- 1Department of Health Sciences, Lund University, Lund, Sweden

- 2School of Social Work, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel

Background: Cancer care for individuals with intellectual disabilities (ID) is challenging, with evidence of disparities, late diagnoses, and overlooked experiences of the individuals in question.

Aim: To explore how individuals with concomitant ID and cancer experience the illness and navigate cancer care trajectories and everyday life from perspectives of themselves, their relatives and professionals.

Method: A qualitative systematic literature review was conducted across the databases PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL Complete, ERIC, SocINDEX, PsycInfo, and Scopus, supplemented by a final search in Google Scholar. All studies were screened and selected in Covidence according to predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The review included 16 publications, registered in PROSPERO (CRD420251042718) and followed the PRISMA guidelines. The quality of the included publications was assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist for qualitative research. Data extraction was followed by a descriptive summary and a qualitative thematic analysis, inspired by Braun and Clarke.

Results: The studies, conducted in four countries, represented the voices of 22 individuals with ID and cancer and, in addition, perspectives of 11 relatives and 32 professionals. Data was synthesized in four themes: “Emotional responses to having cancer,” “Coping with cancer - life went on,” “Balancing the right to information and the limits of communication abilities,” and “Encountering death in various ways.” Individuals with ID responded to cancer and related challenges in diverse ways, yet they often demonstrated an ability to live in the moment as a coping strategy and strength in living and dying with cancer. They received information to varying degrees about their cancer diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis, while also having differing capacities to understand and process this information. Experiences of cancer in others contributed to their understanding of their own condition.

Conclusion: Individuals with ID responded to cancer and its trajectory in varied ways. Many faced challenges in interactions with healthcare professionals, often due to communication barriers. Everyday routines and “living in the moment” served as important coping strategies. All 22 voices of individuals with ID represented in the studies came from the United Kingdom. Worldwide, future research should actively involve this population throughout the process.

Systematic review registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD420251042718, PROSPERO: CRD420251042718.

Introduction

A recent study found that in 2019 there were 107.62 million individuals with intellectual disabilities (ID) worldwide (1.74%). Significant regional inequalities exist in the prevalence and trends of ID across countries (1). ID is defined as a condition that occurs before the age of 22 and features major limitations in intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior (2, 3). In recent decades, life expectancy for people with ID has increased significantly in developed countries. The extension of life expectancy concomitantly elevates the risk of developing various forms of diseases, including cancer (4, 5). Therefore, the percentage of individuals with ID receiving a cancer diagnosis is progressively on the rise (5). Moreover, research shows that compared to the general population, people with ID experience more mental and physical morbidity and have higher mortality rates (6).

A recent study found that cancer survival rates were poorer among individuals with ID compared to the general population (7). However, Banda et al. (4) demonstrate that the overall cancer risk among individuals with ID is either lower than or comparable to that of the general population. Nevertheless, certain conditions, such as Down syndrome, specific genetic mutations, and premature aging presented in this population, may increase the risk of certain types of cancer (4, 8).

Cancer care is understudied among individuals with ID (9). Scant research suggests that individuals with ID encounter disparities throughout the entire range of cancer care (4). Several studies, for example, indicate that this group of individuals experiences disparities in cancer screening (8, 10, 11). Individuals with ID face multiple barriers to cancer screening, including emotional distress, communication challenges, and limited knowledge (12, 13). In addition, significant barriers exist in healthcare accessibility and provision of appropriate accommodations in medical settings (8, 13). Apart from disparities in screening, individuals with ID were often diagnosed at advanced stages of cancer (5, 14, 15). Studies provide examples of key barriers to cancer care for people with disabilities; these include a lack of evidence for making treatment decisions, ableist attitudes among healthcare professionals, erroneous assumptions among healthcare professionals about people with disabilities, such as beliefs about the values or preferences of people with disabilities, inadequate knowledge about the impairment, diagnostic overshadowing that entails assuming that symptoms are related to the person's impairment, and failure to anticipate functional implications of cancer treatment (8, 16, 17). There is very little research on cancer treatment and outcomes in people with disabilities or ID (8, 9, 13). Evidence suggests that in several cases treatment is withheld or modified based on subjective opinion of professionals (9). Boonman et al. (18) conclude that individuals with ID are medically vulnerable and may respond differently to standard cancer treatments compared to the general population.

Despite the increased awareness of disparities in cancer care for individuals with ID, investigations into the experiences of individuals with ID remain scarce, and their perspectives have not been adequately represented (19). Cancer patients with ID constitute a ‘transparent population' in terms of research and clinical reports. Moreover, the limited knowledge of their experiences of diagnosis and treatment is from the viewpoint of researchers and clinicians. Their voices, especially the challenges encountered by them and their caregivers in managing cancer, are often not heard (5). This literature review aims to explore how individuals with concomitant ID and cancer experienced the illness and navigated cancer care trajectories and everyday life from perspectives of themselves, their relatives and health- and social care professionals.

Method

This study drew on a qualitative systematic literature review (20), synthesizing findings from studies on cancer and individuals with ID. A thematic analysis was conducted, inspired by Braun and Clarke (21). The review was registered in PROSPERO (registration no CRD420251042718). It followed the PRISMA guidelines (22).

Identifying the research question

Overall, we identified three research questions:

• How did individuals with ID experience their cancer diagnosis and treatment?

• What barriers and facilitators did individuals with concomitant ID and cancer encounter across the cancer care process/spectrum.

• What coping strategies did individuals with concomitant ID and cancer use to navigate and manage their treatment/care courses?

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were: (1) Studies about diagnostic, treatment and care of individuals with ID and cancer, (2) Perspectives of individuals with ID and cancer, their relatives, and health- and social care professionals, (3) Individuals ≥ 18 years old, (4) Qualitative studies or qualitative sub-studies in mixed method studies, (5) Published in Chinese, English, Hebrew, or Scandinavian languages, and (6) Published between 1 January 2005 and 21 May 2025. A 20-year period has been chosen because there is relatively little research in the field. The review excluded the following types of publications: (1) Editorials and commentaries, (2) Systematic literature reviews, (3) Intervention studies, (4) Dissertations and thesis, and (5) Guidelines and recommendations.

Searching, selecting, appraising, and extracting relevant data

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in the PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL Complete, ERIC, SocINDEX, and PsycInfo databases, with the support of an experienced librarian (last search: 21 May 2025). The inclusion and exclusion criteria were guided by the PEO model, Population, Exposure, and Outcome (Table 1), which was chosen for its structured approach to formulating research questions and organizing data in line with qualitative research methodologies (20, 23). The search strategy was developed using the building block approach, structured according to the PEO framework.

Search terms within each PEO block were adapted to meet the specific indexing and search functionalities of each database. A detailed overview of the search strategies is presented in Table 2.

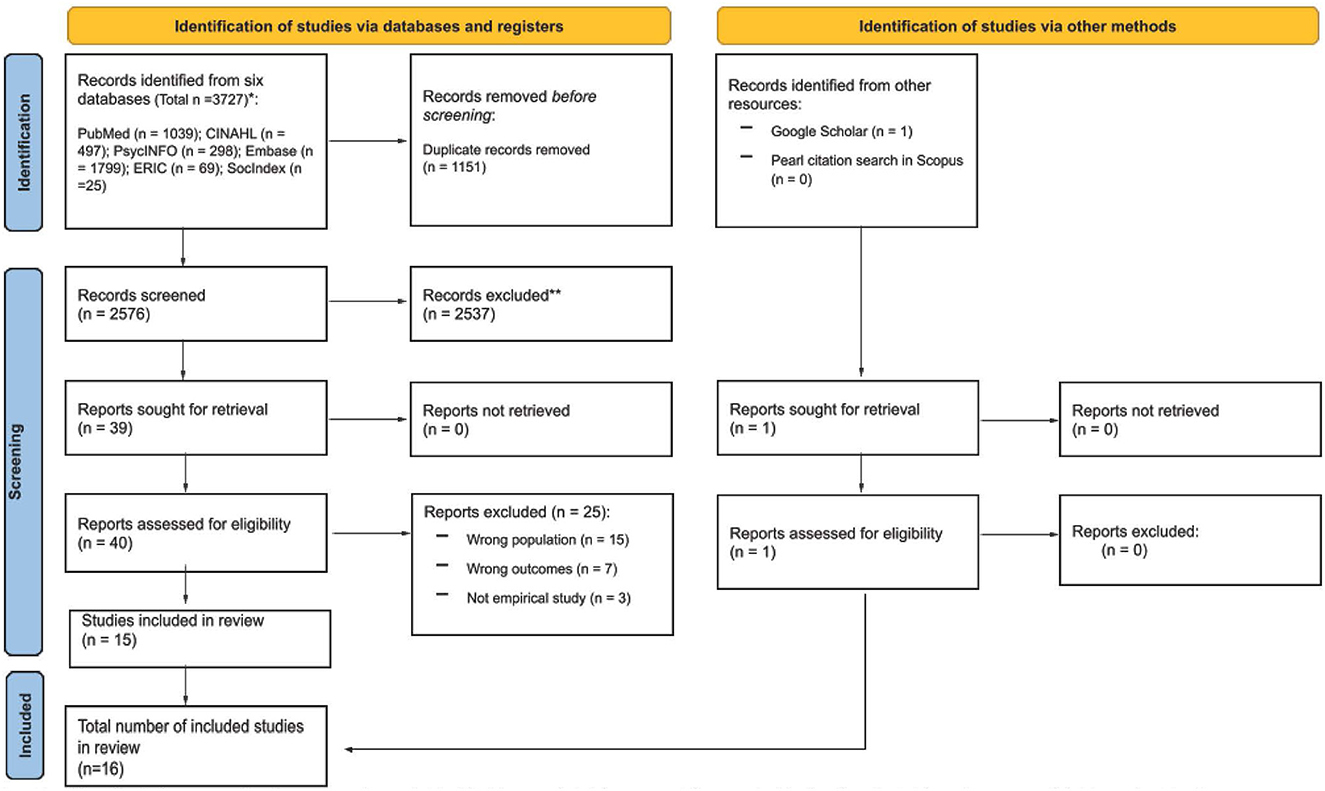

The initial search yielded 3,727 publications, which were imported into Covidence software for the screening process. Two authors (SG and CF) independently screened all records against the eligibility criteria. Discrepancies were initially discussed between them, and unresolved cases were referred to the remaining authors (MC and MS) for consensus. To uncover additional relevant studies, we conducted a citation pearl search in the Scopus database and searched on an academic online search engine, Google Scholar (last searched on 26 May 2025). The study selection process is illustrated in a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases, registers and other sources. Flowchart displaying the study selection process. Records from databases and other sources are identified, with duplicates removed. Records screened total two thousand five hundred seventy-six, with two thousand five hundred thirty-seven excluded. Forty reports are assessed, fifteen included in review. Total included studies: sixteen. Source: (73). This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

The following information was extracted from the included publications: authorship, geographical location, journal, study period, design, sample size, target group and context, theoretical framework or concepts, key findings, and reported limitations. A selection of this data is presented in Table 3. All extracted data were reviewed for accuracy by SG, MC and CF. The CASP qualitative checklist was used to systematically assess the quality of included studies by SG and MC, ensuring the review's findings were grounded in credible evidence and methodological rigor (24). Any discrepancies were discussed in the author team until consensus was reached. Endorsed by the Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group (25), the ten-question tool evaluated aspects such as study aims, design, recruitment, data collection and analysis, and overall significance. This appraisal ensured the evidence was robust and relevant to the research question.

Analytical strategy

The data analysis strategy comprised two components: a descriptive summary, presented as “Characteristics of the studies,” and a reflexive thematic analysis inspired by the approach developed by Braun and Clarke (21). The analysis focused on the results sections of the included publications, which were systematically coded. These initial codes were then reorganized in relation to the review's overarching aim and research questions. Preliminary themes were generated by identifying patterns of similarity and difference across the coded data, with similar codes grouped together into broader thematic categories. Theme development was an iterative and collaborative process among three of the authors (SG, MC, CF). Themes were refined through repeated engagement with the empirical material, the initial codes, and the research question to ensure conceptual coherence and empirical grounding (2022). Each theme was subsequently defined, reviewed, and named to ensure clarity, internal consistency, and analytical rigor. The final themes were “Emotional responses to having cancer,” “Coping with cancer - life went on,” “Balancing the right to information and the limits of communication abilities,” and “Encountering death in various ways.” They were narratively described by synthesizing the results of the included studies to address the aim of the review.

Results

Characteristics of the studies

In total, 16 publications based on seven studies were included. One study resulted in nine included publications (26–33), and another study resulted in two included publications (34, 35). The remaining five publications were based on five corresponding studies. The publications originated from the United Kingdom (13), the Netherlands (1), the United States of America (1), and Australia (1), see Table 3. The two studies that resulted in more than one included publication, used non-participant observation and semi-structured interviews. However, three of those publications only used selected cases from the entire study as empirical material (27, 28, 30). Two studies used semi-structured interviews (36, 37), two studies were case studies (38, 39) and one study constructed a case based on semi-structured interviews (40). Seven publications used narrative case description (28–30, 38, 39), four publications used grounded theory (31–33, 37), three publication used thematic analysis (34–36), one used narrative analysis (40) and one publication had an unknown analytical strategy (26).

The seven studies represented by the 16 publications included a total of 22 individuals with ID and cancer, 11 relatives, 32 health- and social care professionals, inclusive paid caregivers. The current review did not include data from the studies related to four individuals with ID (not cancer), two volunteers, and seven relatives and 16 health and social care professionals related to six deceased individuals with ID (not cancer). The current literature review only focused on the results related to individuals with ID and cancer.

Most of the studies primarily focused on individuals with ID and cancer and their experiences and care trajectories. However, Moore and Kates' (39) study focussed healthcare practices in encounters with individuals with ID and cancer, nonetheless parts of the publication revealed the patient's experiences hence it was included (39). Bekkema et al. (36) focussed on the end of life of people with ID where significant others of deceased people with ID narrated about the situations. Six out of 12 cases were about individuals with ID and cancer, and these cases were included in the current literature review (36). Nine publications were published in specific disability journals, five were published in oncological and palliative care journals (31, 32, 35, 37, 39), one in journal of general practice (31) and one in a general nursing journal (33).

All included publications demonstrated appropriate methodological rigor based on the results of the CASP checklist (24), see Table 4.

Emotional responses to having cancer

From the perspective of relatives, individuals with ID lived dependently, with others making key decisions about treatment, living arrangements, pain relief, and information about cancer diagnosis or prognosis. Their cancer experiences were shaped by others, often without full knowledge or agency (30, 31). Some individuals with ID experienced that cancer was inevitably fatal from family members or celebrities who had died of cancer (26, 27, 32). From the perspectives of relatives and professionals, some individuals with ID did not fully comprehend the seriousness of the illness, which allowed them to remain undisturbed and in good spirits (36, 37). Others recognized their situation and some deliberately chose to endure fear and restlessness rather than accept medication or hospitalization, despite professionals' and relatives' wishes for active treatment (36). From the perspective of some individuals with ID and cancer, many struggled to make sense of what was happening to their bodies, and this confusion became a central challenge of living with cancer. Some individuals with ID also expressed their confusion (29, 32). Others reacted to their cancer disease and deteriorating health with passive acceptance of their condition, marked by a lack of inquiry, and showing minimal expressions or behavioral signs of distress, anxiety or any other emotional reactions (30, 32, 37, 40). Some, particularly among those with mild ID who could express themselves, had only a limited understanding of their situation and felt powerless to ask for or seek information (33, 36, 37). Some individuals with ID denied their disease, or consciously chose to disconnect (37). Others had a high level of distress and anxiety during the cancer care trajectory (31–33, 38). From the perspective of professionals and relatives, routine medical procedures, including blood pressure monitoring and blood tests, and chemotherapy required general anesthesia for certain individuals with ID, as such interventions frequently triggered severe distress and agitation (38). Other individuals with ID experienced such intense worry that it disrupted their sleep or left them confused about why they were not being admitted to hospital (31).

Some individuals with ID and cancer had the ability to hide their distress (31) and symptoms (28) as a result of long-term socialization of individuals with ID to suppress negative emotions such as distress or anger, and the perceived requirement of carers to behave in a ‘good' and compliant way (28, 33, 37, 40). From relatives' and individuals with ID's perspectives, some individuals with ID mirrored the emotional responses of relatives, who themselves attempted to hide feelings of sorrow or concern (28, 37). In addition, some individuals nearing death concealed their emotions to avoid burdening relatives and professionals (28, 31, 33, 37). Others expressed their emotions in different ways. For example, some individuals with ID who had limited spoken language communicated their immediate needs and enjoyed life through sensory experiences like water, music, and bright lights (26). Despite having cancer, they often appeared unconcerned about their prognosis. From the perspectives of professionals and relatives, cheerful attitudes might protect them from distress and worries for the future (26, 32). However, some individuals experienced severe cancer pain intensified by existential distress, even when they appeared cheerful (26, 31). Others experienced that confusions intensified as their physical abilities declined, for example, with the loss of the ability to walk or significant weight loss (28, 31, 32)

In addition, everyday activities such as travel, meals, and hygiene became emotionally challenging during their cancer care trajectories (28). Some of the individuals with ID and cancer expressed feelings of loneliness, both in physical sense of being alone and in emotional sense of lacking someone to share their fears and struggles with (27, 31, 33).

Coping with cancer - life went on

Individuals with ID expressed a strong focus on the present moment and attempted to cope with cancer by engaging in familiar daily activities such as listening to music, caring for pets, attending day centers, or enjoying small pleasures like food (27, 29, 30, 33, 39). Often, their embodied ability to live in the present moment helped protect them from the harmful effects of worry. Individuals with ID, particularly those with more severe disabilities, already possessed the skill of “living one day at a time” (26, 28, 30, 33). Relatives and professionals also expressed that individuals with ID and cancer continued their everyday life as much as possible (28, 30).

Some individuals with ID and cancer actively employed personal coping strategies, including self-talk for reassurance or speaking to a deceased loved one (e.g., a mother), or drawing strength from religious faith and prayer (27). From the perspective of individuals with ID and cancer, support from relatives played an essential role in allowing them to cope with both treatment periods and end-of-life stages (27, 32, 33). However, some became aware of the burden their helplessness imposed on others and felt concerned about it (28, 33). Often, they valued time with family and offered comfort to others, even while facing their own struggles (28). Some continued the activities they loved and used to do as a main coping strategy during treatment or at the end of life (27, 30, 31, 33). Previous life experiences with illness and death of significant others and the ability to live in the moment supported the coping of individuals with mild to severe ID (27, 32). Cancer brought new experiences of dependency, yet many individuals with ID were already familiar with relying on others, which contributed to their calm acceptance of the situation (30, 32).

Some individuals with ID and cancer found it difficult to cope with bodily changes, such as smells, and treatment side effects, such as hair loss, diarrhea and vomiting (27, 28, 30). It was sometimes followed by a feeling of embarrassment. One example was a person who, after being discharged from hospital, vomited in the street and saw people on a bus looking at him and laughing. He thought they assumed he was drunk (28). From relatives' and professionals' perspectives, individuals with ID and cancer experienced marked decline in physical functioning during treatment, becoming increasingly dependent due to worsening health and, in some cases, immobility. They coped by accepting the assistance they needed (36). For some, cancer served as a turning point that fostered autonomy and assertiveness, as they actively sought information and voiced their needs, encouraged by supportive professionals (40). Others had the ability to make shifts in daily priorities, leading to greater appreciation for small daily joys (27).

Balancing the right to information and the limits of communication abilities

Individuals with severe/profound ID were usually not told their diagnosis, while those with mild/moderate ID were given information but often lacked the full details or adequate support needed to understand it (26, 30, 32, 33, 36). Individuals with ID who received information respond to their cancer in various ways. Some asked for taking part in others' cancer stories that made them laugh and cry, told in a simple and understandable way (28). Other individuals with ID received full disclosure about their cancer (26, 27, 32). One example was a woman with breast cancer, fully informed by her general practitioner, chose to decline further treatment because she hated hospitals and needles (26). Another example was a young man with testicular cancer, who was informed about chemotherapy and accepted treatment, requested by his mother, on behalf of him (38). From the perspective of professionals and relatives, the young man was primarily reliant on a wheelchair, exhibited minimal verbal communication, and lacked an effective means of expressing pain. Nonetheless, he could use simple signs and gestures. Family members and professionals collaborated to support the use of non-verbal communication tools, mobility aids, bed management, and recommendations for toileting and feeding, to ensure the success of the curative chemotherapy course, carried out under anesthesia (38).

From the perspective of relatives, individuals with ID had the right to be informed, but it was usually the relatives who received the prognosis first (34, 36, 38). In cases of severe ID, their understanding was often unclear, making it difficult to assess their need for information. Sometimes, no communication occurred at all, as it was seen as impossible due to low cognitive ability (36). Some lacked the verbal ability to express their understanding or ask questions, while others either received answers that obscured the truth or chose not to ask at all (32, 33). An example, from the professionals' perspective, was a person who was not concerned about what the doctor would say or what might happen to him. Instead, he was more worried that the appointment was taking too long and interfering with his usual routines, like watching videos or having lunch on time (32). Only a few posed follow-up questions to their doctor and received support in understanding the implications of their diagnosis (33). Communication barriers with healthcare professionals frequently left individuals with ID confused about their health, leading to anxiety in their care experience (33, 37).

The lack of information and use of unfamiliar language in hospitals made some individuals with ID feel scared and confused about what was happening (26, 27, 31, 32, 37). Individuals with ID sometimes misunderstood bad news, interpreting it as good news (32). Some individuals with ID felt supported with information about, for example, radiotherapy and being able to express their own symptoms, such as fatigue, by using a picture book illustrating the treatment and its side effects (35).

Professionals differed in their assessments of how well individuals with ID could understand information about their disease. For example, a general practitioner informed a person that he had cancer but assessed that he did not appear to grasp what was being said. However, afterwards, his caregiver felt able to explain why he was becoming so tired and breathless, interpreting that he understood a little more each time and showed no signs of distress when being told (26). Other individuals with ID fully understood the necessity of being treated with chemotherapy to be cured, where life experiences with family members having cancer and receiving treatment also supported their understanding (27). Relatives and professionals observed that, with time and support, individuals with ID and cancer could express what mattered to them and adapt to changes, underscoring the importance of recognizing their communicative abilities (36).

Encountering death in various ways

From professionals' perspective, some individuals with mild ID could express and revise their last wishes during their cancer journey, often with support by, for example, completing a book outlining preferences such as the funeral location or coffin color (36). In contrast, from professionals' perspective, individuals with severe ID often had unclear or unknown end of life wishes and were not involved in end-of-life decisions such as starting life-prolonging treatment or moving to another place (29, 32, 36). Decisions were thus made by relatives and professionals based on what they believed to be the best interests for individuals with severe ID and cancer (32). Wishes were sometimes discussed beforehand, but in other cases, individuals with ID and cancer were only informed after the decision, such as the use of a feeding tube or relocation (29–31, 33, 36). Others were involved but did not understand the information, while some understood that they were approaching death based on their previous life experiences (26, 29, 32, 39). Relatives and professionals observed that individuals with severe ID showed a greater desire and ability to express themselves during the final stage of life than in earlier stages of cancer. Through life, some had learned to conceal pain and distress. For example, one man with a history of childhood suffering from foot deformities rarely complained, even in the final, weakening stages of cancer (33).

From the perspective of relatives and professionals, when communication was possible, some individuals with ID and cancer shared concrete and specific end-of-life wishes, such as the preference of place to die. One example was a man with cancer who expressed that it was most valued to him to stay at home rather than in a hospital. He wanted to be with his friends and favorite fish, and his wish was fully supported by family and professionals (39). According to relatives and professionals, some individuals with ID and cancer also remained cheerful throughout their terminal illness and experienced a good death. During this life phase, their everyday life was supported to continue familiar and meaningful activities, such as being surrounded by lights and music, attending the day center, and meeting friends (30, 31, 33, 39). From the professionals' perspective, supporting a good death for individuals with ID involved various approaches, which not only met medical needs but also preserved comfort and familiarity in their everyday lives during the final phase (26, 36, 39). For example, although some individuals with ID wished to and died in their own apartments/residential homes (31–33, 36), this was not always feasible from a professional perspective, because a transition from hospital back to home could cause additional suffering, including sadness or depression (36). To help individuals feel more comfortable, healthcare professionals sometimes hung pictures of the person's apartment in the hospital room or returned the body to their apartment after death, maintaining a connection with their everyday environment and respecting the spirit of the deceased (36). From professionals' perspectives, individuals with ID and cancer were often relocated to nursing homes or hospices during the final phase of life to ensure safe, reassuring daily comfort and care, while also protecting the wellbeing of cohabitants in residential homes (31–33). In other cases, professionals supported individuals' wishes to die at home, either alone or with care from relatives and staff, based on what was feasible and perceived as respectful to the person's familiar routines and preferences (31, 39). Others died at hospital (31, 32). There were also examples of persons who died in an ambulance (30, 31). Some individuals with ID appeared to face their final decline with calm acceptance and grace (32), others were screaming loudly (33) or expressed intolerable physical and emotional pain (31).

Discussion

The discussion will focus on three main findings, namely (1) individuals with ID often demonstrated an ability to live in the moment, which proved to be a strength in both living with and dying from cancer, (2) the disconnect between the right to receive information about cancer diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis, and the diverse capacities to comprehend it, and (3) only the voices of 22 individuals with ID and cancer have been heard in the included studies. Furthermore, the strengths and limitations of the study's method will be discussed.

The results pointed to the fact that individuals with ID often demonstrated an ability to live in the moment as a coping strategy and strength in living and dying with cancer. This present-moment awareness involves fully engaging with and appreciating the current experience, without being distracted by past regrets or future concerns. Today, this ability is often associated with mindfulness (41). It seems that individuals with ID may have mindfulness as an incorporated way of living, in contrast to the modern medico-psychological trend of ‘cultivating' mindfulness as a therapeutic technique for managing biopsychosocial conditions (42, 43). Living in the moment serves as an effective coping strategy for individuals facing life-threatening diseases, often achieved through small, everyday pleasures that added meaning to their lives (44). Research suggests that maintaining daily routines can serve as a source of strength, helping individuals with ID to stay focused on the present moment, preserve a sense of self and autonomy, and promote wellbeing in the context of advanced disease, also in the end of life (45). This calls for a shift away from a medico-deficit-based view of individuals with ID toward recognizing and building on individuals existing strengths and resources. However, implementing such approaches in practice is challenging, as individuals with ID and their relatives often experience tensions between supporting independence through daily routines and securing appropriate medical care (46). Structured support systems, on which many rely, often lack flexibility to accommodate individualized routines (47). This highlights the importance of developing flexible, person-centered approaches in healthcare that accommodate and support individuals with ID living and dying with cancer.

Furthermore, the results revealed a disconnect between individuals' right to receive information about a cancer diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis, and their diverse capacities to comprehend it. Some individuals were fully informed and understood. Others received only partial information and/or had limited understanding. In some cases, individuals with ID were not informed at all. Frequently, relatives received information before the patient, even though it was the patient whom the matter directly concerned. Consistent with current findings, research shows that many individuals with ID experience stress in healthcare settings due to communication barriers and difficulty processing medical information. Often, they struggle to report symptoms or recall visits and some express discomfort through behaviors like screaming, aggression, or hyperactivity (48). Inadequate provision of information and understanding can contribute to poorer symptom control, reduced access to palliative care, and increased risk of a painful or undignified death among individuals with ID (49, 50). Therefore, withholding information about diagnoses, treatment, and prognosis from individuals with ID must be considered unethical and paternalistic in healthcare. Similarly, informing relatives without involving individuals with ID and cancer must also be regarded as unethical and paternalistic, unless the person has given their consent (48, 51). Such practices fundamentally contradict human rights. Human rights and healthcare for people with ID are deeply interconnected. The right to the highest attainable standard of health, free from discrimination because of disability, is a fundamental human right, firmly established in international human rights law, including the Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities (CRPD) (52). The CRPD obliges States Parties to ensure that persons with disabilities have access to the same range, quality, and standard of healthcare as others. It also underscores the importance of bodily autonomy, which is the right to make informed decisions about one's own body and health, including access to information, services, and the means to act on these decisions without discrimination, coercion, or violence. The current literature review calls for future research on inclusive information practices that ensure not only access to information but also comprehension. As Bateson (53) noted, information is a difference that makes a difference, pointing to that information is only given when it is understood.

Research reveals that relatives often decide whether to involve individuals with ID during cancer treatment based on their perceptions of that person's capacity or incapacity (18). However, individuals with ID should have the right to decide how much information they wish to receive. Relatives may sometimes be less willing to disclose this information, possibly driven by the intention of ‘protecting' individuals with ID, or they do not know how to effectively communicate the information (54). Healthcare professionals are accustomed to interacting with people who have communication difficulties, such as individuals with stroke, aphasia, brain tumors, deafness, or dementia, as well as those who speak other languages, such as immigrants and refugees. All these communication experiences and already well-known techniques can also be applied when engaging with individuals with ID. Research suggests asking individuals with ID to clarify questions, using visual aids or pictures, clearly explaining options, and discussing possible outcomes could support informed understanding and engagement (55). To help individuals with ID to understand healthcare information, studies show the importance of involving relatives to help translate and adapt information in ways that are understandable for individuals with ID. However, this requires that healthcare professionals are also attentive to the distinct needs of relatives, such as trustworthiness and clear information, in their encounters with individuals with ID and their relatives (56, 57).

Only the voices of 22 individuals with ID and cancer have been heard in the included studies, whereas all were from the United Kingdom and the newest publication was from 2016. Many research projects exclude people with ID, especially those with moderate to severe ID, due to research design, capacity issues, and inadequate inclusion methods (58, 59). The voices of individuals with ID and cancer remain significantly underrepresented in research. A clear knowledge gap persists regarding their lived experiences, particularly when expressed directly by the individuals themselves. This silence calls for urgent efforts to amplify their narratives and promote inclusive research practices. A similar lack of representation is evident among individuals with severe mental illness who also face cancer diagnoses (60, 61). Exclusion of these individuals from health research is often driven by pervasive stereotypes and paternalistic attempts to protect those considered as ‘vulnerable.' It is important not to diagnose groups of people as vulnerable, but instead to focus on the fact that people are often capable and resourceful, though they can be in vulnerable situations, such as when facing cancer, approaching death, or experiencing loss (62, 63). Furthermore, many researchers lack the necessary knowledge and skills to effectively include these individuals in studies. Healthcare professionals and researchers often underestimate the capacity of people with ID to understand and assess their own health, express needs, and engage in research, either independently or with appropriate support (58, 59). However, newer studies about cancer prevention/screening include individuals with ID (64–66). The current results demonstrated that individuals with ID could participate in research, when supported by relatives and/or accommodations. This aligns with broader movements in Western healthcare systems toward co-production, shared decision-making, and user involvement in both care and knowledge production (67). Participatory research methods that actively involve people with ID can provide deeper insights into their experiences, promote equitable participation, and contribute to improvements in health policy and practice, including information practices (59, 68). However, this method requires resources, trust, and cultural change within research and clinical environments to overcome barriers and ensure that research and care become fair, inclusive, and effective (59, 69).

The current literature review has strengths and limitations. This review was carried out in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines, which ensure a systematic, transparent, and rigorous reporting of the review methods, thereby facilitating a clear evaluation of its quality (22, 70). Furthermore, the review protocol was pre-registered on PROSPERO, allowing public access to the original plan and enabling comparison with the completed manuscript. This pre-registration strengthens the transparency and credibility of the review process (71). Moreover, an experienced university librarian supported the systematic literature search process, which was supplemented by a final Google Scholar search, to ensure the retrieval of the most relevant and comprehensive studies aligned with the review's aim and research questions. This collaborative approach contributed to a rigorous and transparent search process. All articles that did not clearly distinguish between individuals with ID who have cancer and those without cancer were excluded. This approach ensures that the results specifically represent the group of individuals with concomitant ID and cancer. However, it also means that relevant information about this population involved in broader studies may have been missed in this review. Throughout the screening, data extraction, and analysis phases, the authors engaged in regular discussions and critical evaluations, thereby strengthening the reliability and credibility of the results. The quality of the included studies was appraised using the CASP qualitative checklist, with all studies rated as high quality, supporting the trustworthiness and relevance of the review findings. Nonetheless, the CASP tool has limitations, notably its omission of criteria assessing the studies' underlying theoretical, ontological, and epistemological frameworks, which are important aspects for a thorough quality evaluation (25). However, this literature review includes studies with low levels of evidence according to the evidence hierarchy (72), primarily due to their case study formats, which represents a limitation. Nevertheless, the current review encompasses all relevant studies identified and provides a valuable synthesis of an under-researched area within healthcare about individuals with ID facing cancer.

Conclusion

The current literature review revealed that individuals with ID responded to cancer and its challenges in diverse ways. Everyday routines often provided an important source of stability and functioned as a coping resource to preserve a sense of self and control when encountering uncertainty in living with cancer. Individuals with ID also showed an ability to live in the moment, which served as both a coping strategy and a source of strength throughout their cancer journey. Individuals with ID developed their understandings of cancer and their conditions through personal experiences such as seeing relatives having cancer or public figures. They received information about their diagnosis, treatment and prognosis to varying extents, influenced not only by differences in individuals with ID's capacities to understand and process information, but also by assumptions held by relatives and professionals about their (in)abilities to handle such information. These assumptions often resulted in limited information being provided to individuals with ID and cancer, which failed to respect their autonomy and rights to know. Future research must explore effective ways for relatives and professionals to communicate cancer information to individuals with ID that respects their autonomy and human rights to be informed and involved in decisions about their own cancer care. Future research should also focus on developing strategies for supporting person-centered routines within structured care systems that accommodate and empower individuals with ID to navigate cancer care trajectories.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SG: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MC: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CF: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Krister Aronsson (Librarian at support for research and learning, Library and ICT, Faculty of Medicine, Lund University) for his dedicated assistance and work in designing and performing the literature searches.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Nair R, Chen M, Dutt AS, Hagopian L, Singh A, Du M. Significant regional inequalities in the prevalence of intellectual disability and trends from 1990 to 2019: a systematic analysis of GBD 2019. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. (2022) 31:e91. doi: 10.1017/S2045796022000701

2. American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD). Deifining Criteria for Intellectual Disability. (2025). Available online at: https://www.aaidd.org/intellectual-disability/definition

3. American Psychiatric Association. What is Intellectual Disability? (2025). Available online at: https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/intellectual-disability/what-is-intellectual-disability

4. Banda A, Naaldenberg J, Timen A, van Eeghen A, Leusink G, Cuypers M. Cancer risks related to intellectual disabilities: a systematic review. Cancer Med. (2024) 13:e7210. doi: 10.1002/cam4.7210

5. Satgé D, Kempf E, Dubois JB, Nishi M, Trédaniel J. Challenges in diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer in people with intellectual disabilities: current state of knowledge. Lung Cancer Int. (2016) 2016:6787648. doi: 10.1155/2016/6787648

6. Reppermund S, Srasuebkul P, Dean K, Trollor JN. Factors associated with death in people with intellectual disability. J Appied Res Intellect Disabil. (2020) 33:420–9. doi: 10.1111/jar.12684

7. Hansford RL, Ouellette-Kuntz H, Griffiths R, Hallet J, Decker K, Dawe DE, et al. Breast (female), colorectal, and lung cancer survival in people with intellectual or developmental disabilities: a population-based retrospective cohort study. Can J Public Health. (2024) 115:332–42. doi: 10.17269/s41997-023-00844-8

8. Iezzoni LI. Cancer detection, diagnosis, and treatment for adults with disabilities. Lancet Oncol. (2022) 23:e164–73. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00018-3

9. The Lancet Oncology. Intellectual and developmental disabilities-an under-recognised driver of cancer mortality. Lancet Oncol. (2024) 25:411. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(24)00146-3

10. Merten JW, Pomeranz JL, King JL, Moorhouse M, Wynn RD. Barriers to cancer screening for people with disabilities: a literature review. Disabil Health J. (2015) 8:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2014.06.004

11. Murphy KA, Stone EM, Presskreischer R, McGinty EE, Daumit GL, Pollack CE. Cancer screening among adults with and without serious mental illness: a mixed methods study. Med Care. (2021) 59:327–33. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001499

12. Chan DNS, Law BMH, Au DWH, So WKW, Fan N. A systematic review of the barriers and facilitators influencing the cancer screening behaviour among people with intellectual disabilities. Cancer Epidemiol. (2022) 76:102084. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2021.102084

13. Stirling M, Anderson A, Ouellette-Kuntz H, Hallet J, Shooshtari S, Kelly C, et al. A scoping review documenting cancer outcomes and inequities for adults living with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities. Eur J Oncol Nurs. (2021) 54:102011. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2021.102011

14. Hogg J, Tuffrey-Wijne I. Cancer and intellectual disability: a review of some key contextual issues. J Appied Res Intellect Disabil. (2008) 21:509–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3148.2008.00422.x

15. Tosetti I, Kuper H. Do people with disabilities experience disparities in cancer care? A systematic review. PLoS ONE. (2023) 18:e0285146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0285146

16. Hotez E, Rava J, Russ S, Ware A, Halfon N. Using a life course health development framework to combat stigma-related health disparities for individuals with intellectual and/or developmental disability (I/DD). Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. (2023) 53:101433. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2023.101433

17. Pelleboer-Gunnink HA, Van Oorsouw WMWJ, Van Weeghel J, Embregts PJCM. Mainstream health professionals' stigmatising attitudes towards people with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review. Intellect Disabil Res. (2017) 61:411–34. doi: 10.1111/jir.12353

18. Boonman AJ, Cuypers M, Leusink GL, Naaldenberg J, Bloemendal HJ. Cancer treatment and decision making in individuals with intellectual disabilities: a scoping literature review. Lancet Oncol. (2022) 23:e174–83. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00694-X

19. Flynn S, Hulbert-Williams N, Hulbert-Williams L, Bramwell R. Psychosocial experiences of chronic illness in individuals with an intellectual disability: a systematic review of the literature. J Intellect Disabil. (2015) 19:178–94. doi: 10.1177/1744629514565680

20. Bettany-Saltikov J, McSherry R. How to do a Systematic Literature Review in Nursing: A Step-by-step Guide. 2nd ed. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Education/Open University Press (2016).

21. Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide. London: SAGE (2022). doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-69909-7_3470-2

22. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. (2021) 10:89. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4

23. Khan KS, Kunz R, Kleijnen J, Antes G. Systematic Reviews to Support Evidence-Based Medicine: How to Review and Apply Findings of Healthcare Research (2nd ed). London: The Royal Society of Medicine Press Limited (2004).

24. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Qualitative Checklist. Oxford (2018). Available online at: https://caspuk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (Accessed August 29, 2025).

25. Long HA, French DP, Brooks JM. Optimising the value of the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) tool for quality appraisal in qualitative evidence synthesis. Res Methods Med Health Sci. (2020) 1:31–42. doi: 10.1177/2632084320947559

26. Bernal J, Tuffrey-Wijne I. Telling the truth–or not: disclosure and information for people with intellectual disabilities who have cancer. Int J Disabil Hum Dev. (2008) 7:365–70. doi: 10.1515/IJDHD.2008.7.4.365

27. Cresswell A, Tuffrey-Wijne I. The come back kid: I had cancer, but I got through it. Br J Learn Disabil. (2008) 36:152–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3156.2008.00515.x

28. Tuffrey-Wijne I, Davies J. This is my story: I've got cancer. ‘the veronica project': an ethnographic study of the experiences of people with learning disabilities who have cancer. Br J Learn Disabil. (2007) 35:7–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3156.2006.00421.x

29. Tuffrey-Wijne I. Am I a good girl? Dying people who have learning disabilities. End Life Care. (2009) 3:35–9. doi: 10.1136/eolc-03-01.5

30. Tuffrey-Wijne I, Curfs L, Hollins S. Providing palliative care to people with intellectual disabilities who have cancer. Int J Disabil Hum Dev. (2008) 7:379–84. doi: 10.1515/IJDHD.2008.7.4.379

31. Tuffrey-Wijne I, Bernal J, Hubert J, Butler G, Hollins S. People with learning disabilities who have cancer: an ethnographic study. Br J Gen Pract. (2009) 59:503–9. doi: 10.3399/bjgp09X453413

32. Tuffrey-Wijne I, Bernal J, Hollins S. Disclosure and understanding of cancer diagnosis and prognosis for people with intellectual disabilities: findings from an ethnographic study. Eur J Oncol. (2010) 14:224–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2010.01.021

33. Tuffrey-Wijne I, Bernal J, Hubert J, Butler G, Hollins S. Exploring the lived experiences of people with learning disabilities who are dying of cancer. Nurs Times. (2010) 106:15–8.

34. Jones A, Tuffrey-Wijne I, Bernal J, Butler G, Hollins S. Meeting the cancer information needs of people with learning disabilities: experiences of paid carers. Br J Learn Disabil. (2007) 35:12–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3156.2006.00400.x

35. Tuffrey-Wijne I, Bernal J, Jones A, Butler G, Hollins S. People with intellectual disabilities and their need for cancer information. Eur J Oncol. (2006) 10:106–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2005.05.005

36. Bekkema N, de Veer AJ, Hertogh CM, Francke AL. Respecting autonomy in the end-of-life care of people with intellectual disabilities: a qualitative multiple-case study. Intellect Disabil Res. (2014) 58:368–80. doi: 10.1111/jir.12023

37. Flynn S, Hulbert-Williams NJ, Hulbert-Williams L, Bramwell R. “You don't know what's wrong with you”: an exploration of cancer-related experiences in people with an intellectual disability. Psychooncology. (2016) 25:1198–205. doi: 10.1002/pon.4211

38. Delany C, Diocera M, Lewin J. What is ethically required to adapt to intellectual disability in cancer care? A case study of testicular cancer management. J Intellect Dev Disabili. (2023) 48:456–60. doi: 10.3109/13668250.2023.2220486

39. Moore CM, Kates J. Navigating end-of-life needs for a person with intellectual disabilities and their caregivers. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. (2022). doi: 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000896

40. Martean MH, Dallos R, Stedmon J, Moss D. Jo's story: The journey of one woman's experience of having cancer and a ‘learning disability'. Br J Learn Disabil. (2013) 42:282–91. doi: 10.1111/bld.12072

41. Chems-Maarif R, Cavanagh K, Baer R, Gu J, Strauss C. Defining mindfulness: a review of existing definitions and suggested refinements. Mindfulness. (2025) 16:1–20. doi: 10.1007/s12671-024-02507-2

42. Keng SL, Smoski MJ, Robins CJ. Effects of mindfulness on psychological health: a review of empirical studies. Clin Psychol Review. (2011) 31:1041–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.04.006

43. Zhang D, Lee EKP, Mak ECW, Ho CY, Wong SYS. Mindfulness-based interventions: an overall review. Br Med Bull. (2021) 138:41–57. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldab005

44. Dönmez ÇF, Johnston B. Living in the moment for people approaching the end of life: a concept analysis. Int J Nurs Studies. (2020) 108:103584. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103584

45. Cithambaram K. Preserving self in the face of death and dying: A grounded theory of end-of-life care needs of people with intellectual disabilities. PhD Dissertation. Dublin: Dublin University (2017). Available online at: https://doras.dcu.ie/21630/1/Kumaresan_Cithambaram_2017_PhD_thesis.pdf (Accessed August 29, 2025).

46. Hanlon P, MacDonald S, Wood K, Allan L, Cooper SA. Long-term condition management in adults with intellectual disability in primary care: a systematic review. BJGP Open. (2018) 2:bjgpopen18X101445. doi: 10.3399/bjgpopen18X101445

47. Kaehne A, Beyer S. Person-centred reviews as a mechanism for planning the post-school transition of young people with intellectual disability. Intellect Disabil Res. (2014) 58:603–13. doi: 10.1111/jir.12058

48. Magaña-Gómez JA, Domínguez-Castro FA, Álvarez-Parra IY, Espinoza-Solís L, Angulo-Rojo CE, Castro-Pérez R, et al. Practical considerations for integral approach of people with intellectual disabilities. Revista Mexicana de Neurociencia. (2019) 20:186–93. doi: 10.24875/RMN.19000004

49. Collins K, McClimens A, Mekonnen S, Wyld L. Breast cancer information and support needs for women with intellectual disabilities: a scoping study. Psychooncology. (2014) 23:892–7. doi: 10.1002/pon.3500

50. O'Regan P, Drummond E. Cancer information needs of people with intellectual disability: a review of the literature. Eur J Oncol Nurs. (2008) 12:142–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2007.12.001

51. World Health Organization. Patient Safety Rights Charter. Geneva: World Health Organization (2024). Available online at: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/376539/9789240093249-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (Accessed August 29, 2025).

52. United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. (2006). Available online at: https://www.ohchr.org/en/hrbodies/crpd/pages/conventionrightspersonswithdisabilities.aspx (Accessed December 13, 2006).

54. Samtani G, Bassford TL, Williamson HJ, Armin JS. Are researchers addressing cancer treatment and survivorship among people with intellectual and developmental disabilities in the U.S.? A scoping review. Intellect Dev Disabil. (2021) 59:141–54. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-59.2.141

55. Nijhof K, Boot FH, Naaldenberg J, Leusink GL, Bevelander KE. Health support of people with intellectual disability and the crucial role of support workers. BMC Health Serv Res. (2024) 24:4. doi: 10.1186/s12913-023-10206-2

56. de Kuijper G, Jonker J, Sheehan R, Hassiotis A. A survey on service users' perspectives about information and shared decision-making in psychotropic drug prescriptions in people with intellectual disabilities. Br J Learn Disabil. (2024) 52:350–61. doi: 10.1111/bld.12582

57. van Beurden K, Vereijken FR, Frielink N, Embregts PJCM. The needs of family members of people with severe or profound intellectual disabilities when collaborating with healthcare professionals: a systematic review. Intellect Disabil Res. (2025) 69:1–29. doi: 10.1111/jir.13199

58. Bishop R, Laugharne R, Shaw N, Russell AM, Goodley D, Banerjee S, et al. The inclusion of adults with intellectual disabilities in health research - challenges, barriers and opportunities: a mixed-method study among stakeholders in England. Intellect Disabil Res. (2024) 68:140–9. doi: 10.1111/jir.13097

59. Majid M, Todowede O, Roy A, Jordan G, Rennick-Egglestone S. Time to prioritise the use of participatory research methods for people with iDs. Br J Psychiat. (2025) 21:1–3. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2025.96

60. Glasdam S, Hybholt L, Stjernswärd S. Experiences of everyday life among individuals with co-existence of serious mental illness and cancer - a qualitative systematic literature review. Healthcare. (2023) 11:1897. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11131897

61. Kisely S, Alotiby MKN, Protani MM, Soole R, Arnautovska U, Siskind D. Breast cancer treatment disparities in patients with severe mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychooncology. (2023) 32:651–62. doi: 10.1002/pon.6120

62. Fu C Glasdam S Stjernswärd S and Xu H. A qualitative systematic review about children's everyday lives when a parent is seriously ill with the prospect of imminent death - perspectives of children and parents. Omega. (2025) 91:1169–213. doi: 10.1177/00302228221149767

63. Karidar H, Lundqvist P, Glasdam S. The influence of actors on the content and execution of a bereavement programme: a bourdieu-inspired ethnographical field study in Sweden. Front Public Health. (2024) 12:1395682. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1395682

64. Adolfsson P, Arving C, Lange M. Preventive breast health care, an embarrassing subject for women with intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil. (2025) 15:17446295251326010. doi: 10.1177/17446295251326010

65. Arana-Chicas E, Kioumarsi A, Carroll-Scott A, Massey PM, Klassen AC, Yudell M. Barriers and facilitators to mammography among women with intellectual disabilities: a qualitative approach. Disabil Soc. (2020) 35:1290–314. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2019.1680348

66. Walsh S, Hegarty J, Lehane E, Farrell D, Taggart L, Kelly L, et al. Determining the need for a breast cancer awareness educational intervention for women with mild/moderate levels of intellectual disability: a qualitative descriptive study. Eur J Cancer Care. (2022) 31:e13590. doi: 10.1111/ecc.13590

67. Elwyn G, Nelson E, Hager A, Price A. Coproduction: when users define quality. BMJ Qual SAF. (2020) 29:711–6. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009830

68. Clarke C, Kouroupa A, Royston R, Hassiotis A, Jin Y, Cooper V, et al. “We're all in this together”: patient and public involvement and engagement in developing a new psychosocial intervention for adults with an intellectual disability who display aggressive challenging behaviour. Res Involv Engagem. (2025) 11:20. doi: 10.1186/s40900-025-00675-6

69. Tromans S, Marten R, Jaggi P, Lewin G, Robinson C, Janickyj A, et al. Developing a patient and public involvement training course for people with intellectual disabilities: the leicestershire experience. J Psychosoc Rehabil Ment Health. (2023) 10:411–25. doi: 10.1007/s40737-023-00369-w

70. Garcia-Doval I, van Zuuren EJ, Bath-Hextall F, Ingram JR. Systematic reviews: let's keep them trustworthy. Br J Dermatol. (2017) 177:888–9. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15826

71. Schiavo JH. PROSPERO: an international register of systematic review protocols. Med Ref Serv Q. (2019) 38:171–80. doi: 10.1080/02763869.2019.1588072

72. LoBiondo-Wood G, Haber J. Nursing research: Methods and Critical Appraisal for Evidence-based Practice (10th ed). London: Elsevier (2022).

Keywords: cancer, communication, encounters, experiences, intellectual disabilities, healthcare, qualitative systematic literature review, strategies

Citation: Glasdam S, Cohen M, Soffer M and Fu C (2025) Experiences and strategies of individuals with concomitant intellectual disabilities and cancer: a qualitative systematic literature review. Front. Cancer Control Soc. 3:1659795. doi: 10.3389/fcacs.2025.1659795

Received: 04 July 2025; Accepted: 18 August 2025;

Published: 10 September 2025.

Edited by:

Nick Gebruers, University of Antwerp, BelgiumReviewed by:

Daniel Satge, University of Montpellier, FranceHeleen Leurs, University of Antwerp, Belgium

Copyright © 2025 Glasdam, Cohen, Soffer and Fu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Stinne Glasdam, c3Rpbm5lLmdsYXNkYW1AbWVkLmx1LnNl

†ORCID: Stinne Glasdam orcid.org/0000-0002-0893-3054

Miri Cohen orcid.org/0000-0003-1220-3852

Michal Soffer orcid.org/0000-0001-5713-1130

Cong Fu orcid.org/0000-0002-0312-4266

Stinne Glasdam

Stinne Glasdam Miri Cohen

Miri Cohen Michal Soffer

Michal Soffer Cong Fu

Cong Fu