- 1Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Mahasarakham University, Maha Sarakham, Thailand

- 2The Northeastern Soil Salinity Research Unit, Faculty of Science, Mahasarakham University, Maha Sarakham, Thailand

- 3Department of Mathematics, Faculty of Science, Mahasarakham University, Maha Sarakham, Thailand

- 4Omics Science and Bioinformatics Center, Faculty of Science, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand

- 5Plantatation productivity and clonal development section, The Siam Forestry Co, LTD., Khonkaen, Thailand

- 6Medical Biotechnology, College of Medicine and Public Health, Flinders University, Adelaide, SA, Australia

This is the first report of the application of six endophytic actinobacteria, isolated from eucalyptus trees growing in a saline soil, to test their effects on eucalyptus growth. This study aims to examine six selected strains to promote eucalyptus growth under drought, heat, and salinity conditions. Genomes of the three selected strains were analyzed to reveal significant genetic traits that may contribute to stress tolerance in eucalyptus. Eucalyptus seeds soaked with spores of each of the six actinobacteria were grown hydroponically for 41 days with natural heat wave conditions. Strain A2 gave the highest shoot and root length, plant fresh (PF) weight, and number of lateral roots, which were significantly higher than the control. Strain A3 gave the highest chlorophyll a (Ch a) and chlorophyll b (Ch b), and plant dry weight and leaf area were significantly higher than the control. Furthermore, the six actinobacterial strains were tested for seedling length vigor index (SLVI) at 0, 50, 100, 150, and 200 mM NaCl, and the result indicated that strain A5 was the best, having the highest SLVI at 200 mM NaCl. Strains A2, A3, and A5 were selected to test plant growth promoting (PGP) activity in eucalyptus cuttings under three different conditions: drought, limited water with heat stress (less than 40°C), and heat stress (40-42°C). Strains A2, A3, and A5 showed a negative impact on cuttings with a stress severity index (SSI) higher than the control in drought and heat stress (40-42°C). Strains A3 and A5 showed lower SSI than the control and strain A2 in limited water with heat stress (38-39°C). Insights into three genomes of strains A2, A3, and A5 reveal biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) of antimicrobial compounds, ectoine, and siderophore production, including genes related to stress response. In conclusion, strain A3 exhibited a negative effect on plant growth in some circumstances, which means this strain is not suitable to use as a PGP in future applications. Endophytic actinobacteria strains A2 and A5 could support plant growth in hydroponic and saline conditions, and these selected strains could be used as inocula for eucalyptus plantations in the future.

Introduction

Eucalyptus is an economically valuable plant in Thailand. In 1991, there were 13.4 million hectares of eucalyptus plantations worldwide; by 2021, this figure had risen to 22.57 million hectares (Lin et al., 2023). Over the past 30 years, Thailand has experienced an even more rapid expansion, with the plantation area increasing from 94,000 hectares in 1987 to 846,708 hectares in 2023 (GISDA, 2023; Pousajja, 1993). The high demand for eucalyptus in Thailand is for pulpwood and paper, which exceeds 3.6 million tons annually (Manavakun, 2014). This rapid increase reflects not only the economic advantages associated with eucalyptus cultivation but also a growing awareness of its ecological benefits. As countries seek sustainable solutions for land management and reforestation, eucalyptus plantations are becoming essential components of environmental strategies aimed at addressing climate change and enhancing biodiversity.

The species primarily found in the country is Eucalyptus camaldulensis, known for its rapid growth and ability to tolerate salinity and drought. The eucalyptus tree has significant agricultural potential due to its deep root system, which helps absorb water and prevents salt intrusion, as well as its extensive bushy structure that reduces evaporation rates and detoxifies salt ions through organic matter. Marcar et al. (2002) studied E. camaldulensis Dehn. under salt stress conditions in Australia and demonstrated that E. camaldulensis is a moderately salt-tolerant species. E. camaldulensis was able to thrive in environments with 150 mM NaCl, elevated pH levels (pH 7.6 to 9.5), and combined NaCl and high pH solutions. Additionally, Cha-um et al. (2013) examined the effects of salinity on eucalyptus growth in Thailand, investigating the physiological and morphological responses of eucalyptus to varying salt concentrations (0.1-2.0% salt) in several field trials. Furthermore, Eucalyptus globulus, Eucalyptus grandis, and E. camaldulensis were tested for salt stress in field conditions at older ages (e.g., 10 years). The growth of eucalyptus was measured using an electromagnetic induction device (EM38), and soil salinity was consistent with differences in tree survival rates, stand volume, and leaf area index (Feikema and Baker, 2011).

Another critical plant stress is drought, which negatively impacts plant cells, leading to nutrient imbalance, photosynthesis disturbances, and impaired organelle functions. Prolonged drought reduces carbon assimilation, causing over-generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and methylglyoxal (MG), which can oxidize cellular components, causing oxidative damage and cell death. To protect against these effects, plant cells develop intrinsic mechanisms like glutathione-dependent ROS detoxification and MG detoxification, which play crucial roles in managing water-deficit stress (Nguyen et al., 2019).

Heat stress (HS) results in significant agricultural losses globally. The average world temperature is constantly rising, and this alteration is anticipated to have detrimental consequences on crop productivity. HS induces anomalies in floral development, resulting in modified flower architecture, decreased flower size, or the formation of entirely sterile flowers. These alterations in floral structures result in compromised pollination and fertilization processes, ultimately diminishing fruit and seed yield (Resentini et al., 2023).

Organisms adapt to hyperosmotic environments, such as salinity conditions, by amassing organic osmolytes, or compatible solutes, which help adjust osmotic potential without impairing normal cellular activities. These solutes consist of carbohydrates, such as trehalose and inositol; amino acids and derivatives, such as proline and ectoine; and methylammonium and methylsulfonium compounds, such as glycine betaine and dimethylsulfoniopropionate, enabling survival in diverse environments (Kempf and Bremer, 1998). Glycine betaine is acquired through transport systems and synthesized from precursor choline via the choline-glycine betaine pathway. Choline is abundant in lipids and can be released through bacterial phospholipases. This pathway is used in bacteria, plants, and animals for osmoadaptation and salt stress responses (Yang et al., 2024).

Actinobacteria are the group of Gram-stain-positive, spore-forming filamentous bacteria whose spores can tolerate drought and stress conditions in the environment. Endophytic actinobacteria have been reported as plant growth promoting (PGP) bacteria to support plants in stress conditions such as heat and drought stress and saline soil. The mechanisms of actinobacteria to support plant growth in salt and drought stress include phytohormone production such as auxin, cytokinin, and gibberellin; production of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) deaminase to reduce ethylene gas; accumulation of osmoprotectants such as proline, glycine-betaine, and polyamine; accumulation of exopolysaccharides (EPS); and production of anti-oxidative enzymes to reduce oxidation stress (Feikema and Baker, 2011; Atouei et al., 2019). Sadeghi et al. (2012) reported that the halotolerant bacterium Streptomyces sp. produced indole acetic acid (IAA) to adjust the root structure of wheat under salt stress. Furthermore, some PGPB, Arthrobacter, Bacillus, Halomonas, Azospirillum, and Pseudomonas sp., produce cytokinin to help plants tolerate salt stress. Cytokinin is a plant hormone that supports plant growth, delays plant aging, and induces plant buds and tillers (García de Salamone et al., 2001).

Genome insight into PGPB will benefit the search for beneficial strains to promote eucalyptus growth under salinity, drought, and heat stress. For example, Brevibacterium sediminis MG-1 promotes plant growth under salt stress. The genome of this strain comprises the BGC of ectoine, the gene encoding siderophores, and gene clusters responsible for auxin biosynthesis (Lutfullin et al., 2022). In addition, Streptomyces chartreusis WZS021, which increased drought tolerance in sugarcane, comprised genes encoding nitrogen fixation, ACC deaminase, and IAA secretion. The genome of this strain has oxidoreductase genes encoding superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutamate dehydrogenase, succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase, proline dehydrogenase, and choline dehydrogenase, which contribute to plant resistance to stress (Wang et al., 2019). Moreover, Brevibacterium linens RS16 increased heat resistance in Eucalyptus grandis, and this strain showed a heat shock protein 70 gene (DnaK) expression profile that supports the heat tolerance of bacteria (Chatterjee et al., 2020). In Arthrobacter nitroguajacolicus-primed wheat under salt stress, various genes from stilbenoid, flavonoid, phenylpropanoid, terpenoid, porphyrin, chlorophyll metabolism, and diarylheptanoid metabolism pathways were differentially expressed within inoculated roots (Safdarian et al., 2019). Streptomyces sp. KLBMP5084 significantly promoted tomato seedling growth under salt stress, in which the antioxidant enzyme activity, soluble sugar, and proline contents in leaf and stem effectively increased, while malondialdehyde (MDA) was decreased. Furthermore, genes associated with the photosynthesis-antenna protein pathway, zeatin biosynthesis, isoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis, and endoplasmic reticulum protein processing pathway were significantly upregulated (Gong et al., 2020).

The aim of this work was to study six selected strains of endophytic actinobacteria isolated from Eucalyptus camaldulensis plants grown in saline soil to promote Eucalyptus growth under drought, heat, and salinity conditions. Genomes of three selected strains were analyzed to reveal significant genetic traits that may contribute to stress tolerance in eucalyptus, which indicates the potential for these endophytic actinobacteria to enhance plant resilience.

Materials and methods

Endophytic actinobacterial strains

Six strains of the genus Streptomyces isolated from Eucalyptus camaldulensis tissues from plants grown in saline soil could inhibit fungal pathogens, Pseudoplagiostroma eucalypti LS6 and Cladosporium sp. LB1, and promote plant growth in vitro from the previous study and were selected for this study (Kaewkla et al., 2025). There were strains ECL5.5 (A1), ECR3.8 (A2), EKS3.2 (A3), EKL5.16 (A4), ESR1.13 (A5), and ECR6.5 (A6) belonging to the genus Streptomyces. The study coded these isolates as A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, and A6, respectively.

16S rRNA gene sequence and phylogenetic tree analysis

Six strains — A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, and A6 — of actinobacteria were extracted for genomic DNA using the GF1 bacterial DNA extraction kit (Vivantis). The 16S rRNA gene was amplified by using the primer pairs 27f and 1492r and sequenced following the protocol described previously (Kaewkla and Franco, 2013). The resultant sequences were compared to an online database using the EzTaxon-e server (Yoon et al., 2017) and aligned by using CLUSTAL X (Thompson et al., 1997). The phylogenetic trees were constructed by the maximum likelihood (ML) (Nei and Kumar, 2000) and neighbour-joining (Saitou and Nei, 1987) algorithms using the software package MEGA version 11 (Tamura et al., 2021) with Embleya scabrispora DSM 41855T as the outgroup. The Tamura-Nei method was applied to calculate the ML and NJ algorithms (Tamura and Nei, 1993). The topology of the tree was evaluated by performing a bootstrap analysis based on 1000 replications (Felsenstein, 1985).

Genome sequencing and assembly

The genomic DNA of strains A2, A3, and A5 was extracted utilizing the GF1 bacterial DNA extraction kit (Vivantis). PCR-free libraries were developed for whole genome sequencing in three bacteria. Samples were sequenced at the Omics facility at Chulalongkorn University on an Illumina MiSeq technology, producing 2 x 250 bp paired-end reads. The Unicycler software (version 0.5.1) was utilized for the de novo assembly of the reads (Wick et al., 2017).

Genome comparison study

For the digital DNA-DNA hybridization (dDDH) values, the Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC 2.1; BLAST+ method) used formula 2 (identities/HSP length) (Meier-Kolthoff et al., 2013) to automatically differentiate between strains A2, A3, and A5 and their closely related type strains of the genus Streptomyces in the database. The phylogenetic tree of the genomes of strains A2, A3, and A5 was constructed by the Type (Strain) Genome Server (TYGS) with its closely related type strains, with Embleya scabrispora DSM 41855T as the outgroup (Lefort et al., 2015; Meier-Kolthoff and Göker, 2019). The closely related type strains of each strain that had the highest dDDH value were evaluated for values of average nucleotide identity (ANI) using ANI-BLAST (ANIb) and ANI-MUMmer (ANIm) algorithms within the JSpeciesWS web (Richter et al., 2016).

Biosynthetic gene cluster analysis and in silico gene prediction

The genomes of strains A2, A3, and A5 were analyzed for biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) using the Secondary Metabolite Analysis Shell (antiSMASH) version 7.0 (Blin et al., 2023). The genomes of these three strains were annotated by RASTtk (Brettin et al., 2015) on the Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (BV-BRC) (Olson et al., 2023) (http://www.br-brv.org/). The pathways of strains A2, A3, and A5, as derived from the annotation data (PATRIC) (Wattam et al., 2017), were evaluated. Moreover, subclasses and subsystems related to stress response, programmed cell death and toxin-antitoxin systems, protein folding, resistance to antibiotics, and toxic compounds of each genome were analyzed.

Isolation of fungal pathogen and identification based on ITS sequence

A fungal pathogen causing root rot in eucalyptus seedlings grown on half-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium was isolated utilizing Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA), and the fungus was purified on PDA plates with a pH of 5.5. The pure fungal pathogen was preserved on a PDA slant and maintained by overlaying with sterile liquid paraffin for long-term storage at 4°C. The fungal pathogen was designated as strain RE1 and identified by ITS sequence. Strain RE1 was cultivated on PDA for 7 days at 25°C, and the mycelia were pulverized using a sterile mortar and pestle with liquid nitrogen. The genomic DNA of strain RE1 was isolated utilizing the GF1 Fungus DNA extraction kit (Vivantis). The internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sections of the rRNA operon and the 5.8S gene were amplified via polymerase chain reaction (PCR). PCR was performed with primers ITS 1 and ITS 4 (White et al., 1990), and the PCR methodology was previously detailed (Korabecna, 2007). The sequence of the fungal strain was compared with ITS rRNA sequences received from GenBank (National Center for Biotechnology Information, USA National Institutes of Health Bethesda, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST). The phylogenetic tree was generated using the Neighbor-Joining (NJ) algorithm (Saitou and Nei, 1987) within the MEGA version 11 software tool (Tamura et al., 2021), employing Penicillium crustosum FRR 1669 as the outgroup.

Hydroponic study in heat stress condition

Seeds of E. camaldulensis were obtained from the Forest Research and Development Office, the Royal Forest Department, Thailand. Seeds were soaked in reverse osmosis (RO) water overnight and surface sterilized using the modified protocols of Kampapongsa and Kaewkla (2016). Briefly, seeds were immersed in 70% ethanol for one minute and washed three times with sterilized RO water. After that, seeds were soaked in 6% sodium hypochlorite for 5 minutes and washed with sterilized RO water five times. Strains A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, and A6 were grown on half-strength potato dextrose agar (PDA) for seven days, and spore suspension was prepared in sterilized RO water. Spores were separated from mycelia by using sterilized cotton filled in a 10 ml syringe, and spores were counted by a hemocytometer to 108 spores/ml. Surface-sterilized Eucalyptus seeds were soaked in each spore suspension for 1 hr. RO water was used as a control. Seeds were germinated in a clear, sterilized plastic box (22x33x10 cm) lined with wetted Whatman no. 1 paper in the dark for 7 days at 27°C.

Half (½) strength Hoagland solution modified formula (Hoagland and Arnon, 1950) was prepared by autoclaving the RO water and autoclaved solution separately. The half-strength Hoagland solution was prepared under sterile conditions in a mixing bucket. Foam sheets (1 inch thick) were cut to fit in a white plastic container (26 cm wide, 34 cm long, and 12.5 cm high), fourteen holes were made per sheet, and they were sterilized using UV radiation. Plastic containers and sponges (1x1x1 inch) were sterilized by autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes.

The half-strength Hoagland solution prepared above was poured into the plastic container, and the 7-day-old eucalyptus seedlings prepared above were transferred onto a sponge sheet and into each hole of a foam sheet. The foam sheets with eucalyptus seedlings were moved in a plastic container with ½ Hoagland solution, and eucalyptus seedlings were nursed for 2 days at 28°C in the dark. After that, the seedlings were moved to an uncontrolled-temperature plant-growth room (Figure 1). In the first stage, the plants were not given light and oxygen for 3 days, after which oxygen was given to the eucalyptus seedlings using an air pump, and the lights were turned on for light/dark 12/12 hours (Panasonic FL 40SS. D/36, Daylight 2600lm 721m/w 6500k). The experiments were conducted between February and March 2024, and the temperature of the hydroponic container under the bulb where the plant was growing was measured at 9:00 a.m. and 15:00 p.m. every day. The atmospheric humidity was recorded at the same time as the temperature recording (Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 1. Hydroponic experiment set up to test the heat stress effect on eucalyptus seedling growth at 14 days.

There were 7 treatments:

Control = Seeds were soaked with water.

A1 = Seeds were soaked with actinobacteria strain A1.

A2 = Seeds were soaked with actinobacteria strain A2.

A3 = Seeds were soaked with actinobacteria strain A3.

A4 = Seeds were soaked with actinobacteria strain A4.

A5 = Seeds were soaked with actinobacteria strain A5.

A6 = Seeds were soaked with actinobacteria strain A6.

The experiment was done in eight containers per treatment and fourteen seedlings per container. A completely randomized design (CRD) was conducted for this experiment.

After 3 weeks of planting, 1/2 Hoagland solution was added in a volume of 1 liter to each container. Seedlings were measured for plant growth parameters and plant physiology at 41 days, after which, on the day, the plants were transferred to an uncontrolled-temperature plant-growth room.

Eucalyptus growth measurement

The following methods were used to measure plant growth parameters and physiology in order to study the influence of heat on eucalyptus seedlings treated with actinobacteria in hydroponic condition.

1) The chlorophyll a (Chl a), chlorophyll b (Chl b), and carotenoid (CAR) content analysis.

Fifteen seedlings of each treatment were randomly selected, and three plants were pooled as one sample, with five replicates of each treatment conducted. Fresh leaves (3rd and 4th leaves from the top) were weighed at 0.03 grams, then ground with liquid nitrogen using a sterilized mortar and pestle and suspended in 1.2 ml of 100% methanol. Then, leaf extraction was centrifuged at 10000 g for 7 mins, and the supernatant was collected. Samples were taken to measure absorbance at 662, 646, and 470 nm. For reading chlorophyll A (ca), B (cb), and total carotenoids (car), respectively, using a microplate reader (SPECTROstar Nano, BMG LABTECH). The chlorophyll content and total carotenoids were calculated using the following Equations 1–3, respectively (Meza et al., 2022). The chlorophyll a (Chl a), chlorophyll b (Chl b), and carotenoid (CAR) content analysis were reported as mg/g of fresh weight of leaves (mg/g FW), applied the method of Kerbab et al. (2021), and reported as µg/g FW.

A= absorbance value at specific wavelength, V = the final volume of the supernatant (1.2 ml);

W = fresh weight of the leaf (0.03 g).

2) Proline content analysis.

The same plant samples used for chlorophyll analysis were used for proline content measurement, for which five replicates of each treatment were conducted. Fresh leaves (5th and 6th leaves from the top) were weighed at 0.02 grams, ground by using a sterilized mortar and pestle, and dissolved in 3% (w/v) sulfosalicylic acid (1.3 ml) and centrifuged at 10000 rpm for 10 minutes. 400 μl of clear solution was pipetted, diluted in 600 μl of 3% (w/v) sulfosalicylic acid, and shaken well, and then 0.65% ninhydrin in a volume of 1 ml was added, mixed well, and boiled at 96°C for 30 min. The reaction was calorimetrically measured at 520 nm, and proline was calculated by comparison with a graph of the standard proline (L-proline) (Singh and Jha, 2016). Proline content was reported as micrograms per gram of fresh leaf weight (ug/g FW).

3) The number of plants remaining in each treatment was evaluated for plant growth parameters, including shoot length, root length, plant fresh weight, dry weight, average leaf area (3rd and 4th leaves), and number of lateral roots.

Seed germination and seed length vigor index tests in salinity condition

The first experiment

Eucalyptus (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) seeds were removed from seed debris, soaked with water overnight, and disinfected, and the actinobacterial spores were prepared according to the method of hydroponic study described above. The sterilized seeds were soaked with strains A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, and A6 and with sterile distilled water as a control for 60 mins, as described above. Eucalyptus seeds were placed on sterilized Whatman No. 1 filter papers filled with 1/2 strength Murashige and Skoog (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) solution in a Petri dish with sodium chloride concentrations of 0, 50, 100, 150, and 200 mM at pH 5.8. Fifteen seeds were placed in each Petri dish, with five replicates for each treatment. The Petri dishes were incubated in the dark in an incubator at 28°C for 2 days and then exposed to light from day 3 to day 8 (12/12 hr light/dark). On day 3 and day 8 of germination, seedlings with normal germination were recorded (the root of the seedling was at least 2 mm), and seedlings were measured for shoot and root length on day 8 (Supplementary Figure S1). The completely randomized design (CRD) was conducted for this experiment. The germination potential (GP), final germination percentage (FGP), and seedling length vigor index (SLVI) were calculated as the Equations 4–6, respectively.

m1; The total number of Seedlings that germinate normally in 3 days.

m2; The total number of Seedlings that germinate normally, in 8 days.

M; Total numbers of seeds in Petri dish.

SL; Seeding length (shoot and root length) (cm) at day 8.

The formula 4 was followed (Zou et al., 2023), while formula 5 and 6 were described by Kerbab et al. (2021).

The second experiment

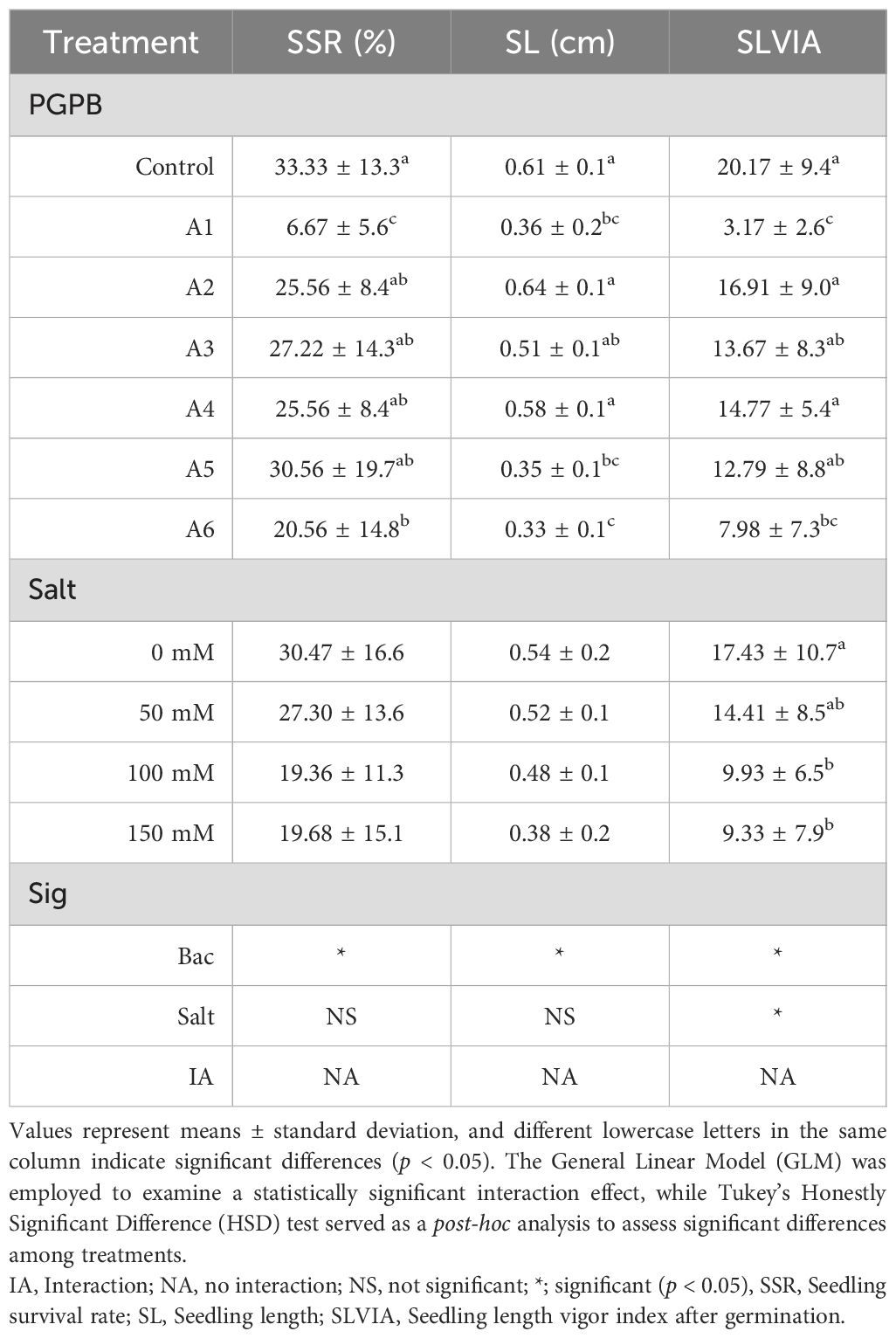

For the second experiment, germinated seedlings were primed with six actinobacteria to test the seed length vigor index (SLVI) under salinity conditions. As a result, the first experiment demonstrated that all six bacterial treatments resulted in lower germination potential (GP) and final germination percentage (FGP) compared to the control group. This study was similar to the first experiment, but eucalyptus seeds were surface sterilized and germinated in wetted paper with sterilized water for four days, and only seedlings with root lengths no more than 2 mm were used. As germination rates of eucalyptus seedlings were different, there were limited numbers of seedlings with eventual growth. Therefore, this study was carried out with three replicates, fifteen seedlings per Petri dish, and the concentrations of salt were 0, 50, 100, and 150 mM NaCl.

The roots of germinated seeds were immersed in spore suspensions of strains A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, and A6 prepared as the first experiment for 20 mins, and seedlings were soaked with sterile distilled water as a control experiment. Eucalyptus seedlings were placed on sterilized Whatman No. 1 filter papers filled with 1/2 strength Murashige and Skoog (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) solution in a Petri dish with the following sodium chloride concentrations: 0, 50, 100, and 150 at pH 5.8. Fifteen seeds were placed on each Petri dish, and three replicates were conducted of each treatment. The Petri dishes were incubated with light (12/12 hours light/dark) for 8 days. At day 8 of incubation, seedlings with root length more than 2 mm were recorded, and seedlings were measured for shoot and root length. The completely randomized design (CRD) was conducted for this experiment. The seedling survival rate (SSR) and seedling length vigor index after germination (SLVIA) were calculated as the Equations 7, 8, respectively:

m3; the total number of seedlings with root length more than 2 mm, in 8 days.

M; Total numbers of seedlings in Petri dish.

SL; Seeding length (shoot and root length) (cm) at day 8.

The formula 7 and 8 was modified from Zou et al. (2023) and Kerbab et al. (2021), respectively.

Plant growth promoting of six selected strains in planta

Eucalyptus (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) seeds were soaked in sterilized RO water overnight. The seeds were disinfected, and actinobacterial spores were prepared at a concentration of 108 spores/ml according to the hydroponic study method described above. The sterilized seeds were soaked with strains A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, and A6 for 1 hour, and seeds were soaked with sterile distilled water as a control. Eucalyptus seeds were placed on sterilized Whatman No. 1 filter paper filled with ½ strength Murashige and Skoog pH 5.8 solution (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) in a sterilized clear plastic box and incubated in a dark place at 28°C for 5 days.

Half strength Murashige and Skoog medium pH 5.8 solidified with 2.5% phytagel was prepared and poured in a volume of 50 ml each into tissue culture bottles (6 cm diameter x 11 cm high) and autoclaved at 121°C for 15 mins. After that, a sterilized 1 ml white tip was cut to 1/2 of the tip length, and the tips were inserted into a ½ MS bottle (three tips per bottle), after which the seedlings prepared above with eventual growth (root length 2 mm) were transferred into the hole of each tip by placing them over the surface of the ½ MS medium. The ½ MS bottles were placed in a temperature-controlled chamber at 28°C with cool day/light for 12/12 hours. At the end of 10 days, the number of seedlings growing normally was counted. Each treatment was done in fourteen replications (n=14). A completely randomized design (CRD) was conducted for this experiment. Although seeds were surface sterilized, seed-borne fungi still contaminated the seedlings. Seedlings without brown-colored leaves and rotting stems were recorded as survival seedlings. White puffy fungus causing seedling rot was isolated as a pure culture on PDA pH 5.5. The fungus was coded as strain RE1 and kept in a PDA slant at 4°C and prolonged by filling with liquid parafilm at 4 °C. The survival rate was calculated as follows.

Effects of strains A2, A3, and A5 on eucalyptus cuttings under drought and heat stress

Based on PGP results of strain A2, which increased growth of eucalyptus seedlings, and strain A3, which significantly increased chlorophyll b of seedlings compared to the control in hydroponic conditions. Strain A5, which significantly increased the final germination rate and seedling length at 200 mM NaCl compared to 0 mM NaCl. These three strains were selected for study of eucalyptus cuttings under drought and heat stress. The cuttings of wild-type Eucalyptus camaldulensis (P6) and the clone H42 ([CxG] x [CxP], C; E. camaldulensis, G; Eucalyptus grandis, P; Eucalyptus pellita) were propagated and provided by the Siam Forestry Co. LTD (SCG), Thailand. The age of cuttings was 90 days, and they were propagated in small white tubes (3.2 cm diameter, 11 cm height) with fine cocopeat (100%) as substrate. Between March and July, the temperature in Thailand can sometimes reach as high as 41°C due to extreme heat. A greenhouse without controlled temperature is not suitable for the experiment, as the temperature inside the greenhouse might be higher than 45°C. A balcony with a rooftop garden and strong sunlight exposure between 12 pm and 5 pm was used for the experiment.

The first experiment; drought stress

Spore suspensions of strains A2, A3, and A5 were prepared at 108 spores/ml as the previous experiment described above, but they were suspended in sterilized 0.3% xanthan gum. Cuttings of clone H42 were used in this study. The experiments were conducted in five treatments with 150 replicates for each treatment, and each cutting was treated with 3 ml of spore suspension or 0.3% xanthan gum as the control. Cuttings watered with plenty of tap water were also used as a positive control.

T1: Cuttings were treated with 0.3% xanthan gum and no water for 72 h DAI.

T2: Cuttings were treated with 0.3% xanthan gum and watered every day with plenty of tap water.

T3: Cuttings were treated with spore suspension of strain A2 and no water for 72 h DAI.

T4: Cuttings were treated with spore suspension of strain A2 and watered every day with plenty of tap water.

T5: Cuttings were treated with spore suspension of strain A3 and no water for 72 h DAI.

T6: Cuttings were treated with spore suspension of strain A3 and watered every day with plenty of tap water.

T7: Cuttings were treated with spore suspension of strain A5 and no water for 72 h DAI.

T8: Cuttings were treated with spore suspension of strain A5 and watered every day with plenty of tap water.

Cuttings were watered normally before the start of the experiment. Each treatment was poured with 3 ml of each spore suspension or 0.3% xanthan gum. After that, cuttings were not watered for 72 h DAI (day after inoculation). Temperatures at 1, 2, and 3 DAI were not high at 29.5, 32.4, and 33.8°C, respectively. Most cuttings showed sudden dying, but some cuttings still survived at 72 h DAI. All survivor cuttings were watered well at 72 h DAI for the next 6 days (4 to 9 DAI), and cuttings were recorded for wilt symptoms at 9 DAI. Between days 4 and 7 DAI, temperature was high at 36.5, 37.3, 38.8, and 38.7°C, and temperature was lower on days 8 and 9 at 32.5 and 31.6°C. At day 9 (DAI), most cuttings died out with dried stems and leaf symptoms (Supplementary Figure S2).

Cuttings were calculated for stress severity index (SSI), which modified the calculation of disease severity index according to the following formula as described by Huang et al. (2020). Cutting wilt was scored; score 0 = no symptom, score 1 = plant wilt symptom 1-25%, score 2 = plant wilt symptom 26-50%, score 3 = plant wilt symptom 51-75%, and score 4 = plant wilt symptom 76-100%.

(where the number 4 represents the highest score of cutting wilt).

Cuttings that suddenly died at 72 h DAI were also scored at 4. The experiment was conducted between 13 March and 29 March, 2025. The temperature and humidity of the plant station were recorded every day and shown in Supplementary Table S2.

The second experiment; limited water with heat stress

The result of drought stress in eucalyptus cuttings in the first experiment showed that treatments A2, A3, and A5 had a negative effect on the number of cuttings that survived, which showed fewer surviving cuttings than the control. Then, the spore suspensions of strains A2, A3, and A5 were variably studied at 106, 107, and 108 spores/ml on eucalyptus cuttings with the application of limited water instead of drought stress. The experiment was conducted from 13 March and 29 March, 2025. The experiment was conducted as the 1st experiment except for the cuttings of wild type P6, which were used instead of Clone H42. There were 10 treatments (T) with five replicates. T1: Cuttings were poured with 0.3% xanthan gum. T2–T10: cuttings were poured with spore suspension of strains A2, A3, and A5 at 106, 107, and 108 spores/ml. Cuttings were watered with plenty of water before starting the experiment. Each treatment was poured with each suspension for 3 ml. After 24 h (DAI), cuttings were poured with 3 ml of tap water and continually poured with 3 ml of tap water for 3 days (DAI). On days 4-8 (DAI), eucalyptus cuttings were poured with 5 ml of tap water in the afternoon and watered with plenty of tap water on days 9-10 (DAI). Between days 4 and 7 DAI with limited water at 5 ml., temperature was gradually increased to 36.5, 37.3, 38.8, and 38.7°C, respectively, and was lower at 32.5°C on days 8 and 9 DAI while increasing to 41.1°C on the last day of the experiment (10 DAI). The temperature and humidity of the plant station were recorded every day and shown in Supplementary Table S3. On day 11 (DAI), plants were scored and the stress severity index (SSI) was evaluated as described in the first experiment.

The third experiment; heat stress without drought

In the second experiment, we optimized the spore suspension of strains A2, A3, and A5 under limited water stress and heat stress. The result showed that strains A3 and A5 showed lower stress severity index (SSI) than the control at 107 and 108 spores/ml. Treatment with strain A3 showed the lowest SSI at 107 and 108 spores/ml, while the SSI of treatment A5 was higher at 108 spores/ml. Therefore, based on the result of the first experiment, as strain A3 showed the highest SSI at 108 spores/ml, the inoculum at 107 spores/ml was selected for this study. The experiment was conducted from 12 May to 9 June 2025, and it was carried out as described above. Eucalyptus cuttings of variety P6 were used in this experiment; each treatment was watered with a different suspension. There were 4 treatments with 60 replicates;

T1: cuttings were watered with 0.3% xanthan gum,

T2-T4: cuttings were watered with strains A2, A3, or A5 at 107 spores/ml.

Cuttings in each treatment were watered with 3 ml of each suspension, and after 24 h. (DAI), they were watered with 3 ml of tap water for 3 days (3 DAI). Days 4-9 (DAI), eucalyptus cuttings were poured with 5 ml of tap water in the afternoon, and cuttings were watered with plenty of tap water for 13 days between days 10 and 22 (DAI). Cuttings were arranged in CRD, and the temperature and humidity of the plant station were recorded every day (Supplementary Table S4). From day 20 to day 22 (DAI) of the experiment, the temperature was very high at 42.1, 40.3, and 39.7°C, respectively, and some cuttings suddenly died out with the wilt symptoms (Supplementary Figure S3). Cuttings were recorded for their symptoms, and the stress severity index (SSI) was scored at day 22 as described in the first experiment.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics version 29 (license of Mahasarakham University) was used to statistically analyze the plant growth parameters, seed germination, and seed length vigor index. The normality of the data was tested by the Shapiro-Wilk test. If the results showed that the data significantly deviated from a normal distribution, a non-parametric test with Kruskal-Wallis One-Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was adopted to determine a significant group. For two-way ANOVA, the Aligned Rank Transform test (ART) was used to align and rank data for each effect, allowing full factorial analyses with standard ANOVA procedures to be analyzed. In case the groups of data did not significantly deviate from a normal distribution, one-way multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) or two-way MANOVA applied a General Linear Model (GLM) to analyze multiple dependent variables simultaneously. In addition, in case the data did not significantly deviate from a normal distribution, a one-way ANOVA applied with the Tukey test was used for statistical analysis. Differences between means were considered significance at a p-value < 0.05.

Result and discussion

Identification of selected actinobacteria and 16S rRNA gene phylogenetic tree analysis

The result showed that six actinobacterial strains belonged to the genus Streptomyces (Table 1). The most abundant species of Streptomyces was Streptomyces rochei NRRL B-2410T (3 strains). Streptomyces strains ECL5.5 (A1), EKS3.2 (A3), and EKL5.16 (A4) shared 16S rRNA gene similarity with S. rochei NRRL B-2410T at 100, 100, and 100%, respectively. The position of these three strains was close to its type strain. The result of the ML tree showed that strains A3 and A4, which were isolated from the same plant sample (EK), were positioned on the same clade, while strain A1, which was isolated from sample EC, was positioned in the same clade with the type strain, S. rochei NRRL B-2410T (Figure 2). The NJ tree showed the different position of strain A3, which was positioned separately from strains A1, A4, and the type strain. Also, strains A1 and A4 were in the same clade with a high bootstrap support at 76 (Supplementary Figure S4).

Table 1. The three closest type strains of strains A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, and A6 based on 16S rRNA gene similarity.

Figure 2. Phylogenetic relationship, using the maximum likelihood tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences showing relationships between Streptomyces strains A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, and A6 and their closely related type strains of genus Streptomyces. Embleya scabrisporus DSM 41855T was used as an outgroup. There was a total of 759 positions in the final dataset. Bootstrap values based on 1000 replicates, and above 50 are shown.

Streptomyces strain ECR3.8 (A2) was closely related to Streptomyces albogriseolus NRRL B-1305T (99.8% similarity) and positioned in the same clade with this type strain on both ML and NJ trees. Strain ESR1.13 (A5) was closely related to Streptomyces ardesiacus NRRL B-1773T (100%) and positioned in the same clade with this type strain on both ML and NJ trees. Streptomyces strain ECR6.5 (A6) was closely related to Streptomyces thermoviolaceus subsp. apingens Z68095T (99.02% similarity) and formed the same clade with this type strain on the ML trees with high bootstrap support at 56 (Figure 2), while it formed a different clade with this type strain on the NJ tree (Supplementary Figure S4).

Genome based identification into a species level

The potential strains A2, A3, and A5 were selected to sequence their genomes. The GenBank accession numbers of genomes of strain A2, A3, and A5 are JBQXFC000000000, JBQXFB000000000, and JBQXFA000000000, respectively. These three genomes were identified to the species level based on dDDH, ANIb, and ANIm values. A study that compared the genome of Streptomyces strain ECR3.8 (A2) with its closest type strain discovered that this strain had the highest dDDH, ANIb, and ANIm values at 84.3, 97.9, and 98.3% for Streptomyces griseoincarnatus JCM 4381T. Streptomyces strain EKS3.2 (A3) had the highest dDDH, ANIb, and ANIm values with Streptomyces rochei NRRL B-2410T at 99.1, 98.4, and 98.3%. Streptomyces strain ESR1.13 (A5) showed the highest dDDH, ANIb, and ANIm values at 94.2, 98.9, and 99.3% with Streptomyces ardesiacus NBRC 15402T. According to Meier-Kolthoff et al. (2013), the species-level definition should have a dDDH value lower than the threshold of 70%, and ANIb and ANIm thresholds below 95-96% were used to delineate different species. The positions of strains A2, A3, and A5 on the TYGS phylogenomic tree showed that strains A3 and A5 were in the same clade with their closest type strains, except for strain A2, which was positioned in the different clade with its type strain. Three strains were in the same species clusters with their closest type strains (Figure 3). According to genome-based identification, Streptomyces strains A2, A3, and A5 belonged to the known species of Streptomyces griseoincarnatus JCM 4381T, Streptomyces rochei NRRL B-2410T, and Streptomyces ardesiacus NBRC 15402T, respectively.

Figure 3. Phylogenomic tree based on TYGS result showing the relationship between strains A2, A3, and A5, with related type strains in genus Streptomyces. Embleya scabrisporus DSM 41855T was used as an outgroup. The numbers above branches are GBDP pseudo-bootstrap support values > 60% from 100 replications, with average branch support of 97.5%. The tree was rooted at the midpoint (Lefort et al., 2015).

It was reported that plants treated with Streptomyces griseoincarnatus RB7AG exhibited elevated levels of proline and antioxidant enzymes, including superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD), and catalases (CAT), when subjected to salt stress, which facilitates plant survival under adverse conditions. Moreover, plants treated with this bacterium exhibited enhanced root and shoot length, indicating a systemic tolerance mechanism (Behera et al., 2023). The study of Wei et al. (2024) showed that Streptomyces rochei S32 significantly enhanced the growth of wheat and tomato by increasing shoot length, root length of wheat, and root length of tomato. These studies were consistent with the current study in which strains A2 and A3 belong to S. griseoincarnatus and S. rochei. Moreover, strains A2 and A3 promoted eucalyptus seedling growth in hydroponic conditions with heat stress.

Identification of fungal pathogens and ITS sequence phylogenetic tree analysis

Fusarium sp. RE1 was isolated from Eucalyptus seedlings grown on ½-strength MS agar. A colony of strain RE1 was white and fluffy on PDA agar, as shown in Supplementary Figure S5. The result of ITS sequence analysis showed that strain RE1 was closely related to Fusarium ipomoeae MZPP-8, Fusarium lacertarum NRRL 52753, Fusarium equiseti G328, Fusarium chlamydosporum P061, Fusarium sambucinum CBS:184.31, Fusarium verticillioides LCBPF09, and Fusarium incarnatum NRRL 32867 at 99.7% of ITS similarity. The closest neighbor of Fusarium sp. RE1 was F. incarnatum NRRL 32867, and the position of Fusarium sp. RE1 was separately further from other Fusarium strains on the ML tree (Supplementary Figure S6).

It was reported that Fusarium incarnatum caused root rot on Mongolian snake gourd (Yan et al., 2024) and tree peony (Gao et al., 2019). Moreover, F. incarnatum caused leaf spot and fruit rot on luffa in China (Chen et al., 2025). These studies were consistent with our finding that Fusarium strain RE1, which is close to F. incarnatum, caused root rot to Eucalyptus seedlings.

Eucalyptus growth in hydroponic condition with heat stress

The overall result showed that treatment with strain A2 was found to be effective in promoting eucalyptus growth in a hydroponic condition. The shoot length in treatment A2 was found to be the highest and significantly different from the control but not different from treatments A1, A3, and A5 (p < 0.05). Moreover, treatment A2 was found to have the highest number of lateral roots, but not significantly different from treatment A5. Both treatments showed significantly higher numbers of lateral roots than the control and other treatments (p < 0.05). In addition, the fresh weight of treatment A2 was found to be the highest, but there was no significant difference from the control, A1, A3, A4, and A5, but it was significantly different from treatment A6 (p < 0.05).

Treatments A3 and A5 were the second most effective strains. The dry weight of treatment A3 was found to be the highest and significantly different from most treatments, but not significantly different from treatment A2 (p < 0.05). Furthermore, treatment A3 was found to give the highest leaf areas and to be significantly different from the control, A4, and A6, but not significantly different from A1, A2, and A5. It was found that treatment A5 had the longest root length but was not significantly different from treatments A1, A2, A3, and A4 (p < 0.05). The root length of treatments A5, A1, and A2 was significantly different (p < 0.05) from the control and treatment A6 (Table 2 and Figure 4).

Table 2. Plant growth parameters of eucalyptus seedlings treated with six strains of actinobacteria in a hydroponic condition.

Figure 4. The effect of heat stress on eucalyptus seedlings grown in hydroponic conditions treated with six endophytic actinobacteria for 41 days. (A) control without bacteria (B) strain A1 (C) strain A2 (D) strain A3 (E) strain A4 (F) strain A5 (G) strain A6.

Seedlings treated with strain A6 were the lowest for all growth parameters. Treatment A6 had the lowest shoot length, fresh weight, leaf area, and number of lateral roots but was not significantly different from the control. Treatment A6 gave the lowest dry weight and was significantly different from all treatments (p < 0.05). Furthermore, treatment A6 had the shortest root length and was significantly different from nearly all treatments except for treatment A4 and control (p < 0.05).

According to the result of plant growth promotion in vitro from a previous study (Kaewkla et al., 2025), strains A1, A2, A4, and A6 produced ACC deaminase in vitro. IAA production of strains A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, and A6 was 25.30, 32.60, 25.00, 20.00, 31.59, and 42.21 ug/ml, respectively (Supplementary Table S5). Although strain A6 produced the highest IAA in vitro, this strain showed the least plant growth promotion in heat stress conditions. It was reported that bacterial IAA promotes root hair development, enhancing both the quantity and length of lateral and primary roots when present at appropriate concentrations. At elevated quantities, bacterial IAA may also impede primary root development (Normanly et al., 2013). Treatment A2, which was the most effective strain to promote plant growth, contained ACC deaminase, and this strain produced IAA. This finding indicates that the presence of ACC deaminase and IAA production may play a crucial role in the strain’s ability to enhance plant growth under stress conditions. This finding was consistent with the study by Rafi et al. (2022), which showed that under heat stress, adding PGPB with ACC deaminase activity enhanced plant activities and biomass compared to the respective control.

Through genome data mining of strain A2 to predict the subclass and subsystem of stress-related genes, we found that strain A2 had the highest number of gene counts for the chaperones GroEL, GroES, and thermosome; the heat shock dnaK gene cluster was extended; and protein chaperones were present at counts of 11, 12, and 17, respectively. In the genome of strain A3, gene counts for these subsystems were detected at 8, 7, and 4, while strain A5 had counts of 8, 8, and 13, respectively. It has been reported that GroEL and its cochaperonin GroES are classified as heat-shock proteins (Llorca et al., 1998). These proteins play a crucial role in facilitating the proper folding of other proteins under stress conditions, thereby maintaining cellular homeostasis. The variations in gene counts among strains A2, A3, and A5 indicate differing abilities to respond to heat shock, which may affect their overall stress tolerance and survival. This study was consistent with the study of Khan et al. (2020), which indicated that Bacillus cereus SA1 increased the heat stress response and increased heat shock protein (HSP) expression after heat stress for 5 days.

Chlorophyll a, b, and carotenoid contents

Treatment A3 contained the highest chlorophyll a, while treatment A1 had the highest chlorophyll b content. It was found that the amount of chlorophyll a was not significantly different from all treatments (p < 0.05), and treatment A3 showed the highest chlorophyll a, followed by treatments A2 and A5, which were higher than the control at 1.1, 1.07, and 1.01-fold change, respectively. The result indicated that the control had the lowest amount of chlorophyll b, while the treatments A1 and A3 had significantly higher content of chlorophyll b than the control (p < 0.05), but they were not significantly different from other treatments. Chlorophyll b content in treatments A1, A3, A2, A5, A6, and A4 was higher than the control by 2.9, 2.5, 2.1, 1.8, 1.75, and 1.67-fold changes, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3. Chlorophyll a (Chl a), Chlorophyll b (Chl b), carotenoid content (CAR) and proline of eucalyptus seedlings treated with six strains of actinobacteria in a hydroponic condition.

The carotenoid content in treatment A2 was the highest but not significantly different from the control and other treatments, except for treatment A1, which had the lowest carotenoids (p < 0.05). The result of carotenoid contents was not correlated with chlorophyll b, as treatment A1 comprised the highest amount of chlorophyll b. Correia et al. (2018) stated that chlorophyll a in Eucalyptus globulus decreased in drought and heat stress, while chlorophyll b was only reduced after the heat treatment. Khan et al. (2020) reported a significant reduction in chlorophyll a, b, and carotenoid under heat stress compared to normal conditions. Moreover, plants treated with Bacillus cereus SA1 significantly increased the contents of chlorophyll a, b, and carotenoid compared to the control without bacteria in heat stress conditions (p < 0.05). This study was consistent with PGPB, Bacillus cereus. According to the report by Chatterjee et al. (2020), the photosynthesis of Eucalyptus grandis decreases as the plant increases volatile emissions in heat stress conditions. In addition, inoculation of leaves with Brevibacterium linens RS16 increased heat resistance in E. grandis by increasing net carbon assimilation and decreasing foliar volatiles.

In this experiment, we did not have a controlled-temperature room to conduct the experiment in normal conditions, but we compared bacterial treatments with control without bacteria in the heat stress condition. This comparison allowed us to assess the effectiveness of the bacterial treatments in mitigating the adverse effects of heat stress on E. camaldulensis. The result of the plant physical growth of strains A2, A3, and A5 was consistent with the plant physiology of the photosynthesis parameter. Consequently, these strains could be valuable for optimizing hydroponic systems aimed at supporting plant health and growth in challenging environmental conditions.

The proline contents

The result showed that the amount of proline in treatment A1 was the highest, but there was no significant difference with control, A3, A4, and A6 (p < 0.05). The treatment A5 had the lowest proline content and was significantly different from the control, A1, A4, and A6, except for treatments A2 and A3 (Table 3) (p < 0.05). Therefore, nearly all bacterial treatments showed lower proline content than the control, except treatments A1 and A6, which had higher proline than the control (1.3- and 1.1-fold changes, respectively). This result was not correlated with the plant’s physical growth parameter and chlorophyll a and b contents, for which strains A2, A3, and A5 were the most effective strains to promote plant growth.

These findings suggest that while some bacterial treatments can influence proline levels, they may not directly enhance overall plant growth metrics. It was reported that proline had an effect on bacteria and plants in salt or drought stress conditions but not heat stress. Heat stress can lead to different physiological responses in plants, often resulting in a decrease in growth and yield.

It was reported that Azospirillum spp. accumulate proline, glycine-betaine, and trehalose to help plants to tolerate high osmotic pressure (Rodríguez-Salazar et al., 2009). In addition, Bacillus sp. produced proline and trehalose to support the growth of corn in drought and salt stress (Vardharajula et al., 2011). Furthermore, Bacillus spp. enhanced drought stress, which significantly reduced glutathione reductase (GR) activity and increased proline accumulation in Guinea grass (Moreno-Galván et al., 2020). This study was contrary to these reports in which strains A2, A3, and A5 promote plant growth in hydroponic conditions, but they comprise lower proline content than the control without actinobacteria.

Seed germination test (the first experiment)

Based on the six bacterialized seed-germination tests by germinating eucalyptus seeds on filter papers wetted with ½ MS solution containing 0, 50, 100, 150, and 200 mM of sodium chloride (w/v), germination potential (GP), final germination percentage (FGP), seedling length (SL), and seedling length vigor index (SLVI) are shown in Table 4. The overall result showed that the control showed the highest GP, FGP, and SLVI. Treatments A2 and A5 were not significantly different for GP compared to control, while treatments A1, A3, A4, and A6 were significantly lower than control (p < 0.05). However, GP for all bacterial treatments was not significantly different, except for treatment A6. Treatment A6 showed the lowest GP, FGP, SL, and SLVI and was significantly different compared to the control and the other five treatments (p < 0.05). For FGP, only treatments A1 and A6 were significantly lower than the control, and only treatment A6 was significantly different from the other five treatments (p < 0.05). The result of seedling length (SL) showed that treatment A4 had the highest SL, and the SL of treatments A1, A2, A3, and A5 were not significantly lower than the control. The SL of treatment A6, which had the lowest SL value, was significantly lower than that of all other treatments (p < 0.05). For SLVI, treatments A3 and A4 were not significantly lower than the control, while treatments A1, A2, A5, and A6 were significantly lower than the control (p < 0.05). This study found that strain A6 had the most negative impact on seed germination and seedling growth parameters, including plant growth in the hydroponic study discussed in the section “Eucalyptus growth in hydroponic condition with heat stress”. This strain might produce a bioherbicide or some bioactive compound that inhibits seed germination and seedling growth. According to Junior et al. (2025), Streptomyces sp. Caat 7–52 had phytotoxic effects against the weed Lemna minor L., for which it produced 3-hydroxybenzoic acid and albocycline as phytotoxins. Moreover, Streptomyces albidoflavus VT111I and Streptomyces cyaneus ZEA17I significantly inhibited the germination of lamb lettuce and tomato compared to the untreated control, respectively (Kunova et al., 2016).

Table 4. Effects of actinobacteria (PGPB) and salt (NaCl) on seed germination test of eucalyptus seedlings in the first experiment.

Table 4 displays the overall effect of salt on seed germination. GP and FGP at 50 mM NaCl were similar to those at 0 mM NaCl, and they were not significantly lower than those at 0 mM NaCl. SLVI and SL at 50 mM NaCl were the highest, with SL being significantly different compared to 0 mM NaCl, while SLVI was not significantly different at 0 mM NaCl (p < 0.05). This study was consistent with a report indicating that pretreatment with NaCl concentrations of 0.5, 1, and 2.5 mM significantly improved the germination percentage, vigor index, and radicle length of seedlings after seven days of germination under water stress (Cao et al., 2018). Moreover, salt concentration at 50 mM stimulated seed germination and enhanced a higher germination rate and longer radicles and hypocotyls than the control of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) (Hu et al., 2018).

Concentrations of salt at 100, 150, and 200 mM have affected GP, FGP, SL, and SLVI by reducing these seed germination parameters, and they were significantly different from salt at 0 and 50 mM NaCl. This study was consistent with the other work in which a 125 mM NaCl concentration caused the greatest reduction in the total number of germinated seeds (15%), germination rate (43.6%), root length (55.2%), root weight (39.3%), and seed vigor (68%), and it also increased the mean germination time of soybean by 71.9% (Monjezi et al., 2023). It was reported that all the salinity levels (40, 80, 120, and 160 mM of NaCl) in E. camaldulensis stimulated dry matter. Protein and chlorophyll concentrations of the plants fall at high levels of NaCl, except at 40 mM, at which this salt concentration stimulated photosynthesis, and E. camaldulensis could tolerate NaCl salt (Rawat and Banerjee, 1998). The first experiment, which involved bacterialized seeds and their germination, demonstrated the interaction between bacterial treatment and salt levels for GP, FGP, SL, and SLVI, as detailed below and in Table 5.

Table 5. The interaction (IA) between actinobacteria (PGPB) and salt (NaCl) on seed germination test of eucalyptus seedlings in the first experiment.

Germination potential of seedlings

GP of the control was the highest, but it was not significantly different from treatments A1, A2, A3, A4, and A5 except for A6 (p < 0.05) at 0 mM NaCl (Table 5). Treatment A6 showed the lowest GP, which was significantly different from all treatments at 0 mM NaCl. GP of all treatments except A6 at 50 mM NaCl were not significantly different from 0 mM NaCl. At 150 mM NaCl, the control and three bacterial treatments showed significantly lower GP than at 0 mM NaCl, except for treatments A1, A5, and A6 (p < 0.05). At 200 mM NaCl, the control and most bacterial treatments showed significantly lower GP than at 0 mM NaCl, except for treatments A5 and A6 (p < 0.05).

The final germination percentage of seedlings

The results showed that at 0 mM NaCl, the final germination percentage (FGP) of seedlings in the control experiment was the highest but was not significantly different from all treatments except A6. It was found that treatment A6 had the least FGP and was significantly different from all treatments at 0 mM NaCl. The result showed that when the salt concentration increased by 50 mM, treatments A3, A4, A5, and A6 had an increased FGP but were not significantly different from 0 mM NaCl. In the presence of an increased salt concentration of 100 mM NaCl, all treatments did not have a significantly decreased FGP when compared to 0 mM NaCl. At 150 mM NaCl, only the control and treatment A4 showed a significant decrease in FGP compared to 0 mM NaCl, while the other treatments did not show significant differences (p < 0.05). The result showed that at the highest salt concentration of 200 mM, the FGP in treatment A5 was the highest and was significantly different from all treatments. Moreover, the FGP of seedlings in A5 and A6 at 200 mM salt concentration was not significantly different from that in the 0 mM salt concentration (p < 0.05).

Seedling length

The results of measuring the length of eucalyptus seedlings at 0 mM NaCl showed that the control had the highest seedling length (SL), but it was not significantly different from treatments A1, A2, A3, and A4, except for A5 and A6 (p < 0.05). It was found that treatment A6 had the lowest seedling length and was significantly different from all treatments at 0 mM NaCl (p < 0.05). The result showed that when the salt concentration increased by 50 mM NaCl, all treatments had increased seedling length except treatment A3. At a concentration of 50 mM NaCl, the length of eucalyptus seedlings in all treatments did not significantly differ from 0 mM NaCl, except for treatment A6, which showed a significant increase in SL (p < 0.05).

At 100 mM NaCl, SL of all treatments was not significantly lower than at 0 mM NaCl (p < 0.05). The SL of control, treatments A1, A2, A3, and A4 was significantly reduced at 200 mM NaCl compared to 0 mM NaCl (p < 0.05). Although the SL of treatments A5 and A6 was significantly lower than other treatments at 0 mM NaCl, the treatments A5 and A6 showed no significant difference in SL at 150 mM and 200 mM compared to 0 mM NaCl.

The seedling length vigor index

The results showed that at 0 mM NaCl, the SLVI in the control was the highest; however, it was not significantly different from all treatments except for treatment A6, which had the lowest SLVI (p < 0.05). All six bacterial treatments except the control showed higher SLVI at 50 mM NaCl than at 0 mM NaCl, but these SLVI were not significantly different between these salt concentrations except for treatment A6. SLVI of treatment A6 at 50 mM NaCl was significantly higher than at 0 mM NaCl (p < 0.05). The control had a reduced SLVI at 50 mM NaCl but was not significantly different from 0 mM NaCl. SLVI at 100 mM of all treatments was not significantly different from 0 mM NaCl. SLVI of most treatments at 150 and 200 mM NaCl, including control, A2, A3, and A4, were significantly lower than at 0 mM NaCl, except for treatments A5 and A6 (p < 0.05). The result showed that SLVI of treatments A5 and A6 at 150 and 200 mM NaCl were not significantly lower than SLVI at 0 mM NaCl. According to a study by Yaghoubian et al. (2022), when the percentage of salt concentration increases, the seed vigor index (SVI) decreases. It was different from this study in that the salt-stimulated treatment A5 significantly increased the SLVI of the seedlings compared to the control at 200 mM NaCl.

Overall, this study showed that while salt concentration increased by 50 mM NaCl, most treatments except the control increased GP, FGP, and SLVI. This study showed that at 50 mM NaCl with control, treatments A1, A2, A4, A5, and A6 stimulated SL compared to 0 mM NaCl. Moreover, at 50 mM NaCl, SLVI of all bacterial treatments A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, and A6 increased by 1.1, 1.3, 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, and 4.8-fold changes compared to 0 mM NaCl, respectively. This study was consistent with the study of Akbaba and Özden (2023), which showed that Rhizobium sp. (strains K12, K13, and K40), Pseudomonas sp. (strain K116), and Enterobacter sp. (strain K188) promoted tomato plants under salt stress by increasing seed viability, hypocotyl length, root length, and seedling fresh weight, and enhanced germination.

Seedling length vigor index after seed germination (The second experiment)

According to the second experiment involving seedlings germinating before the application of bacteria and salt, the results differed from the first experiment, which showed no interaction between bacteria and salt. The seedling survival rate (SSR) was assessed based on the continuous development of germinated seeds over 8 days of incubation. Similar to the first experiment, the control treatment exhibited the highest SSR; however, it was not significantly different from treatments A2, A3, A4, and A5, while it was significantly different from treatments A1 and A6.

The seedling length (SL) in treatment A2 was the highest, but it was not significantly greater than that of the control, A3, and A4, with the exception of treatments A1, A5, and A6. The SL of these latter treatments was significantly lower than that of the control, A2, and A4. The seedling length vigor index after seed germination (SLVIA) for the control was the highest, but it was not significantly different from treatments A2, A3, A4, and A5, except for treatments A1 and A6 (Table 6).

Table 6. Effects of actinobacteria (PGPB) and salt (NaCl) on seed germination test of eucalyptus seedlings in the second experiment.

The SSR and SL of seedlings were not affected by the concentration of salt, as the SSR and SL of seedlings between 0, 50, 100, and 150 mM were not significantly different. However, SLVIA at control (0 mM NaCl) was not significantly higher than at 50 mM NaCl, but it was significantly higher than at 100 and 150 mM NaCl (p < 0.05). The result of the second experiment was different from the first experiment in that SRR (similar to FGP of the first experiment) and SL of seedlings of all salt concentrations were not significantly different. Moreover, unlike the first experiment, salt at 50 mM NaCl did not induce SL and SLVIA in seedlings in the second experiment (Table 6).

Based on the previous study, strains A2, and A5 can grow weakly at 11% NaCl (w/v), while strain A3 grew moderately at 11% NaCl (w/v) (Kaewkla et al., 2025). It was reported that Halomonas alkaliantarcticae M23 can tolerate up to 14% NaCl, produce auxin in vitro, and promote maize growth by increasing the K+/Na+ ratio, antioxidant levels, and ABA levels under salt stress conditions (Liu et al., 2025). Strain A6 produced the high IAA at 42.2 ug/ml. The seedling length in treatment A6 was significantly lower than that of the control and all other treatments at 0 mM NaCl, except for the treatment at 50 mM NaCl. This finding suggested that while strain A6 has the potential to produce high levels of IAA, the resulting concentration may be detrimental to plant growth under certain salt stress conditions. This finding was consistent with the study of Castellanos Suarez et al. (2014), which demonstrated Micrococcus luteus, an IAA-producing bacterium, functioned as a detrimental rhizobacterium for Arabidopsis thaliana, diminishing plant biomass and modifying root architecture in a dose-dependent way. A further investigation indicated that rhizobacterial IAA buildup was strongly associated with reduced root elongation in Beta vulgaris (sugar beet) after adding PGPB (Loper and Schroth, 1986).

Eucalyptus seedling growth on MS agar

The growth of eucalyptus seedlings that grew on ½ MS solidified with phytagel was measured 10 days after planting. 6% sodium hypochlorite used in seed surface sterilization could not destroy all seed-borne fungi. The result showed that the root parts of the eucalyptus seedlings were destroyed by the seed-borne fungi. The morphology of this fungus was fluffy white, causing the seedlings to rot. This fungus was identified as Fusarium based on the ITS sequence. The seedlings that have survived from the fungal infestation still had green leaves. The dead plants were the ones that had become bruised brown. It was found that the seedlings inoculated with strain A5 had the highest survival rate of 88.1%, which was much higher than that of the control and other treatments, with survival rates for the control (28.6%) and strains A1 (52.3%), A2 (30.9%), A3 (19%), A4 (9.5%), and A6 (38.1%), respectively, as shown in Supplementary Figure S7. This work was correlated with the study of Himaman et al. (2016), who isolated endophytic actinobacteria from red gum trees. The results indicated that Streptomyces strain EUSKR2S82 could strongly inhibit all tested fungi in both the dual culture assay and the detached leaf assay against Cylindrocladium sp., while also exhibiting plant growth-promoting traits. Moreover, Kaewkla (2009) isolated endophytic actinobacteria from Eucalyptus microcarpa and Eucalyptus camaldulensis and tested for their antifungal activity against plant pathogens Phytophthora palmivora and Fusarium oxysporum. The result showed that some strains showed good activity to inhibit these two fungal pathogens in vitro. In addition, it was reported that endophytic actinobacteria, Streptomyces sp. SLF27R, could inhibit Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. lactucae L74 (47.9%) (Kunova et al., 2016).

Effect of strains A2, A3, and A5 on eucalyptus cuttings in drought and heat stress

For the first experiment, the clone H42 was used, as this clone tolerates heat and drought stress less than wild type P6. The result showed that all bacterial treatments harm cuttings in drought stress conditions, in which they have a higher stress severity index (SSI) than the control (83.3%). Strain A3 had the highest SSI at 97.3%, while strains A2 and A5 have similar SSI with the control at 88.7% and 88.7%, respectively. In this experiment, plants were induced to biotic stress with actinobacteria inoculum and abiotic stress as drought stress at the same time. Therefore, plants with actinobacteria inoculation are more affected than those with only drought stress without bacterial inoculum. This indicates that the presence of actinobacteria exacerbates the plants’ response to drought conditions, leading to increased stress levels. Future studies could explore the mechanisms behind this interaction to better understand how to mitigate stress in affected plants.

The study of Rahnama et al. (2023) showed that water stress greatly reduced the above-ground fresh weight of the plant and the nitrogen (N) and potassium (P) content of Secale montanum. PGPB; Bacillus cereus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Azospirillum lipoferm, and Azotobacter chroococcum had positive effects on the fresh and dry weights, seedling vigor index, quality index, and nitrogen and potassium content of plants under water stress. Furthermore, Streptomyces strains improved leaf relative water content (RWC), proline levels, malondialdehyde (MDA), H2O2, total sugar content, and ascorbate peroxidase activity while reducing catalase and glutathione peroxidase activity under drought stress in tomatoes (Abbasi et al., 2020). Under water limitation, Bacillus strain 3.13 and Micrococcus strain 4.43 enhanced shoot and root weight, height, root diameter, root length, root volume, root area, and root surface of Jerusalem artichoke. In addition, Micrococcus strain 4.43 increased leaf area and chlorophyll content (Namwongsa et al., 2019).

The second experiment used the wild type of E. camaldulensis, variety P6, to test various bacterial inocula on cuttings while applying limited water and heat stress (less than 40°C). The control without bacteria showed SSI at 51.7%. Unlike the first experiment, strain A3 showed no negative effects on cuttings under heat stress without drought at 107 and 108 spores/ml. Treatment with strain A3 had SSI at 106, 107, and 108 spores/ml at 80%, 20%, and 55%, respectively (Table 7). The result showed that strain A2 showed SSI higher than the control for two levels of spore concentrations. However, there was less SSI in strain A2, while spore inoculum increased at 60%, 55%, and 50% for 106, 107, and 108 spores/ml, respectively. Moreover, strain A5 showed less SSI than the control, but the SSI of this treatment increased at 108 spores/ml. In treatment A5, the SSI were 45%, 35%, and 50% for spore concentrations of 106, 107, and 108 spores/ml, respectively. Then, spore inoculum at 107 spores/ml was selected to test for the third experiment, which applied only heat stress higher than 40°C to cuttings. It was consistent with the study of Ngalimat et al. (2022), which showed that the spore inoculum of Streptomyces influenced plant growth. The spore inoculum at 1 × 107 spores/ml was suitable for Streptomyces corchorusii TKR8 and Streptomyces corchorusii JAS2, while 1 × 106 spores/ml was suitable for Streptomyces misionensis TBS5 to provide the highest vigor index of inoculated rice seedlings.

Table 7. Stress severity index of eucalyptus cuttings treated with control, strains A2, A3, and A5 in drought and heat stress.

The result of the third experiment was that cuttings were continuously naturally exposed to a heat wave for three days at 42.1, 40.3, and 39.7°C (between 3 pm and 5 pm). The controls without bacteria showed SSI at 50%. Treatments A2 and A5 exhibited SSI of 52.9% and 50.8%, respectively, which were slightly higher than the SSI of the control. In contrast, treatment A3 had the highest SSI at 62.5%, which was the least effective treatment.

The hydroponic experiment demonstrated that strain A3 induced higher levels of chlorophyll b in seedlings compared to control under heat stress conditions. Moreover, strain A3 gave the highest chlorophyll a, higher than the control (1.7-fold), and gave a significantly higher plant dry weight than the control (p < 0.05). This study demonstrated that strain A3 had a significantly more negative impact on cuttings under drought stress compared to heat stress in wet conditions, such as those found in hydroponics. Moreover, the hydroponic solution contained a high concentration of minerals that are related to photosynthesis enzymes. Genome analysis of strain A3 showed that its genomes comprised genes encoding zincophore, coelibactin, and siderophore, coelichelin, which support its ability to chelate zinc and iron. It was reported that endophytic actinobacteria, Streptomyces sp. GMKU 3100, produced siderophore, and it could enhance root and shoot biomass and lengths of rice and mungbean plants (Rungin et al., 2012).

However, cuttings in treatment A3 suddenly experienced shock and died in large numbers, while those exposed to drought stress (72 h DAI) were compared to the control and other treatments in the first experiment. On the other hand, strain A3 supported the plant under limited water conditions and heat stress below 40°C. Strain A3 may produce signal molecules that interact with cuttings to induce programmed cell death in prolonged drought stress. Genomes of strain A3 comprised genes relating to programmed cell death and YoeB-YefM toxin-antitoxin, which was not detected in genomes of strains A2 and A5. It was reported that the expression of the yoeB chromosomal toxin gene from Streptococcus pneumoniae induces cell death in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana (Bakar et al., 2015).

This work is the first report indicating that PGPB acts as a plant growth regulator with a negative impact on plants under abiotic stress conditions, while it promotes plant growth in certain stress circumstances. Based on the result of this experiment and genome data mining, strain A3 is not suitable to use as a plant growth promoter in the future, as it will have a very negative impact on plants, especially in drought stress conditions.

Genome insight into strains A2, A3, and A5

Genome features

Genome size of strains A2, A3, and A5 was 7.55, 8.35, and 7.86 million base pairs (Mbp), respectively, and their G+C contents were 72.4%, 72.5% and 72.6%, respectively. Numbers of proteins, tRNA, of strains A2, A3, and A5 are shown in Supplementary Table S6.

Biosynthetic gene clusters

All Streptomyces strains, A2, A3, and A5, have BGCs for geosmin (100% for all) and hopene (53% for A2 and 100% for A3 and A5), which are common substances in many Streptomyces strains (Supplementary Table S7). Additionally, the genomes of these strains include spore pigment (83% for A2 and 66% for A3 and A5), informatipeptin (42% for all), and albaflavenone (100% for all). Albaflavenone is known to be a tricyclic sesquiterpene antibiotic that inhibit bacteria and is produced by many Streptomyces strains (Moody et al., 2012). Only strain A2 was detected with a BGC of carotenoid (54%), which is related to the result of plant growth promotion in hydroponic conditions with heat stress. Strain A2 produced the highest carotenoid, significantly higher than the control. It was reported that bacteria play a crucial role in enhancing plant health by generating carotenoids, which help absorb light and shield plant cells from harmful oxidative stress (Borowitzka, 2010).

There were many BGCs relating to plant growth promotion and stress response detected in the genomes of strains A2, A3, and A5. BGCs of ectoine were detected in genomes of strains A2, A3, and A5 (100% for all). Ectoine is an osmoregulation compound that helps bacteria and plants to tolerate drought, heat, and salt stress conditions (Van Thuoc et al., 2019). It was consistent with this study that strains A2 and A3 promoted eucalyptus seedling growth in hydroponic conditions with heat stress, and strain A5 promoted seedling growth in salt stress conditions. Strains A2 and A5 have BGCs of the siderophores desferrioxamin B and E (100%, 100%), while strains A3 and A5 comprise BGC of a tripeptide siderophore synthesized by the non-ribosomal peptide synthetases, coelichelin (Challis and Ravel, 2000). In addition, strains A3 and A5 comprised BGCs of a putative non-ribosomally synthesized peptide with predicted zincophore activity: coelibactin (100, 100%) (Kallifidas et al., 2010).

It was consistent with this study that hydroponic solution comprised iron and zinc, in which strain A3 could chelate these irons to promote plant growth. The treatment of strain A3 showed the highest plant dry weight and leaf area, significantly higher than the control. Moreover, strain A3 comprised the highest chlorophyll a, and chlorophyll b content was significantly higher than the control. Zinc, an essential element for crop growth and development, serves as a cofactor for many enzymes that participate in critical physiological and biochemical processes such as photosynthesis and hormone synthesis (Nazir et al., 2021).

Moreover, the genomes of three strains comprised BGC of bioactive compounds that possessed antimicrobial and anticancer compounds. Genomes of strains A3 and A5 comprised BGC of indole compounds: 5-dimethylallylindole-3-acetonitrile (100%). Only the genome of strain A3 was detected with the BGC of indole compound 7-prenylisatin, which showed antimicrobial activity against Bacillus subtilis (Wu et al., 2015). BGC of isorenieratene was detected in the genomes of strains A3 and A5 (83% and 62%). It was reported that isorenieratene has an antioxidant activity to inhibit light/ultraviolet damage (Chen et al., 2019). Moreover, the genomes of strains A3 and A5 comprise BGC of flaviolin (100%, 100%) and SapB (100%, 100%). Flaviolin, also known as 1,3,6,8-tetrahydroxynaphthalene (T4HN), is a type of compound that supports fungi to produce melanin. SapB is a type of wool thiopeptide, and research has shown that wool thiopeptides from actinomycetes are very effective at inhibiting bacteria, as well as having anti-cancer, anti-virus, and other beneficial effects.

In addition, the genomes of strains A2 and A3 contain BGCs of polyphenolic compounds: alkylresorcinols (Ars) (100%, 100%). It was reported that Ars are potential quorum-sensing molecules involving gut microbiome and host interaction (Zabolotneva et al., 2023). From the study of hydroponic conditions, strains A2 and A3 showed good supporting growth of eucalyptus, in which they have a gene encoding Ars to interact with the host plant.