Abstract

Sows housed in groups navigate complex social relationships, and individual differences affect their engagement and stress responses. To explore what shapes these differences, this study examined how genetic background and early-life social experiences affect social behavior, response strategies, and risk of injury among young sows during pairwise social interactions with unfamiliar older sows. 79 first-parity sows of two genetic lines, Swedish Yorkshire and Dutch Yorkshire, were raised in either socially mixed litters (with access to non-littermates through shared piglet areas) or conventional pens. At 10 weeks, they were either grouped with unfamiliar gilts or remained with their original littermates. After first weaning, each sow was introduced to an unfamiliar older sow in a 60-min interaction test, with behaviors recorded and lesions assessed before and after. By coding both the initiator’s behavior and the response, and linking these to lesion placement, more nuanced response patterns could be analyzed for the short-term development of agonistic encounters. Swedish Yorkshire sows exhibited more aggression, responded more forcefully, and sustained more injuries, particularly to the front and rear of the body, compared to Dutch Yorkshire sows, which showed less aggression and fewer lesions. Early-life social mixing correlated with more affiliative behaviors and a tendency not to react in social interactions, suggesting greater social tolerance, though not reduced injury risk. Social mixing later in rearing was not associated with behavior or lesion counts. Interaction effects were sparse, indicating broadly similar behavior–lesion associations across genetic lines and rearing treatments in this paired interaction test with two sows. A few behavior-specific associations were observed, such as a higher lesion risk among late-mixed sows showing defensive responses, but these were limited in scope and not consistent across outcomes. Across treatments and lines, retreat was common among first-parity sows, which may offer short-term protection but could have longer-term costs in social learning and affiliation. While the controlled test setting allowed for precise measurement of social tendencies, real-world group housing involves more complex interactions. These findings highlight the need to consider genetic line and early experience when evaluating social behavior and indicate that future studies should assess these effects under practical group housing conditions.

1 Introduction

It is widely known that intensive pig production can compromise animal welfare (Albernaz-Gonçalves et al., 2021). While it is challenging to completely eliminate stressors in commercial farming systems, changes to improve pig welfare have been suggested within, e.g., the European Union (EU) (Council of the European Union, 2008), the United States (McGlone, 2013), and New Zealand (Weaver and Morris, 2004), in line with increased public concern about animal welfare (European Commission, 2023). Within the EU, public concern has resulted in initiatives such as the more recent “End the Cage” campaign. Earlier examples of policy changes include the EU ban on individual stalls for sows during part of their pregnancy, which came into force on 1 January 2013 (Council of the European Union, 2008). In Sweden, there is extensive experience with housing dry sows in groups, as confinement of dry sows has been prohibited since 1988 (Djurskyddsförordning (1988:539), 1988; Djurskyddsförordning (2019:66), 2019).

Group housing of sows has been studied extensively, and there is consensus that this practice enhances sow welfare (Verdon et al., 2015; Maes et al., 2016; Sylvén et al., 2025). Well-managed group housing systems are associated with improved opportunities for species-specific behaviors, including social behaviors, and reduced stereotypies (Scientific Veterinary Committee, 1997; Chapinal et al., 2010). However, group housing also introduces certain disadvantages, as sows must be regrouped (Razdan, 2003; Gonyou, 2005). Regrouping can lead to increased aggression among sows as new social hierarchies are established (Greenwood et al., 2014). Aggressive interactions between sows follow similar patterns to those observed in wild boars (Jensen, 1986) and involve contact behaviors such as biting and pushing, as well as non-contact intimidation through body postures and threats (McGlone, 1985). Threats and even mere visual contact can cause stress in low-ranking animals (Boyle et al., 2012). Older sows are generally more dominant than younger sows and more frequently engage in aggressive encounters at mixing (Strawford et al., 2008). The welfare issues associated with group housing arise either directly from the stress and lesions caused by aggression or indirectly through problems such as lameness (Boyle et al., 2012). Lesions caused by aggression are typically cuts or scratches on the skin (Maes et al., 2016). Injuries resulting from aggression can impair reproductive performance and contribute to the culling of sows, especially early-parity sows (Engblom et al., 2007), which increases costs (Stalder et al., 2007). Hence, aggression poses a serious threat not only to sow welfare but also to herd economics (Barnett et al., 2001; Marchant-Forde, 2010; Greenwood et al., 2014). This emphasizes the need to develop management practices for group housing systems that reduce welfare risks, particularly for young sows, and thus reduce economic losses for farmers.

The behavioral repertoire of domestic pigs remains relatively similar to that of their wild counterparts (Stolba and Wood-Gush, 1989; D’Eath and Turner, 2010; Goumon et al., 2020) despite domestication and selective breeding. However, artificial selection for production traits and adaptation to different housing environments have shaped how pigs interact (Rydhmer, 2021). For example, dam-lines have been selected for performance under either individual stalls or group housing systems, which may have indirectly influenced traits linked to social tolerance, aggression control, and conflict resolution. In Sweden, the Swedish Yorkshire (SY) line has been selected under group-housing conditions since the 1980s, whereas the Dutch Yorkshire (DY) line was developed under stall-based systems until the early 2020s. These divergent selection histories may therefore have led to differences in social competence and adaptability between these genetic lines when housed in groups.

Under commercial production conditions, piglets generally have limited opportunities to interact with non-littermates before weaning. This restricted social environment may hinder the development of social competence and increase the risk of stress and aggression when pigs encounter unfamiliar conspecifics post-weaning (Coutellier et al., 2007; Colson et al., 2012; Turner et al., 2017). Allowing early-life social contact between adjacent litters, often referred to as co-mingling, has been studied over the past decade due to its potential to enhance piglets’ social competence and decrease aggressive interactions (Wattanakul et al., 1997; Hessel et al., 2006; Morgan et al., 2014; Camerlink et al., 2018; Salazar et al., 2018). Early socialization has been shown to modify later social responses: socialized piglets display faster but less intense agonistic interactions and form hierarchies more efficiently (D’Eath, 2005; Kanaan et al., 2012; Camerlink et al., 2018; Camerlink et al., 2019; Weller et al., 2019; Oldham et al., 2020). They also show greater behavioral flexibility and more appropriate social responses (Weller et al., 2019), a trait described as social ability, defined as the capacity to adjust social behavior to environmental and social demands (Varela et al., 2020; Taborsky, 2021). Social ability is a multifactorial trait influenced by genetics, early experiences, and social contexts (Dingemanse and Wolf, 2013).

While earlier co-mingling studies provide valuable insights into the short-term benefits of early socialization, they differ from the approach applied in the present work. In most previous studies, piglets were fully mixed during lactation while their dams were confined in farrowing crates, limiting sow–piglet interactions and removing potential influences of maternal behavior and group-housing factors. Moreover, previous research has primarily focused on piglets or growing pigs, whereas little is known about whether the effects of early social experiences persist into adulthood and influence social behavior in reproductive sows. The present study therefore extends this line of research by examining pigs that experienced controlled inter-litter contact during the nursing period and later evaluating them as first-parity sows in a social challenge test, linking early management conditions to later social competence in a group-housing context.

Evaluating social competence in pigs can be challenging, as it requires distinguishing between immediate aggressive responses and broader behavioral tendencies. Standardized behavioral tests, such as paired-interaction or resident–intruder tests, provide a structured framework to assess individual responses under controlled conditions (D’Eath and Pickup, 2002; D’Eath, 2004; Koolhaas et al., 2013; Camerlink et al., 2015; Turner et al., 2020; Backeman Hannius et al., 2024). These tests allow systematic evaluation of both social and exploratory behaviors, offering insight into how early-life experiences may shape later social functioning.

The aim of this study was to assess the effects of genetic line and social mixing experiences during early life on social and damaging behaviors, lesions, and the associations between behaviors and lesions in first-parity sows (FPSs) during a paired-interaction test with an older sow. Testing was carried out after weaning the young sows’ first litter, at a time when they would normally be introduced to an established group of sows. We hypothesized that FPSs with extra social mixing experience and of the Swedish Yorkshire line would have fewer wounds and exhibit fewer behaviors associated with injury compared to FPSs without extra social mixing experience and of the Dutch Yorkshire line.

2 Materials and methods

The experiment and all procedures were approved by the National Ethics Committee for Animal Experiments in Uppsala (registration number: 5.8.18-16279/2017). The experiment was performed at the Swedish Livestock Research Centre, Lövsta, Uppsala, Sweden, from 2018 to 2020.

2.1 Animals, housing, and management

This study included 79 first-parity sows (FPSs) from two genetic lines: purebred Swedish Yorkshire (SY) and at least 75% Dutch Yorkshire (DY). The sows originated from 26 litters divided into seven batches. The first batch was born in January 2018, and the last in November of the same year. Litters were housed in loose-housed farrowing pens from birth until 10 weeks of age and were weaned at 34.0 ± 1.82 days. The average weight was 1.58 ± 0.27 kg at birth and 11.8 ± 2.01 kg at weaning.

This study was part of a larger research project. A detailed description of housing conditions and experiences up to 20 weeks of age is provided elsewhere (Backeman Hannius et al., 2024). In the earlier study (Backeman Hannius et al., 2024), the focus was on short-term effects of social mixing and genetic line on young gilts’ social and exploratory responses in three-minute standardized interaction tests. The present study examined the long-term effects of social mixing and genetic line, and thus animals were assessed over an extended period. Between the two studies, 17 FPSs were excluded [79 FPSs included in this study compared to 96 gilts in the previous study (Backeman Hannius et al., 2024)) due to failure to conceive or fetal loss (N = 8), health issues leading to culling (N = 7), farrowing before transfer to the designated pen (N = 1), and exclusion after a sow broke the door to the test arena at the start of testing (N = 1). These exclusions ensured consistency throughout the study.

The FPSs were kept and handled according to Swedish regulations during all production stages. In summary, housing conditions during the first 20 weeks of life according to Swedish pig production standards are characterized by loose-housed farrowing pens, no tail docking, and routine provision of straw as manipulable enrichment. At 10 weeks of age, the future FPSs were moved to a growing stable in groups of four gilts, where they were housed until 20 weeks of age (see (Backeman Hannius et al., 2024) for details). At 20 weeks of age, they were moved to the sow barn of the research facility.

Within the sow barn, four types of pens were relevant to this study: gilt recruitment pens, non-pregnant gilt pens, breeding pens, and pregnant gilt pens. The future FPSs were initially moved as a group of four to gilt recruitment pens (total size: 7.2 m × 4.5 m), consisting of a deep-litter bedding area (5.0 m × 4.5 m) and an elevated concrete area (2.2 m × 4.5 m) with gilt-sized self-closing feeding stalls. Gilts (and later sows) always had ad libitum access to water via at least one drinking nipple, positioned in the corner of the deep-straw bedding.

They remained in gilt recruitment pens until reaching approximately 80 kg (approximately 26 weeks of age), after which they were transferred to non-pregnant gilt pens. These pens were the same size and had a similar design as the gilt recruitment pen, containing a deep litter bedding area and an elevated concrete section with larger feeding stalls. The FPSs were inseminated while in these pens at 7–8 months of age, depending on their estrous cycle (earliest at second estrus) and on how many gilts could be integrated into the matching sow group after weaning their first litter. Between 3 and 4 weeks after insemination, the FPSs were transferred with their gilt group to the pregnant gilt pens, where they remained until moved to an individual farrowing pen approximately 1 week before the expected farrowing date.

The pregnant gilt pens were half the size (7.2 m × 2.25 m) of the non-pregnant gilt pens. The loose-housed farrowing pens (total size: 3.35 m × 2.0 m) consisted of a concrete lying and feeding area (2.1 m × 2.0 m), a slatted dunging area (1.25 m × 2.0 m), and a concrete-floored piglet corner with a roof, heat lamp, and floor heating accessible only to piglets.

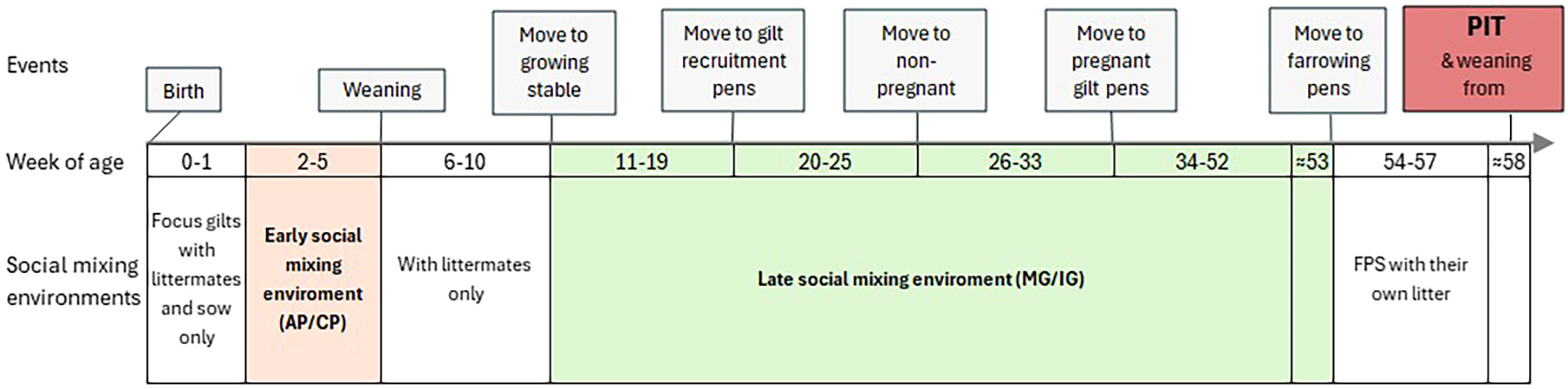

A summary of the experimental design is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Experimental timeline from birth to the PIT performed after weaning of the first litter. Events above the axis mark key management events (birth, weaning, transfers to growing stable, gilt-recruitment stable, non-pregnant gilt pens and pregnant gilt pens and farrowing). Colored bands below the axis indicate the social-mixing treatments applied at each stage: early social mixing (AP, access pen or CP, closed pen) and late social mixing (MG= mixed group or IG, intact group).

The farrowing pens were manually cleaned every morning. Two days before the estimated farrowing date, each pen was provided with approximately 15–20 kg of chopped straw. Due to the slatted floor, the straw gradually decreased, and additional straw was added as needed, following standard Swedish practice. The FPSs were fed a standard commercial dry feed for lactating sows twice daily until 10 days after farrowing. Thereafter, they were fed three times daily until weaning, and piglets had access to creep feed. Each FPS and her piglets had ad libitum access to water from two drinking nipples placed 0.10 m and 0.15 m above the slatted floor.

2.2 Social mixing environments

2.2.1 Early social mixing environments

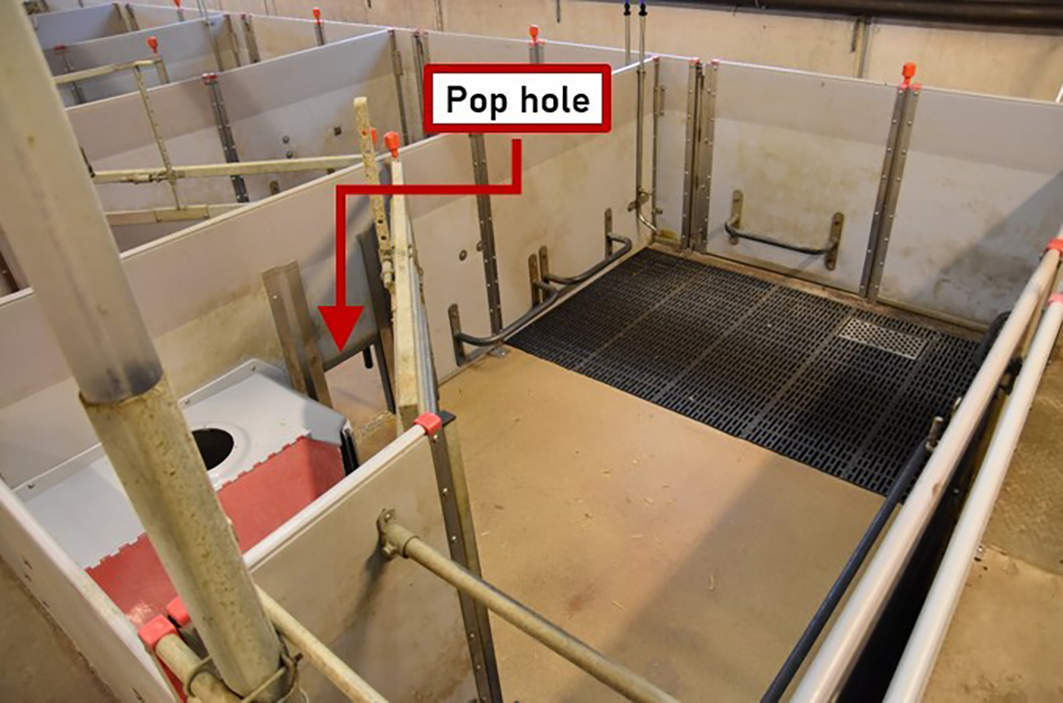

Each farrowing batch contained four sows with litters included in the study. Two were assigned to the control treatment, and two were assigned to the early social mixing environment. In the pens designated for early social mixing, a pop-hole (0.35 m × 0.30 m) was installed in the piglet corner between two side-by-side pens (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Picture of the right-hand pen of two access pens (APs), created from conventional loose housing farrowing pens, with a pop hole situated between the piglet corners in each pen. The image is reused from from Backeman Hannius et al. (2024), Animal 18:101349, under the CC BY 4.0 license.

The pens with the pop-hole were designated access pens (APs). The APs allowed piglets to move freely and co-mingle between the two pens but prevented the sows from accessing the neighboring pen. This created an extended social environment for piglets in the AP treatment. The pop-hole was opened when AP piglets were 2 weeks old (13.1 ± 1.79 days), aligning with the natural socialization period when piglets in feral groups would interact with unfamiliar piglets (Jensen, 1986). Thus, it simulated a more natural early social mixing environment within a conventional housing system. The pop-hole was closed at weaning when piglets were approximately 5 weeks old (34.3 ± 1.87 days). The remaining two pens in each batch lacked a pop-hole, giving them the designation closed pens (CPs), and were used as the control treatment. The study design was balanced with two APs and two CPs in each batch, as well as two pens designated for each genetic line (DY and SY). This ensured that piglets in the AP treatment were exposed to piglets from the other genetic line. However, due to a shortage of SY litters, two of the 13 litters in the AP treatment did not co-mingle with any litters of the other genetic line. In one batch, two DY litters were mixed, and in another batch, a DY litter was paired with a crossbred (SY × DY) litter. Piglets of the SY × DY line were excluded from the analysis.

2.2.2 Late social mixing environment

When the FPSs reached approximately 10 weeks of age (67.9 ± 7.66 days), they were transferred to an experimental growing pig stable. Here, the new FPS groups of four were housed in pens (total area: 3.96 m × 1.80 m) with a concrete-floored area for feeding and lying, alongside a slatted dunging section measuring 1.80 m × 1.00 m. The slatted dunging section was elevated 0.18 m above the concrete floor of the pen.

In the late social mixing environment, two out of the four future FPS groups from each batch were placed in a mixed group (MG), and the other two groups were placed in an intact group (IG). In the IG, the future FPSs were housed with individuals from their own litter, with whom they had already established social bonds. In contrast, the MG FPSs from two different litters were combined, with each group containing one familiar FPS and two unfamiliar ones, which required the FPSs to interact with unknown individuals. The FPSs remained in these groups until they were transferred to individual farrowing pens 1 week before the expected farrowing.

This experimental setup resulted in four social-experience combinations balanced across genetic lines (Table 1).

Table 1

| Early social experience | Late social experience | SY gilts | DY gilts | Total gilts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP (Yes) | MG (Yes) | 11 | 11 | 22 |

| AP (Yes) | IG (No) | 5 | 11 | 16 |

| CP (No) | MG (Yes) | 10 | 6 | 16 |

| CP (No) | IG (No) | 11 | 14 | 25 |

| Total | 38 | 43 | 79 |

Frequencies of first parity sows (FPSs) allocated to each combination of early and late social experience, presented separately for the two genetic lines.

Rows represent combinations of early social mixing (AP, access pen; CP, closed pen and late social environment after weaning (MG, mixed group; IG, intact group)), where AP and MG involve social experience (Yes) and CP and IG do not involve social mixing (No). Columns indicate the genetic line of the FPS (SY, Swedish Yorkshire; DY, Dutch Yorkshire. Frequencies denote the number of FPSs) assigned to each social experience × genetic line combination.

2.3 Paired interaction test after weaning FPSs first litter

The paired interaction test (PIT) between the FPS and an older sow occurred on the day of weaning. For the FPSs, weaning of their first litter occurred at approximately 58 weeks of age (408.9 ± 26.03 days). In the days leading up to the PIT, a research assistant identified suitable older sows within the sow group into which each FPS would be integrated after weaning. Preference was given to older sows (at least second parity) that were entirely unrelated to the study, i.e., not dams of FPSs, not FPSs from previous batches, and not sows that had previously acted as opponents (N = 50).

Of the available sows, an older sow was randomly selected to be paired with an FPS for the PIT to avoid bias. If such sows were unavailable, priority was given to older sows that had previously served as opponents in a PIT (N = 27). As a last resort, sows originally investigated as FPSs that had completed the experiment and were no longer part of the study were selected (N = 2). Although it was not always possible to use an older sow completely independent of the study, all pairs consisted of an older opponent sow and an FPS that had never encountered each other.

The PIT was performed in the sow group housing pen (total size: 7.00 m × 7.20 m), designated the test arena, where the FPS would later be integrated. The test arena (Figure 3) included the deep-straw bedding section of the pen (5.00 m × 7.00 m). The feeding area occupying the remainder of the pen was locked and inaccessible. A drinking nipple was available in the corner of the test arena, and a large rectangular straw bale (2.30 m × 0.85 m × 0.90 m) was placed in the center. All sows around the test arena that could potentially interact with the test animals were moved. Before the test commenced, both sows were marked with a pattern for individual identification.

Figure 3

The test arena for pigs in the paired interaction test (PIT) carried out after weaning of the first parity sow’s (FPS’s) litter.

The PIT always started with the younger sow being removed from her farrowing pen, guided to the sow barn, and subsequently led into the test arena. After this, the older sow was brought from her farrowing pen to the sow barn and guided into the test arena. Once the older sow entered, the gate of the arena was closed, and the sows were allowed to interact for 60 min. A research assistant monitored the test via live video on screens placed in a separate area from the test pen to intervene if necessary, i.e., if the endpoint specified in the ethical permit was reached. This endpoint was defined as the onset of unresponsiveness, evident apathy, or physical impairment preventing the sow from adequately reacting to or escaping social contact. In practice, none of the animals reached these predefined endpoints, and thus no intervention was required.

After 60 minutes, the feeding stalls were opened, and once the sows entered them, they were locked in. The sows were then individually guided to separate holding pens, where they remained until all pairs from that testing session had been evaluated. Following this, both the FPSs and older sows were integrated into their designated sow group according to standard procedures of the research herd.

2.4 Data collection

2.4.1 Behavioral observations

Behavioral observations were made from video recordings of each PIT pair. The cameras were elevated, attached to stable fixtures on opposite sides of the test arena, to cover the entire arena from two angles. The observation period began when the older sow’s front legs entered the deep-bedded area, and behavior was continuously observed.

An ethogram (Table 2) was used to register the social behavior of the performing sow, the response of the receiver sow, the targeted body part of the interaction (if physical contact occurred), other social behaviors, time, and which sow initiated the first interaction. A behavioral change or a pause lasting at least three seconds was used as the criterion for recording a new behavior. The recordings from each PIT pair were analyzed using BORIS event-logging software (version 7.9.8 [Friard and Gamba, 2016)].

Table 2

| Behavior categories | Variable name | Definition | Performing behaviors observed | Response behaviors observed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affiliative | Nosing | Snout is touching or is within sniffing distance of other pig. | Yes | Yes |

| Affiliative | Nibbling | The pig is touching with its nose and pushes, the pig can also have its jaw slightly open and use her teeth. | Yes | Yes |

| Damaging | Biting | The pig bites the other pig with its teeth in contact with the other pig’s skin. | Yes | Yes |

| Damaging | Head knock | A rapid thrust upwards or sideways with the head or snout | Yes | Yes |

| Pressing | Parallel pressing | The pigs stand side by side (facing the same direction) and push hard with their shoulders against each other, throwing the head against the neck or head of the other. | Yes | Yes |

| Pressing | Inverse parallel pressing | The pigs stand front to front (facing opposite directions) and then push their shoulders hard against each other, throwing the head against the neck and flanks of the other. | Yes | Yes |

| Pressing | Press | The receiving pig presses her body (or face) against the performing pig | No | Yes |

| Warning | Threat | The pig stares and/or turns her head towards the other pig and stays, or she walks towards her, the other pig reacts. | Yes | No |

| Warning | Chewing | The pig performs chewing without anything in her mouth, one session is continuous chewing and a new one begins when the chewing has stopped with three second in-between until next chewing session. | Yes | No |

| Other | Levering | The pig puts its snout under the body of the other pig and lifts her up in the air, you can see that the body is pushed upwards but all legs can still be in the ground. | Yes | Yes |

| Other | Mouth open | The pig’s mouth is open, but it is not biting or nibbling the other sow. | Yes | Yes |

| Other | Shaking | The sow rapidly shakes her body from side to side | Yes | No |

| Other | Climbing/riding | At least one hoof/leg on the top of another pig/mounting the other pig. | Yes | Yes |

| Retreat | Retreat | The sow moves away from the other sow, can be accompanied with a push to get by the other pig. Can also be that the pig moves the target body part away, for example turns her neck backwards or to the side to escape an attack to this area. | No | Yes |

| Threat | Threat | The pig stares and/or turns her head towards the other pig and stays, or she walks towards her, the other pig reacts. | No | Yes |

| No change | No change | The receiving pig does not react to the interaction of the other sow, standing still or continues what she was doing before the interaction. | No | Yes |

Ethogram of observed behaviors and whether these were observed as a performed or a response behavior, and their corresponding behavioral category used in the analyses.

The ethogram was developed based on and refined from previous studies (e.g., Jensen, 1980; Weng et al., 1998; Rault, 2017) and further adjusted through a pilot study. The pilot study involved eight randomly selected PITs, each continuously observed for the full 60-min duration by a trained observer. The analysis showed that most social behaviors occurred within the first 20 min, while the final 10 min provided additional behavioral information. Considering the substantial time required to analyze full-length video recordings, a key objective was to reduce the observation period without compromising data quality. Therefore, behavioral data were collected for minutes 1–20 and minutes 50–60 of the test for all FPSs in the final dataset. All behavioral observations were conducted by a single trained research assistant to ensure consistency.

2.4.2 Lameness and lesions

Lameness and skin lesions were assessed before and after each PIT on the FPSs but not on the older sows. Approximately 30 min before the first test started, all FPSs from the batch were assessed to establish individual baselines. The health assessment was based on the Welfare Quality® protocol (Welfare Quality, 2009) and included evaluations of lameness and injuries. Lameness was categorized as: no remarks (normal gait); slight lameness (the animal has difficulty walking but is still using all legs); or severe lameness (the animal is severely lame, is putting minimal or no weight on the affected limb, or is unable to walk).

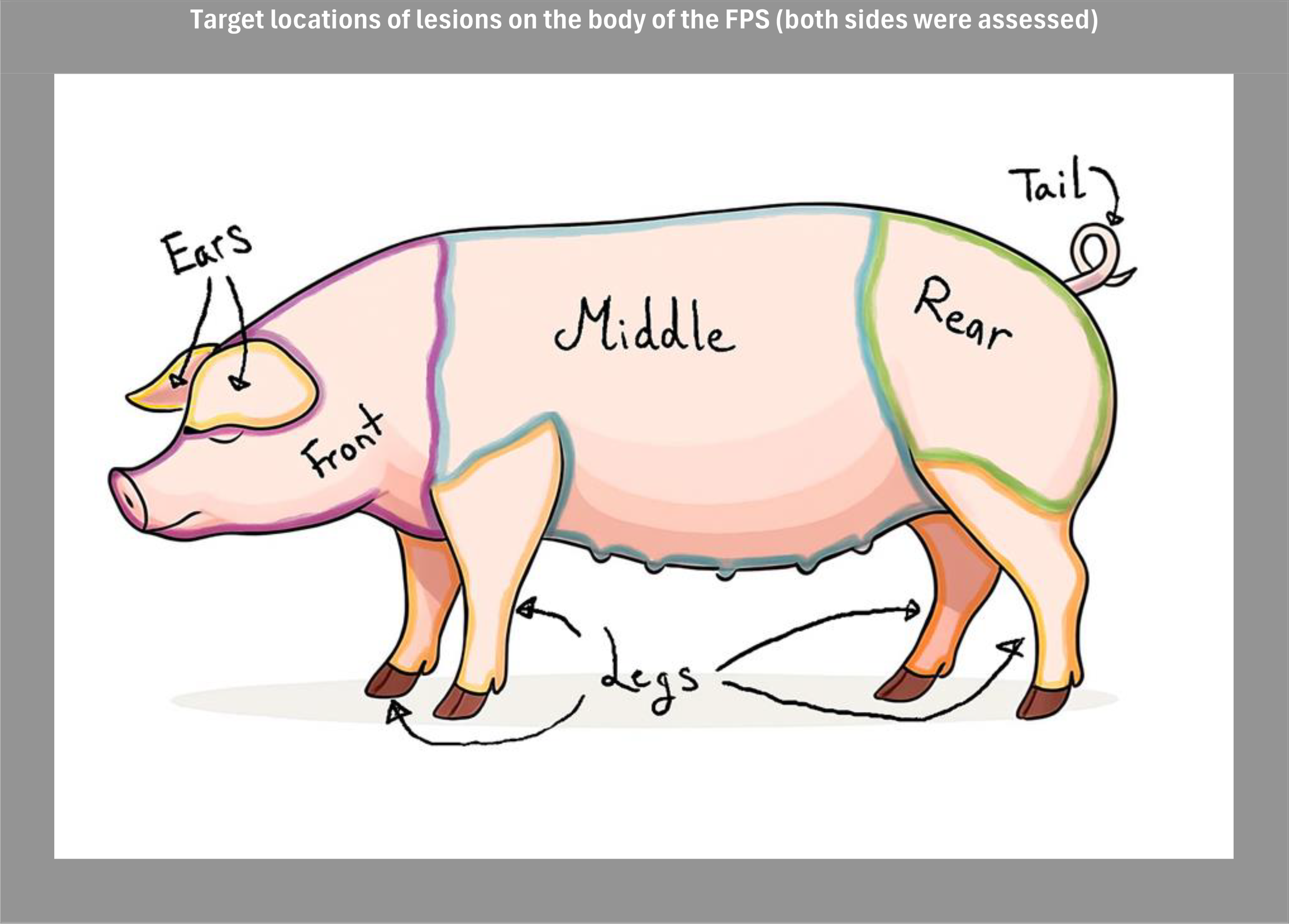

Skin lesions were examined on the ears, front, midsection (middle), hindquarters, legs, and tail (Figure 4). Lesions were counted and assessed based on their largest dimension. Scabs were considered a single lesion if forming a continuous line. A scratch exceeding 2 cm was classified as one lesion; two parallel scratches with a maximum separation of 0.5 cm were also counted as one lesion. Small lesions (<2 cm) were recorded as one lesion. Bleeding wounds 2–5 cm in length, as well as healed wounds >5 cm, were classified as five lesions. Deep, open wounds >5 cm were also recorded as five lesions.

Figure 4

Illustration of the target locations assessed for skin lesions. Both left and right body sides were evaluated to account for potential asymmetries in lesion distribution. In the analysis, ears and front were grouped into a Front body region, and hindquarters and tail were grouped into a Rear body region.

Approximately 15 min after each PIT, once the animals had been moved into separate holding pens, a follow-up health assessment was conducted using the same protocol to quantify new lesions or potential lameness that may have developed during the PIT. All assessments were conducted by a single trained research assistant to ensure consistency.

2.5 Data formatting and statistical analysis

2.5.1 Aggregation of behavior variables and lesions prior to statistical analyses

To improve interpretability and analytical robustness, individual behavioral variables and lesion variables were conceptually aggregated into broader categories, taking into account both theoretical and practical considerations. Behavioral categories were based on ethological descriptions and interpretations of the presumed function of the behavior, whereas lesion categories were based on the presumed underlying cause of lesions on different parts of the body.

2.5.1.1 Social behaviors performed by the FPSs and older sows

Initiation of social interactions was grouped separately according to whether the initiating behavior was performed by the FPS or the older sow. The behaviors Nosing and Nibbling were aggregated into a category called Affiliative behaviors; Biting and Head knocks were aggregated as Damaging behaviors; Chewing and Threat were aggregated as Warning behaviors; Inverse parallel pressing and Parallel pressing were aggregated as Pressing; and Mouth open, Climbing/riding, Levering, and Shaking were grouped as Other behaviors (Table 2).

Because the focus of the study was on the FPSs’ responses, only the response behaviors of the FPS, not the older sow, were analyzed. Behaviors performed by the FPS as a response to the older sow’s behavior were grouped as follows: Affiliative behaviors and Damaging behaviors as described above; Inverse parallel pressing, Parallel pressing, and Press were aggregated as Pressing; and Mouth open, Climbing/riding, and Levering were aggregated as Other behaviors. Response behaviors such as Retreat, Threat, and No change in behavior were not grouped, as these represent distinct response strategies with different functional meanings and were analyzed separately.

To study social interactions in more detail, we subsequently investigated the associations between the older sow’s behavior toward the FPS (aggregated as described previously) and the FPS’s response to this behavior (aggregated as described above).

2.5.1.2 Lesions on the FPS

Changes in lesion scores for the FPSs as a result of the PIT (lesion score after minus lesion score before the PIT) were aggregated into categories prior to statistical analysis based on the underlying cause of receiving lesions on different parts of the body (e.g., Welfare Quality, 2009, Turner et al., 2006). Lesions counted on the ears and front were categorized as Front; lesions on the hindquarters and tail were categorized as Rear. Lesions on the middle body region and legs were not aggregated into new categories, as they did not conceptually align with predefined lesion-location categories used in previous studies (e.g., Turner et al., 2006, Tönepöhl et al., 2013). In addition, the total number of lesions gained on the entire body during the PIT was analyzed.

2.5.1.3 Associations between behavior and lesions

To analyze associations between behavior and lesion outcomes, the same behavioral categories and lesion categories described above were applied. This ensured consistency across analyses and enabled meaningful comparisons with other results in this study.

2.5.2 Statistical analyses

Data from BORIS were exported and formatted in Microsoft® Excel® (Microsoft 365 MSO, Version 2502 Build 16.0.18526.20168) for statistical analyses. The PIT dataset included social-behavior recordings (a total of 8,225 behaviors registered during social interactions, including both initiating and response behaviors) and lesions from 79 PITs (one FPS per PIT).

All statistical analyses were conducted in R (version 4.3.1) (R Core Team, 2024). Generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) were fitted using the glmmTMB package (Brooks et al., 2017). Model selection was based on a backward stepwise procedure starting from full models that included all biologically relevant fixed effects and interactions. At each step, interactions were removed, and models were compared using Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) values and model weights via the MuMIn package (Bartoń, 2025). Models excluding interaction terms fitted better and were therefore used as the final models.

Random effects (e.g., Pen, Old_batch, the batch in which the FPS was born) were also tested in preliminary models. For clarity and interpretability, the final models were GLMs without random effects. In most cases, models were fitted using a negative binomial distribution (family = nbinom2) due to overdispersion in the count data (variance > mean). Zero-inflated models were considered and used only when clearly superior based on AIC (e.g., for lesions on the middle part of the body). Model assumptions were evaluated based on best fit, assessed by AIC, residual diagnostics, and distributional properties (e.g., variance > mean).

2.5.2.1 Statistical models

Latency to first contact (seconds to first physical contact) was analyzed as a continuous outcome with Model 1. Based on the right-skewed distribution and lack of zero-inflation, a gamma model with a log link was used. To explore whether the FPS or the older sow initiated the first contact, who approached first was analyzed with Model 1 using binary logistic regression (1 = FPS initiated, 0 = sow initiated).

To examine how the frequency of initiating and response behaviors and the lesions gained) during the PIT (points 1–4 below) were influenced by genetic line, early social mixing environment, late social mixing environment, and season, models were fitted for each variable using glmmTMB with a negative binomial distribution. The variables analyzed were:

-

performed by the FPS: outcome variable Y = count of each specific initiating behavior summarized per FPS.

-

performed by the older sow toward the FPS: outcome variable Y = count of each specific initiating behavior by the older sow summarized per FPS.

-

FPS response behaviors to interactions initiated by the opponent older sow: Outcome variable Y = counts of each specific response behavior summarized per FPS).

-

Lesion outcomes (e.g., total lesions received during the PIT, lesions in specific body regions): Outcome variable Y = counts of each specific lesion summarized per FPS.

The final model fitted for variables 1–4 is Model 1.

Model 1: Y ~ Genetic line + Early social mixing environment + Late social mixing environment + Quarter + e.

To investigate whether the FPS responded differently depending on the behavior performed by the older sow, GLMMs were analyzed separately for each behavior category using Model 2, fitted with glmmTMB using a negative binomial distribution (family = nbinom2). The response variable (n) represented the number of times a specific behavior was observed for an FPS in response to each initiating behavior performed by the older sow, derived by aggregating the dataset using dplyr::summarize() in R.

Only sow-behavior categories with sufficient variability and complete data across grouping variables were retained. Models were successfully estimated for Damaging behaviors, Affiliative behaviors, and Warning behaviors. Categories with sparse data, such as Press and Other performed by the older sows, as well as Damaging behaviors and Other demonstrated by the FPSs, were excluded due to insufficient frequencies (fewer than 30 observations in total), to ensure analytical robustness and avoid convergence issues.

For Model 2, Y was the count of each response behavior per FPS relative to each older sow behavior performed during the PIT. The interaction between older sow behavior and genetic line, early social mixing environment, and late social mixing environment was assessed to determine whether response patterns varied by genetic line or social mixing conditions. Analyses were conducted separately for each sow-behavior category to capture behavior-specific dynamics. Only older sow behaviors with sufficient data across all combinations were included. Specifically, robust models were fitted for Damaging behaviors, Affiliative behaviors, and Warning behaviors, which were the only categories with enough observations. Behaviors with sparse data (e.g., Press and Other) were excluded due to low frequency and model-convergence issues.

Associations between behavior and lesions were analyzed using regression analyses with generalized linear models (GLMs) with a negative binomial distribution (family = nbinom2). These models were fitted for each behavioral category variable (performed, response, or directed at the FPS) and each lesion outcome (Total, Front, Rear, Middle, and Legs) using Model 3, where Y was the lesion count per FPS (either total change or region-specific counts).

Model 2: Y ~ Older sow behavior *Genetic line + Older sow behavior * Treatment_1 + Older sow behavior * Treatment_2 + e.

For Model 2, model performance and interaction significance were evaluated using Type III Wald chi-square tests (drop1, test = “Chisq”). Estimated marginal means (LSMeans ± SE) and Tukey-adjusted pairwise contrasts (α = 0.05) were calculated using the emmeans package. Significant differences between FPS response behaviors were visualized using grouped bar plots with error bars and annotated horizontal brackets indicating significant pairwise comparisons.

Model 3: Y ~ Behavior * Genetic line + Behavior * Treatment 1 + Behavior * Treatment 2 + e.

For Model 3, Behavior refers to the predictor variable, representing either behaviors performed by the FPS, behaviors directed against the FPS by the older sow, or FPS response behaviors following social interactions. The specific predictor variables were placed as interactions with Genetic line, Early social mixing environment, and Late social mixing environment. In Model 3, interaction terms were explicitly included to detect potential moderation effects of social background and genetic line on the behavior–lesion relationship.

The variable Quarter was added as a fixed effect to adjust for seasonal variation but was not interpreted. The models for associations between behavior and lesions were fitted using glmmTMB, and fixed-effect estimates (β), corresponding risk ratios [RR = exp(β)], and p-values were extracted using the broom.mixed package. Results were automatically structured by behavior type and exported to Excel using writexl, with separate sheets for all effects, significant effects, all interactions, and significant interactions. This approach enabled comprehensive detection of context-specific behavioral risk patterns for skin lesions.

For Models 1, 2, and 3, the predictor variables were defined as follows:

: Genetic line represents the FPS breed (Swedish Yorkshire [SY] or Dutch Yorkshire [DY]); Early social mixing environment indicates whether the FPS had access to early mixing with non-littermates (access pen [AP] vs. closed pen [CP]); Late social mixing environment describes whether FPSs were housed in mixed groups (MG) or intact groups (IG) after 10 weeks of age.

In Models 1 and 3, Quarter (Q1–Q4) was included as a fixed effect to denote the time of year the test was conducted and to control for potential seasonal variations; however, its effects were not interpreted. Interaction terms were tested in all models but were excluded from the final Model 1 due to multicollinearity or lack of improvement in model fit.

Estimated marginal means (EMMs) and post hoc comparisons were calculated using the emmeans package (Lenth et al., 2025) for models with significant fixed effects. Pairwise contrasts and confidence intervals were used to explore the direction and strength of effects. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3 Results

The core results are presented below. Descriptive statistics and tables with p-values are provided as Supplementary Material. Results are presented as LS-means ± SE unless otherwise stated.

3.1 Latency to first contact and who approached first

Latency for the two sows to approach each other in the PIT was on average 10.6 s (SD = 11.47 s). There were no significant effects of genetic line or early or late social mixing environment on the latency for the two sows to approach each other in the PIT. In total, FPSs initiated contact in 76% of PITs. There were no significant effects of genetic line or social mixing environments on whether the FPS or the older sow approached first.

3.2 Behaviors initiating social interactions in the PIT

3.2.1 Initiating behaviors by the FPS towards the older sow

FPSs from the AP treatment demonstrated significantly more affiliative behaviors than FPSs from the CP treatment (19.1 ± 2.62 and 12.7 ± 1.68, respectively; F = 4.56, df = inf, p = 0.033). FPSs of the SY line performed significantly more damaging behaviors than FPSs of the DY line (23.39 ± 6.02 and 6.98 ± 1.80, respectively; F = 10.40, df = inf, p = 0.001) and also more warning behaviors (15.88 ± 1.77 and 8.99 ± 0.97, respectively; F = 12.84, df = inf, p < 0.001). The late social mixing environment had no significant effects on FPS-initiated behaviors.

3.2.2 Initiating behaviors by the older sow towards the FPS

Damaging behaviors were significantly more often directed toward SY compared to DY FPSs (34.6 ± 5.07 and 20.8 ± 2.91 times per FPS, respectively; F = 5.86, df = inf, p = 0.016). Pressing was also significantly more frequently performed against SY than DY FPSs (1.87 ± 0.33 and 1.03 ± 0.20 times per FPS, respectively; F = 5.00, df = inf, p = 0.025). Neither early nor late social mixing environment had significant effects on older-sow-initiated behaviors.

3.3 Response behaviors during social interactions in the PIT

3.3.1 General FPS behavior responses

Damaging behaviors performed as FPS responses to older-sow-initiated interactions occurred significantly more often among SY FPSs compared to DY FPSs (1.54 ± 0.51 and 0.26 ± 0.12 times per FPS, respectively; F = 9.45, df = inf, p = 0.002). Pressing was also a more common response among SY compared to DY FPSs (27.00 ± 5.20 and 14.00 ± 2.59 times per FPS, respectively; F = 5.53, df = inf, p = 0.019).

FPSs from the AP early social mixing environment showed no change in behavior significantly more often than FPSs from the CP treatment (4.29 ± 0.77 and 2.07 ± 0.51 times per FPS, respectively; F = 4.29, df = inf, p = 0.038). The late social mixing environment had no significant effects on FPS response behaviors.

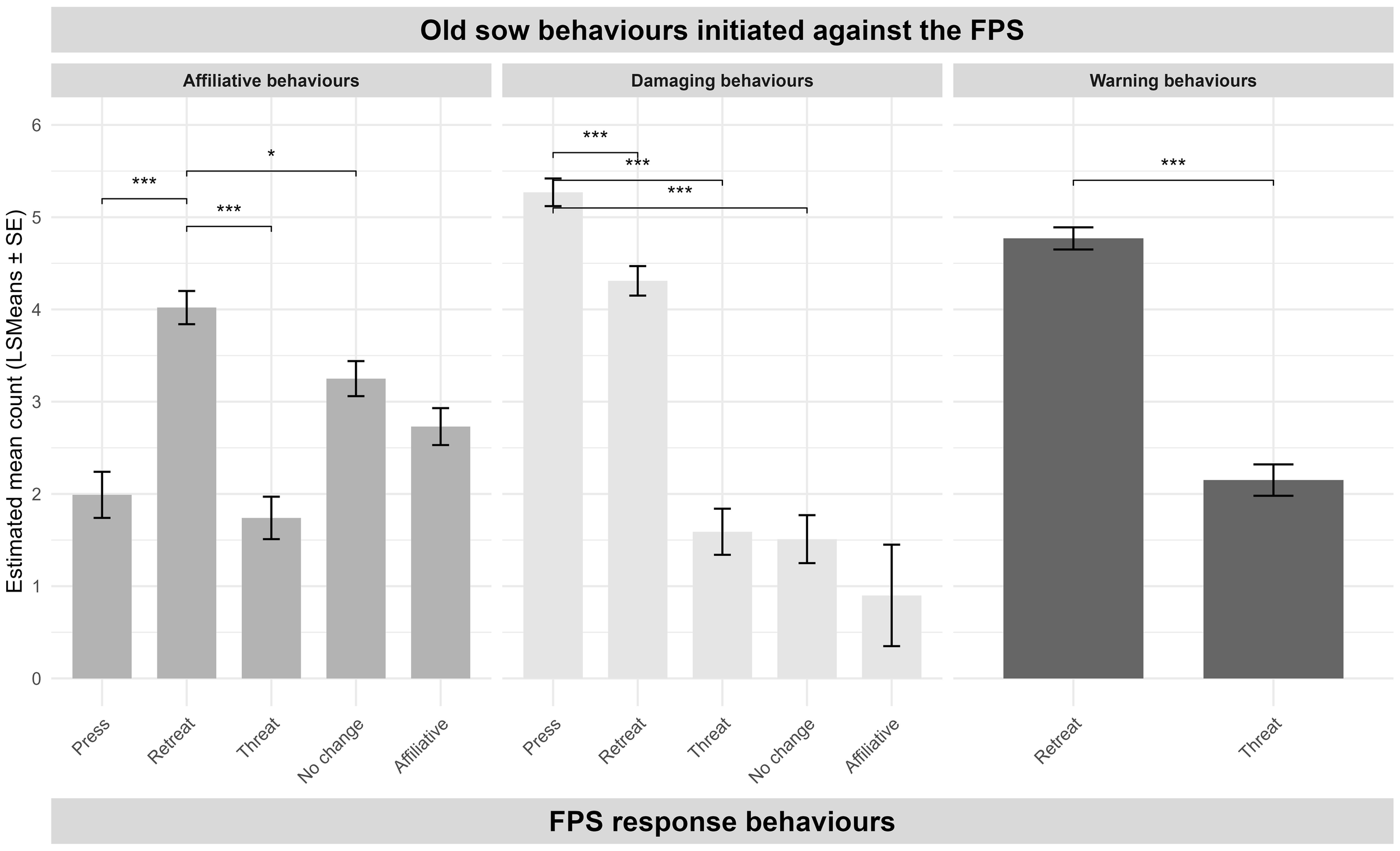

3.3.2 FPSs’ response behaviors classified according to older sow behaviors

Frequencies of response behaviors by FPSs, according to the type of behavior the older sow showed when initiating the social interaction, is presented in Table 3. Differences in FPS responses according to the older sow’s initiating behavior are presented in Figure 5. No significant interactions were found between the older sow’s initiating behavior and the genetic line of the FPS (p < 0.056), their early social mixing environment (p < 0.31) or late social mixing environment (p < 0.28).

Table 3

| Response behavior by FPS | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Damaging behavior | Affiliative behavior | No change | Press | Threat | Retreat | Other | ||

| Behavior of old sows | Damaging behavior | 24 | 7 | 16 | 70 | 14 | 72 | 3 |

| Affiliative behavior | 1 | 55 | 50 | 22 | 27 | 71 | 0 | |

| Warning behavior | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 41 | 76 | 0 | |

| Press | 0 | 1 | 0 | 50 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| Other | 1 | 0 | 3 | 16 | 1 | 5 | 0 | |

Frequencies of response behaviors displayed by the first parity sows (FPS) in relation to the type of behavior initiated by the older sow during a social interaction.

Rows represent the type of behavior performed by the older sow at the onset of the interaction, and columns indicate the FPSs response behavior to that specific behavior. Frequencies denote the total number of observed interactions per behavior combination.

Figure 5

Response behaviors of first parity sows (FPS) following three types of behaviors exhibited by the older sow during the paired interaction test (PIT). Bars represent estimated mean counts (LSMeans ± SE) of each response behavior, separated by the older sow’s behavior. Only behaviors with sufficient data to estimate model parameters are shown. Horizontal brackets indicate pairwise comparisons between FPS response behaviors within each sow behavior category, based on model estimates. Significance levels are denoted as follows: p < 0.05 (*), and p < 0.001 (***).

3.4 Occurrence of lesions on FPS

The increase in total lesions from before to after the PIT was significantly higher for SY FPSs than for DY FPSs (4.29 ± 0.98 and 2.07 ± 0.51, respectively; F = 8.45*, df = inf, p = 0.005). SY FPSs also had significantly more lesions on the front body region (6.42 ± 1.38 and 3.33 ± 0.69 per FPS, respectively; F = 4.52, df = inf, p = 0.034) and the rear body region (3.11 ± 1.17 and 0.98 ± 0.37 per FPS, respectively; F = 4.30, df = inf, p = 0.038). A similar pattern was observed for lesions on the legs, where SY FPSs had significantly more lesions than DY FPSs (1.06 ± 0.43 and 0.27 ± 0.12 per FPS, respectively; F = 5.44, df = inf, p = 0.020). There were no significant effects of early or late social mixing environment.

3.5 Associations between behavior and lesion count on the FPSs

Increased frequencies of damaging and warning behaviors performed by the FPSs were associated with elevated lesion counts on the front of the body (β = 0.03, RR = 1.03, p = 0.012; and β = 0.06, RR = 1.06, p = 0.039, respectively). Affiliative behaviors performed by the older sows were associated with reduced total lesion counts on the FPSs (β = −0.08, RR = 0.92, p = 0.018).

Regarding FPS response behaviors to interactions initiated by the older sow, both retreat and threat were associated with a decreased number of lesions on the front of the body (retreat: β = -0.05, RR = 0.95, p=0.023; threat: β = -0.06, p=0.008) and in total (retreat: β = - 0.06, RR = 0.94, p=0.008; threat: β = -0.59, RR = 0.55, p=0.004). Increased amounts of affiliative behaviors performed by FPSs in response to interactions initiated by the older sow were associated with fewer lesions on the rear of the body (β = −1.71, RR = 0.18, p = 0.017). In contrast, increased damaging behavior by the FPS in response to an older sow’s initiation was associated with increased lesion counts on the front of the body (β=0.31, RR = 1.03, p=0.046).

3.5.1 Interaction effects

Significant interactions were sparse, indicating similar behavior–lesion associations across genetic lines and social mixing environments. However, a consistent pattern was observed for pressing behaviors.

FPSs of the DY line that exhibited higher frequencies of pressing were more likely to have increased lesion scores on the rear of the body and in total (Rear: β = 1.14, RR = 3.14, p = 0.010; Total: β = 0.40, RR = 1.49, p = 0.048), which was not the case for FPSs of the SY line.

Regarding early social mixing environments, FPSs from the CP treatment (i.e., without early social mixing) that performed pressing behaviors had more lesions on both the rear of the body and in total (Rear: β = 1.06, RR = 2.90, p = 0.016; Total: β = 0.41, RR = 1.51, p=0.043). This pattern was not observed among FPSs from the AP treatment. A similar effect occurred when older sows performed pressing toward FPSs from the CP treatment, resulting in more lesions (β = 0.36, RR = 1.43, p = 0.031) compared to pressing toward FPSs from the AP treatment.

Performance of affiliative behaviors was linked to fewer front-body lesions for FPSs of the DY line (β = −0.06, RR = 0.95, p = 0.034). However, affiliative behaviors performed by older sows toward DY FPSs were associated with increased lesion counts on the front (β = 0.06, RR = 1.07, p = 0.026) and in total (β = 0.06, RR = 1.07, p = 0.043). FPSs of the DY line that responded with affiliative behaviors also received more lesions on the rear of the body (β = 1.14, RR = 3.13, p = 0.049) than FPSs of the SY line.

Retreat performed by FPSs as a response to older sow behavior was strongly associated with increased total lesions among DY FPSs (β = 0.05, RR = 1.05, p = 0.011), but not among SY FPSs. Likewise, threat behaviors performed by DY as a response to a social interaction by the older sow led to increased lesion counts on both the front (β = 0.42, RR = 1.52, p = 0.012) and in total (β = 0.37, RR = 1.44, p = 0.013), a pattern not observed in SY FPSs.

Furthermore, retreat as a response behavior by FPSs raised in the MG late social mixing environment was associated with increased lesions both on the front (β = 0.05, RR = 1.05, p = 0.038) and in total (β = 0.05, RR = 1.05, p = 0.022). A similar pattern was observed for MG FPSs responding with threat, as they received more lesions on the front (β = 0.34, RR = 1.41, p = 0.044).

FPSs from the MG treatment that performed damaging behaviors received fewer lesions on the front part of the body (β = −0.02, RR = 0.98, p = 0.039) compared to FPSs from the IG treatment, which remained intact and did not experience late social mixing.

4 Discussion

This study aimed to investigate how genetic lines and social mixing environments during early and late gilt rearing influence social behavior, social responsiveness, and the number of skin lesions in first-parity sows (FPSs) during pairwise interaction tests with an older sow (PIT). The PIT was carried out after the FPS’s litter had been weaned, which is when they would typically be moved to group housing.

Our findings revealed effects of genetic line across several aspects of the social interactions analyzed in this study. In contrast to our prediction, FPSs of the SY line performed higher frequencies of damaging and warning behaviors toward older sows, received more damaging and pressing behaviors, responded more frequently with damaging and pressing behaviors to older-sow-initiated interactions, and accumulated more skin lesions.

In line with our prediction, there were indications that early social mixing experiences affected the number of affiliative behaviors performed toward older sows. FPSs from the access pen (AP) treatment demonstrated significantly more affiliative behaviors when initiating social interactions. They were also more likely to be neutral (i.e., show no behavioral change) following a social interaction initiated by the older sow.

On the other hand, FPSs with late social mixing experience (the MG treatment) showed no consistent main effects on behavior or lesion counts across the full dataset, although behavior-specific effects emerged. FPSs reared in the MG environment received fewer lesions on the front part of the body when performing damaging behaviors, whereas MG FPSs responding with threat or retreat were more likely to sustain front and total lesions. These findings suggest that late social mixing during rearing may shape how individuals react to aversive social interactions, rather than directly modifying overall levels of aggression or affiliative behaviors.

4.1 Genetic line influences social behavior and risk for skin lesion

A consistent pattern emerged across outcome measures, indicating that FPSs of the SY genetic line were more socially engaged than FPSs of the DY line. SY FPSs displayed higher frequencies of both damaging and warning behaviors directed toward the older sow in the PIT and were also more likely to receive such behaviors. This reciprocal pattern suggests a generally higher level of social involvement and/or a more proactive communication style, which is consistent with lower thresholds for contest engagement in more proactive profiles (demonstrated predominantly among younger pigs [Bolhuis et al., 2005)]; however, evidence among adult breeding females is context-dependent (Geverink et al., 2002; Janczak et al., 2003).

SY FPSs also accumulated significantly more lesions following the PIT, notably on the front of the body, the rear, and the legs. Lesions on the front are typically associated with reciprocal or mutual aggression, while lesions on the rear often reflect retreating or defensive behaviors (Turner et al., 2006; Turner et al., 2008). This lesion distribution in SY FPSs supports the interpretation that they were more deeply engaged in agonistic behaviors, both initiating and responding with such behaviors.

Affiliative behaviors had context-dependent associations with lesion outcomes, particularly among FPSs of the DY genetic line. Affiliative behaviors are often used as indicators of social bonds among pigs and sow herds (Durrell et al., 2003; Camerlink et al., 2022). Although post-conflict affiliation has been shown to buffer anxiety in pigs (Norscia et al., 2021), our findings suggest a more nuanced role in FPS lesion outcomes. Affiliative behaviors performed by DY FPSs were linked to fewer lesions, potentially indicating a conflict-dampening effect when initiated by the FPSs themselves. However, affiliative behaviors directed toward DY FPSs by older sows, or used by DY FPSs in response to social interactions, were associated with increased lesions in several body regions. These patterns indicate that affiliative behaviors, especially in tense or unresolved social contexts, may not always reflect harmonious interactions.

While post-conflict affiliation may help de-escalate interactions (Norscia et al., 2021) and buffer the effects of agonistic encounters (Rault, 2012), our findings suggest that affiliation does not uniformly suppress aggression. Similar co-occurrence of affiliative and contest behaviors has been observed during socially unstable periods in finisher pigs (O’Malley et al., 2022). Thus, affiliative interactions should be interpreted with caution, especially in early-stage encounters, as their meaning and welfare implications may depend on both social experience and genetic background.

Although aggression is often viewed negatively from a welfare perspective, given links between repeated injury, stress, and compromised health (Verdon et al., 2015; Maes et al., 2016), the social intensity observed among SY FPSs in the present study may facilitate the rapid formation of dominance hierarchies and more stable group dynamics in the long term (Arey and Edwards, 1998; Verdon et al., 2015). It is important to note that no FPS had to be removed from the group due to injuries sustained during the PIT, indicating that although lesion counts were higher in SY than DY FPSs, the overall severity remained low.

In line with our initial expectations regarding differences in social reactivity, these findings suggest that SY FPSs may express a more socially assertive interaction style in this context. Such assertiveness may hasten rank clarification when competition is constrained but could also elevate short-term injury risk (as reflected in front- and rear-body lesion patterns). In contrast, DY FPSs may follow a more conservative strategy that could reduce immediate risk but potentially prolong uncertainty under contested resources. If so, selection decisions may need to be environment-dependent, considering social-behavior indicators alongside production traits and management strategies that limit contest costs.

4.2 Early social mixing shows associations with affiliative behaviors and responsiveness

The results suggest that early social mixing experiences shaped the social interaction style of the FPSs, particularly within affiliative contexts. FPSs from the AP group displayed more affiliative behaviors than those from the CP group, which aligns with earlier findings that early-life socialization fosters prosocial tendencies and improves social competence (Kutzer et al., 2009; Salazar et al., 2018). This indicates that exposure to unfamiliar conspecifics during early development enhances pigs’ capacity for social engagement.

Notably, FPSs from the AP group were also more likely to maintain their behavior—i.e., show “no change”—when approached by an older sow. Such neutral responses may reflect social tolerance or a less proactive coping style (Rault, 2017). Alternatively, “no change” may indicate habituation due to early social exposure, leading to reduced reactivity to unfamiliar sows, as seen in studies with younger pigs (D’Eath, 2005; Morgan et al., 2014).

Despite these behavioral differences, early social mixing did not influence the likelihood of receiving damaging behaviors, nor did it affect total lesion outcomes. This is consistent with evidence that early socialization can shape social style without necessarily reducing aggression or injuries under competitive challenge (van Nieuwamerongen et al., 2017; Camerlink et al., 2018). Thus, affiliative tendencies may coexist with high social engagement without necessarily lowering the risk of aggressive encounters once competition arises.

Taken together, these findings are consistent with earlier research, primarily from piglets and grow, finisher pigs, which shows that pre-weaning socialization influences later interaction style and can increase affiliative behaviors and social skills/tolerance (Van Putten and Buré, 1997; D’Eath, 2005; Morgan et al., 2014; Camerlink et al., 2018). The results of this study may extend this pattern to FPSs post-weaning.

Future research should assess whether early socialization improves long-term social behavior and group dynamics among sows, since the current dyadic testing setup did not allow evaluation of group-level processes such as hierarchy formation or social stability.

4.3 Context-dependent effects of late social mixing environment

The late gilt-rearing social mixing experience showed no consistent main effects on performed behaviors, received behaviors, response types, lesion outcomes, or latency to contact. This was somewhat unexpected, as prior studies have shown that post-weaning regrouping and group composition can alter aggression (Colson et al., 2006) and elevate physiological stress (Otten et al., 2002).

One explanation may be that although the FPS and older sow were unfamiliar to each other, mixing only two individuals created a relatively small social disturbance, with limited competition. This may have kept post-mixing aggression brief and less intense, particularly when structural features allow avoidance (hay bale) and reduce direct confrontation (e.g., sufficient floor area for withdrawal, bedding, and visual barriers) (Arey and Edwards, 1998; Greenwood et al., 2014). Group size, timing, and the predictability of mixing events are key moderators of regrouping outcomes.

In the present study, FPSs in the MG treatment had been co-housed for an extended period before the PIT, which may have diminished short-term effects.

No effects of MG were found on overall behavioral frequencies or lesion scores across the full dataset; however, effects emerged when specific behaviors were examined. FPSs from the MG group that performed damaging behaviors received fewer lesions on the front of the body. Because front lesions are associated with reciprocal fighting (Turner et al., 2009; Turner et al., 2008), this may indicate that MG FPSs were involved in fewer reciprocal damaging interactions or used more effective engagement strategies in agonistic encounters.

In contrast, MG FPSs that responded with retreat or threat accumulated more lesions on the front and in total, a pattern consistent with greater exposure to aggression in less favorable body positions (O’Connell et al., 2003). This suggests that late social mixing may influence how sows cope with social challenges depending on the behavioral strategy employed.

It is also possible that the PIT, an interaction with a single unfamiliar individual in an unfamiliar setting, highlighted the pigs’ early-life experiences and inherent behavioral traits more than their recent home-pen social environment. Late social mixing did not show consistent overall effects in the PIT setting. However, this does not rule out the possibility that such effects could emerge in a group-housing system with a larger group or under different management conditions.

4.4 FPSs’ behavioral responses to older sows’ behavior

The behavioral responses of FPSs varied depending on the type of behavior displayed by the older sow initiating the social interactions and were not affected by genetic line or social mixing experience when including the older sow’s behavior. Retreat was the most frequent response across all behavior categories in the raw data, particularly following affiliative, damaging, and warning behaviors, suggesting a generally avoidant coping style in these short-term PIT encounters. However, the modeled comparisons revealed a more nuanced response pattern.

When older sows displayed affiliative behaviors, FPSs were significantly more likely to retreat than to respond with affiliative, neutral, or threat behaviors. This suggests that affiliative signals were not consistently interpreted or reciprocated as prosocial opportunities (Camerlink et al., 2014; O’Malley et al., 2022), possibly due to uncertainty in a novel context or a lack of established social familiarity (Arey and Edwards, 1998; Kranz et al., 2022). Rather than fostering social engagement, these cues appeared to trigger social retreat in this PIT.

In contrast, when exposed to damaging behaviors, FPSs mostly responded with either pressing or retreating, significantly more frequently than affiliative or passive responses. This dual strategy likely reflects context-dependent conflict coping, balancing active resistance with tactical retreat (Bolhuis et al., 2005). It may also reflect the intensity of the incoming threat, where retreat is the default but some individuals still engage physically in return (Arey and Edwards, 1998).

Warning behaviors from the older sows, i.e., a lower-intensity signal often interpreted as a threat of escalation (Camerlink et al., 2018), also predominantly elicited retreat. The preference for retreating over responding with a threat or engagement supports the idea that FPSs prioritized de-escalation/avoidance, which has been observed in earlier studies of dry sows (Jensen, 1982), in response to ambiguous or mild threat signals. This behavioral inhibition may reflect adaptive conflict avoidance but could also indicate heightened social caution in novel interactions.

Together, these results suggest that FPS responses were not indiscriminate but flexibly adjusted to the presented social information. The decision to retreat, even in response to affiliative behaviors, may reflect a generally cautious social strategy (Arey and Edwards, 1998), shaped by the unfamiliar testing context and the apparent dominance of the older sow. Retreat may function as an adaptive short-term response to perceived social threat, preventing escalation during potentially risky encounters.

This interpretation is supported by previous findings identifying “Avoider” phenotypes in group-housed sows, characterized by low engagement in aggressive interactions and fewer lesions shortly after mixing (Brajon et al., 2021). However, reliance on such avoidant strategies over time has been associated with increased lesion scores later in the group-housing period (Brajon et al., 2021), possibly due to impaired access to resources, reduced social support, or heightened chronic stress vulnerability. Hence, while retreat may offer short-term protection, it could also limit opportunities for affiliative bonding and social learning.

Overall, these findings highlight the importance of interpreting response behaviors in relation to the initiating social context and recognizing their potential long-term welfare consequences. In this study, while there were effects of early-life social experience, the results suggest that situational appraisal and social novelty remained important under the controlled conditions of the PIT.

4.5 Social initiative and latency to interaction

Most FPSs initiated the first contact with the older sow, regardless of treatment or genetic background, and there were no significant differences in latency to first contact. This suggests that the general motivation to engage socially was high and not clearly differentiated by social mixing environments or genetic lines.

4.6 Methodological considerations and study design reflections

This study employed a category strategy whereby semantically and functionally related behaviors (e.g., nibbling, head knock, parallel pressing) were aggregated into broader categories such as affiliative, damaging, and warning behaviors. Lesions were likewise grouped into anatomically meaningful regions (e.g., front, rear, legs) based on their functional relevance and previous links to social aggression (Turner et al., 2006; Turner et al., 2008). The categories were evidence-based, but we cannot exclude the possibility that another aggregation strategy might have produced different results. Nevertheless, this approach allowed for more meaningful interpretation of social strategies, as isolated actions, such as a single nibble or a lesion on the ear, are difficult to assess without contextual cues. This strategy supported robust and interpretable analyses of complex social behavior and, in particular, a more meaningful interpretation of social strategies.

The standardized PIT setup provided a controlled environment to isolate social response tendencies, but it lacks the dynamic complexity of commercial sow group housing. As a result, generalizability to larger, mixed-age groups or more competitive resource settings is limited. Certain behaviors observed here, such as high retreat rates, may reflect context-specific strategies that differ in commercial environments where more conspecifics are present. On the other hand, a key advantage of the PIT setup is the potential to integrate more detailed information, e.g., physiological data and vocalizations, in future studies.

Across all models, interaction terms were sparse: the links between specific behaviors and lesion patterns were largely consistent across genetic lines and rearing treatments. Within this controlled 60-minute PIT, injury risk appeared to reflect immediate, encounter-level strategies more than background factors. Methodologically, this supports the value of combined behavior–lesion indices as robust indicators of social risk in dyadic tests. However, we note that subtle moderation, which could have continued for several days and weeks, would have gone undetected. Thus, future work should interactions over extended time frames.

In summary, this study’s controlled test design, combined with behavioral and lesion categories, enabled clear detection of group-level patterns relevant to welfare. However, interactions were tested only in pairs of sows over a short period, whereas under commercial conditions pigs are housed in larger groups for much longer. More research linking behavior and lesion outcomes in group settings is needed to identify which FPSs are best suited for group housing systems and to understand how social strategies affect welfare over time.

4.7 Implications for welfare and future directions

To summarize, the findings of the present study suggest that genetic background and early-life social experiences influence how young sows engage in social interactions and their associated risk of physical harm. The observed differences between genetic lines in behavior and lesion accumulation during the PIT were consistent across several measures, though these patterns need to be confirmed in larger groups.

Likewise, early social mixing experience appeared to promote affiliative tendencies and certain passive response strategies but did not clearly reduce the risk of receiving injuries within the short time frame of the test.

From an animal welfare perspective, the combined behavioral and lesion-based outcomes offered a useful framework for assessing social dynamics and identifying risks of negative experiences. Such indicators may serve as valuable tools for developing on-farm methods to monitor sow welfare in group-housed systems.

Future studies should examine how these indicators manifest under commercial conditions with larger groups and over longer periods, and whether combinations of early-life interventions and genotype-informed group structuring, i.e., grouping sows based on behavioral tendencies associated with genetic line, can help mitigate social conflict and reduce injury risk.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by the National Ethics Committee for Animal Experiments in Uppsala (Registration number: 5.8.18-16279/2017). The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

LMBH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LK: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. AW: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by FORMAS, reference number: 2016-01787.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. ChatGPT (OpenAI; model GPT-5, accessed Sep 2025) and Grammarly (Grammarly Inc.; v.1.2.196.1758) were used solely for language editing and formatting. All scientific content, analyses, and conclusions were developed and verified by the authors, who take full responsibility for the manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fanim.2025.1711609/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Albernaz-Gonçalves R. Olmos G. Hötzel M. (2021). My pigs are ok, why change? – animal welfare accounts of pig farmers. Animal15, 100154. doi: 10.1016/j.animal.2020.100154

2

Arey D. S. Edwards S. A. (1998). Factors influencing aggression between sows after mixing and the consequences for welfare and production. Livestock Product. Science.56, 61–70. doi: 10.1016/S0301-6226(98)00144-4

3

(1988). Djurskyddsförordning (1988:539). Available online at: https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/djurskyddsforordning-1988539_sfs-1988-539/ (Accessed March 19, 2025).

4

(2019). Djurskyddsförordning (2019:66). Available online at: https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/djurskyddsforordning-201966_sfs-2019-66/ (Accessed March 19, 2025).

5

Backeman Hannius L. M. Keeling L. de Oliveira D. Anderson C. Wallenbeck A. (2024). Friend or foe: effects of social experience and genetic line on responses of young gilts in a social challenge paired interaction test. Animal18, 101349. doi: 10.1016/j.animal.2024.101349

6

Barnett J. L. Hemsworth P. H. Cronin G. Jongman E. C. Hutson G. D. (2001). A review of the welfare issues for sows and piglets in relation to housing. Aust. J. Agric. Res.52, 1–28. doi: 10.1071/AR00057

7

Bartoń K. (2025). MuMIn: Multi-Model Inference. Available online at: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/MuMIn/index.html (Accessed September 11, 2025).

8

Bolhuis E. Schouten J. Schrama W. G. P. Wiegant V. M. (2005). Individual coping characteristics, aggressiveness and fighting strategies in pigs. Anim. Behaviour.69, 1085–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2004.09.013

9

Boyle L. Carroll C. Mccutcheon G. Clarke S. McKeon M. Lawler P. et al . (2012). Towards January 2013: Updates, implications and options for group housing pregnant sows (Agriculture and Food Development Authority, Fermoy, Co. Cork, Ireland: Pig Development Department, TEGASC).

10

Brajon S. Ahloy-Dallaire J. Devillers N. Guay F. (2021). Social status and previous experience in the group as predictors of welfare of sows housed in large semi-static groups. PloS One16 (6), e0244704. doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0244704

11

Brooks M. Kristensen K. van Benthem K. Magnusson A. Berg C. Nielsen A. et al . (2017). glmmTMB balances speed and flexibility among packages for zero-inflated generalized linear mixed modeling. R J.9, 378–400. doi: 10.32614/RJ-2017-066

12

Camerlink I. Farish M. D’eath R. B. Arnott G. Turner S. P. (2018). Long term benefits on social behaviour after early life socialization of piglets. Animals8, 192. doi: 10.3390/ani8110192

13

Camerlink I. Scheck K. Cadman T. Rault J.-L. (2022). Lying in spatial proximity and active social behaviours capture different information when analysed at group level in indoor-housed pigs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Science.246, 105540. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2021.105540

14

Camerlink I. Turner S. P. Farish M. Arnott G. (2015). Aggressiveness as a component of fighting ability in pigs using a game-theoretical framework. Anim. Behaviour.108, 183–191. doi: 10.1016/J.ANBEHAV.2015.07.032

15

Camerlink I. Turner S. P. Farish M. Arnott G. (2019). Advantages of social skills for contest resolution. R. Soc. Open Science.6, 1-8. doi: 10.1098/rsos.181456

16

Camerlink I. Turner S. P. Ursinus W. W. Reimert I. Bolhuis J. E. (2014). Aggression and affiliation during social conflict in pigs. PloS One9, e113502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113502

17

Chapinal N. Ruiz de la Torre J. L. Cerisuelo A. Gasa J. Baucells M. D. Coma J. et al . (2010). Evaluation of welfare and productivity in pregnant sows kept in stalls or in 2 different group housing systems. J. Veterinary Behavior.5, 82–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jveb.2009.09.046

18

Colson V. Martin E. Orgeur P. Prunier A. (2012). Influence of housing and social changes on growth, behaviour and cortisol in piglets at weaning. Physiol. Behavior.107, 59–64. doi: 10.1016/J.PHYSBEH.2012.06.001

19

Colson V. Orgeur P. Courboulay V. Dantec S. Foury A. Mormède P. (2006). Grouping piglets by sex at weaning reduces aggressive behaviour. Appl. Anim. Behav. Science.97, 152–171. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2005.07.006

20

Council of the European Union (2008). Council Directive 2008/120/EC laying down minimum standards for the protection of pigs. Off. J. Eur. Union, L47/5–L4713.

21

Coutellier L. Arnould C. Boissy A. Orgeur P. Prunier A. Veissier I. et al . (2007). Pig’s responses to repeated social regrouping and relocation during the growing-finishing period. Appl. Anim. Behav. Science.105, 102–114. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2006.05.007

22

D’Eath R. B. (2004). Consistency of aggressive temperament in domestic pigs: The effects of social experience and social disruption. Aggressive Behavior.30, 435–448. doi: 10.1002/AB.20077

23

D’Eath R. B. (2005). Socialising piglets before weaning improves social hierarchy formation when pigs are mixed post-weaning. Appl. Anim. Behav. Science.93, 199–211. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2004.11.019

24

D’Eath R. B. Pickup H. E. (2002). Behaviour of young growing pigs in a resident-intruder test designed to measure aggressiveness. Aggressive Behavior.28, 401–415. doi: 10.1002/AB.80010

25

D’Eath R. B. Turner S. (2010). “ The natural behaviour of the pig,” in The Welfare of Pigs. Ed. Marchant-FordeJ. ( Springer Science, Brisbane, QLD, Australia), 13–45.

26

Dingemanse N. J. Wolf M. (2013). Between-individual differences in behavioural plasticity within populations: Causes and consequences. Anim. Behaviour.85, 1031–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.12.032

27

Durrell J. L. Beattie V. E. Sneddon I. A. Kilpatrick D. (2003). Pre-mixing as a technique for facilitating subgroup formation and reducing sow aggression in large dynamic groups. Appl. Anim. Behav. Science.84, 89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2003.06.001

28