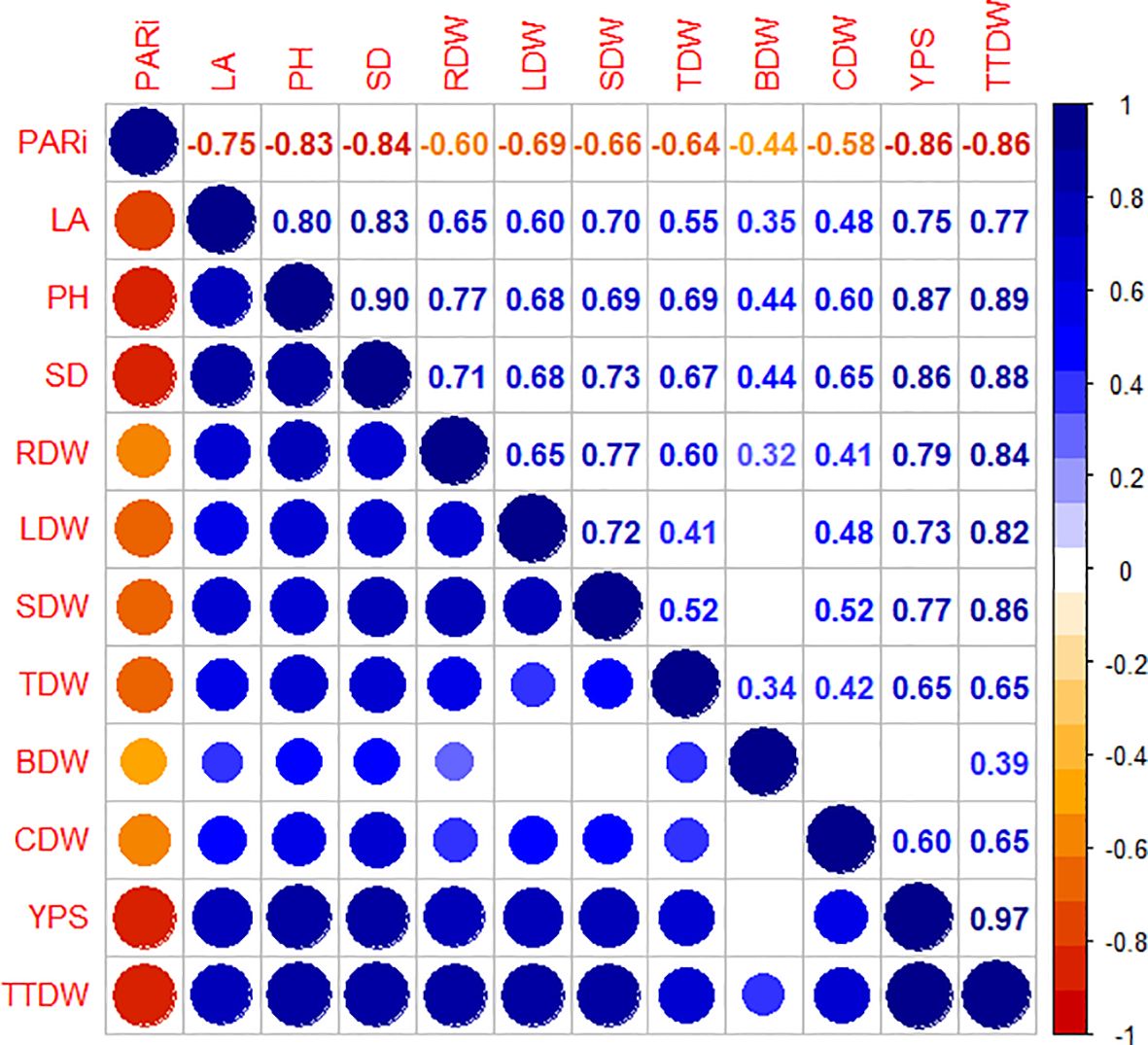

3.6 Path analysis for effects of plant morphology and dry matter distribution on yield of summer maize

Correlation analysis revealed significant relationships between yield parameters of summer maize and plant morphology as well as dry matter distribution parameters in the agroforestry system (Figure 6). All parameters exhibited positive correlations with each other, with the exception of PARi, which showed negative correlations with the other parameters. Yield per spike and total dry weight exhibited significant negative correlations with PARi, but showed significant positive correlations with all other parameters. To identify the key influencing factors on yield parameters, we focused on parameters showing correlation coefficients greater than 0.7 for subsequent analysis.

Figure 6. Correlation graph of yield index, plant morphology, and dry matter distribution. The size of circles and numbers both indicate the correlation between parameters. The meaning of the abbreviations: PARi, intercepted PAR; LA, leaf area; PH, plant height; SD, stem diameter; RDW, root dry weight; LDW, leaf dry weight; SDW, stem dry weight; TDW, tassel dry weight; BDW, bract dry weight; CDW, corncob dry weight; YPS, yield per spike; TTDW, total dry weight.

Path analysis demonstrated strong interdependence between yield per spike and total dry weight (R² = 0.952, Figure 7). Variations in root dry weight (R² = 0.308) and leaf dry weight (R² = 0.187) exerted positive effects on yield per spike. Similarly, root dry weight (R² = 0.246), stem dry weight (R² = 0.180), and leaf dry weight (R² = 0.263) significantly influenced total dry weight. Both leaf area and plant height exhibited indirect positive effects on both yield per spike and total dry weight (Figure 7). Interestingly, stem diameter demonstrated both direct and indirect effects on these yield parameters. However, PARi exerts a negative impact on yield per spike and total dry weight through LDW and RDW.

Figure 7. Structural equation model (SEM) analysis of causal relationships of yield per spike and total dry weight to changes in stem diameter, plant height, leaf area, root dry weight, stem dry weight, and leaf dry weight of summer maize in an agroforestry system. All arrows represent significant relationships (P<0.05). Results of the model fitting: χ2 = 26.85, P=0.217, df = 22, GFI=0.989, CFI=0.992, RMSEA=0.074. The number adjacent to each arrowed line is a factor loading (R2) that shows the variance explained by the variable. ^, *, **, and *** indicate significant differences at the 0.1 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001 probability levels, respectively. The solid black line represents a positive correlation, the dashed black line represents a negative correlation, and the thickness of the lines indicates the strength of the correlation.

4 Discussions

4.1 The effect of poplar planting on yield of maize

Agroforestry systems are increasingly recognized for their potential to enhance climate resilience and contribute to sustainable agricultural development (Chemura et al., 2021; Scordia et al., 2023). However, considerable debate persists regarding their impacts on crops, particularly regarding crop yields (Baier et al., 2023; Raatz et al., 2019; Scordia et al., 2023). The tree-crop relationship is influenced by multiple factors, including system complexity, management practices, and local geography (Baier et al., 2023; Majaura et al., 2024). Well-designed agroforestry systems typically aim for win-win outcomes, thereby promoting positive tree-crop interactions (Baier et al., 2023). By contrast, poorly designed systems in transition zones often exert greater negative impacts on crop production (Baier et al., 2023; Yang et al., 2023).

This study was conducted in a non-standardized agroforestry transition zone where competition between trees and crops is likely significantly more intense than in intensively managed agroforestry systems. The results indicate that the yield per maize plant reached its maximum at site d8 (78.2g) and decreased to its lowest level at site d1 (4g), representing a maximum yield reduction of 94.9%. This finding is consistent with the trend reported in most previous studies, but demonstrates a more pronounced negative effect (Scordia et al., 2023; Yang et al., 2023). A study on a rubber-peanut agroforestry system revealed that crop yield increases with greater distance from the rubber trees, with light availability identified as the primary influencing factor (Huang et al., 2020a). Furthermore, a meta-analysis demonstrated that tree-crop systems can lead to an average crop yield reduction of 48.8% (Yang et al., 2023). The same study also indicated that poplar exerts the most substantial negative impact on crop yield among tree species, while factors such as tree characteristics, crop species, and climate zone significantly modulate the overall effect (Yang et al., 2023). Therefore, the phenomena observed in this study can be attributed to the following factors: Extensive agricultural research has shown that maize yield is influenced by multiple variables (Ding and Su, 2010; Liu et al., 2023a; Lobell et al., 2014), including sunlight availability, soil nutrients, water supply, microclimate conditions, and soil microbial activity (Ruthes et al., 2023; Skarpa et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2024; Zai et al., 2024). This study was conducted in the humid and semi-humid regions of China, with mean annual precipitation of 1100mm. Our results also indicate that soil moisture exhibits minor, yet statistically insignificant variations over distance (data not shown). Moisture is likely not a primary limiting factor in this region. Thus, in this study, poplar shade emerged as a potentially critical factor affecting maize productivity. Two primary mechanisms were identified: First, maize was planted on the northern side of poplars, where extended shading distance led to progressively lower yields. Second, higher-density poplar canopies generated more pronounced shading effects (Peng et al., 2015). Additionally, as a C4 photosynthetic pathway crop, maize exhibits high sensitivity to light limitation (Peng et al., 2009). Numerous studies have shown that farmland soil moisture is highly susceptible to the influence of adjacent trees (Huang et al., 2020b). Trees and crops often compete for topsoil water, and the closer the distance to the trees, the lower the topsoil moisture content (Rivest and Vézina, 2015). However, no significant changes in soil moisture were detected in our study. This lack of variation is likely attributable to the humid and semi-humid climate of the region, where the high annual rainfall compensated for the influence of poplar trees on surrounding soil moisture. It should be noted that the poplar trees selected in this study are large, mature specimens (with an average diameter at breast height of ~28.5 cm and height of ~17 m), which may exert a more pronounced influence on maize yield (Wolz et al., 2017). Of course, many other factors, such as field management practices, annual precipitation, and temperature, could also affect maize productivity.

4.2 The effect of poplar planting on the distribution of dry matter in maize

The dry matter content of maize serves as an important indicator of harvest potential (Wu et al., 2024), yet it has received limited attention in agroforestry research. This study demonstrates that poplar planting influences maize growth and morphological structure, thereby altering dry matter distribution and ultimately reducing total dry matter accumulation and yield (Figure 5). Near poplars, maize growth characteristics (e.g., leaf area, plant height, and stem diameter) are significantly impaired by resource competition, and since these traits directly govern dry matter partitioning, their decline negatively impacts plant dry weight and yield—a pattern consistent with prior findings (Guo et al., 2022; Sun et al., 2023). Reduced solar radiation diminishes maize photosynthetic capacity, leading to inadequate assimilate accumulation (Guo et al., 2022), while light limitation further restricts panicle development, disrupts male-female panicle balance, shortens the grain-filling period, and ultimately lowers yield (Yang et al., 2016; Zhong et al., 2014). Our data corroborate these effects, showing pronounced reductions in tassel dry matter near trees (Figure 3). Additionally, as the primary interface between plants and soil, root systems determine soil resource acquisition and growth potential (Singh et al., 2010), but under moisture or light stress, their impaired development further exacerbates yield and dry matter losses (Guo et al., 2022). A global analysis underscores that dry matter allocation dynamics during maize growth stages are critical for yield prediction (Liu et al., 2023b).

4.3 Research limitations and cropland management implications

Although this study provides clear evidence that long-term establishment of poplar-based economic forests significantly alters the morphological traits, dry matter allocation, and yield of adjacent maize, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, site-specific soil physicochemical properties (e.g., soil pH, texture, organic matter, and nutrient content) were not directly measured during field sampling. While regional soil survey data indicate that the study area is dominated by loamy soils with moderate fertility, variations in local soil conditions could partly contribute to the observed spatial differences in maize performance near the agroforestry interface. Therefore, future studies should integrate detailed soil measurements—such as nutrient availability, root-zone moisture, and microbial activity—to better disentangle the belowground mechanisms driving crop responses. Moreover, studies have also indicated that agroforestry systems can lead to variations in field microclimate factors (such as air temperature, wind speed, and relative humidity) with increasing distance from trees (Cleugh, 1998; Kanzler et al., 2019). These microclimatic changes may adversely affect crop yields to some extent and should be given greater attention in future research. It should be noted that this study did not include measurements of plot-scale microclimate conditions, which limits a more detailed mechanistic interpretation of the observed effects. Nevertheless, the consistent trends in plant growth parameters and yield across different buffer distances provide robust empirical evidence for establishing practical management guidelines.

While numerous studies have documented win-win benefits of agroforestry systems (Verma et al., 2023), their negative impacts on crop production remain a critical concern (Yang et al., 2023). The conversion of arable land poses significant challenges both in China and globally (Sabir et al., 2024), with dual consequences: direct reduction of cultivated area affecting food output, and indirect yield losses in adjacent fields through resource competition. The spatial extent of these impacts shows considerable variability, influenced by tree characteristics (age, height, species, and planting density) (Baier et al., 2023) and crop type (Majaura et al., 2024). This complexity underscores the need for further research to quantify how land-use transitions may compromise food security.

Our results, which indicate a significant yield reduction in corn adjacent to a poplar tree line, contrast with studies reporting yield benefits in other agroforestry systems. For instance, in alley cropping systems with widely spaced tree rows and careful species selection (e.g., olive with legume crops), the microclimate modifications and soil improvements can lead to stable or even enhanced crop yields in the alleys (Amassaghrou et al., 2023). Similarly, optimization of boundary spacing has been demonstrated to minimize shading competition while maximizing beneficial edge effects (Peng et al., 2015). In a similar poplar-based agroforestry system in Germany, the width of crop alleys was found to have no significant effect on the overall crop yield of rapeseed, winter wheat, and winter barley (Lamerre, 2016). The divergent outcomes observed in our study may stem from the specific context of dense poplar stand borders in humid/semi-humid regions, where ample precipitation, suitable temperatures, and sufficient fertilization mitigate resource limitations, thus making light competition the predominant influencing factor. This underscores that the net effect of agroforestry is highly dependent on specific system design, tree and crop species, and environmental conditions.

5 Conclusions

This study investigates the effects of converting cropland to forest by examining the interface between poplar and summer maize. The results indicate that long-term poplar planting has adverse effects on the morphological structure, yield, and dry matter distribution of neighboring summer maize, with the magnitude of impact decreasing logarithmically as distance increases. Additionally, significant variations were observed in the responses of different parameters. The most affected parameter was yield per spike, which showed a maximum reduction of 94.9% compared to the control. This was followed by leaf area and total dry weight, with maximum reductions of 60.2% and 58.0%, respectively. Analysis of the response distance revealed that all parameters (light availability, dry matter allocation, and yield) became statistically insignificant beyond a distance of 4 meters, with the exception of morphological structure, which showed non-significant effects after exceeding 5–6 meters. Furthermore, structural equation modeling revealed that poplar cultivation primarily affects summer maize yield through morphological structure and varying dry matter distribution, exerting varying degrees of direct and indirect influences that ultimately reduce yield per spike and total dry matter. Therefore, to ensure that maize yield is not affected by long-term poplar planting in this region, a minimum buffer distance of at least 4 meters should be maintained between the tree line and maize fields. These findings provide insights into the processes underlying the negative effects of extensive management in agroforestry systems on grain production in humid and semi-humid regions. Moreover, future assessments of the impact of cultivated land conversion on grain production should consider not only the direct loss of cultivated land area but also the secondary effects of plantations on adjacent crops.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MZ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XL: Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft. JL: Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft. JT: Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft. ZZ: Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft. BC: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was financially supported by the Henan Province Science and Technology Research Projects (No. 242102321157 and 242102521061) and Postgraduate Education Reform and Quality Improvement Project of Henan Province (YJS2022JD30).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Amassaghrou A., Barkaoui K., Bouaziz A., Alaoui S. B., Fatemi Z. E. A., and Daoui K. (2023). Yield and related traits of three legume crops grown in olive-based agroforestry under an intense drought in the South Mediterranean. Saudi. J. Biol. Sci. 30, 103597. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2023.103597

Bai W., Sun Z., Zheng J., Du G., Feng L., Cai Q., et al. (2016). Mixing trees and crops increases land and water use efficiencies in a semi-arid area. Agr. Water Manage. 178, 281–290. doi: 10.1016/j.agwat.2016.10.007

Baier C., Gross A., Thevs N., and Glaser B. (2023). Effects of agroforestry on grain yield of maize (Zea mays L.)—A global meta-analysis. Front. Sus. Food Syst. 7. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2023.1167686

Chemura A., Yalew A. W., and Gornott C. (2021). Quantifying agroforestry yield buffering potential under climate change in the smallholder maize farming systems of Ethiopia. Front. Agron. 3. doi: 10.3389/fagro.2021.609536

Chen C.-N., Liao C.-S., Tzou Y.-M., Lin Y.-T., Chang E.-H., and Jien S.-H. (2024). Soil quality and microbial communities in subtropical slope lands under different agricultural management practices. Front. Microbiol. 14. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1242217

Cleugh H. A. (1998). Effects of windbreaks on airflow, microclimates and crop yields. Agroforest. Syst. 41, 55–84. doi: 10.1023/a:1006019805109

Cui X. M. and Zhong Z. (2024). Climate change, cropland adjustments, and food security: Evidence from China. J. Dev. Econ. 167, 103245. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2023.103245

Dai Y. S., Yang T., Shen L., Wang X. Y., Zhang W. L., Liu T. T., et al. (2021). Root growth, distribution, and physiological characteristics of alfalfa in a poplar/alfalfa silvopastoral system compared to sole-cropping in northwest Xinjiang, China. Agroforest. Syst. 95, 1137–1153. doi: 10.1007/s10457-021-00639-1

Ding S. and Su P. (2010). Effects of tree shading on maize crop within a Poplar-maize compound system in Hexi Corridor oasis, northwestern China. Agroforest. Syst. 80, 117–129. doi: 10.1007/s10457-010-9287-x

Fernández M. E., Gyenge J. E., and Schlichter T. M. (2007). Balance of competitive and facilitative effects of exotic trees on a native patagonian grass. Plant Ecol. 188, 67–76. doi: 10.1007/sll258-006-9148-x

Guo X., Yang Y., Liu H., Liu G., Liu W., Wang Y., et al. (2022). Effects of solar radiation on dry matter distribution and root morphology of high yielding maize cultivars. Agriculture 12, 299. doi: 10.3390/agriculture12020299

Hildreth L. A. (2008). The economic impacts of agroforestry in the Northern Plains of China. Agroforest. Syst. 72, 119–126. doi: 10.1007/s10457-007-9060-y

Huang J. X., Pan J., Zhou L. J., Yuan S. N., and Lin W. F. (2020a). Effect of light deficiency on productivity of intercrops in rubber-crop agroforestry system. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 28, 680–689. doi: 10.13930/j.cnki.cjea.190858

Huang Z., Yang W.-J., Liu Y., Shen W., López-Vicente M., and Wu G.-L. (2020b). Belowground soil water response in the afforestation-cropland interface under semi-arid conditions. Catena 193, 104660. doi: 10.1016/j.catena.2020.104660

Kanzler M., Böhm C., Mirck J., Schmitt D., and Veste M. (2019). Microclimate effects on evaporation and winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) yield within a temperate agroforestry system. Agroforest. Syst. 93, 1821–1841. doi: 10.1007/s10457-018-0289-4

Karvatte N., Miyagi E. S., de Oliveira C. C., Barreto C. D., Mastelaro A. P., Bungenstab D. J., et al. (2020). Infrared thermography for microclimate assessment in agroforestry systems. Sci. Total Environ. 731, 139252. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139252

Khan A., Bajwa G. A., Yang X., Hayat M., Muhammad J., Ali F., et al. (2022). Determining effect of tree on wheat growth and yield parameters at three tree-base distances in wheat/Jand (Prosopis cineraria) agroforestry systems. Agroforest. Syst. 97, 187–196. doi: 10.1007/s10457-022-00797-w

Lamerre J. (2016). Above-ground interactions and yield effects in a short-rotation alley-cropping agroforestry system. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitäts-und Landesbibliothek Sachsen-Anhalt, Halle-Wittenberg, Germany.

Li S. and Li X. (2016). Progress and prospect on farmland abandonment. Acta Geogr. Sin. 71, 370–389. doi: 10.11821/dlxb201603002

Liu Z., Gao J., Zhao S., Sha Y., Huang Y., Hao Z., et al. (2023a). Nitrogen responsiveness of leaf growth, radiation use efficiency and grain yield of maize (Zea mays L.) in Northeast China. Field Crop Res. 291, 108806. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2022.108806

Liu G. Z., Yang Y. S., Guo X. X., Liu W. M., Xie R. Z., Ming B., et al. (2023b). A global analysis of dry matter accumulation and allocation for maize yield breakthrough from 1.0 to 25.0 Mg ha-1. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 188, 106656. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2022.106656

Liu Y. S. and Zhou Y. (2021). Reflections on China’s food security and land use policy under rapid urbanization. Land Use Policy 109, 105699. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105699

Lobell D. B., Roberts M. J., Schlenker W., Braun N., Little B. B., Rejesus R. M., et al. (2014). Greater sensitivity to drought accompanies maize yield increase in the U.S. Midwest. Science 344, 516–519. doi: 10.1126/science.1251423

Loreau M. and Hector A. (2001). Partitioning selection and complementarity in biodiversity experiments. Nature 412, 72–76. doi: 10.1038/35083573

Ma X. Y. and Zhou G. S. (2013). Method of determining the maximum leaf area index of spring maize and its application. Acta Ecol. Sin. 33, 2596–2603. doi: 10.5846/stxb201206040808

Majaura M., Böhm C., and Freese D. (2024). The influence of trees on crop yields in temperate zone alley cropping systems: A review. Sustainability 16, 3301. doi: 10.3390/su16083301

Molotoks A., Smith P., and Dawson T. P. (2021). Impacts of land use, population, and climate change on global food security. Food Energy Secur. 10, e261. doi: 10.1002/fes3.261

Muchane M. N., Sileshi G. W., Gripenberg S., Jonsson M., Pumariño L., and Barrios E. (2020). Agroforestry boosts soil health in the humid and sub-humid tropics: A meta-analysis. Agr. Ecosyt. Environ. 295, 106899. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2020.106899

Peng X., Thevathasan N. V., Gordon A. M., Mohammed I., and Gao P. (2015). Photosynthetic response of soybean to microclimate in 26-year-old tree-based intercropping systems in southern Ontario, Canada. PLoS One 10, e0129467. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129467

Peng X., Zhang Y., Cai J., Jiang Z., and Zhang S. (2009). Photosynthesis, growth and yield of soybean and maize in a tree-based agroforestry intercropping system on the Loess Plateau. Agroforest. Syst. 76, 569–577. doi: 10.1007/s10457-009-9227-9

Pohlmann V., Schöffel E. R., Eicholz E. D., Guarino E. D. G., Scheer G. R., Franz E. V., et al. (2024). Corn and bean growth and production in agroforestry systems. Agroforest. Syst. 98, 2811–2827. doi: 10.1007/s10457-024-00959-y

Qu L., Liu K., Zhi J., Liu W., Fu X., Fan T., et al. (2025). Spatiotemporal dynamics and driving factors of cultivated land fragmentation across China from 1990 to 2020. Landsc. Ecol. 40, 150. doi: 10.1007/s10980-025-02166-1

Raatz L., Bacchi N., Pirhofer Walzl K., Glemnitz M., Müller M. E. H., Joshi J., et al. (2019). How much do we really lose?—Yield losses in the proximity of natural landscape elements in agricultural landscapes. Ecol. Evol. 9, 7838–7848. doi: 10.1002/ece3.5370

Ramesh K. R., Deshmukh H. K., Sivakumar K., Guleria V., Umedsinh R. D., Krishnakumar N., et al. (2023). Influence of eucalyptus agroforestry on crop yields, soil properties, and system economics in southern regions of India. Sustainability 15, 3797. doi: 10.3390/su15043797

Richardson J. and Isebrands J. G. (2014). Poplars and Willows Trees for Society and the Environment Epilogue (Wallingford: Cabi Publishing-C a B Int). doi: 10.1079/9781780641089.0000

Rivest D. and Vézina A. (2015). Maize yield patterns on the leeward side of tree windbreaks are site-specific and depend on rainfall conditions in eastern Canada. Agroforest. Syst. 89, 237–246. doi: 10.1007/s10457-014-9758-6

Ruthes B. E. S., Kaschuk G., de Moraes A., Lang C. R., Crestani C., and de Oliveira L. B. (2023). Soil microbial biomass, N nutrition index, and yield of maize cultivated under eucalyptus shade in integrated crop-livestock-forestry systems. Int. J. Plant Prod. 17, 323–335. doi: 10.1007/s42106-023-00242-7

Sabir M., Li M., Li J., Haq S., and Nadeem M. (2024). Agriculture land use transformation: A threat to sustainable food production systems, rural food security, and farmer well-being? PLoS One 19, e0296332. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0296332

Sahu S. K. and Liu H. (2023). A genetic solution for the global food security crisis. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 65, 1359–1361. doi: 10.1111/jipb.13500

Saj S., Jagoret P., Ngnogue H. T., and Tixier P. (2023). Effect of neighbouring perennials on cocoa tree pod production in complex agroforestry systems in Cameroon. Eur. J. Agron. 146, 126810. doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2023.126810

Scordia D., Corinzia S. A., Coello J., Vilaplana Ventura R., Jiménez-De-Santiago D. E., Singla Just B., et al. (2023). Are agroforestry systems more productive than monocultures in Mediterranean countries? A meta-analysis. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 43, 73. doi: 10.1007/s13593-023-00927-3

Sethumadhavan A., Liang T., and Mangal V. (2024). Emerging investigator series: impacts of land use on dissolved organic matter quality in agricultural watersheds: a molecular perspective. Environ. Sci.-Process Impacts 26, 247–258. doi: 10.1039/d3em00506b

Singh V., van Oosterom E. J., Jordan D. R., Messina C. D., Cooper M., and Hammer G. L. (2010). Morphological and architectural development of root systems in sorghum and maize. Plant Soil 333, 287–299. doi: 10.1007/s11104-010-0343-0

Skarpa P., Jancar J., Lepcio P., Antosovsky J., Klofac D., Kriska T., et al. (2023). Effect of fertilizers enriched with bio-based carriers on selected growth parameters, grain yield and grain quality of maize (Zea mays L.). Eur. J. Agron. 143, 126714. doi: 10.1016/j.eja.2022.126714

Sun H., Li W., Liang Y., and Li G. (2023). Shading stress at different grain filling stages affects dry matter and nitrogen accumulation and remobilization in fresh waxy maize. Plants 12, 1742. doi: 10.3390/plants12091742

Vaccaro C., Six J., and Schöb C. (2022). Moderate shading did not affect barley yield in temperate silvoarable agroforestry systems. Agroforest. Syst. 96, 799–810. doi: 10.1007/s10457-022-00740-z

Veldkamp E., Schmidt M., Markwitz C., Beule L., Beuschel R., Biertümpfel A., et al. (2023). Multifunctionality of temperate alley-cropping agroforestry outperforms open cropland and grassland. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 20. doi: 10.1038/s43247-023-00680-1

Verma T., Bhardwaj D. R., Sharma U., Sharma P., Kumar D., Kumar A., et al. (2023). Agroforestry systems in the mid-hills of the north-western Himalaya: A sustainable pathway to improved soil health and climate resilience. J. Environ. Manage. 348, 119264. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.119264

Wang X. (2022). Managing land carrying capacity: key to achieving sustainable production systems for food security. Land 11, 484. doi: 10.3390/land11040484

Wang S., Fan T., Zhao G., Ma M., Lei K., Li S., et al. (2024). Effect of integrated fertilizer and plant density management on yield, root characteristic and photosynthetic parameters in maize on the semiarid Loess Plateau. Front. Agron. 6. doi: 10.3389/fagro.2024.1358127

Wang B., Zhu L., Yang T., Qian Z. Z., Xu C., Tian D., et al. (2022). Poplar agroforestry systems in eastern China enhance the spatiotemporal stability of soil microbial community structure and metabolism. Land Degrad. Dev. 33, 916–930. doi: 10.1002/ldr.4199

Wolz K. J., Lovell S. T., Branham B. E., Eddy W. C., Keeley K., Revord R. S., et al. (2017). Frontiers in alley cropping: Transformative solutions for temperate agriculture. Glob. Change Biol. 24, 883–894. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13986

Wu B., Cui Z., Zechariah E., Guo L., Gao Y., Yan B., et al. (2024). Post-anthesis dry matter and nitrogen accumulation, partitioning, and translocation in maize under different nitrate–ammonium ratios in Northwestern China. Front. Plant Sci. 15. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2024.1257882

Xi B., Clothier B., Coleman M., Duan J., Hu W., Li D., et al. (2021). Irrigation management in poplar (Populus spp.) plantations: A review. For. Ecol. Manage. 494, 119330. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2021.119330

Xu S. Q., Wang R., Gasser T., Ciais P., Peñuelas J., Balkanski Y., et al. (2022). Delayed use of bioenergy crops might threaten climate and food security. Nature 609, 299–306. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05055-8

Yang T., Ouyang X. Y., Wang B., Tian D., Xu C., Lin Z. Y., et al. (2023). Understanding the effects of tree-crop intercropping systems on crop production in China by combining field experiments with a meta-analysis. Agricult. Syst. 210, 103705. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2023.103705

Yang H., Shi Y., Xu R., Lu D., and Lu W. (2016). Effects of shading after pollination on kernel filling and physicochemical quality traits of waxy maize. Crop J. 4, 235–245. doi: 10.1016/j.cj.2015.12.004

Zai F. H., McSharry P. E., and Hamers H. (2024). Impact of climate change and genetic development on Iowa corn yield. Front. Agron. 6. doi: 10.3389/fagro.2024.1339410

Zeng J., Cui X., Chen W., and Yao X. (2023). Impact of urban expansion on the supply-demand balance of ecosystem services: An analysis of prefecture-level cities in China. Environ. Impact. Asses. 99, 107003. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2022.107003

Zeng J., Luo T., Chen W., and Gu T. (2024). Assessing and mapping cropland abandonment risk in China. Land Degrad. Dev. 35, 2738–2753. doi: 10.1002/ldr.5080

Zhong M., Liu C., Wang X., Hu W., Qiao N., Song H., et al. (2022). Belowground root competition alters the grass seedling establishment response to light by a nitrogen addition and mowing experiment in a temperate steppe. Front. Plant Sci. 13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.801343

Zhong X. M., Shi Z. S., Li F. H., and Huang H. J. (2014). Photosynthesis and chlorophyll fluorescence of infertile and fertile stalks of paired near-isogenic lines in maize (Zea mays L.) under shade conditions. Photosynthetica 52, 597–603. doi: 10.1007/s11099-014-0071-4

Zhong M., Song J., Zhou Z., Ru J., Zheng M., Li Y., et al. (2019). Asymmetric responses of plant community structure and composition to precipitation variabilities in a semi-arid steppe. Oecologia 191, 697–708. doi: 10.1007/s00442-019-04520-y

Keywords: agroforestry system, dry matter distribution, grain yield, plant morphology, poplar, summer maize

Citation: Zhong M, Li X, Li J, Tang J, Zhao Z and Cao B (2025) The effect of long-term planting of poplar trees on the morphology and yield of neighboring summer maize on cropland in humid and semi humid regions of China. Front. Agron. 7:1652457. doi: 10.3389/fagro.2025.1652457

Received: 23 June 2025; Accepted: 23 October 2025;

Published: 26 November 2025.

Edited by:

Venkatesh Paramesha, Central Coastal Agricultural Research Institute (ICAR), IndiaReviewed by:

Zhao Wang, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, ChinaNamitha V. V, Kerala Agricultural University, India

Copyright © 2025 Zhong, Li, Li, Tang, Zhao and Cao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Boning Cao, Ym9uaW5nY2FvQGhvdG1haWwuY29t

Mingxing Zhong

Mingxing Zhong Xiuge Li1

Xiuge Li1