Abstract

Immunotherapy has emerged as a powerful approach in treating various diseases, yet its success often hinges on the efficacy of adjuvants, agents that boost immune responses to therapeutic targets. Traditional adjuvants have offered foundational support but may fall short in achieving the specificity and potency required for advanced therapies. This review highlights a new generation of adjuvants poised to address these limitations. We explore a range of innovative agents, including non-inflammatory nucleic acid adjuvants, bacterial derivatives, and synthetic molecules, which are redefining the role of adjuvants in immunotherapy. These emerging agents hold promise for enhancing immune responses while tailoring therapies to specific disease contexts, from cancer to infectious diseases. By examining the applications and potential of these adjuvants, this review aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of how they can advance immunotherapy to new levels of efficacy and precision. Through the development of these novel adjuvants, immunotherapy stands to achieve more targeted and sustained impacts, paving the way for improved outcomes in patient care.

1 Introduction

Immunotherapy represents a paradigm shift in modern medicine, harnessing the intricacies of the immune system to combat diseases such as cancer, infectious diseases, and autoimmune disorders. Distinguished by its precision and potential for durable responses, immunotherapy has ushered in transformative advancements, including immune checkpoint inhibitors, CAR-T cell therapies, and therapeutic cancer vaccines (Dagher et al., 2023; Wallis et al., 2023; Chasov et al., 2024). Despite these milestones, the efficacy of these strategies frequently relies on the integration of adjuvants, which are agents that enhance immune responses by potentiating antigen recognition, activation of immune cells, and the downstream orchestration of adaptive immunity (Facciolà et al., 2022). Traditional adjuvants, such as alum, MF59, and Freund’s adjuvant, have laid the foundation for vaccine development and immunostimulation for decades. However, their utility in advanced immunotherapy is limited by their narrow spectrum of immune activation. For instance, most traditional adjuvants fail to effectively polarize Th1 or Th17 immune responses, which are essential for combating intracellular pathogens and tumours. Furthermore, their inability to induce robust cross-presentation of antigens hinders the generation of cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL)-mediated immunity (Wang and Xu, 2020; Facciolà et al., 2022). These constraints necessitate the development of novel adjuvants designed to complement the sophisticated demands of modern immunotherapy.

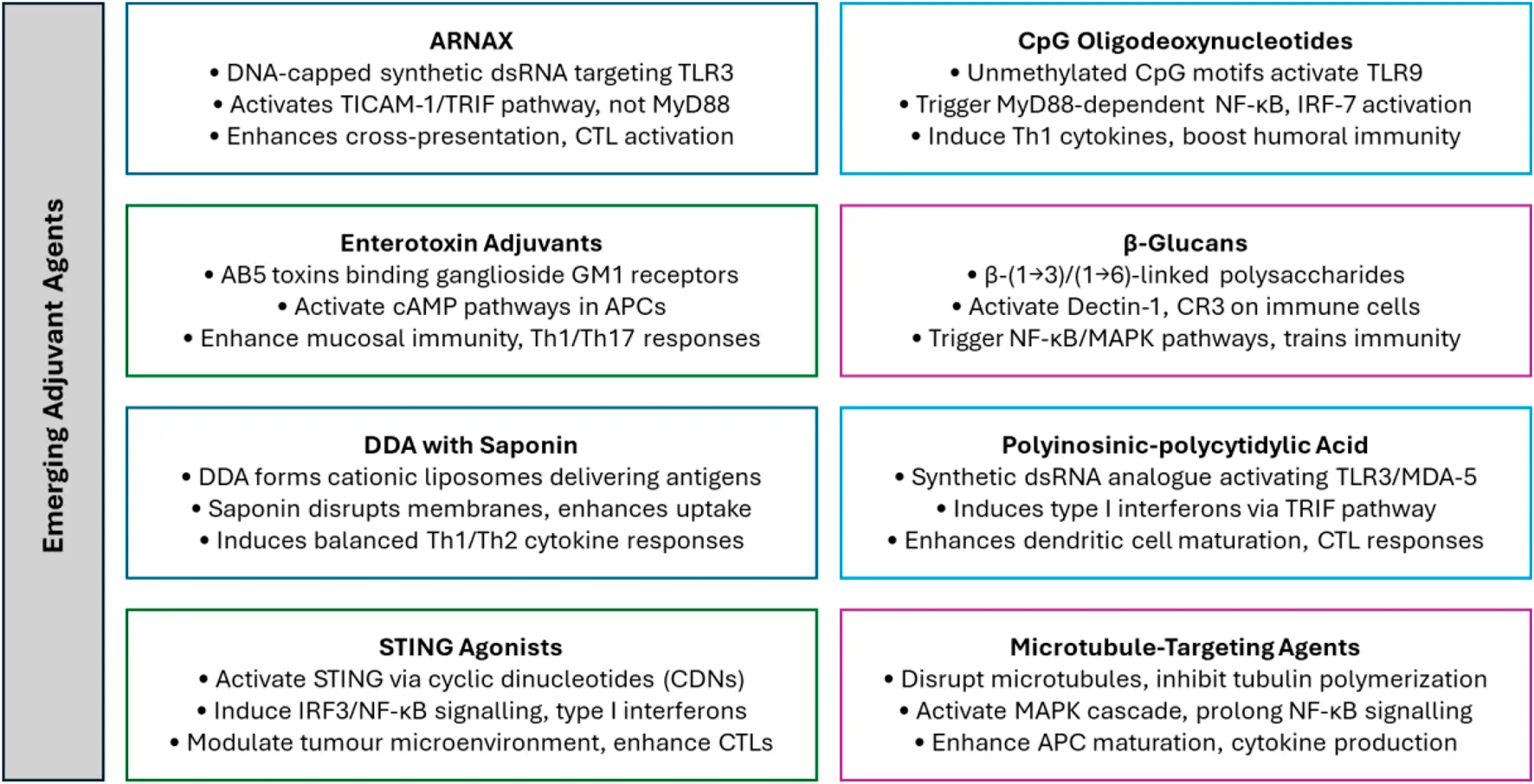

Several emerging adjuvants have been developed to address these shortcomings, leveraging advances in molecular immunology and material science (O’Hagan et al., 2020; Pulendran et al., 2021). These adjuvants, including ARNAX, CpG oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs), STING agonists, beta-glucan derivatives, and synthetic molecules such as poly(I:C), possess unique mechanisms of action that modulate immune responses with greater specificity and efficacy. These emerging agents not only enhance immune responses but also provide tailored solutions for specific therapeutic contexts, from tumour immunotherapy to prophylactic and therapeutic vaccines targeting infectious diseases (Desai et al., 2024a). The rapid evolution of these adjuvants underscores their potential to redefine immunotherapeutic strategies. This review aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of these novel agents, focusing on their mechanisms of action, the immunological pathways they engage, and their potential applications in enhancing the efficacy of immunotherapy.

2 Role and need of adjuvants

Adjuvants play an indispensable role in immunotherapy and vaccine development, acting as critical enhancers of the immune system’s ability to mount effective and durable responses. By amplifying the immune recognition of antigens and directing immune polarization, adjuvants bridge the gap between innate and adaptive immunity (Schijns et al., 2020). Their primary function is to compensate for the weak immunogenicity of modern antigen formulations, such as recombinant proteins and synthetic peptides, which often fail to elicit robust immune responses without additional stimulation (Correa et al., 2022b). Moreover, adjuvants significantly enhance the efficiency of antigen presentation, facilitating the activation of APCs like dendritic cells and macrophages, which process antigens and present them to T cells to initiate adaptive immunity (Awate et al., 2013).

Adjuvants not only enhance the magnitude of immune responses but also modulate their quality and duration. By polarizing the immune response, adjuvants can promote Th1 pathways, favouring cellular immunity for intracellular pathogens and cancer, or Th2 responses for extracellular pathogens (Sarkar et al., 2019). In addition, some adjuvants can stimulate Th17 responses, which are crucial for mucosal immunity. Furthermore, adjuvants reduce the required antigen dose in vaccines (a phenomenon known as antigen sparing) and ensure the generation of immunological memory, which is vital for long-term protection and therapeutic efficacy (Lavelle and McEntee, 2024). Figure 1 shows a schematic representation illustrating the mechanism by which adjuvants enhance vaccine immunogenicity.

FIGURE 1

Role of adjuvants in enhancing vaccine immunogenicity. (A) Vaccines without adjuvants induce limited APC maturation, modest cytokine production, and weaker adaptive immune responses. (B) Vaccines with adjuvants enhance APC recruitment and maturation, boost cytokine production, and promote stronger T cell activation and antibody responses, leading to broader and more durable immunity with improved dose efficiency. Adapted with permission from Lavelle and McEntee (2024), Copyright Springer Nature 2024.

Despite their utility, traditional adjuvants are constrained by significant limitations. Alum, one of the most extensively used adjuvants, predominantly induces humoral immunity with a Th2 bias, making it suboptimal for applications requiring cellular immunity, such as cancer immunotherapy. Oil-based adjuvants, such as Freund’s Complete Adjuvant, though effective, are associated with severe local and systemic toxicities, rendering them unsuitable for human use (McKee and Marrack, 2017; Moni et al., 2023). Modern adjuvants like MF59 and AS03 have improved the delivery of antigens to APCs, but their ability to induce specific immune polarization, particularly robust Th1 and CTL responses, remains inadequate in many therapeutic contexts (Ko and Kang, 2018; Roman et al., 2024).

The need for novel adjuvants has become increasingly apparent as immunotherapy advances toward more sophisticated applications, including personalized medicine, cancer vaccines, and combination therapies. These emerging immunotherapeutic strategies demand adjuvants that can precisely modulate immune pathways, overcome immune evasion mechanisms, and ensure broad efficacy across diverse patient populations (Verma et al., 2023). The global health landscape has also highlighted additional challenges that must be addressed by next-generation adjuvants. These include the need for thermostable and cost-effective formulations suitable for use in resource-limited settings and adjuvants that demonstrate safety and tolerability across different age groups and immunological profiles (Qi and Fox, 2021). Additionally, the increasing integration of adjuvants into combination therapies requires compatibility with other immunotherapeutic agents, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies, while minimizing systemic toxicity and off-target effects (Lykins and Fox, 2023).

As the field of immunotherapy continues to evolve, the demand for adjuvants that can meet the diverse requirements of these therapies is only increasing. The development of next-generation adjuvants represents a critical step toward achieving the full potential of immunotherapy by enhancing efficacy, improving safety, and expanding the scope of therapeutic and preventive strategies.

3 Emerging adjuvants in immunotherapy

The development of novel adjuvants signifies a pivotal advancement in immunotherapy, introducing innovative mechanisms to enhance and precisely modulate immune responses. Traditional adjuvants have well-established safety profiles but are limited in their ability to induce cellular immunity, primarily favouring humoral responses with a Th2 bias. They also lack the precision required for advanced therapeutic applications. In contrast, emerging adjuvants like ARNAX, CpG ODNs, and STING agonists offer targeted immune activation by engaging specific pathways such as TLR3, TLR9, and the STING pathway. These adjuvants enhance antigen presentation, promote robust Th1 and Th17 responses, and support long-term immunological memory, making them more effective for applications like cancer immunotherapy and vaccines targeting intracellular pathogens. However, their heightened immunostimulatory capacity may lead to risks such as systemic inflammation or cytokine storms, necessitating careful formulation and delivery strategies. This distinction underscores the potential of emerging adjuvants to overcome the limitations of traditional ones while highlighting the need for continued optimization to balance efficacy and safety. Table 1 provides a detailed summary of the mechanisms, target pathways, advantages, and limitations of each of the eight emerging adjuvants discussed in this manuscript, offering a comparative overview of their unique attributes.

TABLE 1

| Adjuvant | Mechanism of action | Target pathways | Advantages | Limitations | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARNAX | Activates TLR3 via TICAM-1 (TRIF) pathway, enhancing antigen presentation and Th1 polarization without inflammation | TLR3 | Non-inflammatory immune enhancement, promotes CTL and NK cell activation, cross-presentation for intracellular pathogens and cancer | Requires specialized stability for clinical use; limited data on large-scale production | Miyazaki et al. (2025) |

| CpG Oligodeoxy-nucleotides | Mimics microbial DNA to stimulate TLR9 in pDCs and B cells, inducing Th1 cytokines and promoting innate and adaptive immunity | TLR9 | Induces robust Th1 responses, enhances antibody production, effective in antiviral, antitumor, and mucosal immunity | Potential for systemic inflammation; delivery challenges for specific therapeutic applications | Kayraklioglu et al. (2021) |

| Enterotoxin Adjuvants | Stimulates mucosal immunity via AB5 toxin structure; enhances APC uptake and activation of Th1/Th17 responses | cAMP/PKA/ERK signaling pathways | Effective mucosal immunity, supports germinal center reactions, improves antibody avidity, reduced-toxicity variants available | Native toxins are highly toxic; modified versions require further validation | Crothers and Norton (2023) |

| β-Glucans | Activates immune cells through PRRs like Dectin-1 and CR3, inducing cytokine release and “trained immunity.” | NF-κB, MAPK signaling pathways | Enhances phagocytosis, promotes Th1/Th17 responses, supports innate and adaptive immunity, potential as dietary supplements and oral adjuvants | Structural variability affects activity; scalability and consistency in production need improvement | Jin et al. (2018) |

| DDA with Saponin | Combines lipid-based and natural surfactants to enhance antigen delivery to APCs, balancing Th1/Th2 responses | MHC Class II, IL-12, IL-4, IL-17 pathways | Balanced Th1/Th2 immunity, supports both humoral and cellular responses, effective in cancer vaccines and mucosal immunization | Potential membrane toxicity; requires optimized formulations for diverse vaccine applications | Marciani (2018) |

| Poly(I:C) | Mimics dsRNA to activate TLR3 and MDA-5, inducing IFN-α/β and promoting CTL and NK cell activity | TLR3, MDA-5 | Potent antiviral and antitumor immunity, induces Th1 responses, enhances dendritic cell maturation, versatile for peptide- and protein-based vaccines | Risk of systemic inflammation; instability in physiological conditions | Martins et al. (2015) |

| STING Agonists | Activates the STING pathway, producing type I interferons and modulating the tumour microenvironment | cGAS-STING pathway | Boosts antigen presentation, promotes cytotoxic T-cell activity, synergizes with checkpoint inhibitors, effective in cancer immunotherapy and systemic antitumor responses | Delivery challenges, particularly for systemic application; potential for overstimulation and inflammation | Gajewski and Higgs (2020) |

| Microtubule-Targeting Agents | Disrupts tubulin polymerization, inducing immune activation via MAPK and NF-κB signaling, and dendritic cell maturation | MAPK and NF-κB pathways | Dual antitumor and immunomodulatory effects, promotes Th1-biased responses, synergizes with checkpoint inhibitors and cancer vaccines | Cytotoxicity concerns at higher doses; limited clinical validation for immunotherapy applications | Sato-Kaneko et al. (2018) |

Summary of emerging vaccine adjuvants for immunotherapy.

3.1 ARNAX

ARNAX is a synthetic double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) adjuvant engineered for non-inflammatory immune enhancement. It features a dsRNA core capped with DNA, which enhances its stability and resistance to nuclease degradation (Seya et al., 2022). ARNAX specifically targets TLR3, a receptor predominantly found on certain dendritic cell subsets, including CD141+ dendritic cells in humans. Upon binding TLR3, ARNAX triggers immune signalling through TICAM-1 (also known as TRIF), bypassing the MyD88 pathway commonly associated with inflammation (Matsumoto et al., 2015; Seya et al., 2019). This distinct activation pathway recruits TICAM-1, which in turn activates transcription factors like NF-κB, IRF-3, and AP-1. This cascade enhances antigen presentation without the cytokine storm often triggered by other TLR ligands. By favouring TICAM-1 signalling, ARNAX promotes antigen presentation and Th1 polarization, enhancing cellular immunity while minimizing inflammatory responses (Seya et al., 2023). It facilitates cross-presentation, where dendritic cells present extracellular antigens on MHC class I molecules, activating CTLs. This capability is crucial for strong immune responses against intracellular pathogens and cancer cells, both of which require potent CTL activation (Jelinek et al., 2011). ARNAX’s ability to support Th1-biased responses further aids CTL and natural killer (NK) cell activation, strengthening the immune system’s response against infected or malignant cells. This profile makes ARNAX especially suited for cancer immunotherapy and vaccines targeting intracellular pathogens, where cellular immunity is critical (Matsumoto et al., 2020; Miyazaki et al., 2025).

3.2 CpG oligodeoxynucleotides

CpG ODN are synthetic DNA sequences with unmethylated CpG motifs that mimic microbial DNA, acting as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) to stimulate Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) in plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) and B cells (Kayraklioglu et al., 2021). Upon endosomal TLR9 recognition, they initiate a MyD88-dependent signalling cascade, activating transcription factors like NF-κB, IRF-7, and AP-1. This produces Th1 cytokines such as IL-12, TNF-α, and IFN-α, driving antiviral and antitumor immunity (Yu et al., 2017). CpG ODN enhance innate immunity through pro-inflammatory cytokine and type I interferon production, recruiting monocytes, NK cells, and neutrophils. They strengthen adaptive immunity by promoting antigen presentation, T-cell activation, and antibody production, fostering Th1 responses against intracellular pathogens and tumours (Tu et al., 2020). Additionally, they enhance dendritic cell maturation, B-cell proliferation, and humoral immunity (Matsuda and Mochizuki, 2023). CpG ODNs are classified into K-, D-, C-, and P-types, each with unique properties. K-types promote TNF-α and B-cell activation, while D-types strongly induce IFN-α via pDCs. C-types combine IFN-α and IL-6 induction, and P-types form ordered structures, eliciting robust IFN-α responses (Shirota and Klinman, 2017; Hartmann, 2023).

CpG ODN have diverse clinical applications. As vaccine adjuvants, they boost antibody titters, cellular, and mucosal immunity, exemplified by HEPLISAV-B®, a CpG-adjuvanted hepatitis B vaccine offering faster, stronger protection (Lee and Lim, 2021). They enhance responses to influenza and anthrax and improve mucosal immunity via oral or intranasal delivery (Givens et al., 2018; Muranishi et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2024c). In cancer immunotherapy, they activate tumour-infiltrating dendritic cells and reduce myeloid-derived suppressor cells, reprogramming the tumour microenvironment (Zhang et al., 2021). CpG ODN also shows promise in treating allergies and autoimmune diseases by shifting immune profiles from Th2 to Th1, benefiting asthma and similar conditions (Montamat et al., 2021).

3.3 Enterotoxin adjuvants

Enterotoxin adjuvants, derived from bacterial toxins like cholera toxin (CT) from Vibrio cholerae and heat-labile toxin (LT) from Escherichia coli, enhance mucosal immunity for oral, nasal, and intradermal vaccines. These adjuvants amplify systemic and mucosal immune responses, crucial for defending against infections in mucosal surfaces like the gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts (Crothers and Norton, 2023). Structurally, these adjuvants have an AB5 configuration: the A-subunit activates intracellular signalling, while the B-subunit binds ganglioside receptors like GM1, enabling antigen-presenting cell (APC) uptake (Valli et al., 2020). Within APCs, they stimulate cAMP pathways, promoting T-helper cell (Th1 and Th17) activation and antigen presentation. They also enhance germinal centre reactions, boosting high-affinity antibody production (Ma et al., 2024). Delivery route influences efficacy, with oral routes targeting gastrointestinal pathogens and nasal routes excelling for respiratory pathogens (Liang and Hajishengallis, 2010).

CT potently stimulates mucosal immunity, especially IgA, but its toxicity limits clinical use. Modified CT variants reduce toxicity while retaining efficacy. LT, structurally like CT, includes derivatives like double-mutant LT (dmLT), featuring mutations (R192G/L211A) that reduce toxicity while enhancing mucosal and systemic immunity (Toprani et al., 2017). dmLT supports vaccine development against E. coli, polio, and influenza. Innovative derivatives like LTA1 and CTA1 mitigate toxicity further (Stone et al., 2023). LTA1 enhances antigen uptake in nasal vaccines, while CTA1, conjugated to targeting motifs (e.g., CTA1-DD), promotes B-cell activation and antibody production (Lavelle and Ward, 2022). Detoxified variants like LTh(αK), which completely inhibit enzymatic activity, show promise in nasal influenza vaccines (Pan et al., 2019). Enterotoxin adjuvants are valuable for vaccines targeting mucosal pathogens (E. coli, Helicobacter pylori, V. cholerae), systemic infections, and emerging applications like HIV, influenza, and substance abuse prevention (Salvador-Erro et al., 2024; Yin et al., 2024).

3.4 β-glucans

β-Glucans are naturally occurring polysaccharides found in the cell walls of fungi, yeasts, bacteria, algae, and cereals like oats and barley. They are glucose polymers linked by β-(1→3) and β-(1→6) glycosidic bonds, with structural variations depending on their source (Liang et al., 2024). These variations significantly influence their biological functions, particularly their immunomodulatory properties, making them effective biological response modifiers (BRMs) and promising vaccine adjuvants (Abbasi et al., 2022). As adjuvants, β-glucans activate immune responses through interaction with pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) such as Dectin-1, complement receptor 3 (CR3), and scavenger receptors on immune cells, including dendritic cells, macrophages, and neutrophils. Binding to these receptors triggers key signalling pathways, such as NF-κB and MAPK, leading to immune activation, cytokine release, and enhanced phagocytosis (Jin et al., 2018). They also induce “trained immunity” by epigenetically reprogramming innate immune cells, enabling a stronger and more rapid response to infections and vaccinations. Moreover, β-glucans promote dendritic cell maturation, upregulating co-stimulatory molecules and MHC class II expression to improve T cell activation (Guo et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2024b). They activate the complement system, enhancing pathogen clearance and supporting immune cell phagocytosis. By fostering Th1 and Th17 immune responses through cytokines like IL-12 and IL-6, β-glucans are crucial for combating intracellular pathogens and tumours (Cognigni et al., 2021; Córdova-Martínez et al., 2021).

The source and structural diversity of β-glucans define their specific activities. Fungal β-glucans, such as those from Lentinula edodes and Ganoderma lucidum, feature β-(1→3) backbones with β-(1→6) branches, excelling as immunomodulators in cancer and infectious disease therapies (Steimbach et al., 2021). Yeast β-glucans (e.g., Saccharomyces cerevisiae) are highly branched, activating Dectin-1 and CR3 to boost macrophage and neutrophil activity, with FDA-approved uses as dietary supplements and adjuvants (Azevedo-Silva et al., 2024). Cereal β-glucans (oats, barley), composed of β-(1→3) and β-(1→4) linkages, are effective in metabolic regulation and show potential as oral vaccine adjuvants. Algal β-glucans, primarily β-(1→3)-linked, have emerging roles in marine immunity and food science (Barsanti and Gualtieri, 2023).

3.5 Dimethyldioctadecylammonium bromide with saponin

The combination of Dimethyldioctadecylammonium bromide (DDA) and saponin enhances humoral and cellular immune responses in advanced vaccine formulations. DDA, a synthetic cationic lipid often delivered as liposomes, and saponin, a natural surfactant from Quillaja saponaria, possess complementary properties for mucosal and systemic vaccine delivery. Together, they underpin cationic adjuvant formulations (CAF) and immunostimulating complexes (ISCOMs), critical in next-generation vaccine development (Correa et al., 2022a). DDA binds negatively charged antigens via charge-based interactions, improving antigen stability and delivery to APCs. Its particle size (∼40–200 nm) promotes lymphatic uptake, while stimulating Th1-biased cytokines like interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and interleukin-12 (IL-12), essential for intracellular pathogen defence and tumour immunity (Qu et al., 2018).

Saponin enhances immunogenicity by disrupting membranes, facilitating antigen entry into APCs and inflammasome activation. It boosts Th2 and Th17 cytokines like IL-4 and IL-17, vital for extracellular pathogen and mucosal immunity. By promoting antigen presentation via MHC class II, it strengthens T-helper and B-cell activation, increasing antibody titters and avidity (den Brok et al., 2016; Marciani, 2018). The DDA-saponin combination delivers a balanced Th1/Th2 response, enhancing IgG titters, antigen recognition, and long-term memory. It supports diverse applications, including meningococcal vaccines, where it raises bactericidal antibody levels against Neisseria meningitidis. In cancer immunotherapy, DDA’s Th1 polarization drives cytotoxic T-cell responses, making this adjuvant pair a promising strategy for therapeutic cancer vaccines (Yu et al., 2010; Vishwakarma et al., 2024).

3.6 Polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid

Poly(I:C), a synthetic double-stranded RNA analogue, mimics viral replication intermediates and acts as a potent immunostimulant. It enhances both innate and adaptive immunity, making it a promising adjuvant for cancer immunotherapy and vaccine development. Poly(I:C) activates pattern recognition receptors like Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) and melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (MDA-5) (Martins et al., 2015).

In dendritic cells and macrophages, Poly(I:C) binds TLR3 in endosomes, triggering the TRIF pathway. This induces type I interferons (IFN-α/β) and pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α. In the cytoplasm, it engages MDA-5 and RIG-I, activating transcription factors such as IRF3 and NF-κB. These pathways promote dendritic cell maturation, enhancing MHC expression, co-stimulatory markers, and T-cell activation (Kester and Bortz, 2018). Poly(I:C) indirectly boosts NK cell cytotoxicity via IL-12 and IFN-γ, fostering a Th1-biased response critical for CTL activation and tumour elimination (Ball et al., 2024). Additionally, Poly(I:C) directly induces tumour cell apoptosis by activating TLR3, triggering caspase-dependent mechanisms and reducing anti-apoptotic molecules like survivin. This apoptosis releases tumour antigens, enhancing APC uptake and cross-presentation, leading to robust CD8+ T-cell priming (Zhu et al., 2015; Ko et al., 2023).

Poly(I:C) is versatile, functioning in peptide-, protein-, and cell-based vaccines. It synergizes with adjuvants like CpG ODNs and anti-CD40 antibodies, enhancing immune responses (Gupta et al., 2016). In cancer immunotherapy, it amplifies antigen-specific CTL and NK cell responses, showing potential in combination with tumour-associated antigens and immune checkpoint inhibitors (Aznar et al., 2019; Akache et al., 2021). For infectious diseases, it bolsters vaccine immunogenicity against viral and intracellular pathogens, making it valuable in both prophylactic and therapeutic vaccine strategies (Bardel et al., 2016; Bruun et al., 2024; Yao et al., 2024).

3.7 STING agonists

STING (Stimulator of Interferon Genes) agonists are agents that activate the STING pathway, a key element of the innate immune system. This pathway responds to cytosolic DNA by producing cyclic dinucleotides (CDNs), which stimulate robust production of type I interferons and pro-inflammatory cytokines (Gajewski and Higgs, 2020). STING agonists, either small molecules or biologically derived, are integral to enhancing cancer immunotherapy and vaccine efficacy (Le Naour et al., 2020). Located in the endoplasmic reticulum, STING is activated when CDNs like cGAMP bind to it. These CDNs are either endogenously synthesized by cGAS (cyclic GMP-AMP synthase) or delivered exogenously through STING agonists. Activation prompts STING to translocate to the Golgi, where it initiates IRF3 and NF-κB signalling pathways. This induces the expression of type I interferons (e.g., IFN-β) and inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6), amplifying immune responses (Ohkuri et al., 2018; Van Herck et al., 2021).

STING agonists enhance antigen presentation by maturing APCs like dendritic cells, boosting their ability to activate T cells. This primes adaptive immune responses, especially against tumour-associated antigens (TAAs). They also modulate the tumour microenvironment, shifting it from immunosuppressive to immunostimulatory, promoting cytotoxic T-cell infiltration and activity (Xuan and Hu, 2023). These effects are critical for overcoming tumour-induced immune evasion. Two primary types of STING agonists exist. Cyclic dinucleotides (CDNs) include natural molecules like cGAMP and synthetic versions such as 2′3′-cGAMP, which are optimized for stability and bioavailability (Dubensky et al., 2013). Non-nucleotide agonists, small molecules that activate STING without mimicking CDNs, offer advantages in synthesis, stability, and delivery (Wang et al., 2021). Applications include cancer immunotherapy, where STING agonists synergize with immune checkpoint inhibitors (e.g., anti-PD-1, anti-CTLA-4) to enhance T-cell activation and counter tumour immunosuppression (Nicolai et al., 2020; Da et al., 2022). Intratumoral delivery can trigger systemic antitumor responses, including the abscopal effect. In vaccines, STING agonists enhance immune responses by promoting dendritic cell maturation and activation of B and T cells (Wang et al., 2024a). Combination therapies, integrating STING agonists with adjuvants like CpG ODNs or treatments such as chemotherapy and radiation, further amplify their immunostimulatory effects (Vasiyani et al., 2023; Eiro et al., 2024; Khalifa et al., 2024).

3.8 Microtubule-targeting agents

Microtubule-targeting agents (MTAs) are compounds that disrupt microtubule dynamics, essential for intracellular transport, mitosis, and cellular signalling. Traditionally utilized in chemotherapy for their ability to inhibit tumour cell division, recent research highlights their immunomodulatory potential, making them promising adjuvants for cancer immunotherapy and vaccines (Wordeman and Vicente, 2021). MTAs, including 4H-chromene-3-carbonitrile derivatives, inhibit tubulin polymerization, disrupting mitosis and intracellular trafficking. This disruption induces mitochondrial depolarization, activating pathways such as the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade, which drives immune activation (Steinmetz and Prota, 2018). Furthermore, MTAs prolong NF-κB pathway activation, enhancing APC function and pro-inflammatory cytokine production. These effects amplify immune responses, with MAPK signalling fostering cytokine and chemokine production to recruit and activate immune cells. MTAs also promote dendritic cell maturation and cytokine secretion (e.g., IL-12, IL-6, TNF-α), which are crucial for effective antigen presentation and T-cell priming (Serpico et al., 2020).

MTAs’ dual antitumor and immune activation properties make them valuable in cancer immunotherapy, combining cytotoxicity with stimulation of innate and adaptive immunity. By sustaining NF-κB signalling, MTAs ensure prolonged immune activation and synergize with immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as anti-PD-1 antibodies, to enhance antitumor responses. This combination induces systemic effects, including the abscopal effect, where tumours at untreated sites regress. Additionally, MTAs selectively modulate cytokine production (e.g., IL-12, IL-6, IL-1β), driving Th1-biased responses critical for antitumor immunity and intracellular pathogen defence (Sato-Kaneko et al., 2018). Clinically, MTAs are used with immune checkpoint inhibitors to boost antitumor immunity, as seen with intratumoral 4H-chromene-3-carbonitrile derivatives in murine cancer models, which slow tumour growth and activate systemic immunity (Wang et al., 2023). MTAs also enhance cancer vaccines by improving antigen presentation and T-cell activation, making them strong candidates for next-generation vaccines. In combination therapies, MTAs are paired with chemotherapeutics or other adjuvants to enhance treatment efficacy while leveraging their immunostimulatory effects (Liang et al., 2022).

4 Challenges and future directions

Emerging adjuvants discussed herein offer immense potential to transform immunotherapy and vaccine development, but their advancement is constrained by several challenges that require careful consideration. Among the foremost concerns is the issue of safety and tolerability. Many next-generation adjuvants, such as STING agonists and poly(I:C), are designed to induce potent immune responses, yet their high immunostimulatory capacity can lead to unintended side effects (De Waele et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2023). Excessive activation of the immune system can result in systemic inflammation, cytokine storms, or localized reactogenicity, including significant pain, swelling, or erythema at the injection site (Karki and Kanneganti, 2021). These adverse effects limit their clinical applicability and necessitate the development of strategies to balance efficacy with safety. Future efforts must focus on refining the formulations of adjuvants to modulate their activity and targeting. Delivery platforms such as nanoparticles, liposomes, or hydrogels are promising approaches to localize the action of adjuvants, reduce systemic exposure, and minimize off-target effects while maintaining their immunostimulatory potential (Desai et al., 2023).

Another major hurdle is the instability and scalability of many emerging adjuvants. Complex molecules like ARNAX or synthetic cyclic dinucleotides used in STING agonists often exhibit poor stability in physiological conditions, with short half-lives that limit their therapeutic efficacy (Boehm et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2023). Furthermore, the intricate manufacturing processes required to produce these agents contribute to high production costs and hinder their scalability for widespread clinical use (Kis et al., 2019). Stabilization techniques, such as encapsulating adjuvants in biodegradable polymers or using modified molecular analogues, are critical for addressing these issues (Yenkoidiok-Douti and Jewell, 2020; Freire Haddad et al., 2023). Simplifying production workflows and developing cost-effective methodologies will also be necessary to ensure the large-scale deployment of these advanced adjuvants, particularly in resource-limited settings where affordability and accessibility are paramount.

Population-specific variability in immune responses presents an additional challenge in the clinical implementation of emerging adjuvants. Differences in genetic backgrounds, age, sex, and environmental factors significantly influence how individuals respond to adjuvants (Sanz et al., 2018). For instance, polymorphisms in genes encoding receptors such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) or the STING protein can alter the efficacy and safety profiles of these agents. This variability complicates the design of adjuvants capable of eliciting consistent immune responses across diverse populations (Medvedev, 2013). Addressing this challenge requires a personalized approach to adjuvant development, incorporating insights from genomics, proteomics, and immunoprofiling (Bravi, 2024; Kumar et al., 2024). Future research should aim to identify biomarkers that predict individual responsiveness to specific adjuvants, enabling the design of tailored formulations optimized for distinct patient groups or populations.

The integration of adjuvants into combination therapies, particularly in cancer immunotherapy, introduces additional complexities. While combining adjuvants with immune checkpoint inhibitors or monoclonal antibodies holds promise for synergistic effects, it also increases the risk of adverse interactions and unpredictable immune dynamics (Seliger, 2019). These interactions can result in overactivation of the immune system or heightened toxicity. To address this, preclinical studies and clinical trials must rigorously evaluate the compatibility of adjuvants with other therapeutic agents. Developing standardized protocols for co-administration and optimizing the timing and dosing of combined treatments will be essential to harness their full therapeutic potential while minimizing risks (Desai et al., 2024b). Regulatory and ethical challenges further complicate the translation of novel adjuvants from research to clinical application. The stringent safety requirements imposed by regulatory agencies, while necessary, often result in lengthy and costly approval processes (Sun et al., 2012). Additionally, ethical concerns surrounding the testing of potent adjuvants in vulnerable populations, such as children, the elderly, or immunocompromised individuals, add layers of complexity (Rajani et al., 2022; Salave et al., 2023). Collaborative efforts between regulatory bodies, researchers, and industry stakeholders will be essential to streamline these pathways while maintaining rigorous safety and efficacy standards. The development of advanced preclinical models, including organ-on-chip systems and computational simulations, can provide more accurate predictions of clinical outcomes, reducing the risks associated with early-stage testing (Sunita et al., 2020; Rajpoot et al., 2022; Cook et al., 2025).

Despite these challenges, the future of adjuvant technology is promising. Continued investment in fundamental research to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying adjuvant activity will be critical for designing safer and more effective agents. Technologies such as single-cell sequencing, proteomics, and artificial intelligence can accelerate the discovery and optimization of novel adjuvants by providing deeper insights into immune modulation at the cellular and molecular levels (Noé et al., 2020; Shenoy et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2023; Li et al., 2023). Additionally, expanding the scope of adjuvant applications beyond traditional immunotherapy to areas such as neuroinflammation, autoimmune diseases, and metabolic disorders could unlock new therapeutic opportunities.

Global accessibility remains an overarching challenge that must be addressed to ensure the equitable distribution of next-generation adjuvants. The high costs and technical complexities associated with their production and distribution disproportionately affect low- and middle-income countries, where the need for affordable vaccines and immunotherapies is greatest (Mahoney et al., 2023). Addressing this requires the development of cost-effective formulations, scalable production techniques, and international collaborations to ensure these advances benefit all populations, regardless of geographic or economic constraints (Kozak and Hu, 2023; Yemeke et al., 2023).

5 Discussion

The integration of adjuvants into immunotherapy and vaccine development has long been recognized as a critical factor in overcoming the inherent limitations of antigens in eliciting robust immune responses. This review has highlighted the transformative potential of emerging adjuvants, including ARNAX, CpG ODNs, STING agonists, synthetic double-stranded RNA like poly(I:C), beta-glucan derivatives, and microtubule-targeting agents. Unlike traditional adjuvants, which are often limited by poor specificity, safety concerns, and suboptimal immune polarization, these next-generation agents leverage precise molecular mechanisms to enhance immune activation. By targeting specific pathways such as TLR3, TLR9, and the STING pathway, these adjuvants have demonstrated their ability to amplify antigen presentation, promote Th1 and Th17 responses, and induce long-lasting immunological memory. Their ability to complement and synergize with other immunotherapeutic agents, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors, further underscores their importance in modern medical strategies.

The adjuvants discussed in this review represent a significant leap forward, but their full potential remains untapped. Advances in molecular and cellular biology, nanotechnology, and computational modelling offer exciting opportunities to refine these agents further. For example, personalized adjuvant designs tailored to individual genetic or immunological profiles could revolutionize the way we approach precision medicine. Furthermore, the development of adjuvants that are compatible with non-traditional delivery platforms, such as intranasal, oral, or transdermal routes, could open new doors for vaccine and immunotherapy applications. Adjuvants designed for targeted delivery using nanoparticles or ligand-conjugated systems can enhance specificity while reducing systemic toxicity. Beyond their established roles in cancer and infectious disease vaccines, future applications may include conditions such as neuroinflammation, autoimmune diseases, and even metabolic disorders, where modulation of immune activity is increasingly recognized as a therapeutic strategy. The role of artificial intelligence and machine learning in accelerating adjuvant discovery and optimization is another frontier that holds great promise.

Next-generation adjuvants signify a pivotal advancement in the evolution of immunotherapy and vaccine development. Their capacity to precisely modulate immune responses, enhance therapeutic efficacy, and overcome the limitations of traditional approaches positions them as indispensable tools in modern medicine. Despite the challenges of safety, scalability, and regulatory approval, the continuous refinement of these agents through interdisciplinary efforts is expected to address these hurdles. The future of immunotherapy lies in the seamless integration of these adjuvants into therapeutic strategies, creating more effective, accessible, and patient-centric solutions.

Statements

Author contributions

ND: Conceptualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. SG: Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. SS: Writing–review and editing. LV: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Abbasi A. Rahbar Saadat T. Rahbar Saadat Y. (2022). Microbial exopolysaccharides–β-glucans–as promising postbiotic candidates in vaccine adjuvants. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.223, 346–361. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.11.003

2

Akache B. Agbayani G. Stark F. C. Jia Y. Dudani R. Harrison B. A. et al (2021). Sulfated lactosyl archaeol archaeosomes synergize with poly(I: C) to enhance the immunogenicity and efficacy of a synthetic long peptide-based vaccine in a melanoma tumor model. Pharmaceutics13, 257. 10.3390/pharmaceutics13020257

3

Awate S. Babiuk L. A. Mutwiri G. (2013). Mechanisms of action of adjuvants. Front. Immunol4, 114. 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00114

4

Azevedo-Silva J. Amorim M. Tavares-Valente D. Sousa P. Mohamath R. Voigt E. A. et al (2024). Exploring yeast glucans for vaccine enhancement: sustainable strategies for overcoming adjuvant challenges in a SARS-CoV-2 model. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm.205, 114538. 10.1016/j.ejpb.2024.114538

5

Aznar M. A. Planelles L. Perez-Olivares M. Molina C. Garasa S. Etxeberría I. et al (2019). Immunotherapeutic effects of intratumoral nanoplexed poly I: C. J. Immunother. Cancer7, 116. 10.1186/s40425-019-0568-2

6

Ball A. G. Morgaenko K. Anbaei P. Ewald S. E. Pompano R. R. (2024). Poly I: C vaccination drives transient CXCL9 expression near B cell follicles in the lymph node through type-I and type-II interferon signaling. Cytokine183, 156731. 10.1016/j.cyto.2024.156731

7

Bardel E. Doucet-Ladeveze R. Mathieu C. Harandi A. M. Dubois B. Kaiserlian D. (2016). Intradermal immunisation using the TLR3-ligand Poly (I: C) as adjuvant induces mucosal antibody responses and protects against genital HSV-2 infection. NPJ Vaccines1, 16010. 10.1038/npjvaccines.2016.10

8

Barsanti L. Gualtieri P. (2023). Glucans, paramylon and other algae bioactive molecules. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24, 5844. 10.3390/ijms24065844

9

Boehm D. T. Mizuno N. Pryke K. DeFilippis V. (2021). Divergent immune impacts elicited by chemically dissimilar agonists of the STING protein. J. Immunol.206, 102.04. 10.4049/jimmunol.206.Supp.102.04

10

Bravi B. (2024). Development and use of machine learning algorithms in vaccine target selection. NPJ Vaccines9, 15. 10.1038/s41541-023-00795-8

11

Bruun N. Laursen M. F. Carmelo R. Christensen E. Jensen T. S. Christiansen G. et al (2024). Novel nucleotide-packaging vaccine delivers antigen and poly(I: C) to dendritic cells and generate a potent antibody response in vivo. Vaccine42, 2909–2918. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2024.03.058

12

Castro Eiro M. D. Hioki K. Li L. Wilmsen M. E. P. Kiernan C. H. Brouwers-Haspels I. et al (2024). TLR9 plus STING agonist adjuvant combination induces potent neopeptide T cell immunity and improves immune checkpoint blockade efficacy in a tumor model. J. Immunol.212, 455–465. 10.4049/jimmunol.2300038

13

Chasov V. Zmievskaya E. Ganeeva I. Gilyazova E. Davletshin D. Khaliulin M. et al (2024). Immunotherapy strategy for systemic autoimmune diseases: betting on CAR-T cells and antibodies. Antibodies13, 10. 10.3390/antib13010010

14

Cognigni V. Ranallo N. Tronconi F. Morgese F. Berardi R. (2021). Potential benefit of β-glucans as adjuvant therapy in immuno-oncology: a review. Explor Target Antitumor Ther.2, 122–138. 10.37349/etat.2021.00036

15

Cook S. R. Ball A. G. Mohammad A. Pompano R. R. (2025). A 3D-printed multi-compartment organ-on-chip platform with a tubing-free pump models communication with the lymph node. Lab. Chip25, 155–174. 10.1039/D4LC00489B

16

Córdova-Martínez A. Caballero-García A. Roche E. Noriega D. C. (2021). β-Glucans could Be adjuvants for SARS-CoV-2 virus vaccines (COVID-19). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health18, 12636. 10.3390/ijerph182312636

17

Correa V. A. Portilho A. I. De Gaspari E. (2022a). Immunological effects of Dimethyldioctadecylammonium bromide and saponin as adjuvants for outer membrane vesicles from Neisseria meningitidis. Diseases10, 46. 10.3390/diseases10030046

18

Correa V. A. Portilho A. I. De Gaspari E. (2022b). Vaccines, adjuvants and key factors for mucosal immune response. Immunology167, 124–138. 10.1111/imm.13526

19

Crothers J. W. Norton E. B. (2023). Recent advances in enterotoxin vaccine adjuvants. Curr. Opin. Immunol.85, 102398. 10.1016/j.coi.2023.102398

20

Da Y. Liu Y. Hu Y. Liu W. Ma J. Lu N. et al (2022). STING agonist cGAMP enhances anti-tumor activity of CAR-NK cells against pancreatic cancer. Oncoimmunology11, 2054105. 10.1080/2162402X.2022.2054105

21

Dagher O. K. Schwab R. D. Brookens S. K. Posey A. D. (2023). Advances in cancer immunotherapies. Cell186, 1814–1814.e1. 10.1016/j.cell.2023.02.039

22

den Brok M. H. Büll C. Wassink M. de Graaf A. M. Wagenaars J. A. Minderman M. et al (2016). Saponin-based adjuvants induce cross-presentation in dendritic cells by intracellular lipid body formation. Nat. Commun.7, 13324. 10.1038/ncomms13324

23

Desai N. Chavda V. Singh T. R. R. Thorat N. D. Vora L. K. (2024a). Cancer nanovaccines: nanomaterials and clinical perspectives. Small20, e2401631. 10.1002/smll.202401631

24

Desai N. Hasan U. K. J. Mani R. Chauhan M. Basu S. M. et al (2023). Biomaterial-based platforms for modulating immune components against cancer and cancer stem cells. Acta Biomater.161, 1–36. 10.1016/j.actbio.2023.03.004

25

Desai N. Pande S. Gholap A. D. Rana D. Salave S. Vora L. K. (2024b). “Regulatory processes involved in clinical trials and intellectual property rights around vaccine development,” in Advanced Vaccination Technologies for Infectious and Chronic Diseases. Elsevier, 279–309. 10.1016/B978-0-443-18564-9.00008-4

26

De Waele J. Verhezen T. van der Heijden S. Berneman Z. N. Peeters M. Lardon F. et al (2021). A systematic review on poly(I: C) and poly-ICLC in glioblastoma: adjuvants coordinating the unlocking of immunotherapy. J. Exp. and Clin. Cancer Res.40, 213. 10.1186/s13046-021-02017-2

27

Dubensky T. W. Kanne D. B. Leong M. L. (2013). Rationale, progress and development of vaccines utilizing STING-activating cyclic dinucleotide adjuvants. Ther. Adv. Vaccines1, 131–143. 10.1177/2051013613501988

28

Facciolà A. Visalli G. Laganà A. Di Pietro A. (2022). An overview of vaccine adjuvants: current evidence and future perspectives. Vaccines (Basel)10, 819. 10.3390/vaccines10050819

29

Freire Haddad H. Roe E. F. Collier J. H. (2023). Expanding opportunities to engineer mucosal vaccination with biomaterials. Biomater. Sci.11, 1625–1647. 10.1039/D2BM01694J

30

Gajewski T. F. Higgs E. F. (2020). Immunotherapy with a sting. Sci. (1979)369, 921–922. 10.1126/science.abc6622

31

Givens B. E. Geary S. M. Salem A. K. (2018). Nanoparticle-based cpg-oligonucleotide therapy for treating allergic asthma. Immunotherapy10, 595–604. 10.2217/imt-2017-0142

32

Guo W. Zhang X. Wan L. Wang Z. Han M. Yan Z. et al (2024). β-Glucan-modified nanoparticles with different particle sizes exhibit different lymphatic targeting efficiencies and adjuvant effects. J. Pharm. Anal.14, 100953. 10.1016/j.jpha.2024.02.007

33

Gupta S. K. Tiwari A. K. Gandham R. K. Sahoo A. P. (2016). Combined administration of the apoptin gene and poly (I: C) induces potent anti-tumor immune response and inhibits growth of mouse mammary tumors. Int. Immunopharmacol.35, 163–173. 10.1016/j.intimp.2016.03.034

34

Hartmann G. (2023). Cooperative activation of human TLR9 and consequences for the clinical development of antisense and CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids34, 102078. 10.1016/j.omtn.2023.102078

35

Jelinek I. Leonard J. N. Price G. E. Brown K. N. Meyer-Manlapat A. Goldsmith P. K. et al (2011). TLR3-Specific double-stranded RNA oligonucleotide adjuvants induce dendritic cell cross-presentation, CTL responses, and antiviral protection. J. Immunol.186, 2422–2429. 10.4049/jimmunol.1002845

36

Jin Y. Li P. Wang F. (2018). β-glucans as potential immunoadjuvants: a review on the adjuvanticity, structure-activity relationship and receptor recognition properties. Vaccine36, 5235–5244. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.07.038

37

Karki R. Kanneganti T.-D. (2021). The ‘cytokine storm’: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic prospects. Trends Immunol.42, 681–705. 10.1016/j.it.2021.06.001

38

Kayraklioglu N. Horuluoglu B. Klinman D. M. (2021). CpG oligonucleotides as vaccine adjuvants. Methods Mol. Biol.2197, 51–85. 10.1007/978-1-0716-0872-2_4

39

Kester J. M. Bortz E. (2018). Interferon regulatory factor 3 and NF kappa b are required for expression of immune susceptibility genes in human lung and breast carcinoma cells treated with poly I: C. FASEB J.32. 10.1096/fasebj.2018.32.1_supplement.lb671

40

Khalifa A. M. Nakamura T. Sato Y. Harashima H. (2024). Vaccination with a combination of STING agonist-loaded lipid nanoparticles and CpG-ODNs protects against lung metastasis via the induction of CD11bhighCD27low memory-like NK cells. Exp. Hematol. Oncol.13, 36. 10.1186/s40164-024-00502-w

41

Kim J. Y. Rosenberger M. G. Rutledge N. S. Esser-Kahn A. P. (2023). Next-generation adjuvants: applying engineering methods to create and evaluate novel immunological responses. Pharmaceutics15, 1687. 10.3390/pharmaceutics15061687

42

Kis Z. Shattock R. Shah N. Kontoravdi C. (2019). Emerging technologies for low-cost, rapid vaccine manufacture. Biotechnol. J.14, e1800376. 10.1002/biot.201800376

43

Ko E.-J. Kang S.-M. (2018). Immunology and efficacy of MF59-adjuvanted vaccines. Hum. Vaccin Immunother.14, 3041–3045. 10.1080/21645515.2018.1495301

44

Ko K. H. Cha S. B. Lee S.-H. Bae H. S. Ham C. S. Lee M.-G. et al (2023). A novel defined TLR3 agonist as an effective vaccine adjuvant. Front. Immunol.14, 1075291. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1075291

45

Kozak M. Hu J. (2023). The integrated consideration of vaccine platforms, adjuvants, and delivery routes for successful vaccine development. Vaccines (Basel)11, 695. 10.3390/vaccines11030695

46

Kumar A. Dixit S. Srinivasan K. M. D. Vincent P. M. D. R. (2024). Personalized cancer vaccine design using AI-powered technologies. Front. Immunol.15, 1357217. 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1357217

47

Lavelle E. C. McEntee C. P. (2024). Vaccine adjuvants: tailoring innate recognition to send the right message. Immunity57, 772–789. 10.1016/j.immuni.2024.03.015

48

Lavelle E. C. Ward R. W. (2022). Mucosal vaccines — fortifying the frontiers. Nat. Rev. Immunol.22, 236–250. 10.1038/s41577-021-00583-2

49

Lee G.-H. Lim S.-G. (2021). CpG-adjuvanted hepatitis B vaccine (HEPLISAV-B®) update. Expert Rev. Vaccines20, 487–495. 10.1080/14760584.2021.1908133

50

Le Naour J. Zitvogel L. Galluzzi L. Vacchelli E. Kroemer G. (2020). Trial watch: STING agonists in cancer therapy. Oncoimmunology9, 1777624. 10.1080/2162402X.2020.1777624

51

Li Y. Li Z. Chen X. (2023). Comparative tissue proteomics reveals unique action mechanisms of vaccine adjuvants. iScience26, 105800. 10.1016/j.isci.2022.105800

52

Liang S. Hajishengallis G. (2010). Heat-labile enterotoxins as adjuvants or anti-inflammatory agents. Immunol. Invest39, 449–467. 10.3109/08820130903563998

53

Liang T. Lu L. Song X. Qi J. Wang J. (2022). Combination of microtubule targeting agents with other antineoplastics for cancer treatment. Biochimica Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Rev. Cancer1877, 188777. 10.1016/j.bbcan.2022.188777

54

Liang X. Zhou J. Wang M. Wang J. Song H. Xu Y. et al (2024). Progress and prospect of polysaccharides as adjuvants in vaccine development. Virulence15, 2435373. 10.1080/21505594.2024.2435373

55

Lykins W. R. Fox C. B. (2023). Practical considerations for next-generation adjuvant development and translation. Pharmaceutics15, 1850. 10.3390/pharmaceutics15071850

56

Ma J. Hermans L. Dierick M. Van der Weken H. Cox E. Devriendt B. (2024). Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli heat labile enterotoxin affects neutrophil effector functions via cAMP/PKA/ERK signaling. Gut Microbes16, 2399215. 10.1080/19490976.2024.2399215

57

Mahoney R. Hotez P. J. Bottazzi M. E. (2023). Global regulatory reforms to promote equitable vaccine access in the next pandemic. PLOS Glob. Public Health3, e0002482. 10.1371/journal.pgph.0002482

58

Marciani D. J. (2018). Elucidating the mechanisms of action of saponin-derived adjuvants. Trends Pharmacol. Sci.39, 573–585. 10.1016/j.tips.2018.03.005

59

Martins K. A. Bavari S. Salazar A. M. (2015). Vaccine adjuvant uses of poly-IC and derivatives. Expert Rev. Vaccines14, 447–459. 10.1586/14760584.2015.966085

60

Matsuda M. Mochizuki S. (2023). Control of A/D type CpG-ODN aggregates to a suitable size for induction of strong immunostimulant activity. Biochem. Biophys. Rep.36, 101573. 10.1016/j.bbrep.2023.101573

61

Matsumoto M. Takeda Y. Seya T. (2020). Targeting Toll-like receptor 3 in dendritic cells for cancer immunotherapy. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther.20, 937–946. 10.1080/14712598.2020.1749260

62

Matsumoto M. Tatematsu M. Nishikawa F. Azuma M. Ishii N. Morii-Sakai A. et al (2015). Defined TLR3-specific adjuvant that induces NK and CTL activation without significant cytokine production in vivo. Nat. Commun.6, 6280. 10.1038/ncomms7280

63

McKee A. S. Marrack P. (2017). Old and new adjuvants. Curr. Opin. Immunol.47, 44–51. 10.1016/j.coi.2017.06.005

64

Medvedev A. E. (2013). Toll-like receptor polymorphisms, inflammatory and infectious diseases, allergies, and cancer. J. Interferon and Cytokine Res.33, 467–484. 10.1089/jir.2012.0140

65

Miyazaki A. Yoshida S. Takeda Y. Tomaru U. Matsumoto M. Seya T. (2025). Th1 adjuvant ARNAX, in combination with radiation therapy, enhances tumor regression in mouse tumor-implant models. Immunol. Lett.271, 106947. 10.1016/j.imlet.2024.106947

66

Moni S. Abdelwahab S. Jabeen A. Elmobark M. Aqaili D. Gohal G. et al (2023). Advancements in vaccine adjuvants: the journey from alum to nano formulations. Vaccines (Basel)11, 1704. 10.3390/vaccines11111704

67

Montamat G. Leonard C. Poli A. Klimek L. Ollert M. (2021). CpG adjuvant in allergen-specific immunotherapy: finding the sweet spot for the induction of immune tolerance. Front. Immunol. 1212, 590054. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.590054

68

Muranishi K. Kinoshita M. Inoue K. Ohara J. Mihara T. Sudo K. et al (2023). Antibody response following the intranasal administration of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein-CpG oligonucleotide vaccine. Vaccines (Basel)12, 5. 10.3390/vaccines12010005

69

Nicolai C. J. Wolf N. Chang I.-C. Kirn G. Marcus A. Ndubaku C. O. et al (2020). NK cells mediate clearance of CD8 + T cell–resistant tumors in response to STING agonists. Sci. Immunol.5, eaaz2738. 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaz2738

70

Noé A. Cargill T. N. Nielsen C. M. Russell A. J. C. Barnes E. (2020). The application of single-cell RNA sequencing in vaccinology. J. Immunol. Res.2020, 1–19. 10.1155/2020/8624963

71

O’Hagan D. T. Lodaya R. N. Lofano G. (2020). The continued advance of vaccine adjuvants – ‘we can work it out.’. Semin. Immunol.50, 101426. 10.1016/j.smim.2020.101426

72

Ohkuri T. Kosaka A. Nagato T. Kobayashi H. (2018). Effects of STING stimulation on macrophages: STING agonists polarize into “classically” or “alternatively” activated macrophages?Hum. Vaccin Immunother.14, 285–287. 10.1080/21645515.2017.1395995

73

Pan S.-C. Hsieh S.-M. Lin C.-F. Hsu Y.-S. Chang M. Chang S.-C. (2019). A randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial to evaluate the safety and immunogenicity of an intranasally administered trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine with adjuvant LTh(αK): A phase I study. Vaccine37, 1994–2003. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.02.006

74

Pulendran B. S. Arunachalam P. O’Hagan D. T. (2021). Emerging concepts in the science of vaccine adjuvants. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov.20, 454–475. 10.1038/s41573-021-00163-y

75

Qi Y. Fox C. B. (2021). Development of thermostable vaccine adjuvants. Expert Rev. Vaccines20, 497–517. 10.1080/14760584.2021.1902314

76

Qu W. Li N. Yu R. Zuo W. Fu T. Fei W. et al (2018). Cationic DDA/TDB liposome as a mucosal vaccine adjuvant for uptake by dendritic cells in vitro induces potent humoural immunity. Artif. Cells Nanomed Biotechnol.46, 852–860. 10.1080/21691401.2018.1438450

77

Rajani C. Borisa P. Bagul S. Shukla K. Tambe V. Desai N. et al (2022). “Developmental toxicity of nanomaterials used in drug delivery: understanding molecular biomechanics and potential remedial measures,” in Pharmacokinetics and Toxicokinetic Considerations. Elsevier, 685–725. 10.1016/B978-0-323-98367-9.00017-2

78

Rajpoot K. Desai N. Koppisetti H. Tekade M. Sharma M. C. Behera S. K. et al (2022). “In silico methods for the prediction of drug toxicity,” in Pharmacokinetics and Toxicokinetic Considerations. Elsevier, 357–383. 10.1016/B978-0-323-98367-9.00012-3

79

Roman F. Burny W. Ceregido M. A. Laupèze B. Temmerman S. T. Warter L. et al (2024). Adjuvant system AS01: from mode of action to effective vaccines. Expert Rev. Vaccines23, 715–729. 10.1080/14760584.2024.2382725

80

Salave S. Patel P. Desai N. Rana D. Benival D. Khunt D. et al (2023). Recent advances in dosage form design for the elderly: a review. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv.20, 1553–1571. 10.1080/17425247.2023.2286368

81

Salvador-Erro J. Pastor Y. Gamazo C. (2024). A recombinant Shigella flexneri strain expressing ETEC heat-labile enterotoxin B subunit shows promise for vaccine development via OMVs. Int. J. Mol. Sci.25, 12535. 10.3390/ijms252312535

82

Sanz J. Randolph H. E. Barreiro L. B. (2018). Genetic and evolutionary determinants of human population variation in immune responses. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev.53, 28–35. 10.1016/j.gde.2018.06.009

83

Sarkar I. Garg R. van Drunen Littel-van den Hurk S. (2019). Selection of adjuvants for vaccines targeting specific pathogens. Expert Rev. Vaccines18, 505–521. 10.1080/14760584.2019.1604231

84

Sato-Kaneko F. Wang X. Yao S. Hosoya T. Lao F. S. Messer K. et al (2018). Discovery of a novel microtubule targeting agent as an adjuvant for cancer immunotherapy. Biomed. Res. Int.2018, 1–13. 10.1155/2018/8091283

85

Schijns V. Fernández-Tejada A. Barjaktarović Ž. Bouzalas I. Brimnes J. Chernysh S. et al (2020). Modulation of immune responses using adjuvants to facilitate therapeutic vaccination. Immunol. Rev.296, 169–190. 10.1111/imr.12889

86

Seliger B. (2019). Combinatorial approaches with checkpoint inhibitors to enhance anti-tumor immunity. Front. Immunol. 1010, 999. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00999

87

Serpico A. F. Visconti R. Grieco D. (2020). Exploiting immune-dependent effects of microtubule-targeting agents to improve efficacy and tolerability of cancer treatment. Cell Death Dis.11, 361. 10.1038/s41419-020-2567-0

88

Seya T. Shingai M. Kawakita T. Matsumoto M. (2023). Two modes of Th1 polarization induced by dendritic-cell-priming adjuvant in vaccination. Cells12, 1504. 10.3390/cells12111504

89

Seya T. Takeda Y. Matsumoto M. (2019). A Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) agonist ARNAX for therapeutic immunotherapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev.147, 37–43. 10.1016/j.addr.2019.07.008

90

Seya T. Tatematsu M. Matsumoto M. (2022). Toward establishing an ideal adjuvant for non-inflammatory immune enhancement. Cells11, 4006. 10.3390/cells11244006

91

Shenoy S. Sanap G. Paul D. Desai N. Tambe V. Kalyane D. et al (2021). “Artificial intelligence in preventive and managed healthcare,” in Biopharmaceutics and Pharmacokinetics Considerations. Elsevier, 675–697. 10.1016/B978-0-12-814425-1.00003-6

92

Shirota H. Klinman D. M. (2017). “CpG oligodeoxynucleotides as adjuvants for clinical use,” in Immunopotentiators in modern vaccines. Elsevier, 163–198. 10.1016/B978-0-12-804019-5.00009-8

93

Steimbach L. Borgmann A. V. Gomar G. G. Hoffmann L. V. Rutckeviski R. de Andrade D. P. et al (2021). Fungal beta-glucans as adjuvants for treating cancer patients – a systematic review of clinical trials. Clin. Nutr.40, 3104–3113. 10.1016/j.clnu.2020.11.029

94

Steinmetz M. O. Prota A. E. (2018). Microtubule-targeting agents: strategies to hijack the cytoskeleton. Trends Cell Biol.28, 776–792. 10.1016/j.tcb.2018.05.001

95

Stone A. E. Rambaran S. Trinh I. V. Estrada M. Jarand C. W. Williams B. S. et al (2023). Route and antigen shape immunity to dmLT-adjuvanted vaccines to a greater extent than biochemical stress or formulation excipients. Vaccine41, 1589–1601. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.01.033

96

Sun X. Zhou X. Lei Y. L. Moon J. J. (2023). Unlocking the promise of systemic STING agonist for cancer immunotherapy. J. Control. Release357, 417–421. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2023.03.047

97

Sun Y. Gruber M. Matsumoto M. (2012). Overview of global regulatory toxicology requirements for vaccines and adjuvants. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods65, 49–57. 10.1016/j.vascn.2012.01.002

98

Sunita Sajid A. Singh Y. Shukla P. (2020). Computational tools for modern vaccine development. Hum. Vaccin Immunother.16 (3), 723–735. 10.1080/21645515.2019.1670035

99

Toprani V. M. Hickey J. M. Sahni N. Toth R. T. Robertson G. A. Middaugh C. R. et al (2017). Structural characterization and physicochemical stability profile of a double mutant heat labile toxin protein based adjuvant. J. Pharm. Sci.106, 3474–3485. 10.1016/j.xphs.2017.07.019

100

Tu A. T. T. Hoshi K. Ikebukuro K. Hanagata N. Yamazaki T. (2020). Monomeric G-quadruplex-based CpG oligodeoxynucleotides as potent toll-like receptor 9 agonists. Biomacromolecules21, 3644–3657. 10.1021/acs.biomac.0c00679

101

Valli E. Baudier R. L. Harriett A. J. Norton E. B. (2020). LTA1 and dmLT enterotoxin-based proteins activate antigen-presenting cells independent of PKA and despite distinct cell entry mechanisms. PLoS One15, e0227047. 10.1371/journal.pone.0227047

102

Van Herck S. Feng B. Tang L. (2021). Delivery of STING agonists for adjuvanting subunit vaccines. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev.179, 114020. 10.1016/j.addr.2021.114020

103

Vasiyani H. Wadhwa B. Singh R. (2023). Regulation of cGAS-STING signalling in cancer: approach for combination therapy. Biochimica Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Rev. Cancer1878, 188896. 10.1016/j.bbcan.2023.188896

104

Verma S. K. Mahajan P. Singh N. K. Gupta A. Aggarwal R. Rappuoli R. et al (2023). New-age vaccine adjuvants, their development, and future perspective. Front. Immunol.14, 1043109. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1043109

105

Vishwakarma M. Agrawal P. Soni S. Tomar S. Haider T. Kashaw S. K. et al (2024). Cationic nanocarriers: a potential approach for targeting negatively charged cancer cell. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci.327, 103160. 10.1016/j.cis.2024.103160

106

Wallis R. S. O’Garra A. Sher A. Wack A. (2023). Host-directed immunotherapy of viral and bacterial infections: past, present and future. Nat. Rev. Immunol.23, 121–133. 10.1038/s41577-022-00734-z

107

Wang J. Meng F. Yeo Y. (2024a). Delivery of STING agonists for cancer immunotherapy. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol.87, 103105. 10.1016/j.copbio.2024.103105

108

Wang Q. Jiang H. Zhang H. Lu W. Wang X. Xu W. et al (2024b). β-Glucan–conjugated anti–PD-L1 antibody enhances antitumor efficacy in preclinical mouse models. Carbohydr. Polym.324, 121564. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2023.121564

109

Wang X. Gigant B. Zheng X. Chen Q. (2023). Microtubule-targeting agents for cancer treatment: seven binding sites and three strategies. MedComm – Oncol.2. 10.1002/mog2.46

110

Wang Y. Liu S. Li B. Sun X. Pan Q. Zheng Y. et al (2024c). A novel CpG ODN compound adjuvant enhances immune response to spike subunit vaccines of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. Front. Immunol.15, 1336239. 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1336239

111

Wang Z. Chen Q. Zhu H. Yin X. Wang K. Liu Y. et al (2021). Enhancing the immune response and tumor suppression effect of antitumor vaccines adjuvanted with non-nucleotide small molecule STING agonist. Chin. Chem. Lett.32, 1888–1892. 10.1016/j.cclet.2021.01.036

112

Wang Z.-B. Xu J. (2020). Better adjuvants for better vaccines: progress in adjuvant delivery systems, modifications, and adjuvant–antigen codelivery. Vaccines (Basel)8, 128. 10.3390/vaccines8010128

113

Wordeman L. Vicente J. J. (2021). Microtubule targeting agents in disease: classic drugs, novel roles. Cancers (Basel)13, 5650. 10.3390/cancers13225650

114

Wu J. Chen G. Fan C. Shen F. Yang Y. Pang W. et al (2023). An adjustable adjuvant STINGsome for tailoring the potent and broad immunity against SARS-CoV-2 and monkeypox virus via STING and necroptosis. Adv. Funct. Mater33. 10.1002/adfm.202306010

115

Xuan C. Hu R. (2023). Chemical biology perspectives on STING agonists as tumor immunotherapy. ChemMedChem18, e202300405. 10.1002/cmdc.202300405

116

Yao Z. Liang Z. Li M. Wang H. Ma Y. Guo Y. et al (2024). Aluminum oxyhydroxide-Poly(I: C) combination adjuvant with balanced immunostimulatory potentials for prophylactic vaccines. J. Control. Release372, 482–493. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2024.06.054

117

Yemeke T. Chen H.-H. Ozawa S. (2023). Economic and cost-effectiveness aspects of vaccines in combating antibiotic resistance. Hum. Vaccin Immunother.19, 2215149. 10.1080/21645515.2023.2215149

118

Yenkoidiok-Douti L. Jewell C. M. (2020). Integrating biomaterials and immunology to improve vaccines against infectious diseases. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng.6, 759–778. 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.9b01255

119

Yin J. Wu H. Li W. Wang Y. Li Y. Mo X. et al (2024). Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin B subunit as an adjuvant of mucosal immune combined with GCRV-II VP6 triggers innate immunity and enhances adaptive immune responses following oral vaccination of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Fish. Shellfish Immunol.154, 109969. 10.1016/j.fsi.2024.109969

120

Yu C. An M. Li M. Liu H. (2017). Immunostimulatory properties of lipid modified CpG oligonucleotides. Mol. Pharm.14, 2815–2823. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.7b00335

121

Yu H. Jiang X. Shen C. Karunakaran K. P. Jiang J. Rosin N. L. et al (2010). Chlamydia muridarum T-cell antigens formulated with the adjuvant DDA/TDB induce immunity against infection that correlates with a high frequency of gamma interferon (IFN-γ)/Tumor necrosis factor alpha and IFN-γ/Interleukin-17 double-positive CD4 + T cells. Infect. Immun.78, 2272–2282. 10.1128/IAI.01374-09

122

Zhang Z. Kuo J. C.-T. Yao S. Zhang C. Khan H. Lee R. J. (2021). CpG oligodeoxynucleotides for anticancer monotherapy from preclinical stages to clinical trials. Pharmaceutics14, 73. 10.3390/pharmaceutics14010073

123

Zhu S. Qiao Y. Wu J. Zang G. Liu Y.-J. Chen J. (2015). Human cancer cells respond to cytosolic nucleic acids via enhanced production of interferon-β and apoptosis. J. Immunother. Cancer3, P250. 10.1186/2051-1426-3-S2-P250

Summary

Keywords

immunotherapy, adjuvants, vaccine, cancer, infectious diseases

Citation

Desai N, Gotru S, Salave S and Vora LK (2025) Vaccine adjuvants for immunotherapy: type, mechanisms and clinical applications. Front. Biomater. Sci. 4:1544465. doi: 10.3389/fbiom.2025.1544465

Received

12 December 2024

Accepted

22 January 2025

Published

12 February 2025

Volume

4 - 2025

Edited by

Aditi Jhaveri, Northeastern University, United States

Reviewed by

Rishi Kumar Jaiswal, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Desai, Gotru, Salave and Vora.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lalitkumar K. Vora, l.vora@qub.ac.uk

† Present addresses: Nimeet Desai, Department of Eye and Vision Science, Institute of Life Course and Medical Sciences, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, United Kingdom Sagar Salave, Vaccine Analytics and Formulation Center (VAFC), Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, The University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, United States

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.