Abstract

In Sweden, homeless cats are primarily considered an animal welfare issue and are protected by animal welfare legislation. The 21 regional County Administrative Boards (CABs) are responsible for enforcing this legislation and acting if non-compliance is detected. According to the Swedish Animal Welfare Act, homeless cats are suffering per se, and hence the CABs must take measures to seize the cats. However, the CABs do not have any cat shelters of their own; instead, they are supposed to procure private cat shelters to handle homeless and neglected cats. This study aimed to scrutinise the collaboration between the CABs and contracted private cat shelters regarding the handling of homeless cats in Sweden. More specifically, the study examined the content and demands of these contracts, and how the cat shelters’ staff perceived this collaboration. Official documentation regarding procured cat shelters was analysed, and eight cat shelters from different counties were interviewed. Of the 21 CABs, 17 had contracts with cat shelters. The contracts varied somewhat in content but generally included demands relating to the competence of shelter staff, accessibility and lead times, documentation, equipment, and reimbursement. Most CABs also demanded that cat shelters take ownership of cats when the CAB decided. For homeless cats, this could be immediately after capture. The cat shelters were aware that they were partly being used by the CABs, i.e. they were doing some of the government’s work without full financial compensation. However, they also showed understanding for the CABs’ limited resources and were often willing to take ownership of cats early to avoid possible euthanasia decisions made by the CAB. Nevertheless, the large number of homeless cats in Sweden shows that the current system is ineffective. All relevant actors, including cat owners and the authorities, must take responsibility for their obligations.

1 Introduction

There are various reasons why cats may become homeless. They may run away, which is more likely if they are not neutered (Robertson, 2008). They may also be abandoned by their owners or born by a homeless mother (Robertson, 2008). Reasons for abandoning a cat may be reduced interest, allergy, lack of time and moving (Eriksson et al., 2009). Today, the presence of homeless cats is seen as a global problem. However, the problem has different angles. Some argue that cats threaten wild animal populations due to predation and disease (Deak et al., 2019), considering them to be pests and invasive species that threaten biodiversity and pose a biosecurity risk (Lepczyk et al., 2022; Riley, 2019). Others consider homeless cats to be a public nuisance (Robertson, 2008), whilst some are concerned about animal welfare issues affecting homeless cats (Robertson, 2008; Sparkes et al., 2013). There is a widespread misconception that cats, unlike our other pets, always can survive and thrive on their own (SOU 2011:75). In fact, homeless cats are at a large risk of suffering from e.g. starvation, frostbite, diseases, injuries, fear, and social stress (Scott et al., 2002; Gilhofer et al., 2019; Griffin et al., 2020; Grieco et al., 2021). However, there is no real consensus on the scale of such welfare issues since few studies have been conducted and the methods, measures and conclusions differ between them (Thuesen et al., 2022). It is estimated that there are at least 100–000 homeless cats in Sweden (Ds 2019:21, 2019). This equates to around 7% of the total cat population in Sweden. However, this figure may be an underestimation, given that the proportion of homeless cats has been estimated to be much higher in comparable countries, e.g. 20% in the UK (Tabor, 1981) and 33–55% in the US (Slater, 2007). Conversely, Nielsen et al. (2022) concluded that the estimated number of 500–000 homeless cats in Denmark was an overestimation, as they recalculated this figure to 89 000 ± 11–000 cats.

The management solutions for homeless cats differ depending on why they are seen as a problem in a given country or region. If cats are considered invasive predators, the strategy is often to kill them in order to reduce their numbers. This is sometimes done using non-humane methods, such as leg-hold traps (Short et al., 2002), despite a lack of evidence regarding the long-term effects on the populations (Palmas et al., 2020). However, if there is concern for cat welfare, other methods are used to limit the number of cats, such as Trap-Neuter-Release (Spehar and Wolf, 2019), placement in cat shelters, or rehoming (Hurley and Levy, 2022). The actions taken when handling homeless cats also depend on their age and the extent to which they are socialised. An unsocialised adult cat can be difficult to socialise to the point where it can be adopted as a pet, whereas an unsocialised kitten is easier to socialise and adopt (Graham et al., 2024). There is also a risk that unsocialised cats will suffer from fear and distress if they are kept in e.g. a shelter (Kessler and Turner, 1999). Therefore, people who are concerned about the welfare of these unsocialised cats may favour euthanasia as a means of preventing unnecessary suffering if no other suitable option exists (Nielsen et al., 2023; Sandøe et al., 2015).

Catching, handling and managing homeless cats is labour-intensive and costly (Ds 2019:21, 2019; Wolf and Hamilton, 2022). The way in which this labour is organised varies between different countries, but in general it is often dependent on unpaid work by public or private cat shelters (Deak et al., 2019; Hurley and Levy, 2022). Many countries have also introduced legislation related to homeless cats, both to prevent cats from becoming homeless by placing more responsibility on cat owners, but also to provide legal frameworks for action when homeless cats are found (Fossati, 2024). Contalbrigo et al. (2024) concluded that there is no common EU strategy for protecting domestic cats, despite the need for one.

In Sweden, the presence of homeless cats is primarily considered an animal welfare issue (Ds 2019:21, 2019). The country’s distinct and cold winter season leaves the welfare of these cats at great risk (SOU 2011:75). Hence, homeless cats are protected by the Swedish animal welfare legislation. The Swedish Animal Welfare Act (SFS 2018:1192, 2018) clearly states that abandoning animals (e.g. cats) is forbidden and punishable, and uncontrolled reproduction of cats is prohibited (SJVFS 2020:8, 2020). Since 2023, all cat owners in Sweden are also required to ID-mark and register their cats with the Swedish Board of Agriculture (SFS 2007:1150, 2007).

The competent authorities responsible for enforcing animal welfare legislation in Sweden are the 21 regional County Administrative Boards (CABs) (see Figure 1). According to the bill for the Animal Welfare Act, a homeless animal should be considered to be suffering per se (Prop. 2017/18:147). The Animal Welfare Act states that the CABs “shall seize an animal if it is suffering and the owner is unknown”. Therefore, according to animal welfare legislation, the CABs have a clear duty to act when cats are homeless. The CABs are also obliged to seize cats if they have an owner that neglects them. If CAB staff are unavailable, the police have the authority to seize animals in urgent situations. However, the CAB shall decide whether the police decision should remain in force. Once an animal has been seized, the CAB becomes its legal owner and is responsible for its present care and future destiny. According to the Animal Welfare Act (SFS 2018:1192, 2018), the CAB must decide whether the animal should be sold, transferred in some other way or euthanised.

Figure 1

A schematic overview of the organisation of animal welfare legislation and the operative enforcement of the legislation in Sweden. The different parts of the country represent the 21 counties, all led by a County Administrative Board (CAB). Cat shelters (depicted by different coloured circles) are all privately managed, either completely or partially relying on unpaid work. Cat shelters can be found all over the country and are rarely collaborating systematically.

The CABs do not have any cat shelters of their own; in fact, there are no publicly financed cat shelters in Sweden. Instead, to handle homeless and owned but neglected cats, the CABs are supposed to procure more or less local cat shelters with which they cooperate (e.g. for catching, housing and caring for the cats) (SFS 2016:1145, 2016). These cat shelters are private initiatives, financed by public donations (i.e. they do not receive any public funds), and generally depend on voluntary work. Public procurement is the process by which government agencies and other public entities purchase goods and services, a process that is governed by EU and national legislation (Handler, 2015).

The overarching aim of this study was to examine the collaboration between the competent authority — the county administrative boards (CABs) — and private cat shelters regarding the management of homeless cats in Sweden. More specifically, the first aim was to investigate whether the CABs had written contracts with private cat shelters resulting from public procurements and, if so, to examine the content and requirements of these contracts. The second specific aim was to examine how cat shelter staff perceived this collaboration.

2 Material and methods

2.1 The CABs’ procurements

In Sweden, anyone can request public documents from the authorities. This creates great transparency around the work of the authorities, and thus, also good opportunities to study the work of the authorities scientifically. During the spring of 2023, Sweden’s 21 CABs were contacted by email and asked to provide documents containing the requirements imposed on cat shelters in procurement, as well as the allocation decisions (i.e. the contracts). If a CAB did not have a contract with a cat shelter, they were asked to confirm this. In cases where there was no response, or where the requested material was not included, reminder emails were sent in summer and autumn 2023.

The CABs were randomly numbered to keep them anonymous. The procurements and contracts resulting from the procurement process were analysed using an inductive thematic approach, defining nine focus areas related to the requirements set out in the contracts.

-

Number of cat places.

-

Staff and training.

-

Accessibility.

-

Lead time.

-

Documentation.

-

Adoption and ownership.

-

Euthanasia.

-

Equipment.

-

Reimbursement.

These focus areas were used to analyse the contracts between CABs and cat shelters, and the differences and similarities were noted.

2.2 Interviews with cat shelters

The CABs were also asked to provide contact information for the cat shelters they collaborated with. However, as this request was not granted due to confidentiality concerns, the contact information of the cat shelters was found through web searches. The shelters were first contacted via email to inform them about the study, and then by telephone.

Eight semi-structured interviews (George, 2022) were conducted over the telephone in autumn 2023. The interviewees were cat shelter staff who, during the interview period, had a contract with one or more CABs. The participants received the interview questions (Suppl. 1) via email beforehand. The interviews were recorded once informed consent had been given by the interviewee, and the recordings were transcribed manually afterwards. The analysis focussed on recurrent themes and keywords. Rare but relevant views, words or opinions were also included.

Cat shelters were anonymised by coding. Their code contained the same number as the CAB with which they negotiated. If a shelter negotiated with several CABs, it received only one code.

3 Results

3.1 Contracts

Seventeen of the 21 CABs replied that they had contracts with at least one cat shelter. Of these, three did not have their own contract but used another CAB’s. Four CABs stated that they did not have any contracts with cat shelters. One of these stated that they used direct sourcing when needed; two left no comment; and the fourth replied that no cat shelters had responded to their procurement.

Several CABs had contracts with more than one cat shelter. It was also common for the contracts to state that nearby CABs could use the cat shelter in the current county. All contracts stated that the police could use the shelter when needed.

Hence, 14 unique contracts were analysed and compared within this study.

3.2 Focus areas – requirements in the contracts

3.2.1 Number of cat places

It could be mentioned that in Sweden it is forbidden according to the animal welfare legislation (SJVFS 2020:8, 2020) to keep cats in cages, hence, a “cat place” thus means a place in an individual enclosure or in a group enclosure. According to the legislation, a single cat enclosure must have an area of at least 1.5 m² and a height of at least 1.9 m. However, cats can only be kept in this way for up to 90 days. After this period, the minimum area required for a single cat is 6 m². To avoid overcrowding, the area must increase by a certain amount for each additional cat in a group enclosure. The area must increase by 0.7 m² for up to 90 days and by 2 m² after 90 days. The number of cat places at the shelter that were to be used by the CABs was not specified in any of the contracts, and the level of service requested by the CABs varied from contract to contract. Some contracts stated that the cat shelter was expected to accept cats “up to capacity”, whilst others said that the cat shelter did not need to guarantee space for all cats. However, several contracts stated that the cat shelter “needed to provide space” when requested by the CAB. None of the contracts stated that any additional reimbursement would be provided, even though the shelters were expected to provide space for cats handed over by the CABs.

3.2.2 Staff and training

All contracts set out requirements for the competence of cat shelter staff. In some cases, both education and experience were required, whereas in others, experience alone was sufficient. Furthermore, it varied whether the CABs specified what was expected to be included in the concept of competence. Some contracts did not describe this in detail, whilst others requested specific knowledge, such as handling feral, scared or aggressive animals, feeding them, and assessing their level of stress and mentality. For instance, several contracts stated that cat shelters should ‘be able to provide a written assessment of the animals’ mentality as a basis for the CAB’s decision on what should happen to the animal’.

Additionally, four contracts specified that cat shelters must have management staff responsible for operations. This person was required to have at least three years’ education as an animal caretaker or equivalent, or alternatively at least three years’ professional experience in cat care and keeping. Some contracts specifically mentioned interns and volunteers, stating that they needed explicit guidance.

Twelve of the 17 CABs reserved the right in the contracts to demand that the cat shelters replace specific individuals in their staff upon request. Whilst the exact wording varied, the most common was ‘The contractor is obliged, without undue delay, to replace personnel whom the CAB deems to lack the necessary competence, or with whom the CAB experiences difficulties in cooperating’. Three of the CABs also requested that the cat shelters must not replace any staff without first obtaining written approval from the CAB. In contrast, the remaining five CABs did not include such wording in their contracts.

3.2.3 Accessibility

The level of accessibility demanded by the CABs for cat shelters’ services varied (Table 1). In at least 41% of counties, cat shelters were expected to provide services at all times. The police also had the right to use all CAB contracts when needed, often including weekends and nights, even in counties where CABs only reserved the right to use cat shelters during the day.

Table 1

| County | 24/7 | Week days 6AM–8PM | Week days 7AM–5PM | Week days 8AM–5 PM | Not stated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | x | ||||

| 2 | x | ||||

| 3 | x | ||||

| 4 | |||||

| 5 | x | ||||

| 6 | x | ||||

| 7 | x | ||||

| 8 | x | ||||

| 9 | x | ||||

| 10 | x | ||||

| 11 | x | ||||

| 12 | x | ||||

| 13 | x | ||||

| 14 | x | ||||

| 15 | x | ||||

| 16 | x | ||||

| 17 | x |

The County Administrative Boards’ demands for accessibility that should be provided by cat shelters.

The majority of cat shelters were requested to ensure that the cats were examined by a veterinarian. In five counties, this was to be done within 24 hours; in five other counties, ‘as soon as possible’ (often meaning the same or the following weekday); in two counties, ‘upon request by the CAB’; in one county, within three days; and in the remaining four, it was not specified.

Cat shelters were also expected to be able to receive unannounced visits from the CAB. Many of the cat shelters were expected to provide ‘quick feedback’ (often within two hours) and answer questions about the cats’ health, mental status, veterinary treatments, etc. Furthermore, all cat shelters were expected to participate in meetings at the start, during and end of a contract, without reimbursement.

3.2.4 Lead time

The lead time was the stipulated amount of time before the cat shelter staff were required to be available for the CAB’s service, for the purpose of catching or picking up one or more cats from any location specified by the CAB. The most common lead time stated in most of the contracts was three hours. Hence, the shelter staff should be out capturing cats within three hours from being contacted by the CAB. However, all contracts stated that exceptions to this rule could be made.

3.2.5 Documentation

Most contracts required the cat shelters to keep documentation on each individual cat. Only three of the contracts did not specify what needed to be documented; the remaining contracts specified this to different degrees. Four of the contracts required a high level of detail, including documentation of housing time, the physical and mental condition of each cat, changes in general condition and behaviour, feed and water intake, urine and faeces, bathing, claw trimming, grooming and medical treatments. In addition, the cat’s weight had to be recorded on the first and last day in the shelter.

In addition to this, it was common for the contracts to state that the cat shelters were expected to provide written statements on the mental status of each cat and whether or not they were considered adoptable.

3.2.6 Adoption and ownership

All contracts included a requirement for the cat shelters to assist the CABs with the adoption or sale of cats. Whilst none of the contracts mentioned a compensation for this work, in some cases it was included in the daily fee that the CAB paid for housing the cats. An example of a clause in the contracts could be: “The supplier [i.e. the shelter] should advertise the animal for sale within 24 hours of receiving a request from the CAB. They should also answer questions about the animal, evaluate interest requests, send these on to the CAB along with the names, addresses and social security numbers of interested adopters/buyers, show the animals to potential adopters/buyers, hand the animals over and ensure that the sales contract is signed promptly after the sale and sent to the CAB (by the end of the next day at the latest). No refunding will be charged for doing this”.

In addition to handling sales and adoptions, most (70%) of the CABs also requested that the cat shelters take over cat ownership from the CAB when the CAB expected so. This meant that the shelter was responsible for the cat and all associated costs (e.g. feeding and veterinary care) until the cat was sold or euthanised. One contract stated that the cat shelter “must accept ownership after a CAB decision”. Another contract stated that the cat shelter should “accept ownership of the animal immediately when it is a homeless cat that is caught. This means that subsequent costs are paid for by the supplier [i.e. the shelter]”.

3.2.7 Euthanasia

All contracts required the cat shelters to make an appointment and transport animals to a veterinarian for euthanasia if the CAB decided so. This was to be done promptly, usually on the same or the following day.

The contracts also contained wording stating that the CAB must always be contacted to approve the treatment of sick or injured cats owned by the CAB. Even if the CAB could not be reached, the cats should still receive treatment: “In the event of acute illness or injury outside office hours, decisions on the treatment of animals, or where appropriate, euthanasia, are made in dialogue between the supplier [i.e. the cat shelter] and the veterinarian”. However, the following reservation was included: “If the animal’s acute condition requires costly treatment, the animal should be euthanised unless it is a very valuable animal”.

Several contracts contained the following statement: “The intention of the CAB is that animals taken into its care should firstly be sold and secondly given away. If this is not possible within a reasonable timeframe, the animal should be euthanised instead”.

3.2.8 Equipment

According to the terms of all the contracts, the cat shelters were expected to provide all the necessary equipment for the “professional capture” of cats. This equipment included hand nets, traps with an alarm function, feed and protective gloves, among other things. The shelters were also expected to have vehicles that were equipped in accordance with the Swedish Board of Agriculture’s regulations and recommendations on the transportation of animals. These vehicles were to be checked and approved by the CABs.

The cat shelters were responsible for wear and tear, damaged equipment and cleaning equipment and vehicles, without financial compensation.

3.2.9 Reimbursement

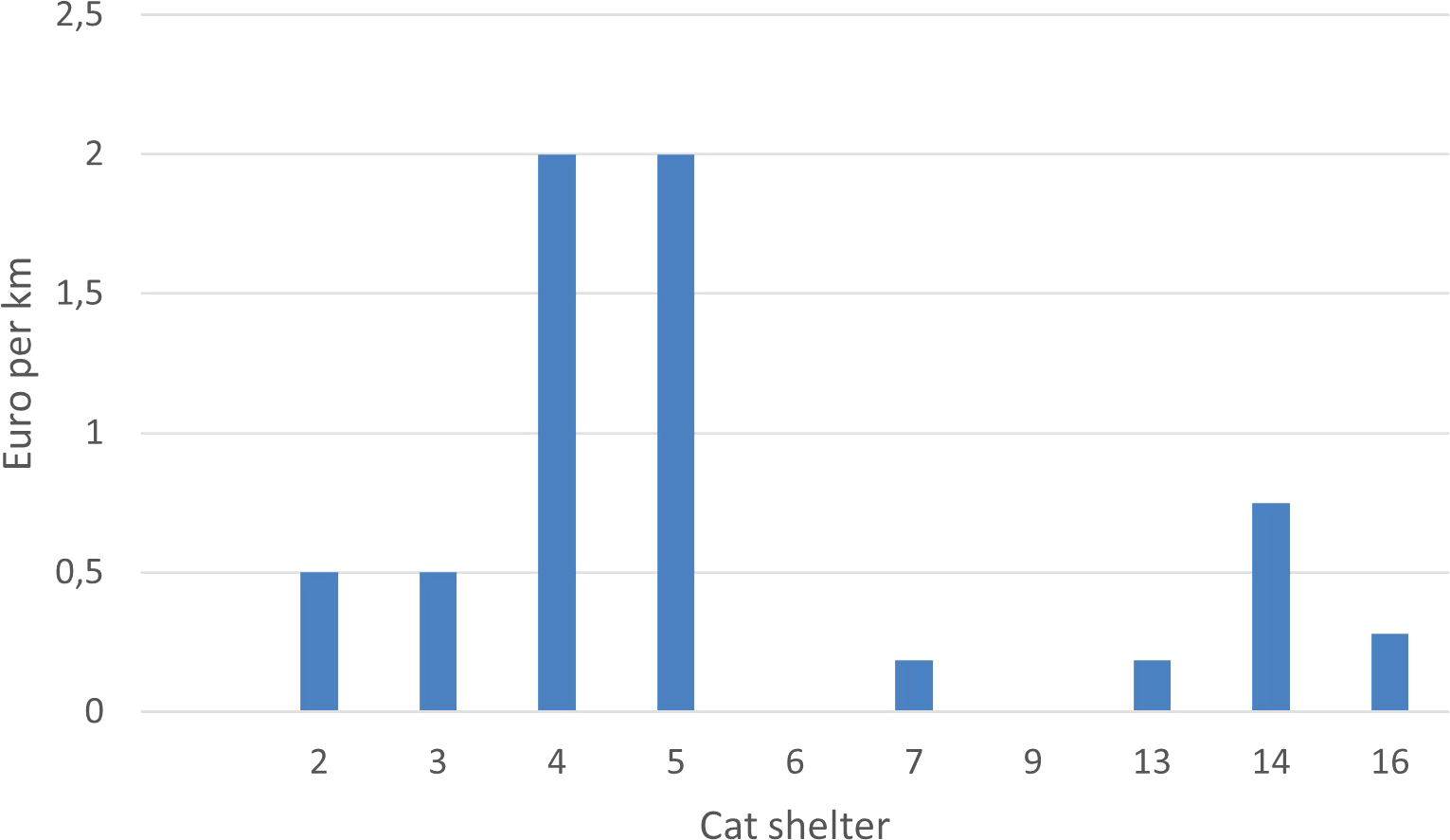

When it came to the compensation that the cat shelters were supposed to receive for their efforts, the contracts were usually divided into two parts. One part covered the shelters’ catching and transport of cats, i.e. financial compensation per kilometre driven (Figure 2) and an hourly payment for time spent (Figure 3). Three cat shelters were paid double the hourly reimbursement at weekends and a slightly higher reimbursement outside office hours. However, some CABs received a fixed amount (50 EUR) per cat caught, regardless of the time taken or distance travelled.

Figure 2

Reimbursement from the County Administrative Boards (CABs) that compensated the Swedish cat shelters per km driven (not all CABs did so).

Figure 3

Reimbursement per hour worked, e.g. when catching cats and per day for housing the cats. The contracts varied in how the compensation was calculated depending on day and time. Cat shelters 4, 5, 14 and 16 offered higher reimbursement for work carried out outside office hours (not included in the graph).

The second part of the contracts concerned housing the cats. Here, the shelters were paid per day that they kept and cared for the CABs’ cats. Some CABs had a maximum cost limit of 250 EUR per cat, including catching, transport and housing. Another contract stated that catching a homeless cat could cost a maximum of 150 EUR, and that ownership would immediately transfer from the CAB to the cat shelter. This meant that the cat shelter would cover all costs, and no day fee would be paid by the CAB.

Despite the lack of some detailed information in the contracts, it was evident that the amount of financial compensation given by the CABs to the cat shelters varied greatly (Figures 2, 3).

The daily fee paid by the CABs to the cat shelters was expected to cover suitable housing, cleaning of the facilities, feed, daily care, and basic veterinary care. The daily fee for some contracts included assisting the veterinarian, for example, with examinations or ID-tagging. However, some CABs did pay an hourly rate for this type of work.

The contracts often contained statements in which the cat shelters agreed to do everything they could to keep costs as low as possible.

3.3 Cat shelter perception of contract conditions stipulated by the CABs

The perceptions of cat shelters regarding their contracts with CABs were found to fit into three categories. One group of shelters described the contracts as “unjust with unreasonable demands” and only accepted them because they wanted to help the cats. A second group described the demands as “fairly reasonable”, but emphasised that they were disproportionate to the low payment. The third group found the demands “pretty self-evident” and said the collaboration worked “excellently”. It should be noted that these comments refer to the shelters’ unique contracts.

Most of the cat shelters said that the financial compensation was generally far lower than the actual costs. Cat shelters require traps with alarms, cages, transport vehicles, protective gear, etc., to provide the services demanded by the CABs, and many of them must have staff prepared to respond at any time if the CABs or the police require assistance. The shelters also pointed out that the daily fee they receive does not always cover staff costs.

One cat shelter had contracts with three different CABs and considered it unreasonable that the content of the agreements differed so much. For example, one CAB required cats to be vaccinated at the time of veterinary inspection on the day of capture if they were healthy enough, whilst the other two did not allow cats to be vaccinated immediately after capture. Apart from the risk of the cats getting sick and transferring diseases to other cats, a consequence of this was that adoption took much longer. The shelter first had to wait, sometimes for weeks, for the CAB to approve the vaccination. This prolonged the process and the cats’ stay at the shelter, resulting in additional costs and an unnecessary occupation of a shelter place.

Some cat shelters mentioned that the contracts with the CAB negatively impacted the working environment. This was due to staff working unpaid and always being on call, as well as the risks and dangers they sometimes had to face. For example, one cat shelter was once asked by the CAB to collect a cat from a youth hostel because the owner was mistreating the animal. It is common knowledge that threats, and sometimes violence, are associated with the seizure of animals by authorities (Lundmark Hedman et al., 2025). However, the individual from the cat shelter was not supported by staff from youth hostels, CAB, or the police. For safety reasons, the cat shelter decided to send two people; however, the CAB refused to pay for the second person.

3.4 Cat shelter perception of CAB handling of homeless cats

Most cat shelters considered the CABs’ procedures for dealing with homeless cats to be dysfunctional. Only two stated that the CABs had well-functioning systems in place. Furthermore, six cat shelters described how the CABs only dealt with cats that had been reported as being mistreated, and never with cats that were truly homeless. One reason for this was that, if an owner could be identified, the CAB could make them pay for the costs associated with capture and care. Several cat shelters described the CABs as not having enough resources to fulfil their legal duties and therefore used cat shelters to do it for them, generally without any or full compensation. Some shelters also mentioned that, when a concerned citizen contacts the CAB about a homeless cat, it is common practice for the CAB to recommend that they call a cat shelter instead, i.e. the CAB avoids taking action itself. However, cat shelters generally did not blame the CABs for deprioritising homeless cats, but rather the politicians responsible for the CABs’ resources.

Shelters also mentioned that CABs sometimes went beyond their contracts by asking citizens who contacted them about homeless cats to phone a non-profit cat organisation instead of the contracted cat shelter for assistance. It was perceived that the CAB only called the contracted cat shelter for the agreed assistance when these non-profit organisations could not deal with the situation. Cat shelters saw this as a way for CABs to reduce costs further.

3.4.1 Cat shelter perception of how CABs handle shy and unsocialised homeless cats

Most of the cat shelters interviewed described a widespread lack of knowledge about shy or unsocialised cats among the CABs. The shelters expressed great concern that cats are assessed as unsocial when they are actually severely stressed by the situation. One cat shelter reported an incident in which the CAB, the police, a hunter and a veterinarian went to a cat colony, euthanised all the cats they could find and then decided the problem was solved. In reality, they had euthanised the most social cats and left the truly unsocialised cats with no opportunity for rehabilitation. However, in contrast, one cat shelter representative said that the handling of shy cats works well in their county.

Regardless of the CABs’ perceptions, views among the cat shelters varied on how truly shy and unsocialised cats should be rehabilitated and how long this process should be allowed to take. Several shelters felt that the CAB had an unrealistic view of how long it takes to socialise a cat in order to prepare it for adoption. They described very good results, but said that the cats needed time: “It doesn’t take weeks, it takes months”. They also said that the CABs were impatient and lacked scientific evidence to support their expectations. Those shelters expressed frustration that the CAB did not allow them to work at a pace they considered appropriate, despite their willingness to take on the cats and cover all costs. However, also in these cases, the shelters said that it was important not to blame the CAB staff, but rather the politicians who provide the regulations and financial resources for the CABs. Shelters that were more critical of the rehabilitation of shy cats referred to the fact that they believed the cats were subjected to too much stress, which was not justifiable from an animal welfare point of view.

3.4.2 Euthanasia and no kill-policy

The cat shelters were asked if they had a ‘no kill’ policy, which some of them did, whereas most did not. However, whether or not they had a ‘no kill’ policy, the cat shelters worked in a strikingly similar way. They usually spent a lot of time and resources on treating, rehabilitating and socialising cats with the ultimate goal of adoption. Euthanasia was only ever used as a last resort, for example when a shy and fearful cat required extensive medical care but experienced extreme stress during treatment, or when the prognosis for recovery was very poor for a sick or injured cat.

All shelters seemingly had to accept that the CABs could decide to euthanise cats, and all contracts stipulated that shelters must transport cats to designated clinics for euthanasia. A ‘no-kill policy’ could only apply to cats owned by the shelters (and not those owned by the CAB).

3.4.3 Cat shelter perception on the financial responsibilities, including ownership

Cat shelters stated that the financial compensation they received from CABs often did not cover costs relating to equipment, time or staff. It was common for ownership of truly homeless cats, often colony cats, to be transferred to the shelter immediately upon capture or directly after a veterinary examination. The shelters perceived that the CABs wanted to transfer ownership to them as soon as possible to avoid further costs. The cat shelters also explained that they usually accepted ownership to prevent the CABs from euthanising cats hastily.

In cases where a cat had an owner who neglected it and was captured by the CAB or the police, the cat shelter housed the cat on behalf of the CAB until a final decision about the cat was made (usually after the appeal period of a couple of weeks had passed). During this time, the shelters were paid per 24 hours of housing.

The cats were usually examined by a veterinarian shortly after capture. The aim was partly to document their health status and partly to provide evidence in the event of prosecution of the owner. The CABs usually paid for the veterinary examination and the cats were usually ID-tagged at the same time. The CABs also covered the cost of euthanising very sick or injured cats that had been captured. Simpler veterinary interventions were often paid for by the CABs, but more complex health issues usually led to a decision about euthanasia.

According to the cat shelters, the CABs rarely paid for vaccinations. These were generally considered to be non-emergency healthcare, alongside neutering and dental work, for example. The cat shelter was responsible for providing and paying for this care after ownership had been transferred from the CAB. In some cases, cat shelters also had to pay for ID tagging.

The extent to which cat shelters were willing to contribute financially to saving an individual cat’s life varied. Some shelters stated that finances were never a factor in deciding what to do with a cat; only the cat’s welfare mattered. However, other shelters said that, in some cases, they had deemed a measure too costly in relation to how many healthier cats they could help with the same amount of money.

3.4.4 Cat shelters prioritisation of cats in need

The ability of cat shelters to always accept cats from CABs varied. If this was a requirement in the contract, it would vary if shelters had the option of saying no to the CAB due to the fact that the shelter was full (Table 2). Most shelters also accepted cats handed over by members of the public. However, CAB cats were often prioritised for animal welfare reasons. The interviewed cat shelters also stated that they collaborated with other shelters to provide backup in case one shelter was full.

Table 2

| Shelter | Is your shelter able to always take care of cats from the CAB/police? | Does your shelter also take care of cats that come from other sources than the CAB/police? | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | Yes, depending on space | No | |

| 1 | x | x | |||

| 2 | x | x | |||

| 4 | x | x | |||

| 5 | x | x | |||

| 7 | x | x | |||

| 9 | x | x | |||

| 14 | x | x | |||

Whether the cat shelters always accept the County Administrative Board’s (CAB’s) cats, and whether they also accept cats from others than the CAB/police.

3.5 The cat shelters’ view on the collaboration between the CABs and the police

Outside office hours, the police have the full mandate and responsibility to make decisions about homeless and neglected cats in accordance with the animal welfare legislation. However, cat shelters have identified issues with the divided responsibility between authorities. They found it extremely difficult to persuade the police to make decisions about seizing cats. They found that the police would refer them to the CAB, which could be unavailable for several days, for example during long holidays such as Christmas and Midsummer. Since these decisions are only requested in the most urgent cases, the shelters stressed that the lack of action by the police (and the CAB’s absence) can cause unnecessary suffering for the cats.

4 Discussion

This study aimed to investigate collaboration between CABs and private cat shelters in Sweden, and how staff at the cat shelters perceived this collaboration. It should be noted that, except for CAB procurements and decisions, no further data has been collected from the CABs (e.g. no interviews have been conducted with CAB staff).

4.1 The presence of contracts between CABs and cat shelters

Although most CABs (17/21) had contracts with cat shelters, we found substantial variations in the requirements they posed in these contracts, despite the same legislation. This variation concerned the level of detail, the financial compensation, the lead time required from the cat shelters and how profoundly the CABs could influence the staffing situation at the cat shelters.

Four CABs had no contracts with any cat shelters. In two of these counties, the CABs stated that they procured shelters directly when needed. The routines of the remaining two counties are unknown, though one commented that they received no bids when they attempted the latest procurement. Homeless or neglected cats are often in poor health and severely stressed, and are often frightened of humans (Crawford et al., 2019; Marston and Bennett, 2009). Catching and transporting them causes further stress, and in cases where large counties have only one procured shelter or no procured shelter at all, transport times may be very long. This poses a severe welfare risk to these cats.

The shelters had different perceptions of the requirements imposed by the CABs. Generally, the requirements relating to the competence and professional handling of cats were well accepted. However, cat shelters would like rehoming to be given greater focus, euthanasia decisions to be made less frequently, and financial refunds to be fair and just.

4.2 A feeling of being used

There were only a few cases in which cat shelters viewed their collaboration with the CAB as highly functional. Instead, many of the shelters felt that they were being used by the CABs. A striking detail was the low and highly variable financial compensation that the CABs provide to cat shelters. This clearly does not cover the fuel cost for driving to the locations where cats are captured, nor does it cover the hours spent on capturing, caring for the cats, or documenting the cat information requested by the CABs. Cat shelters were also expected to be available 24/7, both by the CABs and the police. All of this adds up to what can only be described as a quite cynical way of using the cat shelters to fulfil a legal mandate that is the authorities’ own responsibility.

Sweden is not the only country where cat shelters are partly replacing the work of governments or local authorities (Irvine, 2015). The cat shelters involved in this study were aware of the limited resources allocated by politicians to the CABs’ animal welfare work. Seizing animals is time-consuming and costly for the CABs. For example, between 1 June and 31 December 2018, the cost of seizing animals in Sweden was approximately 1 million EUR (Ds 2019:21, 2019), and the number of cases involving the seizure of cats and dogs is increasing every year (SBA, 2025). Statistics from the Swedish Board of Agriculture clearly show that the CABs are unable to fulfil their tasks (SBA, 2025). Therefore, it is understandable that the CABs must prioritise and keep costs as low as possible, but this raises questions about fairness to the cat shelters. The cat shelters in this study, as well as in others, also have financial, staff and time constraints (Kim, 2018).

4.3 Cat shelter staff situation

In general, the CAB’s requirements for sufficient competent shelter staff were well accepted by cat shelters. This requirement also seems highly valid. However, the CABs’ far-reaching requirements to control and interfere with the cat shelter staff situation seem invalid. In as many as twelve out of 17 CABs with written contracts, the CABs reserved the right to force cat shelters to replace staff. This was either because the CAB thought the staff were not competent enough, or because they experienced difficulties collaborating with the staff. Three CABs went even further and reserved the right to agree, in writing, on any changes of staffing at the shelters before these changes could take place. It is questionable whether these kinds of intrusive contractual requirements are ethically or legally acceptable.

Some shelters in this study mentioned that having a contract with the CAB had a detrimental effect on their working environment. Staff are constantly prepared to assist the CAB, work unpaid and sometimes end up in dangerous situations when retrieving cats from hostile environments. When the CABs are at risk of ending up in hostile situations, they have the option of requesting assistance from the police (SFS 2018:1192, 2018), an option that the cat shelters lack. Hence, one could argue that the CABs, together with the cat shelters, need to review the routines for collecting cats to ensure everyone’s safety.

Previous studies have shown that cat shelter staff and volunteers are at risk of suffering from compassion fatigue, primarily due to frequent exposure to the euthanasia of animals, which are sometimes healthy (Andrukonis and Protopopova, 2020; Jacobs and Reese, 2021; Cotterell et al., 2025). Not being able to influence the decision to euthanise a cat is likely to be a major source of stress for shelter staff (Andrukonis and Protopopova, 2020). This is a situation that arises when the CAB is responsible for the decision.

4.4 Different underlying goals

This study revealed that the underlying motivations of the cat shelters and the official missions of the CABs deviated, and that the CABs exploited this discrepancy. The main motivation for cat shelters to cooperate with CABs was to save homeless or neglected cats. CABs have a legal responsibility to enforce legislation and ensure that cat owners comply. If they do not, the CABs must take action. The cat shelters clearly perceived that the CABs focussed on abused owned cats rather than the vastly larger number of homeless cats. There may be various reasons for this discrepancy. One practical reason is that, under the Animal Welfare Act, when a cat is seized from a known owner, the CAB has the right to charge the owner for the costs incurred in housing, treating and caring for the cat during its stay at the shelter. Another reason may be the way society views cats, which may differ depending on the cat in question. A cat’s legal status can be affected by values based on its usefulness at a given point in time (Riley, 2019).

4.5 The challenge with public procurement

It is estimated that there are 60–100 cat shelters in Sweden (Rädda Katten, 2025). Of these, only a few have contracts with the CABs. Public procurement can be a daunting process due to the overwhelming administrative requirements, especially for small suppliers/organisations (Loader, 2011). Small suppliers are also often at a disadvantage in this process because low prices are often the primary goal of the procurer. This is reflected in this study, where cat shelters did not receive full cost recovery for their services, and could explain why not all CABs had contracts with cat shelters. In literature concerning public procurement, two approaches to the relationship between purchasers and suppliers are described (Loader, 2011). The “traditional arm’s-length approach” is characterised by an adversarial relationship, where price is a dominant factor. In contrast, the “close cooperative relationship” promotes partnership and trust, with cost, value and quality all being important factors in the procurement decision. One hypothesis is that the cooperation between the CABs and the cat shelters would benefit from procurements based on cooperative relationships, as the cases of homeless cats are often complex and dependent on a close cooperation between the authority and the cat shelter.

Public procurement can be challenging for cat shelters. Hence, they probably need more support throughout the process. In general, education relating to public procurement is often needed (Anguelov and Brunjes, 2023). CAB has often a team of public procurement specialists who can provide guidance on how to draft contracts that are favourable to their cause. It is unrealistic for cat shelters to employ such specialists themselves. However, many cat shelters are affiliated with larger animal welfare NGOs that could provide legal and practical advice during procurement negotiations. These contracts could then serve as templates, enabling even unorganised cat shelters to benefit from negotiations with CABs. Consequently, cat shelters could operate more efficiently, which would help to alleviate the issue of homeless cats.

4.6 Legislation and management strategies

In the interviews, cat shelters often raised the issue of cat owners’ responsibilities. There is no doubt that the situation with homeless cats is worsened by cat owners not castrating or otherwise controlling the reproduction, not ID-marking and generally not caring for their cats (SOU 2011:75). Today, all of these aspects are included in Swedish legislation to prevent poor welfare. However, throughout the interviews, the issue of how the legislation concerning cats should be interpreted and enforced has consistently come up. The shelters’ representatives expressed their frustration with the CABs’ overly cautious interpretation of the regulations and the fact that homeless cats were not receiving the necessary assistance.

The literature presents and evaluates different ways of managing homeless cats, including regulatory solutions, despite if the cats’ homelessness is considered a problem for ecosystems, the spread of disease, or for their own welfare (Deak et al., 2019; Natoli et al., 2019; Lepczyk et al., 2022; Ramírez Riveros and González-Lagos, 2024). Nevertheless, there is no known effective method to solve the issue of homeless cats (Hurley and Levy, 2022). Therefore, there is no best practice or validated action plan to adhere to. Additionally, the Swedish Animal Welfare Act clearly states that the CABs are responsible for seizing homeless cats, as these cats are considered to be suffering per se according to the Act (Prop. 2017/18:147). To our knowledge, this legal approach is unusual. In Denmark, for example, a neighbouring country of Sweden, animal welfare legislation does not oblige the authorities to take action if a cat is homeless (Sandøe et al., 2019). Instead, they rely on various NGOs. According to Sandøe et al. (2019), Danish homeless cats that are unsocialised can be euthanised or caught, neutered and released, but if they are socialised, they may be adopted by private persons. Danish cat shelters may receive some funding from municipalities, but this is not always the case; instead, the NGOs or the public pay. The situation in Norway is similar to that in Denmark; however, the animal welfare act contains a “duty to help” rule: if anyone finds an animal in need of help, they must take action. If a homeless cat requires healthcare, the Norwegian Food Safety Authority should be contacted (LOV-2009-06-19-97, 2021). However, according to the legislation, euthanasia appears to be the most common form of action, and this is also funded by the Norwegian Food Safety Authority (Matillsynet, 2014).

Sweden generally relies heavily on legislation and associated control systems to ensure the maintenance and improvement of animal welfare (Immink et al., 2010). All cats in Sweden should have an owner who cares for them and complies with the animal welfare legislation (SOU 2011:75). Consequently, the use of TNR colonies (which are few in Sweden) is being questioned, as it is difficult to fulfil the minimum animal welfare requirements in these colonies (SOU 2011:75). Though scientific information is scarce, there is plenty of practical knowledge regarding the cats’ sensitivity to temperatures below 0°C. Griffin et al. (2020) highlight the problem of ear tipping in feral cats due to frostbitten ears in cold climates. Therefore, TNR colonies may imply poor welfare, especially during the winter months. At the same time, the welfare of unsocialised adult cats is compromised if they are confined to shelters (Kessler and Turner, 1999). The CAB’s decision to euthanise these cats may therefore be a way of avoiding further suffering. Denmark appears to adopt a similar approach, with unsocialised cats being primarily captured by NGOs operating under agreements with municipalities (Thuesen et al., 2022). These cats are often euthanised due to the country’s strict regulations governing the release of cats (Nielsen et al., 2022). Consequently, only a limited number of unsocialised cats in Denmark can be included in TNR programmes (Thuesen et al., 2022). However, this study found that Swedish shelters believed that CAB euthanasia decisions were often more about saving money than saving homeless cats, socialised or not.

Although cats are strongly protected by Swedish animal welfare legislation in theory, there are contradictions in other legislation. For instance, the Swedish Lost Property Act (SFS 1938:121, 1938) treats cats as objects to a greater extent than dogs. Under this law, a homeless cat becomes the property of the finder if no owner comes forward within three months. A dog, on the other hand, becomes the property of the state after ten days if no owner is found. This suggests that cats are less valuable and have a lower status than dogs. It should be noted that there are no homeless dogs in Sweden.

Legislation is probably not the only solution (Cotterell et al., 2025), nor is increased shelter capacity (Sandøe et al., 2019). Essentially, collaboration between legal bodies, volunteers/organisations, and politicians is likely necessary for sustainable solutions.

4.7 Recommendations for the future

Based on this study, which focussed on the collaboration between competent governmental authorities and cat shelters in relation to the animal welfare legislation, we make the following recommendations to facilitate future work aimed at improving the situation of homeless cats in Sweden:

-

Determination from politicians to solve the problem of homeless cats in a sustainable way. Examples of how this could be achieved include a) consistently recognising that cats have the same value as dogs in political decisions and legislation, b) sending signals to the relevant authorities and the public that cat welfare is important and should be prioritised, c) increasing the resources given to the CABs so that they are better equipped to enforce legislation and deal with the issue of homeless and neglected cats, d) offering government funding to cat shelters, and e) allocating government research funding to studies on the management strategies and welfare of homeless cats (socialised or not) in Sweden.

-

The CABs should develop a common understanding on how to deal with homeless cats, and evaluate different approaches depending on the health status and the degree of socialisation of the cats in terms of both economy and animal welfare.

-

The Swedish Board of Agriculture and the CABs should engage in dialogue to establish reasonable requirements for procured cat shelters and ensure consistency across the country.

-

Cat shelters should receive support in negotiating public procurements.

-

It should be ensured that procured cat shelters are located throughout the country to avoid long transport distances for cats.

-

Increase the status of cats, especially homeless ones.

Some of the cat shelters involved in this study found that collaborating with the CABs worked rather well. Further analysis of this collaboration could provide insight into the success factors for this kind of collaboration.

5 Conclusion

This study reveals that cat shelters in Sweden are systematically exploited by the CABs to carry out the government’s work without receiving full financial compensation. The cat shelters are aware that they are being used by the CABs. However, they understand that the CABs have limited resources. The shelters are also willing to accept an early ownership of homeless cats to prepare them for adoption and thus prevent possible euthanasia decisions taken by the CAB.

Whilst the public procurement process for contracting cat shelters may benefit the CABs, it does not benefit the shelters to the same extent, as it is quite complex and administratively burdensome. Consequently, few cat shelters are procured, and homeless cats are sometimes transported long distances, despite being severely stressed, injured or sick.

The large number of homeless cats in Sweden shows that the current system is ineffective. All relevant actors, including cat owners and the authorities, must take responsibility for their obligations.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The requirement of ethical approval was waived by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority for the studies involving humans. The Ethical Review Authority assessed that this study did not need any ethical approval (ref 2023-04877-01). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board also waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin. The Ethical Review Authority assessed that this study did not need any ethical approval, hence, no demand for written informed consent was needed. However, the interviewed cat shelters were informed by email what the aim of the study was (when they were asked if they wanted to participate), and also informed before the interview started what the aim was, how their input would be handled.

Author contributions

FL: Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. MK: Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Investigation. JY: Methodology, Supervision, Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the CABs in Sweden for providing the documentation about cat shelters contracts and to the cat shelters who shared their views on the handling of homeless cats.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fanim.2025.1629711/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Andrukonis A. Protopopova A. (2020). Occupational health of animal shelter employees by live release rate, shelter type, and euthanasia-related decision. Anthrozoös33, 119–131. doi: 10.1080/08927936.2020.1694316

2

Anguelov L. G. Brunjes B. M. (2023). A replication of “Contracting out: For What? With Whom? Public Admin101, 1163–1197. doi: 10.1111/padm.12921

3

Contalbrigo L. Normando S. Bassan E. Mutinelli F. (2024). The welfare of dogs and cats in the european union: A gap analysis of the current legal framework. Animals14, 2571. doi: 10.3390/ani14172571

4

Cotterell J. Rand J. Scotney R. (2025). Rethinking urban cat management—Limitations and unintended consequences of traditional cat management. Animals15, 1005. doi: 10.3390/ani15071005

5

Crawford H. M. Calver M. C. Fleming P. A. (2019). A Case of Letting the Cat out of The Bag—Why Trap-Neuter-Return Is Not an Ethical Solution for Stray Cat (Felis catus) Management. Animals9, 171. doi: 10.3390/ani9040171

6

Deak B. P. Ostendorf B. Taggart D. A. Peacock D. E. Bardsley D. K. (2019). The significance of social perceptions in implementing successful feral cat management strategies: A global review. Animals9, 617. doi: 10.3390/ani9090617

7

Ds 2019:21 (2019). Märkning och registrering av katter - ett förslag och dess konsekvenser [An governmental investigationi of the ID-tagging and registration of cats - a proposal and its consequences] (Stockholm: Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation, Swedish Government). Available online at: https://www.regeringen.se/rattsliga-dokument/departementsserien-och-promemorior/2019/09/markning-och-registrering-av-katter—ett-forslag-och-dess-konsekvenser/ (Accessed May 2023).

8

Eriksson P. Loberg J. Andersson M. (2009). A survey of cat shelters in Sweden. Anim. Welf.18, 283–288. doi: 10.1017/S0962728600000531

9

Fossati P. (2024). Spay/neuter laws as a debated approach to stabilizing the populations of dogs and cats: An overview of the European legal framework and remarks. JAAWS27, 281–293. doi: 10.1080/10888705.2022.2081807

10

George T. (2022). Semi-Structured Interview | Definition, Guide & Examples (Scribbr). Available online at: https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/semi-structured-interview/.

11

Gilhofer E. M. Windschnurer I. Troxler J. Heizmann V. (2019). Welfare of feral cats and potential influencing factors. JVEB30, 114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jveb.2018.12.012

12

Graham C. Koralesky K. E. Pearl D. L. Niel L. (2024). Understanding kitten fostering and socialisation practices using mixed methods. Anim. Welf.33, e52. doi: 10.1017/awf.2024.45

13

Grieco V. Crepaldi P. Giudice C. Roccabianca P. Sironi G. Brambilla E. et al . (2021). Causes of Death in Stray cat colonies of milan: A five-year report. Animals11, 3308. doi: 10.3390/ani11113308

14

Griffin B. Bohling M. W. Brestle K. (2020). “Tattoo and ear-tipping techniques for identification of surgically sterilized dogs and cats,” in The High-Quality, High-Volume Spay and Neuter and Other Shelter Surgeries. Ed. WhiteS. (Hoboken, White John Wiley & Sons), 325–338.

15

Handler H. (2015). Strategic Public Procurement: An overview. Policy Paper no 28 (WWWforEurope: Welfare, Wealth and Work for Europe). doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2695546

16

Hurley K. F. Levy J. K. (2022). Rethinking the animal shelter’s role in free-roaming cat management. Front. Vet. Sci.9. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.847081

17

Immink V. M. Ingenbleek P. Keeling L. (2010). Report on development of policy instruments towards the Action Plan on Animal Welfare. SWOT-analysis of instruments following brainstorm meetings and literature. EconWelfare report, deliverable 3.1.

18

Irvine L. (2015). “Animal sheltering,” in The Oxford Handbook of Animal Studies. Ed. KalofL. (Oxford Academic), 98–112. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199927142.013.12

19

Jacobs J. Reese L. A. (2021). Compassion fatigue among animal shelter volunteers: examining personal and organizational risk factors. Anthrozoös34, 803–821. doi: 10.1080/08927936.2021.1926719

20

Kessler M. R. Turner D. C. (1999). Socialization and stress in cats (Felis silvestris catus) housed singly and in groups in animal shelters. Anim. Welf.8, 15–26. doi: 10.1017/S0962728600021163

21

Kim J. (2018). Social finance funding model for animal shelter programs: public–private partnerships using social impact bonds. Soc Anim.26, 259–276. doi: 10.1163/15685306-12341521

22

Lepczyk C. A. Duffy D. C. Bird D. M. Calver M. Cherkassky D. Cherkassky L. et al . (2022). A science-based policy for managing free-roaming cats. Biol. Invasions.24, 3693–3701. doi: 10.1007/s10530-022-02888-2

23

Loader K. (2011). Are public sector procurement models and practices hindering small and medium suppliers? Public Money. Manage.31, 287–294. doi: 10.1080/09540962.2011.586242

24

LOV-2009-06-19-97 (2021). Lov om dyrevelferd. Landbruks- og matdepartementet. Ministry of Agriculture and Food (Oslo, Norway).

25

Lundmark Hedman F. Ewerlöf I. R. Frössling J. Berg C. (2025). Official and private animal welfare inspectors’ perception of their own on-site inspections. Front. Vet. Sci.12. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2025.1575471

26

Marston L. C. Bennett P. C. (2009). Admissions of cats to animal welfare shelters in melbourne, Australia. JAAWS12, 189–213. doi: 10.1080/10888700902955948

27

Matillsynet (2014). Tilsynsveileder katt. Utarbeidet for TA av Prosjekt dyrevelferd, august 2014. Available online at: https://www.mattilsynet.no/dyr/kjaeledyr/katt/tilsynsveileder-for-katt (Accessed May 14, 2025).

28

Natoli E. Ziegler N. Dufau A. Pinto Teixeira M. (2019). Unowned free-roaming domestic cats: reflection of animal welfare and ethical aspects in animal laws in six european countries. J. Appl. Anim. Ethics. Res.2, 38–56. doi: 10.1163/25889567-12340017

29

Nielsen H. B. Jensen H. A. Meilby H. Nielsen S. S. Sandøe P. (2022). Estimating the population of unowned free-ranging domestic cats in Denmark using a combination of questionnaires and GPS tracking. Animals12, 920. doi: 10.3390/ani12070920

30

Nielsen S. S. Thuesen I. S. Mejer H. Agerholm J. S. Nielsen S. T. Jokelainen P. et al . (2023). Assessing welfare risks in unowned unsocialised domestic cats in Denmark based on associations with low body condition score. Acta Vet. Scand.65, 1. doi: 10.1186/s13028-023-00665-2

31

Palmas P. Gouyet R. Oedin M. Millon A. Cassan J.-J. Kowi J. et al . (2020). Rapid recolonisation of feral cats following intensive culling in a semi-isolated context. NeoBiota63, 177–200. doi: 10.3897/neobiota.63.58005

32

Prop. 2017/18:147 Ny djurskyddslag. Regeringens proposition. Näringsdepartementet [Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation], Regeringskansliet [Swedish Government]. Available online at: https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/proposition/ny-djurskyddslag_h503147/html/ (Accessed May 14, 2025).

33

Rädda Katten (2025). Hur många katthem finns det i Sverige? Available online at: https://raddakatten.se/hur-manga-katthem-finns-det-i-sverige/:~:text=Det%20exakta%20antalet%20kan%20vara%20sv%C3%A5rt%20att%20fastst%C3%A4lla%2C,fokuserar%20p%C3%A5%20katter%20%C3%B6ver%20hela%20landet.%20Dessa%20inkluderar%3A (Accessed May 12, 2025).

34

Ramírez Riveros D. González-Lagos C. (2024). Community engagement and the effectiveness of free-roaming cat control techniques: A systematic review. Animals14, 492. doi: 10.3390/ani14030492

35

Riley S. (2019). The changing legal status of cats in Australia: from friend of the settlers, to enemy of the rabbit, and now a threat to biodiversity and biosecurity risk. Front. Vet. Sci.5. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2018.00342

36

Robertson S. A. (2008). A review of feral cat control. J. Feline. Med. Surg.10, 366–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2007.08.003

37

Sandøe P. Corr S. Palmer C. (2015). “Chapter 13. Unwanted and unowned companion animals,” in : companion animal ethics (John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, UK), 201–216.

38

Sandøe P. Jensen J. B. H. Jensen F. Nielsen S. S. (2019). Shelters reflect but cannot solve underlying problems with relinquished and stray animals - A retrospective study of dogs and cats entering and leaving shelters in Denmark from 2004 to 2017. Anim. (Basel).9, 765. doi: 10.3390/ani9100765

39

SBA (2025). Nationell djurskyddsrapport 2024 - En redovisning av kontrollmyndigheternas arbete (Jönköping, Sweden: Swedish Board of Agriculture). Available online at: https://www2.jordbruksverket.se/download/18.d2af131196a047ce9911e3a/1746715170602/ovr737.pdf (Accessed May 14, 2025).

40

Scott K. C. Levy J. K. Gorman S. P. Newell S. M. (2002). Body condition of feral cats and the effect of neutering. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci.5, 203–213. doi: 10.1207/S15327604JAWS0503_04

41

SFS 1938:121 . (1938). Lag om hittegods. The Ministry of Justice (Swedish Government).

42

SFS 2007:1150 . (2007). Lag om tillsyn över hundar och katter. Ministry of Rural Affairs and Infrastructure (Swedish Government).

43

SFS 2016:1145 . (2016). Lag om offentlig upphandling. Ministry of Finance (Swedish Government).

44

SFS 2018:1192 . (2018). Djurskyddslag. Ministry of rural Affairs and Infrastructure (Swedish Government).

45

Short J. Turner B. Risbey D. A. (2002). Control of feral cats for nature conservation. III. Trapping. Wildl. Res.29, 475–487. doi: 10.1071/WR02015

46

SJVFS 2020:8 . (2020). Jordbruksverkets föreskrifter och allmänna råd om hållande av hundar och katter [The Swedish Board of Agriculture’s regulations and general advice on the keeping of dogs and cats] (Jönköping. Sweden: Swedish Board of Agriculture).

47

Slater M. R. (2007). “The welfare of feral cats,” in The Welfare of Cats. Ed. RochlitzI. (Springer Dordrecht), 141–175. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-3227-1_6

48

SOU 2011:75 . Ny djurskyddslag. Ministry of Rural Affairs (Swedish Government). Available online at: https://www.regeringen.se/rattsliga-dokument/statens-offentliga-utredningar/2011/11/sou-201175/ (Accessed May 12, 2025).

49

Sparkes A. H. Bessant C. Cope K. Ellis S. L. H. Finka L. Halls V. et al . (2013). ISFM guidelines on population management and welfare of unowned domestic cats (Felis catus). J. Feline. Med. Surg.15, 811–817. doi: 10.1177/1098612X13500431

50

Spehar D. D. Wolf P. J. (2019). Back to school: an updated evaluation of the effectiveness of a long-term trap-neuter-return program on a university’s free-roaming cat population. Animals9, 768. doi: 10.3390/ani9100768

51

Tabor R. (1981). “General biology of feral cats,” In the proceedings of the symposium "Ecology and Control of Feral Cats: Universities Federation for Animal Welfare", held at the Royal Holloway College, University of London, London, England, September 23-24, (1980.). (Potters Bar, Hertfordshire). pp. 5–11.

52

Thuesen I. S. Agerholm J. S. Mejer H. Nielsen S. S. Sandøe P. (2022). How serious are health-related welfare problems in unowned unsocialised domestic cats? A study from Denmark based on 598 necropsies. Animals12, 662. doi: 10.3390/ani12050662

53

Wolf P. J. Hamilton F. (2022). Managing free-roaming cats in U.S. cities: An object lesson in public policy and citizen action. J. Urban. Aff.44, 221–242. doi: 10.1080/07352166.2020.1742577

Summary

Keywords

cat shelter, County Administrative Board, homeless cats, contract, public procurement, stray cats

Citation

Lundmark Hedman F, Karlsson M and Yngvesson J (2025) Homeless cats, a societal problem - an analysis of the collaboration between cat shelters and the competent authorities in Sweden. Front. Anim. Sci. 6:1629711. doi: 10.3389/fanim.2025.1629711

Received

16 May 2025

Accepted

01 July 2025

Published

17 July 2025

Volume

6 - 2025

Edited by

Ruth C. Newberry, Norwegian University of Life Sciences, Norway

Reviewed by

Alda Natale, Experimental Zooprophylactic Institute of the Venezie (IZSVe), Italy

Peter Joseph Wolf, Best Friends Animal Society, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Lundmark Hedman, Karlsson and Yngvesson.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Frida Lundmark Hedman, frida.lundmark@slu.se

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.