- 1Central Animal Research Facility, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India

- 2Center for Animal Research, Ethics and Training (CARET), Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India

- 3Department of Pharmacology, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India

- 4Department of Pediatrics, Dr. TMA Pai Rotary Hospital, Karkala, Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India

Animal models for several decades have offered a foundation for discovering human physiology along with promoting therapeutic innovation. However, limitations like translational gaps, controversy-ridden ethics, and regulatory issues are even more dearly acknowledged now. The “3Rs” (replacement, reduction, refinement) charts its course to humane as well as efficacious science with artificial intelligence (“AI”) as a chief facilitator of such a transition. By delivering sophisticated analytical power, AI renders 3Rs enforceable with concomitant predictions, simulations, and validations while minimizing animal subjects’ dependency. Machine and deep-learning algorithms are capable of processing massive, complex datasets to simulate human biology, forecast therapy outcomes, and discover candidate drugs, thereby circumventing large-scale animal usage. In such a manner, AI can directly facilitate replacement while promoting reduction through maximized experimental designs as well as refinement through data-driven improvements for animal welfare. The interplay of AI as well as the latest alternative methods such as organoids, organs-on-chips, and body-on-chip devices is emphasized within this review, which also briefs on evolving international policies with regard to AI ethics guidelines. This mini-review evaluates the modern role of AI in biomedical research, presenting its role across drug discovery, toxicology, disease modeling, and personalized therapy. We evaluate both encouraging prospects and existing challenges such as strict validation requirements and ethics controls as well as interdisciplinary collaboration that inform AI’s embracing within animal-research-free models.

1 Introduction

Researchers have depended on animal models for knowledge of human physiology, disease mechanisms, and therapy developments for generations (Akbarein et al., 2025). The why is simple: many animals, especially mammals, share human-like anatomy and physiology that makes it possible for scientists to study complex systems like circulation, hormonal networks, cells, and tissues in ways that are not possible otherwise (Mukherjee et al., 2022). As a result, animal models have propelled noteworthy biomedical advancements from tracing cell signaling pathways to identifying drug targets to informing cancer and infectious disease therapy (Kim et al., 2020). However, they are far from perfect. Results from animals are not always universally applicable to humans, which can result in lost time as well as resources and delayed medical advancements (Mukherjee et al., 2022). Ethical issues regarding animal welfare create another dimension of challenge due to the sheer number utilized annually. In response to these scientific and moral challenges as well as the growing regulatory pressure, the research community increasingly goes to the 3Rs: reduce, refine, and replace animal utilization wherever it is possible (Maji and Lee, 2022).

3Rs (replacement, reduction, refinement) is a utilitarian approach that serves as a practical tool to encourage the efficient and moral performance of research. Replacement involves the use of substitutes for animal models wherever possible, such as cell culture, computational modeling, or well-designed human research. Reduction involves the reduction of the number of animals used while retaining statistical power with improved experimental design and high-resolution imaging methods. Refining involves procedural changes to reduce pain and distress suffered by the animals (Kendall et al., 2018). The interplay between scientific limitations, ethically driven considerations, and changing regulations placed on research scientists has led to a drive to explore new methodologies, with computational methods and artificial intelligence (AI) holding particular promise.

AI has become a central collaborator within the ambit of 3Rs. Through the use of deep-learning algorithms that are expert at pattern detection in massive multi-omics, imaging, and clinical datasets, AI provides in silico substitutions for traditional in vivo experiments. The computational models not only increase the accuracy of predictions of biological response but also enable iterative refinement of hypotheses before animal testing is begun. AI, which includes machine learning as well as deep learning, is showing its potential to unravel complex biological data, predict treatment response, and simulate biological processes. Such approaches can help address certain disadvantages of traditional animal models through high-throughput methods that are cost-effective as well as ethically preferable research approaches. AI-driven models can integrate heterogeneous datasets of different types, such as genomics, proteomics, and clinical records, thus creating detailed perspectives on biological systems, helping to predict drug action, determine disease pathways, and tailor therapy approaches. Properly applying the 3Rs usually means combining computational models with bioinformatics, in vitro systems, biochemical assays, and selective use of model organisms (Doke and Dhawale, 2015). Because AI can learn from massive datasets and detect subtle patterns humans might miss, it has unique potential to speed up discoveries and improve translation from bench to bedside.

Earlier reviews tended to describe AI applications broadly across healthcare; however, few have critically evaluated how these tools contribute to measurable animal replacement or reduction. The present review, therefore, adopts an analytical lens, linking technical innovation with ethical and policy dimensions to assess AI’s tangible role in achieving humane, reproducible, and human-relevant biomedical research. This critical orientation establishes the conceptual and ethical framework for the sections that follow. We discuss the fundamentals of AI, machine learning, and deep learning and give concrete examples of how these tools are used in drug discovery, toxicology, disease modeling, and personalized medicine. Specifically, we examine validated case studies where AI models have replaced or reduced animal use and the integration of AI with new alternative methodologies (NAMs) such as organoids-on-chips and discuss the evolving regulatory aspects that now recognize AI-based evidence under acts such as the FDA Modernization Act 2.0 (Han, 2023). We reflect on the virtues and limitations of several methods of AI as well as future prospects for wider applications of AI in biomedicine with a need for strong validation, ethical protection, and vigorous cross-disciplinary research. With that in mind, this mini-review gives a balanced view on AI’s contributions to concerns over non-animal research methods with emphasis on its promise to accelerate discovery with high scientific and moral benchmarks (Bhardwaj et al., 2022; Kim et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2020; Akbarein et al., 2025).

2 Current role of animal models in biomedical research

Animal models are still playing a critical role in several areas of biomedical research through contributions to understanding complex biological processes and disease patterns. In drug discovery research, these animals are frequently used to determine the safety and efficacy of new compounds as a prerequisite for commencing human clinical trials (Abbas et al., 2024). Rodents such as mice and rats are often used due to short lifespans, ease of manipulating genes, and human-like physiologies. These models are especially worthwhile for multifactorial disorders such as cancer, diabetes, Alzheimer’s, and autoimmune diseases, when it would be impossible or unethical to conduct direct human research. The models of animal disease are also central to vaccine research: these are again applicable to defining immunogenicity and protection, assessing both antibody and cell-related responses as well as extent and duration of protection from infection.

Regulatory requirements often demand animal model results for approval of new drugs and devices (Galbreath et al., 2013). The requirements are to ensure product safety and performance prior to marketing release. Regulators such as the FDA and EMA insist on robust preclinical animal research as proof of new product safety and performance (McGonigle and Ruggeri, 2014). The research is required to be strict according to protocols in order to ensure result credibility as well as outcome reproducibility (Angius et al., 2012). The choice of suitable animal models and in vitro tests should be compatible with the device’s desired medical application (Anderson and Jiang, 2019). Although animal models have significantly contributed to biomedical science, limitations that result in a lack of reliable predictions of human outcome are becoming increasingly well appreciated.

3 Limitations of animal models

Despite this central role, the traditional reliance on animals is increasingly viewed as a scientific bottleneck rather than a universal standard. The predictive value of many animal models remains modest: between 50% and 70% of drug candidates demonstrating efficacy in animals ultimately fail in human trials (Hartung, 2024). Despite their widespread use, animal models have important limitations that can weaken their ability to predict human responses to drugs, chemicals, and other interventions. One major problem is species-specific differences that hinder clinical translation: physiological, metabolic, and genetic mismatches between animals and humans can change how a drug is processed, how targets are expressed, or how a disease develops, often leading to clinical trial failures even after promising preclinical animal results (Mukherjee et al., 2022). For example, the structural organization of the mouse immune system differs markedly from that of humans, which can make it hard to apply findings from murine studies to human disease contexts (Shi et al., 2019). Likewise, animal models may fail to reproduce key features of patient cells, their microenvironment, affected tissues or organs, or whole-organism physiology; even when outward disease traits look alike, the underlying molecular mechanisms frequently differ, widening the translational gap (Healy, 2018).

Ethical and welfare concerns are coming under closer scrutiny. More attention is being paid to welfare and ethics questions. The research use of animals is an issue that raises intense concern regarding causing distress to sensitive beings for human benefit, and it is deemed that animals must be shielded from unwarranted distress. Surveys of general opinion consistently point to strong opposition to invasive experiments or distressing and painful procedures.

Practical challenges exacerbate the issue: animal research is expensive and time-consuming. The operation and upkeep of animal facilities, breeding colonies, and conducting experiments require substantial resources, and several questions can take months or even years to complete while hampering discoveries of new treatment and diagnostic tools. Meanwhile, shifting societal opinions and increasingly prohibitive regulations are spurring movements to cut down, advance, and replace the utilization of animals for research purposes; several nations are implementing new bans and restrictions on some varieties of animal research.

Reproducibility introduces another dimension of concern: outcomes are subject to species or strain selection, research laboratory, or actual methods employed so that outcomes from different experiments become unreliable. All these issues—scientific, ethical, economic, and those of reproducibility—have created interest in alternatives that can be used to reduce utilization of animal models (Akhtar, 2015).

4 Emergence of artificial intelligence in biomedical research

Artificial intelligence is rapidly becoming a transformative force in biomedical science with prospects to accelerate discovery, increase efficiency, and reduce reliance on traditional animal models. AI is made up of algorithms and computer programs programmed to carry out tasks that would usually require human thought.

AI combines several computational methods that allow machines to learn from experience, predict things, and figure out puzzles (Owens et al., 2023). Machine learning, as part of AI, is concerned with formulating algorithms that derive knowledge from data without explicit programming. Machine learning’s deep subfield utilizes multilayered artificial neural networks to discern sophisticated patterns within data (Akinsulie et al., 2024). In healthcare, having no quantitative models available for applications like medical diagnostics is a significant challenge (Asan et al., 2020).

There are different types of AI models used in biomedical research—all with different abilities and applications. Supervised learning algorithms make predictions or classifications from labeled data that are inferred from them. On the other hand, unsupervised learning algorithms discover patterns and relationships within unlabeled data. Predictive modeling uses AI algorithms to predict future events from historical data (Manne and Kantheti, 2021). Natural language processing (NLP) makes it possible for the computer to understand and interpret human languages, facilitating text analysis and sentiment analysis. Generative models create new data that are similar to their input from training them, with prospects in drug design and image creation.

In the 3Rs community, the role of artificial intelligence is greater than that of simply automating; it is transforming by creating experiment alternatives driven by generated data that are traditionally used on animals. Machine-learning- and deep-learning-based algorithms can integrate genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and phenotypic datasets to create in silico biological networks that mimic human physiologic processes.

5 Applications of AI in the replacement of animal models

5.1 In silico drug discovery and toxicology

The discovery of drugs and toxicology are being transformed by AI through computer-generated (in silico) methods that forecast drug effectiveness as well as toxicity while minimizing animal testing requirements. Toxicological predictive models as well as quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) models exploit AI algorithms to forecast chemical toxicity based on molecular constitution. AI methods excel in pattern discovery, predictions, and manipulating big datasets (Olawade et al., 2023). AI-based toxicology models have demonstrated measurable success in substituting traditional animal assays. The DeepTox algorithm, trained on over 12,000 compounds, predicted chemical toxicity endpoints with an accuracy that equaled or exceeded rodent bioassay outcomes (Mayr et al., 2016). The Tox21 program, a collaboration among the U.S. EPA, NIH, and FDA, integrates machine learning with high-throughput in vitro screening to identify human-relevant toxicity pathways (Lynch et al., 2024). Similarly, the Virtual Liver Network reconstructs hepatotoxic mechanisms in silico, allowing for early identification of liver injury risks. These examples confirm that AI can reproduce core toxicological predictions at a fraction of the time, cost, and ethical burden of animal studies (Kuepfer et al., 2014). Virtual screening, for example, employs AI to evaluate vast compound libraries, pinpointing those with high target-binding potential (MacMath et al., 2023). AI also predicts drug–target interactions, aiding candidate identification and mechanism elucidation. Machine learning algorithms scrutinize massive databases to detect complex patterns, enabling the discovery of new therapeutic targets and the prediction of viable drug candidates more accurately and rapidly than traditional methods (Serrano et al., 2024). AI techniques show promise in discerning molecular signatures, identifying drug targets, and appraising therapeutic approaches (Nguyen et al., 2020). Generative adversarial networks are instrumental in designing novel molecules. AI platforms are developing new small-molecule treatments for various conditions, some aiming to replicate medicinal chemists’ decision-making while learning from their expertise (Jang, 2019).

5.2 Disease modeling and pathophysiology

AI also facilitates the creation of advanced disease models simulating human disease complexity, providing animal model alternatives. AI-enhanced organ-on-chip systems integrate microfluidics, cell cultures, and AI algorithms to produce realistic in vitro human organ replicas for studying disease mechanisms and drug efficacy. AI now enables the creation of digital twins, computational avatars that replicate organ or systemic disease progression using real patient data. Such models have been applied in oncology, neurodegeneration, and cardiometabolic disorders to predict responses that align more closely with human outcomes than with animal surrogates. Digital twins are virtual patient models amalgamating data from medical records, imaging, and genomics. AI algorithms analyze these data to predict disease trajectories and tailor treatments (Gangwal and Lavecchia, 2025a). AI proved useful for devising precision medicine approaches in cancer research through the use of algorithms to filter through large datasets, forecast medication reactions, and develop personalized therapy approaches. The AI models can accurately anticipate cancer patient outcomes, treatment effectiveness, and chance of survival while optimizing physician decision-making through the identification of patients who stand to gain from targeted therapy approaches (Maleki Varnosfaderani and Forouzanfar, 2024). The AI can determine high-dimensional data to narrow down diagnoses in many diseases.

5.3 Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics modeling

PK/PD modeling is improved with AI through the integration of information from multiple sources so that predictions become more accurate. Physiologically based PK models employ mathematical descriptions to describe the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of drugs. Their parameters are tuned with AI algorithms to build stronger predictive capacity. This contributes to personalized dosing design along with predictions of drug interactions. Computer platforms like ATOM and DeepChem employ deep learning so that lead compounds can be optimized without the use of animal experiments. Pharmacokinetic and toxicity simulations based on AI reduce traditional preclinical research on rodent as well as canine models (Serrano et al., 2024; Gangwal and Lavecchia, 2025b).

5.4 High-throughput omics data analysis

AI plays a central role in interpreting vast volumes of genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics data. AI detects biomarkers of disease risk, diagnosis, or therapy monitoring (Taherdoost and Ghofrani, 2024). In personalized therapy, AI examines genetic, demographic, and lifestyle information to provide personalized treatment recommendations (Li et al., 2024). Integrating AI with high-throughput omics data facilitates new biomarker identification, drug discovery, and personalized medicine design (Tariq, 2023). Machine learning algorithms for AI deal with massive amounts of high-throughput data, producing accurate diagnoses and becoming significant players in disease identification and prediction, presenting new healthcare viewpoints (Schork, 2019; Maleki Varnosfaderani and Forouzanfar, 2024). The emergence of AI in biomedical research is driven by machine learning’s rapid progress, increased computational power, and greater access to data (Schork, 2019; Briganti and Le Moine, 2020; Patel et al., 2020). The combination of AI with omics data enhances accuracy in classifying diseases and reveals new therapeutic agents, although some issues remain in multiomics/interomics analysis as well as a lack of algorithm availability (Patel et al., 2020). AI programs have the capacity to integrate vast knowledge bases with the potential to lower traditional practice-based false diagnoses and therapy mistakes (Serag et al., 2019). Health organizations are employing AI to discover latent patterns and to develop forecasting models for better decision support (Frey, 2018). Genomic medicine with AI supports improved patient attention [41]. Physicians are employing AI to make more informed decisions, automate workflows, and customize therapy to individual patients (Gala et al., 2024).

5.5 Clinical trial simulation and optimization

The emergence of artificial intelligence methods has made it possible for scientists to mimic clinical trials, modify design parameters, and predict likely outcomes (Huang et al., 2024). Machine learning can be used for predicting trial outcomes as well as finding patients who are most likely to comply with medication regimens, thus optimizing the duration and success rate of trials (Reis et al., 2025). The applications lead to compressed schedules and lower costs of drug discovery. By creating simulated populations and modeling for treatment responses, scientists can test many different trial situations and make choice-of-optimum strategies without having to implement actual research projects. It also reduces reliance on animal experiments as well as related expenses (Jha et al., 2023; Malik et al., 2024).

6 Advantages of AI over animal models

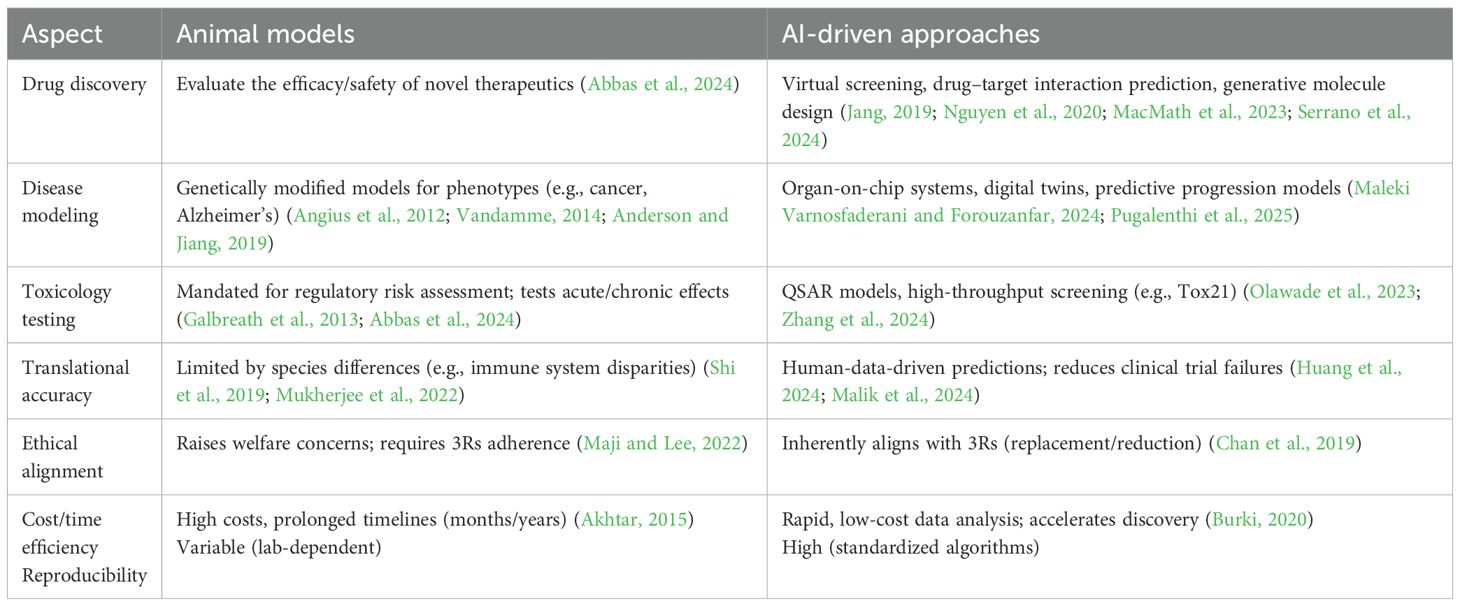

AI offers several clear advantages over animal models in biomedical research. It can improve the accuracy of predictions about human responses, which helps lower the risk of clinical trial failures. AI-driven predictive toxicology, for example, can assess chemical and drug safety more efficiently and reduce the need for animal testing while delivering more precise risk estimates (Abbas et al., 2024). Beyond that, AI aligns well with the 3Rs, speeds up analysis, cuts costs, and handles very large datasets, all of which can help reduce animal use and improve welfare standards (Chan et al., 2019). A comparative analysis of their roles in key biomedical domains is summarized in Table 1.

7 Integrating artificial intelligence with new alternative methodologies

Integration of AI with organoids, organs-on-chips (OoCs), and body-on-chips represents the next frontier in non-animal biomedical research. AI enhances these systems by processing high-dimensional biological readouts, imaging, transcriptomics, and electrophysiology to extract mechanistic insights and improve model validation. Recent evidence demonstrates the synergistic potential of AI integration with emerging new alternative methodologies. Deng et al. demonstrated that coupling AI with organs-on-chips enabled automated analysis of multiparametric physiological data, thereby improving model validation and facilitating regulatory evaluation (Deng et al., 2023). He reported that AI-organoid platforms significantly accelerated drug discovery by enhancing compound screening efficiency and reducing reliance on animal-based assays. Zushin et al. highlighted the U.S. FDA policy transition from regulatory animal testing and emphasized AI-facilitated NAMs’ ability to deliver human-relevant, policy-conforming data suitable for regulatory submission (Zushin et al., 2023). As a body of research, these studies as a whole individually provide robust evidence that AI-augmented NAMs are improved in terms of reproducibility, translational fidelity, and ethical sustainability, thus underscoring them for wider biomedical research mainstreaming as well as regulatory adoption.

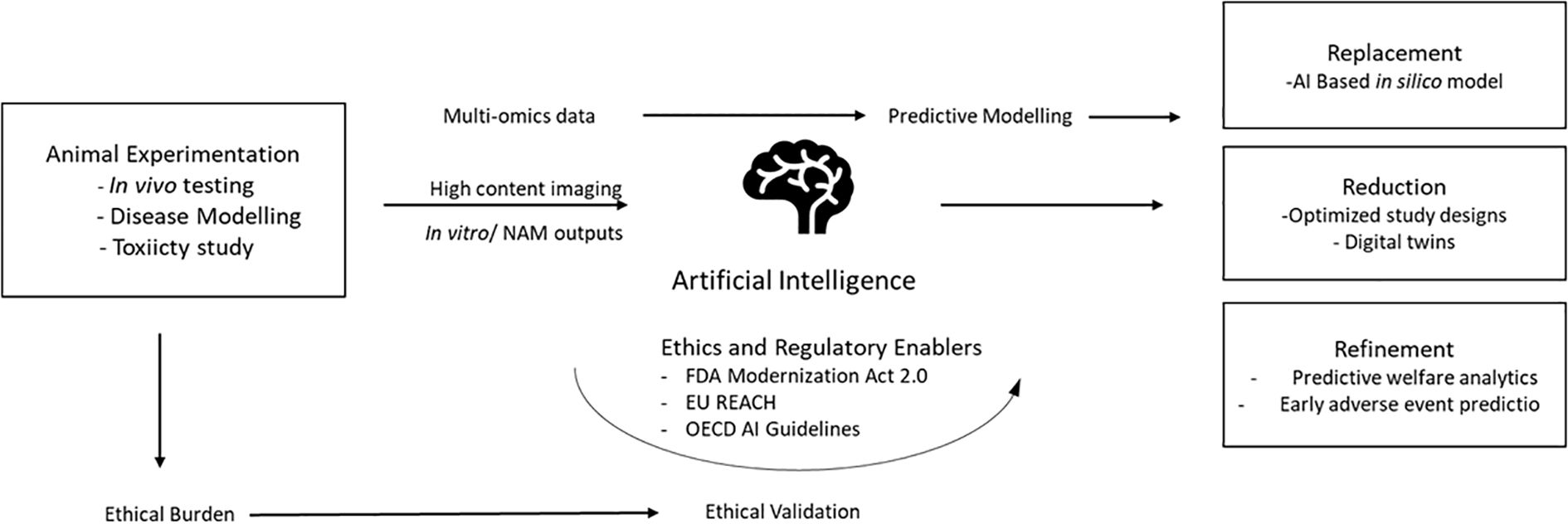

AI–3Rs interaction may be visualized as a looped back system with—i) input: multi-omics, images, and clinicals (human-relevant resources); ii) AI processing: algorithmic modeling with feature extraction for biological forecasting; iii) output: human-relevant safety or efficacy endpoints validated through NAMs; iv) feedback loop: regulatory benchmarking as well as ethical steering feedback to algorithm refinement (Figure 1). This model ensures that AI implementation not only replaces animal models but also enhances scientific thought itself, leading to ethically aligned innovation.

Figure 1. AI-driven transformation of the 3Rs framework in biomedical research: Artificial intelligence integrates data from in vitro, in silico, and clinical sources to create predictive models that emulate human biology. These models enable replacement (computational substitution of animal tests), reduction (optimized experimental design and digital twins), and refinement (improved welfare through predictive analytics). Regulatory frameworks such as the FDA Modernization Act 2.0 and EU REACH provide validation pathways that complete the ethical feedback loop toward humane, reproducible science. (NAMs, new alternative methodologies).

8 Ethical, regulatory, and policy dimensions

The possibility of AI-based non-animal methods depends not only on scientific validation but also on validation from regulators as well as policymakers. The past few years have witnessed rapid evolution in the acceptance of AI under the international biomedical regulatory system. The regulatory system of AI in biomedical research on a global scale is mentioned as follows:

8.1 The United States: FDA modernization and data-driven regulation

The FDA Modernization Act 2.0 (2023) is a landmark preclinical testing requirements reform in the United States. The act officially approves AI-dependent, in vitro, and in silico methods as scientifically qualified animal testing alternatives for drug safety and efficacy assessment. The regulatory shift from prescriptive animal data utilization to performance-based validation of predictive ability is a significant one. The United States National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) and Tox21 partnership have created AI-augmented testing pipelines that determine toxicity, metabolism, and pharmacodynamics with human-relevant datasets. The platforms yield regulatory-quality evidence of AI model prediction validity for decision support applications. Prominently, the FDA includes model transparency, explainability of algorithms, and origin of data as regulatory submission requirements, bringing 3Rs’ ethical principles up to date with AI innovation (Zushin et al., 2023).

8.2 Europe: European Medicines Agency and registration, evaluation, authorization, and restriction of chemical frameworks

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) published its AI roadmap (2025) as part of a complete vision to introduce responsible AI to life science-related drug manufacturing and pharmacovigilance. The roadmap highlights traceability, accountability, and human oversight to ensure that AI-driven decision-making is scientifically and ethically robust (Artificial intelligence workplan to guide use of AI in medicines regulation, 2023). Meanwhile, the European Union’s REACH (Registration, Evaluation, Authorization, and Restriction of Chemicals) legislation promotes AI-accelerated toxicity forecasting to reduce vertebrate testing (Hartung, 2019). The OECD Test Guidelines have been supplemented with computational validation modules, encouraging interoperability of AI algorithms with standardized toxicological endpoints. Together, these EU frameworks serve as an example of a unifying approach in which AI tools are harnessed as drivers of ethical science that unite the 3Rs in legislative and operational directives.

8.3 Asia and the global south: emerging adaptation

At the regional levels within Asia, interest in AI’s potential through regulatory means is gaining ground. India’s CCSEA (Committee for Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals) gives its approval to computational toxicology approaches in institutional animal ethics policies. South Korea and Japan also unveiled national AI platforms on chemical risk assessments that are based on non-animal models, aligning with those of OECD guidelines. The regional efforts are indicative of a future proactive conformity of AI adoption within welfare-based policy intents across regulatory jurisdictions.

8.4 International ethical frameworks: World Health Organization and United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization

In addition to technical vetting, appropriate utilization of AI in biomedical research is required to align with international norms of fairness, transparency, and accountability. The WHO (2024) and UNESCO (2023) have published AI ethics guidelines emphasizing human control, explainability, and fairness in scientific usage. When generalized to non-animal biomedical methods, such moral principles guarantee that innovation makes no compromise on inclusivity or integrity. They generalize then 3Rs philosophy originally developed within the animal welfare framework to a generic maxim of fair as well as responsible science.

8.5 Toward regulatory convergence

Even as subregional variations continue, confluence across the FDA, EMA, OECD, and WHO guidelines translates to a worldwide course for validation of data as the new gold standard for preclinical research. AI, when followed transparently and benchmarked independently, provides regulators with accuracy, reproducibility, and moral certainty to eschew conventional animal experiments. Further international cooperation, capacity building, and cross-sector communication will be required to translate these regulatory hopes into sustained practice.

9 Challenges and limitations of AI in biomedical research

Despite AI’s potential, several important challenges remain:

• Model validation and reproducibility: Reproducibility is once again the cornerstone of scientific dependability. However, AI models that are trained on heterogeneous data are typically context-dependent and variable and produce conflicting predictive results. Algorithmic structural variations, feature selection, and even variations in the preprocessing of data can produce conflicting results even when used on related biological problems. Establishing open validation pipelines is thus central. Cross-laboratory benchmarking, comparing AI results with standard in vitro as well as historical in vivo data, can give empirical evidence for predictive dependability. Pilot projects such as OECD’s AI Test Guideline Pilot as well as Tox21 validation schemes are central in ensuring algorithm reproducibility analogous to traditional bioassay reproducibility (Yeung, 2020).

● The “black box” problem: Many models, especially deep-learning models, are not interpretable, so clinicians cannot determine how decisions are reached and become distrustful and lose accountability. Techniques such as SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations) are increasingly utilized for justifying model output, highlighting biologically relevant features, and reducing algorithmic bias. Proper documentation of training datasets as well as model parameters is critical for scientific as well as ethical accountability (Hassija et al., 2024).

● Dependence on data quality: Good AI depends on big, well-annotated, high-quality datasets; noisier or low-quality datasets will produce non-trustworthy models. The creation of globally representative datasets through international collaboration is needed to enable generalizability. Data curation best practices from initiatives such as FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) principles aid transparency and help avoid duplication of efforts as well as cross-disciplinary interoperability (Wilkinson et al., 2016).

● Workflow integration. Integration of AI tools with research and clinical workflows is typically difficult and introduces resistance in everyday practice.

● Security and privacy risks: AI applications are vulnerable to cyberattacks and can facilitate fast collation of confidential patient information that escalates risks of data breach as well as unauthorized disclosure without patient approval as well as adequate control (Li et al., 2025).

● Ethical complexities: The ethics questions are those of data protection, informed consent for datasets of human origin, and algorithm fairness when predictive models are used to inform regulation or clinical decisions. There is a shared doctrine of ethics required for research that relies on AI so that scientific progress can be balanced with moral responsibility. While it comes with numerous prospects, AI also brings new challenges that require adapted regulatory and governance structures for biomedical applications (Jha et al., 2023; Morone et al., 2025).

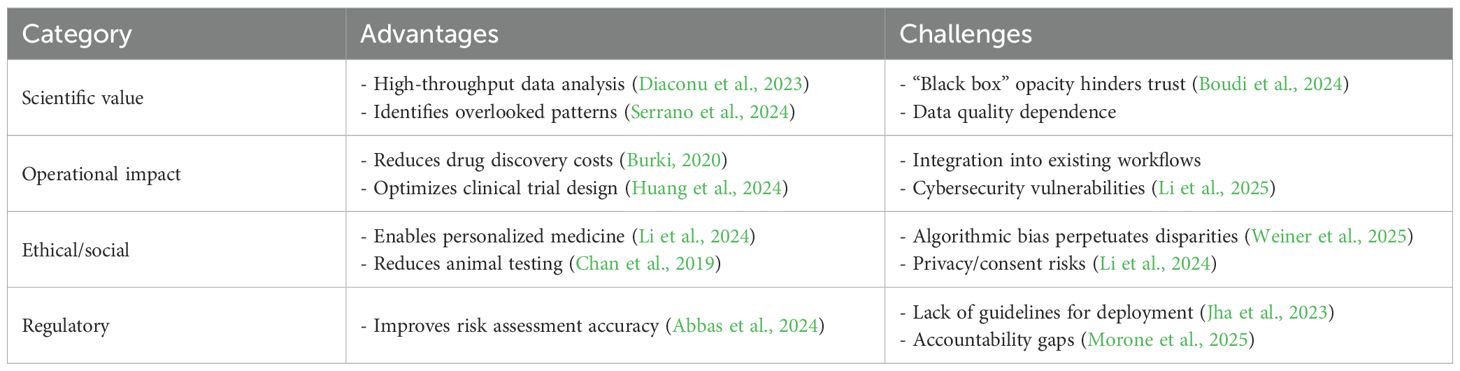

These trade-offs of benefits against unresolved questions of AI in biomedical studies are detailed in Table 2.

10 Future directions

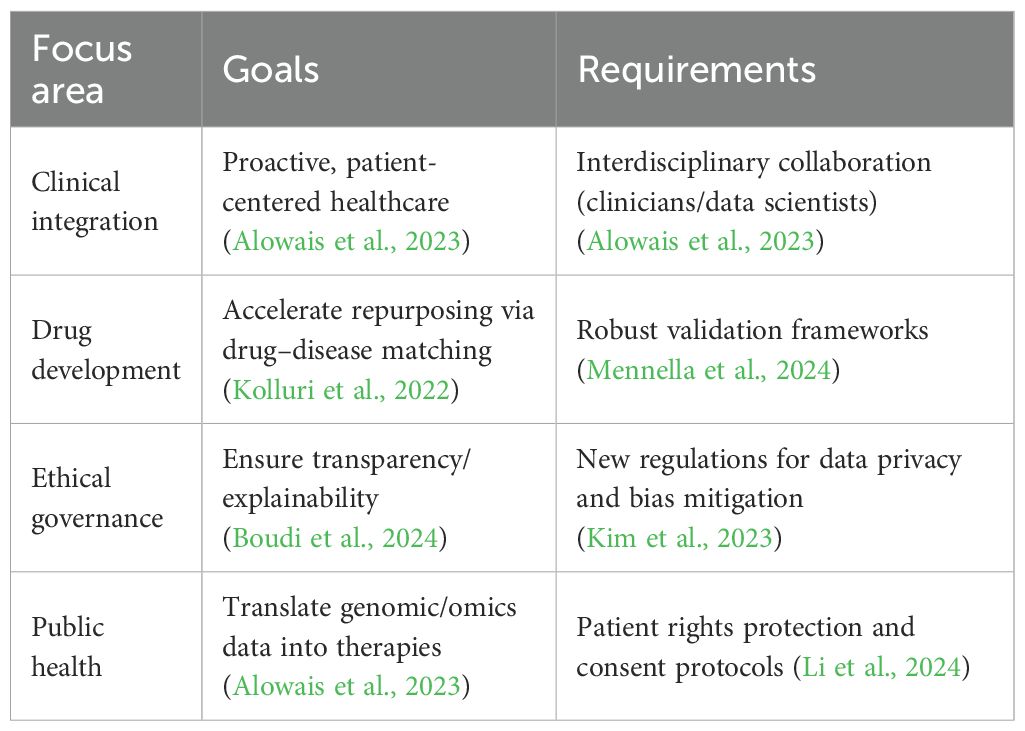

Biomedicine’s AI is moving fast, with new tools coming online regularly. As those methodologies mature, they are well-positioned to become increasingly powerful drivers of discovery and improved patient outcomes. Making that happen will require continued close collaboration among data scientists, clinicians, and bench researchers so that models address meaningful clinical problems and become part of practice. AI mines significant patient datasets to discover patterns to forecast personal disease risk. It can yield improved healthcare through the provision of accurate, up-to-date information to physicians. There are tools under development for diagnoses, treatment planning, and drug discovery (Maleki Varnosfaderani and Forouzanfar, 2024). The implementation of medical AI is highly promising but is awaited by healthcare policies in matters of ethics as well as finance (Iqbal et al., 2021). AI is going to revolutionize biomedical research with novel methods of understanding diseases, the discovery of drugs, and healthcare (Jeyaraman et al., 2023). It is transforming the delivery of healthcare and the clinician–patient relationship (Alanazi, 2023). To realize maximum potential for AI in healthcare, interdisciplinary collaboration, ethical principles, and patient protection are a necessity (Yelne et al., 2023). Future research needs to overcome AI’s limitations to ensure responsible and ethical use (Mennella et al., 2024; Uygun İLiKhan et al., 2024). Priority areas and implementation needs for future research are provided in Table 3.

11 Conclusion

In conclusion, AI has the potential to transform biomedical research through diminished dependence on animal models, faster drug discovery, improved disease modeling, and personalized medicine. Future undertakings should involve minimizing AI’s limitations to facilitate its ethical, responsible use toward human health improvement.

Author contributions

JS: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. AP: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. SH: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. MV: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abbas M. K. G., Rassam A., Karamshahi F., Abunora R., and Abouseada M. (2024). The role of AI in drug discovery. ChemBioChem 25, e202300816. doi: 10.1002/cbic.202300816

Akbarein H., Taaghi M. H., Mohebbi M., and Soufizadeh P. (2025). Applications and considerations of artificial intelligence in veterinary sciences: A narrative review. Veterinary Med. Sci. 11, e70315. doi: 10.1002/vms3.70315

Akhtar A. (2015). The flaws and human harms of animal experimentation. Camb Q Healthc Ethics 24, 407–419. doi: 10.1017/S0963180115000079

Akinsulie O. C., Idris I., Aliyu V. A., Shahzad S., Banwo O. G., Ogunleye S. C., et al. (2024). The potential application of artificial intelligence in veterinary clinical practice and biomedical research. Front. Vet. Sci. 11. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2024.1347550

Alanazi A. (2023). Clinicians’ Views on using artificial intelligence in healthcare: opportunities, challenges, and beyond. Cureus. doi: 10.7759/cureus.45255

Alowais S. A., Alghamdi S. S., Alsuhebany N., Alqahtani T., Alshaya A. I., Almohareb S. N., et al. (2023). Revolutionizing healthcare: the role of artificial intelligence in clinical practice. BMC Med. Educ. 23, 689. doi: 10.1186/s12909-023-04698-z

Anderson J. M. and Jiang S. (2019). ““Animal models in biomaterial development.,”,” in Encyclopedia of biomedical engineering. (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 237–241. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-801238-3.99882-9

Angius D., Wang H., Spinner R. J., Gutierrez-Cotto Y., Yaszemski M. J., and Windebank A. J. (2012). A systematic review of animal models used to study nerve regeneration in tissue-engineered scaffolds. Biomaterials 33, 8034–8039. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.07.056

Asan O., Bayrak A. E., and Choudhury A. (2020). Artificial intelligence and human trust in healthcare: focus on clinicians. J. Med. Internet Res. 22, e15154. doi: 10.2196/15154

(2023). Artificial intelligence workplan to guide use of AI in medicines regulation (European Medicines Agency (EMA). Available online at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/artificial-intelligence-workplan-guide-use-ai-medicines-regulation (Accessed October 19, 2025).

Bhardwaj A., Kishore S., and Pandey D. K. (2022). Artificial intelligence in biological sciences. Life 12, 1430. doi: 10.3390/life12091430

Boudi A. L., Boudi M., Chan C., and Boudi F. B. (2024). Ethical challenges of artificial intelligence in medicine. Cureus. doi: 10.7759/cureus.74495

Briganti G. and Le Moine O. (2020). Artificial intelligence in medicine: today and tomorrow. Front. Med. 7. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00027

Burki T. (2020). A new paradigm for drug development. Lancet Digital Health 2, e226–e227. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30088-1

Chan H. C. S., Shan H., Dahoun T., Vogel H., and Yuan S. (2019). Advancing drug discovery via artificial intelligence. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 40, 592–604. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2019.06.004

Deng S., Li C., Cao J., Cui Z., Du J., Fu Z., et al. (2023). Organ-on-a-chip meets artificial intelligence in drug evaluation. Theranostics 13, 4526–4558. doi: 10.7150/thno.87266

Diaconu C., State M., Birligea M., Ifrim M., Bajdechi G., Georgescu T., et al. (2023). The role of artificial intelligence in monitoring inflammatory bowel disease—The future is now. Diagnostics 13, 735. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics13040735

Doke S. K. and Dhawale S. C. (2015). Alternatives to animal testing: A review. Saudi Pharm. J. 23, 223–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2013.11.002

Frey L. J. (2018). Artificial intelligence and integrated genotype–phenotype identification. Genes 10, 18. doi: 10.3390/genes10010018

Gala D., Behl H., Shah M., and Makaryus A. N. (2024). The role of artificial intelligence in improving patient outcomes and future of healthcare delivery in cardiology: A narrative review of the literature. Healthcare 12, 481. doi: 10.3390/healthcare12040481

Galbreath E. J., Pinkert C. A., Bolon B., and Morton D. (2013). ““Genetically engineered animals in product discovery and development.,”,” in Haschek and rousseaux’s handbook of toxicologic pathology (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 405–460. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-415759-0.00012-1

Gangwal A. and Lavecchia A. (2025a). Artificial intelligence in preclinical research: enhancing digital twins and organ-on-chip to reduce animal testing. Drug Discov. Today 30, 104360. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2025.104360

Gangwal A. and Lavecchia A. (2025b). Artificial intelligence in preclinical research: enhancing digital twins and organ-on-chip to reduce animal testing. Drug Discov. Today 30, 104360. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2025.104360

Han J. J. (2023). FDA Modernization Act 2.0 allows for alternatives to animal testing. Artif. Organs 47, 449–450. doi: 10.1111/aor.14503

Hartung T. (2019). Predicting toxicity of chemicals: software beats animal testing. EFS2 17. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2019.e170710

Hartung T. (2024). The (misleading) role of animal models in drug development. Front. Drug Discov. 4. doi: 10.3389/fddsv.2024.1355044

Hassija V., Chamola V., Mahapatra A., Singal A., Goel D., Huang K., et al. (2024). Interpreting black-box models: A review on explainable artificial intelligence. Cognit. Comput. 16, 45–74. doi: 10.1007/s12559-023-10179-8

Healy K. (2018). Tissue-engineered disease models. Nat. BioMed. Eng. 2, 879–880. doi: 10.1038/s41551-018-0339-2

Huang K. A., Choudhary H. K., and Kuo P. C. (2024). Artificial intelligent agent architecture and clinical decision-making in the healthcare sector. Cureus. doi: 10.7759/cureus.64115

Iqbal S., Ahmad S., Akkour K., Wafa A. N. A., AlMutairi H. M., and Aldhufairi A. M. (2021). Review article: impact of artificial intelligence in medical education. MedEdPublish 10. doi: 10.15694/mep.2021.000041.1

Jang I.-J. (2019). Artificial intelligence in drug development: clinical pharmacologist perspective. Transl. Clin. Pharmacol. 27, 87. doi: 10.12793/tcp.2019.27.3.87

Jeyaraman M., Balaji S., Jeyaraman N., and Yadav S. (2023). Unraveling the ethical enigma: artificial intelligence in healthcare. Cureus. doi: 10.7759/cureus.43262

Jha D., Durak G., Sharma V., Keles E., Cicek V., Zhang Z., et al. (2023). A conceptual algorithm for applying ethical principles of AI to medical practice. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2304.11530

Kendall L. V., Owiny J. R., Dohm E. D., Knapek K. J., Lee E. S., Kopanke J. H., et al. (2018). Replacement, refinement, and reduction in animal studies with biohazardous agents. ILAR J. 59, 177–194. doi: 10.1093/ilar/ily021

Kim H., Kim E., Lee I., Bae B., Park M., and Nam H. (2020). Artificial intelligence in drug discovery: A comprehensive review of data-driven and machine learning approaches. Biotechnol. Bioproc E 25, 895–930. doi: 10.1007/s12257-020-0049-y

Kim J., Koo B.-K., and Knoblich J. A. (2020). Human organoids: model systems for human biology and medicine. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 571–584. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-0259-3

Kim M., Sohn H., Choi S., and Kim S. (2023). Requirements for trustworthy artificial intelligence and its application in healthcare. Healthc Inform Res. 29, 315–322. doi: 10.4258/hir.2023.29.4.315

Kolluri S., Lin J., Liu R., Zhang Y., and Zhang W. (2022). Machine learning and artificial intelligence in pharmaceutical research and development: a review. AAPS J. 24, 19. doi: 10.1208/s12248-021-00644-3

Kuepfer L., Kerb R., and Henney A. (2014). Clinical translation in the virtual liver network. CPT Pharmacom Syst. Pharma 3, 1–4. doi: 10.1038/psp.2014.25

Li Y.-H., Li Y.-L., Wei M.-Y., and Li G.-Y. (2024). Innovation and challenges of artificial intelligence technology in personalized healthcare. Sci. Rep. 14, 18994. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-70073-7

Li D. M., Parikh S., and Costa A. (2025). A critical look into artificial intelligence and healthcare disparities. Front. Artif. Intell. 8. doi: 10.3389/frai.2025.1545869

Lynch C., Sakamuru S., Ooka M., Huang R., Klumpp-Thomas C., Shinn P., et al. (2024). High-throughput screening to advance in vitro toxicology: accomplishments, challenges, and future directions. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 64, 191–209. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-112122-104310

MacMath D., Chen M., and Khoury P. (2023). Artificial intelligence: exploring the future of innovation in allergy immunology. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 23, 351–362. doi: 10.1007/s11882-023-01084-z

Maji S. and Lee H. (2022). Engineering hydrogels for the development of three-dimensional in vitro models. IJMS 23, 2662. doi: 10.3390/ijms23052662

Maleki Varnosfaderani S. and Forouzanfar M. (2024). The role of AI in hospitals and clinics: transforming healthcare in the 21st century. Bioengineering 11, 337. doi: 10.3390/bioengineering11040337

Malik S., Muhammad K., and Waheed Y. (2024). Artificial intelligence and industrial applications-A revolution in modern industries. Ain Shams Eng. J. 15, 102886. doi: 10.1016/j.asej.2024.102886

Manne R. and Kantheti S. C. (2021). Application of artificial intelligence in healthcare: chances and challenges. CJAST 40 (6), 78–89. doi: 10.9734/cjast/2021/v40i631320

Mayr A., Klambauer G., Unterthiner T., and Hochreiter S. (2016). DeepTox: toxicity prediction using deep learning. Front. Environ. Sci. 3. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2015.00080

McGonigle P. and Ruggeri B. (2014). Animal models of human disease: Challenges in enabling translation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 87, 162–171. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.08.006

Mennella C., Maniscalco U., De Pietro G., and Esposito M. (2024). Ethical and regulatory challenges of AI technologies in healthcare: A narrative review. Heliyon 10, e26297. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e26297

Morone G., De Angelis L., Martino Cinnera A., Carbonetti R., Bisirri A., Ciancarelli I., et al. (2025). Artificial intelligence in clinical medicine: a state-of-the-art overview of systematic reviews with methodological recommendations for improved reporting. Front. Digit Health 7. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2025.1550731

Mukherjee P., Roy S., Ghosh D., and Nandi S. K. (2022). Role of animal models in biomedical research: a review. Lab. Anim. Res. 38, 18. doi: 10.1186/s42826-022-00128-1

Nguyen T. T., Nguyen Q. V. H., Nguyen D. T., Yang S., Eklund P. W., Huynh-The T., et al. (2020). Artificial intelligence in the battle against coronavirus (COVID-19): A survey and future research directions. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2008.07343

Olawade D. B., Wada O. J., David-Olawade A. C., Kunonga E., Abaire O., and Ling J. (2023). Using artificial intelligence to improve public health: a narrative review. Front. Public Health 11. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1196397

Owens A., Vinkemeier D., and Elsheikha H. (2023). A review of applications of artificial intelligence in veterinary medicine. Companion Anim. 28, 78–85. doi: 10.12968/coan.2022.0028a

Patel S. K., George B., and Rai V. (2020). Artificial intelligence to decode cancer mechanism: beyond patient stratification for precision oncology. Front. Pharmacol. 11. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.01177

Pugalenthi L. S., Garapati C., Maddukuri S., Kanwal F., Kumar J., Asadimanesh N., et al. (2025). From data to decisions: AI in varicose veins—Predicting, diagnosing, and guiding effective management. JVD 4, 19. doi: 10.3390/jvd4020019

Reis Z. S. N., Pereira G. M. V., Dias C. D. S., Lage E. M., De Oliveira I. J. R., and Pagano A. S. (2025). Artificial intelligence-based tools for patient support to enhance medication adherence: a focused review. Front. Digit Health 7. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2025.1523070

Schork N. J. (2019). ““Artificial intelligence and personalized medicine.,”,” in Precision medicine in cancer therapy. Cancer treatment and research. Eds. Von Hoff D. D. and Han H. (Springer International Publishing, Cham), 265–283. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-16391-4_11

Serag A., Ion-Margineanu A., Qureshi H., McMillan R., Saint Martin M.-J., Diamond J., et al. (2019). Translational AI and deep learning in diagnostic pathology. Front. Med. 6. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2019.00185

Serrano D. R., Luciano F. C., Anaya B. J., Ongoren B., Kara A., Molina G., et al. (2024). Artificial intelligence (AI) applications in drug discovery and drug delivery: revolutionizing personalized medicine. Pharmaceutics 16, 1328. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics16101328

Shi D., Mi G., Wang M., and Webster T. J. (2019). In vitro and ex vivo systems at the forefront of infection modeling and drug discovery. Biomaterials 198, 228–249. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.10.030

Taherdoost H. and Ghofrani A. (2024). AI’s role in revolutionizing personalized medicine by reshaping pharmacogenomics and drug therapy. Intelligent Pharm. 2, 643–650. doi: 10.1016/j.ipha.2024.08.005

Tariq Z. (2023). Integrating artificial intelligence and humanities in healthcare. doi: 10.48550/ARXIV.2302.07081

Uygun İLiKhan S., Özer M., Tanberkan H., and Bozkurt V. (2024). How to mitigate the risks of deployment of artificial intelligence in medicine? Turkish J. Med. Sci. 54, 483–492. doi: 10.55730/1300-0144.5814

Vandamme T. (2014). Use of rodents as models of human diseases. J. Pharm. Bioall Sci. 6, 2. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.124301

Weiner E. B., Dankwa-Mullan I., Nelson W. A., and Hassanpour S. (2025). Ethical challenges and evolving strategies in the integration of artificial intelligence into clinical practice. PloS Digit Health 4, e0000810. doi: 10.1371/journal.pdig.0000810

Wilkinson M. D., Dumontier M., Aalbersberg I., Appleton G., Axton M., Baak A., et al. (2016). The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci. Data 3, 160018. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2016.18

Yelne S., Chaudhary M., Dod K., Sayyad A., and Sharma R. (2023). Harnessing the power of AI: A comprehensive review of its impact and challenges in nursing science and healthcare. Cureus. doi: 10.7759/cureus.49252

Yeung K. (2020). Recommendation of the council on artificial intelligence (OECD). Int. leg mater 59, 27–34. doi: 10.1017/ilm.2020.5

Zhang X., Zhang D., Zhang X., and Zhang X. (2024). Artificial intelligence applications in the diagnosis and treatment of bacterial infections. Front. Microbiol. 15. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2024.1449844

Keywords: 3Rs, artificial intelligence, preclinical studies, animal models, new alternative methodologies

Citation: Sandhu JS, Parida A, Hegde S and V. M (2025) Artificial intelligence in biomedical research: advancing non-animal methodologies. Front. Anim. Sci. 6:1687111. doi: 10.3389/fanim.2025.1687111

Received: 16 August 2025; Accepted: 31 October 2025;

Published: 09 December 2025.

Edited by:

Inimary Toby-Ogundeji, University of Dallas, United StatesReviewed by:

Sweet Naskar, Department of Health and Family Welfare, IndiaNitish Bhatia, Vishwakarma University, India

Copyright © 2025 Sandhu, Parida, Hegde and V. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Amrita Parida, YW1yaXRhLnBhcmlkYUBtYW5pcGFsLmVkdQ==

Jagnoor Singh Sandhu

Jagnoor Singh Sandhu Amrita Parida

Amrita Parida Shreya Hegde

Shreya Hegde Manju V.4

Manju V.4