- 1Evidence Based Practice Unit, Anna Freud National Centre for Children, and Families, London, United Kingdom

- 2Department of Behavioural Science and Health, University College London, London, United Kingdom

- 3Department of Education, University of York, York, United Kingdom

- 4Department of Public Health and Sport Sciences, Exeter Medical School, University of Exeter, Exeter, United Kingdom

- 5Manchester Institute of Education, University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom

- 6Centre for Longitudinal Studies, Social Research Institute, University College London, London, United Kingdom

- 7School of Psychology, Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool, United Kingdom

- 8Department of Allied Health, Social Work and Wellbeing, Edge Hill University, Ormskirk, United Kingdom

- 9Population Health Sciences Institute, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom

- 10School of Health Sciences, University of Dundee, Dundee, United Kingdom

- 11Department for Health, University of Bath, Bath, United Kingdom

- 12MRC Unit for Lifelong Health and Ageing, Population Science and Experimental Medicine, University College London, London, United Kingdom

- 13Department for Clinical, Educational and Health Psychology, University College London, London, United Kingdom

Introduction: There is debate into the impact of universal, school-based interventions to improve emotional outcomes. Previous reviews have only focused on anxiety and depression symptoms, omitting broader internalising symptoms, nor include the proliferation of newer studies which have focused on mindfulness in schools.

Methods: We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis, searching MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials for studies focusing on universal interventions to improve emotional outcomes for young people aged 8–18 until 15/12/2022. The primary focus were post-intervention self-report anxiety, depression and internalising outcomes. We prospectively registered the study with PROSPERO, number (CRD42020189845). Risk of bias was assessed using specially devised tools adopted from Cochrane.

Results: In total, 71 unique studies with a total sample of 63,041 young people met the inclusion criteria. This included 40 studies with 35,559 participants for anxiety outcomes, 50 studies with 49,418 participants for depression outcomes, and 15 studies with 21,473 participants for internalising outcomes. Pupils who received universal school-based interventions had significantly improved anxiety (d = −0.0858, CI = −0.15, −0.02, z = −2.46, p < .01) and depression (d = −0.109, CI = −0.19, −0.03, z = −2.60, p < 0.013), but not internalising outcomes. For anxiety disorders, intervention theory moderated the intervention effectiveness (Q = 24.93, p < 0.001), with CBT principles being significantly more effective than those that applied mindfulness or other/multiple theories.

Discussion: Evidence suggests that universal, school-based approaches for anxiety and depression produce small effect sizes for pupils. We conclude that used as a population health approach, these can have an impactful change on preventing anxiety and depression. However, intervention developers and researchers should critically consider which theories/approaches are being applied, particularly when trying to improve anxiety outcomes.

Systematic Review Registration: PROSPERO CRD42020189845.

Introduction

Epidemiological rates of mental health difficulties in children and young people range between 10% and 20%, with emotional difficulties such as anxiety and depression being the most prevalent (1, 2). Depressive disorders are the third most frequent cause of adolescent disability-adjusted life-years lost, whilst anxiety disorders rank third among the causes of adolescent disability-adjusted life-years lost in High Income Countries (3). With increasing numbers of young people being affected by mental health problems, and international data indicating that more than 60% of those in need do not have access to adequate treatment, youth mental health has become a major public health concern (4). Without input, difficulties can have a significant detrimental effect on physical, social and psychological outcomes in adulthood (5, 6).

Youth mental health services have been experiencing a shift in recent years, putting a greater focus on schools as key providers of mental health provision (7, 8). Considering the amount of time that children and young people spend at school and the existing infrastructure to deliver intervention programmes, schools can be an important setting to deliver different mental health interventions (9, 10). Furthermore, research suggests that school-based mental health provision helps overcome important social and environmental barriers to accessing support, including transport costs, social stigma or family-related factors (11, 12).

School-based interventions have been broadly classified into promotion, prevention or treatment approaches. Promotion programmes aim to proactively increase young people's wellbeing by fostering strengths and competences (13). Preventative interventions primarily aim to prevent mental health problems from arising by targeting known risk and protective factors (14). Interventions in the treatment category address existing difficulties by assessing symptoms and specifically treating them. Furthermore, school interventions can either follow a universal approach being delivered to all pupils, or they are designed as targeted interventions, implemented with specific individuals with known risk factors or already displaying difficulties.

In the UK, a 2013 national survey of schools suggested a clear trend towards reactive interventions, with 71.2% of secondary schools implementing interventions due to children in their school starting to show symptoms or already experiencing some form of mental health problem (15). While universal prevention and promotion interventions offer a number of advantages, including being sensitive to emotional disorders that may develop later in life, being destigmatising, reaching a wide range of children, being cost and time effective, and promoting adaptive coping/resilience across an array of experiences and settings, they have traditionally been underused and undervalued relative to other types of interventions.

More recently, there has been a shift towards the use of universal whole-school prevention interventions (16, 17). By introducing early intervention for all pupils, it is thought that we can effectively “immunise” them from later difficulties (15). This avoids costly screening procedures needed to identify those at-risk, prevents the issue of some at-risk children being missed, and removes the need for the highly trained professionals often required to deliver targeted interventions (18).

Notably, evidence of existing interventions to prevent emotional outcomes such as depression and anxiety symptoms in youth have been mixed. Many previous reviews (19–21) of school-based prevention interventions have found small or modest effect size for anxiety and depressive outcomes which last up to 12 months post intervention. However, a 2019 meta-analysis (14) and corresponding NIHR report (22) concluded that overall, there was limited evidence of universal interventions in schools for reducing depression or anxiety symptoms. Specifically, these studies concluded that in primary school settings, there was weak evidence to suggest interventions incorporating cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) reduced anxiety symptoms. Whilst in secondary school settings, there was some evidence to suggest mindfulness/relaxation and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) reduced anxiety symptoms.

Some limitations exist when interpreting previous findings. Firstly, studies with very small sample sizes (i.e., less than 32 participants per arm) were included (14, 22) which is vulnerable to Type I and Type II errors due to lack of statistical power (23). Secondly, most reviews of interventions for emotional difficulties only include studies utilising measures of anxiety and depression symptoms to determine the effectiveness of an intervention (24). This means that interventions that target wider constructs for emotional difficulties have not adequately been examined and so their effectiveness is not established. Lastly, conclusions about mindfulness interventions have been based on a small number of studies (n = 3). Since these reviews, a number of high-profile studies focusing on this topic area have been published. This warrants further investigation given the increasing interest and rollout of mindfulness in schools to support mental health. In light of these points, we aimed to further investigate the impact of universal, school-based interventions on emotional difficulties in pupils.

Materials and methods

Search strategy and inclusion criteria

For this review and meta-analysis, we developed a search strategy mapping to the PICO criteria (S0) and searched MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials for studies published until 15th December 2022. A detailed search strategy is available in the Supplementary Materials S1, as are definitions for examined constructs (S2). Hand searching of included articles and consultation with experts (n = 9) was also undertaken.

We included studies if they were randomised or quasi-randomised trials of school-based, universal interventions targeting emotional outcomes; anxiety, depression, or internalising symptoms, for young people aged 8–18 years old. This age range was selected to reflect the ages of pupils who could self-report their difficulties. Randomisation could occur at individual and/or class level. We also excluded studies where there were less than 32 participants in at least one arm, as this is needed to detect a one standard deviation difference in improvement with adequate statistical power (80%) and a significance level of 0.05 (25). There were no exclusions on the type, format of intervention delivery method. Searches were restricted to those in English.

We screened articles in two stages. Both first and second stage screening were double screened by at least two researchers (DH, ED, KN, AT, CM, AM, JS, RM, HM, JD) and any disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer. The lead reviewer of this article (DH) checked a 10% sample of records of other reviewer dyads to ensure consistency across screening. We employed a uniform approach to data extraction, using a developed data extraction template (see Supplementary Materials S3) which focused on bibliographic information (e.g., study year), school characteristics, measures used (e.g., name, as primary/secondary outcome), intervention characteristics (e.g., length, theoretical underpinning), and information for the meta-analysis (e.g., means, standard deviations, sample size). When articles used both anxiety and depression measures and there was no information as to whether these were primary or secondary outcomes, we used the first listed measure as the primary. Data extraction was undertaken by one of the researchers previously involved in screening and checked by DH and ED.

Quality appraisal

Methodological quality of the included studies was assessed by four researchers (DH, ED, KN and AT), independently, using two specially devised risk of bias tools adapted from Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for Randomized Trials (26) and Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions’ (27). These tools have previously been adopted by other researchers (28). Quality appraisal were judged based on risk of bias due to: (i) randomisation (RCT) or confounding variables (QED), (ii) deviations from the intended interventions, (iii) missing outcome data, (iv) measurement in outcomes, and (v) selection of reported results. Based on the risk of bias tools’ guidelines (26, 27), each study was evaluated and judged on an overall risk of bias score by two researchers, independently assigning one of the following ratings: low risk, some concerns, and high risk. The lead reviewer of this article (DH) checked a 10% sample of records of other reviewer dyads.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.2.3. Due to the heterogenous nature of the data from the included studies, random effects meta-analyses were reported for outcomes related to anxiety, depression, and internalising outcomes using standardised mean differences (Cohen's d). Additionally, I2 statistics were performed to report heterogeneity. In addition, we conducted subgroup analyses to report whether the pooled intervention effects were moderated by certain study or intervention characteristics such as study design, methodological quality, outcome type, intervention duration, interventionist, school type, control condition, and intervention theory. In subgroup analyses, each subgroup was kept at three or lower groups to minimise the potential for false-positive results (29). Finally, studies with no sufficient quantitative data (i.e., post-intervention means and standard deviations) were excluded from the meta-analyses, unless they reported other quantified data that could be used to calculate effect sizes (e.g., standard error, effect size, etc). Funnel plots and Egger's test were used to explore potential publication bias.

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing the report, or the decision to submit for publication. DH, ED and JD had access to the data in the study. DH and JD had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

We screened 2,059 titles and abstracts and 367 full text records (see Figure 1). In total, 71 unique studies with a total sample of 63,041 participants were included. The PRISMA flow chart shows reasons for exclusion at each stage. At both first and second stage screening, the most common reason was the wrong outcomes being studies (n = 1,486 and n = 244, respectively.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow chart [adapted from Moher et al. (37)].

Study characteristics

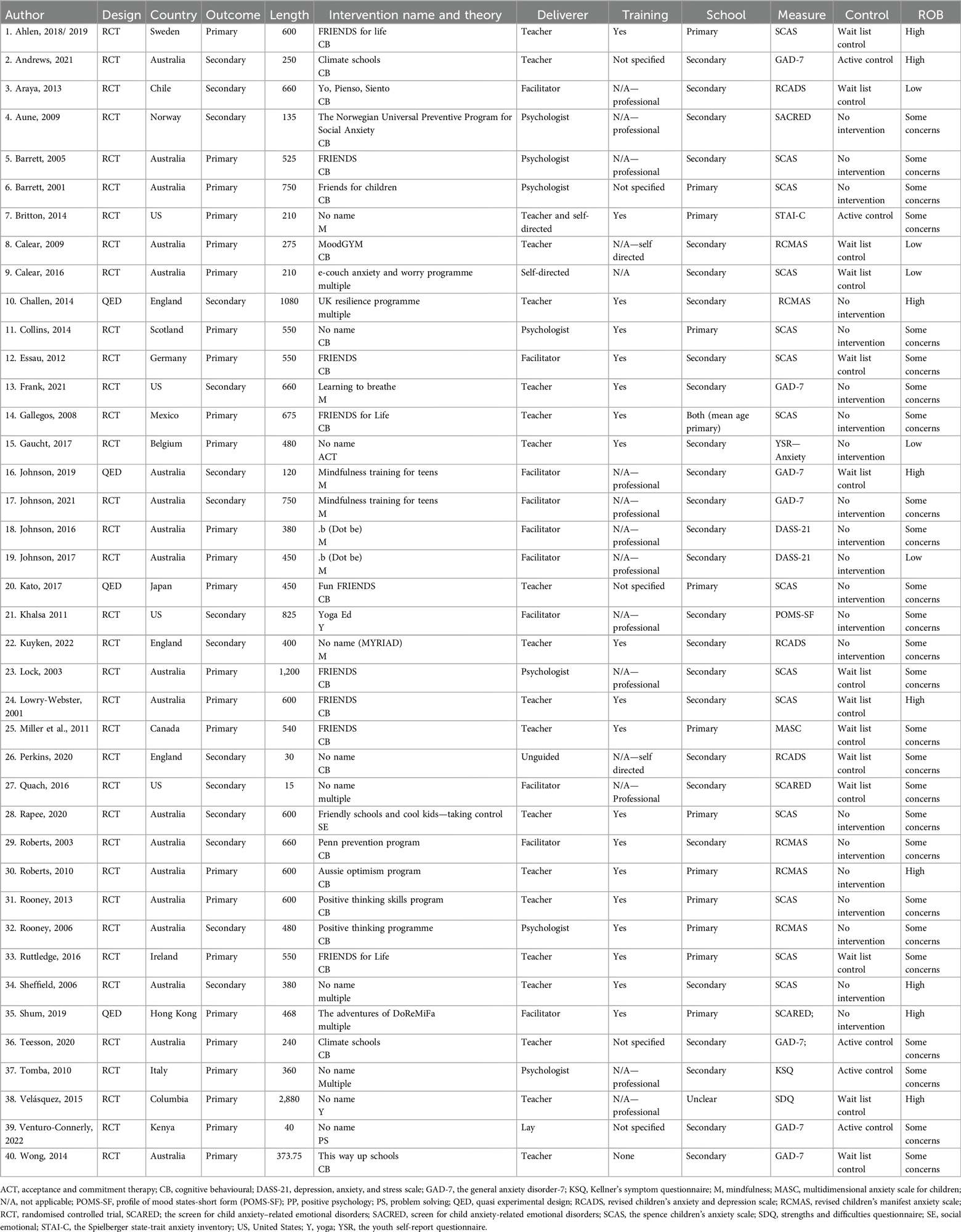

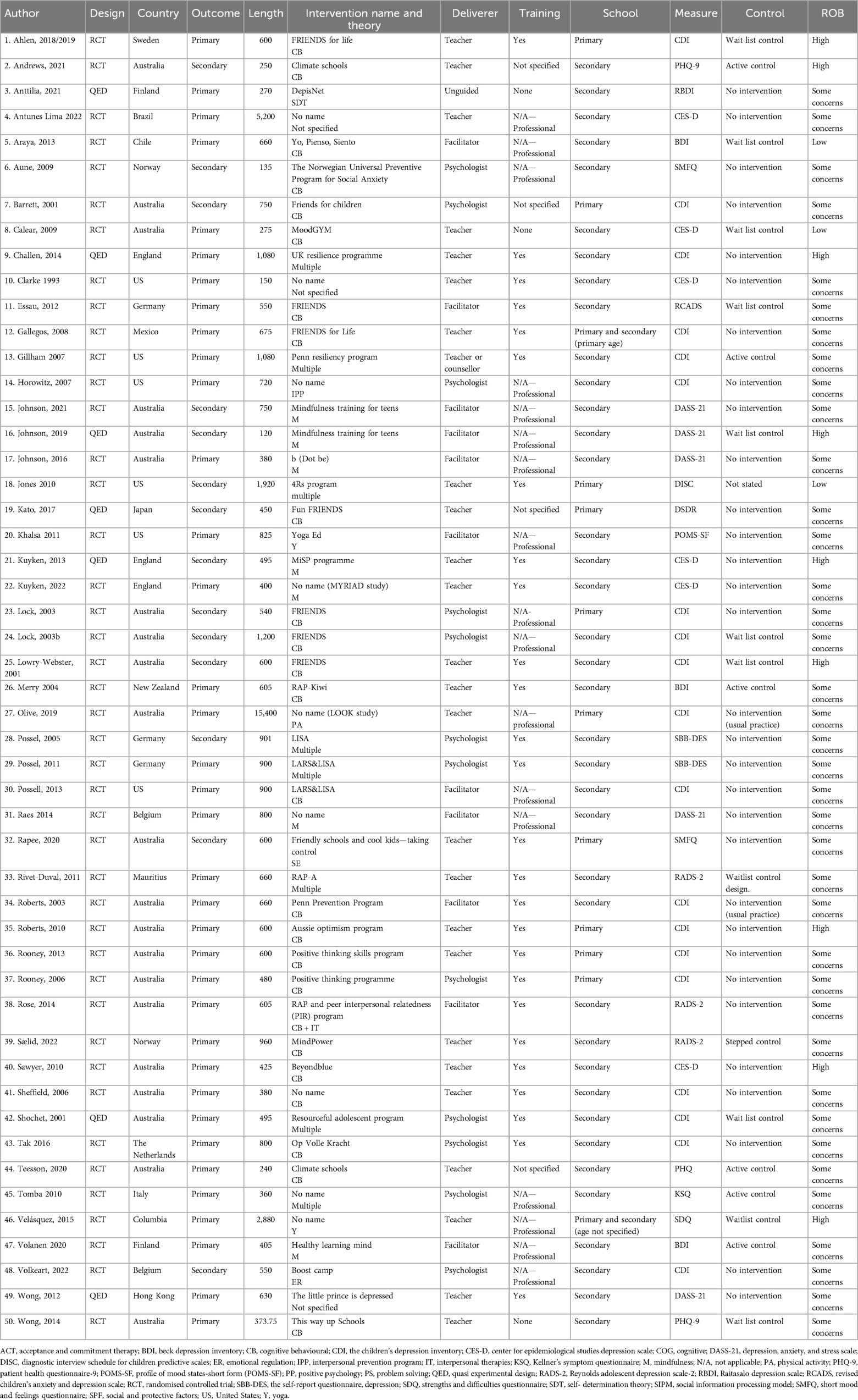

Studies were conducted between 1993 and 2022 in 22 different countries. More than half of the included studies were conducted in Australia (n = 27) and USA (n = 9) and most studies took place in the past decade (n = 44). Additionally, the majority of the included studies applied a RCT design (n = 60). Included studies were highly heterogeneous in terms of the duration and frequency of the delivered universal interventions, which ranged from a single 30-minute session to 2 h 50 min per week for four school years. Moreover, facilitators of universal interventions also varied across studies, with the majority being delivered by teachers (n = 36) followed by a psychologist (n = 22). The majority of studies (n = 51) were conducted in secondary schools, 19 were conducted in primary schools, and one study did not specify. In all included studies, children/young people reported their own anxiety and depression symptoms (n = 64); however, in six studies parents (n = 3) or teachers (n = 3) were the reporters of their children's internalising symptoms. The content of interventions were highly heterogeneous and included theoretical bases in CBT (n = 29), mindfulness (n = 11), and either one another, or multiple theories (n = 31). The most common intervention package used were alterations of the FRIENDS program for both anxiety (n = 11) and depression (n = 9). Unbranded (i.e., no named) interventions were most commonly used for internalizing difficulties (n = 5) The following were the most commonly used scales to measure children's emotional outcomes: The Spence Children's Anxiety Scale (30), The Children's Depression Inventory (31), and The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire for internalising symptoms (32).

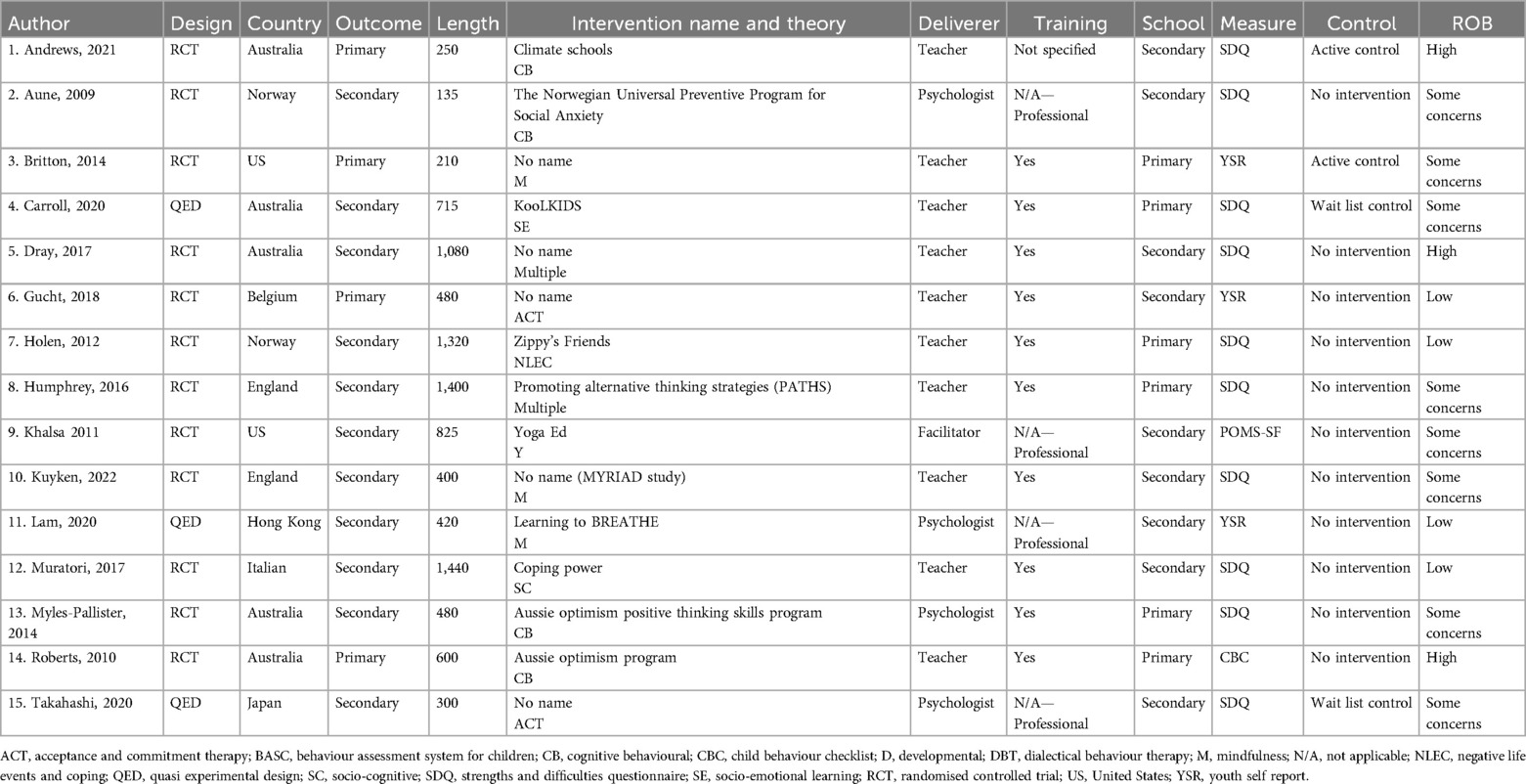

In terms of methodological quality, 9 studies showed low risk of bias, while the majority showed some methodological concerns (n = 48). 14 studies showed high risk of bias. Study characteristics and corresponding quality appraisals are outlined in Tables 1–3.

Table 1. Study characteristics for studies exploring universal school interventions on anxiety symptoms.

Table 2. Study characteristics for studies exploring universal school interventions on depressive symptoms.

Table 3. Study characteristics for studies exploring universal school interventions on internalising symptoms.

Anxiety

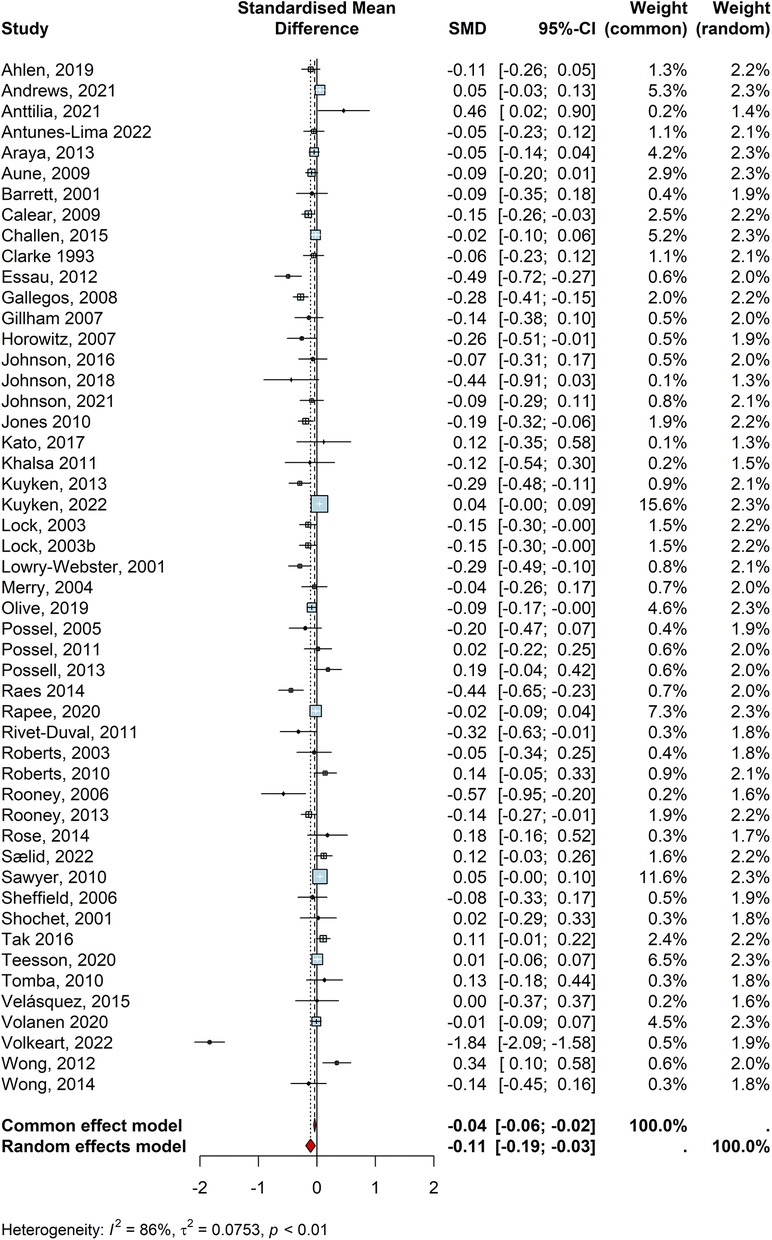

In total, 40 studies reported the efficacy of universal interventions on anxiety outcomes of children and young people (n = 35,559). Of these, 24 studies individually reported that universal interventions were effective in reducing anxiety outcomes, though only 10 of these were statistically significant (Table 1: Araya, 2013 “Yo, Pienso, Siento”; Aune, 2009 “The Norwegian Universal Preventive Program for Social Anxiety”; Barrett, 2001 “Friends for Children”; Calear, 2009 “MoodGYM”; Collins, 2014; “No name”; Essau, 2012 “FRIENDS”, Gaucht, 2017 “No name”; Lock, 2003 “FRIENDS”, Lowry-Webster, 2001 “FRIENDS”, and Rapee, 2020 “Friendly Schools and Cool Kids—Taking Control”). A random effect meta-analysis was conducted to pool these individual effect sizes from 40 studies which indicated a statistically significant, but small, negative effect size (d = −0.0858, CI = −0.15, −0.02, z = −2.46, p < .01; Figure 2). No individual studies had a driving influence (i.e., meta-influence) on the pooled effect size for the anxiety outcome and the Egger's test (t = −1.69, df = 38, p = 0.09) and the visual inspection of the funnel plot (S4) indicated no potential publication bias. This finding indicates that children and young people who received universal interventions were better off than those in the control groups in terms of experiencing symptoms of anxiety. However, these studies showed high heterogeneity (I2 = 85%, τ2 = 0.03, p < 0.01), hence, we conducted subgroup analyses to test potential influence of study characteristics on the pooled effect size. This revealed that the pooled effect size was moderated by certain study characteristics such as study design (Q = 4.10, p = 0.042), control type (Q = 9.43, p < 0.01), and intervention theory (Q = 24.93, p < 0.001). Specifically, interventions that were compared to no intervention/practice as usual were significantly more effective than those that were controlled against an active intervention group. This suggests that children and young people who received a specific universal intervention for anxiety were better off than those who received school practice as usual. Additionally, universal interventions that applied CBT principles were significantly more effective than those that applied mindfulness or other/multiple theories. Finally, interventions delivered as part of an RCT were significantly more effective than those as part of QED potentially due to the fact that RCTs better reflect intervention effects due to true randomisation and baseline equivalence.

Methodological quality, outcome type, intervention length, who delivered the intervention, or school type played no moderating role between universal interventions and anxiety outcomes Details for the subgroup analysis and funnel plot can be seen in the Supplementary Materials S4.

Depression

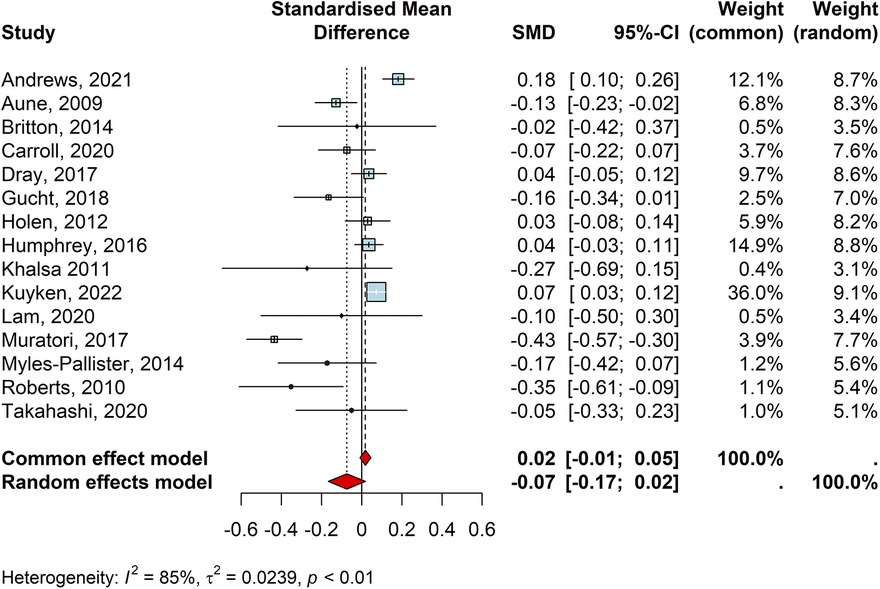

Overall, 50 studies reported depression outcomes for children and young people (n = 49,418). Of the included studies, 34 suggested that the delivered intervention reduced depression symptoms, though only 15 of these were statistically significant (Table 2: Calear, 2009 “MoodGYM”; Essau, 2012 “FRIENDS”; Gallegos, 2008 “FRIENDS for Life”, Horowitz, 2007 “No name”; Jones, 2010 “4Rs Program”; Kuyken, 2013 “MiSP programme”; Lock, 2003 “FRIENDS”;Lock, 2003b “FRIENDS”; Lowry-Webster, 2001 “FRIENDS”; Olive, 2019 “No name”; Raes, 2014 “No name”; Rivet = Duval, 2011 “RAP-A”; Rooney, 2006 “Positive Thinking Programme”; Rooney, 2013 “Positive Thinking Skills Program”; and Volkeart, 2022 “Boost Camp”. Pooling all the individual effect sizes in a random effect meta-analysis provided a negative, but small, effect size (d = −0.109, CI = −0.19, −0.03, z = −2.60, p < 0.013; Figure 3). All studies had an average influence on the pooled effect size for the depression outcome. This suggests that children and young people who received a specific universal intervention for depression had significantly lower rates of depressive symptoms compared to those who did not. However, the high heterogeneity (I2 = 86%, τ2 = 0.07, p < 0.01) indicated that the reported effect size may have been moderated by heterogenous study characteristics. Upon performing subgroup analyses, we found that certain study characteristics such as control type (Q = 8.26, p < 0.01) moderated the pooled effect size of the universal interventions on depression. Methodological quality, intervention theory, outcome type, intervention length, school type, and who delivered the intervention did not have any significant impact on the efficacy of such trials on depression outcomes. More specifically, similar to what was found for the anxiety outcome, universal interventions that delivered against practice as usual or no intervention control groups were more effective than those delivered against an active control group. That said, children and young people who received universal interventions had lower rates of depression symptoms than those who received no treatment at school. In contrast with findings for the anxiety outcome, there were no significant differences between interventions that applied CBT principles and those based on mindfulness or other/multiple theories. Finally, the visual inspection of the funnel plot and the Egger's test result (t = −2.64, df = 48, p < .01) also indicated a potential publication bias for the meta-analysis of studies reporting the depression outcome. Details for the subgroup analysis and funnel plot can be seen in the Supplementary Materials S5.

Internalising problems

There were 15 studies reporting the efficacy of universal interventions on internalising symptoms of children and young people(n = 21,473). Of these, 10 studies individually reported reduced rates of internalising difficulties for children and young people following a universal intervention, though only three of them were statistically significant (Table 3: Aune, 2009 “The Norwegian Universal Preventive Program for Social Anxiety”; Muratori, 2017 “Coping Power”, and Roberts, 2010 “Aussie Optimism Program”. A random effect meta-analysis pooling the individual effect sizes indicated no significant effect for the efficacy of such interventions on the internalising difficulties of pupils (d = −0.740, CI = −0.17, 0.02, z = −1.57, p = 0.11; I2 = 85%, τ2 = 0.02, Figure 4). The funnel plot and Egger's test (t = −2.55, df = 13, p = 0.02) showed potential publication bias for the meta-analysis of studies reporting internalising difficulties. Additionally, none of the included studies had a significant meta-influence driving the pooled effect size for the internalising difficulties outcome. Publication bias and meta-influence plot can be found in the Supplementary Materials S6. No subgroup analyses are reported as there were no significant effects of the included universal interventions on internalising outcomes.

Discussion

We aimed to investigate the impact of universal school-based interventions on emotional outcomes taking into account limitations from previous reviews. In line with some previous meta-analyses, we found that universal school-based interventions have a statistically significant but small effect for symptoms of both anxiety and depression outcomes (19, 21). However, no such effect was found for internalising outcomes. There has been much debate in the academic discourse on the magnitude of effect sizes and the degree to which they represent whether an intervention is meaningful. Carey and colleagues (33) posit the importance of context when inferring intervention impact with small effect sizes, highlighting that at an individual level, a small effect size could translate to a perceived inconsequential change on a symptomology measure for one patient, yet at a population health level, scaling interventions with small effect sizes can have impactful change. Additionally, given the increasing prevalence rates of youth mental health difficulties, with the latest estimates showing 1 in 5 young people now have a probable mental health difficulty (34), and 1 in 3 of those do not reach out for any professional support, the need for wide-reaching, effective, preventative and early interventions are crucial.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, subgroup-analyses for both anxiety and depression interventions found that interventions that were compared with no intervention/practice as usual showed greater impact than those that were controlled against an active intervention group. This suggests that providing some level of intervention could be better than doing nothing at all. However, no treatment or practice as usual represents a “low bar” against which to judge programme effectiveness. Therefore, funders of future programmes may wish to move towards comparing studies to active controls. We also found that CBT-informed approaches were significantly more effective than those that applied mindfulness or other/multiple approaches for anxiety outcomes. However, intervention type did not moderate depressive symptoms. Mindfulness has rapidly gained prominence in school curriculums in recent years, yet results from this review suggest that optimising CBT programmes over other modalities would be beneficial to prevent, or reduce, anxiety symptoms. As such, schools and public health officials should critically consider underlying modalities before implementing universal anxiety programmes. Contrary to the most recent review on this topic (14), we found that effect sizes for universal interventions were not moderated by whether interventions were delivered in primary or secondary schools. This could mean that primary schools may be an important setting to first deliver universal interventions to help prevent mental health difficulties, particularly as prevalence of emotional difficulties increases with the onset of adolescence (35). Lastly, we also found that the intervention deliverer did not moderate anxiety and depressive outcomes which also aligns with previous research (14). In conjunction with the finding that intervention length did not moderate symptomology, this suggests that there are a variety of different programmes that may have efficacy, and schools should have the flexibility to select and fully deliver universal programme that suit them in both time commitment and staff who feel able to deliver such programmes. In light of these findings on effectiveness, it is possible that when implementing universal interventions, sufficient attention should also be placed on acceptability and satisfaction so children will be more likely to engage.

A number of limitations should be acknowledged in relation to the current paper. First, whilst different databases were searched and experts consulted, it is still possible that some studies may have been missed. This may be particularly true when it comes to internalising difficulties as the term is not universally applied or where it has been measured as a secondary outcome and not reported in the title or abstract. However, to try and combat this, other similar terms, such as broadly defined emotional difficulties, were included. However, this means that different, but similar, symptom profiles may have been grouped together, so caution is advised when interpreting these results. Second, we were only able to separate sub-group analyses into a maximum of three groups to minimise false positives. This resulted in the merging of some categories which could distort or hide the impact of some intervention characteristics. Third, depression and internalising problems showed potential publication bias for the meta-analysis of studies, so caution is suggested when interpreting these results. Future meta-analyses and researcher guidelines may wish to consider how these limitations can be addressed when investigating universal interventions for pupils mental health, as well as explore the sustained impact of said interventions on such symptom profiles over time. Additionally, given that implementation factors, such as fidelity and dosage are known to impact outcomes (36), future research may wish to account for implementation factors when conducting such meta-analyses.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the current findings lend weight to the argument that universal programmes aimed at tackling depression and anxiety can be beneficial. Given the national and global trends showing incremental increases in rates of anxiety and depression difficulties in adolescents and the high numbers of individuals who do not reach out for formal support to health services, such programmes can play a modest but significant role in improving population level mental health for young people. However, findings also indicate that not all universal programmes are equal. While differences between impacts for interventions focused on different practices (e.g., mindfulness, CBT) warrant replication, they do emphasise the importance of providing clear evidence-based guidance to schools around effective and evidence-based practice to ensure time and resource is not wasted on ineffective approaches.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

DH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ED: Formal analysis, Project administration, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KN: Data curation, Formal analysis, Project administration, Validation, Writing – review & editing. AT: Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing. AM: Data curation, Project administration, Validation, Writing – review & editing. CM: Data curation, Project administration, Validation, Writing – review & editing. JS: Data curation, Project administration, Validation, Writing – review & editing. RM: Data curation, Project administration, Validation, Writing – review & editing. EA: Data curation, Project administration, Validation, Writing – review & editing. BM: Data curation, Project administration, Validation, Writing – review & editing. SL: Data curation, Project administration, Validation, Writing – review & editing. HM: Data curation, Project administration, Validation, Writing – review & editing. JB: Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. NH: Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. PS: Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. PP: Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. JD: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This article is independent research funded by the Department for Education as part of the Education for Wellbeing Programme (Grant number: EOR/SBU/2017/015).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frcha.2025.1526840/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Bor W, Dean AJ, Najman J, Hayatbakhsh R. Are child and adolescent mental health problems increasing in the 21st century? A systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2014) 48(7):606–16. doi: 10.1177/0004867414533834

2. Patalay P, Gage SH. Changes in millennial adolescent mental health and health-related behaviours over 10 years: a population cohort comparison study. Int J Epidemiol. (2019) 48(5):1650–64. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz006

3. World Health Organisation. Global accelerated action for the health of adolescents (AA-HA!): guidance to support country implementation. Geneva. (2017). Available at: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/255415/9789241512343-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (Accessed October, 07, 2024).

5. Naicker K, Galambos NL, Zeng Y, Senthilselvan A, Colman I. Social, demographic, and health outcomes in the 10 years following adolescent depression. J Adolesc Health. (2013) 52(5):533–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.12.016

6. Essau CA, Lewinsohn PM, Olaya B, Seeley JR. Anxiety disorders in adolescents and psychosocial outcomes at age 30. J Affect Disord. (2014) 163:125–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.12.033

7. Fazel M, Patel V, Thomas S, Tol W. Mental health interventions in schools in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Psychiatry. (2014) 1(5):388–98. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70357-8

8. Fazel M, Hoagwood K, Stephan S, Ford T. Mental health interventions in schools in high-income countries. Lancet Psychiatry. (2014) 1(5):377–87. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70312-8

9. Caan W, Cassidy J, Coverdale G, Ha MA, Nicholson W, Rao M. The value of using schools as community assets for health. Public Health. (2015) 129(1):3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2014.10.006

10. Department of Health and Department for Education. Transforming Children and Young People’s Mental Health Provision: A Green Paper. London: Department of Health and Department for Education (2017).

11. Memon A, Taylor K, Mohebati LM, Sundin J, Cooper M, Scanlon T, et al. Perceived barriers to accessing mental health services among black and minority ethnic (BME) communities: a qualitative study in southeast England. BMJ Open. (2016) 6(11):e012337. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012337

12. Weist MD, Evans SW. Expanded school mental health: challenges and opportunities in an emerging field. J Youth Adolesc. (2005) 34(1):3–6. doi: 10.1007/s10964-005-1330-2

13. Shoshani A, Steinmetz S. Positive psychology at school: a school-based intervention to promote adolescents’ mental health and well-being. J Happiness Stud. (2014) 15(6):1289–311. doi: 10.1007/s10902-013-9476-1

14. Caldwell DM, Davies SR, Hetrick SE, Palmer JC, Caro P, López-López JA, et al. School-based interventions to prevent anxiety and depression in children and young people: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. (2019) 6(12):1011–20. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30403-1

15. Vostanis P, Humphrey N, Fitzgerald N, Deighton J, Wolpert M. How do schools promote emotional well-being among their pupils? Findings from a national scoping survey of mental health provision in English schools. Child Adolesc Ment Health. (2013) 18(3):151–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2012.00677.x

16. Hayes D, Moore A, Stapley E, Humphrey N, Mansfield R, Santos J, et al. School-based intervention study examining approaches for well-being and mental health literacy of pupils in year 9 in England: study protocol for a multischool, parallel group cluster randomised controlled trial (AWARE). BMJ Open. (2019) 9(8):e029044. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029044

17. Hayes D, Moore A, Stapley E, Humphrey N, Mansfield R, Santos J, et al. Promoting mental health and well-being in schools: examining mindfulness, relaxation and strategies for safety and well-being in English primary and secondary schools—study protocol for a multi-school, cluster randomised controlled trial (INSPIRE). Trials. (2023) 24(1):220. doi: 10.1186/s13063-023-07238-8

18. McLaughlin KA. The public health impact of major depression: a call for interdisciplinary prevention efforts. Prev Sci. (2011) 12(4):361–71. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0231-8

19. Stockings EA, Degenhardt L, Dobbins T, Lee YY, Erskine HE, Whiteford HA, et al. Preventing depression and anxiety in young people: a review of the joint efficacy of universal, selective and indicated prevention. Psychol Med. (2016) 46(1):11–26. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001725

20. Johnstone KM, Kemps E, Chen J. A meta-analysis of universal school-based prevention programs for anxiety and depression in children. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. (2018) 21(4):466–81. doi: 10.1007/s10567-018-0266-5

21. Werner-Seidler A, Perry Y, Calear AL, Newby JM, Christensen H. School-based depression and anxiety prevention programs for young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. (2017) 51:30–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.10.005

22. Caldwell DM, Davies SR, Thorn JC, Palmer JC, Caro P, Hetrick SE, et al. School-based interventions to prevent anxiety, depression and conduct disorder in children and young people: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Public Health Research. (2021) 9(8):1–284. doi: 10.3310/phr09080

24. Fazel M, Kohrt BA. Prevention versus intervention in school mental health. Lancet Psychiatry. (2019) 6(12):969–71. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30440-7

25. Torgerson CJ, Porthouse J, Brooks G. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials evaluating interventions in adult literacy and numeracy. J Res Read. (2003) 26(3):234–55. doi: 10.1111/1467-9817.00200

26. Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. Rob 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Br Med J. (2019) 366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898

27. Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. Br Med J. (2016) 355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919

28. Deniz E, Francis G, Torgerson C, Toseeb U. Parent-mediated play-based interventions to improve social communication and language skills of preschool autistic children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev J Autism Dev Disord. (2024). doi: 10.1007/s40489-024-00463-0

29. Burke JF, Sussman JB, Kent DM, Hayward RA. Three simple rules to ensure reasonably credible subgroup analyses. Br Med J. (2015) 351:h5651. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h5651

31. Kovacs M. The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) Manual North Tanawanda. New York: Multi-Health Systems (1992).

32. Goodman R. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (1997) 38(5):581–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x

33. Carey EG, Ridler I, Ford TJ, Stringaris A. Editorial perspective: when is a ’small effect’ actually large and impactful? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2023) 64(11):1643–7. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13817

34. NHS Digital. Mental Health of Children and Young People in England, 2023 - Wave 4 Follow up to the 2017 Survey. London: NHS Digital (2023). Available at: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-of-children-and-young-people-in-england/2023-wave-4-follow-up# (Accessed February 16, 2024).

35. World Health Organisation. Mental Health of Adolescents. Geneva: World Health Organization (2021). Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (Accessed Februay 16, 2024).

36. Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am J Community Psychol. (2008) 41(3-4):327–50. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0

Keywords: school, universal, mental health, pupil, emotional

Citation: Hayes D, Deniz E, Nisbet K, Thompson A, March A, Mason C, Santos J, Mansfield R, Ashworth E, Moltrect B, Liverpool S, Merrick H, Boehnke J, Humphrey N, Stallard P, Patalay P and Deighton J (2025) Universal, school-based, interventions to improve emotional outcomes in children and young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 4:1526840. doi: 10.3389/frcha.2025.1526840

Received: 12 November 2024; Accepted: 6 May 2025;

Published: 2 June 2025.

Edited by:

Sarfraz Aslam, UNITAR International University, MalaysiaReviewed by:

Erin Rappuhn, Eastern University, United StatesAngel Puig-Lagunes, Universidad Veracruzana, Mexico

Copyright: © 2025 Hayes, Deniz, Nisbet, Thompson, March, Mason, Santos, Mansfield, Ashworth, Moltrect, Liverpool, Merrick, Boehnke, Humphrey, Stallard, Patalay and Deighton. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Daniel Hayes, ZC5oYXllc0B1Y2wuYWMudWs=

†These authors share first authorship

Daniel Hayes

Daniel Hayes Emre Deniz

Emre Deniz Kirsty Nisbet

Kirsty Nisbet Abigail Thompson1

Abigail Thompson1 Anna March

Anna March Rosie Mansfield

Rosie Mansfield Emma Ashworth

Emma Ashworth Shaun Liverpool

Shaun Liverpool Jan Boehnke

Jan Boehnke Neil Humphrey

Neil Humphrey