Abstract

The concept of “Ecohesion” offers a novel perspective on sustainable transitions by emphasizing social cohesion as a central element. Drawing inspiration from Herbert Gintis's combination of macro social dynamics and micro behavioral evidence, this framework integrates his theories on the interplay between social norms, endogenous preferences, and institutional dynamics. By identifying four fundamental social conditions—access to basic goods and services, decent jobs, time affluence, and social capital—Ecohesion provides an analytical lens to assess the sustainability and political feasibility of transition policies.

1 Introduction

Achieving high levels of well-being for all within planetary boundaries is one of the central challenges of the 21st century. While technological innovation and decarbonization strategies are advancing rapidly, their successful implementation critically depends on the social fabric within which they are embedded. Recent transformations—environmental degradation, climate change, automation, and digitalization—have intensified existing inequalities and contributed to the erosion of social cohesion across world societies. This loss of social cohesion undermines the political feasibility and societal support for transition policies.

These concerns echo a growing body of research arguing that transition strategies must be embedded in a framework that respects both ecological ceilings and social foundations (Raworth, 2017), and that climate progress and social justice must go hand in hand (McCauley and Heffron, 2018). These frameworks are further reinforced by empirical work showing that countries can meet basic human needs at lower levels of resource use if supported by adequate public provisioning and social cohesion (O'Neill et al., 2018), and that equitable labor sharing and universal services are prerequisites for the feasibility of a post-growth future in Europe (D'Alessandro et al., 2020).

What is missing in the literature, however, is a dynamic integration of the role of social cohesion into empirical modeling frameworks of the ecological transition. Integrated assessment models (IAMs) which are designed to study potential socio-technical pathways for the mitigation of climate change typically limit their representation of the impact of transition on society to its effect on the labor market, excluding wider-reaching impacts (Van Eynde et al., 2024). Emerging IAMs, particularly in the field of ecological macroeconomics, increasingly give a central role to broader indicators of well-being which measure the impact of the transition on aspects such as health, education, or democracy (Oakes et al., 2020; Stoknes et al., 2025; Vogel et al., 2025). These models have not, however, included a feedback backwards from well-being indicators to the progress of ecological transition itself.

This paper takes initial steps in filling this gap by presenting a conceptual framework—Ecohesion—designed to operationalize the two-way relationship between the ecological transition and social cohesion. In this framework, social cohesion is not just a desirable outcome, or co-benefit, of a transition, but is a necessary component in allowing the policy conditions which facilitate transition. With a mind to applications in empirical modeling, the Ecohesion framework identifies four critical, and quantifiable, social conditions—basic goods and services, decent jobs, time affluence, and social capital—as transmission mechanisms between public policy and sustainable well-being.

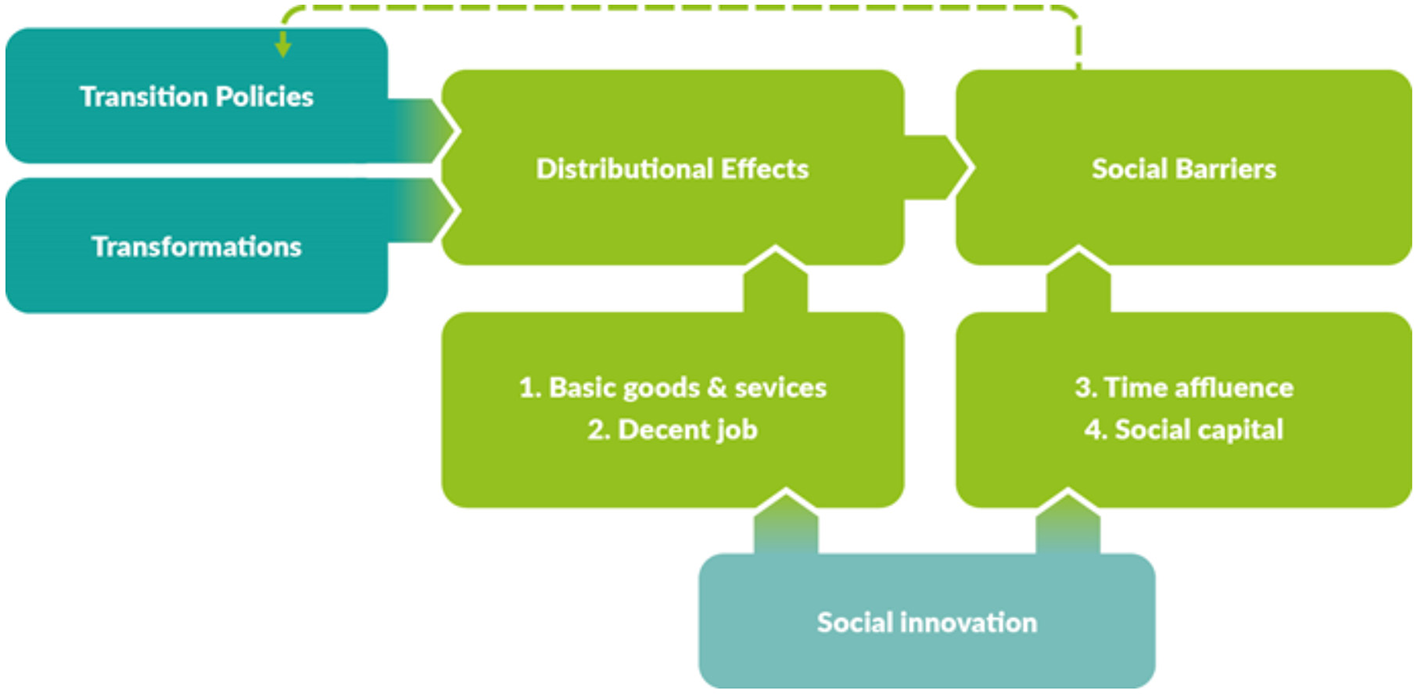

The central notion of Ecohesion, illustrated in Figure 1, is that understanding how these key social conditions co-evolve with economic, technological, and environmental systems is essential for identifying sustainable and politically feasible policies that can prevent the emergence of social barriers to the transition.

Figure 1

The ecohesion concept.

Easing the twin challenges of sustainability and social justice requires breaking out of disciplinary silos. Ecological economics, social psychology, political philosophy, and behavioral science must converge to explain how human behavior, institutional structures, and biophysical limits co-evolve. In this spirit, Herbert Gintis's work is a touchstone. His call for a unified behavioral science (Gintis, 2009) and his joint theorization of cooperation with Samuel Bowles (Bowles and Gintis, 2011) undermine the narrow view of agents as isolated utility maximizers and instead situate choice within norms, identities, and institutions. Ecohesion inherits this lens: it treats ecological sustainability and social cohesion as mutually reinforcing, arguing that policies succeed when they align with the normative, institutional, and relational underpinnings of social life.

Building on Gintis's behavioral foundations, Ecohesion underscores how prosocial motivations and institutional design co-evolve. The theory of strong reciprocity shows that people not only cooperate but apply social norms at personal cost, a mechanism central to the construction of trust and social capital, and to any collective action endeavor (Gintis, 2000). Likewise, the co-evolutionary dynamics between norms and institutions (Bowles and Gintis, 2013) imply that the legitimacy and uptake of transition policies hinge on perceived fairness and procedural justice.

Methodologically, Ecohesion aligns with the agent-based and complexity turn that Gintis helped to integrate into mainstream in economics—capturing emergent social structures among heterogeneous agents (Gintis, 2007)—and with his notion of modular rationality, which emphasizes that decision-making is context-dependent and shifts across moral, strategic, and affective “modules” (Gintis, 2016). These insights directly motivate our framework's four social conditions as transmission mechanisms through which policy interacts with behavior and institutions. Ecohesion is thus both a tribute to and an extension of Gintis's interdisciplinary project: it integrates behavioral realism, institutional co-evolution, and complexity methods to design transition pathways that are socially cohesive and ecologically viable.

2 Foundations: just transition, integrated modeling and behavioral sciences

There is a wealth of literature considering the socio-economic dimension of the ecological transition. Much of this is centered around the concept of a just transition (McCauley and Heffron, 2018; Galanis et al., 2025), which encompasses a wide range of separate conceptual themes (Wang and Lo, 2021) and topical focuses (Heffron, 2021). The idea that ecological transitions should be socially just has been cited in international publications as early as 2010 (UNFCCC, 2010; cited in Galanis et al., 2025) and is now frequently incorporated in national and international reports related to climate, nature, and energy. Within the just transition literature, there is a focus on the necessity to employ a “whole-systems approach” to understand the dynamic interplay between social and ecological system change (Abram et al., 2022), including the specific political economy considerations and tradeoffs inherent in the transition (Newell and Mulvaney, 2013).

Just Transition approaches are closely related to the Sustainability Transitions literature (Markard et al., 2012) which analyzes the role of innovation in “socio-technical transformations” (Markard and Truffer, 2008). This includes a focus on the importance of a “multi-level perspective” which integrates politics, culture, behavior, and policy (Geels, 2019) and can be applied to sustainability transitions across a broad range of actors (businesses, consumers, civil society, social and political movements) and applied to a large number of topics such as geography, ethics, governance, and behavioral change (Köhler et al., 2019). While the multi-level perspective is conceptually compatible with a systemic critique of the global capitalist economic system, this line of research has so far been underdeveloped within the sustainability transitions literature (Feola, 2020).

Instead, the analysis of the role of capitalism in an ecological transition has been a central concern of the de-growth and post-growth research communities (Cahen-Fourot, 2020; Jordán, 2025). This literature has pointed to inescapable tradeoffs between economic growth and environmental protection (Hickel and Kallis, 2020) and investigates policies (Fitzpatrick et al., 2022) and systemic changes (Hofferberth, 2025) which can allow for human well-being and ecological preservation (Kallis et al., 2025). A particularly active strain of post-growth research investigates the material (O'Neill et al., 2018; Vélez-Henao and Pauliuk, 2023), energy (Arto et al., 2016; Brand-Correa and Steinberger, 2017; Vogel et al., 2021), and labor (McElroy and O'Neill, 2025) requirements of a good life. This approach is closely related to the Doughnut Economics analytical framework of social and planetary boundaries (Raworth, 2017) which has been increasingly quantified (Fanning et al., 2022; Gucciardi and Luzzati, 2024; Fanning and Raworth, 2025). Post-growth approaches have also increasingly been applied to macroeconomic modeling, creating a sub-field of ecological macroeconomics (Rezai and Stagl, 2016; Hardt and O'Neill, 2017; Svartzman et al., 2019), which is particularly well suited to analyze demand-side economic and environmental policies (Creutzig et al., 2018, 2022).

An acknowledged limit of these literatures is their reliance on Global North knowledge systems (Ghosh et al., 2021) which can be improved with further conversation with the Global South (Escobar, 2015).

2.1 Integrated modeling and social cohesion

One key methodology used to study the forward development of economic and environmental systems is integrated assessment modeling. Integrated assessment models (IAMs) are large-scale computer models which integrate economic, technological, and environmental aspects. Also referred to as “climate-economy”, or “energy-environment-economy” models, these frameworks have traditionally focused primarily on the problem of climate change, although they are now being expanded to include representations of biodiversity and nature (Salin et al., 2024; Kedward and Gonon, 2025).

IAMs are generally used to conduct scenario analysis, in which the same underlying model is used to represent a number of different storylines, or scenarios. Comparing differences between scenarios generated in the same model can allow researchers to isolate important variables to better understand how they impact the transition. Comparison of similar scenarios created in different models can then identify the importance of specific modeling decisions and point to robust aspects of the transition which are common across models.

For this approach to be effective, it is important for there to be both a wide range of scenarios represented (McCollum et al., 2020), and a meaningful diversity among the underlying models (Proctor, 2023), such that their results can be robust to specific modeling choices and sufficiently cover the large range of questions which will be relevant for the ecological transition. Of particular importance to this diversity are the underlying modeling frameworks—such as computable general equilibrium (CGE), partial-equilibrium, macroeconometric, system dynamics, agent-based and stock-flow consistent—which are represented in the literature, as each brings different strengths and limitations (Nikas et al., 2019; Hafner et al., 2020; IPCC, 2022).

Until now, connections between just transition and integrated modeling have been made primarily at the level of scenario analysis through the inclusion of a range of socio-economic model outputs which speak to the desirability of a scenario. What is lacking is an integration of social considerations into the dynamic structure of the models themselves (Trutnevyte, 2019; Mathias, 2020). Ecohesion looks to fill this gap by identifying quantifiable variables which can allow for building hard model features to capture complex dynamics and feedbacks around social cohesion. To do so, the approach draws heavily from the fields of behavioral and experimental economics in order to operationalize the dynamic complexity surrounding behavioral change and the development of social cohesion.

2.2 Behavioral sciences and experimental economics

Behavioral and experimental economics provide crucial micro-foundations for the Ecohesion approach by revealing how cooperation, trust, and adaptation emerge from interactions among boundedly rational agents embedded in social contexts. From this perspective, ecological transitions can be viewed as both bottom-up and top-down processes: they depend, on the one hand, on the collective capacity of individuals and communities to coordinate costly actions for shared benefits, and, on the other, on the institutional and structural conditions that shape—or constrain—the behavioral responses to policy interventions. Research in the behavioral sciences offers conceptual and empirical tools to link these two dimensions, explaining how preferences, norms, and expectations co-evolve with institutional arrangements and how social cohesion conditions the feasibility of ecological transformation.

The first behavioral dimension concerns collective action and cooperation. Since the early studies on fairness and reciprocity (Fehr and Schmidt, 1999; Camerer, 2003), experimental economics has shown that ecological and social dilemmas often take the form of public-goods or common-pool games in which individually costly actions must be coordinated to secure diffuse, intertemporal benefits under uncertainty (Ostrom, 2010; Tavoni et al., 2011; Bucciol et al., 2023). Public-goods experiments consistently reveal mechanisms of conditional cooperation and norm enforcement that sustain collective efforts: most individuals contribute in proportion to others' actions and are willing to sanction free riders at personal cost (Fehr and Gächter, 2002; Fischbacher et al., 2001; Fehr et al., 2002). These dynamics highlight the central role of fairness and perceived procedural justice in maintaining cooperation. Cross-cultural research further shows that the strength of cooperative norms and the prevalence of antisocial punishment vary systematically with institutional trust and inequality (Herrmann et al., 2008; Knack and Keefer, 1997), reinforcing the idea that relational infrastructures—shared norms, reputational networks, and expectations of reciprocity—provide legitimacy and stability for collective transitions. Climate-specific “collective-risk” experiments confirm that groups succeed more often when communication and coordination channels are open, whereas inequality in endowments or burdens undermines success unless compensatory mechanisms emerge early (Milinski et al., 2008; Tavoni et al., 2011).

The second behavioral dimension concerns behavioral adaptation and preference change. Behavioral economics and social psychology show that preferences and expectations are endogenous to institutions and evolve with policy design and social meanings (Bowles, 1998; Bowles and Polania-Reyes, 2012; Young, 2015; Bicchieri, 2017). Framing transitions through this lens foregrounds societies' adaptive capacity: informational, normative, and distributive environments jointly determine whether individuals adjust smoothly or resist top-down demands for change. Evidence from household energy and consumption behavior points to short-run “action-and-backsliding” cycles followed by slower cumulative learning (Allcott and Rogers, 2014). Meta-analyses of choice-architecture interventions confirm that the stability and magnitude of behavioral effects depend heavily on context and design (Mertens et al., 2022; Hummel and Maedche, 2019). Research on habits complements this view by showing that routine formation is a key channel through which pro-environmental behavior becomes self-sustaining (Mazar et al., 2021). The motivation-crowding literature further clarifies when extrinsic incentives substitute for or erode intrinsic motives: poorly framed fines or subsidies can transform moral norms into prices, dampening cooperation (Gneezy and Rustichini, 2000; Bowles and Polania-Reyes, 2012). Effective transition policies must therefore align material incentives with social meanings and identity structures so that compliance evolves into cooperation rather than constraint.

Beyond coordination and adaptation, inequality itself constitutes a structural barrier to both collective action and proactive behavioral change. Laboratory and network studies demonstrate that disparities in endowments or status erode trust, reduce willingness to cooperate, and amplify conflict over distributional outcomes (Nishi et al., 2015; Herrmann et al., 2008; Tavoni et al., 2011). Moreover, inequality interacts with social-norm dynamics: when individuals perceive institutions as unfair or outcomes as biased, willingness to adopt behavioral changes or support top-down policies declines (Prentice and Paluck, 2020; Zorell, 2020). Addressing distributive asymmetries through transparent governance, equitable participation, and recognition of diverse capabilities is therefore essential for enabling societies to engage collectively and adaptively with ecological transformation (Steg and Vlek, 2009).

In sum, the behavioral sciences reveal that social cohesion is not an exogenous condition but a dynamic capability emerging from cooperation, fairness, and adaptive learning (Fehr and Schmidt, 1999; Bicchieri, 2017). Embedding these mechanisms into transition modeling allows Ecohesion to capture how trust and perceived justice modulate policy effectiveness and societal resilience.

3 Conceptualizing ecohesion

3.1 Transformations and social barriers to transition

Mainstream models of transition often downplay or externalize the role of social dynamics, assuming institutional stability, political feasibility, and behavioral alignment as given. However, historical and empirical evidence suggests otherwise. Distributional conflicts, trust erosion, and political backlash can undermine even the most technically sound policies. As noted in recent studies on social tipping dynamics (Otto et al., 2020), public acceptance and norm shifts are often the key levers for accelerating or impeding low-carbon transitions.

The Ecohesion framework is designed to address these blind spots. It builds on the recognition that ecological and social systems are co-evolving and interdependent. It emphasizes “feedback coherence” between policies, institutions, and collective behavior—acknowledging that policy effectiveness is shaped by how individuals and communities perceive, internalize, and respond to interventions. Transitions in energy, transport, housing, or food systems depend not just on infrastructure and innovation, but on shared norms, mutual trust, and perceived fairness. In this context, social cohesion becomes not only a moral imperative but a strategic condition which facilitates transition.

At the center of our understanding of Ecohesion is the idea of a self-reinforcing feedback loop between the transition policies which are needed to ensure an ecological transition and the social and behavioral barriers which determine the political feasibility of implementing further transition policies. This feedback, depicted in the stylized causal loop diagram in Figure 2, runs through the mechanism of distributional effects, with deteriorations of economic conditions leading to an increase in social barriers. While it is possible for transition policies to have positive impacts on distribution, and thus negative effects on social barriers, the case we are more concerned with is that of transition policies with negative distributional effects.

Figure 2

Methodological overview.

This simple loop is further complicated by the presence of global transformations which themselves have an impact on distributional effects. As referenced in Figure 1, here we are considering primarily environmental transformations, like the climate crisis and deterioration of biodiversity, technological transformations like, digitalization and the energy transition, and social and economic transformations like liberalization or demographic shifts. The inclusion of these transformations in our framework is to stress that distributional effects are not determined only, or even mainly, by transition policy.

Finally, in the most distinctive feature of Ecohesion, the emergence of social barriers to transition does not follow directly from changes in distributional effects, but is rather regulated by the levels of social cohesion in a society. In a general sense, we argue that societies with high levels of social cohesion can more readily withstand distributional shocks before erecting social barriers than societies with low levels of social cohesion. This means that the relationship between transition policies and social barriers is not universal and can instead vary across time and place. The specific Social Conditions for Ecohesion included in our framework, as well as the social innovations which can impact them, are discussed in the following sections.

The framework also draws inspiration from evolutionary and institutional economics, and particularly from Herbert Gintis's work on the co-evolution of preferences and institutions (Gintis, 2009; Bowles and Gintis, 2011). Gintis showed that norms are not exogenous or static but evolve in tandem with formal institutions and social practices. Preferences themselves can be reshaped through participatory processes, collective experiences, and the design of social environments. This implies that sustainability transitions can benefit from policies that deliberately foster pro-social and pro-environmental norms through social learning, civic participation, and inclusive governance.

Ecohesion highlights this dynamic, treating social cohesion not only as a stock variable to be preserved, but as a relational process that can be activated and cultivated. The role of policy is not merely to redistribute or regulate, but also to shape the symbolic and institutional scaffolding that enables cooperation and solidarity. This understanding aligns with Gintis's vision of agents as embedded in social contexts—where behaviors are co-produced by internalized norms, institutional rules, and peer influence.

Finally, Ecohesion provides a conceptual bridge between ecological macroeconomics, behavioral modeling, and political theory. It encourages the inclusion of social cohesion indicators in both qualitative and quantitative models of transition, and suggests that neglecting these dimensions results in the underestimation of risks and a misalignment between policy goals and societal readiness. The next section further operationalizes this view by identifying four key conditions—4SCE—that form the foundation of the Ecohesion framework.

3.2 The four social conditions for ecohesion (4SCE)

The Ecohesion framework identifies four foundational social conditions (4SCE) that act as enablers of sustainable transitions: access to basic goods and services, decent jobs, time affluence, and social capital. These are not independent policy targets, but co-evolving dimensions of a resilient and equitable socio-ecological system. They operate together to shape societal capacity to support, absorb, and drive systemic transformation. While each relates to economic inequality, they are conceptually and functionally separate from it, as indicated by their positioning relative to economic distribution in Figure 2.

Building off of the literature on Just Transition described in Section 2, Ecohesion looks to advance the debates by offering a structured and operational lens in which various aspects of social cohesion feedback on the policy process itself. In doing so, Ecohesion translates a literature which primarily proposes normative visions of sustainability and fairness into an interconnected set of policy levers that can be integrated into models and institutional frameworks with particular attention for the dynamic second-order effects these policies may have.

The 4SCE identified here are conceptually distinct, highlighting what we see as independently critical aspects of social cohesion. In this sense the various aspects are not substitutable, and a critical deficiency in any of the four risks triggering a negatively reinforcing feedback loop with reduced effectiveness of transition policies and subsequent increased negative distributional effects from transitions themselves.

This being said, the Ecohesion also recognizes the clear relational dynamics among the four conditions. The 4SCE, while conceptually distinct, are mutually reinforcing: access to basic services supports labor market stability and time sovereignty; decent jobs increase access to both services and autonomy; time affluence fosters civic engagement and norm adoption; and social capital amplifies the effectiveness of all other policy domains by enhancing trust and legitimacy. Rather than being add-ons to transition strategies, the 4SCE constitute a feedback system that shapes the political feasibility, social acceptability, and adaptive resilience of transition pathways. This systemic interdependence contrasts with the fragmented treatment often found in existing policy frameworks. For example, Just Transition strategies tend to focus on employment and redistribution, but often neglect time inequalities or the role of relational goods. The Wellbeing Economy discourse, while normatively ambitious, lacks an operational grammar to link macroeconomic modeling with social cohesion dynamics. Ecohesion provides this missing connective tissue.

The 4SCE have also been selected to be practically quantifiable, with relevant data from large-scale surveys available for a number of geographical areas.

3.2.1 Access to basic goods and services

Universal and equitable access to health, education, housing, mobility, food, and digital connectivity is the foundation of a stable society. Access to these basic goods and services, either through public or private provision, enhances basic capabilities and reduces social vulnerability. It also conditions the effectiveness of other policies: workers without access to child care or public transport are less able to benefit from new green jobs; families without adequate housing or energy services may resist decarbonization policies that increase living costs.

Public provisioning of services is particularly central, as it acts as a decommodifying force that increases security and dignity. It also builds the symbolic basis of trust: people who feel protected are more likely to support long-term collective goals, even when short-term sacrifices are required.

3.2.2 Decent jobs

Work is not only a source of income, but of identity, meaning, and recognition. As the ecological transition reshapes production systems, decent work becomes a key site of political negotiation. Without quality jobs, the green transition may reproduce or deepen social inequalities.

Ecohesion understands decent jobs not as isolated labor contracts, but as arising from a broader social and economic ecosystem. Labor markets do not adjust frictionlessly; they require collective coordination, reskilling, and institutional support. The availability of decent jobs does not arise naturally, even in a rapidly growing economy, but must be created by social and political forces which govern labor norms and laws.

3.2.3 Time affluence

Time affluence—the capacity to control and allocate one's time freely—is emerging as a key dimension of sustainable well-being. Working time reduction and care policies can promote lower-carbon lifestyles, increase gender equality, and support democratic participation (Cieplinski et al., 2023).

Yet time autonomy depends on the other conditions. Without income security or basic services, time affluence becomes a privilege rather than a right. Moreover, time affluence enhances the ability to engage in trust-building, education, and civic life—thus feeding into the reproduction of social capital. Time is therefore both a condition and a multiplier of transition capacities.

3.2.4 Social capital

Social capital refers to the norms, networks, and trust that enable cooperation under conditions of uncertainty and complexity. As Gintis (2009) argues, social cooperation is not reducible to incentives alone—it emerges from the co-evolution of institutional design, peer monitoring, and norm internalization.

Ecohesion emphasizes the enabling role of social capital for facilitating effective transition policies. For instance, communities with higher levels of trust are more effective in managing shared resources, supporting behavioral shifts, and resisting disinformation. Moreover, social capital increases the throughput of public policy: the same program (e.g., a training scheme or a mobility subsidy) will have different outcomes depending on whether it is implemented in a context of solidarity or suspicion.

3.3 Social innovations to enable transition policies

The 4SCE form a multidimensional feedback system that enhances the social metabolism of transition. Their combined presence creates virtuous cycles of inclusion, legitimacy, and collective efficacy. Their absence, by contrast, can lead to backlash, disengagement, and the failure of technically optimal but socially unsound policies.

The four social conditions for Ecohesion can be visualized as key enablers located at the intersection of individual well-being, institutional trust, and collective capacity for change. Each condition contributes in distinct yet interconnected ways to the material and symbolic infrastructure needed to navigate transitions.

Existing models of the transition, being primarily data-driven, tend to project futures that mirror the present or past, neglecting the transformative changes required and leaving key aspects of societal dynamics exogenous to the model. Instead, transitions unfold in real societies, with contestation, asymmetries, and political friction. The 4SCE framework allows modelers to incorporate legitimacy constraints into scenario design, and policymakers to align social infrastructure with environmental goals.

Finally, Ecohesion highlights an empirical gap in the current literature. Many modeling frameworks acknowledge the importance of trust, fairness, or participation—but few integrate them operationally. Future research must assess how social innovations and transformative policy contribute to the reproduction of social cohesion. This will be key to validating Ecohesion not only as a conceptual framework, but as a practical guide for transformative policy.

4 Operationalizing ecohesion

Turning Ecohesion from a conceptual framework into a practical guide for research, modeling, and policy evaluation requires a rethinking of both the tools we use and the assumptions we make. Rather than treating social cohesion as a static backdrop or residual effect, Ecohesion places it at the center of transition analysis. This entails developing methodologies capable of capturing the dynamic feedbacks between social conditions and ecological outcomes, and recognizing that the feasibility of sustainability transitions hinges on political legitimacy, public support, and institutional adaptability.

4.1 Modeling ecohesion

Mainstream models, especially Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs), have historically prioritized emissions trajectories, technological substitution, and cost optimization. While increasingly sophisticated in representing physical systems, they tend to treat society as homogeneous and passive—assuming stable preferences, smooth implementation, and linear policy effects. Ecohesion addresses this limitation by emphasizing the endogenous and co-evolving nature of social structures, behaviors, and institutions.

To operationalize this perspective, new modeling strategies are needed—ones that can capture the way in which the four social conditions identified in the Ecohesion framework influence, and are influenced by, ecological transitions. Ecological macroeconomic models offer one such avenue. These models, grounded in post-Keynesian or stock-flow consistent traditions, allow for the simulation of complex interactions between fiscal policy, employment, inequality, and environmental outcomes. The EUROGREEN model, for example, incorporates public investment in universal services and working-time reduction as policy levers with both ecological and social effects (D'Alessandro et al., 2010; Cieplinski et al., 2021; Distefano and D'Alessandro, 2023). These dimensions can be extended further by endogenizing social cohesion indicators—such as time affluence or job quality—as structural determinants of economic resilience and sustainability.

System dynamics modeling offers a complementary perspective, especially suited to capturing path dependency, non-linear feedbacks, and institutional inertia. It enables researchers to represent how trust, perception of fairness, and social capital influence the uptake and effectiveness of ecological policies over time. Such dynamics are especially important when assessing the tipping points at which public support turns into resistance, or vice versa, in response to perceived injustices or coordination failures.

Agent-based modeling (ABM), a domain in which Herbert Gintis made pioneering contributions, provides a powerful framework for exploring the emergence of cooperation, norm diffusion, and behavioral heterogeneity under varying institutional settings. ABMs can simulate how social capital amplifies or dampens the reception of climate policies, how preferences adapt through peer influence, and how individual agency interacts with collective dynamics. They are particularly well-suited to analyze the bottom-up processes through which social cohesion evolves in response to policy design.

4.2 Ecohesion participatory and experimental methods

Yet modeling alone is not sufficient. Ecohesion also calls for participatory and experimental approaches that acknowledge the contested and political nature of transitions. Policies designed in isolation from those who experience them risk failure. Thus, empirical and qualitative methods—such as deliberative forums, participatory foresight, or co-design labs—are crucial to identify combinations of interventions that are not only technically sound but socially meaningful and normatively acceptable. These methods allow for a richer understanding of how legitimacy is constructed, how trade-offs are perceived, and how trust can be built or eroded over time.

In parallel, institutional experimentation at the territorial level can offer valuable insights. Pilot programs—such as local implementations of universal service schemes, cooperative childcare initiatives, or community-based time banking—can help test the operational relevance of the four social conditions. Such initiatives provide real-world laboratories in which the assumptions of the Ecohesion framework can be refined, and where the links between cohesion and transition capacity can be empirically validated.

Finally, to integrate Ecohesion into policy processes, a shift in measurement frameworks is required. Indicators that capture the quality and distribution of services, the stability and meaning of employment, the degree of control over one's time, and the depth of social trust must be developed and institutionalized. These indicators should not be treated as secondary to carbon budgets or GDP growth, but as core metrics of transition readiness. They can inform both ex ante scenario analysis and ex post impact evaluation, allowing policymakers to adjust strategies in response to evolving social realities.

Ecohesion thus points toward a broader methodological transformation: from optimization to transformation, from cost-efficiency to capacity-building, and from isolated targets to relational systems. By embedding the four social conditions into both analytical tools and political practice, the framework offers a path toward sustainability that is not only technically feasible but also socially rooted and institutionally credible.

Experimental economics and survey-based methods can further complement these modeling and participatory efforts. By conducting controlled experiments and structured surveys, researchers can improve both the internal validity of behavioral assumptions—through hypothesis testing and parameter estimation—and the external validity—by ensuring that findings generalize across contexts. More importantly, such approaches help uncover endogenous drivers of preference change, revealing how individual motivations and social influences evolve in response to policy designs.

Identifying cognitive and social factors that underpin behavioral change opens the door to embedding realistic feedback loops within simulation models. These loops can capture the co-evolution of individual and group behaviors, as well as the dynamics of socio-economic structures at the macro level. By parametrizing models with experimentally derived estimates and survey insights, Ecohesion-driven simulations achieve greater fidelity in representing how norms, trust, and social learning shape transition trajectories.

Moreover, if the transition toward sustainability is a transformation we aim to govern, it is essential to detect potential behavioral barriers and to activate levers at the level of cognitive functions and social processes. Understanding the motivational underpinnings—ranging from risk perceptions to collective identity—allows policymakers to design interventions that lower resistance and foster widespread engagement. In this way, combining experimental, survey, and modeling approaches enhances the feasibility of global collective action and ensures that policy pathways are both scientifically robust and socially acceptable.

5 Conclusion

This paper has introduced Ecohesion as a conceptual framework for understanding and guiding sustainability transitions that are not only ecologically sound but also socially just and politically feasible. By identifying four foundational social conditions—access to basic goods and services, decent jobs, time affluence, and social capital—Ecohesion reframes the discourse on transition to foreground the enabling role of social cohesion in ecological transformation.

The framework responds to a key limitation in prevailing models and narratives of sustainability: the tendency to treat society as a stable background or a source of friction, rather than as a dynamic system with its own agency, structure, and feedbacks. In doing so, Ecohesion moves beyond cost-efficiency and technological substitution to embrace a relational understanding of transition, where human needs, institutional trust, and collective capacities are at the center of the equation.

Throughout the paper, we have argued that social cohesion is not simply a co-benefit of well-designed transition policies, but a prerequisite for their legitimacy, stability, and effectiveness. Transitions that fail to secure people's access to basic services, that disregard time poverty, or that neglect the erosion of trust in institutions are likely to face backlash, inertia, or superficial compliance. Conversely, when the 4SCE are strengthened in tandem, they can generate virtuous cycles of engagement, fairness, and resilience that expand the horizon of what is politically and socially possible.

Ecohesion also builds explicitly on the intellectual legacy of Herbert Gintis. His work on norm internalization, cooperation, institutional co-evolution, and agent-based modeling provides a foundation for thinking about transition not as a technical problem, but as a collective and contested process of social learning and transformation. In this sense, Ecohesion is both a tribute to and an extension of Gintis's interdisciplinary vision—one that recognizes the moral and material entanglement of individual behavior, social structure, and institutional design.

Looking forward, Ecohesion opens several promising avenues for research and practice. It calls for new generations of models that incorporate social dynamics and legitimacy constraints; for indicators that capture the relational infrastructure of transition; for participatory methods that co-produce knowledge and legitimacy; and for policy experiments that test the synergies between ecological and social innovation. Importantly, it calls for a reconfiguration of policy goals—not just reducing emissions or boosting growth, but enhancing the capacity of societies to navigate change collectively and justly.

In the spirit of Herbert Gintis, Ecohesion challenges us to imagine transitions not only as systems problems, but as human problems. That is, problems that require us to understand how people cooperate, what they care about, and under what conditions they are willing to change. Meeting this challenge will be essential for building sustainable futures within planetary boundaries—and doing so in ways that are democratic, inclusive, and resilient.

Statements

Author contributions

SD'A: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. PG: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. JP: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by the European Union's Horizon Europe programme (European Commission) under grant agreements No. 101094546 (WISER—Well-being in a Sustainable Economy Revisited) and No. 101137914 (MAPS—Models, Assessment and Policies for Sustainability).

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants to the Ecohesion Collective for their insights and comments during the development of this paper. This work also draws inspiration from the interdisciplinary contributions of Herbert Gintis, whose legacy we honor through this conceptual effort.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Abram S. Atkins E. Dietzel A. Jenkins K. Kiamba L. Kirshner J. et al . (2022). Just transition: a whole-systems approach to decarbonisation. Clim. Policy22, 1033–1049. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2022.2108365

2

Allcott H. Rogers T. (2014). The short-run and long-run effects of behavioral interventions: experimental evidence from energy conservation. Am. Econ. Rev.104, 3003–3037. doi: 10.1257/aer.104.10.3003

3

Arto I. Capellán-Pérez I. Lago R. Bueno G. Bermejo R. (2016). The energy requirements of a developed world. Energy Sustain. Dev.33, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.esd.2016.04.001

4

Bicchieri C. (2017). Norms in the Wild: How to Diagnose, Measure, and Change Social Norms. Oxford University Press, Oxford. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190622046.001.0001

5

Bowles S. (1998). Endogenous preferences: the cultural consequences of markets and other economic institutions. J. Econ. Lit.36, 75–111. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2564952

6

Bowles S. Gintis H. (2011). A Cooperative Species: Human Reciprocity and Its Evolution. Princeton University Press, Princeton. doi: 10.23943/princeton/9780691151250.001.0001

7

Bowles S. Gintis H. (2013). A Cooperative Species: human Reciprocity and its Evolution, Economics, Anthropology, Biology. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

8

Bowles S. Polania-Reyes S. (2012). Economic incentives and social preferences: substitutes or complements?J. Econ. Lit.50, 368–425. doi: 10.1257/jel.50.2.368

9

Brand-Correa L. I. Steinberger J. K. (2017). A framework for decoupling human need satisfaction from energy use. Ecol. Econ.141, 43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.05.019

10

Bucciol A. Tavoni A. Veronesi M. (Eds.). (2023). Behavioural Economics and the Environment: A Research Companion. London: Taylor and Francis. doi: 10.4324/9781003172741

11

Cahen-Fourot L. (2020). Contemporary capitalisms and their social relation to the environment. Ecol. Econ.172:106634. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106634

12

Camerer C. F. (2003). Behavioral Game Theory: Experiments in Strategic Interaction. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

13

Cieplinski A. D'Alessandro S. Distefano T. Guarnieri P. (2021). Coupling environmental transition and social prosperity: a scenario-analysis of the Italian case. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn.57, 265–278. doi: 10.1016/j.strueco.2021.03.007

14

Cieplinski A. D'Alessandro S. Dwarkasing C. Guarnieri P. (2023). Narrowing women's time and income gaps: an assessment of the synergies between working time reduction and universal income schemes. World Dev.167:106233. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2023.106233

15

Creutzig F. Niamir L. Bai X. Callaghan M. Cullen J. Díaz-José J. et al . (2022). Demand-side solutions to climate change mitigation consistent with high levels of well-being. Nat. Clim. Change12, 36–46. doi: 10.1038/s41558-021-01219-y

16

Creutzig F. Roy J. Lamb W. F. Azevedo I. M. L. Bruine de Bruin W. Dalkmann H. et al . (2018). Towards demand-side solutions for mitigating climate change. Nat. Clim. Change8, 260–263. doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0121-1

17

D'Alessandro S. Cieplinski A. Distefano T. Dittmer K. (2020). Feasible alternatives to green growth. Nat. Sustain.3, 329–335. doi: 10.1038/s41893-020-0484-y

18

D'Alessandro S. Luzzati T. Morroni M. (2010). Energy transition towards economic and environmental sustainability: feasible paths and policy implications. J. Clean. Prod.18, 532–539. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2010.02.022

19

Distefano T. D'Alessandro S. (2023). Introduction of the carbon tax in Italy: is there room for a quadruple-dividend effect?Energy Econ.120:106578. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2023.106578

20

Escobar A. (2015). Degrowth, postdevelopment, and transitions: a preliminary conversation. Sustain. Sci.10, 451–462. doi: 10.1007/s11625-015-0297-5

21

Fanning A. L. O'Neill D. W. Hickel J. Roux N. (2022). The social shortfall and ecological overshoot of nations. Nat. Sustain.5, 26–36. doi: 10.1038/s41893-021-00799-z

22

Fanning A. L. Raworth K. (2025). Doughnut of social and planetary boundaries monitors a world out of balance. Nature646, 47–56. doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-09385-1

23

Fehr E. Fischbacher U. Gächter S. (2002). Strong reciprocity, human cooperation, and the enforcement of social norms. Hum. Nat.13, 1–25. doi: 10.1007/s12110-002-1012-7

24

Fehr E. Gächter S. (2002). Altruistic punishment in humans. Nature415, 137–140. doi: 10.1038/415137a

25

Fehr E. Schmidt K. M. (1999). A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. Q. J. Econ.114, 817–868. doi: 10.1162/003355399556151

26

Feola G. (2020). Capitalism in sustainability transitions research: time for a critical turn?Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit.35, 241–250. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2019.02.005

27

Fischbacher U. Gächter S. Fehr E. (2001). Are people conditionally cooperative? Evidence from a public goods experiment. Econ. Lett.71, 397–404. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1765(01)00394-9

28

Fitzpatrick N. Parrique T. Cosme I. (2022). Exploring degrowth policy proposals: a systematic mapping with thematic synthesis. J. Clean. Prod.365:132764. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.132764

29

Galanis G. Napoletano M. Popoyan L. Sapio A. Vardakoulias O. (2025). Defining just transition. Ecol. Econ.227:108370. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2024.108370

30

Geels F. W. (2019). Socio-technical transitions to sustainability: a review of criticisms and elaborations of the multi-level perspective. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 39, 187–201. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2019.06.009

31

Ghosh B. Ramos-Mejía M. Machado R. C. Yuana S. L. Schiller K. (2021). Decolonising transitions in the Global South: towards more epistemic diversity in transitions research. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit.41, 106–109. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2021.10.029

32

Gintis (2000). Strong reciprocity and human sociality. J. Theor. Biol. 206:169. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2000.2111

33

Gintis (2007). A framework for the unification of the behavioral sciences. Behav. Brain Sci. 30:1. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X07000581

34

Gintis (2009). The Bounds of Reason: Game Theory and the Unification of the Behavioral Sciences. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

35

Gintis (2016). Individuality and Entanglement: The Moral and Material Bases of Social Life. Princeton University Press, Princeton. doi: 10.2307/j.ctvc779cx

36

Gneezy U. Rustichini A. (2000). A fine is a price. J. Leg. Stud.29, 1–17. doi: 10.1086/468061

37

Gucciardi G. Luzzati T. (2024). Living in the ‘doughnut': reconsidering the boundaries via composite indicators. Ecol. Indic.169:112864. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2024.112864

38

Hafner S. Anger-Kraavi A. Monasterolo I. Jones A. (2020). Emergence of new economics energy transition models: a review. Ecol. Econ.177:106779. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106779

39

Hardt L. O'Neill D. W. (2017). Ecological macroeconomic models: assessing current developments. Ecol. Econ.134, 198–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.12.027

40

Heffron R. J. (2021). What is the “just transition”?, in Achieving a Just Transition to a Low-Carbon Economy, ed R. J. Heffron (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 9–19. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-89460-3_2

41

Herrmann B. Thöni C. Gächter S. (2008). Antisocial punishment across societies. Science319, 1362–1367. doi: 10.1126/science.1153808

42

Hickel J. Kallis G. (2020). Is green growth possible?New Polit. Econ.25, 469–486. doi: 10.1080/13563467.2019.1598964

43

Hofferberth E. (2025). Post-growth economics as a guide for systemic change: theoretical and methodological foundations. Ecol. Econ.230:108521. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2025.108521

44

Hummel D. Maedche A. (2019). How effective is nudging? A quantitative review on the effect sizes and limits of empirical nudging studies. J. Behav. Exp. Econ.80, 47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2019.03.005

45

IPCC (2022). Annex III: Scenarios and Modelling Methods in: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

46

Jordán F. (2025). Varieties of capitalism and environmental performance. Ecol. Econ.227:108362. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2024.108362

47

Kallis G. Hickel J. O'Neill D. W. Jackson T. Victor P. A. Raworth K. et al . (2025). Post-growth: the science of wellbeing within planetary boundaries. Lancet Planet. Health9, e62–e78. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(24)00310-3

48

Kedward K. Gonon M. (2025). Avenues for exploring nature scenarios in ecological macroeconomic models. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.5200146

49

Knack S. Keefer P. (1997). Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. Q. J. Econ.112, 1251–1288. doi: 10.1162/003355300555475

50

Köhler J. Geels F. W. Kern F. Markard J. Onsongo E. Wieczorek A. et al . (2019). An agenda for sustainability transitions research: state of the art and future directions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit.31, 1–32. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2019.01.004

51

Markard J. Raven R. Truffer B. (2012). Sustainability transitions: an emerging field of research and its prospects. Res Policy Spec. Sect. Sustain. Transit.41, 955–967. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2012.02.013

52

Markard J. Truffer B. (2008). Technological innovation systems and the multi-level perspective: towards an integrated framework. Res. Policy37, 596–615. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2008.01.004

53

Mathias J. (2020). Grounding social foundations for integrated assessment models of climate change. Earth's Futur.8:e2020EF001573. doi: 10.1029/2020EF001573

54

Mazar A. Tomaino G. Carmon Z. Wood W. (2021). Habits to save our habitat: using the psychology of habits to promote sustainability. Behav. Sci. Policy7, 75–89. doi: 10.1177/237946152100700207

55

McCauley D. Heffron R. (2018). Just transition: integrating climate, energy and environmental justice. Energy Policy119, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2018.04.014

56

McCollum D. L. Gambhir A. Rogelj J. Wilson C. (2020). Energy modellers should explore extremes more systematically in scenarios. Nat. Energy5, 104–107. doi: 10.1038/s41560-020-0555-3

57

McElroy C. O'Neill D. W. (2025). The labour and resource use requirements of a good life for all. Glob. Environ. Change92:103008. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2025.103008

58

Mertens S. Herberz M. Hahnel U. J. J. Brosch T. (2022). The effectiveness of nudging: a meta-analysis of choice architecture interventions across behavioral domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.119:e2107346118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2107346118

59

Milinski M. Sommerfeld R. D. Krambeck H. -J. Reed F. A. Marotzke J. (2008). The collective-risk social dilemma and the prevention of simulated dangerous climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.105, 2291–2294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709546105

60

Newell P. Mulvaney D. (2013). The political economy of the ‘just transition.' Geogr. J.179, 132–140. doi: 10.1111/geoj.12008

61

Nikas A. Doukas H. Papandreou A. (2019). “A detailed overview and consistent classification of climate-economy models,” in Understanding Risks and Uncertainties in Energy and Climate Policy: Multidisciplinary Methods and Tools for a Low Carbon Society, eds H. Doukas, A. Flamos, and J. Lieu (Cham: Springer International Publishing). doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-03152-7_1

62

Nishi A. Shirado H. Rand D. G. Christakis N. A. (2015). Inequality and visibility of wealth in experimental social networks. Nature526, 426–429. doi: 10.1038/nature15392

63

Oakes R. Cieplinski A. Parrado G. Ragnarsdóttir K. V. Ólafsdóttir A. H. Pastor A. et al . (2020). Review of social and demographic indicators and impacts of energy transitions (Deliverable No. 5.1). LOCOMOTION, Valladolid.

64

O'Neill D. W. Fanning A. L. Lamb W. F. Steinberger J. K. (2018). A good life for all within planetary boundaries. Nat. Sustain.1, 88–95. doi: 10.1038/s41893-018-0021-4

65

Ostrom E. (2010). Polycentric systems for coping with collective action and global environmental change. Glob. Environ. Change20, 550–557. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.07.004

66

Otto I. M. Donges J. F. Cremades R. Bhowmik A. Hewitt R. J. Lucht W. et al . (2020). Social tipping dynamics for stabilizing Earth's climate by 2050. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.117, 2354–2365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1900577117

67

Prentice D. Paluck E. L. (2020). Engineering social change using social norms: lessons from the study of collective action. Curr. Opin. Psychol.35, 138–142. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.06.012

68

Proctor J. C. (2023). Expanding the possible: exploring the role for heterodox economics in integrated climate-economy modeling. Rev. Evol. Polit. Econ. 4:537. doi: 10.1007/s43253-023-00098-7

69

Raworth K. (2017). Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist. White River Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing.

70

Rezai A. Stagl S. (2016). Ecological macroeconomics: introduction and review. Ecol. Econ.121, 181–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.12.003

71

Salin M. Kedward K. Dunz N. (2024). Assessing Integrated Assessment Models for Building Global Nature-Economy Scenarios (Working Paper No. 959). Banque de France.

72

Steg L. Vlek C. (2009). Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: an integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol.29, 309–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2008.10.004

73

Stoknes P.E. Collste D. Cornell S.E. Callegari B. Spittler N. Gaffney O. et al . (2025). The Earth4All scenarios: human wellbeing on a finite planet towards 2100. Glob. Sustain.8:e22. doi: 10.1017/sus.2025.10013

74

Svartzman R. Dron D. Espagne E. (2019). From ecological macroeconomics to a theory of endogenous money for a finite planet. Ecol. Econ.162, 108–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.04.018

75

Tavoni A. Dannenberg A. Kallis G. Löschel A. (2011). Inequality, communication, and the avoidance of disastrous climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.108, 11825–11829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102493108

76

Trutnevyte E. (2019). Societal transformations in models for energy and climate policy: the ambitious next step. One Earth1, 423–433. doi: 10.1016/j.oneear.2019.12.002

77

UNFCCC (2010). Report of the Conference of the Parties on Its Sixteenth Session Held in Cancun from 29 November to 10 December 2010. UN-Framework Convention on Climate Change, Cancún.

78

Van Eynde R. Horen Greenford D. O'Neill D. W. Demaria F. (2024). Modelling what matters: how do current models handle environmental limits and social outcomes?J. Clean. Prod.476:143777. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.143777

79

Vélez-Henao J. A. Pauliuk S. (2023). Material requirements of decent living standards. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 14206–14217. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.3c03957

80

Vogel J. Steinberger J. K. O'Neill D. W. Lamb W. F. Krishnakumar J. (2021). Socio-economic conditions for satisfying human needs at low energy use: an international analysis of social provisioning. Glob. Environ. Change69:102287. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102287

81

Vogel J. Van Eynde R. Di Domenico L. Fearon S. Dallinger L. Beigi T. et al . (2025). COMPASS: a social-ecological macroeconomic model for guiding pathways to equitable human wellbeing within planetary boundaries (Deliverable No. 4.2), Barcelona.

82

Wang X. Lo K. (2021). Just transition: a conceptual review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci.82:102291. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2021.102291

83

Young H. P. (2015). The evolution of social norms. Annu. Rev. Econ.7, 359–387. doi: 10.1146/annurev-economics-080614-115322

84

Zorell C. V. (2020). Nudges, norms, or just contagion? A theory on influences on the practice of (non-)sustainable behavior. Sustainability12:10418. doi: 10.3390/su122410418

Summary

Keywords

ecohesion, social cohesion, Herbert Gintis, agent-based modeling, ecological macroeconomics, time affluence, social capital, system dynamics

Citation

D'Alessandro S, Guarnieri P and Proctor J (2025) Ecohesion: operationalizing the link between social cohesion and ecological transformation. Front. Behav. Econ. 4:1650899. doi: 10.3389/frbhe.2025.1650899

Received

20 June 2025

Revised

18 November 2025

Accepted

26 November 2025

Published

19 December 2025

Volume

4 - 2025

Edited by

Sebastian Ille, American University in Cairo, Egypt

Reviewed by

Asier Arcos-Alonso, University of the Basque Country, Spain

Chiara Grazini, University of Tuscia, Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 D'Alessandro, Guarnieri and Proctor.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Simone D'Alessandro, simone.dalessandro@unipi.it

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.