- 1Department of Animal Science, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, United States

- 2Department of Animal and Veterinary Sciences, Scotland’s Rural College, Easter Bush, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

Introduction: This study explores the Precision Livestock Farming (PLF) technology perceptions and data needs of off-farm swine industry stakeholders. The aim was to increase our understanding of PLF’s real-world applicability beyond farm operations.

Methods: Using focus group discussions, five professionals—spanning government official, animal scientists, food processors, and retail representatives—offered insights on ideal data types and practical concerns associated with PLF adoption. Using the Nominal Group Technique (NGT), we determined that participants have unique data needs, with no clear consensus on data priorities for PLF. We conducted a second focus group following normal focus group protocols, allowing us to further explore participants’ PLF priorities, nuanced perspectives, and shared beliefs.

Results and discussion: We identified five themes: “To Split the Check or Not to Split the Check; Knowing the Benefits is Key; Reconciling Profit and Welfare in PLF; What Use is PLF to the Animal Anyway? and The Value and Caveats of PLF Data. The benefits of PLF data to participants were closely tied to clear cost-sharing structures, meaningful benefits for diverse stakeholders, and assurances about data control. Stakeholders voiced concerns around financial feasibility, ethical implications, and practical barriers in terms of data management. Overall, addressing these complex but interrelated needs and concerns by other stakeholders can make data generated by PLF useful beyond the farm and provide additional incentives to advance PLF adoption in the swine industry. This finding may provide actionable insights to inform strategies that support both the technological advancement and ethical sustainability of PLF in animal agriculture.

1 Introduction

The pork production industry functions through a complex network of interconnected stakeholders, all of whom contribute to maintaining the supply chain’s production, profitability, and viability. From the care and management of pigs to the final consumption of pork products, the industry’s success depends on the collective efforts of producers, veterinarians, regulatory agencies, haulers, food processors, retailers, and consumers. Precision livestock farming (PLF) technologies are potential solutions to challenges faced by the pork by industry through enhancing efficiency, profitability, and sustainability from on farm animal care to addressing consumer concerns such as transparency, traceability, and food safety.

1.1 Background

Producers—farm owners, farm managers, and animal caretakers—are the backbone of pork production, with responsibilities beyond simply raising pigs. They are tasked with meeting society’s increasing expectations for food safety, animal welfare, and environmental stewardship. As sustainable livestock production gains more focus, there is a growing need for integrated management practices that not only deliver safe, healthy products but also improve animal care and protect the environment (Makkar, 2016; Perry et al., 2005; Salmon et al., 2018). PLF technologies can help producers collect and analyze real-time data from individual animals and herds, leading to better disease prevention, individualized animal care, and increased farm productivity (Tullo et al., 2019).

1.2 Potential benefits of PLF to government, processors, retailers, and consumers

Government regulatory agencies play a crucial role in disease monitoring and stand to gain significantly from PLF technologies because these systems enhance their capacity to oversee, detect, and respond to disease outbreaks through continuous, non-invasive health monitoring (Vranken and Berckmans, 2017). PLFs such as microphones, accelerometers and infrared cameras enable early detection of illness, such as coughing, abnormal movements or changes in body temperature, even before visible symptoms appear (Van Hirtum and Berckmans, 2002; Aerts et al., 2005). This early detection supports surveillance that can track and reduce the spread of highly infectious viral diseases such as Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome virus (Garrido et al., 2023; Martínez-Avilés et al., 2017). Empirical study has shown that data-driven methodologies play a crucial role in monitoring, modeling, and managing infectious disease spread (Alamo et al., 2021). In swine production specifically, PLF offers potential benefits for identifying problems such as tail biting, aggression, and poor air quality, all of which have major implications for pig welfare and farm economics (Blokhuis et al., 2003; Ortega et al., 2011; Grunert et al., 2018; Alonso et al., 2020). Tail biting, for example, drastically reduces pigs’ welfare (Munsterhjelm et al., 2013; Turner et al., 2017) and leads to substantial economic losses due to carcass condemnations, veterinary treatments, and reduced performance (D’Eath et al., 2016).

Beyond the farm, food processors and retailers are responsible for ensuring that pork products meet regulatory standards and satisfy consumer demands. These stakeholders are concerned with food safety, traceability, animal welfare, and responsible antibiotic use, which impact public health and the marketability of pork products. PLF technologies could help processors and retailers meet rigorous regulatory requirements and consumer expectations by providing real-time monitoring of animals’ responses (Norton and Berckmans, 2017). As consumer awareness of welfare and environmental issues grows, retailers must ensure that animals are raised under humane conditions while minimizing the environmental impact of production (Nicolaisen et al., 2023). Consumers increasingly expect transparency regarding production systems, welfare outcomes, and environmental impacts; PLF-generated data can help address these concerns by providing verifiable, welfare-relevant information throughout the supply chain (Blokhuis et al., 2003; Grunert et al., 2018). In particular, public demand for clear welfare assurances has motivated interest in product labelling systems that communicate husbandry conditions and production standards (Blokhuis et al., 2003). Health and welfare metrics obtained with PLF technologies could also address consumer concerns by providing transparency throughout the production process, fostering greater consumer trust in producers’ care of their animals.

At the regulatory level, government agencies tasked with enforcing food safety, animal welfare, and environmental sustainability standards could also leverage PLF technologies. These systems generate detailed records of animals’ production history, that can help in enforcing compliance with regulatory standards and protecting public health (Rowe et al., 2019). PLF also supports traceability, enabling government authorities to track pig movements and verify that pork products meet quality and safety standards at every stage of the supply chain. This is especially important for disease prevention and food safety, as traceability systems can alert both producers and regulators to potential problems before they escalate (Tyris et al., 2022). PLF decision-support tools can also enable real-time monitoring by government agencies and veterinarians—for example, through automated alerts for abnormal behavioral or physiological patterns, environmental deviations, or disease indicators—thereby strengthening surveillance and rapid response capacity (Tedeschi et al., 2021; Panda et al., 2024; Saro et al., 2024). Moreover, PLF systems can help government agencies promote environmental sustainability by improving resource management and reducing waste. For example, optimizing heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems in swine barns can reduce energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions, contributing to the overall sustainability of pork production (Winkel et al., 2015).

1.3 Potential risks and concerns of PLF technologies

While PLF technologies offer notable advantages, several concerns remain regarding their impact on animal care. As Dawkins (2021) and Tuyttens et al. (2022) note, PLF may encourage larger, more densely stocked farms by improving efficiency, but this shift often prioritizes group-level monitoring over individual welfare. Because animal welfare is fundamentally an individual experience, systems that treat animals uniformly risk overlooking variability and unique needs (Reimert et al., 2023; Richter and Hintze, 2019). Economic benefits, such as reduced labor and cost-effectiveness for large-scale farms, may also compromise welfare by restricting natural behaviors (Tuyttens et al., 2022). Interaction with land-based robots presents another issue. Bovo et al. (2024) found that such technologies can trigger stress responses if animals perceive them as threats. They recommend that robots be designed to move fluidly and use signals animals can interpret without fear. Moreover, direct contact with PLF hardware can unintentionally alter animal behavior.

PLF algorithms often struggle with real-world variability. False negatives (where indicators are missed) and false positives (where random patterns are misread) are common and undermine reliability (Hurník et al., 2021; Eagan and Protopopova, 2022; Wolf et al., 2023). Technical malfunctions—including power failures and environmental interference—further compromise system performance (Tuyttens et al., 2022). Poorly designed systems may also provoke aggression, as seen in electronic feeders with limited access points, which can increase competition and fear among socially subordinate animals (Paul and Serpell, 1993; Remience et al., 2008). PLF’s reduction of human labor may weaken the human-animal bond. Fewer staff or larger herds could reduce meaningful interactions, diminishing caretakers’ observational skills and shifting the workforce towards technology over animal care (Paul and Serpell, 1993; Winsten et al., 2010; Bjerke et al., 2021). As farms evolve to fit PLF systems, there is a risk that management and housing will prioritize system compatibility over welfare. These trends raise ethical concerns that must be addressed to ensure PLF technologies enhance productivity without compromising animal well-being.

1.4 Bridging the gap between PLF potential and off-farm stakeholder’s needs

In contrast to previous studies that have explored the potential benefits of PLF technologies across various domains of pork production, this study offers a unique perspective by focusing on the real-world applicability and stakeholder perceptions of PLF within the swine industry. Rather than emphasizing technical capabilities alone, this study looked at the specific data needs, economic constraints, and stakeholder concerns for users beyond the farm. Using focus group discussions, the current study provides insights into what producers, government regulatory agencies, food processors, retailers, and a representative of consumer advocacy group deem critical for adopting PLF technologies. By capturing these perspectives, this study helps bridge the gap between theoretical benefits of PLF and practical challenges of its implementation, particularly in terms of economic feasibility and stakeholder willingness to invest in these innovations.

Specifically, we aim to address the following: 1) What ideal data do off-farm stakeholders desire (ignoring constraints of cost or labor)? 2) How aware are stakeholders of PLF technologies and their application in swine farming? 3) Who will be willing to pay for PLF that improves pig welfare and productivity, and under what conditions? 4) How can PLF technologies be marketed to encourage adoption while addressing key concerns such as pig welfare, economic viability, and worker conditions? Understanding off-farm stakeholder perspectives is crucial, especially since farmers primarily adopt PLF technologies to improve animal health, reduce labor demands, and enhance production efficiency under increasing economic and regulatory pressure (Wathes et al., 2008). Through these questions, the study seeks to provide actionable insights that will inform future development and adoption strategies for PLF in the pork production industry.

2 Methods

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Michigan State University Institutional Review Board (IRB), with the study categorized as exempt under 45 CFR 46.104(d) 2i (Study ID: STUDY00005432). This exemption relates to research where the information obtained is recorded by the investigator in such a manner that the identity of the human subjects cannot be ascertained directly through identifiers linked to the subjects.

2.1 Description of study participants

Five individuals participated in the two focus group discussion sessions, with three attending in person and two joining online via the Zoom platform. The sample size of 5 participants that participated in the focus group discussion in the present study is consistent with the general design of NGT studies, which prioritize depth and structured consensus over large sample sizes (Delbecq et al., 1975). Participants were selected based on their direct relevance to swine industry policymaking, regulation, and animal welfare—not as general representatives of all key stakeholders within the swine industry. A non-probability sampling approach was used, specifically purposive sampling, to ensure that all participants had demonstrable expertise and experience related to the swine industry, PLF, and/or pig health and welfare.

One participant worked in a food processing organization, ensuring compliance with animal care, biosecurity, and program standards while also serving as an educational resource for their organization, suppliers, and customers. Another was active in government affairs and food and agricultural policy for natural grocery associations, focusing on food, agriculture, nutrition, rural economic development, technology, and health. They were involved in trade advocacy, oversee organic certification, and advised start-ups in food and agriculture technology. The third participant was an animal scientist specializing in animal behavior and welfare, particularly for pigs and cattle. Their work explores new welfare indicators using machine learning and sensor technologies and how animal products can be labelled to highlight these attributes. The fourth participant had expertise in animal welfare and veterinary medicine, offering advisory services to a national board in the USA and contributing to outreach and educational initiatives. The fifth participant held a senior position within a state agriculture department, overseeing animal industry regulations and was trained as a veterinarian specializing in preventive medicine, with extensive experience in enforcing regulatory compliance and leading national disease prevention programs. This unique group brought a range of expertise in animal welfare, animal health, agriculture, and regulatory compliance to the sessions.

The participants were chosen based on their knowledge of and engagement with the swine industry. Although they were not direct PLF users, their expertise in animal husbandry, technologies, their professional connections, and familiarity with practices within the pig farming industry meant they could offer valuable insights into the potential benefits of PLF. The NGT process fostered collaboration, giving all participants an opportunity to contribute ideas and set priorities regarding the ideal PLF data. Importantly, one participant represented the interests of consumers and grocery associations, offering a voice that reflected consumer concerns related to food transparency, welfare, and sustainability.

2.2 Nominal group technique procedure

The Nominal Group Technique (NGT) was employed in this study to evaluate the relevance of PLF data for key off-farm stakeholders. This focused sample of expert stakeholders each brought a distinct and relevant perspective on PLF applications in an attempt to begin understanding the needs of the broader swine industry which encompasses many diverse off farm groups. Specifically, the participants were asked to consider what data, without constraints (e.g., economic or labor limitations) would be their ideal or dream data to capture. NGT was therefore used to identify if and where consensus existed in terms of what the participants identified as their “dream data.” Originally developed in the 1960s as a formal method to support decision-making in social psychological research (Van de Ven and Delbecq, 1972), NGT has since been widely applied in various fields, including education and health (Delbecq et al., 1975). Participants were recruited based on their expertise in swine production policy, animal welfare science, veterinary regulation, consumer advocacy, and food safety—representing roles in the swine industry that directly influence or are influenced by PLF decisions.

Focus Group Session 1: NGT Protocols: A Step-by-Step Approach

Two focus group sessions were conducted with the same participants. The first session employed the NGT, while the second followed a traditional focus group structure with open-ended questions and facilitated discussion (Krueger and Casey, 2015). The NGT session was conducted in a hybrid format, accommodating both in-person and remote participants, and lasted several hours, exceeding standard focus group durations. This allowed for in-depth discussion and prioritization, despite a small sample size.

The NGT protocol followed established methodological guidelines and was developed by a multidisciplinary research team with expertise in animal welfare, behavior, agricultural economics, psychology, sociology, and veterinary medicine. The session began with individual silent idea generation in response to four pre-determined questions (see Section 1.4). Participants recorded their ideas on separate sticky notes. This approach was designed to mitigate production blocking and dominance effects (Hugé and Mukherjee, 2018).

Ideas were shared in a structured round-robin format, with the moderator collecting and displaying responses for group visibility. Remote participants submitted ideas via Zoom, which were transcribed by the research team. Clarification and elaboration of ideas followed, and the moderator facilitated balanced participation by postponing evaluative discussion until all ideas were presented. Once all contributions were collected, participants engaged in clarification and group discussion.

Participants then individually ranked their top four priorities per question. A re-ranking opportunity was provided after the discussion to identify any emerging consensus regarding the most valued PLF data. While some overlapping priorities emerged, full consensus was not achieved. To avoid introducing group pressure or forcing agreement, the ranking phase was not extended.

Focus Group Session 1: Data Handling and Analysis

The session was recorded and transcribed using Otter© and Microsoft Word©, with transcripts validated against audio recordings. Transcripts were imported into NVivo (Version 1.7, QSR International) for organization and data management. Sticky note photographs were also used to cross-reference verbal explanations with participants’ written responses. Transcripts were not coded for content in this session, as the primary output was the ranked list of priorities derived through the NGT process.

Focus Group Session 2: Traditional FG Approach

Following a short break, a second focus group session was conducted using a traditional open-format discussion. Moderators employed standard focus group techniques, including the use of structured prompts, follow-up questions, and turn-taking facilitation, to encourage participant engagement and maintain topic relevance. The aim of this session was to explore broader perceptions of PLF technologies, including perceived benefits, barriers, and stakeholder concerns.

Focus Groups Analysis

The second session was recorded and transcribed following the same procedures as the first. Reflexive Thematic Analysis (RTA) was applied to analyze the discussion content, following Braun and Clarke (2021a; 2022) framework. A deductive coding strategy was initially used, informed by predefined topical categories relevant to the study’s research questions (e.g., PLF data, economics, animal welfare, consumer perspectives). These were applied flexibly and refined throughout the analysis.

Subsequently, inductive coding was conducted to capture emergent themes beyond the initial framework. The analysis was guided by a social constructivist perspective, recognizing the interplay between individual experience and broader societal narratives (Berger and Luckmann, 1967). Reflexivity was maintained throughout the analysis process, including the use of a reflexive journal to document decisions and emergent insights. The primary analyst (LJ), a psychologist with qualitative research training, collaborated with an agricultural economist (BEA) to validate theme development and interpretation.

All codes and themes were iteratively reviewed and refined to ensure conceptual clarity and alignment with the dataset. While inter-rater reliability was not used, consistent with RTA’s interpretivist stance (Braun and Clarke, 2021b, 2022), collaborative review ensured analytical rigor. The six steps of analysis followed in this study are summarized in Figure 1.

3 Results

3.1 Focus group session 1 NGT

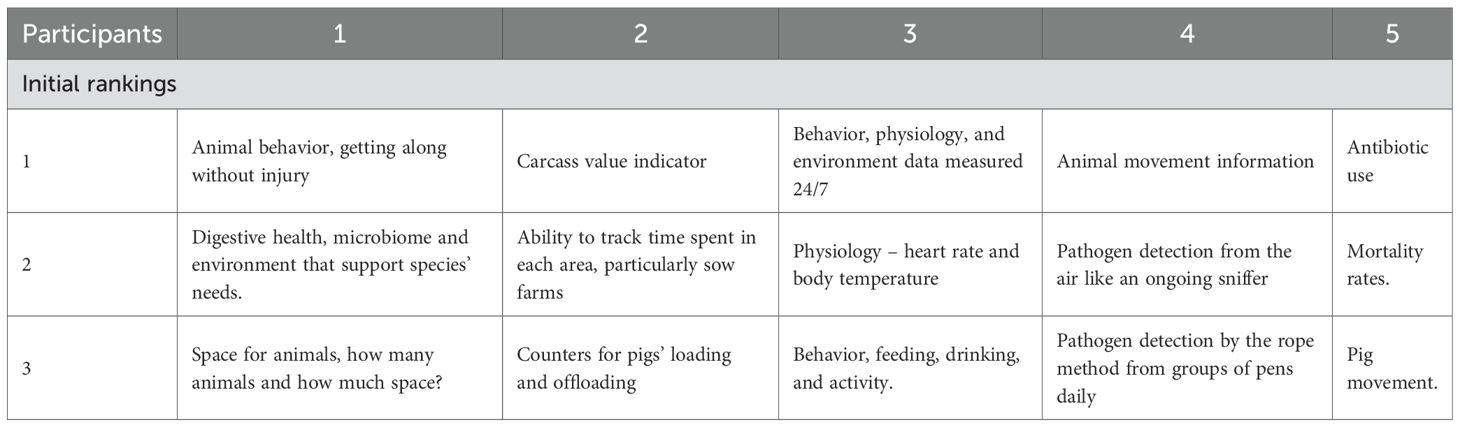

Table 1. illustrates the initial ideas generated by the individual participants in response to the questions “what do you see as your “dream data” or “dream PLF technology”?”. There was diversity in responses where some participants focused on productivity whilst others focused on animal health and physiology. For example, participant 1 (P1) noted carcass value indicators as their most dream data/technology and participant 5 identified pig behavior and physiology as most important. There was clearly an overall focus on health with four out of the five participants noting a health-related issue as important e.g., antibiotic use, heart rates, pathogen detection, and digestive health. Participant 3 more explicitly identified animal welfare as a priority, describing dream data and technology as those that can monitor behavior to reduce the likelihood of injury and those that can ensure sufficient space for the animals. While each participant had expertise in a distinct domain—ranging across animal science, veterinary medicine, regulatory oversight, food processing, and consumer policy—we have not linked domain expertise to individual participant numbers in the table to preserve confidentiality due to the small sample size.

Table 1. Initial list of ranked priorities generated by the five experts in response to the question “what do you see as your “dream data?” or “dream PLF technology?”.

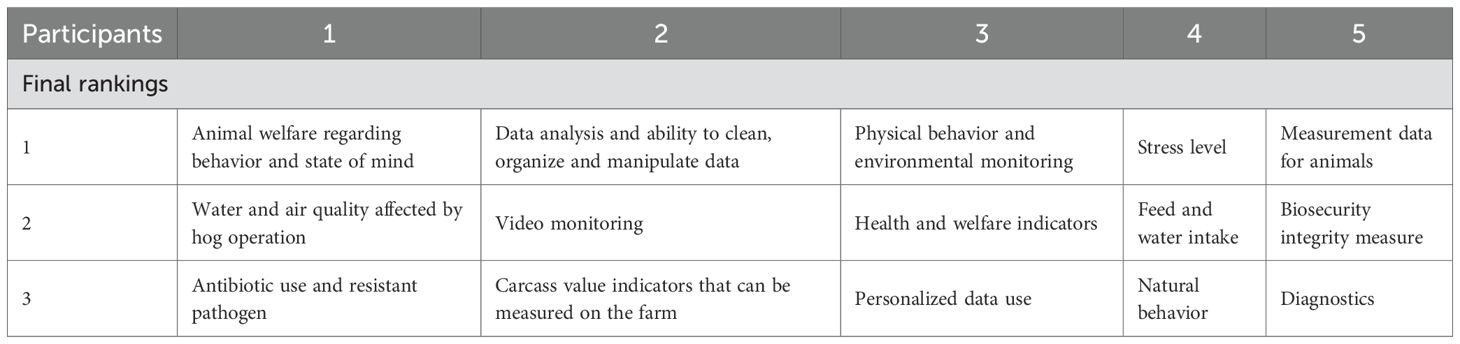

The individual participants’ final priorities are illustrated in Table 2. Some priorities remained the same, albeit encapsulated under broader terms, while some priorities changed (compare back with Table 1).

Table 2. Final list of ranked priorities generated by the five experts in response to the question “what do you see as your “dream data?” or “dream PLF technology?”.

The focus group discussions that followed both rankings by individual participants provided detail and context in terms of the participants’ decision-making processes. We did not utilize a specific discourse analysis of the discussions that followed the NGT rankings but instead simply summarized some of the key discussion points. Before engaging in discussion, each participant prioritized different aspects of precision PLF data based on their individual expertise. However, after the group discussion, there was a notable shift in priorities, reflecting a more integrated and holistic perspective. For example, P1 initially emphasized animal behavior and digestive health but later shifted to broader concerns of animal welfare, environmental impacts, and antibiotic resistance. P2 originally prioritized carcass value indicators and movement tracking but evolved toward animal welfare and sustainability. P3 maintained a focus on continuous measurement but refined this toward personalized data use and health indicators. P4 shifted from movement and pathogen detection to data analysis and surveillance. P5 moved from antibiotic use and mortality tracking toward individualized monitoring and welfare indicators. Overall, the discussion moved participants toward a more interdisciplinary view.

The following sections summarize the key priorities identified by the participants during the NGT focus group.

3.2 Focus group session 2

The second focus group session did not involve the nominal group technique as previously outlined but instead adopted a typical focus group protocol which was followed by reflexive thematic analysis of the transcripts. After several iterations of coding and theme generation we found five key themes: 1. To Split the Check or Not to Split the Check; 2. Knowing the Benefits is Key.?; 3. Reconciling Profit and Welfare in PLF; 4. What Use is PLF to the Animal Anyway? and 5. The Value and Caveats of PLF Data. In the following section, we explain each of the five themes and provide example quotes to illustrate how these themes were constructed from the data.

Theme 1. To Split the Check or Not to Split the Check

This theme reflects tensions around who should bear the financial costs of PLF implementation. Participants expressed concern that farmers are often expected to absorb the bulk of the expense, despite the benefits of PLF extending to other stakeholders, such as processors, retailers, and consumers. This perceived imbalance was viewed as a major barrier to industry-wide adoption.

One participant summarized the issue concisely: “Who is willing to pay or who is going to pay? They are two different questions” (P1). Another noted, “People expect the farmers to do it, nobody else wants to pay for it, but they want to reap the benefit” (P2), suggesting a recurring theme of unfair expectations placed on producers.

Several participants pointed out that PLF often improves production efficiency, yet the economic return may primarily benefit others in the value chain. “If the cost is on the farm but the benefit is to the consumer, then why would the farm … I mean, there has to be some incentives built in before they [farmers] are going to see how it benefits them” (P4). Others were more pessimistic, emphasizing the retail sector’s unwillingness to support implementation: “No, they [supermarkets] will not bear the cost. They will charge you to do what they want you to do” (P2).

Some saw potential in alternative models where data-hungry retailers or regulatory bodies might share costs in exchange for access to information. As one participant suggested, “Retailers … could pay for that [data] to inform consumers” (P3). Still, overall sentiment reflected skepticism about equitable cost-sharing without structural changes or external mandates. In summary, the perceived inequity in PLF investment remains a core concern, with participants emphasizing the need for shared responsibility and economic incentives to ensure widespread adoption.

Theme 2: Knowing the Benefits is Key.

Participants frequently linked stakeholder engagement with a clear understanding of PLF’s direct benefits. The perceived value—whether financial, operational, or ethical—was seen as crucial for motivating adoption.

For farm workers, improved working conditions and job satisfaction were identified as potential benefits. “There’s an opportunity for job satisfaction improvement … if you can identify those tasks that are least desirable, such as power washing, and automate them” (P5). Others noted PLF’s potential to address labor shortages: “If PLF helps with the labor issues that we have at various levels, that could be important” (P4).

Participants emphasized that willingness to pay—whether by consumers or institutions—depended on how well the benefits could be communicated. One explained, “If it’s a public health benefit or a national security benefit … willingness to pay might come from a different place” (P4). Another agreed, adding, “It might be better received if it’s helping protect the consumer versus just increasing our margins” (P2). Overall, the theme highlights that stakeholder buy-in is closely tied to how well the benefits of PLF are understood and aligned with their specific values or goals.

Theme 3: Reconciling Profit and Welfare in PLF

This theme captures a central dilemma: can PLF simultaneously support animal welfare and economic viability? Participants expressed concern that an overemphasis on either profit or welfare could result in a narrow view that undermines the full potential of PLF.

One participant reflected on this tension: “I don’t want us to think that welfare is the only potential positive or negative outcome of PLF” (P5). Another elaborated, “Doing it under the guise of it being the right thing to do is not a sustainable process in an economic market” (P5), highlighting the challenge of implementing welfare-driven initiatives without a viable business case.

Yet, some participants rejected the binary framing. As one stated, “I think the points you made—like it helps—go into willingness to pay. That’s exactly what it is. Am I willing to pay for this because it’s the right thing to do, or because it gives me economic benefit?” (P2). Others pointed out that consumers may support welfare-enhancing practices if they align with their values, but PLF’s role in this was unclear. “The answer is, if you educate a consumer and it matches their values, they will absolutely pay … but how PLF fits into that, I’m struggling” (P1). As noted by one participant, the potential integration of PLF into broader welfare and sustainability metrics raises questions that extend beyond the scope of this study and would benefit from targeted empirical research. We recognize this as a distinct and important area for future investigation. This theme underscores the importance of developing PLF applications that not only advance productivity but also visibly support animal welfare, with clear messaging to stakeholders about their dual value.

Theme 4: What Use is PLF to the Animal Anyway?

This theme highlights skepticism regarding whether PLF technologies genuinely benefit animal welfare. While participants acknowledged that PLF could offer welfare improvements through early detection of issues, there was significant concern that, in practice, PLF might enable more intensive production systems, potentially exacerbating welfare problems rather than alleviating them.

One participant warned, “PLF technology will justify a larger, more concentrated hog operation that comes with known negative effects” (P1). Another expressed concern about technological misuse, stating, “Some technology can be useful … or it can be abused or misused” (P1). Others raised questions about the ethical orientation of PLF systems, noting that “PLF is not currently designed with the animal in mind” (P3).

However, there were also calls for more intentional design and use of PLF to support animal-centered outcomes. As one participant put it, “We have to advocate for taking advantage of PLF for the improvement of animal welfare” (P3). Another added a practical example of how PLF might enhance care: “The day she [the sow] doesn’t stand up at 2:00—it’s a problem. We get a flag that says something’s wrong, that you wouldn’t notice without PLF” (P4).

The discussion revealed that the animal welfare value of PLF is not inherent but contingent on how the technology is developed and deployed. Participants stressed that a welfare-first design philosophy must be embedded into PLF systems if the technology is to meet ethical as well as economic expectations.

Theme 5. The Value and Caveats of PLF Data

The final theme explores tensions surrounding the value, use, and risks associated with PLF data. While participants generally acknowledged the potential of PLF data for improving decision-making, concerns were raised around ownership, security, standardization, and economic viability.

One participant noted broader implications: “There’s data security, there’s intellectual property, and in some circumstances, national security implications” (P5). Others questioned who would own the data: “Is it the farmer, because the sensors are in their farm? Or is it the retailer, because they pay for the technology?” (P3). Data use by regulators was also flagged as a source of uncertainty and concern.

Cost was another recurrent issue. Participants pointed to expenses associated with data storage, software, and IT personnel. “Training staff to make it useful … tends to cost more than people inputting the data” (P2). Another emphasized the need to connect data generation to tangible value: “If the value of PLF data comes only to refine the production process, then the farmer will be the only one paying for it” (P3).

Despite these concerns, several participants remained optimistic. One proposed a future in which farmers could monetize their data: “If farmers realize these data can also be sold … to pharmaceutical or nutrition companies, it would increase the value and make a better business model” (P3).

Standardization and interoperability were cited as key to realizing PLF’s potential. As one participant concluded, “You can’t put different source data gathered in different ways together and make any heads or tails” (P4), underscoring the need for unified data systems and protocols.

This theme illustrates both the promise and complexity of PLF data. Participants supported its use but highlighted the urgent need for clear guidelines on access, ownership, and benefit-sharing.

4 Discussion

While previous studies on PLF have primarily focused on technological capabilities, farm-level decision-making, or producer attitudes, no study to our knowledge has examined how non-farming, off-farm stakeholders—such as regulators, consumer advocates, animal welfare scientists, and policy experts in swine industry—evaluate PLF technologies. This study addresses this gap by applying NGT and reflexive thematic analysis to capture both structured consensus and nuanced discussion among key off-farm actors. A novel contribution of this research is the identification of stakeholder-specific concerns and priorities regarding PLF data governance, and welfare trade-offs—insights that are rarely captured in previous studies.

Both focus group sessions revealed stakeholder perceptions of the benefits, limitations, and economic implications of PLF in swine production. These findings are consistent with prior research emphasizing the importance of financial feasibility, stakeholder-specific value, ethical framing, and data-related challenges (Wolfert et al., 2017; Eastwood et al., 2019). However, this study extends existing work by highlighting how non-farm stakeholders conceptualize PLF as a multi-dimensional socio-technical innovation, rather than simply a farm management tool.

The NGT exercise revealed participants’ perceived need for advanced, integrated data systems to improve decision-making across the value chain. Participants emphasized that while vast volumes of PLF data can be collected, their true value lies in being translated into actionable insights. A novel insight from this session is the call for cross-domain data integration, with applications ranging from carcass value tracking to pathogen monitoring. These findings build on recent studies (e.g., Hoxhallari et al., 2022; Mallinger et al., 2022) but go further by identifying non-producer-driven priorities in PLF data use.

Participants also stressed the importance of making data user-friendly and customizable, pointing out that poor data visualization and interpretability could hinder adoption. This reinforces recent findings by Chavan et al. (2024), but our study adds to the literature by showing that usability concerns are shared beyond the farm level, including by consumer advocacy and regulatory stakeholders who may interact with PLF data for verification or transparency purposes. Health, biosecurity, and environmental sustainability were identified as essential pillars of any robust PLF system. Participants recommended real-time pathogen detection tools, visitor tracking, and environmental monitoring to improve on-farm disease control and ecosystem impact management. These concerns resonate with prior work (Schaefer et al., 2012; Borderas et al., 2009), but our study provides a novel angle by emphasizing the wider systemic implications of PLF beyond the farm—such as its role in national disease prevention infrastructure and public health surveillance.

The theme “To Split the Check or Not to Split the Check” captured stakeholder concerns about the economic burden of PLF. A key insight here is the recognition that economic asymmetry across the supply chain undermines equitable adoption. While many studies highlight cost as a barrier, our participants revealed a more nuanced perspective: even stakeholders who benefit from PLF may be unwilling to invest in it, leading to persistent inequity. As one participant remarked, “Who is going to pay, and who is willing to pay are two different questions.” These dynamics challenge the sustainability of PLF unless cost-sharing frameworks evolve. This study reinforces previous work on market power disparities (Klerkx and Rose, 2020) but uniquely contributes evidence from non-farm stakeholders pointing to policy-level mechanisms—such as mandates or retailer transparency programs—as possible levers for redistributing costs. PLF, as a boundary object (Schillings et al., 2023), may also offer opportunities for collaborative financing models, but these remain speculative without regulatory or market-driven coordination.

The theme “Knowing the Benefits is Key” emphasized that stakeholder adoption depends on personalized, visible value. Participants noted that benefits such as labor savings, improved public health, and consumer trust were central to buy-in. A novel finding here is the strategic framing of PLF as a tool not just for production optimization but also for job satisfaction, labor retention, and even national security—domains typically absent from PLF discourse. Participants also highlighted the double-edged nature of automation: while it may solve labor shortages, it also raises concerns about job displacement. This underscores PLF’s social and economic trade-offs, a dimension that deserves more empirical attention moving forward. Consumer acceptance, meanwhile, was viewed as contingent on PLF demonstrating clear, relatable benefits—especially around food safety and animal health—an observation supported by Rotz et al. (2019) but here grounded in cross-sectoral discourse, not just consumer surveys.

“Reconciling Profit and Welfare in PLF” reflects a core tension in the PLF debate: can profitability and ethics coexist in a market-driven system? Participants worried that the pursuit of either goal in isolation could result in unintended consequences. Although this theme echoes existing literature on techno-ethical trade-offs (Werkheiser, 2020), our findings offer a new contribution by framing this conflict through the lens of stakeholder negotiation, not individual producer decision-making. Participants emphasized that economic returns often override welfare initiatives unless both can be simultaneously achieved. While PLF has the potential to improve welfare (e.g., through real-time monitoring), implementation models must recognize that ethics alone is not a sustainable market driver. This further supports calls for integrated policy frameworks that blend incentives with enforcement.

The theme “What Use is PLF to the Animal Anyway?” captured skepticism that PLF, in its current trajectory, adequately serves animal welfare goals. This study adds to critical perspectives (Driessen and Heutinck, 2015) by surfacing stakeholder worries about technology being evangelized without ethical safeguards. A novel dimension of this theme is that several participants, including those outside academia, urged for PLF to adopt animal-centered design principles—positioning the welfare of the animal as a core design criterion, not a by-product of increased efficiency. Participants highlighted that while PLF can aid in early disease detection or welfare tracking, these benefits will be undermined if the technology is deployed to justify more intensive production models. This finding suggests a need for multi-stakeholder design processes that include ethical oversight, a dimension not widely addressed in PLF design literature.

Finally, the theme “The Value and Caveats of PLF Data” revealed complex attitudes toward data governance. Concerns included data ownership, regulatory access, monetization, and infrastructure costs. Although these issues are well documented (Wolfert et al., 2017), our study contributes first-hand reflections from stakeholders not directly involved in farming, expanding the debate on data ethics to include supply chain, and consumer. The role of integrated decision support systems has been highlighted as essential for transforming raw PLF data into actionable insights for farm-level decision-making, particularly when tailored to specific production goals and systems (Baldin et al., 2021). A novel insight is the idea of farmers becoming data entrepreneurs, selling PLF data to external stakeholders (e.g., pharmaceutical or feed companies). Robust data governance is necessary to ensure equitable benefit-sharing, prevent misuse, and enable fair participation in the data economy (Roger et al., 2021).While promising, this model hinges on establishing robust governance mechanisms, including standardization, security, and access protocols. Participants supported frameworks that advocate for transparency, consent, and equitable participation in the data economy. This study reinforces the need for multi-actor governance to guide responsible PLF data use.

5 Limitations of the study

This study has several limitations. First, while the sample size of five participants is suitable for a qualitative exploratory study, it does not capture the full range of perspectives from the broader off-farm stakeholder community in the swine industry. Second, the hybrid format of the focus group discussion, with three participants attending in person and two joining remotely via Zoom, may have impacted the group dynamics. The interaction between in-person and remote participants may have differed, potentially influencing the depth of the discussion and varying the level of engagement among participants. Third, although the participants represented diverse stakeholders—the study was limited to those connected to the swine industry. As a result, the findings may not apply to other livestock sectors, which may have different priorities regarding PLF technology adoption. Lastly, conducting two focus group sessions in a single day may have restricted participants’ time to fully reflect on the topic. Additional sessions spread over a longer period might have provided deeper insights into the values of PLF technologies to these stakeholders. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the study’s results, and future research involving a larger, more diverse sample and a consistent participation format is recommended to further validate the findings.

6 Conclusions

This study offers a novel contribution to PLF research by foregrounding the perspectives of non-farming stakeholders—a group often underrepresented in both implementation studies and technology design. Using a combined NGT and reflexive thematic analysis, we captured structured and exploratory insights into how PLF technologies are perceived beyond the farm gate. Stakeholders—including veterinarians, animal scientists, food processors, retailers, consumer advocates, and regulatory authorities—highlighted that successful adoption of PLF depends on more than technical performance. Key factors include financial equity, demonstrable benefits across the supply chain, ethical alignment, transparent cost-sharing, responsible data governance, and stakeholder-specific value recognition.

Participants acknowledged PLF’s potential to enhance animal welfare, productivity, and disease prevention, especially when integrated with real-time monitoring and biosecurity systems. However, they also raised concerns about economic burden, data ownership, system usability, and the risk of enabling more intensive farming practices. A recurring theme was the need for user-friendly data tools to support decision-making and the importance of embedding environmental sustainability within PLF strategies to ensure long-term industry resilience.

While this study provides essential insights from non-farm stakeholders, the perspectives of producers remain critical to understanding the practical realities of PLF integration. Future research should therefore expand stakeholder representation—particularly among farmers—and explore standardized data protocols to support equitable, effective, and ethically grounded PLF deployment in livestock production systems. Ultimately, addressing the social, economic, and ethical dimensions of PLF is essential for achieving its equitable and sustainable adoption across the livestock sector.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Michigan State University Institutional Review Board (IRB). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

BA: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LJ: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ST: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. JS: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work is supported by USDA NIFA Inter-Disciplinary Engagement in Animal Systems, project award no. 2021-68014-34140, and by USDA Hatch funding supporting J. Siegford, from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or U.S. Government determination or policy.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aerts J.-M., Jans P., Halloy D., Gustin P., and Berckmans D. (2005). Labeling of cough data from pigs for on-line disease monitoring by sound analysis. Trans. ASAE 48, 351–354. doi: 10.13031/2013.17948

Alamo T., Reina D. G., Millán Gata P., Preciado V. M., and Giordano G. (2021). Data-driven methods for present and future pandemics: Monitoring, modelling and managing. Annu. Rev. Control 52, 448–464. doi: 10.1016/j.arcontrol.2021.05.003

Alonso M. E., González-Montaña J. R., and Lomillos J. M. (2020). Consumers’ concerns and perceptions of farm animal welfare. Animals 10, 385. doi: 10.3390/ani10030385

Baldin M., Breunig T., Cue R., De Vries A., Doornink M., Drevenak J., et al. (2021). Integrated decision support systems (IDSS) for dairy farming: A discussion on how to improve their sustained adoption. Animals 11, 2025. doi: 10.3390/ani11072025

Berger P. L. and Luckmann T. (1967). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Penguin.

Bjerke T., Kaltenborn B. P., and Ødegårdstuen T. S. (2001). Animal-related activities and appreciation of animals among children and adolescents. Anthrozoös 14, 86–94. doi: 10.2752/089279301786999535

Blokhuis H. J., Jones R. B., Geers R., Miele M., and Veissier I. (2003). Measuring and monitoring animal welfare: Transparency in the food product quality chain. Anim. Welf. 12, 445–455. doi: 10.1017/S096272860002604X

Borderas T. F., de Passillé A. M., and Rushen J. (2009). Automated measurement of changes in feeding behavior of milk-fed calves associated with illness. J. Dairy Sci. 92, 4549–4554. doi: 10.3168/jds.2009-2109

Bovo M., Ceccarelli M., Agrusti M., Torreggiani D., and Tassinari P. (2024). DAIRY CHAOS: Data driven approach identifying dairy cows affected by heat load stress. Comput. Electron. Agric. 218, 108729. doi: 10.1016/j.compag.2024.108729

Braun V. and Clarke V. (2021b). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 18, 328–352. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

Braun V. and Clarke V. (2022). Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qual. Psychol. 9, 3. doi: 10.1037/qup0000196

Chavan M. K., Dhage S. A., Gaikwad U. S., Deokar D. K., Lokhande A. T., and Kamble D. K. (2024). Digital livestock farming: A review. Int. J. Adv. Biochem. Res. 8, 469–478. doi: 10.33545/26174693.2024.v8.i4Sf.1027

D’Eath R., Niemi J., Ahmadi B. V., Rutherford K., Ison S., Turner S., et al. (2016). Why are most EU pigs tail docked? Economic and ethical analysis of four pig housing and management scenarios in the light of EU legislation and animal welfare outcomes. Animal 10, 687–699. doi: 10.1017/S1751731115002098

Dawkins M. S. (2021). Does smart farming improve or damage animal welfare? Technology and what animals want. Front. Anim. Sci. 2. doi: 10.3389/fanim.2021.736536

Delbecq A. L., Van de Ven A. H., and Gustafson D. H. (1975). Group techniques for program planning: A guide to nominal group and Delphi processes (Glenview, IL: Scott-Foresman).

Driessen C. and Heutinck L. F. M. (2015). Cows desiring to be milked? Milking robots and the co-evolution of ethics and technology on Dutch dairy farms. Agric. Hum. Values 32, 3–20. doi: 10.1007/s10460-014-9515-5

Eagan B. H. and Protopopova A. (2022). Behavior real-time spatial tracking identification (BeRSTID) used for cat behavior monitoring in an animal shelter. Sci. Rep. 12, 1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-22167-3

Eastwood C., Klerkx L., Ayre M., and Dela Rue B. (2019). Managing socio-ethical challenges in the development of smart farming: From a fragmented to a comprehensive approach for responsible research and innovation. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 32, 741–768. doi: 10.1007/s10806-017-9704-5

Garrido L. F., Sato S. T., Costa L. B., and Daros R. R. (2023). Can we reliably detect respiratory diseases through precision farming? A systematic review. Animals 13, 1273. doi: 10.3390/ani13071273

Grunert K. G., Sonntag W. I., Glanz-Chanos V., and Forum S. (2018). Consumer interest in environmental impact, safety, health and animal welfare aspects of modern pig production: Results of a cross-national choice experiment. Meat Sci. 137, 123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2017.11.022

Hoxhallari K., Purcell W., and Neubauer T. (2022). “The potential of Explainable Artificial Intelligence in Precision Livestock Farming,” in 10th European Conference on Precision Livestock Farming, vol. 1 . Eds. Berckmans D., Oczak M., Iwersen M., and Wagener K. (Vienna, Austria: University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna), 710–717.

Hugé J. and Mukherjee N. (2018). The nominal group technique in ecology & conservation: Application and challenges. Methods Ecol. Evol. 9, 33–41. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12831

Hurník J., Zatočilová A., and Paloušek D. (2021). Circular coded target system for industrial applications. Mach. Vis. Appl. 32, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s00138-020-01159-1

Klerkx L. and Rose D. (2020). Dealing with the game-changing technologies of Agriculture 4.0: How do we manage diversity and responsibility in food system transition pathways? Glob. Food Sec. 24, 100347. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2019.100347

Krueger R. A. and Casey M. A. (2015). “Focus group interviewing,” in Handbook of practical program evaluation, 4th Edn. Eds. Wholey J., Hatry H., and Newcomer K. (Hoboken New Jersey, USA: Wiley), 506–534. doi: 10.1002/9781119171386.ch20

Makkar H. P. S. (2016). Smart livestock feeding strategies for harvesting triple gain—the desired outcomes in planet, people, and profit dimensions: A developing country perspective. Anim. Prod. Sci. 56, 519–534. doi: 10.1071/AN15257

Mallinger K., Purcell W., and Neubauer T. (2022). “Systemic design requirements for sustainable digital twins in precision livestock farming,” in 10th European Conference on Precision Livestock Farming, vol. 1 . Eds. Berckmans D., Oczak M., Iwersen M., and Wagener K. (University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, Vienna, Austria), 718–725.

Martínez-Avilés M., Fernández-Carrión E., López García-Baones J. M., and Sánchez-Vizcaíno J. M. (2017). Early detection of infection in pigs through an online monitoring system. Transbound Emerg. Dis. 64, 364–373. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12372

Munsterhjelm C., Brunberg E., Heinonen M., Keeling L., and Valros A. (2013). Stress measures in tail biters and bitten pigs in a matched case-control study. Anim. Welf. 22, 331–338. doi: 10.7120/09627286.22.3.331

Nicolaisen S., Langkabel N., Thoene-Reineke C., and Wiegard M. (2023). Animal welfare during transport and slaughter of cattle: A systematic review of studies in the European legal framework. Animals 13, 1974. doi: 10.3390/ani13121974

Norton T. and Berckmans D. (2017). Developing precision livestock farming tools for precision dairy farming. Anim. Front. 7, 18–23. doi: 10.2527/af.2017.0104

Ortega D. L., Wang H. H., Wu L., and Olynk N. J. (2011). Modeling heterogeneity in consumer preferences for select food safety attributes in China. Food Policy 36, 318–324. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2010.11.030

Panda S. S., Terrill T. H., Siddique A., Mahapatra A. K., Morgan E. R., Pech-Cervantes A. A., et al. (2024). Development of a decision support system for animal health management using geo-information technology: A novel approach to precision livestock management. Agriculture 14, 696. doi: 10.3390/agriculture14050696

Paul E. S. and Serpell J. A. (1993). Childhood pet keeping and humane attitudes in young adulthood. Anim. Welf. 2, 321–337. doi: 10.1017/S0962728600016109

Perry B. D., Nin Pratt A., and Sones K. R. (2005). “An appropriate level of risk: Balancing the need for safe livestock products with fair market access for the poor,” In: Pro-Poor Livestock Policy Initiative (PPLPI) Working Paper Series. Rome, Italy: Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Available online at: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/1929/PPLPI_WP23_AppropriateLevelOfRisk.pdf (Accessed November 2, 2024).

Reimert I., Webb L. E., van Marwijk M. A., and Bolhuis J. E. (2023). Towards an integrated concept of animal welfare. Animal 17, 100838. doi: 10.1016/j.animal.2023.100838

Remience V., Wavreille J., Canart B., Meunier-Salaün M.-C., Prunier A., and Bartiaux-Thill N. (2008). Effects of space allowance on the welfare of dry sows kept in dynamic groups and fed with an electronic sow feeder. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 112, 284–296. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2007.07.006

Richter S. H. and Hintze S. (2019). From the individual to the population–and back again? Emphasising the role of the individual in animal welfare science. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 212, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2018.12.012

Roger C., Doornink M., George R., Griffiths B., Jorgensen M. W., Rogers R., et al. (2021). Data governance in the dairy industry. Animals 11, 2981. doi: 10.3390/ani11102981

Rotz S., Gravely E., Mosby I., Duncan E., Finnis E., Horgan M., et al. (2019). Automated pastures and the digital divide: How agricultural technologies are shaping labor and rural communities. J. Rural Stud. 68, 112–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.01.023

Rowe E., Dawkins M. S., and Gebhardt-Henrich S. G. (2019). A systematic review of precision livestock farming in the poultry sector: Is technology focused on improving bird welfare? Animals 9, 614. doi: 10.3390/ani9090614

Salmon G., Teufel N., Baltenweck I., van Wijk M., Claessens L., and Marshall K. (2018). Trade-offs in livestock development at farm level: Different actors with different objectives. Glob. Food Sec. 17, 103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2018.04.002

Saro J., Šubrt T., Brožová H., Hlavatý R., Rydval J., Ducháček J., et al. (2024). A decision support system for herd health management for dairy farms. Czech J. Anim. Sci. 69, 502–515. doi: 10.17221/178/2024-CJAS

Schaefer A. L., Cook N. J., Church J. S., Basarab J., Perry B., Miller C., et al. (2012). The noninvasive and automated detection of bovine respiratory disease onset in receiver calves using infrared thermography. Res. Vet. Sci. 93, 928–935. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2011.09.021

Schillings J., Bennett R., Wemelsfelder F., and Rose D. C. (2023). Digital livestock technologies as boundary objects: Investigating impacts on farm management and animal welfare. Anim. Welf 32, e17, 1–e17,10. doi: 10.1017/awf.2023.16

Tedeschi L. O., Greenwood P. L., and Halachmi I. (2021). Advancements in sensor technology and decision support intelligent tools to assist smart livestock farming. J. Anim. Sci. 99, skab038. doi: 10.1093/jas/skab038

Tullo E., Finzi A., and Guarino M. (2019). Environmental impact of livestock farming and Precision Livestock Farming as a mitigation strategy. Sci. Total Environ. 650, 2751–2760. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.10.018

Turner S. P., Nevison I. M., Desire S., Camerlink I., Roehe R., Ison S. H., et al. (2017). Aggressive behavior at regrouping is a poor predictor of chronic aggression in stable social groups. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 191, 98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2017.02.008

Tuyttens F. A. M., Molento C. F. M., and Benaissa S. (2022). Twelve threats of precision livestock farming (PLF) for animal welfare. Front. Vet. Sci. 9. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.889623

Tyris D., Manolakos D., Bartzanas T., Benni S., Amon T., Maselyne J., et al. (2022). RES4LIVE – Energy smart livestock farming towards zero fossil fuel consumption. VDI Ber. 2022, 493–498. doi: 10.51202/9783181024065-493

Van de Ven A. H. and Delbecq A. L. (1972). The nominal group as a research instrument for exploratory health studies. Am. J. Public Health 62, 337–342. doi: 10.2105/ajph.62.3.337

Van Hirtum A. and Berckmans D. (2002). Automated recognition of spontaneous versus voluntary cough. Med. Eng. Phys. 24, 541–545. doi: 10.1016/s1350-4533(02)00056-5

Vranken E. and Berckmans D. (2017). Precision livestock farming for pigs. Anim. Front. 7, 32–37. doi: 10.2527/af.2017.0106

Wathes C. M., Kristensen H. H., Aerts J. M., and Berckmans D. (2008). Is precision livestock farming an engineer’s daydream or nightmare, an animal’s friend or foe, and a farmer’s panacea or pitfall? Comput. Electron. Agric. 64, 2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.compag.2008.05.005

Werkheiser I. (2020). Technology and responsibility: A discussion of underexamined risks and concerns in Precision Livestock Farming. Anim. Front. 10, 51–57. doi: 10.1093/af/vfz056

Winkel A., Mosquera J., Groot Koerkamp P. W. G., Ogink N. W. M., and Aarnink A. J. A. (2015). Emissions of particulate matter from animal houses in the Netherlands. Atmos. Environ. 111, 202–212. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.03.047

Winsten J. R., Kerchner C. D., Richardson A., Lichau A., and Hyman J. M. (2010). Trends in the Northeast dairy industry: Large-scale modern confinement feeding and management-intensive grazing. J. Dairy Sci. 93, 1759–1769. doi: 10.3168/jds.2008-1831

Wolf S. W., Ruttenberg D. M., Knapp D. Y., Webb A. E., Traniello I. M., McKenzie-Smith G. C., et al. (2023). NAPS: Integrating pose estimation and tag-based tracking. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2023, 2541–2548. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.14201

Keywords: agricultural technology, animal welfare, data security, stakeholder perception, swine industry, pig production

Citation: Akinyemi BE, Jessiman L, Turner SP and Siegford JM (2025) Beyond the farm: stakeholder perspectives on precision livestock farming in the swine industry. Front. Anim. Sci. 6:1710969. doi: 10.3389/fanim.2025.1710969

Received: 22 September 2025; Accepted: 26 November 2025; Revised: 25 November 2025;

Published: 10 December 2025.

Edited by:

Emma Fàbrega Romans, Institute of Agrifood Research and Technology (IRTA), SpainReviewed by:

Amit Saha, Fogs Global Research and Consultancy Centre, IndiaIdan Kopler, Migal - Galilee Research Institute, Israel

Copyright © 2025 Akinyemi, Jessiman, Turner and Siegford. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Babatope E. Akinyemi, YWtpbnllbTNAbXN1LmVkdQ==

Babatope E. Akinyemi

Babatope E. Akinyemi Lesley Jessiman

Lesley Jessiman Simon P. Turner

Simon P. Turner Janice M. Siegford

Janice M. Siegford