- 1Department of Agricultural Science, Mwalimu Nyerere University of Agriculture and Technology, Butiama, Tanzania

- 2Department of Crop Science and Horticulture, Sokoine University of Agriculture, Morogoro, Tanzania

- 3Institute of Pest Management, Sokoine University of Agriculture, Morogoro, Tanzania

Bean aphid is a significant insect pest that limits achievement of maximum yields and quality of beans. Overreliance on synthetic insecticides has led to the development of insecticide resistance, negatively impacting both human and environmental health. Use of entomopathogenic fungi is considered safer and environmentally friendly for managing bean aphids. A study was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of three different conidial concentrations 1× 107, 1 × 108, and 1 × 109 spores/ml from two fungal isolates, Fusarium equiseti (JD02) and Cladosporium cladosporioides (JD07) along with distilled water containing 0.1% Triton x-100 and Imidacloprid as controls, against the Aphis fabae. A completely randomized factorial experiment was used in which petri dishes containing live aphids were sprayed with suspensions of the fungi concentrations. Mortality rate was recorded at the 3rd, 5th, and 7th days after inoculation. At the 7th day, the results showed that Imidacloprid treatment caused high mortality rates of 100%. A concentration of 1×109 spores/ml resulted in mortalities of 93.65% and 72.9%, followed by 1×108 spores/ml, which resulted in mortalities of 78.57% and 57.38% for JD-02 and JD-07, respectively. Meanwhile, a concentration of 1×107spores/ml led to lower mortalities of 62.02% and 40.24% for JD-02 and JD-07, respectively. Additionally, the LT50 and LT90 of F.equiseti and C.cladosporioides differed significantly at P<0.05; however, among the tested concentrations, 1×109 spores/ml of both F.equiseti and C.cladosporioides took 5.09 and 5.23 days to kill 50%, and 6.92 and 7.52 days to kill 90% of bean aphids, respectively. The isolate F.equiseti caused higher mortality compared to C.cladosporioides; additionally, a concentration of 1×109 spores/ml of F.equiseti resulted in higher mortality > 90% at the seventh day. Therefore, Fusarium equiseti demonstrated significant potential for controlling bean aphids.

1 Introduction

The black bean aphid, Aphis fabae Scopoli (Hemiptera: Aphididae), is a complex species that prefers the new growing parts of plants to suck the sap and to deposit nymphs (Esmaeili-Vardanjani et al., 2013; Stoddard et al., 2010). It’s estimated that bean aphids are capable of causing yield losses of 70% in various crops, especially vegetables (Nordey et al., 2017). The losses are due either to direct damage by feeding of the plant sap from the plant vascular tissue or to indirect transmission of plant pathogenic virus (Boni et al., 2021). Additionally, bean aphids contaminate the leaves through honeydew deposits on the surface of the plant foliage, thus favoring the growth of the sooty molds, which hampers the photosynthetic efficiency of the plants (Wamonje et al., 2020).

Management measures for bean aphids, such as cultural, mechanical, and chemical control, have been implemented to reduce their population; however, the use of synthetic insecticides, especially pyrethroids, neonicotinoids, organophosphates and carbamates, outweighs other control measures (Zanic et al., 2013). This is because they are easy to apply (labor-saving) and accessible compared to other methods. Consequently, indiscriminate and extensive use of synthetic insecticides in the management of bean aphids has resulted in environmental pollution (bio-magnification), build-up of insect resistance, threats to natural beneficial organisms (pollinators, parasitoids, prey and predators) (Bass et al., 2015; Sharma et al., 2019).

Therefore, the negative effects of synthetic chemicals have prompted agricultural producers and scientists to seek environmentally safe and acceptable control measures against bean aphids while safeguarding the ecosystem and human health. One promising alternative avenue is the use of microbes, especially entomopathogenic fungi (EPF).

Entomopathogenic fungi (EPF) have been reported to be effective against many species of insect pests in agricultural settings presenting an opportunity to be used in the management of bean aphids (Maina et al., 2018; Mweke et al., 2018). The mode of action of entomopathogenic fungi is through enzymatic degradation of insect bodies, release of toxic proteins and bioactive secondary metabolites upon penetration, which results in paralysis, disrupting physiological processes like the immune system and nerve conduction that leads to abnormal behaviors, dehydration and eventually death (Dauda and Maina, 2018; Litwin et al., 2020). Several species of entomopathogenic fungi (Beauveria spp, Metarhizium spp and Isaria spp) are well known and currently commercially marketed as bioinsecticides to control bean aphids (McGuire and Northfield, 2020; Zimmermann, 2008). However their utilization has been increasing in the market of the United States, Europe and Asia for several decades (Dauda and Maina, 2018). Their use in East Africa, especially in Tanzania, is limited due to a lack of suppliers and information about suitability for the local climate (Boni et al., 2021). Consequently, this situation necessitates testing of locally available fungi species which could be potentially entomopathogenic to bean aphids. This strategy can help to support efforts to identify more virulent species that can be used in the management of bean aphids. This study was therefore set to assess effectiveness of Fusarium equiseti and Cladosporium cladosporioides species naturally sourced from the local environment against Aphis fabae.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Description of the study area

This study was conducted between April 2025 to July 2025 in the Mycology laboratory and screen houses of the Department of Crop Science and Horticulture (DCSH) located at Sokoine University of Agriculture (SUA), Tanzania (6.8520°S and 37.6576°E). Morogoro municipality is located at the foothills of the Uluguru Mountains. It is characterized by a tropical-sub humid climate with bimodal rainfall ranging from 800 to 1,200mm, average annual temperature ranging from 18˚C to 30˚C, with cooler conditions during the rainy season and warmer conditions during the dry season (Kacholi, 2020).

2.2 Establishment of common bean and rearing of bean aphids

Common Beans, Phaseolus vulgaris L (one plant per pot) (Fabaceae) were grown to feed Aphis fabae. The plants were established in 20 plastic pots of 1 L, then placed on top of tables in the screen house. Standard management practices were applied to the common bean plant. Bean aphids were collected from unsprayed bean plants within and around the SUA crop museum located in Morogoro, Tanzania (6.8520°S and 37.6576°E). Bean aphids were collected by plucking the aphid-infested leaves from a bean plant and placed inside a plastic container, then transferred to the mycology lab and identified under a light microscope by using polyphagous aphid keys (Blackman and Eastop, 2000). Identified bean aphids were inoculated onto insect-free bean plant leaves in clip cages (2.5–4 cm) for multiplication. Plants were watered twice a day, depending on the moisture content of the soil detected by the feel method. Temperature and relative humidity (RH) were 26 ± 3°C, 65 ± 5%, respectively and a photoperiod of 12:12h (L: D).

2.3 Isolation, identification and preparation of fungal isolates

The two fungal isolates were isolated from cadavers of bean aphids and then molecularly identified as F.equiseti and C.cladosporiodes through the use of ITS gene region (ITS1 (F5’TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3 ′) and ITS4 (5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′) (Hoggard et al., 2018). After identification the purified fungal species were stored in a slant at the mycology lab of the Department of Crop Science and Horticulture, Morogoro, Tanzania. Before performing the pathogenicity and bioassay test the fungal species were cultured on PDA for 10 days at 28 ± 2 0C and 75% RH until mycelia grew in full; the obtained pure cultures were used for bioassay experiments.

2.4 Inoculum of isolates of entomopathogenic fungi

One isolate of F.equiseti and C.cladosporioides were initially screened for their pathogenicity against the 10 apterous adults of bean aphids using one concentration of 1×108 spores/mL. The spore suspension was prepared from 12-day-old cultures grown on PDA plates at 24 ± 2°C. The colony surface was scraped with a sterile inoculating needle and harvested into 20 mL of sterile distilled water as per Zekeya et al. (2019). The suspensions were filtered using a double-layer muslin cloth and transferred to a conical flask containing distilled water with a drop of Tween-80 to keep the conidia dispersed uniformly, and then shaken thoroughly for 10 min (Boni et al., 2021). The conidia spores were counted in the suspension with the aid of a light microscope and adjusted with a hemocytometer (Swastik Scientific Company, India). A hemocytometer is essentially a microscope slide bearing a small well of known depth, the base of which is marked with squares of known dimensions. During use, the well is covered with a special coverslip (usually 0.4 mm thick). The other three working concentrations (1 ×107, 1×108, and 1×109 spores/mL) were prepared by diluting the stock inoculum with sterile distilled water as per Zekeya et al. (2019).

2.5 Experimental design

The bioassay factorial experiment was set under a completely randomized design with the two factors (Fungal isolate and conidia concentration) by using F.equiseti (JD 2) and C. cladosporoides (JD 7) set at 1 ×107, 1×108, and 1×109 spores/ml as serial conidial concentrations. Bean leaves free of aphids and disease symptoms were collected and rinsed with distilled water, then placed in a Petri dish (120×20 mm) on top of sterile filter paper for bean aphid feeding. These leaves were changed daily up to seven days. Then, 50 adult bean aphids were transferred to each bean leaf using a fine brush. Each Petri dish containing 50 adult bean aphids was sprayed with an aliquot of 1 ml of a suspension of conidia of the entomopathogenic fungus with concentrations of 1 ×107, 1 ×108 and 1 × 109 conidia ml−1. Each treatment was replicated three times. The controls were sprayed with distilled water with 0.1% Tween-80. All the treated bean aphids were kept at lab temperature (26 ± 2°C).

2.6 Data collection and confirmation the cause of aphids’ mortality

Cumulative aphid mortality was recorded daily for up to seven days after application of the three different concentrated conidial suspensions of each fungus, besides negative and positive controls. The dead aphids were surface sterilized with 1% Sodium hypochlorite solution, and washed with distilled water before being placed in Petri dishes (60x10 mm) with lined and wet blotter paper for facilitating mycelial growth. The petri dishes were sealed and incubated at 28 ± 2°C and 75% RH as per Thaochan and Sausa-Ard (2017). On the fifth day of incubation, cadavers were checked for mycosis signs with a dissecting microscope (Leica Zoom 2000 No Z45V). Emerging mycelia were harvested using a sterile inoculating needle and transplanted onto plates made up of PDA for confirmation procedures. After 7 days, the mycelia were examined under the microscope. If a dead aphid did not show fungal outgrowths of similar characteristics to those of the one applied as the treatment, its death was considered as caused by another factor, or factors, and was therefore discarded.

2.7 Statistical data analysis

Cumulative mortality rates data were corrected on the 3rd 5th and 7th day after inoculation by using Abbott’s formula (Abbott, 1925). Percentage Cumulative mortality data from bioassay post-inoculation were subjected to analysis of variance(ANOVA) by using R-studio version (2025.05.1 + 513 exe) under Car package. The residuals from the analysis of variance table were tested for normality by using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Serial time-mortality data from bioassay were analyzed by Probit analysis using R-studio to calculate Median lethal time 50% (LT50) and 90% (LT90%). Mean separation was performed by a Tukey post-hoc test at a significance level (P< 0.05).

3 Results

3.1 Efficacy of Fusarium equiseti and Cladosporium cladosporioides fungi against the black bean aphid

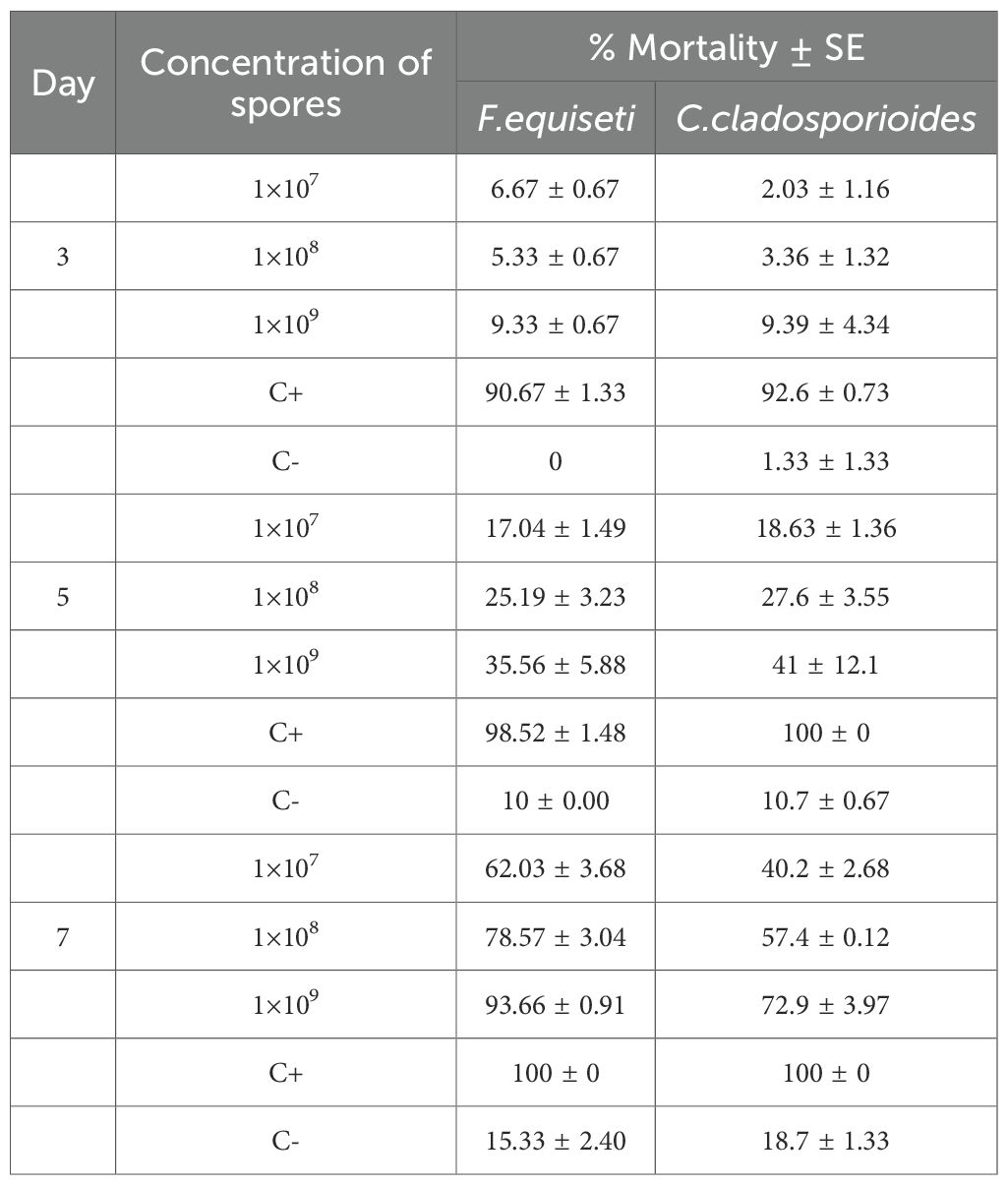

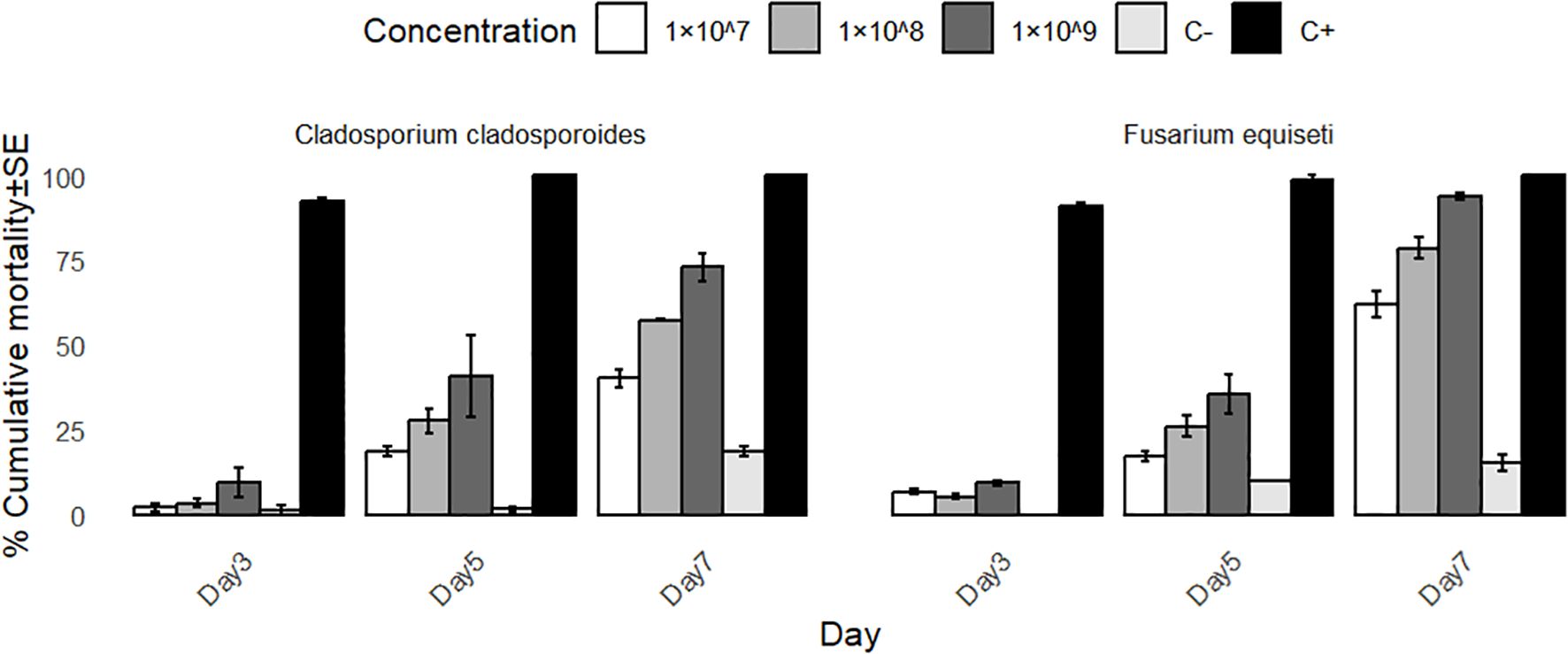

Findings have shown that the three spore concentrations of F. equiseti and C. cladosporioides were suppressive to bean aphids (Table 1 and Figure 1). Mortalities of bean aphids gradually increased with the increase in concentration of spores and time of exposure.

Table 1. Percentage mean mortality of bean aphids (Aphis fabae) under varying concentrations of spores of Fusarium equiseti and Cladosporium cladosporioides, along with positive and negative control at 26± 2°C.

Figure 1. Mean aphid mortality % caused by different conidial concentration of entomopathogenic fungi at 3th, 5th and 7th days.

The pathogenic activity of fungi began showing effects after 2 days post-infection, and the bean aphids were observed not moving from one place to another Figure 2.

The colony characteristics and macroconidia from the cadavers revealed similarity to the ones that were used during the infecting process Figure 2.

Figure 2. Typical mycosis observed externally on the bean aphid cadaver due to fungal infection after the cadaver was incubated for 5 days at 28 ± 2°C.

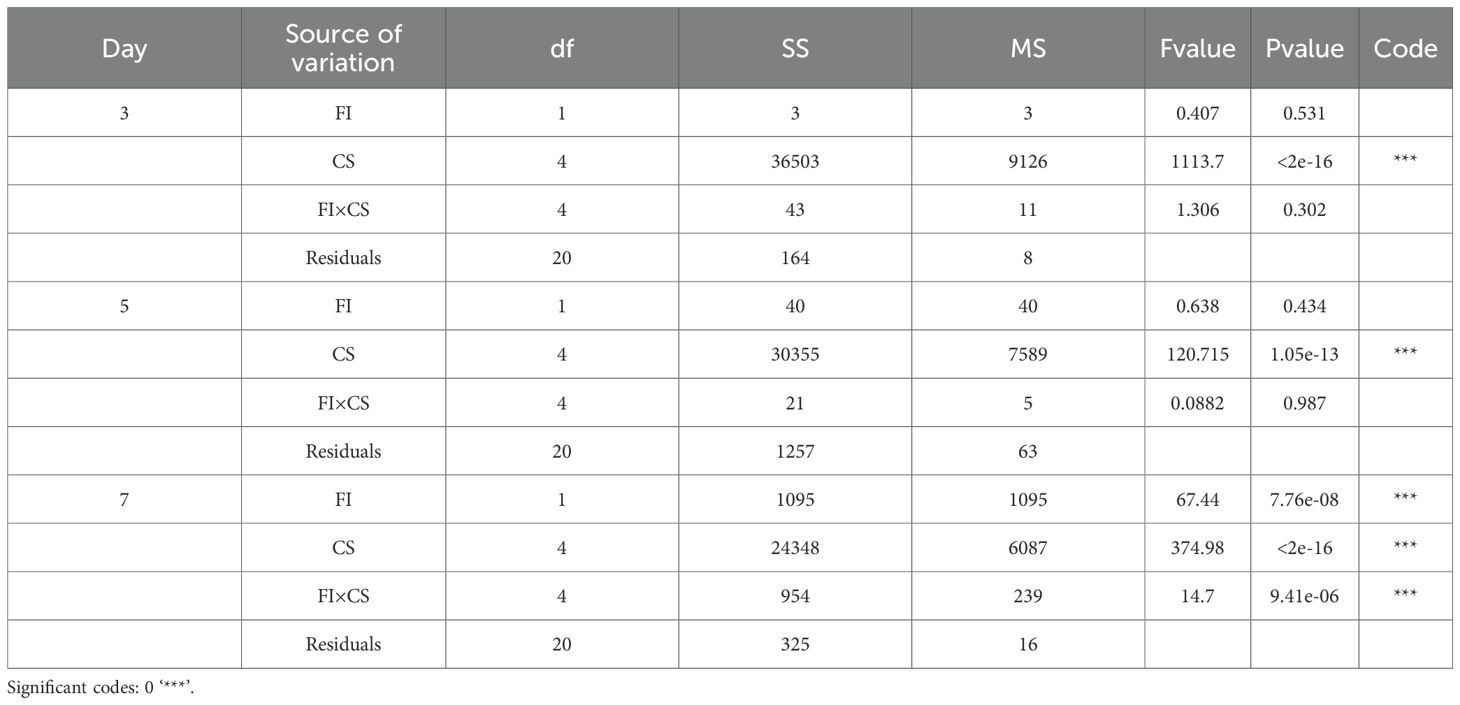

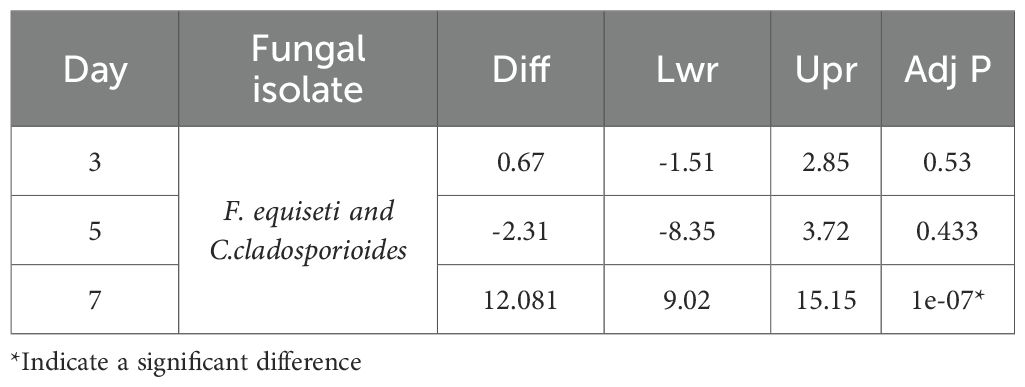

Regardless of the isolates used, the average cumulative mortality (%) increased with an increase in concentrations. Bioassay results showed that the two fungi species, F. equiseti and C. cladosporioides, do not differ significantly at P = 0.531 and 0.434 at day 3 and day 5, respectively (Table 2). However, the tested concentration of 1×107, 1×108, 1×109 spores/ml differ significantly in causing mortality of bean aphids (P<0.00001) across all days of post infection (Table 2). The concentration of 1×109 spores/ml for both Cladosporium cladosporioides and Fusarium equiseti resulted in high mortalities of 72.09% and 93.86%, respectively, followed by 1×108 spoes/ml with mortalities of 57.38% and 78.57% spores/ml. However, 1×107 spores/ml had lower mortalities of 62.02% and 40.24%, respectively (Table 1).

Table 2. A two-way ANOVA revealed a significant difference between the fungal isolate and concentration of spores and their interaction on the mortalities of bean aphids, with the P< 0.05 at 7 days’ post-infection.

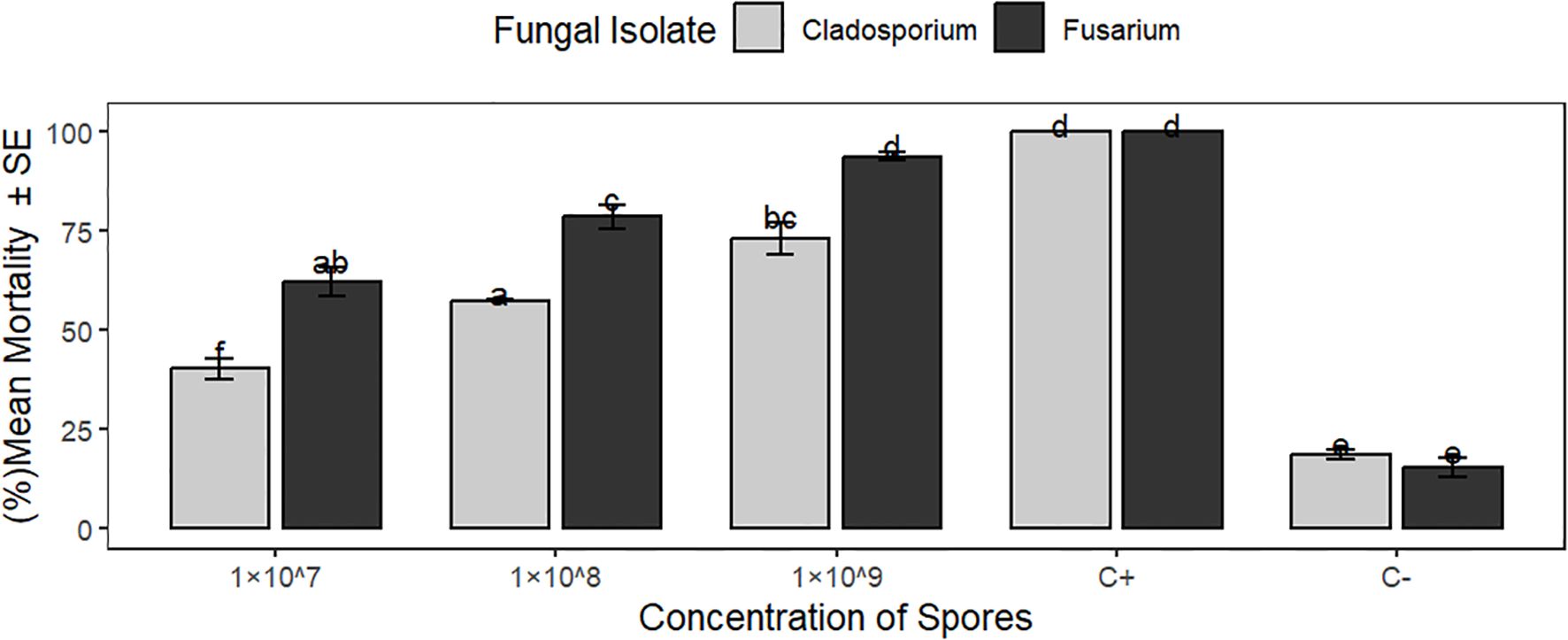

3.2 Pathogenicity comparison of the isolates

At 7 days post-infection, statistical analysis revealed a highly significant difference (P<0.0001) in mortality of bean aphids exposed to F. equiseti (JD2) and C.cladosporioides (JD7), at varying spore concentrations (1×107,1×108,1×109 spores/ml). Notably, F.equiseti consistently induced higher mortality compared to C.cladosporioides Table 3 and Figure 3.

Figure 3. Bars represent the mean mortality (%) of Aphis fabae caused by Fusarium equiseti and Cladosporium cladosporioides at different concentrations. Means followed by similar letters are not significantly different by Tukey’s HSD multiple range test at p<0.05.

Table 3. The Tukey multiple comparison of means mortalities for grouped fungal isolates at 95% family- pairwise confidence level.

3.3 Median lethal time (LT50) and (LT90) of Fusarium equiseti and Cladosporium cladosporoides at different concentrations

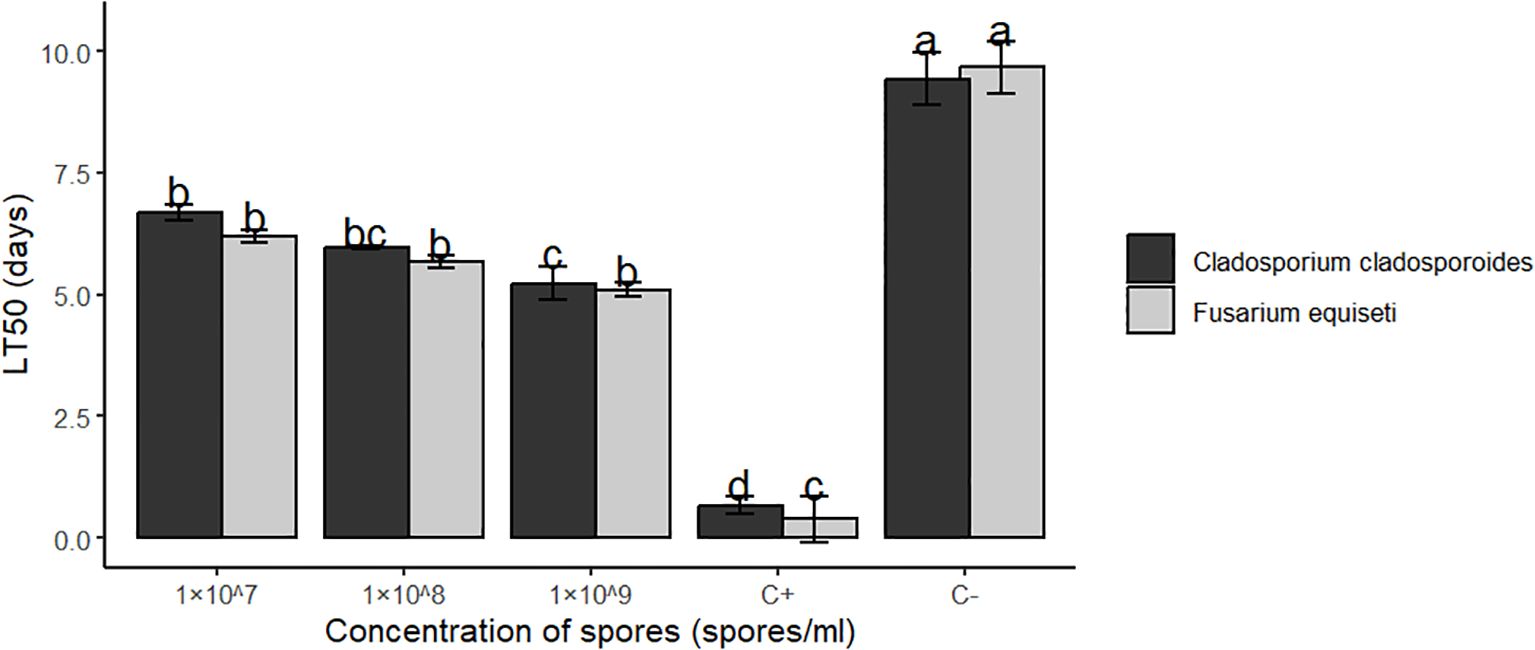

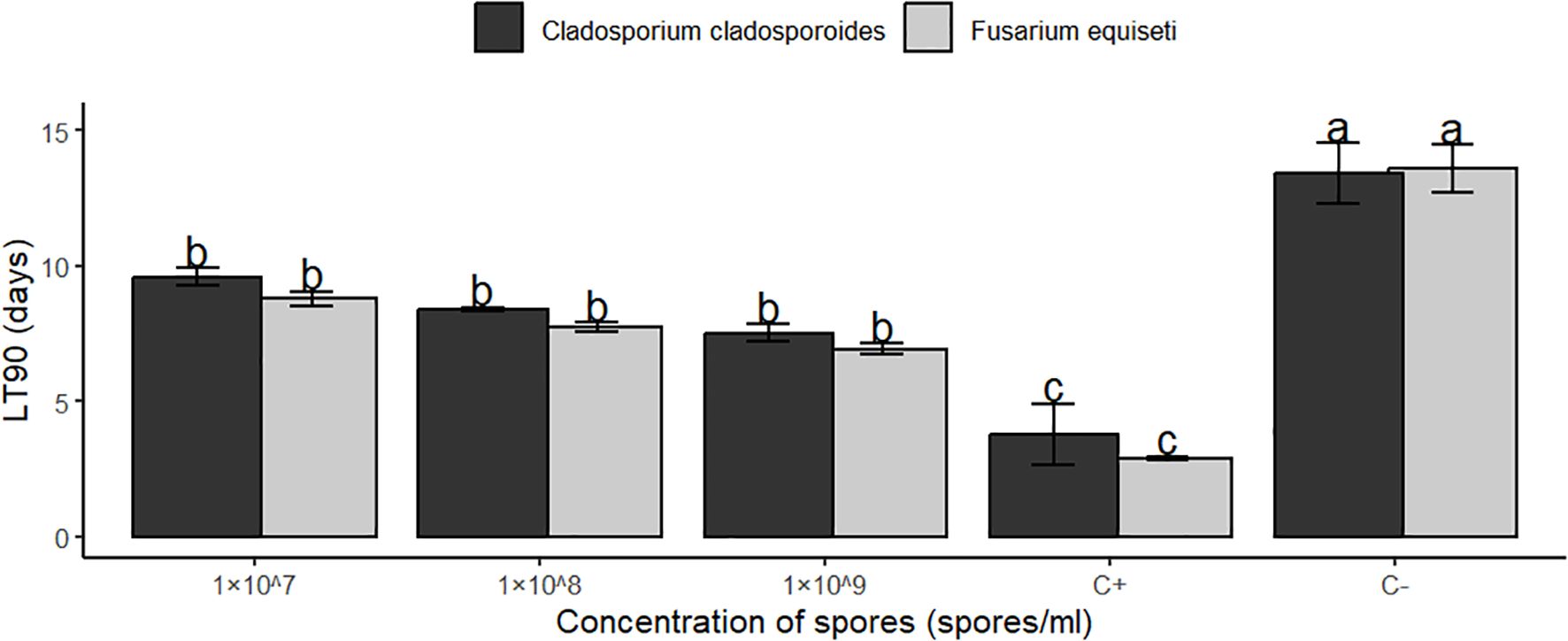

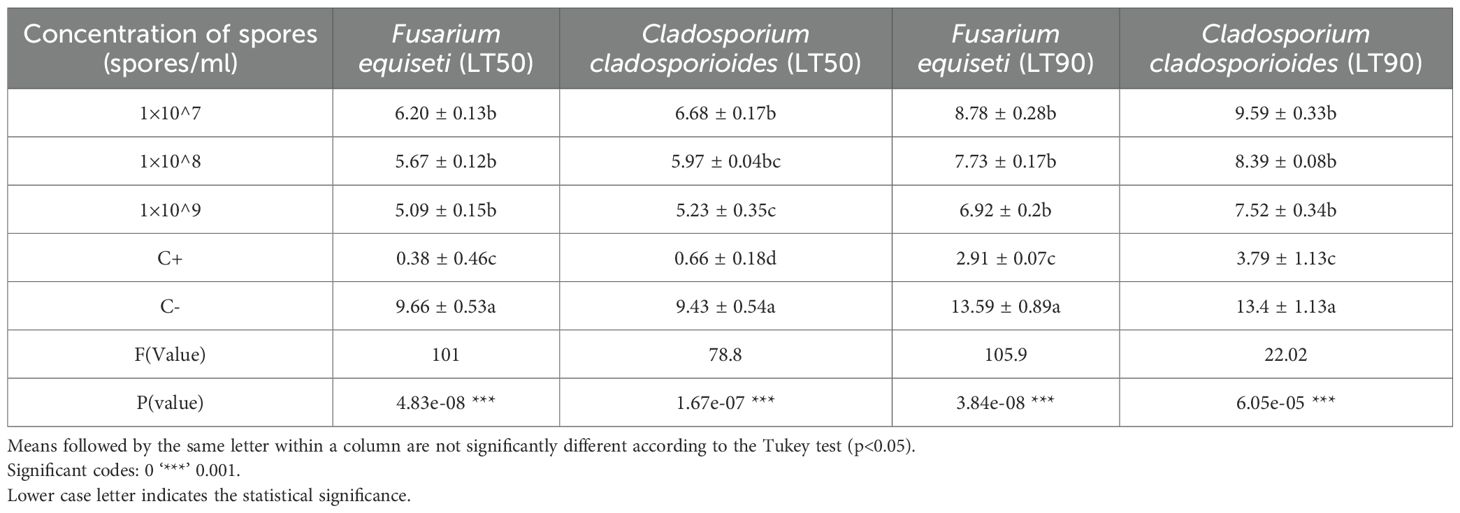

Median lethal time(LT50) and (LT90) results between F.equiseti and C.cladosporioides (The time each concentration took to cause 50% and 90% of aphids’ mortality) differed significantly at P<0.05. The 1× 107 spores’/ml concentrations of both F.equiseti and C. cladosporioides took the longest time of about 6.20 and 6.68 days to kill 50%, 8.78 and 9.59 days to kill 90% of the bean aphids (Table 4, Figures 4, 5) respectively followed by 1× 108 spores/ml which took 5.67 and 5.97 days to kill 50%, 5.67 and 5.97 days to kill 90% of bean aphid, additionally, 1× 109 spores/ml of both F.equiseti and C.cladosporioides took shorter time of about 5.09 and 5.23 days to kill 50% and 6.92 and 7.52 days to kill 90% of bean of aphids (Table 4, Figures 4, 5) respectively. However, positive control (Imidacloprid) took the shortest time of about 0.38 to 0.66 days to kill 50% and 2.9 to 3.7 days to kill 90% of the aphids’ population (Table 4, Figures 4, 5).

Figure 4. Median lethal time (LT50) of Fusarium equiseti and Cladosporium cladosporioides against Aphis fabae at different concentrations followed by the same small letter, do not differ significantly at (P<0.05).

Figure 5. Median lethal time LT90 of Fusarium equiseti and Cladosporium cladosporioides against Aphis fabae at different concentrations means followed by the same small letter do not differ significantly at (P<0.05).

Table 4. Median lethal time (LT50 and LT90) for Aphis fabae treated with two entomopathogenic fungi at different concentrations (1×107, 1×108 and 1×109 spores/ml) along with commercial insecticide (Imidacloprid) and distilled water containing 0.1% Triton X-100 as positive and negative control, respectively.

4 Discussion

4.1 Bioefficacy of Fusarium equiseti and Cladosporium cladosporioides against Aphis fabae

The use of entomopathogenic fungi species in managing black bean aphids has the potential to reduce economic losses caused by these pests, as well as decrease reliance on synthetic insecticides. There is potential to exploit locally available entomopathogens associated with bean aphids. Findings of this study have demonstrated that all fungal isolates (F.equiseti and C. cladosporioides) had a pathogenic effect, on Aphis fabae. However, the effect of the isolated entomopathogenic fungal strains appeared to depend on time and spore concentrations. The results showed that at a concentration of 1× 109 spores/ml of F.equiseti and C.cladosporioides, the cumulative mortality of bean aphids varied between 40.34%, (the lowest), and 93.65%, (the highest), at 7 days’ post-infection. These findings align with previous studies, which reported a maximum mortality of 85.3% and a minimum of 60.0% at higher concentrations of Metarhizium anisopliae at eight days of post-infection (Trinh et al., 2020). Cumulative mortalities caused by (Conidiobolus obscurus, Conidiobolus thromboides, and Basidiobolus ranarum) have additionally been reported ranging from 51.2% to 91.7% against Aphis fabae after 72 hours of post-infection (Halimona and Jenkevica, 2011). In another study by Saranya et al. (2010), 96% and 80% of Aphis craccivora were affected by isolates of Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae, respectively, at 7 days post-treatment. Furthermore, research conducted by Arıcı et al. (2012) on the biological effectiveness of the entomopathogenic fungus Fusarium subglutinans, isolated from cotton aphids, against Aphis fabae, showed significant differences in aphid mortality rates at 25°C, even though no significant difference in mortality rate was observed between 1×107 and 1×108spores/ml.

4.2 The median lethal time (LT50 and LT90) of Fusarium equiseti and Cladosporium cladosporioides

The value of LT50 and LT90 of the two entomopathogenic fungi isolates (F.equiseti and C.cladosporioides against the adults Aphis fabae were also recorded in the present study. As reported in the study, the LT 50 value of F. equiseti and C. cladosporioides at 1 × 109 spores/ml was 5.09 and 5.23, (Table 4) respectively are close to findings of study by Saruhan (2018), who reported a mean lethal time(LT50) of 6 entomopathogenic fungi at a concentration of 1 × 109 spores/ml, ranging from 3.08 to 3.83 days. In another study, three entomopathogenic fungi were used to control Aphis fabae, and LT50 values ranged from 2.79 to 4.24 days (Yeo et al., 2003). At the concentration of 1 × 108 spores/ml of Lamellicola isolate and Verticillium lecanii, LT 50 values were 2.1 and 2.33 days, respectively (Saruhan et al., 2015). The current research findings are however, slightly higher with a difference of 1n to 2.5 days.

As of LT 90 values of the present study, F. equiseti proved to perform better as it took only 6.92 days to kill 90% of Aphids, while C. cladosporioides, took 7.52 days (Table 4). The synthetic insecticides took only 2.91 days. These results align with the results of Saruhan (2018) who used Lecanicillium muscarium to control Aphis fabae, where LT 90 values were found to range between 4.3 days to 6.06 days.

The number of days for F.equiseti and C. cladosporioides to cause 50% and 90% mortality varied slightly; this is due to the inherent ability of entomopathogenic fungi to induce pathogenicity in a targeted insect pest or host within a given period. In earlier findings of Mweke et al. (2018), who evaluated different entomopathogenic fungi for managing Aphis crassivora, some fungal strains took longer or shorter to cause harm to the target insect pest. Another study by Srinivasan et al. (2019) reported that mortality rates caused by Mertahizium anisopliae against bean aphids, could be attributed to the pathogen strain’s ability to cause secondary infections in the targeted pest.

5 Conclusion and recommendation

The isolates obtained, belonging to the entomopathogenic fungi F. equiseti and C. cladosporioides, along with synthetic imidacloprid tested in this study, showed insecticidal effects against Aphis fabae. However, the comparison of results between F.equiseti and C.cladosporioides regarding the mortality of bean aphids indicated that F.equiseti was the more virulent at 7 days post-infection. These results suggest that F.equiseti has potential for development as a microbial biopesticide and could be included in integrated pest management programs aimed at controlling bean aphid populations. Moreover, further evaluation under field conditions is necessary before recommending these isolates for biological control of Aphis fabae.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The manuscript presents research on animals that do not require ethical approval for their study.

Author contributions

JD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MM: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. DM: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

The Department of Crop Science and Horticulture at Sokoine University of Agriculture is gratefully acknowledged by the authors for granting access to the laboratories and other resources used in this work. We also acknowledge Mwalimu Nyerere University of Agriculture and Technology for their valuable support in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abbott W. S. (1925). A method of computing the effectiveness of an insecticide. J. Econ. Entomol. 18, 265–267. doi: 10.1093/jee/18.2.265a

Arıcı S. E., Gülmez I., Demirekin H., Zahmekıran H., and Karaca I. (2012). Efficiency of entomopathogenic fungus Fusarium subglutinans against Aphis fabae Scopoli (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Turk Biyo Muc Derg. 3, 89–96.

Bass C., Denholm I., Williamson M. S., and Nauen R. (2015). The global status of insect resistance to neonicotinoid insecticides. Pesticide Biochem. Physiol. 121, 78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2015.04.004

Blackman R. L. and Eastop V. F. (2000). Aphids on the world’s crops: an identification and information guide. (Chichester, Newyork: John Wiley and Sons).

Boni S. B., Mwashimaha R. A., Mlowe N., Sotelo-Cardona P., and Nordey T. (2021). Efficacy of indigenous entomopathogenic fungi against the black aphid, Aphis fabae Scopoli under controlled conditions in Tanzania. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 41, 1643–1651. doi: 10.1007/s42690-020-00365-8

Dauda Z. and Maina U. M. (2018). A review on the use of entomopathogenic fungi in the management of insect pests of field crops A review on the use of entomopathogenic fungi in the management of insect pests of field crops. Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies. 6: 27–32.

Esmaeili-Vardanjani M., Askarianzadeh A., Saeidi Z., Hasanshahi G. H., Karimi J., and Nourbakhsh S. H. (2013). A study on common bean cultivars to identify sources of resistance against the black bean aphid, Aphis fabae Scopoli (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 46, 1598–1608. doi: 10.1080/03235408.2013.772351

Halimona J. and Jenkevica L. (2011). The Influence of Entomophtorales Isolates on Aphids Aphis fabae and Metopeurum fuscoviride. Latjivas Entomologs. 50, 55–60.

Hoggard M., Vesty A., Wong G., Montgomery J. M., Fourie C., Douglas R. G., et al. (2018). Characterizing the human mycobiota: A comparison of small subunit rRNA, ITS1, ITS2, and large subunit rRNA genomic targets. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1–14. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02208

Kacholi D. S. (2020). Population structure, harvesting rate and regeneration status of four woody species in Kimboza forest reserve, Morogoro region, Tanzania. Population. 2020, 2:09–30. doi: 10.22271/2582-3744.2020.sep.94

Litwin A., Nowak M., and Ro S. (2020). Entomopathogenic fungi: unconventional applications, (Berlin, Germany: Springer) 1. 23–42. doi: 10.1007/s11157-020-09525-1

Maina U. M., Galadima I. B., Gambo F. M., and Zakaria D. J. J. O. E. (2018). A review on the use of entomopathogenic fungi in the management of insect pests of field crops. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 6, 27–32.

McGuire A. V. and Northfield T. D. (2020). Tropical Occurrence and Agricultural Importance of Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 4. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2020.00006

Mweke A., Ulrichs C., Nana P., Akutse K. S., Kouma K., Fiaboe M., et al. (2018). Biological and Microbial Control Evaluation of the Entomopathogenic Fungi Metarhizium anisopliae, Beauveria bassiana and Isaria sp. for the Management of Aphis craccivora (Hemiptera: Aphididdae). Journal of Economic Entomology. 111, 1587–1594. doi: 10.1093/jee/toy135

Nordey T., Basset-Mens C., De Bon H., Martin T., Déletré E., Simon S., et al. (2017). Protected cultivation of vegetable crops in sub-Saharan Africa: limits and prospects for smallholders. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 37:37–53. doi: 10.1007/s13593-017-0460-8

Saranya S., Ushakumari R., Jacob S., and Philip B. M. (2010). Efficacy of different entomopathogenic fungi against cowpea aphid, Aphis craccivora (Koch). J. Biopesticides. 3, 138–142.

Saruhan I. (2018). Efficacy of some entomopathogenic fungi against Aphis fabae scopoli (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Egyptian J. Biol. Pest Control 28, 1–6. doi: 10.1186/s41938-018-0096-2

Saruhan I., Erper I., Tuncer C., and Akca I. (2015). Efficiency of some entomopathogenic fungi as biocontrol agents against Aphis fabae scopoli (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Pakistan J. Agric. Sci. 52, 273–278.

Sharma A., Kumar V., Shahzad B., Tanveer M., Sidhu G. P. S., Handa N., et al. (2019). Worldwide pesticide usage and its impacts on ecosystem. SN Appl. Sci. 1, 1–16. doi: 10.1007/s42452-019-1485-1

Srinivasan R., Sevgan S., Ekesi S., and Tamò M. (2019). Biopesticide based sustainable pest management for safer production of vegetable legumes and brassicas in Asia and Africa. Pest Manage. Sci. 75, 2446–2454. doi: 10.1002/ps.5480

Stoddard F. L., Nicholas A. H., Rubiales D., Thomas J., and Villegas-Fernández A. M. (2010). Integrated pest management in faba bean. Field Crops Res. 115, 308–318. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2009.07.002

Thaochan N. and Sausa-Ard W. (2017). Occurrence and effectiveness of indigenous Metarhizium anisopliae against adults Zeugodacus cucurbitae (Coquillett)(Diptera: Tephritidae) in Southern Thailand. Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol. 93:325–334.

Trinh D. N., Ha T. K. L., and Qiu D. (2020). Biocontrol potential of some entomopathogenic fungal strains against bean aphid megoura japonica (Matsumura). Agric. (Switzerland) 10, 10–12. doi: 10.3390/agriculture10040114

Wamonje F. O., Donnelly R., Tungadi T. D., Murphy A. M., Pate A. E., Woodcock C., et al. (2020). Different plant viruses induce changes in feeding behavior of specialist and generalist aphids on common bean that are likely to enhance virus transmission. Front. Plant Sci. 10. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01811

Yeo H., Pell J. K., Alderson P. G., Clark S. J., and Pye B. J. (2003). Laboratory evaluation of temperature effects on the germination and growth of entomopathogenic fungi and on their pathogenicity to two aphid species. Pest Manage. Sci. 59, 156–165. doi: 10.1002/ps.622

Zanic K., Ban D., Gotlin Culjak T., Ban S. G., Dumicic G., Haramija J., et al. (2013). Aphid populations (Hemiptera: Aphidoidea) depend of mulching in watermelon production in the Mediterranean region of Croatia. Spanish J. Agric. Res. 11, 1120–1128. doi: 10.5424/sjar/2013114-4349

Zekeya N., Mtambo M., Ramasamy S., Chacha M., Ndakidemi P. A., and Mbega E. R. (2019). First record of an entomopathogenic fungus of tomato leafminer, Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) in Tanzania. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 29, 626–637. doi: 10.1080/09583157.2019.1573972

Keywords: Entomopathogenic fungi, Fusarium equiseti, Cladosporium cladosporioides, Aphis fabae, Phaseolus vulgaris

Citation: Damian JF, Martin MJ and Msuya DG (2025) Biocontrol potential of Fusarium equiseti and Cladosporium cladosporoides against Aphis fabae under controlled conditions. Front. Agron. 7:1689350. doi: 10.3389/fagro.2025.1689350

Received: 20 August 2025; Accepted: 24 November 2025; Revised: 20 November 2025;

Published: 12 December 2025.

Edited by:

Seema Ramniwas, Marwadi University, IndiaReviewed by:

Eustachio Tarasco, University of Bari Aldo Moro, ItalyTarun Kumar Patel, Sant Guru Ghasidas Government P.G. College, India

Copyright © 2025 Damian, Martin and Msuya. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jedius France Damian, amVkaXVzLmRhbWlhbkBtbnVhdC5hYy50eg==

Jedius France Damian

Jedius France Damian Martin John Martin3

Martin John Martin3