Abstract

Wearable technologies mark a transition in healthcare evolution, from paternalistic (Healthcare 1.0) to reactive (Healthcare 2.0), proactive (Healthcare 3.0), and data-integrated care (Healthcare 4.0). The next stage, Healthcare 5.0, envisions the seamless integration of human and pet health data, fostering a more holistic approach to disease prevention and management. In this viewpoint, we explore the disruptive potential of integrating health monitoring between humans and pets through wearable technology, highlighting the interconnected nature of human-pet health. We examine the parallel evolution of human and pet health monitoring, assessing current technologies and their potential to enhance both fields. We discuss that wearable technologies not only improve chronic disease management but also enable early detection of zoonotic and emerging diseases. Additionally, we emphasize the potential re-usability of human wearable devices for pets, outlining the associated technical challenges. This can lower costs and accelerate adoption, offering mutual benefits for both domains. We address the need for an integrated, linked platform that enables real-time data analysis. Data integration ultimately results in better diagnostic accuracy, optimized treatment plans, and enhanced quality of life for humans and pets. Re-purposing wearables for human-pet health monitoring enables real-time data collection, predictive analytics, and prevention to accelerate the implementation of Healthcare 5.0.

1 Introduction

1.1 Health holistic approaches

Humans and their furry companions share a unique bond and encounter a range of similar health concerns. Despite thousands of households worldwide welcoming pets, there is still an absence of integrated health monitoring systems jointly addressing the well-being of both [1]. Quality of life (QoL), both physical and mental, as well as perspectives on health, well-being, safeguarding, and environmental factors, require holistic and interdisciplinary approaches. In this context, QoL as defined by the WHOQOL framework, encompasses physical, psychological, social, and environmental dimensions [2]. Wearables and connected technologies extend QoL assessment beyond episodic encounters to continuous, context-aware monitoring of sleep, mobility, and participation. In human-companion-animal ecosystems, shared environments and daily routines link animal welfare directly to human QoL, enabling earlier detection of decline and more targeted interventions. These approaches emphasize the interconnected relationship between humans, animals, and the environment [3]. Three influential concepts of One Health, EcoHealth, and Planetary Health, illustrate this linkage. Although they share foundational elements and conceptual similarities, they differ in their focus and scope [4]. One Health aims to improve well-being by preventing risks and mitigating crises at the human-animal-environment interface and emphasizes a whole-of-society approach [5, 6]. EcoHealth extends this perspective by explicitly integrating environmental sustainability and socioeconomic stability [7]. Planetary Health, while less interdisciplinary, concentrates primarily on human health within environmental boundaries [4]. Despite these differences, all frameworks converge on a central message: human, animal, and environmental health are inseparable, and technological advances must reflect this interconnectedness to achieve meaningful impact.

1.2 Bridging the paradigms and technologies: one digital health

In 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO) released a comprehensive taxonomy of Digital Health, identifying numerous aspects of this rapidly expanding field [8]. Investments in Digital Health are substantial, for example, reaching $6 billion in 2017 [9], reflecting its potential to enhance healthcare delivery and support public health systems [10]. Digital Health interventions increasingly benefit humans, animals, and ecosystems [11] by leveraging two primary dimensions: (i) real-time big data streams and (ii) wearable and tracking technologies that strengthen disease surveillance, early-warning systems, preparedness, and response by integrating traditional surveillance with new data sources [12].

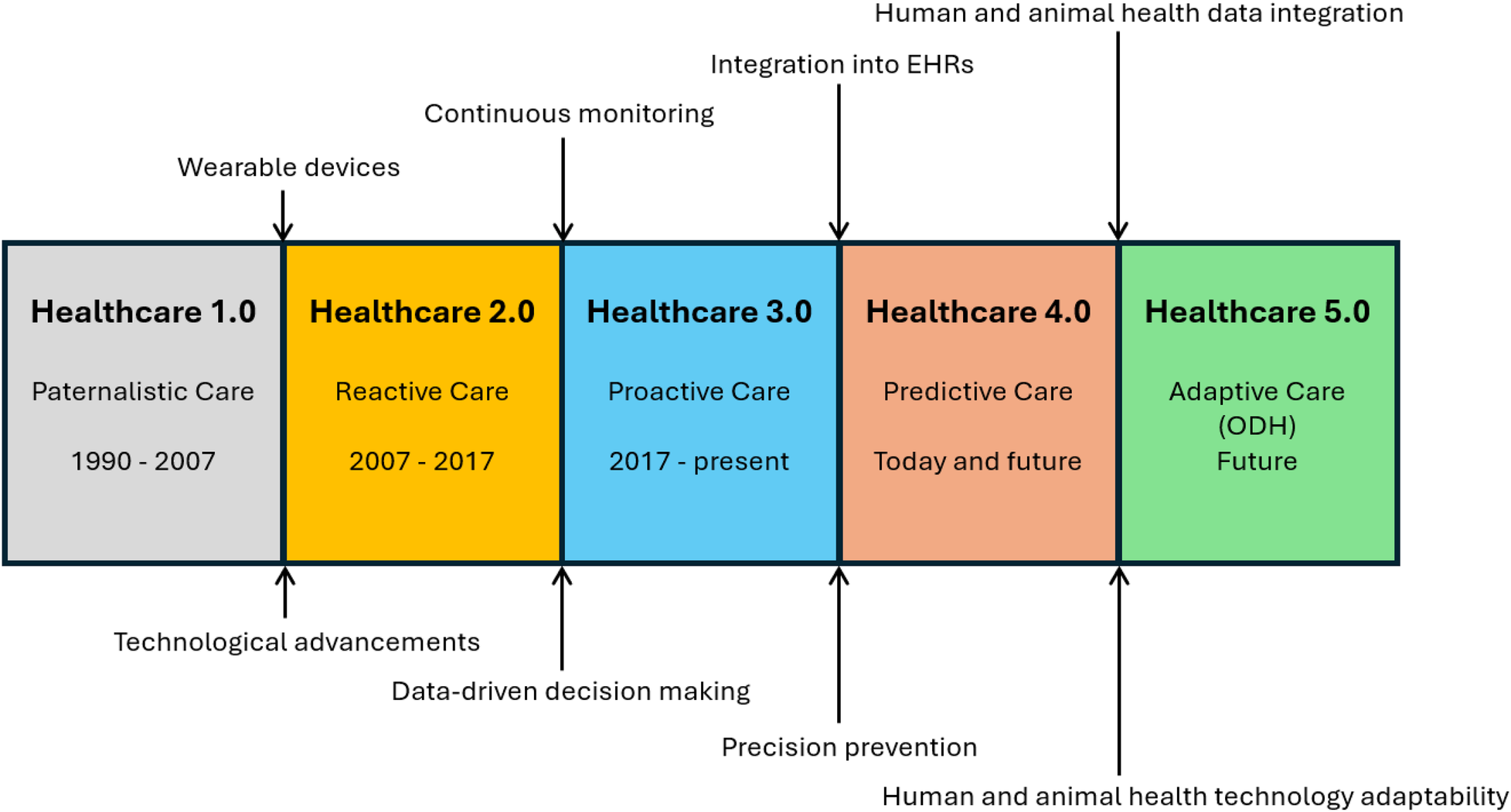

The One Digital Health (ODH) concept bridges the gap between holistic health approaches and technological advancements [13]. ODH defines the components of the digital health ecosystem and explores how emerging technologies can support healthcare delivery and promote overall well-being across species. A central aspect of ODH is the integration of human and veterinary medical data into real-time information systems, an essential step in advancing public health, particularly where human and animal environments intersect. Historically, healthcare was delivered in a largely paternalistic manner (Healthcare 1.0); With the implementation of wearable devices, the paradigm shifted to reactive care (Healthcare 2.0); Continuous monitoring enabled proactive care (Healthcare 3.0), and is already pushing the field toward predictive care (Healthcare 4.0); By the integration of human and animal health data, we will approach Healthcare 5.0 (Figure 1) [14, 15].

Figure 1

Wearable technology is a key in Healthcare evolution, enabling continuous monitoring, data integration into EHRs, and fostering the convergence of human and animal health data. Healthcare 5.0 yields adaptive care across species.

In this viewpoint, we examine the role of wearable technologies across five key areas of (i) management of chronic conditions, (ii) monitoring physical activity, (iii) behavioral and mental health, (iv) early disease detection, and (v) clinical applications. We emphasize ODH contributions to the health of humans and companion animals (specifically dogs and cats) and highlight how interconnected data streams reveal cross-species insights, such as identifying common stressors. We also discuss technical challenges and opportunities in adapting human wearables for animal use. Finally, we outline a roadmap for advancing integrated, cross-species wearable health monitoring systems.

2 Human and pet health: a parallel journey

2.1 Human-pet interaction, health, and its implications

In 2024, 46% of German households (18.45 million homes) host a pet [16], most commonly dogs and cats, followed by small mammals, such as rabbits and guinea pigs, birds, fish, and reptiles [16]. The German pet market increased by €4 billion in two decades to €7.1 billion in 2023 [16]. Pet owners increasingly consider their pets as integral family members [17], showing the importance of pet health, which directly extends to the QoL of owners and the broader community [18, 19], particularly when managing chronically ill pets with conditions like epilepsy, diabetes, allergy, cardiovascular diseases, dementia, and cancer [20]. Pets in poor health often trigger a domino effect, ranging from rising pet health insurance premiums to affecting the well-being of pet owners. Neurological conditions such as epileptic seizures particularly strain owners emotionally, not only because of their episodic nature but also due to medication side effects and clinical signs including ataxia, sedation, and behavioral changes [21, 22].

2.2 Shared metrics and benefits

“We are more alike than we might think.”

2.2.1 Overlapping health parameters

The parallels between humans and animals extend far beyond emotional connection and companionship. Companion animals, much like humans, face many of the same environmental stressors, including air pollution and noise, along with socioeconomic influences contributing to their health and well-being [23]. Whether engaging in the same physical activity or exchanging countless gut microbes, companion animals accurately reflect human well-being [24]. These shared physiological markers are detected through different sensing modalities and mechanisms such as Photoplethysmography (PPG), Electrocardiography (ECG) derive heart rate and heart rate variability (HRV) by measuring changes in blood volume or electrical cardiac activity; acoustic sensors capture subtle mechanical vibrations associated with pulse and breathing; accelerometers detect movement, gait, posture, and sleep–wake cycles through motion signatures; and temperature sensors measure peripheral thermoregulation and fever-related changes. Because the same physical principles apply across species, the resulting signals are directly comparable, enabling unified interpretation of stress, activity, rest quality, and early deviations from baseline in both humans and companion animals. This creates a comparable dataset that allows shared stressors or early signs of decline to be detected objectively across humans and pets.

Over the past few years, smart collars for dogs and cats have gained popularity as they enable remote, non-invasive, and continuous monitoring of vital signs. Latest devices integrate thermometers for measuring temperature, acoustic sensors for pulse, HRV, and respiratory acquisition, accelerometers for activity, calories, and posture detection, and global positioning systems (GPSs) for location and tracking [25]. These devices track various behaviors, including scratching, licking, sleeping, eating, drinking, running, walking, and resting. Analyzing such data provides insights into a pet’s overall health. For instance, increased licking or scratching suggests allergies or dermatological conditions [26], while reduced activity or restlessness indicates discomfort [27] from conditions such as osteoarthritis, cardiovascular disease, or neurological disorders [28]. Abnormal eating or drinking patterns indicate metabolic disorders, such as feline hyperthyroidism or canine hyper-adrenocorticism [29]. Changed walking or running patterns indicate pain, fatigue, epilepsy, or feline urethral obstruction [30]. By quantifying these behaviors through sensors, wearables translate clinical or subclinical signs into continuous digital biomarkers, enabling earlier intervention and facilitating cross-species comparison of lifestyle, stress, and disease patterns.

2.2.2 Common diseases between humans and pets

Owning a companion animal contributes to various health benefits, including regular physical activity and enhanced mental well-being [31]. However, it is crucial to acknowledge the potential downsides, including numerous zoonotic pathogens that companion animals transmit to humans, directly or indirectly. For instance, soil-transmitted helminth infections by various species of parasitic worms are among the most common worldwide [32]. Dogs and cats play a major role in contaminating the environment and potentially serve as reservoirs for infections in humans. Additionally, a fatal viral disease like rabies can be transmitted through a bite, mainly by domestic dogs [33]. Cats are carriers of toxoplasmosis, caused by the single-celled parasite Toxoplasma gondii [34]. Cystic echinococcosis is another severe, occasionally fatal parasitic disease caused by the larval cystic stage of the dog tapeworm Echinococcus granulosus [35]. In addition to zoonotic diseases (animal-to-human), we need to consider reverse zoonosis, causing (human-to-animal) harm. Examples are influenza, SARS-CoV-2, and Monkeypox viruses [36]. Wearables cannot detect pathogens directly, but by monitoring early physiological deviations, such as fever, reduced mobility, abnormal respiration, or sleep disruption, they provide an important layer of early-warning signals in both humans and pets, complementing traditional public-health surveillance systems.

3 Integration of health monitoring

3.1 Wearable devices for connected health

Connected Health is a patient-centred model that encompasses wireless, digital, electronic, mobile, and tele-health solutions, in which devices, services, or interventions are designed around patients’ needs and health data are shared to enable proactive and efficient care [37]. Within this paradigm, telemedicine is a core component that enables quicker and more efficient diagnosis and clinical care by bridging physical distances and extending spatial-temporal monitoring [38]. Wearable technologies such as fitness trackers, smart watches, wearable ECG recorders, and smart clothing facilitate real-time, non-invasive monitoring of health parameters (e.g., vital signs) [39, 40]. Offering real-time feedback, wearables are an objective tool and beneficial for the elderly, rehabilitation, and those with disabilities. Furthermore, wearables facilitate home-based rehabilitation and save over $200 billion in healthcare costs by reducing clinician-patient interaction time as well as transportation efforts [41].

Smart devices help managing sleep [42], stress [43], productivity, and chronic diseases [44], detect depression, and monitor activities [45]. Wearables have applications in stroke recovery [46], assessing muscle activity [47], and bear the potential to replace magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for brain activity monitoring [48]. In chronic conditions like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), wireless pulse oximeters enhance self-management and reduce hospital admissions. Apple’s ECG has received Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European approval, indicating wearables’ growing importance [49]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, wearables aided in remote monitoring and consultations for chronic and post-COVID conditions [50].

3.2 Wearable devices for pets

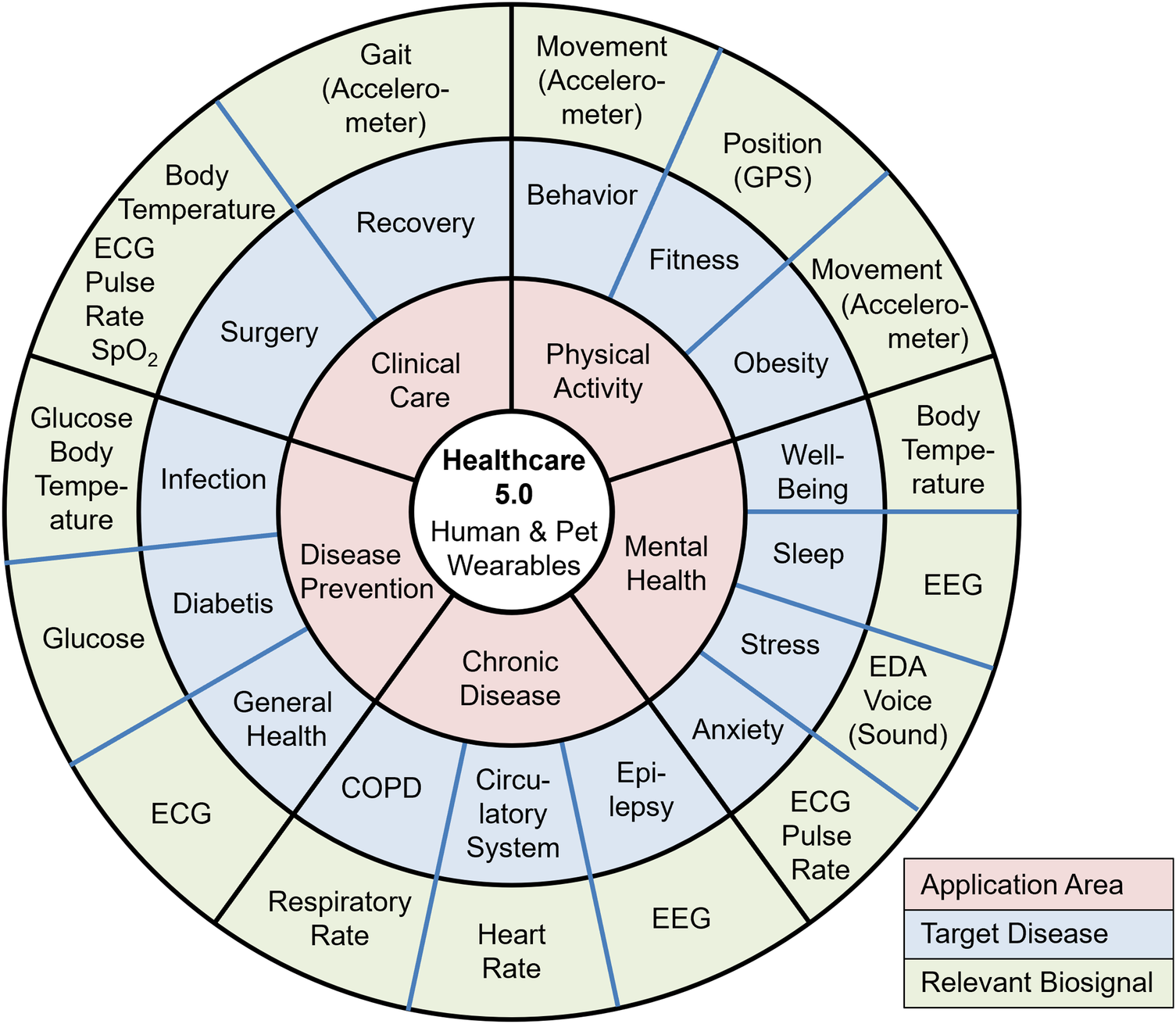

The global market in wearables for pets was $2.70 billion in 2023 and is expected to grow by 14.3% from 2024 to 2030 [51]. Wearable devices for companion animals increasingly enable continuous and remote health monitoring, conceptually analogous to human Remote Patient Monitoring Systems (RPMS), although the terminology is not yet standardized in veterinary medicine [52, 53]. Figure 2 provides an overview of the cross-species mapping between biosignals, representative conditions, and major applications. It visualizes the cross-species health ecosystem enabled by wearable technologies through mapping three interconnected layers: application areas (inner ring), target diseases or conditions (middle ring), and the biosignals required to monitor them (outer ring). This structure shows the direct linkage between measurable physiological markers such as heart rate, respiratory rate, glucose, sleep, or movement and specific clinical or behavioral conditions relevant to both humans and companion animals. By organizing these elements around the Healthcare 5.0 framework, the figure illustrates how shared biosignals enable unified approaches to chronic disease management, mental health assessment, physical activity monitoring, clinical care, and disease prevention across species. One of the primary applications is monitoring physical activity. Equipped with accelerometers and GPS, pet devices provide detailed data to support the management of obesity and ensure sufficient exercise [54]. Deviations from normal activity patterns signal underlying health issues. According to Chambers et al., wearable accelerometers accurately quantify the intensity and duration of physical activity in dogs, thereby aiding in weight management and maintaining physical fitness [55]. Wearable technologies further promise to detect and manage chronic conditions in pets. In particular, their applications for monitoring canine epilepsy collect objective data on seizure frequency and duration, which supports more informed and individualized treatment planning [56]. Similarly, Oliveira et al. employ wearable pulse oximeters and heart rate monitors to manage respiratory and cardiovascular conditions [57].

Figure 2

Healthcare 5.0 supported by wearables. Red: main application area; Blue: target disease; Green: relevant biosignal. Application-centered map of reusable human pet wearables across five primary domains: clinical care (post-op recovery, vital-sign surveillance), physical activity (activity profiling, gait), disease prevention (early anomaly detection, exposure/risk monitoring), chronic disease (cardiometabolic and respiratory follow-up), and mental health (stress, affective state). Each application links to representative conditions/indicators (e.g., respiratory dysfunction, mobility/ataxia, insomnia, anxiety) and their enabling biosignals/modalities such as ECG, IMU/accelerometry, EEG, EDA, and skin temperature. This depicts interoperability and bidirectional reusability of sensing and data across species within telemedicine-like connected-health pathways toward Healthcare 5.0.

Another application is in the early detection of diseases and health anomalies. Brugarolas et al. explore the use of wearable biosensors in detecting physiological changes correlated to stress, allowing for earlier interventions [58]. Foster et al. demonstrate the feasibility of reconstructing ECG, heart rate, respiration rate, and body movement of dogs during rest and sleep [59]. Moreover, behavioral monitoring using wearable devices detects anxiety, enabling timely behavioral interventions [60]. Similarly, tracking sleep patterns and restlessness in pets provides insights into their mental health and overall well-being [61].

Wearables also support the management of specific health conditions. For example, in diabetic pets, continuous glucose monitoring through wearable devices enables better disease control [62]. These devices assist veterinary surgeons in tracking disease progression and assessing therapeutic outcomes. Engelsman et al. demonstrate effective gait analysis to quantify ataxia in dogs [63].

3.3 Recognizing the disconnect in human and pet health monitoring

3.3.1 Major challenges

Technology and tools: Technological progress in health monitoring differs between humans and pets. Humans have access to sophisticated, high-performance devices, whereas pet health monitoring remains more limited and often passive [64]. Although pets benefit from the evolution from Healthcare 1.0 to 4.0 such as wearables, telemedicine, data-driven care, platform integration, and preventive approaches [65], the veterinary domain still does not realize the full potential of Healthcare 4.0.

Data availability and integration: Human healthcare emphasizes continuous data collection, multimodal analysis, and integration of diverse data streams for preventive care and early disease detection. For example, Accident and Emergency Informatics (A&EI) uses the International Standard Accident Number (ISAN) to securely exchange private data across silos [66]. In contrast, pet health relies largely on intermittent evaluations at veterinary visits, and information from different sources including veterinary records, home monitoring, and dietary data, remains fragmented [67].

Accessibility and affordability: While advanced technologies for humans are widely available and relatively cost-effective, equivalent pet technologies are less accessible and often more expensive, limiting adoption among pet owners.

3.3.2 Boosting factors

Lack of data protection for pets: The implementation of robust data protection frameworks such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) challenge researchers in sharing and utilizing personal health data [68]. While these measures are important for protecting personal data, as enshrined in the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, there are no specific data protection rights for animals. We see this gap as an opportunity for researchers to boost veterinary medicine and Healthcare 5.0.

4 Perspective and roadmap

4.1 Connected human and pet health

4.1.1 Human wearables for pets

Although the anatomy of humans and animals differs, human wearables are repurposed for pets. This is an initial step to overcome current limitations, such as passive monitoring, availability, and affordability. A major challenge is adapting size, shape, and fit to different anatomies, ensuring comfort, safety, and irritation-free use [69]. Devices must be durable, non-toxic, and hypoallergenic, given pets’ active behavior and sensitive skin. Accurate monitoring requires sensor recalibration to pet-specific baselines, and integration with veterinary systems is important for meaningful use. Extended battery life with secure casing is critical to avoid accidental ingestion. Lastly, adapting human wearables for pets must account for animal-specific regulatory and ethical standards. This adoption also creates a symbiotic relationship where advancements in one domain benefit the other, enhancing device functionality and reliability across the board.

4.1.2 Primary challenges

Among the various non-invasive and non-intrusive biomedical sensors and techniques, we focus on PPG and ECG. Both are popular and commonly used in human as well as veterinary medicine.

Anatomical variety: Wearable devices must accommodate substantial inter- and intra-species differences in breed, size, shape, behavior, skin type, and health needs. For example, dogs range from tiny Chihuahuas to large Great Danes, requiring adjustable straps and multiple size options. Different body shapes (e.g., slim Whippet vs. broad-chested Bulldog) and activity levels (e.g., high-energy Border Collie vs. low-activity Basset Hound) demand different design priorities. Certain breeds present specific challenges, brachycephalic dogs with respiratory issues or Dachshunds with spinal problems. Skin and fur characteristics also influence materials, such as the folded skin of Shar Peis, dense fur of Maine Coons, or hairless breeds like Sphynx cats.

Recording concepts: Fur lengths, densities, and skin properties [70] affect sensor performance. ECG electrodes require reliable skin contact through fur, potentially using needle or conductive rubber electrodes. Proper placement and secure attachment (special harnesses, elastic bands) help maintain signal quality while preventing discomfort or irritation [71].

Technical design: PPG sensors must be adapted for fur and skin variability, including wavelength and light-intensity optimization. Human PPG typically uses 660 nm (red) and 940 nm (IR), but wavelengths between 700–900 nm may be more effective for pets [72]. Experiments by Cugmas et al. show that placing sensors in less furry regions (ear, paw) improves reliability [70].

Signal processing: Breeds differ in physiological ranges, requiring calibration and tailored filtering to address higher noise and baseline wander. Dogs and cats exhibit higher heart and respiratory rates than humans [73, 74], and motion artifacts are more pronounced due to erratic movement, necessitating robust artifact-reduction algorithms.

4.1.3 Data sharing and integrated platform

In addition to wearable devices, components such as data integration, analysis, decision-making, and secure data sharing remain underdeveloped. To date, no unified data platform exists that integrates health data from humans and animals (pets). Such a platform yields substantial advantages. By enabling data exchange between veterinary and human healthcare providers, it enhances clinical decision-making. Comprehensive health records across species lead to informed diagnoses and personalized treatments. Additionally, pet owners who actively manage and share their health data foster a collaborative healthcare environment where information flows efficiently. To ensure interoperability in pet-human wearable healthcare, we need to establish standards such as Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR). Beyond technical integration, ethical and regulatory considerations are essential for real-world deployment. Companion animals do not fall under human-focused data protection frameworks such as GDPR, yet responsible data governance, informed consent from owners, and transparent data-use policies remain critical for trust and adoption. Harmonized standards for interoperability, data formats, and device certification will be necessary to ensure safe, reliable, and scalable cross-species health data exchange.

4.2 Convergence towards Healthcare 5.0

Transitioning from a subject-to-device paradigm (hospital-centered), where technology is primarily confined to clinical settings, to a device-to-subject (patient-centered) approach has empowered individuals [75] and, increasingly, animals to participate actively in their health management. Wearable devices that continuously monitor environmental, behavioral, physiological, and psychological parameters have facilitated this shift [2]. The seamless integration of data from these devices into electronic health records (EHRs) has accelerated the move from Healthcare 2.0, characterized by data-driven decision making, towards a more proactive Healthcare 3.0. Other important technologies used in this revolution are big data analytics, block-chain technologies, artificial intelligence (AI), edge computing, and wearables powered by the Internet of Things (IoT) [76].

Precision prevention [77, 78] as a key component of Healthcare 4.0 relies on detailed personal and, now, even animal health information to tailor interventions. Wearable devices provide granular data on both human and animal health status, facilitate the identification of at-risk populations, and support preventive measures. By collecting data from humans and animals on a large scale, these devices contribute to public health surveillance and the early detection of emerging threats, including zoonotic diseases. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the critical role of wearable technology in tracking disease spread and informing public health interventions [79].

To realize the full potential of wearable devices in ODH, we also need to address ethical considerations. Establishing robust data governance frameworks and ensuring data protection are essential for building trust among users. We further need to develop standardized data formats and protocols to facilitate interoperable data exchange between different healthcare systems and devices across species. Techniques such as federated learning, differential privacy [80], secure multi-party computation [81], homomorphic encryption [82], and trusted execution environments [83] provide insights from private data while maintaining confidentiality. However, these techniques also face challenges such as communication overhead, system and data heterogeneity, and the need for robust security measures to prevent data leakage and model poisoning. By embracing the power of wearable technology and fostering collaboration between human and animal health sectors, we can create a Healthcare 5.0 future where diseases are anticipated, prevented, and managed more effectively for all living beings.

5 Conclusion

Integrating wearable devices into health monitoring enables unified human and pet health management within the ODH framework. Shared health metrics support early detection, chronic condition management, prevention of zoonotic diseases, and quality of life for both humans and animals. Re-purposing human wearables for pets reduces costs and accelerates adoption, promoting mutual benefit. A unified Healthcare 5.0 platform allows comprehensive data analysis for coordinated care, while standardized formats and secure data handling address critical interoperability challenges. Recognizing common environmental stressors further supports proactive, cross-species health strategies. Overall, cohesive integration of wearable technologies fosters healthier, more connected human–animal ecosystems. Most importantly, cross-species data integration creates a shared predictive foundation that enables earlier risk detection, more precise preventive interventions, and a new generation of anticipatory healthcare for both humans and companion animals.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

MH: Visualization, Project administration, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Supervision. SA: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Methodology, Writing – original draft. SK: Writing – review & editing. AJ: Writing – review & editing. SR: Writing – review & editing. NT: Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. TD: Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. HV: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration.

Funding

The author(s) declared financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. We acknowledge the partial support of this work by Hector Stiftung. For the publication fee, we acknowledge financial support by Heidelberg University.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

George J Häsler B Mremi I Sindato C Mboera L Rweyemamu M , et al. A systematic review on integration mechanisms in human and animal health surveillance systems with a view to addressing global health security threats. One Health Outlook. (2020) 2:1–15. 10.1186/s42522-020-00017-4

2.

Whoqol Group. The world health organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): position paper from the world health organization. Soc Sci Med. (1995) 41:1403–9. 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00112-K

3.

Overgaauw PA Vinke CM van Hagen MA Lipman LJ . A one health perspective on the human–companion animal relationship with emphasis on zoonotic aspects. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:3789. 10.3390/ijerph17113789

4.

Lerner H Berg C . A comparison of three holistic approaches to health: one health, ecohealth, and planetary health. front vet sci, 4, 163. Freeman, E., & Richardson, M.(2019). One health: the well-being impacts of humannature relationships. Front Psychol. (2017) 10:1611. 10.3389/fvets.2017.00163

5.

Amuasi JH Lucas T Horton R Winkler AS . Reconnecting for our future: Lancet one health commission. Lancet. (2020) 395:1469–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31027-8

6.

Lerner H Berg C . The concept of health in one health and some practical implications for research and education: what is one health?Infect Ecol Epidemiol. (2015) 5:25300. 10.3402/iee.v5.25300

7.

Rapport DJ . Sustain sci: an ecohealth perspective. Sustain Sci. (2007) 2:77–84. 10.1007/s11625-006-0016-3

8.

World Health Organization. Data from: Global strategy on digital health 2020–2025. PDF (2021). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/documents/gs4dhdaa2a9f352b0445b afbc79ca799dce4d.pdf (accessed July 9, 2025).

9.

Rock Health. Data from: 2017 year-end funding report: the end of the beginning of digital health (2017). Available online at: https://rockhealth.com/insights/2017-year-end-funding-report-the-end-of-the-beginning-of-digital-health/ (accessed July 9, 2025).

10.

World Health Organization. Data from: Who guideline: recommendations on digital interventions for health system strengthening (2024). Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550505 (accessed July 9, 2025)

11.

Benis A Haghi M Deserno TM Tamburis O . One digital health intervention for monitoring human and animal welfare in smart cities: viewpoint and use case. JMIR Med Inform. (2023) 11:e43871. 10.2196/43871

12.

Ezenwaji CO Alum EU Ugwu OPC . The role of digital health in pandemic preparedness and response: securing global health?Glob Health Action. (2024) 17:2419694. 10.1080/16549716.2024.2419694

13.

Benis A Tamburis O Chronaki C Moen A . One digital health: a unified framework for future health ecosystems. J Med Internet Res. (2021) 23:e22189. 10.2196/22189

14.

Chen C Loh EW Kuo KN Tam KW . The times they are a-changin’–healthcare 4.0 is coming!. J Med Syst. (2020) 44:40. 10.1007/s10916-019-1513-0

15.

Li J Carayon P . Health care 4.0: a vision for smart and connected health care. IISE Trans Healthc Syst Eng. (2021) 11:171–80. 10.1080/24725579.2021.1884627

16.

Zentralverband Zoologischer Fachbetriebe Deutschlands (ZZF). Data from: Die entwicklung des heimtiermarktes (n.d.). Available online at: https://www.zzf.de/marktdaten/entwicklung-des-heimtiermarktes (accessed February 5, 2025).

17.

Tierärzte Atlas Deutschland. Data from: Tierärzte atlas deutschland (2024). Available online at: https://www.tieraerzteatlas.de/pdf2024/ (accessed February 5, 2025).

18.

Cusack O , Pets and Mental Health. New York: Routledge (2014).

19.

Johnson RA , The Health Benefits of Dog Walking for Pets and People: Evidence and Case Studies. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press (2011).

20.

Christiansen SB Kristensen AT Sandøe P Lassen J . Looking after chronically ill dogs: impacts on the Caregiver’s life. Anthrozoös. (2013) 26:519–33. 10.2752/175303713X13795775536174

21.

Bongers J Gutierrez-Quintana R Stalin CE . The prospects of non-eeg seizure detection devices in dogs. Front Vet Sci. (2022) 9:896030. 10.3389/fvets.2022.896030

22.

Pergande AE Belshaw Z Volk HA Packer RM . “we have a ticking time bomb”: a qualitative exploration of the impact of canine epilepsy on dog owners living in England. BMC Vet Res. (2020) 16:1–9. 10.1186/s12917-020-02669-w

23.

Magouras I Brookes VJ Jori F Martin A Pfeiffer DU Dürr S . Emerging zoonotic diseases: should we rethink the animal–human interface?Front Vet Sci. (2020) 7:582743. 10.3389/fvets.2020.582743

24.

Maugeri A Medina-Inojosa JR Kunzova S Barchitta M Agodi A Vinciguerra M , et al. Dog ownership and cardiovascular health: results from the Kardiovize 2030 project. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. (2019) 3:268–75. 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2019.07.007

25.

Whistle. Data from: Whistle GPS pet tracker and activity monitor for pets — whistle store (2024). Available online at: https://www.whistle.com/ (accessed July 25, 2024).

26.

Carson A Kresnye C Rai T Wells K Wright A Hillier A . Response of pet owners to whistle fit® activity monitor digital alerts of increased pruritic activity in their dogs: a retrospective observational study. Front Vet Sci. (2023) 10:1123266. 10.3389/fvets.2023.1123266

27.

Mills DS Demontigny-Bédard I Gruen M Klinck MP McPeake KJ Barcelos AM , et al. Pain and problem behavior in cats and dogs. Animals (Basel). (2020) 10:318. 10.3390/ani10020318

28.

PetMD. Data from: Neurological disorders in dogs (2025). Available online at: https://www.petmd.com/dog/conditions/neurological/neurological-disorder s-dogs (accessed July 9, 2025).

29.

Radosta L . Behavior changes associated with metabolic disease of dogs and cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. (2024) 54:17–28. 10.1016/j.cvsm.2023.08.004

30.

Gernone F Uva A Cavalera MA Zatelli A . Neurogenic bladder in dogs, cats and humans: a comparative review of neurological diseases. Animals (Basel). (2022) 12:3233. 10.3390/ani12233233

31.

Martins CF Soares JP Cortinhas A Silva L Cardoso L Pires MA , et al. Pet’s influence on humans’ daily physical activity and mental health: a meta-analysis. Front Public Health. (2023) 11:1196199. 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1196199

32.

World Health Organization. Data from: Soil-transmitted helminth infections (2025). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/soil-transmitted-helmi nth-infections (accessed July 9, 2025).

33.

Knobel DL Hampson K Lembo T Cleaveland S Davis A . Dog rabies and its control. In: Fooks AR, Jackson AC, editors. Rabies. Amsterdam: Elsevier (2020). p. 567–603.

34.

Lafrance-Girard C Arsenault J Thibodeau A Opsteegh M Avery B Quessy S . Toxoplasma gondii in retail beef, lamb, and pork in Canada: prevalence, quantification, and risk factors from a public health perspective. Foodborne Pathog Dis. (2018) 15:798–808. 10.1089/fpd.2018.2479

35.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data from: Echinococcosis — CDC (2024). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/echinococcosis/about/about-cystic-echinococcosis-ce.html (accessed July 2, 2025).

36.

Chakraborty C Bhattacharya M Islam MA Zayed H Ohimain EI Lee SS , et al. Reverse zoonotic transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and monkeypox virus: a comprehensive review. J Microbiol. (2024) 62:337–54. 10.1007/s12275-024-00138-9

37.

Caulfield BM Donnelly SC . What is connected health and why will it change your practice?QJM: Int J Med. (2013) 106:703–7. 10.1093/qjmed/hct114

38.

Omboni S . Connected health: in the right place at the right time. Conn Health Telemed. (2021) 1:1–6. 10.20517/ch.2021.01

39.

Masoumian Hosseini M Masoumian Hosseini ST Qayumi K Hosseinzadeh S Sajadi Tabar SS . Smartwatches in healthcare medicine: assistance and monitoring; a scoping review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. (2023) 23:248. 10.1186/s12911-023-02350-w

40.

Muhammad Sayem AS Hon Teay S Shahariar H Luise Fink P Albarbar A . Review on smart electro-clothing systems (secss). Sensors (Basel). (2020) 20:587. 10.3390/s20030587

41.

Vijayan V Connolly JP Condell J McKelvey N Gardiner P . Review of wearable devices and data collection considerations for connected health. Sensors (Basel). (2021) 21:5589. 10.3390/s21165589

42.

Scott H Lack L Lovato N . A systematic review of the accuracy of sleep wearable devices for estimating sleep onset. Sleep Med Rev. (2020) 49:101227. 10.1016/j.smrv.2019.101227

43.

Hickey BA Chalmers T Newton P Lin CT Sibbritt D McLachlan CS , et al. Smart devices and wearable technologies to detect and monitor mental health conditions and stress: a systematic review. Sensors (Basel). (2021) 21:3461. 10.3390/s21103461

44.

Jafleh EA Alnaqbi FA Almaeeni HA Faqeeh S Alzaabi MA Al Zaman K , et al. The role of wearable devices in chronic disease monitoring and patient care: a comprehensive review. Cureus. (2024) 16:e68921. 10.7759/cureus.68921

45.

Guo F Li Y Kankanhalli MS Brown MS . An evaluation of wearable activity monitoring devices. In: Proceedings of the 1st ACM International Workshop on Personal Data Meets Distributed Multimedia (2013). p. 31–4.

46.

Choudhury S Singh R Shobhana A Sen D Anand SS Shubham S , et al. A novel wearable device for motor recovery of hand function in chronic stroke survivors. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. (2020) 34:600–8. 10.1177/1545968320926162

47.

Ranavolo A Draicchio F Varrecchia T Silvetti A Iavicoli S . Wearable monitoring devices for biomechanical risk assessment at work: current status and future challenges—a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2018) 15:2001. 10.3390/ijerph15092001

48.

Holmes N Rea M Hill RM Leggett J Edwards LJ Hobson PJ , et al. Enabling ambulatory movement in wearable magnetoencephalography with matrix coil active magnetic shielding. Neuroimage. (2023) 274:120157. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2023.120157

49.

Apple Inc. Data from: Apple healthcare (2025). Available online at: https://www.apple.com/healthcare/ (accessed July 9, 2025).

50.

Santos MD Roman C Pimentel MA Vollam S Areia C Young L , et al. A real-time wearable system for monitoring vital signs of COVID-19 patients in a hospital setting. Front Digit Health. (2021) 3:630273. 10.3389/fdgth.2021.630273

51.

Grand View Research. Data from: Pet wearable market size, share & growth report, 2030 (2024). Available online at: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/pet-wearable-market (accessed July 8, 2024).

52.

Zhao X Tanaka R Mandour AS Shimada K Hamabe L . Remote vital sensing in clinical veterinary medicine: a comprehensive review of recent advances, accomplishments, challenges, and future perspectives. Animals. (2025) 15:1033. 10.3390/ani15071033

53.

Abu-Seida AM Abdulkarim A Hassan MH . Veterinary telemedicine: a new era for animal welfare. Open Vet J. (2024) 14:952. 10.5455/OVJ.2024.v14.i4.2

54.

Morrison R Penpraze V Beber A Reilly J Yam P . Associations between obesity and physical activity in dogs: a preliminary investigation. J Small Anim Pract. (2013) 54:570–4. 10.1111/jsap.12142

55.

Chambers RD Yoder NC Carson AB Junge C Allen DE Prescott LM , et al. Deep learning classification of canine behavior using a single collar-mounted accelerometer: real-world validation. Animals (Basel). (2021) 11:1549. 10.3390/ani11061549

56.

Muñana KR Nettifee JA Griffith EH Early PJ Yoder NC . Evaluation of a collar-mounted accelerometer for detecting seizure activity in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. (2020) 34:1239–47. 10.1111/jvim.15760

57.

Oliveira RG Correia PM Silva AL Encarnação PM Ribeiro FM Castro IF , et al. Development of a new integrated system for vital sign monitoring in small animals (Basel). Sensors (Basel). (2022) 22:4264. 10.3390/s22114264

58.

Brugarolas R Latif T Dieffenderfer J Walker K Yuschak S Sherman BL , et al. Wearable heart rate sensor systems for wireless canine health monitoring. IEEE Sens J. (2015) 16:3454–64. 10.1109/JSEN.2015.2485210

59.

Foster M Wang J Williams E Roberts DL Bozkurt A . Inertial measurement based heart and respiration rate estimation of dogs during sleep for welfare monitoring. In: Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Animal-Computer Interaction (2020). p. 1–6.

60.

Ahn J Kwon J Nam H Jang HK Kim JI . Pet buddy: a wearable device for canine behavior recognition using a single IMU. In: 2016 International Conference on Big Data and Smart Computing (BigComp). IEEE (2016). p. 419–22.

61.

Schork IG Manzo IA Oliveira MRB Costa FV Young RJ De Azevedo CS . Testing the accuracy of wearable technology to assess sleep behaviour in domestic dogs: a prospective tool for animal welfare assessment in kennels. Animals (Basel). (2023) 13:1467. 10.3390/ani13091467

62.

Moretti S Tschuor F Osto M Franchini M Wichert B Ackermann M , et al. Evaluation of a novel real-time continuous glucose-monitoring system for use in cats. J Vet Intern Med. (2010) 24:120–6. 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2009.0425.x

63.

Engelsman D Sherif T Meller S Twele F Klein I Zamansky A , et al. Measurement of canine ataxic gait patterns using body-worn smartphone sensor data. Front Vet Sci. (2022) 9:912253. 10.3389/fvets.2022.912253

64.

Byrne C Logas J . The future of technology and computers in veterinary medicine. Diagn Ther Vet Dermatol. (2021) 245–50. 10.1002/9781119680642.ch26

65.

Tauseef M Rathod E Nandish S Kushal M . Advancements in pet care technology: a comprehensive survey. In: 2024 4th International Conference on Data Engineering and Communication Systems (ICDECS). IEEE (2024). p. 1–6.

66.

Haghi M Barakat R Spicher N Heinrich C Jageniak J Öktem GS , et al. Automatic information exchange in the early rescue chain using the international standard accident number (ISAN). In: Deserno TM, Haghi M, Al-Shorbaji N, editors. Healthcare. Vol. 9. MDPI (2021). p. 996.

67.

Houe H Nielsen SS Nielsen LR Ethelberg S Mølbak K . Opportunities for improved disease surveillance and control by use of integrated data on animal and human health. Front Vet Sci. (2019) 6:301. 10.3389/fvets.2019.00301

68.

Harper S Mehrnezhad M Leach M . Security and privacy of pet technologies: actual risks vs user perception. Front Internet Things. (2023) 2:1281464. 10.3389/friot.2023.1281464

69.

Paci P Mancini C Price BA . Understanding the interaction between animals (Basel) and wearables: the wearer experience of cats. In: Proceedings of the 2020 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference (2020). p. 1701–12.

70.

Cugmas B Štruc E Spigulis J . Photoplethysmography in dogs and cats: a selection of alternative measurement sites for a pet monitor. Physiol Meas. (2019) 40:01NT02. 10.1088/1361-6579/aaf433

71.

Foster M Erb P Plank B West H Russenberger J Gruen M , et al. 3D-printed electrocardiogram electrodes for heart rate detection in canines. In: 2018 IEEE Biomedical Circuits and Systems Conference (BioCAS). IEEE (2018). p. 1–4.

72.

Park J Seok HS Kim SS Shin H . Photoplethysmogram analysis and applications: an integrative review. Front Physiol. (2022) 12:808451. 10.3389/fphys.2021.808451

73.

Miller M Byfield R Crosby M Schiltz P Johnson PJ Lin J . A wearable photoplethysmography sensor for non-invasive equine heart rate monitoring. Smart Agric Technol. (2023) 5:100264. 10.1016/j.atech.2023.100264

74.

Dijkstra E Teske E Szatmári V . Respiratory rate of clinically healthy cats measured in veterinary consultation rooms. Vet J. (2018) 234:96–101. 10.1016/j.tvjl.2018.02.014

75.

Haghi M Spicher N Wang J Deserno TM . Integrated sensing devices for disease prevention and health alerts in smart homes. In: Deserno TM, Haghi M, Al-Shorbaji N, editors. Accident and Emergency Informatics. Amsterdam: IOS Press (2022). p. 39–61.

76.

Gupta A Singh A . Healthcare 4.0: recent advancements and futuristic research directions. Wirel Pers Commun. (2023) 129:933–52. 10.1007/s11277-022-10164-8

77.

Ramos KS Bowers EC Tavera-Garcia MA Ramos IN . Precision prevention: a focused response to shifting paradigms in healthcare. Exp Biol Med. (2019) 244:207–12. 10.1177/1535370219829759

78.

Greenland P Hassan S . Precision preventive medicine—ready for prime time?JAMA Intern Med. (2019) 179:605–6. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0142

79.

Natarajan A Su HW Heneghan C . Assessment of physiological signs associated with COVID-19 measured using wearable devices. NPJ Digit Med. (2020) 3:156. 10.1038/s41746-020-00363-7

80.

Zia MT Khan MA El-Sayed H . Application of differential privacy approach in healthcare data—a case study. In: 2020 14th International Conference on Innovations in Information Technology (IIT). IEEE (2020). p. 35–9.

81.

Alghamdi W Salama R Sirija M Abbas AR Dilnoza K . Secure multi-party computation for collaborative data analysis. In: E3S Web of Conferences. Vol. 399. EDP Sciences (2023). p. 04034.

82.

Zhang L Xu J Vijayakumar P Sharma PK Ghosh U . Homomorphic encryption-based privacy-preserving federated learning in IoT-enabled healthcare system. IEEE Trans Netw Sci Eng. (2022) 10:2864–80. 10.1109/TNSE.2022.3185327

83.

Li J Luo X Lei H . Trusthealth: enhancing ehealth security with blockchain and trusted execution environments. Electronics (Basel). (2024) 13:2425. 10.3390/electronics13122425

Summary

Keywords

digital technology, Healthcare 5.0, human health, one digital health, one health, pet health, wearable devices

Citation

Haghi M, Abani S, Khooyooz S, Jahanjoo A, Rashidibajgan S, TaheriNejad N, Deserno TM and Volk H (2025) One digital health through wearables: a viewpoint on human–pet integration towards Healthcare 5.0. Front. Digit. Health 7:1668739. doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2025.1668739

Received

18 July 2025

Revised

01 December 2025

Accepted

03 December 2025

Published

18 December 2025

Volume

7 - 2025

Edited by

Varadraj Prabhu Gurupur, University of Central Florida, Orlando, United States

Reviewed by

Lidia Bajenaru, National Institute for Research & Development in Informatics, Romania

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Haghi, Abani, Khooyooz, Jahanjoo, Rashidibajgan, TaheriNejad, Deserno and Volk.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

* Correspondence: Mostafa Haghi mostafa.haghi@ziti.uni-heidelberg.de

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.