Abstract

This study investigates the genomic architecture of two Alpine dairy goat breeds, Camosciata delle Alpi (CAM) and Saanen (SAA), managed in ten herds located in Lombardy, northern Italy. Through medium-density SNP genotyping (GGP Goat 70K), we assessed population structure, genetic diversity, and Runs of Homozygosity (ROH) to evaluate the effects of breeding practices and herd-level management strategies on genetic variation. A total of 1,283 animals (CAM: 977; SAA: 306) were analyzed. Principal Component Analysis and ADMIXTURE results confirmed a clear genetic separation between the two breeds, with substantial intra-breed variation linked to herd-specific selection histories. ROH-based inbreeding coefficients (FROH) were moderate overall (mean FROH: 0.060 in CAM and 0.041 in SAA), though some herds displayed elevated values, suggestive of recent inbreeding or reduced gene flow. ROH analysis revealed a predominance of short segments (<2 Mb), consistent with background or historical inbreeding, and only a limited presence of long ROH (>8 Mb). Shared ROH islands on chromosomes 8, 12, and 14 were detected across both breeds and most herds, encompassing functionally relevant genes involved in thermoregulation (AQP3), fertility (RNF17), metabolic balance (ATP12A), and stress resilience. Notably, VPS13B was consistently detected in 9 out of 10 herds and in both breeds, and is known for its involvement in female fertility and skeletal traits in ruminants. Breed-specific ROH islands revealed further candidate genes: SDC1, ARHGEF17, and CAPNS2 in CAM, and DNAJA1, ATP6V0D1, UBAP1, and ZDHHC1 in SAA, related to milk production, mastitis resistance, heat stress response, and skeletal development. These findings highlight the value of integrating genomic tools into herd management. Genomic surveillance can guide sustainable selection strategies, mitigate inbreeding risks, and support the long-term genetic improvement of Alpine goat populations under diverse production systems.

1 Introduction

Conservation of biodiversity is a critical goal in the management of livestock genetic resources. Italy serves as an exemplary model due to its rich biodiversity among domesticated species, fostered by its diverse historical, environmental, climatic, and agricultural traditions (Senczuk et al., 2020). Goats, in particular, represent a significant component of this biodiversity, with over 30 indigenous breeds thriving in varied climates and farming systems, many of which operate under low-input agricultural practices (Cortellari et al., 2021a).

The Alpine goat breeds, extensively farmed in northern Italy, particularly in the Alpine regions, are subject to a range of farming practices, from intensive indoor systems to extensive grazing. These breeds are highly valued for their dairy production, known for both quantity and quality of their milk. The Camosciata delle Alpi (CAM) is a dairy goat breed originating from the Alpine regions of Italy, Switzerland, France, and Austria. Well-adapted to mountainous environments, it is characterized by its resilience, strong physique, and excellent milk production (Pegolo et al., 2025). The milk of the CAM breed is rich in fat and protein, making it particularly suitable for high-quality cheese production, a key factor in its economic relevance (Agradi et al., 2022). Similarly, the Saanen (SAA) breed, originally from Switzerland, is recognized as one of the world’s most productive dairy goats. It is renowned for its high milk yield, adaptability to various climates, and widespread use in commercial dairy production (McSweeney and McNamara, 2022). However, in recent years, crossbreeding with Dutch white genetics – intended to further enhance milk production – has introduced significant challenges. The introduction of Dutch genetics into Italian Saanen populations is supported by practical evidence from breeders. Many Italian breeders report to breed their flocks using semen from Dutch Saanen lines to improve milk yield and other productive traits. Therefore, assessing the genetic diversity of these breeds is crucial to understand the impact of such crossbreeding practices on their resilience, productivity, and overall health characteristics.

In Italy, the Associazione Nazionale della Pastorizia (AssoNaPa, 2025) is the breed society responsible for genetic programs in goats and sheep, in accordance with the EU “Animal Breeding Regulation” (Regulation (EU) 2016/1012, 2016), including the management of herdbooks for the Saanen and Camosciata delle Alpi goat breeds. In Lombardy, intensive (and some semi-intensive) indoor systems are common in lowland and valley areas, while semi-extensive and extensive modalities persist in upland and marginal terrain, producing differing management-driven selection pressures across herds. National selection tools, such as estimated breeding values (EBVs), and the gradual introduction of genomic monitoring, are available through AssoNaPa. While AssoNaPa routinely estimates EBVs for animals recorded in the herdbook with genealogical information, the reliability of pedigree data provided by farmers (AssoNaPa, 2025), a fundamental input for genetic evaluation, is often incomplete or inaccurate. In many herds, in fact, a substantial proportion of animals lack fully recorded or correct genealogical information, particularly when natural mating occurs in groups with multiple bucks. As a result, selection decisions are often based primarily on farmer-recorded phenotypes, rather than on EBVs, which limits the efficiency of genetic improvement programs at both national and regional levels. In parallel, national monitoring and conservation programmes remain essential to track genomic diversity and safeguard smaller local breeds. These nationwide efforts provide context for interpreting herd-level genetic variability and inbreeding.

Inbreeding, in fact is a key aspect of genetic diversity and a major concern in livestock breeding, as it increases homozygosity and may reduce fitness. The inbreeding coefficient (F), traditionally estimated from pedigree data, is now often derived from Runs of Homozygosity (ROH), which provide a more accurate measure of autozygosity (Szpiech et al., 2013; Peripolli et al., 2017). ROH are continuous homozygous segments within the genome (Gibson et al., 2006) that arise through inbreeding, genetic drift, or selection, and their length distribution offers insights into demographic history: short segments typically reflect ancient inbreeding, whereas long ones indicate more recent events (Keller et al., 2011). Thus, ROH analyses provide information on both the genetic health of populations and on regions of the genome shaped by selection (Purfield et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2013; Dixit et al., 2020). Beyond individual-level inbreeding estimates, the distribution of ROH across a population can highlight shared regions of homozygosity, known as ROH islands (Nothnagel et al., 2010). These genomic hotspots, where positive selection has increased the frequency of specific haplotypes, have been used to identify selection signatures in several livestock species (Zhang et al., 2015; Bertolini et al., 2018; Grilz-Seger et al., 2018; Mastrangelo et al., 2018; Peripolli et al., 2018; Xie et al., 2019). While such processes can favor beneficial mutations, they may also increase deleterious variants through genetic hitchhiking (Szpiech et al., 2013; Makino et al., 2018). Assessing ROH patterns in Alpine (CAM and SAA) goats can therefore provide valuable insights into how breeding practices and management strategies have shaped their genetic structure as already done in other species (Punturiero et al., 2023).

The aims of this study were: i) to characterize ROH patterns in both Alpine goats to understand how different breeding and management practices impact genetic diversity, and to identify genomic regions under putative selection; ii) to assess the impact of recent crossbreeding and reproductive strategies on the genomic integrity and structure of these populations. Details will then be reported at the individual farm level, providing both a general overview of the two breeds and highlighting the specific selective choice of each farm.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Ethics statement

All procedures adhered to European and Italian legislation (2010/63/EU Directive and Legislative Decree No. 26/2014) and received approval from the Animal Welfare Body of the Università degli Studi di Milano (OPBA) as well as the Italian Ministry of Health (protocol number OPBA_68_2023).

2.2 Animal sampling, DNA extraction, and genotyping

This research was part of the goals of the CapraGEN project (Application of GENomics in Dairy Goat Breeding), funded by the Lombardy Region, which aims to apply advanced genomic tools to improve the understanding of dairy goat genetic resources, with particular attention to both intra- and inter-herd dynamics. Through comprehensive genomic analyses, the project aimed to investigate the genetic consequences of current breeding practices and to identify genomic regions that may have been shaped by selection for productive and adaptive traits. The findings provide essential insights to support evidence-based strategies for the sustainable breeding, genetic conservation, and long-term viability of Alpine goat populations in Lombardy.

A total of 1,283 Alpine goats (CAM = 977; SAA = 306, Table 1) were sampled from ten distinct farms within the Lombardy region of Italy using ear Tissue Sampling Unit (TSU). The Quick-DNA™ Miniprep kit (Zymo Research) was used to extract DNA from the ear tissue following the provided protocol. All collected samples were cataloged in a project-structured database and stored at the University of Milan tissue repository, the Animal Bio-Arkive (Longeri et al., 2021).

Table 1

| Herd | Herd’s location (Province) | N. goats CAM | N. goats SAA | Min and max n. lactations per goat | Production focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Herd_01 | Pavia | 83 | 1-6 | Milk/cheese | |

| Herd_02 | Bergamo | 144 | 1-8 | Milk/cheese | |

| Herd_03 | Brescia | 141 | 1-2 | Milk | |

| Herd_04 | Como | 126 | 1-7 | Milk/cheese | |

| Herd_05 | Milano | 29 | 1 | Milk/cheese | |

| Herd_06 | Lodi | 379 | 1-4 | Milk/cheese | |

| Herd_07 | Brescia | 75 | 1-5 | Milk | |

| Herd_08 | Bergamo | 121 | 1-8 | Milk | |

| Herd_09 | Brescia | 135 | 1-6 | Milky/cheese | |

| Herd_10 | Milano | 50 | 1-7 | Milk/cheese | |

| Total N. | 977 | 306 |

Number of individuals sampled per breed and herd, all managed under intensive systems.

All animals included in this study were genotyped using the Neogen GGP Goat 70K chip. All samples had a call rate exceeding 98% and only SNPs located on the 29 autosomes with MAF ≥ 1%, with ≥ 98% genotyping rate, with no duplicate positions, as annotated in the ARS1.2 Goat genome assembly, were retained for analysis (final markers dataset: 64,273 SNPs).

2.3 Statistical analysis

2.3.1 Genetic variability at breed and farm levels

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed separately for the two breeds to assess genetic diversity among animals from the ten herds. The analysis was conducted using the SNP & Variation Suite (SVS) v8.9 software (Golden Helix Inc., Bozeman, MT, USA). The graphical representation of the PCA results was generated using the ‘ggplot2’ R package (Wilkinson, 2011). The expected and observed heterozygosity (He and Ho) were calculated using Plink v1.9, to provide a complementary measure of genetic diversity within and between the studied breeds.

To further investigate the genetic structure of the studied populations, an admixture analysis was performed using ADMIXTURE v1.3 (Alexander et al., 2009). A random subset of 20 samples per group was selected using R-Studio software, applying a fixed random seed to ensure reproducibility of the procedure. Two hundred and twenty samples were then analyzed to ensure balanced representation across groups and adequate within-farm diversity, while maintaining computational efficiency. This sampling design provides robust estimates of population structure, as supported by previous studies (Alexander et al., 2009; Lawson et al., 2018). The number of ancestral populations (K) was inferred by running ADMIXTURE ten times for each K value, ranging from 1 to 6. For each K, the replicate with the highest log-likelihood was retained. The optimal K was then selected based on the lowest average cross-validation (CV) error across replicates, following the standard ADMIXTURE procedure. A linkage disequilibrium (LD) pruning was performed with –indep-pairwise 50 10 0.5 parameters, resulting in a final dataset of 46,397 SNPs.

2.3.2 Runs of homozygosity detection

ROH were identified for all 1,283 goats in the dataset by the “consecutive run” method from the “detectRUNS” package in R Software (Biscarini et al., 2018) using the dataset of 64,273 SNPs (no pruned). The parameters used were: (i) minimum number of 20 SNPs/ROH; (ii) a minimum length of 500,000 bp; (iii) the maximum gap of 1 Mbp between two consecutive SNPs; (iv) no missing SNPs as well as no heterozygous genotypes allowed in ROH definition. We applied stringent parameters within the consecutive method to minimize false positives (Hillestad et al., 2017). This approach, compared with sliding-window strategies, is also more conservative, particularly for short ROH, since it requires uninterrupted homozygosity and therefore provides higher confidence that detected segments represent true autozygosity (Ojeda-Marín et al., 2024).

The ROH distribution for each herd was assessed separately using five ROH length categories (<2 Mb, 2–4 Mb, 4–8 Mb, 8–16 Mb, and >16 Mb). Descriptive statistics were calculated at the individual level, including the total number of ROH, the number of ROH per individual, and the average ROH length. The ggplot2 package was used to generate Manhattan plots representing the percentage of SNPs falling within ROH, calculated by counting how often each SNP appears within a ROH across all individuals (Wickham, 2016). The identification of ROH islands was performed using the detectRUNS package, which detected peaks in the Manhattan plot where SNPs were located within ROH in more than 30% of the goats (Schiavo et al., 2021). Only ROH islands containing more than 5 SNPs were retained to avoid identifying spurious ROH islands caused by isolated high-frequency SNPs.

Gene annotation was performed using the Genome Data Viewer tool from the NCBI database, freely available online (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gdv). The obtained list of genes was then used as input in the Animal QTLdb to identify previously reported quantitative trait loci (QTLs) (Hu et al., 2013). For all genes annotated within the ROH islands, QTLs associated with traits were retrieved using the ‘Search by Associated Gene’ feature in the Cattle QTLdb (Hu et al., 2022), which links annotated genes to QTLs reported in the literature.

The STRING of Cytoscape 3.10.1 was employed to construct gene interaction networks, to identify functional associations within the candidate genes (Shannon et al., 2003).

2.3.3 Inbreeding coefficients

Genomic molecular inbreeding was assessed using two distinct coefficients: FHOM and FROH.

FHOM coefficient, which reflects the excess of the observed number of homozygous genotypes was calculated with SVS, following:

where HomOb and HomEx are the observed and expected homozygous genotypes, respectively (Wright, 1949). The FHOM coefficients were calculated at the herd level rather than at the breed level, in order to provide a more accurate picture of inbreeding which are often influenced by specific management and mating practices within each herd.

The FROH coefficient was estimated using the “detectRUNS” package in R. This coefficient represents the proportion of an individual’s genome covered by ROH. This was determined using the following formula (McQuillan et al., 2008):

where LROH is the total length of all ROHs of an individual, Laut refers to the length of the autosomal genome covered by the SNPs used in this study (2,468,379,888 bp) spanning chromosomes 1 to 29.

The correlation between FROH and FHOM was first summarized at the breed level using the coefficient of determination (R²) to provide an initial overview. Subsequently, correlations were calculated separately for each herd using both Pearson and Spearman methods. Pearson correlation was used as the primary measure, while Spearman served as a robustness check to account for potential deviations from normality or linearity in the data.

3 Results

3.1 Genetic variability at breed and herd levels

The Principal Component Analysis (PCA) plot for CAM (Figure 1A) shows a homogeneous distribution of animals across herds, with the exception of Herd_06, which exhibits high genetic variability among its goats. The PCA plots for the individual herds (Supplementary Figure S1) reveal that only Herd_02 displays a distribution of samples spanning the entire plot area. In all other herds, two or more distinct clusters are observed.

Figure 1

(a) PCA of CAM goats (PC_1 = 22.9%, PC_2 = 14.4%); (b) PCA of SAA goats (PC_1 = 21.8%, PC_2 = 13.2%); (c) PCA of CAM vs SAA goats (PC_1 = 30.8%, PC_2 = 15.6%).

The PCA plot in Figure 1B reveals three distinct clusters corresponding to the three herds farming Saanen goats. Herd_08 is clearly separated from the other two along the PC_1 axis, which accounts for 21.8% of the total genetic variability. Additionally, within each SAA herd (Supplementary Figure S1), individuals tend to cluster into multiple subgroups.

The combined PCA of the two breeds (Figure 1C) displays a breed-specific separation, characterized by a V-shaped distribution of clusters: SAA individuals are primarily aligned along the PC_1 axis, while CAM individuals show greater dispersion along PC_2.

Table 2 summarizes the average Ho and He, along with their standard deviations, for each herd within the CAM and SAA breeds. In general, both breeds exhibit similar levels of genetic diversity, with mean He values ranging narrowly around 0.396. Within the CAM breed, Ho values are relatively consistent across herds, ranging from 0.3752 (Herd_04) to 0.3831 (Herd_07), and standard deviations are low, indicating limited variation within herds. In contrast, the SAA breed shows slightly higher and more variable Ho values, particularly in Herd_08, which presents the highest mean Ho (0.3983) and the largest standard deviation (0.0329), suggesting greater intra-herd genetic variability. The observed heterozygosity in Herd_10 (0.3843) is closer to the values seen in CAM herds, while Herd_09 shows intermediate values. Overall, CAM and SAA exhibit lower observed heterozygosity compared to expected heterozygosity, which may indicate a certain degree of inbreeding within the two populations of all farms.

Table 2

| Breed | Herd | mean_Ho | sd_Ho | mean_He | sd_He |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAM | Herd_01 | 0.3783 | 0.0149 | 0.3955 | 0.0002 |

| Herd_02 | 0.3767 | 0.0153 | 0.3960 | 0.0004 | |

| Herd_03 | 0.3802 | 0.0178 | 0.3960 | 0.0002 | |

| Herd_04 | 0.3752 | 0.0177 | 0.3957 | 0.0004 | |

| Herd_05 | 0.3815 | 0.0082 | 0.3961 | 0.0002 | |

| Herd_06 | 0.3806 | 0.0166 | 0.3958 | 0.0004 | |

| Herd_07 | 0.3831 | 0.0101 | 0.3960 | 0.0001 | |

| SAA | Herd_08 | 0.3983 | 0.0329 | 0.3988 | 0.0012 |

| Herd_09 | 0.3937 | 0.014 | 0.3959 | 0.0002 | |

| Herd_10 | 0.3843 | 0.0226 | 0.3961 | 0.0001 |

Mean observed (Ho) and expected (He) heterozygosity and standard deviations (sd) both per breed and Herd.

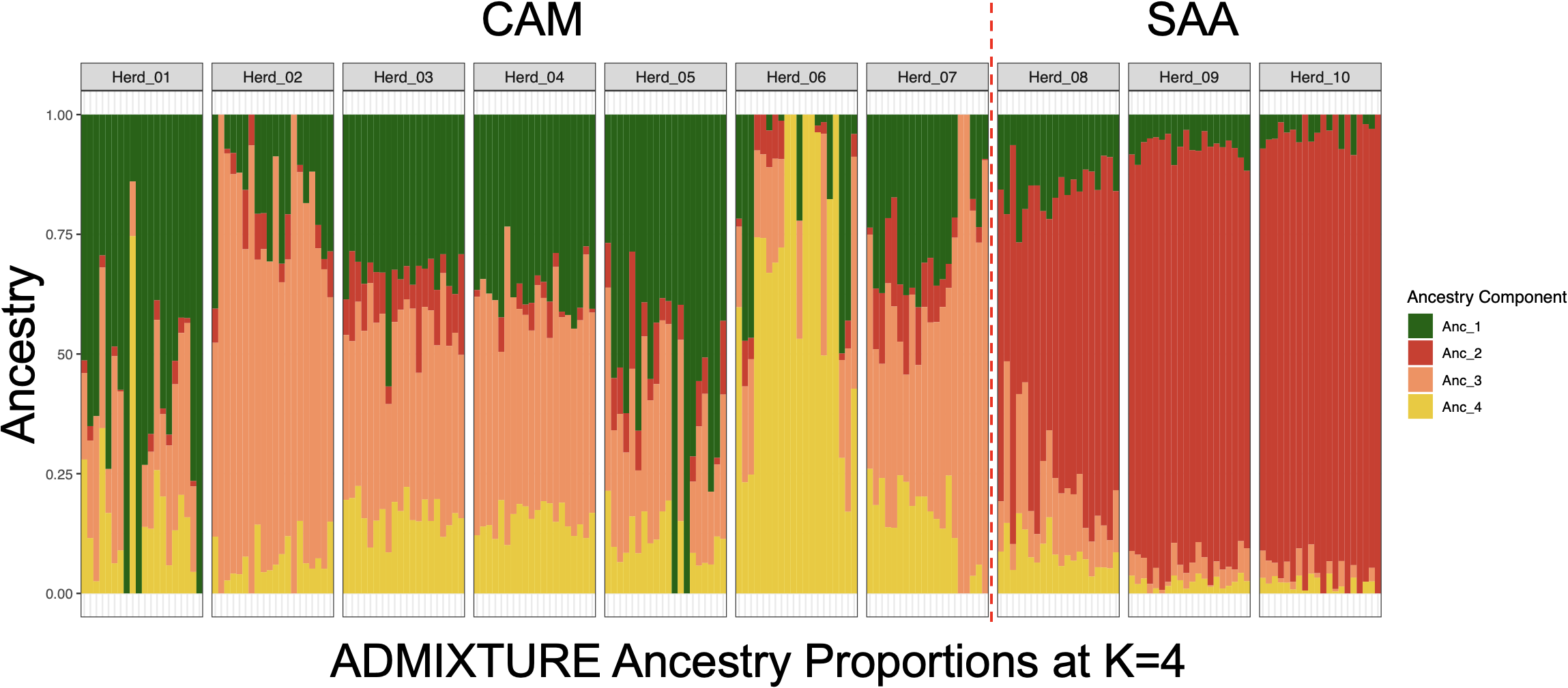

To further investigate population structure and potential admixture, the ADMIXTURE analysis was performed using K values from 2 to 7. The optimal number of clusters was determined to be K = 4, based on the lowest average cross-validation (CV) error assessed with ADMIXTURE as graphically represented in Supplementary Figure S2. Results revealed distinct ancestry patterns between the CAM and SAA breeds, as well as heterogeneity among herds within each breed (Figure 2). In the CAM herds (Herd_01 to Herd_07), ancestry proportions varied considerably across herds: Herd_01 showed a prevalent contribution of Ancestor 1 (61%), suggesting a more homogeneous genetic background in line with a specific breeding line. In contrast, Herd_02 and Herd_06 were primarily composed of Ancestor 3 (72%) and Ancestor 4 (67%), respectively. In the SAA herds the genetic background is predominantly shaped by Ancestor 2, which accounts for the majority of the estimated genome-wide ancestry in these populations. Herd_10 shows the highest contribution, with 92%, followed by Herd_09 (87%) and Herd_08 (62%).

Figure 2

Individual ancestry proportions for Alpine goats from each herd based on ADMIXTURE analysis (K = 4).

3.2 Runs of homozygosity

A total of 113,248 ROHs were identified across the 1,283 animals analyzed. Table 3 summarizes the distribution of these ROHs within each herd. The number of ROHs detected was highly correlated with herd size (97.8%). On average, each individual across all herds had 82 ± 38 ROHs (CAM and SAA). The fewest ROHs were found in a goat from Herd_08 CAM, with just 12 ROHs, whereas the highest number, 417 ROHs, was observed in a goat from Herd_04. Herd_04 not only exhibited the highest number of ROHs per individual on average (107.7 ± 36.2) but it also has the highest percentage of the genome covered by ROHs (7.8%). The number of SNPs contained in a ROH varies across herds with a maximum of 741 SNPs registered in an animal from Herd_06.

Table 3

| Breed | Herd | Total ROH | SNP n. | Average ROH number | Average ROH length (Mbp) | Mean coverage1 (%)2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Range | Mean ± SD | Range | |||||

| CAM | Herd_01 | 8,292 | 20 – 293 | 99.90 ± 36.17 | 55 – 388 | 1.63 ± 0.11 | 0.5 – 10.14 | 163,183,009 (6.6%) |

| Herd_02 | 14,150 | 20 – 499 | 98.26 ± 29.03 | 58 – 286 | 1.85 ± 0.14 | 0.5 – 18.08 | 181,393,933 (7.3%) | |

| Herd_03 | 13,287 | 20 – 302 | 94.23 ± 37.01 | 29 – 384 | 1.67 ± 0.12 | 0.5 – 11.07 | 158,296,006 (6.4%) | |

| Herd_04 | 13,565 | 20 – 445 | 107.66 ± 36.22 | 69 – 417 | 1.79 ± 0.14 | 0.5 – 17.36 | 193,527,100 (7.8%) | |

| Herd_05 | 2,592 | 20 – 309 | 89.38 ± 20.09 | 43 – 147 | 1.60 ± 0.11 | 0.5 – 11.77 | 143,724,211 (5.8%) | |

| Herd_06 | 33,831 | 20 – 741 | 89.26 ± 35.24 | 43 – 343 | 1.74 ± 0.13 | 0.5 – 27.08 | 155,410,159 (6.3%) | |

| Herd_07 | 6,219 | 20 – 295 | 82.61 ± 26.77 | 37 – 191 | 1.60 ± 0.11 | 0.5 – 10.58 | 133,243,688 (5.4%) | |

| SAA | Herd_08 | 6,366 | 20 – 353 | 52.61 ± 34.66 | 12 – 217 | 1.61 ± 0.13 | 0.5 – 12.57 | 84,869,461 (3.4%) |

| Herd_09 | 10,288 | 20 – 334 | 76.21 ± 34.11 | 24 – 243 | 1.64 ± 0.12 | 0.5 – 12.05 | 125,006,778 (5.1%) | |

| Herd_10 | 4,658 | 20 – 302 | 93.16 ± 52.90 | 30 – 284 | 1.67 ± 0.12 | 0.5 – 10.97 | 161,419,260 (6.5%) | |

| Total | CAM | 91,936 | 20 – 741 | 94.06 ± 34.55 | 29 – 417 | 1.73 ± 012 | 0.5 – 27.08 | 163,184,029 (6.61) |

| SAA | 21,312 | 20 – 353 | 69.64 ± 40.72 | 12 – 284 | 1.65 ± 0.12 | 0.5 – 12.57 | 115,085,238 (4.66) | |

Descriptive statistics for the ROH identified according to each Herd, and for overall CAM and SAA.

SNP n.= number of SNPs identified; SD=standard deviation;

1Mean Coverage = Average length of ROH coverage per genome across all herds, calculated first per sample and then averaged within each herd.

2%: Proportion calculated as the ratio between the Mean Coverage value and the genome length covered by the 64,273 SNPs = 2,468,379,888 base pairs (bp)

Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of ROH frequencies across all autosomes for each of the herds analyzed. The heatmap illustrates the average within-herd frequency of ROH coverage across each chromosome, providing a herd-level overview of autozygosity distribution along the genome. In general, CHR1 to CHR6 show the highest ROH frequencies across most herds. In contrast, CHR25 to CHR29 consistently exhibit lower ROH frequencies across all herds. This pattern is consistent for both breeds.

Figure 3

Distribution of ROH frequencies per CHR across each analyzed herd.

The ROH identified across populations were classified into five length classes. The frequency of ROHs in each class is illustrated in Figure 4. The most frequent ROHs were those shorter than 2 Mb, which comprised over 74% of the total ROHs detected. ROHs longer than 16 Mb were detected in only seven CAM goats (Herd_02, n=2; Herd_04, n=1; Herd_06, n=3), which is why this category is not represented in Figure 4. The distribution of ROHs across length classes is consistent among the herds (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Proportion of ROH for each class of length for each Herd and breed.

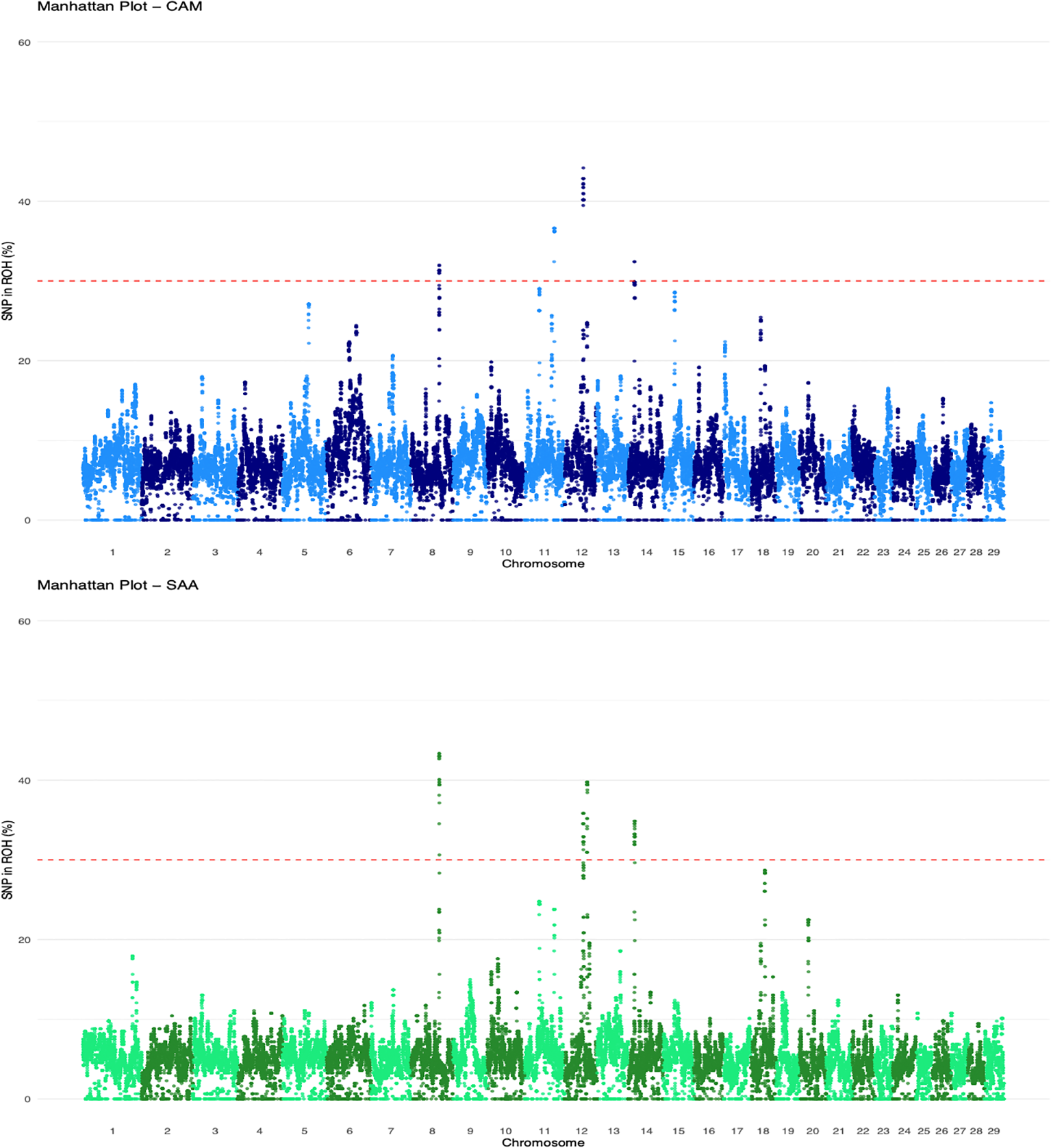

Figure 5 illustrates the distribution of SNPs located within ROH across all autosomes, shown as Manhattan plots for the two breeds (CAM and SAA). For each breed, the analysis was performed by combining all individuals across herds. Manhattan plots of individual herds are available in Supplementary Figure S3. Although no single island was shared across all herds, recurrent regions emerged both within (at herd level) and between breeds (Table 4). Notably, highly frequent ROH islands were mapped on CHR14 shared by 6 CAM and 3 SAA herds, and on CHR12 and CHR8 in common among 6 CAM and 2 SAA herds.

Figure 5

Manhattan plots showing the proportion of SNPs within ROH across all autosomes for CAM (top) and SAA (bottom) goats (all Herds were analysed together by breed).

Table 4

| CHR | CAM | SAA | Start | End | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | Herd_02 | 64491873 | 64965666 | NUP37, PARPBP, PMCH, IGF1 | |

| 5 | Herd_04, Herd_06 | 69633866 | 70344907 | PRDM4, ASCL4, RTCB, BPIFC, FBXO7, TIMP3, SYN3 | |

| 5 | Herd_05 | 108659404 | 109810433 | MICALL1, C5H22orf23, POLR2F, SOX10, PICK1, SLC16A8, BAIAP2L2, PLA2G6, MAFF, TMEM184B, KCNJ4, KDELR3, DDX17, DMC1, FAM227A, CBY1, TOMM22, JOSD1, GTPBP1, SUN2, DNAL4, NPTXR, CBX6, CBX7, PDGFB, RPL3, SYNGR1, TAB1, MGAT3 | |

| 5 | Herd_05 | 109819318 | 112678786 | MGAT3, MIEF1, ATF4, RPS19BP1, CACNA1I, ENTHD1, GRAP2, FAM83F, TNRC6B, ADSL, SGSM3, MKL1, MCHR1, SLC25A17, ST13, XPNPEP3, DNAJB7, RBX1, EP300, L3MBTL2, CHADL, RANGAP1, ZC3H7B, TEF, TOB2, PHF5A, ACO2, POLR3H, CSDC2, PMM1, DESI1, XRCC6, SNU13, MEI1, CCDC134, SREBF2, MIR33A, SHISA8, TNFRSF13C, CENPM, SEPT3, WBP2NL, NAGA, FAM109B, SMDT1, NDUFA6, TCF20, NFAM1, SERHL2, RRP7A, POLDIP3, A4GALT, ARFGAP3, PACSIN2 | |

| 6 | Herd_05 | 34257575 | 34831119 | CCSER1 | |

| 6 | Herd_06 | 58594485 | 59994807 | TLR10, TLR1, RPL9, TLR6, TMEM156, RFC1, KLB, LIAS, UGDH, RHOH, CHRNA9, KLHL5, WDR19, SMIM14, UBE2K, PDS5A, RBM47, FAM114A1 | |

| 6 | Herd_04 | 78018184 | 79209818 | ADGRL3 | |

| 7 | Herd_06 | 58759016 | 59086180 | SLC35A4, APBB3, EIF4EBP3, SRA1, SLC4A9, HBEGF, PFDN1, CYSTM1 | |

| 8 | Herd_05 | 69104053 | 69497379 | LGI3, SFTPC, MIR320, POLR3D, HR, REEP4, BMP1, PIWIL2, SLC39A14, PPP3CC, PHYHIP | |

| 8 | Herd_01, Herd_02, Herd_03, Herd_05, Herd_06, Herd_07 | Herd_09, Herd_010 | 74508923 | 75427691 | APTX, DNAJA1, SMU1, B4GALT1, SPINK4, BAG1, CHMP5, NFX1, AQP7, AQP3, NOL6, UBE2R2, UBAP2, DCAF12, UBAP1, KIF24 |

| 11 | Herd_01, Herd_02, Herd_04 | Herd_08, Herd_010 | 37760119 | 38712070 | CFAP36, PPP4R3B, EFEMP1, PNPT1, MIR217, MIR216B, CCDC85A |

| 11 | Herd_01, Herd_02 | 70960216 | 71577169 | PLB1, FOSL2, BRE, RBKS | |

| 11 | Herd_01, Herd_02, Herd_06 | 77891124 | 78577786 | GDF7, HS1BP3, RHOB, PUM2, SDC1, LAPTM4A, MATN3, WDR35 | |

| 12 | Herd_01, Herd_02, Herd_03, Herd_04, Herd_05, Herd_07 | Herd_09, Herd_010 | 49710719 | 50807424 | ATP12A, RNF17, CENPJ, PARP4, MPHOSPH8, PSPC1, ZMYM5, ZMYM2, GJA3, GJB2, GJB6, CRYL1 |

| 12 | Herd_01, Herd_02 | Herd_08, Herd_09_Herd_010 | 59935502 | 60862705 | MAB21L1, NBEA |

| 13 | Herd_02, Herd_05 | 1195883 | 1879609 | PLCB1, PLCB4 | |

| 14 | Herd_01, Herd_02, Herd_03, Herd_04, Herd_05, Herd_07 | Herd_08, Herd_09_Herd_010 | 16937162 | 17757900 | VPS13B |

| 15 | Herd_01, Herd_02, Herd_05 | 29781069 | 30731024 | RAB6A, PLEKHB1, FAM168A, RELT, ARHGEF17, P2RY6, P2RY2, FCHSD2, ATG16L2, STARD10, ARAP1 | |

| 17 | Herd_06 | 2885958 | 2980897 | ZNRF3 | |

| 18 | Herd_01, Herd_02, Herd_05 | 25227062 | 26113989 | LPCAT2, CAPNS2, SLC6A2, MT3, MT4, BBS2, NUDT21, AMFR, OGFOD1, GNAO1 | |

| 18 | Herd_05 | Herd_09, Herd_010 | 36166515 | 37136273 | PLEKHG4, KCTD19, LRRC36, TPPP3, ZDHHC1, HSD11B2, ATP6V0D1, FAM65A, AGRP, CTCF, CARMIL2, ACD, PARD6A, ENKD1, C18H16orf86, GFOD2, RANBP10, TSNAXIP1, CENPT, THAP11, NUTF2, EDC4, NRN1L, PSKH1, PSMB10, LCAT, SLC12A4, DPEP3, DPEP2, DDX28, DUS2, NFATC3, ESRP2, PLA2G15, SLC7A6, SLC7A6OS, PRMT7, SMPD3 |

| 18 | Herd_05 | 50636192 | 51078927 | PRX, SERTAD1, SERTAD3, BLVRB, SPTBN4, SHKBP1, LTBP4, NUMBL, COQ8B, ITPKC, C18H19orf54, SNRPA, MIA, RAB4B, EGLN2 | |

| 18 | Herd_10 | 58443269 | 58445841 | VSIG10L | |

| 26 | Herd_05 | 49370016 | 51133143 | CISD1, IPMK, UBE2D1 |

ROH islands details and annotated genes.

Herds and genes annotated in the corresponding region are highlighted using the same style (Normal, Bold, Underlined, or Italics).

A total of 105 genes were annotated within the ROH islands (Table 4), including 29 unique to CAM ROH, 17 unique to SAA ROH, and 59 shared between the two breeds. Among these, 26 genes overlap with QTL associated with production, reproductive, and functional traits, as reported in Supplementary Table S1.

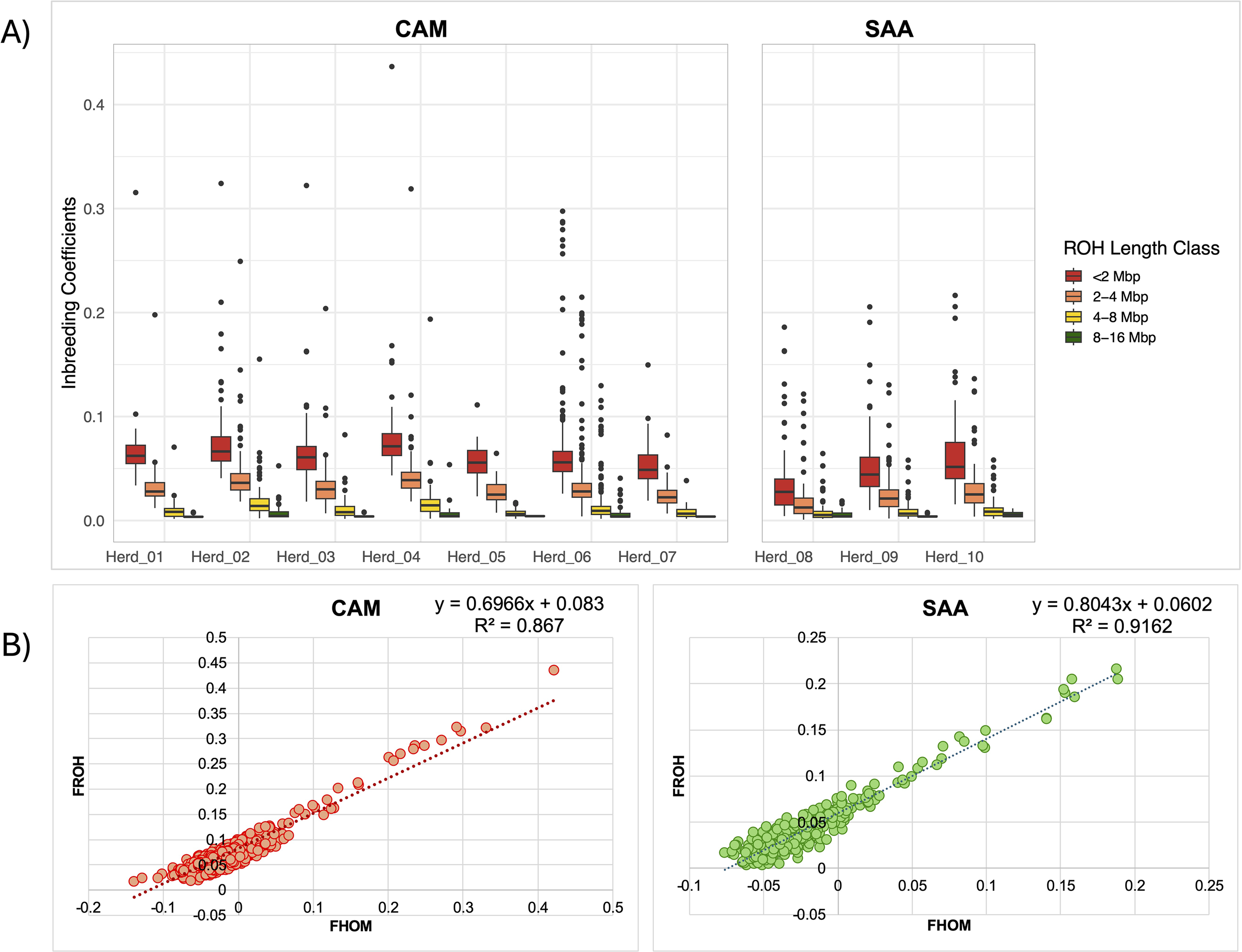

3.3 Inbreeding coefficients

The average genomic inbreeding coefficient based on ROH (FROH) was 0.060 for CAM and 0.041 for SAA goats (Supplementary Table S2). The highest FROH values observed were 0.437 in Herd_04 (CAM) and 0.216 in Herd_10 (SAA). Figure 6A displays the distribution of FROH across four ROH length classes (<2 Mb, 2–4 Mb, 4–8 Mb, and 8–16 Mb) in each herd. The herd-specific coefficients are detailed in Supplementary Table S3. Herd_08 showed the lowest FROH values across all length classes in both breeds. This trend is reflected in the overall mean FROH values of Herd_08, which were 0.036 in CAM and 0.033 in SAA. Due to the limited number of animals presenting ROH longer than 16 Mb, this class has not been considered in the graphical representation. In the 8–16 Mb class, associated with more recent genomic inbreeding, average FROH values per herd ranged from 0.004 to 0.008, with the highest value observed in Herd_02.

Figure 6

Graphical representations (boxplots) of FROH values, categorized according to the five different classes of ROH lengths (A); Coefficient of determination (R2) calculated between FROH and FHOM.

The FHOM values, which reflect the excess of observed homozygosity compared to expected values, were negative on average for both breeds (−0.023 in CAM and −0.017 in SAA), with higher values of 0.421 (Herd_04) for CAM and of 0.189 (Herd_09) for SAA. The descriptive statistics of FHOM values calculated for each herd is reported in Supplementary Table S2.

At the breed level, R² values indicate a strong overall correlation between FROH and FHOM (0.86 for CAM and 0.91 for SAA; Figure 6B). When examined by herd, Pearson r ranged from 0.93 to 0.99 (R² = 0.87–0.98), while Spearman p ranged from 0.88 to 0.97, with all p-values highly significant. These results confirm that both metrics consistently reflect individual genomic inbreeding, with detailed values provided in Supplementary Table S4.

4 Discussion

Alpine dairy goats such as CAM and SAA hold a pivotal role in sustaining genetic diversity and local dairy traditions in northern Italy. These breeds are extensively reared not only in mountain and pre-Alpine areas, where they contribute to landscape preservation and rural livelihoods, but also in lowland commercial farms, where their high productivity and adaptability support large farm milk production systems (Battaglini, 2007; Cortellari et al., 2021b).

By combining PCA, admixture analyses, ROH profiling, and inbreeding‐coefficient estimates, we obtained a comprehensive picture of the genomic structure of CAM and SAA goats across the ten Lombardy farms. These complementary approaches reveal how herd-specific management strategies and historical breeding choices have shaped the genomic landscape of both breeds, influencing levels of homozygosity, inbreeding, and differentiation among herds. Herds enrolled in this study operate independently, with breeding and mating plans based on the goals and reproductive management practices of each farmer. The clear separation between CAM and SAA in the combined PCA reflects breed-level genetic differentiation, in line with previous findings in these goat breeds (Brito et al., 2017). Within CAM, most herds formed tight clusters, indicative of relatively homogeneous breeding lines. However, Herd_06 showed a broader dispersion, likely reflecting the use of bucks from diverse genetic origins, which may have introduced greater variability. In contrast, all SAA herds exhibited greater genetic dispersion, possibly due to the introgression of Dutch genetic lines introduced to enhance milk production, as reported by breeders at the time of herd book registration (Supplementary Table S5). ADMIXTURE analysis with K = 4 revealed a complex ancestral structure within and across herds, despite the dataset including only two breeds (CAM and SAA). This suggests the presence of multiple genetic backgrounds within each breed, likely due to the use of bucks from different national or commercial lines, as well as herd-specific breeding strategies (Punturiero et al., 2023). In CAM herds, distinct ancestry components point to limited exchange of genetic material among farms and selection focused on different traits or production goals. These differences indicate that CAM herds do not share a uniform genetic profile but instead reflect herd-specific selection histories or the use of bucks from distinct genetic sources (Waineina et al., 2020). The consistent ancestral signal observed in most herds suggests a shared genetic foundation, likely due to the use of similar or closely related breeding lines. Regarding the SAA, Herd_08 stands out with a slightly more admixed profile respect Herd_09 and Herd_10, showing larger contributions from ancestors 1, 3, and 4, may be because the presence of CAM goats in past generations. Similar dynamics have been reported in other European dairy goat populations, where intensive selection, the importation of genetic material of selected bucks, and constrained within-herd mating practices have contributed to fine-scale population structuring (Peripolli et al., 2017; Mastrangelo et al., 2021).

When we compared the number of shared bucks across FA herds (using the official animal identification code recorded in the herdbook provided by farmers), we observed a very limited level of common FA bucks use (Supplementary Table S5). The same buck was used in a maximum of three herds, and typically sired between two and six half-sibling daughters per farm. This restricted sharing pattern suggests that male selection in these herds is largely independent, with each farm relying on its own breeding strategy and limited external male input. This low level of buck sharing likely contributes to the variability observed in the admixture profiles of herds using instrumental insemination. Unlike the two SAA herds, which displayed consistent ancestral signals, the CAM herds showed more heterogeneous patterns. The observed differences in admixture can be explained by the use of distinct and often unrelated sires, resulting in herd-specific genetic backgrounds. Independent mating strategies and limited gene flow between herds have likely shaped these unique genetic structures, as reflected in the varying degrees of admixture identified across farms.

Inbreeding estimates and ROH.

The moderate overall FROH (0.060 in CAM; 0.041 in SAA) and negative mean FHOM (-0.023 in CAM; -0.017 in SAA) (Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Table S3) indicate that, despite some recent inbreeding, most herds is keen to maintain genetic variability varying at best the male used in reproduction, similar to other well−managed dairy goat populations (Luigi-Sierra et al., 2022; Vostry et al., 2024). The high correlation observed between FROH and FHOM (Figure 6B) suggests that homozygosity is not randomly distributed across the genome, but rather tends to cluster within ROH.

The genome-wide ROH identified in this study, revealed a predominance of short segments (<2 Mb), which are typically indicative of ancient inbreeding events or past population bottlenecks, where increased homozygosity results from remote common ancestors. Over generations, recombination fragments these regions, leading to shorter homozygous tracts (Keller et al., 2011; Peripolli et al., 2017). Interestingly, ROH segments between 8–16 Mb were observed only in a few individuals. This pattern may reflect occasional recent inbreeding events, which could occur unintentionally in large-scale herds where the management of mating groups to control inbreeding becomes more complex. While small herds often apply well-structured breeding strategies, larger operations may face challenges due to the lack of mandatory paternity testing and the potential for misassigned sires across mating groups. In such cases, the true pedigree structure can become blurred, leading to undetected related matings and, consequently, longer ROH in some animals. The near absence of ROH >16 Mb, however, suggests that very close kin matings (e.g., parent-offspring) remain rare.

The distribution of ROH observed in Alpine goats in this study aligns with findings in other goat breeds, such as Egyptian and various Italian breeds, where a predominance of short ROH segments has been reported, suggesting historical selection and inbreeding events. Recent studies on Alpine and Mediterranean goat breeds have further highlighted breed-specific ROH patterns, reflecting the influence of breeding practices and environmental adaptations (Manunza et al., 2023; Pegolo et al., 2025). Similar patterns of ROH length distributions, reflecting both ancient and recent inbreeding, have also been reported in other livestock species such as cattle and sheep, highlighting the general influence of herd management, mating strategies, and demographic history on genomic homozygosity (Strillacci et al., 2020; Benedetti del Rio et al., 2025). The integration of ROH length distribution with the analysis of ROH islands adds further resolution to these patterns. While short ROHs point to ancient demographic events (Doekes et al., 2019), ROH islands reveal signatures of both shared and herd-specific selective pressures. Several genomic regions are common to both CAM and SAA, consistent with their shared ancestry and exposure to similar selection regimes, whereas others appear breed-specific, reflecting divergent breeding goals and management choices. Moreover, some ROH islands are consistently shared across multiple herds (Table 4), which may indicate the diffusion of particular haplotypes through the widespread use of popular sires or parallel selection schemes. Conversely, herd-specific ROH islands highlight unique management histories or localized selection pressures. Taken together, these findings demonstrate how both historical demographic processes and herd-level breeding dynamics have shaped the genomic landscape of Alpine dairy goats in Lombardy.

Common ROH islands – CAM and SAA.

Regarding ROH islands, when grouping herds by breed, we identified three shared homozygous regions: on CHR8 (74 Mbp), CHR12 (49 Mbp), and CHR14 (16 Mbp). These regions harbor 19 genes, of which several appear in the STRING/Cytoscape network (Supplementary Figure S4), highlighting functional connections among genes related to stress adaptation (ZMYM2, PARP4), metabolic homeostasis (AQP3, ATP12A), and fertility (RNF17, PSPC1). Notably, many of these genes show convergent selection signals in small ruminants. For example, ZMYM2, PARP4, PSPC1, MPHOSPH8, ATP12A, and RNF17 have been found in ROH islands in Italian Garfagnina goats and Mediterranean breeds selected for resilience and productivity (Dadousis et al., 2021; Serranito et al., 2021). The gene RNF17, crucial for spermatogenesis and gamete interactions, was also identified in Egyptian Barki goats, strengthening its role in reproductive efficiency and environmental resilience (Sallam et al., 2023). The aquaporin genes, AQP3 and AQP7, are essential for water, glycerol, and urea transport, enabling thermoregulation and heat-stress adaptation. Additionally, AQP3 has been linked to reduced reproductive performance in goats under repeated estrus synchronization (Sun et al., 2023). In addition, the AQP3, AQP7, UBE2R2, NFX1, DCAF12, and UBAP2 genes appear within heterozygosity-rich or selected regions across sheep and goat breeds (Mészárosová et al., 2022). Recent studies in livestock, including goats, have characterized heterozygosity-rich regions (HRRs) that overlap with ROH islands. If any of our ROH islands (for example, on CHR8 at 74 Mbp) (Chessari et al., 2024) overlaps with a known HRR, this would indicate that the region is homozygous in certain populations but highly variable in others. This pattern is a hallmark of balancing selection, where functionally important variants (e.g., related to immunity, stress adaptation, fertility) are maintained as both fixed and polymorphic across different lineages.

The VPS13B gene emerged as one of the most consistently detected across analyses: it was present in both CAM and SAM groups and found in 9 out of 10 herds examined. VPS13B has functional relevance supported by associations in both cattle and goats. In Bos taurus, VPS13B resides within a QTL on CHR14 linked to female fertility and milk production traits (Liu et al., 2018). In addition, VPS13B has been identified as under selection in Mediterranean and Chinese goats and is linked to leg morphology, a trait frequently correlated with fertility and milk yield (Amiri Ghanatsaman et al., 2023).

Breed specific ROH_islands – CAM.

Among the genes unique to CAM herds, several exhibit strong cross-species associations with economically important traits. In the domain of stress resilience and immune function, AMFR was identified in a dairy cattle GWAS as a candidate for heat-stress response and milk fatty acid composition, while ATG16L2, an autophagy-related gene, has been linked to immune resilience and mastitis recovery in Holsteins (Welderufael et al., 2018). Additional genes involved in disease resistance and immune modulation include ARHGEF17, has been associated with disease resistance in cattle (Ghoreishifar et al., 2020) and linked to gastrointestinal nematode resilience through IgA regulation in sheep (Atlija et al., 2016). A similar immunological role has also been proposed for the RELT and FCHSD2 genes.

In terms of growth and skeletal development, ARAP1 is located within QTL regions relevant to viability and meat productivity in sheep hybrids (Zlobin et al., 2023), while MATN3 variants are robustly tied to skeletal integrity and stature in cattle (Lopdell and Littlejohn, 2018).

The CAPNS2 gene, which encodes calpain-2, plays a significant role in follicular development and has been specifically implicated in goat reproductive physiology, as shown in a study comparing gene expression in the ovaries of polytocous and monotocous dairy goats (An et al., 2012).

Breed specific ROH_islands – SAA.

Among the genes unique to SAA herds, several have well-characterized roles in functional and production traits across livestock. A key finding is the association of APTX with the marbling score in Hanwoo cattle: co-expression network analysis highlighted APTX as a hub gene correlated with intramuscular fat content, supporting its potential role in meat quality (Lim et al., 2013). In dairy cattle, ATP6V0D1 was identified via integrated transcriptomic–proteomic analysis in Holstein mammary glands, suggesting its involvement in ATP production in the mammary tissue (Dai et al., 2018).

Multiple genes also contribute to environmental adaptation, especially in heat and thermal stress response. DNAJA1, an HSP40 chaperone, was highly expressed in sheep mammary tissue and linked to milk synthesis, while also being repeatedly associated with heat-stress response in cattle (Freitas et al., 2021). Similarly, CRYL1 emerged from ROH analyses in Chinese sheep and Garfagnina goats adapted to diverse climates, pointing to a role in environmental resilience (Abied et al., 2020; Dadousis et al., 2021).

Genes involved in immune and resilience traits also surfaced prominently in SAA-specific ROH. GJA3, GJB2, GJB6, and MAB21L1 were highlighted in Ugandan goat breeds under selection for adaptability and in the Boer breed, GJB2 and GJA3 are indicated as candidate genes associated with production traits, such as body size and growth (Onzima et al., 2018). The genomic region harbouring GJA3, GJB2, and GJB6 also represents a selection signature previously identified in the Garfagnina goat breed.

Additional genes previously identified in goats include UBAP1, which is associated with a QTL for cannon bone circumference (QTL ID 314136), suggesting a role in skeletal development, and ZDHHC1, which overlaps with QTLs for somatic cell score (QTL IDs 296969 and 296970), indicating its potential involvement in udder health and mastitis resistance in caprine production.

5 Conclusion

This study provides a snapshot of the genetic landscape of Alpine dairy goats (CAM and SAA) raised under commercial and semi-extensive systems in Lombardy, using SNP chip genotypes from a large number of individuals. By integrating genome-wide SNP data with ROH-based inbreeding and population structure analyses, we reveal insights of direct relevance for herd management and conservation. Despite historical selection pressures, overall genetic diversity remains within acceptable ranges, particularly in CAM, reflecting effective management strategies that preserve variability even without formal pedigree control. However, marked differences emerge across herds, shaped by specific reproductive histories and decisions. In SAA, the introduction of Dutch genetics increased heterozygosity and ROH variability, supporting productivity in the short term but potentially diluting original lines and threatening long-term resilience. ROH islands shared across or specific to breeds pointed to candidate genes for stress adaptation, metabolism, fertility, and immune response, traits crucial for sustainable production. This work highlights the need to integrate genomic tools into herd monitoring.

In conclusion, balancing productivity and genetic diversity is feasible through data-informed decisions. Genotyping all herd animals provides actionable information to improve reproductive efficiency, preserve genetic resources, and ensure the long-term sustainability of Alpine goat farming in Lombardy.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article and its Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The animal studies were approved by All procedures adhered to European and Italian legislation (2010/63/EU Directive and Legislative Decree No. 26/2014) and received approval from the Animal Welfare Body of the Università degli Studi di Milano (OPBA) as well as the Italian Ministry of Health (protocol number OPBA_68_2023). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from the owners for the participation of their animals in this study.

Author contributions

CF: Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CP: Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AD: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. RM: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing. AB: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. MGS: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This project was funded by the EAFRD Rural Development Program 2014-2020, Management Autority Regione Lombardia -OP. 16.1.01 Project title: "Applicazione della genomica negli allevamenti di capre da latte - CapraGEN"; Project ID n. 202202380565 -'Operational Group EIP AGRI'.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the farmer.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI (ChatGPT, OpenAI) was used to improve English grammar and language clarity during manuscript preparation.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fanim.2025.1664380/full#supplementary-material

References

1

AbiedA.XuL.SahluB. W.XingF.AhbaraA.PuY.et al. (2020). Genome-wide analysis revealed homozygosity and demographic history of five Chinese sheep breeds adapted to different environments. Genes (Basel)11, 1480. doi: 10.3390/genes11121480

2

AgradiS.MenchettiL.CuroneG.FaustiniM.VigoD.VillaL.et al. (2022). Comparison of female verzaschese and camosciata delle alpi goats’ hematological parameters in the context of adaptation to local environmental conditions in semi-extensive systems in Italy. Animals12, 1703. doi: 10.3390/ani12131703

3

AlexanderD. H.NovembreJ.LangeK. (2009). Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res.19, 1655–1664. doi: 10.1101/gr.094052.109

4

Amiri GhanatsamanZ.Ayatolahi MehrgardiA.Asadollahpour NanaeiH.EsmailizadehA. (2023). Comparative genomic analysis uncovers candidate genes related with milk production and adaptive traits in goat breeds. Sci. Rep.13, 8722. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-35973-0

5

AnX. P.HouJ. X.LiG.PengJ. Y.LiuX. Q.LiuH. Y.et al. (2012). Analysis of differentially expressed genes in ovaries of polytocous versus monotocous dairy goats using suppressive subtractive hybridization. Reprod. Domest. Anim.47, 498–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2011.01910.x

6

AssoNaPa (2025). Associazione Nazionale della Pastorizia. Available online at: https://www.assonapa.it (Accessed October 2, 2025).

7

AtlijaM.ArranzJ.-J.Martinez-ValladaresM.Gutiérrez-GilB. (2016). Detection and replication of QTL underlying resistance to gastrointestinal nematodes in adult sheep using the ovine 50K SNP array. Genet. Selection Evol.48, 4. doi: 10.1186/s12711-016-0182-4

8

BattagliniL. M. (2007). L’allevamento ovino e caprino nelle Alpi ( Tra valenze ecoculturali e sostenibilità economica). Available online at: https://www.sozooalp.it/fileadmin/superuser/Quaderni/quaderno_4/Quaderno_SZA4_Completo.pd.

9

Benedetti del RioE.MancinE.OrsiM.MantovaniR.SturaroE. (2025). Genomic characterisation of local sheep breeds of the Eastern Alps. Ital J. Anim. Sci.24, 1528–1541. doi: 10.1080/1828051X.2025.2515271

10

BertoliniF.CardosoT. F.MarrasG.NicolazziE. L.RothschildM. F.AmillsM. (2018). Genome-wide patterns of homozygosity provide clues about the population history and adaptation of goats. Genet. Sel. Evol.50, 59. doi: 10.1186/s12711-018-0424-8

11

BiscariniF.CozziP.GaspaG.MarrasG. (2018). detectRUNS: an R package to detect runs of runs of homozygosity and heterozygosity in diploid genomes ( IBBA-CNR, PTP, Università degli Studi di Sassari, University of Guelph), 01. Available online at: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/detectRUNS/vignettes/detectRUNS.vignette.html

12

BritoL. F.KijasJ. W.VenturaR. V.SargolzaeiM.Porto-NetoL. R.CánovasA.et al. (2017). Genetic diversity and signatures of selection in various goat breeds revealed by genome-wide SNP markers. BMC Genomics18, 1–20. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-3610-0

13

ChessariG.CriscioneA.MarlettaD.CrepaldiP.PortolanoB.ManunzaA.et al. (2024). Characterization of heterozygosity-rich regions in Italian and worldwide goat breeds. Sci. Rep.14, 3. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-49125-x

14

CortellariM.BarbatoM.TalentiA.BiondaA.CartaA.CiampoliniR.et al. (2021a). The climatic and genetic heritage of Italian goat breeds with genomic SNP data. Sci. Rep.11, 10986. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-89900-2

15

CortellariM.BiondaA.NegroA.FrattiniS.MastrangeloS.SomenziE.et al. (2021b). Runs of homozygosity in the Italian goat breeds: Impact of management practices in low-input systems. Genet. Selection Evol.53, 1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12711-021-00685-4

16

DadousisC.CecchiF.AblondiM.FabbriM. C.StellaA.BozziR. (2021). Keep Garfagnina alive. An integrated study on patterns of homozygosity, genomic inbreeding, admixture and breed traceability of the Italian Garfagnina goat breed. PloS One16, e0232436. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232436

17

DaiW.WangQ.ZhaoF.LiuJ.LiuH. (2018). Understanding the regulatory mechanisms of milk production using integrative transcriptomic and proteomic analyses: improving inefficient utilization of crop by-products as forage in dairy industry. BMC Genomics19, 403. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4808-5

18

DixitS. P.SinghS.GangulyI.BhatiaA. K.SharmaA.KumarN. A.et al. (2020). Genome-wide runs of homozygosity revealed selection signatures in bos indicus. Front. Genet.11, 92. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00092

19

DoekesH. P.VeerkampR. F.BijmaP.de JongG.HiemstraS. J.WindigJ. J. (2019). Inbreeding depression due to recent and ancient inbreeding in Dutch Holstein–Friesian dairy cattle. Genet. Selection Evol.51, 1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12711-019-0497-z

20

FreitasP. H. F.WangY.YanP.OliveiraH. R.SchenkelF. S.ZhangY.et al. (2021). Genetic diversity and signatures of selection for thermal stress in cattle and other two Bos species adapted to divergent climatic conditions. Front. Genet.12, 604823. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.604823

21

GhoreishifarS. M.ErikssonS.JohanssonA. M.KhansefidM.Moghaddaszadeh-AhrabiS.ParnaN.et al. (2020). Signatures of selection reveal candidate genes involved in economic traits and cold acclimation in five Swedish cattle breeds. Genet. Selection Evol.52, 52. doi: 10.1186/s12711-020-00571-5

22

GibsonJ.MortonN. E.CollinsA. (2006). Extended tracts of homozygosity in outbred human populations. Hum. Mol. Genet.15, 789–795. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi493

23

Grilz-SegerG.MesaričM.CotmanM.NeuditschkoM.DrumlT.BremG. (2018). Runs of homozygosity and population history of three horse breeds with small population size. J. Equine Vet. Sci.71, 27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jevs.2018.09.004

24

HillestadB.WoolliamsJ. A.BoisonS. A.GroveH.MeuwissenT.VågeD. I.KlemetsdalG.. (2017). Detection of runs of homozygosity in Norwegian Red: Density, criteria and genotyping quality control. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section A—Anim. Sci.67, 107–116.

25

HuZ. L.ParkC. A.ReecyJ. M. (2022). Bringing the Animal QTLdb and CorrDB into the future: Meeting new challenges and providing updated services. Nucleic Acids Res.50, D956–D961. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1116

26

HuZ. L.ParkC. A.WuX. L.ReecyJ. M. (2013). Animal QTLdb: An improved database tool for livestock animal QTL/association data dissemination in the post-genome era. Nucleic Acids Res.41, D871–D879. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1150

27

KellerM. C.VisscherP. M.GoddardM. E. (2011). Quantification of inbreeding due to distant ancestors and its detection using dense single nucleotide polymorphism data. Genetics.189, 237–249. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.130922

28

KimE. S.ColeJ. B.HusonH.WiggansG. R.Van TasselC. P.CrookerB. A.et al. (2013). Effect of artificial selection on runs of homozygosity in U.S. Holstein cattle. PloS One8, 1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080813

29

LawsonD. J.van DorpL.FalushD. (2018). A tutorial on how not to over-interpret STRUCTURE and ADMIXTURE bar plots. Nat. Commun.9, 3258. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05257-7

30

LimD.LeeS.-H.KimN.-K.ChoY.-M.ChaiH.-H.SeongH.-H.et al. (2013). Gene co-expression analysis to characterize genes related to marbling trait in Hanwoo (Korean) cattle. Asian-Australas J. Anim. Sci.26, 19. doi: 10.5713/ajas.2012.12375

31

LiuJ. J.LiangA. X.CampanileG.PlastowG.ZhangC.WangZ.et al. (2018). Genome-wide association studies to identify quantitative trait loci affecting milk production traits in water buffalo. J. Dairy Sci.101, 433–444. doi: 10.3168/jds.2017-13246

32

LongeriM. L.ZaniboniL.CozziM. C.MilanesiR.BagnatoA. (2021). “ Animal Bio Arkivi: establishment of a phenotype and tissue repository for farm animals and pets at the University of Milan,” in ASPA congress ( Taylor & Francis) Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 20, 136.

33

LopdellT. J.LittlejohnM. D. (2018). MATN3 underlies a QTL for stature in cattle. New Z. J. Anim. Sci. Production78, 51–55.

34

Luigi-SierraM. G.FernándezA.MartínezA.GuanD.DelgadoJ. V.ÁlvarezJ. F.et al. (2022). Genomic patterns of homozygosity and inbreeding depression in Murciano-Granadina goats. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol.13, 35. doi: 10.1186/s40104-022-00684-5

35

MakinoT.RubinC. J.CarneiroM.AxelssonE.AnderssonL.WebsterM. T. (2018). Elevated proportions of deleterious genetic variation in domestic animals and plants. Genome Biol. Evol.10, 276–290. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evy004

36

ManunzaA.Ramirez-DiazJ.CozziP.LazzariB.Tosser-KloppG.ServinB.et al. (2023). Genetic diversity and historical demography of underutilised goat breeds in North-Western Europe. Sci. Rep.13, 20728. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-48005-8

37

MastrangeloS.Di GerlandoR.SardinaM. T.SuteraA. M.MoscarelliA.ToloneM.et al. (2021). Genome-wide patterns of homozygosity reveal the conservation status in five Italian goat populations. Animals11, 1510. doi: 10.3390/ani11061510

38

MastrangeloS.SardinaM. T.ToloneM.Di GerlandoR.SuteraA. M.FontanesiL.et al. (2018). Genome-wide identification of runs of homozygosity islands and associated genes in local dairy cattle breeds. Animal12, 2480–2488. doi: 10.1017/S1751731118000629

39

McQuillanR.LeuteneggerA.-L.Abdel-RahmanR.FranklinC. S.PericicM.Barac-LaucL.et al. (2008). Runs of homozygosity in European populations. Am. J. Hum. Genet.83, 359–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.08.007

40

McSweeneyP. L. H.McNamaraJ. P. (2022). Encyclopedia of Dairy Sciences. 3rd Edn. (Amsterdam, Netherlands: Academic Press (Elsevier)).

41

MészárosováM.MészárosG.MoravčíkováN.PavlíkI.MargetínM.KasardaR. (2022). Within-and between-breed selection signatures in the original and improved Valachian sheep. Animals12, 1346. doi: 10.3390/ani12111346

42

NothnagelM.LuT. T.KayserM.KrawczakM. (2010). Genomic and geographic distribution of snpdefined runs of homozygosity in Europeans. Hum. Mol. Genet.19, 2927–2935. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq198

43

Ojeda-MarínC.GutiérrezJ. P.Formoso-RaffertyN.GoyacheF.CervantesI. (2024). Differential patterns in runs of homozygosity in two mice lines under divergent selection for environmental variability for birth weight. J. Anim. Breed. Genet.141, 193–206. doi: 10.1111/jbg.12835

44

OnzimaR. B.UpadhyayM. R.DoekesH. P.BritoL. F.BosseM.KanisE.et al. (2018). Genome-wide characterization of selection signatures and runs of homozygosity in Ugandan goat breeds. Front. Genet.9, 318. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00318

45

PegoloS.BisuttiV.MotaL. F. M.CecChinatoA.AmalfitanoN.DettoriM. L.et al. (2025). Genome-wide landscape of genetic diversity, runs of homozygosity, and runs of heterozygosity in five Alpine and Mediterranean goat breeds. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol.16, 33. doi: 10.1186/s40104-025-01155-3

46

PeripolliE.MetzgerJ.De LemosM. V. A.StafuzzaN. B.KluskaS.OlivieriB. F.et al. (2018). Autozygosity islands and ROH patterns in Nellore lineages: evidence of selection for functionally important traits. BMC Genomics19, 680. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-5060-8

47

PeripolliE.MunariD. P.SilvaM.LimaA. L. F.IrgangR.BaldiF. (2017). Runs of homozygosity: current knowledge and applications in livestock. Anim. Genet.48, 255–271. doi: 10.1111/age.12526

48

PunturieroC.MilanesiR.BerniniF.DelledonneA.BagnatoA.StrillacciM. G. (2023). Genomic approach to manage genetic variability in dairy farms. Ital J. Anim. Sci.22, 769–783. doi: 10.1080/1828051X.2023.2243977

49

PurfieldD. C.BerryD. P.McParlandS.BradleyD. G. (2012). Runs of homozygosity and population history in cattle. BMC Genet.13, 70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-13-70

50

Regulation (EU) 2016/1012 (2016). Regulation (EU) 2016/1012. Available online at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/1012/oj/eng (Accessed October 3, 2025).

51

SallamA. M.ReyerH.WimmersK.BertoliniF.Aboul-NagaA.BrazC. U.et al. (2023). Genome-wide landscape of runs of homozygosity and differentiation across Egyptian goat breeds. BMC Genomics24, 573. doi: 10.1186/s12864-023-09679-6

52

SchiavoG.BovoS.MuñozM.RibaniA.AlvesE.AraújoJ. P.et al. (2021). Runs of homozygosity provide a genome landscape picture of inbreeding and genetic history of European autochthonous and commercial pig breeds. Anim. Genet.52, 155–170. doi: 10.1111/age.13045

53

SenczukG.MastrangeloS.CianiE.BattagliniL.CendronF.CiampoliniR.et al. (2020). The genetic heritage of Alpine local cattle breeds using genomic SNP data. Genet. Selection Evol.52, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12711-020-00559-1

54

SerranitoB.CavalazziM.VidalP.Taurisson-MouretD.CianiE.BalM.et al. (2021). Local adaptations of Mediterranean sheep and goats through an integrative approach. Sci. Rep.11, 21363. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-00682-z

55

ShannonP.MarkielA.OzierO.BaligaN. S.WangJ. T.RamageD.et al. (2003). Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res.13, 2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303

56

StrillacciM. G.VeveyM.BlanchetV.MantovaniR.SartoriC.BagnatoA. (2020). The genomic variation in the aosta cattle breeds raised in an extensive alpine farming system. Animals10, 2385. doi: 10.3390/ani10122385

57

SunS.LvM.NiuH.LuoJ. (2023). Role of aquaporin 3 in reproductive performance of dairy goats after repeated estrus synchronization stimulation. Reprod. Domest. Anim.58, 851–859. doi: 10.1111/rda.14358

58

SzpiechZ. A.XuJ.PembertonT. J.PengW.ZöllnerS.RosenbergN. A.et al. (2013). Long runs of homozygosity are enriched for deleterious variation. Am. J. Hum. Genet.93, 90–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.05.003

59

VostryL.Vostra-VydrovaH.MoravcikovaN.KasardaR.MargetinM.RychtarovaJ.et al. (2024). Genomic analysis of conservation status, population structure, and admixture in local Czech and Slovak dairy goat breeds. J. Dairy Sci.107, 8205–8222. doi: 10.3168/jds.2023-24607

60

WaineinaR. W.NgenoK.OtienoT. O.IlatsiaE. D. (2020). Genetic diversity and population structure among goat genotypes in Kenya. Genetic Resources2, 25–352. doi: 10.46265/genresj.EQFQ1540

61

WelderufaelB. G.LøvendahlP.De KoningD.-J.JanssL. L. G.FikseW. F. (2018). Genome-wide association study for susceptibility to and recoverability from mastitis in Danish Holstein cows. Front. Genet.9, 141. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00141

62

WickhamH. (2016). ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis (New York: Springer-Verlag). Available online at: https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org (Accessed May 2, 2021).

63

WilkinsonL. (2011). ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis by WICKHAM. H. Biometrics67, 678–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2011.01616.x

64

WrightS. (1949). The genetical structure of populations. Annals of Eugenics15, 323–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1949.tb02451.x

65

XieR.ShiL.LiuJ.DengT.WangL.LiuY.et al. (2019). Genome-wide scan for runs of homozygosity identifies candidate genes in three pig breeds. Animals9, 518. doi: 10.3390/ani9080518

66

ZhangQ.GuldbrandtsenB.BosseM.LundM. S.SahanaG.. (2015). Runs of homozygosity and distribution of functional variants in the cattle genome. BMC genomics16, 542.

67

ZlobinA. S.VolkovaN. A.ZinovievaN. A.IolchievB. S.BagirovV. A.BorodinP. M.et al. (2023). Loci associated with negative heterosis for viability and meat productivity in interspecific sheep hybrids. Animals13, 184. doi: 10.3390/ani13010184

Summary

Keywords

goats, Camosciata delle alpi, Saanen, genetic variability, homozygosity

Citation

Ferrari C, Punturiero C, Delledonne A, Milanesi R, Bagnato A and Strillacci MG (2025) Genetic insights into Alpine goats raised on Lombardy’s farms. Front. Anim. Sci. 6:1664380. doi: 10.3389/fanim.2025.1664380

Received

11 July 2025

Revised

03 October 2025

Accepted

06 November 2025

Published

03 December 2025

Volume

6 - 2025

Edited by

Kristopher Irizarry, Western University of Health Sciences, United States

Reviewed by

Henrique A. Mulim, Purdue University, United States

Giorgio Chessari, University of Catania, Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Ferrari, Punturiero, Delledonne, Milanesi, Bagnato and Strillacci.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maria Giuseppina Strillacci, maria.strillacci@unimi.it

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.