Abstract

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) constitutes a rapidly expanding global epidemic whose societal burden is amplified by deep-rooted health inequities. Socio-economic disadvantage, minority ethnicity, low health literacy, and limited access to nutritious food or timely care disproportionately expose under-insured populations to earlier onset, poorer glycaemic control, and higher rates of cardiovascular, renal, and neurocognitive complications. Artificial intelligence (AI) is emerging as a transformative counterforce, capable of mitigating these disparities across the entire care continuum. Early detection and risk prediction have progressed from static clinical scores to dynamic machine-learning (ML) models that integrate multimodal data—electronic health records, genomics, socio-environmental variables, and wearable-derived behavioural signatures—to yield earlier and more accurate identification of high-risk individuals. Complication surveillance is being revolutionised by AI systems that screen for diabetic retinopathy with near-specialist accuracy, forecast renal function decline, and detect pre-ulcerative foot lesions through image-based deep learning, enabling timely, targeted interventions. Convergence with continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) and wearable technologies supports real-time, AI-driven glycaemic forecasting and decision support, while telemedicine platforms extend these benefits to remote or resource-constrained settings. Nevertheless, widespread implementation faces challenges of data heterogeneity, algorithmic bias against minority groups, privacy risks, and the digital divide that could paradoxically widen inequities if left unaddressed. Future directions centre on multimodal large language models, digital-twin simulations for personalised policy testing, and human-in-the-loop governance frameworks that embed ethical oversight, trauma-informed care, and community co-design. Realising AI's societal promise demands coordinated action across patients, clinicians, technologists, and policymakers to ensure solutions are not only clinically effective but also equitable, culturally attuned, and economically sustainable.

1 Introduction

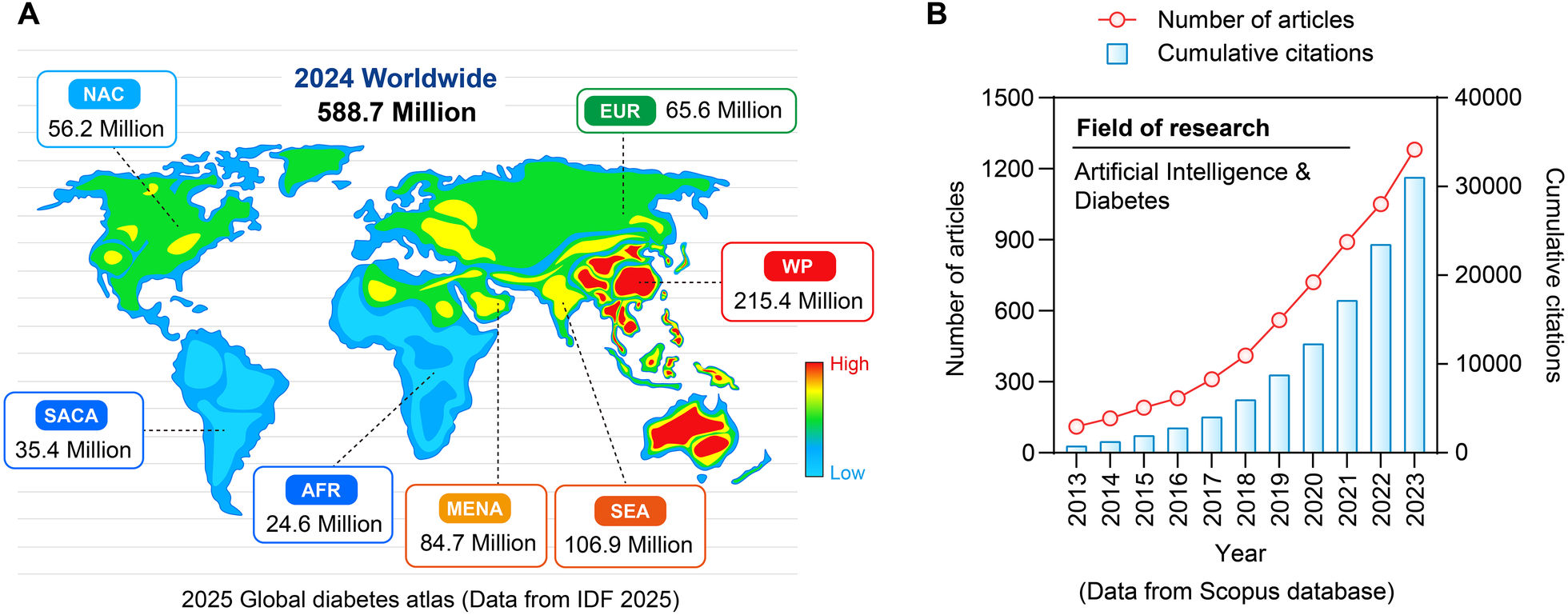

Diabetes's social burden is a complex issue with societal, psychological, and economic facets in addition to personal health consequences. T2DM, in particular, has become a global epidemic that disproportionately affects underinsured people, members of racial and ethnic minorities, and those from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds (1) (Figure 1). Cardiovascular disorders, renal failure, and cognitive decline are among the complications of the disease that worsen its effects on society and put a tremendous burden on healthcare systems and economies around the world (2). Diabetes management and outcomes are greatly influenced by social determinants of health, which frequently reinforce health disparities. These factors include childhood environment, education, socioeconomic status, and access to healthcare (3). The lack of access to wholesome food, rigid healthcare schedules, and low health literacy are some of the obstacles that people from underprivileged backgrounds usually encounter when trying to manage their health effectively. These factors all work together to worsen glycemic control and increase the likelihood of complications (1, 3). The confluence of these elements emphasizes how urgently creative, scalable solutions are needed to alleviate the social burden of diabetes.

Figure 1

Prevalence rate of diabetes in the world and AI issuing trend. (A) Distribution of diabetes patients worldwide in 2024. (B) Research papers and citation situations in the field of “artificial intelligence and diabetes” from 2013 to 2023.

Although this is a narrative review rather than a systematic review, we adhered to a structured approach for literature selection to ensure comprehensiveness and relevance. We conducted a comprehensive search of PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase databases from inception until October 2025, using a combination of keywords and MeSH terms related to “artificial intelligence,” “machine learning,” “diabetes mellitus,” “diabetic complications,” “federated learning,” “digital twin,” and “health equity.”

Studies were included if they: (1) focused on AI/ML applications in diabetes care, including risk prediction, complication monitoring, or personalized interventions; (2) were published in peer-reviewed journals in English; (3) involved human subjects or real-world data; and (4) reported measurable outcomes (e.g., AUC, sensitivity, specificity, clinical impact).

Exclusion criteria included: (1) conference abstracts, editorials, or letters without original data; (2) studies limited to technical model development without clinical relevance; and (3) non-English publications.

After removing duplicates, titles and abstracts were screened by two independent reviewers (BB and HL), with disagreements resolved by consensus. Full texts of potentially relevant articles were assessed for eligibility. In addition, reference lists of key articles and recent high-quality reviews were manually searched to identify additional relevant studies. The final selection was based on thematic relevance, methodological quality, and representation of diverse populations and settings.

With previously unheard-of potential to lessen the disease's societal impact, AI marks a revolutionary shift in the treatment of diabetes. AI-driven technologies have shown great promise in lowering complications, increasing patient engagement, and improving glycemic control. Examples of these technologies include CGM, automated insulin delivery (AID) systems, and predictive analytics (4, 5). It has been demonstrated that AID systems help patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes spend more time within target glucose ranges and lower their HbA1c levels, which lessens the strain of daily self-management (5, 6). Furthermore, AI-powered tools can offer real-time, personalized advice, improving treatment adherence and enabling patients to actively participate in their care (7). Nevertheless, there are certain difficulties in incorporating AI into diabetes care. Thorough monitoring and ethical considerations are required for issues like data privacy, algorithmic bias, and the danger of becoming overly dependent on technology (7, 8). In order to ensure that underprivileged groups profit from these developments, AI adoption must be equitable. The need for standardized, culturally relevant solutions is highlighted by the fact that, although AI-based diabetic retinopathy (DR) screening systems have demonstrated high negative predictive values, their sensitivity varies greatly (8).

AI's potential to alleviate the social burden of diabetes is further enhanced by its convergence with wearable technology and telemedicine. Continuous glycemic level and behavior monitoring is made possible by wearable technology, which also offers real-time feedback that can guide tailored interventions (2). AI in conjunction with social media platforms promotes a cooperative approach to diabetes management by facilitating peer-to-peer support and patient-provider interactions (2). To guarantee their accessibility and scalability, however, extensive clinical trials and cost-effectiveness evaluations are necessary for the broad adoption of these technologies (2). Social determinants of health, systemic barriers to care, and health equity must be given top priority when integrating AI into public health strategies. High-risk populations' ability to manage their diabetes can be improved by trauma-informed care models that take into consideration the psychological and emotional effects of childhood adversity (9). Healthcare professionals can customize interventions to match the specific requirements of various populations by using AI to comprehend and address the larger sociopolitical contexts that influence health behaviors (3).

Diabetes has a significant social impact that necessitates creative, comprehensive solutions. AI holds great promise for improving outcomes, reducing disparities, and lessening the disease's impact on society, making it a significant turning point in the treatment of diabetes. But for AI to be successfully incorporated into diabetes care, a well-rounded strategy that tackles moral, technical, and societal issues is needed. For AI-driven innovations to be fair, available, and efficient, cooperation between patients, healthcare professionals, technologists, and legislators is crucial. The healthcare industry can transform diabetes care and lessen its significant societal burden by embracing AI's potential while maintaining moral principles and putting patient-centered care first (8).

1.1 Fundamental concepts

A revolutionary approach to precision-equitable diabetes care is represented by the convergence of federated learning (FL) and multimodal artificial intelligence (AI), which tackles important issues with data privacy, interoperability, and tailored intervention (10). Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a rising global health burden that necessitates creative ways to reduce inequalities in care outcomes and access, especially for underprivileged groups (10). Traditional centralized AI models face limitations due to fragmented healthcare data and stringent privacy regulations, which hinder cross-institutional collaboration (11). Federated multimodal AI emerges as a robust framework to overcome these barriers by enabling decentralized model training across heterogeneous datasets while preserving patient confidentiality (12). FL facilitates collaborative model development without raw data exchange, aligning with privacy-preserving regulations such as HIPAA and PIPEDA (12). In diabetes care, FL has demonstrated efficacy in predicting complications and optimizing glycemic control using electronic health records from multi-province cohorts (11). Studies leveraging SecureBoost and vertical-FL have shown promise in integrating diverse clinical features across institutions sharing the same patient population but differing in feature spaces (12). This approach mitigates biases inherent in single-center datasets and enhances model generalizability (11). However, challenges persist in scenarios with label scarcity, necessitating semi-supervised FL techniques that combine labeled and unlabeled data (13). Innovations like Federated PU Learning address settings where some institutions possess only positive and unlabeled samples, while others contribute purely unlabeled data, enabling robust risk prediction even with sparse annotations (14). Multimodal AI integrates diverse data modalities—continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), insulin pump logs, activity trackers, and genomic markers—to capture the complex pathophysiology of diabetes (10, 14). Unlike unimodal models, multimodal frameworks leverage cross-modal alignment and co-learning to enhance predictive accuracy and clinical relevance (10, 15). While image-to-text translation models enhance diabetic retinopathy screening, time-series analysis of CGM data in conjunction with NLP-derived dietary logs can forecast glycemic variability (10, 14). By pretraining models on unlabeled multimodal pairs, recent developments in self-supervised learning (SSL) further reduce reliance on labeled data, enabling label-efficient fine-tuning for personalized care. Two major challenges are representation learning and fusion strategies (10, 15).

2 Main methodologies

2.1 Early screening and risk prediction

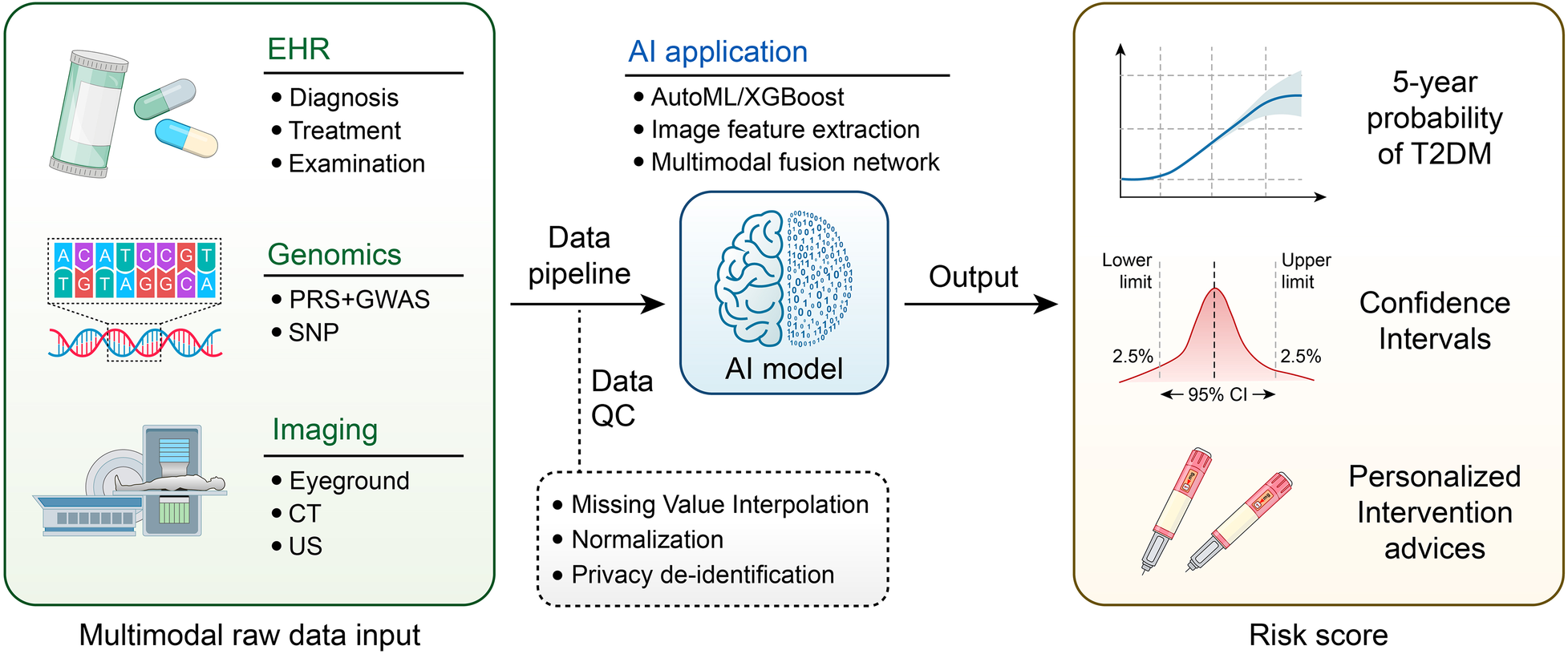

A revolutionary change in healthcare is represented by the incorporation of AI into risk prediction and early screening frameworks, especially when considering chronic illnesses and intricate clinical outcomes. Clinical decision-making has traditionally relied on traditional scoring systems, such as the Finnish Diabetes Risk Score (FINDRISC) for diabetes risk assessment. Nevertheless, these systems frequently depend on manually selected, static variables and are not flexible enough to adjust to the changing needs of patient data. By utilizing multimodal data sources, such as genetic information, wearable device data, and electronic health records (EHRs), ML-enhanced models have overcome these constraints and produced more precise and customized risk prediction tools (16, 17) (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Workflow of multimodal artificial intelligence for diabetes risk prediction.

2.1.1 Transitioning from traditional scoring systems to ML-enhanced predictive models

The Finnish Diabetes Risk Score (FINDRISC) and other traditional risk-scoring systems have long been used as fundamental instruments for diabetes stratification and prediction. These systems frequently include clinical factors chosen by univariate analysis or expert consensus, and they usually rely on traditional statistical methods that assume linear relationships between variables and outcomes (18). Although these models offer a structured framework for risk assessment, their intrinsic drawbacks, such as their incapacity to capture intricate, nonlinear interactions among predictors, frequently lead to subpar accuracy, especially in patient populations that are heterogeneous (19). Traditional scores are frequently developed on selective cohorts, limiting their generalizability to real-world clinical settings where patient demographics and comorbidities may vary significantly (20).

By addressing these issues through sophisticated computational methods, machine learning (ML) models, on the other hand, offer transformative potential. Neural networks, Random Forest (RF), gradient boosting, and other machine learning algorithms are excellent at spotting complex patterns in high-dimensional datasets, including nonlinear and interactive effects between variables (21, 22). When it comes to predicting diabetes-related outcomes, ensemble techniques like CatBoost have shown better discrimination and calibration than established scores like GRACE or conventional logistic regression (23, 24). These models maximize the informational yield from available datasets by utilizing a wider range of predictors, including clinical, behavioral, and demographic data (25, 26). Notably, ML approaches have been successfully applied to predict diabetic complications and health literacy levels, areas where traditional scores often falter due to oversimplification (27, 28). Although they are useful, traditional risk assessment tools rely on a small number of clinical and demographic variables that frequently lack the dynamic adaptability and granularity needed for personalized medicine (29). In contrast, ML-enhanced models use extensive datasets, such as imaging, clinical, demographic, and even socioeconomic factors, to find intricate patterns and relationships that conventional models might miss (30). ML algorithms like Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and K-nearest neighbors (KNN) have shown excellent performance in the context of hip fracture risk prediction, with accuracy levels ranging from 70.26% to 90% and Area Under the Receiver Operating Curve (AUC) values between 0.39 and 0.96 (31). The predictive power of these models is greatly increased by incorporating a variety of variables, such as geometric factors from imaging data and finite element analysis (32).

Beyond traditional risk factors, AI is being used in early screening to identify subtle biomarkers and imaging features that are difficult to detect using traditional techniques. ML models have been created to evaluate multi-target panels from blood tests in colorectal cancer (CRC) screening, with AUC values of up to 0.941 for CRC detection and 0.925 for the classification of colorectal adenoma (CRA) (33).

These models provide a non-invasive, affordable, and scalable approach to early detection, outperforming conventional biomarkers such as CEA and CA199 (34). With an AUC of 0.87 for identifying high-risk prostate cancer (PCa), ML models based on MRI radiomic features have also demonstrated encouraging results in PCa risk stratification, supporting individualized treatment planning. These developments demonstrate how AI can be used to enhance conventional scoring models by increasing their predictive accuracy and integrating a wider variety of data sources.

The capacity of ML-enhanced models to incorporate multimodal data—such as imaging, clinical, and behavioral factors—to produce a thorough risk assessment is one of their main innovations. ML algorithms like Random Forest (RF) and Adaptive Boost Machine (ABM) have been used to predict 90-day functional impairment in stroke risk prediction, with AUC values that are comparable to those of conventional logistic regression models (35). These models provide a more comprehensive evaluation of patient risk by utilizing a wide range of predictors, such as imaging data, clinical history, and lifestyle factors (36). By combining several algorithms to reduce overfitting and increase generalizability, stacking-integrated machine learning (SIML) techniques have further improved these models’ predictive performance (37). With an AUC of 0.877, sensitivity of 81.8%, and specificity of 81.9% in cervical cancer screening, SIML models have greatly outperformed conventional risk assessment instruments (38).

The use of AI in risk assessment and early screening also includes resource allocation and screening interval optimization. AI models like Mirai have been used in breast cancer screening to classify patients into risk groups according to their mammogram data. This allows for customized screening intervals, which lowers the incidence of advanced cancers by about 18 cases per 1,000 screened people (39). By concentrating on high-risk individuals, this strategy not only increases the effectiveness of screening programs but also lessens the strain on healthcare resources (40). Analyzing data from the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), ML models have been developed to predict fall risk. These models have achieved AUC values of 0.78 and offer a scalable solution for identifying older adults who are at high risk of falling (41). These models offer a more precise evaluation of fall risk by combining a variety of predictors, such as handgrip strength, body mass index (BMI), and fall history (42).

Several drawbacks of conventional scoring models, such as their dependence on a small number of predictors and their incapacity to capture intricate relationships between variables, are also addressed by the incorporation of AI and ML in early screening and risk prediction. Conventional stroke risk scores frequently depend on a limited number of clinical predictors, which might not adequately account for the variety of stroke risk factors (43). However, to provide a more thorough evaluation of stroke risk, machine learning models can integrate a variety of predictors, such as imaging data, clinical history, and behavioral factors (44). By continuously adding new data, machine learning models can adjust to shifting risk profiles and gradually increase their predictive accuracy (45).

2.1.2 Multimodal data integration

An innovative strategy for addressing this worldwide health issue is the incorporation of AI into diabetes risk assessment and early screening. AI models can greatly improve the precision and effectiveness of diabetes detection and risk stratification by utilizing multimodal data, such as genetic information, wearable device outputs, and EHRs. The shortcomings of conventional diagnostic techniques, which frequently rely on a single data source and might overlook early signs of disease progression, are addressed by this multimodal approach. AI systems that have been trained on extensive datasets have shown impressive predictive powers. They were able to identify high-risk subgroups for Type 2 Diabetes with an AUC of 0.94 (46). This high accuracy highlights AI's potential to support early detection and preventive measures, which are essential for reducing the serious consequences of diabetes, such as retinopathy, nephropathy, and cardiovascular disease (46).

With its increased risk of T2DM, cardiovascular disease, and poor perinatal outcomes, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), a condition marked by glucose intolerance initially identified during pregnancy, poses serious risks to both mother and child (38, 47). Traditional screening techniques, like the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), are frequently laborious, time-consuming, and have a limited capacity to predict risk prior to the second trimester, despite the importance of early detection and intervention (43, 47). By combining various data sources, such as clinical, demographic, and multi-omics data, AI-driven models that use ML algorithms present a promising way to accurately and efficiently predict the risk of GDM (41, 48).

While multi-omics techniques offer a thorough understanding of the molecular alterations linked to GDM, ultrasound imaging provides real-time information on fetal and placental development, both of which are essential for early risk assessment (38, 49). The potential of imaging biomarkers in early diagnosis has been highlighted by studies showing that AI models that incorporate placental texture features from ultrasound images can successfully differentiate between pregnant women in good health and those with GDM (38, 49). It has been demonstrated that combining multi-omics data with clinical variables, such as plasma adiponectin levels and other metabolic markers, improves predictive accuracy (47, 50). In addition to improving the accuracy of GDM prediction, these integrated approaches give physicians practical advice for early intervention, such as pharmacological treatments or lifestyle changes, to reduce negative consequences (41, 47).

AI models are especially useful in settings with limited resources because they have shown a remarkable degree of versatility in using readily available clinical variables to predict GDM risk. Traditional risk stratification techniques have been outperformed by non-invasive models that use maternal age, mean arterial blood pressure, prior history of GDM, and ethnicity. These models have demonstrated high predictive performance (AUC: 0.82) (41, 50). These models remove the need for intricate laboratory testing, making them widely applicable in low- and middle-income nations with limited access to cutting-edge diagnostic equipment (41, 43). AI-driven models are useful in a variety of healthcare settings because they have been tuned to achieve high sensitivity and specificity with few input variables (41, 48). A study created 12 distinct machine learning models, four of which, with just 7–12 variables, had a sensitivity of 0.82 and a specificity of 0.72–0.74, indicating the possibility of scalable and effective GDM screening (48).

Beyond risk assessment, the creative application of AI in GDM prediction incorporates long-term health monitoring and tailored interventions. With the use of AI models, patients can be categorized according to their risk profiles, allowing for more focused interventions like medication, exercise regimens, and dietary changes (41). AI has also been used to forecast when GDM will progress to postpartum type 2 diabetes, providing a customized risk score that can direct long-term medical interventions (51). Prenatal fasting glucose levels, gestational age at diagnosis, and insulin therapy during pregnancy have all been found by machine learning algorithms to be significant predictors of postpartum dysglycemia, laying the groundwork for individualized postpartum care (51). These developments demonstrate AI's potential to lessen the long-term burden of diabetes and its associated complications in addition to improving immediate pregnancy outcomes.

Utilizing cutting-edge machine learning methods, like eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), to combine various data types is another significant development in this field. When paired with demographic factors, Polygenic Risk Scores (PRS) from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and Multi-image Risk Scores (MRS) from medical imaging data offer a comprehensive picture of a person's risk for diabetes (46). This integration allows for the identification of subtle patterns and correlations that traditional methods might overlook. The predictive ability of AI models 2 has been further improved by the use of medical imaging methods like electrocardiography (ECG) and abdominal ultrasonography to identify T2D-associated diseases like cardiovascular disease and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (46). CGM outputs and other wearable device data provide real-time insights into metabolic health, facilitating dynamic risk assessment and individualized intervention strategies (52).

The diversity of diabetes risk factors among various populations is also addressed by the use of AI in diabetes screening. Due to variations in lifestyle, genetics, and environmental factors, traditional risk assessment instruments created for Western populations frequently perform poorly when used with Asian or other ethnic groups (53). However, by training on local datasets, AI models can be customized to target particular populations, increasing their clinical utility and predictive accuracy. When applied to Chinese populations, for example, ensemble machine learning techniques have been demonstrated to perform better than current non-invasive risk score systems, underscoring the significance of developing population-specific models (53). AI is a useful tool for global diabetes prevention initiatives because of its adaptability, especially in areas with inadequate healthcare resources.

AI-driven diabetes screening has the potential to improve patient engagement and adherence to preventive measures, which is another important benefit. Online platforms and other AI-based risk assessment tools offer easily navigable interfaces that enable people to evaluate their risk of diabetes and obtain tailored recommendations (46). With the help of these resources, patients can take the initiative to change their lifestyles, which are essential for preventing diabetes and include better eating and more exercise (52). AI models can help medical professionals spot high-risk patients early, allowing for prompt interventions and lessening the strain on healthcare systems. Clinicians can better monitor patient progress and customize treatment plans by using predictive models that forecast changes in HbA1c levels based on EHR data (52).

These models' clinical applicability is further improved by the application of explainable AI (XAI) techniques, which offer insights into the variables influencing risk predictions. Chest radiographs (CXRs) may be used for improved T2D screening, for example, as XAI has shown correlations between certain adiposity measures and high predictivity (54). In addition to fostering confidence in AI-driven diagnostics, this openness makes it easier to incorporate AI suggestions into clinical procedures. Further demonstrating AI models' scalability and potential for broad use is their capacity to handle massive amounts of data, including more than 270,000 CXRs and 160,000 patient records (54).

Recent advancements show how multi-modal data fusion, which integrates lifestyle, genomic, clinical, and imaging data, can increase prediction accuracy. Nevertheless, there are still challenges in aligning different features while lowering noise and positional shifts (55, 56). By using adaptive region-feature alignment and RoI jittering to address the positional misalignment between modalities, Aligned Area CNN (AR-CNN) increases robustness in object detection tasks (56). Similarly, Frequency-Aware Feature Fusion (FreqFusion) addresses intra-category inconsistency in dense predictions by harmonizing spatial and boundary features using adaptive low- and high-pass filters. This method can be used for imaging analysis associated with diabetes (57). These techniques emphasize the importance of dynamic feature calibration, where spatial and temporal dependencies are modeled to refine feature relevance, as demonstrated by video-based 3D detection systems that propagate scene features across frames (58).

The gap between algorithmic accuracy and clinical interpretability can be reduced by combining statistical models with explainable AI (XAI) frameworks. By tailoring feature selection to specific patient profiles, SHAP value analysis in the iCARE system maximizes diagnostic accuracy for early-stage diabetes prediction by measuring feature contributions (59). Trust-weighted fusion of multi-block features can withstand noise thanks to evidential deep learning (EMFF) and other complementary techniques that quantify uncertainty in adversarial environments. This is an essential capability for diabetes risk stratification using high-dimensional gene expression data (60). Hybrid optimization algorithms demonstrate how statistical optimization and artificial intelligence collaborate to reduce dimensionality by continuously enhancing gene signatures to attain higher classification accuracy (61).

However, for equitable implementation, disparities in data quality between populations must be addressed. The absence of standardized electronic health records (EHRs) in rural and underserved areas exacerbates biases in AI models trained on urban datasets. Large-scale, low-cost retinal imaging is used by solutions like cross-modal self-supervised learning to democratize access, while federated learning frameworks safeguard privacy by decentralizing model training (24, 62). A critical strategy for scalable diabetes screening in resource-constrained settings, ensemble approaches reduce overfitting in unbalanced datasets and achieve 93% accuracy with smaller feature sets (63).

Future directions should prioritize interdisciplinary collaboration to validate fusion techniques across multiple cohorts and standardize multimodal datasets. While integrating AlphaFold-predicted protein structures with EHRs (as in PredGO) may uncover new biomarkers for diabetic nephropathy, real-time edge computing may enable low-latency, contrast-adaptive monitoring of glycemic fluctuations (64, 65). Precision-equitable diabetes care can overcome present constraints by balancing AI's scalability with statistical rigor, providing tailored interventions that are both clinically actionable and widely available.

Explainable AI (XAI) is increasingly recognized as a paradigm-shifting approach in healthcare, particularly for precision-equitable diabetes care. XAI bridges the gap between complex AI-driven predictions and useful clinical insights. By incorporating multimodal data, such as wearable sensor outputs, imaging, and electronic health records (EHRs), XAI enhances the interpretability of federated learning models, which are crucial for collaborative yet privacy-preserving diabetes management across diverse populations (66). Federated learning enables multiple institutions to train a single AI model on various datasets without sharing raw data, addressing disparities in data availability and labeling methods (67). However, clinician trust is often diminished by these models' “black-box” nature. By employing techniques like SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) and Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME), which elucidate feature importance and decision pathways in glycemic control predictions or diabetic retinopathy screening, XAI tackles this problem (68, 69).

XAI is novel due to its dual capacity to strike a balance between cutting-edge AI and conventional statistical methods like logistic regression or decision trees, which are still essential for risk stratification in diabetes care due to their intrinsic transparency (70). While CNNs and other deep learning models outperform these methods in terms of accuracy, particularly for tasks like retinal image analysis, their opacity makes clinical adoption more challenging (71). XAI addresses this by reducing complicated neural network outputs into human-friendly rules or visualizations. Examples of these include counterfactual explanations that demonstrate how shifting HbA1c levels impact risk predictions or saliency maps that draw attention to microaneurysms in fundus images (72, 73). This synergy is crucial for precision equity because it reduces biases in marginalized populations and ensures that AI tools are both high-performing and accessible to clinicians with varying degrees of technical expertise (71, 74).

One major technological advantage in the treatment of diabetes is XAI's ability to integrate multimodal data fusion techniques, such as REMEDIS, which enhances model robustness by combining representations from multiple data sources. By integrating retinal scans with EHR-derived comorbidities, XAI can demonstrate how diabetic neuropathy detection is enhanced, providing clinicians with a thorough grasp of patient risk (68). XAI's role in federated learning ensures equitable model performance across organizations with diverse data demographics—a critical component of diabetes management globally (67, 74). XAI also makes it easier to comply with legal frameworks like GDPR, which require transparency in automated decision-making, by offering detailed explanations (69, 71).

When clinicians comprehend the model's reasoning, they move from skepticism to trust, which is one of the long-standing problems in diabetes care that XAI can help with (75). Generative counterfactual XAI frameworks can simulate how minor alterations in ECG morphology, a stand-in for diabetic autonomic neuropathy, impact AI predictions in order to conform to clinicians' causal reasoning (73). Similarly, Clinical decision support systems (CDSS) driven by XAI can compare evidence in favor of and against insulin titration, encouraging team decision-making and reducing therapeutic inertia (76, 77). New tools like HistoMapr-Breast demonstrate how XAI can enhance diabetes workflows by pre-identifying diagnostic regions in pathology slides or continuous glucose monitoring trends, despite the fact that they were developed for oncology (68).

XAI is a significant development for precision-equitable diabetes care by demystifying AI outputs, validating federated models across multiple cohorts, and emphasizing the complementary roles of AI and conventional statistics. Future studies should concentrate on improving multimodal data fusion for low-resource settings, standardizing XAI evaluation metrics in clinical settings, and expanding real-world validation of frameworks like LIME-SHAP hybrid models (69, 71). XAI can accelerate the shift from reactive diabetes management to proactive, customized interventions while maintaining equity and trust by placing equal emphasis on interpretability and performance.

Missing values, temporal misalignments, and inconsistent data formats are common problems with multimodal datasets. While digital health records might not include clinical biomarkers, EHRs might not have detailed lifestyle data (78, 79). Robust machine learning models cannot be trained with sparse datasets, so sophisticated imputation methods and FL frameworks are required to reduce bias (80). Scalability is limited by the substantial computational resources required to process high-dimensional data (81, 82). Additionally, privacy concerns arise when integrating sensitive health information across platforms, requiring stringent anonymization protocols (83). Although AI models are very good at identifying patterns, clinical translation is made more difficult by their “black-box” nature. As demonstrated by studies where ML-derived phenotypes were not easily actionable without additional validation, doctors may mistrust predictions that lack mechanistic explanations (79, 84). Efforts to enhance model interpretability—such as attention mechanisms in transformer architectures—are critical for fostering trust (85). External validity is called into question because the majority of multimodal studies concentrate on homogeneous cohorts. In rural areas with different comorbidities and access to healthcare, algorithms trained on urban populations may perform worse (86, 87). Cross-institutional collaborations and diverse dataset curation are essential to address this limitation. Further demonstrating AI models' scalability and potential for broad use is their capacity to handle massive amounts of data, including more than 270,000 CXRs and 160,000 patient records (54).

2.2 Complication surveillance & intervention

With previously unheard-of levels of precision, efficiency, and scalability, the application of AI to the monitoring and treatment of diabetes complications represents a revolutionary approach to managing these chronic conditions. Three crucial areas—diabetic retinopathy, diabetic nephropathy, and diabetic foot complications—are especially affected by AI-driven technologies, which use sophisticated computational techniques to improve early detection, prediction, and intervention techniques.

2.2.1 Diabetic retinopathy

A revolutionary development in medical technology is the application of AI to the monitoring and treatment of diabetic complications, especially DR. Early detection and intervention are essential to preventing irreversible vision loss because DR, a major cause of blindness in the working-age population, is frequently asymptomatic (88, 89). In addition to being time-consuming and resource-intensive, traditional diagnostic techniques that depend on ophthalmologists manually analyzing retinal images also have poor patient adherence rates—less than 50% of diabetics follow recommended yearly eye exams (90, 91). However, AI-driven systems provide a scalable, effective, and precise substitute that can address the rising global burden of DR by introducing specialty-level diagnostics into primary care settings (92, 93).

The creation of autonomous AI diagnostic systems, which have shown impressive diagnostic accuracy, is among the most important developments in this field. An AI system for DR detection, for example, exceeded pre-specified superiority endpoints in a pivotal trial with a sensitivity of 87.2% and specificity of 90.7% (94). This FDA-approved system represents a significant advancement in the use of AI in medicine as it is the first of its kind to be implemented in clinical practice (95). The AI system guarantees accurate disease-level output across a range of patient demographics, including differences in age, race, and ethnicity, by delivering real-time clinical decisions at the point of care along with immediate image quality feedback (96, 97). In environments with limited resources, where access to specialized healthcare is frequently restricted, such capabilities are especially important (98).

Novel machine learning architectures, such the Hierarchical Block Attention (HBA) and HBA-U-Net models, have improved AI-driven systems by honing picture segmentation by concentrating on pixel-level details and spatial correlations (99). These models have demonstrated diagnostic accuracies surpassing 99% in identifying vision-threatening DR (VTDR) when paired with hybrid Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Support Vector Machines (SVMs) (100). The diagnosis of diabetic macular edema (DME), a serious consequence of DR, is made possible by the combination of fundus imaging with optical coherence tomography (OCT), which further improves diagnostic accuracy (101, 102). These developments highlight AI's capacity to identify DR and track its development, enabling prompt interventions that can greatly enhance patient outcomes (103).

Real-world clinical settings have also validated the use of AI in DR screening. A study with a 92% specificity in Western Australian primary care practices showed that using AI systems for DR detection was feasible (104). To improve diagnostic reliability and decrease false positives, AI algorithms must be further refined. However, issues like low disease incidence rates and poor image quality were noted (105). Notwithstanding these obstacles, AI-driven systems' affordability and scalability make them a viable way to close the global DR screening gap, especially in areas with little access to ophthalmologists (106).

Along with its diagnostic potential, AI has demonstrated promise in tracking the progression of DR by analyzing microaneurysm (MA) turnover, a possible biomarker for DR risk. With high sensitivity and specificity, automated tools have been developed to locate MAs, align retinal images from multiple patient encounters, and estimate MA turnover rates (107). Clinicians can optimize patient care by using this capability to evaluate disease activity and customize treatment plans based on real-time data. By enabling patients to have retinal imaging in primary care settings and receive evaluations remotely, AI-driven systems can support telemedicine-based DR screening, removing logistical obstacles and enhancing screening protocol adherence.

It is impossible to overestimate the economic and societal effects of AI-driven DR monitoring and intervention. In addition to being a major cause of blindness, DR places a heavy financial strain on healthcare systems around the globe. For millions of people with diabetes, early detection and treatment of DR can improve their quality of life, lower healthcare costs, and prevent vision loss. AI-driven systems have the potential to completely transform DR management because they can provide high-efficiency, high-accuracy diagnostics at a reduced cost, especially in low- and middle-income nations where the prevalence of diabetes is disproportionately high.

2.2.2 Diabetic nephropathy

A revolutionary development in the treatment of chronic diseases is the incorporation of AI into the monitoring and treatment of diabetic complications, especially diabetic nephropathy (DN). One of the main causes of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and a serious complication of T2DM, DN is linked to a high rate of morbidity and mortality (108). The intricate relationship between hyperglycemia, hypertension, and dyslipidemia in DN management calls for a multimodal strategy that AI is uniquely suited to provide (109). A I-driven models that use ML and deep learning (DL) techniques have shown great promise in anticipating the course of a disease, improving treatment plans, and facilitating early intervention to reduce complications (110). The ability of AI to forecast disease progression using time-series data and electronic medical records (EMRs) is one of the most promising uses of AI in DN. Recent research has demonstrated that by examining historical data and spotting minute patterns suggestive of early renal decline, AI models can forecast the onset of DN even before clinical symptoms like microalbuminuria manifest (111). When identifying high-risk patients who might benefit from intensive interventions, like statins and antihypertensive drugs, to postpone or stop the progression to ESRD, this predictive capability is especially helpful (112). By examining biomarkers like serum creatinine levels and the urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio, AI models have been created to forecast the risk of cardiovascular events, which are strongly associated with DN (113). By averting expensive complications and hospital stays, these models not only improve clinical judgment but also lessen the financial burden related to DN (114). The integration of multimodal AI approaches to concurrently model renal, cardiovascular, and metabolic risks represents a transformative paradigm in precision medicine, addressing the interconnected pathophysiology of these conditions (115, 116).

In order to optimize individualized treatment plans for patients with DN, AI is also essential. Through the integration of data from various sources, such as electronic medical records, laboratory results, and patient-reported outcomes, artificial intelligence algorithms are able to determine the most effective treatment plans customized for each patient's unique profile (117). Based on real-time glucose monitoring and predictive analytics, AI-driven decision support systems can suggest changes to dietary regimens, medication dosages, and lifestyle choices (118). AI-powered mobile health (mHealth) apps further improve this individualized approach by giving patients ongoing feedback on their blood sugar levels, medication compliance, and physical activity, enabling them to actively manage their condition (119).

The early detection and monitoring of DN has also been transformed by the use of AI in imaging and diagnostic technologies. AI algorithms have been added to advanced imaging methods, such as femoral intima-media thickness (IMT) measurements and lower extremity arterial ultrasound, to evaluate the burden of peripheral atherosclerosis and forecast the risk of cardiovascular events (38). By giving doctors a more thorough picture of the patient's overall vascular health, these AI-enhanced imaging tools allow for earlier and more focused interventions (39). In order to increase the precision of DN diagnosis and staging and enable more accurate treatment planning, artificial intelligence has also been used in the analysis of renal biopsies and other histopathological data (41). Fundus photography and optical coherence tomography (OCT), which call for specific tools and skilled workers, are the main methods used by AI algorithms for DR detection (97, 120). Studies reveal that portable smartphone-based cameras achieve lower sensitivity compared to tabletop systems, particularly in low-resource settings where image quality is compromised by inadequate lighting or operator skill (121). Additionally, 28.2% of images in real-world screenings had artifacts that prevented AI from grading them, highlighting the necessity of strong preprocessing and quality control procedures (122).

While AI models like the Hierarchical Block Attention U-Net (HBA-U-Net) achieve 99.18% accuracy in controlled datasets, their performance diminishes in multiethnic cohorts or underrepresented populations (123, 124). AI systems trained on homogeneous datasets exhibit higher false-negative rates for darker retinal pigmentation or atypical lesion patterns, exacerbating health disparities (125, 126). The lack of standardized evaluation frameworks further complicates cross-study comparisons and clinical adoption (127).

The use of multimodal AI techniques to simultaneously model renal, cardiovascular, and metabolic risks is a groundbreaking paradigm in precision medicine that tackles the interconnected pathophysiology of these disorders (115, 116). Metabolic disorders such as type 2 diabetes (T2D), cardiovascular diseases (CVD), and chronic kidney disease (CKD) often coexist because they share risk factors such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, and systemic inflammation (128, 129). Traditional unimodal predictive models, which analyze clinical, imaging, or biomarker data independently, have limited prognostic accuracy and clinical utility due to their inability to capture the synergistic interactions between these systems (130, 131). The Kidney Failure Risk Equation (KFRE) ignores cardiovascular comorbidities that exacerbate the course of chronic kidney disease (CKD), despite using biochemical factors to predict renal outcomes (55). CVD risk stratification tools often ignore renal dysfunction, a critical component of cardiovascular mortality (128, 129). Multimodal AI frameworks overcome these limitations by integrating multiple data modalities, including wearable-derived metrics, omics (proteomics, metabolomics), imaging (retinal fundus photography, coronary CT angiography), and electronic health records (EMR), to generate comprehensive risk profiles (130, 132).

Because it can carry out cross-modal representation learning and dynamic feature fusion, multimodal AI is technologically innovative and can uncover latent biological patterns that single-modality models miss. Deep learning architectures like ResNeSt and Transformer-based models have demonstrated remarkable performance when integrating renal ultrasound images, spectral waveforms, and clinical data to diagnose renal artery stenosis (RAS), with accuracies exceeding 80% (133). By detecting microvascular changes indicative of systemic endothelial dysfunction, the combination of non-invasive clinical risk factors and retinal fundus photography improved the prediction of CVD (132). These developments improve feature representativeness even with small multimodal datasets by utilizing semi-supervised autoencoders and transfer learning strategies (134). Notably, multimodal models also address data imbalance problems, which are common in metabolic and renal cohorts, by employing ensemble learning and synthetic minority oversampling (SMOTE) to improve minority-class prediction (134, 135).

The clinical imperative for multimodal AI is highlighted by the need for early risk stratification and customized interventions. T2D patients with concurrent CKD and CVD exhibit distinct proteomic and metabolomic signatures that more accurately predict adverse outcomes than HbA1c alone (134, 136). Multimodal frameworks like MAIGGT, which combine clinical phenotypes and histopathological features, have achieved AUROCs of 0.92 for BRCA1/2 mutation screening, revealing microenvironmental markers linked to metabolic dysregulation (137). These models enable targeted therapies, such as SGLT2 inhibitors, which concurrently lower metabolic, cardiovascular, and renal risks (129, 136). Interpretability tools like SHAP values make modality-specific contributions clear, encouraging collaborative decision-making and fostering clinician trust (132, 137).

The results for patients with DN have been further enhanced by the incorporation of AI into multidisciplinary care models. AI-driven technologies can be used by multidisciplinary teams that include endocrinologists, nephrologists, dietitians, and diabetes educators to expedite care coordination and guarantee that patients receive prompt and efficient interventions (44). In order to lower the risk of complications and increase adherence to care protocols, I-powered platforms can automate follow-up appointment scheduling, monitor patient progress, and notify clinicians of deviations from treatment goals (43). Moreover, it has been demonstrated that AI-enabled patient empowerment devices, like blood pressure monitors, glucometers, and smart tablets, improve glycemic control and self-management practices in high-risk patients (126).

2.2.3 Diabetic foot

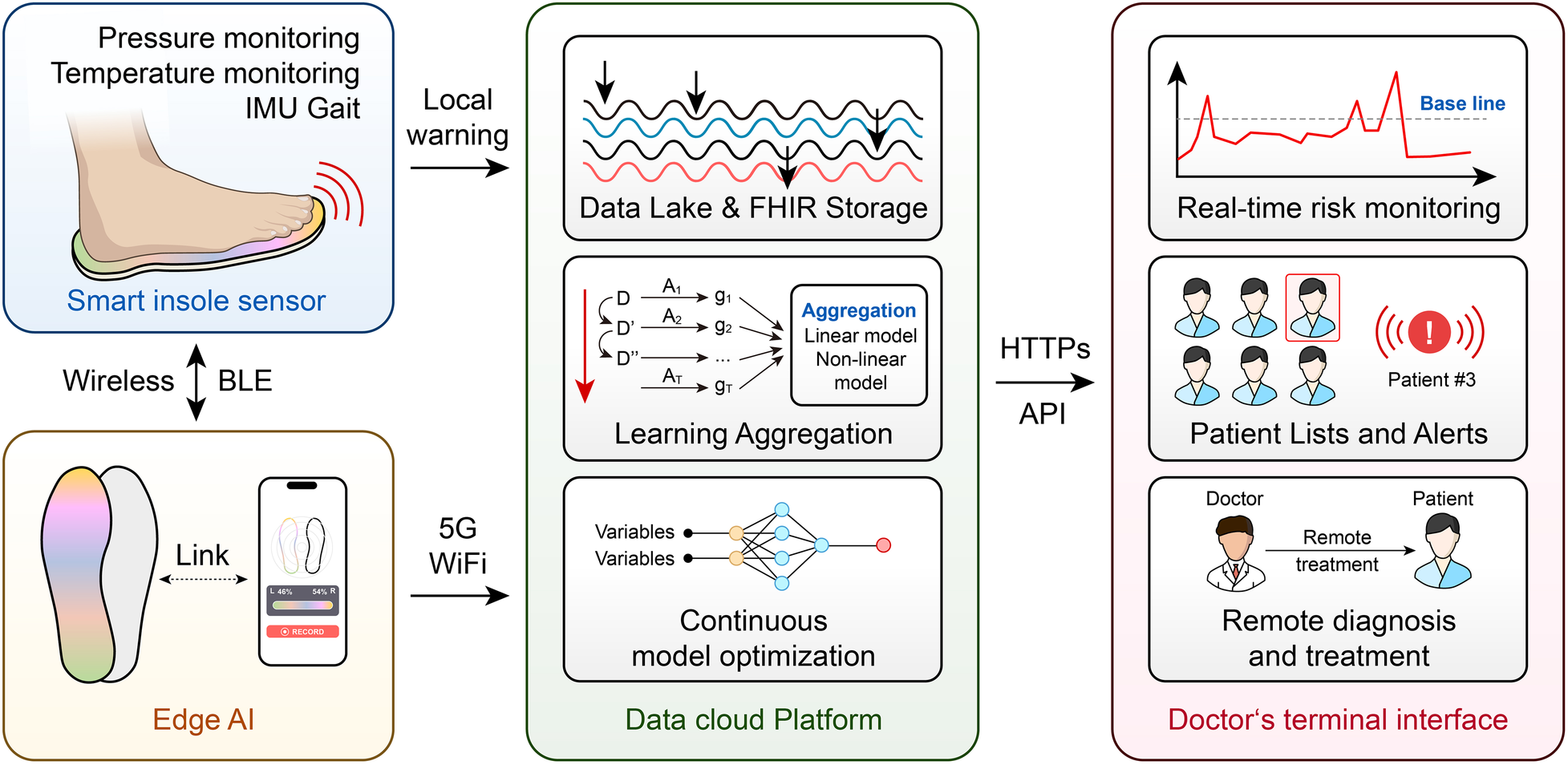

The creation of sensor-based remote patient monitoring (RPM) systems is one of the most exciting uses of AI in diabetic foot care. These systems use multimodal sensing technologies, like smart insoles, to continuously monitor temperature, activity levels, and plantar pressure (138, 139). These gadgets can offer patient-facing biofeedback by incorporating AI algorithms, warning users of persistently elevated plantar pressures or temperature imbalances that might be signs of pre-ulcerative conditions. In addition to empowering patients to actively offload, this proactive approach allows medical professionals to take early action, lowering the risk of ulceration and its aftereffects (140, 141). RPM systems support glycemic control, cardiovascular health, and general disease management by being in line with integrative foot care guidelines (142).

AI-driven image recognition technologies are transforming the evaluation and categorization of diabetic foot wounds in addition to sensor-based monitoring. Conventional wound assessment techniques, like the PEDIS index, mainly depend on clinicians' qualitative evaluations, which can be erratic and subjective (143). AI-powered technologies can identify, locate, and measure ulcers with high accuracy (up to 90%) by analyzing wound images using CNNs and deep learning algorithms (144). In addition to improving diagnostic accuracy, these systems help multidisciplinary care teams communicate with one another, which makes treatment planning and resource allocation more efficient. Patients can self-monitor their DFUs at home with AI-based wound monitoring tools, like the smartphone app “MyFootCare,” which offers insightful data on the course of healing and the effects of self-care routines (138). Despite the potential of these tools, issues like usability, data privacy, and the requirement for more extensive validation studies still exist (38).

The creation of customized therapeutic exercise regimens is another cutting-edge use of AI in diabetic foot care. In people with DPN, foot-ankle exercises have been demonstrated to increase muscle strength, range of motion, and gait biomechanics, lowering the risk of ulcers and improving functional outcomes (39, 41). AI-powered platforms, like the Sistema de Orientação ao Pé Diabético (SOPeD), provide personalized workout plans based on each person's physical capabilities and the severity of their condition. These programs, which can be accessed through mobile or web applications, use gamification techniques and real-time feedback to encourage self-management and adherence (43). The potential of these interventions as supplemental treatments in primary and secondary care settings has been highlighted by studies showing that they can result in notable improvements in foot pain, function, and kinematic outcomes (44).

AI is also being incorporated into decision support and predictive analytics for diabetic foot care. AI models can predict healing trajectories, optimize treatment protocols, and identify risk factors for DFU development by analyzing large datasets (145). In order to categorize people according to their risk of complications and suggest focused interventions, machine learning algorithms can evaluate patient data, including demographic, clinical, and imaging information (146). In addition to improving clinical decision-making, these predictive tools facilitate the application of evidence-based recommendations, like those offered by the International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF) (147). However, issues with data quality, algorithm transparency, and ethical considerations must be resolved for these systems to be deployed successfully (148) (Figure 3).

Figure 3

AI-driven closed-loop diabetic foot monitoring.

2.3 Real-Time monitoring & decision support

2.3.1 CGM time-series forecasting

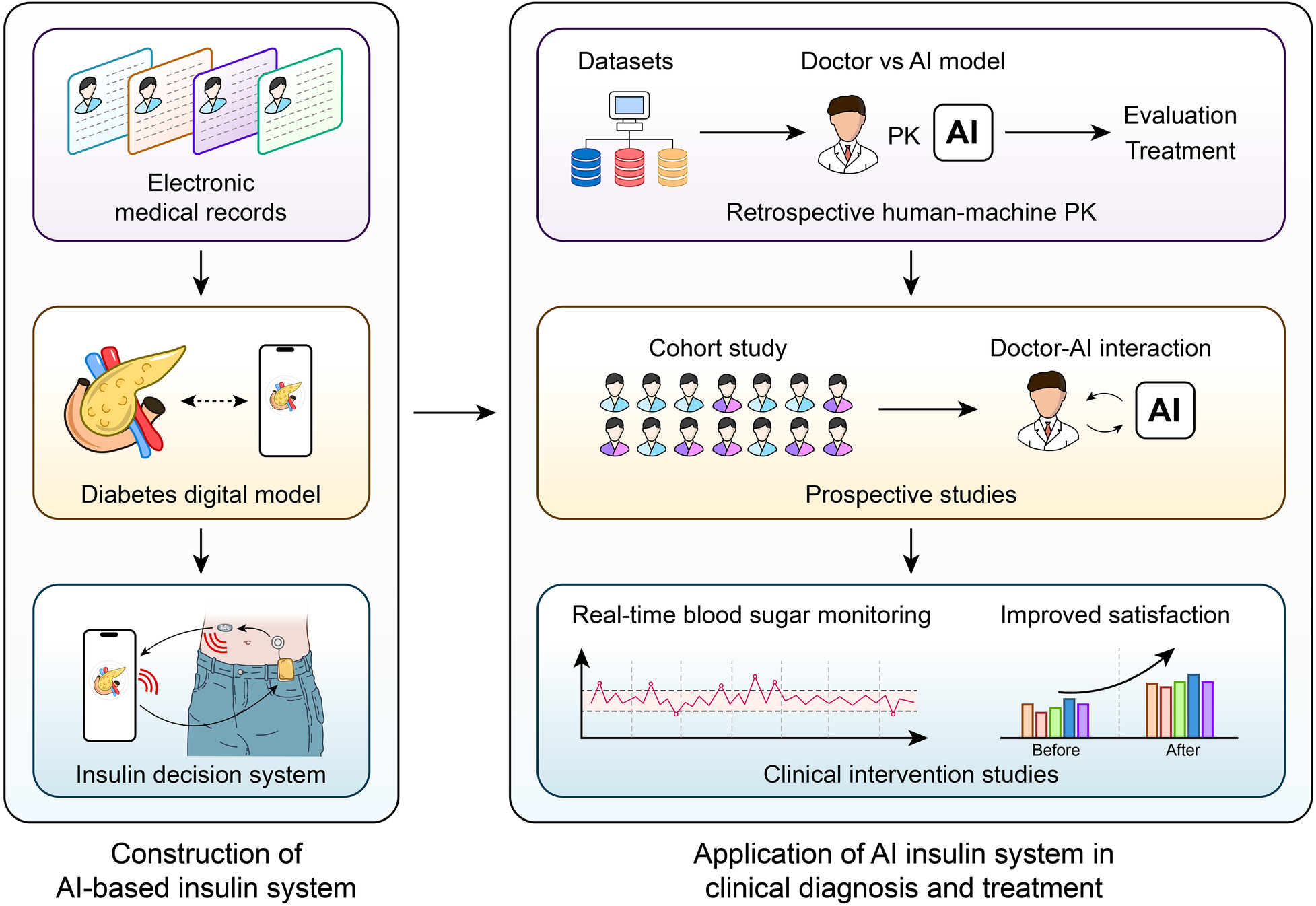

A revolutionary method of managing diabetes, especially in the area of time-series glucose prediction, is the combination of AI with wearable technology and CGM devices. In order to optimize insulin dosage and avoid adverse glycemic events, real-time, personalized glucose forecasting is made possible by the combination of AI and CGM data. Because of their exceptional ability to handle sequential data, Transformer architectures and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks have attracted a lot of attention among the different AI models used for this purpose. LSTM networks—a specialized type of Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs)—have shown impressive effectiveness in glucose prediction tasks. With a root mean square error (RMSE) reduction from 14.55 to 10.23 mg/dL when compared to standard stacked LSTM approaches in T1D cohorts, research has shown that LSTM models are more successful than traditional machine learning algorithms and even human specialists at predicting blood glucose levels over short time horizons (Shen and Kleinberg, 2025). However, the quality of the data greatly affects this benefit: In real-world use cases where signal integrity is compromised, false hypoglycemia/hyperglycemia alert rates can double due to CGM sensor noise increasing LSTM prediction error by up to 50%. Furthermore, cross-population validation reveals that when applied to older T2D patients with comorbid renal impairment, the majority of LSTM studies rely on data from young adults with T1D. This is explained by their ability to simulate the dynamic and non-linear character of glucose-insulin interactions, which are impacted by elements like insulin administration, food consumption, and physical activity (149). LSTM networks are appropriate for real-world applications where sensor errors and delays are common because they have been demonstrated to be resilient to noise in CGM data (150). A study introduces RL-DITR, a model-based reinforcement-learning framework that optimizes customized insulin dosage for in-patients with type 2 diabetes while also learning patient glucose dynamics (151) (Figure 4). Extensive validation across retrospective, prospective and proof-of-concept trials showed superior accuracy and safety compared with junior/intermediate physicians and near-parity with senior specialists. Seamless integration into the clinical workflow yielded rapid, safe glycemic improvement without increasing hypoglycemia, establishing RL-DITR as a practical, scalable AI decision-support tool for inpatient diabetes care (151).

Figure 4

AI-Driven Insulin Titration for T2DM.

Conversely, time-series prediction tasks, such as glucose forecasting, are increasingly being investigated using Transformer models, which have transformed natural language processing. Transformers can process long-range dependencies more efficiently than LSTMs because they use self-attention mechanisms to capture relationships between various time steps in the sequence. In glucose prediction, this feature enables better capture of long-cycle patterns, as demonstrated by the CGMformer models (152). In a mixed T1D/T2D cohort (n = 427), the LSTM model by Shao et al. was specifically validated for 30-min hypoglycemia prediction with >94% AUC across Chinese and European-American populations, highlighting complementary strengths in short-term accuracy vs. long-range dependency modeling (152). However, Transformers have some significant practical drawbacks in wearable applications: their self-attention mechanism raises dynamic energy by at least the same factor while increasing computational complexity quadratically with sequence length (153). Transformers have demonstrated potential in other fields, but their use in glucose prediction is still in its infancy, and there aren't many studies comparing them to LSTM models. However, early research indicates that Transformers might perform better in situations where complex, multi-scale temporal patterns need to be modeled (154). Transformers may be able to more easily incorporate extra contextual data than LSTMs, such as meal schedules and physical activity, improving prediction accuracy (154).

A number of issues with conventional glucose monitoring techniques are also resolved by integrating AI with CGM systems. The delay between actual plasma glucose levels and interstitial glucose measurements is one of the main problems, which can cause inaccurate real-time predictions. Rate-of-change metrics, variability indices, and other time-based features obtained from CGM data can be incorporated into AI models, especially those using sophisticated feature engineering techniques, to help alleviate this problem (155). Even without additional physiological metrics, these features allow for more precise and timely predictions by capturing the dynamism of glucose fluctuations (155). An important development in this area has been the creation of customized prediction models that are adapted to the glucose dynamics of specific patients. AI models can take into consideration distinct physiological reactions by utilizing patient-specific data, which increases prediction accuracy and dependability (156).

The models' computational efficiency is a crucial component of integrating AI with CGM systems, especially when used on wearable technology. Despite their effectiveness, LSTM networks can be computationally demanding, which presents problems for real-time applications on devices with limited resources. In order to address this problem, efforts to optimize these models—such as by using model compression techniques or lowering the number of parameters—have shown promise (156). Transformers are feasible for wearable applications because they have been modified for edge devices using methods like quantization and pruning, despite their computational complexity (154). One important step toward the development of closed-loop insulin delivery systems, sometimes known as the “artificial pancreas,” is the capability of wearable technology to make precise glucose predictions (119).

Beyond predicting blood sugar levels, AI is also used in CGM systems to detect hypoglycemic and hyperglycemic episodes, which are vital for avoiding serious complications in the treatment of diabetes. Research has shown that AI models, especially deep learning-based models, can accurately classify blood glucose levels into hypo-, normo-, and hyperglycemic ranges (155). While LSTM models perform well over longer prediction horizons, like 1 h, logistic regression models have demonstrated exceptional performance in predicting hypoglycemia within a 15-min horizon (155). These features are crucial for giving patients and medical professionals timely alerts so that proactive measures to preserve glycemic control can be taken (155).

AI and CGM-derived glycemic variability (GV) metrics provide a novel approach to enhancing risk assessment and enabling early, customized interventions in prediabetes—a critical window for preventing the onset of type 2 diabetes (157). CGM technology records dynamic glucose fluctuations and offers granular insights, in contrast to traditional metrics like HbA1c, which often overlook transient dysglycemia in prediabetic individuals (158, 159). AI-driven analytics can be used to systematically evaluate multidimensional GV parameters, such as coefficient of variation (%CV), time in range (TIR), time above/below range (TAR/TBR), and postprandial glucose responses (PPGR), to identify high-risk subgroups (160). Even in well-managed populations, studies show that elevated %CV (>33%) correlates with hypoglycemia risk and suboptimal glycemic control, and post-breakfast glucose excursions are early indicators of dysglycemia progression in prediabetes (161). These metrics are combined with clinical variables like insulin resistance and β-cell function by AI models like supervised learning and unsupervised clustering to stratify patients into various “glucotypes” and increase predictive accuracy (158, 162). The integration of CGM-derived glycemic variability (GV) metrics with AI represents a transformative approach to refining risk stratification and enabling early, personalized interventions in prediabetes—a critical window for preventing progression to T2DM (157).

The automated processing of CGM data via AI pipelines addresses the primary shortcomings of manual analysis, enabling scalable, real-time risk assessment. Machine learning algorithms have successfully predicted nocturnal hypoglycemia using state-of-the-art metrics such as the gradient variability coefficient (GVC), which simultaneously measures GV amplitude and hypoglycemia frequency (161). AI-powered meal detection algorithms improve postprandial glucose measurement accuracy by reducing reliance on self-reported logs, which are prone to error (163). These advancements particularly affect marginalized populations, where disparities in diabetes technology access exacerbate health inequalities (162). Notably, AI-enhanced CGM analytics have identified metabolomic signatures associated with GV, suggesting potential biomarkers for early intervention (164). Because longitudinal studies link GV to cardiometabolic outcomes like atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events in prediabetes, its prognostic value goes beyond glycemic control (158, 165).

The combination of CGM and AI may improve personalized prediabetes prevention strategies. Dynamic risk models that include TIR and PPGR could direct tailored lifestyle or medication interventions, such as treating post-breakfast hyperglycemia with dietary modifications (162, 166). Furthermore, there is mounting evidence that short-term GV metrics can be used to forecast long-term complications, offering a useful alternative to HbA1c in resource-constrained settings (159, 167). However, there are still problems, like validating AI models in large-scale trials and standardizing GV thresholds across different populations (160, 168). In order to understand the mechanistic connections between GV and T2DM pathogenesis and eventually enable precision medicine in the management of prediabetes, future research should give priority to integrated multi-omics approaches (158, 164). Clinicians can shift from reactive to proactive care by utilizing AI-driven CGM analytics, reducing the worldwide burden of type 2 diabetes in its early stages.

AI-processed CGV metrics represent a paradigm shift in the management of prediabetes by providing unparalleled granularity in risk assessment and intervention customization. From automated glucotype classification to metabolomic biomarker discovery, these developments bridge the gap between data-rich CGM outputs and useful clinical insights. As technology advances, integrating AI with real-time CGM data will be crucial to achieving early, equitable, and customized diabetes prevention (162, 166).

The integration of AI with CGM systems still faces a number of obstacles, despite the notable progress. The generalizability of AI models across diverse patient populations remains a critical challenge in diabetes management, particularly when addressing the distinct pathophysiological profiles of type 1 diabetes (T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D). Long short-term memory (LSTM) networks have shown strong performance in cross-population validation studies, making them a promising tool for hypoglycemia prediction. Their capacity to identify temporal dependencies in continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) data is a significant innovation. For mild hypoglycemia prediction in Chinese cohorts, they achieved area under the curve (AUC) values exceeding 97%, with only a slight 3% decrease when applied to European-American populations (152). This performance outperforms conventional machine learning techniques like random forests (RF) and support vector machines (SVM), which frequently have trouble with false alarm rates—a major obstacle to clinical adoption (152). The LSTM's superiority stems from its capacity to model complex glucose dynamics while maintaining high specificity (reducing false alarms by up to 42% compared to SVM/RF) across both T1D and T2D subgroups (152).

However, resolving the intrinsic constraints in training data diversity is essential to these models' translational potential. When used in global populations or for the management of type 2 diabetes, the majority of early hypoglycemia prediction algorithms may be biased because they were created using small, homogeneous cohorts of Western T1D patients (152). Due to variables that may not be sufficiently represented in training datasets, such as younger age, lower BMI, and higher use of premixed insulin formulations, Southeast Asian T2D patients have distinct risk profiles (152). Although continued validation in underrepresented populations is still crucial, the LSTM's demonstrated generalizability in a validation cohort of 427 patients suggests its adaptability to these heterogeneities (152).

The clinical utility of LSTMs is further improved by technological developments in model interpretability. To verify whether LSTM-based predictions are consistent with physiological principles—a crucial prerequisite for patient safety—tools such as SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) have been used (169). Two LSTM variants with similar accuracy showed significant differences in clinical reliability in one study: only the physiologically consistent model (p-LSTM) correctly learned the inverse relationship between insulin administration and glucose levels, as confirmed by SHAP analysis (169). This emphasizes how crucial it is to incorporate explainability frameworks to guarantee that models generalize across populations both statistically and pathophysiologically (169).

Additional avenues for enhancing generalizability are provided by the combination of ensemble techniques and hybrid architectures. To overcome the drawbacks of single-model approaches, bidirectional LSTM layers combined with transformer encoders, for instance, can simultaneously capture short-term glucose fluctuations and long-term trend (170). Personalized glucose forecasting using such hybrid systems has shown promise, especially when metabolomic or immune response data are included to account for inter-individual variability in T1D progression (170). Similarly, using feature selection algorithms like GALGO, which cut input variables by 50% without compromising accuracy, sex-specific ensemble models for T2D prediction achieved AUCs of 0.96–0.98. This approach could be modified for population-specific tuning (63).

Despite these developments, there are still significant gaps. There is little research on how AI-driven insights translate into customized treatment modifications; instead, the majority of studies concentrate on glycemic prediction rather than therapeutic outcomes (171). Biases in model performance can be sustained by differences in dataset representation, such as the UK Biobank's underrepresentation of female and non-White participants (172). The most predictive factor for the risk of hypertension in T2D patients was sex assigned at birth, although its relative significance differed greatly between datasets with different demographic balances (172). Addressing these disparities requires not only larger, more diverse cohorts but also algorithmic innovations like federated learning to pool data across institutions while preserving privacy (172).

Three areas should be given priority in future directions: multi-omic integration (e.g., metabolomic markers for insulin resistance in T2Dor TCR sequencing for autoimmune risk stratification in T1D) (173). Additionally, real-world hybrid model validation in low-resource environments where CGM adoption is increasing, and standardization of outcome measures to facilitate comparisons between different studies (173). The success of zimislecel, an allogeneic stem cell-derived treatment that restored endogenous insulin production in T1D patients, illustrates the potential for combining AI with biomarker-driven interventions to customize diabetes care (174). Achieving equitable clinical impact will depend critically on AI models' ability to generalize across the whole range of diabetes subtypes, ethnicities, and comorbidities as the field advances toward precision medicine.

Although cross-population generalizability for diabetes management has advanced significantly with LSTM-based models, their ultimate usefulness will depend on thorough validation in practical contexts, improved interpretability frameworks, and proactive mitigation of dataset biases. The combination of wearable technology, immunotherapeutic advancements, and deep learning provides a roadmap for creating truly patient-centric solutions that cut across phenotypic and geographic barriers (175, 176). The models' ability to adjust to abrupt changes in glucose dynamics, such as those brought on by illness or medication changes, is also called into question by their reliance on historical CGM data for training (156).

A paradigm shift in diabetes care is being brought about by the combination of AI with wearable and CGM devices, which presents previously unheard-of possibilities for individualized, real-time glucose prediction. At the forefront of this change are Transformer models and LSTM networks, which have special advantages in managing sequential data. Transformers have the potential to capture intricate, long-range dependencies and may even outperform LSTMs in specific situations, even though LSTM models have proven their effectiveness in short-term glucose prediction. Realizing the full potential of AI in diabetes care will require further development of AI models as well as increases in generalizability and computational efficiency. These technologies have the potential to significantly contribute to the creation of closed-loop insulin delivery systems, which will ultimately enhance the lives of diabetics.

2.3.2 Real-Time decision support

A revolutionary development in the treatment of diabetes is the combination of wearable technology and CGM systems, especially when it comes to real-time decision support for hypoglycemia alerts and meal recommendations. People with diabetes can now make well-informed decisions regarding their insulin dosage, food choices, and physical activity levels thanks to this innovation, which uses the continuous, high-frequency data produced by CGM devices to provide actionable insights. These systems’ real-time functionality fills important gaps in conventional self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) techniques, which frequently offer patchy and delayed data, raising the possibility of hypoglycemic episodes and less-than-ideal glycemic control (4, 177).

The ability to anticipate and prevent hypoglycemia through predictive low glucose alerts is one of the biggest technological benefits of combining CGM with wearables. Predictive low glucose alerts have been shown in studies to dramatically improve patient safety by reducing the frequency and duration of hypoglycemic episodes by up to 59% (178). Because they offer early warnings that enable prompt interventions, like carbohydrate consumption or insulin adjustments, these alerts are especially helpful for people with impaired hypoglycemia awareness or those who are at high risk of experiencing severe hypoglycemia (178, 179). By integrating these alerts with wearable technology, users can minimize disruptions to their routines by receiving notifications in real-time, even while they are involved in daily activities (177).

Apart from preventing hypoglycemia, the incorporation of CGM with wearable technology enables customized meal suggestions, which are essential for maximizing postprandial glucose regulation. When planning food intake, sophisticated algorithms, like those used by the DiaCompanion system, forecast postprandial blood glucose levels using real-time CGM data and offer customized dietary recommendations (180). This method lessens the burden of manual glucose monitoring and dietary planning, which can be especially difficult for people with T1D or GDM. It also helps people avoid hyperglycemic spikes (181). Integrating these suggestions with automated insulin dosing systems has the potential to enable more aggressive insulin adjustments upon meal detection, which can then be confirmed by positive CGM rate-of-change trends. This could lead to fully closed-loop insulin delivery (182).

Numerous studies have validated the practical use of these technologies and shown notable improvements in glycemic outcomes, such as HbA1c level reductions, longer time in range (TIR), and shorter hypoglycemic duration (181). In comparison to intermittently scanned CGM (isCGM), the use of real-time CGM with alert functionality has been demonstrated to increase TIR by 6.85 percentage points, underscoring the additional advantages of real-time data integration and decision support (179). Additionally, combining CGM data with other health indicators like electrodermal activity and heart rate variability improves the precision of hypoglycemia forecasts and offers a more comprehensive approach to diabetes care (183).

The effectiveness of RT-CGM in enhancing glycemic control in pregnant women with T1D and GDM has been shown by randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The CONCEPTT trial demonstrated how CGM can lower maternal hyperglycemia and improve neonatal outcomes, such as a decreased risk of neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admissions and large-for-gestational-age (LGA) infants (184). Recent studies have explored the integration of AI with RT-CGM, expanding on these findings to provide real-time dietary interventions. One hour after meals, the DiaCompanion I smartphone app forecasts blood glucose levels using AI based on user-provided meal data. Through real-time meal modification, women with GDM can maintain glucose levels within the recommended range, improving glycemic control and reducing the need for frequent clinic visits (180). Because it tackles the dynamic and unique nature of glucose regulation during pregnancy, the use of AI in this context is especially novel. Complex CGM data can be analyzed by AI algorithms to spot trends and forecast glucose excursions, providing personalized dietary advice that takes into consideration variables like insulin sensitivity, physical activity, and meal composition (180). In addition to improving adherence to dietary interventions, this individualized approach gives patients the confidence to actively manage their condition. Additionally, by reducing the need for frequent in-person consultations, the integration of AI with RT-CGM can ease the strain on healthcare systems, which is particularly advantageous in settings with limited resources (185). The capacity of AI-integrated CGM systems to offer real-time feedback and decision support is one of their main technological advantages. AI systems can notify users when hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia is about to occur, enabling prompt actions like insulin administration or dietary changes. During pregnancy, when even brief episodes of hyperglycemia can have serious effects on fetal development, this preventative strategy is especially beneficial (180, 186). Additionally, even when patients are not physically present in the clinic, AI-driven CGM systems can enable remote monitoring, allowing medical professionals to track patients' blood sugar levels in real-time and take appropriate action (187). Additionally, there is potential for increasing the precision and dependability of glucose monitoring through the integration of AI with CGM. It has been demonstrated that the Dexcom G6 CGM system gives pregnant women accurate glucose readings across a number of sensor wear sites, with a mean absolute relative difference (MARD) of 10.3% when compared to reference values (184). These systems can further improve accuracy by correcting for sensor errors and supplying more trustworthy data for clinical decision-making when paired with AI algorithms. This is especially crucial during pregnancy, when careful glucose management is necessary to reduce the chance of negative consequences (184). The broad use of AI-integrated CGM systems still faces obstacles in spite of these developments. These include creating user-friendly interfaces, integrating these technologies into current healthcare workflows, and requiring strong clinical validation. More research is required to assess the long-term advantages and cost-effectiveness of these systems, especially in healthcare settings with a variety of patient populations (180). An important advancement in the control of blood sugar levels during pregnancy is the combination of AI with wearable and continuous glucose monitoring devices. These systems have the potential to enhance glycemic control, lower the risk of negative outcomes, and enable patients to actively manage their condition by offering real-time, customized dietary interventions.

2.3.3 Telemedicine