- Department of Animal and Food Sciences, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, United States

Heat stress (HS) poses a critical challenge to modern poultry production, with increasing frequency and severity driven by global climate change. Heat stress impairs feed intake, nutrient absorption, growth, reproduction, immune competence, and welfare, resulting in substantial economic losses. The physiological consequences of HS include acid-base imbalance, endocrine and immune dysregulation, oxidative stress, altered gut integrity, and upregulation of heat shock proteins, which collectively compromise birds’ performance and survivability. Over the years, antibiotics have been incorporated into poultry feed as growth-promoting agents to enhance performance and efficiency; however, they are increasingly restricted due to concerns about antimicrobial resistance and residues in poultry products. To reduce antibiotic use, feed additives have emerged as promising nutritional strategies to mitigate HS-induced effects while serving as effective antibiotic alternatives. This review synthesizes current evidence on antibiotic growth promoters, mycotoxin binders, prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics, postbiotics, exogenous enzymes, and phytochemicals, including essential oils, and their roles in enhancing thermotolerance, nutrient utilization, and overall health in heat-stressed poultry. These additives confer benefits by modulating gut microbiota, strengthening epithelial barriers, enhancing antioxidant and anti-inflammatory capacity, stabilizing immune and endocrine responses, and improving skeletal and eggshell integrity under high ambient temperatures. Dietary feed additives offer sustainable, non-antibiotic approaches to support poultry resilience, productivity, and welfare under the pressures of HS and the broader challenges of a warming climate. Future research should focus on mechanistic pathways, optimal dosing, and synergistic additive combinations tailored to species, age, and production systems to maximize thermotolerance and production efficiency.

1 Introduction

1.1 Climate change and heat stress in poultry

The rising global temperature, caused by climate change, poses a significant problem for poultry production, leading to increased disease prevalence, reduced feed quality and availability, and an increased prevalence of heat stress (HS). The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, in its Fifth Assessment Report, reported an average global Earth surface temperature rise of approximately 0.9 °C (1.62 °F) since the mid-20th century (IPCC, 2014). Also, projections suggested that this temperature change could be between 1.4 and 5.8 °C by the 21st century (IPCC, 2014). High temperature is a significant stressor to poultry, with substantial impacts on health and productivity (Hu et al., 2022b; Sun et al., 2023). The selective breeding practices implemented over several decades have significantly enhanced growth rates and feed efficiency in poultry (Sulaiman et al., 2025). However, these beneficial characteristics are accompanied by higher metabolic activity, which makes birds more vulnerable to HS (Nawaz et al., 2023). Generally, birds raised under high environmental temperatures exhibit decreased feed intake (FI), lower nutrient utilization, slower growth rate, poorer eggshell quality, and increased mortality (Kpomasse et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2023). In 2011, the economic loss in agricultural production associated with high temperatures was estimated to exceed $1 billion (Hatfield et al., 2014). In 2003, St-Pierre et al. (2003) reported that the poultry industry experienced losses estimated between $128,000,000 and $165,000,000 due to HS. As global temperatures rise, the poultry industry is prone to more frequent and intense HS occurrences, posing significant challenges to production and welfare. Consequently, the associated economic losses are expected to increase in the future, thereby necessitating the development of effective mitigation strategies. Dietary supplementation has gained considerable attention as an effective means of enhancing poultry resilience to HS.

Poultry are homeothermic, maintaining a relatively narrow core body temperature range. Unlike mammals, birds lack sweat glands and dissipate excess body heat primarily through panting and peripheral vasodilation. These mechanisms are energy-demanding (Mota-Rojas et al., 2021) and often inadequate during persistent or extreme heat exposure, resulting in HS. During HS, the heat generated by birds exceeds their dissipation capacity. The onset of HS triggers a cascade of physiological and behavioral responses aimed at maintaining homeostasis. Birds reduce their FI to limit metabolic heat production, increase water consumption, and adjust their postural and activity patterns to improve heat dissipation (Soliman and Safwat, 2020). While these strategies may limit hyperthermia, they compromise nutrient intake, growth rate, and reproductive output (Sesay, 2022). At the systemic level, HS induces respiratory alkalosis through excessive carbon dioxide loss during panting (Teeter et al., 1985), which disrupts the blood acid-base balance and impairs calcium availability, thereby adversely affecting eggshell quality (Kim et al., 2024). Additionally, HS alters endocrine function by modulating thyroid (Beckford et al., 2020) and corticosterone secretion (Soliman and Safwat, 2020), influencing metabolism, feed efficiency, and immune competency.

Heat stress increases the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cells, leading to oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction (Kikusato et al., 2015). This imbalance damages lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, initiating apoptotic pathways and compromising tissue integrity. The gastrointestinal tract is particularly vulnerable, with compromised tight-junction proteins, disrupted epithelial barrier function, and dysbiosis. These alterations reduce nutrient absorption and increase susceptibility to enteric pathogens and endotoxemia, further impairing performance. Additionally, HS upregulates the synthesis of heat shock proteins (HSPs), which function as molecular chaperones to stabilize misfolded proteins and regulate immune signaling (Hu et al., 2022a). Although protective, persistent HSP activation reflects chronic cellular stress and diverts resources away from productive processes.

1.2 The emergence of feed additives in poultry production

The poultry industry faces several challenges, including diseases, animal welfare concerns, food safety issues, and environmental concerns, such as high temperature, which impact productivity. Historically, poultry diets have relied heavily on nutritional supplements, including vitamins and minerals, to supply nutrients for optimal growth. However, in the last few years, the use of dietary non-nutritive feed additives for enhancing poultry growth and gut health has emerged. Ayalew et al. (2022) defined feed additives as “non-nutritive substances added to feed to improve animal health, enhance feed quality, optimize nutrient utilization, and boost growth performance.”

One of the earliest feed additives used in poultry is antibiotic growth promoters (AGPs) due to their ability to enhance growth (Perera and Ravindran, 2025). Antibiotic growth promoters are sub-therapeutic doses of antibiotics added to animal feed to increase live weight gain (WG) and improve feed efficiency in food-producing animals (Etienne et al., 2025). It is believed that they exert their mechanistic effects by modifying gut microbiota, protecting nutrients from microbial destruction, improving nutrient absorption, reducing bacterial toxins, and lowering subclinical infections (Perera and Ravindran, 2025). Antibiotic growth promoters function by modifying the microbial community in the animal’s gut, reducing bacteria that produce harmful metabolites or compete with the host for nutrients or divert nutrients away from the animal’s use (Kalia et al., 2022). Also, the gut microflora composition is maintained by AGPs through thinning of the small intestine barrier. This reduction in microbial competition and intestinal barrier thinning enhances nutrient absorption, allowing the animal to utilize feed more efficiently and achieve faster growth (Peng et al., 2014). Additionally, AGPs exert a low-level anti-inflammatory effect, helping to reduce subclinical infections and immunological stress, further supporting overall health and performance. Although AGPs have been highly effective, concerns over residues in animal products and human antibiotic resistance have led to partial or complete bans in many countries (Adedokun and Olojede, 2019).

As the global demand for poultry products continues to rise, innovative solutions are needed to address the challenge of sustainability, disease control, and consumer preferences for antibiotic-free products (Regan et al., 2022). Moreover, the evolution of feed additives has been driven by the need to enhance poultry productivity while mitigating environmental impacts and ensuring good animal welfare. Some common feed additives used in poultry as alternatives to AGPs include prebiotics, probiotics, enzymes, coccidiostats, mycotoxin binders and deactivators, mold inhibitors, antioxidants, organic acids, and phytogenics (Pirgozliev et al., 2019; Ayalew et al., 2022; Perera and Ravindran, 2025). Research has demonstrated the importance of these additives in enhancing gut health, strengthening the immune system, increasing nutrient absorption, and mitigating the adverse impacts of environmental stressors like heat. The role of nutritional supplements, supplying essential nutrients in alleviating HS effects in poultry, has recently been reviewed (Olayiwola and Adedokun, 2025). Feed additives, including prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics, postbiotics, phytochemicals, and enzymes, have been shown to modulate physiological responses and improve birds’ tolerance to high ambient temperatures (Olgun et al., 2021). Thus, this review assesses the efficacy and mechanisms of selected feed additives in alleviating HS and supporting gut health in poultry. It synthesizes evidence on how probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, postbiotics, enzymes, and phytochemicals modulate avian physiological, oxidative, and immunological responses under HS.

2 Direct impacts of heat stress on poultry production

2.1 Heat stress impact on growth

Birds’ response to HS depends on the frequency and severity of heat. Literature has consistently shown that birds exposed to high temperatures eat less feed as an adaptive behavior to minimize metabolic heat production from digestion (Nawaz et al., 2021; Teyssier et al., 2022). At the expense of feeding, heat-stressed broilers spend more time panting and resting to dissipate excess heat. This reduces the amount of ingested nutrients, leading to reduced growth. In the study by Sohail et al. (2012), heat-stressed birds (35 ± 2 °C) consumed less feed, had lower body weight (BW), and a higher feed conversion ratio (FCR) compared to the control at day 42. In turkeys, FI was observed to decrease by about 2.3% for every degree Celsius rise in environmental temperature from 18 °C up to 28 °C (Hurwitz et al., 1980).

The negative impact of HS on feed efficiency and growth partly occurs because maintenance energy expenditure rises, due to panting and elevated heart rate. This suggests that birds exposed to HS divert energy away from growth and muscle accretion to cope with the stress (Wasti et al., 2020). Heat-stressed birds often metabolize nutrients less effectively, depositing more fat and less lean tissue (Brugaletta et al., 2022). Additionally, HS damaged the intestinal epithelial cells, leading to reduced villus height, increased crypt depth, reduced villus:crypt depth, and intestinal permeability (Liu et al., 2022a). These intestinal morphological changes hinder nutrient absorption, resulting in poor feed efficiency and growth.

2.2 Heat stress impact on intestinal health

The gastrointestinal tract is the boundary between the host organism and the external environment, facilitating nutrient digestion and absorption. It houses a population of microbes, which enhances digestion when the gut microbiome is balanced. Also, the intestinal epithelium acts as the primary defense against pathogens, thereby supporting the gut’s immune function. The intestinal tract is susceptible to HS, with research showing that high temperatures can damage the gut mucosa, alter its morphology, and compromise its barrier function (Smith et al., 2022; Rezar et al., 2024). Mucosal damage and morphological changes occur due to a reduction in the distribution of nutrients and oxygen from low blood supply to the epithelial cells (Rostagno, 2020). Laying hens exposed to 34 °C for 12 days had reduced villus height, increased crypt depth, and reduced villus:crypt in the ileum when compared to those exposed to normal temperature (Deng et al., 2012). Wu et al. (2018) reported a similar result when broilers were subjected to 33 ± 1 °C for 10 h/d during day 22-41. The villus:crypt is an important index of intestinal health and functional capacity, with a high ratio signifying long, mature villi relative to crypt depth, which is optimal for nutrient absorption. In contrast, a lower ratio suggests villus atrophy or crypt hyperplasia, which is indicative of mucosal stress or accelerated turnover (Deng et al., 2012).

Under normal conditions, the intestinal epithelium functions as a selective barrier, allowing nutrient uptake while inhibiting the passage of toxins and pathogens. Under HS, this barrier becomes “leaky,” leading to tight junction disruption, pathogenic inflammation, and reduced blood flow to the gut (Olayiwola and Adedokun, 2025). During HS, blood is redistributed towards the skin surface to dissipate excess heat, resulting in ischemia of the gut lining, which reduces nutrient and oxygen delivery to intestinal tissues (Lambert, 2009). As parts of the gut undergo mild hypoxia and nutrient deprivation, this weakens the epithelial layer (Yan et al., 2006), triggering a pro-inflammatory response in the gut. Heat-stressed broilers showed higher tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) but lower interleukin-10 (IL-10) levels in the jejunum and ileum than those at normal temperatures (Wu et al., 2018). In laying hens, HS increases TNF-α, interleukin-1 (IL-1), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels (Deng et al., 2012). Excessive production of proinflammatory cytokines disrupts the tight junction proteins that seal the gaps between intestinal cells, thereby increasing intestinal permeability. Moreover, HS increases the risk of inflammation by downregulating the expression of tight junction proteins (claudin-1, occludin, and Zonula occludens-1), while increasing the concentration of Soluble Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1 (sICAM-1) (Wu et al., 2018). With the barrier compromised, bacterial endotoxins (lipopolysaccharides) from the gut lumen can translocate into the bloodstream.

2.3 Heat stress impact on the gut microbiota

Maintaining the balance of beneficial microbiota is crucial for a healthy gut microbiome and overall physiological stability. Heat stress alters the composition of poultry gut microbiota through the microbiota-gut-brain axis (Table 1). Cao et al. (2021) documented the mechanisms underlying this process, which are beyond the scope of this review. Ncho (2025) conducted a systematic review on the impact of HS on poultry gut microbiota with reports on alpha and beta diversity, abundance of phyla, and lower taxonomic levels. While alpha diversity measures the variety of species (richness and evenness) within a single community, beta diversity compares the species composition between two or more communities, indicating how different they are from each other (Andermann et al., 2022). The findings on alpha diversity are inconsistent, with the majority reporting non-significant effects of HS on alpha diversity (Xing et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020a; Zhou et al., 2022), with only a few observing an increase in richness or evenness (Wang et al., 2018b; Liu et al., 2023), and a decrease in evenness (Zhang et al., 2023). These inconsistencies are likely due to experimental differences, including the initial microbial state before heat exposure, age at HS exposure, and the type of heat challenge (Ncho, 2025). Cyclic HS, which simulates natural temperature fluctuations and involves shorter exposure periods than chronic HS, may not be intense enough to induce significant changes in alpha diversity. Emami et al. (2022) and Liu et al. (2023) observed that the increase in richness and evenness could be due to the proliferation of pathogenic bacterial populations, including E. coli, Salmonella spp., and Weissella spp.

Contrary to its effect on alpha diversity, several studies reported a significant impact of HS on beta diversity, which is dependent on the bird’s age and the duration of HS exposure (Ncho, 2025). Older birds often exhibit stronger, heat-induced shifts in cecal microbiota, and the beta diversity changes are more pronounced in chronic HS. Exposure to HS alters the relative abundances of the chicken gut phyla, including Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, and Tenericutes, with changes in the latter two being more consistent (Wang et al., 2018b; Liu et al., 2023). Proteobacteria increase under HS, indicating dysbiosis and inflammation, which are often linked to oxidative stress that promotes the growth of facultative anaerobes over the obligate ones (Ncho, 2025). Similarly, the relative abundance of Tenericutes increases under HS due to their flexible cell membranes, which offer greater resilience to environmental stress and enable them to maintain their population as commensal bacteria decline. Ncho (2025) revealed that HS reduces the beneficial genera Faecalibacterium and Ruminococcus. The decline in Faecalibacterium, a dominant genus crucial for colonic mucosal health and butyrate production, is often associated with diseases (Cao et al., 2014). Similarly, Ruminococcus, which produces volatile fatty acids that protect the jejunal mucosa, decreased due to reduced nutrient absorption and oxidative stress under HS (Ncho, 2025). Conversely, HS promoted the proliferation of pathogenic bacteria, such as Escherichia coli, Enterobacter, Shigella, Salmonella, and Weissella, all of which are associated with inflammation and gut dysbiosis (Ncho, 2025).

2.4 Heat stress impact on immune function

The central nervous system exerts regulatory effects on immune responses through an intricate network of signaling mechanisms between the immune, endocrine, and nervous systems (Figure 1). Stress modulates immune function through the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) and sympathetic-adrenal-medullary (SAM) axes. This induces the secretion of glucocorticoids and catecholamines, which in turn activate various immune cells, like granulocytes, lymphocytes, macrophages, and monocytes, which possess receptors for the neuroendocrine products (Lara and Rostagno, 2013). When this occurs, antibody production, cytokine secretion, cellular trafficking, proliferation, and cytolytic activities undergo modifications. For instance, the glucocorticoid receptor binds to corticosterone, which disrupts nuclear factor kappa light chain enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) function, thus regulating cytokine-producing immune cell activity (Padgett and Glaser, 2003).

Figure 1. Immune system responses to heat stress. Stress induced the activation of the HPA and SAM axes, leading to the release of immune modulators (glucocorticoids and catecholamines) and subsequent immune cell activation. Immune cells such as monocytes, lymphocytes, granulocytes, and macrophages are involved in antibody production, cytokine secretion, and cellular trafficking.

Researchers have investigated the impact of HS on poultry immunity, including damage to the immune organs. Studies have reported that the primary (thymus and bursa of Fabricius) and secondary (spleen) immune organs, and liver showed reduced relative weights in laying hens exposed to HS (Niu et al., 2009; Quinteiro-Filho et al., 2010; Felver-Gant et al., 2012; Ghazi et al., 2012). These reductions could be associated with cellular atrophy resulting from elevated corticosterone levels, oxidative stress, and reduced nutrient intake. Corticosterone, released through activation of the HPA axis, suppresses lymphocyte proliferation, induces apoptosis, and inhibits antibody synthesis (Tang and Chen, 2016). Quinteiro-Filho et al. (2017) opined that a reduction in immunoglobulin A (IgA) plasma levels is likely due to elevated corticosterone levels caused by increased temperatures, which then result in extended cell lysis, disrupted B-cell activities, and reduced immunoglobulin synthesis. During primary and secondary immune responses, heat-stressed broilers showed reduced total circulating immunoglobulin G and immunoglobulin M (Bartlett and Smith, 2003), indicating suppressed humoral immunity. Also, acute HS reduced the phagocytic capacity of macrophages in chickens’ jejunum (Quinteiro-Filho et al., 2012), due to oxidative damage and energy reallocation from immune function to thermoregulation. All these mechanisms weaken the innate and adaptive immune defenses, making birds more susceptible to pathogens and their metabolites.

Furthermore, the level of cytokines in poultry is affected by HS. Xu et al. (2014) revealed that HS upregulated TNF-α and interleukin-4 (IL-4), while concurrently decreasing levels of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and interleukin-2 (IL-2) in chickens. According to Heled et al. (2013), alterations in cytokine levels within tissues are indicative of an immune shift from type 1 (Th1) to type 2 (Th2) helper T cells. This shift results in increased IL-4 levels, suppressing Th1 cell activation and partly reducing IL-2 secretion (Lu et al., 2004). Interferon-gamma and IL-2 are key Th1 cytokines crucial for stimulating macrophages, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, and natural killer (NK) cells (Ivashkiv, 2018; Chen et al., 2023). Their reduced levels indicate a weakened resistance to intracellular pathogens, like viruses and certain bacteria. An upregulation of IL-4 and IL-6 suggests a Th2 shift, enhancing antibody (humoral) responses. However, this is only beneficial against extracellular threats, as the ability to combat infected cells is compromised, with a higher risk of allergies, autoimmunity, and oxidative tissue damage.

Similarly, Starkie et al. (2005) observed that HS stimulated pro-inflammatory signaling by increasing TNF-α and interleukin-1 alpha (IL-1α) in cells. Increased levels of interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), IL-6, and TNF-α signals indicate strong local inflammation in the intestine. Prolonged inflammation can compromise gut epithelial integrity (loosened tight junctions), disrupt microbial balance, and impair nutrient absorption, which may contribute to systemic leakiness (endotoxemia) (Meng et al., 2022; Al-Zghoul et al., 2025). Over time, chronic inflammation can lead to immune exhaustion, resulting in reduced pathogen clearance. Chickens exposed to 39 °C for 7 h/day from day 35 to 41 had reduced CD4+ and CD8+ cells (Khajavi et al., 2003). This reduction exacerbates the impact of reduced Th1 signaling, resulting in diminished cytotoxic activity and weakened immune surveillance.

The innate immune system of animals recognizes microbial infections by utilizing germline-encoded pattern recognition receptors. Through pattern recognition receptors, toll-like receptors (TLRs) can identify several pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), making them pivotal in triggering innate immune responses (Kawai and Akira, 2009). Heat stress influences TLR expression due to its impact on the neuroendocrine and antioxidant systems. When birds experience heat stress, the HPA axis is activated, driving the release of corticosterone as part of the stress response, which in turn reduces immune surveillance. This hormonal signaling downregulates TLR-2 in lymphoid tissues like the spleen and cecal tonsils, contributing to suppressed innate immune detection of bacteria (Quinteiro-Filho et al., 2017). Since TLR-2 recognizes bacterial lipopeptides, its reduction weakens detection and response to pathogens like Salmonella, leading to higher bacterial loads and systemic spread under HS (He et al., 2019a). Contrarily, HS increased toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4) expression in the jejunum and ileum (Varasteh et al., 2015) as a damage-sensing response to detect and resolve inflammation in the gut lumen. An upregulation of TLR-4 in the intestinal mucosa stimulates NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways, resulting in the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL−1β, TNF-α, IL-6 (Kim et al., 2023). Although this enhancement may strengthen defense mechanisms, chronic inflammation can compromise epithelial integrity.

2.5 Heat stress impact on oxidative stress

Oxidative stress occurs when there is a disproportion between pro-oxidant and antioxidant systems within biological systems. This is characterized by the presence of excessive reactive species, including ROS, reactive nitrogen species (RNS), and reactive chlorine species, beyond the antioxidant capacity in animal cells (Halliwell and Whiteman, 2004). Reactive oxygen species are oxygen (O2) metabolites with an unpaired electron, which is obtained from molecular O2. At low concentrations, ROS act as critical stimulators and modulators of cellular signaling pathways, thereby influencing cellular behavior (Akbarian et al., 2016). Excessive RNS and ROS production can trigger free radical-mediated chain reactions that damage macromolecules, including polysaccharides, proteins, and lipids, thereby activating the apoptosis intrinsic pathway (He et al., 2019b).

The mitochondria are the main organelles responsible for O2 metabolism, utilizing about 85-90% of the O2 within cells (Belhadj Slimen et al., 2014), which are mostly derived from oxidative phosphorylation (Akbarian et al., 2016). Under HS conditions, mitochondria produce increased amounts of superoxide anions (O2-), the first by-product generated during oxygen reduction (Kikusato et al., 2015). This reaction takes place at specific spots in the electron transport chain (ETC), which is the primary O2- producer under HS conditions (Kikusato et al., 2010). Heat stress reduces superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD-1) mRNA expression and lowers the levels and activity of cytoplasmic SOD protein, resulting in increased ROS production (Lee et al., 2004). Furthermore, high temperatures can lead to excessive production of transition metal ions, promoting electron flow to O2 and consequently producing hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) or O2- (Belhadj Slimen et al., 2016). Superoxide anions are highly reactive and have difficulty moving through cell membranes.

The cell requires its own antioxidant system for maintaining ROS homeostasis and protecting itself from damage, especially in the mitochondria. The mitochondrial antioxidant defense is categorized into two main systems. The first system consists of enzymatic antioxidants, which include catalase (CAT), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), and SOD (Tan et al., 2010), while the second system is the low molecular weight non-enzymatic antioxidants, comprising glutathione, uric acid, and vitamins (Torki et al., 2014; Attia et al., 2016). Catalase, GSH-Px, and SOD are designated to work together, primarily protecting against oxidative stress by inhibiting and scavenging the generation of ROS in living cells. Their actions also influence the stability of lipids by reducing oxidation in poultry meat during storage (Bai et al., 2016). Superoxide dismutase breaks down O2- into H2O2 and O2, while catalase and GSH-Px convert H2O2 into water. The removal of superoxide radicals by SOD prevents the formation of peroxynitrite, a more damaging substance. Superoxide dismutase and GSH-Px work together to counterbalance oxidant attacks, protecting the cells from DNA damage.

Heat stress perturbed the antioxidant system homeostasis by increasing ROS production while inhibiting antioxidant enzyme activity and expression (Lin et al., 2006; Azad et al., 2010). Acute exposure to HS stimulates the antioxidant defense system, markedly increasing the activities of CAT, SOD, and GSH-Px to protect cellular structures (Lin et al., 2006; Tan et al., 2010). Also, Altan et al. (2003) reported heat-stressed broilers exhibited markedly elevated serum activities of CAT, GSH-Px, and SOD compared to the thermoneutral broilers. Furthermore, chronic-cyclic HS enhanced SOD and GPx activities in the breast muscle of broilers, resulting from the body’s response to the ROS produced due to prolonged HS exposure (Azad et al., 2010). Contrarily, chronic HS reduced GSH-Px and SOD activities, suggesting a weakened antioxidant defense in broilers, while CAT activity showed no significant changes (Cramer et al., 2018).

According to Kikusato and Toyomizu (2013), HS increases the levels of H2O2 and hydroxyl radicals (OH-). Cells have antioxidant enzymes like SOD (Mn-SOD and Cu/Zn-SOD), which convert superoxide into H2O2, supporting the production of harmful OH- radicals (Akbarian et al., 2016). Nitric oxide is a highly reactive free radical that plays a vital role in cell signaling and metabolism due to its high reactivity. The extent of oxidative stress can be assessed by measuring the conversion of arginine to citrulline, a reaction catalyzed by nitric oxide synthase, which requires nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate. Superoxide dismutase is inactivated when nitric oxide combines with O2- to produce peroxynitrite (Steinmann et al., 2004).

The level of antioxidant enzyme activity varies during chronic HS. Exposing black-boned chickens (Ayam Cemani; native to Indonesia) to chronic HS at 37 ± 2 °C decreases serum CAT, GSH-Px, and SOD activities (Liu et al., 2014a). Birds exposed to cyclic HS at 33 °C had reduced serum activities of CAT and GSH-Px (Zhang et al., 2017). Also, broilers subjected to continuous chronic HS for 21 days showed increased activities of erythrocyte GSH-Px (Pamok et al., 2009). Acute HS triggers mitochondrial substrate oxidation and activates the ETC, leading to increased O2- production, which exacerbates oxidative stress by downregulating avian uncoupling protein (He et al., 2019b). This downregulation results in mitochondrial dysfunction and tissue damage. Notably, the activities of SOD, CAT, and GSH-Px are upregulated. Contrarily, chronic HS decreases metabolic oxidative capacity by upregulating uncoupling protein and depleting antioxidant reserves because of inhibited antioxidant enzyme activity (Akbarian et al., 2016). Therefore, variations in the activities of antioxidant enzymes are influenced by the types of HS, the tissues involved, and the species. Heat stress impairs the response of the mitochondrial ETC, leading to an overproduction of ROS that causes oxidative stress (Miova et al., 2016). This includes induced oxidation of mitochondrial proteins, peroxidation of lipids, and DNA damage (Belhadj Slimen et al., 2014), causing cell apoptosis (Green and Kroemer, 2004).

2.6 Heat stress impact on heat shock proteins

Heat shock proteins act as molecular chaperones that facilitate protein folding and stability in response to cellular stress (Hu et al., 2022a). These proteins are categorized based on their molecular weights into large HSPs, such as heat shock proteins 40 (HSP40), 60 (HSP60), 70 (HSP70), 90 (HSP90), and 110 (HSP110), and small HSPs, like heat shock proteins 22 (HSP22) and 27 (HSP27). They are found in several subcellular sections, including the nucleus, cytoplasm, endoplasmic reticulum, and mitochondria of eukaryotic cells. Each HSP has specific chaperone functions, including participating in various cellular processes that contribute to maintaining cellular integrity, supporting protein folding and balance, preventing misfolded protein aggregation, aiding in protein degradation, and facilitating antigen presentation, all of which are vital during cellular stress responses and immune activation (Muralidharan and Mandrekar, 2013). Moreover, they exert regulatory effects on the cell cycle, apoptosis, and signaling transduction (Hu et al., 2022a). Environmental stressors, including HS, oxidative stress, nutrient deficiency, toxins, and infectious agents, can stimulate their expression (Muralidharan and Mandrekar, 2013). Depending on their location (intracellular or extracellular) and the participating immune cells, HSPs may initiate inflammatory signaling that activates the immune response to combat infections, or they can provide an anti-inflammatory signal that suppresses the immune response to avoid excessive inflammation (Kaul and Thippeswamy, 2011). In stressful environmental conditions, birds experience an increase in ROS as their bodies work to maintain thermal balance. This leads to oxidative stress, prompting the production of HSPs to mitigate the harmful effects of ROS (Dröge, 2002).

2.6.1 Small heat shock proteins

The small HSPs, HSP27 and HSP22, have been shown to exhibit immunomodulatory roles. Heat shock protein 27 promotes MAPK and NF-κB pathways activation and exhibits proinflammatory effects during viral infections (Muralidharan and Mandrekar, 2013); however, it can also enhance anti-inflammatory interleukin-10 production, supporting monocytes differentiation into inhibitory dendritic cells (Miller-Graziano et al., 2008). However, HSP22 acts as a TLR-4 agonist and is highly expressed in autoimmune pathologies such as rheumatoid arthritis (Roelofs et al., 2006).

2.6.2 Large heat shock proteins

Heat shock protein 110 acts as a potent chaperone during hyperthermia and has been used in immunotherapy models to deliver antigens and stimulate immune responses (Facciponte et al., 2007). Heat shock protein 90 stabilizes unfolded proteins by stopping aggregation and supporting their functional recovery through interactions with client-substrate proteins during late folding stages. Heat shock protein 90 is notable for its interaction with immune signaling intermediates. Immune signaling client proteins of cytoplasmic HSP90 comprise transcription factors and kinases, including interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3), inhibitory-κB kinase (IKK), and TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) (Yang et al., 2006). Heat shock protein 90 modulates the functional state of its client proteins, exerting effects through direct interactions and indirect regulatory mechanisms. For example, while HSP90 is required for activating the IKK complex, it simultaneously suppresses noncanonical NF-κB by stabilizing Monarch-1 and promoting the breakdown of NF-κB-inducing kinase in macrophages (Arthur et al., 2007). Heat shock protein 90, located in the endoplasmic reticulum (gp96), plays a key role in the maturation and membrane expression of TLRs, including TLR-4, TLR-7, and TLR-9, in macrophages (Yang et al., 2007). Also, HSP90 helps to activate natural killer and T cells for optimal function (Bae et al., 2013).

Heat shock protein 70 is central to multiple cellular processes, including modulating immunity, ensuring proper folding of new and stress-denatured proteins, disassembling unfolded protein aggregates, and transporting proteins into specific cellular compartments (Young, 2010). Extracellular HSP70, often released during cell death or through active secretion, serves as a damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP), activating receptors on immune cells and triggering monocytes and dendritic cells’ TLR-2 and TLR-4 pathways to produce inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (Torigoe et al., 2009). Besides its proinflammatory roles, HSP70 may also exert anti-inflammatory effects to protect against tissue damage. The overexpression of HSP70 in humans impedes lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced cytokines, like IL-1β and TNF-α, in macrophages (Ding et al., 2001). In macrophages, HSP70 expression prevents NF-κB activation triggered by LPS by binding to TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF-6) and blocking its ubiquitination. This action prevents the inflammatory signaling cascade (Chen et al., 2006). HSP70 blocks IkappaB (IκB) degradation and prevents NF-κB from entering the nucleus, indicating that suppressing the NF-κB pathway is responsible for the LPS tolerance induced by HSP70 in macrophages (Dokladny et al., 2010). Heat shock protein 70 associates with and suppresses Jun-N-terminal kinase (JNK) activation in fibroblasts within the MAPK signaling pathways (Dokladny et al., 2010).

Heat shock protein 60 is dominant in the mitochondria, critical for intracellular protein trafficking, and exhibits immune-modulating functions. It can stimulate inflammatory cytokine production (e.g., TNF-α and IL-12) through CD14-mediated signaling in macrophages. On the contrary, it may also suppress immunity by inhibiting NF-κB activity in T cells (Dokladny et al., 2010) and enhancing regulatory T cell (Treg) function via TLR-2 signaling, reflecting its complex role in immune regulation (Dokladny et al., 2010). Heat shock protein 40 functions as co-chaperone for HSP70, enhancing its ATPase activity and folding capacity (Facciponte et al., 2007). Certain HSP40 familyvmembers, like DNAJA3, suppress inflammation by stabilizing IkB and inhibiting NF-kB activation (Cheng et al., 2005). Research has shown that HS increases levels of HSP70 in broilers and laying hens (Felver-Gant et al., 2012; Gu et al., 2012).

Among the HSPs, HSP70 stands out due to its multifaceted and central function in cellular homeostasis. It is present in all cellular compartments, including the cytosol, endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, and nucleus. Due to its larger presence and versatility, HSP70 is involved in several cellular processes, from protein production to degradation, making it indispensable for cellular function. Additionally, it serves as a central hub in the cellular chaperone network, interacting with various co-chaperones and other chaperone systems like HSP90 and HSP60 (Fernández-Fernández and Valpuesta, 2018). This interconnected network ensures the coordinated folding, stabilization, and degradation of proteins, highlighting HSP70’s pivotal role in proteostasis (Bhattacharjee et al., 2025).

2.6.3 Heat shock factors

Heat shock factors (HSFs), particularly heat shock factor-1 (HSF1), regulate many HSPs expression (Pirkkala et al., 2001). Heat shock factor-1 can reduce inflammation by repressing the transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines, like IL-1β in LPS-stimulated monocytes (Xie et al., 2002) and TNF-α in macrophages (Singh et al., 2004). Heat shock factor 1 competes with NF-κB for binding to gene promoters, thereby modulating the inflammatory environment during stress responses. The heat shock response (HSR) is activated when poultry are exposed to high temperatures. This involves the upregulation of HSPs, primarily through the activation of HSF1, which binds to heat shock elements (HSEs) in the promoter regions of HSP genes, leading to their transcriptional activation. On exposure to high temperature, HSPs expression increased in black-boned chickens’ bursa of Fabricius and spleen (Liu et al., 2014b), and broiler chickens’ spleen (Xu et al., 2014), and liver (Wang et al., 2018a).

3 Indirect impacts of heat stress on poultry production

Plant-based sources comprise approximately 80% of the ingredients used in poultry feed (Adedokun and Olojede, 2019), with cereal grains comprising over 50% in typical poultry diets (Ledvinka et al., 2022). Globally, HS is having devastating effects on crop production, causing significant challenges for food and livestock feed production. Elevated temperatures during the growing season negatively affect grain development, yield, and quality, especially during critical growth stages (Farhad et al., 2023). Excessive heat during the reproductive phase of cereals may lead to fewer grains, lighter grain weight, slower grain filling, and reduced grain quality (Majoul-Haddad et al., 2013). Maize and soybean yields are significantly reduced by high temperatures and low precipitation (Wing et al., 2021). High heat interferes with normal starch deposition in the developing kernel, with broken grains resulting in lower starch content, overall yield, and less digestible energy per unit feed. Also, the composition of heat-stressed grains is modified, showing increased protein content but a decrease in essential amino acids (Farhad et al., 2023). Such changes can decrease the nutritional value of feed grains used for poultry feed, resulting in low-quality feed.

Mycotoxins are metabolites of filamentous fungi that often contaminate cereal grains, especially in warm, humid conditions. When animals ingest them, they can trigger a range of adverse physiological responses (Paczosa et al., 2025). Birds fed with mycotoxin-contaminated diets experience decreased FI and poor WG, partly because of the toxins damaging the gastrointestinal tract and impairing nutrient absorption. Long-term temperature and humidity shifts are altering the distribution of mycotoxins. For instance, the warming climate trends have led to the migration of Aspergillus and Fusarium mycotoxins from southern Europe to central and northern Europe, respectively (Paterson and Lima, 2017). In the past, about 25% of the world’s food and feed crops were estimated to contain detectable mycotoxins, but due to increasing global temperature and improved detection methods, newer studies indicate that over 80% of agricultural commodities may now be contaminated at some level (Eskola et al., 2020). Researchers have warned that as climate extremes intensify, regions may likely face both higher levels of native mycotoxins and the emergence of unfamiliar toxins in new areas. This poses a serious challenge for food safety and animal feed quality in the coming decades (EFSA et al., 2020).

The combination of degraded grain quality and increased mycotoxin incidence due to HS has an adverse impact on poultry nutrition and health. Low yield and poor quality of grains result in lower nutritional density, leading to impaired poultry performance. Also, the greater mycotoxin contamination of grains can cause overt toxicity, including gut lesions, organ damage, and disease susceptibility in birds consuming contaminated feed.

4 Feed additives used in poultry for alleviating heat stress

4.1 Prebiotics

Prebiotics are non-digestible feed additives, often complex carbohydrates like inulin, fructo-oligosaccharides, and mannan-oligosaccharides, which bypass the upper GIT digestion to act as substrates for beneficial gut microbes in the colon (Abd El-Hack et al., 2022). These additives escape to the lower gut, where commensal bacteria, including Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, ferment them into short-chain fatty acids and other metabolites. By reducing the intestinal pH, the fermentation products of prebiotics create an unfavorable environment that inhibits the colonization of pathogens like Salmonella and enhances the gut epithelial integrity and nutrient absorption (Ayalew et al., 2022). Baurhoo et al. (2007) corroborated that supplementing prebiotics to poultry diets beneficially influences gut microbiota by boosting beneficial microbes and decreasing harmful bacteria. Additionally, this supplementation can improve intestinal structure and boost immune responses. These changes have collectively led to improvements in bird health and productivity, including enhanced growth rates, feed efficiency, and resistance to diseases (Ayalew et al., 2022). This makes prebiotics a potentially valuable natural substitute for antibiotic growth promoters in modern and commercial poultry farming (Yang et al., 2025).

Several authors have documented the use of prebiotics in mitigating HS adverse effects, with proven beneficial effects in broiler and laying hen production (Awad et al., 2020; Mangan and Siwek, 2024). Preserving the small intestine’s structural integrity is crucial to ensure optimal nutrient absorption, immune function, and overall growth. In broilers subjected to HS, incorporating 2% yeast and 0.15% prebiotics into their diet boosted BW and improved feed efficiency (Silva et al., 2010). Dietary supplementation of 0.5% mannan-oligosaccharide (MOS) and 1% Lactobacillus-based probiotic to heat-stressed broilers resulted in lower serum corticosterone and cholesterol concentrations, elevated thyroxine levels, and enhanced humoral immune function (Sohail et al., 2010). Additionally, this supplementation improves the broilers’ villus height, crypt depth, feed efficiency, and BW.

Administering 1g of MOS to laying hens under HS significantly improved various growth and production parameters, suggesting a protective role against heat-induced performance losses (Bozkurt et al., 2012). Notable enhancements were seen in WG, FCR, eggshell thickness and weight, as well as albumen height and weight in the treatment groups. Adding 24 mg/kg of MOS to heat-stressed broiler diets enhanced the intestinal morphology features, including increased villus surface area and width, as well as shorter crypt depth, leading to improved production in birds (Sohail et al., 2012). Another study indicated that supplementing heat-stressed (35 °C) broiler diets with 5% MOS and/or 1% probiotic mitigated HS’s harmful impacts on the intestinal morphology by enhancing the jejunum and ileum’s villus height and surface area (Awad et al., 2020). The dietary application of galacto-oligosaccharides exerts direct microbiota-independent effects, contributing to the stabilization of intestinal integrity. Specifically, galacto-oligosaccharides effectively prevent alterations associated with HS by maintaining the levels of jejunal E-cadherin, HSFs, HSPs, tight junction proteins, IL-6, IL-8, and TLR-4 (Varasteh et al., 2015).

4.2 Probiotics

Probiotics are live beneficial microbes that, when provided in sufficient quantities, improve the host’s health through modulation of the gut microbiota and immune system (Halder et al., 2024). Initially conceptualized in the early 20th century and later popularized as feed additives, probiotics have become prominent as safe, natural substitutes to antibiotics in poultry diets (Yang et al., 2025). These beneficial microbes, usually including lactic acid bacteria (Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium), specific yeasts (Saccharomyces), and other gut-associated bacteria, are added to poultry diets to enhance intestinal microbial balance and promote overall host health (Yang et al., 2025). Probiotic supplementation in poultry has been demonstrated to improve growth, feed efficiency, and meat and egg quality through improved nutrient utilization, protection of intestinal microflora, and stimulation of immune responses (Halder et al., 2024; Idowu et al., 2025). The beneficial actions of probiotics are mediated via multiple mechanisms, including competitive exclusion of pathogenic bacteria, synthesis of antimicrobial metabolites (e.g., organic acids and bacteriocins), strengthening of the gastrointestinal epithelial barrier, and regulation of immune function (Naeem and Bourassa, 2025). Through these actions, probiotics support gut health and disease resistance, emphasizing their importance as sustainable feed additives for enhancing poultry health and productivity (Naeem and Bourassa, 2025).

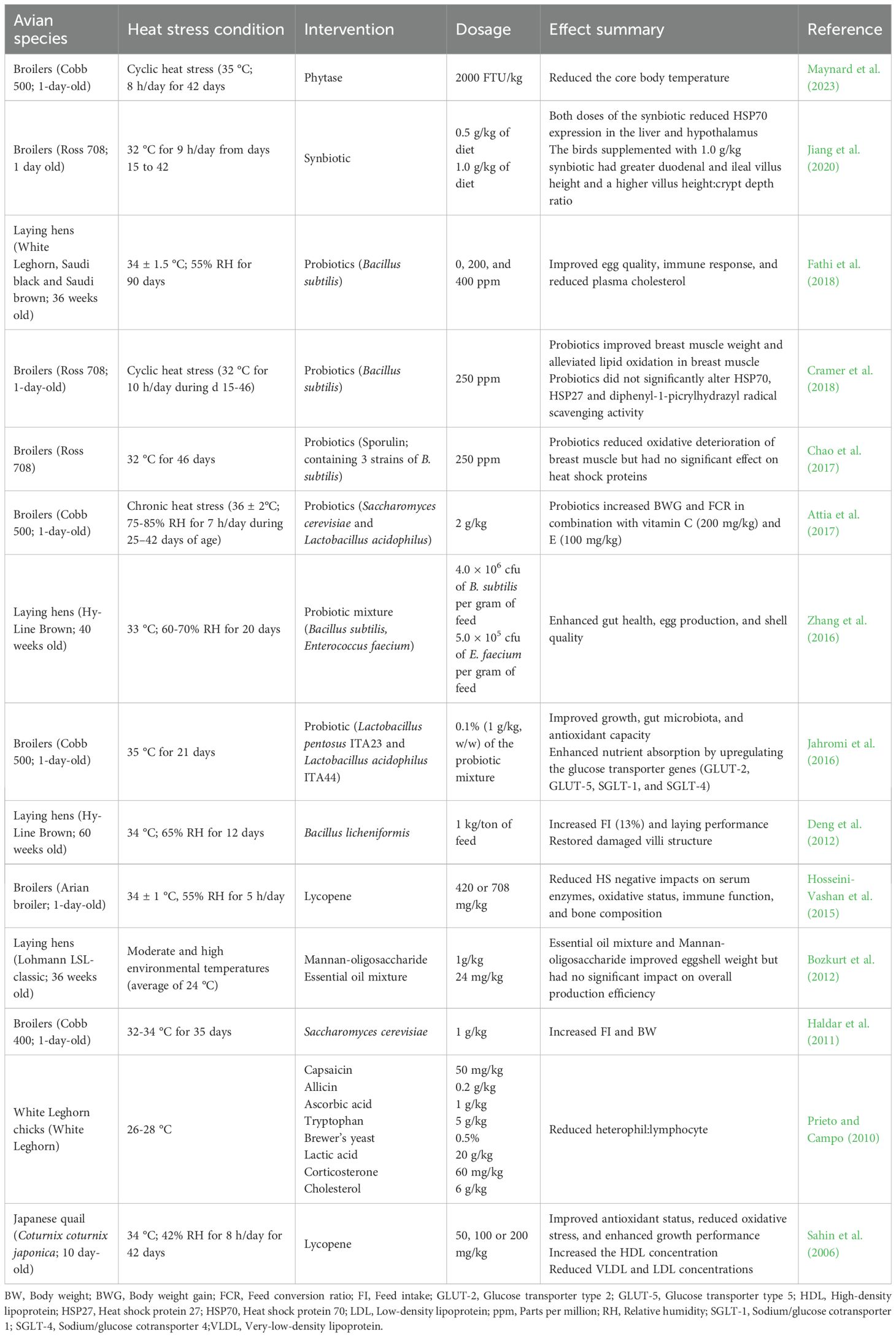

The role of probiotics in alleviating HS by enhancing gut health, boosting immune function, and improving overall physiological resilience of the avian species has been explored by several studies (Table 2). Under HS, several non-specific responses that negatively impact birds’ performance are triggered. The study on Bacillus subtilis supplementation in heat-stressed laying hens showed significant improvements only in eggshell weight, thickness, and strength (Fathi et al., 2018). Heat stress decreases BWG and increases the FCR, indicating less efficient feed utilization. However, supplementing fructose-added and rye-grass lactic acid bacteria in liquid forms reverses these effects (Aydin and Hatipoglu, 2024; Hatipoglu et al., 2024). This improvement occurs because probiotics enhance feed digestibility and digestive enzyme production, thereby increasing nutritional value and nutrient uptake under stress conditions. Additionally, probiotics can enhance nutrient absorption in heat-stressed birds by repairing damaged intestinal villi and crypts through the regulation of corticosterone and pro-inflammatory cytokines that trigger epithelial damage and permeability (Fatima et al., 2024).

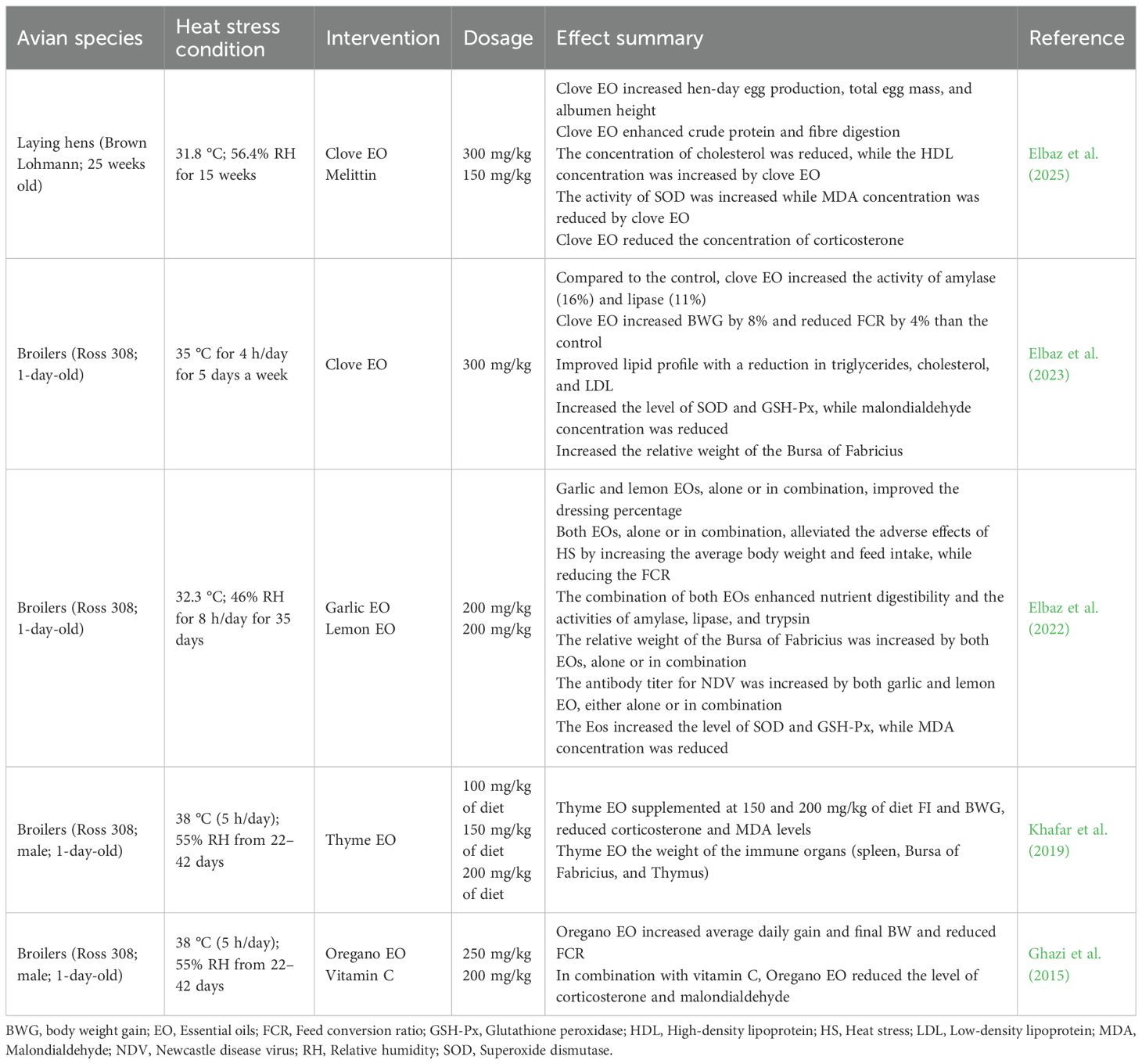

Table 2. Effects of phytochemicals, prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics, and enzymes on heat-stressed birds.

Epithelial cells act as the primary defense against pathogens and toxicity. Heat stress disrupts the gut microbiome, causing the erosion of beneficial gut bacteria and ultimately predisposing the host to greater disease vulnerability. Zhang et al. (2016) demonstrated that probiotic supplementation modulated the immune response of laying hens by downregulating IL-1 (pro-inflammatory cytokine) expression and upregulating IL-10 (anti-inflammatory cytokine) production. Heat stress inhibits epithelial cell growth by down-regulating Wnt/ß-catenin signaling, reducing stem cell proliferation and differentiation of stem cells in the intestinal crypts (Zhou et al., 2020). Probiotic mixture improves the intestinal barrier permeability by increasing the expression of claudin-5 in heat-stressed broilers (Hernandez-Coronado et al., 2025). This enhancement may effectively prevent endotoxin invasion and alleviate symptoms associated with HS. Heat stress induces the upregulation of hepatic HSP70 mRNA expression as a protective cellular response, but probiotic supplementation downregulates this expression (Aydin and Hatipoglu, 2024), potentially mitigating the stress-induced molecular response and supporting liver health.

The intestinal mucus layer is critical in protecting the epithelium and maintaining gut barrier function in poultry. Sandikci et al. (2004) noted a decline in goblet cells located in the ileal villi and responsible for producing mucus in heat-stressed quails. Also, Deng et al. (2012) reported that the cecum and ileum goblet cells population of heat-stressed hens was sustained with the supplementation of Bacillus licheniformis. Likewise, probiotics containing Lactobacillus enhanced the duodenum and jejunum goblet cells in broilers under HS (Ashraf et al., 2013). Smirnov et al. (2005) reported that probiotics enhance goblet cell numbers by upregulating mucin gene expression and promoting faster goblet cell differentiation. Peptides generated from Bacillus have antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral properties, and stimulate mucin secretion from goblet cells to perform protective functions (Fatima et al., 2024).

The thyroid hormones, triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4), are vital for synthesizing and activating various structural proteins, hormones, and enzymes. While high temperatures have differing effects on T4 levels, they consistently decrease blood T3 levels (Olayiwola and Adedokun, 2025). The supplementation of both liquid Fructose-added and Rye-Grass Lactic Acid Bacteria elevated serum T3, but not T4 concentrations in broilers under HS (Aydin and Hatipoglu, 2024). Thus, enhanced thyroid hormone levels due to probiotic supplementation are anticipated to boost digestion and metabolism in heat-stressed chickens (Aluwong et al., 2013). A potential factor contributing to the elevation of T3 and T4 hormone concentrations in heat-stressed broilers receiving probiotics may be the reduction of circulating corticosterone levels. High corticosterone levels have been associated with hypothyroidism, suggesting a possible mechanistic link between stress responses and thyroid function in the birds (Sohail et al., 2012).

Ahmad et al. (2022) highlighted that probiotics can counteract the harmful impacts of HS on poultry by improving gut health and modulating the immune system. The study suggested that probiotic supplementation enhances thermotolerance in poultry by stabilizing gut microbiota and promoting better nutrient absorption. Similarly, Chen et al. (2022) highlighted the role of probiotics in maintaining intestinal microbial balance, which is often disrupted under HS. Heat-stressed birds experience a shift in gut microbiota composition (dysbiosis), leading to poor digestion and nutrient uptake. Supplementing poultry diets with probiotics like Lactobacillus plantarum or prebiotics helps suppress pathogenic bacteria like Salmonella and E. coli by lowering gut pH and competing for nutrients and attachment sites, thereby improving gastrointestinal health (Humam et al., 2019). This helps beneficial bacteria to flourish, reducing the risk of intestinal dysbiosis and enhancing gut integrity (Chen et al., 2022).

4.3 Synbiotics

The efficacy of synbiotics, which are a synergistic combination of prebiotics and probiotics, in combating HS has been explored. Supplementing broilers with a synbiotic, a blend of prebiotics like fructo-oligosaccharides and a probiotic comprising Lactobacillus reuteri, Enterococcus faecium animalis, and Pediococcus acidilactici could help decrease the adverse effects of HS (Mohammed et al., 2019). Also, the research by Mohammed et al. (2022) proved the effectiveness of a dietary synbiotic supplement in broiler chickens under HS conditions (32 °C for 9 hours daily). The authors found that birds that received synbiotics exhibited behavioral and physiological improvements compared to the control and antibiotic-treated groups. The birds fed synbiotics showed more preening and feeding behaviors, and importantly, less panting and drinking, which are commonly observed in heat-stressed birds. Furthermore, these birds had significantly higher BW and BWG at both day 28 and 42. The positive effects on growth were associated with a substantial reduction in the pathogenic bacterium, E. coli, in the cecal microbiota, and this is comparable to that of the antibiotic-treated group (Mohammed et al., 2019, Mohammed et al., 2022).

Beyond behavioral and performance benefits, synbiotics have further been shown to enhance the intestinal health and integrity of birds subjected to HS. Mohammed et al. (2022) showed that synbiotic supplementation led to greater villus height and crypt depth in the jejunum than in the control and antibiotic-treated chickens. This improvement in intestinal architecture is critical as it increases the surface area for nutrient absorption, thereby enhancing digestion and assimilation. The protective effect of synbiotics on intestinal histomorphology was earlier reported by Jiang et al. (2020), with an increase in villus height in the duodenum and ileum of broilers fed a synbiotic. This suggests that the beneficial microbes and non-digestible carbohydrates in the synbiotic work together to protect the intestinal villi from toxins and pathogens, thus strengthening the gut barrier and reducing permeability.

The mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of synbiotics extend to regulating physiological stress indicators. Mohammed et al. (2019) found that synbiotics enhanced the antioxidant status of heat-stressed broilers by increasing plasma levels of GSH-Px and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf-2), which are important components of the antioxidant defense system. The synbiotic also reduced the heterophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, a widely used indicator of stress in poultry, demonstrating its capacity to modulate stress reactions. Additionally, Jiang et al. (2020) observed that synbiotic supplementation significantly lowered the expression of HSP70 in the liver and hypothalamus, indicating that the synbiotic may help the birds cope with the stress response more effectively. While some studies have reported inconsistent results, likely due to variations in synbiotic composition, dosage, and experimental conditions, the collective evidence from these studies suggests that dietary synbiotics can be a viable and effective strategy for improving poultry’s health, welfare, and productivity in hot climates.

4.4 Postbiotics

Salminen et al. (2021) defined postbiotics as “preparation of inanimate microorganisms and/or their components that confers a health benefit on the host.” Postbiotics are non-viable fragments of cells or microbes and may or may not encompass various metabolites (Saeed et al., 2023). Unlike live probiotics, postbiotics lack viable cells; instead, they consist of microbial cell components (such as inactivated cells, cell wall fragments, peptides, teichoic acids) and metabolites like organic acids, enzymes, and other bioactive compounds (Roque et al., 2025). Postbiotics have emerged in poultry nutrition as a next-generation feed additive that provides greater stability and safety than live microbes, because they remain stable during feed processing and storage and do not need refrigeration (Saeed et al., 2023). They exert their beneficial effects through various mechanisms, like directly inhibiting harmful microbes, strengthening the intestinal barrier, and modulating local and systemic immune responses (Zhong et al., 2022). Also, they exhibit immunomodulatory, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activities that help maintain gut homeostasis (Saeed et al., 2023). Consequently, postbiotics have gained attention as safe AGP alternatives in poultry feed, capable of supporting intestinal eubiosis and sustaining bird performance under challenging conditions (Roque et al., 2025).

Dietary postbiotic supplementation can improve broiler chickens’ growth rate and feed efficiency, while reducing enteric pathogen load (Waqas et al., 2024). Furthermore, postbiotics support beneficial gut microbiota and fermentative metabolites (e.g., lactic acid), improve intestinal villus structure and barrier integrity, and reduce intestinal pH and harmful bacteria. Improving nutrient digestion in the upper GIT of poultry reduces undigested feed in the hindgut, especially protein, which becomes substrate for cecal microbial fermentation. Excess protein in the hindgut produces metabolites like ammonia, biogenic amines, indoles, and phenols that harm gut health and growth (Qaisrani et al., 2015). Enhancing upstream digestion limits nutrients reaching the ceca, reducing hindgut fermentation and the formation of harmful compounds. Less escaped protein shifts cecal microbes from proteolytic to a more balanced, saccharolytic community. These effects enhance nutrient absorption, boost immunity, and promote overall health and poultry productivity (Saeed et al., 2023; Waqas et al., 2024).

According to Humam et al. (2019), postbiotics, including L. plantarum, have antioxidative effects in poultry subjected to HS. Additionally, postbiotics produced by L. plantarum helped maintain gut microbiota while also improving growth performance and intestinal structure (Humam et al., 2019). Moreover, it has been demonstrated that these metabolic products contribute to the enhancement of egg quality while simultaneously reducing cholesterol levels in both the plasma and egg yolk of laying hens (Loh et al., 2014). Supplementing prebiotics and postbiotics containing inulin to broilers’ diet improves the birds’ feed efficiency, BW, intestinal structure, and mRNA expression of growth hormone receptors (Kareem et al., 2016).

4.5 Phytogenic supplementation

Phytogenics or phytochemicals are plant-derived bioactive compounds that consist of secondary metabolites that are beneficial to animals, including nutritive and medicinal functions (Akbarian et al., 2016). They are present in dried plant materials, extracts, pure isolated compounds, and essential oils (EOs). The phytocompounds, including curcumin, epigallocatechin gallate, L-theanine, lycopene, and resveratrol, are known for their strong antioxidant properties. These bioactive compounds possess free radical scavenging properties, which mitigate ROS production, thereby enhancing the total antioxidant capacity. Furthermore, they contribute to improved FI, WG, and FCR (Wasti et al., 2020). Extensive research has highlighted the positive impact of phytochemicals, including eucalyptus oil (Petrolli et al., 2019), oregano (Alagawany et al., 2019), and menthol, in heat-stressed birds (Wasti et al., 2020).

4.5.1 Essential oils

Essential oils are complex, natural mixtures of volatile terpenoids and other aromatic compounds derived from plants. These substances are recognized for their antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties, which underpin their significance in livestock nutrition. Several studies have been conducted to determine the impacts of EO in alleviating HS effects in poultry (Table 3).

Heat stress adversely impacts growth by increasing FCR and mortality while decreasing BWG and FI. Many studies have demonstrated that supplementing EOs in poultry diets can counteract these effects. Studies have revealed that EOs improve BWG and reduce FCR in heat-stressed broilers (Ghazi et al., 2015; Khafar et al., 2019) and quails (Tekce et al., 2020). Tekce et al. (2020) observed that including 200 ppm of Moringa oleifera EO into the diet of heat-stressed Japanese quails improved BW, BWG, and FI, and decreased FCR. Also, Madkour et al. (2024) reported that compared with the unsupplemented heat-stressed broilers, offering 50 mg/kg of oregano extract significantly increased the BW and BWG and decreased the FCR by 10.20%, 9.92%, and 5.84%, respectively. In a 42-day study trial, Lippia origanoides EO and herbal betaine significantly improved BW and BWG of heat-stressed broilers (Senas-Cuesta et al., 2023). Supplementing oregano EO, alone or in combination with vitamin C, increased the average daily gain and final BW and decreased the FCR of broiler chickens (Ghazi et al., 2015). Khafar et al. (2019) demonstrated that supplementing thyme EO at 150 and 200 mg/kg mitigated the adverse effects of HS on FI, BWG, and FCR. The positive effects of EOs are attributed to their ability to stimulate the secretion of digestive enzymes, which enhances nutrient digestion and absorption (Elbaz et al., 2022, Elbaz et al., 2023).

Heat stress damages the intestinal mucosa, causing increased permeability and a subsequent shift in the gut microbial community. Essential oils possess strong antimicrobial properties that help to restore the gut microbiota homeostasis by suppressing pathogenic bacteria like Escherichia coli, while promoting the proliferation of beneficial species, like Lactobacillus (Khafar et al., 2019; Elbaz et al., 2023). The phenolic compounds within EOs modify the intestinal environment, creating unfavorable conditions for pathogens and strengthening the gut barrier. In addition to their antimicrobial activity, EOs also improve the physical structure of the intestine. Senas-Cuesta et al. (2023) reported that Lippia origanoides EO improved intestinal morphology of heat-stressed broilers by increasing the villus height and the villus height-to-crypt depth ratio in the duodenum and ileum. This improved morphology enhances the gut’s absorptive surface area, facilitating better nutrient utilization and improving performance. Essential oils positively impact intestinal integrity by upregulating the expression of mucin 2 (MUC-2) gene, which is critical for maintaining the mucosal barrier (Elbaz et al., 2025).

Heat stress induces oxidative stress by disrupting the balance between free radical production and the body’s antioxidant defense system. Essential oils, particularly those rich in phenolic compounds like carvacrol and thymol, are potent antioxidants. Research has shown that EO supplementation increases antioxidant enzyme activities, including SOD and GSH-Px, while significantly decreasing malondialdehyde (MDA; a marker of lipid peroxidation) levels (Elbaz et al., 2022, Elbaz et al., 2023). Furthermore, EOs have been found to modulate hormonal responses to stress. Several studies have reported decreased serum corticosterone and increased T3 levels in heat-stressed broilers (Khafar et al., 2019) and laying hens (Elbaz et al., 2025) fed EOs, indicating improved stress adaptation. The hypocholesterolemic effects of EOs, such as those derived from clove and thyme, have also been documented, with reductions in serum cholesterol and triglycerides (Khafar et al., 2019; Elbaz et al., 2023).

The immunosuppressive effects of HS are a major concern in poultry farming, but EOs have been shown to positively impact the immune system of heat-stressed birds, with an increase in the relative weight of immune organs. Clove EO increased the weight of the Bursa of Fabricius in heat-stressed broilers (Elbaz et al., 2023). Likewise, the weight of immune organs, including the Bursa of Fabricius, spleen, and thymus, was increased when thyme EO was supplemented in broiler chicken diets (Khafar et al., 2019). Also, thyme EO decreased the heterophil/lymphocyte ratio in the heat-stressed broilers (Khafar et al., 2019). In heat-stressed broilers, the humoral immune response was enhanced by thyme (Khafar et al., 2019) and clove (Elbaz et al., 2023) EO, as evidenced by increased Immunoglobulins G and M and antibody titers against Newcastle disease virus. This immunomodulatory effect is attributed to the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of EOs, which protect immune cells from damage and support their function.

4.5.2 Resveratrol

The natural bioactive polyphenol, resveratrol, is obtained from red grapes, peanuts, berries, and turmeric (Sridhar et al., 2015). Supplementing resveratrol in poultry diets is effective in mitigating HS negative impacts by promoting the recovery of intestinal barrier integrity, normalizing gut morphology and goblet cell populations, and regulating tight junction-associated gene expression in chickens (Liu et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2017). The proper expression of HSPs is essential for protecting against HS, where they act as cellular stress signal sensors and contribute to activating the innate and adaptive immune responses (Hickman-Miller and Hildebrand, 2004). Resveratrol acts in poultry physiology by enhancing the expression of antioxidant and HSP mRNA, stimulating fatty acid oxidation, and regulating the immune response. These mechanisms enhance resveratrol’s ability to reduce poultry HS and sustain physiological balance (Hu et al., 2019).

Supplementing resveratrol at 0, 200, 400, and 600 mg/kg diet enhanced productivity and humoral immunity while also decreasing serum MDA levels and HSP gene expression (Liu et al., 2014b). Hu et al. (2019) revealed that supplementing broiler feed with 400 mg resveratrol/kg of diet enhanced antioxidant capacity under HS conditions. Also, supplementing 300 or 500 mg/kg of resveratrol in the diet of heat-stressed yellow-feather broilers improved average daily gain, reduced rectal temperatures, and decreased circulating adrenocorticotropin hormone, MDA, corticosterone, and cholesterol concentrations (He et al., 2019b). Likewise, in the same study, dietary resveratrol enhanced the activities of SOD and GSH-Px.

According to Zhang et al. (2017), dietary supplementation with 400 mg/kg of resveratrol alleviated the increase in intestinal permeability and restored gut integrity compromised by HS in broilers. It has been shown that resveratrol modulates the gut microbiota by lowering the abundance of harmful bacteria like E. coli while promoting beneficial genera, including Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium. Additionally, resveratrol can increase the upregulation of the jejunal tight junction and adhesion junction genes, including occludin, claudin-1, mucin-2, and E-cadherin in the jejunum. Ducks exposed to acute HS had an improved villus:crypt depth, increased goblet cells and tight junction proteins, and decreased the expression of HSP (Yang et al., 2021a). Dietary supplementation of laying hens’ diet with resveratrol at 200 mg/kg enhanced laying performance, while supplementing their diets with 400 mg/kg lowered blood cholesterol and triglycerides, decreased egg cholesterol, enhanced antioxidant activities, and egg sensory scores (Zhang et al., 2017).

4.5.3 Lycopene

Lycopene is a carotenoid (an acyclic β-carotene isomer) present in tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum) and fruits and vegetables like watermelon, pink guava, and carrot. In poultry, lycopene has been shown to support physiological function, particularly by alleviating oxidative stress caused by heat exposure. In birds, lycopene supports oxidative balance by scavenging free radicals, inhibiting signaling pathways, and activating antioxidant enzymes like CAT, GSH-Px, and SOD (Arain et al., 2019). Its antioxidant action involves suppressing singlet oxygen and eliminating ROS, thereby preventing oxidative damage to cells (Sahin et al., 2023).

In heat-stressed birds, lycopene can boost the expression of antioxidant enzymes by stimulating the DNA’s antioxidant response element (Nrf2) pathway (Arain et al., 2019; Wasti et al., 2020). According to Sahin et al. (2016), supplementing lycopene at 200-400 mg/kg diet influences transcriptional factors (Keap1-Nrf2-ARE) and mitigates the adverse effects of cyclic HS (34 °C) in broilers. The anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory activities of lycopene improve broiler productivity, meat quality, feed efficiency, and laying hens’ egg quality (Arain et al., 2019). Similarly, a diet containing 20 mg/kg of lycopene resulted in reduced lipid peroxidation and enhanced egg yolk color, as well as increased levels of minerals and vitamins in laying hens (An et al., 2019). The addition of lycopene (200 or 400 mg/kg) enhanced the total FI, WG, and FCR in heat-stressed broilers (Sahin et al., 2016). Lycopene in laying hens’ diets enhanced vitamin levels, boosted oxidative stability, and enriched the yolk color of (Sahin et al., 2016; Arain et al., 2019). Moreover, lycopene is known to reduce lymphocyte proliferation while enhancing antioxidant levels, immunity, and lipid metabolism in broiler chickens, which contributes to better growth performance (Sahin et al., 2016; Arain et al., 2019).

4.5.4 Curcumin

Curcumin, the main polyphenol from turmeric, has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory benefits (Wasti et al., 2020). Recently, curcumin has emerged as a promising phytochemical for alleviating HS in poultry, aided by its efficient absorption in the avian digestive system (Wasti et al., 2020). Literature has established the growth-supporting benefits of curcumin in heat-stressed broilers and laying hens (Zhang et al., 2015, Zhang et al., 2018). Under HS conditions, broilers fed 100 mg curcumin/kg of diet showed improved final BW (Zhang et al., 2015, Zhang et al., 2018). Also, curcumin fortification lowered mitochondrial MDA accumulation and suppressed ROS generation by boosting Glutathione S-transferase, GSH-Px, and Mn-SOD activities (Zhang et al., 2015). By upregulating thioredoxin-2 and peroxiredoxin-3, curcumin fortification strengthens cellular antioxidant defenses in broilers experiencing HS (Zhang et al., 2018). Adding 150 mg/kg of curcumin in laying hen diets during HS enhanced laying performance, improved egg quality, elevated antioxidant enzyme activities, and supported immune function (Liu et al., 2020a, Liu et al., 2020b).

Curcumin can help alleviate HS in poultry by lowering oxidative stress and inflammation (Hu et al., 2019). According to Nawab et al. (2019), curcumin enhanced the immunity status of laying hens under HS by reducing the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α. Attia et al. (2017) and Zhang et al. (2018) reported that supplementing curcumin in heat-stressed broiler diets improves growth performance. Supplementing graded curcumin nanoparticles (25, 50, and 100 mg/kg) into broiler diets increased BW, FI, and immune organ weight reduction in malondialdehyde (Badran, 2020). In the same study, the enzymatic activities of GSH-Px and SOD were increased.

4.5.5 Epigallocatechin gallate

Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) is a polyphenolic compound obtained from green tea, and it is recognized for its strong anti-inflammatory and antioxidant characteristics (Hu et al., 2019; Wasti et al., 2020). Supplementing 300 and 600 mg of EGCG/kg diets led to greater BW, increased FI, and higher levels of alkaline phosphatase, glucose, and serum total protein (Luo et al., 2018). Xue et al. (2017) showed that EGCG supplementation enhanced BW and increased antioxidant enzyme activities of CAT, GSH-Px, and SOD in the liver and serum of heat-stressed broiler chicks. In female quails subjected to HS, supplementing 200 or 400 mg of EGCG/kg of feed led to greater FI, increased laying performance, enhanced hepatic CAT, GSH-Px, and SOD activity, and a linear reduction in hepatic MDA levels (Sahin et al., 2010).

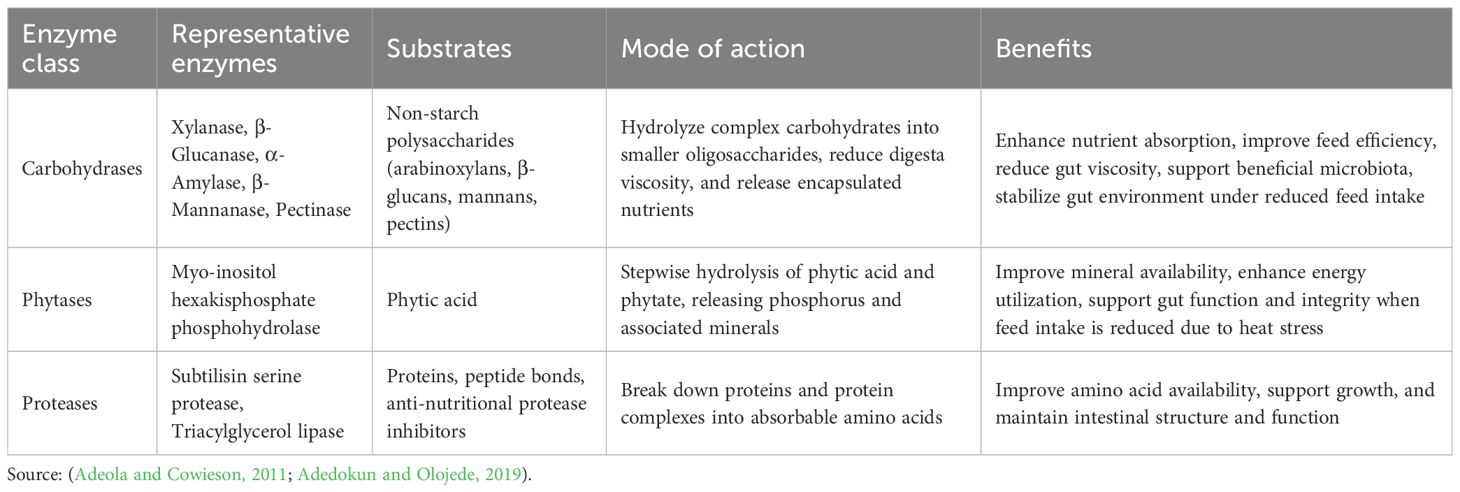

4.6 Exogenous enzymes

Exogenous enzymes are biologically active proteins that are included in poultry diets to enhance digestion. They target nutrients entrapped in substrates, which are difficult to digest or unavailable because of anti-nutritional factors in the feedstuffs. These enzymes enhance nutrient utilization, improve feed efficiency, and support intestinal health, particularly under physiological or environmental stress conditions. In poultry, carbohydrases, phytases, and proteases are commonly used as exogenous enzymes, each with specific target substrates and modes of action (Table 4).

Table 4. Exogenous enzyme classes, their substrates, and potential benefits in mitigating heat stress in poultry.

Currently, there is a dearth of information regarding the role of dietary exogenous enzymes in mitigating the harmful impacts of HS on poultry performance. Also, this section covers only phytase supplementation in heat-stressed birds due to the non-significant effects of supplementing other exogenous enzymes, like carbohydrases, in heat-stressed birds, as at the time of writing this review. However, recent research in both broilers and laying birds has highlighted the benefits of phytase supplementation during HS. Phytase has demonstrated greater promise in countering HS effects, especially regarding mineral utilization. Mohebbifar et al. (2015) reported that including phytase (150 FTU/kg) in heat-stressed (36 °C) laying hens’ diets improved feed efficiency, egg production, eggshell weight, and reduced heterophil:lymphocyte. Similarly, Tizziani et al. (2016) reported that broilers fed phytase (500 FTU/kg) with reduced available phosphorus maintained performance, carcass yield, and bone mineralization under HS (32 °C). In broilers, Maynard et al. (2023) reported that supplementing a high-dose commercial phytase (Quantum Blue, 2000 FTU/kg) improved growth during cyclic HS (35 °C for 8 h/day). Adding phytase to heat-stressed broiler diets reduced the birds’ core body temperature during day 29–38 and partially mitigated HS-induced reductions in FI and BW (Maynard et al., 2023).

Moreover, Ribeiro et al. (2024) described phytase as an effective strategy to counteract both heat-induced physiological disturbances and the antinutritional impact of phytate in laying Japanese quails. Supplementing high-dose phytase (≥1500 FTU/kg) improved calcium and phosphorus absorption, enhanced eggshell thickness, and increased egg production under HS conditions (up to 36 °C). This potential benefit of phytase supplementation was associated with increased intestinal expression of the calcium-binding protein, calbindin-D28k, which facilitates calcium mobilization toward eggshell formation. Additionally, phytase improved bone mineralization, reduced the damaging effects of respiratory alkalosis on calcium availability, and supported the overall welfare in heat-stressed quails. Recently, Ribeiro et al. (2025) demonstrated that super-dosing phytase (1500 FTU/kg) enhanced eggshell thickness and upregulated renal and uterine calcium transporters (Calbindin-D28k) in quails under HS (36 °C). This indicates that higher than standard phytase supplementation levels may modulate gene expression to sustain calcium metabolism and reproductive performance under HS. These results highlight phytase’s role in overcoming heat- and diet-induced mineral deficiencies.

5 Conclusion and future directions

The intensifying challenge of HS in poultry production demands integrated, science-driven solutions to safeguard birds’ health, productivity, and welfare. Heat stress disrupts birds’ physiological activities, including immune response and antioxidant capacity. Dietary feed additives have demonstrated considerable potential in mitigating the adverse effects of HS by targeting multiple physiological pathways. These additives modulate the HPA axis to reduce HS-induced hormonal imbalances, improve antioxidant defense systems by enhancing the activity of enzymes, and support intestinal barrier integrity through the upregulation of tight junction proteins. They also influence gut microbiota composition to reduce endotoxin leakage, improve nutrient absorption by stabilizing digestive enzyme activity, and modulate inflammatory pathways by downregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines. Prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics, and postbiotics reinforce gut integrity, modulate immune function, influence microbial population, and improve nutrient absorption, thereby enhancing growth and productivity. Phytochemicals like EOs contribute antioxidant and anti-inflammatory benefits, while resveratrol, lycopene, curcumin, and epigallocatechin gallate provide additional protective effects at the cellular and systemic levels. Recent evidence also highlights the role of exogenous enzymes, specifically phytase, in improving mineral metabolism and production efficiency under heat-stressed conditions. The multifaceted actions of these additives underscore their value as a non-antibiotic, sustainable strategy to enhance poultry thermotolerance. Nevertheless, variability in responses highlights the need for future research to focus on mechanistic pathways, optimal dosing, and synergistic additive combinations tailored to species, age, and production systems to maximize thermotolerance and production efficiency. Furthermore, comparative economic analyses and field-based trials addressing the practical implications of utilizing these additives in heat-stressed poultry are warranted. Strategic incorporation of these nutritional interventions, alongside genetic, managerial, and environmental approaches, will be critical to maintaining a resilient and economically viable poultry industry in the face of ongoing climate change.

Author contributions

SO: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. SA: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.