- The Primary Care Unit, Department of Public Health and Primary Care, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom

Background: Communication of concepts relating to risk and risk assessment can be challenging for lay individuals to understand. As we move toward risk-stratified screening for bowel cancer, it is necessary to identify public information needs and explore understanding of communication about risk stratification and personal cancer risk as this may have implications for screening uptake. We aimed to develop and test comprehension of a screening leaflet relating to risk-stratified fecal immunochemical test (FIT) screening intervals and to explore participant attitudes toward stratified intervals for bowel cancer screening.

Methods: We adapted an existing NHS England bowel cancer screening leaflet to communicate a bowel cancer screening programme with risk-stratified screening intervals. The leaflet was used in 13 think aloud interviews to elicit areas of misunderstanding and potential alteration. We analyzed the interviews using codebook thematic analysis and made changes based on our findings. We then tested comprehension of the final leaflet with a further 20 participants in a user testing survey. We also analyzed attitudes toward risk-based bowel screening thematically.

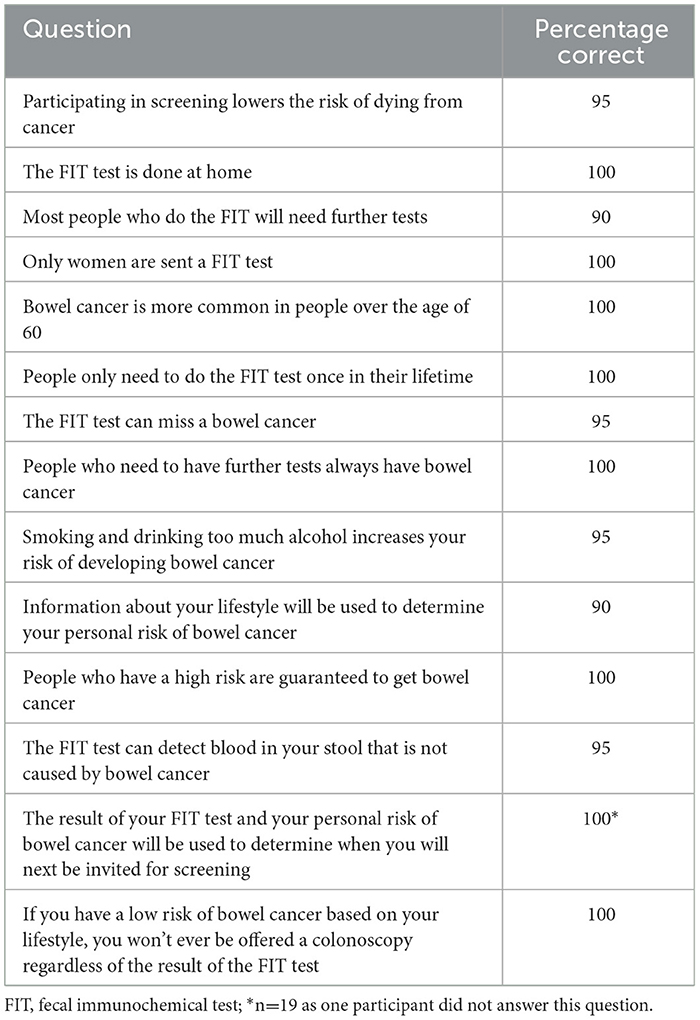

Results: The think aloud interviews identified 42 areas of the adapted leaflet that required improvement and 35 of these were incorporated into the final version. Changes included clarifying terminology, improving layout including greater use of bullet points, and resolving areas of misunderstanding. They also suggested additional information to mitigate cancer worry. At least 90% of user testing participants answered each true or false statement correctly after reading the final version of the leaflet.

Conclusions: Specific elements of the initial risk-stratified leaflet required improvement; after revision, user testing indicated that a minimum threshold of comprehension had been achieved in the final version. Based on the information provided in this leaflet, a risk-stratified approach to bowel cancer screening was considered acceptable overall. With appropriate care taken to develop materials, the public are, therefore, able to understand information about risk-based bowel screening programmes delivered as part of population-based communications.

1 Background

The current bowel cancer screening programme in England invites those aged 54–74 to participate in fecal immunochemical testing (FIT), to detect blood in the feces (1). Individuals who have a fecal hemoglobin (FHb) concentration above the current threshold of 120 μg/g are referred for further investigation, whilst those below the threshold are invited to complete FIT screening again in 2 years' time. There is an ongoing shift toward a more personalized approach to screening, based on individual risk, both nationally within the NHS and internationally (2). For example, high risk individuals may be offered a reduced screening interval while those at low risk are offered an extended one. This would target constrained healthcare resources toward the people in society who stand to benefit most from screening and simultaneously minimize exposure to the harms of screening for lower risk groups. In the context of screening by FIT, such harms include overdiagnosis (where an adenoma is treated that would never have gone on to cause harm), anxiety and the potential for false positive and false negative results, causing unnecessary concern and false reassurance respectively (3). There is also the potential for unnecessary further investigations such as colonoscopy, which carry additional harms. Such an approach will likely require communication of personal risk, risk-informed screening schedules and the rationale behind risk-stratified screening to the public. Successful communication is a necessary factor for facilitating public acceptability of changes away from traditional age and/or sex-based policies and instilling confidence in the outputs of a risk algorithm (4, 5).

The concept of risk in general is both complex and multidimensional, meaning that conveying personalized estimates in a meaningful way and altering risk schedules in accordance with these remains challenging (6). Studies across multiple diseases have shown that the public typically prefer gist-based information supported by diagrams and comparative illustrations of risk, and that comprehension of mathematical concepts, such as percentages and frequencies, may be prone to misinterpretation (6–12). Communication of personal cancer risk and risk-related concepts potentially incurs an additional challenge in the context of the implementation of risk-based screening as the public often have limited knowledge and understanding of the harms and benefits associated with cancer screening (8, 9, 13).

Previous literature has identified that communication of risk and risk-stratified screening must therefore be careful not to contradict existing public health messaging primarily concerned with promoting uptake (4). This is especially key when communicating reduced screening for low-risk groups, which is generally perceived as less acceptable than increasing screening for those at high risk (4, 5, 14). Additionally, the English Bowel Cancer Screening Programme (BCSP) currently delivers dichotomous results, either positive or negative, omitting the nuance of absolute FHb concentration. As a result, the public are largely unaware that someone with a negative result may have a FHb concentration between 0–120μg/g. This existing style of communication makes it more difficult to successfully communicate a risk-stratified programme where elements of screening are based on absolute concentrations. As we move toward personalized screening for bowel cancer, there is therefore a need to explore the information needs of the public and how these relate to risk communication, screening schedule alterations, and the screening programme as a whole. We therefore aimed to develop and test comprehension of an information leaflet for a bowel cancer screening programme employing risk-stratified screening intervals, based on absolute FHb concentration with additional risk factors. Secondarily, we aimed to explore individual-level views toward this approach to bowel cancer screening amongst those provided with this information.

2 Methods

The “NHS bowel cancer screening: helping you decide” leaflet (15), which members of the public are sent at the first invite to bowel cancer screening, was adapted by the authors according to previous literature and the input of two Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) members, to reflect a bowel cancer screening programme employing risk-stratified screening intervals. We also piloted the adapted leaflet with three members of the Cambridge BRC PPI panel ahead of the think aloud interviews.

The initial leaflet contained information on the following topics: (I) Why we offer bowel cancer screening; (II) Who we invite; (III) How the bowel works; (IV) Bowel cancer; (V) Risks of developing bowel cancer; (VI) How bowel cancer screening works; (VII) Reduce your risk of bowel cancer; (VIII) Using the FIT kit; (IX) Bowel cancer screening results; (X) What happens to samples after testing; (XI) If you need further tests; (XII) Colonoscopy; (XIII) Possible benefits and risks of bowel cancer screening; (XIV) Bowel cancer symptoms; (XV) Treatment for bowel cancer. Eight of these headings (Why we offer bowel cancer screening; Who we invite; How the bowel works; Bowel cancer; Risks of developing bowel cancer; How bowel cancer screening works; Possible benefits and risks of cancer screening; colonoscopy) were retained in the leaflet communicating risk-stratified screening intervals in order to provide adequate background to bowel cancer and FIT screening. These sections were reordered and the text amended slightly. Additional sections on the risk of developing bowel cancer, risk calculation, and risk-stratified screening outcomes were added. The risk-stratified leaflet communicated a screening programme in which individuals with a moderate or high risk of developing bowel cancer (according to their FIT result and individual level risk factors) would receive a 1 year screening interval, whereas those with a low risk would receive a 3 year interval. Individuals determined to be of average risk would continue to receive biennial FIT screening, in line with the current screening programme in England.

The original NHS England leaflet contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence V3.0 (https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3/).

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Cambridge Psychology Research Ethics Committee (ref: PRE.2023.023).

2.1 Study design

2.1.1 Think aloud interviews

During the interviews, participants were asked to “think aloud” by vocalizing their internal cognitive process whilst reading the leaflet about risk-stratified screening intervals. The information processed whilst completing a task is available within the short term memory, meaning that retrospective expression of the thinking process inadequately reflects the spontaneous thoughts involved in mediation of the task (16). However, such thoughts may be elicited through concurrent verbalization during the task, meaning the think aloud method provides novel insight into the research question by illuminating a participant's internal cognition. This method remains distinct from traditional interview techniques which employ introspection and reflection and has previously been successfully used in both health psychology and healthcare research (16–21).

The think aloud interviews were held using Zoom video conferencing software (Zoom Video Communications). A technical check was conducted prior to each interview to mitigate any technical issues and ensure participants were comfortable with the video conferencing process. Each interview was up to 1 h in duration. Participants were not sent the information leaflet in advance and viewed it on the researcher's shared screen during the interview. The interviews were conducted by a researcher with previous experience of qualitative research and interview technique (LT).

The researcher asked participants to read the risk-stratified information leaflet whilst thinking aloud by verbalizing any internal thoughts prompted by the material. In order to ensure they felt comfortable doing this, she asked them to first practice thinking aloud using a pilot text about an unrelated topic (16). Any participants who failed to vocalize their thoughts during the first half of the pilot text had the think aloud process explained again and were given the opportunity to practice using the second half of the pilot before moving on to the interview itself. Both the pilot text and the leaflet employed a marked protocol design in which red dots are strategically placed in the text and act as prompts for verbalization. These were placed at the end of short paragraphs, sentences or bullet points that were of particular relevance to the research question(s) (11).

The results of the think aloud interviews were used to identify areas of misunderstanding in the initial leaflet which was then refined before being evaluated by a user testing procedure.

We also explored participant attitudes toward risk-based screening for bowel cancer expressed during the interviews. The think aloud participants reacted to the concept of risk stratification based solely on the information provided in the screening leaflet and did not receive supplementary education about the approach. Therefore, this strategy enabled us to capture the views and opinions of members of the public receiving such information.

2.1.2 User testing procedure

The use of true or false statements in user testing has previously been used to assess health-related knowledge and understanding (11, 22). A short survey adapted from a previous study by Smith et al. (11) that aimed to develop and test supplementary information for bowel cancer screening was used to assess understanding of the refined leaflet. Participants read the refined text before answering 14 true or false questions about the leaflet content. The user testing statements were designed to measure objective comprehension, i.e., whether the participants understood the content, rather than subjective comprehension, meaning whether participants thought that they understood the content. In line with the approach published by Usher-Smith et al. (12), a minimum of 80% of participants were required to answer each question correctly to meet the threshold of comprehension. After each round, the information is typically revised in areas where fewer than 80% of participants answered correctly for a maximum of five rounds. Eight of the true or false statements were adapted from Smith et al., including statements about the prevalence of bowel cancer, the logistics of FIT screening, and the associated benefits and harms. The remaining six statements were developed based on the key areas of misunderstanding identified by the think aloud interviews and information specific to the risk-stratified approach. These statements were reviewed and amended by the PPI representatives to maximize understanding among lay individuals.

2.2. Participants and recruitment

2.2.1 Think aloud interviews

We aimed to initially recruit 15 participants, purposely sampled by age, sex, social grade, geographic location in England, and previous bowel cancer screening attendance via iPoint Research Ltd, a market recruitment company. Previous think aloud studies have reported minimum sample sizes of between five and 18 participants (23). Eligible participants were aged 50–74 living in England without medical expertise or a previous bowel cancer diagnosis, and had not participated in previous studies conducted by this research group (5, 24). iPoint Research obtained consent, provided study details and facilitated participant reimbursement at their recommended rate. We also used a short Qualtrics survey distributed via iPoint using individualized links to collect demographic information and the list of personal identifiers was stored on the Cambridge School of Clinical Medicine Secure Data Hosting Server (SDHS).

2.2.2 User Testing Procedure

We planned to recruit participants in rounds of 20 individuals to complete the user testing survey until the threshold of comprehension (80%) was reached by all participants in a round, or until a maximum of 100 participants completed the survey. As described in the results (Section 3.3), the threshold of comprehension was reached in the first round; therefore no further participants were recruited. Participants were recruited online via the prolific platform, a recruitment platform for researchers where participants volunteer to participate in studies and are compensated at a previously agreed rate. Eligible participants were aged 50–74 living in the UK, without a personal history of bowel cancer or medical expertise and were purposely sampled by age and sex.

In line with standard procedure on the prolific platform, participants were able to view a short summary of the study before agreeing to take part. Once they had agreed to do so, they were able to download the participant information sheet and complete written online consent before beginning the survey. All participants were free to withdraw their consent at any time.

2.3 Analysis

2.3.1 Think aloud interviews

Interview data were collected online using Zoom's record function. Recordings were transcribed verbatim via an external transcription company, using a 256 bit SSL encrypted upload process. They were then pseudonymized by a member of the study team (LT). The interview transcripts were analyzed using codebook thematic analysis (25, 26); whereby the leaflet section headings were used to deductively generate a high-level framework. The data within each heading were reviewed and suggested leaflet changes were identified according to the preferences, opinions, and misunderstandings expressed by interview participants. These suggested changes were tabulated according to the coding frame and a traffic light and icon system was used to indicate the feasibility of applying each change to the risk-stratified screening leaflet. The same method of codebook thematic analysis was used to analyze participant attitudes toward the intervention, in which areas of commonality were grouped and both unifying and divergent themes identified. The interviews and analysis were led by a member of the study team with previous experience of qualitative methods and thematic analysis techniques (LT). All members of the study team, who also have previous experience analyzing qualitative research, reviewed and contributed to the analysis, and two PPI members without a personal history of cancer reviewed the findings.

2.3.2 User testing procedure

The user testing survey was hosted via Qualtrics and anonymized demographic information and survey responses were stored on the University of Cambridge shared drive. The quantitative data from the survey were analyzed using descriptive statistics, where the percentage of participants who answered each true or false statement correctly was calculated.

3 Results

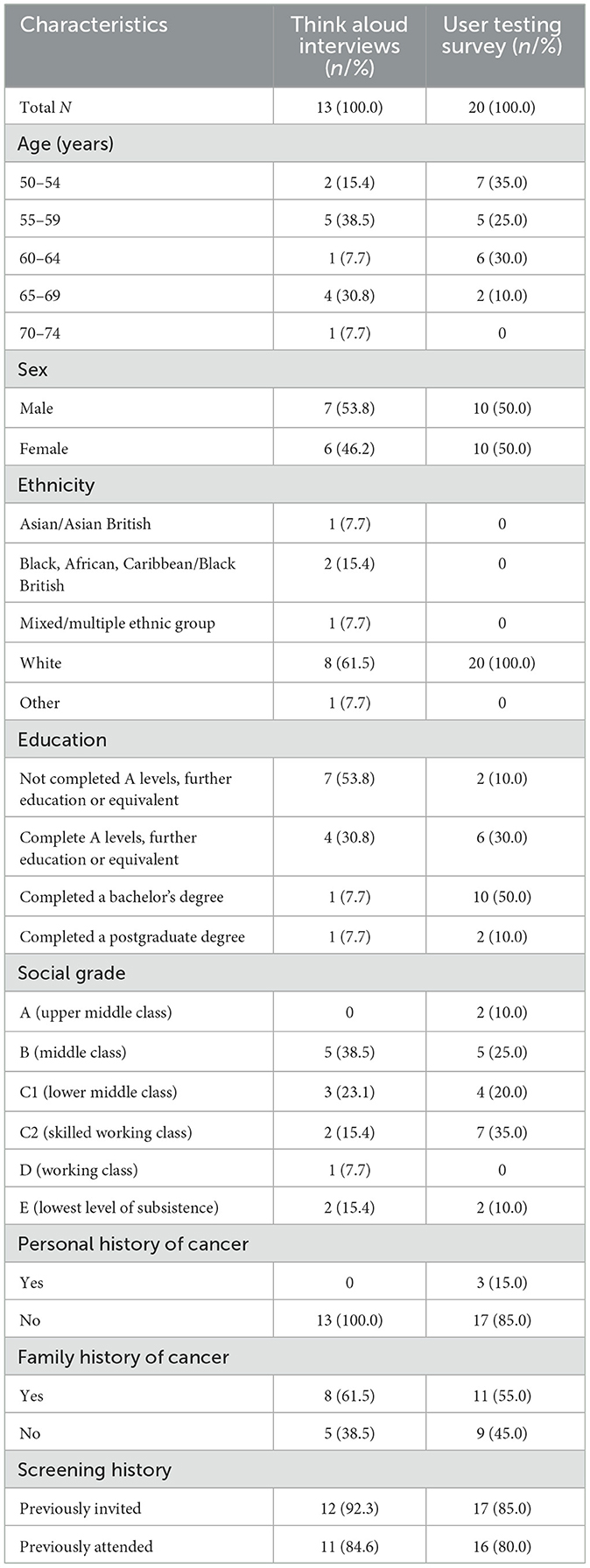

3.1 Participant characteristics

The demographic characteristics of the 13 participants who took part in the think aloud interviews are summarized in Table 1. We chose not to recruit further participants as no new themes were identified in the later interviews, indicating that sufficient data had been collected with which to draw conclusions about the research question. Reflecting the demographics of the UK, the sample was balanced between male (53.8%) and female (46.2%) participants and comprised a range of ethnicities. In general, the sample was educated to a greater degree than average, with 15.4% of participants educated to degree level. Additionally, all participants had completed at least A levels or an equivalent qualification. Attendance at cancer screening was high (84.6%), with only one participant having previously declined screening, and the majority of participants reported having a family history of cancer (61.5%).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants in the think aloud interviews and user testing survey.

Twenty participants were recruited to take part in the think aloud survey (Table 1). Again, the sample was evenly split between male (50.0%) and female (50.0%) participants, and the majority had completed further education to degree level (60.0%). Screening attendance was high (80%) and most participants reported a family history of cancer (55.0%), with three individuals reporting a personal cancer history (15.0%). Notably, all 20 participants were of White ethnicity.

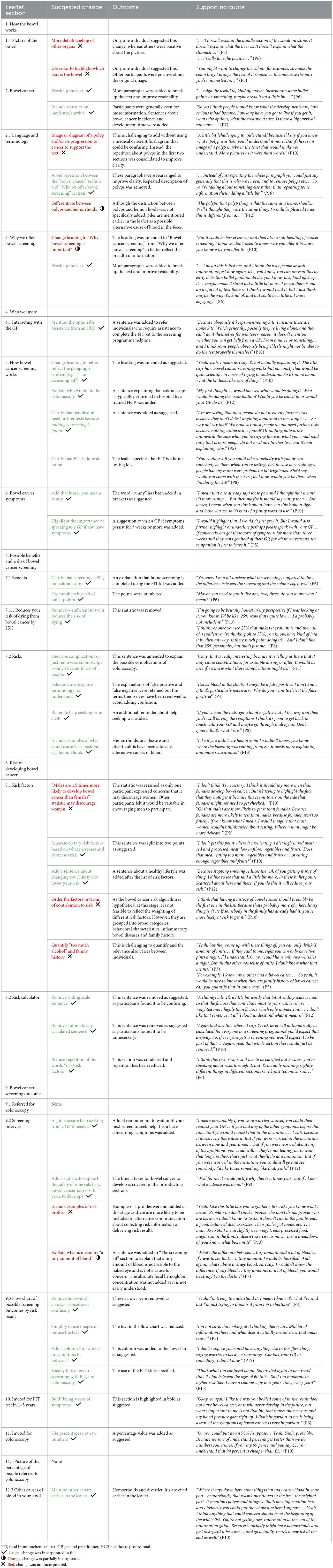

3.2 Changes to the information leaflet: think aloud interviews

The think aloud interviews were analyzed using codebook thematic analysis and key findings are summarized in Table 2. Participants suggested a total of 42 potential changes to the screening leaflet; 32 of these were incorporated fully, three were incorporated partially and seven changes were rejected from the refined version of the leaflet. Overall, 25 suggested changes related to sections of the leaflet that were included in the original NHS leaflet and a further 17 changes related to the additional risk-stratified elements of the text. The section of the leaflet entitled “Possible benefits and risks of bowel cancer screening” generated the greatest number of suggested changes, despite being included in the original NHS information. A total of seven changes were suggested within this section, largely relating to minimizing potential areas of confusion, and all of these were included in the refined version.

Table 2. Codebook thematic analysis results: summary of suggested changes identified by the think aloud interviews.

Changes that were most commonly made to the refined leaflet related to increased clarity and improving readability. Examples of this included the introduction of bullet points, simplification of terminology and minimizing unnecessary details.

The most frequent reason for rejecting a suggested change was where only a single participant had proposed the change and others had expressed positive reflections on the same section of text. For example, one participant suggested labelling other organs in the image of the bowel to help them to interpret it, however, multiple other participants were very positive about the existing image.

3.3 Understanding of the revised information leaflet: user testing survey

The user testing survey results are reported in Table 3. At least 90% of participants (18/20) answered each of the user testing survey statements correctly. The previously established threshold of comprehension was 80%, therefore, the leaflet could be considered comprehensible after a single round of user testing. Seven statements were answered correctly by all 20 participants, including statements about who would be sent a FIT kit, how risk factors are used and whether low risk people may be offered a colonoscopy. The fewest number of participants (90%) answered the following two statements correctly: “Most people who do the FIT will need further tests” and “Information about your lifestyle will be used to determine your personal risk of bowel cancer.”

3.4 Wider reflections on risk stratification: think aloud interviews

Think aloud participants expressed their views on risk assessment and risk-stratified screening for bowel cancer throughout the interviews.

3.4.1 Risk factors and calculating risk estimates

The majority of participants expressed positive views on the inclusion of bowel cancer risk factors in the information leaflet, seeing it as a potential “alert for a lot of people” (P8) who may not be aware of their increased risk status. Some participants considered that awareness of the risk factors may incentivize people to be compliant with screening recommendations:

“Actually yeah, if somebody's doubting about having the screening, doing the screening or participating, on seeing the things that could actually help develop an issue, might make them feel more inclined, ‘Well, I'll go and get screened. I'm not going to change my diet or my alcohol intake but I'll do a screening'.” – P9

For many of the participants, reading the list of potential risk factors resulted in a self-appraisal of their own risk status and lifestyle choices. However, no participants vocalized reflections on having a low-risk lifestyle. Individuals who identified with high-risk lifestyle choices appeared to experience a degree of anxiety:

“So that's me, not being active enough. I'm overweight and I can't stand veg, I will not eat veg. So that's it, I might as well quit now, goodbye (laughs).” – P13

Despite this, the use of risk factors in calculating personal risk estimates was well-received and participants appreciated that “as long as you're being honest about it, it will tell you your risk and then you can cut those risks” (P3). This information was therefore also seen as a potential impetus for behavior change to manage personal risk of bowel cancer.

The leaflet stated that “estimating the risk of bowel cancer is not 100% perfect. People who have a high risk are not guaranteed to develop bowel cancer. Similarly, it is not guaranteed that people with a low risk will not develop bowel cancer.” Some individuals found this statement to be reassuring for people in receipt of a high-risk estimate whilst also ensuring that low-risk cohorts remain cautious. Other participants saw this as inevitability or a fact of life, while a minority questioned the purpose of individualized risk scores if they may get cancer regardless:

“It doesn't guarantee that you'll necessarily get bowel cancer, or that the low-risk people might get it. It's just that's the way the cookie crumbles probably.” – P12

3.4.2 Risk stratification and screening outcomes

In general, participants felt that risk stratification for bowel cancer screening was a sensible and acceptable approach to cancer prevention:

“I mean it's what you'd hope… a low-risk patient doesn't need to waste both of their times [patient and HCP] coming back often, but a medium- and high-risk has got to come more often, dependent on their risks…” – P1

The fact that the risk assessment would have a tangible impact on screening outcomes was viewed positively and participants felt that action ability of risk scores was beneficial:

“...I think that's really good. ‘You'll be invited to the next screening.' I think it's nice that people don't feel that they're left in the lurch. They've filled in a questionnaire and then they never hear anything else. That's nice to think that they've put their time in, so the professionals will then put their time in to analyse what's been said. So I think that's good.” – P12

The intensification of screening for groups of the population deemed to be at higher risk of bowel cancer was met with clear enthusiasm and participants found it to be a source of reassurance that the healthcare service would be “taking it serious” (P9) and would “keep an eye on you” (P1). Conversely, most participants were skeptical about a reduction in screening for those at lower risk. For many, a 3 year screening interval initially felt too long as “anything can happen in three years” (P3) and some even advocated for yearly FIT screening for all members of the population, regardless of individual risk, despite being aware that this was not a feasible option at the population level. In general, supporting evidence was requested to demonstrate the safety of an increased screening interval:

“Yes, I mean, personally I would like to know, I mean what is that based on? What are you basing these decisions on for one year or two years?” – P6

The knowledge that people with a concerning level of FHb would be offered a colonoscopy regardless of their risk score was a source of reassurance that helped to alleviate some concerns over increasing screening intervals:

“The first bit's very good. If they detect blood you'll be offered a colonoscopy, so that's excellent. I'd be very happy with that.” – P2

Throughout the interviews, participants repeatedly advocated for greater reassurance and signposting relating to seeking help directly from primary care if symptoms arise between screening rounds. This addition was considered essential if risk-based intervals were to be accepted and some felt that, without it, symptomatic individuals may wait for their next invite to screening. It was thought that this could increase the rate of interval cancers and cancers diagnosed at a later stage:

“Exactly, because I think you always have to make that clear. That don't just wait for the three years to be up… you might not be here to tell the tale… If anything changes then obviously seek help professionally. I think that's always important for people to know. ‘Oh, I'm alright for three years' – no you're not. Just like a lump in our breasts, we don't wait for the next screening'.” – P8

After being informed that bowel cancer takes 10–15 years to develop, participants vocalized feelings of reassurance and comfort around the potential for an increased screening interval:

“If people knew that is how long it would take to develop, then that is comforting to know that. That this is the screening, you have been invited yearly, two years, three years' time. That is more reassuring, and I know that if something goes wrong within those three years, I will still be in that window of getting help.” – P11

4 Discussion

To the authors' knowledge, this is the first study to explore public understanding of written information relating to risk-adapted screening intervals for bowel cancer screening in England and to explore views on risk-adapted screening amongst those presented with information in a similar format to that likely to be used within future bowel cancer screening programmes. The think aloud interviews identified a total of 42 areas of the information leaflet that could potentially be improved. Participants expressed confusion over the harms of screening, particularly in relation to terminology such as “false positive/negative” results, and consequently suggested removing such terms. A notable finding was that many participants repeatedly vocalized a desire for greater reassurance about contacting a GP if they developed concerns or symptoms throughout the leaflet, fearing that the public may otherwise wait for their next invite to screening and risk a potential interval cancer with a later-stage diagnosis. When asked to consider sections of the leaflet communicating information specific to risk stratification, participants found the notion of a risk calculator to be particularly challenging. Although many participants called for more information around reassurance, in the case of risk calculation and the weighting of risk factors, they felt that less information would be more effective and encouraged simplified language. Somewhat unsurprisingly, participants were enthusiastic about the prospect of intensified screening for people at higher risk of developing bowel cancer and no participants expressed concern over this aspect of a risk-based approach to screening. On the other hand, many participants vocalized concerns or reticence over reducing screening using extended screening intervals for those at low risk. Some speculated that a 3 year interval was too long to wait between successive rounds of FIT screening and the prospect of this induced feelings of anxiety or concern. As such, participants suggested the addition of information about the safety of extended screening intervals, specifically the approximate time taken for bowel cancer to develop.

4.1 Implications

Overall, participants in this study demonstrated sufficient understanding of information about risk-stratified intervals for bowel cancer screening. The majority of user testing participants answered all the survey statements correctly in the first round, demonstrating that the refined leaflet had successfully achieved the minimum level of comprehension. The leaflet we have developed here can also be used as a starting point to develop further communication materials. For example, we have adapted the refined leaflet to reflect hypothetical bowel cancer screening programmes with risk-stratified eligibility criteria and FIT thresholds, used in survey study published elsewhere (27).

The results of the think aloud interviews highlight several key requirements for successful public communication: simple terminology, language, and layout should be used, especially when addressing complex concepts where there is increased potential for misinterpretation. We have also elucidated fundamental principles for communicating information specific to risk-based screening. Firstly, the most important information should be prioritized when describing and explaining the process of risk calculation, to avoid overwhelming people with non-essential details. Secondly, the rationale for and safety of reduced screening for low-risk groups must be evidenced if the public are to feel confident accepting such changes. This information is aimed at reassuring the public that less frequent screening would be both safe and based on scientific evidence and may assist in preventing public backlash about programme changes. Finally, clear and repeated reassurance about contacting a GP if symptoms or concerns arise may help to alleviate public concerns about interval cancers, particularly if risk-stratification resulted in some individuals having longer intervals between screening episodes.

The majority of suggested changes to the leaflet related to information that is provided as part of the original NHS leaflet, indicating that the current information is unlikely to meet the needs of some individuals in the screening population. As such, efforts to improve current bowel cancer screening materials should be pursued. We have demonstrated here that use of a think aloud method alongside a quantitative user testing survey is an effective way of refining patient-facing written materials and would be a suitable approach to improving existing materials.

4.2 Comparison with other literature

Several think aloud studies have utilized NHS cancer screening leaflets and other written materials to develop and test public-facing information. Such studies similarly identified that NHS documentation may not be effectively meeting the needs of all members in the target populous (21, 28, 29). Additionally, public understanding of screening harms and associated terminology around false positive or negative results is generally considered to be sub-optimal, as previously demonstrated by research into public attitudes toward screening leaflets for lung and cervical cancer (28, 30). It was, therefore, not unsurprising that think aloud participants found understanding such concepts to be challenging and a source of significant confusion in the initial version of the leaflet. Nevertheless, the fact that effective communication of screening harms to the public has been a long-standing challenge does not mean we should cease striving to improve public understanding of these concepts, particularly when the future of many screening programmes is likely to involve the incorporation of some level of risk stratification (2, 31). This sustained ineffective communication and hence poor public understanding has the potential to impede informed decision-making, a necessary factor in the UK National Screening Committee (UKNSC) criteria for implementing screening programmes (32).

A specific area that participants in this study had difficulty interpreting was the statistic that taking part in FIT screening reduces the risk of dying by 25%. Although responses to this statistic varied, participant reactions were largely negative as some perceived this to be an underwhelming incentive to complete screening and others conflated it's meaning entirely, leading to the recommendation that it be omitted from the refined leaflet. For example, one participant erroneously interpreted the risk of dying from bowel cancer being 75%. A 2019 study exploring how the public interpreted the NHS screening leaflet for cervical cancer reported comparable misunderstanding of statistics conveying the impact of cervical screening on incidence. In this case, participants mistakenly overestimated the number of women who would go on to be diagnosed with cervical cancer (28). Such findings suggest that particular consideration should be given to expressing statistics associated with cancer risk, incidence and mortality and best practice guidelines should be adhered to (33, 34).

Elicitation of emotional responses when reading cancer screening leaflets, such as the way study participants were prompted to engage in self-appraisal when reading about risk factors, has also been previously documented in related contexts (21, 30, 35), including participants in a think aloud study presented with a list of lung cancer symptoms as part of an NHS targeted lung health check leaflet who also experienced thoughts of self-reflection about their own health (30).

4.3 Strengths and limitations

A key strength of this study is the use of an established think aloud method that has demonstrated previous success when employed in related contexts and facilitated concurrent exploration of cognition and processing that may have been unobservable were participants asked to recall their thoughts in retrospect. A further strength is the use of the NHS leaflet as a starting point, ensuring our adapted leaflet was as realistic as possible. A marked protocol ensured sufficient data collection relating to risk-related sections of the leaflet to enable us to meet the aims of the study. Involvement of PPI in the development phase as well as pilot interviews with PPI representatives served to refine readability and comprehension of the leaflet before it was used in the think aloud interviews, potentially contributing to the need for minimum rounds of user testing. Furthermore, exploring participant reflections on risk stratification generated by reading the screening leaflet is likely to better reflect public reactions as the amount and format of information is more comparable to real-life screening programme communication than other qualitative research where participants have either been more or less informed about the approach. A final strength was the addition of the user testing component to quantitatively assess public understanding of the refined leaflet in an independent sample of participants. This setting more closely represents how participants would read the leaflet in a real world setting than in the think aloud interviews where they were prompted to think in greater detail.

On the other hand, our study sample was well-educated and predominantly of White ethnicity. This is a potential consequence of using a market recruitment agency and the prolific online platform as such an approach is susceptible to self-selection bias and may exclude participants with lower digital literacy. Consequently, the final leaflet may not be applicable for people who do not have English as their first language and/or among adults with low literacy levels. Further research should be conducted to develop and test understanding of risk-adapted cancer screening leaflets among these populations. Additionally, as there was only a single round of user testing, we are unable to comment on comparative comprehension between the initial and refined versions of the risk-stratified leaflet. A further potential limitation is that participants in both the interviews and the user testing process may have read the leaflet in more detail as a consequence of the research setting. Furthermore, user testing participants were aware that they would be asked true or false questions before they read the leaflet. Finally, the majority of the sample had previously been invited to attend screening, meaning they would have been exposed to screening information leaflets.

Additionally, the personal beliefs, prior research and attributes of a researcher can impact the researcher-participant relationship and analytical interpretations of results. The researcher who conducted the interviews (LT) is a White female below the screening age range. This may have narrowed the perceived power imbalance due to her younger age but also positioned her as someone who has no personal experience of bowel cancer screening. Nevertheless, personal experience of attendance at screening programmes for female-specific cancers helped to build rapport with some of the participants and the use of an unrelated pilot leaflet about gardening enabled the finding of common ground early in the interview. It is also possible that the research team's prior research and beliefs about the efficacy of risk-stratified screening impacted their interpretation of the results. However, two PPI members were also involved in interpreting the findings to mitigate this.

5 Conclusion

The high number of suggested changes to the initial leaflet suggested that the current NHS bowel cancer screening leaflet may not currently meet the needs of all members of the screening population. In the case of information relating to risk prediction and risk stratification specifically, participants advocated for clear and simple information to prevent confusion and were generally positive about a risk-based approach. This study demonstrates that an educated sample of the public are capable of understanding written information about risk-adapted intervals for bowel cancer screening when delivered as part of screening programme communication and find such an approach acceptable.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: Data are available via the University of Cambridge Data Repository (https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.113128).

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Cambridge Psychology Research Ethics Committee (ref: PRE.2023.023). All participants gave consent before taking part in the study. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Author contributions

LT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RD: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JU-S: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was funded by a National Institute for Health and Care Research Advanced Fellowship award (NIHR300861). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily reflective of those of the National Institute for Health and Care Research.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professor Christian von Wagner for advice on planning the study, our patient and public involvement representatives, Philip Dondi and Ruth Katz, and the Cambridge BRC PPI panel. The authors also thank our participants for giving their time to take part in this study.

Conflict of interest

LT is a Guest Associate Editor for Frontiers in Behavioral Aspects in Cancer Screening and Diagnosis.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor CV is currently organizing a research topic with the author LT.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. NHS England. Bowel cancer screening: programme overview (2024). Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/bowel-cancer-screening-programme-overview (accessed July 8 2024).

2. Autier P. Personalised and risk based cancer screening. BMJ. (2019) 367:l5558. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5558

3. CRUK. Bowel Cancer Screening. (2024). Available online at: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/bowel-cancer/getting-diagnosed/screening (accessed December 6, 2024).

4. Taylor LC, Hutchinson A, Law K, Shah V, Usher-Smith JA, Dennison RA. Acceptability of risk stratification within population-based cancer screening from the perspective of the general public: a mixed-methods systematic review. Health Expect. (2023) 26:989–1008. doi: 10.1111/hex.13739

5. Taylor LC, Dennison RA, Griffin SJ, John SD, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Thomas CV, et al. Implementation of risk stratification within bowel cancer screening: a community jury study exploring public acceptability and communication needs. BMC Public Health. (2023) 23:1798. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-16704-6

6. Riedinger C, Campbell J, Klein WMP, Ferrer RA, Usher-Smith JA. Analysis of the components of cancer risk perception and links with intention and behaviour: a UK-based study. PLoS ONE. (2022) 17:e0262197. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0262197

7. Kelley-Jones C, Scott S, Waller J. UK Women's views of the concepts of personalised breast cancer risk assessment and risk-stratified breast screening: a qualitative interview study. Cancers. (2021) 13:5813–5813. doi: 10.3390/cancers13225813

8. Usher-Smith JA, Mills KM, Riedinger C, Saunders CL, Helsingen LM, Lytvyn L, et al. The impact of information about different absolute benefits and harms on intention to participate in colorectal cancer screening: a think-aloud study and online randomised experiment. PLoS ONE. (2021) 16:e0246991. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246991

9. Bayne M, Fairey M, Silarova B, Griffin SJ, Sharp SJ, Klein WMP, et al. Effect of interventions including provision of personalised cancer risk information on accuracy of risk perception and psychological responses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Educ Couns. (2020) 103:83–95. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2019.08.010

10. Weinstein ND, Atwood K, Puleo E, Fletcher R, Colditz G, Emmons KM. Colon cancer: risk perceptions and risk communication. J Health Commun. (2004) 9:53–65. doi: 10.1080/10810730490271647

11. Smith SG, Wolf MS, Obichere A, Raine R, Wardle J, von Wagner C. The development and testing of a brief (‘gist-based') supplementary colorectal cancer screening information leaflet. Patient Educ Couns. (2013) 93:619–25. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.08.013

12. Usher-Smith JA, Silarova B, Lophatananon A, Duschinsky R, Campbell J, Warcaba J, et al. Responses to provision of personalised cancer risk information: a qualitative interview study with members of the public. BMC Public Health. (2017) 17:977. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4985-1

13. Usher-Smith J, von Wagner C, Ghanouni A. Behavioural challenges associated with risk-adapted cancer screening. Cancer Control. (2022) 29:10732748211060289. doi: 10.1177/10732748211060289

14. Taylor LC, Law K, Hutchinson A, Dennison RA, Usher-Smith JA. Acceptability of risk stratification within population-based cancer screening from the perspective of healthcare professionals: A mixed methods systematic review and recommendations to support implementation. PLoS ONE. (2023) 18:e0279201. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0279201

15. NHS England. NHS bowel cancer screening: helping you decide (2024). Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/bowel-cancer-screening-benefits-and-risks/nhs-bowel-cancer-screening-helping-you-decide (accessed April 25, 2014).

16. Eccles DW, Arsal G. The think aloud method: what is it and how do I use it? Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. (2017) 9:514–31. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2017.1331501

17. Gardner B, Tang V. Reflecting on non-reflective action: an exploratory think-aloud study of self-report habit measures. Br J Health Psychol. (2014) 19:258–73. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12060

18. Darker CD, French DP. What sense do people make of a theory of planned behaviour questionnaire? A think-aloud study. J Health Psychol. (2009) 14:861–71. doi: 10.1177/1359105309340983

19. Ericsson KA, Fox MC. Thinking aloud is not a form of introspection but a qualitatively different methodology: reply to schooler. Psychol Bull. (2011) 137:351–4. doi: 10.1037/a0022388

20. Fox MC, Ericsson KA, Best R. Do procedures for verbal reporting of thinking have to be reactive? A meta-analysis and recommendations for best reporting methods. Psychol Bull. (2011) 137:316–44. doi: 10.1037/a0021663

21. Smith SG, Vart G, Wolf MS, Obichere A, Baker HJ, Raine R, et al. How do people interpret information about colorectal cancer screening: observations from a think-aloud study. Health Expect. (2015) 18:703–14. doi: 10.1111/hex.12117

22. Johnson AK, Haider S, Nikolajuk K, Kuhns LM, Ott E, Motley D, et al. An mHealth intervention to improve pre-exposure prophylaxis knowledge among young black women in family planning clinics: development and usability study. JMIR Form Res. (2022) 6:e37738.

23. Noushad B, Van Gerven PWM, de Bruin ABH. Twelve tips for applying the think-aloud method to capture cognitive processes. Med Teach. (2024) 46:892–7.

24. Dennison RA, Boscott RA, Thomas R, Griffin SJ, Harrison H, John SD, et al. A community jury study exploring the public acceptability of using risk stratification to determine eligibility for cancer screening. Health Expect. (2022) 25:1789–806. doi: 10.1111/hex.13522

25. Braun V, Clarke V. Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qual Psychol. (2022) 9:3–26. doi: 10.1037/qup0000196

26. Roberts K, Dowell A, Nie JB. Attempting rigour and replicability in thematic analysis of qualitative research data; a case study of codebook development. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2019) 19:66. doi: 10.1186/s12874-019-0707-y

27. Taylor LC, Dennison RA, Usher-Smith JA. Public acceptability and anticipated uptake of risk-stratified bowel cancer screening in the UK: an online survey. Prev Med Rep. (2024) 48:102927. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2024.102927

28. Okan Y, Petrova D, Smith SG, Lesic V, Bruine de. Bruin W. How do women interpret the NHS information leaflet about cervical cancer screening? Med Decis Mak. (2019) 39:738–54. doi: 10.1177/0272989X19873647

29. Angelova N, Taylor L, McKee L, Fearns N, Mitchell T. User testing a patient information resource about potential complications of vaginally inserted synthetic mesh. BMC Womens Health. (2021) 21:35. doi: 10.1186/s12905-020-01166-4

30. Jallow M, Black G, van Os S, Baldwin DR, Brain KE, Donnelly M, et al. Acceptability of a standalone written leaflet for the national health service for England targeted lung health check programme: a concurrent, think-aloud study. Health Expect. (2022) 25:1776–88. doi: 10.1111/hex.13520

31. Barratt A, Jørgensen KJ, Autier P. Reform of the national screening mammography program in France. JAMA Intern Med. (2018) 178:177–8. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.5836

32. UK National Screening Committee. Criteria for a population screening programme (2024). Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/evidence-review-criteria-national-screening-programmes/criteria-for-appraising-the-viability-effectiveness-and-appropriateness-of-a-screening-programme (accessed October 14, 2024).

33. Trevena LJ, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Edwards A, Gaissmaier W, Galesic M, Han PK, et al. Presenting quantitative information about decision outcomes: a risk communication primer for patient decision aid developers. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. (2013) 13(Suppl 2):S7. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-13-S2-S7

34. Fischhoff B. Brewer NT, Downs JS, editors. Communicating Risks and Benefits: An Evidence-Based User's Guide [Internet]. Maryland: Food and Drug Administration (FDA), US Department of Health and Human Services (2011). Available online at: https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=lLA2vrcQN_AC&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=Communicating+Risks+and+Benefits:+An+Evidence-Based+User%E2%80%99s+Guide.&ots=iYfDuQWgpl&sig=SMszPCF8SeMLBOA8O2ah_Z_l8Hw#v=onepage&q=Communicating%20Risks%20and%20Benefits%3A%20An%20Evidence-Based%20User%E2%80%99s%20Guide.&f=false (accessed January 28, 2025).

Keywords: bowel cancer, cancer, screening, risk, risk stratification, think aloud

Citation: Taylor LC, Dennison RA and Usher-Smith JA (2025) Incorporating information about risk stratification into a bowel cancer screening information leaflet: a think aloud study and user testing process. Front. Cancer Control Soc. 3:1520693. doi: 10.3389/fcacs.2025.1520693

Received: 31 October 2024; Accepted: 14 April 2025;

Published: 09 May 2025.

Edited by:

Christian Von Wagner, University College London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Jessica Thompson, RTI International, United StatesHarriet Quinn-Scoggins, Cardiff University, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2025 Taylor, Dennison and Usher-Smith. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lily C. Taylor, bGN0NDZAbWVkc2NobC5jYW0uYWMudWs=

Lily C. Taylor

Lily C. Taylor Rebecca A. Dennison

Rebecca A. Dennison Juliet A. Usher-Smith

Juliet A. Usher-Smith