- 1Department of Biotechnological and Applied Clinical Sciences, University of L'Aquila, L'Aquila, Italy

- 2Department of Life, Health and Environmental Sciences, University of L'Aquila, L'Aquila, Italy

This study examined whether need for touch predicts problematic smartphone use (PSU) and problematic social media use (PSMU), beyond psychological factors, including narcissism (grandiose and vulnerable), fear of missing out (FoMO), and emotion regulation strategies (cognitive reappraisal and emotion suppression). A total of 430 emerging adults (Mage = 19.50, SD = 1.12; 50% female) completed an online survey. Hierarchical regression analyses revealed that need for touch significantly predicted both PSU and PSMU, with a stronger effect on PSU, suggesting that haptic gratifications may drive smartphone engagement beyond social media use. These findings extend previous research by demonstrating that need for touch is a robust contributor to problematic digital behaviors. In addition, they underscore the need to integrate sensory-motivational drivers into theoretical models of PSU and PSMU and highlight the relevance of sensory-based approaches in future clinical intervention strategies. Limitations and future research directions are discussed.

1 Introduction

The rapid spread of digital technologies has profoundly renovated the organization of human everyday life. Activities traditionally rooted in face-to-face contexts, including communication, education, work, and entertainment, are increasingly embedded in digital settings, reshaping how individuals interact, acquire knowledge, and spend their leisure time. At the core of this digital transformation stand smartphones and social media platforms, which serve as the primary gateway between individuals and collective experiences, especially among emerging adults—individuals under 25 years old (Statista, 2025).

Although smartphones and social media have opened new frontiers for connection, information exchange, and accessibility, concerns have grown about maladaptive patterns, such as problematic smartphone use (PSU) and problematic social media use (PSMU).

PSU refers to a compulsive and unregulated pattern of smartphone use that impairs daily functioning (Xiao et al., 2025). According to Billieux et al. (2015) model, PSU relies on three primary developmental pathways: (1) excessive reassurance, driven by the need to maintain interpersonal relationships and obtain validation from others; (2) impulsivity, stemming from poor impulse control, which may lead to uncontrolled urges and dysregulated smartphone use; (3) extraversion associated with a heightened need for stimulation and sensitivity to rewards.

PSMU is defined as a compulsive pattern of social media engagement that interferes with daily functioning (Shannon et al., 2025). It relies on six main features: salience (preoccupation with social media use to the detriment of other activities), mood modification (using social media to regulate mood), tolerance (needing increasing use of social media to achieve the same initial effect), withdrawal (experiencing negative emotional or physical symptoms when unable to use social media), conflict (intrapersonal and interpersonal problems resulting from excessive social media use), and relapse (returning to excessive use of social media after a period of abstinence) (Giancola et al., 2025).

Although substantial effort has been dedicated to elucidating the psychological mechanisms underlying PSU and PSMU, important knowledge gaps remain. One influential framework in this field is the Interaction of Person–Affect–Cognition–Execution (I-PACE) model (Brand et al., 2016), which conceptualizes problematic technology use as the result of dynamic interactions among person-related characteristics (P) affective and cognitive responses to specific situations (A and C), and executive and behavioral reactions (E) (Liu et al., 2025; Mehmood et al., 2021).

Within the Person domain, grandiose narcissism—characterized by assertiveness, exhibitionism, and self-enhancement motivations—has been associated with PSU and PSMU. Individuals high in this trait tend to use smartphones and social media compulsively to affirm their value, worth, and power as well as maintain an inflated self-image in front of a large audience (Balta et al., 2019; Casale and Banchi, 2020). In addition, vulnerable narcissism—marked by low self-esteem, social inhibition, and sensitivity to rejection—is associated with PSU and PSMU due to a preference for online interaction as a safer relational context (Fontana et al., 2023; Ksinan et al., 2021). In both cases, smartphones and social media serve as tools to support self-regulatory motives, either to amplify visibility or to shield the self from interpersonal threat. In the Affect and Cognition domains, fear of missing out (FoMO)—a negative emotional state resulting from unmet social-relatedness needs (Gupta and Sharma, 2021)—has been identified as one of the primary affective mechanisms underpinning PSU and PSMU. Indeed, individuals high in FoMO tend to resort to smartphones and social media to maintain constant social connectivity (Elhai et al., 2016). In addition, for individuals with low abilities in emotion regulation strategies (e.g., cognitive reappraisal), the compulsive and unregulated use of smartphones and social media can represent a means to cope with negative internal states, such as boredom and stress (Brailovskaia and Margraf, 2024; Shi et al., 2023; Zsido et al., 2021).

Nevertheless, beyond person-related characteristics and affective and cognitive mechanisms, tactile factors may help explain PSU and PSMU. Need for touch represents a multidimensional construct encompassing the individual tendency to prefer and enjoy tactile sensations and haptic information (Peck and Childers, 2003a). In particular, smartphones offer continuous sensorimotor feedback through swiping, tapping, scrolling, and holding (Kangas et al., 2014). These repetitive touch-based actions become intrinsically rewarding, providing tactile pleasure that reinforces engagement with the device (Elhai et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2014). This process is consistent with evidence showing that sensorimotor feedback (e.g., vibration and haptic pulses) can function as a secondary reward. While primary rewards (e.g., food, water, thermal warmth, or even sex) are intrinsically associated with biological processes in humans and are critical for survival and reproduction, secondary rewards reinforce learned associations between the stimulus and a positive outcome (Hampton and Hildebrand, 2025; Sescousse et al., 2013). In the context of smartphone use, the tactile sensations themselves acquire reward value through repeated pairing with socially and emotionally meaningful outcomes, such as receiving messages, calls, notifications or notifications about new likes and comments on social media (Hampton and Hildebrand, 2025).

Within the I-PACE framework, need for touch can be positioned in the Person domain as a sensory-motivational predisposition that makes digital devices rewarding to use. Therefore, whereas narcissism, FoMO, and emotion regulation strategies reflect why individuals compulsively turn to smartphones and social media through self-enhancement, social reassurance, and emotional coping, need for touch reflects how the sensory features of the device maintain and reinforce the behavior once initiated. The tactile gratification inherent in touchscreen interaction may amplify affective relief and salience, strengthening habitual use even in the absence of explicit social or emotional motives. Accordingly, the research hypothesis is that need for touch predicts both PSU and PSMU over and above narcissism, FoMO, and emotion regulation strategies.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants and procedure

Four hundred and fifty subjects took part in the online survey. After handling missing data (N = 16) and removing outliers (N = 4, with ± 3 z-score as threshold), the final sample consisted of 430 participants aged between 18 and 21 (Mage = 19.50, SDage = 1.12; 215 females).

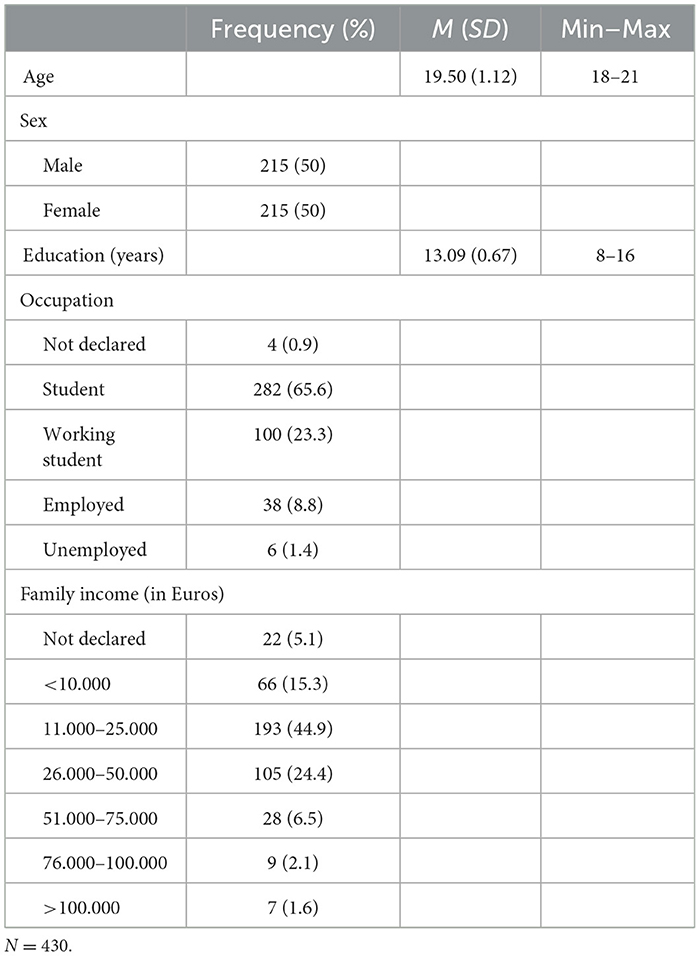

Eligibility was determined according to two inclusion criteria: (1) regular use of at least one social media platform and (2) absence of self-reported neuropsychological or psychiatric conditions. An overview of the sample's main socio-demographic characteristics is presented in Table 1.

Data were collected through an online cross-sectional survey conducted between January and October 2024. Participants were recruited via a snowball sampling strategy using online advertisements shared on various social media and instant messaging platforms, including Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp. Before starting the survey, participants provided informed consent electronically by selecting a checkbox after reading an online consent form outlining the study purpose and eligibility criteria. Participation was entirely voluntary and without rewards. All responses were collected anonymously, and participants were assured of data confidentiality and security.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of L'Aquila (Protocol No. 119943). All procedures performed in the current research were in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki declaration.

2.2 Measures

A brief socio-demographic questionnaire assessed participants' age, gender, educational level, employment status, and family income.

Grandiose narcissism was assessed using an Italian adaptation of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory-13 (NPI-13; Giancola et al., 2024, 2025). The NPI-13 comprises 13 items (e.g., “I will usually show off if I get the chance”) rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). In previous studies, the Italian adaptation of the NPI-13 has reported acceptable psychometric properties (Giancola et al., 2024, 2025). In the present sample, internal consistency reliability was good (Cronbach's α = 0.87).

Vulnerable narcissism was measured using the Italian version of the Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale (HSNS; Fossati et al., 2009). The HSNS consists of 10 items (e.g., “I feel that I have enough on my hands without worrying about other peoples' trouble”) rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (very untrue of me) to 7 (very true of me). Previous studies have documented satisfactory psychometric properties of the Italian version (Fossati et al., 2009). In the present sample, internal consistency reliability was acceptable (Cronbach's α = 0.75).

Fear of missing out (FoMO) was assessed using the Italian version of the fear of missing out scale (FoMOS; Casale and Fioravanti, 2020). The scale contains 10 items (e.g., “I fear others have more rewarding experiences than me”) rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 (not at all true for me) to 5 (extremely true for me). Previous studies have supported good psychometric properties of the Italian version (Casale and Fioravanti, 2020). In the present sample, internal consistency reliability was good (Cronbach's α = 0.82).

Emotion regulation was measured using the Italian version of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ; Balzarotti et al., 2010). The ERQ comprises 10 items rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Six items assess cognitive reappraisal [e.g., “When I want to feel more positive emotion (such as joy or amusement), I change what I'm thinking about”], and four items assess emotion suppression (e.g., “I keep my emotions to myself”). Previous studies have documented good psychometric properties of the Italian version (Balzarotti et al., 2010). In the present sample, internal consistency reliability was excellent for cognitive reappraisal (Cronbach's α = 0.90) and acceptable for emotion suppression (Cronbach's α = 0.72).

Need for touch was evaluated using the Need for Touch Scale (NfTS; Lee et al., 2014). The scale includes six items (e.g., “Touching products can be fun”) rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The original scale was translated and back-translated by a bilingual native speaker to ensure linguistic and conceptual equivalence. An exploratory factor analysis supported the adequacy of the data (KMO = 0.90; Bartlett's test of sphericity, p < 0.001), indicating a single-factor structure that accounted for 77.89% of the total variance. In the present sample, internal consistency reliability was good (Cronbach's α = 0.87).

Problematic smartphone use (PSU) was assessed using the Italian version of the Smartphone Addiction Scale—Short Version (SAS-SV; Servidio et al., 2023). The SAS-SV consists of 10 items (e.g., “Having my smartphone in my mind even when I am not using it”) rated on a 6-point Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Previous research has confirmed good psychometric properties of the Italian version (Servidio et al., 2023). In the present sample, internal consistency reliability was good (Cronbach's α = 0.87).

Problematic social media use (PSMU) was measured using the Italian version of the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS; Monacis et al., 2017). The BSMAS comprises six items (e.g., “How often during the last year have you felt an urge to use social media more and more?”) rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 (very rarely) to 5 (very often). Previous studies have demonstrated good psychometric properties of the Italian version (Monacis et al., 2017). In the present sample, internal consistency reliability was good (Cronbach's α = 0.81).

3 Results

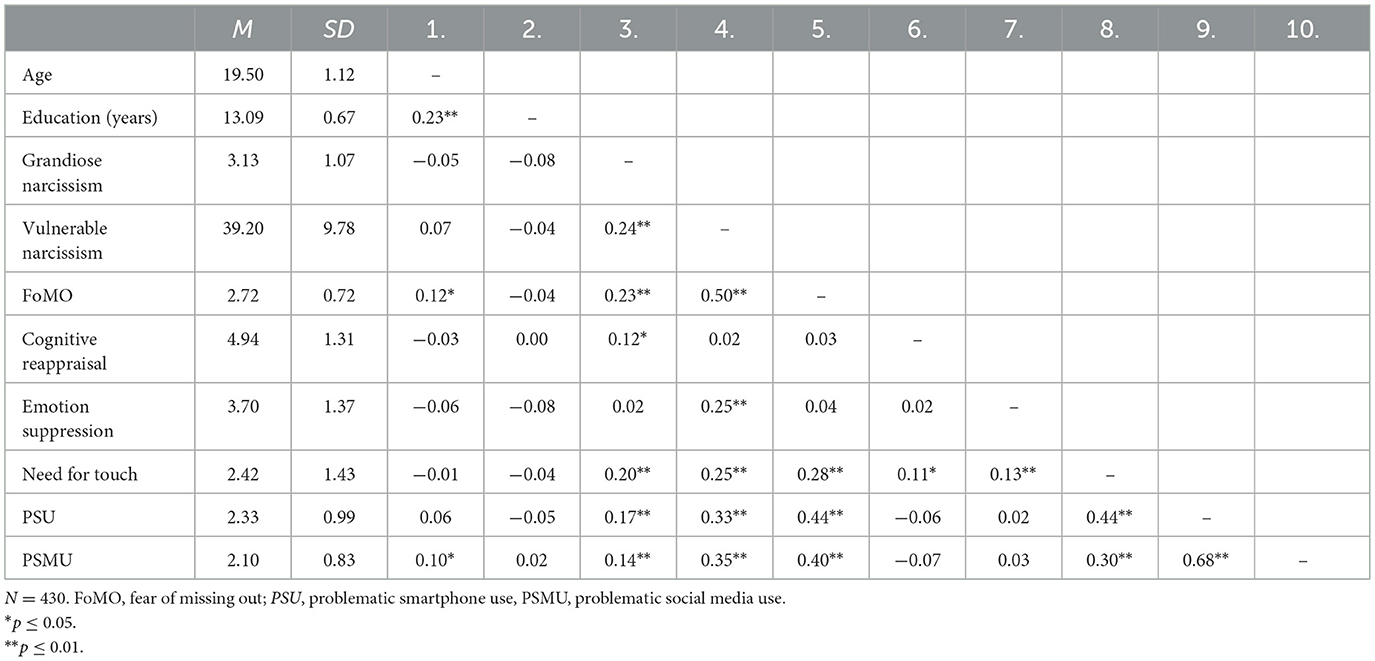

Partial correlation, with gender as the control variable, indicated that PSU was positively correlated with grandiose narcissism, vulnerable narcissism, FoMO, and need for touch. In addition, PSMU was positively correlated with age, grandiose narcissism, vulnerable narcissism, FoMO, and need for touch. Table 2 reports descriptive statistics and correlations among the study variables.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and partial correlations among the study variables (controlling for gender).

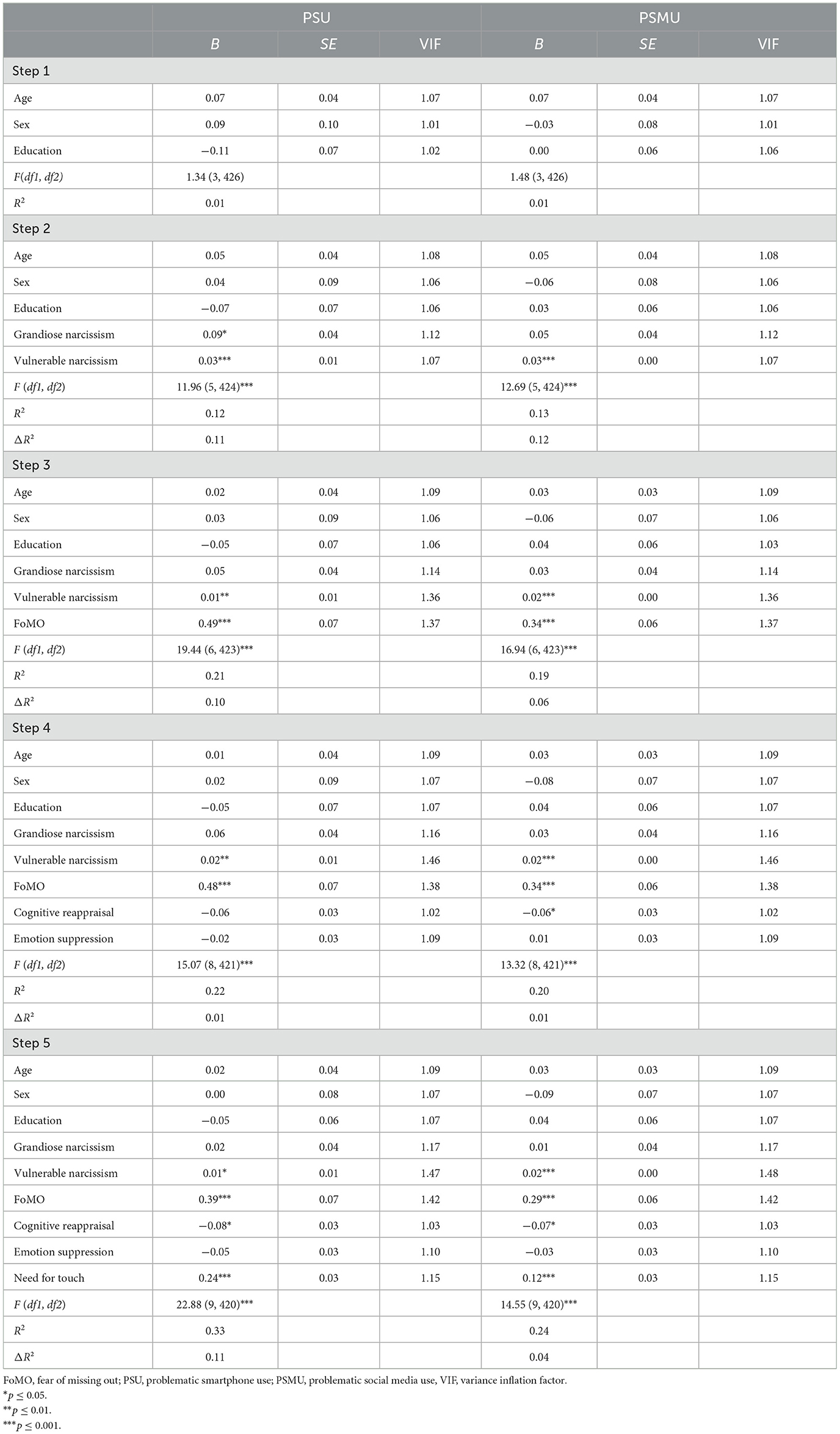

A hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to examine the predictors of PSU. The analysis was performed in five steps, sequentially entering demographic variables (age, sex, and education), personality traits (grandiose and vulnerable narcissism), FoMO, emotion regulation strategies (cognitive reappraisal and emotion suppression), and finally, need for touch. Results showed that vulnerable narcissism, FoMO, and need for touch were significant positive predictors of PSU, whereas cognitive reappraisal was a significant negative predictor. A second hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to identify the predictors of PSMU using the same five-step model. Similarly, vulnerable narcissism, FoMO, and need for touch emerged as significant positive predictors, while cognitive reappraisal negatively predicted PSMU. All statistical results of the hierarchical regression analyses are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Hierarchical regression analysis with sociodemographics, narcissism (grandiose and vulnerable), FoMO, and emotion regulation strategies (cognitive reappraisal and emotion suppression) predicting PSU and PSMU.

4 Discussion

This study examines the role of need for touch in PSU and PSMU during emerging adulthood. Results confirmed the research hypothesis: need for touch predicts both PSU and PSMU over and above narcissism, FoMO, and emotion regulation strategies.

The predictive effect of need for touch on PSU aligns with Billieux et al. (2015) model, which proposes three developmental pathways underlying PSU: reassurance, impulsivity, and extraversion. Need for touch may affect these pathways through different mechanisms. First, tactile feedback during smartphone interaction (e.g., scrolling, tapping, holding) may soothe uncertainty and reinforce reassurance-seeking, strengthening repeated checking behaviors. Second, the immediacy and hedonic quality of touch-based interactions may lower inhibitory thresholds, facilitating impulsive engagement. Third, the sensorimotor pleasure of touchscreen use may amplify the reward value of socially expressive communication, supporting high levels of outward engagement associated with extraversion-oriented PSU. Despite this evidence, the effect of need for touch was smaller for PSMU (B = 0.12) than for PSU (B = 0.24). This result is consistent with the view that PSMU variance is more strongly driven by social–affective motives (e.g., FoMO) rather than tactile mechanisms. Therefore, within the I-PACE framework (Brand et al., 2016), need for touch can be conceptualized as a Person-domain predisposition that increases the baseline reward potential of device interaction. This sensory predisposition subsequently shapes affective relief and attentional salience during use (A and C), strengthening behavioral repetition (E).

Importantly, hierarchical regression analyses revealed that FoMO remained a significant and strong predictor even after accounting for other variables. At the same time, vulnerable narcissism retained a significant, albeit smaller, effect across steps, highlighting its role as a dispositional vulnerability associated with compensatory digital behaviors. Grandiose narcissism, by contrast, showed only a modest effect at earlier steps and lost significance when other variables were introduced, suggesting that its role is more limited when sensory-motivational and affective factors are accounted for. In addition, emotion regulation strategies made a more modest but meaningful contribution: cognitive reappraisal negatively predicted both PSU and PSMU in the final model, indicating that individuals who are better able to reframe emotional experiences may be less prone to problematic digital engagement. This result supports the view that adaptive emotion regulation can act as a protective factor, possibly buffering against compulsive use. Emotion suppression did not emerge as a significant predictor in any model, suggesting that its role may be less relevant in this context.

These results offer relevant implications. From a theoretical standpoint, they expand the conceptualization of PSU and PSMU beyond cognitive, emotional, and personality-based frameworks, integrating embodied and sensory dimensions into models of problematic technology use. In particular, results suggest that haptic reinforcement constitutes a transdiagnostic mechanism underlying engagement with digital technologies (Peck and Childers, 2003a,b). From a practical perspective, the findings underscore the importance of incorporating sensory-based self-regulation strategies, such as reducing haptic feedback and stimulus-control strategies, into prevention and intervention programs targeting both PSU and PSMU.

Despite these contributions, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences regarding the observed relationships. Future research employing longitudinal or experimental designs is needed to clarify the directionality of these effects. Second, participants were recruited via a snowball sampling method, which may introduce selection bias and limit the generalisability of the results. Third, reliance on self-report measures may introduce response biases, including social desirability. Future research should incorporate behavioral or ecological measures to clarify the role of need for touch in both PSU and PSMU.

5 Conclusion

Overall, the results of this research situate need for touch within the I-PACE model as a person-level predisposition that fosters tactile reinforcement loops, maintaining compulsive technology engagement. Although longitudinal and experimental studies are needed to establish causality, the present results indicate that effective responses to problematic technology use must target not only the motivational antecedents of engagement but also the sensory contingencies of touch-based interfaces.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by IRB of the University of L'Aquila. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MG: Conceptualization, Project administration, Formal analysis, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft. MP: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Conceptualization. DB: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. EP: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. SD'A: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Resources.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Balta, S., Jonason, P., Denes, A., Emirtekin, E., Tosuntaş, S. B., Kircaburun, K., et al. (2019). Dark personality traits and problematic smartphone use: the mediating role of fearful attachment. Pers. Individ. Dif. 149, 214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2019.06.005

Balzarotti, S., John, O. P., and Gross, J. J. (2010). An Italian adaptation of the emotion regulation questionnaire. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 26, 61–67. doi: 10.1027/1015-5759/a000009

Billieux, J., Maurage, P., Lopez-Fernandez, O., Kuss, D. J., and Griffiths, M. D. (2015). Can disordered mobile phone use be considered a behavioral addiction? An update on current evidence and a comprehensive model for future research. Curr. Addict. Rep. 2, 156–162. doi: 10.1007/s40429-015-0054-y

Brailovskaia, J., and Margraf, J. (2024). The “Bubbles”-study: validation of ultra-short scales for the assessment of addictive social media use and grandiose narcissism. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 13:100382. doi: 10.1016/j.chbr.2024.100382

Brand, M., Young, K. S., Laier, C., Wölfling, K., and Potenza, M. N. (2016). Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific internet-use disorders: an interaction of person-affect-cognition-execution (I-PACE) model. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 71, 252–266. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.033

Casale, S., and Banchi, V. (2020). Narcissism and problematic social media use: a systematic literature review. Addict. Behav. Rep. 11:100252. doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2020.100252

Casale, S., and Fioravanti, G. (2020). Factor structure and psychometric properties of the Italian version of the fear of missing out scale in emerging adults and adolescents. Addict. Behav. 102:106179. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106179

Elhai, J. D., Levine, J. C., Dvorak, R. D., and Hall, B. J. (2016). Fear of missing out, need for touch, anxiety and depression are related to problematic smartphone use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 63, 509–516. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.079

Fontana, A., Benzi, I. M. A., Ghezzi, V., Cianfanelli, B., and Sideli, L. (2023). Narcissistic traits and problematic internet use among youths: a latent change score model approach. Pers. Individ. Dif. 212:112265. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2023.112265

Fossati, A., Borroni, S., Grazioli, F., Dornetti, L., Marcassoli, I., Maffei, C., et al. (2009). Tracking the hypersensitive dimension in narcissism: reliability and validity of the hypersensitive narcissism scale. Pers. Ment. Health 3, 235–247. doi: 10.1002/pmh.92

Giancola, M., Perazzini, M., Bontempo, D., Perilli, E., and D'Amico, S. (2024). Narcissism and problematic social media use: a moderated mediation analysis of fear of missing out and trait mindfulness in youth. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 41, 1–11. doi: 10.1080/10447318.2024.2411468

Giancola, M., Vinciguerra, M. G., and D'Amico, S. (2025). Narcissism and the risk of exercise addiction in youth: the impact of problematic social media use and fitspiration exposure. Eur. J Dev. Psychol. 22, 456–477. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2025.2467049

Gupta, M., and Sharma, A. (2021). Fear of missing out: a brief overview of origin, theoretical underpinnings and relationship with mental health. World J. Clin. Cases 9:4881. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i19.4881

Hampton, W. H., and Hildebrand, C. (2025). Haptic rewards: how mobile vibrations shape reward response and consumer choice. J. Consum. Res. ucaf 025. doi: 10.1093/jcr/ucaf025

Kangas, J., Akkil, D., Rantala, J., Isokoski, P., Majaranta, P., and Raisamo, R. (2014). “Gaze gestures and haptic feedback in mobile devices”, in Proceedings of the Sigchi Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 435–438. doi: 10.1145/2556288.2557040

Ksinan, A. J., Mališ, J., and Vazsonyi, A. T. (2021). Swiping away the moments that make up a dull day: narcissism, boredom, and compulsive smartphone use. Curr. Psychol. 40, 2917–2926. doi: 10.1007/s12144-019-00228-7

Lee, Y. K., Chang, C. T., Lin, Y., and Cheng, Z. H. (2014). The dark side of smartphone usage: psychological traits, compulsive behavior and technostress. Comput. Hum. Behav. 31, 373–383. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.047

Liu, T. H., Xia, Y., and Ma, Z. (2025). Understanding emerging adult workers' problematic internet use before and during the coronavirus pandemic: roles of personality traits, online activities, and mental health symptoms. Psychiatr. Quart. 1–25. doi: 10.1007/s11126-025-10196-w

Mehmood, A., Bu, T., Zhao, E., Zelenina, V., Alexander, N., Wang, W., et al. (2021). Exploration of psychological mechanism of smartphone addiction among international students of China by selecting the framework of the I-PACE model. Front. Psychol. 12:758610. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.758610

Monacis, L., De Palo, V., Griffiths, M. D., and Sinatra, M. (2017). Social networking addiction, attachment style, and validation of the Italian version of the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale. J. Behav. Addict., 6, 178–186. doi: 10.1556/2006.6.2017.023

Peck, J., and Childers, T. L. (2003a). Individual differences in haptic information processing: the “need for touch” scale. J. Consum. Res. 30, 430–442. doi: 10.1086/378619

Peck, J., and Childers, T. L. (2003b). To have and to hold: the influence of haptic information on product judgments. J. Mark. 67, 35–48. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.67.2.35.18612

Servidio, R., Griffiths, M. D., Di Nuovo, S., Sinatra, M., and Monacis, L. (2023). Further exploration of the psychometric properties of the revised version of the Italian smartphone addiction scale—short version (SAS-SV). Curr. Psychol. 42, 27245–27258. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-03852-y

Sescousse, G., Caldú, X., Segura, B., and Dreher, J. C. (2013). Processing of primary and secondary rewards: a quantitative meta-analysis and review of human functional neuroimaging studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 37, 681–696. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.02.002

Shannon, H., Montgomery, M., Guimond, S., and Hellemans, K. (2025). Problematic social media use and inhibitory control among post-secondary students. Addict. Behav. 165:108307. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2025.108307

Shi, Y., Koval, P., Kostakos, V., Goncalves, J., and Wadley, G. (2023). “Instant happiness”: smartphones as tools for everyday emotion regulation. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 170:102958. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhcs.2022.102958

Statista (2025). Daily Time Spent on Social Media Networking by Internet Users Worldwide from 2012 to 2025. Statista. Available online at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/433871/daily-social-media-usage-worldwide/?srsltid=AfmBOooSozrFsNBeGGxolAPiGh4EaMbHFCvWibUd9DhOHil4HhSrs3DV (Acessed April 18, 2025).

Xiao, B., Zhao, H., Hein-Salvi, C., Parent, N., and Shapka, J. D. (2025). Examining self-regulation and problematic smartphone use in Canadian adolescents: a parallel latent growth modeling approach. J. Youth Adolesc. 54, 468–479. doi: 10.1007/s10964-024-02071-x

Keywords: narcissism, emotion regulation strategies, FoMO, need for touch, sensory-motivational mechanisms, haptic reinforcement, addiction, I-PACE

Citation: Giancola M, Perazzini M, Bontempo D, Perilli E and D'Amico S (2025) Don't touch my smartphone! The psychological and sensory-motivational factors of problematic smartphone and social media use in emerging adulthood. Front. Dev. Psychol. 3:1617529. doi: 10.3389/fdpys.2025.1617529

Received: 24 April 2025; Revised: 10 November 2025;

Accepted: 13 November 2025; Published: 27 November 2025.

Edited by:

Elisa Di Giorgio, University of Padua, ItalyCopyright © 2025 Giancola, Perazzini, Bontempo, Perilli and D'Amico. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marco Giancola, bWFyY28uZ2lhbmNvbGFAdW5pdmFxLml0

Marco Giancola

Marco Giancola Matteo Perazzini

Matteo Perazzini Danilo Bontempo

Danilo Bontempo Enrico Perilli

Enrico Perilli Simonetta D'Amico

Simonetta D'Amico